Mapping the health system response to childhood obesity in the WHO European Region An overview and country perspectives - c - WHO/Europe

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Mapping the health system

response to childhood obesity

in the WHO European Region

An overview and country

perspectives

cMapping the health system

response to childhood obesity

in the WHO European Region

An overview and country

perspectivesAbstract

Childhood obesity is a major public health problem globally, which could undermine progress towards achieving the

Sustainable Development Goals. Prevention is recognized as the most efficient means of curbing the epidemic; how-

ever, given the scale of the problem and the many children who need professional support due to the severity of the

disease and/or obesity-related complications, health systems all over Europe must take steps to develop obesity man-

agement systems. The aim of this project was to assess the response of health care delivery systems in 19 countries

in the WHO European Region to the childhood obesity epidemic. Although there is no doubt about its importance, pre-

vention was not the focus of the work. We used mixed methods. Primary data were collected by administering a ques-

tionnaire to relevant stakeholders and experts through the WHO Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative network; this

was complemented by a literature review and semi-structured interviews in selected countries. Overall, we found that a

health system response to childhood obesity is lacking. Several shortcomings were identified in the areas of governance,

integrated delivery of services, financing and education of the health workforce. The most commonly mentioned barriers

were fragmentation of care (no clear pathways), a shortage of adequate personnel (e.g. childhood obesity specialists,

nutritionists, psychologists), inadequate funding for childhood obesity management or health care in general, insufficient

collaboration among sectors and settings and the lack of parental support and education. Nevertheless, we also report

several practices and examples that may inspire other countries.

Keywords

Childhood obesity

Management

Health systems

Health Care

Financing

Education

Patient pathway

Address requests about publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to:

Publications

WHO Regional Office for Europe

UN City, Marmorvej 51

DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark

Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for permission to quote or

translate, on the Regional Office website (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest).

© World Health Organization 2019

All rights reserved. The Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission

to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any

opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city

or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent

approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or rec-

ommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors

and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in

this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or

implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World

Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. The views expressed by authors, editors, or expert

groups do not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the World Health Organization.Contents

Acknowledgements iv

Foreword from the WHO Regional Office for Europe v

Foreword from the European Association for the Study of Obesity vi

Abbreviations and acronyms vii

Glossary vii

Executive summary viii

1. Introduction and context x

1.1 The epidemic of childhood obesity 1

1.2 Targets for professional support 2

1.3 An issue of inequality 2

1.4 Brief background to childhood obesity management 3

1.5 Towards integrated care in multiple settings 5

2. Objectives and methods 6

3. Results 10

3.1 The childhood obesity management system 11

3.2 Perceived functioning of the system and the main challenges 52

4. Conclusions 56

5. Considerations for Member States 58

References 60

Annex 1. Country questionnaire 66

Annex 2. National guidelines 77

Annex 3. Country reports 79

1. England 79

2. Italy 80

3. Hungary 81

4. Sweden 83

References 85

iiiAcknowledgements

Viktoria Anna Kovacs and Csilla Kaposvari made primary contributions to this report, with additional contributions from

Jo Jewell under the supervision of João Breda. Juan Eduardo Tello (WHO European Centre for Primary Health Care)

and Nathalie Farpour-Lambert (European Association for the Study of Obesity) critically revised and completed the doc-

ument. Tommy Visscher and Charmaine Gauci also helped conceive the publication, critically reviewed and contributed

to finalizing the publication.

The research team would like to thank all participants in interviews and data collection for their time and insight. We

are particularly grateful to Arayik Papoyan (Armenia); Daniel Weghuber, Katharina Maruszczak, Karin Schindler (Austria);

Tatjana Hejgaard (Denmark); James Nobles, Stuart W. Flint, Joanna Saunders, Paul Gately (England); Eha Nurk, Katre

Väärsi, Kädi Lepp, Lagle Suurorg, Ruth Kalda, Aleksandr Peet, Liis Nelis, Sille Pihlak (Estonia); Antje Hebestreit, Barbara

Thumann, Hans Böhmann (Germany); Angela Spinelli, Margherita Caroli (Italy); Ronit Endevelt, Vered Kaufman Shrike

(Israel); Iveta Pudule (Latvia); Charmaine Gauci, Victoria Farrugia Sant Angelo (Malta); Erica van den Akker, Ine-Marije

Bartels, Jutka Halberstadt, Monique L’Hoir, Kyra Jurriens, Ellen Govers, Carry Renders, Liesbeth van Rossum, Marian

Sijben, Edgar van Mil, Jaap Seidell, Tommy Visscher (Netherlands); Igor Spiroski, Katarina Stavric (North Macedonia); In-

gunn Bergh, Knut-Inge Klepp, Ketil Størdal (Norway); Constanta Huidumac (Romania); Elena Sacchini, Andrea Gualtieri

(San Marino); Sergej Ostojic, Visnja Djordjic, Darinka Korovljev (Serbia); Ľubica Tichá (Slovakia); and Ioannis Ioakeimidis

(Sweden) for coordinating the work and collecting data in their countries. We are also grateful for Gregor Starc who pro-

vided the data about the Slovenian SLOFit system.

Finally, the research team would also like to thank Tamara Berkes-Bobak, Agnes Bobak, Fanni Torok-Kovacs, Panna

Torok-Kovacs and Blanka Kaposvari for their illustrations that feature in this publication.

ivForeword from the WHO Regional

Office for Europe

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious global pub- We have prepared this report against this background,

lic health challenges of the 21st century. It affects almost because we care about supporting children with obesi-

every country in the world. The facts speak for them- ty and we wanted to assess whether current health sys-

selves: in the past 40 years, the global prevalence of over- tems are ready to respond to the challenge. The report

weight and obesity in children has increased tenfold. has identified several shortcomings in the countries stud-

ied, but there are also examples of inspiring practices and

Childhood obesity has been described as a ticking time some well-functioning systems that are worth sharing

bomb, and the projected impact on individuals and so- with experts and decision-makers in other countries.

ciety is immense. It is predicted that the current genera-

tion of children may have a shorter life expectancy than In order to deliver more effective childhood obesity ser-

their parents due to the high prevalence of obesity and vices, it is necessary to build a well-skilled, competent,

its health consequences. Physicians are now diagnosing multidisciplinary health care team. We are also aware that,

type 2 diabetes in children – a disease previously found without good governance, adequate financing and inte-

only in adults. This is shocking. If this issue is not properly grated care, we will not win the battle. We hope that this

tackled in childhood, these children will also be at much report will provide readers with a better understanding of

higher risk of suffering from a range of conditions in adult- the strengths and weaknesses of current childhood obe-

hood, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, sity management systems and, in turn, will contribute to

cancers and musculoskeletal disorders. The associated WHO’s longer-term goal of more efficient, equitable, co-

health and social costs to governments come at a time herent, accessible childhood obesity services as part of

when few countries can afford them. The prevention of a comprehensive response to the epidemic of childhood

childhood obesity remains a priority; in addition, we must obesity.

also actively engage in the challenge of managing and

treating obesity. Bente Mikkelsen

Director, Division of Noncommunicable Diseases and

We estimate that about 800 000 children in the WHO Promoting Health through the Life-course

European Region suffer from severe obesity. It is likely

that these children, and their families, have already been João Breda

through various programmes and treatments to try and Head, WHO European Office for the Prevention and Con-

lose weight. Some children do not achieve the outcome trol of Noncommunicable Diseases

they had hoped for, and this is frustrating, not only for

them and their families, but also for the health care pro- Juan Tello

fessionals who support them. Head, WHO European Centre for Primary Health Care

vForeword from the European

Association for the Study of

Obesity

The prevalence of childhood obesity in the WHO Euro- Health insurance organizations, for example, might have

pean Region has reached alarming proportions and is a to extend coverage to include the costs of multicompo-

cause for concern. The number of children and adoles- nent behavioural treatment, which has been shown to

cents with obesity who need medical support and treat- be effective in reducing both the degree of obesity and

ment is rising. As childhood obesity is commonly not rec- co-morbidit conditions. Until now, such care is general-

ognized as a chronic disease, it is typically not considered ly provided only for children with other chronic diseases,

a reason for seeking medical attention. The responsibility such as type 1 diabetes.

for discussing obesity with a child and his/her family thus

rests on care providers, who tend to “conveniently” avoid Little was known about access to care for children and

the issue or fail to diagnose it. Unlike for other common adolescents with obesity in the WHO European Region.

paediatric diseases, there is no “silver bullet” for the man- This report reviews the health system response to the

agement of obesity; it requires time and intensive effort challenge of childhood obesity in countries in the Region

by health care professionals and parents to understand and demonstrates significant gaps in governance and

the underlying factors and agree on a plan of action. To funding of obesity treatment options. In addition, screen-

date, the development and uptake of treatment strategies ing, referral and integrated management pathways for

has been limited due to lack of recognition of obesity as a obesity are lacking in most countries, particularly at the

medical problem and a shortage of dedicated resources primary care level.

for its treatment.

The effectiveness of health care services in managing

The European Association for the Study of Obesity con- childhood obesity has not been evaluated in most coun-

siders that recognition of childhood obesity as a chron- tries. This report will undoubtedly inform policy-makers,

ic disease will improve treatment for those children who health care professionals and other service providers

need it. Treatment will complement other health policies about current approaches to the management of child-

for preventing obesity at societal and individual levels. It hood obesity. We hope it will drive action in countries to

will strongly encourage both families and physicians to improve access to care and reduce inequalities in care

take childhood obesity more seriously. for children and adolescents with obesity. Childhood is a

unique window of opportunity, when treatment can have

Of course, such an approach will also create a significant a lifetime impact on health and quality of life and prevent

number of “new patients” and may increase the workload long-term disability and reduced work productivity.

of health professionals and the immediate health care

costs. Some transformation will therefore be required in Nathalie Farpour-Lambert

health care delivery systems, including adequate train- President of the European Association for the Study of

ing for professionals and appropriate financial resources. Obesity

viAbbreviations and acronyms

BMI body mass index MGP multidisciplinary group programme

CCG clinical commissioning group PCP primary care paediatrician

COSI Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative SDS standard deviation score

GP general practitioner SHS school health services

HMO health maintenance organization

Glossary

Childhood obesity management comprises organized Multi-disciplinarity is the involvement of several disci-

screening, diagnosis, assessment, treatment and fol- plines, e.g. medical, nutrition, exercise, psychology, in the

low-up. management of obesity.

Diagnosis consist of verification of the presence of over- Overweight, obesity and severe obesity are conditions of

weight or obesity and comorbid conditions. abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that present a

risk to health (3). Various definitions have been proposed

General practitioner (GP), also referred to as a “family phy- to classify the weight status of children. According to the

sician”, is the provider of comprehensive, continual care WHO definition, children aged 5–19 years are overweight

to individuals in the context of their family and community if their body mass index (BMI)-for-age is > 1 standard de-

(adapted from reference 1). viation above the WHO growth reference median, obese

if their BMI-for-age is > 2 standard deviations above the

Health care delivery systems are formal structures for WHO growth reference median and severely obese if their

delivering clinical and public health care services to a BMI-for-age is > 3 standard deviations above the WHO

well-defined population both individually and collectively. growth reference median.

They include access (for whom and to which services), or-

ganization of providers and resources (health care work- Progressive care is use of a stepwise algorithm for child-

ers, settings and facilities). hood obesity management.

Health systems consist of all the resources, organizations Screening comprises systematic invitation and follow-up

and actors that undertake or support health service deliv- of identified individuals and access to treatment.

ery, including for care, resourcing, governing and financ-

ing (adapted from reference 2).

Integrated approach is a method incorporating diet, phys-

ical activity, mental health and environmental change (at

home, at school, in the community) and parenting prac-

tices.

viiExecutive summary

In recent decades, childhood overweight and obesity Overall, the findings indicate that countries are taking

have become much more prevalent throughout the WHO some action to tackle the problem, but there is a delay in

European Region and are of increasing concern for public the health system response and several constraints.

health, as they have negative effects on health, the econ-

omy and society both immediately and later in life. It has Recognition of childhood obesity as a chronic dis-

been predicted that the current generation of children will ease: In most countries, childhood obesity is recognized

have a shorter life expectancy than their parents because as a chronic disease by both the responsible authority

of the high prevalence of obesity and its health conse- and health professionals; however, the interviews indicate

quences (4). Although prevention is critical, the problem that childhood obesity is not always considered and treat-

of overweight and obesity in children is unlikely to be fully ed as a chronic disease in practice, particularly in primary

resolved without the involvement of the health care deliv- care.

ery systems. Furthermore, excess weight continues into

adulthood, often with several associated chronic diseases Professionals and other personnel: Primary care ser-

(5). vices are provided mainly by nurses and physicians in the

participating countries, and there are few multidisciplinary

The aim of this work was to describe the response to the care teams.

problem of health systems in Europe, especially in health

care delivery. The report includes mapping and descrip- Governance: Lack of good governance is reflected in the

tion of the situation in countries and some of the most absence of strategic documents on the management of

promising solutions. We used mixed methods – a litera- childhood obesity and in the rarity of coordinated action.

ture search, a questionnaire survey in 15 countries and Although awareness appears to be increasing among the

semi-structured interviews in four countries – to answer general public, health professionals and governments,

the following questions. decision-makers focus much more on prevention than on

organizing disease management.

• Which professionals are involved in childhood obesity

management, and what is their role therein? Guidelines: Most countries reported that they had guide-

lines on childhood obesity management, but only a few re-

• What are the clinical pathways for the management of ported having a single, nationally accepted, widely used,

childhood obesity, from screening to diagnosis, treat- regularly updated document. As the aim is to improve the

ment and follow-up? quality and consistency of care, the use of multiple guide-

lines in one country will decrease the likelihood that all

• In which settings is childhood obesity managed and patients receive treatment and care in the same manner.

what are the entry points into the health system?

Screening and referral for care: All the participat-

• What are the provisions for long-term care and fol- ing countries reported some kind of national or regional

low-up? mechanism for evaluating the weight of all children regu-

larly. Some of the mechanisms, however, are considered

• What are the funding arrangements for childhood obe- to be monitoring or surveillance, and only a few can confi-

sity management, and what services are covered? dently be categorized as screening programmes for obe-

sity management. The pathways are often unclear and are

• What support is available for childhood obesity man- based on individual decisions (personal or by clinicians) in

agement? most countries. There are, however, some examples of

clear referral criteria and well-described pathways.

• To what extent do the current systems address ine-

qualities in health and the specific needs of groups with Diagnosis and assessment: Overweight or obesity in

low socioeconomic status? children is usually diagnosed in primary care or in spe-

cialized care by physicians or medical specialists. If risk

• How do informants perceive the functioning of the sys- stratification is performed, it is also done by physicians

tem, and what challenges have they identified? when they are screening for underlying causes and for

obesity-related comorbid conditions. The result of risk

• Are there promising initiatives and practices in child- classification is included in planning management in only

hood obesity management? half of the surveyed countries.

viiiPrimary care: Unnecessary referrals and lack of multidis- obesity, and the availability of post-graduate training and

ciplinary teams were reported by some countries. Primary courses on childhood obesity management is limited.

care paediatricians and general practitioners require more

education on childhood obesity. There is insufficient com- Inequalities: Although countries reported various actions

munication between primary and specialized care provid- to reduce inequality and ensure equal access to care, the

ers. characteristics of current childhood obesity management

systems in many participating countries imply the possi-

Specialized care: Multidisciplinary teams are more com- bility of population inequity. Differential access to services

mon in specialized than in primary care. One challenge in was described as both regional (i.e. urban–rural differenc-

specialized care appears to be the heterogeneity of ser- es) and in the health care system (i.e. social and language

vice provision in a country in terms of content and imple- barriers). The current systems are unable to address eco-

mentation (e.g. inpatient versus outpatient care, length of nomic and social inequalities or respond to the special

treatment, availability of multidisciplinary teams). Several needs of families with the highest burden.

countries highlighted the need for better communication

between primary and specialized care providers as well Challenges and barriers: The countries reported many

as among specialists, as care is often fragmented. There similar challenges and barriers in the functioning of their

are not enough specialized centres to care for the grow- childhood obesity management systems, despite their

ing number of children who are obese or severely obese. different contexts. Most of the challenges and barriers

are related to governance, including lack of an integrated

Management of patients with severe obesity: De- strategy for both prevention and care. The organization of

spite its increasing prevalence and the serious immediate care and structural issues in the childhood obesity man-

and long-term physical and psychological consequences, agement system, such as weak vertical and horizontal in-

current treatment options for children with severe obesity tegration of care providers and a lack of clear care path-

are limited, in terms of both effectiveness and availabili- ways and guidelines, were identified as additional barriers.

ty. This is particularly the case for younger children. The An important challenge for current systems is to ensure

services available in the participating countries are char- equal access to services and the capacity to adequately

acterized by short-term inpatient care with no defined af- respond to the social and cultural needs of the population

ter-care services. Structured management pathways are most in need of childhood obesity management.

critically needed.

Education: In most countries, medical students do not

receive systematic curricular education on childhood

ix1. Introduction and context x

1.1 The epidemic of childhood obesity collect measured

data on the height

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious public and weight of children The number of children

health issues of our time. The prevalence of obesity has aged 6–9 years, and with obesity worldwide

increased sharply worldwide, fuelled by a profound nu- prevalence rates are has increased 10 times

tritional transition to processed foods and high-calorie di- calculated according in the past 40 years.

ets and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle characterized to WHO definitions. In

by mechanized transport, urbanization and information the latest round, data

technology (6). Globally, the number of girls with obesity were collected in 41 countries between 2015 and 2016.

increased from 5 million in 1975 to 50 million in 2016 (7), Of the 19 countries that participated in the current study,

and the number of boys with obesity increased from 6 14 contribute to COSI. In these countries, the prevalence

million in 1975 to 74 million in 2016; 73% of the increase of overweight and obesity ranged from 17.6% to 41.9%

in absolute numbers can be explained by an increase in for boys and from 20.1% to 38.5% for girls, and the prev-

the prevalence of obesity, rather than population growth alence of obesity was 4.9–21% among boys and 5.1–

(7). 14.9% among girls1 (Fig. 1).

In Europe, the most accurate comparable data on the COSI data suggest an increasing north–south gradient,

prevalence of childhood obesity are provided by the WHO with the highest prevalence of overweight and obesity

European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) in southern Europe. In the countries that collected data

(8). COSI was established in 2007 in response to lack of for more than one age group, the prevalence of over-

standardized surveillance data. Within COSI, countries weight and obesity tended to increase with age (9). The

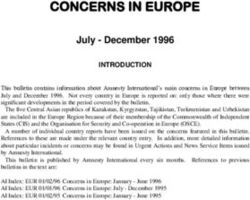

Fig. 1. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the 14 countries that contribute data to COSI, 2015–2016

45

40

35

30

Percentage (%)

25

20

15

10

5

0

8 years 7 years 7 years 7 years 8 years 7 years 7 years 7 years 8 years 8 years 8 years 8 years 8 years 8 years 7 years 7 years 8 years

AUT DEN EST HUN ITA LVA MAT MKD NOR ROM SMR SRB SVK SWE SRB SVK SWE

WHO definition overweight boys WHO definition obese boys

WHO definition overweight girls WHO definition obese girls

AUT, Austria; DEN, Denmark; EST, Estonia; HUN, Hungary; ITA, Italy; LVA, Latvia; MAT, Malta; MKD, North Macedonia; NOR, Norway; ROM, Romania; SMR, San

Marino; SRB, Serbia; SVK, Slovakia; SWE, Sweden

1

Unpublished data 1prevalence of severe obesity varied from 1% to 5.5% growth and achieve and maintain weight loss at the end

among the COSI countries.2 of growth, especially without appropriate professional

support, a substantial number of children who are cur-

Eurostat data (10) show that the number of children aged rently overweight or have obesity will become adults with

0–14 years in countries in the European Union in 2016 obesity. As adults, they will have a greater likelihood and

was approximately 79 million. In the “best case” scenario earlier onset of nearly every chronic condition, including

of COSI data (i.e. a prevalence of 18% overweight and cardiovascular diseases, several types of cancer and type

obesity for boys and 20% for girls and a prevalence of 1% 2 diabetes (17).

for severe obesity), about 7.1 million boys and 7.8 million

girls are living with overweight and obesity in Europe. This Given these immediate and long-term consequences, ap-

exceeds the total population of Belgium (11.5 million in- propriate, early identification of children who need profes-

habitants) (11). The number of children with severe obe- sional support is essential. For several reasons, however,

sity is estimated to be almost 800 000, which is close to decisions about who requires professional support are

the total population of Cyprus (11). not straightforward. In 1979, WHO declared obesity a dis-

ease and provided a code for obesity in the International

A recent projection indicated that the prevalence of adult Classification of Diseases. In 2015, the Childhood Obesity

obesity in Europe will have risen by 2025 (12). As a result, Task Force of the European Association for the Study of

concern has been raised about the future burden of non- Obesity issued a position statement and advocated that

communicable diseases linked to overweight and obesi- childhood obesity be considered a chronic disease that

ty, which will have serious implications for the financial demands specific health care (18). In practice, however,

viability of national health care delivery systems. Preven- there is still discussion about whether childhood obesity is

tion is recognized as the most efficient means for curbing a risk factor, a condition or a disease. As a result, in many

the obesity epidemic in the long-term; however, given the countries, there is still lack of clarity about responsibili-

large number of children with obesity and severe obesity, ty for service delivery (19). Furthermore, some clinicians

health systems should act now. and primary care providers argue that cases of mild over-

weight that are not associated with any comorbid con-

ditions do not necessarily require a medical intervention

1.2 Targets for professional support (20). Genuine concern has been raised about “over-med-

icalization” of obesity in children and the potential risks of

Overweight and obe- stigmatization (21). The lack of a European guideline on

sity in childhood and screening, assessment and treatment of childhood obesi-

Childhood obesity has

adolescence are as- ty further complicates the field. Parents seldom seek pro-

extensive medical, social

sociated with several fessional help for their children with obesity (22), and obe-

and psychological effects.

adverse consequenc- sity is rarely the primary reason for a medical consultation.

Most complications are

es (13). These can be Children with severe obesity are more likely to receive

not diagnosed.

grouped into those proper medical attention and treatment. Severe obesity

manifested in child- is becoming more frequent, and medical complications

hood, long-term medical effects and those that affect of obesity are observed at much higher rates than before

adult weight. First, obesity itself directly causes morbidity (12). These children are disproportionately affected by

in children, including gastrointestinal and musculoskele- the health consequences of obesity and often experience

tal complications, sleep apnoea, asthma and accelerated premature onset of multiple morbid conditions. Therefore,

onset of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, with for severe obesity, all treatment options, including more

their additional comorbid conditions (14). The psycholog- intensive strategies, should

ical consequences at this age typically include bullying, There is sizeable be explored, regardless of

reduced quality of life, loneliness, anxiety and depres- socioeconomic whether comorbid condi-

sion. Moreover, obesity affects academic performance inequality in obesity. tions are present (23).

because of a higher rate of absenteeism and poorer ed-

ucational attainment than would otherwise be expected

(15). Secondly, current evidence links childhood obesity 1.3 An issue of inequality

with an increased lifetime risk for cardiovascular diseas-

es, due to adverse changes in cardiovascular structure There is sizeable socioeconomic inequality in obesity.

and function (16), and the risk remains elevated even if Obesity is more common among poor, less educated

weight is lost. Thus, obesity in childhood or adolescence people (24). Ethnicity is also a correlate of obesity, and

has been associated with twofold or higher risks of hyper- greater metabolic consequences have been observed for

tension, coronary heart disease and stroke in adulthood some ethnic groups, such as significantly increased risks

(17). Thirdly, as it is difficult to slow weight gain during for type 2 diabetes and hypertension (25, 26).

2 2

Unpublished dataA recent review of studies in the USA (27) showed that physicians suggested that individuals with overweight

socioeconomic inequality in obesity has narrowed, but should “reduce food and avoid drinking to fullness” and

the gap has not been closed for all minorities. The same take regular exercise, particularly “running during the

review concluded that severe obesity continues to affect night” and “early-morning walks” (31).

the poor disproportionately. Furthermore, people who are

poor and have severe obesity are still at overall greatest Research on childhood obesity began with medical stud-

risk, as they suffer from the double burden of poverty and ies of the natural history and physiological sequelae of

obesity-related health conditions (14). obesity. These were followed by individual, family and

school interventions, and, more recently, environmental

Comprehensive, upstream policies are ultimately required correlates of and policy approaches to the prevention of

to reduce inequality and prevent obesity, as research sug- childhood obesity, as well as complex community pro-

gests that calling exclusively on personal responsibility grammes (32). Although much has been learnt about the

is likely to be less effective, increase stigmatization and nature of childhood obesity, the problem remains difficult

widen inequality (28, 29). Nevertheless, the needs of chil- to treat. In recognition of the need for a greater, more sus-

dren with overweight and obesity should be addressed tained impact, recent work has focused on obesity pre-

in health care settings, with adequate, appropriate man- vention, in particular on modification of the built and social

agement. Poor and less well educated people and eth- environments, food systems and education that influence

nic minorities often have limited time, fewer coping skills, diet and physical activity. This has led to debate and pol-

less health literacy and financial constraints that limit them icy action, such as school food procurement standards,

from taking advantage of certain public health interven- food marketing restrictions, product reformulation and

tions or management programmes (30). These aspects taxation of soft drinks (33, 34). As long as the prevalence

should be considered in designing strategies and care of obesity remains high, however, individuals with obesity

plans to achieve and maintain significant improvements in will have to be treated to improve their health and well-be-

weight and, consequently, their health. ing and to reduce health care costs and the negative con-

sequences on economies and societies. Currently, there

are three major types of treatment for obesity: lifestyle

1.4 Brief background to childhood obesity intervention, pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery. Un-

management fortunately, no “silver bullet” solution has been found for

obesity management in children and adolescents. Suc-

Obesity has changed from being rare to a disease that is cess is limited with the available conservative therapies

increasingly common all around the world. Surprisingly, in for children (35), even in younger children, who have sub-

broad terms, dietary and lifestyle recommendations have stantially better outcomes (36, 37).

not changed that much since Hippocrates’ time, when

34

Multi-component behavioural programmes (diet, physical costs than nonsurgical interventions. The restrictive (gas-

activity, psychology) are generally considered to be the tric band or sleeve) or malabsorptive (gastric bypass) na-

gold standard treatment for childhood obesity (38). Fam- ture of some forms of bariatric surgery requires additional

ily behavioural therapy was initially developed to modify consideration with regard to growth. Psychological matu-

the shared family environment, provide role models and rity, ability to provide informed consent and the availability

support child behaviour changes. A recent analysis of six of family support and continuing post-operative lifestyle

high-quality Cochrane reviews evaluated the effectiveness support should be considered (43).

of behaviour-change interventions in children and of inter-

ventions that target only parents of children, in addition to Conceivably, the main therapeutic value of current treat-

interventions with surgery and drugs (37). The evidence ments may be the reduction in risks for cardiovascular

suggests that multi-component behaviour-change inter- and other comorbid conditions and improved quality of life

ventions may achieve small reductions in body weight for and psycho-social well-being. Significant improvements

children of all ages, with few adverse events reported. In in insulin sensitivity, blood pressure and lipid profiles have

addition, despite the small effects of multi-component be- been reported with even mild or moderate non-surgical

havioural interventions on BMI z-score, the reduction in weight loss (35). These observations may justify wider

risk for comorbid conditions is an important, achievable discussion and re-evaluation of current approaches that

result (35). Cardio-metabolic changes are related to re- appear to be less effective. As the evidence accumulates

ductions in fat mass, especially in the abdomen. As BMI and the problem is exacerbated, health care providers

is not a direct measure of body composition and fat mass may wish to consider new, more efficient treatment mo-

may be confounded with fat free mass, therapeutic op- dalities. The current gaps in childhood obesity manage-

tions should address body composition and comorbid ment are mainly in the areas of integrated care, personal-

conditions instead of only weight loss and BMI reduction. ized approaches and systems thinking that incorporates

individual, environmental and policy change.

A growing, rapidly changing portfolio of anti-obesity drugs

is being marketed as manufacturers continue to develop

new, safer, more tolerable medications that can also be 1.5 Towards integrated care in multiple

prescribed for children (which are not currently available) settings

(39). Pharmacological interventions for obesity in children

and adolescents have been assessed in a Cochrane sys- Childhood obesity management services may include

tematic review (40). Some of the trial drugs were used systematic screening, consistent criteria for diagnosis

off license (orlistat) or have been withdrawn (sibutramine, and assessment, stepwise care with clear pathways and

fenfluramine, benfluorex, dexfenfluramine and rimon- equal access and long-term follow-up. Establishing and

abant) in some countries. As there was no long-term organizing these services will probably place pressure on

follow-up and no data on safety, no conclusive recom- health care delivery systems, as they require dedicated

mendations could be made. Only orlistat, liraglutide and human and financial resources from an already stretched

naltrexone-bupropion have been approved for weight situation. Governments should therefore take a political

management in adults by the European Medicines Agen- decision to reorganize care and eventually to allocate ad-

cy, when used with diet and exercise. These medications ditional resources to tackle these issues.

are possible candidates for paediatric obesity treatment,

and short-term studies have been conducted of the safe- Although there is still lack of consensus on the definition

ty, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of 3.0 mg/ of “integrated care” (44), such care is attracting attention

day liraglutide in 12–17-year-old adolescents with obesity as a framework for better, more effective health care de-

and Tanner stage 2–5 (41). These studies demonstrated livery (45). For this publication, we defined an integrated

that the medication is well tolerated by adolescents, with approach as “a method incorporating diet, physical ac-

safety and pharmacokinetics profiles similar to those in tivity and mental health as well as environmental change

adults. These medications are not, however, the “silver and parenting practices”. Diet, physical activity and men-

bullet” but are designed to support individual attempts to tal health and the home, school and community envi-

change behaviour. ronments are separate but interconnected components

of childhood obesity management. Addressing all these

Surgery has been used, with behavioural change. Sev- components at the same time is likely to have comple-

eral safe, effective surgical techniques have been used mentary effects on weight gain reduction or weight main-

in the past 50 years; however, surgery is still not widely tenance. Integration is thus the “glue” for achieving com-

considered to be beneficial or safe for younger children mon goals and optimal results (45). When applied to

(42). Bariatric surgery is an effective intervention for losing health services, this refers to institutions, settings, provid-

weight and ameliorating obesity-related comorbid condi- ers, health and social services and the related systems in

tions, but it is associated with greater risks and higher which they operate.

52. Objectives and methods 6

The objectives of the project were to identify the ele- • To what extent do the current systems address ine-

ments and aspects of health system actions, promising qualities in health and the specific needs of groups with

examples and lessons from these experiences. The group low socioeconomic status?

based their work on the following questions:

• How do informants perceive the functioning of the sys-

• Which professionals are involved in childhood obesity tem, and what challenges have they identified?

management, and what is their role therein?

• Are there promising initiatives and practices in child-

• What are the clinical pathways for the management of hood obesity management?

childhood obesity, from screening to diagnosis, treat-

ment and follow-up? We reviewed childhood obesity management in 19 coun-

tries in the WHO European Region, mainly from answers

• In which settings is childhood obesity managed and to a questionnaire distributed to the principle investiga-

what are the entry points into the health system? tors of the WHO COSI who expressed their willingness

to contribute (Fig, 2). The countries were: Armenia, Aus-

• What are the provisions for long-term care and fol- tria, Denmark, England, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, It-

low-up? aly, Israel, Latvia, Malta, the Netherlands, North Mace-

donia, Norway, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia

• What are the funding arrangements for childhood obe- and Sweden. Slovenia also sent an example of a good

sity management, and what services are covered? practice, which is included in this report. The geographi-

cal coverage of the countries is limited with regard to the

• What support is available for childhood obesity man- 53 Member States in the WHO European Region, and the

agement? results are merely illustrative rather than representative of

the Region.

Fig. 2. Map of participating countries

7Mixed methods were used for data collection. A com- standardized responses from countries, the principal in-

prehensive literature review was undertaken by the main vestigators were encouraged to distribute the question-

researchers to identify key themes and to select coun- naire to various experts in childhood obesity management

tries for case studies. The themes identified provided the in their countries. They then collected and summarized

basis for the data collection forms (i.e. country question- the answers. For open-ended questions, they listed all

naire and semi-structured interview guide). We searched the answers they received; for pre-set answers, they sent

PubMed and Google Scholar with relevant subjects and back the consensus of a group of experts. If there was a

free text terms related to childhood obesity management. direct conflict (i.e. the answers contradicted each other),

The search results were limited to freely available full texts the principal investigator was asked to find agreement.

published in English in the past 10 years. We grouped

the articles by both country and theme (e.g. screening, Four countries (England, Hungary, Italy and Sweden),

primary care, community care). We also used supplemen- representing different geographical areas of the WHO Eu-

tary searching techniques, by following up articles cited in ropean Region and with different health systems, were

these papers and performing additional searches to ex- selected for more in-depth study in semi-structured in-

plore emerging themes further. terviews. The interview protocol and guide were devel-

oped and piloted by the Hungarian team between March

Eight broad themes were identified in the literature review, and May 2018. England, Italy and Sweden conducted in-

from which the framework of the country questionnaire terviews during the summer and autumn of 2018. Data

was developed. The main terms were defined to ensure collection was closed in mid-October. Annex 2 includes

common understanding by respondents. The framework more details of the methods used in each case country.

was then discussed and refined in an online consultation

among the research team, and the feedback was used In this document, results are usually reported first as col-

to finalize the document, which was sent to all COSI prin- lected via the questionnaire from 15 countries and then

cipal investigators in May 2018 (see Annex 1 for the fi- information from the semi-structured interviews. Unless

nal questionnaire). The first deadline was the end of May otherwise noted, the tables are based on the responses

2018, but as more countries expressed their intention to to the questionnaire. The case studies and country exam-

contribute we extended the end of data collection until the ples were either identified in the literature review or sug-

end of September 2018 to allow for holidays. Because gested by countries as practices that could inspire others.

of the complexity of the questionnaire and to ensure

89

3. Results 10

The 15 countries that participated in the questionnaire recognized as a chronic disease by both the responsible

survey were: Armenia, Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Ger- authority and health professionals in theory, the reality is

many, Israel, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, North Macedo- different, in terms of the probability of correct diagnosis

nia, Norway, Romania, San Marino, Serbia and Slovakia. or identification, particularly in primary care, and of the

COSI principal investigators were asked to invite a group availability of treatment and policy implementation. In It-

of representatives of childhood obesity stakeholders in aly, obesity is on a list for “essential levels of assistance”

their countries to fill in the questionnaire on the basis of specified by the Ministry of Health, as it is considered to

group consensus. The multidisciplinary teams generally be a lifestyle risk factor. Thus, each region is urged to de-

comprised representatives of four different professions. velop specific preventive activities. In practice, as in Hun-

The professions most frequently mentioned as answer- gary, childhood obesity is not considered or treated as a

ing the questionnaire were, in order: paediatricians, public chronic disease by most health care professionals. This is

health specialists, dietitians, representatives of the minis- true particularly in southern Italy, where the prevalence of

try of health or of education, paediatric endocrinologists, childhood obesity is so high that “health professionals are

GPs, psychologists, school doctors, health visitors and so used to being surrounded by children with overweight

researchers. The respondents typically worked in the fol- and obesity that they underestimate the problem”. This

lowing areas of the health care delivery system (in order of attitude raises concern, as it jeopardizes the likelihood of

frequency): specialized care, primary care, public health, early intervention. In England, stakeholders reported that

health authority, medical universities, school health and they considered that the central Government underesti-

community care. mated the complexity of obesity. They suggested that this

contributes to limit the urgency to act in the management

The number of experts who took part in the semi-struc- and treatment of childhood obesity. There was a sense

tured interviews ranged from 6 in Sweden to 20 in Italy, that the Government focuses primarily on prevention (as

with a total of 50 participants. Country coordinators were reflected in the recently launched Childhood Obesity Plan)

asked to involve experts representing various disciplines and has not taken similar steps to invest in management

in multiple care settings. The participants included re- and treatment.

searchers, ministry representatives, primary care paedia-

tricians (PCPs), paediatric endocrinologists, public health

specialists, dietitians, nurses, psychologists and health 3.1 The childhood obesity management

care managers. Most had several roles in the obesity system

management system.

3.1.1 Main professionals and other personnel in

Obesity was declared a disease by WHO in 1979 and by childhood obesity management

the American Medical Association in 2013. In 2015, the In the 19 participating countries, different professionals are

European Association for the Study of Obesity published involved at various stages of the management pathway,

a position paper in which they stated that childhood obe- and the types of professionals involved vary between and

sity is a chronic disease. The declaration of childhood within countries. In principle, activities associated with

obesity as a disease is important for a number of reasons. childhood obesity management are implemented in three

When a condition is defined as a disease by a responsible settings in the countries: in schools, in primary care and

authority, it can lead to the development of official pro- in specialized care (as inpatient or outpatient services).

tocols, organization of care and allocation of funding to Nurses and physicians usually play key roles in each set-

implement the protocol. Additionally, if childhood obesity ting. Although evidence suggests that childhood obesity

is managed as a disease by health care providers it may should be managed by teams of people in different dis-

be diagnosed and treated rapidly. As childhood obesity ciplines, not all the countries reported that professionals

tends to last into adulthood, early intervention is crucial for in various areas (dietitians, psychologists, physical ther-

reducing lifetime risks and burden. apists or exercise physiologists) are available in primary

care. The countries that reported that they had multidis-

In our survey, 13 of the 15 countries reported that both ciplinary primary care teams were Denmark, Estonia (not

the ministry of health and health professionals recognize in all locations), Israel, Malta, Netherlands, Romania (not

childhood obesity as a chronic disease, while in two (Den- in all locations), San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia and Swe-

mark and North Macedonia) it was not. Denmark report- den. In these countries, the additional team members in-

ed that, in line with recommendations from the Danish volved in childhood obesity management in primary care

Health Authority, professionals regard childhood obesity (besides doctors and nurses) were usually dietitians and/

as a risk factor; however, this opinion is not shared by all or psychologists. Exercise physiologists were more often

physicians. available in specialized care. The Netherlands is an ex-

ception, as a wide variety of professionals are available in

In the results of the semi-structured interviews, the team primary care, including in community services (see Fig. 3).

in Hungary reported that, although childhood obesity is

11Fig. 3. Professionals involved in the primary care team in the Netherlands

Social

Youth health worker

care nurse

Community

worker for

exercise

Youth health

care doctor

Youth

care worker

Multidisciplinary

Nurse-practioner

mental health primary care team

care in the Netherlands

General

practitioner

Physical

therapist

Remedial

teacher

Physiologist

Dietitian

Social workers are rarely involved in any phase of child- the responsibility and task of physical education teachers.

hood obesity management, and, if they are, it is usually Similarly, in Serbia, physical education teachers partici-

during long-term care and follow-up (e.g. in Estonia, Ro- pate in screening with primary care providers, although

mania). Exceptions are England, Israel and the Nether- their role is not widely recognized. At Italian national health

lands, where social workers were mentioned as part of service family care clinics, people receive advice and

primary care (the Netherlands), tier 3 services3 (England) counselling on their health and lifestyle, and children with

or specialized care (Israel). obesity and their families receive free basic recommenda-

tions on a healthy lifestyle, counselling, basic nutritional

We identified certain country-specific features in childhood advice and, if necessary, medications such as anti-dia-

obesity management infrastructure. In Denmark, school betic pills or antihypertensive drugs prescribed by a PCP

nurses known as “health visitors” are trained in perform- or specialist for complications of obesity. In Sweden, child

ing examinations and talking with schoolchildren and their health care centres play an important role in childhood

parents. In North Macedonia and Romania, screening is obesity management. More than 2000 primary care cen-

done with the help of public health specialists. Similar- tres provide primary preventive health care for children up

ly, in Norway, screening is done by nurses with an ad- to the age of 4 years (46). The centres are financed by

ditional master’s degree in public health (i.e. nurses with counties, are free of charge and cover 99% of children.

a nursing master’s degree in health promotion and pre- The centres are run by either a district nurse or a paedi-

vention). In Slovenia, screening of school-aged children is atric nurse, and family physicians or paediatricians act as

12 3

For details of tier 3 services, see the case study on p. 33.consultants. The care of older children is ensured in fam- governance enforcing it” (England). Insufficient coordi-

ily or residential health centres (vårdcentral), which have nation results in fragmented care and significant regional

both GPs and nurses. differences at every level of management. In Austria and

Germany, fragmented care for childhood obesity is part-

3.1.2 Structures and processes ly the result of the complexity of their health systems, in

3.1.2.1 Governance and organization of care which responsibilities are shared between national and re-

“Governance” in the health sector pertains to a wide range gional authorities.

of steering and rule-making functions of governments and

decision-makers for achieving national health policy ob- Respondents also mentioned elements that could im-

jectives conducive to universal health coverage (47). Gov- prove governance in their countries:

ernance is a political process for balancing competing in-

fluences and demands. It includes: maintaining a strategic • operational and centralized coordination of the entire

direction in policy development and implementation; de- system of screening, diagnosis and treatment (Italy);

tecting and correcting undesirable trends or distortions;

putting the case for health in national development; regu- • integration of health care service providers for children

lating the behaviour of a wide range of people, from health with overweight and obesity into one national network

care financiers to health providers; and establishing trans- (Austria, Italy and Serbia);

parent, effective accountability mechanisms. Beyond the

formal health system, governance involves collaboration • a national database of obesity management service

with other sectors, including the private sector and civil providers, with national evaluations (Denmark);

society, to promote and maintain population health in a

participatory, inclusive manner. Good care depends on • obesity registries analogous to cancer registries (Ger-

good governance. Therefore, care providers must ensure many and Serbia);

that their patients receive safe, good-quality care; clearly

allocate responsibility and tasks within the organization; • interconnection of primary and specialized care (Aus-

and ensure good financial management (48). tria and Italy);

None of the questions on the questionnaire explicitly asked • direct connection between hospital treatment and so-

about governance, but some parts addressed aspects cial care (Denmark); and

or elements of the process, e.g. “Who is responsible for

the organization and coordination of care of overweight •a national programme with relevant indicators and

and obese children in your country?”. Respondents also monitoring (Italy).

commented either directly or indirectly on governance

throughout the questionnaire. In the interviews, a section A number of mechanisms were identified that could help

was dedicated to overall management and coordination, to overcome fragmentation of services.

including questions such as “Which are the coordinating

bodies and what are their respective roles and respon- In Israel, a national registry of bariatric surgery was es-

sibilities?”. The existence of policies or other strategic tablished at the Israel Center for Disease Control in order

documents and their implementation in practice were not to compile data on all bariatric surgery performed in all

covered. Bearing in mind these limitations, the findings treatment centres in the country. The registry began op-

with regard to governance and organization of care can eration in June 2013 and receives information from 28

be summarized as below. medical centres; data on pre- and post-surgical indica-

tors are received from health maintenance organizations

In general, governance and coordination among providers (HMOs) and from questionnaires sent to people who have

in childhood obesity management appeared to be prob- undergone bariatric surgery. In Denmark, a national net-

lematic in all the participating countries. Some countries work of primary and secondary health care professionals

explicitly reported a “missing structured system” (Austria), working with children and adolescents with overweight or

“lack of systematic approach for childhood obesity care” obesity was established in 2013 (49). The members are

(Estonia), inexistent system (Latvia), “no national coordi- nurses, doctors, dietitians, physiotherapists, psycholo-

nation of the paediatric obesity centres scattered over gists, secretaries, social workers, health care practitioners

the country. Each centre works in isolation” (Italy), “lack and exercise counsellors. Initially, members met once a

of centralized coordination and support” (Sweden), “co- year for 1 day to share their experiences. Since 2015, the

herent intersectoral strategy and related action plans are event has lasted for 2 days, and members discuss treat-

lacking that would coordinate the actions against child- ment options, results, various interventions and research

hood obesity in an integrated and complex manner” (Hun- projects and develop new projects for treatment of over-

gary) and “whilst the obesity care pathway is depicted, weight in children and adolescents. In the Netherlands,

there is little operational clarity, financial commitment or there is a national multidisciplinary model for integrated

13You can also read