Software Engineering, an established Accreditable Engineering Discipline

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Software Engineering, an established

Accreditable Engineering Discipline

By B.Szabados, P.Eng,

McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. (member of CEAB)

Note: The content of this paper has been presented at a workshop of the Canadian

Engineering Accreditation Board (CEAB), as well as at a workshop at the

NCDEAS meeting in September 1997.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the late seventies, the discipline of Computer Engineering has evolved from Electrical

Engineering. The main emphasis was on the hardware aspects of logic design and computers,

principally microprocessors. The natural evolution of a discipline following the needs of industry

led some University programs to the introduction of an option “Computer Engineering”, in the

last year of an accredited Electrical Engineering program. The next natural evolution was a stand

alone Computer Engineering CEAB accredited program (first in 1983 at McMaster University).

It has to be noted that the “definition” of Computer Engineering was at most fuzzy at the time,

and even today it is difficult to give a narrow definition of it.

Software Engineering is a term that has been with us as far back as the sixties. We will not

enter the debate on definition. However one fact remains that the discipline of software

engineering is an industrial reality, dictated by the practice and needs in today’s society. The

main problem dealing with the Software Engineering concept is that the need, practice and

evolution in multiple branches has taken place without the participation of the University

curricula or professional regulatory bodies. To make things even more complex, other

professionals such as technologists and computer scientists, have put forth claims towards

practising “Software Engineering”. Again the aim of this presentation is not to enter the legal

debate.It is proposed here to illustrate that “Software Engineering” is clearly a strong discipline

of Engineering, on its own merits and that a program is accreditable.p.2

2- MISSION

Instead of dwelling with definitions related to “Software Engineering”, let us postulate the

mission of a Software Engineer as perceived in today’s society:

“The software engineer specializes in designing, building, upgrading, operating and

maintaining software systems. He must ensure the security, safety, reliability, user

friendliness and cost effectiveness (quality attributes) of these software systems, that are

important for the economy and well being of the public.”

This mission statement implies that the expectations of a Professional Engineer fully apply,

namely: a role of mentorship is expected; and a certain philosophy pertains to the education of an

engineer.

The software engineer is first and above all an engineer. Similarly to other engineers, he has

a specialization defined above in general terms, but always pertains to his professional

responsibility with respect to society. It must be understood that there are many secondary

specialization areas in a discipline. Diversities will be expected within the discipline of Software

Engineering.

The common root of an engineering education is composed of a careful selection of relevant

content of Mathematics, Basic Sciences, Complementary studies, Engineering Design and

Engineering Sciences. The engineering education in the topics of sciences, is the application of

the knowledge generated by those sciences, and not generally the derivation of this knowledge.

Therefore the discipline of Computer Sciences will play a key role in the education of the

software engineer. But this role will not be different from the role of Basic Sciences for example.

It may only mean that more material will be derived from the knowledge generated by the science

of computer sciences. This is similar to Chemistry which will play a larger part in the background

of a Chemical Engineer than an Electrical Engineer for example.

The program specific criteria of software engineers could be defined in the methodologies

for analysis, test, monitoring, validation and interfacing software products. The software engineer

is expected to assume responsibility accountability and liability for the product developed.

3- GOALS

Within the above mission statement, the software engineer will be asked to develop software

as a product. This may de designed to control electromechanical devices, coordinate safe start or

shut down sequences, operate computerized communication systems, manage information

infrastructures, produce computer systems used to design other engineering products or services,

and many other applications. This typical list is only quoted to illustrate the diversity of

secondary specialization that exists in the discipline today, similarly to other engineering

disciplines requiring a very large scope of knowledge.

However a common requirement for all software engineers is the need to learn a disciplined

methodology to specify, design, document, develop, produce, test, integrate, assess, analyze,

monitor, upgrade and market software systems which are able to perform their assigned tasks.

This is certainly not a mere programming exercise.p.3

It would be worth at this point to illustrate the place of the software engineer within the

general technology requirements of the “computer world”. There are typically 3 spheres of

activities. The application development of non technical programs (word processors), or general

use tools (graphical aids) do not need the constraints of the engineering responsibility. Non

engineers, either programmers with a “good idea” or more educated computer science personnel

could attend to those applications, since programming is only a “packaging” exercise.

A second area addresses applications where the computers, or its elements, or system

components are interfaced to the user. In these applications, the art becomes an engineering

exercise, with professional responsibility culminating. This is definitely the realm of the

Computer Engineer, who needs the appropriate skills in general engineering, electrical

engineering and some elements of software development, to arrive at an appropriate design. This

area involves Engineering Design, which is the identity of the engineering education.

The third area addresses a complex multidisciplinary area of computer systems, team

development, maintenance and management activities. Because of the applications which are

multidisciplinary, the software engineer is not expected to be a specialist in all areas touching the

development. He becomes the common denominator in the multidiciplinary team, not because he

knows the details, but because he knows the design methodology. In his team he will coordinate

experts (mathematicians, computer scientists, material scientists etc...) who construct the

algorithmic requirements, but he will direct the design of the overall project from a technical

point of view. He should be responsible to assure that documentation is properly done

(specification and operating conditions, code, testing, maintenable). He should have an overall

assessement that the hardware configuration proposed is appropriate to the task. He must ensure

that programs terminate when and how intended, and that the system meets the real time

constraints and other performance requirements such as reliability, fault tolerance and

redundancies.

In summary a typical skill profile of the software engineer should include the following:

- Analysis of the application to derive technical requirements of a computer system

- Recording of those requirements in a precise, organized document that can be reviewed

by specialist engineers and become the basis for specification design, review and testing.

- Design of the computer system configuration with function implementation in hardware/

software, selection of hardware/software components.

- Performance analysis using analitical tools or simulation to assure that the proposed

equipment or system meets the requirements.

- Design the structure of the software in modules, interfaces and hierarchical structures.

- Document the software component interfaces

- Analyze the software structures for completeness, consistency and suitability.

- Implement the software with in-line documentation.

- Systematic and statistical testing of the system and software.

Armed with the mission statement, the goals and the skill expectations, we can now proceed

with the identification of an appropriate curriculum.p.4

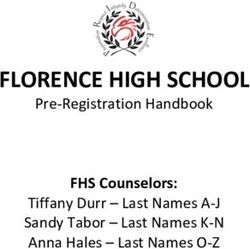

4- TABULAR ANALYSIS OF CURRICULUM TOPICS

Instead of taking an existing engieering curriculum, for example a computer engineer

program, and add a solid software component, like most Universities do at the moment, we

decided to design a stand alone Software Engineering curriculum based on the real needs as

defined above.

A list of major topics was drawn up without any premeditated order or outcome (Table I).

Each subject was entered in a table, and a rating was applied for each of the four disciplines:

Electrical Engineering (EE), Computer Engineering (CE), Software Engineering (SE) and

Computer Science (CS). The rating was quantized as follows: (F)=fundamental for the discipline;

(C)=core; (EL)= elective; ()= not an outstanding requirement. “Fundamental” means that no

program can be conceived without these topics. “Core” means that it is strongly expected to

cover these topics, however, some specialization in the general discipline may chose not to

include it. “Elective” means that it is desirable to have a knowledge of, or have a specialization if

so chosen. It is also to be noted that the qualifiers relate only to the topic as being applied to the

discipline, and not to the “engineering education”.

It is imperative at that stage to understand that the judgement applied was essentially

subjective of what was understood by the titles. No attempt was made to define the quality nor

the depth of the topic. But also it is imperative to understand that no differentiation was made in

the flavor and emphasis in the topics. For instance in the topic “Operating Systems”, both SE and

CS are rated (F). However it is obvious that a course called Operating Systems will be very

different when tailored to SE or CS. Computer Systems students will be interested in conceiving

operating system principles, and dwell on theoretical models of implementations. Software

Engineering students will require to use operating systems, therefore they have to know how they

work, how they perform, and most of all how they compare to each other. But in this first stage of

planning no such differentiation was made.

Using a specially designed algorithm, the matrix was sorted to show groups of topics

illustrated by similar ratings. It is interesting to observe that classes appear as shown by Table II.

The first class, ‘EE/CE major’ constitutes a basis common to both EE and CE. It is interesting to

observe that SE will also have these topics either as (F) or (C) rating, while CS has only (C) or

(EL) or (none) ratings. It is clear to the designer that these topics are clearly a common

engineering basis to the curriculum.

The second class ‘SE majors’ having essentially (F)’s and (C)’s, and shows their neigbours

with a decreased emphasis. Again some topics show, for instance “Computer Architecture”, to be

a topic that is fundamental to CE as well, but at a different level of emphasis much more hadware

oriented.

The ‘CS majors’ stands out in the fields of mathematics and operating systems, which are

knowledge generated by computer science, and is used as major tools by the software engineer.

The ‘EE/CE flavour’ shows clearly that CE has been derived from EE, and that some of that

knowledge is also used by software engineers, but mainly on a specialization level, rather than a

deep underlying basics level.

The next two classes are less distinct, and are labelled ‘SE flavour’ and ‘CS flavour’ wherep.5

the topics are essentially reserved for these two disciplines. Here the topics differ in delivery and

emphasis and depth of the subject between the disciplines.

An extra class, Engineering topics, highlight the general culture that is common to EE, CE

and SE, and is definitely not present in CS.

The list shown in Table I is by no means exhaustive. We have dropped topics which were

“regional”, that is pertinent to some existing programs of specialization (for example VLSI),

because we did not feel that it enters a class of “universal measure”.

5- DERIVATION OF A CURRICULUM TEMPLATE

Based upon the analysis of Table II, we have derived constraints for a template curriculum.

All courses in this template are based on a 3 credit basis which represents on average 40

accreditation units as defined by the CEAB.

Six courses in Mathematics clearly are identified in the tables. Namely: Calculus; Linear

Algebra; Differential Equations; Logic; Mathematical Foundations and Discrete Mathematics;

Probabilities and Statistics. It is to be noted here that this differs somewhat from the “standard

EE” curriculum requirements in Mathematics. Usually neither Logic nor Discrete Mathematics

are covered in conventional EE programs. This already points out that SE students have

somewhat different requirements from EE/CE students (2 out of 6 courses different).

In Basic Sciences, we have identified 5 courses: Chemistry; Mechanics and Stress Analysis;

Electromagnetic Waves; Thermodynamics and Heat Exchange; Structures and Properties of

Materials. Because each software engineering program will have an “institution flavour” reflected

by the philosophy, resources available and regional needs we have allocated one extra Basic

Sciences course as an ELECTIVE SCIENCES topic in the spirit of the CEAB classification

(Biology Astronomy, etc...). The reasoning behind these 6 courses comes from the mission

statement of the software engineer. He will have to lead a multidisciplinary team, therefore he

should have a solid basic science background to at least be able to communicate with the experts

in each of the fields.

Three courses in complementary studies must cover: Technology and Society;

Communications Skills and Professionalism (including law and ethics as well as Health and

Safety issues); Economics for engineers. These are basic requirements for all engineers, reflecting

their professional responsabilities to society. Three other complementary studies courses should

be scheduled to acquire the humanities and social sciences and thought processes of humanities

that are advocated by the CEAB requirements.

A major design experience consisting in a formal design project must be included. This

design experience should stress the team environment and foster leadership development. It is

imperative that such project does not mearly produce a software program, but englobes all of the

steps of the software design experience, namely - Specification - Implementation, -

Documentation - Testing - Interpersonal skills and interface activites should be encouraged

In order to evaluate the accreditation criteria of the engineering courses, accreditation units

are associated according to the CEAB classifications of Engineering Sciences (ES=%) and

Engineering Design (ED=%) expressed in pecentages and are done based on a conservativep.6

measure. For several courses the estimated coefficient ratings are based not just on possible

content, but also on the ability to use resources on who can teach engineering design. For instance

the course “Theory of Programming languages and Language selection” might very well contain

some engineering design, but since it is assumed that a non registered professional will teach it

most likely, a 100% Engineering Science component is assumed. In this table we do assume that

the CEAB requirements of registered professionals should teach all engineering design and

engineering sciences will be somewhat relaxed, at least until accredited software engineers

become available, and permit some of the engineering science to be tought by non engineers. We

do however strictly enforce the engineering design component to be taught be registered

engineers.

From the EE classes, we propose to introduce courses that reflect the needs for software

engineers to understand the basics of the hardware and the concepts of control and electrical

signals they will be expected to deal with. Namely the 4 courses proposed are: Circuits and

Instrumentation, [ES=100%]; Introduction to Electronics, [ES=80% ED=20%]; Introduction to

Control Theories, [ES=80% ED=20%]; Elements of Telecommunications, [ES=80% ED=20%].

Finally from the CE class we have extracted 6 basic courses. Two of them would be

common requirements to the CE and SE students, essential basic tools: Numerical Methods

[ES=100%]; Data Structures, [ES=100%]. Three courses essentially belonging to CE are: Digital

System Design (providing the fundamentals of microprocessors), [ES=50% ED=50%]; Computer

Architecture (advanced systems with multiprocessor and parallel processors), [ES=40%

ED=60%]; Computer Communication Networks (related to physical media, routing, protocols,

[ES=56% ED=40%]; and Simulation and Modeling [ES=60% ED=40%], left in the CE category

rather than the EE common core, because for a software engineer the emphasis would be on

discrete modelling and simulation, while EE would lean towards continous models.

Table II shows also ‘CS flavour’ required courses as follows: Fundamentals of Computer

sciences, [ES=100%]; Theory of Programming languages and Language selection [ES=100%];

Compilers, [ES=100%]; Automata, [ES=100%]; Data Base, [ES=100%].

Based on Table II, there are 6 more courses which reflect needs in an SE core program.

These could be: Introduction to low level programming (year 1) [no CEAB weighting]; Design of

Software Systems [ES=40% ED=60%]; Advanced Design of Software Systems, [ES=20%

ED=80%]; Design of Concurrent and Real Time Software, [ES=30% ED=70%]; Operating

Systems, [ES=80% ED=20%]; Data Management techniques, [ES=20% ED=80%].

Based upon a 4 year (8 term program) with 6 courses per term this leaves 8 more courses

that can be used towards a secondary specialization (options), or special regional flavours

(program enhancements). Some topics could include the following topics: Performance analysis

of computer systems [ES=20% ED=80%]; Optimization methods [ES=20% ED=80%]; Design

and Evaluation of Operating Systems [ES=20% ED=80%]; Design of Human Interfaces

[ES=40% ED=60%]; Evaluation and Selection and Design of CAD tools [ES=40% ED=60%];

Intelligent Manufacturing Systems and Process control [ES=40% ED=60%]; Image processing

[ES=40% ED=60%]; Geographic Information Systems [ES=40% ED=60%]; Computer security

[ES=40% ED=60%]; DSP [ES=40% ED=60%]; Business Applications of Computers [ES=40%

ED=60%]; Information retreival [ES=40% ED=60%]; Computational geometry [ES=40%

ED=60%]; interdisciplinary topics in Civil, Mechanical, Chemical etc..p.7

The program template is summarized here:

- 6 Mathematics courses

- 6 Basic Sciences courses

- 3 complementary (communication; Technology and Society; Health and Safety;

Economy)

- 3 Humanities and Social Sciences

- 1 Capstone Engineering Design

- 4 Electrical Engineering

- 6 Computer Engineering

- 5 Computer Sciences (service courses)

- 6 software engineering courses

- 6 compulsory SE courses from a list similar to that given above

- 2 technical electives from EE, CE, CS or other Engineering disciplines

According to the distribution of AU’s in the SE compulsory/elective list, we could assume

conservatively that the 6 compulsory courses would have at least 2 courses with the [20-80]

distribution, and 4 courses with [40-60] distributions. The remainder of the 2 technical electives

would register no AU’s according to a pessimistic scenario of minimum path rule. A preliminary

very pessimistic CEAB evaluation would show the following scores:

Total of 48 courses at 40 AU/c (not counting labs and tutorials) 1920 AU (*1800)

Maths: 6 courses 240 AU (*195)

Basic Sciences: 6 courses 240 AU (*225)

Complementary Studies: 6 courses 240 AU (*225)

ES ED ES+ED

Core: 580 AU 264 AU 844 AU

Compulsory: 2 courses with [20-80] 16 AU 64 AU 80 AU

4 courses with [40-60] 64 AU 96 AU 160 AU

_______ _______ ______

Totals: 660 AU 424 AU 1084 AU

(*225) (*225) (*900)

All of these coefficients are well within the CEAB minimum requirements as shown in

bracket with a star. They are pessimistic numbers since no laboratory nor tutorial has been

counted. It is to be noticed that at least 12 courses are specifically Software Engineering

discipline courses, or 1 year out of the 4 year curriculum. This confirms that the program is very

distinct from any of the other engineering disciplines.

6- DISCUSSION ON SCHEDULING AND RESOURCES

Generally engineering programs are structured to introduce material in early levels in order

to feed the more specialized courses in the disciplines. With software engineering, it is important

to recognize that, although programming is not the main goal of the program, it is a very

important tool. Furthermore, similarily to Mathematics as a tool, students have been introduced top.8

the process of thought of mathematics, and through high schools have already acquired some

working knowledge and practice through exercises. The problem with software is, that students

arrive from high schools with a false impression of knowledge. “Computer courses” covered how

to use word perfect, or how to surf the net, and most students are computer game aces. It takes

considerable effort to make them understand what software development really is. The program

should therefore be scheduled in such a way that students not only receive introduction to

programming (generally common to all engineering students) and fundamentals of computer

sciences, but also as soon as feasible, start the systematic software development process, and

provide them with practical ways to write examples. Wheras courses such as Electric Circuits,

which is the basic tools for electrical engineering, is now a “complement” to the knowledge of

the software engineer, and therefore can be given later as scheduling permits.

The streaming of the material attempts to put it in a 6 course per term sequenced package. It

can be a frustrating experience because the engineers planning the material delivery do not yet

have the experience of the best “acceptable” way to sequence software education.

The design method suggested here, is to write up clear objectives for each course, as a stand

alone exercise, not worrying about its scheduling. It is helpful though to derive progressive

objectives in a sequence of courses, for instance in the software development area. This would

ensure that all the important material is covered. As an example (and this is by no means to be

taken as necessarily the right way!) a sequence of 3 courses after the introduction to programming

can include the following objectives:

Course 1: “Given the problem specifications, students will be able to design, implement

and document the modular layout of the program.”

Course 2: “The students will be able to derive the program specifications from a set of

engineering description, and should be able to design, implement and document

the program.”

Course 3: “The students should be able to design, implement, document a given physical

problem, and be able to test for comformity, completeness, and performance, as

well as plan for maintenance and upgrade documentation”.

From the objectives above, one can see that many techniques, analysis tools and basic

computer sciences derived knowledge have to be covered before a student can achieve these.

In a second phase, the curriculum design should proceed with a detailed outline of material

on a course by course basis, in order to achieve the objectives. At this level it is important to

conduct a parallel exercise. While listing the topics in the course, a list of associated topics which

are assumed to be known is drawn up. This will constitute the criteria of co or pre requisits for the

streaming.

Based on the course content as well as pre requisit knowledge, a first streaming of courses is

attempted. Careful examination of the layout will always cause a few loops in the design.

Material which is prerequisit may have to be lumped in the course and some material shifted out.

Care should be taken that all co or pre-requisit topics will be covered, and not simply left to the

whim of the instructor to cover when he discovers that students have no idea of what he talks

about... This is by far the most time consuming exercise of the curriculum development, and it is

suggested that all future faculty teaching the courses be involved and give a solid feedback to thep.9

development committee.

It is the experience of the author, that invariably this exercise leads to “too much material”

to be crammed in a 4 year curriculum. The third phase of the development addresses now the

loading of the student, as well as the evaluation of material assimilated which goes in line with

the level of maturity of students at time of delivery. Certain concepts cannot be covered unless

students become mature and have acquired a solid working skill background, say in data

structures. This phase attempts to put contact hours, student work loading or other numerical

weighting to each topic in the course content. This usually will result in shifting emphasis or

depth within a course. It may also dictate to redistribute the topic in increasing levels of

difficulties in subscequent courses. It is necessary at that point to define tutorials and laboratory

content associated in great detail. It is not sufficient to state that 3 hours of laboratory will be

taking place every second week. The objectives and detailed content of the laboratories must be

defined and integrated either to illustrate the lecture, or introduce new concepts not covered in the

lecture.

This should lead to a layout which satisfies the curriculum content and delivery sequence.

For new programs, and software engineering certainly qualifies, a problem of teaching resources

immediately come to mind.

Identification of the potential knowledge base within existing faculty members in Electrical,

Computer Engineering and Computer Sciences units is usually fairly simple. It is advised to

survey also the other disciplines. For instance Chemical engineers who do process control, or

manufacturing engineers, usually have a pool of knowledge well within the software engineering

program needs. These individuals may need to rework some of their knowledge and shift

emphasis in the methods of presentation of material. They have to be willing to “recycle”.

Computer Science faculty members may also be asked to focus on different topics when teaching

engineers, and this means a concerted effort to prepare for this new way of thinking software

development.

Nevertheless, the pool of knowledge usually reveals that most faculties have already the

knowledge base to cover most of the topics in software engineering. Some existing courses in

engineering may differ in emphasis to the ideal presentations to software engineers. But for start

up programs, there might be a compromise reached, which permits implementation of a “decent”

program without unduly creating a flock of new courses, and drive the administration out of their

mind when a faculty requests 12 new faculty members at once! However it has to be recognized

that the introduction of at least 12 courses proper to software engineering, will require at least 6

new faculty positions. It is important to notice that, because of the competition with industry in

this area, it would be a dream to hire 6 software engineers. But bear in mind that if the existing

faculty complement in the University has the knowledge base, then new faculty could be hired in

the conventional areas to offload faculty who will participate now in the new software program. It

is also to be noted that these 6 positions are not needed at once. The 12 new courses are usually

distributed over at least 3 years. The exercise now is to convince the administartion to have an

expansion plan covering 3 years, with probably 3 new faculty in the first year, and then 3 more in

the next 2 years. This sounds less scary to today’s administrators tackling difficult budgets.

7- CONCLUSIONS

Software Engineering, unlike other engineering disciplines, has developed in the past 15p.10

years directly in user groups. Because it was commonly associated as an “add on tool” to other

established disciplines, the Educational institutions have failed to adapt to the needs of industry,

by providing distinct educational curricula. We are facing a fairly mature discipline without the

infrastructure of an adequate educational process.

In this presentation, a mission statement and clear goals are proposed, leading to the

expectations of a professional engineer as applied to Software Engineers. It is shown that these

expectations are exactly the same as for any established discipline: responsibility, accountability

and liability. The Software Engineer must learn a disciplined methodology based on engineering

design, which is proper to the discipline. The Software Engineer is a Professional Engineer with

all the strings and advantages attached.

A set of typical skills profile was attempted, followed by a systematic analysis of scientific,

mathematics and engineering topics that are presently taught in various institutions in programs

such as Electrical or Computer Engineering and Computer Sciences. An original matrix analysis

shows clearly that although aside from the attributes with other accredited programs, there are

courses required to convey the knowledge base from conventional disciplines: Mathematics,

Basic Sciences and Computer Sciences. Some course content can be taken from introductory

Electrical curricula, and obviously some overlap will exist with Computer Engineering curricula

especially for the hardware parts. But it has been shown that at least 12 courses, which represents

one full year over a total of 4 years, are specialized software courses. This should make it clear

that Software Engineering is a distinct discipline, clearly different from Computer Engineering as

well as Computer Sciences.

Finally a template curriculum is proposed, showing that such a program meets all the

requirements of the Canadian Engineering Accreditation Board criteria. The template illustrates

that there is plenty of room to satisfy the various course content requirements of the CEAB, and

still have manouvering space to accomodate various options, specializations, and electives. This

is very important since every University will have to carve out an identity for its program, based

on current knowledge expertise, regional demands, and institutional goals.

8- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Acknowledgements are due to the McMaster University team of curriculum development,

the software curriculum development group, and the special task force. A special mention is

made to Dr David Parnas, P.Eng, Bell Chair in Software Engineering at McMaster University, for

the many brain storming sessions and original ideas he brought into the project. Mention is due to

Dr Mohan Mathur for his constructive assistance in the presentation of the key problems.p.11

Comparisons of EE / CE / SE / CS curricula contents

F=Fundamental > C= CORE > EL=elective

subject EE CE SE CS

1 Design experience F F F

2 Math: Calculus F F C C

3 Math: D.I.F. F F C EL

4 Math: Linear Algebra F F C EL

5 Circuits F F C

6 Control Systems F C C

7 EM fields F C EL

8 Electronics (analog) F C EL

9 Computer architecture C F F C

10 Electronics (digital) C F EL

11 Numerical Methods/computing C C F F

12 Computer Programming C C F C

13 Simulation & Modeling C C F C

14 Math: Stats C C C EL

15 Optimization methods C C C EL

16 Chemistry (intro) C C C

17 Stress Analysis Concepts C C C

18 Structure & Properties of Materials C C C

19 Thermodynamics concepts C C C

20 Heat Exchange concepts C C C

21 Mechanics concepts C C C

22 Signal Processing C C EL

23 A&D Communication C EL

24 Math: Discrete EL F F F

25 Data Structures EL C F F

26 O.S. EL C F F

27 Software Design EL C F C

28 Specification, Quality & Testing Software EL C F EL

29 Protocols (nets) EL C C EL

30 Computers in Communication Systems EL EL C

31 Theory of programming languages C F F

32 Concurrency & Assynchronous Comm. EL F C

33 Compilers EL C F

34 Automata EL C F

35 Languages EL C F

36 Data Base EL C C

37 Information Retreival EL C EL

38 Computer Security EL C EL

39 Embedded Systems EL C EL

40 Design of Human Interfaces EL C EL

41 Design and Evaluation of Software Systems EL C EL

42 Data Management techniques EL C

43 Math: Abstract F F

44 Business Mathematics EL

TABLE I: Raw Data Analysisp.12 Comparisons of EE / CE / SE / CS curricula contents (F=Fundamental > C= CORE > EL=elective) subject EE CE SE CS EE,CE majors Design experience F F F Math: Calculus F F C C Math: Linear Algebra F F C EL Math: D.I.F. F F C EL Circuits F F C SE majors Computer architecture C F F C Simulation & Modeling C C F C Computer Programming C C F C Specification, Quality & Testing Software EL C F EL Software Design EL C F C Concurrency & Assynchronous Comm. EL F C Design of Human Interfaces EL C EL Design and Evaluation of Software Systems EL C EL Embedded Systems EL C EL Data Management techniques EL C CS major Math: Discrete EL F F F Theory of programming languages C F F Math: Abstract F F Automata EL C F Languages EL C F Compilers EL C F EE/CE flavor Control Systems F C C EM fields F C EL Electronics (digital) C F EL Math: Stats C C C EL Signal Processing C C EL A&D Communication C EL SE flavor Protocols (nets) EL C C EL Computers in Communication Systems EL EL C Information Retreival EL C EL Computer Security EL C EL Performance Analysis of Computer Systems EL C CS flavor Data Base EL C C Eng. topics Optimization methods C C C EL Thermodynamics concepts C C C Heat Exchange concepts C C C Mechanics concepts C C C Chemistry (intro) C C C Stress Analysis Concepts C C C Structure & Properties of Materials C C C TABLE II: Analysis of Data

You can also read