The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

REVIEWS AND OVERVIEWS

The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child

Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability

and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders

Elizabeth T.C. Lippard, Ph.D., Charles B. Nemeroff, M.D., Ph.D.

A large body of evidence has demonstrated that exposure maltreatment, including alterations in the hypothalamic-

to childhood maltreatment at any stage of development pituitary-adrenal axis and inflammatory cytokines, which

can have long-lasting consequences. It is associated with may contribute to disease vulnerability and a more pernicious

a marked increase in risk for psychiatric and medical disorders. disease course. The authors discuss several candidate genes

This review summarizes the literature investigating the effects and environmental factors (for example, substance use) that

of childhood maltreatment on disease vulnerability for mood may alter disease vulnerability and illness course and neu-

disorders, specifically summarizing cross-sectional and more robiological associations that may mediate these relation-

recent longitudinal studies demonstrating that childhood ships following childhood maltreatment. Studies provide

maltreatment is more prevalent and is associated with in- insight into modifiable mechanisms and provide direction to

creased risk for first mood episode, episode recurrence, improve both treatment and prevention strategies.

greater comorbidities, and increased risk for suicidal ideation

and attempts in individuals with mood disorders. It sum-

marizes the persistent alterations associated with childhood Am J Psychiatry 2020; 177:20–36; doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010020

“It is not the bruises on the body that hurt. It is the wounds of cerebrovascular disease and stroke, type 2 diabetes, asthma,

the heart and the scars on the mind.” and certain forms of cancer. The net effect is a significant

—Aisha Mirza

reduction in life expectancy in victims of child abuse and

“We can deny our experience but our body remembers.” neglect. The focus of this review is to expand on previous

—Jeanne McElvaney, Spirit Unbroken: Abby’s Story reviews by synthesizing the literature and integrating much

recent data, with a focus on investigating childhood mal-

It is now well established that childhood maltreatment, or

treatment interactions with risk for mood disorders, disease

exposure to abuse and neglect in children under the age of 18,

onset, and early disease heterogeneity, as well as emerging

has devastating consequences. Over the past two decades,

data suggesting modifiable mechanisms that could be tar-

research has begun not only to define the consequences in the

geted for early intervention and prevention strategies. A

context of health and disease but also to elucidate mecha-

major emphasis of this review is to provide a clinically rel-

nisms underlying the link between childhood maltreatment

evant update to practicing mental health practitioners.

and medical, including psychiatric, outcomes. Research has

begun to shed light on how childhood maltreatment mediates

PREVALENCE AND CONSEQUENCES OF

disease risk and course. Childhood maltreatment increases

CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT

risk for developing psychiatric disorders (e.g., mood and

anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], It is estimated that one in four children will experience child

antisocial and borderline personality disorders, and sub- abuse or neglect at some point in their lifetime, and one in

stance use disorders). It is associated with an earlier age at seven children have experienced abuse over the past year.

onset and a more severe clinical course (i.e., greater symptom In 2016, 676,000 children were reported to child protec-

severity) and poorer treatment response to pharmacotherapy tive services in the United States and identified as victims

or psychotherapy. Early-life adversity is also associated with of child abuse or neglect (1). However, it is widely accepted

increased vulnerability to several major medical disorders, that statistics on such reports represent a significant

including coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction, underestimate of the prevalence of childhood maltreatment,

20 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020LIPPARD AND NEMEROFF

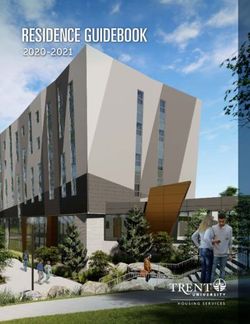

FIGURE 1. National estimates of childhood maltreatment in the United Statesa

A. National Estimate, Rounded Number of Victims (thousands) B. Rates of Victimization per 1,000 Children

1,000 14

900

12

800

700 10

600 * *

8

500

400 6

300 4

200

2

100

0 0

1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015

a

Panel A graphs the prevalence of maltreatment (calculated national estimate/rounded number of victims by year, and panel B graphs rates of vic-

timization per 1,000 children, between 1999 and 2016, as reported by the Children’s Bureau, which produces an annual Child Maltreatment report

including data provided by the United States to the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data Systems. Estimated rates of maltreatment have remained high

over the past two decades. The asterisk calls attention to the fact that before 2007, the national estimates were based on counting a child each time he

or she was the subject of a child protective services investigation. In 2007, unique counts started to be reported. The unique estimates are based

on counting a child only once regardless of the number of times he or she is found to be a victim during a reporting year. (Information obtained from

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.)

because the majority of abuse and neglect goes unreported. maltreatment is also associated with a more pernicious

This is especially true for certain types of childhood mal- disease course, including a greater number of lifetime de-

treatment (notably emotional abuse and neglect), which may pressive episodes and greater depression severity, with the

never come to clinical attention but have devastating con- majority of studies showing more recurrence and greater

sequences on health independently of physical abuse and persistence of depressive episodes (16–18). For example,

neglect or sexual abuse. Although rates of children being Wiersma et al. (19), in an analysis of 1,230 adults with major

reported to child protective services have remained relatively depressive disorder drawn from the Netherlands Study of

consistent over recent decades (Figure 1), our understand- Depression and Anxiety, found that childhood maltreatment

ing of the devastating medical and clinical consequences (measured with the Childhood Trauma Interview) was as-

of childhood maltreatment has grown, and childhood mal- sociated with chronicity of depression, defined as being

treatment is now well established as a major risk factor for depressed for $24 months over the past 4 years, independ-

adult psychopathology. In this review, we seek to summarize ent of comorbid anxiety disorders, severity of depressive

the burgeoning literature on childhood maltreatment, spe- symptoms, or age at onset. Increased risk for suicide attempts

cifically focusing on the link between childhood maltreatment and comorbidities, including increased rates of anxiety dis-

and mood disorders (depression and bipolar disorder). The orders, PTSD, and substance use disorders, are reported in

data converge to point toward future directions for education, individuals with depression who experience childhood

prevention, and treatment to decrease the consequences of maltreatment. Individuals with major depressive disorder

childhood maltreatment, especially in regard to mood disorders. and atypical features report significantly more traumatic life

events (including physical abuse, sexual abuse, and other

forms of trauma) both before and after their first depressive

CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT INCREASES RISK

episode, independently of sex, age at onset, or duration of

FOR ILLNESS SEVERITY AND POOR TREATMENT

depression (20). Additionally, childhood maltreatment has

RESPONSE IN MOOD DISORDERS

consistently been shown to be associated with poor treatment

The link between childhood maltreatment and risk for mood outcome (after psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and com-

disorders and differences in disease course following illness bined treatment) in depression, as assessed by lack of re-

onset has been well documented (2–8). Multiple studies have mission or response or longer time to remission (12, 18, 21, 22).

demonstrated greater rates of childhood maltreatment in Although the studies cited above describe a link between

patients with major depression and bipolar disorder (9–11). childhood maltreatment and a more pernicious depression

Indeed, a recent meta-analysis revealed that 46% of indi- course, most studies have been cross-sectional, and the

viduals with depression report childhood maltreatment (12). possibility of recall bias and mood effects (owing to the

Patients with bipolar disorder also report high levels of retrospective investigation of childhood maltreatment in

childhood maltreatment (13, 14), with estimates as high as individuals who are currently depressed) cannot be ruled out.

57% (15). Childhood maltreatment is associated with an in- However, studies over the past few years comparing retro-

creased risk and earlier onset of unipolar depression, with spective and prospective measurement of childhood mal-

syndromal depression occurring on average 4 years earlier in treatment suggest consistency between retrospective reports

individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment com- and prospective designs (23, 24), although a recent meta-

pared with those without such a history (12). Childhood analysis (25) suggested poor agreement between these

Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 21CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES OF CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT

measures, with better agreement observed when retro- (42) and anticonvulsants (41) in bipolar disorder. The concat-

spective measures were based on interviews and in studies enation of findings in depression and bipolar disorder are

with smaller samples. Longitudinal and prospective studies concordant in that childhood maltreatment increases risk for,

are emerging that have further confirmed and extended our and early onset of, first mood episode and episode recurrence.

understanding of the devastating consequences of childhood Childhood maltreatment affects disease trajectories, including

maltreatment on illness course (5, 7). Ellis et al. (26) recently in its association with more insidious mood episodes, poor

reported that childhood maltreatment increased risk for treatment response, a greater risk for comorbidities, and a

more severe trajectories of depressive symptoms during a greater risk for suicide ideation, attempts, and completion. The

7-year longitudinal study in 243 adolescents in the Orygen link between childhood maltreatment and increased prevalence

Adolescent Development Study. Gilman et al. (27) reported of suicide-related behaviors is of particular importance given

that childhood maltreatment increased the risk for recurrent the high rate of suicide ideation, attempts, and completion in

depressive episodes and suicidal ideation by 20%230% depression and bipolar disorder. Despite many prevention

during a 3-year follow-up of 2,497 participants diagnosed strategies (e.g., education and outreach and clinical studies

with major depressive disorder in the National Epidemio- to identify risk factors for impending suicide attempts in indi-

logic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). viduals with mood disorders), suicide rates have not decreased

Additionally, Widom et al. (7), in a study that followed a but in fact have increased in the United States. The link between

cohort of 676 children with documented childhood mal- childhood maltreatment and suicide-related behavior has been

treatment and compared risk for major depression in adult- reviewed by several groups (21, 33, 43–47). Dube et al. (48)

hood between them and a cohort of 520 children matched reported that adverse childhood experiences, including child-

on age, race, sex, and family social class who were not ex- hood maltreatment, increased the risk for suicide attempts

posed to childhood maltreatment, found a clear associa- twofold to fivefold in 17,337 adults in the now classic Adverse

tion between childhood maltreatment and both increased Childhood Experiences Study. Gomez et al. (49) reported that

risk for depression and earlier onset of the disorder. physical or sexual abuse increased the odds of suicide idea-

Although more research has been reported investigating tion, planning, and attempts among the 9,272 adolescents in

the link between childhood maltreatment and disease onset the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement.

and course in unipolar depression, more recent evidence Miller et al. (50) examined the relationship between child-

supports the link between childhood maltreatment and hood maltreatment and prospective suicidal ideation in a co-

disease onset and course in bipolar disorder (28). Childhood hort of 682 youths followed over a 3-year period. Emotional

maltreatment is associated with increased disease vulnera- maltreatment predicted suicidal ideation, independently of

bility and earlier age at onset of bipolar disorder (29). Jansen previous suicidal ideation and depressive symptom severity.

et al. (30) sought to determine whether childhood mal- Childhood maltreatment is also associated with earlier age at

treatment mediated the effect of family history on diagnosis first suicide attempt (51). Additionally, an association between

of a mood disorder. The findings indicated that one-third of childhood maltreatment and suicide risk in 449 individuals

the effect of family history on risk for mood disorders was age 60 or older was recently reported from the Multidimen-

mediated by childhood maltreatment. As with depression, sional Study of the Elderly, in the Family Health Strategy in

studies on bipolar disorder with a prospective or longitudi- Porto Alegre, Brazil (52). The effect was independent of de-

nal approach are few, but they are informative. Using data pressive symptom severity. These findings suggest that child-

from the NESARC (N=33,375), Gilman et al. (31) found that hood maltreatment increases risk for suicide-related behavior

childhood physical and sexual abuse were associated with across the lifespan. More work is warranted in investigating the

increased risk for first-onset and recurrent mania in- biological mechanisms that may mediate the association be-

dependently of recent life stress. An association between tween childhood maltreatment and suicide-related behaviors.

childhood maltreatment and prodromal symptoms has also

been reported in bipolar disorder (32), suggesting that

TIMING OF CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT: ARE

childhood maltreatment may contribute to disease vulner-

THERE PERIODS OF HEIGHTENED SENSITIVITY?

ability before onset of the first manic episode. Childhood

maltreatment in the context of bipolar disorder is also as- Although childhood maltreatment at any age can result in

sociated with a more pernicious disease course, including long-lasting consequences (53), there is evidence that the

greater frequency and severity of mood episodes (both de- timing, duration, and severity of maltreatment mediate the

pressive and manic), greater severity of psychosis symptoms, risk for later psychopathology (54). Childhood maltreatment

and greater risk for comorbidities (i.e., anxiety disorders, that occurs earlier in life and continues for a longer duration is

PTSD, substance use disorders), rapid cycling, inpatient associated with the worst outcomes (55). This is supported

hospitalizations, and suicide attempts (28, 33–41). Studies are by preclinical models (rodent and nonhuman primate) that

beginning to emerge investigating treatment response in investigated maternal separation (56, 57), a paradigm more

bipolar disorder following childhood maltreatment. Such similar to neglect in humans. One study in rodents found

studies remain few, but they suggest that childhood mal- that maternal separation during the early postnatal period

treatment is associated with a poor response to benzodiazepines (days 2–15) but not the later postnatal period (days 7–20) is

22 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020LIPPARD AND NEMEROFF

associated with anxious and depressive-like behaviors in reported that early childhood maltreatment (between birth

adulthood (57). Although this postnatal period coincides with and age 4) predicted more anxiety symptoms, and mal-

in utero development in humans, there is evidence that in treatment that occurred in late childhood or early adoles-

utero insults in the form of stress can have consequences cence (between ages 10 and 12) predicted more depressive

similar to early-life trauma (58, 59), supporting the trans- symptoms in adolescence. Taken together, these studies

lational validity of these models. Clinical studies also support suggest that maltreatment at any age and across different

the importance of timing of childhood maltreatment in contexts (physical and emotional, familial- and peer-induced)

moderating risk for psychopathology. Cowell et al. (60) in- often result in long-lasting and severe consequences

vestigated the timing and duration of childhood maltreat- and that there may be specific sensitive periods in develop-

ment in 223 maltreated children between the ages of 3 and ment when exposure to distinct types of maltreatment may

9 and found that children who were maltreated during in- differentially increase risk for affective disorders in adult-

fancy and those who experienced chronic maltreatment had hood. To date, the majority of research investigating the im-

poorer inhibitory control and working memory. Dunn et al. pact of childhood maltreatment timing on illness risk and

(61) investigated the relationship between timing of child- course in mood disorders has focused on depression. One

hood maltreatment and depression and suicidal ideation in study (69) reported that early sexual or physical abuse (before

early adulthood among 15,701 participants in the National age 11) in 225 early psychosis patients (6.7% with a bipolar

Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, and found that disorder diagnosis) coincided with lower scores on the Global

exposure to early maltreatment, especially during the pre- Assessment of Functioning Scale and the Social and Oc-

school years (between ages 3 and 5), was most strongly cupational Functioning Assessment Scale during a 3-year

associated with depression. Additionally, sexual abuse follow-up period, whereas late sexual or physical abuse

occurring during early childhood, compared with adoles- (between ages 12 and 15) did not. More work investigating

cence, was reported to be more strongly associated with timing of maltreatment and associated clinical outcomes is

suicidal ideation (61). While these studies suggest that warranted.

childhood maltreatment that occurs earlier in development

may further increase risk for developing mood disorders and

EXPERIENCING SINGLE SUBTYPES OF ABUSE AND

associated behaviors in adulthood, it is important to em-

NEGLECT VERSUS EXPERIENCING MULTIPLE TYPES

phasize that evidence suggests that exposure to maltreatment

during later childhood and adolescence also independently Several groups have sought to determine the impact of single

increases risk for mood disorders. Emotional abuse and types of childhood maltreatment on mood disorders. Al-

neglect, especially if it occurs between ages 8 and 9, increases though all types of childhood maltreatment (physical, emo-

depressive symptoms (62). Emotional abuse during adoles- tional, and sexual) increase disease vulnerability and risk for

cence also increases risk for depression (63). more severe illness course in mood disorders, including in-

More work is emerging investigating the negative con- creased risk for suicide (52), there may be some distinctions

sequences of bullying. A study of 1,420 participants (ages between individual subtypes and associated outcomes (70).

9–16) revealed that victims of bullying showed an increased An association between sexual abuse and lifetime risk for

prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and anxiety disorders, depression, and suicide attempts in-

suicide-related behavior (64). A recent study of more than dependent of other types of maltreatment has been reported

5,000 children that comprised a longitudinal data set (the (2, 71, 72). In bipolar disorder, physical abuse and sexual abuse

Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children in England independently increase risk for illness vulnerability and more

and the Great Smoky Mountains Study in the United States) severe course (13). One study of 446 youths (ages 7 to 17)

(65) found an increased risk for mental health problems, found that physical abuse was independently associated with

including anxiety, depression, and self-harm, in individuals a longer duration of illness in bipolar disorder, a greater

who experienced bullying, but not other maltreatment. Ad- prevalence of comorbid PTSD and psychosis, and a greater

ditionally, an association between childhood bullying by prevalence of family history of a mood disorder when

peers and risk for suicide-related behaviors (ideation, compared with sexual abuse, which was only associated with

planning, attempting, and onset of plan among ideators), a greater prevalence of PTSD (13). Recent life stress in

independent of childhood maltreatment by adults, was re- adulthood was found to increase risk for first-onset mania in

ported in a sample of U.S. Army soldiers (66). individuals with a history of childhood physical maltreat-

Some studies suggest that differential periods of sensitivity ment, but not individuals with a history of sexual maltreat-

to different subtypes of maltreatment are distinctly associ- ment (31). However, it should be noted that early-life sexual

ated with an increased risk for mood disorders. Recently, a abuse in the study was a strong risk factor for mania even in

stronger relationship was reported between adult depression the absence of recent life stress.

and early childhood sexual abuse (occurring at age 5 or Neglect is the least studied form of early-life adversity, and

earlier) and later childhood physical abuse (occurring at age emerging data suggest differential consequences following

13 or later), compared with maltreatment that occurred neglect as compared with abuse (73). Similarly, long-lasting

during other developmental periods (67). Harpur et al. (68) consequences following emotional maltreatment, independently

Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 23CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES OF CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT

of other forms of maltreatment, have also been reported (47, 74, of depression, experiencing multiple forms of childhood

75). In a 2015 meta-analysis, emotional abuse showed the maltreatment further elevates this risk (12). The Adverse

strongest association with depression, followed by neglect Childhood Experiences study provided evidence of an ad-

and sexual abuse (76), a finding supported by another recent ditive effect of eight early-life stress events (including abuse

meta-analysis (77). Spertus et al. (78) reported that emotional but also other early-life stressors, such as divorce, domestic

abuse and neglect predicted depressive symptoms even after violence, household substance abuse, and parental loss) on

controlling for physical and sexual abuse, further suggesting adult psychopathology. Specifically, individuals with four or

emotional abuse and neglect to be independently related more early-life stress events had significantly increased risk

to illness severity in depression. Parental “verbal aggression” for depression, anxiety, suicide attempts, substance use

was found to increase risk for depression and anxiety in ad- disorders, and other detrimental outcomes (82, 83). An ad-

olescents, with risk suggested to be greater following verbal ditive or cumulative effect of early-life stress on increased risk

aggression compared with physical abuse (79). Khan et al. (63) for mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders has also been

recently reported that nonverbal emotional abuse in males reported by others (5, 6). Multiple adverse childhood ex-

and peer emotional abuse in females are important predictors periences (maltreatment plus other forms of stressful events)

of lifetime history of major depression and are more predictive also result in higher rates of comorbidities (7, 82). Likewise,

than number of types of maltreatment experienced. Another a dose-response relationship between number of types of

recent meta-analysis (12) reported that in individuals with childhood maltreatment and illness severity in bipolar dis-

depression, emotional neglect was the most common reported order has been suggested, including increased risk for co-

form of childhood maltreatment, and emotional abuse was morbid anxiety disorders and substance use disorders (84).

most closely related to symptom severity. High prevalence of

emotional maltreatment is also reported in bipolar disorder

UNDERLYING MECHANISMS BY WHICH

(approximately 40%), with emotional maltreatment associ-

CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT INCREASES RISK

ated with disease vulnerability and more severe illness course,

FOR MOOD DISORDERS AND CONTRIBUTES TO

including rapid cycling, comorbid anxiety or stress disorders,

DISEASE COURSE

suicide attempts or ideation, and cannabis use (80).

Although studies on subtypes of maltreatment are only As depicted in Figure 2, several putative biological mecha-

now burgeoning, they are concordant in implicating emo- nisms by which childhood maltreatment may increase the

tional maltreatment, in addition to physical and sexual risk for mood disorders and disease progression have been

maltreatment, in increasing risk for, and differences in dis- described (21, 85). These include, but are not limited to, in-

ease course of, mood disorders. Emotional maltreatment and flammation and other immune system perturbations, alter-

neglect are clearly the least studied of all forms of childhood ations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and

adversity. This is in part because they are often overlooked genetic and epigenetic processes as well as structural and

and least likely to come to clinical attention, as compared with functional brain imaging changes. These studies provide

physical and sexual abuse, which can, of course, result in insight into modifiable targets and provide direction to im-

physical injury. Because emotional maltreatment and neglect prove both treatment and prevention strategies.

are likely the most prevalent forms of childhood maltreat-

ment in psychiatric populations (81), and given findings Biological Abnormalities Associated With

suggesting that independent of other forms of maltreatment, Childhood Maltreatment

emotional maltreatment has long-lasting consequences that Several persistent biological alterations associated with

increase risk for mood disorders and illness outcome (74, 75), childhood maltreatment may mediate the increased risk

more research on the role of emotional maltreatment and for development of mood and other disorders. Childhood

neglect are urgently needed. maltreatment is associated with systemic inflammation

Although the findings described above suggest the hy- (86, 87) as assessed by measurements of C-reactive pro-

pothesis that different subtypes of early-life adversity may tein (CRP) and inflammatory cytokines including tu-

independently increase risk for mood disorders and that mor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6. Childhood

some subtypes may be more closely related to specific dif- maltreatment was found to be associated with increased

ferences in illness course and severity, it is clear that subtypes plasma CRP levels and increased body mass index in

of abuse and neglect, as a rule, do not occur in isolation but 483 participants identified as being on the psychosis

instead occur together in the same individuals. For example, spectrum (88). Patients with depression and bipolar dis-

individuals experiencing physical or sexual abuse likely also order have also been reported to exhibit increased levels

experience emotional maltreatment. Some studies have in- of inflammatory markers (89–92). It is unclear whether

vestigated the impact of multiple types of childhood mal- childhood maltreatment–associated inflammation is re-

treatment. A recent meta-analysis reported that 19% of sponsible for the observations in patients with mood dis-

individuals with major depression report more than one form orders. Anti-inflammatory drugs are a promising novel

of childhood maltreatment and, while all childhood mal- therapeutic strategy in the subgroup of depressed patients

treatment subtypes have been shown to increase the risk with elevated inflammation (93), although the findings thus

24 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020LIPPARD AND NEMEROFF

FIGURE 2. Child maltreatment, its consequences, and windows for intervention across developmenta

Genetics/Epigenetics/Neuroinflammation/HPA Axis

Parenting Classes and Support,

Stress Management

Substance Use Disorders, Social Support

(Before and after birth)

Exposure Disease Vulnerability Disease Onset Disease Course/Treatment Response

Birth Childhood Adolescence Young Adulthood

Critical periods in development during which exposure to childhood maltreatment =Optimal windows for intervention

increases disease vulnerability and course =Modifiable targets for intervention

a

The gray arrow represents the development of disease vulnerability, disease onset, and variations in disease course and treatment. Exposure to

childhood maltreatment at any point during development (red bar) can result in long-lasting consequences, including increasing disease vulnerability

and illness severity in mood disorders. There may be optimal windows (black arrows) across development when interventions could decrease disease

burden by decreasing disease vulnerability and improving illness course; these include before and after birth (parenting classes and parenting support

groups), at the time of maltreatment, when prodromal symptoms begin to emerge, immediately following disease onset, and during disease course (e.g.,

improving treatment response). Modifiable targets are beginning to emerge (green arrows and text) and point to behavioral and environmental factors,

as well as genetic and other molecular factors, that could be focused on for interventions.

far are preliminary, and further study on inflammation as a pathogenesis of mood disorders following early-life stress. As

modifiable target is warranted. previously reviewed (21), studies support the interaction of

Another mechanism through which childhood maltreat- genetic predisposition and childhood maltreatment in in-

ment may increase risk for mood disorders is through al- creasing risk for mood disorders and affecting disease course.

terations of the HPA axis and corticotropin-releasing factor Indeed, this is now considered a prototype of how gene-by-

(CRF) circuits that regulate endocrine, behavioral, immune, environment interactions influence disease vulnerability.

and autonomic responses to stress. Research documenting Polymorphisms in genes comprising components of the HPA

how childhood maltreatment contributes to altered HPA axis axis and CRF circuits increase the risk for adult mood dis-

and CRF circuit activity in preclinical and clinical studies has orders in adults exposed to childhood maltreatment. For

been reviewed in detail elsewhere (21). Childhood adversity example, polymorphisms in the FK506 binding protein

likely increases sensitivity to the effects of recent life stress on 5 (FKBP5) gene interact with childhood maltreatment to

the course of both unipolar and bipolar disorder. Soldiers increase risk for major depression, suicide attempts, and

exposed to childhood maltreatment have a greater risk for PTSD (101–105). Caspi et al. (106) found that adults exposed

depression or anxiety following recent life stressors (94). to childhood maltreatment who carried the short arm allele of

Likewise, individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (hetero-

have a greater risk of mania following recent life stressors zygotes and homozygotes) exhibited an increased risk for a

compared with individuals without childhood maltreatment depressed episode, greater depressive symptoms, and greater

(31, 34). Individuals with depression or bipolar disorder and risk for suicidal ideation and attempts compared with ho-

early-life stress report lower levels of stress prior to re- mozygotes with two long arm alleles. A large number of

currence of a mood episode compared with individuals with studies now support the interaction between early-life stress,

depression or bipolar disorder without early-life stress (34, the serotonin transporter promoter, and other serotonergic

95); this suggests that less stress is required to induce a mood gene polymorphisms and disease vulnerability and illness

episode in individuals who were exposed to childhood course in depression and bipolar disorder (107–111), although

maltreatment. These findings support theoretical sensitiza- conflicting findings have also been reported (112). Childhood

tion frameworks on the role of stress in unipolar depression maltreatment has also been reported to interact with

and bipolar disorder (96–99). Alterations in the HPA axis and corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 gene (CRHR1)

CRF circuits following childhood maltreatment are mecha- polymorphisms to predict syndromal depression and in-

nisms that likely contribute to increased risk for mood epi- crease risk for suicide attempts in adults (113–115). Early-life

sodes following stressful life events and may be modifiable stress interactions with other genetic polymorphisms to in-

targets. Indeed, Abercrombie et al. (100) recently reported fluence risk for mood disorders and illness course include,

that therapeutics targeting cortisol signaling may show but are not limited to, brain-derived neurotrophic factor

promise in the treatment of depression in adults with a (BDNF) Val66Met polymorphism (116, 117), toll-like receptors

history of emotional abuse. (118), the oxytocin receptor (119), inflammation pathway

In addition to the biological mechanisms noted above, genes (120), and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (121),

genetic predisposition undoubtedly also plays a role in the although negative findings have also been reported (122).

Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 25CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES OF CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT

Studies employing polygenic risk score (PRS) analyses, an (defined as stepping on, dropping, or dragging offspring, and

approach assessing the combined impact of multiple geno- active avoidance) was associated with altered BDNF ex-

typed single-nucleotide polymorphisms, have reported that pression and methylation in the prefrontal cortex in adult

PRS is differentially related to risk for depression in indi- offspring, with adult offspring also showing poorer maternal

viduals with a history of childhood maltreatment compared care patterns when rearing their own offspring (135). Altered

with those without maltreatment (123, 124), although neg- expression and methylation of BDNF is reported in indi-

ative findings have also been reported (125). viduals with mood disorders (141, 142). These studies high-

Studies investigating the role of epigenetics (e.g., the light the importance of understanding the intergenerational

modification of gene expression through DNA methylation transmission of trauma and psychopathology to identify

and acetylation) in mediating detrimental outcomes fol- modifiable targets to improve outcomes, for example, the

lowing early-life stress have recently appeared (126). For family unit and interpersonal relationships. It is noteworthy

example, a recent study reported that hypermethylation of that while the majority of research has focused on in-

the first exon of a monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) gene region tergenerational transmission of maternal traits, research is

of interest mediated the association between sexual abuse also emerging that supports the important role of paternal

and depression (127). Childhood maltreatment is also asso- care on intergenerational transmission of behavior (131).

ciated with epigenetic modifications of the glucocorticoid More study on intergenerational transmission of trauma is

receptor (128), the FKBP5 gene (101), and the serotonin 3A needed.

receptor (129), with these modifications associated with

suicide completion, altered stress hormone systems, and Pathways to Mood Disorder Outcomes

illness severity, respectively. Childhood maltreatment– More work on mechanisms and pathways by which child-

associated epigenetic changes in individuals who died by hood maltreatment increases risk for and ultimately results

suicide have been identified in human postmortem studies in adult mood disorders is essential for early intervention.

(130). These studies, and others not cited here, support Childhood maltreatment is associated with a marked in-

gene–by–childhood maltreatment interactions, including crease in medical morbidities and an array of physical

epigenetic modifications, in risk for mood disorders and in symptoms, and in general it predicts poor health and a

illness course. shorter lifespan (143, 144). Higher rates of comorbid sub-

Epigenetics may also be one mechanism that contributes stance use disorders in individuals with mood disorders who

to the intergenerational transmission of trauma (131–133), report experiencing childhood maltreatment is of particular

although it is important to note that nongenomic mechanisms interest. Childhood maltreatment has consistently been

are also implicated in the intergenerational transmission of associated with a number of high-risk health behaviors,

behavior (134). There is a robust literature in rodent models including smoking and alcohol and drug use—behaviors

supporting the intergenerational transmission of maternal thought to contribute to the association between childhood

behavior—maternal traits being passed to offspring— maltreatment and poor health (145–148). These behaviors

including abuse-related phenotypes (132, 135). Inter- on their own increase risk for, and alter disease course in,

generational transmission of behavior is also implicated in mood disorders (149–153). More study on the relationship

humans. Yehuda et al. (136, 137) investigated risk for psy- between early-life adversity, substance use disorders, and

chopathology in offspring of Holocaust survivors. These mood disorders is therefore warranted. For example,

pivotal studies identified increased risk for PTSD, mood childhood maltreatment is associated with increased risky

disorders, and substance use disorders in offspring. These alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol use

offspring also reported having higher levels of emotional disorders (154, 155), and alcohol use disorders are an

abuse and neglect, which correlated with severity of PTSD in established risk factor for both depression and bipolar

the parent (136, 137), implicating early-life stress in trans- disorder (149–151) in addition to increasing risk for a more

mission of psychopathology. While there is evidence that severe clinical course, such as further increasing risk for

children with developmental disabilities are at a higher risk suicide (152, 153). A recent study reported that depression

for neglect (138–140), there is a paucity of studies in- mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment

vestigating whether offspring of individuals with mental and alcohol abuse (156). Another study recently reported

illness are more liable to abuse. However, as discussed above, that sexual abuse increased risk of alcohol use and de-

higher rates of maltreatment are reported in individuals with pression in adolescence, which then influenced risk for

mood disorders, but whether and what familial factors may adult depression, anxiety, and substance abuse (157). In a

drive these elevated rates, or whether these interactions longitudinal study investigating changes in patterns of

contribute to the intergenerational transmission of psycho- substance use over time in 937 adolescents, childhood

pathology, are not known. In light of the emerging data on maltreatment was associated with an increased progression

intergenerational transmission of trauma, this is an impor- toward heavy polysubstance use (158). More research is

tant, complex area in need of further study. There have not needed looking at the interactions between childhood

been many genetic studies in this area. In a study investigating maltreatment and other drugs of abuse. This is especially

early-life maltreatment in a rodent model, early-life abuse true in light of the current opioid epidemic, as increased

26 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020LIPPARD AND NEMEROFF

rates of childhood maltreatment are also reported in in- cognitive vulnerabilities, and behavioral difficulties as

dividuals with opioid use disorders (159–161), and greater modifiable predictors of depression following childhood

reported childhood maltreatment is associated with faster maltreatment. Specifically, social support and secure at-

transmission from use to dependence (162) and with higher tachments were reported to exert a buffering effect on risk for

rates of suicide attempts in this population (163). depression, brooding was suggested to be a cognitive marker

Interestingly, certain genes described above that exhibit of risk, and externalizing behavior was suggested to be a

gene–by–childhood maltreatment interactions on risk for behavioral marker of risk. Other researchers have also re-

mood disorders, including FKBP5 and the serotonin trans- ported that social support may be protective and that in-

porter promoter polymorphisms, also exhibit gene-by- terventions directed toward enhancing social support may

childhood maltreatment interactions on risk for alcohol decrease disease vulnerability and improve illness course

use disorders (164–168). Alterations in the stress hormone (179). Metacognitive beliefs, or beliefs about one’s own

system are also associated with an increased risk for alcohol cognition, are suggested to mediate the relationship between

use disorders in individuals with a history of childhood childhood maltreatment and mood-related and positive

maltreatment (169), and past-year negative life events have symptoms in individuals with psychotic or bipolar disor-

been reported to increase drinking and drug use, an effect that ders (180). Specifically, beliefs about thoughts being un-

is dependent on genetic variation in the serotonin transporter controllable or dangerous mediated the relationship between

gene (170). Childhood maltreatment has been found to be emotional abuse and depression or anxiety and positive

associated with an earlier age at initiation of alcohol and symptom subscale score on the Positive and Negative Syn-

marijuana use, with this association mediated by external- drome Scale. Affective lability was found to mediate the

izing behaviors (171). Impulsivity may mediate the re- relationship between childhood maltreatment and several

lationship between childhood maltreatment and increased clinical features in bipolar disorder, including suicide at-

risk for developing alcohol or cannabis abuse (172). Etain et al. tempts, anxiety, and mixed episodes (181), and social cogni-

(173) conducted a path analysis in 485 euthymic patients with tion was suggested to moderate the relationship between

bipolar disorder and uncovered a significant association physical abuse and clinical outcome in an inpatient psychi-

between impulsivity and emotional abuse, and impulsivity atric rehabilitation program (182).

was associated with an increased risk for substance use

disorders. These studies suggest that in some individuals with Childhood Maltreatment and Associated Alterations in

a history of childhood maltreatment, although not all, in- Neural Structure and Function

terventions that focus on alcohol or drug use problems, and Research on neurobiological consequences that may me-

specifically externalizing behaviors that may mediate the link diate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and

between childhood maltreatment and alcohol or drug use risk for, and affect disease course in, mood disorders is

problems (e.g., impulsivity), could decrease disease burden clearly integral to addressing the question of whether the

by decreasing risk for developing mood disorders or by consequences of early-life stress are reversible. Although a

improving illness course (e.g., decreasing symptom severity comprehensive review of neuroimaging findings is beyond

and risk for suicide). the scope of this review, over the past 5 years, review articles

Substance use disorders are also associated with increases summarizing the neurobiological associations with child-

in inflammatory markers (174, 175). Inflammation is sug- hood maltreatment have emphasized the long-lasting

gested to contribute to comorbid alcohol use disorders and neurobiological structural and functional changes in the

mood disorders (176), and it contributes to a variety of brain following maltreatment (21, 83, 183, 184). In brief,

medical morbidities (177), and these in turn are associated while null and conflicting findings have been reported, data

with an increased risk for mood disorders (177). Speculatively, are converging to suggest that childhood maltreatment is

inflammation may be one mechanism by which childhood associated with lower gray matter volumes and thickness in

maltreatment increases risk for medical morbidity and the ventral and dorsal prefrontal cortex, including the

through that pathway increases risk for mood disorders. orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices, hippocampus,

While there is a paucity of studies on the pathways described insula, and striatum, with more recent studies also sug-

above, the associations between childhood maltreatment, gesting an association with decreased white matter structural

risky health behaviors, inflammation, and medical morbid- integrity within and between these regions (185–194).

ities warrant more study, as identifying pathways (mediators Smaller hippocampal and prefrontal cortical volumes fol-

and moderators) to illness outcomes could foster the de- lowing childhood maltreatment are consistently reported in

velopment of more effective interventions and treatment unipolar depression and other psychiatric disorders (189,

strategies. 195–199), with gene-by-environment interactions suggested

It should be noted that not all individuals who experience (200–202). These studies suggest mechanisms that may

childhood maltreatment develop mood disorders. This may cross diagnostic boundaries in conferring risk for psycho-

be related in part to genetics. However, other resiliency pathology and genetic variation that may link neurobiology,

factors are likely of importance. In a recent meta-analysis, childhood maltreatment, and vulnerability for detrimental

Braithwaite et al. (178) identified interpersonal relationships, outcomes.

Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 27CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES OF CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT

Studies investigating differences in function within, and childhood maltreatment and relapse of depression among

functional connectivity between, these regions following 110 patients with unipolar depression followed prospectively.

childhood maltreatment are emerging, with more recent A longitudinal study incorporating structural MRI in 51

results suggesting that these changes may relate to risk for adolescents (37% of whom had a history of childhood mal-

psychopathology. It was recently reported that decreased treatment) found that reduced cortical thickness in pre-

prefrontal responses during a verbal working memory task frontal and temporal cortices was associated with psychiatric

mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment symptoms at follow-up (210). Swartz et al. (211) followed

and trait impulsivity in young adult women (203). In a study 157 adolescents over a 2-year period and reported results

investigating functional responses to emotional faces in suggesting that early-life stress is associated with amygdala

182 adults with a range of anxiety symptoms (204), the au- hyperactivity during threat processing, with this finding

thors found that increased amygdala and decreased dorso- preceding syndromal mood or anxiety. Longitudinal study of

lateral prefrontal activity to fearful and angry faces—as well as outcomes following childhood maltreatment and underlying

increased insula activity to fearful and increased ventral but neurobiology (predictors and trajectories) is critically needed

decreased dorsal and anterior cingulate activity to angry to identify modifiable targets that confer risk and disentangle

faces—mediated the relationship between childhood mal- mechanisms of risk and resilience.

treatment and anxiety symptoms. Differences in functional Only recently have studies investigating childhood mal-

connectivity, measured with multivariate network-based treatment in bipolar disorder and neurobiological associa-

approaches, within the dorsal attention network and be- tions begun to emerge. Similar to unipolar depression and

tween task-positive networks and sensory systems have been other psychiatric disorders, decreased ventral and dorso-

reported in unipolar depression following childhood mal- lateral prefrontal, insula, and hippocampal gray matter vol-

treatment (205). Altered reward-related functional connec- ume are reported in individuals with bipolar disorder with a

tivity between the striatum and the medial prefrontal cortex history of childhood maltreatment compared with individ-

has also been reported in individuals with greater recent uals with bipolar disorder without childhood maltreatment

life stress and higher levels of childhood maltreatment, (202, 212, 213). Decreased white matter structural integrity

with increased connectivity associated with greater depres- across the whole brain, including lower structural integrity

sive symptom severity (206). Childhood maltreatment– in the corpus callosum and uncinate fasciculus, have been

associated changes in functional connectivity between the reported in individuals with bipolar disorder who reported

amygdala and the dorsolateral and rostral prefrontal cortex having experienced child abuse compared with those who did

have been suggested to contribute to altered stress response not and a healthy comparison group (214, 215). Interestingly,

and mood in adults (207). Additionally, childhood mal- one study (214) found that the effects of childhood mal-

treatment has been reported to moderate the association treatment on white matter structural integrity were specific

between inhibitory control, measured with a Stroop color- to individuals with bipolar disorder; decreased structural

word task, and activation in the anterior cingulate cortex integrity was not observed in healthy comparison individuals

while listening to personalized stress cues, an individual’s with a history of childhood maltreatment compared with

recounting of his or her own stressful events (208). As dis- healthy individuals without maltreatment. In light of this

cussed above, it has been hypothesized that childhood finding, along with recently published data from other groups

maltreatment may increase risk for mood disorders through (216–218), it is possible that some consequences following

alterations of the HPA axis and CRF circuits in the brain. childhood maltreatment may be more robust or distinct in

Therefore, research aimed at identifying neurobiological some individuals—or that perhaps individuals with a genetic

changes in function of CRF circuits in the brain that may predisposition for mood disorders may be more vulnerable

mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment to the detrimental effects of childhood maltreatment.

and risk for mood disorders and affect disease course, in- Altered amygdala and hippocampal volumes are suggested

cluding interactions with recent life stress, is a promising area to be differentially modulated following childhood mal-

of investigation. treatment in patients with bipolar disorder compared with a

Recent studies investigating altered function could sug- healthy comparison group (216), although interactions with

gest neurobiological mechanisms of risk but may also suggest history of treatment (e.g., duration of lithium exposure)

possible mechanisms underlying resilience (183). Functional cannot be ruled out, as this was not investigated. Souza-

studies, such as those discussed above, that link functional Queiroz et al. (217) found that childhood maltreatment was

changes in the brain following childhood maltreatment to associated with decreased amygdala volume, decreased

mood-related symptoms can provide some clues to help ventromedial prefrontal connectivity with the amygdala and

identify mechanisms underlying risk. However, in the ab- hippocampus, and decreased structural integrity in the un-

sence of longitudinal study of outcomes, these results must cinate fasciculus—the main white matter fiber tract con-

still be interpreted with caution. While the majority of studies necting these regions. The bipolar group primarily drove

have been cross-sectional, longitudinal studies are beginning these effects, with only smaller amygdala volume associated

to emerge. Opel et al. (209) recently reported that reduced with childhood maltreatment in the healthy comparison

insula surface area mediated the association between group. While these findings could be driven by higher rates of

28 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020LIPPARD AND NEMEROFF

maltreatment reported in the bipolar disorder group, or other that may drive development of mood disorders following

clinical factors such as medication exposure and history of childhood maltreatment. A promising area is network-based

depressed or manic episodes, they could also suggest inter- approaches to understand this link (224). Additionally,

actions between genetic vulnerability to bipolar disorder (or consequences following different types of maltreatment re-

other environmental factors) and neurobiological conse- quire further investigation, as different forms of childhood

quences following childhood maltreatment. maltreatment may be associated with distinct neural con-

More research is needed to identify genes that may in- sequences, and a better understanding of these relations is

fluence neurobiological vulnerability following childhood critical for the development of more effective interventions

maltreatment. An example of a potential gene that may and prevention strategies. For example, Heim et al. (225)

mediate this relationship is the serotonin transporter pro- reported that victims of sexual abuse exhibit more alterations

moter. Genetic variation in the serotonin transporter pro- in the somatosensory area, whereas victims of emotional

moter is associated with differences in structural integrity abuse exhibit differences in areas mediating emotional

of white matter in bipolar disorder (219). Because a large processing and self-awareness, including the anterior cin-

number of studies support the interaction between early-life gulate and parahippocampal gyrus. More work is needed to

stress, the serotonin transporter promoter, and disease vul- investigate whether there are sensitive periods in develop-

nerability and illness course in depression and bipolar dis- ment when maltreatment has more robust consequences on

order (106–111), this example highlights the potential of genes neurobiology. Humphreys et al. (226) recently reported that

to contribute to long-lasting structural consequences in the hippocampal volume differences were associated with stress

brain following childhood maltreatment in mood disorders. severity during early childhood (#5 years of age), but there

Genetic imaging studies are emerging and suggest gene-by- was no association between hippocampal volumes and stress

environment interactions on structural and functional al- occurring during later childhood. Studies investigating in-

terations following childhood maltreatment. For example, teractions between childhood maltreatment and genetic

one study found that hippocampal volume differences fol- variation or familial risk for mood disorders could identify

lowing childhood maltreatment are mediated by genetic mechanisms underlying risk and resiliency in the absence of

variation in bipolar disorder (202). Additionally, polymor- some study-related confounders (e.g., medication).

phisms in stress system genes, including FKBP5 and NR3C1, Longitudinal studies are critically needed to distinguish

are suggested to moderate the effects of childhood mal- what behaviors and mechanisms (genetic and neurobiolog-

treatment on amygdala reactivity (220–222) and hippo- ical) may contribute to risk and whether alterations in be-

campal volumes (223). Studies investigating interactions haviors or neurobiology are secondary to mood disorder

between familial risk for mood disorders and childhood onset. It is important to emphasize that sex differences likely

maltreatment and associated structural and functional contribute to outcomes following childhood maltreatment

changes in the brain would be useful to test whether familial (227). These include females, compared with males, having

factors (genetic and environmental vulnerability) may in- a higher risk for internalizing disorders (depression and

teract with childhood maltreatment to alter brain structure anxiety) (228, 229), greater deficits in neural systems un-

and function while avoiding confounders such as medication derlying emotional regulation (187, 230), and being more

exposure. susceptible to stress-induced changes in the HPA axis (231)

following maltreatment. Males, compared with females, may

be more vulnerable to developing externalizing disorders

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

(conduct disorders and substance use disorders) (232).

A sizable percentage of patients with mood disorders have a However, few studies have investigated sex differences fol-

history of childhood maltreatment. While the devastating lowing childhood maltreatment. More research on sex dif-

consequences of childhood maltreatment cannot be dis- ferences is critically needed, including on the underlying

avowed, several limitations in research should be noted. neurobiology. As previously reviewed (21), early-life adver-

Research groups often assess childhood maltreatment dif- sity is associated with increased vulnerability to several major

ferently, and this can result in a measurement bias. De- medical disorders, including coronary artery disease and

mographic characteristics and differences in assessments myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease and stroke,

(age and sex ratio of participants; clinical versus nonclinical type 2 diabetes, asthma, and certain forms of cancer. More

populations being studied; observer-rated versus self-rated work is needed on medical morbidities that may increase risk

depression measures) are all suggested to contribute to dif- for early mortality following early-life adversity. Additionally,

ferences in prevalence of childhood maltreatment and re- more research is needed on disparities that contribute to, and

lation with illness severity (12). For example, studies using minority communities that show, elevated rates of early-life

the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire report higher rates of adversity. As discussed above, rates of early-life adversity are

emotional abuse compared with studies using other measures higher among individuals with developmental disabilities

to investigate childhood maltreatment (12). Further study is (138–140). Rates of trauma are also higher in youths in the

warranted investigating the neurobiological mechanisms, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ)

underlying genetics, familial factors, and modifiable targets community (233). Few studies have been published in this

Am J Psychiatry 177:1, January 2020 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 29You can also read