Retrospective Review of Mycobacterial Conjunctivitis in Cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus)

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery 34(3):250–259, 2020

Ó 2020 by the Association of Avian Veterinarians

Retrospective Study

Retrospective Review of Mycobacterial Conjunctivitis in

Cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus)

Stephanie K. Lamb, DVM, Dipl ABVP (Avian), Drury Reavill, DVM, Dipl ABVP (Avian),

Dipl ABVP (Reptile and Amphibian), Dipl ACVP, Rebecca Wolking, BS, and

Bob Dahlhausen, DVM, MS

Abstract: The etiologic disease organism responsible for causing mycobacteriosis in avian

species is an acid-fast gram-positive bacterium. This bacterium causes granulomatous disease in

various internal organs, but in cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus) it has been commonly identified

within the conjunctival tissues. Twenty-six cases of mycobacterial conjunctivitis in cockatiels were

diagnosed through histopathologic assessment of diseased tissue samples, Fite acid-fast staining,

and polymerase chain reaction in this retrospective study. Clinicians who saw these cases were

contacted, and information was obtained regarding recommended treatment protocols prescribed

for the patients, the Mycobacterium species identified, and case outcomes. All patients in this

retrospective study had a biopsy performed on the affected conjunctival tissue, and because of the

small size of the patients, this excisional biopsy removed the affected tissue in its entirety or

significantly debulked the lesion. Of the 26 cases, 10 were lost to follow-up, 4 were euthanatized, 7

died, and 5 were alive at the time this information was submitted for publication.

Key words: Mycobacterium species, conjunctivitis, psittacine, avian, cockatiel, Nymphicus

hollandicus

INTRODUCTION cobacteriosis also infects humans and is considered

a zoonotic organism.1–9 With regards to avian

Mycobacteriosis is caused by bacterial species

species, mycobacterial infections have been isolat-

within the Mycobacterium genus, which are char-

ed from virtually every order. More than 130

acteristically acid-fast bacilli, aerobic, slow grow-

species of mycobacteria are currently recognized

ing, and highly resistant to extremes in

environmental conditions. Mycobacterium species and .10 of these species has been documented to

infections in avian species can result in devastating, infect birds.1,3 These Mycobacterium species in-

chronic, and often systemic disease. This genus of clude M avium subsp avium, M genavense, M

bacteria has affected many different domestic and tuberculosis, M bovis, M gordonae, M nonchromo-

nondomestic species, from cattle, sheep, and genicum, M fortuitum subsp fortuitum, M avium

rabbits to bears, giraffes, and rhinoceroses.1 Exotic subsp hominissuis, M peregrinum, M intermedium,

pet animals that have been diagnosed with M celatum, M intracellulare, M avium subsp

mycobacteriosis include reptiles, ferrets, hamsters, paratuberculosis, M africanum, and M simiae.1,3,5

amphibians, fish, and birds.1–9 Importantly, my- Several case reports describe cases of mycobac-

teriosis in pet psittacine birds. Psittacine birds that

From the Arizona Exotic Animal Hospital, 744 N Center St

commonly appear to be diagnosed with mycobac-

#101, Mesa, AZ 85201, USA (Lamb); Zoo/Exotic Pathology teriosis include budgerigars (Melopsittacus undu-

Service, 6020 Rutland Dr #14, Carmichael, CA 95608, USA latus), brotogerid parakeets (Brotogeris species),

(Reavill); Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic Lab, PO Box Amazon parrots (Amazona species), and pionus

647034, Pullman, WA 99164, USA (Wolking); and Veterinary

parrots (Pionus species).10–13 Postmortem surveys

Molecular Diagnostics, 5989 Meijer Dr, Suite 5, Milford, OH

45150, USA (Dahlhausen). have found Amazon parrots and cockatiels (Nym-

*Corresponding Author: Stephanie K. Lamb phicus hollandicus) to be the most commonly

stephlovesbirds@hotmail.com affected psittacine birds.14,15 Historically, specia-

250LAMB ET AL—MYCOBACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS IN COCKATIELS 251

period are reviewed. The species of mycobacterium

identified, the treatments patients received, and the

final disposition of the patient were evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Records of avian submissions were reviewed

from Zoo/Exotic Pathology Service (Carmichael,

CA, USA) from 2000 to 2019. Inclusion criteria

included only cases from cockatiels that presented

with a final diagnosis of conjunctival mycobacte-

riosis determined by histopathologic evaluation of

submitted tissue samples and histochemistry (Fite

acid-fast staining) and confirmed by polymerase

chain reaction (PCR). Both biopsy and postmor-

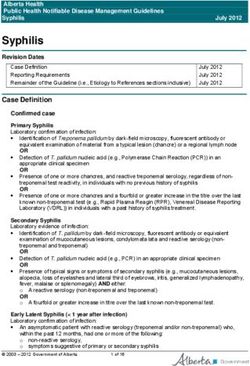

Figure 1. A cockatiel included in this retrospective study tem samples were included. Veterinary hospitals

with a mass extending from the conjunctiva of the lower from which cases originated were contacted for

eyelid. A Mycobacterium species was identified as the follow-up information regarding the individual

pathologic bacterium that caused the disease condition. patients. Questions that were asked included if

and how the patient was treated, what species of

tion of mycobacteria was problematic because of mycobacterium was identified, and the final

the inherent difficulty in culturing the organism. disposition of the patient.

Therefore, most cases of mycobacteriosis in pet Two different laboratories were used to identify

birds were assumed to be from M avium-intra- the species of mycobacteria by PCR. Twenty-two

cellulare complex. However, in the early 1990s samples were evaluated by the Washington Animal

advances in isolation methods, including culture Disease Diagnostic Laboratory (Pullman, WA,

techniques and the use of molecular analysis, USA). Five samples were assessed by Veterinary

allowed for the identification of M genavense to Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory (Milford, OH,

be recognized as a more common cause of USA).

mycobacteriosis in pet psittacine birds.16–19 Of the samples evaluated by the Washington

Mycobacterial lesions can occur in any organ; Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, DNA was

however, they are most often identified in the extracted from samples as previously described,

intestines, liver, spleen, and bone marrow.2,3,11,20 and the presence of M genavense was tested by

Less affected organs include the conjunctiva, real-time PCR targeting a portion of the heat

kidney, muscles, gonads, and endocrine organs.3 shock protein gene.25,26 Next, to confirm the DNA

Histologically, mycobacterial lesions are typically sequence, universal mycobacterial primers ampli-

granulomas and have a necrotic center surrounded fied a portion of the 16S–23S ribosomal internal

by macrophages, giant cells and heterophils.3,21 transcribed spacer (ITS) region in 15 of the

Although not frequently reported in the literature, samples, as previously described, and sequenced

granulomas of the conjunctiva of cockatiels are by an outside vendor (Genewiz, South Plainfield,

particularly common (Fig 1).21 NJ, USA).27 Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

Mycobacteriosis treatment regimens have been (BLAST; National Center for Biotechnology

extrapolated from human medicine and previous Information, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to

case reports. Euthanasia is often recommended, analyze the consensus sequences.

but for those that do decide to treat, effective drugs For the samples that were submitted to the

include macrolides, fluoroquinolones, rifamycins, Veterinary Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, a

tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, ethambutol, dap- real-time/quantitative polymerase chain reaction

sone, ethionamide, cycloserine, and clofazi- with primers MG22 and MG23 was used to

mine.5,22 Often antibiotic cocktails are prescribed amplify a 155–base pair (bp) segment of the M

to provide a more robust antibiotic treatment and genavense, hypothetical 21-kd protein gene (Gen-

reduce the chance for bacterial resistance. Combi- Bank AF025995.1).28 Primers Mycgen-f and My-

nations of medications and their dosages have been cav-r were used to amplify a 180-bp fragment

described and are available for birds.23,24 specific for M avium complex.29 The primers stated

In this retrospective study, cases of mycobacte- above were used for all 5 samples submitted to the

rial conjunctivitis in cockatiels over a 19-year Veterinary Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory.252 JOURNAL OF AVIAN MEDICINE AND SURGERY

RESULTS triculus had severe, chronic, ulcerative gastritis

with transmural granulation tissue, and the kid-

Forty cases of avian mycobacterial conjunctivi-

neys had multifocal glomerular fibrosis and tubu-

tis were identified; however, only 26 of these cases

lar mineralization. Extramedullary hematopoiesis

met the inclusion criteria to be evaluated in the

was also found in the liver and spleen.

study. All cases were located within the United

The Mycobacterium species was identified in all

States and were from 10 different states, including

cases. M genavense was detected in 25 samples and

South Carolina, Utah, Arizona, Missouri, Colo-

rado, California, Florida, Louisiana, Washington, M avium was found in 1 sample. All 21 samples

and New York. The states that had the highest sent to Washington Animal Disease Diagnostic

proportion of cases evaluated in this retrospective Laboratory that were positive for Mycobacterium

study were California (10 cases), and Colorado (6 had 100% identity with M genavense GenBank

cases). The ages of the birds ranged from 2 to 15 Y14183. Of the 5 samples submitted to Veterinary

years; however, in 6 birds the age was not known. Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, 4 of the

Eight birds were male and 15 were female, and in 3 samples revealed the species of mycobacterium to

birds, the sex was unknown. The presenting be M genavense. One of the samples identified M

complaints for the avian cases evaluated included avium.

chemosis, blepharospasm, erythema of the con- All cases had a biopsy performed to diagnose

junctiva, and ocular discharge. Although chemosis mycobacteriosis, which, for many, was macroscop-

was the most common clinical sign, not all patients ically a complete surgical excision because of the

had overt disease. Concurrent diagnosed diseases patient’s size. Nine of the 26 cases had a biopsy

were not evaluated for this investigation. All alone without any other treatments. Additional

patients in this retrospective study had a biopsy treatment was administered to 17 of 26 cases. Of

performed on the affected conjunctival tissue, and those that received additional treatment, 7 of 26

because of the small size of the patients, this had topical medication alone, 3 of 26 had oral

excisional biopsy surgically removed the affected medication alone, 4 of 26 had oral and topical

tissue in its entirety or significantly debulked the therapy, 1 of 26 had topical and injectable

lesion. Table 1 lists all treatments, final disposition, medication, and 2 of 26 had oral, topical, and

histopathology results, age, and sex of each patient injectable medications. Medical management con-

included in this study. sisted of antibiotic drugs and occasionally nonste-

All lesions were described as granulomatous roidal anti-inflammatory medication.

conjunctivitis (Fig 2), but some had further The final outcomes for the patients varied. Of 26

qualifications, which are described in Table 1. cases, 10 were lost to follow-up. Of those where

Lesions were subjectively considered moderate to follow-up data were available, 4 were euthanatized,

severe. One sample had a significant heterophilic 7 died, and 5 were still alive at the time this

infiltrate along with the granulomatous conjuncti- manuscript was submitted for publication.

vitis, whereas a separate sample had necrotizing Of the 7 birds that died, 4 died within 2 months

granulomas. Fite acid-fast staining was performed of diagnosis, with the earliest dying within 3 days

on tissue samples submitted from each case, and of diagnosing mycobacteriosis. Of these, 3 were

acid-fast microorganisms were identified in all prescribed topical medications, and 1 was treated

samples (Fig 3). with topical and injectable medications. An addi-

Two cases from which a biopsy of the conjunc- tional 3 birds died between 2 and 3 years after

tiva was used to confirm the diagnosis of myco- being diagnosed with mycobacterial conjunctivitis.

bacteriosis were also submitted for a full One of these birds was known to have died from

postmortem examination after death or euthana- egg binding, whereas the cause of death was not

sia. Granulomatous adrenalitis, multifocal mild determined in the other 2 cockatiels. Five birds

subacute interstitial nephritis with membranoglo- were still alive at the time of this writing. More

merulopathy, focally extensive granulomatous than a year had elapsed from the diagnosis of

enteritis, and multifocal nodular granulomatous mycobacterial conjunctivitis in all these individu-

air sacculitis, in addition to a focally extensive als. One individual was still alive 7 years after a

moderate to severe granulomatous conjunctivitis, diagnosis was obtained. Of the 5 birds that were

were identified in one case. In the second case, still alive at the time of this writing, 1 was not

chronic granulomatous conjunctivitis was recog- receiving any treatment, 2 were receiving topical

nized along with rare granulomas in the liver and treatments at times when an erythematous con-

adrenal glands. The isthmus region of the proven- junctiva was observed, and 2 were actively beingLAMB ET AL—MYCOBACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS IN COCKATIELS 253

Table 1. Treatments, final disposition, histopathologic diagnosis, sex, and age of birds included in this retrospective

study of 26 cockatiels identified with conjunctivitis caused by Mycobacterium species over 19 years.

Bird no. Treatment Final disposition Histopathologic diagnosis Age, y Sex

1 Biopsy, enrofloxacin oral, Lost to follow-up Diffuse severe chronic active 6.5 M

doxycycline injectable, pyogranulomatous conjunctivitis

terramycin topical

2 Biopsy, ethambutol oral, Lost to follow-up Diffuse moderate to severe chronic 9 M

rifampin oral, granulomatous conjunctivitis with

isoniazide oral granuloma

3 Biopsy, rifampin oral, Still in treatment Granulomatous conjunctivitis 3 M

ethambutol oral, actively

ciprofloxacin oral

4 Biopsy, gentamycin Still in treatment Granulomatous conjunctivitis 5 F

topical, meloxicam oral actively

5 Biopsy alone Euthanatized Granulomatous conjunctivitis 10 F

6 Biopsy, tobramycin Died 2 weeks Biopsy: granulomatous conjunctivitis 3 F

topical postdiagnosis Postmortem examination: granulomatous

adrenalitis, multifocal mild subacute

interstitial nephritis with

membranoglomerulopathy, focally extensive

granulomatous enteritis, focally extensive

moderate to severe granulomatous

conjunctivitis and cellulitis, multifocal

nodular granulomatous air sacculitis

7 Biopsy, rifampin oral, Died 3 years after Severe granulomatous conjunctivitis 15 M

enrofloxacin oral, diagnosis,

ethambutol oral for 6 undetermined

months cause

8 Biopsy alone No treatment Diffuse severe granulomatous conjunctivitis 3 M

postsurgery, died

2 years

postdiagnosis,

undetermined

cause

9 Biopsy, meloxicam oral, Died from egg Severe chronic active granulomatous Unk F

gentamycin topical as binding 3 years conjunctivitis

needed for flare-ups after diagnosis

10 Biopsy, ofloxacin topical, Still in treatment Granulomatous conjunctivitis 6.5 M

flurbiprofen topical as PRN when

needed for flare-ups erythematous

conjunctiva

11 Biopsy, ofloxacin topical Still in treatment Right nictitating membrane necrotizing Unk F

as needed for flare-ups PRN when granulomas and granulomatous

erythematous conjunctivitis

conjunctiva

12 Biopsy alone Lost to follow-up Granulomatous conjunctivitis 10 F

13 Biopsy alone Lost to follow-up Granulomatous conjunctivitis 4 F

14 Biopsy, bacitracin, Died 9 days after Granulomatous conjunctivitis Unk Unk

neomycin, polymyxin diagnosis

topical

15 Biopsy alone Alive, no treatments Granulomatous conjunctivitis 5 Unk

currently

16 Biopsy alone Lost to follow-up Granulomatous conjunctivitis 5 F

17 Biopsy alone Lost to follow-up Diffuse moderate to severe chronic Unk F

granulomatous conjunctivitis with

multifocal granulomas and dense

fibroplasia254 JOURNAL OF AVIAN MEDICINE AND SURGERY

Table 1. Continued.

Bird no. Treatment Final disposition Histopathologic diagnosis Age, y Sex

18 Ciprofloxacin topical and Euthanatized Granulomatous conjunctivitis 4 M

meloxicam oral 2 years

before biopsy. Biopsy,

doxycycline injection

19 Biopsy, bacitracin, Lost to follow-up Granulomatous conjunctivitis Unk F

neomycin, polymyxin

topical

20 Biopsy, neomycin, Died 3 days after Granulomatous conjunctivitis 11 F

polymyxin, diagnosis

dexamethasone topical,

meloxicam oral

21 Biopsy alone Lost to follow-up Granulomatous conjunctivitis 10 Unk

22 Biopsy alone Euthanatized Granulomatous conjunctivitis 2 F

23 Biopsy, bacitracin, Alive, no treatments Granulomatous conjunctivitis 7.5 M

neomycin, polymyxin currently

topical 3 years

24 Biopsy, ciprofloxacin Died 2 months after Granulomatous conjunctivitis Unk F

topical, doxycycline diagnosis

injectable

25 Biopsy, ketorolac topical, Euthanatized Biopsy: granulomatous conjunctivitis 10 F

tobramycin topical, Postmortem examination: chronic

enrofloxacin oral, granulomatous conjunctivitis. Rare

meloxicam oral granulomas in the liver and adrenal glands.

Severe, chronic, ulcerative gastritis with

transmural granulation tissue in the

proventricular isthmus. Multifocal

glomerular fibrosis and tubular

mineralization of the kidneys.

Extramedullary hematopoiesis in the liver

and spleen.

26 Biopsy, ciprofloxacin Lost to follow-up, Granulomatous conjunctivitis 12 F

topical, flurbiprofen alive for 5 weeks

topical, gentamycin post-op

topical

Abbreviations: M indicates male; F, female; Unk, unknown; PRN, as needed.

treated with either oral or topical antibiotic literature describe ophthalmologic lesions in birds

therapy. with mycobacteriosis to include granulomatous

nodules in the conjunctiva, eyelids, and cor-

DISCUSSION nea.3,30–37 Corneal vascularization and edema have

Mycobacteria are bacterial organisms that can also been noted.37 Swellings in the periocular

result in an infectious disease that is often chronic region have been described, and serous-to-gelati-

in nature and causes granulomatous lesions in nous discharge has occasionally been observed.33,36

various organs and tissues of the body. This An Amazon parrot that was presented with

retrospective study evaluated mycobacteria local- conjunctivitis, chemosis, and exophthalmos of the

ized to the conjunctiva of a common pet psittacine left eye was diagnosed by postmortem examination

bird, the cockatiel. The unifying presentation with caseous endophthalmitis from mycobacterio-

reported here has been commonly recognized by sis.35 In a recent retrospective study of mycobac-

pathologists but not sufficiently discussed in the teriosis in psittacine birds, ocular lesions were

literature.21 identified in only 4 of 123 cases. Lesions consisted

Mycobacteriosis in psittacine birds often affects of swelling of the eyelids and conjunctiva, thick-

the liver, spleen and intestines.3,30 However, ocular ening of the third eyelid, and nodules in the bulbar

lesions do occasionally occur. Reports in the conjunctiva and third eyelid.30LAMB ET AL—MYCOBACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS IN COCKATIELS 255 Figure 2. Granulomatous conjunctivitis identified in a cockatiel that was evaluated in this retrospective study. Open arrow points to a multinucleated giant cell within the granuloma surrounded by fibrous connective tissue and histiocytic inflammation (hematoxylin and eosin; bar ¼ 50 lm). Other differential disease diagnoses for the infection of M genavense and M avium.30 In a previously noted ocular signs reported for myco- separate case report on pet birds, M genavense was bacteriosis include mycoplasmosis, chlamydiosis, responsible for 30.9% of mycobacterium cases, and Pasteurellosis, poxvirus, trauma, and postorbital M avium was only responsible for 12.7%.39 These masses. There are few studies on ocular lesions in studies further corroborate the findings in this birds, with most reports being performed in review, wherein M genavense was identified in 25 of raptors, in which trauma has been identified as 26 cases, and M avium was identified in only 1 case. the cause for up to 90% of ocular lesions.38 Treatment of avian mycobacteriosis is both Many species within the Mycobacterium genus controversial and complicated. Some authors can affect birds. Originally, it was believed that recommend euthanasia and cite numerous motives. most cases were from M avium-intracellulare One reason is therapeutic drugs need to be present complex. With improvements in molecular analysis in tissues at correct concentrations and locations. and culture techniques, M genavense has been Unfortunately, pharmacokinetic studies to deter- found to be a more common causative agent, and mine if these parameters are achieved have not numerous avian case reports have been presented been performed in birds. Other concerns regarding on this species.16,18,19,30,39–44 In a retrospective 20- treatment for avian mycobacteriosis is that the year survey of companion birds, of 24 cases where infected avian patient may be shedding organisms, mycobacteriosis was identified, 23 were from M exposing other birds.2,23 Mycobacterium organisms genavense.18 A separate study, where PCR testing have the potential to be zoonotic, therefore, young, was performed on tissues of 22 psittacine birds, elderly, and immunocompromised people may be revealed M genavense to be responsible for 19 cases more at risk of possible infection. Moreover, of mycobacteriosis, whereas M avium was only studies have indicated differences in drug suscep- identified in 2. One case was found to have a dual tibility for different mycobacterium species that

256 JOURNAL OF AVIAN MEDICINE AND SURGERY Figure 3. Positive Fite acid-fast staining in the conjunctiva of a cockatiel that was evaluated in this retrospective study. Open arrow points to acid-fast bacilli within a granuloma in a conjunctival biopsy sample (bar ¼ 50 lm). may lead to a poor response to therapy.45 Drug mycobacterium’s propensity to mutate rapidly and resistances, a prolonged course of treatment, develop antibiotic resistance. The assumption is treatment compliance by the owner, and difficulties that when using an antibiotic cocktail, the myco- in drug administration are other notable reasons bacteria that are present may be resistant or for not treating avian mycobacteriosis and recom- develop resistance during treatment to one of the mending euthanasia.5 Four cases in this retrospec- medications but is less likely to be resistant or tive study were euthanatized. An additional 10 develop resistance to all of the prescribed drugs.5,22 cases were lost to follow-up. It is unknown whether Previous cases have reported successful mycobac- these cases were euthanatized, died, or received teriosis management with a combination of rifa- treatment at other veterinary facilities. b ut i n , e t h a m bu t o l , c l a r i t h r o m y c i n , a n d For those who decide to treat, it is important to enrofloxacin treatment for 1 year.46,47 Other cases note that no set guidelines for treatment exist in have effectively treated avian mycobacteriosis with avian patients, as they do for humans. Therefore, isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol.48 Treatment dosing regimens have been extrapolated from lengths are variable and have ranged from 1 to 18 human medicine and previous avian case reports. months or more. In an ideal situation, treatment When humans are treated for mycobacteriosis, it is length should extend several months beyond the standard to prescribe a combination of 3 or 4 last positive biopsy or culture.10,22 antibiotic drugs. The reasoning behind the antibi- The patients in this report were prescribed otic cocktail approach can be explained by the different drugs to treat avian mycobacteriosis. All

LAMB ET AL—MYCOBACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS IN COCKATIELS 257 26 patients had a biopsied tissue sample submitted meloxicam. For the 2 birds that were prescribed for histopathologic evaluation to diagnose myco- treatment on an as-needed basis, both were bacteriosis definitively, but because of the small receiving ofloxacin topically, and 1 of the 2 size of the patient, this also functioned as an individuals also was administered topical flurbip- excisional biopsy that removed the diseased tissue rofen. With the wide variation in treatment in its entirety in most cases. It cannot be regimens for avian mycobacteriosis and limited determined whether the biopsy completely re- patient size, conclusions cannot be determined moved all the diseased tissue microscopically regarding the best treatment option for this disease because complete postmortem histologic evalua- in cockatiels. tion of each patient was not available. In the 2 One of the limitations of this report is that only cases where this information was available, the the conjunctiva was evaluated for mycobacterial patients had an original biopsy to diagnose the lesions in all but 2 individuals. One case had a full disease and then a full histopathologic evaluation postmortem examination performed when it died 2 after death. Both patients did have lesions in the weeks after a definitive diagnosis of mycobacterial conjunctiva noted on postmortem examination; conjunctivitis was obtained through the histopath- therefore, the diseased tissue was not completely ologic evaluation of tissue collected from a removed during the biopsy procedure. Because of conjunctival biopsy. In this case, granulomas were the retrospective nature of this report, further found in the adrenal gland, intestines, and air sacs, information on whether complete removal of the in addition to the conjunctiva. Moreover, this diseased tissue during the surgical procedure was patient was being treated with topical tobramycin achieved, with and without additional medical at the time of its death. A second patient was management, cannot be determined. euthanatized within a few weeks of diagnosis. It Seventeen patients received medical manage- too had mycobacterial granulomas in the adrenal ment that included topical, oral, and injectable glands and liver. It would have been ideal to have treatments, in addition to a conjunctival biopsy. other organs evaluated for mycobacteria infection Topical antibiotic therapy included terramycin, in all patients; however, the retrospective nature of tobramycin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gentocin, and this report prevents further evaluation; therefore, bacitracin, neomycin, and polymyxin with and mycobacterial lesions in other organs from the without dexamethasone. Oral antibiotic treatment cases not examined could not be ruled out. Future included enrofloxacin, ethambutol, rifampin, iso- studies should be performed to assess other organs niazide, and ciprofloxacin. Doxycycline was the for mycobacterial lesions when a cockatiel patient only injectable antibiotic used. Nonsteroidal anti- is diagnosed with mycobacterial conjunctivitis. inflammatory medications were used in a few No attempt was made in this retrospective study patients and included oral meloxicam or topical to correlate the histologic appearance of the flurbiprofen or ketorolac. Sixteen of 26 cases had conjunctival biopsies to any prognostic factors. follow-up information available. Of the 4 patients The techniques used to collect the biopsy samples who were euthanatized, 2 had medical treatments varied between cases, times differed from when the in addition to a conjunctival biopsy. Of the 4 lesion was first observed by the owners, and patients that died within 2 months of diagnosis, all different treatments were prescribed for the cases were receiving topical antibiotic therapy, with 1 before biopsy collection, all of which might patient also receiving an injectable antibiotic drug. account for minor variations in the interpretation Of the 3 that died 2 to 3 years after diagnosis, 1 of the histology of the biopsy samples. One sample patient had the conjunctival biopsy, 1 received with more heterophilic inflammation was suspect- topical antibiotic therapy and oral meloxicam as ed to be associated with self-inflicted trauma to the needed, and 1 was prescribed rifampin, enroflox- enlarging conjunctival mass. Not all samples acin, and ethambutol for 6 months. included the conjunctival mucosa, so it is not Of the 5 birds alive at the time of this writing, 1 possible to provide more information on ulcerative was not receiving any treatment, 2 were being lesions. Topical treatments applied by the owners treated with topical medication when an erythem- or as directed by the veterinarians are believed to atous conjunctiva was noted by the owner, and 2 have altered the inflammatory response in some were actively being treated with either oral or cases with corticosteroid and antimicrobial medi- topical antibiotic therapy. Of the 2 actively being cations. treated, 1 was prescribed oral rifampin, ethambu- Mycobacteriosis identified as a conjunctival tol, and ciprofloxacin, and the other was receiving mass in cockatiel patients is an underreported but gentamicin sulfate topical eye drops and oral apparent clinical problem that practitioners should

258 JOURNAL OF AVIAN MEDICINE AND SURGERY

have knowledge of and be observant for. Although 14. Lennox AM. Successful treatment of mycobacterial

euthanasia is strongly suggested because of the in three psittacine birds. Proc Annu Conf Assoc

zoonotic nature of the disease, surgical removal Avian Vet. 2002:111–114.

with or without additional treatment was an 15. Schmidt RE, Reavill ER. Prevalence of selected

avian disease conditions. Proc Aust Assoc Avian Vet.

alternative used for some of the cases in this

2001:1–67.

report. Further controlled studies should be 16. Ramis A, Ferrer L, Aranaz A, et al. Mycobacterium

performed to determine whether other organs are genavense infection in canaries. Avian Dis. 1996;

commonly affected when a cockatiel is diagnosed 40(1):246–251.

with mycobacterial conjunctivitis. Additionally, 17. Hoop RK. Public health implications of exotic pet

determining which therapeutic options, if any, mycobacteriosis. Semin Avian Exot Pet Med. 1997;

allows for increased treatment success required 6(1):3–8.

further investigation. 18. Manarolla G, Liandris E, Pisoni G, et al. Avian

mycobacteriosis in companion birds: 20-year surv-

ery. Vet Microbiol. 2009;133(4):323–327.

REFERENCES

19. Hoop RK, Bottger EC, Ossent P, Salfinger M.

1. Schrenzel MD. Molecular epidemiology of myco- Mycobacteriosis due to Mycobacterium genavense in

bacteriosis in wildlife and pet animals. Vet Clin six pet birds. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31(4):990–993.

North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2012;15(1):1–23. 20. Gerlach H. Bacterial diseases. In: Harrison GJ,

2. Gerlach H. Bacteria. In: Ritchie BW, Harrison GJ, Harrison LR, eds. Clinical Avian Medicine and

Harrison LR, eds. Avian Medicine: Principles and Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1986:434–

Applications. Lake Worth, FL: Wingers Publishing; 453.

1994:949–983. 21. Schmidt RE, Reavill DR, Phalen DN. Special sense

3. Shivaprasad HL, Palmieri C. Pathology of myco- organs. In: Schmidt RE, Reavill DR, Phalen DN,

bacteriosis in birds. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim eds. Pathology of Pet and Aviary Birds. 2nd ed.

Pract. 2012;15(1):41–55. Ames, IA: John Wiley and Sons; 2015:263–280.

4. Mitchell MA. Mycobacterial infections in reptiles. 22. VanDerHeyden N. New strategies in the treatment

Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2012;15(1): of avian mycobacteriosis. Semin Avian Exot Pet

101–111. Med. 1997;6(1):25–33.

5. Buur J, Saggese MD. Taking a rational approach in 23. Pollock CG. Implications of mycobacteria in

the treatment of avian mycobacteriosis. Vet Clin clinical disorders. In: Harrison GJ, Lightfoot TL,

North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2012;15(1):57–70. eds. Clinical Avian Medicine. Vol 2. Palm Beach,

FL: Spix Publishing; 2006:681–690.

6. Dahlhausen B, Tovar DS, Saggese MD. Diagnosis

24. Pollock C, Carpenter JW, Antinoff N. Protocols

of mycobacterial infections in the exotic pet patient

used in treating mycobacteriosis in birds. In:

with emphasis on birds. Vet Clin North Am Exot

Carpenter JW, ed. Exotic Animal Formulary. 3rd

Anim Pract. 2012;15(1):71–83.

ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:303–304.

7. Martinho F, Heatley JJ. Amphibian mycobacterio-

25. Jacob B, Debey BM, Bradway D. Spinal intradural

sis. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2012;15(1):

Mycobacterium haemophilum granuloma in an

113–119.

American bison (Bison bison). Vet Pathol. 2006;

8. McClure DE. Mycobacteriosis in the rabbit and 43(6):998–1000.

rodent. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2012; 26. Tell LA, Leutenegger CM, Larsen RS, et al. Real-

15(1):85–99. time polymerase chain reaction testing for the

9. Pollock C. Mycobacterial infection in the ferret. Vet detection of Mycobacterium genavense and Myco-

Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2012;15(1):121– bacterium avium complex species in avian samples.

129. Avian Dis. 2003;47(4):1406–1415.

10. Lennox AM. Mycobacteriosis in companion psitta- 27. Roth A, Reischl U, Streubel A, et al. Novel

cine birds: a review. J Avian Med Surg. 2007;21(3): diagnostic algorithm for identification of mycobac-

181–187. teria using genus-specific amplification of the 16S-

11. Rupley AE. Common diseases and treatments. In: 23S rRNA gene spacer and restriction endonucle-

Rupley AE, ed. Manual of Avian Practice. Philadel- ases. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(3):1094–1104.

phia, PA: WB Saunders; 1997:270–271. 28. Chevrier D, Oprisan G, Maresca A, et al. Isolation

12. Dorrestein GM. Bacteriology. In: Altman RB, of a specific DNA fragment and development of a

Clubb SL, Dorrestein GM, Quesenberry K, eds. PCR-based method for the detection of Mycobac-

Avian Medicine and Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB terium genavense. FEMS Innunol Med Microbiol.

Saunders; 1997:255–280. 1999;23(3):242–252.

13. Hoop RK. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in 29. Robbins PK, Terrell SP, Bradway D, Wier F.

a canary (Serinus canaria) and a blue-fronted Mycobacterial infection in a fairy bluebird (Irena

Amazon parrot (Amazona amazona aestiva). Avian puella): a diagnostic conundrum. J Zoo Wildl Med.

Dis. 2002;46(2):502–504. 2009;40(1):189–192.LAMB ET AL—MYCOBACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS IN COCKATIELS 259

30. Palmieri C, Roy P, Dhillon AS, Shivaprasad HL. 40. Ferrer L, Ramis A, Fernandez J, et al. Granuloma-

Avian Mycobacteriosis in psittacines: a retrospec- tous dermatitis caused by Mycobacterium genavense

tive study of 123 cases. J Comp Pathol. 2013;148(2– in two psittacine birds. Vet Dermatol. 1997;8:213–

3):126–138. 219.

31. Washko RM, Hoefer H, Kiehn TE, et al. Myco- 41. Manarolla G, Liandirs E, Pisoni G, et al. Myco-

bacterium tuberculosis infection in a green-winged bacterium genavense and avian polyomavirus co-

macaw (Ara chloroptera): report with public health infection in a European goldfinch (Corduelis cor-

implications. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(4):1101– duelis). Avian Pathol. 2007;36(5):423–426.

1102.

42. Kiehn TE, Hoefer H, Bottger EC, et al. Mycobac-

32. Peters M, Prodinger WM, Gummer H, et al.

terium genavense infections in pet animals. J Clin

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a blue-

fronted Amazon parrot (Amazona aestiva aestiva). Microbiol. 1996;34(7):1840–1842.

Vet Microbiol. 2007;122(3–4):381–383. 43. Ledwon A, Szeleszczuk P, Malicka E, et al.

33. Brown R. Sinus, articular and subcutaneous Myco- Mycobacteriosis caused by Mycobacterium gena-

bacterium tuberculosis infection in a juvenile red- vense in lineolated parakeets (Bolborhynchus line-

lored Amazon parrot. Proc Annu Conf Assoc Avian ola). A case report. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy. 2009;53:

Vet. 1990:305–308. 209–212.

34. Hoefer HL, Kiehn TE, Friedan TR. Systemic 44. Portaels F, Realini L, Bauwens L, et al. Mycobac-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a green-winged ma- teriosis caused by Mycobacterium genavense in birds

caw. Proc Annu Conf Assoc Avian Vet. 1996:167– kept in a zoo: 11-year survey. J Clin Microbiol.

168. 1996;34(2):319–323.

35. Woerpel RW, Rosskopf WJ. Retro-orbital Myco- 45. Van Ingen J, Totten SE, Heifets LB, et al. Drug

bacterium tuberculosis infection in a yellow-naped susceptibility testing and pharmacokinetics question

Amazon parrot. Proc Annu Conf Assoc Avian Vet. current treatment regimens in Mycobacterium sim-

1983:71–76. iae complex disease. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;

36. Sevcikova Z, Ledecky V, Capik I, Levkut M. 39(2):173–176.

Unusual manifestation of tuberculosis in an ostrich

46. Lennox AM. Successful treatment of mycobacteri-

(Struthio camelus). Vet Rec. 1999;145(24):708.

osis in three psittacine birds. Proc Annu Conf Assoc

37. Stanz KM, Miller PE, Cooley AJ, et al. Mycobac-

terial keratits in a parrot. J Am Vet Med Assoc. Avian Vet. 2002:111–114.

1995;206(8):1177–1180. 47. Lennox AM, VanDerHeyden N. Antemortem

38. Murphy CJ, Kern TJ, McKeever K, et al. Ocular diagnosis and treatment of mycobacteriosis in a

lesions in free living raptors. J Am Vet Med Assoc. budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus). Proc Annu

1982;181(11):1302–1304. Conf Assoc Avian Vet. 1999:425–427.

39. Hoop RK, Bottger EC, Pfyffer GE. Etiologic agents 48. VanDerHeyden N. Avian tuberculosis: diagnosis

of mycobacterioses in pet birds between 1986 and and attempted treatment. Proc Annu Conf Assoc

1995. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(4):991–992. Avian Vet. 1986:203–214.You can also read