Late Whiplash Syndrome: A Clinical Science Approach to Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Management

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

TUTORIAL

Late Whiplash Syndrome: A

Clinical Science Approach to

Evidence-Based Diagnosis

and Management

Keith Poorbaugh, PT, ScD, CSCS, FAAOMPT*,†; Jean-Michel Brismée, PT, ScD,

OCS, FAAOMPT†,‡; Valerie Phelps, PT, OCS, FAAOMPT*,†; Phillip S. Sizer Jr,

PT, PhD, OCS, FAAOMPT†,‡

*Advanced Physical Therapy, Anchorage, AK; †International Academy of Orthopedic

Medicine, Tucson, Arizona; ‡Texas Tech University Health Science Center, Lubbock, Texas,

U.S.A.

䊏 Abstract: The purpose of this article is to narrow the gap among industrialized nations and less developed countries

that exists in the clinical application of scientific research and suggests another factor that could influence one’s interpre-

empiric evidence for the evaluation and management of late tation of symptoms’ chronicity associated with Late Whiplash

whiplash. Considering that 14% to 42% of patients are left Syndrome. There are no gold standard tests or imaging tech-

with chronic symptoms following whiplash injury, it is unlikely niques that can objectify whiplash-associated disorders. A lack

that only minor self-limiting injuries result from the typical of supporting evidence and disparity in medico-legal issues

rear-end impact. As psychosocial issues play a role in the have created distinct camps in the scientific interpretations

development of persistent whiplash symptoms, discerning the and clinical management of late whiplash. It is likely that

organic conditions from the biopsychosocial factors remains a efforts in research and/or clinical practice will begin to explain

challenge to clinicians. The term “whiplash” represents the the disparity between acute and chronic whiplash syndrome.

multiple factors associated with the event, injury, and clinical Recent evidence suggests that Late Whiplash Syndrome

syndrome that are the end-result of a sudden acceleration- should be considered from a different context. The purpose of

deceleration trauma to the head and neck. However, conten- this article is to expound on several of the significant findings

tions surround the nature of soft-tissue injuries that occur in the literature and offer clinical applications for evaluation

with most motor vehicle accidents and whether these injuries and management of Late Whiplash Syndrome. 䊏

are significant enough to result in chronic pain and limita-

tions. The stark contrast in litigation for whiplash that exists Key Words: Facet joint, Injury, Intervertebral disc, Joint

instability, Neck, Pain, Spine, Whiplash

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Phillip S. Sizer Jr, PT,

PhD, OCS, FAAOMPT, Professor and Program Director, ScD Program in PT,

Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, School of Allied Health Sciences, INTRODUCTION

Texas Tech University Health Science Center, 3601 4th St., Lubbock, TX

79430, U.S.A. E-mail: phil.sizer@ttuhsc.edu.

Late Whiplash Syndrome has been described as a disor-

Submitted: July 5, 2007; Revision Accepted: September 20, 2007 der that is characterized by a constellation of clinical

profiles including neck pain and stiffness, persistent

© 2008 World Institute of Pain, 1530-7085/08/$15.00

headache, dizziness, upper limb paresthesia, and psy-

Pain Practice, Volume 8, Issue 1, 2008 65–89 chological emotional sequelae that persist more than66 • poorbaugh et al. 6 months after a whiplash injury.1,2 Because of the Selected Pathoanatomy and Pathomechanics of Late myriad of signs and symptoms with which the patient Whiplash Syndrome is capable of presenting, one must consider the many Late Whiplash Syndrome involves a myriad of symp- possible different presentations the condition can toms with considerable overlap between organic and produce. psychosocial origins.23 A single anatomical site of whip- Whiplash is the most common cause of neck pain lash injury has yet to be identified.24 The symbiotic associated with chronic musculoligamentous condi- relationship among the intervertebral disc, uncoverte- tions.2,3 It is estimated that 6.2% of all Americans bral joints, and zygapophyseal joints in the cervical (approximately 15.5 million) currently suffer from spine lends these structures to complex mechanical Late Whiplash Syndrome.2,4,5 Annual medical costs loading in response to injury. Because structures such as associated with whiplash injuries are estimated to the intervertebral discs and zygapophyseal joints are range from $3.6 billion in the United Kingdom to $10 extensively innervated,25,26 they could serve as primary billion in the United States.2,6 The high incidence and pain generators in Late Whiplash Syndrome.27–29 For exorbitant costs have elevated whiplash to interna- example, cervical facet joints have been implicated as tional epidemic status. the cause of neck pain in 60% of a study group with Late Whiplash Syndrome involves a broad spectrum chronic pain after whiplash exposure.30 of symptoms ascribed to few other conditions or inju- A primary function of the cervical spine is to facilitate ries that may persist for months or years after the and control motion of the head and neck, while disrup- incident.7–9 It is estimated that only 10% of vehicle tion of the cervical kinematics may contribute to late occupants exposed to a rear-end collision will develop whiplash symptoms.31 Although overall cervical move- whiplash syndrome.10 Of these, the incidence of ment remains within physiological limits during a low chronic neck pain ranges from 18% to 40%.10 velocity impact, injury appears to emerge in response to However, when whiplash symptoms do occur, a delay pure posterior rotation, anterior shear, and upward in symptom onset is expected. Selected studies have thrust of the segment about an abnormally high instan- demonstrated that the delay in the onset of whiplash taneous axis of rotation (IAR).32 The role of the IAR in symptoms can range from 1 hour to several days after whiplash-related pathology is apparent, as abnormal the accident.11–13 Moreover, patients that seek medical instantaneous axes have been detected in at least one treatment for acute whiplash injuries face a 33% segmental level within almost half of patients examined chance of developing Late Whiplash Syndrome at with a similar history.33 more than 30 months after injury.4,5 However, when Inertial loading of the trunk and head appears to presented with chronic symptoms and few causal contribute to the consequences of whiplash injury factors, there is a tendency to suspect underlying non- mechanisms.6,34,35 Inertial loads experienced during a organic basis for the patient’s symptoms. whiplash event create an elongated S-shaped curve in Structural damage that persists beyond the average the cervical spine that is considerably different from the healing time for soft-tissue injuries is not common typical lordotic C-curve that is witnessed in the cervical among patients with whiplash.14 Thus, prolonged dis- spine at rest.36,37 This aphysiological behavior produces ability and limited treatment effectiveness have invoked pathomechanical tissue responses and potential clinical conflicting views on the role of psychological factors consequences that have been previously described.38 For and litigation in a patient’s recovery. Various investiga- example, trauma may injure cervical facet capsular liga- tors have reported the medico-legal aspects of chronic ments that have been shown to suffer injury under com- whiplash and have challenged the organic causes for this bined shear, bending, and compression loads witnessed disorder,15–20 exemplified by the strong association in a whiplash event.39 found between retention of a lawyer and delayed recov- The end result of the early phase of whiplash involves ery from whiplash injury.14 Even worse, unresolved anterior separation of the vertebral bodies, shear of the matters with an insurance provider are strongly associ- posterior annulus, and compression of the zygapophy- ated with a poor outcome from whiplash-associated seal joints, lending to tears of anterior annulus fibrosis disorders (WAD) as far out as 3 years after the injury.21 and bony contusions or fractures of the zygapophyseal Thus, it has been contended that Late Whiplash Syn- joint articular processes.40 Accompanying this response drome should be considered as much a behavioral dis- are strain levels in the upper cervical spine ranging from order as a chronic injury.22 15% to 26% in the posterior longitudinal ligament and

Late Whiplash Syndrome • 67

intervertebral discs. Moreover, the order of segmental trigeminal nerve located in the upper cervical segments of

recruitment during the whiplash even might lend the spinal cord has been implicated in the cephalic symp-

selected segments to more stress than others, especially toms associated with whiplash. The trigeminal nucleus

witnessed at the C5-6 segmental level.40 These condi- is located in the upper cervical segments of the spinal

tions could persist for an extended period of time, cord.50 Thus, any increased afferent signaling from

lending to the development of the symptoms associated selected structures innervated by these segmental nerves

with Late Whiplash Syndrome. could trigger cervicogenic headache in this population.50

Integrity of the cervical musculoskeletal complex These segments receive afferent information from the

depends on three subsystems: bony architectural struc- distribution inherent to the trigeminal nerve and upper

tures, capsuloligamentous systems, and neuromuscular cervical nerves. Because chronic pain triggers the release

control mechanisms.41,42 Each of these systems could be of nerve growth factor and increased interneuron

implicated in Late Whiplash Syndrome. For example, growth, there is reasonable basis for afferent convergence

disc pathology can serve as a contributing factor in within the cervical trigeminal nucleus. The potential

the development of chronic symptoms after whiplash neural adaptations and the increased incidence of con-

injury,43 where trauma to the cervical spine may accel- vergence serve as physiological bases for cervicogenic

erate normal age-related disc deterioration.44,45 Peak headaches associated with Late Whiplash Syndrome.

disc strains appear to occur early in the second phase of Women may be at greater risk for developing Late

whiplash, where disc shear strain is highest in the pos- Whiplash Syndrome, and this predisposition may be

terior annulus and axial elongation is greatest at the related, in part, to differences in anatomical and patho-

anterior annulus, especially at the C5-6 segment.46 mechanical tissue responses. There is more than 2:1

The stability of the functional spinal units for the preponderance for women to suffer whiplash injuries

cervical spine is achieved through a symbiotic relation- when compared to their male counterparts.51 The

ship of all supporting structures. Therefore, disc changes Quebec Task Force on WAD reported that females sus-

not only produce disc-related symptoms, but also con- tained 60% of all injuries in a cohort of 3014 whiplash

tribute to the development of pain generators in other patients.52 Not only are women more likely to sustain a

tissues. Loss of integrity or segmental stiffness from a whiplash injury, but they also may be less likely to

disc injury can cause undue stress to other supporting recover.53 However, the explanation for these differences

structures, such as the zygapophyseal joint. This is controversial.49,52–54 Pettersson observed that the

behavior supports the contribution of the zygapophy- spinal canal of female patients was significantly nar-

seal joint to the symptoms associated with Late rower than that of males,55 suggesting one of the causal

Whiplash Syndrome.30 factors that may explain this disparity.

Of equal importance is the impact that whiplash has Other explanations for the higher incidence of whip-

on the cervical neural structures in response to changes lash injuries among women point to gender-specific seg-

in their surrounding architectural container. A rear-end mental spinal stability and tissue response to injury.

impact causes the diameter of the spinal canal to Whiplash injury appears to cause a greater instance of

decrease gradually at C2-3 and C3-4 but remains nearly segmental hypermobility in women with WAD in com-

constant from C4-5 to C6-7.47 Hyperextension of the parison to women with idiopathic onset of neck pain,

lower cervical spine occurs in the early phase of whip- especially in combined rotational and translational

lash and results in a narrowed spinal canal, because of hypermobility in the middle cervical spine segments.56

decreased spinal canal diameter and increased cord Similarly, female cadaveric specimens demonstrated sig-

diameter.48 This decrease in the sagittal diameter of the nificantly greater dorsal shear motion at C4-5 during

canal may contribute to symptomology in Late Whip- simulated whiplash when compared to males.36

lash Syndrome. A study of 48 consecutive whiplash Females may be predisposed to greater incidence in

patients demonstrated that spinal canal was significantly facet injury during whiplash. This may be related to less

narrower in patients with persistent symptoms vs. a extensive cartilage available to cushion the subchondral

recovered group, especially in those patients with pre- bone, accompanied by an increased cartilage gap in the

existing cervical spondylosis.49 dorsal facet observed in females.29 Simulated rear-

Any of the structures innervated by the upper cervical impact using human volunteer subjects showed greater

segmental nerves can be influenced by a whiplash event, degrees of cervical retraction in females who were

lending to prolonged symptomology.50 For instance, the unaware at time of rear-end impact.57 This additional68 • poorbaugh et al. translation could result in increased strains experienced patients who underwent spondylodesis for cervical dys- by restraining structures, such as the facet capsule. function.65 Biopsies of ventral neck muscles (sterno- Soft-tissue injuries that are common with a rear-end cleidomastoid, omohyoid, longus colli) and dorsal neck impact could lead to spinal column instability, because muscles (rectus capitus posterior major, obliqus capitus of a loss of integrity in the spinal stabilizing system.41,42 inferior, splenius capitus, and trapezius) were taken Simulated frontal impacts demonstrated strains in from 64 patients who underwent spondylodesis for cer- excess of the physiologic limits for supraspinous and vical dysfunction (whiplash and rheumatoid arthritis). interspinous ligaments, as well as ligamentum flavum.46 The same pattern of muscular transition was found in Disruption of these soft-tissue structures could lead to patients with soft-tissue injuries of the neck (whiplash). segmental instability, which could result in pain associ- In the ventral muscles, transformation was more preva- ated with aberrant or excessive motion. lent among women and in patients with shorter dura- The stability of the craniocervical region is afforded tion of symptoms (less than 2 years). Muscles in which by the alar and transverse ligaments, and trauma to transformations had ceased displayed a significantly these structures can contribute to Late Whiplash Syn- higher percentage of type IIB fibers than were found in drome.58,59 These ligaments have been thoroughly muscles with ongoing transformations. While the stimu- described and can be visualized in a previous article, but lus that triggers this transformation is not fully under- a brief description is merited.60 The occipital portion of stood, the investigators suggested that it could be the the alar ligament courses from each of the occipital result of factors related to their pathological state, condyles to the posterior aspect of the dens, whereas the including repeated muscle activity, increased muscular atlantal portion of the alar ligament connects the atlas tension, decreased or absent physical activity and/or with the ventral aspect of the dens.60 The alar ligaments pain. These factors appear to lend the transitional fibers not only provide the primary restraint to lateral flexion (type IIC) in the region to transforming into the type IIB and rotation but also act as secondary restraints to fibers. A higher ratio of type IIB fibers indicated that sagittal flexion in this region. Together, these ligaments the muscles transformed from “slow oxidative” to serve as a primary restraint to extension, axial rotation, “fast glycolytic” in nature, suggesting a decrease in the and sidebending in the upper cervical spine.61 When the muscles’ resistance to fatigue. A loss of endurance head is rotated and flexed, the alar ligaments are maxi- among local muscles responsible for segmental control mally stretched and susceptible to injury from sudden may impair segmental spinal stability because of acceleration during a vehicle accident.58,59 Complete reduced neuromuscular control. This may be one of the ruptures of the alar ligament are rare in survivors of factors that causes muscle spasms in the presentation of whiplash injury. However, suspected ligamentous Late Whiplash Syndrome. lesions of the craniocervical region should be evaluated with clinical manual testing38 and functional stress Resultant Pathology radiographic imaging.62 Moreover, the transverse liga- Investigators have examined the soft-tissue injuries that ment of atlas (TLA) stabilizes the atlantoaxial joint by are sustained during whiplash. Deng et al. suggested five securing the dens against the inner aspect of the atlas, possible whiplash injury mechanisms: (1) excessive cer- where it functions to hold the odontoid in place and vical hyperextension, (2) muscle tensile forces, (3) facet prevent posterior translation of the process into the joint shearing and loading, (4) facet capsular impinge- spinal canal during cervical flexion.63 Lesions of the ment because of local tilting and compression, and (5) TLA are life-threatening and require immediate referral dorsal root ganglion (DRG) deformation during tran- to a specialist for further evaluation and management. sient pressure increases in spinal canal.66 Cryomicro- The locomotor system works along with ligaments to tome examination of cadaveric specimens exposed to stabilize segments of the cervical spine and whiplash can whiplash trauma revealed extensive tissue abnormali- possibly produce dysfunction in this system, lending to ties, such as anterior annulus tears, disruption of ante- subsequent instability and latent symptoms. Neck rior longitudinal ligament, separation of ligamentum muscle dysfunction is an early correlate of subclinical flavum with hematoma, and capsular tears of zygapo- neck pain.64 Muscle spasms have the capacity to reduce physeal joint. These injuries, which were mainly con- range of motion (ROM) and to alter IARs.33 In addition, fined to the lower cervical spine, reflect anatomical a pattern of muscle fiber transformation from “slow changes that could partially explain the persistence of oxidative” to “fast glycotic” has been observed in clinical symptoms.6

Late Whiplash Syndrome • 69 The zygapophyseal joint appears to be the single most clinicians fail to consider the prevalence of zygapophy- common pain generator associated with chronic neck seal joint pain in Late Whiplash Syndrome, it is possible pain after whiplash.28,30 Lord found that the cervical that many of patients may go undiagnosed.27 The inabil- zygapophyseal joint was the primary cause of chronic ity of imaging to adequately detect injuries of the zyga- neck pain after whiplash in 60% of their subjects in a pophyseal joints after whiplash increases the diagnostic double-blind, placebo-controlled study.30 However, in a controversy among clinicians. Yet, further evidence for study of 318 patients suffering chronic neck pain (symp- joint pain has been demonstrated using short vs. long toms longer than 6 months), Aprill and Bogduk observed lasting diagnostic blocks of the cervical zygapophyseal a different pattern of zygapophyseal joint involvement joints.28 Using this approach, Barnsley et al. demon- determined through provocative discography and cervi- strated a 40% to 68% prevalence of zygapophyseal cal zygapophyseal joint blocks.27 They found that 53% of joint pain, where the most common levels for symptom- the patients suffered a symptomatic disc, while 26% atic joints were C2-3 and C5-6. demonstrated a symptomatic zygapophyseal joint either The role of disc pathology in whiplash injuries is in isolation or in conjunction with a symptomatic disc. relatively clear. The intervertebral discs of the cervical A comprehensive evaluation of zygapophyseal joint spine receive innervation from the ventral primary ramus kinematics and capsular ligament strains in whole cer- via the sinuvertebral nerves.73 These nerve fibers enter the vical spine specimens with muscle force replication disc in the posterolateral direction and are present models during simulated whiplash supports that the throughout the annulus but are most numerous in the zygapophyseal joint is at risk for injury.67 The mecha- middle third of the disc’s annular material.25 The poste- nism of zygapophyseal joint injuries during whiplash rolateral region of the disc contains receptors resembling may involve excessive articular compression and/or cap- Pacinian corpuscles and Golgi tendon organs demon- sular strain associated with aphysiological translation strating a mechanoreceptive function.25 Disc pathology and loading.67 This strain easily triggers cervical pain, as could potentially produce persistent symptoms after the joint capsule is well innervated by the medial whiplash injury by virtue of irritation to these nerves.73–75 branches of the dorsal rami, where each medial branch The primary mechanisms for discogenic neck pain segmentally innervates multiple zygapophyseal joints.68 associated with Late Whiplash Syndrome are strain or Mechanoreceptors are present within the joint capsule tears at the anterior annulus and strain of the posterior that may respond to noxious stimuli from excessive longitudinal ligament when stretched by a bulging capsular loading.69 disc.47 The integrity of the disc may be compromised The S-curvature of the cervical spine during the early during the whiplash injury and lead to acute injury or phase of the whiplash event causes compression in the accelerated disc degeneration. Without surprise, a sig- dorsal region of the zygapophyseal joint accompanied nificantly higher rate of disc degeneration was found in by ventral joint distraction.36 As a consequence, zyga- whiplash patients 10 years after the accident when com- pophyseal capsular strain occurs in the second phase of pared to age-matched controls.45 whiplash because of the separation of the joint surfaces. Using whole cervical spine specimens, Panjabi et al. If a whiplash event is severe enough to injure the joint found that the greatest strains occurred at the posterior capsule, zygapophyseal capsule overstretch is a possible region of the C5-6 disc during simulated whiplash.46 cause of persistent neck pain.70,71 These data suggest that the C5-6 disc is the most Segmental instability can develop in a whiplash common location for disc lesions in Late Whiplash Syn- event and complicate zygapophyseal involvement. drome. Clinically confirming this finding, Pettersson When present, this segmental compromise can produce combined clinical examination and magnetic resolution excessive segmental translation. Besides creating pain imaging (MRI) findings to evaluate 39 whiplash patients from abnormal loading, this excessive motion at a facet within 11 days of injury and at a 2-year follow-up.43 joint that exhibits degenerative articular processes could This prospective study demonstrated that 25% of the cause irritation of the medial branch of the dorsal ramus whiplash patients had positive MRI findings for disc as it courses dorsolaterally around that process.72 pathology, mainly witnessed at C4-5 and C5-6. Painful zygapophyseal joints associated with Late Whiplash Syndrome can be challenging to manage. Cli- Whiplash-Related Sensorimotor Control Deficits nicians can implement joint-specific mobilization to a Late Whiplash Syndrome is associated with disturbances painful segment to reduce pain and normalize motion. If in the sensorimotor control system.76 Soft-tissue injuries

70 • poorbaugh et al.

during the whiplash event appear to create pathome- The longus coli has been shown to play a key role in

chanical changes in segmental control. Thus, a whiplash the stability and control of the head and neck. A study

injury can cause microtrauma to the high density of of 36 healthy subjects utilized computerized tomogra-

muscle spindles that act as receptors for proprioception phy to compare muscle force and cross-sectional area of

and provide afferent information about extent and rate neck muscles in relation to cervical spine lordosis and

of change in muscle length, thus impairing the integrity of length.83 The longus coli was found to provide support

the functional spinal unit.77 Similarly, whiplash-asso- of the cervical lordosis and withstand physiologic loads

ciated local pain and muscle inflammation may inhibit presented by the head and extension moment generated

gamma-motorneuron discharge that could degrade the by contraction of the dorsal neck muscles. This postural

accuracy of proprioceptive information relayed to the function of the longus coli is complemented by the mul-

central nervous system by the muscle spindles.78 The tifidus muscles.84 Together, these muscles form a sleeve

ability to reproduce head motions requires integration of that encloses and stabilizes the cervical spine in all posi-

proprioceptive information with neuromuscular control. tions of the head.83 Patients with Late Whiplash Syn-

These impairments can lead to control deficits. For drome demonstrate performance deficits during the

example, Loudon et al. found that the ability to replicate craniocervical flexion test, indicating dysfunction or

a target position through neck rotation was compro- impaired ability to activate the deep cervical flexor

mised in chronic whiplash patients.78 muscles that include the longus coli.85

The total range of each rotatory and translatory move- Chronic Whiplash Syndrome can disturb an individu-

ment observed in the cervical spine can be divided into al’s complex postural control system. Chronic WAD

neutral and elastic zones.79 The neutral zone involves the leads to a characteristic pattern of trunk sway that is

range of movement that occurs with minimal resistance different from other patient groups with balance disor-

from physiological constraints, while the elastic zone is ders, where chronic whiplash patients exhibit trunk

encountered at the end of the range where tissues tighten sway for stance tasks and complex gait tasks that

and constrain motion. The evaluation of the neutral and required task-specific gaze control. These results suggest

elastic zones within the rotatory and translatory motions a pathological vestibular–cervical interaction, making it

of a moving segment is a more sensitive parameter detect- difficult for chronic whiplash patients to integrate the

ing changes caused by traumatic injury than a simple visual, vestibular, and neck proprioceptive signals

measure of ROM.80 Simulated injury of the spine has needed for generating appropriate balance control

been shown to cause an increase of the neutral zone mechanisms.24

before any significant changes in the ROM were

observed.81,82 A loss of segmental constraint in the elastic Neurophysiological Adaptation

zone with an increase in the neutral zone can produce Chronic whiplash patients may experience widespread

cervical segmental motion control loss, constituting the sensory hypersensitivity associated with neurophysi-

segmental instability that can persist after whiplash ological sensitization. Scott et al. conducted a case

trauma and a potential etiology of the pain associated control study of 29 subjects with chronic WAD, 20

with Late Whiplash Syndrome. subjects with chronic idiopathic neck pain, and 20 pain-

Zhu et al. found that cadaveric cervical spine speci- free volunteers.86 Patients with whiplash were the only

mens responded to high-speed axial trauma in a manner group to demonstrate a generalized hypersensitivity to

that demonstrated multidirectional movement control pressure, heat, and cold stimuli independent of anxiety

loss and resultant instability.82 Although late whiplash levels. A prolonged and continued barrage of afferent

patients often suffer a reduction in total ROM, the nociceptive stimuli is capable of leading to peripheral

neutral zone increases even in the absence of observable and central sensitization.87

anatomic lesions through imaging.41,42 The neutral zone

harbors greater possibilities for spinal injury, leaving the Peripheral Sensitization. The initial tissue injury asso-

spinal segment poorly guided by supporting structures ciated with whiplash may trigger an inflammatory

through the movement sequence and setting the stage response that can induce sensitization of peripheral

for aberrant motion control. The segmental instability nerves. The release of potassium ions, substance P,

that can accompany Late Whiplash Syndrome could bradykinin, prostaglandins, and other cytokines pro-

produce a painful clinical profile with latent, subtle soft- duces a local sensitization.88 This chemical sensitization

tissue trauma.34 increases the activity of “silent” nociceptors, producingLate Whiplash Syndrome • 71

clinical hyperpathia that has been observed in patients appreciable hypersensitivity of the nociceptive system to

suffering from chronic WAD. Moreover, gene expres- peripheral stimulation.91

sion is induced in the DRG because of the peripheral

histiochemical response. This leads to increased synthe- Role of Psychological Distress

sis of peripheral receptors that equates to increased sen- An account of psychological distress among whiplash

sitivity of the nociceptive afferent system.89 Peripheral patients with different levels of pain and disability dem-

sensitization results in an increased nociceptive input to onstrated that all patients exhibited both impaired motor

the spinal cord.90 Even if the original injury involves an function and varying degrees of psychological distress.

isolated site or tissue, sensitization can lead to diffuse Patients with moderate and severe levels of pain showed

symptoms that imitate a more severe and broad sweep- greater psychological distress and generalized hypersen-

ing condition. sitivity to a variety of stimuli than those patients with

mild symptoms.96 This likely has a neurogenic origin, as

Central Sensitization. Central sensitization can be the force generated with whiplash is capable of causing

interpreted as a central nervous adaptation to the pre- brainstem lesions, cerebral concussion, and stretching of

viously described, prolonged peripheral sensitization cranial nerves.97 These changes may account, in part, for

event, and resulting persistent afferent signaling within the psychological changes demonstrated in selected cases

various central nervous system locations, including of Late Whiplash Syndrome.

the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Chronic whiplash Gargan et al. studied 50 consecutive patients after

patients display pain hypersensitivity because of an rear-end vehicle collisions, recording their symptoms

alteration of the central processing of sensory input. and psychological status. For psychological status, the

This condition appears to be more than a simple psy- investigators used the General Health Questionnaire to

chogenic event.91 A reliance solely on psychological assess factors related to somatic response, social rela-

factors as an explanation for central sensitization tions, presence of insomnia, and depression.98 They dis-

ignores the prevailing evidence that injury and tissue covered that the severity of symptoms after a whiplash

damage induces neural hypersensitivity within the injury appears to be related both to the physical restric-

central nervous system. It is suggested that central tion of neck movement and the accompanying psycho-

hypersensitivity can be prevented or resolved with logical disorder.

the following management approaches: interventional Whiplash sufferers’ involvement in litigation regard-

block to reduce nociceptive input from the injured areas; ing their cases gives cause for suspicion that malingering

pharmacological intervention to impact central nervous or secondary gain is a contributing factor to the recog-

system mechanisms that underlie central hypersensitiv- nizant nature of the symptoms.21 Noncompliance or

ity; and pharmacologic or psychological intervention to nonadherence should not be surprising to the clinician,

affect the descending modulatory system.90 especially when a patient is frustrated with being sent to

Reduced cortical inhibition and amplified sensory treatments that are less probable to succeed.99 In this

response involve adaptations in multiple neurophysi- light, malingering is likely not a medical diagnosis, but

ological processes. Prolonged afferent nociceptive input rather should be considered a clinical opinion.99 Wallis

may lead to increased excitability of central afferent and Bogduk100 compared the psychological profiles, as

pathways.92 Activation of voltage-gated channel recep- well as patient responses on pain rating scales, of

tors involves the entire spinal cord and supraspinal chronic WAD patients vs. students instructed to simu-

centers in addition to the neural structures connected to late chronic pain. They concluded that it was quite

the original site of the initiating lesion.93 Increased difficult for an individual to fake a psychological profile

peripheral nociception leads to the increased release of typical of a chronic WAD patient.

substance P,88,94 calcitonin gene-related polypeptide,70,94 The impact of litigation on whiplash patient recovery

and other substances that sensitize the postsynaptic is controversial. In a large, population-based sample, the

membranes in both the peripheral and central nervous accident impact direction was not a determinant of the

system. Thus, peripheral sensitization is responsible for reported symptoms following the incident, whereas

primary hyperalgesia, as well as triggering secondary litigation status was a determinant.14 Alternately, the

hyperalgesia associated with central sensitization.95 response to radiofrequency (RF) medial branch neuro-

These changes have been observed in patients with tomy was prospectively compared in two groups of

chronic neck pain following whiplash, suggesting an whiplash patients (litigant or nonlitigant) with persis-72 • poorbaugh et al.

tent whiplash symptoms that were refractory to prior behaviors and distress associated with somatization,

conservative treatments.54 There was no significant dif- which can be interpreted as the patient’s belief that

ference between the two groups in the degree of symp- something is causing pain in the head or neck, thus

toms or response to treatment, where both groups complicated by the pain-impaired cognitive functioning

experienced significant and equivalent pain reduction and subsequent insecurity. Eventually, depression devel-

with the selected treatment. Thus, the authors refuted ops as the patient concludes that the pain is permanent.

the contention that litigation exacerbates whiplash This realization triggers hostility, especially if the acci-

symptoms, suggesting that a consideration for whiplash dent was not the patient’s fault, or when medical science

injury only as a secondary gain syndrome and a denial offered no explanation or cure.109

of treatment based on a presumption of malingering

could create a grave injustice to patients. CLINICAL EXAMINATION OF LATE WHIPLASH

Ferrari and Russell asserted that there are different SYNDROME PATIENTS

rates of chronic whiplash in countries other than the While a myriad of signs and symptoms can be observed

United States and that chronic injury-related damage in Late Whiplash Syndrome, neck pain and headache

cannot account for the wide differences.16,101 Conversely, compose the cardinal clinical features and are best pre-

the role of litigation may account for these differences, dicted based on severity of the initial injury.107,110 Accu-

as the use of litigation is relatively low for all purposes rate determination of the pain generators responsible for

in undeveloped countries. Moreover, an ongoing dispute the symptoms associated with whiplash can be arduous

for persistence of whiplash symptoms being mired in and no single diagnostic feature can completely describe

the legal system is associated with increased duration the atypical presentation of patients involved in motor

of symptoms.102,103 For example, in Finland, a poor vehicle accidents. However, the patient’s reported pain

outcome at 3 years after whiplash injury was signifi- intensity soon after the accident has been deemed as one

cantly related to whether the injured persons had unfin- of the few prognostic factors linked to clinical manage-

ished matters with the insurance company.21 ment outcome, where a more severe pain intensity is

A number of studies demonstrate convincing evi- linked with persistent symptoms and the development of

dence of psychological distress as a contributing factor Late Whiplash Syndrome.53,87

and possibly the determining factor for whiplash Minor cervical spine injuries are defined as injuries

outcome.15,16,101,104–107 However, there is no conclusive that do not involve a fracture.34 This broad description

evidence that an individual’s psychological status is encompasses all of the potential injuries described to

solely responsible for the development or outcome of this point. Of course, the connotation of a minor injury

Late Whiplash Syndrome. In addition, there is no special is that it should heal relatively quickly with little or no

psychiatric profile that exists for this disorder. Finally, intervention. A typical example of this prognostic

the psychiatric outcome of whiplash sufferers is no dif- expectation is the clinical symptoms of muscle spasm

ferent from other types of injuries caused by road traffic and point tenderness.

injuries.108 The Quebec Task Force on WAD graded whiplash-

Posttraumatic stress disorder occurs in roughly 10% related disorders based on severity and clinical pre-

of car accident survivors during the first year after the sentation, which has been previously described

accident.108 Thus, it is important for the clinician to (Table 1).38 The risk for WAD at follow-up ranging from

appreciate the interaction of physical and psychological 6 to 24 months after injury increases with higher WAD

factors in determining the latent outcome of whip-

lash.108 It is highly plausible that many conditions have

a certain degree of psychological distress that impacts Table 1. Grades of Whiplash-Related Disorders

the person’s physical response to the injury. Patients According to the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash

Associated Disorders (WAD)

with chronic neck pain and headache after whiplash

injury have been shown to exhibit psychological profiles Grade Description

that are similar to patients with chronic neck pain alone. 0 No neck symptoms or physical signs

In their comparison of chronic whiplash patients and 1 Neck pain, stiffness, or tenderness only; no physical signs

chronic neck pain, Wallis et al. reported that a reactive 2 Neck symptoms and musculoskeletal signs

3 Neck symptoms and neurological signs

pattern of distress was exhibited among both groups.109 4 Neck symptoms and fracture or dislocation

This secondary response can involve fear avoidanceLate Whiplash Syndrome • 73

grade classification.111 While the Quebec Task Force fractures of articular cartilage.115–119 While cervical spine

grading scheme offers selected guidelines for classifying imaging can give an appreciation of age-related changes

whiplash patients based upon their clinical presentation, that have the same prevalence in asymptomatic indi-

it offers little guidance to differentiate the underlying viduals,49,120,121 it is possible for lesions to exist in the

cause of the chronic whiplash patient’s conditions. cervical spine and escape detection on conventional

In spite of the shortcomings associated with the class- radiography,74,122–125 MRI,74,125–127 or computed tomogra-

ification system, Grade II WAD becomes interesting in phy (CT) scanning.125,127,128 Minor radiographic findings,

terms of Late Whiplash Syndrome, as the patients with such as loss of cervical lordosis, can be interpreted as

this condition can suffer from persistent neck pain with normal or simply a response to local muscle spasm.

muscle spasm and limited ROM that frequently charac- However, reduced cervical lordosis is a classical sign

terize chronic whiplash.52 Muscle dysfunction is sus- reflecting the early stages of disc degeneration with a

pected in many Late Whiplash Syndrome patients but potential kyphotic kink because of internal disc disrup-

remains difficult to quantify, as the use of palpation to tion (IDD) that can occur in response to a whiplash.49

assess point tenderness or muscle spasm is questionable The goal of a thorough clinical examination should

in context with poor interexaminer reliability.112 Muscle be to differentially diagnose the pain generators based

dysfunction was used to distinguish patients with chronic upon a detailed history and functional examination. The

Grade II WAD from healthy controls in a study using clinician must develop a thorough understanding of the

surface electromyogram (EMG) to assess upper trapezius whiplash event and subsequent clinical sequelae. The

muscle function.113 Patients with chronic Grade II WAD history of a patient experiencing whiplash syndrome is

demonstrated a higher coactivation level of the upper paramount to understanding the diagnosis and promot-

trapezius in the resting arm during performance of uni- ing the patient’s recovery. The history-taking process

lateral dynamic tasks, along with an inability to relax this will require an investigative approach into the mecha-

muscle to baseline levels after completion of the task. The nism of insult. Moreover, the answers should be forth-

authors interpreted this unnecessary muscle activation as coming on the chronic whiplash patient’s position at

a generalized decrease in the ability to relax the trapezius time of impact, type of impact, and the level of the

muscles. patient’s awareness at the time of the incident.

Nederhand et al. continued this research into muscle If the history is to be relevant, it must examine details

activation patterns with a similarly designed study to associated with the five clinical questions, or clinical

determine if upper trapezius EMG activity could be used “W’s” that include “Who?” “What?” “Where?”

to differentiate between patients with chronic Grade II “When?” and “Why?” The question of “Who?” refers

WAD and those with nonspecific neck pain.114 The lack to the patient’s gender, age, occupation, and coping

of any statistically significant differences led the authors style. The question “What?” identifies the primary or

to conclude that cervical muscle dysfunction is not spe- chief complaints of the patient that includes pain,

cific to whiplash trauma but appears to be a general sign sensory changes, and motor deficits. The question

in diverse chronic neck pain syndromes.114 Hence, the “Where?” addresses the location of the symptoms,

presence of palpable point tenderness or “hardness” of whereas “When?” examines the initiation and changes

muscles is of little specific diagnostic value. While the in symptoms since initial onset. The answers to these

presence of muscle tenderness and spasm is a salient questions help identify if there are any patterns of

feature in whiplash patients, an accurate diagnosis relies symptom aggravation or alleviation. Lastly and most

on the use of examination tools and methods that are important in the history of a whiplash patient, the ques-

quantifiable and contribute to the differential diagnosis tion “Why?” addresses the etiology of symptom onset

of the patient. and aggravation.

The lack of significant findings with advanced imaging The symptom presentation of chronic whiplash

with chronic whiplash suffers often leads to misdiagnosis patients can be vague in nature. Nonetheless, these

and generalized treatment. Thus, the clinician is led to symptoms warrant a clinical explanation to educate and

believe that if the injury cannot be demonstrated upon reassure the patient. The most common symptoms

imaging, perhaps there is no injury.34 Even today’s reported for WAD are neck pain and stiffness, headache,

advanced imaging lacks credible correlation with clinical and shoulder pain.21 Headaches are often the unex-

and experimental studies of whiplash injuries, which plained side effect of Late Whiplash Syndrome, while

have revealed joint capsule tears, hemarthroses, and they can occasionally serve as the primary complaint.12974 • poorbaugh et al.

The prevalence of a broad spectrum of chronic symp- test for identifying substantial injury will likely be very

toms after whiplash can serve to complicate the inter- low.134 Thus, objectifying whiplash-associated segmen-

pretation of the clinical examination. The clinician must tal instability becomes a clinical challenge.46,62

remain focused on performing a consistent battery of Clinical testing of the alar ligament and TLA liga-

tests in relation to the patient’s symptoms while main- ments has been previously described.60 However, out-

taining a respect for symptom irritability and severity. A comes from clinical testing of these ligaments may be

thorough clinical examination should include the assess- unclear. Additionally, the validity or reliability of seg-

ment of posture, ROM, cervical spine movement behav- mental testing for lower cervical instability has not been

ior, strength and sensorimotor function (Appendix A). established. Therefore, the clinician may be forced to

Each patient should be screened to determine the appro- rely on symptom presentation for identifying nonradio-

priateness for conservative management and indications graphically appreciable cervical instability. Cook et al.

for referral to a physician to rule out or confirm insta- conducted a comprehensive study to identify subjective

bility or major trauma. and objective clinical identifiers associated with this

A thorough historical account should be followed by form of clinical cervical spine instability.133 The authors

observation of posture and presence of any aberrant identified subjective symptoms that were most sug-

movement patterns during active movements. Pain gestive of nonradiographically appreciable instability,

provocation tests appear to be the most effective method where the top three were: (1) intolerance to prolonged

to evaluate back and neck pain, whereas soft-tissue static postures, (2) fatigue and inability to hold head up,

paraspinal palpatory diagnostic tests are the least reli- and (3) improvement with external support, including

able.130 Examination testing is initiated by instructing use of the hands or a collar. Similarly, the top three

the patient to perform neck motions in all cardinal objective physical examination findings suggestive of

planes to assess quantity and quality of movement. the same condition included: (1) poor coordination/

Symptom behavior is noted throughout the movements neuromuscular control, including poor recruitment and

to establish a motion limitation and/or provocation dissociation of cervical segments with movement, (2)

pattern that indicate one or more particular lesions (see abnormal joint play, and (3) motion that is not smooth

Clinical Profiles). throughout range (of motion), including segmental

Reduced ROM after whiplash injury is a prognostic hinging, pivoting, or fulcruming.

factor that may suggest a recovery delay and can be

helpful in categorizing patients when interpreted along

LATE WHIPLASH SYNDROME GENERAL

with age and gender.131 In the acute stage, whiplash

MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES

patients will often present with global limits of neck

ROM. Guarded movement and painful response in all Prevention of Whiplash Injury

planes of motion indicate the presence of muscle splint- The preventive role of the seat headrest in motor

ing and the potential for underlying articular and/or vehicles to limit rearward angular displacement of the

ligamentous lesions. However, chronic WAD produces a occupant’s head in relation to the torso during a rear-

pattern of limited motion suggesting one or more pain end collision has been investigated. A study conducted

generators (see Case Profiles). soon after the introduction of head restraints demon-

Segmental instability, or the loss of segmental move- strated that 29% of drivers without head restraints

ment control, may emerge as a consequence of Late reported neck injuries during a rear-end impact, com-

Whiplash Syndrome. While greater than 20° in single- pared with 24% of drivers with head restraints.135 The

level intervertebral rotation is a suggested criterion for lack of a clear indication for the preventive use of head

identifying abnormal cervical spinal motion,132 radio- restraints was blamed on the improper adjustment of

graphically appreciable cervical spine instability is not the head restraints. Because there is a relative time lag

present in all patients suffering with cervical segmental between the peak accelerations of the torso upon its

instability.133 While the presence of instability in motion contact with the seat back and the head upon its contact

studies acutely suggests potentially significant injury and with the head restraint,136 the distance between the head

should initiate further appropriate clinical assessment, and headrest should not exceed 10 cm.137 This differen-

there is limited evidence to support the use of flexion– tial displacement can be altered by adjusting the head

extension radiographs to “clear” the spine of injury restraint to create a more uniform contact between the

acutely following trauma because the sensitivity of the torso and the seat and between the head and headLate Whiplash Syndrome • 75

restraint.136 If adjustable headrests were placed in the work with no real emphasis on pain reduction. The

up-position, there would be a 28.3% reduction in whip- primary emphasis of the treatment regime involved

lash injury risk.138 operant conditioning with graded activity to eliminate

inappropriate pain behaviors. At a 6-month follow-up,

Prognostic indicators significant gains were observed in terms of pain inten-

The prognostic factors for a poor recovery from whip- sity, activity tolerance, and return to work. However,

lash involve pretraumatic neck pain, female gender, low more than 50% of patients did not demonstrate a clini-

education level, a WAD grade of II or III,139 work dis- cally significant change and 35% did not return to

ability, high levels of somatization, sleep difficulties,140 work. The authors suggest that deep-rooted beliefs

and high initial neck pain intensity.21,140 The Fear Avoid- about pain (avoid activity until symptoms resolved)

ance Behavior Questionnaire has been used in a study impaired healing prognosis.

evaluating the role of fear in the prognosis of recovery. The patient’s individual coping style could signifi-

Patients with neck pain were more likely to have a cantly influence treatment outcomes. Obvious patterns

chronic condition but had lower disability scores than of avoiding daily activities and nonharmful functions

low back pain patients. Disability in patients with indicate a tendency to avoid, rather than confront,

chronic neck pain was not as highly associated with pain behaviors where the patient fears could result in pain.

intensity and fear-avoidance beliefs about work activi- Proper patient education is critical to aid patients in

ties in comparison with patients with chronic lumbar overcoming these fears, as they are often based on

pain.141 The patient’s individual coping style will signifi- unsubstantiated concerns.

cantly influence treatment outcomes. Obvious patterns According to consensus-based recommendations

of avoiding daily activities and nonharmful functions from the Quebec Task Force on WAD, ROM exercises

indicate a tendency to avoid, rather than confront, should be immediately implemented.52 A number of

behaviors that the patient fears could result in pain. studies point to the importance of early activation as

a preferred treatment program for acute whiplash

Conservative Management patients.144–146 When asked about the best advice for

The primary role of intervention must be centered on acute whiplash patients, 90% of clinicians agreed that a

patient education, so as to improve the patient’s under- return to normal activity, even if it produces symptoms,

standing of the symptoms related to tissue strain and should be recommended and that exercise therapy is an

muscle spasm while stressing the high probability of effective treatment approach in these cases.106

recovery. Clinicians must stress the importance of A systematic review of randomized trials concluded

returning to normal activity for the sake of preventing that there is no beneficial evidence for use of manipula-

the development of more disabling and persistent symp- tion and/or mobilization as the sole treatment for

toms. Proper patient education is critical to aid patients mechanical neck pain.147 However, when these treat-

in overcoming their fears, as the fears are often based on ment procedures were combined with exercise, the

unsubstantiated concerns. The clinician must describe effects are beneficial for persistent mechanical neck dis-

the difference between activities that simply “hurt” and orders with or without headaches.148 A prospective ran-

those that are harmful. Detailed explanations regarding domized clinical trial evaluated an active intervention

the underlying factors that sustain the patient’s pain program involving manual therapy and gentle exercise

generator(s) and lead to symptoms could aid the patient that resulted in reduced pain intensity, less sick leave,

in recovery, where greater acceptance of pain can be and improved neck ROM. These results suggested that

associated with a significant decrease in multiple mea- an active intervention was more effective in reducing

surable domains: pain intensity, pain-related anxiety, pain intensity and sick leave, as well as in retaining/

depression, and physical and psychosocial disability.142 regaining total ROM vs. the standard intervention for

Studies of multimodal management for Late Whip- chronic whiplash patients.149

lash Syndrome offer promising outcomes for man- The careful application of manual skills to encour-

agement of persistent whiplash symptoms. Vendrig con- age restoration of physiological articular motion is a

ducted a study of 26 patients with chronic whiplash valuable treatment tool for persistent neck pain asso-

symptoms (WAD I or II).143 All patients received inter- ciated with Late Whiplash Syndrome. The clinician

vention based upon a multimodal treatment program must incorporate keen attention to the patient’s history

designed to restore normal daily activities and return to to rule out the presence of any red flags or contraindi-76 • poorbaugh et al.

cations to mobilization. This pretreatment screening Additionally, there is not a single symptom profile for

should include a thorough assessment of ligamentous whiplash patients other than the common complaint of

instability and vertebral artery insufficiency, which neck pain, making the treatment of Late Whiplash Syn-

have been previously described.60 After screening, drome troublesome. Proper treatment of Late Whiplash

manual therapy should be applied based upon the basic Syndrome requires identification of the primary pain

goals of reducing pain and/or restoring motion. The generators and development of a comprehensive, indi-

decision regarding which of these two therapy goals vidualized treatment program. The presentation associ-

should be emphasized is based upon the severity of the ated with Late Whiplash Syndrome includes neck pain

symptoms and the specificity of the clinical profile. If and stiffness, persistent headache, dizziness, upper limb

the patient presents with minor symptoms of pain paresthesia, and psychological emotional symptoms.

and stiffness, then the goal for manual therapy should These symptom characteristics can be further delineated

focus on restoration of physiological spinal motion. into subcategories that are described in the following

However, a patient complaining of severe neck pain case profiles aimed at assisting the clinician in proper

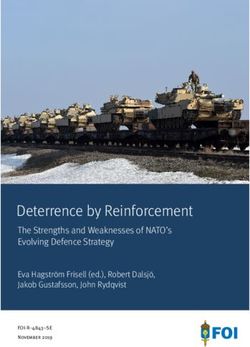

may best benefit from gentle manual techniques to diagnosis and management (Figure 1). For treating the

reduce pain and sensitivity. different types of pain generators associated with Late

Whiplash Syndrome, the clinician can reflect on the

LATE WHIPLASH SYNDROME CASE PROFILES categories that have been established for patients with

The published contentions that surround Late Whiplash neck pain. These subcategories are based on symptom

Syndrome are noteworthy, but offer few clinical solu- location, including Local Cervical Syndrome, Cervico–

tions for guiding the clinician in diagnosis or treatment. Cephalic Syndrome, and Cervico–Brachial Syndrome.150

Figure 1. Diagnosis and Treatment Algorithm of Late Whiplash Syndrome. ROM, range of motion; RFTC, radio frequency thermal

coagulation.You can also read