Is Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection (pigeon fever) in horses an emerging disease in western Canada?

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Case Report Rapport de cas

Is Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection (pigeon fever) in horses

an emerging disease in western Canada?

Louise E. Corbeil, Jennifer K. Morrissey, Renaud Léguillette

Abstract — This report describes 5 horses in the southern Alberta region with typical and atypical external

abscessation due to Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (pigeon fever). “Pigeon fever” has recently been diagnosed

in new geographic regions in North America and should be kept as a differential diagnosis by practitioners when

an external or internal abscess is identified in a horse.

Résumé — L’infection par Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (fièvre du pigeon) chez les chevaux est-elle

une maladie émergente dans l’Ouest canadien? Ce rapport décrit cinq chevaux dans la région sud de l’Alberta

atteints d’abcès externes typiques et atypiques causés par Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (fièvre du pigeon). La

«fièvre du pigeon» a récemment été diagnostiquée dans de nouvelles régions géographiques de l’Amérique du Nord

et devrait être conservée comme diagnostic différentiel par les praticiens lorsqu’un abcès externe ou interne est identifié.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Can Vet J 2016;57:1062–1066

C orynebacterium pseudotuberculosis is a Gram-positive,

intracellular rod-shaped facultative anaerobic bacterium.

It is the causative agent of caseous lymphadenitis in sheep and

of external abscesses is aimed at maturation of the abscess and

establishing adequate drainage. Antibiotic treatment is indicated

in cases of internal infection and ulcerative lymphangitis but it

goats and also infects other species including horses. Equine is usually avoided with external abscesses unless drainage cannot

C. pseudotuberculosis isolates are nitrate positive while sheep and be established (2). Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infections

goat isolates are nitrate negative. Infection is thought to occur in the United States have been reported in states not previously

through contact with contaminated soil via skin abrasions or recognized as having endemic disease (4). This case series from

mucous membranes and recent studies support the role of insect southern Alberta describes cases of typical and atypical external

vectors (1). The 3 main clinical manifestations of the disease abscessation with various treatment approaches. All 5 affected

are external abscessation, internal abscessation, and ulcerative horses had no travel history to endemic areas within the United

lymphangitis. External abscesses are the most prevalent and States, suggesting infection occurred from local sources and

commonly develop in the pectoral muscle region, hence the that practitioners should be aware of this potentially emerging

name “pigeon fever.” However, external abscesses may occur disease in Canada.

in a variety of locations including deep intramuscular, axillary,

inguinal, and mammary. Differential diagnosis includes other Case descriptions

bacterial causes of suppurative myositis or internal abscessa- The blood parameters, clinical form, epidemiological and

tion such as Streptococcus equi subspecies equi (2). Definitive laboratory data and treatment of the horses are summarized

diagnosis of infection is made via culture of abscess content. in Table 1.

Serology can be used in conjunction with bacterial culture and

is most useful in cases of internal abscessation (3). Treatment Farm A — 2 cases

Two horses from a herd of 16 on a farm southeast of Calgary

were presented with pectoral swelling in October 2013. The

Moore Equine, Balzac, Alberta (Corbeil, Morissey, Léguillette); first, a 6-year-old Quarter Horse gelding, had pectoral edema

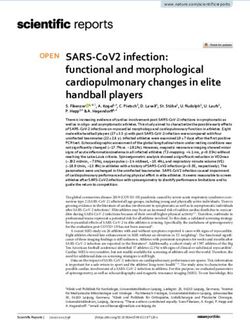

Department of Veterinary Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences, (Figure 1), and after 3 d of applying hot packs to the chest,

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, a 5 cm 3 3 cm abscess located 10 cm deep to the skin was

Alberta (Léguillette). lanced under ultrasound guidance. A penrose drain was placed

Address all correspondence to Dr. Renaud Léguillette; e-mail: and left in place for 2 wk and the abscess was lavaged with

rleguill@ucalgary.ca betadine solution. The exudate cultured positive for C. pseudo-

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. tuberculosis and anti-C-pseudotuberculosis toxin antibody titers

Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the measured via synergistic hemolysin inhibition (SHI) (California

CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory, UC Davis, Davis,

copies or permission to use this material elsewhere. California, USA) was 1:2048 2 wk after initial presentation. At

1062 CVJ / VOL 57 / OCTOBER 2016Table 1. Clinical data for 5 equine cases of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection in Alberta

Total Initial

Geographical Travel history Clinical Hematocrit Leukocytes protein Fibrinogen Positive SHI Antibiotic

area outside Alberta form (L/L) (3 109/L) (g/L) (g/L) culture titer therapy

Farm A

East of Travelled within External 0.28 13.8 67 2 Yes 1:2048 None

High River AB 6 mo abscess:

earlier. Closed Pectoral

CA S E R E P O R T

herd for previous

1.5 mo

Farm A

East of No travel. External 0.30 12.8 69 2 Yes 1:2048 None

High River Closed herd for abscess:

previous 1.5 mo Pectoral

Farm B

Northeast of No history External 0.29 7.5 75 5 Yes 1:512 Trimethoprim/

High River of travel abscess: sulfonamide

Parotid

Farm C

Northwest Brought from External 0.28 9.9 N/A N/A Yes 1:1024 Ceftiofur,

of Calgary lower mainland abscess: Enrofloxacin

of BC 15 mo Mammary

earlier

Farm D South of No history Lymphangitis: N/A N/A N/A N/A Yes N/A Doxycycline

Calgary of travel Distal limb

AB — Alberta; BC — British Columbia; N/A — No results available.

Reference ranges: Hematocrit: 0.32 to 0.52 L/L; Leukocytes: 4.6 to 11.4 3 109/L; Neutrophils: 2.3 to 8.6 3 109/L; Total Protein: 57 to 70 g/L; Fibrinogen: 0.5 to 4.0 g/L.

Trimethoprim sulfonamide (Apotex), Ceftiofur (Excenel), Enrofloxacin (Trutina pharmacy), Doxycycline (Trutina pharmacy).

a 5-week recheck, a small draining tract remained which was flunixin meglumine (Trutina compounding pharmacy, Ancaster,

excised under ultrasound guidance. Repeat serology revealed Ontario), 1.1 mg/kg BW, PO, q24h, for 5 d but clinical signs

a C. pseudotuberculosis titer of 1:4096. The tract was flushed progressed. On recheck physical examination, radiographs, and

on-farm until closure occurred and at an 8-week recheck had endoscopy, a space-occupying soft tissue mass was diagnosed in

healed completely. Recheck antibody titer at 10 wk after pre- the left guttural pouch region. Ultrasound identified an 8-cm

sentation was 1:1024. heterogeneous encapsulated mass axial to the parotid salivary

The second affected horse on Farm A was a 1.5-year-old gland. An ultrasound-guided aspirate of the mass was nega-

Arabian gelding that had a spontaneously draining pectoral tive for S. equi by PCR and its culture revealed light growth of

abscess which healed uneventfully in 2 wk with daily lavage C. pseudotuberculosis. The abscess was lanced using ultrasound

with betadine solution. Culture of the abscess contents yielded guidance and a Foley catheter was placed. The abscess was

a heavy growth of C. pseudotuberculosis and SHI titer (California flushed with 0.1% betadine solution and 10 million IU of

Animal Health and Food Safety Lab) taken at presentation was sodium penicillin was instilled after lavage. The mare was treated

1:2048. At 5-week recheck the tract had healed completely and again with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Apo Sulfatrim;

antibody titer was 1:512. Apotex) and flunixin meglumine (Trutina compounding phar-

Screening antibody titers were measured for the remain- macy), PO. An SHI titer measured on the day of discharge from

ing horses in the herd on Farm A 5 wk after the index cases hospital was1:512. The mare was treated with trimethoprim-

presented. The titers obtained were # 1:8 for 8 horses, 1:16 sulfamethoxazole for an additional 10 d on-farm and complete

for 3 horses, 1:32 for 1 horse, 1:64 for 1 horse, and 1:128 for resolution of the abscess was noted at a 4-week recheck, at which

1 horse. Four horses from Farm A, including the 6-year-old the time antibody titer was 1:128. This horse had no history

gelding (first case), had a history of travel to southern Alberta of travel to the United States. The other 2 horses in contact

earlier that summer but did not travel to the United States. on-farm remained asymptomatic and titers were negative for

both at 1:8.

Farm B — 1 case

A 13-year-old Quarter Horse mare was presented for evalua- Farm C — 1 case

tion of a left-sided retropharyngeal swelling, mild inappetence, A 4-year-old Quarter Horse reining mare living in the Calgary

and a left-sided head tilt. The owner noticed difficulty eating area was evaluated for right-sided mammary gland abscessa-

and lethargy 2 wk after a routine dental examination was tion. In late fall of 2013 while the horse was living in the lower

performed on-farm. An initial examination on-farm revealed mainland area of British Columbia, the owner had noted a

soft tissue swelling in the left parotid area and bilateral sub- small superficial lesion on the ventral midline just cranial to the

mandibular lymph node enlargement. Oral examination was udder that burst and drained spontaneously. Right-sided mam-

unremarkable and blood analysis revealed a mild anemia and mary swelling was noted in May 2014 while living in Calgary

elevated total protein (Table 1). The mare was treated on-farm and the mare was treated with ceftiofur sodium (Excenel;

with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Apo-Sulfatrim; Apotex, Zoetis, Kirkland, Quebec), 2.2 mg/kg BW, IM, q24h, for 8 d.

Calgary, Alberta), 5 mg/kg body weight (BW), PO, q12h, and The swelling failed to resolve and an ultrasound examination

CVJ / VOL 57 / OCTOBER 2016 1063R A P P O R T D E CA S

Figure 1. Swollen pectoral area in a horse diagnosed with Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection (pigeon fever) in Alberta.

revealed diffuse subcutaneous edema and a mixed echogenic doxycycline (Trutina pharmacy), 10 mg/kg BW, PO, q12h,

appearance of the mammary gland without any discrete fluid for 3 wk and thereafter the leg swelling improved significantly.

pockets. Culture of a spontaneously ruptured superficial abscess This horse had no travel history to the United States. The other

revealed C. pseudotuberculosis. A serum sample taken 3 d later horses at the farm had not developed any infection by the time

had a positive SHI titer of 1:1024. The mare was treated with of the writing of this report.

enrofloxacin (Trutina pharmacy), 7.5 mg/kg BW, PO, q24h,

for 12 d and phenylbutazone (Vétoquinol, Lavaltrie Quebec), Discussion

1.1 mg/kg BW, PO, q12h, for 4 d and clinical signs resolved. The disease presentation observed on Farm A is comparable

This horse had no history of travel to the United States. The to that of external C. pseudotuberculosis infection reported in

other horses at the farm have not developed any abscesses to endemic areas in the southwestern United States. The most com-

date. mon areas for external abscesses to develop are in the pectoral

region and ventral abdomen (2). Slightly less commonly affected

Farm D — 1 case sites include the prepuce, mammary gland, triceps, limbs, and

A 14-year-old Quarter Horse gelding used for ranch work was head (2,5). A 25% occurrence of abscesses in secondary loca-

presented with chronic diffuse swelling and superficial absces- tions has been reported (6). Diagnosis of deep intramuscular

sation of the left hind limb. Six months earlier, the horse had abscesses in the limbs and abscesses in the axillary region can

been cast in the stall and sustained a laceration to the dorsal present a diagnostic challenge in horses with a history of chronic

aspect of the left hind metatarsal region. Since then, intermit- severe lameness and no external swelling (5). Less common

tent swelling of the left hind limb had occurred with periodic sites for abscess formation include parotid gland (as was seen

breaking and draining of small abscesses. On presentation for on Farm B), the neck, thorax, guttural pouches, larynx, flanks,

evaluation of chronic limb swelling, the horse was sound and umbilicus, tail, and rectum (2,6).

radiographs of the distal limb did not show significant findings. Hematologic findings in the horses in this study were com-

The horse was treated daily with nitrofurazone (WeCan Sales, parable to those reported previously. In a retrospective study,

Beamsville, Ontario) sweat bandages, and weekly with sodium 40% to 50% of horses with external abscesses showed either

iodide (Vétoquinol, Cambridge, Ontario), 30 mg/kg BW, IV, anemia of chronic disease, neutrophilia, hyperfibrinogenemia,

q24h, for 3 wk. Several days later another abscess spontaneously or hyperproteinemia (6). Similar changes were found in horses

ruptured and culture of a sample from the lesion resulted in with internal disease and are observed more commonly than

isolation of C. pseudotuberculosis. The horse was treated with in horses with external disease (2,6). Interestingly, we only

1064 CVJ / VOL 57 / OCTOBER 2016observed hyperfibrinogenemia in the horse from Farm B, in the MICs for 50% of the time, which may explain the failure

which abscessation occurred in the parotid gland region. This of the first ceftiofur treatment of the horse on Farm C (7). A

horse also had increased total protein at 79 g/L, possibly due single dose of 6.6 mg/kg BW of ceftiofur crystalline free acid

to hyperglobulinemia from prolonged antigenic stimulation. (Excede; Zoetis) does not reach appropriate MIC concentrations

In the 6-year-old gelding from Farm A with the deep pectoral of 2 mg/mL (9). A recent study found no changes in MIC sus-

abscessation, changes in hematologic parameters such as leuko- ceptibility trends in samples submitted to UC Davis from 1996

CA S E R E P O R T

cytosis were more marked compared to those in the 1.5-year-old to 2012 (7); however, further studies are needed to specifically

Arabian cross on Farm A with a more superficial, spontaneously test the MIC susceptibilities of those strains being isolated from

draining abscess. horses in Canada.

Antibody titers were measured using the synergistic hemolysis The incidence of disease on Farms A and B in this study as

inhibition (SHI) test, which measures IgG specific for C. pseu- determined by positive cultures was 13% for Farm A and 33%

dotuberculosis exotoxin (2,3). While culture remains the gold for Farm B. Other documented outbreaks in non-endemic areas

standard for diagnosis, titers can be used in conjunction with within the US have reported a 26% mean prevalence and a range

clinical signs in cases in which a sample for culture cannot be of 3% to 100% (4,10). The present study raises the question of

obtained from an abscess or to support a diagnosis of internal the overall prevalence of C. pseudotuberculosis infection in horses

infection in the absence of external abscesses (2,3). High titers in Alberta, as several practitioners in the southern Alberta area

alone are only indicative of exposure to C. pseudotuberculosis. reported to us treating confirmed positive and suspect positive

A small proportion of horses with external abscessation can be cases throughout the summer and fall of 2013.

seronegative at the time of diagnosis; therefore, titers must be Risk factors for infection from studies in endemic areas in

interpreted in conjunction with clinical signs and hematologic the United States include increased contact with other horses,

changes (3,6). Titers of 1:256 or greater have been suggested as increased outdoor activity, summer pasture, and age, with

strongly indicative of active infection, either external or internal horses 1 to 5 y old being at increased risk of infection (11).

(2), which is consistent with the findings in this case series in Travel history did not appear to be a contributing factor on

which all horses with positive C. pseudotuberculosis cultures from Farms A, B, and D but was likely significant for the horse on

external abscesses had titers of 1:512 or greater at the time of Farm C as clinical signs were first noted by the owner before the

sampling. Screening titers of unaffected, asymptomatic horses horse was moved to Alberta. For Farm C, clinical signs were first

from farms A and B with either direct or fence line contact with noted while the horse was living in the lower mainland area of

positive cases and draining abscesses (Farm A Case 2) ranged British Columbia, and the authors are not aware of any other

from , 1:8 to 1:128, which is consistent with the suggestion confirmed positive cases originating in the lower mainland.

that titers of 1:16 to 1:128 are indicative of exposure (3). The Incubation period is variable and reported as 3 to 4 wk (12), and

use of antimicrobials has been shown to potentially prolong survival of bacteria can be up to 8 mo in manure contaminated

the course of disease in cases of external abscessation (2,6). soil at 37°C (13). Under experimental conditions, increased sur-

Therefore, antibiotic therapy is usually reserved for cases of vival of the bacteria in soil at lower temperatures (4°C compared

internal abscesses and ulcerative lymphangitis. However, horses to 37°C) has been observed (14); however, the effect of below

with external abscesses showing signs of systemic illness such as freezing winter temperatures on the potential for disease in

fever and anorexia or horses with deep intramuscular abscesses future years in Alberta is unknown. Most horses are reported to

draining through healthy tissue may benefit from antimicrobial have a single lifetime episode; however, recurrence or persistence

therapy once drainage has been established (2). of infection for greater than 1 year can occur in some individuals

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing presents a challenge for (6). Recurrent abcessation at the same site is reported in the lit-

laboratories and practitioners as there are no established Clinical erature, often with less than a few wk between apparent abscess

Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines for C. pseu- resolution (6). Horses with recurrent or persistent infections may

dotuberculosis that allow classification of isolates as susceptible act as a source of environmental contamination or infection of

or resistant (7). Since there are no CLSI minimum inhibitory naïve horses in southern Alberta and other Canadian provinces

concentration (MIC) breakpoints for C. pseudotuberculosis, the in the years ahead. Movement of affected horses between western

MICs recently reported for isolates tested at UC Davis can be provinces, across Canada to eastern provinces, and to and from

used as a guide for therapeutic choices (7). For those cases in endemic areas in the United States may contribute to emergence

this study in which a sensitivity was reported by the laboratory, of disease in new areas. In addition, changes in environmental

CLSI guidelines for Staphylococcus were used. Sensitivity results conditions and their effect on insect vectors may play a role in

were therefore not included in this report because extrapola- disease emergence. Insect vectors such as Haematobia irritans

tion of sensitivity patterns across bacterial species has not been (horn fly), Stomoxys calcitrans (stable fly), and Musca domestica

validated (7). Historically, recommended antibiotics have been (house fly) have been implicated as potential mechanical vectors

trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole at 30 mg/kg BW, PO, q12h or for disease (1). Insect vectors may have played a role in disease

procaine penicillin at 20 000 U/kg BW, IM, q12h for external transmission in the cases discussed, especially in Farm B where

abscesses, and rifampin at 2.5 to 5 mg/kg BW, q12h, PO in no horses had travelled to or from the property for 1.5 y. In

combination with ceftiofur (2.5 to 5 mg/kg BW, q12h IV or the United States, the geographic distribution of disease has

IM) for internal abscesses (8). It should be noted that ceftiofur changed significantly in the past 10 y. Sporadic epidemic out-

given only q24h will result in plasma concentrations less than breaks from 2002 to 2007 have been documented in areas with

CVJ / VOL 57 / OCTOBER 2016 1065a historically low prevalence of disease such as Colorado, New Acknowledgments

Mexico, Wyoming, Utah, Oregon and Idaho (10,15). Endemic

The authors thank Drs. Dirk deGraff, Taylor Smith, Kelsey

areas such as California and Texas, which usually have a disease

Brandon, Erin Shields, and Gordon Davis, for sharing their case

prevalence of 5% to 10%, have seen clusters of disease outbreaks

material. We acknowledge funding from the Clinical Practice

and an increase in prevalence of disease (15,16). A recent study

Office, UCVM, for laboratory testing. CVJ

documenting frequency of C. pseudotuberculosis infection in

R A P P O R T D E CA S

horses across the United States over a 10-year period reported References

a significant increase in proportion of culture positive samples 1. Spier SJ, Leutenegger CM, Carroll SP, et al. Use of a real-time polymerase

submitted during 2011 to 2012 and noted positive samples from chain reaction-based fluorogenic 59 nuclease assay to evaluate insect

horses in states not previously recognized as having endemic vectors of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infections in horses. Am

J Vet Res 2004;65:829–834.

disease (4). Disease outbreaks in Canada have also emerged 2. Spier SJ, Whitecomb MB. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. In:

in recent years. In 2010, a large outbreak in the Okanagan Sellon DC, Long M, eds. Equine Infectious Diseases. 2nd ed. St. Louis,

Valley involving at least 350 symptomatic horses was described Missouri: Saunders, 2014:372–379.

3. Jeske JM, Spier SJ, Whitcomb MB, Pusterla N, Gardner IA. Use of

in a survey conducted by the British Columbia Ministry of antibody titers measured via serum synergistic hemolysis inhibition

Agriculture (17). Genetic analysis of isolates from Alberta and testing to predict internal Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection

British Columbia would be useful in shedding further light on in horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013;242:86–92.

4. Kilcoyne I, Spier SJ, Carter CN, Smith JL, Swinford AK, Cohen ND.

epidemiology. Frequency of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection in horses

Historically, outbreaks in non-endemic areas in the US were across the United States during a 10-year period. J Am Vet Med Assoc

usually preceded by high environmental temperatures and 2014;245:309–314.

5. Nogradi N, Spier SJ, Toth B, Vaughan B. Musculoskeletal Corynebac

drought conditions (15). Cases are seen year round in endemic terium pseudotuberculosis infection in horses: 35 cases (1999–2009).

areas; however, a peak seasonal incidence is reliably seen in the J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012;241:771–777.

dry months of late summer and fall in the Southwestern USA 6. Aleman M, Spier SJ, Wilson WD, Doherr M. Corynebacterium pseudo-

tuberculosis infection in horses: 538 cases (1982–1993). J Am Vet Med

(2,15). Definitive environmental factors supporting the spread Assoc 1996;209:804–809.

of infection are yet to be determined (2). Extreme rainfall and 7. Rhodes DM, Magdesian KG, Byrne BA, Kass PH, Edman J, Spier SJ.

flooding occurred in southern Alberta June of 2013, with some Minimum inhibitory concentrations of equine Corynebacterium pseudo-

tuberculosis isolates (1996–2012). J Vet Intern Med 2015;29:327–332.

areas recording over 300 mm of rainfall within 48 h (18). This 8. Spier SJ. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Proc 10th Bain-Fallon

is in contrast to what is reported in the US where historically, Memorial Lectures, 2005:32–43.

outbreaks in non-endemic areas were usually preceded by high 9. Fultz L, Giguère S, Berghaus LJ, Davis JL. Comparative pharmacokinet-

ics of desfuroylceftiofur acetamide after intramuscular versus subcutane-

environmental temperatures and drought (15). Recently, an ous administration of ceftiofur crystalline free acid to adult horses. J Vet

epidemiologic study of an outbreak in Kansas in 2012 reported Pharmacol Ther 2013;36:309–312.

that infections occurred in areas that received relatively higher 10. Hall K, Brian JM, Cunningham W. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis

infections (pigeon fever) in horses in western Colorado: An epidemio-

amounts of precipitation but followed a warm winter and hot logical investigation. J Equine Vet Sci 2001;21:284–286.

dry summer season (19). The authors of this investigation 11. Doherr MG, Carpenter TE, Hanson KM, Wilson WD, Gardner IA.

speculated that some of the infections originate locally from Risk factors associated with Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection

in California horses. Prev Vet Med 1998;35:229–239.

C. pseudotuberculosis present in soil and/or other hosts (19). 12. Doherr MG, Carpenter TE, Wilson WD, Gardner IA. Evaluation of

Heavy rainfall may have precipitated an increase in fly popula- temporal and spatial clustering of horses with Corynebacterium pseudo-

tions and influenced soil microflora, contributing to disease tuberculosis infection. Am J Vet Res 1999;60:284–291.

13. Spier SJ, Toth B, Edman J, et al. Survival of Corynebacterium pseudotu-

emergence in southern Alberta in 2013. berculosis biovar equi in soil. Vet Rec 2012;170:180.

The 5 farms described in this study were not near one another 14. Augustine JL, Renshaw HW. Survival of Corynebacterium pseudotuber-

and infection arising through local changes in soil bacterial culosis in axenic purulent exudate on common barnyard fomites. Am J

Vet Res 1986;47:713–715.

populations seems likely. 15. Spier SJ. Clinical Commentary — Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis

Present recommendations for disease prevention and con- infection in horses: An emerging disease associated with climate change?

trol include implementing insect control measures, efficient Equine Vet Ed 2008;20:7–39.

16. Szonyi B, Swinford A, Clavijo A, Ivanek R. Re-emergence of pigeon

manure removal, minimizing environmental contamination fever (Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis) infection in Texas horses:

with purulent exudates, and proper disposal of contaminated Epidemiologic investigation of laboratory-diagnosed cases. J Equine

bedding (2,11,13). There is no equine vaccine available. A Vet Sci 2014;34:281–287.

17. Britton A, DeWith N. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis in horses in

licensed vaccine exists for sheep, but its safety and efficacy have British Columbia. Abbotsford: Abbotsford Agricultural Center, 2011.

not been evaluated in horses (2,20). A 2010 pilot study in mice 18. Climate Trends and Variations Bulletin: Government of Canada, 2013.

was conducted with an equine bacterin toxoid in which vacci- 19. Boysen C, Davis EG, Beard LA, Lubbers BV, Raghavan RK.

Bayesian geostatistical analysis and ecoclimatic determinants of Cory

nated mice demonstrated significant protection from challenge nebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection among horses. PLoS One

infection (21). 2015;10:e0140666.

The cases described in this report show various clinical pre- 20. Piontkowski MD, Shivvers DW. Evaluation of a commercially available

vaccine against Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis for use in sheep. J Am

sentations and raise the question of prevalence of C. pseudotu- Vet Med Assoc 1998;212:1765–1768.

berculosis in Alberta. The role of climate changes as they relate 21. Gorman JK, Gabriel M, MacLachlan NJ, Nieto N, Foley J, Spier S. Pilot

to disease prevalence and to the survival of potential insect immunization of mice infected with an equine strain of Corynebacterium

pseudotuberculosis. Vet Ther 2010;11:E1–8.

vectors is yet to be fully described, and continued monitoring

and epidemiologic investigations are warranted.

1066 CVJ / VOL 57 / OCTOBER 2016You can also read