An Analysis of Gender Displays in Selected Children Picture Books in Kenya

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

International Journal of Arts 2012, 2(5): 31-38

DOI: 10.5923/j.arts.20120205.01

An Analysis of Gender Displays in Selected Children

Picture Books in Kenya

Philomena N. Mathuvi1,* , Anthony M. Ireri2, Daniel M. Mukuni3 , Amos M. Njagi2 , Njagi I. Karugu4

1

Department of Kiswahili, Kenyatta University, Kenyatta University, P.O. Box 43844, 00100, Nairobi

2

Department of Educational Psychology, Kenyatta University, P.O. Box 43844, 00100, Nairobi, Kenya

3

Department of English & Linguistics, Kenyatta University, P.O. Box 43844, 00100, Nairobi, Kenya

4

Department of Education, Chuka University College, P.O. Box 109-60400, Chuka, Kenya

Abstract Ch ildren’s books are an early source of gender role stereotypes. Gender d isplays in such books can be read or

interpreted as a social problem in any education system. The study aimed at identifying co mmon gender displays in 40

children picture books used as supplementary English texts for classes 1 to 3 in Kenya published between 2005 and 2010.

Five forms of gender display were evaluated based on Ervin Goffman’s model of decoding gender displays and visual sexis m.

Through content analysis, mean stereotyping scores for each behavioural category were co mputed and the overall score for

each year determined. Findings indicate that the behaviour of females is significantly d ifferent fro m that of males in the

selected books. Both positive and negative images about females have been given although the pattern changes from year to

year. Suggestions for practice and further research are given.

Keywords Gender Studies, Ervin Goffman, Children Picture Books, Kenya

gender develops gradually in three steps: Gender labelling

1. Introduction (by 2 -3years) when children understand that they are either

When a child is born, one of the first questions mothers boys or girls and naming themselves accordingly; gender

encounter is whether it is a boy or a girl. Different people stability (during preschool years) when children begin

even behave differently to a newborn depending on its understanding that boys become men and girls beco me

gender. Thus from infancy we are exposed to community wo men; and gender constancy (4-7 years) when most

portrayals of how one should behave with other people. It is, children understand that maleness and femaleness do not

therefore, not surprising that roles associated with gender are change over situations and personal wishes. The theory

among the first ones that children learn in life. Gender posits that gender serves to organize many perceptions,

development actually co mprises a crit ical part of learning attitudes, values and behaviour.

experiences of young children. Since books contribute According to Kohlberg, children begin learning about

greatly to the learning experiences of young people, they gender roles after they have mastered gender constancy.

equally contribute to their gender identity development. In Research generally supports this prediction[2] but Ruble and

this paper, we review various theoretical perspectives on others[3] argue that children start learning gender-typical

gender development, effects of books on gender behaviour as soon as they master gender stability and this

development, co mmon mot ifs of gender portrayal in understanding becomes flexib le with time.

literature, gender stereotypes in children’s literature and then The gender-schema theory explains how children acquire

report on a study evaluating gender displays in children gender roles by stating that children want to learn more about

books used in Kenya. an activity only after first deciding whether it is masculine or

femin ine. Thus, when children know their gender, they pay

2.1. Theoretical Perspecti ves on Gender Roles selective attention primarily to experiences and events that

Different theories address when and how children begin are gender appropriate[4]. So me studies support this

learning about gender-appropriate behaviour and activ ities. pattern[5].

Below is an overview of some theoretical perspectives: Under the framework of social cognitive theory, it is

According to Lawrence Kohlberg[1] fu ll understanding of assumed that children learn gender ro les by watching the

world around them and learning the outcomes of different

actions. Thus the actions of parents, teachers, siblings and

* Corresponding author:

pnthamba@yahoo.com (Philomena N. Mathuvi) peers shape appropriate gender roles in children[6]. In this

Published online at http://journal.sapub.org/arts perspective, child ren learn what their culture considers

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved appropriate for males and females by simp ly watching how32 Philomena N. M athuvi et al.: An Analysis of Gender Displays in Selected Children Picture Books in Kenya

adults and peers interact. Under this theory, the development illustrations combine to tell the story); and illustrated books

of gender ro le identity is shaped by the shared beliefs of (which rely mainly on the text, supported by illustrations to

society[7]. tell the story). The unique feature of picture storybooks is

Evolutionary developmental psychology informs us that that the text and story do not merely reflect each other. The

different roles like providing important resources for young text and illustrations amplify each other to tell a story that

ones and involvement in child rearing caused different traits goes beyond what one reads. Stephens[20] suggests that

and behaviours to evolve for men and wo men[8]. The ideologically, picture books belong firmly within the domain

biological basis for gender-role learning is supported by of cultural practices which exist for the purpose of

studies which show strong preference for sex-typical toys socializing their target audience. Illustrated books

and activities between pairs of identical and fraternal particularly have a significant impact on gender

twins[9]. The perspective is also supported by research development[21]. It is argued that the power of illustrated

involving females exposed to male hormones during prenatal books lies in their use of visual images as nonverbal

development[10]. symbols[22].

As children learn the gender roles, they also pick beliefs Research has affirmed that gender stereotyping in

and images-stereotypes- about males and females fro m their children’s books is influential on children ’s identity

social environment. These stereotypes influence differences development. According to Easley[23] the development of

in our expectations for males and females regarding their preschoolers’ gender identities often occurs concurrently

behaviour and feelings[11]. They also influence our response with their desire to repeatedly view their favourite picture

to other people’s behaviour and the inferences we make books. Other researchers highlight the detrimental effects of

about behaviour and personality[7]. Research ind icates that negative gender portrayals in ch ildren’s books on their

children learn gender stereotypes early in life and that gender identity, self-esteem, and perception of gender ro les[21].

stereotyping increases with age. For examp le, in one study Exposure to sex-stereotyped books contributes to an increase

18-month-olds exh ibited gender differences in how they in sex-typed play behaviour[24].

looked at gender-stereotyped toys. Girls looked longer at Other researchers posit that picture books offer children a

pictures of dolls than pictures of t rucks wh ile boys looked resource through which they discover worlds beyond their

longer at pictures of trucks[12]. By 4 years of age, children’s own life-space. Picture books help children to learn about the

knowledge of gender stereotypes is extensive and they begin lives of those who may be quite different fro m

to learn about behaviours as well as traits that are themselves[25]. Thus from read ing picture books, children

stereotypically masculine or feminine[13]. For examp le, a may adjust their existing knowledge about their developing

2005 study found that preschoolers believed that boys are gender identity. Thus the way socialization experiences are

more often aggressive physically but girls tend to be written exerts a positive or negative influence on the

aggressive verbally[14]. 5-year-o lds believe that boys are construction of gender role identit ies and stereotypes. The

strong and dominant and girls are emot ional and gentle[15]. implication fro m the foregoing is that the books that

Beyond preschool years, children learn more about educators and parents select for their ch ild ren’s learn ing and

stereotypes, become more flexible regarding gender recreation have an impact beyond the reading experience.

stereotypes[16] and learn differences in the gender There is a need to be particularly conscious about traditional

stereotypes[15]. gender stereotyping present in the reading materials that

The theories on gender roles development are vast and we children are exposed to.

did not intend to exhaust reviewing all of them in this paper. Early children books emphasized the tradit ional role of the

However, it is apparent fro m the foregoing review that by the active male and the passive female. A co mmon ly cited

time children learn to read, they have acquired gender lenses study[26] sought to find out if gender differences existed in

through which they try to evaluate and understand social characters and the representation of character roles in 18

experiences. It is expected that children refine these lenses Caldecott Award medal books. The study revealed that

fro m the books they read. character differences described women as passive and

immob ile versus males as leaders, independent, and active.

2.2. Effects of B ooks on Gender Devel opment

Males had higher occupation roles than females and overall

In the process of socialization, societal values are males appeared 11 times more o ften than females in the

transmitted fro m one generation to the next. As noted by central ro le, as the main character or even in the tit le. These

Arbuthnot[17], books are often the primary source for the books were argued to portray girls as second to boys in all

presentation of societal values fro m one generation of aspects of life[21].

readers to the next and for gender socializat ion[18]. It is interesting to note that the increase in the global steps

Consequently , children’s books serve as a socializing tool to towards equity between men and wo men has not been

transmit values to the young. These books are a strong matched by increase in equal portrayal of men and wo men in

purveyor of gender role stereotypes. literature. For example Crabb and Bielwaski[27] found that

Temp le and colleagues[19] describe three types of picture household artefacts were still most often used by females in

books: wordless books (where the reliance is totally on children’s picture books and that females’ use of these

pictures to tell the story); picture storybooks (where text and artefacts failed to reduce over time. Other researchers reportInternational Journal of Arts 2012, 2(5): 31-38 33

an increase in female representation as main characters in 2.3.2. Portrayal Based on Physical Features

proportion to male characters and that authors were aware of The physical feature is used to refer to the way a writer

the need for positive images for girls and boys[21] However, describes his characters in relation to their body build. By

it was noted that women tended to assume non-traditional referring to physical features, the writer distinguishes

characteristics when in a central ro le and reverted to female characters fro m male characters by associating

traditional stereotypes when not in a central ro le[28]. particular attributes to femaleness or maleness. In a

As a way of enhancing literacy skills develop ment, patriarchal society like the Kenyan one, male physique is

children in primary schools are expected to read exclusively big, strong and unconquerable while the female

recommended texts. Most of the class readers are is invariably frail and vulnerable. This vulnerability is what

supplementary texts that are not tested in the national is often used to justify the societal view that wo men or girls

examinations. Mostly, such texts are by African writers always need the physical protection of the men or boys.

though some classic texts fro m Eu rope are at t imes included

to enrich the literary experience of the students. In their 2.3.3. Portrayal Based on Gender Roles

reading of the selected books, the child ren are expected to The dominant literary attitude has been to present the

enjoy their reading as well as demonstrate awareness of the wo man as an insignificant figure in the daily polit ics of

society in which they live[29]. Ho wever, it is not clear village life, unearthing in the process the detestable

whether such books present gender stereotypes to the disadvantages of her day-to-day existence. Villagers have

children. In addition, most of the availab le studies on the evolved from just acquiescent components of a group into

portraiture of gender in children literature have been individuals with choices and preferences. The emergence of

conducted outside Kenya and few of those conducted in an individualistic society also provides the appropriate

Kenya focus on children literature meant for classes 1 to 3. framework for the analysis of character and fo r a mo re

Further, current studies on the portraiture of female comprehensive appreciation of gender roles[30].

characters have mostly focused on characterization and few

have been conducted on how children perceive characters in 2.3.4. Gender Stereotypes in Children ’s Literature

the picture books. Out o f this, little is known about the kind

A majority of the studies that have analyzed gender

of stereotypes we expose our children to through the selected

stereotypes within children’s literature have focused on

literature. To contribute to research in this area, the study

character prevalence in t itles, p ictures and central roles, and

sought to evaluate how women and girls are portrayed in the

on gender differences in the types of roles and activities

children story books and what messages such portraiture

associated with the characters. Although more recent

gives to the children about wo men in the society.

studies reveal that gender differences in ch ildren ’s literature

have decreased considerably toward mo re sexual equality,

2.3. Common Motifs of Gender Portrayal in Literature

with female representation as main characters becoming

In general literature, various motifs have been used in proportionate to that of male characters[32], research

portraying wo men[30]. So me of these motifs are presented indicates that this has been an issue for years and more

below: needs to be done[21, 30-31].

Angela and Mark Gooden[21] analy zed 81 Notable

2.3.1. Portrayal Based on Sex

Books for Children fro m 1995 to 1999 for gender of main

This view considers sex as a category distinguishing character, illustrations and title. The authors concluded that

males fro m females in terms of biological characteristics steps toward equity had advanced based on the increase in

which may be listed under two considerations: First, females represented as main characters; however, gender

secondary sex characteristics such as women having b reasts stereotypes were still significant in children’s picture books.

and men growing beards or developing a deep voice. As hypothesized, female representation as the main

Secondly, the physiological functions like pregnancy; character equally paralleled that of males, but males

giving birth or breast feeding is for wo men while the men appeared alone more often than females in the illustrations.

are associated with reproduction. And, although there was an emergence of non-traditional

Portrayal based on sex entails physical and tangible characteristics and non-traditional roles portrayed by

attributes, which the writer apportions his/ her character on females and males, males still do minated the children’s

the basis of anatomy or sex roles. In attempting to portray literature reviewed.

the maleness or femaleness of their characters, writers often A study done in 2003 took a look back at progressive

use the attributes of physical features and physical strength. change in the depiction of gender in award-winning picture

The further back one goes in African fiction, the mo re books for children[33]. The authors concluded that books

pronounced is society’s preference for male offspring and fro m the late 1940s and late 1960s had fewer visib le female

the more insignificant is the woman’s presence and action characters than those fro m the late 1930s and late 1950s,

in such fiction. This trend is in keeping with the return to but that characters in the 1940s and 1960s were less gender

the mainspring of trad itional culture and therefore to its stereotyped than the characters from the 1930s and 1950s.

patriarchal beginnings[31]. The results were interpreted as having a direct correlation34 Philomena N. M athuvi et al.: An Analysis of Gender Displays in Selected Children Picture Books in Kenya with the level of conflict over gender ro les during each time resort to subtle sexis m where blatant sexis m is discouraged. period. In 2006, Hamilton and colleagues[34] conducted a 2.3.5. Goffman’s Model Of Decoding Gender Displays and twenty-first century update on gender stereotyping and Visual Sexis m underrepresentation of female characters in 200 popular In 1979, Erv ing Goffman[39] found subtle visual sexism children’s books. The results showed that female characters in his examination of gender bias in advertising through are still underrepresented in children’s picture books. There such cues as relative size (wo men shown smaller or lo wer, were nearly twice as many male than female main relative to men), femin ine touch (women constantly characters; male characters appeared more often in touching themselves), function ranking (occupational), illustrations; female characters were showcased nurturing ritualization of subordination (proclivity for lying down at and indoors more than male characters; and occupations inappropriate times, etc.) and licensed withdrawal (wo men were gender stereotyped. never quite a part of the scene). In his book, Goffman Beyond character prevalence and character roles and concluded that women were weakened by advertising activities, there have been some researchers who have taken portrayals via these five categories. However, these different approaches to analyzing gender stereotypes within categories of decoding behaviour have not been formally children’s literature. For examp le, in a study analyzing sex explored in examin ing the portrayal of wo men in written bias in the help ing behaviour presented in child ren’s picture works of art. Though the model is based on the visual books, it was concluded that male characters were found to displays of women, it can also be used to analyse the be represented more frequently than females both as child descriptive portrayal of wo men in written literature. helpers and as the recipients of help[35]. Based on Goffman’s theoretical framework, the purpose Arthur and White[36] researched children’s assignment of this study was to fill the gap that exists in the existing of gender to gender-neutral animal characters. The study research between studies on the portrayal of females in indicated that the youngest children most often assigned relation to gender behaviour patterns in advertising and the their own gender to the characters; however, the children in representation of females in written literature. the older groups were influenced by stereotypes. For To this end, the study explo red how wo men and girls are example, solitary and non-interacting characters were less portrayed in the selected classes 1 to 3 children books likely to receive female gender labels than were bears recommended in the Kenya Institute of Education’s The involved in adult-child interactions. Orange Book between 2005 and 2010. Specifically, the study A study done in 1999 examined a different potential area evaluated the gender stereotypes presented in the children of gender stereotyping, gender differences in emot ional books focused on the following objectives: language in children’s picture books[37]. It was i. To analy ze the prevalence of the gender-specific hypothesized that there wou ld be a relationship between behaviours mentioned in Goffman’s model in the children gender and the amount of emotional words associated with books. each characters, and that male characters would more often ii. To describe the messages about women given to the be associated with emotional words considered appropriate society through children’s literature. for males, while female characters would mo re often be iii. To evaluate whether the messages in children books associated with emotional wo rds considered appropriate for have changed from 2005 to 2010. females. The analysis of character prevalence indicated that males had a higher representation in titles, pictures and central ro les. However, contrary to the hypotheses, males 3. Methodology and females were associated with equal amounts of emotional language, and no differences were found in the 3.1. Research Design types of emotional words associated with males and The study used a qualitative design in which a descriptive females. text analysis approach was adopted. The study relied on a Whereas previous studies looked at the narrowly defined close textual reading of the selected children texts which roles of female characters, one study focused on the was informed by social changes in the Kenyan society. representation of mothers and fathers, and examined whether men were stereotyped as relatively absent or inept 3.2. Sample partners[38]. The results of the content analysis indicated The data used for this study were picture storybooks that fathers were largely underrepresented and, when they dealing with the experience of starting school. Kenya did appear, they were withdrawn and ineffectual. Institute of Education annually publishes a list of According to Anderson and others[34] although gender recommended course and supplementary reading texts for all representation in children’s literature seems to be improving, classes in Primary and secondary education in The Orange we should be aware that there may be more subtle ways in Book. In th is study, over 100 children’s books for classes 1 which the sexes are portrayed stereotypically. They suggest to 3 listed in the Orange Book between 2005 and 2010 were a possibility that authors consciously or unconsciously consulted. Of these, 40 met the criteria of picture

International Journal of Arts 2012, 2(5): 31-38 35

storybooks, in that both text and illustrations combined to As seen in figure 1 above, the selected books published in

tell the story. Books that were not considered include 2005 had on average male characters presented as superior

readers–where the text was supported by an occasional than female characters, female characters were on average

illustration–and books that clearly related to starting child presented as touching or cuddling objects, as lowered or

care, or preschool, rather than formal school. Where books sitting, and as withdrawn fro m a particular situation.

were described as relevant across different stages–for However, men were not presented as taller than wo men in

example suitable for classes 1-3, they were included in the the illustrations.

sample. The picture storybooks studied were all written in In the books published in 2006, on average male

English. The books are currently available in the major characters were mainly superior than female characters in

retail outlets. their roles. In addit ion, the female characters were main ly

3.3. Data Collection Procedures presented as touching objects, inferior to smaller than men or

in lo wered or sitting positions. However, female characters

Five forms of gender displays espoused in Goffman’s were mostly presented as not withdrawn fro m the situation

theoretical framework were evaluated: relative size, portrayed in the illustrations.

femin ine touch, function ranking, ritualization of In the books published in 2007, female characters were

subordination and licensed withdrawal. The dependent mostly presented as inferior to male characters and in

variable was the frequency of gender displays in the selected postures that displayed ritualized subordination. In addit ion,

book, and the independent variable was the year of wo men were withdrawn fro m the situations illustrated.

publication. Cod ing was based on the following criteria for Notably, men were mainly presented as not taller than

each category: Relative Size – Male taller; the height of wo men and fewer female characters were presented touching

male and female models are co mpared (Male taller =1, or cuddling objects.

Male not taller = 0); Feminine Touch – Cradling and/or In the books published in 2008 and 2010, male characters

caressing object, touching self; the women is described in were presented as taller and as taking superior ro les than

the illustration using her fingers and hands to trace the female characters. The female characters were described

outline of an object, to cradle it or to caress its surface (Yes touching objects and in postures that displayed ritualized

= 1, No = 0); Function Ranking – Male as the instructor, subordination to male characters. The female characters

female serving other person, male in superior role; the man were mainly described withdrawn fro m the situations

is instructing the wo men in the illustration (Yes = 1, No = presented in the illustrations. However, the means for all the

0); Ritualizat ion of Subordination – Female lo wering, categories for the two years appeared to cluster between 1.2

lying/sitting on sofa (Yes =1, No = 0); Licensed and 1.4.

Withdrawal – Expansive smile, covering mouth/face with In the books published in 2009, female characters were on

hand, head/eye gaze aversion, phone conversation, average withdrawn fro m the illustrated situations. They were

withdrawing gaze, body display; the female is described as also shown displaying ritualized subordination or taking

withdrawn or removed (mentally and/or physically) fro m a roles inferior to those of males. Male characters were on

particular situation (Yes = 1, No = 0). average not taller than their female counterparts while

female characters were least presented touching objects.

3.4. Data Analysis

However, the female characters were not described as..

As with Kang’s study[22], a content analysis was As shown in table 2, most books had taller male characters

performed. For each coding category, different scores were presented in superior roles and while wo men characters were

assigned: the score of one if it is a stereotypical behaviour mainly portrayed as lowering, withdrawn fro m situations and

and the score of zero if it is a nonstereotypical behaviour. as cradling objects.

By adding up the scores, the overall gender display score for A single-sample t-test compared the means of the various

the selected book was measured. Therefo re, a higher score categories of gender displays as shown in table 3 above.

indicated more stereotyping, and a lower score indicates Based on the extant literature, it was assumed that wo men

less stereotyping. The mean stereotyping scores for each are portrayed as withdrawn, submissive and inferior to men.

behavioural category were then co mpared in order to Thus the population mean was assigned a value of 1. In the

determine an overall stereotyping score for each. five gender display categories adapted from the Goffman

model, the sample means were significantly greater than the

population mean. A significant difference was found for

4. Results each category thus: relative size (t (39) =3.365, p 0.05);

Table 1 belo w g ives the summary statistics for various Femin ine touch (t (39) =4.333, p 0.05); both function ranking

caategories of gender displays in the analyzed books per and ritualized subordination had (t (39) =5.649, p 0.05) and

year of publication. licensed withdrawal had (t (39) =4.0088, p 0.05).36 Philomena N. M athuvi et al.: An Analysis of Gender Displays in Selected Children Picture Books in Kenya

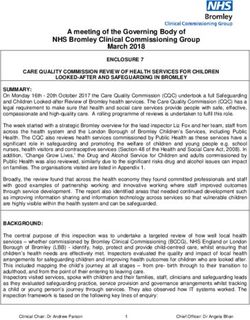

Table 1. Summary statistics of the various categories of gender displays per year of publication

Ritualized

Relative size Feminine touch Function ranking Licensed withdrawal

subordination

M 1.00 1.50 1.75 1.25 1.25

2005 N 4 4 4 4 4

S.d .00 .58 .50 .50 .50

M 1.33 1.67 1.67 1.5000 1.1667

2006 N 6 6 6 6 6

S.d .52 .52 .52 .55 .41

M 1.17 1.17 1.50 1.67 1.33

2007 N 6 6 6 6 6

S.d .41 .41 .55 .52 .52

M 1.33 1.33 1.22 1.33 1.22

2008 N 9 9 9 9 9

S.d .50 .50 .44 .50 .44

M 1.17 1.17 1.50 1.67 1.50

2009 N 6 6 6 6 6

S.d .41 .41 .55 .52 .55

M 1.22 1.22 1.33 1.33 1.33

2010 N 9 9 9 9 9

S.d .44 .44 .50 .50 .50

M 1.23 1.33 1.45 1.45 1.30

Total N 40 40 40 40 40

Sd. .42 .47 .50 .50 .46

Note: M= mean; s.d= standard deviation; N=count. Concept adapted from Goffm an[1976]

Table 2. Overall gender display in the sampled books

Gender Display Category Variety Frequency (N=40) Percentage (%)

Men as superior 22 55

Function Ranking

Men not superior 18 45

Female Lowering 22 55

Ritualized Subordination

Female not lowering 18 45

Women withdrawn from situation 28 55

Licensed withdrawal

Women not withdrawn from situation 12 45

Male taller 31 77.5

Relative size

Male not taller 9 22.5

Women cradling objects 27 67.5

Feminine touch

Women not cradling objects 13 32.5

Table 3. One-Sample T-test results Concept adapted from Goffman[1976]

Test value = 1

Sig. α =0.05

t df Mean Difference

(2-tailed). Lower Upper

Relative size 3.365 39 .002 .235 .090 .360

Feminine touch 4.333 39 .000 .325 .173 .477

Function ranking 5.649 39 .000 .450 .289 .611

Ritualized subordination 5.649 39 .000 .450 .289 .611

Licensed withdrawal 4.088 39 .000 .300 .152 .448International Journal of Arts 2012, 2(5): 31-38 37

roles for our children through our education system. A

2.0000

similar study can also be conducted to establish the portraits

1.8000 Mean Relative

1.6000

of wo men and girls in Kiswahili ch ild ren texts reco mmended

size

1.4000 for Kenyan schools and a comparison be done with the

1.2000 English texts. This would go a long way in depict ing a

Mean

Mean

1.0000

Feminine

concrete image of the Kenyan Education system.

.8000

touch

.6000

.4000 Mean Function

.2000 ranking

.0000 REFERENCES

Mean [1] Kohlberg, L., A cognitive-developmental analysis of

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

Total

ritualized children’s sex-role concepts and attitudes. In E.E. M accoby

Year

subordination (Ed.), The development of sex differences, Stanford

University press, 1966.

[2] M artin, C. L., Ruble, D., Children’s search for gender cues:

Figure 1. A comparison of the means of the gender displays across the cognitive perspectives on gender development, Current

years

Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 67-70, 2004.

[3] Ruble, D.N., Taylor, L.J., Cyphers, L., Greulich, F.K., Lurye,

5. Discussion L.E., Shrout, P.E. The role of gender constancy in early

gender development, Child Development, 78, 1121-1136,

The findings indicate that the behaviour of wo men and 2007.

girls based on Goffman’s model of decoding behaviour is [4] Liben, L. S., Bigler, R. S., The developmental course of

significantly d ifferent fro m that of men in the selected gender differentiation, M onographs of the Society for

English child ren books. This finding corroborates earlier Research in Child Development, 67 (serial No. 269), 2002.

studies on children texts where wo men were found to be

[5] Luecke-Aleksa, D., Anderson, D. R., Collins, P. A., Schmitt,

portrayed negatively compared to men[35; 40]. The findings K. L., Gender constancy and television viewing,

further reveal both positive and negative messages about Developmental Psychology, 31, 773-780, 1995.

wo men have been given in the selected texts. This is an

important finding since gender identities, stereotypes and [6] Bandura, A., Bussey, K., On broadening the cognitive,

motivational, and sociocultural scope of theorizing about

scripts are conceptualized fro m childhood and they have a gender development and sunctinoning: Comment on M artin,

powerful impact on children’s attitudes, values, beliefs and Ruble, and Szkrybalo (2002). Psychological Bulleting, 130,

behaviours[22]. Ho wever, it appears that the pattern of 691-701, 2004.

presentation differs fro m year to year. In most instances,

[7] Robert V. Kail, John C. Cavanaugh, Human Development, A

wo men are presented as second to men in function ranking. Life-span view, 5th ed. Wadsworth, USA, 2010.

Motifs of female character presentation that seem to

consistently appear throughout the years are the feminine [8] Geary, D. C., Sexual selection and human life history. In R. V.

Kail (Ed), Advances in child development and behavior (vol.

touch, ritualized subordination and licensed withdrawal.

30, pp. 41-102), Academic press, USA, 2002.

[9] Iervolina, A,C., Hines, M ., Golombok, S.E., Rust, J., Plomin,

6. Recommendations R., Genetic and environmental influences on sex-typed

behavior during the preschool years, Child Development, 77,

It is expected that these results will inform policy and 1822-1841, 2005.

curriculu m designers at Kenya Institute of Education (KIE) [10] Pasterski, V. L., Geffner, M . E., Brain, C., Hindmarsh, P.,

and the Ministry of Education as they choose and Brook, C., Hines, M ., Prenatal hormones and postnatal

recommend the literary experience Kenya school going socialization by parents as determinants of male-typical toy

children are expected to be exposed to. There is a need to play in girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Child

educate parents and teachers to use gender neutral literature Development, 76, 264-278, 2005.

and picture books that promote gender equality among the [11] Smith, E. R., M ackie, D. M ., Social psychology (2nd ed.),

sexes. Based on the current findings, the authors are Psychology Press, USA, 2000.

convinced that Goffman’s model of decoding behaviour

[12] Serbin, L. A., Poulin-Dubois, D., Colburne, K A., Sen, M . G.,

offers an effective theoretical framework for analyzing Eichestedt, J. A., Gender stereotying in infancy: Visual

gender representation in school books meant for children in preferences for and knowledge of gender-stereotyped toys in

an African setup. It is reco mmended that further research the second year, International Journal of Behavioral

based on this model be conducted focusing on the portraits of Development, 25, 7-15, 2001.

wo men in supplementary reading texts for children in other [13] Gelman, S. A., Taylor, M . G., Nguyen, S. P. M other-child

classes so as to get a more comp rehensive view of the frames conversations about gender. M onographs of the society of

of reference that we may be putting in place regarding gender Research in Child Development, 69 (275), 2004.38 Philomena N. M athuvi et al.: An Analysis of Gender Displays in Selected Children Picture Books in Kenya

[14] Giles, J. W., Heyman, G.D., Young children’s beliefs about 69–79, 1994.

the relationship between gender and aggressive behavior,

Child Development 76, 107-121, 2005. [28] Weiller, K. H., Higgs, C. T., Female learned helplessness in

sports: An analysis of children’s literature. Journal of

[15] Etaugh, C., Liss, M . B., Home, school, and playroom: Physical Education, 60, 65–67, 1989.

Training grounds for adult gender roles, Sex Roles, 26,

129-147, 1992. [29] Kenya Institute of Education (KIE), Kenyan Primary School

Syllabus, KIE, Kenya, 2002.

[16] Levy, G. D., Taylor, M . G., Gelman, S. A., Traditional and

evaluative aspects of flexibility in gender roles, social [30] Oyewumi, O. (Ed.) African Women and Feminism:

conventions, moral rules and physical laws. Child Reflecting on the Politics of Sisterhood, African World Press,

Development, 66, 515-531, 1995. USA, 2003.

[17] Arbuthnot, M . H., Children and books. Chicago, Scott [31] Egejuru, P. A. (Ed.) Nwanyibu: Womanbeing and African

Foresman & Company, USA, 1984. Literature, Trenton: African World Press, 1997.

[18] Bender, D. L., Leone, B., Human sexuality: 1989 annual, [32] Henderson, D., Kinman, J., An analysis of sexism in

Greenhaven Press, USA, 1989. Newberry M edal Award books from 1997 to 1984. The

Reading Teacher, 38, 885-889, 1985.

[19] Temple, C., M artinez, M ., Yokoto, J., Naylor, A. Children’s

books in children’s hands: An introduction to their literature, [33] Clark, R. Guilmain, J. Saucier, R. K., Tavarez, J., Two Steps

Allyn & Bacon, USA, 1998. Forward, One Step Back: The Presence of Female Characters

and Gender Stereotyping in Award-Winning Picture Books

[20] Stephens, J. Language and ideology in children’s fiction, Between the 1930s and the 1960s, Sex Roles, 49(9/10),

Longman, UK, 1992. 439-449, 2003.

[21] Angela Gooden, M ark Gooden, Gender Representation in [34] Anderson, D., Broaddus, M ., Hamilton, M ., Young, K.,

Notable Children’s Picture Books: 1995-1999. Sex Roles, Gender Stereotyping and Under-representation of Female

45(1/2), 89-101, 2001. Characters in 200 Popular Children’s Picture Books: A

Twenty-first Century Update, Sex Roles, 55, 757-765, 2006.

[22] Kang, M . E. The portrayal of women's images in magazine

advertisements: Goffman's gender analysis revisited. Sex [35] Leslie Dawn Helleis, Differentiation of Gender Roles and Sex

Roles, 37(11/12), 979-997 , 1997. Frequency in Children’s Literature, Ph.D. dissertation,

M aimonides University, USA, 2004.

[23] Easley, A., Elements of sexism in a selected group of picture

books recommended for kindergarten use, East Lansing, M I: [36] Arthur, A., White H., Children’s Assignment of Gender to

National Center for Research on Teacher Learning, (ERIC Animal Characters in Pictures, The Journal of Psychology,

Document Reproduction Service No. ED104559), 1973. 157(3), 297-301, 1996.

[24] Narahara, M . (1998). Gender stereotypes in children’s picture [37] Cassidy, K. W., Tepper, C., Gender Differences in Emotional

books. East Lansing, M I: National Center for Research on Language in Children’s Picture Books, Sex Roles, 40(3/4),

Teacher Learning. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service 265-280,1999.

No. ED419248)

[38] Anderson, D., Hamilton, M ., Gender Role Stereotyping of

[25] Peterson, S. B., Lach, M . A., Gender stereotypes in children’s Parents in Children’s Picture Books: The Invisible Father,

books: Their prevalence and influence on cognitive and Sex Roles, 52(3/4), 145-151, 2005.

affective development. Gender and Education, 2, 185–196,

1990. [39] Goffman Erving, Gender advertisements, Harvard University

Press, UK, 1979.

[26] Weitzman, L.J., Eifler,D., Hokada, E., Ross,C.,Sex-role

socialization in picture books for preschool children. [40] Claudia Rosa Acevedo, Carmen Lidia Ramuski, Jouliana

American Journal of Sociology, 77, 1125–1150, 1972. Jordan Nohara, Luiz Valério de Paula Trindade, A Content

Analysis of the Roles Portrayed by Women in Commercials:

[27] Crabb, P. B., Bielwaski, D., The social representation of 1973 – 2008, REM ark - Revista Brasileira de M arketing, São

material culture and gender in children’s books. Sex Roles, 30, Paulo, 9(3), 170-196, Brazil, 2010.You can also read