Town Talk: enhancing the 'eyes and ears' of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s-1975

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Town Talk: enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the

colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975*

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

Florence Mok

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Abstract

This article offers a longer perspective on the origins and effectiveness of reforms of colonial

governance in Hong Kong. It shows that the colonial state shifted from increasingly ineffective

indirect rule to using a covert bureaucratic opinion poll, Town Talk, to assess public opinion.

The article argues that this bureaucratic device increased the organizational capacity of the

colonial state and, in so doing, enabled a constructed form of ‘public opinion’ to influence policy

formulation in a state-controlled manner without democratization. This mechanism was used as

an imperfect substitute for representative democracy. These reforms enhanced a ‘non-political’

sense of citizenship among the Hong Kong Chinese but failed to bridge a communication gap

between an unelected government and the people over whom it ruled.

By the end of the Second World War, the eruption of anti-colonial nationalism and

insurgencies in a large number of British colonies had sped up democratization and

decolonization in Asia and Africa.1 However, unlike many other British colonies, Hong

Kong largely remained an ‘unreformed colonial polity’ in the post-war period.2 The

Legislative Council, a legislature in Hong Kong, consisted entirely of state bureaucrats

and ‘unofficials’, that is, members appointed by the governor and drawn from professional

and business elites.3 The members of the Executive Council, a group that advised the

governor in policymaking, were also appointed either by the queen or the governor.4

The colonial government gained legitimacy by recruiting respected elites into the

administrative system. Although ‘unofficials’ were elected to the Urban Council, this

* I would like to thank David Clayton for his valuable advice on Hong Kong’s colonial statecraft and his encour-

agement to pursue this research. Special thanks to Cat Chong, James Fellows, Adonis Li, Allan Pang, Alan Smart and

the two anonymous reviewers, who offered insightful feedback on previous drafts of this article, and Charles Fung,

who provided important data on governance methods from the Public Records Office in Hong Kong. All remaining

errors are solely my responsibility. Open access of this article is made possible by NAP-SUG grant (research account

number: 03INS001207C420) provided by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

1

J. Darwin, The Empire Project: the Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (New York, 2009); J. Darwin,

‘Empire and ethnicity’, Nations and Nationalism, xvi (2010), 383–401, at p. 386; and R. E. Robinson, ‘Non-European

foundations of European imperialism: sketch for a theory of collaboration’, in Studies in the Theory of Imperialism,

ed. R. Owen and B. Sutcliffe (London, 1972), pp. 117–42. The Malayan Emergency and the Mau Mau Uprising

were notable examples. See e.g.,T. N. Harper, The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya (Cambridge, 1999); C. M.

Turnbull, ‘British planning for post-war Malaya’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, v (1974), 239–54; D. Anderson,

Histories of the Hanged: the Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire (New York, 2005); and C. Elkins, Britain’s Gulag:

the Brutal End of Empire in Kenya (London, 2014).

2

G. B. Endacott, Government and People in Hong Kong, 1841–1962: a Constitutional History (Hong Kong, 1964), p. 230.

3

Endacott, Government and People, p. 230; and B. C. H. Fong, ‘Executive-legislative disconnection in the

HKSAR: uneasy partnership between chief executives and pro-government parties, 1997–2016’, in Hong Kong

20 Years After the Handover: Emerging Social and Institutional Fractures After 1997, ed. B. C. H. Fong and T.-L. Lui

(Cham, 2017), pp. 45–71, at p. 50.

4

Endacott, Government and People, p. 231.

© The Author(s) 2022. Published by Oxford University https://doi.org/10.1093/hisres/htab039 Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022)

Press on behalf of Institute of Historical Research.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits

unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.2 Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975

representative assembly had only limited executive power, covering issues such as

sanitation.5 The electoral franchise of the Urban Council was also narrow, open only

to people who were qualified by income, education or profession before 1983.6 The

pressure groups that the colonial government contacted and consulted before announcing

any new policies favoured men of wealth and sectional interests.7 As Hong Kong was

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

administered primarily by ‘the British rulers and non-British, predominantly Chinese

leaders’, only ‘a restricted class in society’ was represented politically. Direct channels for

mass political participation were limited.8 The lack of progress with democratization in

Hong Kong has been labelled ‘an embarrassing puzzle’ for historians to solve.9

This structure of colonial rule was ossified by the peculiar evolution of geopolitics

in China. Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, Chinese leaders

had asserted that Hong Kong was part of China’s territory. However, they perceived the

British administration as advantageous, as Hong Kong could be used as a ‘window to

Southeast Asia, Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Western world’, a way of gathering

intelligence and generating foreign exchange.10 The colony’s ‘unique position for Chinese

both inside and outside China’ made it a strategic point for agencies of the Chinese

communist state to disseminate anti-colonial and communist propaganda in various

forms, such as newspapers, literature and films, often in response to the anti-communist

propaganda campaigns launched by the Nationalists and the United States Information

Service.11 Premier Zhou Enlai therefore argued that the recovery of Hong Kong should

‘not be measured by the narrow principle of territorial sovereignty’ but should be viewed

as ‘part of the overall strategic arrangements for the East-West struggle’.12 Instead of

liberating Hong Kong, China’s Hong Kong policy focused on ‘long-term planning and

full utilization’.13 Despite China’s toleration of the British presence in Hong Kong, the

colonial government was aware that Hong Kong was vulnerable to a communist attack,

especially in the event of a regional war between China and the United States. This

concern was further exacerbated by the scaling down of the British garrison in Hong

5

I. Scott, ‘Bridging the gap: Hong Kong senior civil servants and the 1966 riots’, Journal of Imperial and

Commonwealth History, xlv (2017), 131–48, at p. 138; and N. Miners, The Government and Politics of Hong Kong (Hong

Kong, 1975), p. 156.

6

Miners, Government and Politics, pp. 155–63.

7

Miners, Government and Politics, pp. 186–9.

8

Miners, Government and Politics, pp. 229–31; A. Y.-C. King, ‘Administrative absorption of politics in Hong Kong:

emphasis on the grass roots level’, Asian Survey, xv (1975), 422–39, at p. 425; and Endacott, Government and People,

p. 234.

9

J. Darwin, ‘Hong Kong in British decolonisation’, in Hong Kong’s Transitions, 1842–1997, ed. J. M. Brown and

R. Foot (New York, 1997), pp. 16–32, at p. 16.

10

Yaoru Jin, 中共香港政策秘聞實錄:金堯如五十年香江憶往 [Records of Secretly Transmitted Chinese

Communist Policies Towards Hong Kong: Jin Yaoru’s 50-Year Hong Kong Memoir] (Hong Kong, 1998),

pp. 4–5; also quoted in Lu Yan, ‘Limits to propaganda: Hong Kong’s leftist media in the Cold War and beyond’,

in The Cold War in Asia: the Battle for Hearts and Minds, ed. Zheng Y.–W., H. Liu and M. Szonyi (Leiden, 2010),

pp. 95–118, at pp. 101–2.

11

Florence Mok, ‘Disseminating and Containing Communist Propaganda to Overseas Chinese in Southeast

Asia through Hong Kong, the Cold War Pivot, 1949–1960’, The Historical Journal (2021), pp. 1–21 (ahead of print).

C.Y.-Y. Chu, Chinese Communists and Hong Kong Capitalists, 1937–1997 (New York, 2010); C. Loh, Underground Front:

the Chinese Communist Party in Hong Kong (Hong Kong, 2010); Wang Gungwu, ‘Hong Kong’s twentieth century:

the global setting’, in Hong Kong in the Cold War, ed. P. Roberts and J. M. Carroll (Hong Kong, 2016), pp. 1–14,

at pp. 6–7; and Lu Xun, ‘The American Cold War in Hong Kong, 1949–1960: intelligence and propaganda’, in

Roberts and Carroll, Hong Kong in the Cold War, pp. 117–39.

12

Yaoru Jin, 香江五十年憶往 [50 Years of Memories in Hong Kong] (Hong Kong, 2005), pp. 26, 33–5; and

C.-K. Mark, The Everyday Cold War: Britain and China, 1950–1972 (London, 2017), p. 39.

13

Yaoru Jin, 50 Years of Memories, pp. 30, 35; and M. F. Wong, 中國對香港恢復行使主權的决策歷程與執行

[China Resumption of Sovereignty Over Hong Kong] (Hong Kong, 1997), pp. 34, 96.

© 2022 Institute of Historical Research Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022)Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975 3

Kong due to other overseas defence commitments, such as the Korean War (1950–3).14

To avoid giving China the impression that Britain was challenging its sovereignty, a

representative electoral system was not introduced in Hong Kong and the ‘status quo’

was maintained.

However, this unreformed system of indirect rule was challenged by Hong Kong’s

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

changing demographic composition and the development of the Cold War in the post-

war period. Hong Kong’s society comprised mainly refugees from various parts of

Guangdong.15 In the late 1950s, the sojourner mentality held by recent migrants faded,

and more people began to accept that they were permanent residents of Hong Kong.16

Living in an undemocratic colonial political system began to frustrate the young, who

started to ‘reflect their life and their role in the local society, and voice their views in a

significant way’.17 As Tai-lok Lui and Stephen Chiu have observed, there was ‘a change

of popular mood’, and political culture started to shift. Identity politics faded away, and

politics became localized. There was increased discussion of political affairs in the public

domain.18 Anti-colonial movements also surged, as demonstrated by the Star Ferry

riots, the campaign for Chinese to become the official language and the Diaoyu Islands

movement.19 As the Cold War progressed, the Chinese Communist Party’s expanding

influence in Hong Kong’s government departments, trade unions and schools and its

advocacy of anti-colonial nationalism further damaged the legitimacy of colonial rule, as

the 1967 riots illustrated.20

These threats to stability encouraged colonial bureaucrats to reform the existing

political communication channels to obtain political information that was critical to

sustaining the legitimacy of the colonial state in Hong Kong. As later sections explain, the

14

For example, two battalions left Hong Kong for Korea after the outbreak of the Korean War. See S. Tsang,

Hong Kong: an Appointment with China (London, 1997), p. 77; and C.-K. Mark, ‘Defence or decolonisation? Britain,

the United States, and the Hong Kong question in 1957’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, xxxiii (2005),

51–72, at pp. 53–5.

15

C.-K. Mark, ‘The “problem of people”: British colonials, Cold War powers, and the Chinese refugees in

Hong Kong, 1949–62’, Modern Asian Studies, xli (2007), 1145–81, at p. 1146; J. S. Hoadley, ‘Hong Kong is the life-

boat: notes on political culture and socialization’, Journal of Oriental Studies, viii (1970), 206–18, at pp. 210–11; and

F. Mok, ‘Chinese illicit immigration into colonial Hong Kong, c.1970–1980’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth

History, xlix (2020), 339–67, at pp. 340–2.

16

S. Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong (London, 2004), pp. 180–2.

17

S. Tsang, A Documentary History of Hong Kong: Government and Politics (Hong Kong, 1995), p. 248.

18

T.-L. Lui and S. W. K. Chiu, ‘Social movements and public discourse on politics’, in Hong Kong’s History: State

and Society Under Colonial Rule, ed. T.-W. Ngo (London, 1999), pp. 101–8, at pp. 105–6.

19

These movements broke out for various reasons, but all had an anti-colonial aspect. For instance, the Star

Ferry riots started because of public opposition to the Star Ferry Company’s proposed fare increase, but discon-

tent ‘swiftly spread to include the government as a target’. Activists were dissatisfied with the lack of governmental

regulation over public utilities, especially their profit rate. In petitions and signature campaigns, social organizations

and Urban Councillors argued that financial statements of public transport utilities should be made open and

available to the public. Similarly, criticisms were made against colonialism and the colonial government during

the campaign to make Chinese the official language. The language issue was not only a practical problem of com-

munication between the government and the people but was also viewed as a sign of an exclusive government.

Activists demanded significant reforms in various aspects of colonial rule, including the educational, legislative

and symbolic. In the Diaoyu Islands movement, activists also protested against colonial practices in Hong Kong,

campaigning for people’s right to peaceful demonstration, especially after a number of protesters were arrested by

the police at the Japanese Consulate on 10 April 1971. See Lam W.–M., Understanding the Political Culture of Hong

Kong: the Paradox of Activism and Depoliticization (Armonk, N.Y., 2004), pp. 115–19, 126–32, 148–51; and N. Ma,

‘Social movements and state-society relationship in Hong Kong’, in Social Movements in China and Hong Kong:

the Expansion of Protest Space, ed. K. E. Kuah-Pearce and G. Guiheux (Amsterdam, 2009), pp. 45–63, at pp. 47–8.

20

Loh, Underground Front; and R. Yep and R. Bickers, ‘Studying the 1967 riots: an overdue project’, in May

Days in Hong Kong: Riot and Emergency in 1967, ed. R. Bickers and R. Yep (Hong Kong, 2009), pp. 1–18, at pp. 6–7.

Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022) © 2022 Institute of Historical Research4 Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975

introduction of democratic electoral reforms was infeasible.The government thus sought

to bridge its communication gap with the people via the City District Officer (C.D.O.)

scheme, a new device introduced in 1968. Political scientist Ian Scott interprets the

scheme as a direct response to the 1966 and 1967 riots, which he describes as a ‘watershed’

in Hong Kong political history.21 After these riots senior civil servants acknowledged that

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

the existing law and order system, which lacked an effective communication channel,

was ‘unsustainable’ and sought ‘new forms of legitimation’.22 Through this scheme, the

lower strata of society were incorporated into the administrative system, a process now

widely known as the ‘administrative absorption of politics’.23 Although the institutional

history of the scheme has been studied extensively in existing research,24 little attention

has been paid to Town Talk, a prototype polling exercise that was embedded in the

scheme and is claimed by sociologist Ambrose King to have been ‘one of the most

important channels for soliciting public opinion’.25

This article will examine this claim and explore the deeper roots and social

effects of Town Talk, a covert public opinion monitoring mechanism that became

institutionalized in the 1970s.26 Using state records in both the Public Records Office

in Hong Kong and the National Archives of the U.K., the article shows that the colonial

government in Hong Kong moved away from the increasingly ineffective indirect

rule practised in the 1950s and introduced Town Talk in 1968 to construct a sense of

public opinion. It argues that it was only through Town Talk, a unique mechanism

that was tailored to Hong Kong’s awkward post-war constitutional position, that

the undemocratic colonial government was able to monitor and understand shifting

public opinion in the Chinese communities. Unlike other intelligence devices that

primarily assisted colonial states with analysing ‘indigenous social movements, the

influence of external forces and ideologies, and the power of organized anti-colonial

nationalism’ in decolonization transitions, Town Talk also served the Chinese society

by allowing increased political participation.27 The findings derived from the exercise

21

I. Scott, Political Change and the Crisis of Legitimacy in Hong Kong (Honolulu, 1989), pp. 107–10. Scholars tend

to believe that the 1966 and 1967 riots were turning points in Hong Kong history. The Star Ferry riots took place

in April 1966. In 1965 the colonial government announced that the Star Ferry Company had applied for a fare

increase of between 50 and 100 per cent.The Transport Advisory Committee approved the increase in March 1966.

A protest initiated by So Sau-chung and Lo Kei took place in early April 1966 but was suppressed by the colonial

government. Subsequently, the peaceful demonstrations turned into a violent riot, in which vehicles were burnt

and shops were looted. One person died and many were injured. More than 1,800 people were arrested. In 1967

demonstrations broke out in May due to labour disputes in shipping, taxi, textile, cement and artificial flower com-

panies. Pro-Beijing trade unions were involved. The demonstrations soon developed into violent riots between

pro-Beijing leftists and the Hong Kong government. Bombs were placed in various locations.The turmoil did not

subside until October. Fifty-one people were killed and 832 people were injured. More than 4,900 people were

arrested. See Bickers and Yep, May Days in Hong Kong. After the two riots administrative reforms were introduced

by the colonial government to improve political communication.

22

Scott, ‘Bridging the gap’, pp. 132–3, 138, 144.

23

King, ‘Administrative absorption of politics’, p. 424.

24

Scott, Political Change, pp. 107–10; Tsang, Modern History, pp. 189–90; King, ‘Administrative absorption of

politics’, pp. 431–2; J. M. Carroll, A Concise History of Hong Kong (Hong Kong, 2007), pp. 158–9; and S.-H. Lo, The

Politics of Democratization in Hong Kong (London, 1997), p. 38.

25

King, ‘Administrative absorption of politics’, pp. 433–4.

26

The Movement of Opinion Direction, also known as MOOD, was a covert device used by the colonial ad-

ministration to solicit public opinion after 1975. See F. Mok, ‘Public opinion polls and covert colonialism in British

Hong Kong’, China Information, xxxiii (2019), 66–87.

27

In this article intelligence is defined as secret information of political value (M. Thomas, ‘Intelligence provid-

ers and the fabric of the late colonial state’, in Elites and Decolonization in the Twentieth Century, ed. J. Dulffer and

M. Frey (Basingstoke, 2011), pp. 11–35, at p. 19).

© 2022 Institute of Historical Research Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022)Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975 5

were transferred to the policy formulation process, being used by policymakers to

devise appropriate strategies and policies that cultivated a ‘non-political’ sense of

citizenship among the Chinese population.This ‘non-political’ sense of citizenship was

crucial to the stability of Hong Kong; it was used as a ‘substitute’ for ‘national loyalty’,

which the colonial regime could not instill.28 This article contributes to the study of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

intelligence gathering and political communication in the age of decolonization by

showing how the late colonial government in Hong Kong used Town Talk to both

uphold its power and widen channels of political participation covertly in a state-

controlled manner without democratization. This technique was vital to sustaining

the legitimacy of the undemocratic government, which was challenged by surging

anti-colonial sentiment and increased aspirations among the public to engage in

political activities amid widespread decolonization.

The article is divided into six sections. The first section examines the existing

literature on Hong Kong’s political system and the C.D.O. scheme, pointing out

the significance and implications of this research. The second section explains why

China opposed Hong Kong’s democratization and why Britain accepted China’s

preferred constitutional arrangement. The third section investigates why the colonial

administration gradually moved away from indirect rule via elites in the late 1950s and

early 1960s. The fourth section explores the mechanism of Town Talk and analyses

why it was adopted as a substitute for democratization. The fifth section outlines

Town Talk’s limitations and its enhancement in the 1970s. The last section details

how Town Talk improved the government’s organizational capacity and contributed

to an emergent ‘non-political’ sense of citizenship among the Hong Kong Chinese

population.

*

Most scholars argue that before the 1970s, rather than having ‘comprehensive control’

over the Chinese society, the colonial government in Hong Kong practised a laissez-faire

and indirect form of rule.29 Despite the absence of direct state–society communication

channels, the colonial government consulted Chinese leaders and business elites

extensively before implementing important policies, primarily through the committee

system of the Legislative and Urban Councils, permanent and ad hoc advisory bodies, and

commissions of inquiry.30 This ‘government by discussion’, according to historian George

Endacott, ‘ensure[d] that difficulties’ were ‘ironed out at an early stage’, with ‘those likely

to be adversely affected’ able to make themselves ‘heard’.31 This indirect ‘policy of serving

common interests’ did not incorporate ordinary people into the administrative system

and the policymaking process.32 The notion that there were limited contacts between

the ‘autonomous bureaucratic polity’ and an ‘atomistic Chinese society’ continued to

gain currency in the 1980s and was refuted only by revisionist scholars in the 1990s, who

28

R. Yep and T.-L. Lui, ‘Revising the golden era of MacLehose and the dynamics of social reforms’, China

Information, xxiv (2010), 249–72, at p. 256.

29

J. Osterhammel, Colonialism: a Theoretical Overview (Princeton, 1997), pp. 60–1; A. Rabushka, Hong Kong: a

Study in Economic Freedom (Chicago, 1979); M. Friedman and R. Friedman, Free to Choose: a Personal Statement

(Harmondsworth, 1980), pp. 36, 54–5; and T.-W. Ngo, ‘Colonialism in Hong Kong revisited’, in Ngo, Hong Kong’s

History, pp. 1–12, at p. 3.

30

Endacott, Government and People, pp. 231–9.

31

Endacott, Government and People, pp. 229, 239.

32

Endacott, Government and People, pp. 230, 240.

Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022) © 2022 Institute of Historical Research6 Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975

pointed out that the state had far-reaching penetrating power over the Chinese society,33

with frequent interactions between the people and the colonial government through

informal political activities such as protests and petitions.34

In 1975, while acknowledging that the political system in Hong Kong was a ‘synarchy’,

‘a form of elite consensual government’, Ambrose King pointed out that the colonial

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

government had made increased efforts to incorporate the grassroots associations and

individuals into the administrative system after the 1966 and 1967 riots.This ‘administrative

absorption of politics’ was done through the C.D.O. scheme introduced in 1968.35 The

scheme was perceived as an official attempt at ‘decentralization and debureaucratization’

that evaluated and addressed popular grievances.36 However, according to King, the

C.D.O.s possessed only ‘recommendary power’ and lacked executive power.37 In 2017

Ian Scott reiterated that the scheme had been introduced to widen channels of political

participation without introducing democratization or delegating further executive power

to the Urban Council.38 He believed that the scheme, an administrative solution, had

been developed to bridge the ‘gap’ between the state and the Chinese society, as there

was a general ‘antipathy’ among senior civil servants towards elections and devolution of

government functions.39 Neither King nor Scott investigated how Town Talk functioned

as a substitute for representative democracy.

This article builds on the existing literature on the C.D.O. scheme and focuses on the

underexplored Town Talk. Town Talk provided the undemocratic colonial government

with increased capacity to gather valuable intelligence on public opinion and widened

the channels of political participation for the Chinese populace without provoking

China. It demonstrates that the colonial administration was not merely ‘a government

by discussion’ that engaged Chinese professional and business elites. And despite King’s

argument, Town Talk did not only absorb ordinary Chinese people at the grassroots

level into the administrative system but also incorporated them into the executive

policymaking process. However, with Town Talk’s existence being concealed from the

public, the colonial government had the leeway to decide when to follow public opinion;

the exercise’s function as an intelligence device was prioritized over its aim of increasing

popular political participation.

*

After the Second World War representative democracy was not introduced in Hong Kong

despite widespread decolonization in Asia and Africa. The lack of constitutional reform

was due largely to the British assumption that the People’s Republic of China, which

believed that the treaties that governed Hong Kong’s status were unequal and invalid,

would oppose Hong Kong’s democratization.40 While acknowledging that Hong Kong

33

Sociologist Lau Siu-kai argued that Hong Kong was a ‘minimally-integrated social-political system’ and that pol-

itics took place only at the boundary between the state and society and for the most part was not ‘institutionalized in

a formal or legal sense’. See Lau S.–K., Society and Politics in Hong Kong (Hong Kong, 1982), pp. 19, 121. For revisionist

work, see e.g., Ngo, ‘Colonialism in Hong Kong revisited’, pp. 2–6; D. Clayton, ‘From laissez-faire to “positive non-

interventionism”: the colonial state in Hong Kong Studies’, Social Transformations in Chinese Societies, ix (2013), 1–20, at

p. 2; and N. Ma, Political Development in Hong Kong: State, Political Society, and Civil Society (Hong Kong, 2007), p. 25.

34

Lam, Understanding the Political Culture, pp. 22, 24–6; and Lui and Chiu, ‘Social movements’, pp. 105–6.

35

King, ‘Administrative absorption of politics’, pp. 424–5, 431.

36

King, ‘Administrative absorption of politics’, pp. 431–4.

37

King, ‘Administrative absorption of politics’, p. 436.

38

Scott, ‘Bridging the gap’, p. 144.

39

Scott, ‘Bridging the gap’, p. 131.

40

Tsang, Appointment With China, p. 69.

© 2022 Institute of Historical Research Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022)Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975 7

was ruled by Britain for economic and strategic reasons, China refused to recognize the

colony as a sovereign state and argued that its sovereignty was ‘a matter “left by history’”

that should be ‘resolved through negotiations when the conditions were ripe’.41 In the

1950s British officials were uncertain whether the Chinese government would object

to Hong Kong’s democratization.42 However, in the mid 1960s the notion that China

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

would not accept any attempt to democratize Hong Kong became widely accepted

by senior bureaucrats in Britain and Hong Kong. This idea was derived from China’s

opposition to any changes in Hong Kong’s constitutional status and the fact that the

British associated the introduction of democratic electoral reforms with self-government

and independence based on their experiences in other colonies.43 By 1967 British

officials were convinced that China would object to any democratic development in

Hong Kong.44 The introduction of elections that might lead to the emergence of pro-

Nationalist Hong Kong-based politicians was also perceived as problematic and as a

move that would be strongly opposed by China.45 This settlement reflected Britain’s

strategic weakness in East Asia.

By the end of the Second World War the British Empire was on the wane and Britain

was experiencing a serious disparity between its capacities and its obligations, which

affected Hong Kong’s defence and vulnerability. Although the colony’s garrison was

strengthened shortly after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, it was soon

scaled down in 1950 because of the outbreak of the Korean War and the high cost

involved in maintaining the British forces.46 Also, Britain’s strategic interest in retaining

Hong Kong had diminished greatly after the Second World War, although it still

benefited from the colony financially.Therefore, in 1952 the British government decided

to abandon its plans to defend Hong Kong in the event of a full-scale communist

invasion and instead only maintain the garrison to ensure internal security and cover a

possible evacuation.47 By the late 1950s the size of the local garrison was further reduced,

as most were redeployed elsewhere. For example, the Royal Navy maintained only a

frigate and six minesweepers in Hong Kong in 1957.48 Hong Kong’s vulnerability was

further aggravated by the reluctance of the United States to defend it. Although the

American military build-up had expanded considerably during the presidency of Dwight

Eisenhower, the United States refused to defend the colony, as this ‘would require the

establishment of a military position well inland’ and ‘a movement of large-scale forces

into China’ that might provoke a global conflict.49 As the 1967 riots demonstrated, Hong

Kong’s internal stability and external security rested largely on the Chinese government’s

willingness to maintain the status quo.50 Understanding the colony’s vulnerability, the

41

Tsang, Appointment With China, pp. 69–71; and People’s Daily, 8 March 1963.

42

Tsang, Modern History, p. 206.

43

Tsang, Modern History, p. 207; and The National Archives of the U.K. (hereafter T.N.A.), FCO 40/42, Hong

Kong to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, 18 March 1967.

44

Tsang, Modern History, p. 207; and T.N.A., FCO 40/42, Hong Kong to the Foreign and Commonwealth

Office, 20 March 1967.

45

Miners, Government and Politics, p. 6.

46

Tsang, Appointment With China, pp. 76–7.

47

Miners, Government and Politics, pp. 19, 25, 223.

48

Tsang, Appointment With China, p. 77; and T.N.A., CO 1030/825, telegram from P. G. F. Dalton to Johnson,

28 March 1957.

49

Tsang, Appointment With China, p. 76; and Tsang, Modern History, p. 157.

50

Public Records Office of Hong Kong (hereafter H.K.P.R.O.), HKRS 742–15–22, ‘The government in Hong

Kong: basic policies and methods’, 14 May 1969, enclosed in ‘Countering subversion: government policies’, tele-

gram from Hugh Norman Walker to D. C. C. Luddington, 16 May 1969, p. 1.

Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022) © 2022 Institute of Historical Research8 Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975

colonial government believed that it should ‘avoid provoking [China] unnecessarily’ and

‘consider very carefully any actions to which the Chinese People’s Government would

feel bound to react to [sic]’, which included the introduction of democratic reforms

that would challenge China’s sovereignty over Hong Kong and ‘open [the] door to a

confrontation between left-wing and right-wing supporters’.51

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

In addition, possessing limited natural resources, Hong Kong’s survival ‘depend[ed]

substantially upon Chinese goodwill’.52 For example, by 1967 about 60 per cent of

vegetables, 85 per cent of eggs and 90 per cent of pork consumed in Hong Kong monthly

came from the mainland.53 Hong Kong imported approximately 15,000 million gallons

of water from China annually under the Dongshen–Hong Kong Water Supply Scheme,

which was developed in 1965.54 The control of illegal immigration also very much relied

on China’s ‘effective border control’.55 As the defence secretary pointed out in 1970, given

that Hong Kong was ‘considerably dependent upon China’, its policies consequently ‘can

hardly be as provocatively anti-communist as those of countries further removed from

the shadow of China’.56 The British and colonial governments therefore acknowledged

that democratization was infeasible in Hong Kong:

Many people will tell us – and often do – that none of this is as effective in promoting the rights

of the citizen as democratic self-government but it is commonly held that the Chinese govern-

ment will accept the status of Hong Kong only for as long as there are no constitutional develop-

ments which might be interpreted as pointing towards self-government … You will therefore not

find in government policy any intention to promote sophisticated western democratic institu-

tions. We have to get our public participation in other ways.57

Influenced by these factors, Hong Kong continued to practise indirect rule in the post-

war period. Despite the absence of democratization, there was an informal devolution of

power from London to Hong Kong from the 1950s onwards,‘a partial substitute for Hong

Kong’s control of its own administration’.58 As the British Empire declined, the expertise

and resources available in London to oversee colonial affairs were reduced substantially,

affecting how Hong Kong was administered.59 More importantly, colonial bureaucrats

increasingly realized that the local population would be dissatisfied if the policies of the

undemocratic colonial government were ‘blatantly designed to exploit Hong Kong for

the United Kingdom’s profit’.60 To present the colonial administration as defending the

interests of a diverse range of Chinese communities, colonial officials gained greater

51

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 942–15–22, ‘Aims and policies of the Hong Kong government: text of an address by the

defence secretary at a seminar, September 1970’, attached to telegram from M. D. A. Clinton to heads of depart-

ments and Secretariat branch heads, 7 Oct. 1970, p. 2; and ‘The government in Hong Kong: basic policies and

methods’, pp. 2, 5.

52

‘Aims and policies of the Hong Kong government’, p. 2.

53

T.N.A., FCO 21/214, telegram from David Trench to the Commonwealth Office, 16 June 1967.

54

‘Aims and policies of the Hong Kong government’, p. 2; and D. Clayton, ‘The roots of regionalism: water

management in postwar Hong Kong’, in From a British to a Chinese Colony? Hong Kong Before and After the 1997

Handover, ed. G. C.-H. Luk (Berkeley, Calif., 2017), pp. 166–85.

55

‘Aims and policies of the Hong Kong government’, p. 2; see also Mok, ‘Chinese illicit immigration’.

56

‘Aims and policies of the Hong Kong government’, p. 2.

57

‘Aims and policies of the Hong Kong government’, p. 8.

58

L. F. Goodstadt, Uneasy Partners: the Conflicts Between Public Interest and Private Profit in Hong Kong (Hong

Kong, 2009), p. 55.

59

In the 1960s Britain’s organizational capacity to administer colonies was greatly reduced. In 1966 the Colonial

Office was absorbed into the Commonwealth Office, which was then incorporated into the Foreign Office in

1968. See Goodstadt, Uneasy Partners, pp. 47–51.

60

Goodstadt, Uneasy Partners, p. 52.

© 2022 Institute of Historical Research Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022)Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975 9

autonomy over policymaking. For example, the colonial government’s annual budget

was no longer subject to London’s scrutiny in 1958. Hong Kong could also control

its own capital investment, housing and social services programmes, and formulate its

own tax policies.61 The informal devolution of power was also facilitated by Hong

Kong’s remoteness; colonial bureaucrats were not afraid to dismiss London’s enquiries by

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

providing ambiguous and obscure information.62 However, on the political front, changes

were insubstantial.63 The formal channels possessed by the colonial administration to

solicit and investigate the attitudes and opinions of the Chinese communities remained

limited. Before 1968 the Public Relations Office and the Secretariat for Chinese

Affairs were the only two departments through which public opinion was gauged

systematically and regularly. The Public Relations Office, which was set up in 1946,

monitored different channels of communication to solicit public opinion. The Office’s

Press Division, in particular, reported Chinese-language newspapers’ reactions to policies

to the government by compiling ‘daily press summaries’: 260 copies of an eight-page

summary were produced and disseminated to different departments on a daily basis.64 The

Secretariat for Chinese Affairs, which possessed executive power and held memberships

of both the Executive and the Legislative Councils, assessed shifting trends in public

opinion by consulting Chinese members of both Councils, kaifong associations and

village leaders.65 It then used these findings to advise the state on Chinese customs and

presented official policies to the public outside the New Territories.66 Neither channel,

however, contacted the public directly.

Long before 1967 colonial bureaucrats had already recognized that these indirect

mechanisms failed to obtain a representative view of changing public opinion. The

Public Relations Office offered only ‘a very limited mirror view of public opinion’.67

By 1964 the Press Division of what was now the Government Information Services68

analysed the twenty-five Chinese-language newspapers with the highest circulation

figures.69 Fourteen other Chinese-language newspapers, which were considered less

mainstream and accounted for a daily circulation figure of 248,000, were not consulted.70

61

Goodstadt, Uneasy Partners, pp. 54, 62.

62

Goodstadt, Uneasy Partners, p. 52.

63

It is worth noting that by 1960 London’s mentality was still largely influenced by Alexander Grantham, who

persuaded the British government to withdraw the plan to introduce democratic reforms in Hong Kong in 1952,

arguing that the issue simply would not ‘interest the British electorate’. In 1960 Britain ruled out the possibility

of introducing any ‘radical or major changes’ in Hong Kong’s political system. See Goodstadt, Uneasy Partners,

p. 57; A. Grantham, Via Ports: From Hong Kong to Hong Kong (Hong Kong, 1965), p. 112; and R. Black, Hong Kong

Hansard, 26 March 1964, p. 153.

64

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 160–1–23, ‘The organization of the Public Relations Office’, report by J. D. Duncanson,

deputy public relations officer, Dec. 1957, pp. 3–4.

65

The term kaifong (街坊) refers to people living in the same neighbourhood. Kaifong associations (街坊會)

are non-governmental mutual aid organizations that emerged in Hong Kong after the Second World War. They

provided the neighbourhood with social services, such as education and medical care, and were one of the main

informal channels of communication between the colonial government and the Chinese communities before the

C.D.O. scheme was introduced (H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 163–1–2176, ‘S.C.A.’, memorandum from J. C. McDouall to

C. B. Burgess, 10 Apr. 1958; and A. K. Wong, The Kaifong Associations and the Society of Hong Kong [Taipei, 1972],

p. 18).

66

Due to the New Territories’ rural character, a separate administrative system was set up to administer the area.

District officers were appointed to administer the New Territories, serving as a link between the colonial state and

rural villagers. See Tsang, Documentary History, pp. 37–42.

67

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 160–4–4, Note enclosed in telegram from E. B.Teesdale to Nigel J. V.Watt, 5 Nov. 1964.

68

The Public Relations Office was renamed the Government Information Services in 1958.

69

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 160–4–4, ‘Newspapers read for compilation of press summaries’, 1964.

70

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 160–4–4, ‘Newspapers not read for compilation of press summaries’, 1964.

Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022) © 2022 Institute of Historical Research10 Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975

The Secretariat for Chinese Affairs was also ineffective in improving state–society

communication. In 1958 J. C. McDouall, the secretary for Chinese affairs, recognized

the problem:

I believe that government is very much out of touch with public opinion, except when some-

times very small section that opinion is vociferously expressed in newspapers by agitators or

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

demagogues, or through vested interests’ pressure groups. I believe that the S.C.A.’s inadequate

direct and indirect contacts with the bulk of usually inarticulate population, inarticulate as far as

public affairs are concerned, can be increasingly dangerous.71

The reluctance of Ronald Ruskin Todd, the former Chinese affairs general, to expand

the department’s responsibilities and activities from 1949 to 1955 further weakened state-

society communication.72

With escalating Cold War tensions and the shifting political culture in Hong Kong,

understanding the views of the Chinese population proved to be increasingly important

in the 1950s. As the 1956 riots had demonstrated, Cold War politics could easily trigger

political unrest.73 The absence of direct communication channels in ‘squatter and new

housing areas’ was particularly dangerous, as residents’ ‘standard of education and literacy’

was ‘not high’, making these areas more susceptible to destabilization.74 The emergence

of political consciousness and increased demands for political participation also indicated

that the existing indirect mechanisms used to gauge public opinion were obsolete. In

1957 E. B. David, the colonial secretary, observed that ‘civic spirit’ was growing rapidly

due to ‘changing political and social environments’:

The large proportion of the Chinese communities, including local born and refugees, will no

longer treat Hong Kong as a transit camp, temporary shelter or adventurer’s paradise, but as their

permanent and real home where they can settle down peacefully to bring up their young gen-

eration with determination and confidence. Moreover, the average men nowadays are not only

interested in making their own living or improving their skill and profession but are proud to

have a share in contributing to the wealth and prosperity of the community, in which, he may be

promised a fair place in the complicated social and political organization of today. Therefore, it is

my opinion that civic spirit is not made but it grows in itself, and in Hong Kong this spirit will

continue to flourish.75

Since ‘only a few formal channels were available’, many of which had an ‘unfavourable

image’, the public ‘tended to resort to strategies that operated outside the political

establishment’ to express their opinions and grievances.76 The assistant secretary

acknowledged that it was ‘very necessary’ for the colonial government to introduce

reforms to understand the mind of the ‘unorganized non-English speaking Chinese

individuals’, whose loyalty had to be sought if legitimacy was to be retained.77

In the late 1950s the Secretariat started taking initiatives to enhance the government’s

legitimacy. As the introduction of major constitutional changes was infeasible in Hong

71

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 934–17–47, ‘S.C.A.’, memorandum from J. C. McDouall to C. B. Burgess, 16 June 1958.

72

‘S.C.A.’, McDouall to Burgess, 16 June 1958.

73

On 10 October 1956, the National Day of the Republic of China, riots broke out at the Li Cheng Uk

Resettlement Estate when Resettlement Department staff removed Nationalist flags and decorations. Violence

soon ensued, resulting in over 6,000 arrests and 443 injuries. See Lam, Understanding the Political Culture, pp. 88–91;

and Mark, ‘The “problem of people”’, pp. 1148–51, 1164–5.

74

Note enclosed in telegram from Teesdale to Watt, 5 Nov. 1964.

75

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 934–17–47, ‘Increase of staff 1958/59: Community Development Office’, enclosed in

memorandum from E. B. David to J. C. McDouall, 16 Sept. 1957, pp. 1–2.

76

Lam, Understanding the Political Culture, p. 104.

77

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 163–1–2176, Memorandum from A.S. 2 to S.C.A., 14 Apr. 1958.

© 2022 Institute of Historical Research Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022)Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975 11

Kong, political citizenship that granted citizens the right to formal political participation

was not encouraged. Instead the colonial government began to promote a ‘non-political’

sense of citizenship based on two ‘essential ingredients’: ‘profitable self-interest’ and

‘selected and sectional traditional loyalties’.78 To strengthen political communication, the

colonial state implemented a number of changes. In 1958 the Secretariat was reorganized

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

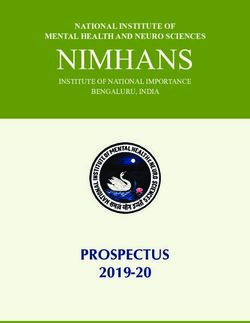

(see Figure 1). To improve its efficiency while seeking the assistance of various

departments, a clearer division of labour was introduced. For example, the secretary

for Chinese affairs was responsible for contacting Chinese members of the Executive

and Legislative Councils, the Urban Council, the Housing Authority, statutory Chinese

committees, and non-Chinese boards. The assistant secretaries for Chinese affairs

and cadet officers liaised with all other government departments, Chinese religious

organizations and the Chinese press. The Tenancy Inquiry Bureaux handled landlords

and tenants. The District Watch Force contacted village and rural communities. Liaison

officers and assistants managed kaifong associations, district commercial associations,

clansman societies and significant Chinese individuals. The colonial administration also

expanded the Secretariat. Between 1957 and 1960 its staff increased from 102 to 113.

The position of Senior Community Development Officer was added to cope with the

‘rapid increase of work’.79 To foster a sense of citizenship and belonging, the Secretariat

for Chinese Affairs was to be renamed.80 This shows the colonial regime’s commitment

to greater localization, signifying ‘the end of the colonial phase’ and ‘the beginning of

“home” rule’.81 The reorganization represented the colonial government’s impetus for

reform in the 1950s. Direct consultation was not introduced only because of inadequate

resources and the concern that a ‘stereotyped or standardized system of reporting’ would

give the impression that government servants were ‘spies or agents of “Big Brother”’.82

As the official conceptualization of public opinion generated by these indirect devices

remained unrepresentative, the colonial administration gradually departed from indirect

rule in the 1960s.

By the mid 1960s the colonial administration was still failing to grasp the shifting

sentiments of the Chinese society. As E. B. Teesdale, the colonial secretary, observed

in 1964, ‘These measures, this machinery [the Secretariat for Chinese Affairs] still

leave a good deal of ground untouched’.83 In addition, kaifong associations were in

decline, unable to recruit young leaders.84 The indirect mechanisms that solicited public

opinion through these local organizations therefore became increasingly insufficient.

Social unrest in the 1960s, notably the 1966 and 1967 riots, revealed that ‘disaffected

groups’ affected by government policies and the Chinese communists would ‘seize

every opportunity for exploiting real or imaginary grievances’; reforms were urgently

required to improve political communication and sustain colonial rule.85 To strengthen

78

‘S.C.A.’, McDouall to Burgess, 10 Apr. 1958.

79

‘Increase of staff 1958/59: Community Development Office’, p. 6.

80

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 934–17–47, ‘Short comments:Wah Man Chu (i.e. Secretariat for Chinese Affairs) should

change its name’, Sing Tao Yat Pao, 16 Sept. 1957. The department’s name, however, was not changed until 1969,

when Royal Instructions were amended. See Tsang, Modern History, pp. 190–1.

81

S. Ortmann, Politics and Change in Singapore and Hong Kong: Containing Contention (London, 2010), p. 41.

82

Note enclosed in telegram from Teesdale to Watt, 5 Nov. 1964, p. 2.

83

Note enclosed in telegram from Teesdale to Watt, 5 Nov. 1964, p. 1.

84

Lau, Society and Politics, p. 133; and A. K. Wong, ‘Chinese community leadership in a colonial setting: the

Hong Kong neighbourhood associations’, Asian Survey, xii (1972), 587–601, at pp. 592, 597, 600–1.

85

‘The government in Hong Kong: basic policies and methods’, pp. 3–4; ‘Countering subversion: government

policies’, p. 1; Scott, ‘Bridging the gap’, p. 137; and Scott, Political Change, p. 124.

Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022) © 2022 Institute of Historical Research12 Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

Figure 1. Chain of command in the Secretariat for Chinese Affairs in 1957.

Source: Public Records Office of Hong Kong, HKRS934–17–47, ‘A: present S.C.A. organisation’, in ‘Increase of

staff 1958/59: Community Development Office’, enclosed in memorandum from E. B. David to J. C. McDouall,

16 Sept. 1957.

colonial rule, the public’s grievances had to be identified and their aspirations for

political participation had to be fulfilled. The colonial administration therefore departed

from its indirect ruling strategies and in 1968 introduced the C.D.O. scheme, the

first direct state-society communication channel, which aimed to increase political

participation without implementing democratic reforms or enhancing the power of

the Urban Council.86 The scheme aligned with the informal devolution of power in

social and economic domains in the 1950s, sharing the same governance objectives of

ensuring that ‘the people of Hong Kong [would] realize that the policies of Hong Kong

government’ were ‘in their best interests’ and that a ‘sound method of local government’

could be developed so that the colonial government could ‘govern’ and ‘determine, in

partnership with those who live[d] here what [was] right for Hong Kong and its people,

and not abdicate to external pressure’.87 The government used the idea of the People’s

Association and Citizens’ Consultative Committees in Singapore as a reference.88 The

scheme was ‘a multifunctional political structure’, serving as the ‘eyes and ears’ and ‘voice’

of the government. Ten City District Offices were set up to provide policymakers with

intelligence about the public, to explain government policies, to answer public enquiries

86

Scott, ‘Bridging the gap’, p. 144; T.-L. Lui, 那似曾相識的七十年代 [The Old-So Familiar 1970s] (Hong

Kong, 2012), p. 21.

87

‘The government in Hong Kong: basic policies and methods’, pp. 2, 4.

88

The People’s Association was set up in Singapore in 1960. It was similar to the C.D.O. scheme but of different

structure and scale. It aimed to establish community centres throughout Singapore, improving two-way communica-

tions between Singapore’s legislators and people. The Citizens’ Consultative Committees, which were set up within the

Association in 1964, acted as a ‘ward heeler, opinion sampler and neighbourhood leader’, just like the City District Offices.

By 1967 there were 185 community centres across the fifty-one constituencies in Singapore. See H.K.P.R.O., HKRS

934–17–34, United States government circular, attached to letter from J. M. Patrick to J. Cater, 29 Nov. 1967, pp. 1–5.

© 2022 Institute of Historical Research Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022)Enhancing the ‘eyes and ears’ of the colonial state in British Hong Kong, 1950s–1975 13

and to manage district affairs.89 Their officers were ‘intended to be political officers’.90

Although they had ‘little executive authority initially’, their influence on government

policies was ‘considerable’.91 They were expected to ‘foresee local problems and conflicts’

and ‘initiate proposals for changes’ when needs were ‘apparent’.92 In particular, they

reported political situations in their districts to the City District Commissioners on a

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/histres/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hisres/htab039/6513319 by guest on 05 March 2022

weekly basis. Their findings were compiled into a political report and presented verbally

by the secretary for Chinese affairs at the Government House every Friday morning.93

Most importantly, unlike its predecessors, the C.D.O. scheme incorporated the lower

strata of society into the administrative system and policymaking process through a

newly invented direct mechanism called Town Talk.94 Town Talk was a covert opinion

monitoring exercise that served as a substitute for representative democracy because

‘western democratic institutions’ could not be promoted in Hong Kong and ‘other ways’

of increasing political participation had to be sought.95 As implied by its name, Town

Talk’s objective was to capture the talk and opinions of the Chinese communities in

‘town’ (Kowloon and Hong Kong island, the colony’s urban areas). It aimed to ‘detect any

strong current of public feeling’ and solicit views of ‘[men] in the street’ from ‘different

walks of life’.96 It was embedded in the C.D.O. scheme under the supervision of the

Secretariat for Chinese Affairs97 and targeted primarily ordinary Chinese people rather

than the ‘wealthier’ ‘non-Chinese people’.98 It summarized the expressions of public

opinion99 officers heard and the phenomena they observed, and it was used by high-

ranking colonial bureaucrats in policymaking:

When policies and programmes are being formulated much attention is focused upon the rel-

evance of informed and independent opinion; indeed this process is probably taken further in

Hong Kong than in most territories … In particular, the C.D.O. scheme opens up new opportu-

nities in this direction, and every advantage should be taken of the scope it offers for consulting

public opinion on particular district projects.100

Specifically, Town Talk was a key innovation among ‘a variety of methods’ that were

developed to counter the criticisms of ‘the lack of constitutional development in Hong

Kong’, gauge public opinion and mitigate popular grievances.101 The direct mechanism

allowed the colonial government’s performance to be compared ‘reasonably well with

89

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 934–17–34, D. R. Holmes, ‘Directive to City District Officers’, 20 March 1968, pp. 1–2.

90

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 934–17–34, ‘City District Officer scheme and reorganization of the Secretariat for

Chinese Affairs’, draft circular attached to memorandum from D. C. Bray to M. Gass, 26 June 1968, p. 1.

91

Holmes, ‘Directive to City District Officers’, p. 3.

92

Holmes, ‘Directive to City District Officers’, p. 2.

93

Holmes, ‘Directive to City District Officers’, p. 8.

94

Town Talk was translated as ‘街談巷議’ in Chinese. See H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 413–1–2, Translation of D. R.

Holmes, ‘The preparation of Town Talk: a guidance note’, 11 Oct. 1969.

95

‘Aims and policies of the Hong Kong government’, p. 8.

96

Holmes, ‘Directive to City District Officers’, p. 9; and H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 413–1–2, D. R. Holmes, ‘The

preparation and significance of Town Talk’, 15 Apr. 1969, p. 3.

97

The Secretariat for Chinese Affairs was renamed the Secretariat for Home Affairs in 1969, which was then

renamed the Home Affairs Department in 1973.

98

H.K.P.R.O., HKRS 413–1–2, Secretariat for Home Affairs, ‘The preparation and significance of Town Talk’,

27 Nov. 1969, p. 4.

99

The Secretariat for Home Affairs defined public opinion as ‘a majority opinion of adults’. See Holmes,

‘Preparation and significance of Town Talk’, p. 1.

100

‘The government in Hong Kong: basic policies and methods’, p. 2.

101

‘Aims and policies of the Hong Kong government’, pp. 6–7. Other methods included monitoring and analys-

ing columns in Chinese newspapers and maintaining regular contacts with rural committees and village represent-

atives in the New Territories through the District Administration.

Historical Research, vol. XX, no. XX (XXXX 2022) © 2022 Institute of Historical ResearchYou can also read