Of Homogenous 'Freaks' and Heterogenous Members: Cultural Minoritites and their Belonging in the Estonian Borderland - NEW ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Of Homogenous ‘Freaks’ and Heterogenous Members:

Cultural Minoritites and their Belonging in the Estonian Borderland

by Alina Jašina-Schäfer (BKGE, Oldenburg, Germany)

Abstract

This paper interrogates the complex manifestations of belonging among minority groups while

focusing on the narratives and spatial experiences of Russian speakers in Estonia. Engaging

critically with previous studies on belonging and drawing on the ethnographic examples from

the borderland city of Narva, this research reconstructs belonging as a complex relational

process constituted through both the official spatial arrangements and individual social

actions, meanings, and perceptions. It demonstrates how official state narratives and the

reconfiguration of space in and around Narva alienate many of its Russian-speaking dwellers

as outsiders and strangers but also, counterintuitively, lead to the emergence of numerous

alternative heterogenous representations of the self, anchored in daily interactions in and

with concrete material spaces.

Keywords: belonging, borderland, space, Russian speakers, Estonia

Introduction

This paper extends the dialogue on ethno of stationary or figurative displacement” as the

heterogenesis through a critical interrogation of political borders demarcating their homelands

the notion of belonging, which in the recent years “moved over them” (Flynn 2007: 267). This geo-

has become increasingly central to discussions of political reconfiguration implied the obliteration

ethnicity, minority integration, and socio-cultural of established orders, the redefinition of com-

change. It does so by examining the everyday munity memberships, and the transformation

practices of ‘Russian speakers’1 who found them- of Russian speakers from being considered the

selves “beached” in Estonia when the Soviet bor- rightful residents in the commonly non-Russian

ders suddenly receded (Laitin 1998: 29). Once a regions to being perceived as new minorities. To

privileged national group in the Soviet Union, the this day, especially following Russia’s contested

Russophone populations experienced “a form annexation of Crimea and the war in Eastern

Ukraine in 2014, their loyalties, attachments, and

1 The broad term ‘Russian speakers’ encompasses belonging complicate the process of post-Soviet

Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Polish and other reconfiguration of political, cultural, and social

nationalities, who had migrated to the non-Russian landscapes.

regions and became heavily Russified both during

the tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union. However,

Engaging with the peculiar case of the politi-

without wishing to essentialize certain historical, lin- cally displaced Russian-speaking minorities

guistic, and cultural commonalities between Russian in the Estonian borderland city of Narva, this

speakers, I consider the Russophone community as a

paper explores the complex manifestations of

complex phenomenon, engendering a broad variety

of narrative and performative practices articulated belonging. In recent years, there has been sus-

within a specific spatio-temporal setting. tained interdisciplinary academic scrutiny of the

NEW DIVERSITIES Vol. 23, No. 1, 2021

ISSN-Print 2199-8108 ▪ ISSN-Internet 2199-8116NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021 Alina Jašina-Schäfer

processes, practices, and theories of belong- affiliation of Russian speakers are shaped by

ing (Antonsich 2010; Anthias 2006; Halse 2018; the simultaneous entanglement of homo- and

Miller 2003; Pfaff-Czarnezka 2011; Wright 2015; heterogenizing forces. That is how they move

Yuval-Davis 2006, 2011). Heightened transna- from being framed and perceiving themselves as

tional interconnectedness, but also resurgent ‘freaks’, as put by one of my interlocutors, or non-

nationalism and conservatism have contributed Estonian strangers, to Estonian ‘rightful mem-

profoundly to questions about what belonging bers’, Estonianized Russians, and/or as essential

could mean, how belonging is experienced in dif- parts of Europe.

ferent ways, and how it might be structured by Narva represents a telling site in the study

socio-political processes. This paper addresses of local belonging and social change. Following

such questions by bringing previous critical stud- Estonia’s independence in 1991, the new bor-

ies together with my own ethnographic data derland city has been geographically marginal-

about tangible ways in which Russian speak- ized and discursively alienated from the rest of

ers experience, materialize, and narrate their Estonia. It came to connote peripherality and

belonging. internal otherness, Orientalized due to its demo-

In addition to attending to broader political graphics, location, and cultural connections with

discourses or the so-called “politics of belonging” Russia and the so-called ‘Russian World’. To date,

(Yuval-Davis 2006) which define space and soci- the city is populated predominantly by Russian-

ety, I also incorporate a micro-level analysis of speaking inhabitants (comprising over 90% of

the mundane activities and narratives of Russian- the local population), most of whom arrived in

speaking individuals, and inquire particularly into Narva during the reconstruction years following

their societal positionings, their perceptions of the end of World War II. The large flow of new-

places they live in and the desires for alterna- comers from Russia and other parts of the Soviet

tive belonging. I build on and conduct a space- Union considerably shifted the ethnic compo-

sensitive research (Fuller & Löw 2017; Savage et sition of its population, turning the city into a

al. 2003; Youkhana 2015) that looks not only at “Russian-speaking working-class environment”

different emotional articulations of belonging in (Pfoser 2017: 392), where ethnic Estonians rep-

a specific socio-political and cultural location but resent a minority. Today this demographic situa-

also at the capacity of concrete material spaces to tion stimulates much discussion into the status

facilitate the movement of people between dif- of Narva – whether, for example, Narva should

ferent memberships. As such, this detailed analy- be considered a ‘Russian enclave’, “detached

sis contributes to existing theoretical discourses from Estonian political and cultural mainstream”

on belonging, describing it as interrelated yet and capable of secession (Makarychev 2018: 9).

with “alterable attachments” (Youkhana 2015: Although the borderland city is approached

16) that come into being through simultaneous predominantly through the frameworks of secu-

spatial practices of bordering and re-bordering. ritization and marginalization, Makarychev (Ibid.)

Approaching belonging as a more fluid and notes how Narva should be studied as a “connect-

less fixed conception, as a movement between ing point”, “bridge”, and a “hybrid space” that

‘inside’ and ‘outside’ as well as between differ- integrates “a fusion of cultures and languages”

ent cultural fields, allows us to better understand (Makarychev & Yatsyk 2016: 101). As an “epis-

how the processes of ‘othering’, processes of temological frontline” between different spatial

distancing, as well as changes of ethnic framing and temporal scales of the global, national, and

and collective memberships occur. The empiri- local, Soviet, and post-Soviet (Kaiser & Nikifo-

cal sections provide, therefore, vivid insights for rova 2008: 545), Narva enables a closer look into

the current special issue on ethnoheterogenous the relationship between geographic borders

societies by demonstrating how belonging and and potential boundaries of belonging. Studying

28Of Homogenous ‘Freaks’ and Heterogenous Members NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021

the variegated practices through which Russian- is negotiated ‘intersectionally’, that is, alongside

speaking Narvans position themselves in relation multiple power axes. Floya Anthias (2006) fol-

to internal and external spaces makes visible lows a similar argument and situates belonging

how the dividing lines between and the satu- at the interface between the local and the global,

ration of different cultural codes and lifestyles between different locations and contexts from

occur, opening thereby new perspectives into which it is imagined and narrated. To under-

the broader research on borders, belonging, and stand belonging, then, is to understand a “trans-

space. locational positionality”: that is, how individual

The first part of this article situates the positionalities are “complexly tied to situation,

research in the literature on belonging, develop- meaning and the interplay of our social locations”

ing a space-sensitive definition of the concept. In (Anthias 2006: 29). This interpretation breaks

the second part, I provide a schematic account with the essentialized categorizations of social

of individual meanings and practices of belong- difference and bridges the gap between struc-

ing while drawing on the ethnographic examples ture and agency, between different localities and

gathered in the Estonian borderland city of Narva scales.

between February and April, 2017. In this analy- To fruitfully deepen understandings of belong-

sis, I focus, on the one hand, on the major recon- ing, Sarah Wright (2015) suggests a “weak theory”,

figurations of space that occurred in the bor- which neither attempts to categorize nor model

derland city following the collapse of the Soviet the lives of people. Instead, a weak theory pon-

Union as well as the official state narratives that ders belonging as constituted “by and through

often exclude Russian speakers from the Esto- emotional attachments” as well as “the practices

nian community on both formal and informal lev- of a wide range of human and more-than-human

els. On the other, I trace different ways in which agents, including animals, places, emotions,

societal positionings and alternative modalities things and flows” (Wright 2015: 392). It is, thus,

of belonging emerge and are negotiated in the a “circuit of action and reaction” (Ibid.: 393) that

so-called spatial narratives of Russian speakers emphasizes the agency of place and its co-consti-

constructed in reference to specific places. tution with people. Mike Savage et al. (2003) and

Marco Antonsich (2010) also stress the spatial

Belonging Through Spatial Lens reference of belonging, which is often related to

Although belonging has been less rigorously particular localities and territorialities. According

theorized than many other foundational terms to Antonsich (2010: 645), who builds on research

(Wright 2015: 391), there are several notewor- by Yuval-Davis, belonging may range between

thy studies that seek to make sense of ubiquity two major analytical dimensions – one that con-

and the contradictory nature of the concept by notes a personal, intimate, feeling of being ‘at

elaborating its different facets. Nira Yuval-Davis home’ (place-belongingness) and the other that

(2006), for example, suggests that belonging is refers to “a discursive resource which constructs,

a dynamic process constructed through differ- claims, justifies, or resists forms of socio-spatial

ent dimensions: individuals’ social locations that inclusion/exclusion” (politics of belonging). As

relate to a particular age-group, kinship group or such, belonging develops gradually through daily

a certain profession; individuals’ identifications spatial performances and feelings of safety while

and emotional attachment to various collectives being situated within and affected by more pub-

and groups; and discursive processes or ‘poli- lic-oriented formal structures.

tics of belonging’ that make belonging possible. There is now a growing acknowledgement that

At the center of her argument lies the perspec- belonging should be anchored in socio-material

tive that belonging is always influenced by differ- circumstances, spatialities surrounding people,

ent historical trajectories and social realities and and their everyday practices (Anthias 2013;

29NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021 Alina Jašina-Schäfer

Bennet 2012; Youkhana 2015). Eva Youkhana people’s self-positioning. Instead, this approach

(2015: 11), for example, notes how, in order to views membership roles as inherently situative

reflect upon the changing everyday belonging- within specific power relations (Tiesler 2018)

ness, socio-spatial production processes must and draws our attention to social, political, eco-

be better integrated into our conceptual think- nomic, ideological, and technological processes

ing. Belonging, in her words, could be then that define space and society. These processes

defined as “a socio-material resource that arises are usually tied with the so-called ‘politics of

my means of multiple and situated appropria- belonging’ through which both political institu-

tion processes” and describes “alterable attach- tions and the society at large create structures

ments that can be social, imagined, and sensual- and draw boundaries, shaping and encoding the

material in nature” (Youkhana 2015: 16). These built environment with meanings that affect the

attachments come into being “between people individual experiences in place. At the same time,

and things, and between people and people, it also considers the mundane, habitual activi-

through material conditions”. To stress the inter- ties and tactics (e.g. social exchanges, memories,

sectional entanglement of belonging with the images, and daily interaction in and with mate-

politics of boundary-making, Youkhana proposes rial settings) that people use to negotiate their

to use space as a useful analytical category that way through or around social structures. As an

reflects complex relations between people, cir- analytical tool, space, thus, does not overempha-

culating objects, artefacts, and changing social, size individual agency nor prioritizes ‘politics of

political and cultural landscapes (Ibid.: 10). In belonging’, but sees them as products of inher-

other words, this analytical approach gives the ent interrelation responsive to the movements

researcher an opportunity to trace not only the and specifications of time.

complex relations of individuals with other peo- Adopting a relational space-based approach,

ple but also the importance of concrete places or this paper concentrates on artefacts in public

things for the constitution of the social relations space of Narva – buildings, streets, monuments

(Halse 2018). – and their role in the processes through which

This article considers a space-sensitive theo- Russian speakers negotiate belonging within the

rization of belonging.2 Building on previous Estonian collective, transgress dominant ideolo-

research, it looks at belonging as an ongoing gies, political practices, and the politics of social

spatial process, defined by power relations boundary-making. Central to the analysis are

which shape and are shaped by practices of bor- individuals’ narratives of social relationships

dering and de-bordering. The spatial approach and belonging, emerging out of their daily rou-

to belonging, which is by its very nature rela- tines and dwelling. Instead of asking the direct

tional and dynamic, allows one to overcome questions of where and whether one belongs

many difficulties associated with problematic or feels at home, I employed naturally occurring

ideas of groupism or static attitudes towards data that arose in the conversations about the

aspects of everyday life, friendships, leisure, and

2 Following Low (2017: 32), I understand ‘space’ in favorite places. Therefore, apart from conducting

a broader sense, as a social construct, “produced by scheduled interviews, I also turned to the ethno-

bodies and groups of people, as well as historical and graphic practice of ‘deep hanging out’ (Geertz

political forces”. ‘Place’, on the other hand, is a spatial

1998; Ingold 2004), that is, sharing experiences

location inhabited and appropriated by individuals

through ascription of personal meanings and feelings in a variety of places by strolling through the city

(Cresswell 2015: 15). It is by filling spaces with social, with my interlocutors, visiting their homes, and

cultural, and affective attributes that space becomes having numerous conversations about life out-

place – a “particular space on which senses of belong-

ing, property rights, and authority can be projected” side the formal interview structures in cafes or

(Blommaert 2005: 222). bars.

30Of Homogenous ‘Freaks’ and Heterogenous Members NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021

The data used in the sections below stems side positionality turned out to be useful for

from Russian-speaking interlocutors whom I met paying careful attention to different materiali-

through a technique of a snowballing (with a ties and registering the distinctive public feelings

maximum of one subsequent referral per respon- they generate, or to the complex entanglement

dent): I encountered some people on the streets, of cultural styles which overlap, mutate, and con-

while I met others through personal contacts or dition each other (Ferguson 1999). Most impor-

through the language café, the informal meetings tantly, it helped uncover diverse, complex, and

organized by the Integration and Migration Foun- contested practices of social membership that

dation (MISA) with the purpose to help people Russian speakers were forming in the context of

improve their Estonian language skills.3 My anal- day-to-day social and spatial interactions.

ysis builds on extensive ethnographic observa-

tions, visual materials, or photographs of favorite Spatial Reconfiguration of Narva: Producing a

places that my interlocutors shared with me, as Community of ‘Freaks’

well as twenty-seven semi-structured interviews Wider socio-spatial contexts serve as a backdrop

that took place in the Russian language with the against which to interpret individual and group

city-dwellers between eighteen and sixty-six encounters as well as their feelings of belonging.

years old. These individuals represented a range Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the

of professional backgrounds with different levels process of nationalization in Estonia has become

of education and varying degrees of engagement pervasive, with the state conducting wide-

in civic activities: some were university students, ranging campaigns to reassert national identity

while others were teachers, engineers, lawyers, and sovereignty. The agenda of nation-building

shop assistants, housewives, unemployed work- aimed in particular at an impetuous departure

ers, or pensioners. from the Soviet past, at revising and reifying

My ethnographic findings of everyday belong- national narratives, at reasserting the language,

ing equally combine immersion with estrange- demographic position, economic flourishing and

ment, my own interiority as a Russian speaker political hegemony of the nominally state-bear-

from Estonia, and my exteriority as a person from ing nation (Diener & Hagen 2013). The efforts

Tallinn who entered into the urban environment to create specific cultural and political narra-

of Narva for the first time. Establishing contacts tives were reflected in two specific ways: First,

with the local dwellers was not a difficult task, as with the creation of a citizenship policy, which

many responded positively to my own heritage, excluded as non-citizens everyone who moved

taking me as one of their own, as someone who to Estonia after 1940 (initially comprising 39% of

not only understands the language, but is situ- the total population). Second, through language

ated in the same socio-political context. At the and education laws, which sought to prioritize

same time, I had to compensate for my ‘spectral the Estonian language and version of history.

distance’ with a lot of explorative strolls to sense At the same time, the national revival crystallized

the intensities of everyday affective cityscapes, spatially in the urban landscapes through the

to discover the Geist of Narva. This inside/out- replacement of the street names, the creation of

historical landmarks that commemorate specific

3 The several meetings that I observed were at- national narratives while forgetting or trivializing

tended by a very broad spectrum of Russian-speaking

people: pensioners (who sought a company of others

the narratives of local minorities as those of the

rather than necessarily learning the language itself), undesirable past.

mothers on maternity leave and unemployed people This nationalization was acutely felt in Narva,

(who wanted to use their time effectively and improve

where the Russian-speaking inhabitants were

their Estonian), as well as several current employees

(who were required by their employers to pass the forced to deal with a new physical border while

language qualification test). observing how many of their previous practices

31NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021 Alina Jašina-Schäfer

came abruptly to a halt. A large-scale de-Sovi- The Gerasimov Culture House, I cannot look at it

etization campaign was launched to exteriorize without tears in my eyes. It is a wreck; even the

Russia and Russianness from the time-space of windows are all knocked out. Nothing is left of this

place. Once, this culture house used to be sur-

Narva, replacing it with Estonian and European

rounded by a beautiful park with fountains, full of

narratives instead. During this process, not only kids. All parades and celebrations in the city used

several Soviet-era monuments were eliminated, to take place there, on the ninth of May, the first

but also the street names, names of buildings, of May. Numerous cultural events, gymnastics and

schools, or cultural landscapes of the city. The music classes all used to happen at Gerasimov.

There was life and there was real movement. What

first monuments to be demolished were those

we see now is a few shabby columns and slowly,

of Lenin. The main statue, which is the last of quietly corroding swings of the demolished amuse-

its kind in Estonia, was relocated from the city ment park.

square to the yard of the Narva Fortress, built

during Denmark’s rule in the thirteenth century. Attempts to integrate Narva into Estonia and

Stripped of its former powerful position today it to introduce the Estonian language and culture

serves rather as a “kitschy local tourist attraction through the education system or cultural events

metaphorically captured and subordinated to and festivals thus border uncomfortably with the

Europe” (Kaiser & Nikiforova 2008: 549). visible distortion or even erosion of the public

This radical transformation affected the city spaces.4 This distortion comes alongside coun-

in other ways, as well. The disappearance of terproductive narratives that reconstruct the city

familiar cultural geographies through creation as a separate kind, as “not quite Estonian” (Pfoser

of new symbols and narratives coupled with the 2017: 397). For example, Katri Raik, the former

corrosive political project, which left old facto- director of Narva College and a current member

ries, culture houses, and parks to decompose. of the Estonian parliament, wrote a book ten-

The Krenholm area, which was once the liveliest derly named Minu Narva (My Narva) in which

part of the city with own library, house of cul- she attempts to overcome the negative images

ture, hospital, schools, kindergartens, and hous- often attached to the city. In a thrilling manner,

ing for the factory workers, “the centerpiece of Raik describes her positive impressions of the

proletarian internationalism” (Kaiser & Nikifo- everyday life in Narva but slips almost simultane-

rova 2008: 549), has undergone the most dev- ously to reproduce the stereotypes and ostracize

astating decline. Once the largest textile factory the city as “neither Estonian nor Russian” but

of the Russian Empire and a space for employ- rather Soviet (2014: 28), as a place with its own

ment during Soviet times, Krenholm could be way of governing (politika na narvskii maner), as

now regarded as an artefact of hardships that a place where the people think of Russia as their

the city has endured since the early 1990s. What homeland (Ibid.: 26).

is left of it are ruins which mark growing state This book was mentioned to me by several

disengagement while transmitting a sense of of my interlocutors, who were convinced that

marginality for its population. In my conversa- it does not do justice neither to the city nor to

tion with Sveta, a thirty-four-year-old housewife, them. Rather, it strengthens the perception of

she remarked how the 1990s have dramatically Narva as an adjacent element that consists of

affected the city and the lives of the people. Born foreign people:

in the Krenholm area, where she also spent most

of her childhood, Sveta is upset by the negli-

4 Note that Ida-Viry County, of which Narva is a part,

gence of favorite places, which today represent a

has the highest registered unemployment rates (9.2%

rupture between a good life of Soviet prosperity

in 2020) in the country. See, for example: https://

and a present decline, economic insecurities and news.err.ee/1025237/more-job-seekers-in-ida-viru-

unemployment: county-are-finding-work-away-from-home.

32Of Homogenous ‘Freaks’ and Heterogenous Members NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021

Very little attention is paid to us. Neither politicians The interaction with fellow ethnic Estonians

nor people know much about us. This is not to say who often demonstrate unwillingness to accept

that we are a separate world. No. We pay taxes Russian speakers as ‘own people’ complicates

and everything that happens in Estonia affects us

the situation further. In a conversation, Vera,

in the same way. Narvans want to be accepted. It’s

like every family has a freak and we are this freak a forty-year-old social worker, expressed her

(v semye ne bez urodov i etim urodom okazalis’ my). unease with not being considered a legitimate

This is upsetting. And when Estonians say like we part of Estonian community, which was related

are not Estonia . . . How come? At least geographi- strongly to her lack of knowledge of the Estonian

cally. Yes, we are Estonians, Estonia … not Estonians,

language. Vera was born in Soviet Estonia and

but Estonia. And a lot of Narva dwellers, simple

workers, working in factories or in shops, they val- welcomed its independence in 1991; she consid-

ue Estonia and love living here. (Yulia, twenty-four ers the country her only homeland. She learned

years old, student) the Estonian language, attends different events

For Russian speakers like Yulia, the de-construc- in Estonian across Narva, but the feeling of being

tion and temporal ruptures that the city experi- a foreigner never subsides. Such boundaries that

ences are not seen as their own failures to adapt demarcate Estonia’s ‘own people’ from Russian-

to the new realities in the country – as it is com- speaking non-belongers feed further into the

monly framed by political and medial discourses homogenous images of Narva as a “mentally

(Malloy 2009). Instead, it is depicted as a deliber- imagined place, a small fatherland” separated

ate attempt of the state to abandon the city and from the rest of Estonia (Zabrodskaya & Ehala

position Russian speakers as ‘other’. This feeds 2010). But with every separation, as I demon-

largely into the feelings of alienation, often self- strate below, comes also a new connection. In

induced, as a seemingly homogenous Russian- other words, as much as boundaries separate,

speaking community of ‘freaks’ (urody) who are they simultaneously enable space for transgres-

estranged from the larger Estonian collective. sion and a reconfiguration of one’s own repre-

Another interlocutor, Natalya, a museum worker sentations in multiple heterogenous ways.

in her fifties, also talked to me at length about

the internal ‘otherness’ of Narva and its dwell- Heterogenous Belonging: Re-Assembling Narva

ers. In our conversation, she reconstructs the as a Plural World

painful decline of Narva from a hardworking city The Tank – A Place of Russian Alterity

into the ‘city of beggars’ where everyone, includ- The widespread campaign of nationalization

ing herself, must change jobs on a regular basis and naturalization of Estonian national narra-

and then wait for their employers to eventually tives eliminated numerous Soviet commemora-

pay them. They become a kind of problem child tive sites across Narva. Although the memorials

for Estonian politicians: ‘But we didn’t come to the victory of the Red Army in World War II,

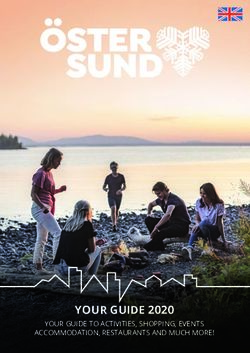

up with this life. And now Estonia can’t stand such as the ‘Tank T-34’ (Fig. 1), were not physi-

Ida-Virumaa. It is like an ulcer on the Estonian

body (yazva na tele Estonii)’. As a stateless per- the Soviet Union, the citizenship law, adopted in 1992,

helped to disenfranchise large groups of the popula-

son, Natalya feels particularly affected by these tion by denying Soviet era settlers and their descen-

changes. Despite being born here and paying her dants citizenship rights and forcing them to undergo

taxes, she confessed later, Estonian official citi- strict naturalization process. Note, however, that the

number of stateless people has dropped from over

zenship and integration policies only exacerbate 30% in 1992 to approximately 6.1% in 2016. This is

her alienation and impede a sense of belonging primarily because stateless people have decided to

to the Estonian nation-state.5 undertake ‘naturalization’ or have, instead, acquired

Russian citizenship. For more on the relationship

between citizenship and belonging in the context of

5 Based on the idea of legal continuity of the Esto- Estonia see Jašina-Schäfer & Cheskin (2020) or Nim-

nian Republic of 1918-1940 and illegal occupation by merfeldt (2011).

33NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021 Alina Jašina-Schäfer

Figure 1: Tank T-34. Photograph by Alina Jašina-Schäfer, July 2020.

cally removed, numerous state efforts have been him personally a reservoir of his childhood mem-

made to redefine their meanings from a symbol ories and his Russianness:

of liberation from fascism to monuments mark-

If I ever leave, I will miss my tank. The tank is the

ing victimhood and suffering of the Estonian peo- best thing that we have here. When I was a child,

ple at the hands of the Soviet aggressor. Despite we would often go by bus with the kindergarten

the efforts to dispose of the undesired historical group to Ust’ Narva and drive past the memorial.

narratives, many of my interlocutors highlighted Lucky were the ones who were sitting next to the

window and could see the tank. So really this goes

the importance that the Tank has retained as a

back to my childhood. And if you sat at the wrong

place of remembrance, representing a durable side of the bus, you would be considered a loser for

form of the past that bears its mark on people’s the rest of the day. Well, in general, I think every

lives. Narvan associates their life with this tank. People

Located on the outskirts of the city, the tank even come here for weddings, it is a must, a tra-

dition. […] The tank symbolizes history, different

has been the gathering point during the celebra-

battles that took place here. Narva suffered a lot

tions of the Victory Day on the ninth of May during the war, it was almost completely destroyed.

when people come to lay flowers and honor the Everyone here knows this tank. I think it contains

memory of the fallen soldiers. The act of remem- some kind of Russianness; I mean, I haven’t seen

bering occurs also on a more mundane basis Estonians coming here. It is rather the monument

that symbolizes the Russian nation, especially for

when people retell the monument’s history or

those who fought in the war and those who lived in

directly demonstrate it to the city visitors like the Soviet Union. But I might be mistaken.

myself. Artur, a thirty-nine-year-old IT-specialist

is, for example, convinced that the tank bears a As such, for people like Artur, the tank highlights

very symbolic meaning in Narva, representing to the gap between socialist and post-socialist visual

34Of Homogenous ‘Freaks’ and Heterogenous Members NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021

representations of the city. It serves as cultural of the Soviet past for their present experiences.

heritage that projects the heroic involvement Rather, it is to complicate our understanding of

of Russian people in World War II as opposed the socialization environment within which indi-

to the official state narratives of repression and viduals move and interact. Already in 2003, opin-

occupation. But it is also a material historical wit- ion polls indicated that Russian speakers started

ness that helps cementing the spatio-temporal to increasingly value globalizing popular and con-

continuity of Russian speakers embedded in the sumer culture which opens possibilities for new

Soviet past as opposed to ruptures and disconti- cultural styles to emerge (Lauristin and Viha-

nuity promoted by the agenda of nation-building. lemm 2009). In the process of dwelling rooted

The continuity emerges not only through the in Estonia and Europe comes a change in their

celebration of the ninth of May, but especially social and political ideas, activities and behav-

through the repetitive performance of the wed- iors, whereby we witness how ‘being Russian’

ding routes in the city – a custom that has its becomes highly heterogenous – attached to and

roots in Soviet times. As a traditional wedding detached from Russia, attached to and detached

location, Artur recalls later, the tank still attracts from the memories of the Soviet past.

newlyweds to pose for pictures and tie ribbons

around the cannon as a symbol of a family as The College as Architect(ure) of New Sociability

strong as the armor. The ability to perform heterogenous ‘Russian

For Artur, the tank is an eloquent memorial, culture’ around spaces like the tank does not

a symbol of communal Russianness grounded necessarily help Russian speakers overcome the

in historical narratives of continuity. For oth- perception of Narva as a space mentally divorced

ers, however, it can be an overlooked location from the rest of Estonia and Estonians. This much

that remains invisible in everyday life. Especially desired transgression of alterity, as many of my

those born in independent Estonia seem to rely interlocutors noted, occurs rather in a different

less and less on the Soviet World War II memories space, a space imagined as inclusive for all dwell-

as a marker of Russianness, redefining thereby ers of the city and beyond. It is a future-oriented

the meanings of it altogether. Yulia noted to me, space that does not attempt to mend the past

for example, that she has many friends who do narratives, which in the context of Estonia are

not associate themselves with anything Soviet still painfully disjointed, nor rejects or trivializes

and even less so with Russia: ‘There is no place the narratives of Russian-speaking minorities.

for them in Russia, they don’t have their Rus- Instead, it is determined to create unity based on

sian culture [as in culture of Russia]. Many don’t progressive thinking and common interests.

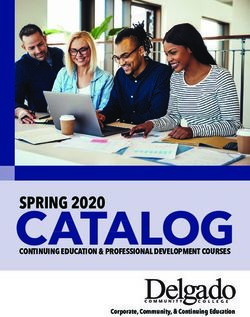

celebrate Russian holidays. Don’t talk about the A newer building of Narva College (Fig. 2),

victory day, what it is. Don’t lay flowers next to which opened in 2012, is in many ways the object

the tank. This is a different generation’. Indeed, of such a hopeful outlook. It is situated at the

I went with the younger interlocutors to the heart of Narva’s no-longer-existing old town and,

nearby city of Narva-Jõesuu on several occasions, through its peculiar design and location, entan-

and we simply drove past the monument with- gles different temporalities and spatialities: the

out even making a stop or uttering a word about façade is filled with the elements that pay hom-

it. The tank solitarily stood on the roadside as we age to the demolished stock exchange building

rushed towards the abundant cafés, spas, and of the baroque Narva, representing city’s long

parks in Narva-Jõesuu. and unique history within Estonia; it has both

The departure from the Soviet/Russian of a café called Muna (egg) and egg-shaped fur-

which Yulia speaks does not necessarily strip niture, which are elements that symbolize the

Russian speakers of their ‘Russianness’, nor beginning of a new life in Narva. The building

should this example suggest the insignificance also celebrates its borderland location, whereby

35NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021 Alina Jašina-Schäfer

Figure 2: Narva College. Photograph by Alina Jašina-Schäfer, July 2020.

two separate wings stand for the cities of Narva between the Russian- and Estonian-speaking

and Russia’s Ivangorod, and the gutter repre- worlds. Whereby the building and people inside

sents the river Narova that today separates the of it turned, even if for one night, into an ‘open

two cities. society’, a spatial counterpart to forms of social

The college is not only open for students, but exchange on the outside.

hosts numerous public events, jazz nights, book My interlocutors, of varying ages and profes-

clubs, memory games, in both Estonian and Rus- sions, often come to hang out at the college. For

sian languages. These events are equally acces- example, a sixty-six-year-old pensioner named

sible to locals and outside visitors. For example, Raisa thought Café Muna would be an excellent

the memory games, in which I too actively par- start for our explorative stroll around the city.

ticipated, take place at the café with a relaxing Many others would agree, as they understood

atmosphere, which encourages mingling and the café, and the college in general, to be a place

socializing between different people, such as where the feeling of being a foreigner disappears

Estonian and Russian speakers, and older and As put by forty-year-old Vera:

younger generations alike. Drinks are sold at

When the new college was opened, I realized im-

the counter, the questions are asked in two lan- mediately that I wanted to study here even de-

guages, and the tables are located close enough spite my age, which is not so good for education

for communication to extend beyond one’s own (laughs). So, I fulfilled my dream and came here to

group. When, by the end of the evening, a man study. […] Narva College is the only place here in

the city where I hear the Estonian language, and

with an Estonian accent eagerly proclaimed–

I am very happy about it. It is like an immersion

my pobedim (‘we will win’ in Russian), you with Estonian for me.

could clearly sense the erasure of boundaries

36Of Homogenous ‘Freaks’ and Heterogenous Members NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021

It is a place that offers an abundance of oppor-

tunities to generate new friendships, as noted by

Vova, a student in his twenties:

There is a lot happening in the college. A jazz club

takes place twice a month, and the locals come for

the jazz. Various meetings with politicians, minis-

ters and significant people in the city are being held

here too. The idea behind it is to meet, to think and

to work together. The last event I remember was

organized by the Narva Youth Centre regarding the

student self-governance in schools. Back then a lot

of student representatives from the whole Estonia

came here. Even Töötukassa (state unemployment

insurance fund) holds events in here. Sometimes I

come to study and can’t even enter the place be-

cause of some event taking place.

As such, the structure and internal operation of

the college make room for those whose opinions

remain marginal to the Estonian mainstream.

They seem to enable equal participation, break

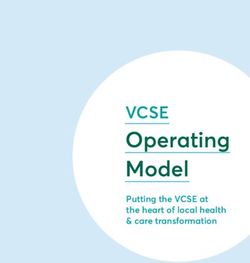

down the ethno-hierarchy still prevalent out- Figure 3: The River Promenade. Photograph by Alina

side of the building, and help Russian speakers Jašina-Schäfer, July 2020.

to overcome the tacit exclusions sedimented

through the project of nation-building. The col- attend open-air concerts and other events (Fig. 3).

lege and the people interrupt the ‘normal’ order The promenade is a long pedestrian street along

of space and become the architects of new the river embankment and as such represents

sociability in which both Russian and Estonian “the basic unit of public life in the city” (Tonkiss

speakers are essential to the Estonian commu- 2005: 68). While it might seem to be less about

nity. Such sociability does not only exist within direct sociability and encounter between people,

the walls of the college but spreads slowly across it too is subject to different uses and meanings.

the city with different smaller and bigger local Located in the immediate vicinity of the border

initiatives taking place. Be it through building to the Russian Federation, the Promenade rep-

collectively the “Bench of Reconciliation” or par- resents the fusion of distinctive “cultural styles”

ticipating together in the campaigns to make the (Ferguson 1999): Estonian, European, Russian,

borderland city the next capital of culture, locals and ‘local’. Each of these styles has been natural-

continue reconfiguring Narva from a foreign ized through everyday use, and each intersects

space into a space ‘suturing’ different histories and reconfigures the other. On the one hand, the

and cultural styles. medieval ensemble of the Narva tower signifies

to Russian speakers the long history of Narva

The Multilocal River Promenade in Estonia, whereby having personal childhood

Another important location where I often went memories of it and interacting with it helps to

with my Russian-speaking interlocutors was the strengthen one’s own sense of belonging to a

River Promenade. Recently revamped with the larger Estonian collective:

help of the money from the European Union

I will tell you now one of my school memories. We

(EU), it is now one of the local population’s favor- travelled a lot with my class. We went to Moscow,

ite places, where they take their children to the to St. Petersburg. I liked it everywhere. But there

playground, do outdoor sports, take a stroll, or is this turn to Narva, when our castle becomes vis-

37NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021 Alina Jašina-Schäfer

ible. When the bus would turn, and you would see Invoking this array of spatial narratives, Rus-

the Hermann Tower. I would immediately tear up – sian speakers clearly expose the limits of the

this is rodnoe (native space), this is my home. And I

‘nationalizing state’ that feeds off their otherness.

would say: I am finally home. (Nadezhda, forty-five

years old, kindergarten teacher) Instead, they move between multiple heterog-

enous memberships and reconstruct themselves,

On the other hand, the promenade represents often against the geographical and cultural space

the symbol of European power – it is a place of Russia, as different but quintessentially Esto-

where the European Union (EU) starts. Walk- nian and European.

ing along the ‘European’ alley, illuminated by

twenty-eight lamps each symbolizing a member Conclusion

of the EU, Dmitrii, a local businessman in his In a context of a highly transnational, fluid, and

forties, pointed to the other side of the river, to fragmented world, belonging remains a fun-

the small and, in comparison to Narva, rather damental resource that defines the quality of

unspectacular promenade of Russia’s Ivangorod everyday life. Drawing on the narratives and

and its semi-ruined castle. The striking differ- spatial experiences of Russian speakers in the

ence between two cities that were separated by Estonian borderland city of Narva, the aim here

the river helped Dmitrii to demonstrate cultural was to disentangle or, at least, to begin to bet-

superiority of Narva over Russia and its clear ter understand the meanings that belonging

belonging to a geocultural space of ‘Europe’: connotes to minorities situated within specific

power relations and socio-political contexts. The

Life in Russia is savage […]. You stand out there

and see Russian river promenade and think – oh, case of Narva adds, as such, further empirical

hell with it. Ours is much better, and this plays an insights into the conceptualization of belonging

important role. […] Why should I go there? Should as a complex ethnoheterogenous process consti-

I look at their architecture that was built by their tuted relationally through official spatial arrange-

grandads? Well, the grandads were fine fellows

ments, on the one hand, and individual social

and not the new generation of Russians that is un-

cultured. action, meanings, and perceptions, on the other.

Being once a prosperous Soviet industrial city,

The non-belonging of Russian speakers to Russia in this paper I vividly showed how Narva has suf-

based on their Europeanness was noted also by fered dramatic re-scaling into a foreign space that

Yulia: occurred under the influence of state nation-

alization policies. This re-scaling, in turn, led to

When I went to visit my relatives in Bryansk [a city

in Russia], I understood how different we are. They the emergence of seemingly bounded notion of

are so…The guys there are like Russian fairy-tale belonging that relies on imposed conceptions of

figure of Ivan the Fool. They don’t buckle up, don’t collective identities reproduced to homogenize

wear light reflectors, don’t look around before Narvan Russian speakers as outsiders who have

crossing the roads. I think it is my Europeanness

seemingly no place in the new Estonian social

that speaks now. Careless, this word describes Rus-

sians well. It permeates everything – the driving, order. However, the destabilization of social

their attitude to life, their relationship to family. In codes and previous daily experiences, I contend,

Europe we began to appreciate that parents spend also meant the emergence of numerous alterna-

time with children and pay attention to teenagers. tive heterogenous representations of the self and

In Russia, they are far from there. Schools are dif-

the meanings of one’s own belonging. As such,

ferent. We went to a university in Pskov for a lec-

ture, told them how old we were, and they treated the world of Narva was and continues to be built

us like little unreasonable children. It infuriated us, anew as a space that bridges different histories

but it suits their students. You come back to Narva and cultural styles, and moves between different

and think, Lord, where was I … in some wilderness versions of Estonianness, Russianness, and Euro-

or something?

peanness. What understandings Narvan Russian

38Of Homogenous ‘Freaks’ and Heterogenous Members NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021

speakers develop of their cultural location, and INGOLD, T. 2004. “Culture on the Ground: The

how they constitute socio-cultural, political, and World Perceived Through the Feet”. Journal of

geographical distinctions depend in many ways Material Culture 9: 315-340.

JAŠINA-SCHÄFER, A. and Cheskin, A. 2020. “Hori-

on their intersecting, though this is not reducible

zontal Citizenship in Estonia: Russian speakers in

to each other’s social positioning. Thus, in order

the borderland city of Narva”. Citizenship Studies

to be able to extend our understanding of every- 24 (1): 93-110.

day bordering practices and belonging, future KAISER, R. and Nikiforova, E. 2008. “The Periphery

research should be more cognizant of these of scale: the social construction of scale effects

broader social hierarchies and their effects upon in Narva, Estonia”. Environment and Planning 26:

ideas and behaviors among Russian speakers in 537-562.

particular and minorities in general across space LAITIN, D. 1998. Identity in Formation: the Russian-

and time. speaking population in the Near Abroad. Lon-

don: Cornell University Press.

LAURITSIN, M. and P. VIHALEMM. 2009. “The Po-

litical Agenda During Different Periods of Esto-

References

nian Transformation: External and Internal Fac-

ANTHIAS, F. 2006. “Belonging in a Globalizing and

tors”. Journal of Baltic Studies 40: 1-28.

Unequal World: rethinking translocations”. In:

LOW, S. 2017. Spatializing Culture: The Ethnogra-

N. Yuval-Davis, K. Kannabiran and U. Vieted eds.,

phy of Space and Place. London: Routledge.

The Situated Politics of Belonging, 17-31. Lon-

MAKARYCHEV, A. 2018. “Narva as a Cultural Bor-

don: Sage Publications.

derland: Estonian, European, Russophone”. Rus-

–––. 2013. “Identity and Belonging: Conceptualiza-

sian Analytical Digest 228 (30 November 2018):

tions and Political Framings”. KLA Working Paper

9-12.

Series, 8: 1-22.

MAKARYCHEV, A. and A. YATSYK. 2016. Celebrat-

ANTONSICH, M. 2010. “Searching for Belonging –

ing Borderlands in a Wider Europe: Nation

An Analytical Framework”. Geography Compass

and Identities in Ukraine, Georgia and Estonia.

4(6): 644-659.

Baden-Baden: Nomos.

BLOMMAERT, J. 2005. Discourse: A Critical Intro-

MALLOY, T. 2009. “Social Cohesion Estonian Style:

duction. Cambridge University Press.

Minority Integration Through Constitutionalized

CRESSWELL, T. 2015. Place: An Introduction. Wi-

Hegemony and Fictive Pluralism”. In: T. Agarin

ley-Blackwell.

and M. Brosig eds., Minority Integration in Cen-

DIENER, A., C. and Hagen, J. 2013. “From social-

tral Eastern Europe: Between Ethnic Diversity

ist to post-socialist cities: narrating the nation

and Equality. Amsterdam: Rodopi B. V.: 225-256.

through urban space”. Nationalities Papers

MILLER, L. 2003. “Belonging to country – a philo-

41(4): 487-514.

sophical anthropology”. Journal of Australian

FERGUSON, J. 1999. Expectations of Modernity:

Studies 27(76): 215-223.

Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambi-

NIMMERFELDT, G. 2011. “Sense of Belonging to

an Copperbelt. LA: University of California Press.

Estonia.” In: R. Vetik and J. Helemäe, eds., The

FLYNN, M. 2007. “Renegotiating Stability, Security

Russian Second Generation in Tallinn and Kohtla-

and Identity in the Post-Soviet Borderlands: The

Järve, the TIES Study in Estonia. Amsterdam: Am-

Experience of Russian Communities in Uzbeki-

sterdam University Press: 203-29.

stan”. Nationalities Papers 35(2), 267-288.

PFAFF-CZARNECKA, J. 2011. “‘From ‘identity’ to

FULLER, M. G. and Löw, M. 2017. “Introduction: An

‘belonging’ in social research: plurality, social

Invitation to spatial sociology”. Current Sociology

boundaries, and the politics of the self”. Work-

65(4): 469-91.

ing Papers in Development Sociology and Social

GEERTZ, C. 1998. Deep Hanging Out. The New York

Anthropology 368: 1-18.

Review of Books.

PFOSER, A. 2017. “Narratives of peripheralisation:

HALSE, C. 2018. “Theories and Theorizing of Be-

Place, agency and generational cohorts in post-

longing”. In: C. Halse ed., Interrogating Belong-

industrial Estonia”. European Urban and Region-

ing for Young People in Schools, 1-28. Switzer-

al Studies 25(4): 391-404.

land: Palgrave Macmillan.

39NEW DIVERSITIES 23 (1), 2021 Alina Jašina-Schäfer

RAIK, K. 2014. Moia Narva: Mezhdu dvukh mirov, WRIGHT, S. 2015. “More-than-human, emergent

translated by E. Rutte and K. Verbitskaia, Estonia: belongings: A weak theory approach”. Progress

Petrone Print. in Human Geography 39(4), 391-411.

SAVAGE, M., G. BAGNAL, and B. LONGHURST. YOUKHANA, E. 2015. “A Conceptual Shift in Stud-

2003. Globalisation & Belonging. London, Thou- ies of Belonging and the Politics of Belonging”.

sand Oaks, New Delhi: SAGE Publications. Social Inclusion 3(4): 10-24.

TIESLER. N. C. 2018. “Mirroring the dialectic of YUVAL-DAVIS, N. 2006. “Belonging and the politics

inclusion and exclusion in ethnoheterogenesis of belonging”. Patterns of Prejudice 40(3): 197-

process”. In: S. Aboim, P. Granjo, A. Ramos, eds., 214.

Changing Societies: Legacies and Challenges. –––. 2011. The Politics of Belonging: Intersectional

Vol. 1. Ambiguous Inclusions: Inside Out, In- contestations. London, Thousand Oaks, New

side In, 195-217. Lisbon: Imprensa de Ciencias Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Sociais. ZABRODSKAYA, A. and M. EHALA. 2010. “Chto

TONKISS, F. 2005. Space, the City and Social Theory. dlya menya Estoniya? Ob etnolingivstichekoi

Malden: Polity Press. vitaln’nosti russkoyazychnyh”. Diaspory 1: 8-25.

Note on the Author

Alina Jašina-Schäfer holds a PhD in Cultural Studies from the Justus Liebig University Giessen,

where she explored spatial belonging of Russian speakers in the borderland areas of Estonia and

Kazakhstan. Currently she is a post-doctoral fellow in a project on “Soviet Ambivalence” at the

Federal Institute for Culture and History of the Germans in Eastern Europe (BKGE) where she

conducts research into everydayness and the life trajectories of German minorities in the Soviet

Union.

Email: Alina.JasinaSchaefer@bkge.uni-oldenburg.de.

40You can also read