Aligning Economic Development as a Priority of the Integrated Development Plan to the Annual Budget in the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Aligning Economic Development

as a Priority of the Integrated

Development Plan to the Annual

Budget in the City of Johannesburg

Metropolitan Municipality

T Majam and D E Uwizeyimana

School of Public Management, Governance and Public Policy

University of Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Concerning local government specifically, economic development is a key priority

within the Integrated Development Plan (IDP) of a municipality to improve the qual-

ity of life of communities in South Africa. Finding constructive ways of developing

the economy especially to create jobs at the local level is a challenge faced by all

municipalities. Crucial to solving this challenge is to ensure that enough money has

been allocated to economic development programmes in the annual budget of the

municipality. This article explores whether the 2016/2017 IDP and Annual Budget of

the City of Johannesburg sufficiently aligned the IDP and the Annual Budget in terms

of prioritising economic development. It also identifies the gaps and policy targets

that have not been met in the implementation of the priority of economic develop-

ment in the 2016/2017 IDP and Annual Budget and the City of Johannesburg’s Service

Delivery Budget Implementation Plan. The methodological approach of this article is

mainly qualitative and based on a desktop analysis of official documents and literature.

Keywords: e conomic development, policy recommendations, Integrated

Development Plan, policy targets

INTRODUCTION

Economic development is a key priority within the Integrated Development Plan (IDP) of

138 African Journal of Public Affairsany municipality as it cements the way for the improvement of the quality of lives of com-

munities. In order for this to take place, among other things jobs need to be created as one

of the ways to develop the economy. Critical to this is the assurance that the IDP and budget

must be aligned. This article will therefore first conceptualise and contextualise economic

development, discuss economic development briefly and then within the context of mu-

nicipalities. Second, the importance of the IDP within the local sphere will be elaborated.

Emphasis will be placed on its statutory framework as well as the Service Delivery Budget

Implementation Plan (SDBIP) and the Annual Budget. Furthermore, the alignment of the

IDP, SDBIP and Annual Budget will also be discussed. Third, economic development within

the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality (COJ) will be focused on. The article

explains in detail economic development as a key priority within the COJ IDP 2016/2017,

the key economic development successes as well as the COJ economic development strat-

egy for 2016/2017. Fourth, an analysis of the COJ IDP 2016/2017 is done to determine the

aligning of the IDP, SDBIP and the Annual Budget, as well as to identify the gaps and policy

targets that have not been met in the implementation of the priority of economic develop-

ment in the 2016/2017 IDP and Annual Budget. Finally, a conclusion will be reached.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CONCEPTUALISED

AND CONTEXTUALISED

“Economic development usually refers to the adoption of new technologies, transition

from agriculture-based to industry-based economy and general improvement in living

conditions” (Business Dictionary 2018:1). Britannica (2018:1) concurs adding that eco-

nomic development is the process whereby simple, low-income national economies are

transformed into modern industrial economies. Economic development is the develop-

ment of economic wealth of countries, regions or communities for the well-being of

their inhabitants. From a policy perspective, economic development can be defined as

efforts that seek to improve the economic well-being and quality of life for a community

by creating and/or retaining jobs and supporting or growing incomes and the tax base

(Salmon Valley Business and Innovation Centre 2018:1). In the broadest sense, economic

development encompasses the following three major policy areas:

●● Policies that government undertakes to meet broad economic objectives includ-

ing inflation control, high employment, and sustainable growth.

●● Policies and programmes to provide services including building highways, man-

aging parks, and providing medical access to the disadvantaged.

●● Policies and programmes explicitly directed at improving the business climate

through specific efforts, business finance, marketing, neighbourhood development,

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 139business retention and expansion, technology transfer, real estate development and

others (IECD undated:3).

Furthermore, “Economic development is the expansion of capacities that contribute to

the advancement of society through the realisation of individual, firm and community

potential. It is measured by a sustained increase in prosperity and quality of life through

innovation, lowered transaction costs, and the utilisation of capabilities towards the

responsible production and diffusion of goods and services. Economic development re-

quires effective institutions grounded in norms of openness, tolerance for risk, apprecia-

tion for diversity, and confidence in the realisation of mutual gain for the public and the

private sector. Thus, it is essential to creating the conditions for economic growth and

ensuring our economic future” (Feldman, Hadjimichael, Kemeny and Lanahan 2014:12).

Therefore, from the above it can be deduced that economic development places

a strong emphasis on the transformation of the economy into a better, wealthier and

people driven environment. Imperative to this is the notion that economic development

must improve the quality of lives of communities by way of strong government policies

and programmes.

To this end Agarwal (2017) states that “a country’s Economic development is usually

indicated by an increase in citizens’ quality of life measured by literacy levels, poverty

rates and life expectancy”. The International Economic Development Council (IEDC)

(undated:41) also qualifies the ‘Quality of Life’ as the economic well-being, lifestyle,

and environment that an area offers. Improving the quality of life is the ultimate aim

of economic development programmes and initiatives. A balance has to be maintained

between encouraging the growth of the local economy, while limiting impacts upon

the quality of life. In this post-industrial new economy people are increasingly seeking

better quality of life, including: well-paid jobs, quality education/life-long learning, medi-

cal facilities, quality and affordable housing, low pollution and environmental damage,

public amenities, low crime, recreation, entertainment, and intellectual stimuli, low cost

of living/low taxation, aesthetic build and natural environment (IEDC undated:41).

Thus, a qualitative approach to economic development ensures an economy that enhances

the economic and social well-being of a community. Thanawala (1994:355) concurs af-

firming that the above represents those qualitative changes in the economic process which,

through carrying out new combinations of policies and programmes with already existing

means of production, brings about a dynamic and successful economic process.

The logic of economic development requires certain capacities that need collec-

tive action by government (Feldman, Hadjimichael, Kemeny, and Lanahan 2014:20).

140 African Journal of Public AffairsThis involves collective action and large-scale investments with long-term horizons.

Infrastructure projects, a traditional concern of economic development, now extend to

the digital realm. The standard of literacy is expanded at a time when labour force par-

ticipation requires a bachelor’s degree with the expectation of continued lifetime edu-

cation and training (Feldman, Hadjimichael, Lanahan and Kemeny 2016:7). “Economic

development is predicated on co-operation between the public and private sector, but

is defined by conditions established by government and public investments. Though it

is certainly possible to have growth without development in the short or even medium

term, economic development creates the conditions that enable long-run economic

growth. Rather than relying on the market-based rationales for public investment, it is

important to define the function of the public sector as building and bolstering the ca-

pacity for economic actors to realise their potential. Rather than viewing individuals,

firms, and communities as objects on the receiving end of public initiatives, economic

development requires that they be considered as active agents. This prioritises improving

quality of life and well-being by enhancing capabilities and ensuring that agents have

freedom to achieve their potential as productive members of society” (Feldman et al.

2016:14). Thus, ensuring that the public and private sector work in a mutually beneficial

manner to improve the quality of life of communities to enhance their economic capa-

bilities is crucial.

From the above it can be said that the result of economic development is greater eco-

nomic prosperity and higher quality of life. According to Feldman et al. (2016:17), this

can be realised through the increases in four dimensions of capacity outcomes. “Firstly,

community capacity involves the physical, social, and environmental assets that influ-

ence the context for economic development. Secondly, firm and industry capacity in-

volves the assets relevant to firms and industry, including workforce, facilities and equip-

ment, organisation, and supply chain. Thirdly, entrepreneurial capacity focuses on the

potential for generating new small businesses, including a risk-taking culture, networks,

and access to financial capital and a skilled workforce. Finally, innovative infrastructure

focusses on the capacity to support new products, processes, and organisations, in terms

of facilities, support services, and willingness to take risks. These capacities are overlap-

ping and mutually reinforcing”.

The factors affecting economic development can be divided into political, economic

and non-economic factors. Tanner (2017), Williams (2007) and Chand (2018) discuss the

following factors:

●● Political factors: The government-enforced policies and administrative norms

known as political factors can influence economic development, which is the

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 141process that increases standard of living by moving away from traditional farming

cultures to industrialised societies. These include:

●● Regime type is the form of government within a country. This includes whether

a country is democratic, authoritarian, communist, or other.

●● Political stability, or instability, refers to the reliability and durability of a gov-

ernment’s structures. The more stable a political system is, the less risk a busi-

ness operating in that country will face.

●● Political management refers to how well the government monitors and

enforces national and international policies or laws.

●● Level of corruption identifies the level of dishonest, unethical and illegal prac-

tices that are imposed on people and businesses

●● Economic factors: in a country’s economic development the role of economic

factors is decisive. These are:

●● Capital formation involves the role of capital in raising the level of production.

●● Natural resources of which the abundant existence is crucial.

●● Economic system must favour economic growth and development.

●● Non-economic factors: are just as important and influential as economic factors

and include:

●● Human resources must be skilled and efficient and contribute to growth.

●● Political freedom is key for positive economic development.

●● Social organisation involves participation in developmental programmes for

the community.

All these factors if harnessed positively can contribute to a well-balanced and productive

economic development. From the above, it can be deduced that economic development

cannot be defined as a single definition, it is all encompassing. Among other things it

focuses on transforming and improving the economy; working in a positive and mutually

beneficial manner with the private sector; developing sustainable government policies

and programmes; and ensuring that the political, economic, and non-economic factors

are harnessed positively to ensure the enhancement of economic prosperity and quality

of life of all communities. To achieve this, municipalities specifically play a crucial role.

Economic development in municipalities

Ferlaino (2018:1) states that: “Economic development at the municipal level is paramount

to the promotion of growth, accessibility and stability, and to establishing strong, cohe-

sive municipalities and regional partnerships in the realm of the global market economy.

Fostering municipal economic development requires strategy and co-operation to en-

sure a connection between the built environment, the social and cultural wellbeing of

142 African Journal of Public Affairsa community, and sustainable growth. (The built environment refers to buildings, trans-

portation, infrastructure, public spaces, natural systems and anything else that comprises

the community and helps it to operate)”. Morgan (2009:14) adds that economic devel-

opment advocates for strengthening the capacity of municipalities by ensuring greater

access to information and technical assistance; and connecting communities to valuable

ideas, resources and opportunities and sustaining local innovation.

“For a community to develop and sustain economic growth, an economic development

plan or strategy and associated provisions are necessary for unfettered success. Each

community must have a solid foundation and set of short and long-term criteria estab-

lished to maintain and sustain growth. Although municipalities are bound by legislation,

which limits the degree to which they can influence growth and economic development,

planning tools allow communities to work within the confines of the law to create acces-

sible and welcoming communities. This may include creating partnerships with neigh-

bouring communities, or building regional development plans to capitalise on economies

of scale” (Ferlaino 2018:1). The benefits of the integration of the economic develop-

ment strategies within the municipal plan are that: economic strategies are part of an

integrated plan for addressing municipal developmental challenges; municipal resources

are allocated to these strategies; the outputs and impact of the economic development

strategies and projects are monitored as part of the municipal performance management

system; and the role of the municipality within economic development is clearly defined

within each strategy (Harrison, Huchzermeter and Mayekiso 2003:183–184).

In order to achieve the above, municipalities must be assigned a variety of roles and re-

sponsibilities concerning economic development and this is confirmed in the Constitution

and the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000 (MSA). The Constitution

makes provision in Chapter 7 S152(1)(c) for local government to promote, among others,

economic development. Further to this, S153 adds that a municipality must structure and

manage its administration, budgeting, and planning process to give priority to the basic

needs of the community, and to promote its social and economic development of the

community. Vatala (2005:235) builds on this adding that the focal points for developing

municipalities are among other things service delivery, economic development and job

creation. Phago (2009:484) further argues that it is imperative “to strengthen the key

economic clusters to gain leverage from growth trends in manufacturing, government

and business services, building high levels of social cohesion and civic responsibility to

maximise development opportunities for the municipalities”. Gunter (2006:17) concurs

adding that the World Bank (2001, 2002) clearly articulates factors crucial to economic

development in municipalities. These include ensuring the local investment climate

is functional for local enterprise; supporting small and medium enterprise businesses;

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 143investing in infrastructure; supporting the growth of business clusters; and targeting cer- tain disadvantaged geographical areas and communities. Hence, the MSA makes it compulsory for all municipalities to draw up an annual and five-year IDP, which must contain a strategy to develop the local economy. Malefane and Mashakoe (2008:475) agree affirming that “the IDP has a legal status and super- sedes all other plans for local development and is meant to arrive at decisions on issues such as municipal budgets, land management, economic development and institutional transformation in a consultative, systematic and strategic manner”. Thus, it has become clear that should municipalities wish to ensure sustainability and resilience within their respective economies they have to play a key role in creating a conducive environment for investment through the provision of infrastructure; economic development friendly policies; and quality services, rather than by developing projects and attempting to cre- ate jobs directly (The Knysna Weekly 2015:1). Furthermore, Koma and Kuye (2014:102) aptly assert that the “purpose of economic development in municipalities is to create conditions conducive to propel and boost local economies and thereby addressing high levels of poverty, unemployment and inequalities facing the majority of the South African population and more importantly, ensure global competitiveness and the integration of the South African economy within the global economic context”. The role of municipalities in economic development cannot be underestimated. Legislation dictates exactly what municipalities must do in this regard and sets the path for economic development to thrive and flourish within the economy of the municipal- ity. Now that economic development has been discussed, emphasis will be placed on its role within the IDP. IMPORTANCE OF THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN AT THE LOCAL SPHERE The IDP is the focus of South Africa’s post-apartheid municipal planning system and is regarded as a key instrument in an evolving framework of intergovernmental planning and coordination (Harrison 2006:186). Specifically, Harrison (2006:187) adds that the White Paper on Local Government, 1998 identified the IDP as a key tool of develop- mental local government, meaning local government that is concerned with promoting economic and social development of communities. The White Paper further highlighted “the role of the IDP in providing a long-term vision for a municipality; setting out priori- ties of an elected council; linking and co-ordinating sectoral plans and strategies; align- ing financial and human resources with implementation needs; strengthening the focus 144 African Journal of Public Affairs

on environmental sustainability; and providing the basis for annual and medium-term

budgeting” (Harrison 2006:187).

This paved the way for the formulation of legislation to govern the role of the IDP in

municipalities. Thus, municipalities are required by law to prepare a principal strategic

planning instrument, known as the IDP. This five-year plan guides and informs all plan-

ning, budgeting and decision-making (DPLG 1998/1999:6). Chapter 5 S25(1) of the

MSA makes provision for the IDP. According to this section, municipalities must adopt

a single, inclusive strategic plan for the development of the municipality. This strategic

plan should link, integrate and coordinate plans and consider proposals for the devel-

opment of the municipality; align the resources and capacity of the municipality with

the implementation of the plan; form the policy framework and general basis on which

annual budgets must be based; comply with the provisions of this Chapter; and must be

compatible with national and provincial development plans and planning requirements

binding on the municipality in terms of legislation.

Phago (2009:484) states that “the IDP is a detailed planning process within a munici-

pality providing for prioritised community needs to enhance and accelerate municipal

service delivery”. The IDP allows municipalities to prioritise, combine and integrate

their multiple tasks and account for it in the budget (Reddy, Sing and Moodley

2003:208). Furthermore, the White Paper on Local Government, 1998 sums up that

the purpose of the IDP is to provide a framework within which municipalities can

understand the various dynamics operating within their area of jurisdiction, develop

a concrete vision for their areas and formulate strategies for financing and realising

their vision in partnership with other stakeholders. Thus, the IDP is a five-year rolling

strategic plan with a vision of ensuring the successful development of the community

in keeping with its legislative prerogative.

Section 26 of the MSA further explains the core components of the IDP, which provides

a benchmark for municipalities. An IDP must reflect:

●● the municipal council’s vision for the long-term development of the municipal-

ity with special emphasis on the municipality’s most critical development and

internal transformation needs;

●● an assessment of the existing level of development in the municipality, which

must include an identification of communities, which do not have access to basic

municipal services;

●● the council’s development priorities and objectives for its elected term, including

its local economic development aims and its internal transformation needs;

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 145●● the council’s development strategies which must be aligned with any national or

provincial sectoral plans and planning requirements binding on the municipality

in terms of legislation;

●● a spatial development framework which must include the provision of basic

guidelines for a land-use management system for the municipality;

●● the council’s operational strategies;

●● applicable disaster management plans;

●● a financial plan, which must include a budget projection for at least the next

three years; and

●● the key performance indicators (KPIs) and performance targets determined in

terms of section 41.

Added to the above Ackron (2010:45) and Mashamba (2008:425) identify the key per-

formance areas of an IDP within a municipality. These include, among others, spatial

planning: municipalities are required to compile a Spatial Development Framework,

which indicates municipal growth points, identifies strategic portions of land for devel-

opment and sets parameters for an efficient and effective land-use management system.

Good governance: IDPs should reflect the entrenchment of a good governance system

in municipalities through structures that ensure participatory democracy, transparency

and accountability. Local economic development: IDPs should include local economic

development plans that elaborate on strategies and programmes required to ensure lo-

cal economic growth, job creation and poverty reduction. Financial management and

compliance with the Municipal Finance Management Act, 2003: the IDP requires the

preparation of a municipality’s financial plans. These financial plans should outline the

interventions to ensure that municipalities attain financial sustainability. Success of these

financial plans implies adherence to the Municipal Finance Management Act. These ar-

eas drive the municipality to focus on the needs of the community and find sustainable

and effective ways of achieving the needs of communities. It is crucial to point out that

one of the key areas is the development of the local economy.

Once the IDP of a municipality has been drawn up, the next step is to prepare the SDBIP

for the municipality. The SDBIP is dealt with in Sections 53, 54 and 69 of the Municipal

Finance Management Act (MFMA), as well as in the National Treasury’s MFMA Circular

No 13. In Section 1 of the MFMA, the SDBIP is defined as a detailed plan that is ap-

proved by the municipality’s mayor for implementing the municipality’s delivery of mu-

nicipal services and its annual budget. It gives effect to a municipality’s IDP and budget

(Pillay 2005:1). According to Vatala (2005:230), the SDBIP has two layers. The top layer

has consolidated service delivery targets or goals and in-year deadlines. This layer can

be made public and includes the basic information, such as information on income and

146 African Journal of Public Affairsexpenditure that the municipal manager requires to ensure performance. A mechanism

should also be provided to project and monitor inputs, outputs and outcomes for each

senior manager. The second layer consists of more detailed information that is linked to

the top layer and breaks it down into detailed matters. Although the SDBIP is a one-year

detailed plan, it should include a three-year capital plan. Thus, municipalities are en-

couraged to include three-year (by quarter) service delivery targets, as well as past- and

current-year information in order to facilitate comparisons and to outline remedial steps

it is taking in terms of past problems (Pillay 2005:4). Therefore, the SDBIP can be seen

as one of the key implementation and monitoring tools and provides that municipalities’

operational functions meet the service delivery goals and objectives, as set out in the

IDP and budget.

Once the IDP and SDBIP have been formulated, the final step is to draw up the mu-

nicipal annual budget based on the IDP and SDBIP. This must be done with precision

to ensure that the alignment of the three is done to guarantee successful and effective

implementation.

Visser and Erasmus (2002:80) state that a budget is simply a document identifying

and stating particular objectives with associated expenditure linked to each objective.

Khalo (2007:187) defines a budget as a financial plan for a specific period in which

specific amounts are allocated for specific purposes. Moeti, Khalo, Mafunisa, Nsingo,

and Makondo (2007:83) add that a budget is a documented source of income on antici-

pated income and expenditure over a specific period. Fourie and Opperman (2007:96)

state that a budget is the most important mechanism to give effect to a municipality’s

service delivery strategies. It is imperative for municipalities to ensure that their budgets

are output-driven and that their intended outcomes are in line with their service delivery

strategies and objectives.

Fourie (2011:14) sums up stating that municipal budgets must be financially and stra-

tegically credible, as well as affordable. Public officials must take into account realistic

operating and capital expenditure, revenues and capital finance sources, as well as

developmental, administrative and service delivery priorities and targets set in the mu-

nicipality’s IDP.

As cited in Majam (2012:7), Fourie and Opperman (2007:96) state that traditionally,

municipal budgets are prepared on the basis of the accrual accounting principle (trans-

actions are brought to account in the financial year in which they occur, irrespective of

whether cash is paid or received in respect of such transactions during the financial year

concerned). The budget is divided into the capital and operating budget. According to

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 147Fourie (2011:76), the capital budget is an estimate of the capital expenses that will be incurred over the relevant year and the financial sources from which these expenses will be funded. It must be drafted before the operating budget and must be aligned with the priorities of the approved IDP. Aligning the capital budget with the IDP means that the municipality must look carefully at the projects and priorities envisaged in its IDP and then structure its budget accordingly. The problem that may be experienced is that the budget cannot accommodate all the priorities and projects in the IDP. According to Fourie (2011:72), the operating budget consists of an estimate of operating revenues that the municipality will accrue. Furthermore, it includes operating expenses that the municipality will incur over the financial year. Operating expenses include salaries, bulk purchases of electricity and water, rentals, transport costs and finance charges. Fourie and Opperman (2007:114) are of the view that the operating budgets are more set on historical perspectives than on future requirements, as required by the strategies con- tained in the IDP. Generally, the IDP is given effect through the capital budget, as this is where projects associated with improving service delivery are funded. Furthermore, the integration and alignment of a municipality’s IDP to the budget is crucial in addressing the process and allocation of public resources in support of government’s economic policy priorities. Mkhize and Ajam (2006:767) identify six stages towards in- tegrating and aligning the IDP to the budget. The first stage is to prepare the IDP and prioritise its planned objectives. It is important to ensure that the IDP guides the budget process as it establishes the key areas, strategic objectives and goals of the municipality. The second stage requires municipalities to assess the costs and resource implications of the revised IDP against the budget allocation. This is when costing and estimation takes place identifying the costing techniques, for example incremental or zero-based to be used. The third stage is for the municipality to finalise the budget allocations according to the priorities of the IDP and prepare the budget documentation. The fourth stage is for the municipality to monitor and reprioritise spending plans. This involves monitoring expenditure trends and reprioritising resources in line with changing priorities in the IDP. The fifth stage is to measure performance and service delivery. This stage focuses on monitoring and measuring performance and service delivery achievements against the municipality’s IDP. Finally, the last stage is to finalise the annual financial statements and reports in line with what has been achieved and should have been achieved within the IDP (Mkhize and Ajam 2006:770). This process if done systematically and correctly should ensure that the alignment and in- tegration of the IDP and the budget are effectively achieved. Crucial here is that there are clearly defined roles and responsibilities of employees, specific and strictly adhered to policies and procedures, and enough capacity for the municipality to be able to succeed. 148 African Journal of Public Affairs

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT WITHIN THE CITY OF

JOHANNESBURG METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY

According to COJ (undated: 3) the COJ is situated in Gauteng province, has a popula-

tion of 4.9 million people, and covers an area of 1 645km2 (IDP 2017/18: 8). The COJ

is the largest city in South Africa, and the provincial capital of Gauteng, the wealthiest

province in South Africa. The City’s primary economic sectors are finance and business

services, community services, manufacturing and trade. The COJ DED (2018) further

adds that Johannesburg ranks 104th out of 13 420 cities as an investment destination (i.e.

the top 1%). The City is also the No.1 City in Africa in terms of outward investment, and

has the highest concentration of banks and financial services, making it an ideal forward

operating base for any serious investor.

The COJ (undated:4) explains that the COJ enjoys economic strengths and strategic ad-

vantages, as well as considerable challenges to economic development. As described in

the City’s Economic Development Strategy (EDS) and IDP (COJ-Economic Development

Strategy (EDS) 2015:13; IDP 2017/18: 73), key strengths supporting economic develop-

ment include:

●● Local market scale: The population of COJ represents approximately 9% of the

national population.

●● Money and people are attracted to the City: The perceived opportunities for

work seekers, and those seeking improved livelihood opportunities, and access

to services, means that the City is attractive for economically active groups.

●● Latent and realised agglomeration effects: While COJ is the largest city in South

Africa, with a relatively diversified economy, it benefits from the economic ac-

tivities of the broader, highly urban Gauteng City Region (including Tshwane and

Ekurhuleni).

●● Globally recognised city, as a financial hub, and entry point into neighbouring

African markets: As such, the City is viewed as a viable location for corporate ac-

cess to Southern Africa and wider African continental opportunities. Further, the

strong financial sector is considered to boast high levels of integration to global

markets, and be supported by strong local institutions including good regulatory

and market infrastructure (City of JHB undated:4).

According to the COJ IDP (2016–2021:18) Johannesburg has a friendly business environ-

ment and has been successful in attracting investments. Deconcentrating the economy

has, however, remained a challenge. The dominance of trade and finance in Johannesburg

arose from its central location in South Africa’s geography, among other factors. This

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 149advantage can be contrasted to the lower concentration in agriculture and mining, which

is largely driven by the lack of natural factor endowments. Thus, Johannesburg needs

to continue boosting manufacturing production, both in terms of higher value-added

production and expansion into new and emerging neighbouring markets. Before the

2008/9 global crises, Johannesburg’s economy was one of the country’s fastest growing

regions at an average rate of 6% per year. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth

rebounded from the negative 1.7% in 2008 and is forecast to continue growing at an

average of 1%–2% in the short- to medium-term. Also in the short- to medium-term,

the COJ economy is likely to continue to be dominated by finance, community services

and trade. For Johannesburg to sustain its growth and avoid the middle-income trap, it

needs to pay attention to deconcentrating the economy while raising the productivity of

not only the manufacturing, but also the already strong, services sector. Higher levels of

education and skills as well as creativity, innovation, and competition will be necessary.

These would not only promote higher growth, but also inclusive growth, which will help

reduce the persistent high-income inequality in Johannesburg.

The COJ IDP (2016–2021:9) highlights four desired outcomes that must be achieved by

2021. These are:

●● Outcome 1: Improved quality of life and development-driven resilience for all.

●● Outcome 2: A sustainable city, which protects its resources for future generations,

and a city that is built to last and offers a healthy, clean and safe environment.

●● Outcome 3: An inclusive, job-intensive, resilient and competitive economy that

harnesses the potential of citizens.

●● Outcome 4: A high-performing metropolitan government that proactively con-

tributes to and builds a sustainable, socially inclusive, locally integrated and

globally competitive Gauteng City Region (GCR) good governance requires an

efficient administration, but also respect for the rule of law, accountability, acces-

sibility, transparency, predictability, inclusivity, equity and participation.

In line with these outcomes, COJ has translated 11 priorities that will address the chal-

lenges being faced in order to achieve the outcomes. These priorities include:

●● Priority 1: Economic growth, job creation, investment attraction and poverty

reduction

●● Priority 2: Informal economy and Small Medium Micro Enterprises (SMME)

support

●● Priority 3: Green and blue economy

●● Priority 4: Transforming sustainable human settlements

150 African Journal of Public Affairs●● Priority 5: Smart city and innovation

●● Priority 6: Financial sustainability

●● Priority 7: Environmental sustainability and climate change

●● Priority 8: Building safer communities

●● Priority 9: Social cohesion, community building and engaged citizenry

●● Priority 10: Repositioning Jo’burg in the global arena

●● Priority 11: Good governance (COJ IDP 2016–2021:34).

It can be clearly noted that Outcome 3 is translated into Priority 1 and 2 and this indi-

cates the commitment of COJ to economic development. Added to this, the COJ IDP

2016–2021 (2016–2021:9) outlines the importance of these two priorities. Concerning

Priority 1: Economic growth, job creation, investment attraction and poverty reduction;

economic development and job creation is of primary importance in the City. This is

evident through three priorities that have been identified focusing on economic growth

and development. This includes facilitating economic growth in Johannesburg through

initiatives such as the creation of Urban Development Zones (UDZs) as a tax incentive

measure for private investment and Business Process Outsourcing Parks. The City is also

cognisant of the effect service delivery and maintenance of essential services infrastruc-

ture have on economic development and has, therefore, prioritised basic service repairs

and maintenance. The City will continue to ensure that wherever possible, the projects

implemented are done through the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) to allow

for greater creation of jobs and development of skills for the unemployed. This priority

seeks to contribute to economic growth through investment attraction, retention and

expansion. It is geared towards developing Johannesburg as an attractive destination

for investors. Key areas of focus include the identification and packaging of city-wide

investment projects, facilitation of investment activities (eg through the establishment of

investment engagement opportunities), provision of aftercare services, investment policy

advocacy, and fostering positive partnerships with stakeholders involved in the promo-

tion and facilitation of investments (COJ IDP 2016–2021:9).

Key to ongoing and increased attraction, retention and expansion of investments is

the establishment of an environment in which potential investors feel confident about

the potential for sustainable long-term returns. The City has an opportunity to lever-

age its 10-year R100 billion capital investment programme to boost investor confidence.

Through this programme, the City is well positioned to package and promote investment

opportunities. Food security is critical to development and poverty alleviation: without

food, people cannot lift themselves out of poverty, while poverty in turn fuels food in-

security, creating a destructive cycle of impoverishment. If the intention of this priority

is met in full, the experience of food insecurity, hunger and malnutrition will be a thing

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 151of the past. The roll-out of a combination of interventions is necessary for this outcome

to be realised. Efforts would need to focus on targeting improved food safety and nutri-

tion, increasing domestic food production and trading, and enhancing job creation and

income generation associated with agriculture and food production (all of which are

elements of the Integrated Food Security Strategy) (COJ IDP 2016–2021:9).

Johannesburg currently faces varied challenges concerning hunger and malnutrition

among the urban poor, and especially women and children. Food insecurity among the

urban poor is high. This challenge is exacerbated by the fact that the majority of the

urban poor live far from the city centre, with much of their income spent on transport

and food. The health of those living within the city of Johannesburg is also compromised

by lifestyle diseases that frequently emerge alongside rapid urbanisation, with these con-

tributing significantly to mortality rates among both the poor and middle strata (COJ

IDP 2016–2021:9).

Concerning Priority 2: Informal economy, and SMME support; the priority of ‘SMME and

entrepreneurial support’ targets the provision of support to SMMEs and entrepreneurs

– recognising the importance of these role-players in absorbing labour, and in develop-

ing, growing and improving the health of the urban economy. This priority is focused

on improving the reach, coordination and effectiveness of SMME and entrepreneurial

development activities throughout the City. It also targets establishment of the necessary

conditions and support for SMMEs. Closely aligned to this is the City’s emphasis on pro-

viding opportunities for the informal sector (e.g. through the City’s delivery initiatives).

Attainment of this priority will ensure Johannesburg consolidates its position as a leading

economic centre, involved in championing the growth of SMMEs and entrepreneurs.

This will be achieved through a focus on addressing the factors that enable SMMEs and

entrepreneurs to easily access markets, earn a sustainable livelihood and expand–and

with this, contribute to increasing employment opportunities. The informal sector will be

supported, serving as a foundation for growth of further entrepreneurialism, improved

self-sustainability and job creation (COJ IDP 2016–2021:10).

Furthermore, the COJ (undated:20) outlines the COJs key economic development suc-

cesses, namely:

●● Identifying catalyst clusters in each of the regions that can be upscaled because of

their proven economic benefit and ability to generate job opportunities. The clus-

ters are identified because of their financial and social spinoffs. For example, in

Soweto, the COJ identified the fashion and textile cluster, and the Soweto Fashion

Week is a flagship project within the Economic Development Directorate.

152 African Journal of Public Affairs●● The use of the preferential procurement process to support SMME development.

The COJ has a directive on its procurement policy stating that if a certain project

exceeds a certain amount then the contractor must ensure that they subcontract

30% of that project to an SMME. The manufacturing industry SMMEs are benefit-

ting greatly from the stringent monitoring observed to ensure that the directive is

carried out.

●● Re-stitching the city and identifying new growth corridors: The Corridors of

Freedom initiative is aimed at re-stitching the city thereby readdressing apartheid

city planning. Through the initiative residents can work, play and stay within the

same space without high travel costs. The transit-oriented development’s BRT sys-

tems and REYA Vaya are the heart of the corridors as they offer affordable mobility.

There are three currently established services namely Empire-Perth Corridor con-

necting Soweto to the CBD and Auckland Park; Louis Botha Corridor between the

Jo’burg CBD, Alexandra, Sandton and Ivory Park; and the Turfontein Corridor along

City Deep, freight and logistics hub. Due to the City’s increased investments into the

corridors, they have become highly attractive to investors, contributing to the estab-

lishment of new anchor points of economic development. As a result, this initiative

has contributed to increased economic activity and job opportunities in previously

marginalised areas such as Soweto and Alexandra.

●● The EPWP programme is an upskilling and empowerment programme. The

programme is aimed at alleviating poverty and increasing job opportunities for

the citizens of the COJ. The programme makes use of public sector budgets to

draw significant numbers of the unemployed into productive work while enabling

these workers to gain skills. The City has committed a unit to coordinate, monitor

and evaluate progress in the implementation of EPWP projects. The City has an

EPWP policy and implementation framework, which was approved by council.

Suitable projects are identified for inclusion in the City’s EPWP programmes.

●● Jozi SME Hubs are centres of entrepreneurial support and excellence. Situated

in each region–seven regions–the hub offers a stop-shop to start-up and estab-

lished entrepreneurs. The Jozi SME Hub model is unique in that each branch is

strategically developed to address the needs of the local economy and business

environment. The client has access to an array of services such as information

on how to source funding; legal advice, information on how to access business

opportunities, internet access; networking opportunities; tender facilitation; and

access to the hub’s facilities i.e. training rooms. .

It is evident that significant strides are being made to enhance the economic capabilities

of the COJ, as well as improve the quality of life of communities. As established earlier in

the article, this is exactly what economic development entails.

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 153CITY OF JOHANNESBURG’s CURRENT ECONOMIC

DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY AND PLAN

The COJ IDP 2016–2021 (2016–2021:45) outlines the EDS used to achieve Outcome 3.

What is required is an inclusive, job intensive, resilient and competitive economy that

harnesses the potential of all citizens and is aligned with, and supplemental to, exist-

ing mandated City policy frameworks, initiatives, programmes of action and strategies.

The development of the City’s strategies, priorities and plans has been a cumulative

evolutionary process with political mandating and stakeholder consultation at its heart.

Over the past 20 years, a transformation and prosperity-focused vision for the City

emerged, with strategies and plans developed to advance the City towards the vision.

The City’s current economic development blueprint is the Fifteen Point Economic

Development Plan. The Plan has the Jo’burg 2040 City Vision as its foundation and is

informed by the City EDS of 2008/2009, and the City Economic Transformation Policy

Framework of 2011. The Plan is also informed by National and Provincial imperatives,

policies, and plans including the National Development Plan and New Growth Path

(COJ IDP 2016–2021:48).

Specifically the COJ IDP 2016–2021 (2016–2021:48) encapsulates that the Fifteen

Point Economic Development Plan has three agendas into which the 15 elements are

organised:

●● Improving overall competitiveness of the City

●● Benchmarking City processes and efficiencies against competitors and target-

ing best practice benchmarks.

●● Fast-tracking City decision-making on a portfolio of key economic projects.

●● Ensuring effective research, intelligence gathering and investment decision-

making criteria underpin the identification and prioritisation of City expenditure.

●● Include community co-production of goods and services for the City to create

jobs and incomes and incubate new business.

●● Undertaking an industrial-spatial economy programme

●● Ensuring competitive suppliers are developed for regional and local commer-

cial markets with an initial focus on the “Green Economy”.

●● Improving City regulation for the Green Economy sector including, buildings,

housing and infrastructure.

●● Focusing economic development initiatives on specific manufacturing value-

chains and linkages across value-chains.

●● Adopting a sector strategy investment portfolio approach to spatial planning

and to the release of zoned land.

154 African Journal of Public Affairs●● Establishing a long-term investment strategy and financing mechanism includ-

ing early stage and development financing partnerships.

●● Improving role-player accountability and implementation

●● Ensuring interventions are accommodated by the Municipal Finance and

Management Act and procurement and SCM strategy.

●● Seeking co-management of interventions with key economic stakeholders.

●● Developing joint programmes with universities, higher education institutions

and science and technology centres in Johannesburg.

●● Strengthening economic strategy coordination across City departments and

entities.

●● Ensuring active City-Business forums with senior-level participation and a

focus on a key-project portfolio.

●● Establishing a Competitiveness Council with participation by the City, busi-

ness and other key role-players.

In addition to the generalised points above, there are specific spatial elements to the

EDS. These include:

●● Ensuring the continued success of the spatial zone, currently the mainstay of the

City’s economy and the source of the bulk of the City’s revenue.

●● Enabling a larger proportion of the population to participate in and benefit from

the high performing spatial economic zone through spatial development initia-

tives such as the Corridors of Freedom.

●● Establishing new and expanding old industry nodes to broaden and grow the

manufacturing base of the economy and take jobs closer to people.

●● Establishing small business incubators in all industry nodes to expand the small

business sector and improve small business sustainability and growth prospects

(COJ IDP 2016–2021:49).

COJ is determined that by achieving each of the above EDS priorities, eventually out-

comes will be successfully achieved.

An analysis of the COJ’s performance on the 2016/2017 COJ SDBIP annual plan, used to

implement the IDP, will be discussed below. The main focus will be on SDBIP’s Priority

1, which focuses on “Economic growth, job creation, investment attraction and poverty

reduction”. The following section reports on the COJ’s actual performance on economic

development objectives against the planned targets as derived from the Municipality’s

IDP and SDBIP.

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 155THE COJ’s PERFORMANCE ON PLANNED SDBIP TARGETS IN 2016/2017 PRIORITY 1: ECONOMIC GROWTH, JOB CREATION, INVESTMENT ATTRACTION AND POVERTY REDUCTION The following paragraphs identify within the economic development objectives the targets that have not been met in the SDBIP 2016/2017, with a view to determin- ing why there are policy gaps and to make policy recommendations for improve- ment. Cloete (2009:296) is one of the many authors who define evaluation as “gap analysis” and then identifies and outlines: “Ongoing evaluation, formative evaluation and summative evaluation” as the three types of evaluation. Cloete classifies these different time-bound kinds of evaluation as “ex- post” and “ex-ante” evaluations. The former looking at the status quo ante (so-called baseline data: before the policy project was initiated), and the later looking at the cut-off point which signals the end of the evaluation period (so-called end or culmination data) (Cloete 2017:49). The analysis in this article is both “Progress (on-going) evaluation” if one considers that the SDBIP which is being evaluated forms part of longer term (five years) IDP for the COJ. The analysis in this article is, however, “summative evaluation” if one considers that it uses the data that was compiled by the COJ as part of its end of the SDBIP one-year implementation term (2016/2017). Evaluation therefore depends on the availability of evaluation data both about the status quo ante (so-called baseline data: before the policy project was initiated), and at the cut-off point which signals the end of the evaluation period (so-called end or culmination data). The better the quality of these different sets of data, the more accurately evaluations can be con- ducted. Experts on policy monitoring and evaluation (M&E) argue that “any policy, programme, or project implementation will come to no avail if one is not able to as- sess whether one has hit the intended target; or whether one missed it and by what margin” (Cloete & De Coning 2011:196). In line with the IDP, the COJ’s SDBIP economic growth cluster focuses on four major thrusts: economic growth, job creation, investment attraction and poverty reduc- tion. The SDBIP also sets the key performance indicators and targets for each of the four economic focuses. The KPI for economic growth target is “% increase in the City’s GDP growth”, the KPIs for “Job Creation” are the “Number of jobs created city- wide” and “Number of community work opportunities created city-wide”. The KPI for “Investment Attraction” is measured in terms of “Rand value investment attraction within the City”, and the KPI for “Poverty reduction target” is measured in the “% re- duction in household food insecurity in 39 most deprived wards [in the COJ] through enabling qualifying households”. 156 African Journal of Public Affairs

Hence this article focuses on the 2016/2017 financial year (FY) where all the analysis is

based on the data for the 2015 FY as baseline data and the 2016/2017 data for culmina-

tion/current or actual performance data. That is, the data that is compared to determine

whether the COJ has been successful or has failed to achieve the IDP and SDBIP “eco-

nomic cluster” objectives as listed in Priority 1. The authors of this article will thus con-

sider and compare the baseline data (2015/2016) and the culmination data (2016/2017)

which has been reported by the COJ in its 2016/2017 COJ SDBIP.

The analysis of the 2016/2017 SDBIP for the COJ provides the following five major findings:

●● The first KPI of the COJ referred to as “economic growth target” uses “1.6%

increase in the City’s GDP growth” achieved in 2015/2016 as baseline for

2016/2017. The COJ report shows that the target it set to achieve is 1.6% GDP

growth in 2016/2017 FY has achieved exactly “1.6% increase in the City’s GDP

growth” in “2016/2017”. Thus, the baseline data of (1.6% GDP growth in the

2015/2016 FY) is equivalent to the COJ target of 1.6% GDP growth set for the

2016/2017 FY. Therefore, the COJ baseline data for the 2015/2016 is equivalent to

the culmination data for the 2016/2017 on this indicator.

●● The second KPI of the COJ for economic development is referred to as “Number

of community work opportunities created city-wide”. The COJ uses the “51 977

community work opportunities” it “created city-wide” in 2015/2016 as baseline for

the 2016/2017 FY. The COJ report shows that it has achieved “23 227 community

work opportunities created city-wide” in the 2016/2017 FY which it calls “2016/17

Target”. Thus the baseline data for this indicator is 51 977 community work oppor-

tunities created in the 2015/2016 FY and the culmination data is 23 227 community

work opportunities which was achieved by the COJ in 2016/2017 FY.

●● The third KPI of the COJ is called “Number of jobs created city-wide”. The COJ uses

the “24 802 jobs created city-wide” in the 2015/2016 FY as baseline and the “25

000 jobs created city-wide” in the 2016/17 FY as culmination data or “Target”.

●● The fourth KPI of the COJ is called “Rand value investment attraction within the

City”. The COJ uses the “R3.26 billion investment attraction within the City”

it achieved in 2015/2016 as baseline and the “R4 billion investment attraction

within the City” as culmination data or “Target” for the 2016/2017 FY.

●● The fifth and final KPI of the COJ is known as “% reduction in household food

insecurity in 39 most deprived wards through enabling qualifying households”.

The COJ did not achieve any “0%” performance because it was the first time

it introduced this KPI. That is, the COJ has achieved 0% in 2015/2016, which

is taken as baseline for 2016/2017 FY. By the end of the 2016/2017 FY, the COJ

achieved “0.5% reduction of poverty in the City” which it calls “2016/17 Target”.

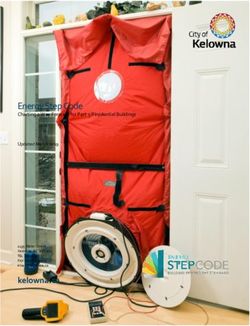

Volume 10 number 4 • December 2018 157Table 1: Performance on Planned SDBIP targets in 2016/2017

158

IDP Programme Key Performance Indicator Baseline 2015/16 2016/17 Target Annual Performance

Target not met

18820 community work opportunities created

city-wide. Performance was affected by

Economic Growth, Job compliance requirements introduced by the

1. No. of community work 51 977 community 51 977 community 23 227 community new reporting requirements on EPWP

Creation, Investment

opportunities created work opportunities work opportunities work opportunities

Attraction and Poverty Mitigation: Monitor implementation of

city-wide created city-wide created city-wide created city-wide

Reduction the community work opportunities created

city-wide. Alternative models of job creation

to replace previous interventions will be

implemented

Economic Growth, Job

Creation, Investment 2. No. of jobs created city- 24 802 jobs created 24 802 jobs created 25 000 jobs created Target met

African Journal of Public Affairs

Attraction and Poverty wide city-wide city-wide city-wide 25941 jobs created city-wide.

Reduction

Economic Growth, Job

Creation, Investment 3. % increase in the City’s GDP 1.6% increase in the 1.6% increase in the 1.6% increase in the Target met

Attraction and Poverty growth City’s GDP growth City’s GDP growth City’s GDP growth 1.6% increase in the City’s GDP growth

Reduction

Economic Growth, Job

R3,26 billion R3,26 billion R4 billion investment Target met

Creation, Investment 4. R

and value investment

investment attraction investment attraction attraction within R4.451 billion investment attraction within

Attraction and Poverty attraction within the City

within the City within the City the City the City

Reduction

Target not met

0 % reduction of poverty in the City. However,

5. % reduction in household 3301 households benefitted from homestead

Economic Growth, Job gardens and 358 households benefitted from

food insecurity in 39 most

Creation, Investment 0.5% reduction of 9 communal gardens.

deprived wards through New –

Attraction and Poverty poverty in the City

enabling qualifying Mitigation: The City has adopted pro-poor

Reduction

households governance that will contribute to reducing

poverty and its impact in designated wards

in the City

Source: (COJ SDBIP 2016/2017:109)You can also read