How the Shift to Individualize Supports Gets Stuck and The First Step Out of Gridlock

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES VOLUME 49, NUMBER 5: 383–387 | OCTOBER 2011

How the Shift to Individualize Supports Gets Stuck and The First

Step Out of Gridlock

Hanns Meissner

DOI: 10.1352/1934-9556-49.5.383

Many mature and successful service providers decade—but the investments of state systems and

continue to find their identity in the heritage of the efforts of most service providers remain centered

moving people with developmental disabilities out in programs designed to place and manage people

of public institutions. Significant achievements with developmental disabilities in suitable groups.

such as providing residential alternatives to large Facilities and funding streams continue to dominate

facilities do not immune providers from criticism despite policy commitments to individualization.

emerging from a growing demand for individualized Frustration and the temptation to cynicism grow as

supports. The Individualized Supports Think Tank, advocates experience little movement toward what

a group of self-advocates, parents, and service they understand as individualized services. Service

providers convened by the Self-Advocacy Associ- providers continue to report little demand for change

ation of New York State (2007) expressed this (‘‘Our consumers and their families are highly

demand: satisfied with current services’’) and complain of a

thicket of fiscal and regulatory obstacles that

We define individualized supports as an array of supports,

services and resources that are person-centered, based on the

entangle their steps toward individualization. Policy

unique interests and needs of the person, afford the person as changes, strategic plan objectives, exhortation,

much control over their supports as they desire, and are training courses, and financial incentives have not

adaptable as the person’s life changes. This means that supports shifted the prevailing pattern. The move toward

are created around an individual’s distinct vision for their [sic] individualized services is stuck.

life rather than created around a facility or funding stream.

The roots of this gridlock lie in beliefs and

From this perspective, some would claim that assumptions about people with developmental dis-

the most dominant forms of accomplishments of abilities that are embodied in and reinforced by the

the era of deinstitutionalization look like mini- culture of the service system. The individualization

institutions that offer few and constricted options. that growing numbers of people with developmental

These options tend to consign people to full time disabilities and their families and allies call for is not

clienthood, where they are excessively controlled superficial and transactional, but deep and transfor-

by caregivers and are prevented from fully partic- mational. It is not a matter of dispassionately working

ipating in community life. As the full responsibility on redesigning structures, independent of the rela-

for the quality of people’s lives continues to be tionships, practices, emotions, and mental models of

delegated to service providers by families, commu- the managers, professionals, families, and people with

nities, and generic services, the growing demand for developmental disabilities creating the change. It is a

long-term supports challenges the sustainability of matter of opening up space for innovation in a

developmental disability systems. culture that includes those who want to make room

The argument that typical service providers are for new arrangements by surfacing their assumptions

caught in a pattern of ‘‘strengths becoming weak- about what is possible for people with intellectual

nesses’’ in the face of shifting service expectations disability both in terms of their capacity for an

becomes more salient as sophisticated service systems inclusive life and options to support new outcomes.

experience great difficulty in implementing individ- One good move when stuck is to find a way to

ualized supports. There have been modifications in describe the mental models in play. This process

language and procedure—most everything has been begins with engaging in a dialog about the various

labeled as ‘‘person-centered’’ for more than a beliefs and assumptions that shape perception of

’American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 383INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES VOLUME 49, NUMBER 5: 383–387 | OCTOBER 2011

Perspective: Individualizing supports H. Meissner

people with developmental disabilities themselves, adopting individualized services is like replacing

as the following example of contrasting mental one’s mobile phone with a smartphone. The old is

models illustrates. If we see people with develop- discarded; the new adopted. Change is a matter of

mental disabilities as fundamentally vulnerable and marketing a new product by convincing people that

incapable, the role of service providers is to take the gain outweighs the pain of change or that the

care, protect, and decide for people and the role of cost of resisting the command to change is higher

service systems is to create rules, incentives, and than the cost of changing. A more powerful image

mechanisms of inspection and enforcement that views the field of developmental disabilities servic-

assure safety and adequate care. On the other hand, es as being like a natural ecosystem, with many

if we see people with developmental disabilities as different life forms existing and evolving simulta-

capable of contributing meaningfully to community neously. Some are dying out as their niche shrinks,

life, the service provider is one partner in others mobilize most of the available resources as

discovering and offering the individualized sup- they pass through their adaptive peak, still others

ports, interest-based opportunities, and safeguards are experiments of life that make the most of ca-

that enhance participation, satisfaction, and resil- pacities unused by the dominant forms or released

ience. The service system holds responsibility for by what is dying.

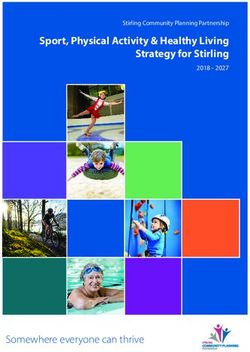

investing public funds that are sufficient and Table 1 sketches a map of the developmental

flexible to sustain individualized supports, develop- disabilities ecosystem that offers people who want

ing an adequate supply of capable and ethical to develop individualized services a way to locate

service providers, and offering an additional level of their efforts and consider the multiple dimensions

safeguards to people’s autonomy and community of necessary change. It identifies a succession of

membership. four different forms of service, all of which are

currently sharing the field.

These distinct mental models justify profound-

Though the legitimacy of institutional care is

ly different service systems and shape almost

declining and its sustainability is in grave doubt,

incommensurable understandings of key ideas like

the transfer of institutional structures, practices,

person-centered work and individualized services. and assumptions into many local service settings

Trying to simply overlay structures and practices makes it still the dominant form. Managed care is

intended to offer individualized support for com- also strong and, in most places, integrative supports

munity contribution on a system shaped by beliefs and community supports are just emerging at the

that persons with intellectual disability are exclu- innovative edges of the field.

sively vulnerable and incompetent will get mired in Institutional care is system-centered, with

more of the same. So will change strategies based provider organizations and state systems delegated

on the notion that shifting paradigms of under- full responsibility for meeting every officially

standing is as simple as jumping from one state to defined need in service models for diagnostic

another on command. What is necessary is the kind groups and plans for individuals designed and

of purposeful listening relationships that encourage directed by professional experts. People with dis-

awareness and suspension of the assumptions and abilities and their families are passive clients. The

beliefs that reinforce gridlock and the exploration system is hierarchical and operates through com-

of an understanding more aligned with the purpose mand and control, reflecting the dynamics of

of developing individualized supports. Such rela- power-over relationships. Its infrastructure is found-

tionships become a springboard for prototyping new ed on legal requirements that are specified and

ways to partner and provide supports that can form monitored in detail with a strong aversion to any

and flourish if there is a supporting environment potential risk. These requirements and the compli-

(Scharmer, 2009; Mount & VanEck, in press). ance sensibility that pervades institutional care

Not only do mental models shape our sense arise in reaction to the abuse and neglect that

of what is desirable and possible for people with people with developmental disabilities are vulner-

developmental disabilities, we also are strongly able to and the possibilities for real or perceived

influenced by the way we make sense of change. misuse of public funds. Decision-makers are sensi-

Some understand change as the straightforward tized to deficiencies in people with developmental

replacement of one way of doing things by an- disabilities, service providers, and ordinary citizens.

other better one. Given this definition of change, The system manages very high levels of detail

384 ’American Association on Intellectual and Developmental DisabilitiesINTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES VOLUME 49, NUMBER 5: 383–387 | OCTOBER 2011

Perspective: Individualizing supports H. Meissner

Table 1 Evolution of Developmental Disabilities Services

Organizing citizen-

centered principle System-centered Outcome-centered Person-centered Citizen-centered

Individual resource- Expert–patient Provider–consumer Facilitator–broker Resource-

professional (professional (professional (professional autonomous–

relationship direction) responding) facilitating) citizen

(professional-

ancillary)

Service-individual Functionally Habilitation Wrap-around In-home and

interface specified pathways Supports person- community

services and (core process) driven located supports

models Service-driven (negotiated) Community-driven

Model-driven (pull) (push) (allocated)

Innovation Administrative and Outcome-driven, Person-centered Citizen-centered

mechanism functional cross-functional, interorganizational community-

effectiveness and inter- State and co-create based

efficiencies organizational personalized Support individual

internal to the Deliver customized experiences citizen automony

system services

Make standardized

service models

Dominant type of Many details to Complex interaction Complex interaction Unclear and

complexity manage between between key emerging futures

environmental stakeholders

factors

Coordination Hierarchy and Market price Network, dialogue, Seeing from the

mechanism command and mutual whole

adaptation community

Infrastructure Social legislation Rules, norms to Infrastructure for Infrastructure for

(laws, make the market learning and seeing in the

regulations, place work innovation context of the

budget) whole

Primary outcomes Placement, Face to face Individualized Citizenship and

and emergent personal care services, residential supports leading valued roles

outcomes for activity, and living community to jobs, home,

individuals housing presence and relationship

complexity in assuring compliance in order to contracts with the state system and referrals from a

deliver placement in day service settings and group service coordination system charged with making

residences, personal care, and activity. and monitoring Individual Service Plans (ISPs) that

Managed care is outcome-centered and de- reflect people’s needs for support. People with devel-

signed to provide the system with the means to opmental disabilities and their families are often

control costs by implementing cost-effective pathways seen as customers to be satisfied by the offerings and

to habilitative results. Framed by a waiver from some efforts of service providers. Though they are often

institutional requirements negotiated between state called consumers, people or their guardians do not

and federal Medicaid agencies, the system becomes a have control of funds. Money is allocated through a

sort of marketplace, with multiple providers seeking complex political bureaucratic process of rate setting

’American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 385INTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES VOLUME 49, NUMBER 5: 383–387 | OCTOBER 2011

Perspective: Individualizing supports H. Meissner

that, along with regulation and inspection, are the maintaining dialog that allows continuing mutual

primary means to coordinating and managing the adjustment with the people they rely on for

system. Service providers often work hard to influence assistance. Service providers act as suppliers of

the norms and practices that govern their market- trustworthy assistants, brokers, facilitators, and

place. There is potential flexibility to respond to partners in innovative ventures. They stretch

individual difference, but provider organizations themselves to include more and more people with

and state systems remain the holders of delegated complex needs and difficult circumstances. The state

responsibility to assure compliance with regulations system’s role is to assure fair and adequate funds for

intended to keep people healthy, safe, and moving necessary assistance, actively promote learning and

toward agreed goals. The system allocates many of its innovation, and safeguard those people and families

costs through billable units of face-to-face contacts, who are isolated and vulnerable until they can find

so, in a sense, such contact is an outcome of managed the connections they require.

care avidly tracked by service providers. A generation These innovative forms of support differ

of small group residences and day programs that primarily in their horizon of action. Integrative

support people’s presence in community settings have supports are focused on the proximate desires of

come into being with managed care funding, though more and more people with developmental disabil-

innovation is typically the design and implementa- ities to live a real life. When people with devel-

tion of a revised program model rather than ar- opmental disabilities have the experience of others

rangements tailored to individual circumstances. listening to them respectfully, living a real life

Institutional care and managed care display means having a place to call home, an intimate

considerable continuity, but a major shift separates relationship, friends, and a real job. In the current

them from the innovative edges of the field: service ecology, achieving these ordinary human

integrative supports and community supports. desires calls for a great deal of skillful partnership in

These two pairs of approaches to support are as innovation and negotiation to mobilize disability

different from each other as a manual typewriter system funds and build productive connections with

and a new laptop in terms of function, design, other local assets, such as housing providers and

capacity, and mode of production. employers.

Integrative supports and community supports Community supports assist people to hold even

both require a re-ordering of relationships with wider aspirations than living a real life. Service

and around people who have developmental dis- workers develop their capacities to act as a resource

abilities and their family. These relationships are to people’s exploration of their contributions as

based on a fundamental shift to power with a citizens to building stronger neighborhoods, associ-

committed group of people with differing assets. ations, congregations, and a more inclusive and

They bring to the task of supporting people with sustainable local economy, polity, and environ-

developmental disabilities the pulling together of ment. Innovation focuses on supporting people to

many assets necessary to have a flourishing life. take up valued and contributing social roles in a

Mindful effort to discover and build on a sense of greater variety of settings.

the person’s developing capacities and autonomy These shifts may reflect yet another evolution

guides the work, which is rooted in the values of of how we view persons with developmental

democracy and the struggle by people with disabilities and their place in our world. This, in

disabilities for human and civil rights and recogni- turn, has an impact on how the system and

tion that continuing learning and innovation are providers of service respond to this emerging social

essential. The need for competent assistance and dynamic. How to encourage the emergence of new

a variety of safeguards is negotiated on a person-by- service paradigms without engaging in a never-

person, situation-by-situation through deliberation ending dance of competing commitments is the

rather than assigned to simple conformity with ex- core question for those who seek an inclusive life

ternal rules. Individuals with developmental dis- for persons with intellectual disability. Teasing out

abilities and their family do not delegate complete and nurturing evolutionary thinking and doing is

responsibility to service providers. They build the task for transformational leaders in all sectors of

security and flexibility by extending and organizing our society (i.e., in families, in our neighborhoods

their personal networks, taking as much control and governmental sectors, and in business and

of system resources as circumstances allow, and nonprofit arenas). Promoting cultural change (i.e.,

386 ’American Association on Intellectual and Developmental DisabilitiesINTELLECTUAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES VOLUME 49, NUMBER 5: 383–387 | OCTOBER 2011

Perspective: Individualizing supports H. Meissner

shifting mental model) requires innovation that is invitation to engagement. The invitation goes out

socially focused. This is about innovating genera- to all key stakeholders to join in a journey of self

tive relationships, not discovering new tech- and system transformation. From a place of

nology. Social innovation calls for actions that profound appreciation and humility, safe social

ignite personal journeys of self-awareness, re- clearings and containers for dialogic inquiry, deep

aligning relationships away from hierarchy to learning, and innovative practice are created and

partnership, and transforming our communities nurtured. In doing this we are reordering our world

where difference and diversity is embraced. Al- away from fragmentation and delegation to com-

though social innovation can take place within any munity connections. There will be a need for new

sector, more than likely it will occur in the white power arrangements and organizational forms.

spaces between the family, local community, busi- Critical to this transformational process is finding

ness, nonprofit providers and government. When we added the leverage points for change by working

learn to move from our defined spaces and roles into within our present service structures, redesigning

a common community agenda, perhaps individual- traditional services to individualized supports, and/

ized supports will then become mainstream practice. or inventing new ways to support individuals with

A cultural change that supports persons with intellectual disability as true citizens of our

disabilities to assume full citizenship in our local communities.

communities and experience a real life requires the

morphing of deeply held beliefs about disability and

the roles and relationships at all levels (individual, References

team, organization, state, and nation) and sectors of

society (household, civic, government, profit, and Mount, B., & VanEck, S. (in press). Keys to life:

nonprofit) from ‘‘taking care of’’ to partnership with Creating customized homes for people with

people who have disabilities. As mental models disabilities using individualized supports. Toronto:

shift, a capacity to see the world from a different Inclusion Press. Self-Advocacy Association of

perspective is developed. From new perspectives, New York State.

new relationships among individuals, organizations, Individualized Supports Think Tank. (2007). Al-

and sectors in society are formed to create social bany, NY: Author. Retrieved from www.sanys.

innovations that ignite movement towards a more org/ISTTBrochureColorApril92007.pdf

progressive support model. Ultimately, cultural Scharmer, O. (2009). Theory U: Leading from the

change emerges from the ongoing interaction and future as it emerges. San Francisco: Berrett-

social negotiation that occurs among key commu- Koehler.

nity members during processes that enable innova-

tive support practices.

Committed change leaders with a vision of Author:

citizenship leading to lives of valued contribution Hanns Meissner, PhD (e-mail: HMeissner@renarc.

and involvement for persons with intellectual org), Executive Director, The Arc of Rensselaer

disabilities can start the change process with an County, 79 102nd St., Troy, NY 12180.

’American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 387You can also read