Violent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White: Expanding Meaning Potential through Media

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Violent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

S. Rebecca Leigh

Violent Red, Ogre Green,

and Delicious White: Expanding

Meaning Potential through Media

Daily access to drawing/writing media becomes a pathway for expanding meaning

potential on the page.

D

oes anyone have violent red?” andanotherandanother. Hail the dollar-store

I was walking around the room with marker; it offers more than you might think.

second-grade teacher Regi Matheny In this article, I focus on how daily access to

when those words, violent red, filled our class- a variety of media (e.g., marker, crayon, pen-

room and changed it forever. Up to that point, cil, color pencil, pen, pastel, and paint) influ-

no one had openly requested so specific a color enced how children constructed meaning through

beyond the more common dark blue, light pink. drawing and writing. The power of media was an

This simple request halted the busyness of the unexpected finding in a yearlong study on what

room. Impressed into silence, peers close by happens when art and language are encouraged

watched as Marcus fingered his tool bin in search ways of knowing in a second-grade classroom—a

of a tool that would produce a specific kind of finding too significant not to share with teachers,

red for his storm drawing. Peers offered Marcus many of whom are caught up in a pencil-centered

what must have seemed to him close-seconds in mindset.

the red department, but in a lemons-to-lemonade

moment, he figured out that he had to create vio- MEDIUM AS MESSAGE

lent red from the tools he had.

Traditional K–12 classrooms are notorious for

For Marcus, naming red violent adroitly illu- privileging pencil over other writing tools, espe-

minated experience as meaningful (Dewey, 1934). cially in the elementary grades. Unlike ink, graph-

In response to picturebook read-alouds on hurri- ite offers young writers the opportunity to start

canes and tornadoes, Marcus needed a kind of red over, to erase. For many teachers, erasing is

that would communicate movement, agitation, important; incorrect answers to problems and mis-

unrest (Olshansky, 2008). Violent red got Mar- spelled words can be replaced with correct ones. I

cus’s peers thinking widely and deeply about color believe a pencil-centered mindset develops when

as medium for their message. Paired words or we push overmuch for correctness. Instead, we

March 2010

“color searches” (D. Sabiston, personal communi- should be pushing for a process-oriented mind-

cation, March 26, 2008) like ogre green and deli- set where daily access to drawing/writing media

cious white quickly gained currency in classroom makes it possible to respect process, to value

experiences, for they were valuable “silver dollar

Vol. 87 ● No. 4 ●

experience.

words” (Olshansky, 2008, p. 78); in fact, the chil-

dren recorded them regularly in class on a 6-foot- Experiences with media offered children a

long bar graph to which everyone had access. variety of ways to construct meaning. McLuhan

(1967) argued, “The extension of any one sense

As the weeks progressed, paired words or alters the way we think and act—the way we per-

“color searches” poured in like water from a bro- ceive the world” (p. 41). He noted, for example,

ken levee: “Does anyone have ogre green?” And

Language Arts ●

the wheel is an extension of the foot; the book is

another: “Can I use your delicious white? I need it an extension of the eye, etc. In this study, tools

for the kind of response I’m doing.” And another: were extensions of children’s own wonderings,

“If you show me how to make cat black, I’ll show curiosities, and questions. Tools became moor-

you how to make my yellow Brazil.” Andanother- ings of their thoughts. Children picked tools to

252

Copyright © 2010 by the National Council of Teachers of English. All rights reserved.

LA_March2010.indd 252 2/2/10 10:34:37 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

confirm and extend their knowing. Media altered so that I could observe her invitations to learning.

the way they thought (i.e., how they responded To better understand art as a way of knowing, we

on the page) and the way they acted (i.e., posture toured two schools in Hilton Head Island, South

while they worked). Media also allowed children Carolina, that supported a multimodal approach

to have direct experience with their wonderings, to learning. One feature we noticed on those tours

curiosities, and questions. It is through direct was children’s access to different media. At the

experience, Greene (1995) argues, that children end of my observations in April 2006, I shared my

can discover and release their imagination. vision for a study with Regi and a tentative plan

Eisner (1998) took McLuhan’s notion of media- for how we could begin to work collaboratively.

as-extension a step further. He claimed, “What we She embraced the invitation to collaborate with

come to know about the world is influenced by the me in this research study.

tools we have available” (p. 28). Children who are I began working in Regi’s classroom during

given rulers will likely measure their world, but the 2006–2007 school year. Children’s diverse

if a ruler is their only tool, their knowing is lim- ways with media nudged us to tackle our assump-

ited. In other words, tools influence what children tions about tool use together. We questioned our-

think about (Eisner, 2002). For Marcus, access to selves and each other with the intent to expose

a range of red allowed him to think deeply about and examine our assumptions. Interrogating our

color. The outcome is pulsating; beliefs about tool use forced

a violent red storm tells us what We did not want to judge what us to pay attention to the tools

Marcus knows about hurricanes was or was not a drawing or we used in our invitations to

and tornadoes. Even more pul- writing tool. “Come to the learn (e.g., providing written

sating is the knowledge that carpet,” we would say, “and bring feedback in a variety of writ-

Marcus was poised to make something to write with.” ing tools, not just pen or pen-

that kind of connection between cil) as well as our language

color and science because he was immersed in a choice in those invitations (Johnston, 2004), such

learning community that valued having a relation- as explaining why we might use one tool over

ship with media. another. It was important to us that our demon-

Teacher-researchers who have investigated strations communicate to children what we value:

children’s intentions with color (Albers, 2007; you can write in marker and live to tell about it.

Hubbard, 1989) have contributed to our under- Regi and I agreed that in order to under-

standing of media; however, their work invites stand their ways with art and language, we would

further inquiry. We must explore the impact of need to provide students daily access to tools.

the tool itself in meaning construction. This study Announcing to children when they can take out

extends the small body of literature on the power their markers to draw, a common school practice,

of media by looking more broadly at the meaning seemed to us contrived and controlling, putting

potential of everyday writing and drawing tools. emphasis on us rather than on them. We did not

In addition, this study invites teachers to con- want to judge what was or was not a drawing or

sider what their basic assumptions about tool use writing tool. “Come to the carpet,” we would say,

are. Without question, there exists an unaddressed “and bring something to write with.” Thus, stu-

assumption that markers and crayons are child- dents had a relationship with media because we

like, certainly not writing tools for the serious. rarely interfered with it.

What do I mean? Look inside classrooms. Where Students were responsible for their individ-

have all the markers gone? In this article, I argue ual tool bins. Being responsible meant using time

for daily access to writing/drawing media in class- during morning routine to sharpen and replenish

rooms—marker, crayon, pencil, color pencil, pen, tools needed for the day. On a meager budget, I

pastel, and paint—to help students go wider and was still able to add to classroom materials twice

deeper in their meaning construction. a month. We housed these materials in a plastic,

three-drawer unit from which students made their

CONTEXT OF THE STUDY morning selections. At this plastic chest of draw-

My work with Regi started in the fall of 2005, ers, students often negotiated with peers for spe-

when I met with her once a week for eight months cific kinds of tools (e.g., fat and skinny markers,

253

LA_March2010.indd 253 2/2/10 10:34:37 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

an iridescent crayon, a peculiar shade of green 1978). In this study, talk was integral to self-

pencil, a highly prized silver gel pen, etc.). expression through media. As well, this mean-

In this qualitative study where art and language ingful tool use initiated meaningful conversation

had equal import, children responded three times about responding through writing.

a week in their response journals (e.g., lined and Vygotsky (1978) argued that it is through the

unlined) to a variety of engagements (e.g., math, mediation of others that knowledge is socially

science, ELA, and social studies) through draw- constructed. With the support of peers, chil-

ing and writing in four different contexts (e.g., dren thought of new and different ways of using

table, group, guided, and independent share). media and showing their knowing through

While some students were able complex symbols. Chil-

to start and finish a response in In this learning environment, talk dren assumed social roles;

a short amount of time, many was essential in nurturing their for instance, as artists, they

used it to further explore per- wonderment. acquired symbolic knowledge

sonal reactions to ideas pre- of color and line; as writers,

sented in books, experiment with mathematical they acquired symbolic knowledge of letters and

ways of looking at the world as new concepts were sounds. The acquisition of both linguistic and

learned, consider weighty issues like global warm- social knowledge were interrelated; the interre-

ing, etc. On the page, students wondered and wan- lationship supported the development of children

dered through ink and graphite, oil pastel and paint as symbol weavers working on and develop-

to unearth some of their deepest curiosities. ing their ways with artistic and written forms.

In this learning environment, talk was essential Talk plays such a vital role in learning develop-

in nurturing their wonderment. It was encouraged ment that it led Vygotsky (1978) to believe “chil-

as a necessary avenue for personal growth. In dren solve practical tasks with the help of their

table share, children talked with each other while speech, as well as their eyes and hands” (p. 26).

they responded through writing and/or draw- In classrooms where children are encouraged to

ing; group share was an opportunity for children be social, children’s ideas can “take wing in the

to share their responses and ask questions about company of their peers” (Paley, 1999, p. 100).

each other’s work in a public forum; in guided Violent red, for example, took wing in Regi’s

share, Regi and I asked open-ended questions to class; it positioned others to think about and

initiate a conversation about a child’s response; develop their own color searches.

in independent share, children talked about their Dewey (1938) argued that learners actively

responses privately into a tape recorder behind a construct knowledge by transacting with the envi-

threefold cardboard screen. Each structure, which ronment. Transacting with media in a classroom

was audio taped, transcribed, coded, and ana- environment that supported tool use, children

lyzed, provided a lens for understanding how chil- were able to reflect on the unique meaning poten-

dren used media and how media influenced their tial of tools (e.g., “I think I’m going to use marker

meaning construction. Photographs of students because it’s lifelike”). Dewey considered reflec-

working with media and transcribed interview tion a core component of what he called an inter-

March 2010

data supported what was learned from these four actional perspective on learning, where learning

unique contexts. is an open, ongoing, and generative meaning-

making process. He believed that being reflective

Vol. 87 ● No. 4 ●

“SEEING” THE POWER OF MEDIA allows one to build and extend knowing. With-

out reflection, he argued, one cannot be moved

THROUGH THEORY

or changed. Tool choice allowed children to be

Talk is a way for children to be social, to build reflective in their decisions to use one tool or

knowledge through personal experiences (Dewey, color over another. A reflective stance made pos-

1938); it is an avenue for self-discovery and con- sible the opportunities to be moved and changed.

tributes to children’s understanding of the world

Language Arts ●

Being reflective also invited a transactive relation-

(Vygotsky, 1978). Talk is the tool of a democratic ship between child and tool.

classroom, the framework through which mean-

Eisner (2002) argued that symbolic represen-

ing is mediated, constructed, and shared. It is, per-

tation promotes intellectual development and

haps, our greatest tool (Luria, 1982; Vygotsky,

helps learners express meaning rather than merely

254

LA_March2010.indd 254 2/2/10 10:34:38 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

state it. He also argued that the arts invite learn- explained further, “is Stella . . . is me. I imagine

ers to look carefully and deliberately, to use their her hair on me.” Ti’ombe’s decision to paint Ruby

imagination and judgment to solve problems, Bridges “sandy brown” is an example of cultural

“to tolerate ambiguity, to explore what is uncer- and symbolic effects of color. Having watched

tain, to exercise judgment free from prescriptive a short video clip on Ruby Bridges and poured

rules and procedures” (p. 10). Tolerating ambi- over sepia-rich images of Bridges’s life in the text

guity and exploring uncertainty through the arts Through My Eyes (Bridges, 1999), Ti’ombe used

encourages children to express their ideas, feel- paint to create sandy brown hues, with which she

ings, and invent their own forms (Gardner, 1980, depicted both Ruby’s African American skin color

1983, 1993). Greene (1995) concurred with Gard- as well as her own. “Ruby and me, we’re like the

ner; access to the arts in education expands “the same,” remarked Ti’ombe as she mixed colors.

capacity to invent” (p. 5), to think beyond the Rebecca’s decision to add yellow to her blue sky

limiting parameters of right/wrong answers, and in her response titled Starry Morning (so that the

instead explore multiple ways of expressing sky “looks like it’s waking up”) is an example of

knowing through line, color, etc. Indeed, curric- the influence of light. Her comment, “it’s waking

ulum that encourages learners to think creatively up” suggested she was using color to reflect light,

encourages learners to access all their ways of adding “Well, Mr. Van something . . . I notice

knowing. he uses dark colors for sleeping, but I’m making

There are important lessons to be learned, par- mine waking with morning colors.” As Marcus

ticularly for the pencil-centered world of school, worked on his violent red for his storm, Daniel’s

when we support and encourage children to comment, “That looks like blood” is an example

transact with a variety of media in meaningful of color metaphor.

ways. In this study, children used tools to make In response to an engaging read-aloud of

meaning three ways: they used color meaning- Woodson’s (2001) The Other Side—a story about

fully, used tools intentionally, and used tools and two young girls, Clover and Annie, who try to

color to document feelings. Three children from befriend each other in a community where blacks

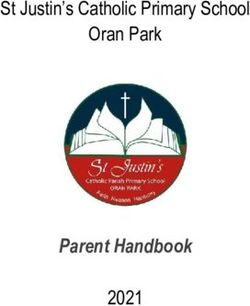

the study: Rebecca, a writer who discovers art as and whites feel divided—Rebecca demonstrates

a way of knowing; Marcus, an artist who slowly color as meaningful in her response titled Friedss

eases into writing; and Diamond, who discovers (see Figure 1). During and after the read-aloud,

writing as a way of knowing through her love of we discussed how the illustrator of this book,

art, share how they used media. Through stories E. B. Lewis, used color to captivate our senses,

so powerful, you are invited to consider again stir our emotions. Such discussions are important:

your basic assumptions about writing/drawing “Looking at artworks helps children learn how to

tools. tell stories as they relate their own experiences

to what they are seeing” (Mulcahey, 2009, p. 8).

CHILDREN USED COLOR MEANINGFULLY

Using color as a pathway, children were inten-

tional in their meaning making; however, their

reasons for using color varied significantly. To

understand the ways children used color in this

study, I leaned on the four categories Hubbard

(1989) discerned from her ethnographic research

with 6-year-olds: color for detail, cultural and

symbolic effects of color, the influence of light,

and color metaphor.

Captivated by illustrator Gay’s (1999) com-

mand of precise artistic detail in Stella’s fiery

tresses in Stella, Star of the Sea, Gabby’s com-

ment, “I’m calling her Red Wind because she

has reddish hair and it’s blowing,” is an exam- Figure 1. Rebecca’s response: Friedss; “Fr” is in red pastel

ple of using color for detail. “Red Wind,” she and then “iedss” are all written in blue pastel.

255

LA_March2010.indd 255 2/2/10 10:34:38 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

Like Lewis, Rebecca used color as a way of invit- able expressing his ideas through writing, color-

ing the audience in. She explained, “I want to ing helped ease Marcus into doing what writers

use colors that make you ask me questions.” In do; they slow down, take notice of details, rumi-

a guided share, questioning helped me to under- nate over ideas, experiment on the page. In an

stand that Friedss “is kinda like a code . . . the interview, Marcus helped me to understand that

blue pastel represents me and the red represents color searches also helped him to think about

Ronthea and we’re friends so that’s why I put us words. “The storm is violent, red and angry . . .

in the words.” it’s like fast . . . scary, maybe too scary.” So I ask,

By alternating red and blue pastel, Rebecca “Is it intense?” thinking intense is a word Mar-

helps us to understand the importance of hav- cus might be searching for. He smiles, like we are

ing access to color in writing. Drawing on the on to something in this conversation. “What does

theme of acceptance, she used color to person- that mean?” he asks. I smile back, using different

alize her response through a representation of tools to show what intensity looks and feels like. “I

friendship with Ronthea. Ronthea, like Clover, is like that word, Miss Rebecca, hey Miss Matheny! I

African American; Rebecca, like Annie, is Cau- learned a new word for writer’s workshop,” and he

casian. Rebecca used two different colors to code pulls out a marker, red of course, and writes intense

two different relationships, while at the same time in his journal, making a deeply grooved squiggle

demonstrating the impact the story had on her. beside it. In so doing, he adds to his word bank.

Friendship matters, not skin color. It is unlikely Diamond further demonstrates color as mean-

Rebecca would have created such a meaningful ingful in Nighty-Night (see Figure 2), a response

code had she access only to pencil. Friedss writ- to a social studies engagement on communities.

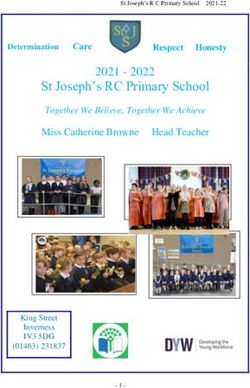

ten entirely in graphite could mean exactly that, In an independent share, she explained that using

friends, and perhaps nothing more. When asked bright colors allowed her to show “the build-

where she might take this idea further, Rebecca ings aren’t real.” By real, she meant her drawing

shared that she liked the idea of using color to “doesn’t look right.” She helped me to understand

show who is talking in a story, adding, “and like that she was deliberately using color to emphasize

two colors on top of each other could be code for

when they think the same.” Using color was not

a way to avoid grammar; Rebecca knew how to

use quotation marks in written narrative. Rather, it

was a way of deepening her understanding of lan-

guage as a creative and playful sign system.

Marcus’s story of using violent red to depict a

raging storm is an example of how he chose color

meaningfully. For him, color is information; it

“helps you like, figure it out.” In an interview, Mar-

cus explained that he saw a difference between

a color and a kind of color, “If it’s bright green,

March 2010

it’s just an apple, but if I draw like Charly’s ogre

green, then it’s not so good.” For Marcus, a kind of

color (i.e., ogre green) could explain a lot. Violent

Vol. 87 ● No. 4 ●

red explained intensity, and his collection of dif-

ferent reds helped him show his knowledge about

storms. In table share, where one can hear strokes

of marker on tape, he explained to one of his peers,

“storms are fast . . . they can surprise you . . . I like

using red cause you think it’s nice but when you

Language Arts ●

like, when you get close it can be something more.

That’s how storms work . . . they scare us.”

As daSilva (2001) explains, “[W]hen draw-

ing is part of literacy, it helps us know our subjects

and our thinking” (p. 3). For a learner uncomfort- Figure 2. Diamond’s response: Nighty-Night.

256

LA_March2010.indd 256 2/2/10 10:34:38 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

what was and was not real. “This is my apartment, system among many in which we can communi-

but it didn’t work out, so I colored it blue . . . I cate knowing. “Color gets me going,” adds Dia-

made these different colors so you would know mond, “it makes me want to write and I never

they don’t really look like that.” used to care about color.” Why the change? I ask.

Having a relationship with media allowed Dia- “Books. I get ideas from illustrators, like when we

mond to reflect, rethink, and revisit her response talk about ’em. They’re people in my head.”

that “did not work out.” Rather than turn to

another page when her response did not look CHILDREN USED TOOLS INTENTIONALLY

right, she turned to color as a pathway to con- Before responding through drawing, writing, or

struct meaning in a new way. Diamond’s use both drawing and writing, children were encour-

of symbolic representation demonstrates how aged to think about what they wanted to show in

she approaches ambiguity and constructs, in the their response (e.g., particular ideas, feelings, etc.)

absence of prescriptive rules, her own rules (Eis- and the kind of tool or tools that would best com-

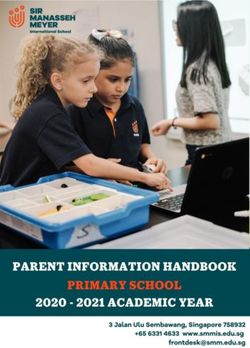

ner, 2002). municate those ideas and feelings. Children used

In the presence of image-rich picturebooks, what they knew about tools to make decisions

Diamond explained how humorous illustrations as they responded in their journals. Some chil-

such as Pinkwater’s (1993) The Big Orange Splot dren selectively used one or two tools, while oth-

or those Jared Lee drew for Thaler’s The Black ers used all of them. Figure 3 provides a glimpse

Lagoon series (2004–2009) compared to more of what the children valued in different tools so

serious and perhaps realistic uses of color, like that they could be intentional in their meaning

Brooks’s desert scenes in Wild’s (2006) Fox. She making. As this figure shows, pencils were valued

explained how illustration got her thinking about for erasing and shading; color pencils were val-

how she could use color in similar ways. “You ued for lightness, outlining, and writing; crayons

can use color to tell a story before the story, ya were valued for coloring in large spaces; markers

know?” Yeah, we know; language is but one sign were valued for emphasis, realism, writing, and

Tool Student Response Date

Pencil Rebecca: Pencil’s good for erasing. 9/13/06

Kendall: I can shade with this. 1/26/07

Rebecca: Pencil is light and good for shading. 1/26/07

Color Pencil Jakobe: Use this, it’s good for shading. 11/1/06

Kendall: Color pencil is good for outlining, you know. 2/2/07

Diamond: If I make a mistake, it’ll cover up. 10/20/06

Ronthea: I can write with this. 10/4/06

Crayon Thaddeus: Crayons let you draw in stuff. 10/9/06

Thaddeus: There’s a whole lot in the crayon. 10/30/06

Jacob: I can go fast with crayon. 9/13/06

Jakobe: I want to shade so I’m using crayon. 9/29/06

Marker Thaddeus: I used emphasis, I decided to make the numbers intense. 9/18/06

Gabby: Marker is lifelike. 1/8/07

Rebecca: Look at these autumn letters. I can write and draw at the same time. 11/6/06

Marcus: The grey fenced in the blue on my moon. I can get it close like that. 10/18/06

Pastel Diamond: You can scratch pastel. 1/8/07

Marcus: This is hard and soft. 12/6/06

Diamond: Pastel mixing looks dreamy. 1/29/07

Kamryn: I’m making special effects, watch. 12/4/06

Paint Alex: You can dust your page with paint. 1/19/07

Rebecca: If you go lightly it looks like salt. 2/9/07

Diamond: Mixing colors gives you a new one each time. 1/12/07

Marcus: Watch me cover the page with this. 10/4/06

Figure 3. The value of the tool

257

LA_March2010.indd 257 2/2/10 10:34:39 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

outlining; pastels were valued for creating inter- experiment, I can’t shut off my brain . . . like when

esting effects; paint was valued for mixing, blend- I write in pastel, I want to make words like Shake-

ing, and covering large areas. speare does . . . like in those poems Miss Matheny

In Rebecca’s Friedss response, she picked pas- showed us.” What kind of words? I ask. “The kind

tel intentionally. In a guided share, I asked the that make writing fun,” she replies. After this inter-

questions, “What worked well for you today? view, Rebecca made writing fun by writing the

Which part(s) do you feel confident about?” She words “I dare cry,” and “lay in deep sleep,” and “I

shared that she had “tried something different lay restless in wonder,” in a poem, written in pen-

with pastels.” She explained: cil, about her cat. We would be fools to ignore the

role pastel played in getting her pencil to move

Rebecca: You know how the girls in the book with such delicate attention toward language.

wanted to be friends but couldn’t? That made me

think of times when I wanted to be friends with In Marcus’s violent red response, he intention-

someone but couldn’t so I made it look like a ally chose marker to depict a raging storm. As he

dream. explained, “With marker, I can control how I want

the color to go. Like, with pastel and crayon you

RL: That’s interesting, why a dream? get more white spots when you rub like this (dem-

Rebecca: Because if it looks like a dream, onstrates on paper), so like the tornado would look

anything can happen. In a dream, they can be like a bad wind . . . . With marker, I covered up

friends no matter what. the white spots; that way it looked like a tornado,

Pastel allowed Rebecca to create dream-like effects you know, tight.” Rubbing crayon and pastel on a

through art, a contextual decision; the girls in piece of paper, he demonstrated the limitations of

Woodson’s (2001) story could not play together ini- these tools. Marker was necessary to represent lit-

tially, so she imagined a place tle wind or air in the tornado. I

When we wonder, we consider interpreted tight to mean speed,

for them through pastel. Think-

more than one answer, more and he used marker effectively

ing creatively, pastel allowed

than one way of looking at to show his understanding of

her to create a hypothetical con-

text. Thinking hypothetically is

a situation, a mathematical how storms move. But his use

important in learning; it makes problem, a scientifi c of marker is not just about mak-

room for what-if thinking, which experiment, a friendship. ing a better picture. More than

is necessary in all aspects of cur- this, it shows that he is thinking

riculum. When we wonder, we consider more than about the world in a fine-tuned way and, in talk-

one answer, more than one way of looking at a sit- ing about his response, he fills the room with his

uation, a mathematical problem, a scientific experi- own whirlwind of ideas. Consider, for example,

ment, a friendship. the verbal imagery that accompanies his markered

storm during a group share:

In the same conversation, I also learned that

using pastel made Rebecca think about cursive, Marcus: This is my response to, um, the read

“’Cause pastel lets you write like cursive, it’s alouds on hurricanes and tornadoes. Miss Ma-

theny? [Teacher is part of the discussion group]

March 2010

smooth and wavy.” Weeks earlier, Rebecca had

experimented with cursive using a mechanical RM: Was there something about those books

pencil. After several attempts that I had observed, that stuck out in your mind that made you want to

she tossed the tool away in frustration. On one respond to them?

Vol. 87 ● No. 4 ●

occasion, when Kamryn asked what the mat- Marcus: Yes, ’cause I know a lot about sci-

ter was, Rebecca explained, “It’s too hard. I can’t ence and like how storms can surprise, like right

make it work.” Yet it was the creamy texture of here (points to drawing) I made my storm look

pastel that reengaged her on the page so that she fast by going like this (motions quick hand move-

could experiment with cursive, a very cool, third- ments), so like first it’s friendly (pauses) maybe

grade thing to do. a small wind, kinda breezy, but then it’s creeping

Language Arts ●

Once again, we see Eisner’s (2002) argument up on you like this creep, c-r-e-e-p, and you can

in practice. Indeed, tools influence what we think tell by the color (pauses) um and there’s no white

about. And the influence, it seems, is rather impor- spots that you have (emphasis) to get away like

tant to young writers like Rebecca. “When I get to hide or um wish something. Kendall?

258

LA_March2010.indd 258 2/2/10 10:34:39 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

Kendall: I like how you said creep . . . I think Ronthea: That!

you should add some words to your picture. Rebecca: What?

Marcus: Yeah, maybe . . . yeah (smiles). Ronthea: You put brown pastel in the rainbow.

Marcus’s description of his raging storm makes Rebecca: So?

us feel like storms are looming, doom is pend-

ing. For a quiet learner and as someone on the Ronthea: Why? It looked so pretty.

fence about writing, Marcus’s way of describ- Rebecca: Yeah but it’s a code.

ing his drawing is noteworthy because it dem- Ronthea: A code for what?

onstrates personal investment in what he has

constructed. As such, his talk about his drawing Rebecca: Well, only I know what it is.

becomes a potential entry point for meaningful Ti’ombe: Ew, I know what it is!

writing. Instead of using commercialized visu- Rebecca: No you don’t. [whispers] Ronthea,

als, why not provide access to media, media that this is a code for how I feel.

really interests kids, where they can produce visu-

Overhearing part of this conversation, I walked

als that whet pens? Drive fingers over keyboards?

over to Rebecca’s chair and bent down to talk

Encourage conversations about writing? Illus-

to her about her code. In a lowered voice, she

trators do it all the time. Why not children in our

explained, “I put brown in the rainbow because I

classrooms?

felt sad.” When I asked what she was sad about, it

was clear The Other Side by Woodson (2001) had

CHILDREN USED TOOLS AND COLOR TO an impact on her: “I was sad at the part when they

DOCUMENT FEELINGS couldn’t be friends because I wanted them to be

Over time, as children’s relationship with media friends.” Coloring in code allowed her to uniquely

grew, many chose tools to document a feeling or address her feelings, and pastel became a pathway

feelings. Media became a vehicle through which through which feelings could be documented.

feelings were embedded through ink, wax, graph- Wanting to know more about her color choice,

ite, pastel, and paint. Diamond’s comment, “This I probed further. She explained she used brown

is me feeling kinda sad” as she pointed to and “because it’s kinda a sad color but also because

rubbed her drawing of a beach, or Marcus’s com- the girl was brown.” Again, we see purpose-

ment, “The pastel means I’m ful ways of meaning mak-

Coloring in code allowed her

happy,” illustrate how children ing on the page. But perhaps

used tools to represent personal

to uniquely address her feelings,

the real impact of Rebecca’s

feelings. Children also turned and pastel became a pathway idea to use a tool and a color to

to color as a way of document- through which feelings could express feelings lies in how she

ing their feelings: dark colors be documented. was also able to take what she

for sadness or dramatic effect; was learning about tools dur-

bright colors for joy; warm colors (e.g., yellow, ing response time and apply it in the rest of the

orange, etc.) for feelings of warmth; cool colors curriculum. Just as teachers easily come to rec-

(e.g., blue, green, etc.) for feelings of coolness or ognize cliques in classrooms, Regi and I came to

distance (Olshansky, 2008). know particular tools Rebecca and others typi-

In early October, I overheard Rebecca say, cally used as visual cues for how they felt about

“I need a pen or pencil because they’re flat and a particular math lesson, science engagement,

I feel flat today.” This remark made me wonder writer’s workshop project, etc. This is not to say

about a relationship between feelings and media. there was always a one-to-one correspondence

The table share in which Rebecca worked on her (i.e., using pencil always equals feelings of flat-

response Friedss helped me to understand how ness), but there was usually something that went

she used tools as an expression of her feelings. beyond the obvious, the words on the page, the

The following is an excerpt from that share: math problem scratched on paper, etc. And Regi

and I valued those visual cues during conferenc-

Ronthea: Cool [pause] hey why did you do ing because they provided another lens through

that? which we could understand children’s work as

Rebecca: What? writers, as artists.

259

LA_March2010.indd 259 2/2/10 10:34:39 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

Rebecca’s germ of an idea, to use media to ONE YEAR LATER

document feelings, spread across the room and

I had the opportunity to meet with 12 of the

gave peers another way of looking at response. In

15 students exactly one year after the study

a group share discussion on how illustrators and

ended. They were dispersed in three differ-

authors use pictures and words to tell a story, Dia-

ent third grades, but they shared the same cor-

mond explained how she used earth tones in paint

ridor. They also shared, without any probing or

to describe her feelings:

prompting from me, a deluge of matter-of-fact,

Diamond: I was going to draw Mr. Edward, unembellished stories of this-is-how-it-is-since-

but I decided to just draw a person instead. He’s you’ve-been-gone. In those candid exchanges, I

in the Army (points to stripe), see, and um, this learned three things: their experiences with media

says “A” for art and this says (points to splatters) changed, feelings about writing changed, feelings

I love art and uh, let me see, oh! I made Creole- about school changed.

ish colors from paint water and my mom’s from

I was flummoxed by many of their stories. I

Creole.

was not as surprised to learn, however, that pen-

Class: (snapping, to indicate applause) cil replaced their other tools. Comments like,

Rebecca: Are you finished with this response? “Com’on Miss Rebecca, how am I supposed to

think about red wind with pencil?” demonstrate

Diamond: No, I wanna write something over

the veracity of the argument about the influence of

here (points to “A”). Kamryn?

tools as well as the children’s consensus that cer-

Kamryn: This says you love art? (points to tain tools are needed in everyday learning expe-

splatters) riences. I also learned that unlined paper was a

Diamond: Yes. thing of their second-grade past. I did not have to

Kamryn: Cool, I wanna do that. take their word for it, though; I only had to look

at the “mechanized sameness” (Graham, 2007,

In this example, Diamond explained that the p. 13) of their portrait-positioned, 8 1/2" × 11"

paint splatters represented her love for art. In sev- lined papers that saluted the corridor walls like

eral interviews, I learned that paint was the only paper soldiers.

medium through which she felt she could effec-

tively communicate love; no other tool seemed

to have that kind of effect on her. She explained, FINAL THOUGHTS

“Painting makes me feel (pauses), um, I don’t The notion of medium as message has yet to be

know just like, it makes me feel things and think accepted widely as a professional discussion

about things.” worth having. However, the children of this study

For Diamond, having access to a medium begin the discussion: daily access to a variety of

through which she could think and feel made hav- drawing/writing media in the classroom has the

ing a response journal a meaningful experience potential to let children go wider and deeper in

for her. On paper, Diamond showed up in color. their meaning construction through words and

pictures (Cibic, 2007). Going wider and deeper

March 2010

She used watercolor to represent particular feel-

ings, ideas, etc., but perhaps more than this, hav- allows children to articulate complex ideas and

ing a place in which to experiment and having the feelings in diverse ways. In addition, access to a

choice about what to experiment on (e.g., lined or variety of media invites flow experiences (Csik-

Vol. 87 ● No. 4 ●

unlined paper) provided real opportunities for real szentmihalyi, 1996), where children actively par-

writing. “I like that we get to write about what ticipate in and experience the creative process.

we think about,” she told me one day in a guided The privileging of any one tool can limit such

share, adding, “It’s like, I decide, Miss Rebecca.” experiences and, as educators, we have to be care-

One day, Diamond decided to work out her feel- ful of the messages we send when we insist on

ings on the page in red marker. “Red because I one kind of writing tool.

Language Arts ●

was angry when I wrote it,” she explained. This is Thus, the popularity of pencil-use in schools

what she wrote: “If you new me you would nouw concerns me. Teachers who practice from unex-

that I Some Times hate.” Access to media con- amined beliefs may tell themselves, I should have

tributed to children’s developing a sense of self as pencils in the classroom because everyone else

learner. does or perhaps My middle school students are

260

LA_March2010.indd 260 2/2/10 10:34:39 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

Thoughts about Media Tools for Teachers

Here are some ways you can rethink your own cur- writing demanded such violation of bristles. In

ricular practices with tools: other words, the precise mood of a visual can

complement and help make clear the mood of

• While it is certainly a worthwhile pursuit to our words.

write a grant for quality art materials, you don’t

really need a lot of money to do what I did. Dol- • Open up discussion on the kinds of tools illustra-

lar stores supplied all the drawing and writing tors use in picture books. Read-aloud is a good

tools for our yearlong study. time to start these conversations. When we take

notice of techniques that make a picture work,

• Talk with your students about the tools to which we open up discussion on how visual language

you feel affectively connected. In talking about influences our sense of story. These kinds of con-

the tools that matter to us, we plant seeds for versations, as experienced in this study, can also

further discussions on how particular tools influ- position students to think deeply about word

ence what and how we write/draw. choice.

• Practice using a tool in class that you would • Experiment with using tools in unique ways.

not ordinarily use. For example, provide writ- Rebecca and her peers tilted, jabbed, or rubbed

ten feedback in gel pen instead of regular pen, their tools to experience more than one way

or write in a color you have never tried before. of expressing themselves. Meaningful experi-

Take notice of how particular tools or colors mentation with media can help prime students’

make you feel, and share with students how pages for ideas and words for stories.

those differences affect your writing/drawing

and/or stance toward writing/drawing. Even if • Offer students opportunities to share how they

you continue using pencils, you may want to use tools to construct meaning. One child’s

diversify your graphite library by including pen- unique ways with a tool can contribute to the

cils such as Lyra’s triangular groove pencil (see thought collective of others. When we encour-

www.pencils.com/collectors/pencil-library/ age students to talk about their ways with tools,

lyra-groove for an example). we provide spaces for them to develop a sense

of self as writer, artist, meaning maker (Cibic,

• Encourage talk about how a tool can be used. 2007).

Regi and I rescued discarded brushes so that we

could pluck, pull, tweeze, and separate hairs —S. Rebecca Leigh

for particular effects where the content of our

too big for markers. However, teachers who prac- tasks. Wouldn’t encouraging the use of a marker

tice from carefully observing children may ask, retain elements of the student’s process that are

How does this student’s use of markers make me often lost to the mighty eraser?

notice his writing? What is it about pastel that Perhaps most concerning are the lost or missed

seems to get conversation going? What messages opportunities to discover what can happen on the

do I send to my students in the tools that I use and page when we limit the tools through which chil-

in the tools that I make available? Teachers who dren visually and verbally respond and through

ask such questions deconstruct constrained school which they can experience the aesthetic. We know

norms and construct instead opportunities for from this study that having a meaningful rela-

learners to show their knowing through more than tionship with writing/drawing media can galva-

one medium (Leigh & Heid, 2009). nize thinking, help crystallize ideas, and provide

The faulty logic between what we say we opportunities where decision making with tools

value and what we practice in the classroom con- can usher decision making in writing. But per-

cerns me also. For example, some teachers say haps there are many more opportunities being

tools do not matter (i.e., the discussion is not missed to the infamous pencil. For example, does

worth having), yet many insist on pencil use. If having access to media influence decision mak-

the tool does not matter, why the insistence? Fur- ing in reading and, if so, in what way? How does

ther, some teachers say they want children to media affect stance toward reading experiences?

show their work (e.g., in math, in writing, etc.), Do particular tools augur figurative language?

yet many insist on pencil-use for most of these Such questions invite further inquiry as we think

261

LA_March2010.indd 261 2/2/10 10:34:40 AMViolent Red, Ogre Green, and Delicious White

about how media can deepen meaning construc- Davis, J. (2008). Why our schools need the arts. New York:

Teachers College Press.

tion across curriculum.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York: Perigee.

In this study, a relationship with media was Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York:

possible in a social, transactional, and functional Touchstone.

classroom environment that provided a frame- Eisner, E. (1998). The enlightened eye. Upper Saddle River,

work for learning in which children discovered NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

creative ways of meaning. In this model, learning Eisner, E. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. New

Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

is transformative. Marcus’s discovery of violent

Gardner, H. (1980). Artful scribbles: The significance of

red and Rebecca’s discovery of using tools to rep- children’s drawings. New York: Basic.

resent personal feelings contributed to the class Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple

thought collective on how to use media in more intelligences. New York: Basic.

meaningful ways. Regi’s discovery and mine Gardner, H. (1993). Creating minds. New York: Basic.

was the realization that teacher-held assumptions Gay, M. (1999). Stella, star of the sea. Toronto:

about tool use must be identified. Because we Groundwood.

were open about tool use, Regi and I were able Graham, M. A. (2007, May). Exploring special places: Con-

necting secondary art students to their island community.

to see the powerful relationship between being Art Education, 60(3), 12–18.

intentional with media and the impact of that on Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination. San Fran-

thought, expression, and understanding. The rela- cisco: Jossey-Bass.

tionship validated children’s wonderings, ques- Hubbard, R. (1989). Authors of pictures, draughtsmen of

tions, and curiosities and augmented feelings of words. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

self-worth. Wondering and questioning together, Johnston, P. (2004). Choice words. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

teachers can collaborate as we did to understand Leigh, S. R., & Heid, K. A. (2009). First graders constructing

meaning through drawing and writing. Journal for Learn-

the power of media. ing through the Arts: A Research Journal on Arts Integra-

As the toy of children and the medium of tion in Schools and Communities, 4(1), 1–12.

thinkers (Petroski, 2003), the pencil is a valuable Luria, A. R. (1982). Language and cognition. New York:

Wiley & Sons.

tool, indeed. Let us not put it away. But let us not

McLuhan, M. (1967). The medium is the massage (Q. Fiore,

forget either that it is one tool among many, each Illus.). New York: Bantam.

with its own meaning potential. As such, Eisner’s Mulcahey, C. (2009). The story in the picture: Inquiry and

(1998) words bear repeating, “What we come to artmaking with young children. New York: Teachers Col-

know about the world is influenced by the tools lege Press.

we have available” (p. 28). The arts help us to see Olshansky, B. (2008). The power of pictures: Creating path-

ways to literacy through art. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

beyond the given, beyond what is (Davis, 2008).

Paley, V. (1999). In the company of children. Cambridge,

That is what Marcus did; he looked beyond the MA: Harvard University Press.

given reds in the classroom and, from them, con- Peirce, C. S. (1955). Logic as semiotic: A theory of signs.

structed something new. He was thinking abduc- In J. Buchler (Ed.), Philosophical writings of Peirce

tively (Peirce, 1955). Through our invitations to (pp. 98–119). New York: Dover.

learn in the classroom, we can affect what chil- Petroski, H. (2003). The pencil: A history of design and

circumstance. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

dren come to know and how they come to know

March 2010

Pinkwater, D.M. (1993). The big orange splot. New York:

it. Now that is a professional discussion worth Scholastic.

having. Thaler, M. (2004–2009). The Black Lagoon series (J. Lee,

Illus.). New York: Scholastic.

Vol. 87 ● No. 4 ●

References Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA:

Albers, P. (2007). Finding the artist within: Creating and Harvard University Press.

reading visual texts in the English language arts classroom. Wild, M. (2006). Fox. La Jolla, CA: Kane and Miller.

Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Woodson, J. (2001). The other side. New York: Putnam.

Bridges, R. (1999). Through my eyes. New York: Scholastic.

Cibic, S. L. R. (2007). Drawing, writing, and second graders.

Dissertation Abstracts International, 69(1).

Language Arts ●

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the

psychology of discovery and invention. New York:

S. Rebecca Leigh is an assistant professor in Reading

HarperCollins.

and Language Arts at Oakland University in Rochester,

daSilva, K. E. (2001). Drawing on experience: Connecting Michigan.

art and language. Primary Voices, 10(2), 2–8.

262

LA_March2010.indd 262 2/2/10 10:34:40 AMYou can also read