Sky Service: The Demands of Emotional Labour in the Airline Industry

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Gender, Work and Organization. Vol. 10 No. 5 November 2003 Sky Service: The Demands of Emotional Labour in the Airline Industry Claire Williams* Following Hochschild’s The Managed Heart, which emphasized the prob- lematic features that emotional labour had for women flight attendants, a critical literature emerged which focused on the more enjoyable aspects of emotional labour in service employee experience. This article draws on this literature and analyses emotional labour as a gendered cultural perfor- mance but takes issue with the individualizing and pluralistic tenor in the post-Hochschild discussions. Using a qualitative and quantitative study of nearly 3000 Australian flight attendants, it focuses on organiza- tional and occupational health and safety variables, as well as sexual harass- ment and passenger abuse — factors barely discussed by Hochschild’s critics. The qualitative data indicate that emotional labour is both pleasur- able and difficult at different times for the same individual. Gender is still pivotal, as Hochschild suggested, linking emotional labour with sexual harassment. At the same time, the most significant predictors from the quantitative study of whether emotional labour would be costly were orga- nizational. Variables such as whether flight attendants felt valued by the company show that the airline management context is highly influential in the way in which emotional labour is experienced. As a means of under- standing the complex relations in this important and eroticized area of service work where flight attendants, airline crews, airline management and passengers have convergent and conflicting interests, the article also deploys a new concept: ‘demanding publics’, to refer to trangressions of the legitimate boundaries of the service worker. Keywords: emotional labour, sexual harassment, flight attendants, customer service, occupational health and safety Address for correspondence: *Claire Williams, Faculty of Social Sciences, Flinders University, Adelaide, e-mail: claire.williams@flinders.edu.au © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

514 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

Introduction

T he job of flight attending gained major attention through Arlie Russell

Hochschild’s The Managed Heart (1983) which coined the concept, ‘emo-

tional labour’, to describe the ‘relational rather than the task-based aspect of

work found primarily . . . in the service economy’ (Steinberg and Figart, 1999,

p. 9). A controversy generated by Cas Wouters (1989) then emerged about the

consequences of emotional labour for the individual service worker. As

Wouters put it, ‘Hochschild’s theoretical stance towards feeling makes her see

costs where there are none or hardly any’ (1989, p. 118). Subsequent research

and analysis has tended to support Wouters rather than Hochschild in

arguing that the performance of emotional labour is generally satisfying and

enjoyable (Frenkel et al., 1999; Wharton, 1993). Hochschild, and those who

have modified or challenged her analysis, have highlighted and extended our

understandings of the emotional and performative elements intrinsic to

service work. While retaining some of the key insights that these analysts

have provided, this article contends, on the basis of extensive empirical data,

that there are a number of related issues about service work and flight attend-

ing in particular that require more research, analysis and discussion.

What are some of these issues? Sexual harassment and abusive passen-

gers are major concerns for the flight attendants described in the studies

reported here. Neither Hochschild nor Wouters had much to say about such

matters. Accordingly the concept of ‘demanding publics’ is developed in this

article to gain some purchase on the various forms of abuse flight attendants

encounter during the course of their work. In this respect, basic employment

rights have yet to be established for service workers in the face of aggressive

and ‘difficult’ customers or passengers.

An important aspect of this study considers the organizational context for

the emotional labour characteristics of the job. The study asks under what

circumstances emotional labour is costly or satisfying for individual flight

attendants — and this includes the somewhat overlooked, yet crucial orga-

nizational context of occupational health and safety. The study incorporates

Hochschild’s emphasis on the kinds of heterosexual feminized gender per-

formance and ‘feelings work’ that women flight attendants are expected to

deliver and expects these to have greater effects for women than for men. It

adds sexual harassment from passengers and expects this to detract from sat-

isfaction. It investigates the airline managements’ seeming lack of acknowl-

edgement of the flight attendant function and expects this to add to the cost

of emotional labour for individuals. And, within this organizational context,

there is a shift towards what Findlay and Newton (1998, p. 225) call the

‘quasi-monarchic’ power that managements and hence airline managements

are increasingly able to deploy in dealing with employees.

At the same time, while the present articles draws on some of the service

work literature with its emphasis on performativity, the latter is deficient

Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003 © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003EMOTIONAL LABOUR IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY 515

when considering the central elements in flight attending. It is crucial to

understand that flight attendants are on aircraft first and foremost because

they are trained to carry out safety measures and only secondarily as employ-

ees providing a type of service to passengers. While dramaturgical concepts

have helped us to understand customer/service relations, the aircraft cabin

worksite is not a theatre, concert hall or entertainment centre. On major

domestic and international flights in Australia, a certain number of trained

flight attendants must be present in an aircraft to conform to government

regulations on safety. Failure to retain yearly proficiency standards in emer-

gencies, such as the ability to evacuate passengers from planes, is grounds

for dismissal (Williams, 1988, p. 111). In accidents, therefore, passenger

survival depends on crew member survival. Globally, flight attendants must

undertake rigorous emergency and survival training (Boyd and Bain, 1998,

p. 19). A fundamental tension exists between one aspect of production

(namely the generation of repeat customers) and safety, both in terms of the

safety of the aircraft and its ability to reach its destination and the occupa-

tional health and safety of the cabin crew. This is illustrated in the newly

emerging ‘air rage’ literature (Bor et al., 2001) where the cabin crew want to

brief passengers about airline policy on disruptive passengers at the start of

the flight but do not have the support of the marketing managers. Some

airline marketing strategies also encourage excessive alcohol consumption

and sexual fantasies about the availability of women flight attendants. These

promote a sense of entitlement in passengers and lower the standards of pas-

senger behaviour. Thus, as is discussed later in this article, flight attendants

have to negotiate an ambiguous world of work where the most important

part of their job, that is, safety, is subsumed within a less important but more

publicly visible display of service, captured in the concept of emotional

labour.

The research on which this article is based is a 1994 survey of 2912

Australian-based flight attendants investigating emotional labour, com-

mitment to employing organizations, occupational health and safety, the

work/family interface and union militancy. It will report on a segment of this

research, namely the emotional labour dimension, particularly as it relates to

the Wouters/Hochschild controversy. It will make some reference also to a

1988 survey of 1468 domestic flight attendants. The author began her study of

emotional labour amongst these Australian airline employees with the latter

survey and even then began to make links with sexual harassment and abuse

which the new concept, ‘demanding publics’, more fully articulates.

It should be stressed at the outset that these phenomena are culturally and

historically specific: what occurred, and still occurs, in the course of flight

attending work discussed here has an ‘Australian’ dimension on planes

crewed by Australian flight attendants here and overseas, and it may not

apply to the circumstances and experiences of planes crewed by ‘Asian’ or

‘European’ flight attendants1 (Folgero and Fjedlstead, 1995; Linstead, 1995).

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003 Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003516 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION Some of the unruly behaviour on flights originates with Australian sports teams who may be more prominent as passengers, given Australia’s strong sporting cultural identity. Emotional labour: some considerations As is well known, Hochschild’s study of United States flight attendants (which also focused on debt collectors) projected the significance of ‘feeling work’ in service organizations and occupations. She argued that the flight attendant job was different, depending on when the incumbent was a man or a woman. Women, particularly those who are recruited into a job like flight attending, are oversocialized into a demeanour which produces feminine skills in delivering deference (Hochschild, 1983, pp. 164–5). Here she was not making an argument about women per se, so much as the cultural creation and deployment of ‘patriarchal femininity’ (Pringle, 1988). The femininity was mobilized as part of providing service on an aircraft, and this was linked to emotional labour. Hochschild pointed out that women flight attendants were presented as distillations of subordinate feminine heterosexuality (1983, p. 175). One result, however, was that they were less protected from pas- senger misbehaviour because this subordination took away any status shield against passengers’ frustration and anger. Consequently, their own feelings received rougher treatment. She found that women flight attendants were more exposed than male flight attendants to rude, surly speech and tirades about the service and the airline (1983, pp. 171, 174). Hochschild (1983, pp. 37–42) makes the point that service work, for women especially, was an assault on the self and was potentially exploita- tive. It was a source of strain underneath displays of ‘surface’ and ‘deep’ acting. ‘Surface’ acting refers to managing the expression of behaviour rather than feelings. In this situation people know they are only acting. There is a clear division between the ‘face’ they consciously assume and their sense of their central ‘self’ or ‘me’. By contrast, ‘deep’ acting involves emotion work. People know they ought to feel something but, at that moment in their working day, they do not feel it. It is then that they engage in a series of momentary acts, to which they give little thought, to draw on their emotion memories so as to induce the required feeling towards a passenger. Hochschild regarded airline companies as engaging in sophisticated tech- niques that were located well beyond surface acting in the realm of deep acting. They suggested how staff could imagine and, thus, feel in specific encounters with passengers. It was in relation to deep acting that the psy- chological costs may potentially emerge, when the distinction between the ‘face’ and ‘central self’ can become blurred. Yet, as the present study shows later, this requirement of the job is insufficiently acknowledged by airline companies beyond the stage of initial recruitment and training. Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003 © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

EMOTIONAL LABOUR IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY 517 The Managed Heart opened up three related ways in which emerging areas of people work, such as the face-to-face relations central to customer service, could be theorized and understood. To begin with, Hochschild presented a gendered concept — emotional labour — which took seriously the qualities of the largely invisible sociability involved when women interacted with others in their everyday lives in families and workplaces. Women’s work has had a long history of being naturalized and being regarded as unskilled (Wajcman, 1991). Hochschild highlights these qualities, especially when parts of the self are made available in the job of the service worker to be consumed by customers or passengers. She suggests that the skills deployed should be socially and commercially acknowledged, even honoured. Secondly, Hochschild gives a political reading of emotional labour that should not be ignored. In choosing the word ‘labour’, she brought into the concept the relations of domination and subordination implicit in work (Lee, 1998, pp. 15, 27). Crucially, her analysis focused on the potential for alienation that arises from the commercialization of feeling involved in service work such as flight attending (Hochschild, 1983, pp. 17–19). This concept offers an alternative to the de-politicized and individualized litera- ture on ‘job stress’. But, as Newton (1995) suggests, this alternative has been slow to take off academically because stress discourse appeals to the prefer- ence of managements for a more individualized definition of employee sub- jectivity and whether employees are ‘stress fit’ or not (1995, p. 49). Hochshild’s third, and arguably most significant, legacy is that she fore- shadows the development of newer and more appropriate forms of occupa- tional health and safety for occupations in which emotions and feelings are an integral part. Although the situation is changing, with a greater recogni- tion of issues like bullying, even current occupational health and safety models and policies are still biased towards sudden traumatic injuries. But jobs such as flight attending (among a host of others in the service industry) carry their own dangers which do not readily fit into industrial and often male-oriented frameworks (Messing, 1998, pp. 120–1). In employment involving emotional labour, the customer, rather than the machine, in part sets the pace and nature of the labour process. Hochschild’s analysis inspired and even provoked a growing literature which will not be reviewed here. Rather, selected studies and commentaries (for example, Adelman, 1995; Schaubroeck and Jones, 2000; Wharton, 1993; Wouters, 1989 and others) that touch on the Wouters’ initiated controversy will be briefly reviewed and assessed to develop the point that the indi- vidualistic and depoliticized emphasis in the above literature illegitimately undermines the legacies from Hochschild’s pioneering contribution. In his study of five KLM flight attendants, Wouters took strong exception to Hochschild’s notion of the commercialization of feeling and her implicit concern with the exploitation inherent in service work. In his view, Hochschild was insufficiently detached and had, in fact, exaggerated the negative © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003 Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003

518 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

features. In his critique of Hochschild’s theoretical approach to emotion

management, Wouters claimed that she worked with ‘an image of a free and

independent individual with a natural self-regulation of his or her own, only

helped by some outside guidance’ (1989, p. 103). Here he seems to overlook the

social constructionist features of Hochschild’s own analysis (1983, Appendix

A). Nevertheless, he poses a more complex social constructionist view based

on Elias’s notion of a social habitus, which refers to the dominant pattern and

level of self regulation or emotion management in a society, and to social defi-

nitions of respect. Individuals learn to regulate their emotions according to the

social habitus. The long-term western trend towards democratization and

informalization creates more self-restraints but also allows for greater sensi-

tivity and flexibility and the possibility for enjoyment in the management

of emotions. Elias conceptualized as the ‘We-I-Balance’ the tension between

detachment and involvement, between the way people allow themselves to

give in to their impulses and self-interests while at the same time giving in to

the need and the necessity to take others into account (Wouters, 1989, p. 106).

Furthermore, Hochschild did not situate her work in a broad historical context

and, as Newton observes, ‘in consequence it might benefit from . . . the kind of

perspective provided by Elias’ (1995, p. 140).

Three reservations are, however, in order. Firstly, as Newton (1995)

indicates, it is highly questionable whether the long-term trend to informal-

ization has been extended to the workplace in a thoroughgoing way. The

monarchic power that employers wield is still significant and, after a phase

of democratization in the mid 20th century, is arguably gaining ground with

increasing casualization, the spread of individual work contracts and the

deregulation of occupational health and safety (Quinlan, 1999). Compared

with the 19th and early 20th centuries there is probably greater informality in

workplaces but managerialism frames the display codes which surround

workplace emotions and subjectivities (Newton 1995, pp. 72–7). Employees

are expected to maintain emotional control when operating front stage, that

is, to remain ‘cool’, not to vent aggression and certainly not to ‘crack up’. If

the latter occurs it should take place backstage or, best of all, in the private

sphere off stage.

Secondly, while Wouters dismisses in a footnote Hochschild’s analysis of

the social construction of gender at work (1989, p. 121) his own approach to

gender is superficial. For example, as Newton (1995) points out, Wouters fails

to examine the relationship of emotional control in the 20th century to the

types of permissible masculinities in the front stage of the workplace where

men are the main managers dictating display codes.

Thirdly, Wouters writes about the succeeding waves of democratization

and informalization as if they were the result of ‘natural evolution’ and not

the result of social struggles, conflicts and attempts to diminish exploitation.

Trade unions have been, and continue to be, part of the struggle to democ-

ratize workplace relations. Occupational health and safety represents one of

Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003 © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003EMOTIONAL LABOUR IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY 519

the most significant democratic rights won by workers in the west in the 20th

century. More pertinently, flight attendants have a long history of unioniza-

tion (Nielsen, 1984; Williams, 1988, p. 113) and, in the Australian case, within

a context of state-enforced conciliation and arbitration procedures which had

the effect of underpinning employee bargaining strength in disputes and

negotiations with employers. Many of the changes Wouters assumes in rela-

tion to flight attendants’ working conditions, such as part-time hours, child

care and gay employment rights, are the result of such political action, espe-

cially in this occupation, which has provided a model for good conditions

for service employees.

It is Wharton’s (1993) empirically sound research which supports Wouters

strongly in emphasizing the positive aspects of emotional labour. Women

workers who performed emotional labour in higher status professional jobs

were no more likely than men to suffer adverse consequences from the

performance of emotional labour and even reported higher levels of job sat-

isfaction than the men. On the other hand, in this comparative study of hos-

pital and bank workers, emotional labour did lead to increased emotional

exhaustion among workers with low job autonomy, longer job tenure and

longer hours. However, just because emotional labour is sometimes enjoy-

able and satisfying does not diminish the claim that it should be recognized,

socially honoured and performed in a context where workers’ health is

optimized. After all, it has never been suggested that, because skilled

manual workers enjoyed the use of their skills, they should not be paid for

them or socially recognized for them and that potential hazards should be

overlooked.

Wharton moreover situates her conception of emotional labour in the

innate qualities that individuals bring from their biographies to the work-

place such as the ability to monitor themselves. Her assumption is that such

qualities are ‘natural’ — requiring neither learning nor training. Conse-

quently she fails to examine the institutional and organizational characteris-

tics and management policies that are likely to mediate the costs of emotional

labour. Such oversights ignore the crucial point that regulation and moni-

toring by the self are socially organized and that individual performativity

is the outcome of specific social relations (Adkins and Lury, 1999, p. 602). We

have even reached the point where Morris and Feldman (1996), for example,

seriously advocate the screening out of potential employees for whom emo-

tional labour might be a problem. Adelman (1995) similarly calls for the

elimination of the two-fifths of workers in her study who chronically suf-

fered from a lack of fit between feelings and their expression. This sugges-

tion reproduces an erroneous association of emotions with individual

diseases of the mind that the Romans introduced into western culture

(Averill, 1996). By contrast, the sociology and anthropology of emotions take

the view that emotions are corporeal thoughts; they are complex, embodied

cognitive processes, imbricated with social values and frequently involved

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003 Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003520 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION in preserving social bonds (Rosaldo, 1984; Scheff, 1990). Social rules and social interactions are not only core features of the employment relation between management, employees and customers. They also help constitute the emotions which employees manage and display. According to this perspective, emotions are not correctly or incorrectly fabricated in ‘dysfunc- tional’ or ‘functional’ external contexts — like the family — before the employees arrive at work. Through their emotions, service workers can be empathetic to customers but at the same time be attuned to the violation of socially acceptable standards of conduct, including sexual harassment. Thus, the screening out process takes the social engineering of service employees to an extreme and reductionist point. Not only is it discrimina- tory, it is managerialist, and it is one of the least satisfactory strategies in the history of occupational health and safety. For example, formaldehyde is a common contaminant in the plastics industry. It can trigger acute allergic reactions such as asthma or skin rashes in some people and is also known to be a human carcinogen (Hubbard and Wald, 1993, p. 133). Removing workers who develop short term or temporary illnesses such as asthma leaves unpro- tected the remaining employees who may experience long-term effects like cancer. It can lead to the exposure of those remaining in the workplaces to even higher levels of the hazard. Excluding the ‘vulnerable’ category actu- ally worsens occupational health and safety practice. It would be far better to mitigate the hazard (for example, by substituting the chemical) or change the process in order to reduce risks for all of the employees. Psychologists like Adelman (1995) place the focus on so-called susceptible individuals who use the discourse of emotional labour (in their replies to her questionnaire) to talk about problems in their jobs. Adelman fails to examine the hazards themselves, their mitigation, or their removal. This strategy leaves unsafe the organizational context in which emotional labour is carried out and sends a message that the organizational environment will not affect negatively those who remain. Further to the above discussion, with the economic impact of globaliza- tion, the rise of Human Resource Management as an organizational philoso- phy and the spread of the ethos of ‘quality management’, power has passed increasingly from organized and unorganized workers to employers (Legge, 1995; McKinley and Starkey, 1998). Airline managements everywhere are under increasing pressure to be more viable and competitive than ever. In Europe cabin crews have already been replaced by ‘flag of convenience’ staff with lower training standards and more ‘flexible’ working arrangements (Boyd and Bain, 1998, pp. 18, 26). At the time of writing, the domestic and international airline, Ansett Australia, employing labour with regulated working conditions, has gone bankrupt. This occurred partly because of the entry into the market of Virgin Blue, with its deregulated labour practices. This airline pays its domestic flight attendants wages 34 per cent lower than Qantas and the former Ansett. Virgin Blue’s cabin crew clean aircraft cabins Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003 © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

EMOTIONAL LABOUR IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY 521

and help out with ‘ground tasks like administration and marshalling check-

in queues when they are not rostered to fly’ (Long, 2002, p. 6).

At this point, the article will present the concepts of demanding publics

and cultural and gendered performances to develop the point further that

emotional labour in the context of weakening employee power in the era of

customer service widens the space for customer abuse to occur. Here too,

management can be complicit in this process.

Demanding publics and cultural and

gendered performances

The service encounter has been described as an old but also a new kind of

social relationship, a special kind of ‘stranger’ relationship, informal and

quasi-intimate (Czepiel et al., 1985, pp. 4–6). It allows strangers to interact in

a way that transcends the barriers of social status. It is supposed to be limited

in scope and to have well-defined roles. But this article questions whether

this is the case and whether legitimate boundaries and limitations are

enforced for non-professional service workers like flight attendants.

The organizational or management perspective aims to have passengers

return to the airline as future customers and to give the business a competi-

tive edge. To a lesser extent, this business orientation entails some concern

for the motivation and retention of flight attendants as employees in order

to achieve its primary aims. The customer service and marketing literature

is quite clear about what kinds of customer satisfaction/dissatisfaction fit

with the primary production and competitive goals. Bitner et al. (1990) use-

fully summarize three kinds of passenger dissatisfaction with flight

attendants which airline companies legitimately seek to redress. Airline pas-

sengers are most satisfied or dissatisfied with the quality of the core service

and with the handling of requests for customized service. Next in importance

is when a flight attendant is unable or unwilling to respond when the system

fails, as it inevitably does at times; for example, if the plane is delayed or

overbooked and the flight attendant does little to help and seems uncon-

cerned. Of still lesser importance is the verbal and non-verbal behaviour of

flight attendants. However, even in this proto-management article, Bitner et

al. (1990, p. 82) discuss the boundaries of the service relationship:

Broad endorsements, encouragements, and guidelines such as ‘the

customer is always right’ or ‘we put service first’ are not enough. As all

customer contact employees soon find out, not all customers are right,

and some are even abusive and out of control.

The concept of ‘demanding publics’ refers to those situations where the inter-

ests of customers and service workers are in conflict and where management

has sided with customers or when its support for its service workers is, at

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003 Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003522 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION best, ambivalent. It includes situations where elements of customer abuse are present in the encounter. Also included are situations where there is no doubt that the rules of conviviality and respectful behaviour have been broken and, if service workers were not entrapped by the inadequate boundaries pro- vided by their employer, they would decisively exit the situation without fear of reprisal. Instead they are often forced to be loyal to both the abusive customer and their employer at the expense of their own health, well-being and safety. Therefore a question could be posed such as: what happens in the service encounter when customers engage in offensive behaviour? One way to explore this question is to regard emotional labour as a cultural performance. This article will use three different but inter-related readings of ‘perfor- mance’ to establish that emotional labour for flight attendants is a cultural performance. Embedded within the latter is a gender performance but, like all performances, it may go ‘wrong’ and not be carried off. ‘Performance’ (following Goffman, 1959) immediately suggests the presence of an ‘audi- ence’ (in this case, the passengers) who are also expected to play a part. Suc- cessful and recurring public performances such as those by jazz musicians have assumed expectations about audiences and the same is arguably true of organizational performances (Barrett, 2000). For example McDonalds’ cus- tomers are already ‘trained’ to be ready with orders, to move speedily and not to expect customized service (Leidner, 1996). In this context of perfor- mativity, the concept of demanding publics is about passengers as members of audiences who seriously unsettle the shared expectation that the perfor- mance will be carried off with mutual benefit to all, including a healthy and safe flight. One relevant definition of performance comes from Sass’s (2000) study of emotional labour as cultural performance in human service work. In this he seeks to extend emotional labour beyond a simple set of display behaviours, such as smiling, to include the interactive nature of emotional expression. He defines cultural performance as episodes through which members construct organizational reality. Pertinent to the workplace of the flight attendant are two of the types of rituals he defines (task and personal) and one type of sociality. Task rituals refer to recurring procedures to accomplish the job, including greeting, smiling, eye contact and thanking. Personal rituals are the particular styles flight attendants develop to negotiate their identity within the organization and their individual way of relating to passengers. In addition are sociality performances that encourage co-operation and promote smooth organizational operation. Sass (2000) calls these acts ‘courtesies’. Bitner et al. (1990) note their importance to passengers satisfac- tion when systems break down. These cultural performances of sociality and, to a lesser extent, the rituals, are either misunderstood or deliberately misused as an opportunity to take advantage by abusive customers, as the later data analysis will illustrate. Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003 © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

EMOTIONAL LABOUR IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY 523

To begin with, gender provides much of the cultural meaning for the

performance of sociality. Here, Butler’s (1994; 1997) conceptualization of

gender performance is crucial. In her conceptual schema, normative gender

identities are achieved by a set of repeated acts and repeated stylizations of

the body. The workplace is an obvious site where these gendered acts are

repeated. As each individual repeats the performances, they are constituted

by them as men/women and heterosexual/homosexual. This is not a vol-

untary performance where individual men and women deliberately and

playfully assumes their gender/sexual identity. Rather, people induce their

bodies to obey the accepted form of ‘men’ and ‘women’ for that point in

culture and history. It is a deadly serious process that serves to maintain

gender within its binary frame. It happens under constraints, through pro-

hibition and taboo. Compulsory heterosexuality is a fundamental part

of this. A heterosexual hegemony is therefore achieved by this gender

performativity.

But in the airline cabin workplace gender performativity bears an addi-

tional dimension. Hochschild’s analysis shows that women flight attendants

symbolize the heterosexual construction of woman; they are creations of

feminine heterosexuality, ‘highly visible distillations of middle-class notions

of femininity’ (1983, p. 175). Airline managements strongly socialize their

employees in recruitment and training and through grooming rules and

supervision, creating a rigid ‘natural’ appearance of the two genders and

‘natural’ heterosexual dispositions (Butler, 1997, p. 408). This is enforced

during the performances in front of the passenger audience. In Butler’s

terms, these performances are compelling social fictions. However, in the

example under review, the two halves of the binary of the social fiction

maintained by airline marketing are definitely not male and female flight

attendants: the gender icons are eroticized women flight attendants and

male pilots. Here the eroticized female flight attendant is conjoined with

an image of male pilots as bearers of eroticized heterosexuality. (Mills, 1995,

p. 180)

Male flight attendants, both straight and gay, and lesbians are a threat to

these social fictions. Williams’ (1989, p. 135) study of men and women in non-

traditional occupations suggests that women are less threatened psychologi-

cally than men by the presence of men in occupations regarded as ‘women’s

work’. Masculine gender is defined by that which is not feminine and it is

men, not women, who are instrumental in establishing this difference. Male

pilots (the technical crew), as will be discussed later in the data analysis,

engage in virulent forms of gender and a homophobic harassment of male

flight attendants that de-legitimate men in this occupation. Part of this

includes giving voice, but with derogatory intent, to the widely held stereo-

type — at least in the Australian context — that male flight attendants are

‘poofters’. This in turn makes straight male flight attendants defensive about

their sexuality.

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003 Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003524 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

Sufficient progress has been made in gay employment rights in Australia

in flight attending for gay identity to sometimes be safely expressed back-

stage (for example, in the galley) but not in the cabin where a homophobic

gaze prevails.

Nevertheless, while the presence of gay men is at least acknowledged pub-

licly (if ironically) by the presence of the stigmatizing stereotype, lesbian

identity in comparison is almost invisible. Whereas gay male flight attend-

ants do occasionally act gay publicly, some research suggests that lesbians

must present a convincing display of patriarchal femininity at work, in this

case in the airline cabin and in the airline workplace generally. Putting on

‘glamour drag’, (make-up, dresses, provocative poses) is a way for lesbians

to protect their secrets in an intensely homophobic workplace (Higgs and

Schell, 1998, p. 65). All of this makes both women and men flight attendants

more reflexively discursive about sex and gender and leads to a higher level

of conscious gender performance and parody than with other workers.

The section so far has established a conception of cultural performance

that is gendered and occurring in the aircraft workplace. This will be used

in the data analysis to follow. The idea has been introduced that the gender

component of emotional labour performances is highly stylized and may

invite sexual harassment but is also sometimes parodied. A third notion of

performance is also necessary to cover the contingency of ambiguous per-

formances of emotional labour but, more importantly, those that cannot

be sustained because of demanding publics. For this purpose, Hopfl and

Linstead’s (1993) concept of ‘corpsing’ can be used. This refers to the situa-

tion in the theatre when the audience is watching and waiting, but the actor

freezes to the spot and cannot sustain the illusion. In this case, the mask slips

and the audience is in doubt. Hopfl and Linstead (1993, p. 92) pose the impor-

tant question: What are the costs to corporate actors when they find their role

unbearable, and are ‘unable to carry on’? Passenger sexual harassment

promotes the possibility of occasional corpsing by flight attendants. In the

best case scenario, individuals feel sufficiently confident that organizational

reprisals will not occur to be able forcefully to reject the sexual harassment

occurring and call the police to meet the plane. In the worst case scenario,

individuals go to the union for assistance but are so demoralized that they

go on extended sick leave and eventually quit the occupation.

Before we discuss sexual harassment further, another point needs to be

made in delineating demanding publics. From Hochschild’s innovative con-

ception, the proposition can be established that service workers should not

be placed in the position where they have to present themselves for employ-

ment without well-established boundaries marking off the potentially dis-

tressing spaces of people work. Similarly, Paules’s (1991) work is suggestive

that a genuine space of safety and social honour around service work is pos-

sible, but first it is necessary to break the nexus with the notion of the 19th

century ‘silent servant’. In her view, because this notion has not been broken,

Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003 © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003EMOTIONAL LABOUR IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY 525 some customers assume the posture of ‘master’ to ‘servant’ with all the accompanying rights of irrationality, condescension and unrestrained anger (Paules, 1991, p. 163). This appears to be a vestige of the Masters and Servants Acts where workers could be brought before a magistrate for inso- lence, disobedience and absconding (Walker, 1988, p. 45). In the Australian case, workers in the pastoral industry (sheep and cattle) were central in the struggle to establish employment rights. They were deemed ‘servants’ under the Masters and Servants Acts and could be imprisoned for three months if they broke their labour contract (Fitzpatrick, 1969, pp. 366–7). This situation was not overturned until the shearers’ strike in the early 1890s which was pivotal in the development of tribunal employment law. However, service workers have never been incorporated into the full spectrum of employment citizenship because their occupations developed from pre-industrial social relations embedded in forms of employment such as domestic service (Kingston, 1975). According to Paules (1991) the paternalism of the ‘master–servant’ relationship is therefore the source of the widespread belief among customers that service workers who showed anger could be censured and could lose their jobs. The concept of demanding publics is an attempt to problematize these paternalistic relationships embedded in widely used dis- courses of quality service and the ‘customer is always right’. There needs to be a third party employment law (Hughes and Tadic 1998) to provide a shield between workers and customers and the employers who are on the same side on this issue. Sexual harassment is a special case of predatory paternalism. Hall (1993) has usefully researched what she calls ‘the job flirt’, which she defines as a job-prescribed form of sexual harassment. Her study of American waiters and waitresses takes a gendered organizations approach, regarding job tasks as loaded with gendered meanings. Hall found that waitresses were more likely than waiters to be sexually approached and harassed by customers. Servers themselves tended to differentiate between harassment and flirting and to associate harassment with female servers. While both men and women servers might flirt, both saw harassment as something done to wait- resses. Servers who provided good service were expected to enact three scripts: friendliness, subservience and flirting. But a kind of job flirt which was part of the service style applied more to waitresses than to waiters — that is, women were required to exhibit their sexual availability as part of the job — and so the job flirt encouraged customers to harass women staff sexually. In Adkins’ study of British service workers in tourism, women workers who tried to resist this sexual commodification risked dismissal or the aggression and abuse of men (1995, p. 154). One of the rare articles in the academic literature on customer sexual harassment (Hughes and Tadic, 1998) makes a similar point. There, women in retail were left with little choice but to normalize sexual exchanges as a routine part of the job. Hughes and Tadic © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003 Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003

526 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

directly tackle the issue of management power. They argue that tension exists

between policies which protect worker well-being and those promoting cus-

tomer service. Management requires service workers to approach customers

in a friendly and engaging manner. This creates an added layer of ambigu-

ity. The norms surrounding customer service in work that is explicitly sexu-

alized leads to intense constraints on workers and indirectly encourages

sexual harassment. The ubiquitous harassment Hughes and Tadic encoun-

tered in retail work was dealt with in individual and indirect ways. As a

result employees felt they could never use direct confrontation which might

lead to a complaint and would receive automatic negative job performance

evaluations by management. Sexual harassment at work is therefore not

a non-economic relation imposed on an economically-structured labour

market. Indeed it constitutes part of the (gendered) ‘economic’ itself (Adkins

1995, p. 155).

Having established the theoretical context of the article, the next section

will deal with methodology and findings of the empirical material.

Methodology and findings

In 1994 the author administered a survey of the membership of the Flight

Attendant Association of Australia.2 This union has comprehensive union

coverage of flight attendants (2912 answered — a 60 per cent response rate

for the whole population, not merely for a sample of a population). The

survey was carried out at a time of almost complete union membership and

so a very considerable number of flight attendants were reached. There are

also buoyant numbers for each of the main airline groups, ages and length

of service.

The survey especially encouraged flight attendants to describe their feel-

ings about the survey itself. This is important for two reasons. Morris and

Feldman (1996) suggest that this format, rather than face-to-face interviews,

may be more likely to produce the revelation of sensitive information. People

may be more honest about their feelings via anonymity. This is a way of

making this representation of the different flight attendants’ voices as promi-

nent as the researcher’s analysis.

The process of measuring the costs of ‘emotional labour’ has also

improved since my original research. The 1988 survey asked a question

which resonated with the respondents: ‘To what extent is it an accepted

feature of the Flight Attendant occupation that individuals are required to

control their feelings and smile (no matter how they feel at a particular time)

to create a good feeling in passengers?’ This was followed with a question

which just emphasized the costs of such behaviours/performances. In

response to Wouters’ (1989) critique of Hochschild, the next survey in 1994

Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003 © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003EMOTIONAL LABOUR IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY 527

reflected the possibility of satisfaction as well as costs. In addition, the words,

‘emotional labour’ were placed in the question itself: ‘To what extent is it an

accepted feature of the Flight Attendant occupation that you do “emotional

labour”? This means that individuals are required to control their feelings

and smile (no matter how they feel at a particular time) to create a good

feeling in passengers’. This was followed with a question which tried to

assess the costs or satisfaction to the individual. The question is long but such

questions are justified in methods texts (Cannell et al., 1981). Moreover,

Australian flight attendants are generally well-educated and my respondents

were no exception (67% had completed high school, 58% had post-secondary

qualifications including a degree; 18% were currently studying and 66% of

these were working towards a tertiary qualification.) So a question like this

was appropriate for them. The question itself reads:

There is disagreement about whether the daily management of your feel-

ings is a positive or negative job experience. This question is aimed to find

out if it is a job stressor or a source of satisfaction for you. One flight attend-

ant said ‘Making someone feel good is part of your daily job’. Another said

‘If you are not the best on a particular day and a passenger is upset and

takes it out on you, it can be very upsetting when you’re trying not to show

your feelings.’ Do you experience the management of your feelings on the

job as a source of satisfaction, or as a cost or source of stress to you?’

A source of great satisfaction

Slight source of satisfaction

Neither a satisfaction nor a cost

A slight source of stress

Creates a great deal of stress

The quotations used in the question were taken from comments written by

domestic flight attendants on the 1988 survey. Moreover, those who found

‘emotional labour’ satisfying in the 1988 survey did not elaborate on the rich-

ness of that satisfaction to any extent. It was as if it were a ‘non-cost’ rather

than a positive satisfaction — hence the addition of a scale in 1994.

In the 1994 survey respondents were also asked about the incidence and

handling of passenger anger and sexual harassment. A direct question on sex

was asked as well: ‘Do you ever feel there is a sexual component to the job

so that you are required to pay passengers sexual attention in addition to

the customer service relationship?’ Before the survey, these questions were

piloted on 20 flight attendants, who had no hesitation in making it clear

whether they thought a question was inappropriate or unrelated to their job

experiences. There was a positive reaction to the ‘emotional labour’ ques-

tions but a negative reaction to the direct sex question, which eventually

brought out a resounding answer in the negative from 77% in the final

survey. However this negativity did not extend to the questions on sexual

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003 Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003528 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION harassment. ‘Emotional labour’ as conceived by Hochschild was recognized instantly. The quantitative part of the study revolves around a log linear regression analysis. The latter allows us to discern if there is a relationship among vari- ables. It also enables us to gauge the strength of that relationship. In these data the dependent variable is cost/satisfaction with emotional labour. Here we are interested in finding out the relationship of each of the independent variables on the dependent variable, cost/satisfaction with emotional labour. Log linear regression allows a systematic evaluation of the relationship among independent variables, for example, gender and sexual harassment, including their effects on each other. There are two levels to the analysis. The first is called the univariate level, where we are assessing whether a variable is a significant predictor variable, (with a P-value

EMOTIONAL LABOUR IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY 529

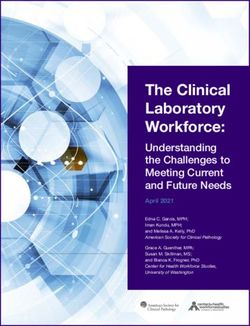

Table 1: Results of simple logistic regression = cost

Description OR (odds ratio) 95% CI overall P-value

Gender

Male n = 1027 1.00 0.001

Female n = 1837 1.32 1.12–1.56

Highest education level 0.060

Yr 10 1.00

Yr 11 1.31 0.99–1.74

Yr 12 1.31 1.04–1.64

Extent of value to company

Not much 1.00 0.000

Very little 0.68 0.54–0.85

Fair amount 0.45 0.35–0.57

A lot 0.17 0.12–0.26

A great deal 0.23 0.11–0.49

Management attitude causes 0.000

dissatisfaction

No 1.00

Some 2.09 1.62–2.72

A great deal 3.29 2.53–4.29

Staff morale

Low 1.00 0.000

Medium 0.52 0.45–0.63

High 0.23 0.15–0.36

Management treats as

individual

Very much as individual 1.00 0.000

Usually as individual 1.81 0.89–3.67

Varies 2.42 1.24–4.70

Number/part of category 3.86 2.01–7.41

Very much as category 4.02 2.08–7.77

Loyalty

No loyalty at all 1.00 0.000

Very little loyalty 0.47 0.28–0.79

Fair amount of loyalty 0.33 0.20–0.55

Lot of loyalty 0.22 0.13–0.38

Great amount of loyalty 0.19 0.11–0.34

Experience unwelcome

language

No 1.00 0.000

Yes 1.51 1.28–1.79

Unwelcome sexual

propositions

No 1.00 0.000

Yes 1.81 1.47–2.39

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003 Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003530 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

Table 1: Continued

Description OR (odds ratio) 95% CI overall P-value

FA job caused fatigue

Not at all 1.00 0.000

Very little 1.35 0.69–2.65

A fair amount 1.82 0.98–3.39

A lot 2.74 1.48–5.07

A great deal 3.55 1.94–6.49

27 year-old married woman flight attendant flying overseas for Qantas for

two years put it, ‘Often if I am feeling depressed, having to smile for PAX’s

[passengers] benefit lifts my emotional level’. This response suggests surface

acting rather than deep acting because there is a conscious performance of

positive sociality. Another theme amongst those who by and large found

emotional labour rewarding was the sense of achievement they derived from

overcoming difficulties at work. But, even when they did find it satisfying,

they also point to these difficulties. For example a 25 year-old single woman

flying for two years with a regional airline derived slight satisfaction from

emotional labour and stated, ‘It can be satisfying to do your job well under

duress but also very draining.’

Interestingly, a 22 year-old single woman, who had been flying 12 months

for a regional domestic airline where she is the only flight attendant on each

flight, answered that, for her, emotional labour was neither a source of

satisfaction nor a cost.

Single F/As must always be happy — no one else there!

Controlling my feelings is part of the ‘job’. It doesn’t make me feel better

or worse. It has to be done.

Her comment demonstrates how emotions are fundamental to the job and

that they have to be performed all the time to be effective. Furthermore, while

men derived the most satisfaction from emotional labour, they were reticent

about it. Those who did speak provide a few clues. One 28 year-old single

flight attendant flying for a large domestic airline for over two years said:

It doesn’t matter whether it’s a good day or a bad day. It’s important to

segregate one’s feelings in the workplace. If this is achieved it’s a great

feeling of achievement.

But other men, like the women, could find it stressful. A 32 year-old man,

flying overseas for Qantas for six years drew attention to the emotionally

abusive ‘demanding public’ in the context of having to smile after being

awake for 24 hours. He said:

Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003 © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003EMOTIONAL LABOUR IN THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY 531

Besides the physical stress of time change, long duties and the odd emer-

gency, the management of my feelings is the main source of stress. When

you are doing your best (and often covering the company’s mistakes) pas-

sengers who ridicule, really take it out of you emotionally.

Similarly a 33 year-old married male flight attendant, with ten years of flying

experience with a large domestic airline, answered that emotional labour

‘creates a great deal of stress’. He was also experiencing the highest level of

fatigue (‘a great deal’) from his job. He went on to make the connection

between the stress of his performance of emotional labour, the prevalence of

customer abuse and the conflict with his flight attendant identity as a safety

professional in the confined space of the cabin workplace:

For the goodwill of the PAX [passenger] to the company, the FA must

refrain from expressing contrary opinions to PAX and if a FA is maintain-

ing an important stance (e.g. cabin baggage) the company often will not

back up the FA. The FA’s are expected to take everything from a customer;

to blindly follow the adage: ‘The customer is always right’, no matter how

wrong the PAX is; or how dangerous their view, stance is (fighting to

smoke, insisting on cabin bags etc.) No matter how hard you try, some PAX

will love your assistance/service; whereas others will hate it. Often, those

who hate it will complain, forcing the FA to be questioned by management

who will not acknowledge the good comments in an equivalent manner.

In relation to angry passengers he went on to say:

As customers have more ‘consumer rights’ in deregulation, [the climate

created by the deregulation of government airlines] they feel they have

a right to take it out on us and again, we don’t often get backed up by

management.

As a result he worked out in the gym; used punching bags and cried as his

ways of handling his feelings relating to incidents with angry passengers.

This man’s detailed account suggests the difficulties with creating a cultural

performance when a core organizational task (to observe safety regulations)

is ambivalently represented to passengers by airlines. He enforces cabin

baggage policies because bags not firmly secured become dangerous missiles

in an airline incident or crash. Women also made the point that passengers

can be abusive when they enforced cabin baggage regulations.

Moreover, if we return to the first stage of the quantitative analysis (the

univariate level in Table 1), other information emerges on how the facets of

gendered and cultural performances are linked to the experience of emo-

tional labour. As noted earlier, emotional labour as a stressor was constructed

as the response variable. The independent variables related to gender, orga-

nizational, occupational health and safety and individual characteristics (see

Table 1). In terms of the first, or univariate logistic regression, the individual

© Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003 Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003532 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION variables were not found to be statistically significant in relation to the ex- perience of emotional labour, except for education and then only marginally so. But the gender variables were significant, especially sexual harassment, which is related directly to femininity, masculinity and sexual preference. That is to say, those who had been sexually harassed by unwelcome and vulgar language, off-colour jokes, embarrassing remarks or stories about women’s bodies, sexual intercourse or their sexual preference were 51 per cent more likely to experience emotional labour as a cost than those who had not been sexually harassed. Similarly, those who had experienced unwelcome sexual propositions in their present job were 81 per cent more likely to experience emotional labour detrimentally. In the qualitative data many flight attendants also wrote that emotional labour was not so straightforward as defined in the survey. In fact, it was satisfying at times and at other times costly. As one of them stated: It’s great to come off a flight on a high, you’ve made the passengers happy and receptive to you. As you’re saying Goodbye, you’re getting a response, eye contact, thank you’s, hope to see you next flight! Then there are days when you’re happy and friendly and they just don’t want to acknowledge your presence or nothing you can do will help solve their problem. You are verbally abused and left standing red faced with a plastic smile crumbling on your face. (30 year-old single woman flying for a domestic airline for ten years) Another woman made a direct connection with fatigue: It is satisfying to know you can do it (manage your feelings) but it does take its toll and results in fatigue. (35 year-old divorced woman flying for 13 years for a large domestic airline) My data suggest that Wouters and others are right to emphasize emotional labour as potentially positive, but that this is not straightforward. Other find- ings conform only marginally to Wouters’ idea of intrinsic satisfaction and the skill of playful flexibility exemplified in one of the KLM flight attendants he spoke to who said she liked to build up light-hearted exchanges with pas- sengers after she put them at their ease. These Australian flight attendants are closer to Paules’s interpretation of waitresses who actively reformulate and reject the coercive forces they encounter. They also describe working at the development of skills to maintain a sense of well-being. They frequently observe the emotional reactions of other flight attendants and suggest ways the latter could redefine negative encounters with passengers: How you feel is a personal choice except under circumstances of extreme stress. I refuse to take things too personally. I decide how I will feel for the day. I have read many books on not letting others pull my strings. I often think such books or training would be helpful to flight attendants as it con- Volume 10 Number 5 November 2003 © Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2003

You can also read