Labour Pride - What Our Unions A brief history of the role of working-class gays and lesbians and their unions in the struggle for legal rights in ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Labour

Pride

New Edition Prabha Khosla

What A brief history of the role

Our Unions of working-class gays and lesbians

Have Done and their unions in the struggle

for Us for legal rights in Canada2 3

There is no copyright on this publication. Prabha Khosla

However, should you decide to use material

from this publication, acknowledgment

of the source would be appreciated.

Author

Labour

Prabha Khosla

Title

Pride

Labour Pride:

What Our Unions

Have Done For Us.

New Edition

2021

Prabha Khosla is a researcher

What A brief history of the role

Paperback and activist on women’s rights

ISBN 978-1-77136-775-2 and cross-cutting inequalities in Our Unions of working-class gays and lesbians

urban governance, planning and Have Done and their unions in the struggle

E-book management. for Us for legal rights in Canada

ISBN 978-1-77136-777-6

Cover page artwork

The Great Wave, Kaushalya Bannerji

Design

Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN).

Printed in Canada by union labour.

New Edition4 5

Acronyms Contents

BCFL British Colombia Federation of Labour Introduction 8

BCGEU British Columbia Government Employees Union A tribute to all who fought

for our rights

BCTF British Columbia Teachers’ Federation

CAW Canadian Auto Workers A note 13

Communication, Energy On Indigenous lesbian, gay

CEP and two-spirit workers

and Paperworkers’ Union of Canada

CEQ Centrale de l’enseignement du Québec The 1970s 18

CETA Canadian Telecommunications Employees’ Association Links between gay

and lesbian communities, workers,

CLC Canadian Labour Congress

feminists, and trade unions

CSN Confédération des syndicats nationaux

CUPE Canadian Union of Public Employees The 1980s 31

Fighting back in the streets

CUPW Canadian Union of Postal Workers and on the job

FTQ Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec

The 1990s 47

GATE Gay Alliance Toward Equality

No goingback

HEU Hospital Employees Union

LGBT Lesbian, Gays, Bi-sexual and Trans Into the 2000s 78

Expanding rights

Lesbian, Gays, Bi-sexuals, Trans, Queer

LGBTQ2

or Questioning and Two-Spirit

Conclusion 92

NUPGE National Union of Public and General Employees Unions and Equalities

OFL Ontario Federation of Labour

References 96

OPSEU Ontario Public Sector Employees’ Union

OSSTF Ontario Secondary Schools Teachers’ Federation

PSAC Public Services Association of Canada

SFL Saskatchewan Federation of Labour

Saskatchewan Government

SGEU

and General Employees Union

USW United Steelworkers6 7

Acknowledgements

Many individuals and unions supported the new edi-

tion of Labour Pride. I would specifically like to recog-

nize the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE/

SCFP), National Office for their financial support and

thank the many members of CUPE/SCFP who assisted

with the new edition in numerous ways. Specifically,

my immense gratitude to François Bellemare, Cheryl

Colborne, Elizabeth Dandy, Shelly Gordon, Gina McKay,

Bill Pegler and Dwayne Tattrie. I especially also want to

thank Marie-Hélène Bonin, Confédération des syndicats

nationaux (CSN), for solidarity and assistance with the A special thanks and gratitude to all who agreed to be

design; Morgen Veres, Ontario Public Service Employees interviewed and their patience with the long journey of

Union (OPSEU); Adriane Paavo and Louise Scott, United this project.

Steelworkers (USW) Canadian National Office; Prof. Line

Chamberland, Research Chair on Homophobia at Uni- Financial assistance for this publication was provided

versité du Québec à Montréal (UQAM); Larry Kuehen, by CSN, CUPE National, OPSEU’s Social Justice Fund,

British Columbia Teachers Federation (BCTF); my sister, BCGEU/NUPGE and the Michael Lynch Grant in LGBTTQ

Sangeeta Khosla, for logistical support with the research Histories awarded by the Bonham Centre for Sexual Diver-

in Vancouver; Casey Oraa and Toufic El-Daher of the sity Studies at the University of Toronto. The French

CLC’s Solidarity and Pride Committee; Dai Kojima, Sexual language translation was provided by the USW Canadian

Diversity Studies, University of Toronto; and Mélissa Alig National Office. Marie-Hélène Bonin reviewed the French

for her assistance with French. Thank-you all! Without edition. Many thanks to all of them for their support for

them this publication would not be in your hands. the new edition.

The original version of Labour Pride was produced for the

World Pride Committee of the Toronto and York Region

Labour Council for World Pride 2014. The Committee for

that project included Carolyn Egan, United Steelworkers

(USW); Robert Hamsey, Ontario Public Sector Employ-

ees Union (OPSEU); Wayne Milliner, Ontario Secondary

School Teachers Federation (OSSTF); Prabha Khosla;

Stephen Seaborn, (CUPE) and Morgen Veres, (OPSEU).

Financial support for the first edition was provided by

CUPE Ontario. Research assistance was provided by

Mathieu Brûlé, Sue Carter and Tim McCaskell.10 11

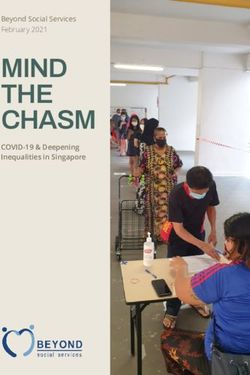

The publication honours the hundreds of gay and lesbian workers who

organized for rights and visibility – all those who came out, organized

for inclusiveness and diversity, and fought for equal rights on shop

The new edition of Labour Pride has been a few years in the making. The floors and in hospitals, libraries, hotels, schools and offices. As work-

research, interviews and connections for this publication took place in ers, activists, and staff of unions, they challenged their unions, but did

the many territories of the nations of Turtle Island. At its conclusion, I not always succeed. Many of them came out and tried to get elected to

am most grateful to be living in the unceded traditional territory of the union leadership positions but were not elected. Many tried again and

Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh and Musqueam Nations. again to raise their voices but were ridiculed and marginalized. Many

eventually quit their jobs, went elsewhere, ‘played straight’ or gave up

The history of working-class gays and lesbians in the trade union on the union movement. Many indigenous and racialized people faced

movement is as old as the early days of union organizing, when workers so much racism from workers, unions and management that coming

began to collectively demand improvements in their working conditions out was not an option. All these workers’ struggles were a passage to

and fight for better pay, rights, and benefits. This publication offers a later victories.

brief account of the role of workers and their unions in support of gay

and lesbian rights in Canada from the 1970s to the early 2000s. The

struggles and stories provide an overview of the organizing of workers

and their unions for legal rights as gay and lesbian workers in Canada. This publication primarily documents the struggles and positive changes

and victories of gay and lesbian workers and the unions that supported

them. These victories have been critical to the success of the struggle

for equal and legal rights for LGBTQ2 peoples in Canada. Without the

engagement and investment of unions in the struggle for equality, it

is doubtful we would be where we are today, even though many gains

remain to be made on several other fronts.

Many unions in Canada have contributed their strength, influence,

voice and resources in support of gay and lesbian workers. However,

“Job security for lesbians and gay men”. Toronto Pride 1977.

the engagement of unions in the struggle for lesbian and gay rights is

uneven. While some unions took up the demands of lesbian and gay

workers, others chose to not support this struggle. While some unions

have ‘caught’ up in recent years, by devoting resources and energy to

LGBTQ2 issues, others have not. Going forward it may be useful to better

understand why some answer the call and others don’t. Most certainly,

work remains to be done and all unions can and should get involved in

supporting the rights of not only LGBTQ2 workers, but the rights of all

workers including racialized workers, women workers, workers with

disabilities, indigenous workers, young workers, the organized and

unorganized and the many who have face multiple and intersecting

inequalities.12 13

The research for this publication took sev-

02

eral forms. I contacted gays and lesbians I

knew in unions and who I knew had been

activists in unions for many years. They This publication attempts to cover some of

gave me leads to other LGBTQ2 workers. the major and not so high-profile struggles

I also contacted women’s rights, LGBT for legal rights of gays and lesbians and

rights and human rights staff of various LGBTQ2 working peoples and their unions,

A note

unions. These women and men gave me from the early 1970s to the early 2000s. By

more names to follow-up. Other LGBTQ2 no means does this publication claim to be

activists identified publications, papers the definitive history of LGBTQ2 workers

and union materials about LGBT rights and unions. There are still many gaps.

for me to follow-up with. I interviewed There were many LGBTQ2 peoples who

numerous workers documenting their lives were not in unions and who also fought

On Indigenous

as union activists and leaders. I researched for legal rights in Canada. They are not a

academic books and papers and visited focus of this publication. Their lives and

archives of cities, universities and unions. contributions are covered in other essays

lesbian, gay

A lot of historical materials such as post- and books.

ers, buttons, newsletters, etc. are in the

and two-spirit

homes of activists. I was not able to access A note on the use of terms and acronyms

many of these materials. As usual, the used to refer to gays and lesbians and what

research was more extensive than what we now broadly refer to as LGBTQ2 com-

workers

you will read in these pages. munities. An attempt has been made to

keep the use of terms to their historical

periods. For example, in the early years

the language used was gays and lesbi-

ans, then it became LGBT, to LGBTQ2S

and still others today. These acronyms

are important as they signal the growing

movements for sexual orientation and

gender identity (SOGI) rights. In this pub-

lication, I have roughly attempted to keep

to the language of the historical periods.

Towards the later part of the publication

I use the term LGBTQ2. None of the terms

used or not used here are meant to exclude

anyone who considers themselves a part

of our community.14 15

There is a large gap in the literature in terms of the lives of indigenous Lori Johnson, Two-Spirit

LGBTQ2 workers who might have been part of unions, even if, due to rac- Métis woman

ism they did not have a good experience of the union or their co-workers.

Due to various constraints it was not possible to do unlimited research Lori is a nurse by profession. She was

to identify these workers. Given the history of colonialism and racism in also the Director of the Morgentaler Clinic

Canada and the barriers to employment faced by indigenous peoples, it in Winnipeg for ten years. Lori’s family

is likely that, if one were an indigenous lesbian, gay or two-spirit person descends from Métis people who were buf-

and had managed to get a job, one would not bring attention to oneself falo hunters, free traders and guides on the

by coming out. That would be asking to be fired and worse. While things plains of the Red River area of Manitoba.

have begun to change in recent years, working as indigenous workers Her ancestral Scrip is in Winnipeg in the

in union or non-union jobs has meant dealing with a lot of racism from area that is now called St. James. Accord-

management, unions and co-workers. I hope others will take up the ing to Lori, “It is difficult to find two-spirit “Bosses and co-workers could be overtly

challenge to document their stories. peoples who were in unions in the time racist. They would openly say things like,

horizon of your research because we often ‘We don’t hire Indians here, one paycheck

Albert McLeod, Co-director of the Two-Spirited People of Manitoba would not apply for those jobs as we knew and you’ll never see them again’. In my

Inc. and a human rights activist for the past thirty years feels that two- we would not get them. Mostly what we family my uncles used to work up north

spirit peoples have likely been in jobs which were unionized but were got were low-paying jobs with no security in the construction of dams, (the flood-

probably not out. and no protections. Métis peoples were way in Manitoba), and they were skilled

often under-represented in good paying tradesmen such as plumbers, pipe fitters,

jobs with benefits, especially two-spirit and welders etc., but they would never let

Métis people”. anyone on the job know they were Métis.

We only spoke about ourselves as Métis

within our families for fear that if employ-

Albert McLeod says, ers found out that you were Métis, you

would never get the job. My male family

“… in the intersection of the three spaces of indigenous, unions, members were never in a union, they were

and two-spirit there must have been some history about such only hired as labourers. My mum and all

engagements; but we lose history and there is still a lot of her sisters worked all their lives, but none

stigma. It was difficult to be out in those years and especially of them were ever in a union. They did

in ultra-masculine jobs. There must be history there as many traditional women’s work of that time –

administration, secretarial work, etc. Even

two-spirit peoples had/have non-indigenous partners who

though they were heterosexual, they were

were also involved in unions. Previous research on workplace not open about being Métis. The reality of

issues and 2SLGBT+ peoples probably was not looking at racism in the workplace was enough of

indigenous peoples as workers.” a barrier to Métis people accessing good

jobs, never mind adding the matter of

Additionally, Albert says, homophobia”.

“You must remember that in recent decades indigenous peo-

ples were never employed at the same rates as other people.”16 17

Pride March. twospiritmanitoba.ca

Two-Spirit People of Manitoba

Lori says that Métis people often faced Origins of the term

somewhat less overt racism in the work- Two-Spirit or Two-Spirited

place than for example, First Nations

people. Employers were often reluctant While the term two-spirit has been

to hire people who could be more visibly A recent publication, Indigenous Workers, widely adopted across Canada, many are

identified as indigenous. Being two-spirit Wage Labour and Trade Unions: The His- not aware of its origin. Albert McLeod

was an additional barrier. torical Experience in Canada (Fernandez. (2003) traces this history, “A number of

L & Silver, J. 2017.), while not addressing papers by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal

She feels that this reality is a lot better 2SLGBT+ workers, provides a great over- authors have identified that the term was

for Métis people today. With rates of view of the engagement of indigenous introduced into the Aboriginal gay and

higher education, training and affirma- women and men in wage labour and lesbian community in Winnipeg, Mani-

tive action programs, it is her experience with unions. Using examples from differ- toba, in 1990, at one of a series of annual

that there are many more indigenous two- ent parts of Canada it demonstrates their international (primarily Canada and the

spirit people who do hold good-paying extensive engagement as waged labour- United States) gatherings (Medicine, 2002 The Manitoba gathering was held in

jobs.“Racism and homophobia remain a ers in the early centuries of colonization as quoted in McLeod, 2003.). The third August and in the fall edition of Two

reality in society but progress in awareness and the exploitation of different natural gathering in 1990 was sponsored by the Eagles, there were five letters from people

and education about diversity are having resources in different part of the country. Nichiwakan (friend) Native Gay and Les- who had attended. Three of them refer to

a positive effect for us as indigenous two- Their engagement in the waged economy bian Society in Winnipeg. The term Two- “Two-Spirit(ed) womyn, mothers, daugh-

spirit people”. Lori wants it to be clear, is also impacted by the vast distances Spirit was coined as an alternative at this ters, person, people, and brothers”. In

that she cannot speak to the experience they travelled to get waged work and their Conference. At the time some Aboriginal the earlier summer edition of Two Eagles

of First Nations people in the unionized subsistence livelihood activities in their people had alliances with the gay commu- and in other writings prior to the ‘90

workplace. different communities. The publication nity and strongly identified as gay, lesbian gathering there is no record of the term

documents how, with increasing white or bisexual. In the Two Eagles newsletter, “Two-spirit”. In 1991 the organization in

colonial settlements, racism from com- of June 1990, several organizations were Toronto changed its name to “2-Spirited

panies, settlers and workers themselves listed: Gay American Indians, San Fran- People of the 1st Nations”. Some authors

became a convenient strategy to take cisco; American Indian Gays and Lesbians, have their own opinions as to why this

away the waged livelihoods of indigenous Minneapolis; WeWah and BarcheAmpe, change occurred (Hasten, 2002 as quoted

workers. The popular strategy of divide New York; Nichiwakan Native Gay and in McLeod, 2003).

and rule was used effectively by coloniz- Lesbian Society, Winnipeg; and Gays and

ers and employers in creating divisions Lesbians of the First Nations, Toronto. Albert also cautions us that, “Although

between workers of different racial and two-spirit is an umbrella term meant to

ethnic groups and indigenous workers. be inclusive of all indigenous peoples, it

For example, the precarious situation of should be noted that Inuit gays and les-

Chinese workers in British Columbia was bians have not yet been consulted as to

used to push indigenous workers out of whether they wish to be identified with

jobs and keep wages low. it (2003, 28).”20 21

Article published in The Body Politic, 1976. archive.org

The 1960s was a period that saw a tremen-

dous growth in movements challenging

the status quo. These included the wom- They ensured that their demands such

en’s movement, the anti-war movement, as childcare, maternity leave, equal pay,

the civil rights movement, and the Amer- an end to separate seniority lists, pay

ican Indian Movement. It was also a time equity, employment equity and issues of

when women entered the paid labour force workplace sexual harassment and socie-

in great numbers. Women’s engagement in tal violence against women, became core

the paid labour force in such large num- union demands for equity and equality for

bers brought significant challenges and women workers. These demands evolved

changes to workplaces, to unions and to into mainstream union demands over

society at large. the following decades. The structures

and mechanisms that women set up in

There is a broad consensus in the labour unions became the models that were sub-

movement and among labour and fem- sequently reproduced by other workers

inist researchers that it was feminists such as gay and lesbian workers, racial-

in the trade union movement who first ized workers, workers with disabilities

challenged patriarchal union orthodoxies. and Aboriginal workers.

These women workers pointed out that

while unions could be a vehicle for change, In the early 1970s, there was a significant

too often the unions themselves became overlap between those involved in gay and

an obstacle to women’s equality - and thus lesbian organizing and those involved in

equality for all workers. left political parties and the independent

left. According to Ken Popert, a founding

Union sisters with support from feminists member of Gay Alliance Toward Equality

outside the trade union movement created (GATE), Toronto and The Body Politic (1971-

women’s committees and caucuses and 1987), (a gay monthly magazine which

developed and led educational and train- played a major role in the struggles of gays

ing programmes on women’s rights and and lesbians in Canada), GATE had many

leadership. They fought for their represen- members who were active in the gay liber-

tation in leadership and decision-making ation movement and were also members of

structures at all levels of their unions. trade unions. He says gay activists learned

to organize from trade unionists and from

left wing parties.1

1 Furthermore, Popert shares a little-known fact - two gay

men paid for the printing of the first issue of The Body

Politic. They were both union members and one of them

was with the Printers’ Union.22 23

An early example of gay and lesbian activists connecting with

unions was the 1973 struggle to get sexual orientation included in On September 28th, 1976, Local 881 of

an anti-discrimination policy at the City of Toronto. Members of the Canadian Union of Public Employ-

GATE had first approached City Council to get their support, but ees (CUPE) passed a resolution that was

city councillors did not support the resolution. This prompted In 1975 the University of Regina Students’ probably a landmark resolution for gay

GATE members to solicit support from the city’s unions – CUPE Union and the Canadian Union of Public workers in British Columbia. The reso-

Local 79, the inside workers and CUPE Local 43 representing Employees, (CUPE) Local 1486 signed the lution which was sent to the B.C. Feder-

the outside workers. first labour agreement in Saskatchewan ation of Labour convention in November

prohibiting discrimination on the grounds of that year, recommended that the B.C.

of sexual orientation. The second contract Federation of Labour work towards the

with this provision was signed between inclusion of an equal opportunity clause

the Saskatchewan Human Rights Com- for gay workers in all contracts ratified for

mission (SHRC) and CUPE Local 1871 on the following year. Local 881 included the

Ken Popert recalls being impressed by the union execu- August 1, 1976. greatest number of social service workers

tive’s empathy with the oppression of gays: “The workers in the Vancouver Resources Board.4 How-

and the women on the executive, like gay men, knew ever, the resolution was not adopted at

the convention.5

what it meant to be engaged in a ceaseless struggle

against powerful and antagonistic forces. Like gays they

were constantly being shat on by the powers that control

the media and most other institutions.”2 Within a week

Oct. 1976. City of Vancouver archives.

“News Items”. SEARCH Newsletter,

of the meeting between members of GATE and the Exec-

utive of Local 79, GATE received a letter of commitment

and solidarity from the union. It said, “We thoroughly

understand your attempt to correct discrimination based

on sexual orientation. As a union we feel that if someone

is qualified for a position, he/she should be judged on

merit only. We feel civil servants are to be in no way dis-

criminated against with regards to hiring, assignments,

promotions or dismissals on the basis of sexual orienta-

tion…You have our support.”3 This was a radical position

taken by a union at a time when gays and lesbians could

be fired for being homosexuals.

4 For information about the Vancouver Resources Board,

2 Popert, K. (1976). “Gay rights in the unions”, The Body Politic, April. Toronto. p. 12-13. please see https://www.memorybc.ca/

3 Ibid. vancouver-resources-board

5 SEARCH Newsletter, October 1976.p.2.24 25

In another demonstration of some of the

historic links between gays and lesbians

organizing in the “streets” and those orga- Efforts toward formal legal equality were

nizing in the workplaces, on December 17th also underway in other provinces and in

of the same year, members of Vancouver 1977 Quebec became the first province

Gay Alliance Toward Equality (GATE) and to amend its legislation to include pro-

a member of the Canadian Union of Postal hibition of discrimination based on sex-

Workers (CUPW) made a presentation on ual orientation. However, according to

gay rights to the officers of the B.C. Fed- Around the same time, Harold Desma- Chamberland et al8 the Quebec Charter

eration of Labour. They called upon the rais, an out, autoworker at Ford’s Windsor of Human Rights and Freedoms did not

Federation to include sexual orientation in Engine Plant, was subject to tremendous protect against discrimination on the basis

anti-discrimination clauses of trade union taunting and harassment from several of of sexual orientation in matters on pension

contracts, to publicly support the inclusion his co-workers. Luckily for Desmarais, plans, insurance and benefits (Article 137),

of sexual orientation in the B.C. Human the United Auto Workers union (later the even though protection against discrimi-

Rights Code and to set up a committee on Canadian Auto Workers, and now Unifor) nation on the basis of sexual orientation

gay rights within the B.C. Fed.6 had a clause in its contract prohibiting was adopted in 1977. Further, according to At this time, there was no Canadian Char-

discrimination based on sexual orienta- them, “In the years 1976-1977 the unions ter of Rights and Freedoms and none of

tion – a rarity at the time. “Back then, it offered their support to lesbian and gay the other provinces or territories included

was sort of a catch-22 situation,” he said. activists against police repression; how- sexual orientation as a prohibited ground

“People would say ‘if there’s nothing to be ever, this was more a formal show of sup- for discrimination.

ashamed about, why are you hiding your port than direct action or support”.9

sexuality,’ but a lot of people couldn’t be

open about their sexuality without putting

“Gay Rights for Gay Workers”.

their job and even their home at risk”7.

Harold was also an active member of

Windsor Gay Unity.

8 Chamberland, L., Lévy, J. J., Kamgain, O., Parvaresh, P. &

Bègue, M. (2018). L’accès à l’égalité des personnes LGBT.

In F. Saillant & E. Lamoureux (Eds.), InterReconnaissance:

La mémoire des droits dans le milieu communautaire au

7 http://www.insidetoronto.com/news-story/4059688-hu- Québec (pp. 49-112). Canada: Les Presses de l’Université

man-rights-advocate-harold-desmarais-to-be-inducted- Laval.

6 Gay Tide, February 1977, p.3. into-q-hall-of-fame/ Accessed July 18, 2019. 9 Ibid. p.7426 27

Organizing a gay

bathhouse in Toronto

In 1976 David Foreman, then On February 23rd, 1977, Don Hann, a gay day care worker in Vancouver

in his mid-thirties, moved to lobbied the Daycare Workers Union of B.C. to form a gay caucus. One

Toronto and joined the Univer- 40+ rooms, cubicles, and wash- of his arguments to his colleagues was that unions were finally recog-

nizing gay and lesbian workers and supporting them and urged uniting

sity of Toronto’s Communist Party rooms. David came close to

with gay caucuses of other trade unions. Furthermore, he stated, “Only

Club, the Gay Alliance Towards signing up fifty percent of the by coming out of the closet, demanding our civil rights, soliciting the

Equality (GATE) and worked workforce, “…but I noticed that support of sister and brother trade unionists and others will we ever

evening shifts at the Richmond the boss was also organizing win our liberation”.10 Don’s resolution was adopted by the meeting.

Street Health Emporium - a gay against me. He organized a lot

steam bathhouse cleaning rooms. of dope parties for the workers In January 1979 the Saskatoon and District Labour Council passed a

resolution calling for the province’s human rights legislation to be

According to David, “There were and I thought to myself that I can-

amended to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.

special perks there like you could not compete against this special

have sex sometimes and you entertainment”. Soon David was Slowly but surely, the B.C. Federation of Labour came around to acknowl-

could stay over and not have to let go from the steam bath. edging sexual orientation in its rank and file, i.e., the existence of gay

pay. But there was a little group and lesbian workers. See the letter in this page.

of privileged people there who The union filed an unfair dis-

were getting special treatment by missal complaint at the Labour

BCFL letter. October 23, 1979. City of Vancouver archives.

the management and I thought Relations Board. On the day of

that was not fair to the others. the hearing the owner of the Bath

So, I decided to look for a union proposed a $1,000 settlement for

that might help me organize the firing David. David told the union

steam baths”. that he did not want to accept the

offer as that would be a defeat.

David approached the Hotel Eventually, David accepted the

Employees and Restaurant $1,000, after the union lawyer

Employees International (HERE), said that most likely someone

a precursor of UNITE HERE. else would build on his work and

According to David, “The union be successful. However, she did

was hesitant at first because they not tell him that the settlement

had never heard of what goes on came with a ban from the Toronto

in steam baths. But they said go bath houses. The following week,

ahead and see how many names David tried to go to a bath house

you can get”. At the Bath, there but was not allowed in and the

were 20-30 people working in the same happened at another bath.

three shifts and it had about The ban lasted almost 30 years.

10 This information is from historical documents given

to the author by Don Hann.28 29

Many lesbians were also not hiding who

they were. The following case about the USW 2900 became a forward looking and

women workers of Inglis shows that les- militant Local and the union activists did

bians were active in their unions and in what they could to create an atmosphere

leadership positions in unions of predom- There was homophobia in the plant like in on the shop floor where sexuality wasn’t

inantly male workers. every workplace but courageous women an issue. Interestingly, the guy who gay

like Bev stood up to it and gained the baited Bev during her election later ran as

Solidarity on respect of their fellow workers. It wasn’t a steward on her team, proving that atti-

the Shop Floor always easy but the progressive union tudes can change as people work together.

executive, led by President Mike Hersh,

In the 1960s and 1970s women were joining It was hard work, but it was well paid. took on any harassment or bullying that It is women like Bev who not only changed

the workforce in large numbers in both Of the women who were hired or stayed went on in the workplace. The Local went union culture, but also paved the way for

the public and private sectors in Canada. on after the war, a number were lesbi- through several strikes at Inglis during the others who came later.1112

One such workplace was the John Inglis ans though it was not always spoken of eighties, building a strong camaraderie

Company, located on Strachan Avenue in openly. Bev Brown started work at Inglis in and sense of solidarity among workers.

Kitchener and Waterloo demonstrators. Toronto Pride 1975.

Toronto. The 1200 Inglis workers, members 1976. She became active in the union and Bev and another lesbian steward, Nancy

of United Steelworkers Local 2900, man- became known as someone who would Farmer, formed the first women’s com-

ufactured washing machines and other stand up for her fellow workers, particu- mittee in the United Steelworkers in Can-

appliances. During WWII the company larly women. ada. They had each other’s backs, and

had produced weapons, employing mainly Bev eventually became vice-president of

women workers known as the Bren Gun In 1979 she ran for chief shop steward. One the Local. It was rare for women in indus-

Girls, similar to Rosie the Riveter in the US. night, during the union election, workers trial workplaces to win seats on a union

After the war, most of the women were let were gathered at a local bar in advance of executive, and Bev’s was undoubtedly

go and men again became the majority. a membership meeting. The guy who was the highest position held by a lesbian at

running against Bev came up to a steward, that time. She was poised to take over the

Dave Parker, and asked for his support. presidency when the plant shut down in

Dave indicated he was voting for Bev. December of 1989.

He leaned over saying, “You know she’s

queer”. Dave shot back, “Not as queer as

this conversation. I’m voting for Bev”. He

never told her because he didn’t want to

demoralize her or hurt her, but he told

fellow workers what was going on and

Bev won the election handily – as well

as every position she stood for after that.

11 Allison Dubarry, an out racialized lesbian, was president

of USW Local 1998, the largest Steelworkers’ Local in

Canada, for three terms from 2003-2012.

12 This information provided by Carolyn Egan President

of the Steelworkers Toronto Area Council and a founding

member of Steel Pride.30 31

04

The 1980s

Fighting back

in the streets

and on the job32 33

On February 20 , 1981, a demonstration was held against

th

the police raids. Over four thousand angry people rallied at

Queen’s Park, the provincial legislature, and marched to Metro

Toronto Police’s 52 Division to protest the bath house raids

and to call for an independent inquiry. Keynote speakers at

The 1980s was an important decade in the fight for gay

the Rally included Lemona Johnson, wife of Albert Johnson, a

and lesbian rights. Gays and lesbians were openly and

proudly organizing in groups and in movements for social black man who was killed by police, Brent Hawkes, a pastor of

change in numerous cities of the country. the Metropolitan Community Church and Wally Majeski, the

President of Metro Toronto Labour Council. While Majeski took

In Toronto, the fight back decade began on February 5th, the position to support the rights of gay men against police

1981 with a massive police raid on four gay bath houses. harassment and arrests, many in the labour movement were

Two hundred and sixty-eight men were arrested and

not happy with his stand. However, his decision to speak out

charged as “found-ins” and nineteen others were charged

as “keepers of a common bawdy house”. Code named in support of gay men was an important statement of solidarity

Operation Soap, the bath house raid was the largest mass for gay and lesbian workers and underlined the need to work

arrest in Canada since the FLQ (Front de libération du in coalitions to defend the human rights of all workers.

Québec) crisis of 1970.

Labour Council at demo against police

raids on bath houses. Toronto 1981.

Demo against police raids on bath houses. Toronto 1981.

The attack on the Baths brought many “out of the closets,

(or baths for that matter) and into the streets” and raised the

volume on the need for human rights protection for gays and

lesbians. The massive organizing on the streets encouraged

gays and lesbians to also stand up for their rights in the work-

place and vice versa. Over the coming two decades there was

a dynamic and mutually supportive relationship between

organizing for LGBT rights in unions and in society at large.34 35

The 1980s was also the decade that saw the emergence of HIV and AIDS in gay

communities (and in heterosexual communities) and the tragic loss of so many

friends and colleagues. The loss of so many members of “the family”, the lack

of recognition, and inadequate and often offensive responses by governments

and medical and related institutions to the challenges of HIV/AIDS, pushed

gays and lesbians to organize “in your face” activities and challenges to the

status quo. Some unions too rose to challenge homophobia, others continued

to discriminate against their gay and lesbian brothers and sisters.

Another union actively advocating on behalf of their lesbian

Coming Out Twice and gay members during this decade was the Ontario Secondary

School Teachers’ Federation (OSSTF). Their handbook on salary

In 1983, Jim Kane was working As a result of quitting his job, policy from the 1980s stated, “… any discrimination in salary,

at CN (Canadian National Rail- Jim resigned his position on the promotion, tenure, fringe benefits based on age, sex or sexual

way) in Winnipeg. He was also orientation, marital status, race, religion, or place of national

Executive of the Union. Later, CN

origin should be opposed”. This policy was an amazing show

an active member of the union – hired him back to take a man- of solidarity from a union of teachers whose gay and lesbian

CBRT&GW (The Canadian Broth- agement position. They also told members were especially vulnerable to homophobic attacks

erhood of Railway Transport him that for them his “lifestyle” due to their work with young people.

and General Workers.) and the was not an issue. Over the years,

union’s recording secretary. This Jim worked in various positions The 1980s was the decade that pushed the struggle for gay lib-

was also the year that Jim decided eration toward the struggle for equality and human rights rec-

including human resources and

ognition. However, activists also lost many challenges for equal

to come out to his co-workers, the labour relations to change pol- rights and unions did not always support them.

union and to CN. icies and at various points the

managers asked for his inputs as

In the Fall of 1983, Jim ran for

they developed policies for inclu-

President of his Local. He lost the

siveness. When Jim was diag-

vote because some members did

nosed as HIV+ he was involved

not want to vote for him because

in developing policy for people

he was gay. Jim was so upset by

who were positive. He came out

this homophobic behaviour that

as HIV + on December 1st, 2000

he quit the union and left his job.

but was diagnosed in 1986. Jim

At this time, CN was very much

feels he came out twice.

a blue-collar male dominated

industry and women were only

just beginning to come into the

CN workforce.36 37

Eric wanted his job back; but the Nova Sco-

Fighting prejudice tia Teachers Union never really attempted

in education to get Eric reinstated. Instead, the union

wanted $200,000 in compensation for

In 1987, Eric Smith was teaching grades Eric from the School Board. However, the

five and six at Clark’s Harbour Elementary School Board did not have the money, so

School (pop. 1,200) on the south shore of Eric did not get any compensation.

Nova Scotia. Ever since he was young, As gays and lesbians were organizing

Eric Smith, 1989. Halifax Rainbow Encyclopedia.

many in the community presumed he was Eric continued to live in the community and fighting for their rights on numerous

gay. Eric was also active in the teachers’ still hoping to get his job back. However, fronts, the Canadian Charter of Rights and

union and the year before; he was presi- the police were concerned about Eric’s Freedoms, a watershed document enshrin-

dent of the union local. safety and felt they could not guarantee ing the rights of Canadians, became part

it. It was around this time that the Prov- of the Canadian Constitution in 1982. How-

In 1986 Eric was diagnosed with HIV and ince approached the Union to see if Eric ever, its equality rights provisions did not

‘outed’ by his doctor’s secretary the follow- would be willing to join the Nova Scotia become legally binding until 1985. The pro-

ing year. In this small fishing community, it Task Force on AIDS. He agreed and was hibition of discrimination on the basis of

did not take long before parents suspected seconded to the Task Force on his teacher’s sexual orientation was incorporated into

he was the person who was HIV+ as they salary. He worked there for a year. The idea the Québec Charter of Human Rights and

had always assumed, he was gay. Despite a was that after a year he would go back Freedoms as early as 1977. Sexual orien-

gross violation of his privacy, Eric decided to the school; but the parents organized tation was included in the Human Rights

not to take any legal action against the against him once again. Code of Ontario in 1986 and in the codes

doctor or his secretary. of Manitoba and the Yukon in 1987. The

The Provincial government intervened inclusion of sexual orientation as a pro-

When Eric’s HIV status became public, again and offered Eric a position for three hibited ground of discrimination was not

a meeting was called, and 500 people years with the Dept. of Education in Hal- covered in the Canadian Charter, Section

attended. At the meeting, a southern U.S. ifax to develop an AIDS curriculum for 15, until 1995, with the Supreme Court of

Baptist Church film was shown which No meetings were held by health depart- high schools. In 1991, after the three years Canada decision in the case of Egan vs.

depicted a student using the same comb ment staff to assure the public that Eric, were completed, Eric was still not able to Canada. In May 1995 the Supreme Court

as someone who had AIDS, implying that as a teacher who was HIV+, was not a dan- resume his job. Finally, Eric settled with ruled against Jim Egan and Jack Nesbit,

if any of the students in Eric’s class were to ger to the children. The kids on the other the government. His demands were that two gay men who sued Ottawa for the

use his comb, they would get AIDS. hand were supportive of Eric and they were there should be AIDS education in schools right to claim spousal pensions under the

excited to be in his class. He dressed casu- and that sexual orientation and rights of Old Age Security Act. Despite the ruling

ally, was friendly and accommodating and peoples with HIV and AIDS be included against them, all nine judges agreed that

a fun teacher who did things like play disco in the Human Rights Act. In exchange for sexual orientation is a protected ground

music for the students while they worked. this, Eric agreed to give up fighting for his and that protection extends to partner-

Despite his popularity with the students, teaching job. The Union did not support ships of lesbians and gay men.13

Eric lost his job. Eric to get his job back and neither did

they apologize.

In December 2018, Eric Smith was awarded

the Nova Scotia Human Rights Award.

13 http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/timeline-same-sex-

rights-in-canada-1.1147516 Accessed July 18, 2019.38 39

Legislation and collective

bargaining work in tandem

Unions negotiate new provisions for collective

agreements that eventually become enshrined in

law, and laws become integrated into the reading

of collective agreements. Gay and lesbian workers The first arbitration case for same-sex ben-

first organized for their rights in their locals and efits was filed by a worker of the Cana-

at the bargaining table, winning new rights in dian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) in

their collective agreements. Once same-sex rights, Quebec in 1986. She was a lesbian who

protections and benefits began to be included was denied leave to care for her ailing

in collective agreements, grievance procedures same-sex partner of 16 years. The col-

provided a mechanism to challenge discrimina- lective agreement allowed employees

tion against gays and lesbians. If a case was not leave in situations of illness if they were

resolved at the workplace; it went to arbitration “immediate family members” and even

at a Labour Relations Board. if they were “common-law spouses”. The

CUPW argued that the definitions were

applicable to the lesbian and her same-sex

partner and that they should be covered In 1988 Karen Andrews an employee of the

“For Lesbians Rights”. Montreal demo 1984. Jean-Marie Vézina, CSN.

especially since their collective agreement Toronto Public Library Board claimed that

prohibited discrimination based on sexual she and her live-in female partner, and

orientation. However, Canada Post refused her two children were entitled to family

to recognize her partner as either family coverage under the Ontario Health Insur-

or a common-law spouse (Peterson, 1999, ance Plan (OHIP). The Canadian Union

p.40-41) Needless to say, the CUPW worker of Public Employees, (CUPE) Local 1996

did not get the leave. supported her case. However, the Ministry

of Health refused to accept the application

for family coverage. The Ministry’s lawyer

argued that the definition of a family in the

relevant legislation restricted it to spouses

of the opposite sex. While Andrews did

not win her case, her challenge eventually

led OHIP to make changes by enabling

individualized coverage.40 41

Rights were won through pain and humiliation.

Below, Darlene Bown explains what happened

to her when she tried to get same-sex benefits for

her partner.

On September 13th, 1988, Darlene Bown was hired to work in Word spread like wildfire throughout the hospital that I was

food services in a hospital in Victoria, B.C. a lesbian. I was a shop steward and on the local executive

and I won the member of the year award that year. Once the

“I was out as a lesbian in my personal life but not at work as it word got out that I was a lesbian, a co-worker went to another

was not safe. My partner decided to go back to university, so I shop steward and accused me of sexually harassing her. The

applied to have my partner put onto my benefits. At this time, I accusation was never investigated, and I was removed from

was working in housekeeping. My manager was supportive, so my position as a shop steward and from the local executive.

I went to human resources to file the paperwork. When I told I was called ‘dyke’ in the halls by trades people and received

HR my partner’s name I was questioned if my partner’s name threatening phone calls at home. My coming out was not sup-

was wrong as it looked and sounded like a women’s name, I ported by my union or my co-workers. By now it was 1993 and

said she is a woman. When I left that office, I heard laugh- I was working in Central Processing Services where operating

ter breakout from the office that I had just left. I will always room instruments are sterilized. Thankfully, the Hospital

remember how it made me feel. It was my worst nightmare; Employees Union (HEU) Provincial Office did not support the

I was being discriminated against right to my face. Everyone Local’s decision to remove me from the Executive.

was laughing at me. I cried the rest of the day. I wanted to

quit my job right there and never go back. I booked off sick In that same year, HEU held a focus group for LGBT people

and only with the support of my partner did I return to work. at the summer school training. This essentially forced many

people to come out as that was the only way you could be in

My manager had his clerk process my paperwork which had the focus group. I had a woman walk up to me and tell me

my women partner’s name on it. That was back in the summer her name was Louise. She said, ‘I am a lesbian and you are

of 1992. a lesbian too’. I was shocked when she said that, but I said

‘yes’. Since then I have never looked back. I have been with

HEU from the start of its inclusion of LGBT people and even

today I am active in the union. Thanks for HEU learning and

growing with me”.42 43

The 1980s also saw several unions explicitly denounce dis-

crimination on the basis of sexual orientation. For example,

in 1980, the Canadian Labour Congress amended its constitu-

tion to include sexual orientation. In 1985, the Canadian Auto

Workers (CAW) broke away from the United Auto Workers and

formed their own union. The first CAW constitution contained

“Lesbians and Gays are Coming

Out”. Nouvelles CSN, 311, 1989.

Article 2 – Objectives: “To unite all workers who are under the

jurisdiction of CAW Canada into one organization without regard

to …sexual preference…” This reference had not been included

in the UAW Constitution. In 1994, the language was changed to

“sexual orientation”.

Quebec lesbian

and gay workers

This was also the case in Quebec. The CSN has an early history Members of the committee set themselves the following

of the self-organization of gay and lesbian workers. In June objectives: “1) conduct an inquiry into the reality of mem-

1988, at the National Congress, a gay man called for an informal bers; 2) collect testimonies; 3) integrate into the network

meeting of lesbian and gay workers. A handful of workers met of lesbian and gay organizations in order to be visible; 4)

and proposed the creation of the Comité CSN sur la condition des develop a network of activists that reaches out as much

lesbiennes et des gais. It was not part of any official structure as possible to the various regions of Quebec; 5) develop

but more of a working group. A formal Committee with an offi- various demands in order to improve the situation of les-

cial mandate from the CSN’s Conseil confédéral was created in bians and gay men in Quebec”. The Committee adopted

March 2-4, 1989. Its mandate was, “…inquire into the realities the pink triangle as its logo.14 The Committee, the Comité

of the members of these minorities in our movement and in the confédéral LGBT, became a permanent advisory body to

workplaces and propose counter-measures aimed at eliminating the confederation.

all forms of discrimination by members of these minorities”.

14 NOUVELLES CSN 311 1990-09-20 page 14.

Accessed July 24th, 201944 45

“I was one of three or four LGBT staff who formed a com- The fight against

mittee within the CUPE Local to promote LGBT issues crosscutting inequalities

within CUSO [CUSO is a Canadian organization that The struggle for equality rights of workers

recruits Canadians to work in the global South on a vol- in workplaces and in unions in the 1980s

unteer basis.]. From about 1982ish to about 1987ish we also involved organizing for the rights of

were able to achieve the insertion of non-discrimination women and racialized workers - this ben-

based on sexual orientation into our collective agree- efited gay and lesbian workers generally

and specifically those gays and lesbians According to Beverley, “It is important

ment and within the process of selection, preparation

who were also racialized and thus expe- to mention that there was not a lot of

and placement of Canadians going to work in the global rienced multiple and intersecting discrim- support in the labour movement for this

South. As a result, a section on sexual orientation was inations. In the 1980s, the Ontario Public work. Some union leaders supported it,

included in pre-departure discussions and a document Service Employees Union (OPSEU) began but many of the rest reflected the conser-

was written on conditions relating to sexual orientation a conversation on employment equity in vatism of Canadian society in terms of

in various programming countries of CUSO. Several the province and established a Race Rela- equality for racialized or gay and lesbian

tions and Minority Rights Committee in the workers or the rights of workers with

openly LGBT persons and couples were recruited and

union. The committee included workers disabilities. They were not supportive of

placed by CUSO. Lily Mah-Sen, then a CUPE member who represented the interests of women, employment equity. On the other hand,

and now of Amnesty International was instrumental in who were racialized, who were workers this work also attracted a lot of workers

this. We also did conscientization within the Union and with disabilities, who were Francophone who had faced discrimination or multi-

within CUSO. This set an important precedent among and who were gay. These committee mem- ple and intersecting discriminations and

many for CUPE and its locals.” bers came from different sectors within many more of these workers became active

OPSEU: colleges, public sector, etc. and in the Union”.15

Trevor Cook, Montreal came from both urban and rural areas of

the province. At that time Beverley John- The work of Beverley and her colleagues

son was a member of the Committee. She from OPSEU and community-based orga-

eventually became the Chair. nizations influenced the New Democratic

Party (NDP) and a few years later the

Ontario NDP introduced an Employment

Equity Bill which eventually became law.

15 Interview with the author on June 27th, 2014.46 47

05

The 1990s

No going

back48 49

In the 1990s, unions and labour federations built on the In 1991 six CAW members, with the assis-

victories won through grievances in individual unions. tance of the union, filed human rights

This was the decade that saw grievances move from complaints against Canadian Airlines for

Labour Board arbitrations to Human Rights Tribunals, its refusal to recognize same-sex spouses

to provincial courts, to the Supreme Court of Canada. As for benefit coverage. A year later a similar

the agenda for equality and social unionism advanced, complaint was brought against Air Can-

there was no going back. Throughout the 1990s, the ada. Gay men were a significant part of

workplace rights of minority workers advanced through the workforce in the airline sector.

contract negotiations winning human rights and equality

language, same-sex benefits and eventually pensions.

In 1991, the gay and lesbian committee of

Cover of CUPE Pink Triangle’s first publication, 1992.

In 1989 the Hospital Employees Union (HEU) in British CUPE, the National Pink Triangle Commit-

Columbia had negotiated same-sex benefits, well before tee, was formed. In 1992, they were the first

it was legally mandated in the province. Then, in a land- labour committee in Canada and possibly

mark decision in 1991, the union filed an historic human internationally, to prepare an information

rights lawsuit on behalf of HEU member Tim Knodel kit on sexual orientation.

against B.C.’s Medical Services Commission (MSC) when

it denied medical coverage for Knodel’s partner Ray Gar- In the fall of 1992, two gay men, Michael

neau, who was terminally ill. On August 31, 1991, the B.C. Lee and Rick Waller, members of CTEA

Supreme Court ruled in favour of HEU and ordered the (Canadian Telephone Employees Associa-

MSC to recognize same-sex partners as “spouses” and tion) filed separate grievances with Bell for

grant them medical coverage. same sex-benefits. It took until November

1994 before a judgement was delivered by

the arbitrator in their favour and led to the

same-sex benefits coverage for all the gay

and lesbian employees and managers of

In 1990, a group of union members founded the PSAC Bell. Unfortunately, Waller did not survive

Lesbian and Gay Support Group (LGSG), which lobbied to hear of their victory. He died of compli-

strongly for the rights of lesbian and gay members. Also, cations from AIDS a few months before

in 1990, the first CAW Lesbian and Gay caucuses were the decision was announced. This was a

formed in Toronto and Vancouver. A major focus of their victory for same-sex benefits in Canada

work was to tackle the issue of same-sex benefits. In 1990, before same-sex benefits were won for

the CLC Convention adopted a resolution to make same- LGBT workers in many other parts of the

sex benefit bargaining a priority for all Canadian unions. country, and it enabled LGBT workers in

other unions of Bell to also benefit from

this victory.50 51

Station 25. Montreal, 1990. André Querry.

Kiss-in to protest police violence at Police

Equity work in the 1990s included the for-

mation of several identity-based caucuses

within OPSEU and in many other unions

across Canada. The OPSEU caucuses

included Workers of Colour, Aboriginal The 1993 Quebec Human

Circle, Disability Rights and a gay and Rights Commission

lesbian caucus that eventually became Inquiry into violence

the Rainbow Alliance of today. The point and discrimination against

of the caucuses was to enable as wide a gays and lesbians

representation and engagement from the

members of OPSEU as possible. In 1992, following the killings of nine gay

men over two years in Montréal, the Table

As Bev Johnson says, “Of course, as the de concertation des lesbiennes et gais du

caucuses became more active there was Grand Montréal (The Gay and Lesbian The consultation publique sur la violence

“push-back” from other union members, Concertation Table of Greater Montreal) et la discrimination envers les gais et lesbi-

this is to be expected; one hopes that with asked the Quebec Human Rights Com- ennes (The public consultation on violence

committed leadership at the top, the rights mission to hold a public inquiry into the and discrimination against gays and les- The Confédération des syndicats nationaux

of minority workers can be advanced”. violence and discrimination perpetrated bians) was held from November 15 to 22, (CSN) and the Conseil central du Montréal

against members of the gay and lesbian 1993. This was the first inquiry of its kind métropolitain (CCMM-CSN), one of CSN’s

Early on, OPSEU participated in Toronto’s communities. in North America and was a turning point regional councils, made a joint submission

Pride Parade and, “In 1992 we had our for the gay and lesbian communities in to the Inquiry. The submission highlighted

own float in the Caribana Parade for the This same year, 1992, was also the 15th Quebec as well as for Québécois society. the need for legal protections against dis-

first time. Fred Upshaw [the President at anniversary of the prohibition of discrim- The final Report of the Commission was crimination as fundamental to gay and

the time], ‘got hell for this’ from others on ination based on sexual orientation in released in 1994. lesbian rights as workers and citizens, the

the Executive Board. They did not approve the Quebec Charter of Rights and Free- recognition of same-sex couples and the

OPSEU having a float in the Caribana doms. The Human Rights Commission inclusion of non-discrimination clauses

Parade. They did not see the point for this. was requested to explore several issues, in collective agreements. The CSN also

But that participation said to our members such as violence and discrimination from recommended that the Human Rights Com-

who were not active in their locals that the police, in workplaces and how the mission develop educational campaigns,

their union was interested in their cul- government was addressing this violence funded by the government, to raise public

tural activism and that led to a lot of them and discrimination or not. awareness about protections in the Charter

getting involved in their locals. It was a based on sexual orientation. The police,

low-cost event for such great returns. Until health, education and justice sectors were

my retirement in 2005, that was the only specifically identified for this. Their sub-

year that OPSEU had a float in Caribana”.16 mission included the results of a survey

of workers in the workplace on gay and

lesbian rights.

16 The very abridged history of the equity work in/of OPSEU

was documented by the author in conversations with

Beverley Johnson, a black heterosexual who was OPSEU’s

Human Rights Officer.You can also read