Police Reform - Part 1 by Mike Poteet - Conway, AR

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

volume 26, number 12 • july 19, 2020

Police Reform – Part 1 by Mike Poteet

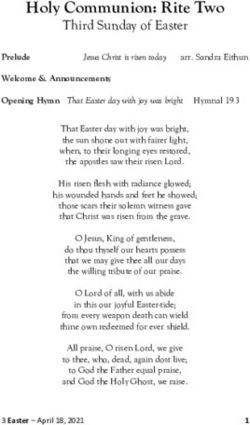

Hearing Calls for Police Reform

For weeks, protestors across the United States have been call-

ing for changes in how police officers operate. The shooting

of Breonna Taylor in her own apartment by police and the

murder of George Floyd by a police officer catalyzed the cur-

rent protests, but are only two recent incidents in a long, well-

documented, bloody history of police violence against Black

people and other nonwhite people.

According to a recent national poll, most Americans now say

they support policies to reduce police violence and change

Shutterstock.com how the criminal justice system treats officers who kill or

injure civilians. However, the question of which changes to

In the aftermath of recent protests, implement continues to spark disagreement.

many policy makers and activists are Several reform measures that can be implemented imme-

diately have gained attention in recent weeks. This issue of

calling for reforms to policing across FaithLink will discuss these proposals and their potential to

the United States. What specific effect change. Next week’s issue will explore larger, long-

term ideas and how they could transform policing as Ameri-

measures to reduce police violence

cans currently know it.

and increase police accountability

REFLECT:

have attracted attention? How effective • How would you summarize your opinion of police offi-

might these measures be? How does cers, and why?

• How, if at all, have recent events and protests challenged

our faith guide us as we consider your views about policing in the U.S.?

police reform?

Banning No-Knock

FaithLink is available by subscription via email

(subservices@abingdonpress.com) or by

Warrants and Raids

downloading it from the Web (www.cokesbury. The plain-clothes officers who burst into Breonna Taylor’s

com/faithlink). Print in either color or black and apartment on the night she died were executing a no-knock

white. Copyright © 2020 by Cokesbury.

Please do not put FaithLink on your website

search warrant. Unlike a typical search warrant, a no-knock

for downloading. 1volume 26, number 12 • july 19, 2020

warrant does not require officers to announce their the last decade, at least 134 people have died in police

presence or purpose before entering. While they are custody from “asphyxia/restraint.” Thirty-two of the

meant to be used rarely, police carry out tens of thou- victims told police, to no avail, “I can’t breathe.”

sands a year. According to Thomas Harvey of racial

Many large police departments have banned choke-

justice nonprofit The Advancement Project, officers

holds for years, and in some cases decades, but these

perform some 20,000 no-knock raids annually, “over-

bans have proven “largely ineffective and subject to

whelmingly against black and brown people.” Peter

lax enforcement,” according to National Public Radio,

Kraska, an Eastern Kentucky University professor

in part because “when chokeholds specifically were

who studies these raids, cites much higher numbers—

banned, a variation on the neck restraint was often per-

between 60,000 and 70,000.

mitted instead.” Experts agree Chauvin did not follow

No-knock warrants rapidly expanded during the late- Minneapolis police policy. The department teaches a

20th century “war on drugs.” They were intended as a “knee into shoulder blades” restraint, reserving neck

tool to preserve the element of surprise against drug restraint only for actively aggressive or resistant peo-

dealers. Yet in 36% of no-knock raids studied by the ple, and only long enough to stop the threat.

American Civil Liberties Union “no contraband of any Minneapolis has now banned chokeholds and strangle-

sort was found.” No drugs were found in Breonna Tay- holds. In his recent Executive Order on safe policing,

lor’s apartment either. President Trump financially incentivized the prohibi-

Alarming and dangerous by their very nature, no- tion of chokeholds “unless an officer’s life is at risk.”

knock raids between 2010 and 2016 resulted in the Michael Schlosser, director of the University of Illi-

deaths of at least 81 civilians and 13 law enforcement nois Police Training Institute, notes “too many people,

officers. “The war on drugs has always been predomi- especially civilians, lump [all neck restraints] into one

nantly prosecuted against minority communities,” category: the chokehold.” He distinguishes between

Kraska told Mother Jones, “so the bulk of no-knock the “blood choke” (or stranglehold) which restricts

raids are executed against those same people.” blood flow to the brain and is “relatively safe,” and the

In the weeks since Taylor’s death, the Louisville Metro “air choke,” which restricts the airway and is “consid-

Council has voted unanimously to end the practice. erably more dangerous.” He stresses officers “should

Senator Rand Paul has introduced legislation to end follow their state laws and their departmental policies

no-knock warrants nationwide. “After talking with and procedures . . . and train as much as possible.”

Breonna Taylor’s family,” he said in a statement, “I’ve But any chokehold—no matter how well-trained, how

come to the conclusion that it’s long past time to get properly applied, or how legal—fundamentally rein-

rid of no-knock warrants.” forces, on a physical and symbolic level, what George-

town law professor Paul Butler calls African Americans’

REFLECT:

perpetual second-class citizenship. “A chokehold is a

• Were you aware of no-knock warrants before the process of coercing submission that is self-reinforcing,”

Breonna Taylor shooting? Do you think they are a Butler writes in his book, Chokehold.

useful tool? Why or why not?

• To what extent does a government declaration of REFLECT:

“war” on illegal drugs contribute to unnecessary dan- • What are your thoughts on the use of chokeholds

ger for both civilians and police officers? by police? How do you think they should be used?

Should they be banned? Why or why not?

• How do you react to Professor Butler’s suggestion

Banning Chokeholds that the chokehold is an apt metaphor for the Black

Almost everyone has seen the video of Derek Chauvin experience in America?

kneeling on the neck of George Floyd for 8 minutes

and 46 seconds and ignoring Floyd’s repeated plea, “I

can’t breathe.” Many of us also recall that in 2014 Eric

Ending Qualified Immunity

Garner said the same thing while he lay pinned, face- “Trying this case will not be an easy thing,” Minne-

down on the sidewalk, his neck in a chokehold. Over sota Attorney General Keith Ellison said regarding the

Copyright © 2020 by Cokesbury. Permission given to copy for use in a group setting.

Please do not put FaithLink on your website for downloading. 2volume 26, number 12 • july 19, 2020

prosecution of the officers involved in killing George card simply because they violated your rights . . . in a

Floyd. “We’re confident in what we’re doing, but his- way that no one has ever thought of before,” attorney

tory does show there are clear challenges here.” Robert McNamara told MarketWatch. The Supreme

Court declined to review several cases related to

Police officers in the United States rarely face legal qualified immunity this term. Only Justice Clarence

consequences for using lethal force. From 2013 to Thomas dissented, citing his “strong doubts” about the

2019, 99% of killings by police resulted in no criminal doctrine.

charges. When “an officer gets on the stand and says

‘I feared for my life,’” criminal justice professor Philip Colorado recently became the first state to eliminate

Stinson told NBC News, “that’s usually all she wrote. qualified immunity, but Rashad Robinson, president

No conviction, more often than that, no charges at all.” of civil rights organization Color of Change, doesn’t

sound hopeful about broader change. He told NBC

In addition, the legal doctrine of qualified immunity News the country shouldn’t be “expecting the sys-

protects government officials, including law enforce- tem that puts black people in harm’s way to then turn

ment officers, from lawsuits alleging violations of a

around and be an effective vehicle for justice when

plaintiff’s rights. Set forth in the 1967 Supreme Court

black people are harmed.”

case Pierson v. Ray, the doctrine was meant to give pub-

lic officials acting in good faith enough latitude to per- REFLECT:

form their duties without fear of civil accountability. • Had you heard about qualified immunity before the

In recent decades the Court’s interpretation of this doc- last few weeks? If so, what did you know? What do

trine has shifted. Plaintiffs must now prove officials you think of it now?

violated their “clearly established” rights by citing a • How do you react to Rashad Robinson’s assessment

previously decided case involving the same “specific of unrealistic expectations for the nation’s justice

context” and “particular conduct.” In practice, quali- system?

fied immunity gives officials “a get-out-of-jail-free

Core Bible Passages

In Romans 13:1-5, the apostle Paul urges his readers to willingly submit themselves to governmental authori-

ties, since those authorities’ right to use “weapons to enforce the law” (verse 4) derives from God and should not

frighten those who do what is right. Paul wrote to Christians who had no say in how imperial Rome exercised

its authority, nor does he here address the question of how Christians should respond when governments enforce

laws unjustly.

We Christians claim to worship a man of color (a first-century Palestinian Jew) who unjustly suffered abuse at the

hands of, and was executed by, armed government officials (Matthew 27:27-31). We often see his fate foreshad-

owed in Isaiah’s prophecy about a “suffering servant” whose life was “taken away” by “a perversion of justice”

(Isaiah 53:8, NRSV). While the New Testament also affirms Jesus willingly accepted his unjust death as the will

of his Father in heaven, it also records his promise that those “whose lives are harassed because they are righ-

teous” would be given the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 5:10).

Jesus also stood in the tradition of Hebrew prophets who called those in power to account. In Isaiah 1:12-17, the

prophet delivers God’s command to the nation to do good and seek justice for oppressed populations. In Amos

5:14-15, the prophet suggests the nation’s behavior “at the city gate”—the public forum for justice—would deter-

mine whether God would show the nation mercy.

REFLECT:

• How should Christians in a democratic society respond when government authorities use force unjustly, or

enforce unjust laws?

• How does Jesus’ experience shape the way we view and respond to police violence?

Copyright © 2020 by Cokesbury. Permission given to copy for use in a group setting.

Please do not put FaithLink on your website for downloading. 3volume 26, number 12 • july 19, 2020

The “8 Can’t Wait” Campaign

The “8 Can’t Wait” campaign proposes eight immediate changes that it argues research has shown could reduce

police killings by 72%. These proposals cover everything from banning chokeholds to requiring de-escala-

tion efforts and using a clearly defined “use of force continuum.” The full list can be found at their website

https://8cantwait.org/.

Other activists have criticized this campaign, arguing that its claims are based on faulty data and that they are

advocating “reforms that have already been tried and failed.” On Twitter, Dwayne David Paul, director of the Col-

laborative Center for Justice, said “8 Can’t Wait” “totally obscures the demands of longtime organizers to strip

resources from police” and is “the easy way out for politicians.”

Writing for the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, Olivia Murray points out “the largest police

departments in the country already have half or more of these policies in place.” The campaign, she writes, like

“all police reform efforts,” cannot control for “one irreparable flaw: average people having the extraordinary

responsibility of policing other, average people.”

In response, “8 Can’t Wait” organizers, posted a statement on their website that reads, “While we stand by the idea

that any political leaders truly invested in protecting black lives should adopt the #8CANTWAIT policies, we also

believe the end goal for all of us should be absolute liberation from policing.”

REFLECT:

• How do the disagreements surrounding the “8 Can’t Wait” campaign reflect disagreements about the possibility

and desirability of police reform?

• What is your response to the proposals from the “8 Can’t Wait” campaign? Which would you support? Which

do you have more questions about?

United Methodist Perspective

In its Social Principles, The United Methodist Church affirms “every form of government stands under God’s

judgment and must therefore be held accountable for protecting the innocent.” It also calls on “all governmental

bodies, especially the police and any other institutions charged with protecting public safety, to provide appropri-

ate training and to act with restraint and in a manner that protects basic rights and prevents emotional or bodily

harm.” While this section focuses specifically on civil disobedience, the emphasis on “the rule of law” and “equal

access to justice for all people” suggests a desire to prevent harm from the use of excessive force.

The Rev. Dr. Sheron Patterson is senior pastor of Hamilton Park UMC, Dallas. She is also the daughter of a police

officer. “I was reared by the blue and I love the blue,” she told Fox and Friends. She remembers when police were

“heroes of the community” but condemns police brutality. “The police have been murdering African Americans

for generations,” she said. “Let me say clearly: I am pro-the blue, but I am also pro-police reform.”

The Rev. Shawn R. Moore is senior pastor at The Beloved UMC in St. Paul, Minnesota, and a former police offi-

cer. “I’ve seen the best and worst things happen within law enforcement,” he writes for UM News. “Every system

created by humans will be flawed and sinful . . . . The cross has the ability to redeem all things and all situations. It

is the cross that has the ability to remove barriers that hinder authentic relationships. The time for reform is now.”

REFLECT:

• How can we support both police officers and police reform efforts?

• What specific contributions to reform efforts can Christian faith make?

Copyright © 2020 by Cokesbury. Permission given to copy for use in a group setting.

Please do not put FaithLink on your website for downloading. 4volume 26, number 12 • july 19, 2020

Helpful Links

• Mapping Police Violence, a comprehensive statistical database of incidents of lethal use of force by

police: https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/

• “The war on drugs gave rise to ‘no-knock’ warrants. Breonna Taylor’s death could end them”:

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/the-war-on-drugs-gave-rise-to-no-knock-warrants-breonna-

taylors-death-could-end-them

• Professor Paul Butler discusses chokeholds: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kzQwcz3A80Y

About the Writer

Mike Poteet is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA)

and a member of the Presbytery of Philadelphia.

Next Week in

Police Reform – Part 2

by Alex Joyner

Along with short-term proposals for police reform, many are

also calling for us to reimagine what policing looks like. What

deeply rooted issues are inspiring these calls for change?

What are some of the ways that advocates of police reform are

re-envisioning the role of policing? How can Christian visions

of justice inform this conversation?

Follow us on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/groups/106609035052/

or at https://www.facebook.com/faithlinkconnectingfaithandlife.

FaithLink: Connecting Faith and Life is a weekly, topical study and an official resource for The United Methodist Church

approved by Discipleship Ministries and published weekly by Cokesbury, The United Methodist Publishing House, 2222 Rosa

L. Parks Blvd., Nashville, TN 37228. Scripture quotations in this publication, unless otherwise indicated, are from the Common

English Bible, copyrighted © 2011 Common English Bible, and are used by permission.

Permission is granted to photocopy this resource for use in FaithLink study groups. All Web addresses were correct and

operational at the time of publication. Email comments to FaithLink at faithlinkgroup@umpublishing.org. For email problems,

send email to Cokes_Serv@umpublishing.org.

To order, call 800-672-1789, or visit our website at www.cokesbury.com/faithlink.

Copyright © 2020 by Cokesbury. Permission given to copy for use in a group setting.

Please do not put FaithLink on your website for downloading. 5volume 26, number 12 • july 19, 2020

Opening Prayer

Holy God, you always call your people to seek justice. By your Spirit, help us see and seize ways forward

to greater justice, in our society and in our own lives. Open our minds to experiences and perspectives

we may never have considered. Open our hands and hearts to people who have suffered or still suffer

oppression. May our discussion today be only one step toward change that extends to all people the love

you have shown us in Jesus Christ.

Leader Helps

• Open the session with the provided prayer or one of your own.

• Have several Bibles on hand and a markerboard and markers for writing lists or responses to reflection

questions.

• Remind the group that people have different perspectives and to honor these differences by treating one

another with respect as you explore this topic together.

• Read or review highlights of each section of this issue. Use the REFLECT questions to stimulate

discussion.

• Recruit some participants to briefly search the internet for the latest developments on each of the reform

measures discussed in this issue, and to report what they find to the group.

• Recruit three volunteers to improvise a brief dialogue between the apostle Paul, Jesus, and either Isaiah

or Amos, drawing on this issue’s “Core Bible Passages” as a resource. What would each of these bibli-

cal figures most want to ask each other? Where might they agree and disagree? Ask participants what

other Scriptures would contribute to such a discussion.

• Close the session with the provided prayer or one of your own.

Teaching Alternatives

• Invite a police officer to participate in your discussion and to answer questions about police violence

and police reform efforts openly and honestly from their perspective. If the officer is a Christian, invite

him or her to share how faith informs his or her service.

• Invite participants to draft emails or letters to their local, state, or federal representatives in which

they express their thoughts about police reform efforts. Encourage them to make explicit connections

between their faith and their positions.

Closing Prayer

Strong and loving God, we thank you for this time together. Place the Gospel on our lips as we enter our

country’s conversations about doing justice. Place Christ’s healing power in our hands as we work to

repair wrongs we have done, or that are done in our name. Keep us watchful for ways to witness to your

coming world in the midst of this sinful one, which you nonetheless love so much you sent your only

Son, our Savior, Jesus Christ.

Copyright © 2020 by Cokesbury. Permission given to copy for use in a group setting.

Please do not put FaithLink on your website for downloading. 6You can also read