What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement? - Literature review and qualitative stakeholder work - Sutton Trust

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement? Literature review and qualitative stakeholder work Professor Chris Pascal, Professor Tony Bertram and Dr Aline Cole-Albäck, Centre for Research in Early Childhood

Key Findings – Literature Review

The 30 hour policy Take-up

• In England, there is an entitlement to • Take-up rates of the free entitlement

universal part-time early education for for two-year-olds and the universal offer

three- and four-year-olds, and targeted for three- and four-year-olds in all sectors

early education hours for less advantaged has declined over the last year, but

children from the age of two. take-up of the two year old entitlement

in the maintained sector has increased.

• Since 2017 there can be seen to be a

There is significant variation in take-up

policy shift in England to focus more on

by region and socio-economic status.

supporting ‘working families’, rather than

Take-up rates for children with special

families living in poverty or disadvantage,

needs and disability have been particu-

through extending the hours of funded

larly affected by the COVID pandemic.

places for three and four year olds from

15 to 30 hours and also offering childcare • Childcare choice and take-up is influenced

tax advantages and additional benefits, by both provider-related factors such as

for those in employment. sufficiency, cost/funding and flexibility

of provision and parent-related factors

• The introduction of the 30 hour entitle-

such as personal preference, awareness

ment has created a system in which the

of entitlements and eligibility. The issue of

very poorest children are given greater

quality does not appear to be a factor in

access to funded early education and care

parent choice and take-up, meaning the

at the age of 2, but where many of these

market is not driving sector improvement

same children are then given access to

or enhanced access.

fewer funded hours than better-off

children at the ages of three to four. • Parent-related factors are influenced

by socio-economic disadvantage, English

as an additional language (EAL), ethnicity,

population mobility, special educational

needs and disabilities (SEND) and employ-

ment status.

• Research suggests that with greater flexi-

bility of provision, support for parents new

to an area and those of children with EAL

and SEND, together with a better under-

standing of the benefits of early education,

parents would be more likely to take up

funded entitlements. Some parents will

still prefer for their child to start formal

early education when their child is older,

thus limiting take-up rates achievable.

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Key Findings 18• For parents of children with SEND there

School Readiness

are additional barriers to take-up, includ-

and Attainment Gap

ing lack of awareness and understanding

with regard to eligibility; fear of stigma-

• The attainment gap between more and

tisation; and concerns over the ability of

less advantaged children is increasing,

staff to deal with a child’s additional needs.

after a period of improvement. It is sug-

• There is some evidence that a lack gested that the COVID pandemic might

of impact of the entitlements on child have further escalated this widening.

outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged

• Closing the gap requires a holistic,

children, may be due to lower hours of

complex and sustained approach,

access and lower qualifications of staff

supported by a highly trained and

in settings serving these communities. It is

stable workforce.

suggested that action on enhancing staff

qualifications across the sector is needed • There is some evidence that the 30 hour

if free entitlements are not to further extended entitlement for working families

disadvantage the less advantaged. may be contributing to the widening

in the attainment gap by doubly advan-

taging the better off with additional

Quality hours. Accessing fewer hours, com-

bined with attendance at settings with

• Despite a widening of the attainment lower qualified staff, can mean lower

gap in child outcomes in the last few attainment for the less advantaged.

years, Ofsted inspections indicate that

• There is some evidence that a strategy

the majority of the early childhood

to both increase the funded hours and

education and care (ECEC) sector

enhance practitioner qualification in set-

offers high quality provision.

tings for the less advantaged would lead

• A key factor in quality ECEC is the to better outcomes for the less advan-

qualification level of the workforce, taged and a closing of the attainment gap.

yet this is deteriorating across the sector

• There is evidence that the early

and means fewer children are accessing

years pupil premium (EYPP) could further

provision with a qualified graduate

enhance child attainment for the less

or teacher.

advantaged, but only if it is adequately

• Recent policy choices have emphasised funded, well targeted and easier

increasing the number of childcare/early to administer.

education places for working parents

rather than enhancing the quality of

education provision through employing

highly trained staff.

• It is suggested that a blurring of

the policy intention between childcare

and early education means the quality

debate is confused.

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Key Findings 19• There is acknowledged government

Universal versus

concern about the loss of time in settings

Targeted Provision

and schools leading to learning loss.

The lower take-up of funded places since

• Evidence shows the benefits of universal

the pandemic is continuing to cause

provision above targeted provision in

concern for children’s learning potential

closing the attainment gap, as long as

and progress.

take-up rates amongst the less advan-

taged are high. It is suggested that • There is evidence that parental concerns

universal provision encourages a social about health and wellbeing are leading to

mix amongst children, attracts more a continued reluctance to allow children

highly qualified staff, removes stigma to engage in centre based ECEC, which

and encourages take up of places. again is more prevalent in less advantaged

communities and for children with SEND.

• Targeted provision has multiple barriers

to access for the less advantaged and

can lead to longer term problems for

Impact of Formal Hours

the beneficiaries and more inequality

in Childcare

rather than less.

• It is evident that access to high quality

ECEC can result in positive benefits for

Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic

all children, and especially less advan-

on the Development of Children

taged children, particularly in relation

to enhanced language and social skills.

• The pandemic has increased and

While evidence on the optimal number of

exposed the financial vulnerability of

hours is unclear, indications are that this

the ECEC sector, with many providers

is higher than the current universal enti-

suggesting their futures are no longer

tlement of 15 hours.

sustainable. This has implications

for the sector’s capacity to absorb • Evidence indicates a range of between

any enhanced entitlements. 15–25 hours a week after the age of two

years as being positive as long as provision

• The experiences and impact of the

is of high quality. There is also evidence

pandemic on young children have had

of a positive association with children’s

less visibility at policy level than for older

outcomes when attendance is for more

children, leading to a lack of awareness

than 15 hours in graduate led settings.

in policy responses.

• There is some evidence of the negative

• There is emerging evidence that the

impact on socio-emotional outcomes

lack of experience in early years settings

of children spending too many hours and

due to the pandemic has impacted

starting too early in formal ECEC.

significantly and disproportionately

on the development and learning of less • There is some evidence that the negative

advantaged children and children with effects can be mitigated by a more highly

SEND. This is particularly in the areas of qualified workforce.

Communication and Language, Personal,

• The number of hours and the timing of

Social and Emotional development,

these hours can also impact on positive

and Literacy.

or negative outcomes for children.

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Key Findings 201

Introduction and Methodology

Introduction However, there are two key and different drivers

to each of these funded programmes: early

The early years 30 hours policy, (also known as education for the universal and the two-year-old

the ‘extended entitlement’), was introduced for targeted offer; and childcare to support working

eligible three- and four-year-olds of qualifying parents for the additional 30 hours entitlement.

parents or carers in England in September 2017

(for more details on eligibility, see Box 1 below). The introduction of the 30 hour entitlement has

also created a system in which the very poorest

The policy was primarily designed to support children are given greater access to funded early

access to affordable childcare for working education and care at the age of 2, but where

parents, and was provided additionally to the many of these same children are then given

universal free entitlement of 15 hours of funded access to fewer funded hours than better-off

early education for all three- and four-year- children at the ages of three to four.

olds, and to the 15 hours available to 40% of

the most disadvantaged children from the

age of two years.

Box 1: Eligibility for the 30 hour entitlement

Eligibility for the 30 hours entitlement Self-employed parents and parents on zero-

is determined by a means-test based on hour contracts are eligible if they meet the

minimum and maximum earnings. Under average earnings threshold. Parents can still

the extended entitlement, eligible children be eligible if they usually work but:

of qualifying parents are provided with

570 hours of funded childcare in addition to • one or both parents are away from work

a universal entitlement of 15 hours of early on statutory sick pay;

education from the age of three, or two if

• one or both parents are on parental,

you are disadvantaged.

maternity, paternity or adoption leave.

To qualify for 30 hours of free childcare, each

In addition, parents are eligible if one parent

parent (or the sole parent in a single parent

is employed, but the other:

family) needs to earn on average, the equiv-

alent of 16 hours on the national minimum

• has substantial caring responsibilities

wage per week and no more than £100,000

based on specific benefits for caring,

per year. A family with an annual household

is disabled or incapacitated based on

income of £199,999 would be eligible if

specific benefits.

each parent earns just under £100,000.

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 1 21This policy analysis and literature review sets out • What is the nature of gaps in education

to generate an evidence base which can inform development and school readiness, and what

future priorities for government early childhood impact has the current 30 hours policy had

and care (ECEC) policy, with a focus on improv- on these?

ing outcomes for children from lower socio-

• How has the prevailing government

economic backgrounds. Specifically, it aims to:

view of early years provision as childcare

rather than early education impacted

1. summarise existing research on the

on the quality of provision, for example

30 hours policy;

through lack of funding?

2. look at potential impacts of the Covid-19

• What impact has the pandemic had on

pandemic (both on the early years sector and

the development of pre-school age children,

on child and family needs);

with a particular emphasis on socio-

3. summarise some of the policy options for economic gaps?

reform and identify pros and cons of each.

• How many hours are enough? Does it need to

be 30, and in what pattern of delivery, what is

known currently about this?

Review Methodology

To allow for a rapid turnaround, the review of

The literature review and policy analysis was

literature and policy primarily focuses on:

desk based and conducted in line with a

methodical review as defined by Cole-Albäck

• existing reviews and sources;

(2020) to allow for a rapid turnaround, to help

inform spending decisions coming out of the • evidence from 2017 to 2021 (and beyond

pandemic. A methodical review is similar to a this time frame where appropriate);

systematic review (Booth et al., 2012) in that it is

• evidence from England and the rest of the UK,

comprehensive, rigorous and transparent fol-

especially Scotland.

lowing a set protocol of established timeframes,

base criteria, agreed keywords and a synthesis

The review includes literature from websites,

of the evidence base. Published studies were

peer reviewed articles from the ERIC and BEI

included depending on their relevance to the

database, sources from reference lists (snow-

aims of the review.

balling) and grey literature. For the ERIC and BEI

database searches, the following base criteria

The policy analysis and literature review set out

were used: full text; peer reviewed; academic

to generate an evidence base to inform future

journals; from OECD countries; from 2017 (when

priorities for government policy. To meet the

the early years 30 hours entitlement for some

review aims the analysis of the evidence on

working parents was introduced). The keywords

England’s ECEC policy was framed to address

used can be found in Appendix 1. Results for

these four agreed questions:

searches using Research Indexes (BEI and ERIC)

can be found in Appendix 2.

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 1 222

Review of Early Childhood Education

and Care Policies in England

Before going on to look at the 30 hours policy to be meant as a temporary solution to an

in detail, the next section briefly summarises insufficient number of places in state provision,

early childhood and care policies in England, this arrangement has largely remained until

to give context to issues related to the today, with inherent problems as raised by Chen

30 hour entitlement. and Bradbury (2020), and discussed further in

Section 3. The legacy of this policy history is

Key policies in England can be grouped under very evident in the current ECEC system, which

four broad areas according to Stewart and is diverse and fragmented and still largely split

Reader (2020): parental leave; support for between ‘education’ and ‘care’ providers.

parents and parenting; high quality Early

Childhood Education and Care (ECEC); and In 1996 the Conservative Government had

financial support through cash benefits. It is introduced a free entitlement for part-time

the latter two that are of particular interest in early education for all four-year-olds. In 1998

this report and whether the balance is right in the Labour Government extended this free enti-

England between investing in affordable child- tlement to all three- and four-year-olds. By 2005

care for working parents, and supporting child take-up of this extended offer meant that access

development by investing in high quality early to free, part time early education for three- and

education. This section summarises key polices four-year-olds had almost become universal.

in each of the UK nations in relation to these The entitlement was initially for 2.5 hours a day

two ECEC agendas. (12.5 hours a week) for 33 weeks a year, but was

expanded to cover 15 hours a week (which could

be taken flexibly over fewer days) for 38 weeks

Changes over time a year. The Labour government also promoted

childcare as part of a National Childcare

Policy concern for the youngest children can Strategy, its flagship policy of Sure Start local

be identified in legislative changes made programmes (announced in 1998) and through

throughout the 20th century. In the early 1900s the tax and benefit system. The Sure Start pro-

the ‘new’ nursery schools were promoted as the gramme was superseded by the establishment

solution for the education of poor children and of Children’s Centres, a universal programme

although the idea that nursery education may be rather than one for disadvantaged areas as in

beneficial for all children was there in the 1940s, the case of Sure Start local programmes. The

this did not take off as nursery schools contin- intention of this policy was to create a ‘double

ued to be seen primarily as needed for the most dividend’ by promoting good quality childcare

deprived or neglected children and children of which would enhance children’s development

working mothers (West, 2020). It was not until and encourage parental employment (Strategy

the 1970s, after the Plowden Report (DES, 1967), Unit, 2002). The provision for places was not

that the idea of universal nursery education secured through an expansion of maintained

begun to take hold, as proposed in the White provision but rather through stimulating the

Paper Education: A framework for expansion private market for childcare and early education

(DES, 1972), but with recognition that private and that had grown significantly. The free entitlement

voluntary providers would need to ‘fill the gap’ in could be accessed at a local authority nursery

state provision (West, 2020). Although it seemed school, a nursery class in a maintained school,

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 2 23or at a private, voluntary or independent setting 2. The two year old entitlement is intended to

or with a child-minder (Lewis, 2011). broadly cover the 40% most disadvantaged

children and to offer them access to 15 hours

In 2013, the Coalition government commissioned of funded early education. Eligibility targets

two new early years policy documents, More families on low incomes (those on Universal

Great Childcare and More Affordable Childcare, Credit or who receive tax credits) and chil-

which focused specifically on extending child- dren who are vulnerable for other reasons,

care to support working parents. It is argued that such as looked after children or children in

this policy illustrates the switch of early years care, and children with Special Education

policy to focus almost entirely on extending Needs or with a disability. These funded

childcare rather than early education (Lloyd, places can be provided by registered child-

2015). However, from September 2013, the free minders, private and voluntary day nurseries,

entitlement to 15 hours of early education was preschools, maintained nurseries and schools.

extended to two-year-olds from low income Again, the focus is ensuring these less advan-

families by the Coalition Government. It is argued taged children receive early education that

that this inability to reconcile competing early can help boost their attainment and ‘close

years policy rationales has led to a lack of coher- the gap’ in their development and learning.

ence and progress in social mobility (Moss, 2014;

3. Since September 2017, three and four year

Brewer et al, 2014; Paull 2014).

olds with working parents are entitled to a

free nursery place equivalent to 30 hours

per week over 38 weeks of the year. This is

Recent policy in England

known as the extended entitlement (DfE,

2018). These funded places can be provided

By 2017 the government supported universal

by registered childminders, private and volun-

and free entitlements had been extended signifi-

tary day nurseries, preschools, maintained

cantly, as described below, to meet the needs of

nurseries and schools (see more details in

40 percent of disadvantaged two-year-olds and

section 1.1). The extended entitlement is

all three and four year olds (West, 2020). The

specifically targeted at working families to

30 hour extended entitlement for three year olds

enhance their access to affordable childcare.

built further on this developing system of ECEC

support. In summary, there are currently three

In addition to these three policy initiatives, in

main funded programmes:

2017 the Early Years National Funding Formula

(EYNFF) was set up for delivering the universal

1. The universal entitlement for all three-

and additional entitlements. The Department for

and four-year-olds to 570 hours of free

Education (DfE) provides Local Authorities with

early education provision per year, typically

six relevant funding streams for the free entitle-

taken as 15 hours per week over a minimum

ments as follows (ESFA, 2020b: 4):

of 38 and a maximum of 52 weeks of the

year. Children are eligible from the start of

1. The 15 hours entitlement for disadvantaged

the term after they turn three until they start

two-year-olds;

Reception year. These funded places can be

provided by registered childminders, private 2. The universal 15 hours entitlement for three

and voluntary day nurseries, preschools, 3- and four-year olds;

maintained nurseries and schools. The

3. The additional 15 hours entitlement

focus of this policy is to ensure all children

for eligible working parents of three-

have access to quality early education

and four-year olds;

to ensure school readiness prior to entry

to compulsory schooling.

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 2 244. The early years pupil premium (EYPP); above, due to Covid-19, Local Authorities this

year have not been paid based on January 2021

5. The disability access fund (DAF);

census data but in 2021–2022 will be paid based

6. Maintained nursery school (MNS) on actual attendance (DfE, 2021a).

supplementary funding.

As to provision for babies and infants under two,

The average hourly rate for three- and four- there is no free entitlement for this age group

year-olds across the Local Authorities is £4.99 (EURYDICE, 2020a). In addition to the universal

(EFSA, 2020a), up two pence from 2020–2021 and extended entitlements there is targeted

(EFSA, 2019a). The average rate however does childcare support through the benefit system

not recognise the variation between inner city (Universal Credit) and/or tax-free childcare.

London rates (Camden, £8.51) and, for instance,

Yorkshire (York, £4.44). Due to Covid-19 Local According to Stewart and Reader (2020), the

Authorities have not been paid based on more recent focus on investing additionally in

January 2021 census data, but for 2021–2022 affordable childcare for working parents can

will be paid based on actual attendance, with be seen to have contributed to the gradual

supplementary funding for maintained nursery shift away from supporting child development

schools (DfE, 2021a). through investing in high quality early education.

In the Nutbrown Review (2012) it was identified

Stewart and Reader (2020) highlight that the that quality of provision requires staff with

EYNFF risks undermining quality as it threatens higher qualifications than are currently required.

the viability of nursery schools, thought to offer A review by Mathers and colleagues (2014) for

the highest quality as they are led by qualified the Sutton Trustexplored international evidence

teachers, because they are now, with the on the dimensions of quality which support the

EYNFF, funded at a much lower rate. The fact learning and development of children from birth

that there is also regulatory requirement to pass to three years old also suggested that Level 3 (A

through a set amount of the DfE funding to level equivalent) should be the minimum require-

providers poses an additional challenge for local ment that should be considered, especially

authorities to support professional development when working with two-year-old children from

and quality improvement. challenging circumstances. The lack of highly

qualified staff in early years settings continues

A two-year-old child meeting eligibility criteria to be the case and workforce supply challenges

is entitled to 570 hours of free provision per have increased (Pascal et al., 2020a).

year, typically taken as 15 hours per week over

a minimum of 38 and a maximum of 52 weeks Over recent years, school-readiness has also

of the year (DfE, 2018). As mentioned above, become a more prominent consideration with a

the DfE provides Local Authorities with the growing shift away from a play-based curriculum

funding for the free 15 hours entitlement for towards more formal learning through a focus

disadvantaged two-year-olds; however, there on literacy and numeracy as key aspects of

are no regulatory requirements to pass through school readiness, according to Stewart and

a set amount of the DfE funding nor is there a Reader (2020). This shift in focus, together

compulsory supplement or a special educational with the introduction of the Reception Baseline

needs inclusion fund (ESFA, 2020b). Assessment (STA, 2020) and the Phonics

Screening Check (STA, 2019) in Year One, puts

For 2021–2022, the average hourly rate for two- into question what we mean by ‘quality’ in early

year-olds across the Local Authorities in England childhood education. According to Stewart and

is £5.62 (EFSA, 2020a). This is down from £5.82 Reader (2020: 20) recent policy commitments

in 2020–2021 (EFSA, 2019a). As mentioned have been framed “mainly as improving childcare

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 2 25for working parents, with very little attention to early education for children and childcare for

early childhood as a life stage in its own right”. working parents. In Wales there is an entitle-

ment to universal part-time early education for

three- and four-year-olds, and targeted early

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland education hours for less advantaged children

from the age of two. (For further details see

Reflecting on early childhood education and Appendix 3).

care policy in Scotland, Wales and Northern

Ireland alongside England, we can see that all

four nations in the UK have a level of universal Summary

funded entitlement for three- and four-year-

old children, motivated mainly by supporting In summary, all children in England are entitled to

children’s development and learning. The part-time (15 hours) of early education from the

amount of hours offered is part time, between age of three, and for less advantaged children

10–15 hours a week, other than in Scotland, from the age of two, and additionally, children

which has recently extended its universal offer from working households are entitled to a further

to 30 hours a week term-time from summer 15 hours of childcare (ie 30 hours total) from

2021. In each nation there are very different the age of three and other subsidies before

approaches to supporting parents into work, this. It is evident that rather than ensuring an

study or training and more varied levels and extension of universal access to high quality

types of support for this, with Northern Ireland early education, the policy focus since 2017 has

offering the least support for childcare, concen- been on affordability of childcare and reforming

trating its focus on offering early education prior the benefit system to encourage employment.

to compulsory school entry, and England the Of significance is that with this policy focus,

most support for working families. In Scotland government support in England has shifted away

there appears to be a more holistic, integrated from targeting low-income families towards

approach in ECEC policy which foregrounds targeting support at working families.

quite generous initiatives which blend both

It is worth noting that the new Biden adminis-

tration in the United States has introduced in

2021 a transformative strategy for early years

embedded within the American Jobs Plan

and the American Families Plan (The White

House, 2021). The American families plan aims

to provide universal, high quality preschool to

all three- and four-year-olds. It is stated that

pre-school and childcare providers will receive

funding to cover the true cost of quality early

childhood care and education, including a

developmentally appropriate curriculum, small

class sizes, and culturally and linguistically

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 2 26responsive environments that are inclusive of programs and Head Start will earn at least $15

children with disabilities. The plan also aims to per hour, and those with comparable qualifica-

provide more affordable childcare by ensuring tions will receive compensation commensurate

that low- and middle-income families spend with that of kindergarten teachers.

no more than seven percent of their income on

childcare, and that the childcare they access It is also noteworthy to consider the pattern

is of high-quality. The plans will also invest in of free entitlements available internationally as

the childcare and early education workforce by shown in Figure 1 below. This data reveals that

providing scholarships for those who wish to most of the listed OECD countries offer a level

earn a bachelor’s degree or another credential of free entitlement that begins at a younger age

to become an early childhood educator. And, in most cases, and is generally unconditional or

educators will receive workplace based coach- universal from two to three years of age. The

ing, professional development, and wages that universal hours offered from two to three years

reflect the importance of their work. The inten- vary from 15–60 hours with most in the range

tion is that all employees participating in pre-K of 20–25 hours.

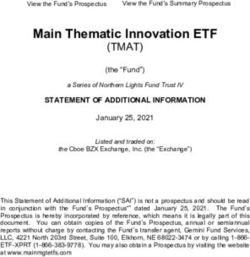

Figure 1: International Comparison of Free Entitlements

Hours/week the Hours/week the

Age of Entitlement to child has access Age of Entitlement to child has access

Country child Free Access to free childcare Country child Free Access to free childcare

Austria 5 Universal 16–20 Korea 0–5 Unconditional 30–60

3–5 Unconditional 20–25

Belgium 2.5–5 Unconditional 23.3

(Flemish) Luxembourg 0–3 Conditional 3

3–5 Unconditional ≤26

Belgium 0–2.5 Targeted N/A

(French) 2.5–5 Universal 28 Mexico 0–2 Targeted N/A

3–5 Unconditional 15–20

Chile 0–2 Conditional 55

4–5 Unconditional 22 Netherlands 0–4 Targeted 10

Czech Republic 5 Unconditional ≥40 New Zealand 3–5 Unconditional 20

Finland 0–6 Conditional 50 Norway 1–5 Conditional 20

France 0–2 Conditional 40 Portugal 0–2 Conditional N/A

2.5–5 Unconditional 24 3–4 Unconditional 25

5 Unconditional 25

Ireland 0–5 Conditional 15–60

3–5 Unconditional 15

Slovakia 3–6 Unconditional N/A

Italy 3–5 Unconditional 40

Slovenia 1–5 Conditional 45

Japan 0–2 Conditional 55

3–5 Conditional 20/50

Sweden 1–2 None N/A

3–6 Unconditional 15

Kazakhstan 1–6 Unconditional 50–60

Source: Data extracted from OECD Starting Strong 2017, Table 2.2 Characteristics of legal access entitlement (p80)

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 2 27Key Points: UK Policy

• In England, there is an entitlement to 15 to 30 hours and also offering childcare

universal part-time early education for tax advantages and additional benefits,

three- and four-year-olds, and targeted for those in employment.

early education hours for less advantaged

• The introduction of the 30 hour entitlement

children from the age of two.

has created a system in which the very

• Since 2017 there can be seen to be a poorest children are given greater access

policy shift in England to focus more on to funded early education and care at the

supporting working families, rather than age of two, but where many of these same

families living in poverty or disadvantage, children are then given access to fewer

through extending the hours of funded funded hours than better-off children at

places for three and four year olds from the ages of three to four.

3

Review of Research on the 30 hours Entitlement Policy

In this section research evidence on the take-up, 3. What impact has the COVID pandemic had on

quality and impact on children’s development the development of pre-school age children,

and school readiness of the 30 hour extended with a particular emphasis on socio-economic

entitlement policy will be presented, along with gaps?;

evidence about the positionality of this policy

4. How many hours are enough? Does it need to

against other current ECEC policies, such as

be 30, and in what pattern of delivery?

the two year old funded entitlement. It will also

include evidence addressing the following four

specified review questions:

Competing Goals

1. What is the nature of gaps in education

West (2020) provides an historic account

development and school readiness, and what

and analysis of legislative provision of early

impact has the current 30 hours policy had

childhood education over the twentieth century,

on these?;

starting with the 1918 Education Act and up

2. How has the prevailing government view to the 2017 free entitlements, detailing the

of early years provision as childcare rather shift in policies and provision from providing

than early education impacted on the quality nursery education specifically for poor children

of provision, for example through lack and disadvantaged families to universal early

of funding?; childhood education for all three- and four-

year-old children. It should be noted that whilst

Government funds early education, they share

provision of this service with private, voluntary

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 3 28and independent providers that have been (2020: 244) point out that although the EU has

vital in “’filling the gap’ in preschool provision” been advocating an integrated system for over

(ibid.: 582). two decades, few countries have fully integrated

ECEC systems “widely seen as important in

Cohen and Korintus (2017) look at the ECEC developing quality across services and ensuring

situation in Europe from the 1970s and it is that services meet the needs of children, fami-

interesting to note that the driver behind ini- lies and society”.

tiatives and the expansion of ECEC provision

was very much for enabling mothers to work as West and Noden (2019: 153) recognise that

opposed to providing for disadvantaged children when Labour came to power in the UK in 1997,

as was the case in England, as mentioned above. they inherited a mixed market economy of

Cohen and Korintus (2017: 238–239) recog- providers and that it was retained for pragmatic

nise, referring to work done by the European reasons; “the PVI infrastructure was already in

Commission Childcare Network (ECCEN) in the place so facilitating a rapid expansion of places”.

1980s, that many EU countries are “prisoners They were in a sense ‘prisoners’ of previous

of their historic roots, with one set of ‘childcare’ policies when they introduced the entitlement

services often developed as a welfare measure to free early education as part of their National

for working-class children needing care whilst Childcare Strategy and Sure Start local pro-

their parents worked, and another set of ‘early grammes. The aim was to offer choice and

education’ services developed as kindergartens flexibility for balancing work and family life (DfES,

or nursery education or play groups prior to 2004) but the mixed market economy came with

formal schooling”, what was referred to above as inherent problems as discussed by Chen and

a split system (DEPP, 2020). Cohen and Korintus Bradbury (2020) below.

Key Points: Policy Focus

• Early childhood education and care • In England, funded (maintained) provision

(ECEC) expansion as a policy priority began predominantly as educational

can be seen across Europe and elsewhere support for less advantaged children,

over recent decades with mixed goals; in with the PVI sector developing to fulfil

some countries it is primarily viewed as the need for childcare for working parents.

providing childcare for working parents, These twin goals continue to challenge

for others it is seen as a means to support the efficacy and quality of the multi-sector

less advantaged children educationally, delivery which continues in England.

for others it is a mix or blend of both of

• The educational value of ECEC is increas-

these goals.

ingly recognised in most European coun-

tries, even those who continue to have

a split system.

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 3 29ECEC Take-up • 88% of 3- and 4-year-olds taking up the

universal 15 hours, down from 93%;

Stewart and Reader (2020) note that take-up

• A 5% fall in take-up of the 30 hours enti-

rates of the free entitlement for two year olds

tlement, estimated at around 3 in 4 of

peaked in 2018 and has declined slightly from

eligible children;

72 per cent to 69 per cent in January 2020 and

that that take-up rates of the universal offer • The number of children in receipt of Early

for three and four year olds has also declined Years Pupil Premium has risen by 6%;

slightly, from 93 to 91 per cent for three year

• Take-up of the 30 hours is lower for children

olds and 98 to 94 per cent for four year olds.

with SEND than the universal entitlement

There is also evidence that take-up by children

(2.8% compared to 6.3%);

with special needs or disability has been particu-

larly affected by the COVID pandemic (Disabled • The number of providers delivering the two-

Children Partnership, 2020). One explanation put year-old offer has fallen, although the number

forward by the Disabled Children’s Partnership of maintained nursery and primary schools

is that the 30 hours offer may have pushed delivering the offer has increased;

some children out of ECEC altogether but they

• The proportion of staff delivering funded

do not elaborate on why this would be the

entitlements with a graduate level qualifica-

case. They do however point out that despite

tion remained at 9%. 36% of PVIs (including

a steady increase in take-up of funded places

childminders), delivering 51% of children’s

by two-year-olds in the maintained sector, that

funded entitlements, contain at least one

of three- and four-year olds has declined, and

graduate member of staff.

overall, data from the National Pupil Database

shows maintained nursery provision is down by

Chen and Bradbury (2020: 297) highlight the

5 per cent. This decline is attributed to children

dysfunction and inequalities of the English

who will later claim Free School Meals (FSM),

childcare market, when they state that “parental

indicating that those in poverty are less likely to

choosing behaviours do not conform to the

take up their entitlement. As Chen and Bradbury

market logic of competition and choice”. They

(2020) point out, despite maintained settings

further (2020: 287) point out that contrary to

offering higher quality provision, parental choice

findings by Grogan (2012), working middle-class

seems to be guided by practical considerations

parents in England can feel they are at a disad-

such as the age of the child, opening hours and

vantage as they are “tightly constrained to day

availability; this may result in nursery closures.

nurseries and childminders because of extended

According to Stewart and Reader’s (2020) data

service age and the opening hours they provide”.

about 63 per cent of three- and four-year-old

In other words, practical considerations such as

children not on FSM and 45 percent of children

the age of the child, term time opening hours

on FSM attended PVI settings in 2017.

and availability limit their choice of provision

and level of take-up and are often a priority over

Figures released from the DfE in July 2021

education quality and staff qualifications. The

(DfE, 2021) and analysed by Early Education

parents in Chen and Bradbury’s study tended to

(Early Education, 2021) reveal the significant

judge quality emotionally and subjectively on the

impact of Covid-19 on take-up with:

general feeling they had of a setting, rather than

taking Ofsted ratings, staff qualifications and

• 62% of vulnerable two-year-olds taking up

education quality as drivers. Chen and Bradbury

their entitlements, down from 69% the previ-

suggest childcare choice and take-up is, as such,

ous year, and the number of two-year-olds of

an emotive issue rather than a rational choice

Asian origin has fallen by a third;

and high-quality nursery schools have not acted

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 3 30as a market incentive to motivate quality in a system where the childcare market is not

improvement as was expected. This problem, only split between full-time working parents and

according to the authors, is not limited to the part-time working or stay at home parents, but

English context but is prevalent in marketised also has a split provision for children under three

approaches to childcare in Anglophone coun- and children three to five, as the English system

tries in general. has. Chen and Bradbury (2012: 297) conclude

that there is in effect “little real choice for

Albakri and colleagues (2018) also discuss parents, whose choosing processes are limited

the take-up rate for the free entitlement and by practical concerns, including those inherent in

group them under provider-related factors such the ‘free hours’ policy”. Practical considerations

as sufficiency, cost/funding and flexibility of include its location, reputation, affordability

provision and parent-related factors such as and opening hours in relation to their employ-

personal preference, awareness of entitlements ment needs. Degotardi and colleagues (2018)

and eligibility. They state parent-related factors remind us that parents should not be treated

are influenced by disadvantage, English as an as a homogenous group but their research on

additional language (EAL), ethnicity, popula- factors influencing choice of setting in Australia

tion mobility, special educational needs and showed that working parents needing what they

disabilities (SEND) and employment status. call ‘long day care’ were also mainly guided by

Albakri and colleagues (2018: 9) identified great pragmatic factors. Degotardi and colleagues

variation by region with take-up lower in London conclude providers and policy-makers should

than other regions; however, across all areas still be guided by children’s right to high-quality

“children from the most disadvantaged families, early childhood experiences.

who stand to gain the most, are less likely to

access the funded entitlements”. They suggest In the US, Bassok and colleagues (2017) noted

that with greater flexibility of provision, support that there was little difference in preferences

for parents new to an area and those of children across pre-school types in Louisiana but dif-

with EAL and SEND together with a better ferences in search processes between parents

understanding of the benefits of early education, looking for a place in publicly funded pre-

parents would be more likely to take up funded schools, state funded pre-schools or subsidised

entitlements. Albakri and colleagues do however private settings, that varied between relying

point out that some parents will still prefer on personal networks, local public schools or

for their child to start formal early education using advertisements and the internet. Bassok

when their child is older thus limiting take-up and colleagues therefore recommend, taking

rates achievable. parental needs and experiences in the choosing

process into consideration, that policy makers

According to the Starting Well report (EIU, need to address two points in particular: firstly,

2012) the UK was rated as offering one of know better if and what information parents

the best pre-school programmes globally by have access to in making choices, and sec-

ranking 4th out of 45 countries rated. The ondly, improve eligibility to and affordability

Starting Well Index assessed social context, of provision.

availability, affordability and quality along 21

indicators. The report stated that the UK was, Newman and Owen (2021) examined factors

in 2012, ahead of many countries by offering preventing eligible families from taking advan-

the universal entitlement for three- and four-year tage of the two-year-old entitlement, especially

olds together with subsidies for disadvantaged barriers that parents with children with SEND

families. However, as the research by Chen face and possible solutions to these barriers.

and Bradbury revealed, league tables may They revealed three themes:

hide inequalities or lack of choice, especially

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 3 311. lack of awareness and understanding in any impact, understanding access is crucial.

regards to eligibility; There are many factors influencing access, one

of them, according to the research by Campbell

2. fear of stigmatisation; and

and colleagues, is the availability of different

3. concerns over the ability of staff to deal types of settings. In England the free entitlement

with a child’s additional needs. can be accessed in:

Lack of awareness is again an aspect as in the • maintained nursery schools and primary

study by Bassok and colleagues (2017). Newman school nursery classes, collectively as ‘main-

and Owen (2021) suggest that if providers want tained provision’;

to overcome identified barriers they need to:

• day nurseries run by the private, local author-

ity or voluntary sector, some of them within

1. Restructure how they approach the families

Sure Start children’s centres;

by being more aware of the unequal power

relation between them which may involve • childminders; and

using parent ‘ambassadors’ to share their

• sessional, part-day providers.

experiences of the free entitlement.

2. Address the ‘othering’ of families who take The availability of these different types of provid-

up the two-year-old entitlement, that maybe ers varies widely across England but noteworthy

only true universal access, irrespective of dis/ is that most new places created since 1997 were

advantage, can solve. in private and voluntary settings (Blanden et al.,

2016). This is an important point as there are

3. Build trust that the system can cater

“tendencies among some families to attend some

to specific needs.

types of settings” depending on opening hours,

fees or simply by preference for one type of

The evidence indicates that policy needs to

provision over another (Campbell et al., 2016).

be more explicit about its intentions; Is it to

support child development and learning? Is it

In their study, Campbell and colleagues looked

about helping parents into work? Or both of

at the extent of take-up of the free entitle-

these aims? It is argued that a lack of coherence

ment for three- and four-year-olds using data

in policy intentions over time has led to a lack

on 205,865 children from the National Pupil

of impact and outcomes from the investments

Database (the Early Years Census and the Spring

made (Moss, 2014, Brewer et al, 2014, Paull,

Schools Census datasets). The focus was on

2014). To overcome barriers a strength-based

children accessing the full five terms they were

approach rather than a deficit approach is

eligible for before compulsory education. They

needed, according to Newman and Owen,

looked into three pupil characteristics:

where the onus is on the service provider in

making services accessible. This means promot-

1. children eligible for free school meals (FSM);

ing benefits of accessing provision for children

and families rather than a remediating approach 2. children with English as an additional

to counter disadvantage. language (EAL);

3. local factors such as nature of

Campbell and colleagues (2018) recognise the

provision available.

dual purpose of investing in ECEC; to support

maternal employment and child development

The results showed that almost one in five

through early intervention in the lives of dis-

children did not take up their full entitlement of

advantaged children in particular. However,

five terms before starting compulsory education

they point out that for interventions to have

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 3 32with a clear income gradient of non-attendance. “unequal duration of attendance between groups

Only 15.7 percent of children ‘never on FSM’ did in the terms preceding the immediately pre-

not attend on the study’s cut-off date compared school year. Non-attendance at the beginning

to 27.4 percent of children on FSM. Among most of their funded entitlement may be diluting

ethnic groups’ figures showed a similar pattern the potential effects of the policy on low-

of children more likely to have accessed the full income children.”

entitlement if they had never been on FSM. There

was a however a stronger effect on low income in Quantity together with staff qualifications may as

English-only than EAL households (Campbell et such be important factors. Blanden and colleagues

al., 2018: 526). FSM status, EAL and ethnic back- recommend higher quality requirements, particularly

ground are as such important factors influencing in relation to staff qualifications, are needed for

take-up. “Having English as an additional lan- private nurseries serving poorer children in England

guage, or being English-speaking and persistently if the free entitlement is to have greater effect. If

poor, are both predictors of non-attendance” this does not happen, Blanden and colleagues, as

(Campbell et al., 2018: 526). Campbell and colleagues (2018: 537), fear the free

entitlement to 30 hours for children of working

As to local factors such as provision available, parents will further disadvantage children from

“over-all, the picture suggests the value of a mix low-income families by “increasing the extent to

of different types of provision in promoting take- which subsidies for early education are concen-

up, and particularly the importance of having trated disproportionately on children who least

even a small share in the voluntary sector and need a head start”. In the policy review by Akhal

in Sure Start children’s centres” (535). and colleagues (2019), they recognise there is a

wide variation across local authorities in the take-up

The above points are important for understand- of two-year-old places where in some authorities

ing take-up; however, Blanden and colleagues there had been a slowing down of the take-up of

(2016: 718) found when comparing child out- the two-year-old entitlement, possibly due to the

comes of children taking up the free entitlement difference in delivery costs and the prioritisation of

for three- and four-year-olds (at the age of five, the three- and four-year-old entitlements.

seven and eleven) that “disadvantaged children

do not benefit substantively more from the free A study conducted in Scotland on the take-up of

entitlement than their more affluent peers”. They places for eligible two-year-olds revealed that:

suggest it may be because all new places created

under the policy were in the private sector which “the major barrier to uptake is lack of aware-

is less regulated with lower levels of graduate ness – rather than opposition to the concept,

staff. Blanden and colleagues (ibid.) state: problems with the application process or

dissatisfaction with the nature of the provision”

“There is evidence that private nurseries (Scottish Government, 2017: 4).

which serve poorer children are particularly

bad on these measures [employing graduate The study also noted that the offer was promoted

teachers], helping to explain why the policy through professionals (mainly health visitors),

did not have the expected success in reduc- advertising and word of mouth, and of the three,

ing gaps in cognitive development between the importance of contact between the profession-

children from different backgrounds.” als and eligible families was the most important

means. All the above findings have important policy

Campbell and colleagues (2018: 536) suggest implications in that extending universal provision

another explanation may lie in the fact that is important in creating a more equitable start for

there is: children of low-income families.

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 3 33Key Points: ECEC Take-up in England

• Take-up rates of the free entitlement for • Research suggests that with greater flexi-

two-year-olds and the universal offer for bility of provision, support for parents new

three and four year olds in all sectors to an area and those of children with EAL

has declined significantly over the last and SEND together with a better under-

year due to Covid-19. There is signifi- standing of the benefits of early education,

cant variation in take-up by region and parents would be more likely to take up

socio-economic status. Take-up rates for funded entitlements. Some parents will

children with special needs and disability still prefer for their child to start formal

have been particularly affected by the early education when their child is older

COVID pandemic. thus limiting take-up rates achievable.

• Childcare choice and take-up is influenced • For parents with children with SEND there

by both provider-related factors such as are additional barriers to take-up, includ-

sufficiency, cost/funding and flexibility ing lack of awareness and understanding

of provision and parent-related factors with regard to eligibility; fear of stigma-

such as personal preference, awareness tisation; and concerns over the ability of

of entitlements and eligibility. The issue of staff to deal with a child’s additional needs.

quality does not appear to be a factor in

• There is some evidence that lack of

parent choice and take-up, meaning the

impact on child outcomes, particularly for

market is not driving sector improvement

disadvantaged children, may be due to

or enhanced access.

lower hours of access and lower qualifi-

• Parent-related factors are influenced cations of staff in settings serving these

by disadvantage, English as an communities. It is suggested that action

additional language (EAL), ethnicity, on enhancing staff qualifications across

population mobility, special educational the sector is needed if free entitlements

needs and disabilities (SEND) and are not to further disadvantage the

employment status. less advantaged.

ECEC Quality initiatives, overall qualification levels in the ECEC

workforce are declining (Pascal at el 2020).

Campbell and colleagues (2018) point out Stewart and Reader (2020) also note there has

that following the roll-out of funded places, been a general decline in children attending

the introduction of the statutory early years voluntary pre-schools and an increase in children

foundation stage (EYFS) (from birth to five) and attending private day nurseries, where qualifi-

the development of the ECEC workforce are cation levels are comparatively low but as this

examples of how successive governments have trend started long before the free entitlements

tried to improve the quality of provision in all in 2017, see Figure 2, this cannot be attributed to

sectors. However, despite successive workforce the policy from 2017.

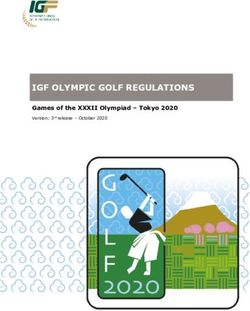

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 3 34Figure 2: Three and four year olds in PVI sector by FSM status

Three- and four-year-olds who go on to receive free school meals

(excluding those in Reception class)

35%

attending funded early education

% of three- and four-year-olds

30%

(excluding Reception class)

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

All other three- and four-year-olds (excluding Reception)

35%

attending funded early education

% of three- and four-year-olds

30%

(excluding Reception class)

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Private day nursery Private pre-school Voluntary pre-school

Other including childminder Voluntary day nursery

Sure Start (main or linked)

Source: Stewart and Reader (2020: 58) interpretation of the National Pupil Database

Of concern is the fact that, “the falling share of a mixed economy of providers has come at the

children eligible for free school meals attending expense of staff quality, a prerequisite for long-

maintained settings means a substantial drop in term benefits for children”.

the share of children from low-income house-

holds with access to a QTS [qualified teacher]” Child development as identified through the

(Stewart and Reader, 2020: 60). This is impor- EYFSP data can be used to measure cogni-

tant as level of staff qualification is an important tive and social development and in how the

indicator of quality. The EPPE study showed attainment gap is narrowing or widening by

that provision needs to be high quality to ensure comparing children on FSM and children who

it promotes children’s development (Sammons, are not. Evidence reveals that the gap in the

2010; Sylva, 2010; Mathers et al., 2014). West EYFSP scores had been closing up to 2017 but

and Noden (2019: 163) believe “the government has since started to widen again (Hutchinson

focus on increasing the availability of places via et al, 2019; Stewart and Reader,2020). The gap

A Fair Start? > What do we know about the 30 hour entitlement > Section 3 35You can also read