Grazing lands and opportunistic models: the political ecology of herd mobility in northern Côte d'Ivoire Parcours d'élevage et modèles ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Grazing lands and opportunistic models: the political ecology of herd mobility in northern Côte d’Ivoire Parcours d’élevage et modèles opportuntistes : L’écologie politique de la mobilité des troupeaux dans le nord de la Côte d’Ivoire. Thomas J. Bassett and Moussa Koné Department of Geography University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign bassett@uiuc.edu Abstract This paper presents the results of three years (2001-2004) of field research on herd mobility in the Korhogo region of northern Côte d’Ivoire. Herd mobility is an important livestock management strategy in African savanna environments. The new pastoralism literature emphasizes the ecological rationality of herd movements. The opportunistic grazing model that informs these studies argues that livestock management practices are highly structured by environmental instability and contingent events. The literature assumes that pastoralists possess perfect environmental knowledge and unhindered access to rangelands as their herds move about in unpredictable patterns in response to changing rangeland conditions. Our research shows that herders often return to the same places year after year. The regular north-south movement of FulBe herds is determined not only by pasture quality, but also by social and political relationships that mediate herder knowledge about and access to rangelands. We argue that herd mobility patterns are embedded in the social networks and power relationships that shape natural resource use rights. An analysis of FulBe herd movements before and after the 2002 rebellion in Côte d’Ivoire illustrates this argument. The case studies also demonstrate that FulBe land use patterns are embedded in ecological relationships, notably livestock adjustments to diseased environments. The political ecological approach to herd mobility more fully illustrates these intertwined social, political, and biophysical dimensions of resource use in West African savannas. Key words: Opportunistic grazing, herd mobility, rangeland access, political ecology. Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 1

Résumé Cette communication présente les résultats d’une étude de recherche de trois ans (2001-2003) sur la mobilité des troupeaux dans la région de Korhogo au nord de la Côte d’Ivoire. La mobilité des troupeaux est une importante stratégie d’élevage dans les régions de savanes africaines. La nouvelle litérature sur la pastoralisme souligne l’importance de la rationalité écologique des mouvements des troupeaux. Le modèle opportuniste qui informe ces études soutient que les pratiques de l’élevage sont hautement structurées par l’instabilité environmentale et les évènements contingents. Cette litérature suppose que les éleveurs possèdent une connaissance parfaite de l’environnement et ont un libre accès aux ressources pastorales au fur et à mesure que les troupeaux se déplacent en réponse aux conditions changeantes de pâturage. Notre recherche montre que les éleveurs reviennent le plus souvent aux mêmes endroits année après année. Le mouvement régulier nord-sud des troupeaux peuls est déterminé non seulement par la qualité de la pâturage, mais aussi par les relations sociales et politiques qui facilitent l’accès aux resources pastorals et aux renseignements sur la qualité des ces pâturages. Nous soutenons que la mobilité des troupeaux est enchassé dans les réseaux sociaux et les rapports de force qui forment les droits d’exploitation des ressources naturelles. Une analyse des mouvements des troupeaux peuls avant et après le début de la rébellion de Septembre 2002 illustre cet argument. Les cas d’étude démontrent que l’exploitation des resources naturelles est enchevêteré dans les relations ecologiques, notamment l’adaptation du bétail aux environments infectés de maladies. L’approche de l’écologie politique à la mobilité des troupeaux illustre mieux l’interaction entre ces dimensions sociales, politiques et biophysiques de l’exploitation des ressources dans les savanes ouest africaines. Mots clés: Elevage opportuniste, mobilité des troupeaux, accès au pâturages, écologie politique Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 2

INTRODUCTION

Extensive research on savanna ecology and African pastoralism underscores the importance of

herd mobility as an important livestock management technique. Spatial and temporal variation in

pasture quality motivates livestock producers to move herds from one location to another, often over

long distances. Access to geographically dispersed pastures depends, however, on the grazing rights

held by livestock producers (Niamir-Fuller and Turner 1999; Scoones 1999). Flexible land rights

systems that allow outsiders to utilize grazing resources facilitate pastoral mobility (Toulmin and

Quan 2000). Frequent herd movements in the context of fluctuating pasture quality and flexible land

rights systems describe what is widely known as “opportunistic grazing” (Sandford 1983; Behnke, et

al., 1993; Scoones 1995).

With its emphasis on the spatial heterogeneity of rangelands and frequent herd movements

that are finely-tuned to changing grazing conditions, the opportunistic grazing literature tends to

idealize, if not romanticize, herder-environmental relations (McCabe 2004). The opportunistic model

stresses the ecological determinants of livestock production and assumes perfect knowledge of

environmental variability and unhindered access to rangelands. Our research in northern Côte d’Ivoire

urges a rethinking of the opportunistic grazing model by suggesting that pastoralists’ knowledge of

environmental change is imperfect and that their access to land is highly constrained. The research

asks: How do herders learn about changes in range conditions? How quick are they to respond to this

information? In what ways are herd movements influenced by social as well as ecological

determinants? Do all herders face the same obstacles to mobility, or do differences exist based on

location, herd size, and the types of social networks in which they participate? The project examines

actual (versus idealized) patterns of herd mobility in northern Côte d’Ivoire in the context of a new

rural land law requiring land registration and titling. A major hypothesis of this research is that the

land access rights and herd mobility patterns of FulBe pastoralists will be increasingly constrained by

the land registration process.

Three hypotheses structure the research questions and methodology of this study. The first is

that the FulBe’s ability to exploit environmental heterogeneity is primarily linked to their access to

grazing resources, and secondly to their knowledge of changing range conditions. Drawing on the

work of Sara Berry, we hypothesize that pastoralists invest in the “means of negotiation as well as in

the means of production” (Berry 1993, 15) to secure access to range resources and environmental

information. The research investigates the types of social networks in which FulBe herders participate

to obtain grazing rights and information at a variety of scales (patch, landscape, region) (Turner 1999).

The second hypothesis states that FulBe herd mobility will become increasingly restricted in

the context of the new land law in Côte d’Ivoire and the ethno-national politics known as Ivoirité.

FulBe pastoralists are relatively recent immigrants who must form guest/host relationships with land

controlling autochthonous groups. The land privatization process will force the FulBe to renegotiate

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 3such relationships at a time when xenophobic sentiments are being stirred up by politicians seeking to

exclude foreigners from political office and from owning land (Bassett 2003; Chauveau 2000). We

hypothesize that the creation of private property rights in this tense political atmosphere will require

FulBe herders to pay grazing fees to farmers on whose land FulBe cattle graze. Land privatization and

Ivoirité politics may also induce a return migration of small to medium-scale herders to Mali and

Burkina.

The third hypothesis is that there is a discrepancy between the temporal and spatial patterning

of grazing resources and actual herd movements. Herder access to good rangelands is constrained by

conflicts with peasant farmers over the perennial problem of crop damage. Following the September

2002 rebellion that divided the country into a rebel controlled north and a government controlled

south, access to rangelands in the northern savannas became mediated by rebels rather than by central

government administrators. Rebel exactions on pastoralists (e.g. cattle gifts, safe passage permits,

inflated crop damage payments) and an empowered farming population has led herd owners to modify

their behavior (e.g. they are more quick to pay crop damages) but not their overall grazing strategy

(e.g. grazing in agricultural zones). Indeed, one of the remarkable findings of this study is that

transhumant herders return to the same rangelands year after year. The following case studies present

both a mapping of herd mobility and an explanation of these geographic patterns.

This paper’s contribution to the new pastoralism literature is twofold. First, it provides

empirical data on actual as opposed to theoretical herd movements. These data allow us to advance the

opportunistic grazing model by showing how constrained access to and limited information about

rangelands results in their incomplete utilization. Second, environmental knowledge and resource

access rights remain under-theorized in the opportunistic grazing literature. This paper contributes to

theory building by demonstrating the importance of social networks in obtaining information about

and access to rangelands. We argue that some herders are incapable of participating in these networks,

especially for long-distance transhumant treks, because of insufficient labor and monetary resources.

RESEARCH METHODS

The field research for this study took place in the Korhogo region of northern Côte d’Ivoire

between November 2001 and July 2004 (Figure 1). We selected eight herds based on the criteria of

herd size and type of mobility. Three FulBe herds (small, medium, large) graze within the terroir of

Katiali. Four FulBe herds and one farmer-owned herd engage in a long-distance seasonal trek

(transhumance) during the dry season months of January-May.

A FulBe research assistant systematically noted the herd movement patterns of eight herds

throughout the region over this period using a GPS receiver. The coordinates of each herd’s location

were subsequently noted on a Landsat ETM+ satellite image of the pastoral zone taken in November

2000 (Figure 2). Each time a herd was encountered, the research assistant administered a two-page

questionnaire that focused on range conditions, land access problems, and herd productivity. The

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 4following section presents the results of the herd movement study for the year prior to the 2002

rebellion. This is followed by an examination of herd mobility patterns for two years during the

rebellion. The final section summarizes the results of the two periods and argues that herd mobility is

strongly influenced by social, political, and economic considerations as much as by rangeland

conditions.

MAPPING HERD MOBILITY

Interviews with FulBe, Senufo, and Jula herd owners revealed at least a dozen herd mobility patterns.

These combine different households, territories and temporalities. Amongst this diversity, two basic

types stand out based on the scale of herd movement: terroir-scale movements and long distance treks

also known as transhumance. Terroir-scale herd movements are illustrated in the mobility pattern of

Mamadou Sidibé’s herd illustrated in Figure 3. These movements are linked to changing pasture

quality (grass, water, disease), agricultural cycles, and the presence of other herds in the terroir of

Katiali. This pattern is typical of small-to-medium scale livestock producers who do not take their

cattle on long-distance treks because of too few animals or insufficient financial resources to hire

herders and/or to pay for crop damages caused by their cattle while on transhumance.

Long-distance treks involve moving herds some 100-225 kilometers during the long dry

season (October-May) in northern Côte d’Ivoire. Figures 4 and 5 show dramatic differences in range

conditions for the same period (March 25-29, 2002) that are 225 kilometers apart. In the Katiali region

(Figure 4), grazing conditions are not good. Grasses are lignified, there are few water sources, and

there are a lot of herds, some of which have arrived from Mali on seasonal transhumance to northern

Côte d’Ivoire. Cattle do not gain much weight and the interval between calving is relatively long. In

the Béré River region (Figure 5) to the south, early rains have produced a flush of highly palatable

grasses. Cattle are in good health, they have put on weight, and experience calving rates that are

higher than those that stay in the Katiali region. This mobility pattern is most commonly practiced by

relatively wealthy herd owners.

The herd movements of all eight herds are shown in Figure 2 for the period 2001-2002. In the

case of transhumant herds, we find that the largest herds are the first to move south. This is partly

explained by the relative wealth of their owners which enables them to employ and provision salaried

herders and to negotiate any problems encountered on route. The timing of their departure is linked to

deteriorating range quality but also to the existence of an agro-pastoral calendar that in principle

prohibits southerly treks until crops are harvested in southern Korhogo and northern Mankono regions.

This calendar sets the transhumance departure date to January 1 in the Niofoin region and to February

1 in the southern Korhogo region. As we will see below, these dates are not closely followed by

transhumant herders which leads to crop damage and conflicts with farmers during the transhumance

trek.

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 5Cattle are not taken to just anywhere. First, they are invariably directed to agricultural zones

where they graze the nutritious crop residues in recently harvested fields. Indeed, pastoralists try to

time their southerly descent to follow the cotton and rice harvests so their animals can graze on crop

stubble. Pastoralists also take their herds to agricultural zones because land clearing by farmers

reduces the chances of their cattle contracting certain animal diseases like trypanosimiasis.

Second, farmer-herder conflicts over uncompensated crop damage severely limit herd

movements. Herd owners spoke frequently about farmers who chased transhumant cattle out of certain

areas. Some cattle were rounded up by farmers in the Marandala area and put in corrals and not

released until herd owners paid for crop damages, even if their herds were not to blame. Some farmers

fired their shotguns near cattle grazing by their fields as a preventative measure. In short, by placing

certain areas off-limits, farmers prevented herders from taking their cattle to good pastures. The

opportunistic grazing model rarely considers such constraints on herd mobility.

The capacity of transhumant herders to lead their cattle to temporally and spatially shifting

rangelands is also contingent on their knowledge of good grazing areas. The opportunistic grazing

literature assumes that pastoralists possess omniscient powers and thus know where pasture conditions

are optimal. Interviews with herders and herd owners revealed the extent to which environmental

knowledge is contingent on social networks, range scouting, and chance encounters. Herd owners

learned of the whereabouts of good grazing (recent rainfall, crop residues, grass regrowth following

burns) from (1) their own reconnaissance; (2) other herd owners with whom they spoke in villages and

markets; (3) from their hired herders who learned of good rangelands from other herders; and (4)

cattle merchants who frequently travel in the bush to buy cattle. The following case study of the herd

movements of Sita Sangaré reveals the multiple factors influencing herd mobility patterns prior to the

September 2002 rebellion.

Herd mobility prior to the rebellion: The case of transhumant herder Sita Sangaré

Figure 6 shows the movements of one herd owned by Sita Sangaré, a wealthy FulBe herder

who possessed six herds totaling more than 600 head. The timing of Sita’s departure from the Katiali

area was hastened by a conflict with local farmers. Some of his animals had been impounded in a

nearby village for causing crop damage. After paying a fine, he left the area on November 4, 2001

about two months earlier than the January 1 date decreed in the agro-pastoral calendar. His herd made

its way south to the Guiembé and Dikodougou areas where the herd grazed for a month on crop

residues and pasture regrowth following burning. Herd mobility was temporarily constrained in this

area for three reasons: one of the hired-herders fell ill; the herd was impounded in a village for crop

damage; and the herders had to wait for Sita to bring food provisions before proceeding further south.

The herd arrived in the Bada area in the subprefecture of Dikodougou in late-December (herd visit

date #4, Figure 6). The herd was expelled from one area (Yero) due to crop damage and was not

allowed to graze in good grazing areas around Boron and Mara because of farmer hostility.

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 6In January the herd moved further south to the Somokoro region where it spent the next four

months grazing crop residues, pasture regrowth, savanna grasses, tree leaves and fruits. The Somokoro

area (s/p Sarhala) is where Sita had regularly taken his cattle in previous years. This is a zone to which

large numbers of Senufo farmers from the Korhogo region migrated during the 1970s to grow cotton

(Le Roy 1981). The transformation of the tse-tse fly infested guinea-savanna into cropland had the

two-fold effect of reducing tse-tse fly habitat and creating new highly desirable grazing spaces (fallow

fields, crop residues).

Sita spent most of the dry season near his herds during the transhumant trek. If they were in

the Dikodougou region, he lodged in Dikodougou to stay in contact with his herders. It was important

that he be present to provision them with food, to resolve any herding related problems, and to select

new grazing locations. When he directed the herds to move further south towards Bada or Mara, he

also moved. While the herds grazed in these regions, Sita stayed in a nearby community to manage

them. He employed a special herder to serve as a courier between him and his herders. This “spare

herder” (bouvier de secours) also herded cattle in the event that a herder fell ill or suddenly quit his

job.

In each community where he stayed during the transhumance trek, Sita had developed a

network of social relationships that were integral to this mobile livestock raising system. The most

important relationship was with a local influential person (village chief, lineage head) who served as

Sita’s host (tuteur) in the community. Sita had hosts in all the communities where he stayed along the

transhumant route. If he encountered any local problems during his visit, the host would serve as his

intermediary to help resolve the issue. For example, if Sita was unable to resolve a crop damage

incident, he would ask his host to accompany him during the sometimes difficult negotiations. The

relationship was reciprocal. If his host encountered some pressing financial need such as funding a

wedding or funeral, Sita would contribute money. He also regularly gave gifts to his hosts. In sum, the

guest-host institution is an important formal arrangement that allows outsiders to integrate themselves

in communities which in turn gives them access to local resources.

Sita’s network also included other FulBe herd owners, cattle merchants, butchers, and herders

who exchanged information about rangeland conditions. This would often take place at night in the

communities where he was temporally staying. Cattle merchants were among the most well-informed

about changes in pasture conditions since they were often in the bush looking for cattle to buy. Other

herd owners who had been in the bush visiting their herds that day would return with rangeland

condition information that they would share with other herd owners. Herd owners would also scout for

new grazing locations (e.g. recently harvested fields) during the day. Hired-herders looking for stray

cattle would also talk about the areas through which they passed. In this way, environmental

knowledge was generated and circulated among herders and herd owners that commonly influenced

decision making behind cattle movements.

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 7Again, mobility was not unconstrained. Herders could not lead their animals to some of the

best grazing areas of the region. For example, excellent rangelands exist to the southeast in the

Tiéningboué area during much of the dry season. However, it was well known that FulBe cattle were

not welcome in the area. Herders reported animals being poisoned and fired upon by farmers of the

subprefecture. As a result, Sita’s herd was forced to graze in the area south of Somokoro shown in

Figure 7.

Herd mobility patterns 2002-2004

The September 19, 2002 rebellion in Côte d’Ivoire significantly changed the conditions of livestock

raising in the northern savanna region. A major shift occurred in power relations not only between

rebels and the state but also between farmers and herders. Prior to the rebellion, government

administrators (e.g. Subprefects) favored FulBe herd owners in crop damage cases after receiving

some financial incentive to do so. In contrast, the rebels, who were primarily from farming families in

the north, recognized the political advantages of siding with farmers in crop damage cases. Indeed,

one of the rebels’ goals in the first year of the rebellion was to win the hearts and minds of the local

population. When they became involved in crop damage settlements, rebel soldiers systematically

favored farmers. Rebel bias and increased farmer hostility towards the FulBe subsequently modified

herder decision making regarding when and where to move their cattle.

Herd mobility patterns for transhumant herds particularly changed. First, the timing of

transhumance was delayed. In contrast to earlier years when transhumant herders headed south well

before the official January 1 transhumant date, they now waited. The owners of the largest herds were

typically the first to go on transhumance because of their financial means to negotiate problems on

route. Other herders waited until they received word from these wealthy herders about the relative

risks of going on transhumance. In mid-January 2002 there were very few transhumant herds in the

southern Korhogo region when in normal times they would be plenty.

Second, some herd owners decided not to go on transhumance when they heard about rebels

forcing the FulBe to pay exorbitant crop damages. Others changed their transhumance circuit. For

example, a number of herd owners trekked their cattle to the western frontier zones of Odienné rather

than go south to the Mankono region. Some moved their households and herds to the frontier areas of

Guinea (Touba) and Mali (Odienné) so they could quickly cross over into a conflict free zone in the

event of greater political instability.

Third, newly empowered farmers also began to restrict herder access to crop residues. For the

first time, they began to charge grazing fees before a herd could graze the stubble of harvested fields.

Herders were required to pay field owners between 1500-2000 FCFA per hectare grazed by their

cattle. The price of “buying a field” varied with its size and the amount of crop residue. One herder

explained:

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 8“If the cotton harvest is complete and you want your herd to graze in a harvested cotton field,

you have to give money first. One can no longer graze [one’s cattle] for free in a field. You

can buy a field for 5000 francs, 7500, 3000, 2500; you can even have some for 1000 francs.

You can even have the largest fields for 15,000.

This monetarization of grazing rights is linked to a number of political-economic processes,

some of which had preceded the rebellion. First, ordinary Senufo and Jula farmers had come to

appreciate the value of cattle and the basics of livestock raising as a result of their use of oxen for

cultivation. Some of the wealthiest farmers began to invest in cattle and had constituted their own

herds. Second, the large influx of FulBe herds into the Korhogo region since the early 1970s combined

with the expansion of cotton fields and cashew orchards led a decline in pasture area. This scarcity of

good pastures increased the value of crop residues in the eyes of farmers and herders alike. Third, the

new Rural Land Law (la Loi Foncière Rurale) and its predecessor, the Rural Land Plan (le Plan

Foncière Rurale) sensitized farmers to the individual benefits of controlling land. Even though the

land registration process had yet to begin, farmers were already beginning to view land-based

resources as commodities with a monetary value. When FulBe herders gave money to a field owner,

they called this exchange a “tip” as if it was up to their own discretion. In reality, the price of entry

was negotiated and the FulBe clearly recognized that it was an obligatory payment. Fourth, the

rebellion empowered peasant farmers to exact payments from the FulBe for their hitherto free access

to range resources. The FulBe, for their part, feared rebel retribution if they did not make these

obligatory payments.

The rebellion increased the costs of livestock raising in other ways as well. In the first few

months, rebels used their own money to purchase supplies. But when this money ran out, they began

to make exactions on the local population. Rebels would also positioned themselves at well-known

watering points (rivers, dams) and charge herders 5000 FCFA for watering rights for each herd.

Transhumant herders were also required to obtain a safe passage permit (laissez-passer) for 10,000

FCFA to move from one zone to the next. Road blocks also multiplied. To continue pass these

barriers, herders and farmers alike had to pay “the cost of tea” (100-500 FCFA).

Herd owners also encountered problems in recruiting salaried herders (kalo woro) who were

understandably reluctant to herd cattle under these difficult and high-risk conditions. The only way to

recruit herders was to offer higher salaries.

The war also disrupted the commerce in veterinary medicines, especially live vaccinations.

Prior to the conflict, Côte d’Ivoire imported cattle vaccines from Cameroun. This trade ended with the

war. An illicit trade took its place but the quality of vaccines was not assured because of poor

refrigeration. The poor quality of cattle vaccines meant that transhumant herders were less likely to

take their herds to grazing areas where animal health was at risk.

At the same time that the costs of mobile livestock significantly increased, herder incomes

delcined as livestock markets nearly collapsed. The cattle markets in Bouaké, Daloa, Séguela and Port

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 9Bouet still operated. However, exactions made on cattle merchants by both rebel and government

soldiers along trekking and trucking routes made this commerce prohibitively expensive. One cattle

merchant reported in 2004 that one had to pay 500,000 FCFA per herd before entering the market area

at Vavoua. As a result of these financial losses, cattle merchants were reluctant to engage in this trade.

These deteriorated market conditions led to a reduced demand for cattle in the north and,

consequently, lower prices. Animals that had sold for 50, 000 FCFA prior to the rebellion now sold for

30, 000 FCFA.

Under these conditions of increased costs of production and lower market prices, some FulBe

decided to return to Mali and Burkina Faso to wait until the situation improved. Some herders

considered the situation so bleak that they sold their herd(s) in Côte d’Ivoire and returned to their

homes in Mali and Burkina.

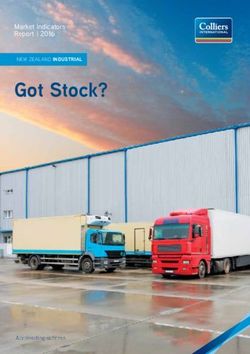

The effects on herd mobility of these deteriorating conditions are illustrated in the following

case study of the herd movements of the brothers Dramane and Hassane Sidibé for the period

September 2003 through July 2004 (Figure 8).

Herd mobility following the rebellion: The case of Dramane and Hassane Sidibé

The brothers Dramane and Hassane Sidibé kept a medium size herd of 98 head in the Katiali

region since 1995 where it grazed within the region (terroir scale) all year. It did not leave on a long

distance transhumance. However, in December 2001, local farmers forced them to leave the area

because of repeated incidences of uncompensated crop damage. Over the next two months they

migrated with their families and herd to the Bada area south of Korhogo and west of Tortiya. They

established their new camp near Samatiguila and for the next two years engaged in long distance

transhumance between Samatiguila and Mankono, a distance of some 110 kilometers.

During the first year of the rebellion (September 2002-September 2003), the herd stayed

relatively close to the Sidibé camp. The farthest the herd grazed from their settlement was 25

kilometers. Between October 2002 and January 2003, the herd grazed outside of the small community

of Bada on crop stubble in harvested fields and fallow grasses in between fields. Animals also

browsed the leaves and fruits of certain trees. The Sidibés encountered problems with local farmers

who did not want to see cattle grazing at the edge of their fields that still held standing crops of rice,

cotton and maize. Farmers chased cattle away from their fields whenever they approached day and

night until the end of the harvest.

Despite these unfavorable political conditions, the Sidibé herd continued to graze within

agricultural zones. In January and February their animals gained weight feeding on the crop residues

found in farmers’ fields. Herders reported that many fields were off limits because farmers had

stocked their cotton harvest in their fields. Many farmers had also planted cashew trees in fallow fields

which herders were reluctant to enter in fear of being forced to pay large sums of money in crop

damages. To avoid the wrath of farmers, the herds entered harvested fields in the middle of the night

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 10and left before sunrise. Crop damage did occur but now herders were quick to compensate farmers. It

was less costly for herders to resolve disputes with farmers to avoid the more costly intervention of

rebel mediators.

Cattle diseases began to appear in April and May, notably animal sleeping sickness

(tyrpanosimiasis) and contagious bovine pleuropneumonia. War-related shortages of veterinary

medicine meant that herders were unable to protect their herds against some of these diseases. For

those who did treat their cattle, they discovered that vaccines did not work because they had not been

properly refrigerated. Pleuropneumonia spread widely during the rainy season. Foot and mouth

disease (la fiève aphteuse) also appeared in the region during October and November.

The Sidibé herd returned to its rainy season pasture around Samatiguila between June and

October where it grazed until the beginning of the dry season. The brothers reported that there were

fewer animals in the zone due to the movement of herds towards the frontier zone of Touba and

towards Séguela because of the general insecurity. During the rainy season months of May-October,

cattle grazed on the highly palatable grasses growing in fallow fields at the outskirts of villages in the

area.

By the early dry season month of November, these rainy season pastures had declined in

quality. Herds were now led into the heart of agricultural zones to graze on crop residues (e.g. maize

and peanuts) in harvested fields. However, most cotton and wet rice fields had not yet been harvested.

Not surprisingly, there were many crop damage incidents and, as a result, tensions rose between

herders and farmers. Some farmers prohibited nocturnal grazing in their area and beat up herders who

they found breaking this rule. Herders learned from other herders they met in the bush where good

grazing could be found and what areas to avoid because of hostile farmers.

In contrast to the first year of the rebellion when mobile livestock producers were cautious

about taking their herds very far from their rainy season camps near Samatiguila, the Sidibé brothers

now thought it less risky to send take their herd on a long-distance trek. The herd left January and

April 2004 on a 110 kilometer transhumance towards Somokoro and the Béré River (Figure 8).

The transhumance destination was less important than the journey. Most fields had been

harvested in the region at this time, and crop residues were plentiful. The grazing strategy thus

consisted of scouting for harvested fields and leading herds to graze in them. The Sidibé herd would

typically spend half a day grazing the stubble of a 4-6 hectare field, take water at mid-day, and graze

another field in the late afternoon. The herd was taking water at the Béré River during the month of

April when the first rains appeared. The flush of new grasses provided nutritious pasture. The herd

started its return journey to Samatiguila following the northerly movement of rain and pasture re-

growth. However, as old fields were planted anew, the grazing area diminished considerably. Herds

grazed on fresh grasses at the edges of fields and herders had to be attentive to the ever present

problem of crop damage.

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 11The transhumance trek was not without its problems and surprises. In January the rebels

required that herders obtain a laisser-passer for each herd at a cost of 20,000 FCFA/herd. There were

also arbitrary exactions made by rebel soldiers. For instance, in early January a group of armed rebels

asked seven transhumant herders for 200,000 FCFA for no particular reason. The herders acquiesced

to this request. As the herds progressed further south, new laisser-passer permits had to be obtained.

Some of these permits surprisingly gave herders the right to take their herds anywhere they wanted,

even to areas where hostile farmers had excluded them prior to the rebellion. It was not that the rebels

favored herders over farmers. Herders still paid farmers and rebel mediators for crop damage. The

new “pay as you go” arrangement provided new herders with greater access to grazing lands that were

formerly off-limits. Wanting to avoid any conflict with the rebels, farmers reluctantly allowed herders

into their zones.

CONCLUSION

One of the most important findings of this research is the remarkable continuity in herd

movement directions. This finding differs from the opportunisitc grazing literature which conveys the

image of herds moving in many directions to take advantage of temporally and spatially shifting range

resources. The two case studies presented here show that transhumant herders followed the same

trajectory year after year. This observation is even more striking because the period of study included

a rebellion and the collapse of state authority in the area. There are three major reasons that explain

this remarkable continuity in herd movement patterns.

The first relates to the social networks that herders develop in communities along

transhumance routes. Herd owners invest in these social relationships, especially with village hosts, to

resolve any problems that arise from their herds grazing in the region. Herd owners send their cattle to

the same areas year after year in part because they feel confident that these relationships allow them to

manage the risks of grazing cattle in areas far from their rainy season camps.

A second reason why herd owners return to the same zones year after year is because their

animals do well in these areas. Transhumant cattle gain weight during the dry season, cows have

higher fertility rates, and the wealth of herd owners subsequently increases. The FulBe report that their

cattle better acclimate to the areas to which they return year after year. The widespread use of

veterinary medicines helps to explain this extension of cattle into the sub-humid savanna where

disease risks are high.

Third, the transformation of savanna environments by immigrant cotton growers is a key

process that creates good rangeland and reduces the habitat of the dangerous tse-tse fly. The timing

and direction of herd movements is linked to the food crop and cotton harvests that take place in

December and January in the southern Korhogo region. The stubble of harvested fields provides the

best grazing according to herders. The second most important pasture is grass regrowth in burned over

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 12fallow fields. This nutritious pasture appears following burns as late as February and March. By April,

the first rains are falling in the Mankono region that brings fresh pasture grasses and excellent grazing.

In summary, pastoral land use patterns in northern Côte d’Ivoire are embedded in political and

ecological relationships that mediate access to rangelands and environmental information. Cattle herds

graze in hostile political and ecological milieus where land-use conflicts and animal diseases result in

the incomplete utilization of potential rangelands. As Peters (2002) and Scoones (1999) argue, in

instances where competition and conflict over land-based resources intensifies, it is often wealthy and

influential individuals who are able to gain access to “exclusively managed” resources. In northern

Côte d’Ivoire only the wealthiest herders that have the financial means to invest in salaried herders,

pay crop damages, and invest in social relationships engage in long-distance transhumance. Since herd

productivity is higher for herds that go on transhumance, wealth begets more wealth. It is this ability

to invest in the “means of negotiation as well as the means of production” (Berry 1993, 15) combined

with the practical knowledge of herding cattle in hazardous environments that help to explain herd

mobility patterns in northern Côte d’Ivoire.

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 13BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bassett, T., 2003. ‘Nord Musulum and Sud Chrétien’: Les moules médiatiques de la crise ivoirienne,”

Afrique Contemporaine 206:13-28.

Behnke, R. H., I. Scoones and C. Kerven, (eds) 1993. Range Ecology at Disequilibrium: New Models

of Natural Variability and Pastoral Adaptation in African Savannas, London, Overseas Development

Institute.

Berry, S., 1993. No condition is permanent: The social dynamics of agrarian change in sub-Saharan

Africa , Madison, University of Wisconsin Press.

Chauveau, J.-P., 2000. Question foncière et construction nationale en Côte d’Ivoire, Politique

Africaine , 78: 94-125.

Le Roy, X., 1981. Migrations cotonnières sénoufo: Premiers resultats , Abidjan, Min. du Plan et de

l’Industrie-Centre Orstom de Petit-Bassam.

McCabe J. T., 2004. Cattle bring us to our enemies: Turakana ecology, politics, and raiding in a

disequilbrium system. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press.

Niamir-Fuller, M. and M. Turner, 1999. A review of recent literature on pastoralism and

transhumance in Africa, in Managing mobility in African rangelands , M. Niamir-Fuller (ed) London,

Intermediate Technology Publications, pp. 18-47.

Peters, P., 2002. The limits of negotiability: Security, equity, and class formation in Africa’s land

sytems, in Negotiating Property in Afirca, K. Juul and C. Lund (eds) Portsmouth, NH, Heinemann, pp.

45-66.

Sandford, S., 1983. Management of pastoral development in the Third World, New York, Wiley &

Sons.

Scoones, I., 1995. Range management science and policy: Politics, polemics, and pasture in southern

Africa, in The Lie of the Land: Challenging Received Wisdom on the African Environment, M. Leach

and R. Mearns (eds), Oxford, UK and Portsmouth, NH, James Currey, Ltd. and Heinemann, pp. 34-

53.

Scoones, I., 1999. Ecological dynamics and grazing-resource tenure: a case study from Zimbabwe, in

Managing Mobility in African Rangelands: the legitimization of transhumance, M. Niamir-Fuller (ed)

London, Intermediate Technology Publications, pp. 217-235.

Toulmin, C. and Quan,

J. 2000. Evolving land rights, tenure and policy in sub-Saharan

Africa, " in

Evolving land rights, policy, and tenure in A f r i c a , C. Toulmin and J. Quan (eds), London,

DFID/IIED/NRI, pp. 1-30.

Turner, M., 1999. The role of social networks, indefinite boundaries, and political bargaining in

maintaining the ecological and economic resilience of the transhumance systems of Sudano-Sahelian

West Africa, in Managing mobility in African rangelands, M. Niamir-Fuller (ed) London,

Intermediate Technology Publications, pp. 97-123.

Colloque international “Les frontières de la question foncière – At the frontier of land issues”, Montpellier, 2006 14ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

HERD MOVEMENTS OF DRAMANE AND HASSANE SIDIBE

(November 4, 2003-July 30, 2004)

To Korhogo

Diko

Kadioha

Samatiguila

A.C

Bada

B,D,N

S,P E R,T Tortiya

Q

O M

Boron F

Mara

H

G

I

K

Somokoro Marandalla

J L

To

Bo

Tiéningboué

u

ak

é

To Mankono

Legend III-Nov 2003-Jul 2004

K-Mar 23

A-Nov. 4

Sous-Préfecture B-Nov. 16

L-April 2

Village C-Nov. 24 M-Apr. 21

D-Dec. 4 N-Apr. 27

Period 2003-2004

E-Dec. 14 O-May 7

Herd visit date D F-Dec. 24

Road P-May 21

G-Jan. 8 2004 Q-May 29

Main Road H-Jan. 20

R-Jun. 9

I-Feb 7

S-Jul. 16

J-Feb 25

T-Jul. 26

Figure 8You can also read