The Fox in the Hen House: A Critical Examination of Plagiarism Among Members of the Academy of Management

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

姝 Academy of Management Learning & Education, 2012, Vol. 11, No. 1, 101–123. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/amle.2010.0084

........................................................................................................................................................................

The Fox in the Hen House:

A Critical Examination of

Plagiarism Among Members of

the Academy of Management

BENSON HONIG

McMaster University

AKANKSHA BEDI

Bishop’s University

Research on academic plagiarism has typically focused on students as the perpetrators of

unethical behaviors, and less attention has been paid to academic researchers as likely

candidates for such behaviors. We examined 279 papers presented at the International

Management division of the 2009 Academy of Management conference for the purpose of

studying plagiarism among academics. Results showed that 25% of our sample had some

amount of plagiarism, and over 13% exhibited significant plagiarism. This exploratory

study raises an alarm regarding the inadequate monitoring of norms and professional

activities associated with Academy of Management members.

........................................................................................................................................................................

ETHICS AND THE ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT deter such behaviors (e.g., Kock, 1999; Martin, 1994;

Schminke, 2009; Shahabuddin, 2009; Von Glinow &

Student plagiarism, facilitated by the Internet, is a

Novelli, 1982). To our knowledge, there has been no

pervasive and frustrating problem that appears to

be increasing in recent years (Flynn, 2001; Roberts, empirical research that has either investigated the

2008; Trinchera, 2001). It is not surprising, therefore, issue of plagiarism in social science research or

that a considerable amount of research has been examined some of its predictors. However, there is

conducted to investigate the factors that lead to evidence to suggest that scholars may also plagia-

such behaviors (e.g., Bolin, 2004; Davis, 1992; Gran- rize and claim portions of someone else’s work as

itz & Loewy, 2007; Kisamore, Stone, & Jawahar, their own (e.g., Bedeian, Taylor, & Miller, 2010; End-

2007; McCabe, Butterfield, & Treviño, 2006). Al- ers & Hoover, 2006).

though research on the complex interplay of situ- Our purpose in this exploratory study is to em-

ational and individual variables related to student pirically examine the issue of plagiarism by aca-

plagiarism is important (Kisamore and colleagues, demic researchers and to investigate the institu-

2007), surprisingly little attention has been paid to tional and demographic predictors of such

plagiarism in academic research and publication. behaviors. To date, the empirical literature on pla-

Moreover, much of what has been written about giarism has focused only on the predictors and

the topic is based on anecdotal and speculative effects of plagiarism conducted by students. Un-

evidence and is limited to the discussion of gen- derstanding plagiarism among academics is im-

eral principles of ethical research and strategies to portant because these are the very individuals

who are responsible, through mentoring and

teaching, for developing a new generation of

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individ- scholars. Furthermore, they are responsible for dis-

uals, whose engaging conversations and active encouragement seminating novel intellectual contributions and for

at the Academy of Management (AOM) meeting in Chicago,

2009, inspired this research project: Israel Drori; R. Edward

upholding the highest ethical standards in society.

Freeman; Yuval Kalish; Joseph Lampel; Kathleen Montgomery; From a theoretical standpoint, our study contrib-

Amalia Oliver. utes to existing literature on plagiarism that sel-

101

Copyright of the Academy of Management, all rights reserved. Contents may not be copied, emailed, posted to a listserv, or otherwise transmitted without the copyright holder’s

express written permission. Users may print, download, or email articles for individual use only.102 Academy of Management Learning & Education March

dom addresses the potential for academics engag- student plagiarism and plagiarism in academic

ing in unethical behaviors, and that offers little research. We then describe the research and the-

guidance regarding the nature and causes of the ory used to support the study hypotheses. We

diffusion of plagiarism. From a practical stand- conclude with a discussion of the study’s find-

point, an empirical examination of the prevalence ings, their implications for the Academy (includ-

of plagiarism in academic research may have im- ing recommended policies for the Academy of

plications that go beyond the hypotheses tested in Management), as well as suggestions for future

this study and influence the way management re- research.

search is conducted and reviewed.

Using evidence from past theory and research,

we argue that plagiarism by academic scholars BACKGROUND

occurs due to the growing pressure to publish re-

Student Plagiarism—A Review

search, as well as increasing pressure to publish

in high-impact top-tier journals (DiMaggio & Pow- The issue of student plagiarism has generated a

ell, 1983; Kock, 1999; Martin, 1994; Von Glinow & great deal of media and research attention and is

Novelli, 1982). Other factors, such as top social sci- an increasingly studied phenomenon in higher ed-

ence journals’ demand for complex research, in- ucation research. With respect to the nature of pla-

creasing competition, and availability of impact giarism, a variety of definitions have been offered

factor and citation count softwares such as Publish (e.g., Cottrell, 2003; Fialkoff, 1993; Hannabuss, 2001),

or Perish, have further exacerbated the pressure to which, although distinct in certain ways, generally

publish (Bedeian et al., 2010; Harzing, 2010; Lampel converge on the notion that plagiarism involves

& Shapira, 1995). However, despite these pressures, intentionally and without authorization presenting

existing mechanisms (i.e., the use of plagiarism someone else’s ideas or words, as one’s own work.

detection software such as Turnitin or Ithenticate) This ranges from minor instances, such as sloppy

to monitor academic research are rarely used in paraphrasing, to major incidents, such as inten-

the field of social science, suggesting greater in- tional word-for-word copying of someone else’s

centives for, and perhaps a higher likelihood of work without proper acknowledgment (Hawley,

“getting away” with, unethical behavior. We aim 1984). Irrespective of the type of plagiarism, that

to explore the issue of academic plagiarism, why it plagiarism and cheating among students is wide-

occurs, and how to prevent it. From a practical spread and on the rise is noteworthy (e.g., Bennett,

standpoint, discussing these questions may help 2005; Park, 2003; Whitley, 1998). For example, a lon-

raise awareness about the issue, aid in the train- gitudinal study of 474 undergraduate students by

ing of ethically responsible researchers, and influ- Diekhoff (1996) reported a significant increase in

ence scholars toward more ethical behavior. overall cheating levels from 54.1% in 1984 to 61.2%

in 1994.

Student plagiarism is by no means a new phe-

[P]lagiarism by academic scholars occurs nomenon, nor is it relegated to marginalized or

due to the growing pressure to publish periphery scholarship. For instance, examinations

research, as well as increasing pressure of Dr. Martin Luther King’s graduate work unveiled

portions of his dissertation that were directly pla-

to publish in high-impact top-tier giarized without citation (King, Jr., Papers Project,

journals. 1991). Had this come to light when he was a re-

cently minted PhD, there would have been strong

grounds to revoke his degree—in fact, a committee

To summarize, we aim to contribute to the liter- met to consider this very issue after his death,

ature on plagiarism by (1) exploring the issue of deciding to attach a letter to his dissertation indi-

academic plagiarism and outlining the reasons cating serious improprieties (Radin, 1991).

that warrant its study; (2) exploring the role of The issue of student plagiarism also received an

demographic and institutional factors, namely unprecedented surge of media attention when Pro-

gender, academic status, education, and country, fessor Bloomfield, a physics professor at the Uni-

on the percentage of plagiarism; and (3) discussing versity of Virginia, designed a computer program

practical implications for the Academy and edito- to analyze past submitted papers for repetition and

rial boards in general, by examining papers pre- plagiarized content (Schemo, 2001). The examina-

sented in one division of the 2009 annual meeting tion revealed 158 students who had plagiarized

of the Academy of Management. their work. As a result, 45 students were expelled

We begin by briefly reviewing the literature on from the university, three graduates had their de-2012 Honig and Bedi 103 grees revoked (Trex, 2009), and a new industry was Lack of English proficiency in an Anglo environ- launched specifically to examine the authenticity ment, as well as a different cultural understanding and originality of student papers (Braumoeller & regarding what constitutes plagiarism and the Gaines, 2001). These new systems, along with the sharing of knowledge, have been associated with increasing attention directed toward intellectual higher levels of academic dishonesty (Carroll, property and copyright protection, as well as the 2002; Cohen, 2004; Larkham & Manns, 2002; expansion of electronic media, have resulted in a Park, 2003). greater awareness of the implications for and eval- Research examining the impact of students’ per- uations of plagiarism (Drinan & Gallant, 2008). Not sonal characteristics on plagiarism suggests that surprising, therefore, is that a large volume of re- some individuals have a greater propensity to in- search has been conducted to investigate why stu- dulge in plagiarist activities. One such individual dents plagiarize and what can be done to discour- difference factor is the propensity to rationalize age such behavior (e.g., Coleman & Mahaffey, dishonest behaviors. Research on plagiarism and 2000; Crown & Spiller, 1998; Kisamore et al., 2007; deviant behaviors in general has argued the rele- McCabe & Treviño, 1997; Howard & Davies, 2009). vance of rationalizing or neutralizing attitudes in With respect to the causes of plagiarism, the shaping reasoning where individuals believe they relative importance of demographic, individual, are justified in behaving immorally. Research on and situational predictors of student plagiarism student plagiarism has shown a strong positive has been examined and demonstrated in a number association between cheating and neutralizing at- of studies (e.g., Bennett, 2005; Bonjean & McGee, titudes (Daniel, 1994; Haines, 1986; Jordan, 2001). A 1965; Howard, 2002; McCabe & Treviño, 1993; Mc- recent study by Rettinger and Kramer (2009), for Cabe & Treviño, 1997; McCabe, Treviño, & Butter- instance, surveyed 154 undergraduate students field, 1999; Scanlon & Neumann, 2002). Although and found that students with neutralizing attitudes there is inconsistency in the literature regarding were more likely to cheat and plagiarize. More- the association of demographic factors with pla- over, direct knowledge of others’ cheating or see- giarism, males and younger students are gener- ing others cheat had a stronger effect on those high ally found to have engaged in higher levels of in neutralization compared to those low in neutral- plagiarism than females or older students (Gra- izing attitudes. Another individual difference vari- ham, Monday, O’Brien, & Steffen, 1994; Lyer & East- able found to predict plagiarism is attitude toward man, 2006; McCabe & Treviño, 1997; Newstead, plagiarism. In his meta-analytic review of factors Franklyn-Stokes, & Armstead, 1996; Straw, 2002). predicting cheating, Whitley (1998) found that stu- One theoretical rationale for the gender difference dents with favorable attitudes toward cheating in plagiarism has been provided by sex-role so- were more likely to cheat than students with unfa- cialization theory, which argues that women are vorable attitudes. Some other personality factors more socialized to obey rules and regulations and found to be positively associated with plagiarism are, therefore, less likely to engage in dishonest are aggressive (Type A) personality (Buckley, Wi- behaviors (e.g., Ward & Beck, 1990; Whitley, Nel- ese, & Harvey, 1998); external locus of control son, & Jones, 1999). Another demographic variable (Crown & Spiller, 1998); low self-efficacy (Murdock, that has been associated with plagiarism is gen- Hale, & Weber, 2001); low self-esteem (Lyer & East- eral cognitive ability. Results indicate that stu- man, 2006); and lower levels of school identifica- dents with lower GPA scores are more likely to tion (Finn & Frone, 2004). engage in plagiarism than those with higher GPAs Plagiarism behaviors are also shaped by the (e.g., Diekhoff, 1996; McCabe & Treviño, 1997; context or the situation faced by the student (Mc- Straw, 2002), although various factors beyond an Cabe, 1993). One factor that has been positively individual’s ability may also be relevant. One rea- associated with plagiarism is students’ percep- son why students with low GPAs may plagiarize tions of peer behavior. Using the theoretical per- more is because they have a higher incentive to spective offered by social learning theory (Ban- cheat in order to raise their grades than students dura, 1986), McCabe and colleagues (McCabe, 1993; with higher GPAs (Leming, 1980). Indeed, the de- McCabe & colleagues, 2006; McCabe, Treviño, & sire to get good grades has been reported as one of Butterfield, 2002) found that students who wit- the primary motives to cheat (Bjorklund & Wenes- nessed successful cheating by their peers were tam, 1999; McCabe, 2001; Rettinger & Jordan, 2005). more likely to engage in cheating. A second factor Finally, another important factor that has been is the easy access to other’s work that the Internet associated with plagiarism is an individual’s cul- offers (Park, 2003). A recent study by Selwyn (2008) tural and linguistic background (see Hollinger, found that 69.1% of 1,222 undergraduate students 1965 for a cross-cultural view of student cheating). had engaged in some form of on-line plagiarism

104 Academy of Management Learning & Education March

during the past 12 months. In another study, Mc- ies have described specific instances of research

Cabe (2005) surveyed over 80,000 undergraduate misconduct and have offered suggestions to detect

and graduate students in the United States and and prevent such behaviors (e.g., Clarke, 2006;

Canada and found that roughly 74% of undergrad- Enders & Hoover, 2006; Errami & Garner, 2008; Kock,

uate students and 49% of graduate students para- 1999; Shahabuddin, 2009; Yank & Barnes, 2003). Our

phrased or copied a few sentences from a written purpose here is to address this gap in the literature

or an electronic source without proper acknowl- and explore the prevalence as well as the predic-

edgment. The problem is further compounded by tors of plagiarism in academic research. As we

evidence that suggests some students lack a clear explain below, plagiarism by academic scholars is

understanding of what constitutes on-line plagia- likely and may be affected by a variety of demo-

rism. For instance, some consider cutting and past- graphic and institutional factors.

ing from the Internet a good research practice

rather than an act of plagiarism (Poole, 2004;

Plagiarism in Academic Research

Straw, 2002). Research also indicates a discrep-

ancy between faculty and student perceptions of Only a few leading social science academic jour-

Internet plagiarism (McCabe, 2005). McCabe (2005), nals have acted decisively to curb plagiarism. For

for instance, found that only 57% of undergraduate example, Enders and Hoover (2004), in their survey

students and 68% of graduate students considered of 127 editors of leading economics journals, found

paraphrasing or copying a few sentences from the that only 19% had a formal plagiarism policy in

Internet without proper acknowledgment a serious place. This is surprising given the evidence that

offense. In contrast, when the same behavior was plagiarism in academic research is widespread.

presented to the faculty, 82% reported it as serious. For instance, Bedeian et al. (2010) surveyed 438

In another study, Scanlon and Neumann (2002) sur- faculty members from 104 business schools and

veyed 698 students and reported that 3% of stu- found that over 70% of the faculty members were

dents felt that faculty members did not view pur- aware of colleagues who engaged in plagiarism.

chasing papers from on-line paper mills as wrong. In another study, Enders and Hoover (2006) sur-

Interestingly, in one instance where a student was veyed 1,208 economists and found that 24.4% of

caught plagiarizing, the student went on to be- respondents identified themselves as victims of

come an on-line paper mill entrepreneur (Mannix, plagiarism—although the percentage might have

2010). Other factors that have been positively been inflated due to self-reporting bias. Evidence

linked to plagiarism are faculty tolerance of pla- from other fields suggests that plagiarism is not

giarism (McCabe, 1993); fraternity or sorority mem- only widespread, but often goes undetected. For

bership (McCabe & Treviño, 1997); difficulty of the example, a year after implementing the plagiariz-

test and decreased surveillance (Whitley, 1998). In ing screening process for its new submissions, the

contrast, a factor increasingly linked with lower editorial board of the British Journal of Anesthesia,

levels of student cheating is the presence of insti- a high-impact medical journal, reported rejecting

tutional honor codes or institutional policies that 4% of submissions on that basis (Yentis, 2010).

require students to take a pledge and maintain an In a recent editorial in the Academy of Manage-

environment of academic integrity (Bowers, 1964; ment Review, Schminke (2009) discussed both the

McCabe, 1993, 1997). McCabe (1993, 1997), for in- considerable temptation to engage in ethical vio-

stance, found that students attending academic lations at the Academy, and the rarity with which

institutions with an honor code system were not the audits, either formal or informal, are pursued.

only less likely to cheat, but also less likely to Reporting on his informal survey, approximately

rationalize or justify cheating behaviors, and more half the editors he queried had no difficulties re-

likely to discuss the importance of morality and counting ethical violations that contravened the

compliance with standards of academic integrity. clearly stated policy formulated in the Academy’s

The extensive literature on student plagiarism code of ethics. Most of the cases recounted in his

indicates not only the widespread nature of the essay reflected violations either of submission

problem, but also a growing awareness of its grav- (e.g., authors submitted to more than one journal at

ity among faculty and academics alike. And while a time) or violations of originality, referring to pa-

student plagiarism is well-discussed and policies pers “conspicuously similar to previously rejected

are in place to limit and control unethical behav- manuscripts or to papers already published in

ior, what appears to be missing is an empirical other journals” (Schminke, 2009: 587). Notably ab-

examination of the extent to which plagiarism pre- sent were instances of data fabrication or exam-

vails in academic research. This paucity of re- ples of plagiarism by one author of another. Unfor-

search is rather surprising given that several stud- tunately, given the current norms of the profession,2012 Honig and Bedi 105

data fabrication is particularly difficult to ascer- An example of a nascent violator, on the other

tain, as we do not require the distribution of raw hand, is the case of a PhD student from Greece who

data, encourage the retesting of similar studies submitted a plagiarized paper to an academic con-

(how many top journals would consider publishing ference. As a result of his attempt to distribute

a replication study?), or make any significant at- plagiarized papers at conferences (in this case,

tempts to independently verify the integrity of the Euro-Par, a Computer Science Conference), a letter

author(s)’ source or quality of data. In short, despite was distributed warning other potential conference

the existence of unethical conduct in academic organizers of his proclivities (Anonymous, 1995).

research (e.g., Yentis, 2010), our monitoring sys- Although many in our profession appear to be

tems to control such behaviors are either nonexis- suspicious of students cutting corners in an effort

tent, insufficient, or infrequently implemented. to marginally improve their grades, we seem to

Schminke’s (2009) commentary illustrates both have full confidence in our colleagues, whose in-

the range and the variability of plagiaristic activ- centives to skirt rules and policies are “limited to

ities. For example, he distinguishes between expe- less significant issues” such as tenure, reputation,

rienced scholars, who knowingly violate conven- and six-figure salaries. As editors, we place con-

tion, and new scholars, who either lack the siderable trust in our submitting authors, believ-

knowledge regarding appropriate processes or ing that the data they report have been repre-

take shortcuts to secure tenure. These arguably sented fairly, acquired honestly, and analyzed

reflect different incentives, pressures, and norma- precisely as depicted. However, there is evidence

tive practices. In the present study, we distinguish to suggest that this wholesale trust may be mis-

these two groups as either habitual plagiarizers or placed (Yentis, 2010). Schminke (2009) provided ex-

nascent plagiarizers. Habitual plagiarizers have a amples of contraventions encountered in the sub-

history of plagiarizing, while nascent plagiarizers mission process, questioning whether our

are more likely to be either doctoral students or normative scholarly expectations may be some-

junior colleagues who are new to the profession. what naive and misplaced. He cited examples of

An example of a habitual plagiarizer is the case of authors resubmitting rejected manuscripts to the

Dr. Madonna Consantine, a tenured professor at same journal, and others submitting papers under

Columbia’s Teacher’s College, who was found second review simultaneously to other journals.

guilty of plagiarizing 36 passages from a junior These individuals may be described as procedural

colleague and two students over a period of 5 years deviants or those who, rather than plagiarizing the

(Arenson & Gootman, 2008). Another example of a work of others, engage in unethical behaviors dur-

habitual plagiarizer is found in the field of man- ing the publication process. Examples include tak-

agement sciences, where author Dǎnuţ Marcu pub- ing research shortcuts, falsifying data, or ghost

lished three plagiarized papers in Studia Univer- writing. For instance, a recent court case uncov-

sitatis Babes-Bolyai Series Informatica during ered an apparently well-entrenched process of

2002–2003 and subsequently tried to publish an- ghost writing conducted by pharmaceutical com-

other “lifted” piece in the Quarterly Journal of the panies for established academics (Wilson &

Operations Research (4OR; Bouyssou, Martello, & Singer, 2009). In many cases, renowned academics

Plastria, 2009). One of Marcu’s victims wrote: were taking credit and even payment for allowing

their names to be used in a peer-reviewed publi-

A very odd thing has happened. A fellow by cation, reflecting a study they had not participated

the name of Dănuţ Marcu has plagiarized my in, and a paper they had not authored. The practice

paper in its entirety! The first two pages of his remained a largely undisclosed secret until litiga-

paper. . . are basically just a rewording of my tion brought it to light, effectively opening a Pan-

paper, down to the details of the proofs. Ap- dora’s box regarding this conduct. Further evi-

parently this is not the first time this has dence of ethical violation in medical research

happened— he has been plagiarizing papers emerged in the study by Long et al. (2009) that

for years and passing them off as his own. found 9,120 highly similar citations between pub-

Unfortunately, many of his papers fool both lished works in MEDLINE. A full text analysis of

the referees and the journals (Bouyssou et al., these citations revealed 212 articles with signs of

2009: 12). duplication with an average similarity rate of

86.2% between the duplicated and the original pa-

Marcu was subsequently “outed” and banned per. Moreover, only 22.2% of these 212 articles ref-

from publishing his work in the above journals. erenced the original article, and approximately

The plagiarized rejected piece from 4OR was later 42% contained evidence of data fabrication, incor-

published in another journal. rect calculation, and manipulated diagrams. Ob-106 Academy of Management Learning & Education March

viously, these practices, no matter how rampant or reported student cheating to the appropriate

normative, contradict editorial guidelines for peer- authorities.

reviewed journals. Thus, despite the ostensible

rigor of blind peer review, opportunities exist in

Isomorphism of the Peer Review Process

the peer review system for considerable manipu-

lation and ethical violation. Although the concept of “publish or perish” has

been synonymous with academic life in contempo-

rary times, this has certainly not always been the

case. The history of the peer review process is

[O]pportunities exist in the peer review surprisingly absent from academic discourse, de-

system for considerable manipulation spite its obvious preeminence and its implications

and ethical violation. for prestige, notoriety, and success. Academic pub-

lication evolved from journalism, when early

newspapers relied upon a single editor as sole

adjudicator. Medical journals, for example, main-

Estimating the severity of plagiarism in the tained a single editor as a gatekeeper well into the

publication process warrants an ethical yard- 19th century, as did other academic publications in

stick, if only to assess and implement appropri- the United States and United Kingdom. In France,

ate measures and censures when questionable senior editors of academic journals thought of

behaviors are identified. Bartlett and Smallwood themselves as journalists well into the 20th century

(2004) provide a 10-step hierarchical list of pla- (Burnham, 1990). Many academic journals emerged

giarist offenses, with the top five consisting of (1) primarily to broadcast the success of a particular

copying the entire work, a substantial part, para- research institute and were typically published

graphs, sentences, or clauses; (2) copying highly and edited by a single editor who, as director,

original ideas; (3) paraphrasing segments of sub- considered himself an expert in all areas related to

stantial size without new contributions; (4) para- the journal’s topic. As knowledge specialization

phrasing segments of moderate size without new increased, various editors relinquished some of

contributions; and (5) verbatim or nonverbatim their editorial control and sought external review

copying of unremarkable segments of small size advice (Burnham, 1990). Thus, it was only in the

(e.g., clauses, phrases, expressions, and neolo- 1940s, with the combination of increasing submis-

gisms). As with all rules, the above offenses and sions and the specialization of knowledge, that the

the probability of violation are dependent on systematic blind review process we are familiar

both contextual conditions, such as the degree of with today first emerged (Burnham, 1990).

transparency involved, and the characteristics of As the model for tenure diffused throughout

the rule, including enforceability and procedural North America, so did the accompanying pace of

factors (Lehman & Ramanujam, 2009). Also of in- peer-reviewed academic journals, to accommodate

terest is that there seems to be disagreement on the growing needs of junior faculty to demonstrate

the conceptualization of plagiarism and the ap- productivity to tenure-and-promotion committees.

propriate penalties attached to such behaviors. Academic tenure, originating in 12th century Eu-

For instance, Enders and Hoover (2006) found that rope, disseminated through North America by 1915,

approximately 80% of the 1,208 respondents held both as a consequence of the influence of German

the view that unattributed sentences were either institutions (White, 2000), and in response to sev-

likely or definite examples of plagiarism. How- eral faculty terminations at Stanford University

ever, 2.8% believed it was “not at all” plagiarism, (Ludlum, 1950). Peer-reviewed scholarship subse-

and 16.6% thought it was “not likely.” Recommen- quently became the primary duty of faculty (Ad-

dations regarding penalties were surprisingly ams, 2006). While peer-reviewed publication con-

restrained: 74% would likely or definitely notify tinues to be central for promotion and tenure, some

the plagiarist’s department chair, dean, or pro- universities limit the absolute number of articles

vost, 72% would place a ban on future journal submitted for promotional review (Bickel, 1991),

submissions, but slightly less than half would thus increasing the pressure to publish in high-

make the plagiarism a matter of public notice impact journals. Peer-reviewed scientific articles

(2006: 96). This reluctance to publicly report acts continue to be the means by which academic hon-

of plagiarism is not unique to plagiarism in ac- ors and promotion are distributed (Hargens, 1988).

ademic research, and is also discussed in the For example, citations in peer-reviewed journals

literature on student plagiarism where McCabe have been explicitly linked to increased income,

(1993) found that only 40% of 789 faculty members which may be considered a proxy for reputation2012 Honig and Bedi 107

and prestige (Diamond, 1986). Thus, our increased igins of institutional theory are embedded in at-

reliance on academic journal rankings to assess tempts by sociologists to understand the diffusion

individual potential in creating and publishing of mass education, compulsory state education,

new knowledge is quite evident. A survey of 252 and tertiary education (Meyer & Rowan, 1977;

management department chairs across the United Meyer, Hannan, Rubinson, & Thomas, 1979). In-

States indicated that approximately 14% of institu- stitutional theorists were struck by the apparent

tions used a formal list of journals to make person- isomorphism of educational processes, including

nel decisions such as promotion and tenure (Van subjects, curriculum, instructional guidelines,

Fleet, McWilliams, & Siegel, 2000). Moreover, the classrooms, enrollments, school design, peda-

faculty’s “intellectual capital” or the number of the gogy, and a host of associated educational de-

faculty’s publications in top-tier journals also has signs. Such expansion occurred irrespective of

implications for other indicators, such as business controls for variation of the nation state (e.g.,

school rankings, prestige, and access to grants and urbanization, energy consumption, political re-

other resources (Beamish, 2000; Miller, Glick, & gime). As stated by Ramirez and Boli (1987: 172),

Cardinal, 2005). “What all these disparate bodies of evidence un-

derscore is the universality and uniformity of edu-

cational development in recent decades . . . Edu-

cation is institutionalized at the world level and

The Institutionalization of Peer Review and

acts as a social imperative for nation states inte-

Its Consequences

grated within this institutional environment.” Us-

Higher education in management continues to fol- ing this perspective, we may observe that business

low a pattern largely set in the United States over education, including the MBA, taught with similar

a century ago. American journals, such as the pub- subdisciplines (e.g., finance, accounting, OB, oper-

lications of the Academy of Management, continue ations, strategy, etc.) has diffused through North

to play a central role in tenure, advancement, and America, across Europe, and extending to every

university rankings. The United States has contin- continent. As management education expanded,

ued to lead and even dominate in the field of man- joint ventures were established between the

agement for more than a century, establishing the United States and international universities. As a

AACSB accreditation process in 1916 and promot- result, United States professors developed interna-

ing the growth of named schools and research tional affiliations, which served to tacitly carry

chairs. Although the process and achievement of forward existing models of research and publica-

academic rank and tenure according to publica- tion standards (Bandelj, 1989). To quote one re-

tion are primarily North American inventions, search study in Eastern Europe, “Aid from interna-

there have been considerable isomorphic trends tional organizations, the activities of professional

worldwide. For example, the research assessment associations, and mimicking peer behavior have

exercise (RAE) in the United Kingdom that first all helped establish a management school as a

began in 1986 has become a systematic 5-year re- legitimate organizational form in post-socialism”

view of every public higher education facility in (Bandelj, 1989: 13).

the United Kingdom (it will be called the research Institutional theory is helpful in understanding

excellence framework in 2014). Universities are the process by which faculty publication stan-

rated according to the prestige and frequency of dards, tenure, promotion, and peer review pro-

their faculty publications and are directly re- cesses, including those related to management ed-

warded through the provision of financial re- ucation, diffused throughout the world. It helps

sources. Australian universities are presently un- predict and explain the isomorphic pressures that

dergoing a similar comparative assessment result in the diffusion of habitual and nascent pla-

exercise (Gallagher, 2010). giarizers. For example, virtually overnight, univer-

Examining how higher education models have sities that were unfamiliar with management stud-

globally disseminated is one important element in ies, such as those in Eastern Europe, suddenly

understanding where, when, and why individuals found themselves attempting to conform to stan-

choose to be habitual or nascent plagiarizers. Ex- dards and methods with which they had little or no

isting theories may assist in predicting where and experience. Institutional theorists have very well-

when the pressures to plagiarize may be greatest. conceptualized and empirically tested models by

Neo-institutional theory examines the social pro- which institutional norms are disseminated. Indi-

cesses by which structures, policies, and programs viduals engage in normative behavior either

are developed and subsequently acquire a “taken- through coercion (they are forced or cajoled into

for-granted” status (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). The or- conformity), through mimetic means (they are at-108 Academy of Management Learning & Education March

tracted by what appears to be a successful model), larly important for individuals on the periphery

or due to normative expectations (they comply to who may not otherwise have good access to

appear rational, sensible, modern, or legitimate; world-class scholarship or opportunities to col-

DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Regarding the evolution laborate and network with other members of a

of business schools, coercion took place through particular scholarly field. We maintain that an

international donors, such as the European Union, emerging untenured scholar or doctoral student

and the United States Agency for International De- has a higher incentive to plagiarize than a senior

velopment (USAID); normative isomorphism came professor or someone not at all in the professor-

through the extension of national and regional pro- ate (Kock, 1999). This is not to imply that only

fessional organizations, including accreditation doctoral students and junior faculty are likely to

bodies; and mimetic isomorphism took place engage in these activities; it is for this reason

through the alliances and cooperative agreements that we distinguish between nascent plagiariz-

developed with U.S. business schools (Ban- ers and habitual plagiarizers. Further, ceteris pa-

delj, 1989). ribus, those who have spent a greater amount of

Regarding the pressures to publish (and possibly time in the Academy are more likely to be insti-

plagiarize), U.S. reward structures are very clearly tutionalized into its norms and practices and

institutionalized and biased strongly toward re- thus less likely to plagiarize. Of course, they may

search and peer-reviewed publication (Fairweather, also become cavalier and complacent, yielding a

1993). Because management education began in subsector of habitual plagiarizers, as demon-

the United States and only later spread to Europe, strated by the examples cited here. However,

Asia, Latin America, and Africa, we would expect expectancy valence theory argues that expecta-

the normative forces to be strongest and the will- tions and valences together determine a person’s

ingness to deviate from the norm weakest in the motivation to undertake a particular behavior

United States, followed by those countries that (e.g., to plagiarize/not plagiarize). Plagiarism

were early adapters of the management education may be thus affected by expectations of publica-

model. Given the characteristics of institutional- tion, the value attached to the publication, and

ization, we would expect developed countries of the need for publication to obtain a critical net-

the western hemisphere, such as those in North work or position. Obtaining tenure is clearly an

America and Europe, along with Australia and important threshold, as it allows the individual

New Zealand, to demonstrate the most universal to maintain professional status and increases

and well-established compliance to professional individual motivation. Moreover, expectations

rules and norms. In contrast, countries that have may also be related to beliefs about the pressure

only recently adopted the institutions of peer re- to publish, amount of competition for publica-

view (e.g., Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia, tions, and success of getting one’s past plagia-

and Africa) will be less likely to comply with pro- rized work published. Thus, individuals with

fessional norms. Based on the above, we hypothe- greater incentives (e.g., untenured scholars look-

size: ing for tenure; doctoral students looking for jobs)

Hypothesis 1: The incidence of plagiarism will be will be more likely to plagiarize than others. We

higher in newly institutionalized therefore hypothesize:

(noncore) countries than those from Hypothesis 2: The incidence of plagiarism will be

more established (core) countries. higher for untenured or junior schol-

We recognize that not all individuals face the ars than for tenured or senior

same incentives or constraints, so there is a dif- scholars.

ferential in willingness to engage in risk-taking Although scholars from noncore countries are

behavior. While some individuals may have ad- more likely to plagiarize, we believe that this rela-

opted a laissez-faire approach to scholarship tionship will be stronger for untenured and new

(habitual plagiarizers), others may calculate the scholars. The incentives attached to a publication

risks versus the incentives for their specific and coupled with the noncore country’s failure to en-

highly contextual and conditional situation. For force or detect plagiarism imply that authors from

example, many doctoral students as well as these countries will be more likely to plagiarize.

some faculty members are only subsidized to We specifically argue that untenured and new

attend conferences for which their papers are scholars’ temptation to plagiarize may be espe-

accepted. Attending conferences is an important cially strong when they believe that the institu-

aspect of socialization and advances the oppor- tional norms of ethical research are virtually non-

tunity to develop important professional net- existent, allowing unethical behaviors such as

works. Networks and conferences are particu- plagiarism to go undetected. Past research has2012 Honig and Bedi 109

indicated the influence of incentives to plagiarize will be more likely to plagiarize. This relationship

and the risk of getting caught in influencing un- may be further exacerbated by institutional norms

ethical behaviors (Houston, 1983; Michaels & and policies that fail to effectively address and

Miethe, 1989; Tittle & Rowe, 1973). Houston (1983), even implicitly condone unethical behaviors such

for instance, found that the risk of getting caught as plagiarism. An academic environment where

acted as more of a deterrent to cheating for high- the norms of ethical research are relatively less

performing students who had little incentive to developed may heighten a nonnative English au-

cheat than for low-performing students. Accord- thor’s willingness to plagiarize, thus increasing

ingly, we propose the following hypothesis: the likelihood of plagiarism. The following is hy-

Hypothesis 3: Author status moderates the rela- pothesized:

tionship between an author’s coun- Hypothesis 5: Education moderates the relation-

try and incidence of plagiarism. The ship between an author’s country

positive relationship between non- and incidence of plagiarism. The

core country and incidence of pla- positive relationship between non-

giarism will be stronger for unten- core country and incidence of pla-

ured or junior scholars than for giarism will be stronger for authors

tenured or senior scholars. receiving their degrees from non-

Further, rule violation may be differentially English speaking countries.

related to the abilities of the deviant. High-

ranked, high-impact publications in manage-

ment are universally English language publica-

Gender and Plagiarism

tions (Harzing, 2010). Language skills play an

important part in the editorial and research pro- Another factor that could play an important role in

cess, and articles that are not clearly written or predicting the incidence of plagiarism is gender.

have grammatical errors are often desk rejected Kelling, Zerkes, and Myerowitz (1976), in their risk

or otherwise turned down. Good English lan- as value theory, propose risk taking as a strongly

guage skills are important for rephrasing, sum- valued masculine tendency that motivates high

marizing, and citing other individuals’ work levels of risk taking among males. Femininity, on

without resorting to cut and paste plagiarizing. the other hand, is stereotypically associated with

We maintain that a scholar with excellent Eng- lower levels of risk taking, as females tend to be

lish language reading and writing skills has less more concerned about the negative effects of their

of an incentive to plagiarize than someone who behavior on others (Robbins & Martin, 1993). The

finds the language particularly difficult. Al- masculinity–femininity distinction is crucial to un-

though we cannot measure the language profi- derstanding the specific gender roles assigned to

ciency of our sample, we can deduce, to a certain males and females (social role theory; Eagly, 1987).

extent by proxy, the level of English expertise. Masculinity, for instance, has been associated

We assume that those who studied in English- with independence, self-assertiveness, aggres-

speaking countries are more fluent in English siveness, toughness, and competitiveness (Eagly,

than those who did not, and will thus have a 1987; Gerschick & Miller, 1995; Lee & Owens, 2002).

comparatively easier time communicating and Femininity, on the other hand, has been associated

writing in English; most would have at least with more expressive and communal personality

completed their dissertation in English, which is traits such as compassion, sympathy, nurturance,

arguably a major demonstration of language sensitivity to others, and high moral standards

proficiency. We hypothesize this relationship as (Chang, 2006; Franke, Crown, & Spake, 1997; Powell

follows: & Greenhaus, 2010). These gender roles shape at-

Hypothesis 4: The incidence of plagiarism will be titudes and behaviors; research has shown that

higher for scholars that received individuals engage in behaviors that are consis-

their highest degree from a non-Eng- tent with the prevailing gender stereotypes (Adler,

lish speaking country than for those Laney, & Packer, 1993; Deaux & LaFrance, 1998).

receiving their highest degree from Viewed through the lens of risk as value theory,

an English speaking country. this suggests that males will be more likely to

Furthermore, education may also affect the rela- engage in risky behaviors. Doing so would be con-

tionship between an author’s country and the inci- sistent with their gender belief system, which es-

dence of plagiarism. As argued above, authors tablishes risk taking as an admirable masculine

who are educated in a non-English speaking coun- trait and enhances their self-esteem by winning

try but are expected to write and publish in English praise and recognition from others (Clark, Crock-110 Academy of Management Learning & Education March

ett, & Archer, 1971; Shapira, 1995; Wilson & Daly, (Hofestede, 1980) will exhibit lower levels of pla-

1985). This assertion is also consistent with the giarism than male scholars from noncore coun-

social role theory that characterizes men as more tries, many of which are higher in collectivism

thrill seeking and individualistic, and therefore, (e.g., China, Korea, Taiwan).

acknowledges aggressive and risk-taking behav- Furthermore, we argue that although gender dif-

iors as a part of the male gender role (Eagly, 1987; ferences in plagiarism may exist between different

Whitley et al., 1999; Zuckerman, Kuhlman, Thorn- cultures, overall plagiarism levels will be higher

quist, & Kiers, 1991). Indeed, a meta-analytic study for men than for women in most cultures. One

on gender differences in risk taking found that reason for this is that risk taking is an attribute of

compared to females, males were more likely to masculine psychology and the cultural differences

engage in a wide variety of risky behaviors such will be unable to entirely eliminate the risk-taking

as drinking, using drugs, intellectual risk taking, tendency (Byrnes et al., 1999). Thus, men (who are

and risky experiments, to name a few (Byrnes, more inclined to take risks than women) will be

Miller, & Schafer, 1999). There is also evidence of more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviors (Ar-

higher levels of academic cheating (Finn & Frone, nett, 1992). In his study of 105 Malaysian students

2004; McCabe & Treviño, 1997); student plagiarism and 96 Australian undergraduate students study-

(Lambert, Ellen, & Taylor, 2003); financial risk tak- ing in Australia, Egan (2008) found that tendency to

ing (Weber, Blais, & Betz, 2002); and drug use and plagiarize was higher among Malaysian males

gambling (Zuckerman & Kuhlman, 2000) among than Malaysian females. Furthermore, Malaysian

males. On the basis of the above theory and re- students studying at offshore campuses of the uni-

search, we expect parallel gender differences in versity in Malaysia were more inclined to plagia-

plagiarism among academics such that male rize than Malaysian students studying in Austra-

scholars will be more likely to engage in plagia- lia. Based on the above theory and research we

rism than female scholars: propose that:

Hypothesis 6: The incidence of plagiarism will be Hypothesis 7: Gender moderates the relationship

greater for males than for female between an author’s country and in-

scholars. cidence of plagiarism. The positive

In addition, gender may also moderate the rela- relationship between noncore coun-

tionship between country and plagiarism. Specifi- try and incidence of plagiarism will

cally, the relationship between noncore country be stronger for male scholars than

and plagiarism is likely to be stronger for male for female scholars.

scholars from noncore countries than female schol-

ars and males from core countries. Arnett’s (1992)

theory of broad and narrow socialization suggests

that the level of individual risk taking is influ- METHODS

enced by individual factors, such as level of sen- Organizational Context:

sation seeking, as well as cultural factors, such as The Academy of Management

ethical rules, autonomy, and so forth. An individu-

al’s sociocultural background (e.g., ethical norms The AOM, the largest body of academics dedicated

and beliefs, etc.) emphasizes or deemphasizes the to the study of business management issues, was

sensation seeker’s inclination to take risks. Gender founded in 1936 with a formal constitution estab-

has been shown to affect risk-taking behavior, lished in 1941. Today, the Academy has approxi-

with men preferring greater risks, resulting from mately 19,630 members from 104 nations in 25

overconfidence (Barber, Barber, & Odean, 2001). It thematic divisions; it sponsors four prestigious

has also been shown that cultures vary in per- peer-reviewed academic journals, and hosts an-

ceived risk; it was found, for example, that the nual meetings attended by over 10,000 people

Chinese were lowest perceived risk averse and (AOM website). Increasingly, AOM has drawn an

highest perceived risk seeking, as compared with international audience, as scholars from business

German, Polish, and United States respondents schools around the world participate in its annual

(Weber & Hsee, 1998). In particular, collectivist cul- conference and submit to its journals. In 2009, in-

tures were found to have cushioned individuals by dividuals representing 78 countries participated in

providing more acceptance, allowing for higher the annual meeting, representing nearly one half

risk taking (Weber & Hsee, 1998). We may thus of the 8,380 persons in the program. Approximately

anticipate that male scholars from core countries, one third of the universities that sent more than 30

such as the United States, Australia, and the participants to the annual meeting were interna-

United Kingdom, that are higher in individualism tional. With respect to plagiarism and authorship2012 Honig and Bedi 111

credit, the Academy (AOM, 2010) has a very specific that appears in it. This assumption of collective

policy, as follows: responsibility is not new and is popular in medical

research where coauthors are increasingly re-

4.2.1. Plagiarism quired to share full responsibility for the content

4.2.1.1. AOM members explicitly identify, regardless of their contribution (Nayak & Maniar,

credit, and reference the author of any data or 2006). The American Physical Society, for instance,

material taken verbatim from written work, has a formal policy for coauthors, stating that “co-

whether that work is published, unpublished, authors who are accountable for the integrity of

or electronically available. critical data reported in the paper, carry out the

4.2.1.2. AOM members explicitly cite others’ analysis, write the manuscript, present major find-

work and ideas, including their own, even if ings in the conference or provide scientific leader-

the work or ideas are not quoted verbatim or ship as bearing responsibility for all of a paper’s

paraphrased. This standard applies whether contents” (Dalton, 2002). This position is also sup-

the previous work is published, unpublished, ported by two important aforementioned ethical

or electronically available. standards set forth by AOM, that “AOM members

4.2.2. Authorship Credit ensure that authorship and other publication cred-

4.2.2.1. AOM members ensure that authorship its are based on the scientific or professional con-

and other publication credits are based on the tributions of the individuals involved” (4.2.2.1) and

scientific or professional contributions of the that “AOM members take responsibility and credit,

individuals involved. including authorship credit, only for work they

4.2.2.2. AOM members take responsibility and have actually performed or to which they have

credit, including authorship credit, only for contributed” (4.2.2.2).

work they have actually performed or to However, it must be noted that despite the spe-

which they have contributed. cific recommendations of the ethical code of con-

4.2.2.3. AOM members usually list a student duct of AOM and others, not all scholars subscribe

as principal author on multiple-authored pub- to this particular view. They may, for example,

lications that substantially derive from the consider their coauthorship as a partnership, with

student’s’ dissertation or thesis (Academy of responsibilities delegated according to expertise

Management). or preference. It may be the case that individuals

are surprised and even incapable of determining

the extent of plagiarized content when joining a

Sample

research team. The notion of professional trust and

Our sample consisted of all empirical as well as expertise has been well-socialized into our norma-

nonempirical papers presented at the Interna- tive scholarly view, and the mere idea that a col-

tional Management (IM) division of the 2009 annual league would “cheat” or “cut corners” may shock

meeting of the Academy of Management. The In- many in our profession. However, ignorance is no

ternational Management division was selected excuse for not following requirements, and we

based on its cross-cultural focus and significant have clear and explicit rules regarding intellectual

representation at the Academy (2,988 members as property, citation, and collective work and respon-

of August 12, 2010). The International division rep- sibility. This study reflects our concern that in-

resents papers from different countries and covers stances of ethical slippage are occurring with con-

a wide variety of areas, such as organizational siderable frequency. As scholars, we believe that

behavior, international business, strategic man- the Academy has an obligation to maintain the

agement, and organizational theory. The IM divi- highest standards regarding intellectual property.

sion, therefore, represents a kind of microcosm of In short, while we recognize that scholars with nor-

the overall research presented at the Academy and mative views may be uncomfortable assigning

helps extend the generalizability of our findings to equal responsibility for violations by all author-

other divisions and areas. In total, 279 papers (rep- ship team members, taking a perspective of shared

resented by 636 authors) that were available on- responsibility, which is supported by our ethical

line were selected for use. Each coauthor was con- guidelines, is the best way to reduce unethical

sidered individually, and we utilized conventional behavior in our field.

research norms, asserting that all authors share

equal responsibility for their presented work (Dal-

Coding Scheme

ton, 2002). Thus, regardless of their contribution, if

the coauthors take credit for the presented work, Two independent raters coded the studies on mul-

then they are also responsible for the plagiarism tiple dimensions, such as percentage of plagia-112 Academy of Management Learning & Education March

ized/developed countries (i.e., North American and

This study reflects our concern that European nations, Australia, and New Zealand).

instances of ethical slippage are The country from which the authors received their

occurring with considerable frequency. highest educational degree was a dummy variable

coded as 1 ⫽ English-speaking country and 0 ⫽

otherwise. Finally, gender was a dummy variable

with males coded as 0 and females, 1. Variables for

rism and paper characteristics. In order to assess which the above information was unavailable

the reliability of this coding, a random subsample were left unclassified.

of 57 studies (i.e., 20%) was independently coded by

the second author. Agreement was obtained on 49

of 57 comparisons, yielding a reliability coefficient Procedure

of 86%. Any initial differences in coding were re-

solved by way of discussion and a more careful We used the on-line plagiarism detection service,

examination until agreement was reached. Turnitin, to check papers for plagiarism. Turnitin

checks a paper for its originality by comparing it

with billions of Internet pages (live as well as

Dependent Variable cached), previously submitted student papers, pe-

The dependent variable in this study is the per- riodicals, journals, and on-line publications. Once

centage of plagiarism, defined as the ratio of pla- a paper has been uploaded on Turnitin, the web-

giarized words to the total number of words in a site generates an originality report that indicates

paper. The reference sections were excluded from the percentage of matches between the submitted

the total word count. A section was considered paper and the existing database. The website then

plagiarized if the author(s): (a) copied the entire creates an exact replica of the submitted paper,

section from another paper without proper ac- except that any text that is copied is color-coded

knowledgment, or (b) copied the section from an- and linked to its original source. However, this

other paper with proper acknowledgment but left color-coding can be deceptive, as it only specifies

out the quotation marks or page numbers, thus the use of external sources without identifying

giving the impression that the work was para- whether these sources have been properly cited. In

phrased. Since the focus of this study was on indi- addition, legitimate use of statistical phrases and

viduals plagiarizing others’ work without appro- other descriptive terms are also highlighted as

priate acknowledgment, we adopted a more plagiarized. To overcome the above limitations, we

conservative approach toward self-plagiarism. If manually checked the highlighted sections for ap-

authors used sections from their own previous

work or cited the primary source, then it was not

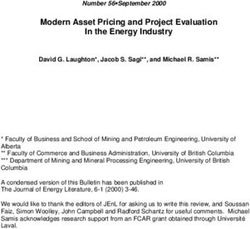

considered plagiarism. TABLE 1

Mean Number of Words Plagiarized, by Author

Characteristics

Independent Variable

Mean Number

We coded for the author’s academic status as fol- of Words

lows: 1 ⫽ student, assistant professor, lecturer, re- N Plagiarized

search assistant, nonacademic (essentially, non-

tenured or junior scholars) and 2 ⫽ associate Status

Untenured or Junior Scholars 304 76.67

professor and professor (essentially, tenured or se-

Tenured or Senior Scholars 279 86.68

nior scholars). However, we should clarify that Total 583 81.55

while in many countries, and particularly in North Country

America, associate and full professors are tenured Noncore Countries 129 203.09

faculty, in a limited number of systems it may be Core Countries 501 66.64

Total 630 94.63

possible to hold the position of untenured associ-

Gender

ate professor. Further, although tenure does not Male 379 117.30

exist worldwide, senior scholars typically enjoy Female 206 66.03

greater prestige and receive more resources. We Total 585 90.23

next coded for the country in which the author’s Education

Non-English Speaking Country 189 96.32

university was located: 1 ⫽ established (core)

English-Speaking Country 319 67.24

countries and 0 ⫽ otherwise. For the purposes of Total 508 78.06

this paper, core countries were defined as western-You can also read