L'Art Pour l'Art: Experiencing Art Reduces the Desire for Luxury Goods - Oxford Academic

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

L’Art Pour l’Art: Experiencing Art Reduces

the Desire for Luxury Goods

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

YAJIN WANG

ALISON JING XU

YING ZHANG

When consumers shop in luxury boutiques, high-end shopping malls, and even

online, they increasingly encounter luxury products alongside immersive art dis-

plays. Exploring this novel phenomenon with both field studies and lab experi-

ments, the current research shows that experiencing art reduces consumer desire

for luxury goods. Three boundary conditions have been identified. The effect does

not materialize in contexts in which the work of art is not experienced as art per

se, such as when the work of art appears as decoration on the product or packag-

ing or is processed analytically rather than naturally, and when luxury goods are

not seen as status goods. We propose that experiencing art induces a mental

state of self-transcendence, which undermines consumers’ status-seeking motive

and consequently decreases their desire for luxury goods. This research contrib-

utes to the literature on consumer esthetics and has important practical applica-

tions for luxury businesses.

Keywords: luxury, art, environmental factor, self-transcendence, status, esthetics

Yajin Wang (yajinwang@ceibs.edu) is Professor of Marketing at the

A rt and luxury, at first glance, seem to be a perfect

pairing. Art is a creative artisan activity that results

in outcomes of esthetic and narrative appeal. Similarly,

China Europe International Business School (CEIBS), Shanghai, China.

Alison Jing Xu (alisonxu@umn.edu) is Associate Professor of Marketing, luxury has been defined as “expensive and exclusive prod-

at the Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota, ucts and brands that are differentiated from other offers

Minneapolis, MN, 55455, USA. Ying Zhang (zhang@gsm.pku.edu.cn) is based on their exquisite design and craftmanship, sensory

Professor of Marketing and Behavioral Science at the Guanghua School

of Management, Peking University, Beijing, China. Please address corre- appeal, and distinct socio-cultural narratives” (Wang

spondence to Ying Zhang. The work described in this study was partially 2021). Luxury firms thus seem to have good reasons to in-

supported by Dean’s Small Grant, Carlson School of Management, corporate art into their businesses. In addition, art initia-

University of Minnesota, to the second author, and by National Natural

Science Foundation of China, Grant No. 71925004, to the third author.

tives may attract attention, show corporate social

The authors would like to thank the editor, the associate editor, and the responsibility, and enhance customer experience (Grassi

anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and guidance 2019; Koenig 2017; Pine and Gilmore 1999; Schmitt 1999,

throughout the review process. The authors also thank Qihui Chen, 2003).

Zhengyu Shen, Yangming Ye, and Mengchen Zheng for their research as-

sistance. The authors gratefully acknowledge the helpful input from the These benefits may be on managers’ minds when luxury

research seminar participants at University of Maryland, Northwestern firms are creating extensive retail environments (offline

University, and China Europe International Business School (CEIBS). and online) in which consumers can experience art while

The authors also thank Galen Bodenhausen for his insightful comments

on this research. Supplementary materials are included in the web appen-

shopping (see appendix A for select examples). However,

dix accompanying the online version of this article. is it effective to surround consumers with art when they

shop in luxury boutiques, high-end shopping malls, and on-

Editor: Bernd Schmitt line? Exploring this new phenomenon of pairing art and

luxury in retail environments empirically, we find that,

Associate Editor: Christoph Fuchs counterintuitively, experiencing art (e.g., paintings, sculp-

tures, and artistic photographs) reduces consumer desire

Advance Access publication 15 April 2022

for luxury goods.

C The Author(s) 2022. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Journal of Consumer Research, Inc.

V

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-

use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Vol. 00 2022

https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucac016

12 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

This finding identifies an important consequence of art the effect of esthetics in product design, known as the art

initiatives on luxury brands. For example, Louis Vuitton infusion effect (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a). We show

launched art gallery spaces next to or above its stores that when art is experienced and appreciated as art, and not

around the world and displays art next to handbags and used strategically as decoration on the product or packag-

leather goods on its website. Gucci displays art next to its ing (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b, 2009), it has the

products online and has integrated art exhibition rooms effect of reducing consumer desire for luxury. Finally, our

into its shopping environment at Gucci Garden in Florence. research has practical relevance. Although a company’s de-

Well-known luxury department stores and malls in New cision to use art may be driven by multiple factors, practi-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

York (Nordstrom), Paris (Galeries Lafayette Haussmann), tioners need to be aware that when consumers experience

Singapore (Marina Bay Shoppes), and Beijing (Parkview art, it may undermine luxury consumption. Therefore, lux-

Green) have presented art shows. Beijing’s Parkview ury firms should consider whether other positive benefits

Green even hosts a permanent collection of more than 500 might outweigh this drawback before launching art initia-

works of arts (mostly sculptures), claiming its mall tives in luxury stores.

“redefines luxury shopping” (http://www.parkviewgreen.

com/eng/art/). However, based on our findings, these art THEORETICAL BACKGOUND

initiatives may have unintended drawbacks.

We observe the robust effect that experiencing art What is Art?

diminishes consumer desire for luxury goods in two field

The perennial question “What is art?” has led to intense

studies and in a series of lab studies. The first field study

shows that after viewing a real art exhibition, consumers debates among scholars across a wide variety of disci-

were less interested in a nearby luxury shopping mall than plines, including history, anthropology, philosophy, and

a non-luxury mall. In the second field study, after viewing psychology. In general, art is associated with creativity and

art in a mall, consumers were less interested in receiving esthetics. Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines art as

promotional materials from luxury brands. In the lab stud- “the conscious use of skill and creative imagination espe-

ies, when consumers experienced visual art images (in con- cially in the production of aesthetic objects.” Similarly,

trast to non-art images that were equally esthetically Hagtvedt and Patrick (2008a, 380) view art objects as

appealing) or visual images that were framed as art (in con- “skillful and creative expressions of human experiences, in

trast to the same images that were framed as non-art), they which the manner of creation is not primarily driven by

were less likely to choose luxury brands, and less interested any other function.” Art also elevates viewers from every-

in and less likely to purchase luxury products. We hypothe- day mundane pursuits to transcend their daily lives

size that these findings occur because experiencing art (Berlyne 1974; Joy and Sherry 2003; Wartenberg 2006).

induces a process of “self-transcendence,” which decreases Art spans a wide spectrum, ranging from visual art to

the significance of the self and suppresses mundane music and dance. In this article, we focus exclusively on

thoughts, including concern about other people (Maslow visual art, which includes painting, sculpture, photography,

1969; Yaden et al. 2017). Self-transcendence, in turn, installations, and mixed media. In general, visual art can be

dampens the status-seeking motive that drives luxury con- classified as classic art (e.g., works from the Renaissance

sumption (Han, Nunes, and Drèze 2010; Ordabayeva and and Baroque periods to Impressionism), art from the mod-

Chandon 2011). In our studies, we explore and delineate ern period, and contemporary art. For modern and contem-

the phenomenon by showing when it occurs and when it porary art in particular, social norms often determine what

does not. We find that the effect occurs only when art is re- viewers consider to be art. That is, experts (art historians,

ally experienced as art. In contrast, the effect does not oc- curators, critics, and artists themselves) may declare works

cur when art is experienced for other purposes, such as as art when an art object becomes part of a collection in a

being strategically placed on the product or packaging for museum, gallery, or art-related event.

decoration or marketing purposes, or being processed ana- Because social norms determine, in part, what qualifies

lytically with a focus on technical details. The effect also as art, we confine our investigation to stimuli that most

does not occur when luxury goods are not framed as status consumers would clearly consider art (Hagtvedt 2020;

objects. Finally, we present evidence that the core effect is Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b). Specifically in our

mediated by self-transcendence. Overall, these results indi- studies, we feature classic and modern paintings by promi-

cate that art—if experienced as l’art pour l’art (art for art’s nent artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Jan van Eyck,

sake)—reduces the desire for luxury because art induces a William Turner, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, and

state of self-transcendence in consumers, which suppresses Pablo Picasso as well as established contemporary sculp-

their status-seeking motive. tors and photographers. In addition, we do not present just

Our research is the first to investigate whether, when, one work of art in isolation; rather, our field and lab studies

and how art in environments affects consumer desire for include displays of collections of art objects, which reinfor-

luxury products and thus complements prior literature on ces that the objects are indeed art rather than non-artWANG, XU, AND ZHANG 3

objects. Finally, note that the focus of our research is not a Experiencing Art Elicits Self-Transcendence

particular artist, genre, or style. We are interested in how

The experience of visual art has been shown to evoke a

visual art in general—as an overall elevated expression of

wide range of emotions, including happiness, awe, sadness,

the human experience—affects individuals in their role as and even anger and contempt (Cupchik et al. 2009; for a re-

actual or potential luxury consumers. view, see Silvia 2005). Art, however, evokes more than

emotions, given that it is one of the most profound human

The Influence of Art on Consumer Choice symbolic activities (Read 1965). Phenomenologically, the

art experience differs from the esthetic experience because

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

A rich stream of consumer literature has examined how art extends beyond beauty to reflect the artist’s intentions,

the visual processing of design influences product choices the work’s place in history, as well as political and social

and preferences (Hoegg and Alba 2008; Wyer, Hung, and dimensions (Sibley 1965). Scholars have also contended

Jiang 2008). Different product design features such as that art appeals to people because of its figurative meaning

physical size (Silvera, Josephs, and Giesler 2002), shape (Babcock 1978; Holbrook and Hirschman 1993). In work

(Jiang et al. 2016), and attractiveness (Hoegg, Alba, and on experiential consumption (Holbrook and Hirschman

Dahl 2010; Wu et al. 2017) have been shown to affect con- 1982, 1993), art has been singled out for its particularly

sumer choice and consumption. rich and salient symbolic meaning.

Of particular relevance to our study is the finding that Of particular importance to our research are philosophi-

the esthetic features of products can positively influence cal ideas about art. As Kant (1790/1987) pointed out, the

consumers’ perceptions and evaluations of these products symbolic meaning of art interacts with people’s percep-

and brands (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b; Lee, tions, intellect, and imagination, creating “disinterested

Chen, and Wang 2015; Schmitt and Simonson 1997; interest,” which could be recast as “liking without

Townsend and Shu 2010). Importantly, associating a prod- wanting.” Art elevates the viewers from daily mundane life

uct with a work of art either directly (through product de- and compels them to face their own insignificance. As a re-

sign) or indirectly (through packaging and advertising) can sult, neo-Kantian philosopher Cassirer (1944) argues that

enhance the image and consumers’ evaluations of the prod- art symbolism elevates individuals to a mental state during

uct (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, 2008b; Townsend and which mundane matters are less concerning. Relatedly,

Shu 2010). For example, a set of ordinary silverware with Dewey (1934) argues that art elicits thoughts concerning

an image of Vincent van Gogh’s Caf e Terrace at Night on issues beyond people’s everyday routines. In a consumer

top of the package can make the product seem more luxuri- context, Venkatesh and Meamber (2006, 20) emphasize

ous and result in more positive evaluations compared with that “the consumer of art responds to it differently when

the same silverware with a non-art picture on the package compared to more mundane objects in life.” In short, art

(Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a, study 1). Similarly, printing can induce a mental state where the mundane is less of a

an art image on a soap dispenser can lead to a more posi- concern. In his esthetic theory, Beardsley (1958/1981,

tive perception of a brand extension (Hagtvedt and Patrick 1966) calls this state of mind “self-transcendence.”

Self-transcendence has been studied in cognitive, clini-

2008b). In sum, when the image of a work of art is pre-

cal, and social psychology (Frankl 1966; Haidt 2012;

sented as an integral part of the product (Hagtvedt and

Koltlo-Rivera 2006; Piedmont 1999; Van Cappellen and

Patrick 2008a, study 1) or is strongly associated with the

Rime 2014). Self-transcendence can be experienced at dif-

product (e.g., in an advertisement, Hagtvedt and Patrick

ferent levels of intensity; at the extreme, it may encompass

2008b, study 1), consumers tend to have more positive a sense of awe, elevation, and admiration (Haidt and

reactions to the product and brand, presumably because of Morris 2009; Rudd, Vohs, and Aaker 2012), similar to a

a positive “spillover effect.” “transcendent” or “extraordinary” experience (the Latin

However, when works of art are experienced on their prefix extra referring to “outside” or “beyond”) (Arnould

own as art for art’s sake, they may elicit responses that are and Price 1993; Schouten, McAlexander, and Koenig

different from seeing the image of a work of art printed on 2007). This is consistent with early discussions of self-

a product. The increasingly common presence of display- transcendence by Maslow (1969), who describes emotions

ing art pieces in consumption-related environments such as associated with self-transcendence as a “peak experience.”

retail malls thus raises the question of how art is experi- As Maslow (1969) describes, the feelings during such

enced in this context and how it might affect luxury con- moments are rich and often associated with complex

sumption. Next, we review literature on the psychological expressions of wonder, amazement, awe, reverence, and

consequences of experiencing art and propose that art elic- humility.

its the mental state of self-transcendence, which, we argue, The mental state induced by art also entails the fading

reduces consumers’ status-seeking motive and, in turn, away of the subjective sense of one’s self as an isolated en-

their desire for luxury goods. tity; as a consequence, purely personal pursuits become4 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

less important (Koltlo-Rivera 2006; Levenson et al. 2005; 2010; Piff et al. 2010, 2012). Status-seeking, by nature,

Maslow 1969; Read 1991; Schwartz 1992). Maslow (1969) also includes a comparison of one’s own social rank with

considers self-transcendence as the highest level of motiva- that of others and is driven by the desire to outrank others

tion (even beyond self-actualization), where an experience in society (Anderson, Hildreth, and Howland 2015; Dubois

extends beyond the personal self and ego and seeks com- and Ordabayeva 2015). Given that self-transcendence, in-

munion with the transcendent. Interestingly, neuroscient- duced by experiencing art, decreases the significance of

ists who study art have also argued that art transcends one’s self and suppresses mundane thoughts including con-

thoughts of self-centered pursuits (Chatterjee 2014; cerns about other people, we expect that experiencing art

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

Cupchik and Winston 1996; Dutton 2009). Therefore, the should undermine self-centered status-seeking motivations

psychological state of self-transcendence suppresses mun- and, in turn, the desire for luxury goods. We summarize

dane concerns including self-centered pursuits, self- our hypotheses and empirical works next.

interested related thoughts, and others’ opinions toward

oneself (Cupchik and Winston 1996; Dutton 2009). HYPOTHESES AND OVERVIEW OF THE

In sum, we argue that the art experience elicits a mental

state of self-transcendence that, overall, decreases the sig-

EMPIRICAL STUDIES

nificance of one’s sense of self (Bai et al. 2017). In doing Our research is guided by three core hypotheses.

so, the state of self-transcendence reduces the focus on Hypothesis 1 relates to the central phenomenon that we ex-

one’s own desires and shifts attention away from the self pect to emerge from our studies: experiencing art reduces

(Haidt and Morris 2009; Maslow 1969, 1993), including consumer desire for luxury goods. Hypothesis 2 relates to

decreased attention to others’ opinions of oneself and the the moderators of this phenomenon: we hypothesize that

desire for monetary gains (Antonucci 2001; Jiang et al. the effect proposed in hypothesis 1 occurs only when con-

2018; Loy 1996). sumers experience and appreciate art as art per se and

Having explicated the mental state of self-transcendence when the luxury good is perceived as a status good. When

elicited by experiencing art, we next argue that self- consumers experience art not as art for its own sake but for

transcendence inhibits consumers’ status-seeking motive, other purposes, or luxury products are not seen as status

which is at the core of the desire for luxury consumption.

goods, the effect should be attenuated. Finally, hypothesis

3 proposes that self-transcendence can account for the phe-

Self-Transcendence Undermines Consumers’ nomenon; that is, the effect occurs because experiencing

Status-Seeking Motive and Reduces the Desire art elicits the mental state of self-transcendence, which

for Luxury undermines consumers’ status-seeking motives.

Luxury goods are exclusive products offered at a pre- We test these three hypotheses in eight studies, con-

mium price and quality (Fuchs et al. 2013; Nelissen and ducted both in the field and in the lab. In the first group of

Meijers 2011; Patrick and Hagtvedt 2009; Wang 2021), studies, we test the hypothesis related to the core phenome-

and brands such as Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Prada, and BMW non that experiencing visual art reduces consumer desire

are widely viewed as prime examples (Berger and Ward for luxury goods (hypothesis 1). We demonstrate this basic

2010; Fuchs et al. 2013; Han et al. 2010). While luxury effect in three studies: two field studies (studies 1a and 1b)

products may be sought for various reasons (e.g., quality, and one lab experiment (study 1c) in which we manipulate

craftsmanship, or esthetic appeal; Wang 2021), one of the an art versus non-art experience by framing the same visu-

primary motivations driving luxury consumption is the de- als differently. The second group of studies establishes

sire to seek and display social status (Han et al. 2010; boundary conditions through moderators (hypothesis 2).

Nelissen and Meijers 2011; Ordabayeva and Chandon We show that the hypothesized negative effect of

2011; Veblen 1899). As a result, luxury products are pro- experiencing art on consumer desire for luxury diminishes

moted as status symbols, and consumer desire to obtain when art is not experienced as purely art because the work

luxury goods and brands is largely driven by motivation of art offers instrumental value, such as decorating a prod-

for status and power (Dubois and Ordabayeva 2015). For uct (study 2a); or the work of art is seen analytically and

example, people with a high need for social status usually not naturally (study 2b); or the luxury firm positions the

show an enhanced desire for luxury goods (Han et al. product not as a status product (study 2c). The final two

2010). Lack of status (e.g., induced by a sense of power- studies provide evidence for the proposed psychological

lessness) also leads to greater interest in luxury goods be- process (hypothesis 3). Study 3a shows that experiencing

cause such consumption can compensate for the feelings of art induces self-transcendence, which, in turn, dampens

powerlessness (Rucker and Galinsky 2008, 2009). consumer desire for luxury goods. Study 3b tests the full

The status-seeking motive inherent in the desire for lux- logical link that the art experience induces the mental state

ury is a self-centered motivation; that is, people highly pri- of self-transcendence, which in turn reduces the status-

oritize their own interests and concerns (Maner and Mead seeking motive and dampens the desire for luxury goods.WANG, XU, AND ZHANG 5

In this study, we use a combination of moderation-of- Consumer Choice and Browsing Behavior. Participants

process and measurement-of-mediation approaches in were informed that the purpose of the study was to ask con-

which we manipulate the absence of self-transcendence to sumers for their opinions about shopping malls.

eliminate the hypothesized effect and measure the status- Participants were asked to indicate their shopping preferen-

seeking motive to establish a mediating role. Together, the ces, and they were given descriptions of two nearby malls.

final two studies provide evidence for the roles of self- To increase external validity, both malls were located

transcendence and the status-seeking motive in mediating within a 10-minute walk from the metro station. One of

the effect of the art experience on desire for luxury goods. them is a luxury mall, carrying high-end brands such as

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

Prada, Gucci, Saint Laurent, and Bulgari. The other is a

STUDY 1A: ENCOUNTERING AN ART mid-level mall, carrying affordable brands such as H&M,

EXHIBITION REDUCES INTEREST IN A Calvin Klein Jeans, and Nike. Participants read short

NEARBY LUXURY SHOPPING MALL descriptions of each mall and then were asked to choose

one of the two malls to get more information about it, in-

We begin our investigation into the effects of experienc- cluding ongoing promotions. Clicking on the name of the

ing art on luxury consumption by examining whether en- chosen mall directed participants to the corresponding

countering art as part of an exhibition can reduce consumer website, which constituted our main dependent measure.

interest in luxury. This field study was conducted at a Participants browsed the website of the mall they chose for

metro station in Shanghai, China, where London’s as long as they wanted, and then they proceeded to answer

National Gallery was hosting a 30-day art exhibition in the remaining survey questions.

June 2018. We approached consumers who viewed the art Manipulation Checks. After responding to the main de-

exhibition as well as those who were unlikely to have pendent variable, participants answered a few manipulation

viewed the art exhibition. We assessed their interest in lux- check questions. First, they reported their perceptions of

ury by comparing their choice to search for more informa- how luxurious the two shopping malls were (within-sub-

tion about a luxury mall or a non-luxury mall nearby. ject; 3-point scale: 1 ¼ low end, 2 ¼ middle level, 3 ¼ high

end). The results confirmed that participants perceived the

Methods luxury mall as more high-end and luxurious than the mid-

level mall (M ¼ 2.58 vs. 2.01, t(135) ¼ 10.50, p < .001,

Participants. Two research assistants were asked to ap-

Cohen’s d ¼ 0.91). An additional manipulation check ques-

proach approximately 150 participants over three days:

tion asked participants to indicate whether they had seen

136 participants were successfully approached and com-

the art exhibition. Consistent with our expectation, 98.6%

pleted the survey (Mage ¼ 25.68, SD ¼ 6.08, 67% female);

of the consumers in the art condition had viewed the art

14 people declined to participate.

exhibition, compared with 26.6% of the consumers in the

Procedure. The art exhibition, located near one of the control condition. Finally, participants were asked to pro-

exits of the metro station, displayed master paintings by vide demographic information, such as age, gender, and in-

Leonardo da Vinci, Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, and come level.

other artists on a 30-meter-long panel inside the South

Shaanxi Road metro station in Shanghai (see exhibition Results and Discussion

details in appendix B and web appendix A). Two locations We tested hypothesis 1 by examining whether the likeli-

in the station were chosen as sites where the research assis- hood of choosing to view the websites of the luxury shop-

tants recruited participants. One location (the art condition) ping mall differed between the art and control groups.

was next to the art exhibition panel on the way to the near- Consistent with our prediction, a chi-square test revealed

est exit. The research assistant was instructed to approach that consumers in the art condition were less likely to

people who had stopped in front of the exhibition and choose to browse the website of the high-end luxury mall

looked at the paintings for some time. The other recruiting than the control condition (51.4% vs. 70.3%, v2 (1) ¼

location (the control condition) was near a different exit 5.07, p ¼ .024, OR ¼ 0.45). Study 1a thus demonstrates

where passengers were unlikely to have seen the panel. the basic effect that experiencing art reduces consumer in-

The two research assistants switched roles during the data terest in luxury shopping.

collection period (see web appendix A for details). One potential criticism of the design of study 1a is self-

Participants were approached and asked if they would like selection bias. That is, some consumers may have self-

to complete a short survey. People who agreed to partici- selected to view the art exhibition and therefore chosen the

pate completed the survey on iPads. After participating, exit where the exhibition was located. These “artsy types”

they were thanked and received a small cash may be different from the other group, and they may be

compensation. less interested in luxury to begin with. We attempted to6 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

minimize this bias by conducting the study in a busy sub- website (www.parkviewgreen.com/eng/art) states that “Art

way station rather than in an art museum or gallery. is Parkview Green’s most distinctive feature. . . Parkview

Nonetheless, we conducted a second field experiment to Green will redefine luxury shopping and recreation, as visi-

better control for self-selection bias in the study design. tors will have the opportunity to experience a truly artistic

mall.” For the non-art mall, we selected a nearby shopping

STUDY 1B: VISITING AN ART MALL mall (The Kerry Center), which displayed no works of art

at the time of the study (see appendix C for example pic-

REDUCES INTEREST IN PROMOTIONAL

tures of both malls). The Kerry Center is a 10-minute walk

MATERIAL FROM LUXURY BRANDS

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

from Parkview Green Mall. Both malls carry mid-level af-

Study 1b serves three purposes. First, the field study pro- fordable brands as well as high-end luxury brands (see the

vides additional external validity and shows the practical manipulation check results) and attract the same clientele.

relevance of our phenomenon because the study was con- To manipulate whether shoppers had experienced art or

ducted in a real shopping environment. Two different shop- not, the research assistants recruited participants at differ-

ping malls located close to each other were chosen as the ent mall locations. In the outside art-mall condition, the re-

search assistants recruited shoppers before they entered the

settings. Both are equally luxurious but differ in whether

mall. In the inside art-mall condition, the research assis-

they display art in the retail environment. One mall (the art

tants recruited shoppers who were already inside and about

mall) displayed works of art, whereas the other mall (the

to leave the mall to make sure they had experienced the art

non-art mall) did not feature works of art at the time of

inside the mall. In the non-art-mall condition, shoppers

study.

were also approached either outside or inside the mall fol-

Second, the study extends our investigation from one

lowing the same instructions. All shoppers were asked if

form of visual art (i.e., paintings in study 1a) to a different

they would like to complete a short survey about their

form of visual art (i.e., sculptures in study 1b).

shopping preferences and habits. Participants completed

Specifically, besides some paintings, the art mall primarily

the survey on iPads and received cash compensation.

features more than 500 mostly modern and contemporary

small and large sculptures. The sculptures are interspersed Choice of Promotion Message. We showed partici-

throughout the open spaces of the building, creating an ar- pants a partial list of the brands sold in each mall. For each

tistic environment inside the mall. list, there were two sets of brands: the first set included af-

Third, the study utilizes a design that controls for self- fordable, mid-level brands (e.g., GAP and Fila), and the

selection bias. Specifically, in the art mall condition, we second set included high-end luxury brands (e.g., Van

approached shoppers either outside at the entrance of the Cleef & Arpels and Dunhill). Participants were told that

art mall before they entered (control condition) or inside they could choose to receive promotional materials from

the mall after they had experienced art (experimental con- either set of brands by clicking on their selected set. This

dition). In the non-art mall condition, participants did not choice served as the main dependent measure.

experience art regardless of whether they were recruited Manipulation Check. Participants answered questions

outside or inside the mall, which provides two additional on their perceived brand positioning of the mall (1 ¼ low

control conditions. We predicted that experiencing art in- end, 2 ¼ middle level, 3 ¼ high end) and how artsy it was

side the art mall should reduce consumer interest in luxury, (“To what extent do you think this mall is artsy?” 1 ¼ not

compared with the three control conditions. at all, 7 ¼ very much), among other filler items (e.g., “How

do you like the decoration of this shopping mall?”).

Method Finally, all shoppers were asked to provide demographic

Participants and Design. The field study used a 2 (type information and were thanked for their participation.

of mall: art mall vs. non-art mall) 2 (location of study:

outside the mall vs. inside the mall) between-subjects de- Results

sign. The study was conducted on different days during Manipulation Check. Shoppers considered the two

shopping hours by separate teams of research assistants malls to be at a similar level of positioning (M ¼ 2.54 vs.

who were blind to the hypothesis. We had planned to ap- 2.44, F(1, 204) ¼ 1.85, p ¼ .175). Shoppers perceived the

proach approximately 200 consumers for this study, and art mall as significantly more “artsy” than the control mall

206 consumers (Mage ¼ 28.21, SD ¼ 7.10, 57.3% female) (M ¼ 5.33 vs. 4.11, F(1, 204) ¼ 46.43, p < .001, Cohen’s d

were successfully recruited and completed the survey for a ¼ 0.95).

small monetary compensation.

Choice. We examined the interactive effect of the mall

Procedure. Beijing Parkview Green, the art mall, is type (art mall vs. non-art mall) and location of the survey

known for exhibiting works of art such as sculptures (as (outside the mall vs. inside the mall) to determine how the

well as some paintings) in the open spaces in the mall. The art and non-art environments affected consumerWANG, XU, AND ZHANG 7

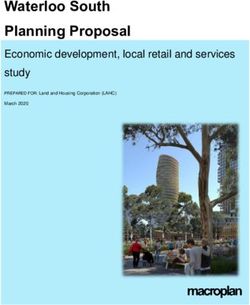

FIGURE 1 that experiencing art reduces consumer interest in luxury in

consumer-relevant field settings. Next, we provide causal

CHOICE OF PROMOTIONAL MESSAGES FROM LUXURY evidence for the phenomenon in a controlled lab experi-

BRANDS BY THE TYPE OF MALL (STUDY 1B) ment. In this experiment, we also examine the effect with

another art form (photography) and a new manipulation of

Choice of Promoon from Luxury Brands

60.00%

the art versus non-art experience.

50.00% Non-Art Mall

40.00% Art Mall STUDY 1C: PHOTOGRAPHS FRAMED AS

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

30.00%

ART REDUCE INTEREST IN A LUXURY

PRODUCT

20.00%

10.00%

In study 1c, we use photographic images as stimuli. We

present them to participants online in a video clip, similar

0.00% to how art has been presented on the websites of luxury

Outside the Mall Inside the Mall

Locaon of Survey

brands. Most importantly, we frame the photographs as ei-

ther art or non-art. By using the same visual images and

framing them as art or non-art, we tightly control the con-

tent of the visuals and sensory engagement and simply

preferences for receiving promotional materials from the vary whether participants perceive them as art or not. This

luxury brands versus mid-level brands. A binary logistic is consistent with our theorizing: art must be perceived as

regression revealed the predicted interaction (b ¼ 1.23, art by consumers for the effect to occur.

SE ¼ 0.58, Wald ¼ 4.44, p ¼ .035, OR ¼ 0.29; figure 1);

there were no main effects of the type of mall (b ¼ 0.10, Methods

SE ¼ 0.40, Wald ¼ 0.07, p ¼ .797) or location (b ¼ Participants and Design. A total of 186 participants

0.23, SE ¼ 0.39, Wald ¼ 0.35, p ¼ .552). Confirming (Mage ¼ 20.46, SD ¼ 1.11, 64.6% female) from a public

hypothesis 1, shoppers in the art mall were less likely to university in North America were recruited in exchange for

choose to receive promotions from luxury brands when partial course credit. They were randomly assigned to one

surveyed inside the mall (24.5%) than outside the mall of two conditions: framing visuals as art versus non-art.

(46.8%, v2(1) ¼ 5.44, p ¼ .02, OR ¼ 0.37). However, for

the non-art mall, no difference was observed between Procedure. Participants came to the lab and were indi-

shoppers who were surveyed outside (44.2%) and inside vidually seated in private cubicles. They were told that the

the mall (50%, v2(1) ¼ 0.35, p ¼ .55). research section included two short unrelated studies. The

We also tested the simple effect of the mall type (i.e., art first study involved a visual task where participants

mall vs. non-art mall) at different survey locations (outside watched a 100-second video clip that contained six visuals.

the mall vs. inside the mall). Among the shoppers surveyed Using this procedure, the exposure time and content were

outside the malls, there was no difference in the choice of identical for participants in all conditions. The visuals were

luxury brands (Mart ¼ 46.8% vs. Mnon-art ¼ 44.2%, v2(1) ¼ photographs of plants by Karl Blossfeldt, a photographer

0.07 p ¼ .797), minimizing the possibility of self-selection and artist known for close-up photographs of plants and

bias. However, among the shoppers who were surveyed in- other living things. Participants in the art-framing condi-

side the shopping malls, those in the art mall were signifi- tion read that the photographs were taken from an art book

cantly less likely (24.5%) to choose to receive promotional featuring a collection of artistic images of plants. They also

materials from luxury brands than those in the control mall read that the artist is known for his acute sense of the ex-

condition (50%, v2(1) ¼ 7.41, p ¼ .006, OR ¼ 0.33), indi- quisite and sublime beauty of plants. In the non-art-fram-

cating that the experience of an art environment had an im- ing condition, participants read that these photographs

pact on their preference. were from a botany book that documents a collection of

botanical images of plants, and the botanist is known for

his accurate documentation of horticultural and floral fea-

Discussion

tures of the plants (for detailed manipulations, see appen-

The results of study 1b replicated the findings of study dix D). Using this procedure, we ensured that while

1a in a real shopping environment and again supported hy- participants saw the exact same photographs for the same

pothesis 1. We found that experiencing a shopping envi- length of time, they experienced the visuals either as art or

ronment where works of art were prominently displayed non-art.

significantly reduced consumer desire for luxury brands. Next, participants moved to a second ostensibly unre-

Together, the two studies demonstrate the phenomenon lated study in which their interest in luxury goods was8 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

measured. They evaluated the LV Pochette Jour, a product merchandise (e.g., on the packaging or on a shopping bag)

by the brand Louis Vuitton, which can be used as a clutch, versus when art is in the environment around the product.

laptop holder, or document portfolio (see web appendix B Indeed, luxury brands often incorporate art images strategi-

for visuals). Participants were asked to evaluate the product cally into their products to make them more appealing. For

on three attitude items (e.g., “I think the product is: example, Louis Vuitton collaborated with contemporary

unfavorable ¼ 1, favorable ¼ 7; negative ¼ 1, positive ¼ 7; artist Jeff Koons to put images of works of art on luxury

unpleasant ¼ 1, pleasant ¼ 7”). The average of the three bags and backpacks. Similarly, Hermès printed the work of

items formed the main dependent measure (a ¼ 0.89). artists on its scarves.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

When art becomes part of a commercial product, the

Manipulation Pretests. To ensure that the manipulation

purpose is not solely to appreciate art per se. In the words

of framing the images as art or non-art would lead partici-

of philosopher and art critic Benjamin (1935/1968), art

pants to perceive them differently, a separate sample of

loses its “aura” when it is reproduced for a commercial pur-

202 participants from Mturk (Mage ¼ 35.65, SD ¼ 10.28,

pose. Art is then not only experienced as art for its own

41.9% female) was randomly assigned to read the art or

sake but also as a product attribute. As a result, the elevated

non-art framing instructions for the six photographs. After

mental state of self-transcendence is unlikely to occur and

viewing each photograph, they rated how artistic the photo-

the negative effect on consumer interest in luxury should

graphs were on a 7-point scale (1 ¼ not at all, 7 ¼ very

not be observed. Study 2a tests this boundary condition.

much). The results revealed that participants rated the pho-

tographs in the art-framing condition as significantly more

artistic than visuals in the non-art-framing condition (aver-

Method

age score of the six images: Mart ¼ 5.61 vs. Mnon-art ¼ Participants and Design. A total of 193 participants

5.20, F(1, 200) ¼ 10.61, p ¼ .001, gp2 ¼ 0.05). (Mage ¼ 20.21, SD ¼ 2.51, 44% female) from a public uni-

versity in North America were recruited for this study in

Results and Discussion exchange for partial course credit. They were randomly

assigned to one of three conditions: art on the package ver-

We predicted that viewing visuals framed as art (vs.

sus art in the environment versus the control. The control

non-art) would reduce interest in the Louis Vuitton prod-

condition, which did not include exposure to art, was used

uct. The results confirmed our prediction; participants in

to assess the baseline evaluation of the target luxury

the art-framing condition evaluated the LV Pochette Jour

product.

less favorably than those in the non-art-framing condition

(Mart ¼ 3.88, SD ¼ 1.20 vs. Mnon-art ¼ 4.25, SD ¼ 1.20, Procedure. Participants came to the lab and were indi-

F(1, 184) ¼ 4.50, p ¼ .035, gp2 ¼ 0.024). This result once vidually seated in private cubicles. They were told that the

again supports hypothesis 1 that experiencing art dampens research session was to gather their thoughts about certain

the desire for luxury goods. luxury brands and products. In the art on the package con-

In sum, in the first group of three studies (two field stud- dition, they were told that Louis Vuitton “plans to intro-

ies and a lab experiment), we have established the phenom- duce new packaging that incorporates the visuals of some

enon that experiencing art reduces consumer desire for famous paintings into the design.” Next, they were pre-

luxury. All the results support hypothesis 1. In the next sented with a series of “newly designed Louis Vuitton

group of three experimental studies, we further examine packages.” We hired a professional advertising agency to

the phenomenon by identifying boundary conditions of the design eight Louis Vuitton package boxes, each with a

effect. Following hypothesis 2, we predict that the effect classic painting on the lid (e.g., Water Lilies and Japanese

occurs only when art is experienced as art per se and when Bridge by Claude Monet and The Starry Night by Vincent

the luxury good is perceived as a status good. However, we van Gogh; see appendix E for visual examples and web ap-

expect the effect to be attenuated when art is experienced pendix C for full materials). In the art in the environment

for other purposes (such as being part of product packaging condition, participants were told that Louis Vuitton “plans

or being viewed with a focus on the technical details) or to host an art exhibition in its flagship store” and were then

when the luxury good is presented as a non-status good. asked to view some of the paintings that might be included

in the exhibition. The same eight paintings as those used in

the art on the package condition were presented to partici-

STUDY 2A: ART IN THE ENVIRONMENT

pants. In both conditions, participants spent as much time

(BUT NOT ON PACKAGING) REDUCES as they wanted looking at the packages or the paintings in

INTEREST IN A LUXURY PRODUCT the art exhibition. Finally, in the control condition, partici-

pants did not see any visual stimuli.

In the studies reported above, participants experienced

art by appreciating art per se. In this study, we test what Dependent Measures. Participants evaluated an LV

happens when art appears as part of a luxury product or Pochette Jour product that can be used as a clutch, laptopWANG, XU, AND ZHANG 9

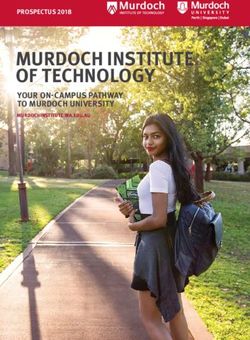

holder, or document portfolio (see web appendix C for vis- FIGURE 2

uals). The product was displayed next to a Louis Vuitton

box. Participants in the art on the package condition saw ART IN ENVIRONMENT VERSUS ART ON THE PRODUCT

the package box with an art image printed on it (one of the PACKAGING (STUDY 2A)

same package boxes they saw earlier). Participants in the 7

Luxuruy Product Evaluations

other two conditions saw a regular Louis Vuitton box with-

6

out art images. Next, participants were asked to evaluate

the product on five items (e.g., “I think the product is: 5

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

unfavorable ¼ 1, favorable ¼ 7; negative ¼ 1, positive ¼ 7;

4

bad ¼ 1, good ¼ 7; unpleasant ¼ 1, pleasant ¼ 7; How

much do you like this product?: dislike very much ¼ 1, like 3

very much ¼ 7”). The average of the five items formed the 2

main dependent measure (a ¼ 0.96).

Finally, participants in the art on the package condition 1

Control Art in Environment Art on Package

were asked how much they enjoyed viewing the packages

and how much they liked the idea of including the paint-

ings on the package. Similarly, participants in the art in the

environment condition were asked how much they enjoyed effect, prior research examined non-luxury products. In

viewing the paintings as part of the art exhibition in the contrast, in the present study, the art was added to a luxury

flagship store and how much they liked the idea of includ- product. Our results show that including art images on the

ing them in the art exhibition. Finally, they rated the luxu- package of a luxury product only directionally increases

riousness of the product on four 7-point items from the attractiveness. This limited positive effect likely oc-

Hagtvedt and Patrick (2008a). curred because the product was already a luxurious product

and thus the perceived luxuriousness could not easily be

Results further increased. Therefore, reconciling our findings with

Luxury Product Evaluations. A one-way ANOVA previous research, we suggest that incorporating art images

revealed a significant main effect of treatment conditions on packages has a much greater positive effect for non-

on the luxury product evaluations (F(2, 190) ¼ 5.82, p ¼ luxury products than luxury products.

.004, gp2 ¼ 0.06; figure 2). A series of planned contrasts In addition, we found that participants reported similar

was performed to test our predictions. First, participants in levels of enjoyment viewing the art on the package and

the art in the environment condition showed significantly viewing art in the environmental (M ¼ 5.13 vs. 5.14, F(1,

less interest in the luxury product (M ¼ 4.02, SD ¼ 1.47) 127) ¼ 0.003, p ¼ .96). Participants also liked the idea of

than participants in the control condition (M ¼ 4.66, including art in the store environment as much as they

SD ¼ 1.47, F(1, 190) ¼ 6.46, p ¼ .012, gp2 ¼ 0.03). This liked the idea of including art on the packaging (M ¼ 5.02

replicated our main finding that experiencing art as art per vs. 5.38, F(1, 127) ¼ 1.85, p ¼ .18). Moreover, they judged

se reduces consumer interest in luxury goods, supporting the product to be equally luxurious in all conditions

hypothesis 1. Moreover, consistent with our prediction, par- (M ¼ 4.84 vs. 5.04 vs. 5.21, F(2, 190) ¼ 1.13, p ¼ .33, re-

ticipants in the art in the environment condition (M ¼ 4.02, spectively, for the environment, package, and control con-

SD ¼ 1.47) also indicated significantly lower interest in the ditions). However, participants evaluated the products less

luxury product than those in the art on the package condi- positively when art was prominently featured in the envi-

tion (M ¼ 4.83, SD ¼ 1.35, F(1, 190) ¼ 10.47, p ¼ .001, ronment, which is consistent with hypothesis 2.

gp2 ¼ 0.05). Finally, product evaluations in the art on the

package condition were non-significantly higher than those STUDY 2B: VIEWING ART NATURALLY

in the control condition (F(1, 190) ¼ 0.48, p ¼ .49, gp2 ¼ (BUT NOT ANALYTICALLY) REDUCES

0.003). This pattern of results provided important evidence INTEREST IN BUYING LUXURY

for our conceptualization and supported hypothesis 2 by CLOTHES

suggesting that (1) experiencing art only caused the hy-

pothesized effect when it is experienced as art and (2) Our conceptualization posits that experiencing art

when art becomes part of product packaging, it has no im- reduces consumer desire for luxury goods because appreci-

pact on consumer interest in luxury products. Importantly, ating art per se elicits a sense of self-transcendence. We ar-

our findings also add nuance to prior research that demon- gue specifically that the symbolic meanings of art lead to

strated that adding art to product packaging enhances the this mental state during which mundane matters are less

appeal of a product due to the increased perception of luxu- concerning. Prior research indicates that different process-

riousness (Hagtvedt and Patrick 2008a). To show this ing styles might affect how people experience art10 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

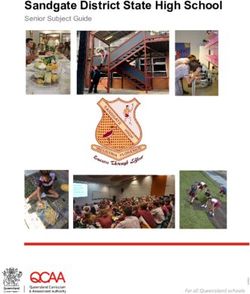

FIGURE 3 In the natural viewing conditions, participants viewed

the 10 visuals without additional instructions. In contrast,

ANALYTIC VIEWING OF ART DIMINISHES THE NEGATIVE in the analytic viewing conditions, participants were asked

INFLUENCE OF THE ART EXPERIENCE ON LUXURY (STUDY to evaluate the lines and colors of each of the same 10 visu-

2B)

als in detail. Specifically, they were asked to rate each pic-

7 ture on a 7-point scale for the following two items: (1)

6

Non-Art Art “How much do you like the color of this picture?” and (2)

Interest in Luxury Brand

“How much do you like the lines of this picture?”

5

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

Next, participants were presented with a second ostensi-

4 bly unrelated study where we measured their interest in

3

luxury goods. Participants were asked to imagine that they

were considering buying clothes and to separately rate their

2

interest in “high-end, expensive brands” and “mainstream,

1 affordable brands” (1 ¼ Not at all interested, 7 ¼ Extremely

Neutral Analycal interested).

Viewing Mode Included at the end of the survey were debriefing ques-

tions asking participants to guess the purpose of the study.

None of the participants saw a connection between their

viewing of visuals and their interest in different brands,

(Liberman and Trope 1998). Therefore, we expected that and none guessed the hypothesis that viewing art would

self-transcendence may be interrupted when art is proc- lead to less interest in luxury brands. Therefore, the ob-

essed in particular ways. In study 2b, we asked participants served negative effects of art experience on interest in lux-

to either view and appreciate art naturally or to analyze ury goods were not due to demand characteristics.

works of art by paying specific attention to the technical

elements, such as lines and colors. We expected that view- Manipulation Pretest. To ensure that the art and non-

ing a work of art analytically (i.e., by focusing on the tech- art conditions were perceived as similar in their esthetic

nical details of the work of art rather than appreciating it value but different in their artistic value, a separate sample

naturally as a whole in terms of the symbolic meaning) of 168 participants (Mage ¼ 20.36, SD ¼ 2.82, 49.4% fe-

should eliminate the negative effect on consumer interest male) from the same population was randomly assigned to

in luxury goods. view the computer images of 10 visuals of the paintings or

the 10 non-art visuals. Participants rated the pictures on (1)

Method “How artistic are these pictures?”; (2) “How esthetic are

these pictures?”; and (3) “How much did you appreciate

Participants and Design. A total of 167 participants the overall beauty of these pictures?” Responses were rated

(Mage ¼ 20.16, SD ¼ 1.21, 58.2% female) from a public on a 7-point scale (1 ¼ not at all to 7 ¼ very much). The

university in North America participated in the experiment results revealed that participants rated the visuals in the art

in exchange for partial course credit. Participants were ran- condition as significantly more artistic than the visuals in

domly assigned to one of four experimental conditions of a the control condition (M ¼ 6.14 vs. 5.11, F(1, 166) ¼

2 (visual stimuli: art vs. non-art) 2 (viewing mode: natu- 28.51, p < .001, gp2 ¼ 0.15). However, they rated the art

ral vs. analytical) between-subjects design. visuals and non-art visuals as being similar in esthetics

Procedure and Measures. Participants were randomly (M ¼ 5.58 vs. 5.45, F(1, 166) ¼ 0.50, p ¼ .48) and overall

assigned to a visual task in which participants viewed 10 beauty (M ¼ 5.44 vs. 5.36, F(1, 166) ¼ 0.15, p ¼ .70).

images (either art or non-art visual images) on a desktop

computer. In the art conditions, participants saw images of Results and Discussion

10 well-known paintings (e.g., Water Lilies and Japanese First, an ANOVA with interest in luxury brands as the

Bridge by Claude Monet and The Starry Night by Vincent dependent measure revealed a significant interaction be-

van Gogh). Each of the images appeared in the center of a tween the visual type (art vs. non-art) and viewing mode

21-inch desktop screen with a full-screen display. (natural vs. analytical), F(1, 163) ¼ 5.31, p ¼ .022, gp2 ¼

Participants could view each image for as long as they 0.032). There was no main effect of the visual type (F(1,

wished and then click to see the next image. In the non-art 163) ¼ 0.56, p ¼ .45, gp2 ¼ 0.003) or main effect of the

control conditions, 10 photographs included matching col- viewing mode (F(1, 163) ¼ 0.37, p ¼ .54, gp2 ¼ 0.002).

ors and topic themes (consistent with Hagtvedt and Patrick To decompose this interaction, we conducted a series of

2008b, see web appendix D for examples of the experimen- pairwise comparisons (figure 4). Specifically, when art was

tal stimuli). viewed naturally, viewing art (Mart ¼ 4.33, SD ¼ 1.97)WANG, XU, AND ZHANG 11

FIGURE 4 experience does not affect consumer interest in shopping,

in general. Rather, the art experience only affects consumer

THE MODERATING ROLE OF STATUS POSITIONING OF response to luxury brands.

LUXURY GOODS (STUDY 2C)

7 STUDY 2C: ART REDUCES INTEREST IN

Luxury Sneakers Evaluaon

Non-Art

6 Art LUXURY ONLY WHEN THE LUXURY

PRODUCT IS POSITIONED AS A STATUS

5

SYMBOL

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jcr/ucac016/6569087 by guest on 28 June 2022

4

In study 2c, we examine yet another boundary condition

3 of the effect. Based on our conceptualization, enhanced

2 self-transcendence (caused by experiencing art) reduces

consumers’ status-seeking motives, which then leads to re-

1

duced desire for luxury goods. One important assumption

Status Posioning Arsc Posioning

underlying this line of reasoning is that luxury goods are

primarily perceived as status symbols. Although this as-

sumption seems to be well supported (Wang 2021), luxury

significantly reduced participant interest in luxury brands products are sometimes not positioned as status symbols.

compared with participants viewing non-art visuals (Mnon- Instead, they can be positioned, for example, in terms of

2 their artistry and creativity. When luxury products are posi-

art ¼ 5.18, SD ¼ 1.75, F(1, 163) ¼ 4.58, p ¼ .034, gp ¼

0.027). This result replicated the findings of previous tioned on characteristics other than as a status symbol, the

experiments and supported our hypothesis 1. However, proposed negative effect of the art experience on consumer

when participants were instructed to analyze the technical desire for luxury should diminish. In study 2c, we manipu-

elements of the visuals, viewing art (Mart ¼ 5.14, late the brand positioning of a luxury product (status vs. ar-

SD ¼ 1.62) did not affect participants’ interest in luxury tistic positioning) and assess the moderating role of status

brands compared to viewing the non-art condition (Mnon-art positioning.

¼ 4.71, SD ¼ 1.76, F(1, 163) ¼ 1.23, p ¼ .27, gp2 ¼

0.008). Finally, viewing art naturally (M ¼ 4.33, Method

SD ¼ 1.97) significantly reduced participants’ interest in Participants and Design. A total of 294 undergraduate

luxury brands compared to viewing art analytically students from a large public university in North America

(M ¼ 5.14, SD ¼ 1.62, F(1, 163) ¼ 4.37, p ¼ .038, gp2 ¼ participated in the study in exchange for partial course

0.026). credit. They were randomly assigned to one of four condi-

Next, the parallel analysis was conducted using interest tions in a 2 (visual stimuli: art vs. non-art) 2 (luxury

in non-luxury brands (i.e., mainstream affordable brands) brand positioning: status positioning vs. artistic position-

as the dependent variable. The results showed that there ing) between-subjects design.

was no significant interaction (F(1, 163) ¼ 2.32, p ¼ .13).

There was no significant main effect of the visual type Procedure. As in the prior experimental studies, partic-

(F(1, 163) ¼ 0.03, p ¼ .87), and no significant main effect ipants came to the lab, were seated in individual cubicles,

of the viewing mode (F(1, 163) ¼ 0.06, p ¼ .80). and were told that the study had two unrelated parts.

In sum, study 2b replicated the effect that viewing art Participants first viewed either 10 art or non-art visuals, as

reduces consumer interest in luxury products (hypothesis in study 2b. In the art condition, participants saw images

1). However, when consumers analyzed the technical of 10 well-known paintings (e.g., Water Lilies and

details of the work of art rather than experience it as art per Japanese Bridge by Claude Monet and The Starry Night by

se, the negative impact on interest in luxury goods was Vincent van Gogh, see web appendix D). In the non-art

eliminated. These results support hypothesis 2. control condition, participants viewed 10 photographs with

In this study, participants independently rated their inter- the same colors and topic themes as the paintings. Next,

est in high-end luxury brands and their interest in main- participants moved on to an ostensibly unrelated study and

stream affordable brands, which allowed us to evaluate the evaluated an advertisement for a collection of Gucci

influence of the art experience on both luxury and non- sneakers, based on the cover story of helping the experi-

luxury brands separately. The lack of an effect on partici- menter learn about consumer preferences for luxury prod-

pant interest in non-luxury brands suggests two conclu- ucts. In the status positioning condition, there were three

sions. First, although the art experience decreases posters of Gucci’s “exclusive sneaker collection.” The text

consumer interest in luxury brands, it does not enhance on the posters read “The collection features an exclusive

consumer interest in non-luxury brands. Second, the art and high-end mix of contemporary colors, materials andYou can also read