Is Culture a Golden Barrier Between Human and Chimpanzee?

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

82 Evolutionary Anthropology

ARTICLES

Is Culture a Golden Barrier Between Human and

Chimpanzee?

CHRISTOPHE BOESCH

Culture pervades much of human existence. Its significance to human social quisition of new behavior patterns

interaction and cognitive development has convinced some researchers that the learned from group members, and the

phenomenon and its underlying mechanisms represent a defining criterion for presence of flexible material cul-

humankind. However, care should be taken not to make hasty conclusions in light tures.1–5 Other contributors to this

of the growing number of observations on the cultural abilities of different species, special issue on culture will address

ranging from chimpanzees and orangutans to whales and dolphins. The present these aspects, and I refer interested

review concentrates on wild chimpanzees and shows that they all possess an readers to their contributions.6,7 The

extensive cultural repertoire. In the light of what we know from humans, I evaluate topic I particularly want to address

the importance of social learning leading to acquisition of cultural traits, as well as here is the general attributes that

of collective meaning of communicative traits. Taking into account cross-cultural chimpanzee culture may share with

variations in humans, I argue that the cultural abilities we observe in wild chim- human culture, as a step toward bet-

panzees present a broad level of similarity between the two species. ter understanding of how and to what

degree they differ.

Primatologists first became recep-

Stephen Jay Gould said once that that for some of us it is the main goal tive to the notion of culture in animals

humanity has an unfortunate ten- of life. If, however, we were Bwa pyg- when they observed the invention of

dency to erect “golden barriers” to set mies living in a tropical rainforest or potato-washing behavior by the young

us apart from the rest of the animal Aborigines living in the open plains of macaque, Imo, and saw it acquired by

kingdom. Is culture becoming one of Australia, our material belongings her playmates.8,9 Imo’s actions shook

those golden barriers? For many of us, would be much more limited. This a golden barrier and opened the way

material culture constitutes most of comparison indicates the extreme to examining cultural differences in a

the external world we encounter in variability that exists in human mate- variety of species. Since that time, re-

our daily lives. In the occidental rial culture. However, human cultures search on wild chimpanzees has

world, material culture is so pervasive are not only material, but also include reached the stage where it is now pos-

beliefs, social rules, knowledge, and sible to compare behaviors of differ-

language. As a result of the incredible ent well-known populations living in

complexity of human cultures, we different places throughout the Afri-

praise ourselves as distinct from other can range of this species.1 I will use

Christophe Boesch has studied the chim-

panzees of the Taı̈ National Park, Côte living beings for our uniquely rich and this information to extract the cul-

d’Ivoire, since 1979 and provided precise complex beliefs, thoughts, and knowl- tural attributes that are apparent in

descriptions of the specific hunting tech- chimpanzees.

niques of this population and detailed ac-

edge. Indeed, all humans on earth are

counts of their nut-cracking behavior. He cultural animals, living in societies To compare chimpanzee and hu-

has observed the chimpanzees of Gombe with specific cultural rules and tradi- man cultures, we first need to decide

and Mahale in Tanzania to deepen our

knowledge of cultural differences in this tions that infiltrate all aspects of our what is meant when speaking of cul-

species. Together with Andrew Whiten, life. This fact has been elevated to a ture. Anthropologists have argued

he initiated the chimpanzee culture dogma, making humans the only liv- over this concept since the beginning

project that culminated in a paper on

chimpanzee culture in 1999. He recently ing beings on earth with culture. Cul- of their discipline and agreement re-

launched the first archaeology project on ture frees us from the natural world, mains minimal.10 –12 Many definitions

chimpanzee technology.

E-mail: boesch@eva.mpg.de

whereas all others living animals are include the world “man,” and thereby

mainly influenced by nature. But is exclude any other species a priori and

that dogma really so? make any studies about the emer-

Key words: shared meaning, social learning, Recently this golden barrier has gence of cultural phenomenon in any

comparison, group difference, cultural repertoire

come under question, as increasing other species impossible or illegiti-

evidence from primates, birds, and mate. However, culture is not the ex-

Evolutionary Anthropology 12:82–91 (2003) even marine mammals supports the clusive property of anthropologists;

DOI 10.1002/evan.10106

Published online in Wiley InterScience existence of repeated population dif- other fields of science have, in the

(www.interscience.wiley.com). ferences in behavior patterns, the ac- meantime, started to examine variousARTICLES Evolutionary Anthropology 83

aspects of culture. For example, psy- viduals.1 Thus, we should be aware She proposed that some of them were

chologists have concentrated on un- throughout this discussion that one cultural in origin. The most conspicu-

derstanding the different learning thing we are certain about with re- ous one was nut cracking, which is

processes involved in the cultural spect to chimpanzee culture is that we absent in the Gombe chimpanzees, in

transmission of information.13–16 At strongly underestimate its breadth spite of the presence of oil-palm nuts.

the same time, biologists have started and complexity. Observations of this behavior were

to show a great interest in culture evo- first reported in the 1840s in Liberian

lution as a much more rapid alterna- chimpanzees.23 With increasing ob-

CULTURAL DIVERSITY AND

tive to genetic evolution, because of its servation time, the discovery of addi-

independence from reproductive CREATIVITY tional behavior differences between

events.17–20 When Imo, a young female Japa- chimpanzee populations made it fea-

Despite the different approaches nese macaque, introduced potato sible to begin drawing up charts of

among the three disciplines, a high washing into her population, it was a cultural variations. McGrew,24 in his

level of consensus can be found on breakthrough. Nevertheless, it might book Chimpanzee Material Cultures,

some basic concepts: First, culture is well seem a bit simple to qualify as a listed nineteen different kinds of tool

learned from group members; it is not culture. Human cultures are charac- use that varied in their expression in

transmitted genetically nor does it different communities, while Mike

represent simply an adaptation to par- Tomasello and I25 listed twenty-five

ticular ecological conditions. Because behavior patterns as potential cultural

it is transmitted socially, cultural In the last attempt to elements in wild chimpanzee popula-

practices have the potential to change tions. In the last attempt to categorize

rapidly if a new social model becomes categorize chimpanzee chimpanzee cultural variation, no less

available. Second, culture is a distinc- cultural variation, no less than thirty-nine behavior patterns

tive collective practice. This rather were proposed as cultural variants, in-

vague formulation implies that a cul- than thirty-nine behavior cluding various forms of tool use,

ture observed in one group or society patterns were proposed grooming techniques, and courtship

is distinct, so that we can actually gambits.1,3 This cultural richness in

know the origin of individuals by their

as cultural variants, chimpanzee far exceeds anything

socially learned practices. Third, an- including various forms known for any other species of animal

thropologists tend to speak of a sym- except humans. However, new analy-

bolic system to express the fact that

of tool use, grooming ses on other species such as the oran-

culture is based on shared meanings techniques, and gutan26 are under way, stressing the

between members of the same group courtship gambits. This possibility that rich cultures might be

or society. more prevalent than previously was

I shall investigate if chimpanzee cultural richness in thought.

cultural abilities share with humans chimpanzee far Anthropologists present culture as

the fact that they are diverse, innova- releasing individuals to some extent

tive, and group-specific. Then I shall exceeds anything from the ecological constraints under

analyze on what mechanism cultural known for any other which they live. The invention of nut

learning is based and see if the collec- cracking in chimpanzees illustrates

tive practice includes shared mean- species of animal this effect with respect to diet. Nut

ings. Finally I shall discuss aspects of except humans. cracking accounted for 33% of the to-

possible cultural evolution in chim- tal feeding time of the chimpanzees

panzees. This might deepen our un- during certain seasons at Bossou27

derstanding of culture in different and more than 40% of it at Taı̈, sup-

species. Before we start, one point plying the nutcrackers with more than

terized by a large number of different

needs to be kept in mind. Our knowl- 3,000 calories per day during the four

cultural traits in a variety of domains

edge of chimpanzee behavior is very months when nuts were available.28

(social, technical or symbolic). Imo

fragmented compared to our knowl- Further, twenty-two of the thirty-nine

edge of human behaviors. Long-term might well be a groundbreaker, but cultural variants found for chimpan-

studies on wild chimpanzees started her two inventions fall short of such zees relate to feeding, illustrating how

only in the early 1960s.21,22 Since the cultural breadth. However, culture is cultural their diet is. More specifically,

1960s, field work has increased, but a collective practice, and we should Taı̈ chimpanzees use twenty types of

only a few chimpanzee populations not expect one single individual to tools regularly, while Budongo and

have been studied for more than one create it. How rich are cultures in Kibale chimpanzees on Uganda use

decade. In a recent survey of culture chimpanzees? Are they able to inno- only six and five, respectively. Not

in chimpanzees we found only seven vate? only does this larger repertoire of tool

chimpanzee populations on which As early as 1973, Jane Goodall listed use in Taı̈ allow the chimpanzees to

enough detailed observations existed thirteen differences in tool use as well gain access to many more insect prod-

to answer simple questions such as as eight differences in social behav- ucts (larvae, grubs, and honey) than

whether a behavior pattern was iors between the Gombe chimpanzees do Budondo and Kibale chimpanzees,

present and, if so, in how many indi- and other chimpanzee populations. but it suggests an underlying “core84 Evolutionary Anthropology ARTICLES

cultural orientation” toward technol- precise for the acquisition of some of with the help of naturally occurring

ogy in Taı̈ chimpanzees, which is the innovations. hammers, which include stones or

manifested in a disposition to inno- branches, and anvils that are normally

vate and to learn socially about a va- CULTURAL LEARNING surface roots. Chimpanzees as young

riety of forms of tool use.2 as two years old show a strong interest

Cultural creativity in chimpanzees One defining feature of culture in in manipulating hammers and in

is documented by innovations. On the human societies is the acquisition of learning to open nuts. In addition,

January 7, 1990, the Bossou chimpan- cultural traits in naı̈ve individuals mothers share the nuts they open with

through social learning. Learning their infants for many years, thus cre-

zees, which have been under study

abilities have been subject to many ating a situation in which learning at-

since 1979, were observed pestle-

studies with captive individuals.32–36 tempts and food sharing occur simul-

pounding the top of an oil-palm tree

As expected, such studies show that taneously. The learning of nut

to eat the apical bud for the first time.

chimpanzees and other animals use cracking seems to proceed through

In the following three years, this be-

different mechanisms, both individ- three distinct phases. First, the young-

havior spread to eight of the sixteen

ual and social, to learn different be- sters make unsuccessful attempts by

individuals of the group.29 On March

7, 1999, I first observed an adult fe- hitting the nuts. Typically, during this

male in the Taı̈ forest chewing the pith phase, youngsters do not understand

of adult leaves from young oil-palm the relationship between the various

trees, whereas such behavior had not components of the task and make mis-

been observed in the previous nine- . . . studies show that takes such as selecting an incorrect

teen years of study. In the following hammer, such as a hand or another

chimpanzees and other nut, or not placing the nut on the an-

days, I saw this behavior performed

by four more individuals. animals use different vil. The second phase is reached at the

age of three years when they under-

Some observations emphasize that mechanisms, both stand relationships between the ele-

innovation is a regular event in wild

chimpanzees. Between 1988 and individual and social, to ments. Then they crack nuts only

when all three elements are present,

1991, I saw Taı̈ chimpanzees use tools learn different behaviors. but they lack the muscular strength to

in seven new ways.30 In the subse-

quent four-year period, from 1992 to

Since nobody proposes open the nuts. The third phase starts

that one individual when they have gained the muscula-

1996, I observed eight new behaviors,

ture necessary to crack the nuts open.

six of them related to tool use. By learns all the behavior Through practice, progress is quite

“new,” I mean a behavior never ob-

patterns in his repertoire rapid, and youngsters achieve 42% of

served during the course of the study

the adult efficiency for the Coula nuts

and for which simple ecological expla- with a single within two seasons.

nations, such as using a tool for a new

food source that was available for the mechanism, we are still What is the role of social learning

during this period? If social learning

first time, could be excluded. In other left with the question of is at work, the nut-cracking attempts

words, the chimpanzees of this com-

munity invented, on average, two new

what learning of the youngsters should be similar to

the behavior they have observed in ex-

behavior patterns per year. mechanisms wild pert nutcrackers. If, however, social

Thus, chimpanzees have the ability chimpanzees use for learning is absent, youngsters would

to regularly invent new behavioral be expected to use a wider variety of

patterns, many of which increase acquiring cultural traits. behavioral techniques than expert nut

their freedom from environmental crackers. To distinguish between

constraints. In addition, we see that these mechanisms, I compared the be-

many of the cultural variants they use havior of young chimpanzees in the

help to shape their environment. Hu- haviors. Since nobody proposes that Taı̈ forest with that of naı̈ve captive

mans also have this ability, although one individual learns all the behavior chimpanzees that were provided with

societies vary greatly in this tendency patterns in his repertoire with a single the three elements of the task—nuts,

to shape their environment through mechanism, we are still left with the hammers, and anvils.40

culture.31 This relatively high rate of question of what learning mecha- Despite the fact that the ecological

invention begs the question of why nisms wild chimpanzees use for ac- conditions in the tropical rainforest

cultural invention seems so rare in quiring cultural traits. Surprisingly are much richer than those of a zoo,

chimpanzees. This represents the enough, up to now only one cultural the zoo chimpanzees used twice as

“cultural paradox” whereby some cul- trait, nut-cracking behavior, has been many behaviors (fourteen in total) to

tures are very stable when they could subject to such study.28,37–39 open the nuts as the Taı̈ chimpanzees

potentially be rapidly changing.25 Two The main nut species cracked in the did. Interestingly, some of the meth-

explanations have been proposed: ei- Taı̈ forest, Coula edulis, is an impor- ods seen in zoo chimpanzees were

ther group conservatism prevents the tant food source during the four- similar in form to behaviors used by

introduction of a new variant, or the month dry season between December Taı̈ chimpanzees in contexts outside

social learning mechanism is too im- and March.28 The nuts are cracked of nut cracking, such as throwing theARTICLES Evolutionary Anthropology 85

hammer on the nut (which Taı̈ chim- risks of losing it to another chimpan- formance always improved, some-

panzees did at leopards), rubbing the zee. In this way, the mothers provide times greatly.40

nuts (which Taı̈ chimpanzees did with their offspring with the opportunity to Finally, by active teaching, mothers

hairy fruits), or stabbing the nuts with learn what a good nut and a good helped offspring solve technical diffi-

a stick (which Taı̈ chimpanzees did at hammer look like, and give them the culties that they were unable to over-

leopards). We argue that Taı̈ young- chance to practice. Stimulations were come on their own. In two instances,

sters never used these methods in this performed most frequently for three- mothers noticed the offspring’s spe-

context because they never saw them year olds that had started to use a cific technical problems and were

used by experts when cracking nuts. hammer, occurring seven times per seen to make a clear demonstration of

In other words, a strong social canal- hour (Fig. 1). Second, facilitation was how to solve them. Both were per-

ization is at work in Taı̈ that limits the seen for offspring trying on their own formed with offspring that had al-

individual learning attempts to those to open nuts. In this case, mothers ready successfully opened nuts but, in

methods observed in adults. The nut- provided better hammers or intact these cases, either did not notice the

cracking movements seen in expert in- nuts they had collected. Facilitation, problem or could not find a solution.40

dividuals are copied by all youngsters, When I first published these exam-

and the variations observed concern ples of teaching, the main criticism

mainly the object to be used as a ham- was that such cases were too rare,

mer. Thus, for nut-cracking behavior, given that chimpanzees have the abil-

social learning prevails as an impor-

. . . a strong social ity to teach.43,47 This critique assumes

tant part of the learning process. canalization is at work in that active teaching is the best way to

Because youngsters were so atten- Taı̈ that limits the acquire a cultural behavior, and there-

tive to what their mothers did, we fore should be used frequently. Is this

might also expect mothers to guide individual learning assumption correct? The few studies

their offspring’s attempts. In humans, attempts to those that have examined the acquisition of

such actions by parents or older group cultural behaviors in human societies

members is proposed to be of central methods observed in show that many transmission mecha-

importance for the transfer of knowl- adults. The nut-cracking nisms are at work. For example, ob-

edge and skills between generations servational learning is the primary

that is necessary for cultural transmis- movements seen in mechanism used by apprentices to

sion.41– 43 Such different pedagogical expert individuals are learn skilled and complex weaving

actions are often presented as a “scaf- techniques in different South Ameri-

folding process”44 whereby the teach-

copied by all can, African, and Arabic societ-

er’s selective interventions provide youngsters, and the ies.45,48,49 Observational learning is

support to learners, extending their supplemented by facilitation and

skills to allow the successful accom-

variations observed stimulation from an expert during the

plishment of a task not otherwise pos- concern mainly the later phases of the acquisition pro-

sible. This allows a learner to produce object to be used as a cess. The same is true when students

new skill components that are often are learning to become sushi masters

understood but yet not performed. hammer. Thus, for nut- in Japanese cuisine.50 For some tasks,

This includes not just teaching but all cracking behavior, the type of learning mechanism used

the ways parents use to stimulate and depends in part on the desired result.

facilitate their offspring’s attempts at social learning prevails In weaving, for example, learning by

a given task. Teaching is considered to as an important part of observation and shaping by scaffold-

be the most elaborate form of peda- ing prevail when maintenance of tra-

gogy, but is often less frequently used the learning process. ditional methods is important. How-

in humans for learning a task than ever, when innovation is valued,

attention-fixing or motivating.45,46 learning by trial and error domi-

At Taı̈, chimpanzee mothers rely on nates.49 Therefore, in the case of hu-

many forms of pedagogy to help their like stimulation, was more frequently man cultural traditions, active teach-

offspring’s acquisition of the nut- performed for infants that had ac- ing seems less essential for learning

cracking technique.40 We observed quired some of the technique. While some cultural techniques than often is

three different ways by which moth- stimulations occurred most fre- assumed.

ers assist their infants’ acquisition of quently for three-year old infants, fa- In the case of nut cracking, cultural

the task. First, mothers stimulated cilitations started with four- to five- learning is based on both social learn-

their offsprings’ attempts at nut crack- year olds and occurred on average ing by the infants and pedagogical in-

ing by leaving their hammers and once every seven minutes, with a peak terventions by the mothers. These

some intact nuts behind on the anvil at more than one instance per minute pedagogic interventions are frequent

while they searched for more nuts un- for eight-year old individuals (Fig. 1). (on average twelve times per hour for

der the trees. Only mothers with The mothers’ acts were adjusted to the nut cracking) and result in specific as-

young infants were seen to do so, as level of skill attained by their infants. pects of this technique being brought

good hammers are rare in the forest The offspring always used the ham- to the attention of the offspring. Con-

and leaving one behind increases the mers left, and their nut-cracking per- sequently, the learning of cultural be-86 Evolutionary Anthropology ARTICLES

meaning within a particular commu-

nity. Sexually active females will

present to a leaf-clipper in Mahale,

whereas in Bossou youngsters will at-

tack or pursue the leaf-clipper with a

play face. Individuals in Mahale have

never been observed to answer with a

play face to a leaf clip. Similarly, a

female from Taı̈ has never responded

sexually to leaf clipping. Rather,

young males from Taı̈ attract females

by knuckle-knocking discreetly and

repeatedly on a small tree trunk (Ta-

ble 1). Females respond to this behav-

ior by sexual presentation. It can even

happen that another female may

present to the knuckle-knocker, de-

spite the fact that he was not looking

toward her. Even sexually immature

youngsters may react by sexually pre-

Figure 1. Maternal scaffolding actions in relation to the infant age when nut cracking in Taı̈ senting to the knuckle-knocker, dem-

chimpanzees. onstrating that they have understood

the meaning. In other words, the

meaning of the behavior is clear by

havior in chimpanzees is surprisingly shared between members of the same itself and independent of the sexual

similar to human learning of some group and is unique to the group. state of the receiver or the gaze of the

cultural tasks. In both species, obser- Take the example of “leaf clip,” a be- emitter.

vational learning is the base; experts havior whereby chimpanzees bite a The meanings of some cultural be-

supplement it with such methods as leaf into pieces to produce a ripping havior rely on arbitrary conventions.

attention-fixing and facilitation. What sound without eating any of the leaf. Nothing in the form of the behavior or

seems specific to cultural learning is In forty years of observation, leaf clip in the noise produced by the leaf clip-

both the social canalization, which re- has never been seen in any of the ping indicates that it could mean play

sults in having naı̈ve individuals prac- Gombe chimpanzees. However, three rather than courtship. The meaning is

tice only what they see in models, and populations of chimpanzees regularly adopted collectively and rests on an

the scaffolding, through stimulation leaf-clip. All males in the Taı̈ forest arbitrary convention shared by group

and facilitation, that assists naı̈ve in- regularly leaf-clip before drumming. members. Thus, shared meaning and

dividuals in mastering specific aspects Among Bossou chimpanzees, leaf clip symbolism go together at this level of

of the task with fewer difficulties. is performed in the context of playing, cultural complexity observed in chim-

Both chimpanzee and human “teach- as a means to enlist a playmate,51 panzees.

ers” appear to understand the skill while Mahale chimpanzees leaf clip as Another example of a socially shared

level reached by naı̈ve individuals and a way to court estrous females.52 Taı̈ meaning concerns the fascination di-

to react properly to it. Care should be chimpanzees have never been ob- rected by all chimpanzees towards ec-

taken before drawing definite conclu- served to leaf-clip in the context of toparasites like ticks and lice. When a

sions on the use of such mechanisms, playing nor in courtship. Similarly, chimpanzee finds one, either on itself or

as more observations are needed Mahale chimpanzees have never been while grooming a group member, he

about the mechanisms used in learn- seen to leaf-clip in the context of play- first manipulates it and then eats it.

ing a variety of cultural techniques in ing nor when drumming (Table 1). However, the way he manipulates it is

both species. While the leaf-clipping sound at- population-specific. At Gombe, chim-

tracts the attention of others in all panzees tear a bunch of four or five

CULTURAL MEANING communities, group members re- leaves from a small branch, carefully

spond differently according to its pile one leaf on top of the other, and

In anthropology, culture is com-

monly viewed as a matter of ideas and

values, a collective cast of mind.10 In TABLE 1. Cultural Meaning of Different Behaviors Within

other words, cultural behaviors have a

Different Chimpanzee Populations

shared meaning within each social

group, and it is this aspect that has Bossou Gombe Mahale Taı̈

been described as being unique to hu- Behavior

man culture. Leaf-clip Play — Courtship Drum ⫹ Rest

However, chimpanzees also possess Meaning

some cultural behaviors that have not Courtship — — Leaf clip Knuckle-knock

Play Leaf-clip — — Ground nest (South Group)

only a form but also a meaning that isARTICLES Evolutionary Anthropology 87

place the parasite on top of the leaves. chimpanzee groups that have individ- the North and South groups that dis-

Then, with the nails of both thumbs, uals transferring between them? tinguish group members by their be-

they squash it and eat it. This behavior Because of the lengthy investment havioral repertoire. Seven behavioral

pattern has been labeled as leaf required to habituate wild chimpan- traits were observed only among

groom.53 At Mahale, chimpanzees were zees to human observers, each project South group members and any plau-

thought to have a similar way of han- has concentrated on a single commu- sible ecological differences were ex-

dling parasite. However, when I visited nity at a time. Recent developments in cluded. Similarly, five behavioral

Mahale in 1999, I compared this behav- the Taı̈ chimpanzee project have led traits distinguished the north group

ior to that seen in Gombe and found it to three neighboring communities be- members from the south.

quite different. Mahale chimpanzees ing observed concurrently.54 To my Let me illustrate some of these dif-

take one single leaf, place the parasite surprise, I noticed some behavior pat- ferences. First, feeding on young

on it, carefully fold the leaf lengthwise terns that differ between the three Haloplegia leaves has been observed in

to cover the parasite, then cut the leaf communities, and several of them all three groups, but the chewing of

with the nail of one thumb so as to were not directly related to ecological mature leaf stems is seen only in the

expose it again. Finally, they take it with differences. Map 1 shows the position South group. Second, South group

their lips and chew it. They may replace of the three groups within the forest chimpanzees use a different tech-

the parasite on the same leaf and repeat nique from the North group to feed on

the procedure a few times. I labeled this grubs extracted by hand from driver-

behavior sequence “leaf fold” to distin- ant nests. Whereas North individuals

guish from the Gombe leaf groom. At Nothing in the form of introduce their arm into the nest mul-

Taı̈, an ectoparasite is placed on the tiple times and almost to the shoulder,

forearm and hit with the tip of the fore- the behavior or in the South individuals introduce their arm

finger until it is smashed. One male re- noise produced by the only once and rarely deeper than the

peated this behavior 350 times! The elbow. Consequently, the South-

communicative function of this behav- leaf clipping indicates group chimpanzees eat many fewer

ior is more limited than that of leaf clip- that it could mean play grubs. Third, they differ in how they

ping, but others obviously understood eat the hard-shelled Strychnos ac-

the function of the behavior, as each

rather than courtship. uleata fruits. The South chimpanzees

time it occurred they reacted by hurry- The meaning is adopted eat the flesh only when it is fresh and

ing over to look intently at what was white, while the North chimpanzees

happening.

collectively and rests on wait for the flesh to be totally decom-

Thus, in chimpanzees, some cul- an arbitrary convention posed and eat only the embedded ker-

tural variants function as signals that shared by group nels. Finally, the North chimpanzees

have acquired collective shared mean- eat large amounts of the winged form

ings based on a behavior independent members. Thus, shared of Thoracotermes termites as they

from any external factors. Interest- meaning and symbolism gather on the aerial part of the

ingly, in the case of leaf clipping, the mounds; South group members to-

relationship between the form of the go together at this level tally neglected them even though they

behavior and its meaning is totally ar- of cultural complexity are present at the same time of the

bitrary and based on a group conven- year.

tion. Thus, a particular behavior can observed in Differences between populations

acquire different meanings in differ- chimpanzees. were also found in communication.

ent populations. Conversely, the same The North group members regularly

meaning may be conveyed with differ- build nests on the ground when rest-

ent behaviors. ing.30 In contrast, South group mem-

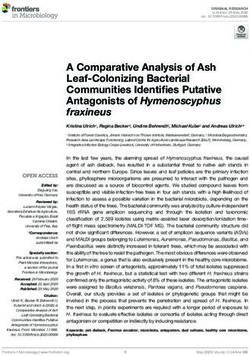

and lists the cultural behaviors that bers build ground nests for totally dif-

distinguish the North from the South ferent purposes. Youngsters build

group. Within a three-year interval, I ground nests as signal to play. Often,

CULTURAL FIDELITY before or during a pause in a play

documented twelve behavior patterns

Often human cultural habits allow session, I observed a youngster build a

that distinguished the two groups. All

close social groups to differentiate ground nest, after which another

three communities share the typical

themselves from their neighbors. This jumped on him, trying to destroy the

traits of the Taı̈ culture, including

is possible only because individuals nest while the first protected it; each

cracking five species of nuts with

transferring between groups, for ex- showed a wide play face. This behav-

ample after a marriage, adopt the new hammers, dipping for ants with short ior has never been observed in the

cultural tradition of the groups into sticks, pounding hard food on tree North group. Remember that Bossou

which they immigrate. The bulk of trunks, leaf clipping in a drumming chimpanzees use leaf clipping as a

our knowledge about chimpanzee cul- context, performing a slow and silent play-start signal, whereas the same

tures comes from comparing social rain dance as rain approaches, and goal is reached in the Taı̈ South group

groups that are hundreds of kilome- squashing parasites with the finger on with building of a ground nest (Table

ters apart. We wonder: Are there cul- the forearm. The map shows that in 1). In addition, South chimpanzees

tural differences between nearby addition subcultures are present in were seen to build a coarse ground88 Evolutionary Anthropology ARTICLES

CULTURAL HISTORY

Archeology classically has been de-

fined as the science documenting hu-

man cultural artifacts. We recently at-

tempted to use the same methodology

to investigate nut cracking, the only

chimpanzee cultural trait to leave a

lasting record. We found that this be-

havior has existed for at least 900

years.56,57 Further excavations will al-

low us to document the exact age of

this behavior, but our early data

clearly suggest that chimpanzee cul-

tural traits could be quite old.

Was a cumulative cultural evolution

process at work during this long pe-

riod of time? By cultural evolution I

am referring to a process under which

a cultural behavior pattern is elabo-

rated by further invention within the

group followed by dissemination, a

process similar to what has occurred

with, for example, hammers in human

cultures.15,25,58 We cannot yet respond

directly to this question. One indirect

indicator of such a process is the com-

plexity of certain cultural sets of be-

havior, as it is unlikely that such be-

haviors would have been invented in

their full complexity by a single indi-

vidual. Is there any indication of a

similar process in chimpanzees?

Three cultural variants in chimpan-

Map 1: Cultural differences between three neighboring chimpanzee communities in the Taı̈

forest. zees might well be the outcome of a

cumulative cultural evolutionary pro-

cess.

nest as a signal to attract sexually ac- curred in the recent past. In the North The first candidate is nut-cracking

tive females. This was seen only once group, transfer of individual females behavior. Many chimpanzee popula-

in twenty years the North group. In happened more than once per year tions open large hard-shelled fruits by

the North, knuckle-knock is used to during a fifteen-year period.28 We do hitting them directly with the hand

attract sexually active females. Thus, not know how this melting into the against tree trunks or roots. This an-

subcultures between communities local subculture is achieved. It could cestral behavior pattern seems to have

within a single area do exist in chim- be either that new immigrant females been further developed in West Afri-

panzees and, like more regional cul- actively try to fit into their new culture can populations by incorporating a

tures, incorporate traits based on or that resident members impose hammer to hit the fruits, thereby mak-

shared meaning. it.25,55 The fact that we saw foreign ing it possible to break harder and

Subcultures between neighboring cultural patterns so rarely in each smaller fruits. Among Bossou chim-

chimpanzee communities persist de- community suggests that this process panzees, two additional developments

spite a regular exchange of individu- takes place very rapidly. occurred, the use of loose stones as

als. New immigrant individuals adopt Thus, subcultures were present that anvils and then the use of a second

the new subculture they encounter distinguish chimpanzee communities stone to increase the stability of the

and seem to lose that of their natal within the Taı̈ forest. This group-related anvil.59

group. It is puzzling that a female variation illustrates the complexity and A similar scenario might be sug-

should switch from an efficient tech- flexibility of chimpanzee cultural be- gested with the second candidate, par-

nique for feeding on ants to a less havior, which helps increase the free- asite manipulation. As mentioned ear-

efficient one. Conformity might be an dom chimpanzees gain from environ- lier, all known chimpanzees show a

aspect that plays a role in chimpanzee ment constraints. Both between- and fascination for ectoparasites and eat

sociality. We have not yet been able to within-region cultures show a tendency them after manipulation. Most chim-

follow the transfer of one individual for communicatory behavioral traits to panzee populations in East Africa

between two of those communities, be more flexible and based on arbitrary have been observed using leaves to re-

but we know that exchanges have oc- shared social meanings. move parasites and some populationsARTICLES Evolutionary Anthropology 89

(at Budongo, Mahale, and Gombe) lows them to shape their environment important in chimpanzee societies.

place the parasites on a leaf to inspect to gain access to important new food Therefore it should not be so surpris-

and squash them before consuming or sources, develop arbitrary signs that ing that teaching has, up to now, been

discarding them.2 This looks like the have shared meaning, and develop observed only in the context of nut

ancestral behavior. Two parallel com- subcultures that distinguish individ- cracking, one of the most complex

plexities have been incorporated. As ual groups from their neighbors. In a tool-use techniques seen in chimpan-

discussed earlier, Mahale chimpan- sense, this all sounds disappointingly zees. Language seems to introduce a

zees not only place the parasite on a similar to what we observe in hu- new dimension to cultural transmis-

leaf, but then fold the leaf and cut it mans. This coincidence might reflect sion mechanisms, as pedagogical in-

with the nail of a thumb. Alterna- the fact that cultures fulfill a special tervention can be performed with in-

tively, Gombe chimpanzees place par- niche in the world and therefore de- dividuals one has not seen and

asites on many leaves previously care- velop in rather similar ways when demonstrations can be performed out

fully piled one on the other. of context.

they develop at all.

A last candidate is well-digging be- Material culture seems to be an-

The proposition that human culture

havior. Chimpanzees living in water- other similarity between humans and

is the only one to rely on one specific

poor habitats (Uganda,60 Senegal61) chimpanzees, as both species are the

social learning mechanism43 is con-

have been seen to dig the soil in dried only ones in which all known popula-

tradicted by the fact that in chimpan-

water beds to gain access to water. tions commonly use different and

This behavioral pattern could be the zees social learning strongly affects multiple tools.28 It is in this domain

ancestral form, which was then fur- more than in any other that anthro-

ther developed to incorporate well pologists have claimed that human

digging during wetter periods, either culture frees us from Mother Nature.

near running water or near algae- . . . the flexibility of the However, this benefit functions in

choked water, perhaps to filter para- chimpanzees’ culture chimpanzee societies as well as hu-

sites or dirt. A final development in man ones. The invention of nut-crack-

this behavior is the incorporation of allows them to shape ing behavior transforms a forest hab-

leaf-sponges to extract water from their environment to itat into a green paradise for months,

deeper wells by chimpanzees in Sem- with energetic food now available in

liki, Uganda.60 A third of the wells had gain access to large supply. In both species, consid-

sponges that chimpanzees used, important new food erable benefits can be attained with

drinking the water from the little limited and simple tools.24,63 In hu-

holes. Gombe chimpanzees have fre-

sources, develop mans, however, the more adverse the

quently been observed to leaf-sponge arbitrary signs that have environment is, the more important

water directly from streams.2 material culture becomes. All well-

These three examples illustrate how

shared meaning, and studied chimpanzee populations live

cumulative cultural evolution could develop subcultures that in tropical forested habitats, where

work. Combined with the creativity distinguish individual the ecological conditions provide

observed in chimpanzees, it suggests them with a warm climate and good

that cultural evolution might exist in groups from their feeding conditions, conditions that do

this species. One paradox of cultural neighbors. not require a large material culture.

evolution is that it potentially is very If we look at what has been pro-

rapid, yet seems to be rather slow in posed as culture in other animal spe-

traditional societies.25,55 As long as so- cies, one striking fact emerges. In

cial and ecological conditions remain most species, very few cultural behav-

the acquisition of nut-cracking behav-

stable, cultural evolution might remain ior patterns have been described. For

ior. Teaching seems to be more com-

very slow because there is little need to example, the Californian sea-otter

mon in some human societies than in

alter the environment. This seems to be population differs from other popula-

others45; such variability has not yet

the case in the chimpanzee populations tions only by using stones to open oys-

been found in chimpanzees. However,

that have been studied. ters.17 In sperm-whale populations,

it might be relevant to consider what

cultural differences are limited to

is being learned and in what social click sounds that distinguish maternal

CHIMPANZEE AND HUMAN context. When the tasks can be ob- groups from each other and remain

CULTURES served and practiced, simpler forms of stable over generations in spite of

What we observe in different chim- scaffolding are observed in human so- changes within the group. Killer-

panzee groups nicely matches our def- cieties,49,62 as is the case in chimpan- whale populations living near land

inition of culture as a set of behaviors zees. When innovation is valued, trial- possess different feeding habits and

learned from group members and not and-error learning dominates, while click calls than do those living in the

genetically transmitted, mainly inde- when maintenance of traditional ways open sea.5 While increased data might

pendent from ecological conditions, is important, learning by observation, demonstrate greater cultural tradi-

and shared between members of some shaping, and especially scaffolding tions in a variety of species, it remains

specific groups. In addition, the flexi- prevails in humans.48,49 Maintenance true that at the current time the pres-

bility of the chimpanzees’ culture al- of traditional methods may rarely be ence of a large repertoire of different90 Evolutionary Anthropology ARTICLES

behavior variants is apparent only in Parks for supporting the Taı̈ chimpan- evolutionary process. Chicago: University of Chi-

cago Press.

great apes. In the orangutan, the num- zee projects all these years, and espe-

19 Maynard-Smith J, Szathmary E. 1995. The

ber of possible cultural behavioral cially the direction of the Taı̈ National major transitions in evolution. Oxford: Freeman.

patterns has recently been reported to Park, the Centre Suisse de Recherches 20 Wilson EO. 1998. Consilience: the unity of

increase.26 In this species, the use of Scientifiques and the Centre de Re- knowledge. London: Abacus.

tools to extract Neesia kernels looks cherche en Écologie. The Swiss Na- 21 Goodall J. 1963. Feeding behaviour of wild

chimpanzees: a preliminary report. Symp Zool

extremely similar to what is observed tional Science Foundation and the Soc London 10:39 –48.

for the nut-cracking behavior in chim- Max Planck Society have financially 22 Nishida T. 1968. The social group of wild

panzees, including the fact that a river supported this project. I thank the chimpanzees in the Mahali Mountains. Primates

represents the boundary of the cul- field assistants and students of the Taı̈ 9:167–224.

23 Savage TS, Wyman J. 1843–1844. Observa-

tural behavior.4 This suggests the pos- chimpanzee project for constant help tions on the external characters and habits of

sibility of a broad great-ape founda- in the field. I also thank Hedwige Troglodytes niger, Geoff. and on its organization.

tion for culture. Similarly, data from Boesch, Elainie Madsen, Martha Rob- Boston J Nat Hist 4:362–386.

studies of capuchin monkeys indicate bins, Tara Stoinski, Carel van Schaik, 24 McGrew W. 1992. Chimpanzee material cul-

ture: implications for human evolution. Cam-

multiple behavioral variations.64 The and one anonymous reviewer for bridge: Cambridge University Press.

discussion about animal culture is helpful comments on this paper. 25 Boesch C, Tomasello M. 1998. Chimpanzee

quite recent and more information is and human cultures. Curr Anthropol 39:591–614.

needed on the species concerned be- 26 van Schaik CP, Ancrenaz M, Borgen G, Galdi-

kas B, Knott C, Singleton I, Suzuki A, Utami S,

fore we can understand the entire REFERENCES Merrill M. 2003. Orangutan cultures and the evo-

range of their cultural behavior. Nev- lution of material culture. Science 299:102–105.

ertheless, human cultural products 1 Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew W, Nishida T, 27 Yamakoshi G. 1998. Dietary responses to fruit

Reynolds V, Sugiyama Y, Tutin C, Wrangham R, scarcity of wild chimpanzees at Bossou, Guinea:

have in recent times led to an inflation possible implications for ecological importance

Boesch C. 1999. Cultures in chimpanzee. Nature,

of artifacts that is unequalled in the 399:682–685. of tool use. Am J Phys Anthropol 106:283–295.

animal kingdom. It remains to be seen 2 Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew W, Nishida T, 28 Boesch C, Boesch-Achermann H. 2000. The

whether our acquisition mechanisms Reynolds V, Sugiyama Y, Tutin C, Wrangham R, chimpanzees of the Taı̈ Forest: behavioural ecol-

Boesch C. 2001. Charting cultural variations in ogy and evolution. Oxford: Oxford University

are qualitatively different from those chimpanzee. Behaviour 138:1489 –1525. Press.

of, for example, chimpanzees. 3 Whiten A, Boesch C. 2001. The cultures of 29 Yamakoshi G, Sugiyama Y. 1995. Pestle-

The implications of this emerging chimpanzees. Sci Am 284:48 –55. pounding behavior of wild chimpanzees at

Bossou, Guinea: a newly observed tool-using be-

picture go far beyond chimpanzees 4 van Schaik C, Deaner R, Merrill M. 1999. The

havior. Primates 36:489 –500.

conditions for tool use in primates: implications

alone. Characteristics that chimpan- for the evolution of material culture. J Hum Evol 30 Boesch C. 1995. Innovation in wild chimpan-

zees share with humans support 36:719 –741. zees. Int J Primatol 16:1–16.

strong inferences about the way of life 5 Rendel L, Whitehead H. 2001. Culture in 31 McGrew W. 1987. Tools to get food: the sub-

whales and dolphins. Behav Brain Sci 24:309 – sistents of Tasmanian aborigines and Tanzanian

of our common ancestor five million chimpanzees compared. J Anthropol Res 43:247–

382.

years ago. An exciting prospect arises 6 Whiten A, Horner V, Marshall-Pescini. 2003. 258.

to gain insights into the ancient foun- Cultural panthropology. Evol Anthropol 12:92– 32 Tomasello M, Call J. 1997. Primate cognition.

dations of our extraordinary human 105. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

capacity for culture. The present over- 7 Perry S, Manson JH. 2003. Traditions in mon- 33 Whiten A. 1998. Imitation of the sequential

keys. Evol Anthropol 12:71– 81. structure of actions by chimpanzees (Pan troglo-

view of what we know about chim- 8 Kawai M. 1965. Newly acquired precultural dytes). J Comp Psychol 112:270 –281.

panzee cultures shows that it goes a behavior of the natural troop of Japanese mon- 34 Whiten A, Custance D. 1996. Studies of imi-

long way beyond being simply a set of keys on Koshima islet. Primates 6:1–30. tation in chimpanzees and children. In: Galef B,

9 de Waal F. 2001. The ape and the sushi mas- Heyes C, editors. Social learning in animals: the

behaviors not explained by genetic or roots of culture. New York: Academic Press. p

ter: cultural reflections of a primatologist. New

ecological factors. The similarities York: Basic Books. 291–318.

with what we observe in human 10 Kroeber A, Kluckhohn C. 1952. Culture: a 35 Heyes CM. 1994. Imitation, culture and cog-

critical review of concepts and definitions. Pa- nition. Anim Behav 46:999 –1010.

groups are striking. At this stage, I

pers of the Peabody Museum, Harvard Univer- 36 Byrne R, Russon A. 1998. Learning by imita-

want to propose that these aspects are sity, Vol. 47, no. 1. Cambridge: Peabody Mu- tion: a hierarchical approach. Behav Brain Sci

common attributes of human and seum. 21:667–672.

chimpanzee culture and that they 11 Kuper A. 1999. Culture: An anthropologist 37 Boesch C, Boesch H. 1983. Optimization of

perspective. Boston: Harvard University Press. nut-cracking with natural hammers by wild

probably were part of the repertoire of

12 Barnard A. 2000. History and theory in an- chimpanzees. Behaviour 83:265–286.

our common ancestor. This means thropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University 38 Boesch C, Boesch H. 1984. Mental map in

that they could be as old as five mil- Press. wild chimpanzees: an analysis of hammer trans-

lion years. Much later, language 13 Galef B, Heyes C. 1996. Social learning in ports for nut cracking. Primates 25:160 –170.

animals: the roots of culture. New York: Aca- 39 Inoue-Nakamura N, Matsuzawa T. 1997. De-

would have opened a wide new win- demic Press. velopment of stone tool use by wild chimpanzees

dow, facilitating the development of 14 Segall M, Dasen P, Berry J, Poortinga Y. 1999. (Pan troglodytes). J Comp Psychol 111:159 –173.

cultural traits in the communicative Human behavior in global perspective: an intro- 40 Boesch C. 1991. Teaching in wild chimpan-

and the shared reflective domain, and duction to cross-cultural psychology, 2nd ed. New zees. Anim Behav 41:530 –532.

York: Pergamon Press. 41 Galef B. 1990. Tradition in animals: field ob-

paving the way for all our cultural be- 15 Tomasello M. 1999. The cultural origin of hu- servations and laboratory analyses. In: Bekoff M,

liefs and rituals. man cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Jamieson D, editors. Interpretation and explana-

Press. tion in the study of animal behavior. Boulder:

16 Whiten A. 2000. Primate culture and social Westview Press. p 74 –95.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS learning. Cogn Sci 24:477–508. 42 Heyes CM. 1998. Theory of mind in nonhu-

17 Bonner J. 1980. The evolution of culture in man primates. Behav Brain Sci 21:101–134.

I thank the Ministry of Scientific animals. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 43 Tomasello M, Kruger A, Ratner H. 1993. Cul-

Research and the Ministry of National 18 Boyd R, Richerson P. 1985. Culture and the tural learning. Behav Brain Sci 16:450 –488.ARTICLES Evolutionary Anthropology 91

44 Wood D, Bruner JS, Ross G. 1976. The role of transmission. In: Smuts SS, Cheney DL, Seyfarth son of chimpanzee material culture between

tutoring in problem-solving. J Child Psychol Psy- RM, Wrangham RW, Strusaker TT, editors. Pri- Bossou and Nimba, West Africa. In: Russon A,

chiatry 17:89 –100. mate societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Bard K, Parkers S, editors. Reaching into

45 Rogoff B. 1990. Apprenticeship in thinking: Press. p 462– 474. thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University

cognitive development in social context. Oxford: 53 Goodall J. 1973. Cultural elements in a chim- Press. p 211–232.

Oxford University Press. panzee community. In: Menzel E, editor. Precul- 60 Hunt K, Cleminson A, Latham J, Weiss R,

46 Whiten A, Milner P. 1984. The educational tural primate behaviour, Fourth IPC Symposia Grimmond S. 1999. A partly habituated commu-

experiences of Nigerian infants. In: Valerie CH, Proceedings, vol. 1. Basel: Karger. p 195–249. nity of dry-habitat chimpanzees in the Semliki

editor. Nigerian children: development perspec- 54 Herbinger I, Boesch C, Rothe H. 2001. Terri- Valley Wildlife Reserve, Uganda. Am J Phys An-

tives. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. p 34 – tory characteristics among three neighbouring thropol 28(Suppl):157.

73. chimpanzee communities in the Taı̈ National

61 Galat-Luong A, Galat G. 2000. Chimpanzees

47 Hauser MD. 2000. Wild minds: what animals Park, Ivory Coast. Int J Primatol 32:143–167.

and baboons drink filtrated water. Folia Primatol

really think. New York: Henry Holt. 55 Durham W. 1991. Coevolution: genes, culture 71:258.

48 Greenfield P. 1984. A theory of the teacher in and human diversity. Stanford: Stanford Univer-

the learning activities of everyday life. In: Rogoff sity Press. 62 Rogoff B, Mosier C, Mistry J, Göncü A. 1998.

B, Lave J, editors. Everyday cognition: its devel- Toddler’s guided participation with their caregiv-

56 Mercader J, Panger M, Boesch C. 2002. Exca-

opment in social context. Cambridge: Harvard ers in cultural activity. In: Woodhead M,

vation of a chimpanzee stone tool site in the

University Press. p 117–138. African rainforest. Science 296:1452–1455. Faulkner D, Littleton K, editors. Cultural worlds

49 Greenfield P. 1999. Cultural change and hu- of early childhood. London: Routledge. p 225–

57 Mercader J, Panger M, Boesch C. 2002. A

man development. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev 249.

chimpanzee/human occupation sequence in the

83:37–59. archeological record of Taı̈ Côte d’Ivoire. Ab- 63 Boesch C. 1996. The emergence of cultures

50 Morris M, Peng K. 1994. Culture and cause: stract IPC Congress, Beijing. among wild chimpanzees. In: Runciman W,

American and Chinese attributions for social and 58 Boyd R, Richerson P. 1996. Why culture is Maynard-Smith J, Dunbar R, editors. Evolution

physical events. J Pers Soc Psychol 67:949 –971. common and cultural evolution is rare. In: of social behaviour patterns in primates and

51 Sugiyama Y. 1981. Observations on the pop- Runciman W, Maynard Smith J, Dunbar R, edi- man. London: British Academy. p 251–268.

ulation dynamics and behavior of wild chimpan- tors. Evolution of social behaviour patterns in 64 Fragaszy DM, Perry S. 2003. The biology of

zees of Bossou, Guinea, 1979 –1980. Primates 22: primates and man. London: British Academy. p animal traditions. Cambridge: Cambridge Uni-

435–444. 77–94. versity Press.

52 Nishida T. 1987. Local traditions and cultural 59 Matsuzawa T, Yamakoshi G. 1996. Compari- © 2003 Wiley-Liss, Inc.You can also read