Neuroparenting: the Myths and the Benefits. An Ethical Systematic Review

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Neuroethics

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-021-09474-8

ORIGINAL PAPER

Neuroparenting: the Myths and the Benefits. An Ethical

Systematic Review

Anke Snoek · Dorothee Horstkötter

Received: 8 April 2021 / Accepted: 15 August 2021

© The Author(s) 2021

Abstract Parenting books and early childhood encounter. In the last decade, parenting advice based

policy documents increasingly refer to neuroscience on neuroscientific evidence has become so popular,

to support their parenting advice. This trend, called that some speak of neuroparenting [1]. Neuroparent-

‘neuroparenting’ has been subject to a growing body ing is a parenting style where neuroscientific insights

of sociological and ethical critical examination. The are used to improve parenting, and thereby to foster

aim of this paper is to review this critical literature on child development. The idea behind it is twofold: 1)

neuroparenting. We identify three main arguments: neuroscientific evidence can provide essential insights

that there is a gap between neuroscientific findings in how parental choices can positively or negatively

and neuroparenting advice, that there is an implicit influence child brain development, 2) Knowledge

normativity in the translation from neuroscience to about children’s brain development allows parents to

practice, and that neuroparenting is a form of neolib- adjust their parenting to their child’s developmental

eral self-management. We will critically discuss these stage [1, 2]. Examples of neuroparenting range from

arguments and make suggestions for ethically respon- the advice to stimulate your newborn’s brain devel-

sible forms of neuroparenting that can foster child opment by reading or breastfeeding [3] to parenting

development but avoid pitfalls. books on the ‘teenage brain’ to support parents in

managing adolescents’ lack of self-control [4].

Keywords Neuroparenting · Parenting · This emerging trend of neuroparenting fits into a

Neoliberalism · Early childhood policies · Ethical broader development of the neuroscientification of

review · Child development the discourse on child and youth development [5]. It

can be observed in both popular parenting books as

in policy documents on how to support child develop-

Introduction ment [6].

The rise of neuroparenting has also triggered an

Many parents seek advice, to determine how to best engaged and critical social and ethical discussion

raise their children or deal with challenges they regarding its implications on child development, on

parent–child relationships, and on identity. To date,

a stalemate seems to have emerged between those

A. Snoek (*) · D. Horstkötter who aim to invoke neuroscientific research for parent-

Department of Health, Ethics and Society (HES), ing and parenting support and those who are critical

Maastricht University, Metamedica, Postbus 616,

about this endeavor. This stalemate leads to a situation

6200 MD Maastricht, Netherlands

e-mail: A.snoek@maastrichtuniversity.nl where neuroscientific findings get either over-claimed

Vol.:(0123456789)

13A. Snoek, D. Horstkötter

in their practical usability or abandoned altogether as Field Analysis: Age Groups, Aims, Dissemination

a source of insight. In order to overcome this stale- and Methods

mate, the current article will review the sociological

and ethical literature on neuroparenting. The aim is to We found that the critical sociological and ethical lit-

identify and evaluate the reasons that have been given erature uses diverse methodologies, focussed on the

for and against the practice of neuroparenting. different ways in which neuroparenting advice is dis-

seminated, and focused on different age-group with

different intervention aims. This analysis resulted in

Method the following field map (Fig. 2).

Neuroparenting advice – and hence the critical

Systematic reviews are comparatively new to ethics literature – focuses on three age groups: 1) the ‘first

studies, but provide a particularly powerful way to three years’, measured from conception, 2) young

systematically identify, analyze and synthesize nor- children in general, and 3) adolescents [4, 9–11]. For

mative argumentation [7, 8]. We conducted a search these age groups, different overlapping neuroparent-

of relevant keywords on 2 nd February 2020 in Google ing aims were identified. Regarding children’s early

scholar, Pubmed, Psycinfo, Philpapers, and Jstor. We years, the main focus is on improving social-emo-

started with the rather broad term ‘neuroparenting’, tional development, mediated by adequate bonding

and continued the search using ‘brain-based parent- and love, and on optimizing cognitive development

ing’ as an alternative, because several search engines and IQ. Neuroparenting early in life is also based on

(PsychInfo, Philpapers, and Jstor) yielded only one the hope that psychological problems or even crimi-

result or none at all. In addition, we evoked snowball- nal behavior later in life can be prevented enabling

ing methods and searched the references of selected children to grow into productive citizens [2]. For ado-

article for further hints. Articles were scanned on title lescents we found the focus was on both ways to con-

and abstract, and if in doubt, content. trol unruly, criminal, or violent behavior [10, 11] and

Given that our main point of interest is the debate also on enabling adolescents to reach their full poten-

on neuroparenting, we excluded primary sources: tial, cognitively, socially and creatively [4].

empirical neuroscientific findings; parenting books Neuroparenting was found to be disseminated

and their reviews. We also excluded literature on neu- through various routes, most notably public policies,

roeducation and neuroenhancement because these media, and the promotion of direct-to-consumer-

typically address professional educators, not parents products like toys or parenting books. With regard to

and because they focus on cognitive development the dissemination of neuroparenting directly to con-

rather than child development more broadly. Also sumers, the studies focus on parenting books [4, 12],

non-English articles were excluded (Fig. 1). flash cards [13], or educational toys for children [14].

We identified 37 articles that critically discuss the Methodologically, most critical sociological and

phenomenon of neuroparenting. A qualitative analy- ethical studies focused on the content-analysis of

sis of the articles was conducted using Nvivo10, a policy documents, media articles, or parenting mate-

software package designed to analyse qualitative rials [6, 15, 16]. Some studies used a more sociologi-

data, but that is also used for literature reviews. We cal analysis, exploring parenting norms [12, 14, 17].

uploaded pdfs of the articles and linked a label with a Others used a qualitative empirical design that give

description (node) to the arguments we encountered. insight into the experiences of parents [4, 13, 18–21],

We then grouped and synthesized the different nodes. adolescents [9], or policy makers [15, 22]. Two stud-

That way it became apparent how certain ethical ies had as primary target to review neuroscientific lit-

themes and categories reemerge across different prac- erature on which the neuroparenting advice are based

tices of neuroparenting (Table 1). [23, 24].

13Neuroparenting: the Myths and the Benefits. An Ethical Systematic Review

Identification of studies via databases and registers

Duplicate records removed before screening:

Records identified using keyword

1. n = 6 (5 referred to separate book chapters of

‘neuroparenting’ from:

Macvarish Monography. We only included the

1. Google scholar (n = 111)

monography)

2. Pubmed (n = 176)

2. n = 32

3. Psycinfo (n = 1)

3. n = 1

4. Philpapers (n = 1)

Identification

4. n = 1

5. Jstor ( n = 0)

5. n = 0

Records identified using keyword

Records identified using keyword ‘brain parenting’ from:

‘brain parenting’ from:

6. Google scholar (n = 228.000 key word too broad)

6. Google scholar (n =

7. Pubmed (n = 1032 key word too broad)

228.000)

8. Psycinfo (n = 108)

7. Pubmed (n = 1032)

9. Philpapers (n = 996 key word too broad)

8. Psycinfo (n = 111)

10. Jstor ( n = 3340 key word too broad)

9. Philpapers (n = 996)

If the first 50 pages revealed no useful hit, the keyword was

10. Jstor ( n = 3340)

considered too broad, and the rest of the pages were not

screened

Record identified through

scanning literature of selected

Record identified through scanning literature of selected articles:

articles:

11. n = 33 11. n = 0

Records screened Records excluded**

1. n = 105 Reason: non English (n = 7)

2. n = 144 Reason: Book review ( n = 5)

8. n = 3 Reason: Parenting books (n = 7)

11. n = 33 Reason: Only minor reference to neuroparenting (n = 114)

Reason: medical literature on neural conditions (n = 109)

Screening

Reports sought for retrieval Reports not retrieved

n = 43 (n = 0)

Reports assessed for eligibility Reports excluded:

n = 43 Reason: neuroeducation (n = 2)

Reason: neuroenhancement (n = 2)

Reason: focused on treatment of neural conditions (n = 2)

Studies included in review

Included

1. n = 15

2. n = 0

8. n = 3

11. n = 19

Total: n = 37

Fig. 1 Search strategy literature review

13A. Snoek, D. Horstkötter

Table 1 Overview of included studies, describing title, country, methodology and which critical arguments are most prominent

Study Country Methodology Arguments

1 Macvarish (2016) Neuroparent- UK Sociological analysis, document Gap science practice, hidden

ing: The expert invasion of analysis normativity, neoliberal

family life

2 Macvarish (2014) The ’first three UK Review of neuroscientific litera- Gap science practice

years’ movement and the infant ture

brain: A review of critiques

3 Bruer (1999) The myth of the first US Review of neuroscientific litera- Gap science practice

three years: A new understand- ture

ing of early brain development

and lifelong learning

4 Maxwell & Racine (2012) Does Canada Review of neuroscientific litera- Gap science practice

the neuroscience research on ture

early stress justify responsive

childcare? examining interwo-

ven epistemological and ethical

challenges

5 Belsky & De Haan (2011) Parent- General Review of neuroscientific litera- Gap science practice

ing and children’s brain develop- ture

ment: The end of the beginning

6 Wall (2004) Is Your Child’s Brain Canada Sociological analysis Neoliberal

Potential Maximized ?: Mother-

ing in an Age of New Brain

Research

7 Wall (2010) Mothers’ experiences Canada Empirical Neoliberal

with intensive parenting and

brain development discourse

8 Jacobs & Hens (2018) Love, Netherlands Empirical Neoliberal

neuro-parenting and autism:

from individual to collective

responsibility towards parents

and children

9 Mackenzie & Roberts (2017) UK Empirical Neoliberal

Adopting Neuroscience: Parent-

ing and Affective Indeterminacy

10 Broer, Pickersgill & Cunningham- Scotland Empirical Gap science practice

Burley, (2020) Neurobiological

limits and the somatic sig-

nificance of love: Caregivers’

engagements with neuroscience

in Scottish parenting pro-

grammes

11 Leysen (2019) Upbringing and Flemisch Belgium Philosophy, sociological analysis Neoliberal

Neuroscience. Embodied Theory

as a Theoretical Bridge Between

Cognitive Neuroscience and the

Experience of Being a Parent

Policies

12 Wastell (2012) Blinded by UK document analysis Gap science practice

neuroscience: Social policy, the

family and the infant brain

13Neuroparenting: the Myths and the Benefits. An Ethical Systematic Review

Table 1 (continued)

Study Country Methodology Arguments

13 Beddoe (2016) Questioning New Zealand document analysis Neoliberal

the uncritical acceptance of

neuroscience in child and family

policy and practice: A review of

challenges to the current doxa

14 Edwards, Gillies, and Horsley UK Empirical/ document analysis Neoliberal, Gap science practice

(2015) ‘Brain science and early

years policy: hopeful ethos or

‘cruel optimism’?’

15 Broer & Pickersgill (2015) Target- UK document analysis Gap science practice

ing brains, producing responsi-

bilities: The use of neuroscience

within British social policy

16 Garrett (2019) Wired: Early UK Critical studies Neoliberal

Intervention and the ‘Neuromo-

lecular Gaze’

17 Shonkoff (2011) Science does not US Document analysis / empirical Gap science practice

speak for itself: Translating child

development research for the

public and its policymakers

18 Wall (2018) ‘Love builds brains’: Canada Document analysis Hidden normativity

Representations of attachment

and children’s brain develop-

ment in parenting education

material

19 Wilson (2002) Brain Science, UK, US, New Sociological analysis Hidden normativity, Gap science

Early Intervention and ‘At Zealand, South practice

Risk’ Families: Implications for Africa

Parents, Professionals and Social

Policy

20 Macvarish (2014) Babies’ brains UK Document analysis Gap science practice

and parenting policy: The insen-

sitive mother

21 Lee, Lowe, and Macvarish (2014) UK Document analysis Gap science practice

The Uses and Abuses of Biol-

ogy: Neuroscience, Parenting

and Family Policy in Britain. A

‘Key Findings’ Report, Univer-

sity of Kent

22 Macvarish (2015) Neurosci- UK Document analysis Gap science practice, neoliberal

ence and family policy: What

becomes of the parent?

23 Macvarish (2015) Biologising par- UK Document analysis Gap science practice, neoliberal

enting: neuroscience discourse,

English social and public health

policy and understandings of

the child

24 Lowe & Macvarish (2015) Grow- UK Document analysis Gap science practice, hidden

ing better brains? Pregnancy and normativity

neuroscience discourses in Eng-

lish social and welfare policies

13A. Snoek, D. Horstkötter

Table 1 (continued)

Study Country Methodology Arguments

25 Leysen (2020). Neuro-stuffed Belgium Document analysis Neoliberal

parenthood? Discursive con-

structions of good parenthood

in relation to neuroDiscourse in

Flemish social policy documents

addressing parents: a case study

Media

26 O’Connor & Joffe (2013) Media UK Media analysis Gap science practice

representations of early human

development: Protecting, feed-

ing and loving the developing

brain

27 O’Connor & Joffe (2015) How UK Partly empirical Gap science practice

the Public Engages With Brain

Optimization: The Media-mind

Relationship

28 Thompson & Nelson (2001). US Media analysis Gap science practice

Developmental science and the

media: early brain development

Directed to consumers

29 Nadesan (2002) Engineering the US Sociological analysis Neoliberal

Entrepreneurial Infant: Brain

Science, Infant Development

Toys, and Governmentality

30 Thornton (2011) Neuroscience, US Sociological analysis Neoliberal

affect, and the entrepreneuriali-

zation of motherhood

31 Chen (2019) Beyond black and Taiwan Empirical Neoliberal

white: heibaika, neuroparenting,

and lay neuroscience

Teenage brain

32 Van de Werff (2017) Being a good Netherlands Partly empirical Gap science practice

external frontal lobe: Parenting

teenage brains

33 Van de Werff (2018) Practic‑ Netherlands Partly empirical Gap science practice

ing the plastic brain. Popular

neuroscience and the good life.

Maastricht University. (strong

overlap with the above article)

34 Elman (2014) Crazy by Design. US Analysis of parenting books Hidden Normativity

Neuroparenting and Crisis in the

Decade of the Brain

35 Elman (2015) Policing at the US Sociological analysis Hidden Normativity

Synapse: Ferguson, Race, and

the Disability Politics of the

Teen Brain. (Strong overlap with

above article)

36 Choudhury, McKinney, & Merten UK Empirical Neoliberal

(2012) Rebelling against the

brain: Public engagement with

the “neurological adolescent.”

13Neuroparenting: the Myths and the Benefits. An Ethical Systematic Review

Table 1 (continued)

Study Country Methodology Arguments

37 Bessant (2008) Hard wired for AU/UK/US Sociological analysis Gap science practice, hidden

risk: Neurological science, “the normativity

adolescent brain” and develop-

mental theory

Content analysis neuroparenting literature. In this review we added a

fourth layer: 4) Our critical examination of the criti-

Looking at the content of the critical literature, three cal literature. In the following section we will mostly

lines of criticism emerge. First, a gap is identified focus on the third layer, the critical literature itself.

between available neuroscientific evidence and result- However, to understand and illustrate the arguments,

ing neuroparenting advice. Second, when translating we will also outline part of the neuroscientific litera-

scientific findings into parenting advice and practice, ture and primary neuroparenting literature.

critics point out that translators’ implicit norms color

this translation. The third line of criticism regards Gap Between the Neuroscientific Evidence and

the way in which the advice is informed by and con- Neuroparenting Advice

tributes to harmful neoliberal ideas of the goal of

parenting. Neuroparenting advice typically presents itself as

When examining the content of the critical litera- directly following from neuroscientific evidence. Dif-

ture we found it useful to distinguish between three ferent scholars in the critical literature have pointed

different layers. 1) The neuroscientific literature on out that the translation of neuroscience to policies and

which the neuroparenting advice is based. 2) The pri- parenting advice is not as straightforward as is often

mary neuroparenting literature, i.e. parenting books, assumed. ‘Evidence for policy making does not sim-

policy documents or media articles. 3) The critical ply repose in journals “ready to be harvested”’ [25].

sociological and ethical literature that evaluates the Science does not speak for itself, Shonkoff and Bales

Fig. 2 Field map on critical sociological and ethical literature on neuroparenting

13A. Snoek, D. Horstkötter

(2011) warn. Translating scientific findings to prac- visual input in one eye from birth to three months old.

tices is a skill and the following four examples show Afterwards, these kittens stayed blind permanently in

what this means. the deprived eye. In contrast, eye-closure in adult cats

had no permanent effect [26]. While this shows that

The Scientific Myth of the ‘First Three Years visual input in the first three months of life is neces-

Movement’ sary for the development of normal vision in cats,

Bruer argues that the implications of this for par-

One of the earliest criticisms of neuroparenting found enting humans during early infancy is unclear [23].

in our study is Bruer’s discussion of the “first three Finally he argues that much of the advice was not

years” movement. Bruer, a former president of a based on revolutionary new brain insights, but rather

foundation that supported research in cognitive devel- on psychological theories such as attachment theory.

opment, child health, and brain development, noticed More generally Bruer questions the notion of vul-

in the mid 90 s an increase in US media reports stat- nerability and critical periods based on neuroscience.

ing that new brain science was about to revolutionize Neuroscientific studies also present evidence that

child care and parenting. Bruer identified three spear human development is a process of life-long learn-

point of these revolutionizing insights: i) there are ing, based on the plasticity of the brain [23]. Based

critical periods – windows of opportunity – for brain on these observations, Bruer concluded, in 1999, that

development that should not be missed; ii) during the first three years movement, so prominent in policy

these critical periods, the brain needs the right stimu- and media, is based on scientific myths. In an update

lation to develop well, if that does not happen, perma- memo from 2011, he argued this still rings true: ‘The

nent damages can occur, iii) the first three years of a evidentiary base for claims about early brain devel-

child’s life is a period of rapid synaptic growth, hence opment does not seem to be expanding, the interpre-

this is an important critical period whereupon inter- tations are not improving, and the same examples,

ventions should focus in order that the right stimula- phrases, and images constantly recur.’ (page 11) [1].

tion occurs. He dubbed advice focused on these three In a similar vein, Macvarish [1] showed that neu-

spearpoints ‘the first three years movement’ [23]. He roscience gets invoked to support two rather opposite

noted that this interpretation of the neuroscience was messages. When parenting advice is given, focus is

also informing early childhood policies. put on the vulnerability of the developing brain and

Despite forceful claims to be based on novel scien- the danger of inflicting irreversible harm. However,

tific findings, Bruer argued that the scientific under- when arguing for the adoption of early interventions,

pinning of apparent critical periods very early in life a focus on the plasticity of the brain and the reversi-

stemmed from 1) either preliminary neuroscientific bility of early damage gets promoted. It is argued that

findings not yet understood in behavioral terms; 2) the neuroscience is being invoked in an instrumental

animal studies without any obvious implications for way, supporting whichever political agenda is pur-

humans or 3) pre-existing psychological theories on sued, rather than setting or shaping the agenda itself.

attachment [23]. First, he points out that the neurosci-

entific research appealed to described brain structures The mere rhetorical force of brain scan images

or mechanisms without detailing how these neural for early intervention policies

changes influence behavior or development. Instead

the links to behavior tended to have the status of a In 2002 neuroscientist Perry, who conducted research

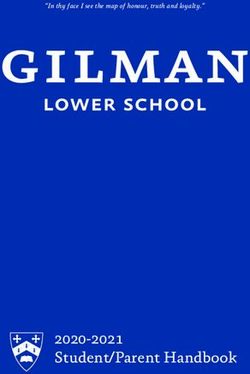

hypothesis. In contrast those, such as policy makers, on neglect, published a harrowing image of a CT-

who were interpreting the neuroscience in order to scan of the brain of a severely neglected child (cf Pic-

develop parenting advice, jumped to unjustified con- ture 1) [27].

clusions. Secondly, he pointed out that research cited This image became prominent in UK policy docu-

to support the claim that there are critical periods of ments advocating early intervention, even illustrating

brain development was done on animals and argued the cover image of these reports [28, 29], However,

that its application to the human case was far from the critical literature questions the representativeness

clear. For example, much cited in this movement is of the image, suggesting it is used not because of its

a study that used kittens that had been deprived of scientific validity but rather because of its rhetorical

13Neuroparenting: the Myths and the Benefits. An Ethical Systematic Review

their children must learn to adapt. In this sense, co-

sleeping, feeding on demand and baby slings charac-

terize responsive parenting, whereas sleep-training,

care scheduling and (forward-facing) prams indicate

unresponsive parenting. Many parenting books pre-

sent neuroscientific evidence to argue that responsive

parenting is the best parenting style to reduce psycho-

logical problems like anxiety in children [32].

A review by neuroscientists Lupien and colleagues

[33] is frequently cited in support. They reviewed

studies on the influence of stress on the brain and

argue that because humans are born relatively help-

less they are very dependent on caregivers, and hence

Picture 1 Perry’s image of a CT scan of a healthy and babies have a stress response system that is highly

extremely neglected 3 year old child (Perry 2002, p.93) attuned to environmental cues [33]. In order to reduce

the activation of infant’s stress system they recom-

force [25, 30, 31]. It is noted that no information mend responsive parenting [33].

regarding the case history of the child in question is Maxwell and Racine [24] question the scientific

provided. Without this information we cannot rule out evidence reviewed by Lupien and colleagues. They

the possibility that the child might have had a mas- point out that these studies typically measure stress

sive birth trauma, or some congenital condition that by elevated cortisol levels. However the link between

caused the neglect and as a consequence the observed higher cortisol levels at certain points in time and

aberrations. The brain scan image made famous by adverse behavioural outcomes is not well established

policy makers is much less instructive than often and much less evidence exists for the alleged irrevers-

claimed [25]. ibility of the effects of high cortisol levels. Moreover,

Perry’s original study [2] notes that in severely the effect of responsive parenting on stress and stress

neglected children only 11 out of 17 brain scans reduction has not been studied at all. Therefore, they

(64.7%) were deviant. In other words more than a argue the claim that neuroscience shows that respon-

third were not. For children with a chaotic upbring- sive parenting is essential for child wellbeing, is

ing, but no severe neglect, only 3 out of the 26 brain unjustifiable [24].

scans (11.5%) were deviant [27]. So, while some chil- Macvarish [1] provides a different line of criti-

dren who experience severe neglect or adverse living cism, showing that ‘responsive parenting’ is a revival

conditions show visible brain aberrations, many do of attachment parenting that became popular during

not. Perry himself publicly objected that his work was the sixties. She notes that, while it was originally pro-

oversimplified and misinterpreted. His findings only moted as one parenting style among equals, by sug-

related to extreme neglect and not broken homes, gesting that it has neuroscientific support, responsive

as some politicians suggested [15]. For example the parenting is presented as being best for brain devel-

neglected child whose brain scan is depicted was opment, implicitly disqualifying parents who parent

locked in a basement for several years [25]. differently.

The Lack of Neuroscience Behind ‘Responsive The Limited Neuroscience Behind Neuroparenting

Parenting’ Advice for Enriched Environments

‘Responsive parenting’ is another focus of the criti- Nadesan’s [14] and Thornton’s [12] critical exami-

cal literature. This is a parenting style in which par- nation focuses on the neuroparenting claim that

ents are continuously attuned to, and promptly react enriched environments are crucial for proper brain

to any cues of children’s distress. Unresponsive par- development and the resulting industry of supposed

enting, by contrast, is characterized by the parent brain stimulating toys. They argue that very little

setting scheduled sleep- and feeding times, to which research has been done on which brain regions these

13A. Snoek, D. Horstkötter

toys stimulate nor on the long term cognitive effects mechanisms, and hypothesizes what this can mean

they afford [12, 14]. for behavior. Policy makers and the general public

For example, in 1998 the governor of Georgia, too quickly equate the mechanisms with behavior. 3)

US, recommended to buy Mozart cd’s for every In this translation from mechanisms to behavior, one

newborn, claiming that neuroscience had shown that can easily come to different, quite opposite conclu-

listening to this music stimulates babies’ cognitive sions. For example, the neuroscientific evidence can

development [13, 16]. However, the only study that both support theories of vulnerability as of plastic-

demonstrated that listening to Mozart’s sonata could ity. 4) Neuroscientific research is often static, or only

improve brain performance was conducted among describes short time effects, yet the conclusions are

a small group of college students and the effect was applied on development and long term outcomes. 5)

measured on a short-term, i.e. ten minutes after lis- Neuroscience is sometimes used to give existing theo-

tening to the music [34]. No studies had been done ries more weight, instead of generating new insights.

on babies, none had involved repeated brain meas- In this way, neuroscience seemed to be used more in

urement and no long-term positive effects of music rhetorical rather than scientific ways.

on brain development had ever been measured. This Some critical scholars think it is too early for

example demonstrates how initial findings get extrap- neuroscience to inform early child policies, that the

olated into claims on long-term brain development current neuroscientific results are too preliminary to

[35]. usefully inform child rearing advice. ‘As it turns out,

A second focus of the critical literature are dubi- the study of parenting and brain development is not

ous neuroparenting toys such as Disney’s series of even yet in its infancy; it would be more appropriate

‘Baby Einstein’ animations. These animated DVDs to conclude that it is still in the embryonic stage, if

for babies from one month old expose them to shapes, not that which precedes conception.’ (page 410) [35].

colors, animals, music, art and even science. Disney Bruer states: ‘We do not have a revolutionary, brain-

claimed that neuroscience has shown that this sup- based action agenda for child development’, express-

ports cognitive development [12] saying in their ing the fear that the wrongful application of neu-

1997 press release: ‘According to cognitive research, roscience will give it a bad name, preventing future

dedicated neurons in the brain’s auditory cortex are research to inform policies [23]. Many scholars argue

formed by repeated exposure to phonemes, the unique that what is currently presented as neuroscience in

sounds of language. Studies show that if these neu- media and policy documents is often a caricature of

rons are not used, they may die’. (cited in: [36]). How- neuroscience: neuromyths, neurogossip, neurobabble,

ever, research found that infants aged 8–16 months brain porn, neuroscience fiction, a mythological ver-

who watched the video’s scored lower on language sion of the infant brain [13, 15, 25, 30]. In our discus-

development than their peers who didn’t watch ani- sion, we will present some suggestion on how the gap

mations [37]. While this negative link was contested, can be bridged.

a positive link between language development and the

mentioned animations could never be established [38] Hidden Normativity in the Translation From

and Disney had to refund parents for providing mis- Neuroscience to Practices

leading information [12].

The apparent gap between allegedly neuro-informed

policies and neuroparenting advice and actual scien-

Conclusion tific findings, leads to a second line of argument in

critical studies on neuroparenting. In the translational

In examining the criticisms focused on the translation process from science to policy and parenting advice it

of the science, we identified five distinct pitfalls: 1) is argued that preexisting normative judgments seep

Neuroscience is done within a specific, sometimes in [4, 16]. Van de Werff [4] calls this phenomenon

exceptional context, but gets uncritically translated to ‘value work’. How we attribute meaning to scientific

other groups and situations. For example, research on findings is not an objective process, but also steered

severe neglect gets translated into regular parenting by values. While this is partly inevitable because sci-

situations. 2) Neuroscientific research often describes ence is always a social practice impacted by cultural

13Neuroparenting: the Myths and the Benefits. An Ethical Systematic Review

values, this does not justify biased or even discrimi- are impoverishing or even neglecting their children

natory interpretation of findings [39]. However, vari- [15]. Rather than fostering equal chances and break-

ous authors point out that the neuroscientific data ing social determinism, by invoking pre-existing

is interpreted in terms of pre-existing ideas of good prejudices under the disguise of neuroscience, social

parenting [1, 4, 10, 40]. We present here a series of differences are intensified, leading to further stigma

examples of the interpretation of neuroscience to and possible additional adverse effects for parents and

enforce existing power hierarchies with regard to children with a comparatively low social economic

class, ethnicity and gender in parenting. It is argued status [15]. ‘Working-class parents, who lack the cul-

that these normative judgments tend to go unregis- tural capital of their middle-class counterparts, are

tered because people view neuroscientific evidence as implicitly targeted as lacking the skills to adequately

objective and unbiased. stimulate and prepare their infants.’ (page 423) [14].

Class and Socio‑Economic Status Ethnicity and Cultural Variation in Child Rearing

At first glance, neuroparenting early intervention ini- Elman [10] makes a similar argument with regard to

tiatives hold a positive message. If all children get the ethnicity. She studied ethnicity bias in the presenta-

right brain stimulation and nurturing from birth, they tion of neuroscientific results on the so-called ‘teen-

will no longer be held back by their social class. Neu- age brain’ and the claim that generally adolescents

roscience can help to give everyone an equal chance, exhibit more impulsive and more antisocial behavior

regardless of their social-economic background [41]. than both children and adults. Current neuroscientific

Before, we showed how research on severe neglect studies try to offer explanations for this erratic behav-

lead to pleads for early intervention policies that ior, such as imbalances in the development of dif-

focus on enriched environments and responsive par- ferent brain regions and delayed development of the

ents. However, it remains unclear what this research prefrontal cortex responsible for self-regulation and

on severe neglect means for typical households, inhibition [4, 9–11].

where there is no neglect, let alone severe neglect. So While the neuroscientific findings actually hold

far no scientific research has been done about what for all adolescents as an age-group, Elman outlines

the threshold is for an environment that is too poor to how the same data leads to different judgements

safeguard proper brain development, and what counts depending on one’s ethnic group. When Caucasian

as an enriched environment [1, 23]. adolescents exhibit annoying, or antisocial behavior,

Despite this lack of knowledge, popular media, the tendency is to whitewash it as being age-typical

policy reports, and parental educational material because adolescents’ brains are out of balance. How-

seems to equalize an enriched environment with a ever, when it comes to similar behavior in adolescents

white, middle-class environment [14–16, 42]. ‘Com- of color, neuroscience is not invoked to excuse it as

plex, enriched environments for humans end up hav- age-congruent, but rather to argue that these young-

ing many of the features of upper-middle class, urban, sters’ brains were wired for violence from a very

and suburban life’ ([43], page 10). For example lis- early age. Youth of color get excluded from childhood

tening to classical music, watching educational televi- innocence, and therefore are more often institutional-

sion like Sesame street, or playing with certain edu- ized [10].

cational toys like Lego building blocks are presented Another example is cultural variation in child rear-

as constituting an enriched environment. In contrast, ing. The research on severe neglect shows the impor-

watching Sponge Bob or listening to rap music are tance of bonding, however, this concept also gets

hardly ever presented as being part of an enriched translated into a white, Western conception of ideal

environment [14]. Supposed neuroscience findings family life, wherein a nurturing, constantly avail-

are being used to reinforce existing values and cul- able mother is essential [15]. This bonding, however,

tural norms, in the absence of scientific evidence on could likewise occur between a baby and another sta-

what counts as enrichment. Equating enrichment with ble caregiver like a father, elder siblings, or grandpar-

white middle-class features suggests that people who ents. Building family policies on an Eurocentric ideal

do not value typical middle or upper-class activities of family life and suggesting that this is backed-up by

13A. Snoek, D. Horstkötter

objective neuroscience, risks pathologizing and sanc- is only one scene in the entire series where a father

tioning culturally different but equally appropriate is comforting a crying baby. O’Connor and Joffe [16]

practices of child-rearing [15, 42]. analyzed 505 media articles on early development in

the UK, which focused on brain development. They

Gender conclude: ‘Mothers were generally positioned as the

target of parenting directives, with articles often using

The critical literature also points out that implicit the word ‘mothers’ where the gender-neutral ‘parents’

normative ideas about gender color the interpretation would have also been appropriate’ (page 304). Critics

of neuroscientific results. Macvarish [1] argues that point out that neurodevelopmental research is often

neuromothering rather than neuroparenting better used to reinforce traditional gender roles.

describes much of the advice. Two characteristics of

neuroparenting contain pitfalls for reinforcing tradi-

tional gender roles: the focus on very early interven- Summary

tion (often prenatal) and the focus on the importance

of love. In this strand of the critical literature we can see how

The strong focus on early intervention as prenatal the translation of neuroscientific findings to practices

puts much pressure on mothers. A Unicef brochure and parenting advice is not a clear-cut top down infu-

‘Building a happy baby’, argues that parents can sion of science, but happens in interaction with pre-

stimulate neural development by stroking their bump, existing values and norms. Although the reference to

playing music to the fetus, or reading a story to him neuroscientific literature suggests that an objective

or her [3]. While this could technically also be done basis had been established to distinguish between

by the father, it is suggested that this focus on inter- good and bad, normal and abnormal parenting [44],

ventions starting in uterus are more likely to be felt as the advices mostly echo existing ideas about class,

a responsibility for mothers, and most of the images ethnicity, and gender. Biologising these differences in

in the brochure contain women [1]. class, ethnicity and gender risks that already vulner-

Jacobs and Hens [19] remark that the new, neuro- able groups might be further stigmatized instead of

scientifically imbued discourse on the importance of helped, increasing existing inequalities.

parental love, can largely be equated with the nine-

teenth century discourse on maternal love. In this dis- Neuroparenting as a Form of Neoliberal

course maternal love and nurture were presented as a Self‑Management

kind of ‘natural’ state of motherhood. Thornton [12]

argues that neuroparenting books encourage mothers The final form of criticism of neuroparenting we iden-

to manage their emotions in order to ensure the emo- tified is that it is part of a neoliberal tradition in which

tional well-being of their children. Mothers should individuals are increasingly held responsible for their

internalize a loving, nurturing attitude, for example, own success and that of their children. As ‘neolib-

smile and look at their baby when feeding. The mes- eral’ can mean various things, we cite some defini-

sages this discourse sends is an obligation to enjoy tions from the critical literature on neoliberalism: a

mothering, to not just act happily but sincerely be and tradition in which ‘individual self-management, self-

feel happy when nurturing your child. In these par- enhancement, and personal responsibility’ are key

enting books, fathers and their need to manage their points [45]; ‘body/ self-maintenance have become the

emotions do not even get mentioned [12]. new duties of the neoliberal citizen where, by looking

It is also argued that this focus on mothers rather after oneself one avoids being a financial liability to

than parents is present in many educational materi- the state’ [44]; ‘entrepreneurial models of self-con-

als on neuroparenting, and media representations of duct’ [12]. These definitions point towards a culture

early development. Wall [42] analyzed a series of vid- of capitalistic self-improvement.

eos of a Canadian parental education campaign called Neuroparenting is analysed as a form of gov-

‘Healthy Baby Healthy Brain’. She noticed that of the ernmentality, in which people internalize certain

scenes depicting a parent interacting with their baby, norms to become productive citizens [1, 6, 12, 14,

43 were of mothers and only seven of fathers. There 45]. It is suggested that the neoliberal norms behind

13Neuroparenting: the Myths and the Benefits. An Ethical Systematic Review

neuroparenting advice includes claims that children’s duty of neoliberal citizens to avoid becoming a finan-

brain are highly malleable, that it is parents’ responsi- cial burden to the state [15, 44, 46].

bility to properly form their children’s brains, and that

parents are blameworthy when things go wrong [1]. An Unjustifiable Amount of Responsibility Attributed

This has been criticized on three accounts. to Parents

Tension Between Individual Interests of Child Neuroparenting advice is also criticized for its ideas

Wellbeing and Societal Economic Interests on malleability; that life can be orchestrated and that

children can become whatever they want to if only

Neuroparenting holds a promise of bettering chil- their brains are stimulated early and intensively [47].

dren’s lives by providing them better cognitive and The UNICEF brochure entitled ‘Building a happy

social emotional development. However, several baby’ [3] (emphasis by the authors) expresses this

scholars have pointed towards an apparent difference idea rather clearly, suggesting that raising a child is

between what parents think ‘better lives for children’ comparable to building a house. This triggers the

means, and what governments have in mind [14, 19]. concern that whenever children do not perform as

While parents aim to see their children becoming intended, parents can be held personally responsible.

smart, social and happy, for governments ensuring O’Connor and Joffe [20] found in their analysis

social-emotional and cognitive development of chil- of media articles on early development that various

dren rather seems to be a means to raise more produc- phenomena, like psychiatric disorders, obesity, alco-

tive citizens, and reduce antisocial behaviour [6, 12, holism, and even sexual orientation are presented as

14, 19]. The main goal of early interventions hence direct consequences of ‘prenatal events impacting

might not be family wellbeing, but prevention of chil- on the fetal brain’ (p.5) [16]. The Sun, for example

dren becoming a burden to society [14, 44, 45]. released the following header: ‘Pregnant women

For example UK early intervention policies often can impair their unborn tot’s IQ by eating liquorice,

refer to the economist Heckman who explicitly linked researchers have warned.’ (7 October 2009). The crit-

child development to societal costs [44]. By training ical literature outlines that warnings like these can put

parents to take care of their children’s brains, better strong pressure on (prospective) parents, particularly

citizens can be formed. The titles of relevant policy mothers, to ensure that they do not disrupt fetal brain

reports reflect this attitude. For example: ‘Good Par- development [16]. As a consequence, there is an ever-

ents, Great Kids, Better Citizens’ [2], or ‘Early Inter- stronger focus on the choices of individual parents

vention: Smart Investment’ [28]. Early brain interven- and less acknowledgment of the wider social factors

tion will save the taxpayer money [22]. that also influence development.

It is argued that through a process of medicaliza- The critical literature points out that, based on the

tion, expert invasion, surveillance, and a shift from neuroparenting trend, government programs indeed

societal to personal responsibility, governmental increasingly invest in individual parent-training,

norms of productivity get internalized by parents. while disinvesting in social support networks, like

Neuroparenting advice tends to medicalize normal good and affordable preschools or daycare [1, 45].

development, such as bonding with one’s baby, or the This is especially hard on parents who are living in

changes during adolescence: ‘Neuroparenting formed relative poverty. The hopeful ethos neuroscience

one of rehabilitative citizenships’ lifelong treatment seemed to entail – that all children, with the right

regimes for chronic youth’. ([10] p. 135) This rheto- brain stimulation could overcome social adversities

ric of medicalization justifies formal surveillance – runs the risk to turn into a cruel understanding of

and intervention in young people’s lives [14]. Sev- success according to which people who do not suc-

eral authors in the critical literature conclude that the ceed should take the blame for their failure [15].

main purpose of neuroparenting would be to train For comparatively well-settled middle-class par-

parents in entrepreneurial self-governance to deliver ents a focus on malleability in the context of a com-

better citizens [12, 14, 15, 44]. Taking care of one’s petitive society can also have detrimental effects.

own and one’s children’s brains becomes the new The critical literature outlines that neuroparenting is

particularly popular among high- and middle-class

13A. Snoek, D. Horstkötter parents. They have the resources to buy the ‘right’ Influence on Intimate Relationships Between Parents toys, books, and other brain stimulating tools [1, 13]. and Children However, these run the danger of changing responsive parenting within a normal range, into behavior that The neoliberal view implicit in neuroparenting advice better would be called hyper-parenting, intensive par‑ has also been criticized as changing the role of par- enting or even paranoid parenting [48]. These types ents and influencing the intimate relationship between of parenting are very time-consuming, and parents parents and children. This supposedly happens in sev- and children can experience this as stressful, while it eral ways: 1) The process of bonding and other inti- is unclear whether this extra stimulation is beneficial mate rituals between parents and children gets instru- [13, 48]. mentalized; 2) Parents are stimulated to adopt the role For example Wall [18] described how Canadian of managers and view their children as the passive mothers are training their kindergarten-aged chil- recipients of parents’ training program and; 3) The dren in primary school subjects. They do so not only relationship between parents and children is mediated to ensure that their children have a better start once by expert advice, while parental intuitive knowledge they go to school, but also because of the continuous is portrayed as insufficient. media attention on how to boost one’s child’s brain The critical literature outlines that for most par- development and an increasing pressure among ents bonding with and stimulating their child comes middle-class parents to engage in these efforts. As a naturally. Parents cuddle their newborn baby because consequence, parents are constantly afraid that their it feels nice, they play games with their children and offspring might trail behind, believing other parents make them laugh because that is fun and because they train their children more. Parents themselves, how- love them, not because neuroscience has appointed ever, describe this kind of hyper-parenting as stress- these behaviors as conducive for brain development. ful, demanding, and occurring at the cost of their own Parents perform these gestures not because they want wellbeing [18]. In the end, it might undermine rather to shape their children’s brains, but because they find than increase well-being. the gestures intrinsically rewarding. Putting these Chen [13] described the popularity of flash- regular daily activities into the context of the need cards on a private maternity ward in Taiwan. These of bonding for the sake of healthy brain development heibaika cards contain black and white silhouettes runs the risk of instrumentalizing the loving relation- of animals and everyday objects and they claim to ship parents build with their young children. Current stimulate brainpower of infants below three months. intimate rituals of family life might be replaced by Chen interviewed parents of newborns who stayed at the new instrumentalized rituals of neuroparenting, the ward. One parent reported keeping her newborn which might aversively affect parent–child relation- awake for up to one hour to train her with the cards. ships [1]. However, there is no scientific evidence that these Thornton describes how neuroparenting books are cards stimulate newborn’s brain development, nor ‘dedicated to codifying and specifying the minutiae that this has any long-term positive effect. Instead, of practices, expressions, and feelings that constitute the popularity of these cards can be linked to an effective maternal love’ (page 412) [12]. Parenting ‘ever-increasing anxiety among Taiwanese parents is presented as a technical process that can be opti- about competition and excellence in the globalising mized, and where a wrong choice can have disastrous world’ (p.4) [13]. Instead of empowering people, this effects. Instructions on how to make eye contact with anxiety makes parents vulnerable and invest money one’s child is a suitable example. When parents make and energy in initiatives that might have no positive too little eye contact with their children, this can impair but potentially negative effects, such as the described language development, bonding and harm children’s sleep deprivation in newborns. Neuroparenting social, and emotional health. However, when parents advice that was meant to help deprived children have make too much eye contact, they risk overstimulating a better start in life is taken up by high- and middle- their child [49]. These instructions put great pressure on class parents as a form of overdrive parenting that parents, who must constantly ‘calibrate the appropriate is rather geared at exceeding the norm than at safe- quantity and timing of eye contact, precisely navigating guarding normal development [12, 14, 18, 48]. the twin dangers of too little and too much’ (page 412) 13

Neuroparenting: the Myths and the Benefits. An Ethical Systematic Review

[12]. While eye contact might be optimised from a neu- literature, we noticed a series of shortcomings. In

roscience point of view, parent–child relationships are order to further the debate on the worth and the lim-

likely to suffer. its of neuroscience informed parenting, it is important

Jacobs and Hens [19] warn that in the current dis- to also identify these shortcomings and show where,

course parental love is presented as a duty, as a neces- when, and why neuroscience findings on parent-

sity in the child’s development, such as clothing and ing are not necessarily doomed to lead to a series of

feeding. This, however, might not only lead to an problems but could also result in benefits and support

instrumentalisation of love, but, philosophically speak- child and family well-being. Our impression is that

ing, also leads to an absurd situation, because ‘love’ as the critical literature solely focuses on potential pit-

such cannot be requested as one cannot will oneself to falls and drawbacks but fails to acknowledge the con-

love [19]. This duty to love can paradoxically disrupt structive potential and possible benefits entailed.

normal bonding by stimulating a mechanic and instru- We will discuss four shortcomings of the criti-

mentalized form of parental love, and result in children cal literature itself and provide suggestions on how

lacking in affect [1, 42]. to balance potential harms and pitfalls with possible

Two metaphors seem to depict this new, instrumen- benefits and advantages of neuroscience-informed

talised role of parents rather clearly. Leysen [17] speaks approaches to parenting practices. Given the great

of parents becoming ‘parenters’: ‘a figure performing diversity of neuro-practices, we first question whether

learned parenting tasks, directed to act in a specific way the general term of ‘neuroparenting’ is even useful.

towards the specific goal of optimal brain development’ We then discuss the proper boundaries of neuropar-

(p.252). Nadesan [14] describes how parents are made enting practices. Third, we argue for the importance

into ‘managers’ and their children become ‘entrepre- of a strong evidence base of the neuroparenting

neurial subjects’. Parents risk to become more focused advice. Finally, we look at the needs and experiences

on their children’s brains than on their children as per- of parents and adolescents themselves investigating

sons and children risk being seen as engineering fail- the alleged harm of such practices.

ures rather than valuable in themselves [14].

In this view of parenting, children are presented as The Generalizability of Results: the Diversity of

merely passive recipients of parenting, with no pref- Neuroparenting

erences, capacities or talents of their own [18]. The

parental duty to shape children’s brains might result in Macvarish [1] was one of the first to coin the term

ever more top-down relationships between parents and ‘neuroparenting’ as an overarching concept that

children. Instead of fostering familial interaction where describes how childrearing practices are increasingly

parents and children learn from each other [4]. informed by neuroscientific findings. In this review,

At the same time, parents themselves are consid- we followed this terminology. The advantage is that

ered in constant need of expert knowledge. In order to it becomes apparent how a variety of local practices

become able to shape children’s brains properly, parents are part of a larger, social movement with potentially

need to comply to expert advice and educate them- shared risks and drawbacks. However, the concept

selves with the latest neurobiological insights. Macvar- itself entails the pitfall that the diversity of practices

ish called this the expert invasion of family life [1, 31]. get generalized under the same umbrella. As a conse-

Existing parental knowledge and intuition becomes dis- quence, the diversity of implications of various prac-

carded [17] and parents become mere amateurs whose tices tends to get overlooked. The critical literature

knowledge about child development and whose cogni- then risks throwing the baby out with the bathwater,

tive capacities are insufficient to adequately take care of overlooking the potential, benefits and advantages of

their children. some neuroscientific findings. The potentially posi-

tive impact on parents, educators and the wider social

environment is also ignored.

Critique of the Critical Literature For example, neuroparenting practices vary widely

in different countries. In the US, neuroparenting lit-

The critical studies of neuroparenting perform impor- erature on adolescence emphasises the explanation of

tant pioneering work. However, when reviewing this the deviant functioning of adolescent brains and aims

13A. Snoek, D. Horstkötter

to provide a recipe against violent behaviours, like contact or breastfeeding as being ‘mere neuroparent-

school shootings. [10]. In the Netherlands, by con- ing’, depends itself on a reductionist understanding of

trast, Van de Werff [4] showed that the neuroscientist the worth of these practices.

Crone’s prominent parenting books on adolescence Another example comes from Wall’s qualitative

contain an explicitly positive perspective on adoles- study on parents’ experiences with intensive parent-

cent brains, as a unique phase of creativity, positive ing and the ‘brain development discourse’ [18]. In

risk taking and social connectivity. This unique phase her conclusions, Wall argued that the brain develop‑

is presented as offering adolescents benefits on the ment discourse led to an escalation of parenting into

job market [4, 50]. These differences in the evaluation hyper-parenting. However, in the quotes of respond-

of the value and challenges of adolescent brains for ents, there is hardly any explicit reference to the brain

young people’s behavior are striking. They also cast development discourse or to neuroscience. Respond-

doubt on the concept of ‘neuroparenting’ as singular ents mainly talked about intensive parenting and

and uniform. Instead, it seems more appropriate to their wish that their children will do well in school,

specify the practice a critical debate has in mind. but they did not link this to neuroscientific findings

Similarly, it is striking that most critical reports on or the brain discourse. Wall seems to equate intensive

early interventions target UK policy documents [6, parenting with neuroparenting, thereby overlooking

15, 25, 30], while in other countries, corresponding the possibility that intensive parenting stems from a

debates hardly seem to exist. Have other countries broader tradition of maximizing a child’s chances in a

found more sound and agreeable ways to use neu- competitive world.

roscience to inform their early childhood policies? Practices should always be interpreted within

Leysen found many differences between Flemish and their context, paying attention to cultural, familial,

Anglo Saxon neuroscientific parental educational and social meanings. In the same way as scientific

material. The Flemish tend to focus less on the first approaches should not limit their understanding of

three years movement, present less evidence from children’s development to brain development, ethical

severe neglect, and had less deterministic views [47]. critiques of such approaches should not limit them-

Again it is not clear that criticism based on the prac- selves to this focus.

tices in one country generalize to practices in other

countries.

The Importance of the Evidence Base of

Neuroparenting Practices

Defining Neuroparenting

As we outlined earlier, some critical scholars identi-

Some critical authors define certain parenting prac-

fied a gap between neuroscientific evidence and the

tices as neuro-parenting practices, when it seems to

neuroparenting advice based on it (see for example:

us that the impact of the prefix ‘neuro’ is doubtful.

[23, 24, 35]). However, other scholars explicitly state

Obviously, the brain is involved in almost all human

that the scientific validity underlying neuroparenting

processes, and most practices impact the brain. How-

advice is outside the scope of their critique. Elman

ever, labelling all kinds of practices that influence

[10] and Wall [45] respectively, argue as follows:

brain development as neuro-interventions can be

rather confusing and undermine the quality of the It is not the task of this chapter to evaluate the

critical debate. scientific validity of this body of knowledge, but

Macvarish [1] or example, terms the advice on the rather to analyse its cultural work. This chap-

importance of breastfeeding and skin-to-skin con- ter offers an analysis of the cultural stakes and

tact between mothers and newborn babies as forms knowledge-power of brain-based thinking about

of neuroparenting. Indeed, these practices are often adolescence as it pervaded popular culture of

offered together with neuroscientific evidence that the 1990s and beyond. (page 133) [10]

they improve bonding and brain development [1]. My aim here is not to establish the truth or

But these practices could also be interpreted as part falsity of the scientific claims being made,

of a countermovement against the medicalization of but rather to suggest that, like other scien-

childbirth. In that sense, dismissing advice on skin tific claims, they are not beyond question and

13You can also read