Evaluation of the efficacy of a South African psychosocial framework for the rehabilitation of torture survivors

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

34

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Evaluation of the efficacy of a South

African psychosocial framework for

the rehabilitation of torture

survivors

Dominique Dix-Peek*, Merle Werbeloff**

Abstract

Key issues box: Introduction: To address the consequences

• When treating torture survivors of past torture experiences as well as current

in developing countries, it is traumas and daily stressors, the Centre for

essential to consider the inherent the Study of Violence and Reconciliation

stressors and daily traumas in these (CSVR) developed a contextually

environments. appropriate psychosocial framework for

• To assist with the psychosocial the rehabilitation of individuals who have

impacts due to torture, an evidence- been affected by torture. Method: To test

based, contextually appropriate the efficacy of this framework, a quasi-

psychosocial rehabilitation experimental study was conducted with

framework has been developed by torture survivor clients of the CSVR who

the Centre for the Study of Violence met the 1985 United Nations Convention

and Reconciliation. Against Torture (UNCAT) definition. A

• Following a 3-month intervention comparison group of clients (n=38) was

based on this psychosocial initially included on a waiting list and

framework, torture survivors’ thereafter received treatment, whilst the

anxiety and functioning improve, treatment group of clients (n=44) entered

despite harsh contextual realities. straight into treatment. Results: Baseline

• However, ethical complexities t-test comparisons conducted on 13

and high levels of participant outcome indicators revealed significantly

attrition during longer therapeutic better initial psychological health and

intervention present challenges functioning of clients in the treatment group

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

to experimental endeavours than those in the comparison group, with

designed to test the efficacy of the moderately large differences on PTSD,

rehabilitation framework. trauma and anxiety, and strong difference in

depression scores. Three-month follow-up

comparisons using the conservative

Wilcoxon test revealed significantly greater

*) Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconcilia- improvement on the functioning and anxiety

tion (CSVR), South Africa indicators of the treatment group relative

**) Wits School of Governance, University of the

to the waiting-list comparison group (odds

Witwatersrand, South Africa

Correspondence to: ddixpeek@csvr.org.za ratios = 2.49 and 2.61 respectively). After a35

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

further three months, when treatment was presents this framework and describes a

based on the CSVR framework for both quantitative study designed to examine

groups, fewer than half the respondents the effectiveness of its use for torture

remained in the study (n=20 in the rehabilitation.1

treatment group; n=16 in the comparison

group), and the Wilcoxon repeated measures Torture and its consequences

test results on changes since baseline were Torture is a gross human rights violation

counter-intuitive: for these remaining clients, that distresses the individual, family,

there were now more significant outcome community and society at large. Despite

improvements for the comparison group a number of international conventions

than for the treatment group. However, prohibiting torture and cruel, inhuman and

the relative odds ratios for the groups degrading treatment (CIDT), torture is

were not significant for these indicators. still practised in more than 140 countries

Furthermore, the clients who dropped out internationally, and still widely practised in

from the treatment group had shown overall Africa where it has been criminalised in only

improvement in their psychological health 10 countries (Amnesty International, 2014).

and functioning in the initial three months Sub-Saharan Africa hosts the largest number

of the study, whereas those who dropped of refugees internationally, with South

out from the comparison group had shown Africa receiving most of the asylum seekers

improvements on fewer indicators. Thus, in Africa (McColl et al., 2010; UNHCR,

the research findings on the efficacy of the 2015). Many of these people are likely to

framework are inconclusive. Discussion: have been tortured in their country of origin

We suggest that this inconclusiveness can or in transit (McColl et al., 2010). Within

be explained by the severe challenges South Africa, current victims of torture

and ethical complexities of psychosocial include youth in conflict with the law, non-

research on vulnerable groups. The study nationals, and people who are in the wrong

highlights the serious problem of attrition place at the wrong time (Bantjes, Langa, &

of participants in the treatment programme Jensen, 2012; Langa, 2013).

which affected the overall study, and which The consequences of torture may be

may explain findings that at first appear categorised broadly as physical, psychological

counter-intuitive. and social. The physical consequences

may be complicated by the psychological

Introduction consequences (Quiroga & Jaranson,

Continuing traumas, daily stressors and 2005). Similarly, torture-related mental

T O RTU R E Vol u m e 2 8 , N um be r 1, 2 01 8

trauma reactions from past traumas are health problems can cause physical and

characteristic of torture survivors in social problems which impact on both the

South Africa. Consequently, in 2013, personal and social functioning of survivors

the Centre for the Study of Violence

and Reconciliation (CSVR) based in

Johannesburg, designed a contextually

appropriate, evidence-based psychosocial 1

While the intervention was named a “model”,

framework for guiding the long-term due to the multi-modal nature of the document,

it was felt to be more representative to call it a

rehabilitation of individual survivors of

multi-modal framework for the rehabilitation of

torture (Bandeira et al., 2013). This paper torture survivors.36

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

(Baird, Williams, Hearn, & Amris, 2016). Although the South African Constitution

The physical sequelae of torture include (Republic of South Africa, 1996) and the

pain - often chronic, disability and medical Refugee Act (Republic of South Africa,

conditions (Harlacher, Nordin, & Polatin, 1998) provide basic civil and political

2016; Jørgensen, Auning-Hansen, & Elklit, rights such as free basic healthcare,

2017; Patel, Kellezi, & Williams, 2014). access to education and employment to

The psychological consequences refugees and asylum seekers regardless

of torture are often viewed in terms of of nationality and legal status, in reality

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) these constitutional rights may be denied

and major depressive disorder (MDD) (Bandeira, 2013; Higson-Smith, 2013;

(Harlacher et al., 2016; Higson-Smith, Langa, 2013; Patel et al., 2014; Quiroga

2013). Lesser acknowledged psychological & Jaranson, 2005). Refugees and asylum

consequences include cognitive impairment, seekers experience high levels of crime

decreased functioning, sleep disturbances, and violence, xenophobia and exploitation

memory problems, attentional deficits and (Bandeira, Higson-Smith, Bantjes, & Polatin,

anger. Co-morbid psychiatric conditions 2010; Higson-Smith, 2013; Langa, 2013;

include depression, suicide, psychosis and Mohamed, Dix-Peek, & Kater, 2016), and

substance abuse (Bandeira, 2013; Quiroga, the South African asylum-seeking process

2017; Quiroga & Jaranson, 2005). has been associated with inconvenience,

The social consequences of torture cost and distress (Higson-Smith & Bro,

impact on the social wellbeing of the 2010; Langa, 2013). Continuing traumas

survivor. These effects include the loss of threaten the survival of many refugees and

“employment, status, family and identity” asylum seekers through ongoing threats

(Higson-Smith, 2013, p.165), separation from the police, government officials and

from loved ones (Higson-Smith, 2013; community members, and through domestic

Quiroga & Jaranson, 2005), the loss of violence, sexual violence and xenophobia

functioning and safety, and loss of cultural (Higson-Smith, 2013; Mohamed et al.,

and community connections (Higson- 2016). Such traumas “may influence the

Smith, 2013). way that survivors respond or adapt to

their precarious circumstances, but it is the

Living in contexts of continuing threat circumstances themselves that produce and

and daily stress maintain the client’s psychological state”

Vulnerability to mental health challenges (Higson-Smith, 2013, p. 166). Fear, anger

has been linked to pre-migratory exposure and distress, emotional collapse, helplessness

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

to war trauma and torture, the migration and hopelessness (Bandeira, 2013; Kaminer

process itself, and the post-migratory & Eagle, 2010) are associated with daily

stressors of host countries which include stressors of documentation problems,

poverty and inadequate housing, and concerns over the health and schooling of

difficulties with asylum procedures family members, accommodation problems,

(Bogic, Njoku, & Priebe, 2015; Buhmann, unemployment, poverty, loss of social and

Mortensen, Nordentoft, Ryberg, & material support, ostracism and lack of

Ekstrøm, 2015; Jaranson & Quiroga, security (Bandeira et al., 2010; Higson-

2011; Jørgensen et al., 2017; Stammel et Smith, Mulder, & Masitha, 2007; Miller &

al., 2017). Rasmussen, 2010).37

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Research on treatment approaches for and educational groups (Phaneth, Panha,

torture survivors Sopheap, Harlacher, & Polatin, 2014).

There are few scientific research studies Furthermore, the literature reviewed indicates

on the treatment of torture survivors as a strong prevalence of European and North

clinicians are inclined to prioritise direct American studies on the rehabilitation of

services to clients over research processes. torture survivors, with few outcome studies

Ethical concerns of differential treatment based in Africa. There is clear need for

of clients in control trials (Jaranson & scientific/ experimental research in this area

Quiroga, 2011; Stammel et al., 2017), the of work in an African context.

expense of scarce resources of rehabilitation

programmes (Bandeira, 2013), and The CSVR multi-modal framework for

generalisability of study results (Pérez-sales, the psychosocial rehabilitation of

Witcombe, & Otero Oyague, 2017) are individual survivors of torture

among the challenges of outcome studies. Given the dire contextual realities in which

The few experimental or quasi- many torture survivors live, research on

experimental designs on torture survivors the effectiveness of treatment frameworks

are usually affected by small sample sizes, needs to include psychological and social

the lack of control groups (Jaranson & health as consequences of torture (Patel,

Quiroga, 2011) and instruments with Kellezi, & Williams, 2014) in addition to the

limited validity and reliability often focused usual consequences of PTSD and MDD

only on improvement in PTSD and MDD (Bandeira, 2013; Higson-Smith, 2013).

(Jaranson & Quiroga, 2011). Meta-analyses Accordingly, the Centre for the Study

of randomised control trials illustrate of Violence and Reconciliation (CSVR)

improvements of generally small effect developed a multi-modal guiding framework

sizes in PTSD and depression when using for the rehabilitation of individual torture

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) survivors that takes into account their lived

and Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET), realities of continuing traumas and ongoing

with moderate improvement on follow-up daily stressors (Bandeira et al., 2013).

(Patel et al., 2014). However, exceptional The development of the multi-modal

experimental studies do exist, with substantial CSVR model, hereafter referred to as the

improvements found using the Common CSVR framework, was based on a literature

Elements Treatment Approach, compared search, analysis of intervention process notes

to the less effective Cognitive Processing of CSVR clinical staff, and a Delphi process

Therapy (Weiss et al., 2015). Quasi- for expert consensus on the most severe

T O RTU R E Vol u m e 2 8 , N um be r 1, 2 01 8

experimental and outcome research on the impacts of torture and the most appropriate

rehabilitation of torture survivors provides methods of torture intervention in a South

further support for CBT (Halvorsen & African context. There was consultation

Stenmark, 2010; Neuner et al., 2010) and between the research and clinical teams

NET (Dibaj, Overaas Halvorsen, Edward on the categorisation of the impacts, their

Ottesen Kennair, & Inge Stenmark, 2017; assessment and the most appropriate

Hansen, Hansen-Nord, Smier, Engelkes- intervention approaches. As a result, the

Heby, & Modvig, 2017), culturally tailored CSVR framework comprises the 18 most

health promotion intervention (Berkson, severe impacts of torture (14 after grouping

Tor, Mollica, Lavelle, & Cosenza, 2014) the impacts) in contexts such as those found38

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

in South Africa, and the most appropriate Given the reality of unsafe

intervention strategies associated with each circumstances, it may be appropriate that

(Table A - 1, numbered alphabetically per clients’ reactions include paranoia and

area). Aspects of trauma-focused CBT hypervigilance. The clinical approach

(TFCBT), NET, dialectical behavioural outlined in the framework uses reality

therapy, supportive therapy, problem solving testing, dealing with perceived threats,

and solution-focused therapy underpin safety planning, skills development

therapeutic interventions in the framework, and symptom management to assist

with an emphasis on empowerment. As such, clients to reduce repeated victimisation

the framework is considered to be multi- and increase their skills to ensure their

modal and informed by mutiple theories. continued safety.

Many centres adopt a multi-disciplinary, • Continuing traumas while dealing with

multi-modal, or “common-sense” approach past traumas and torture experiences:

to psychosocial interventions (Pérez-sales The framework provides guidelines

et al., 2017) in which the therapist chooses on how clinicians may help clients

from different modalities according to understand their reactions to past

the needs of the torture survivors. These traumas and how these reactions relate

approaches provide a more meaningful to their responses to the ongoing traumas

personalisation of the survivors’ needs, that may affect them.

which together with a clear therapeutic • Managing relationships with service

relationship and culturally tailored goals, providers, family members and

may be more appropriate than a rigid community members:

“one-size-fits-all” therapeutic model. The framework provides guidelines

While there are several multi-modal on how clinicians may assist clients to

treatment approaches for assisting torture deal with their emotional reactions to

survivors (Drozdek, 2015; Stammel et al., traumas, and to build the social capital

2017), the CSVR framework offers clearly necessary to maintain relationships and

articulated therapeutic guidance relevant obtain services, for example, medical and

to South African and developing contexts. legal assistance or documentation from

For example, it provides clear outlines the Department of Home Affairs.

for the role of clinicians in attending to

the therapeutic needs of clients, and for Research design

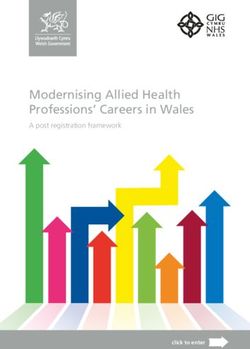

the “core business” of the CSVR clinical The design of the current research is

team, both essential therapeutic elements described as quasi-experimental. It

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

for maintaining therapeutic boundaries, comprises two groups of participants,

empowering clients and increasing their both groups observed over six months

resilience. Although it is assumed that what but differentiated according to when their

the client brings to therapy will be the participants approached the Centre, when

focus of the session, the CSVR framework they commenced treatment with the CSVR

provides guidelines on how to assist clients framework, and the duration of treatment

when certain needs arise, for example: based on the CSVR framework (Figure 1).

• Lack of safety, repeated victimisation The ‘treatment’ group comprised clients

and high levels of violence in a South who came for counselling between July 2014

African context: and December 2015 and were treated based39

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

on the CSVR framework for six months. The for the comparison group. Secondly, it was

‘comparison’ group comprised clients who hypothesised that there would be greater

came for counselling at the Centre between improvement in the psychological and

January and June 2014 and were placed on functioning measurements from T1 to T3 for

a 3-month ‘Waiting list’ condition before the treatment group than for the comparison

commencing three months of treatment group, as the treatment group received

based on the CSVR framework. treatment based on the CSVR framework

Psychological wellbeing and functioning for six months, while the comparison group

were measured three times: participants received this treatment for three months

in the treatment group were measured only following the 3-month waiting list

before the start of the CSVR intervention condition.

treatment (T1), three months after the start

of CSVR framework treatment (T2), and Methods

after a further three months of the CSVR Procedure

framework treatment (T3); participants in The treatment group received treatment

the comparison group were measured before based on the CSVR framework for six

the start of a 3-month waiting period (T1), months; the comparison group received an

at the end of the 3-month waiting period initial 3-month waiting condition before

(T2), and then three months after the start receiving treatment based on the CSVR

of the CSVR framework treatment (T3) (see framework for three months.

Figure 1). In the 3-month waiting condition, a

Written informed consent was obtained clear waiting list management took place. A

from all participants. Ethical clearance trained trauma professional phoned clients

was provided by an internal CSVR ethics in the comparison group every two weeks

committee as well as by external experts in to check that they still wanted to come

the violence and/or torture field, including a for counselling, and to refer clients for

lecturer at a Johannesburg-based university medical, legal and humanitarian assistance

and two partners working at international if necessary. This condition compared with

NGOs providing services to survivors of clients who went straight into treatment

torture. This approach to ethical clearance using the CSVR framework (see The

was necessary as there is no overarching CSVR multi-modal framework for the

national ethics body in South Africa, and psychosocial rehabilitation of individual

CSVR is not affiliated with a university. survivors of torture, on page 37).

Emergency cases in both groups (clients

T O RTU R E Vol u m e 2 8 , N um be r 1, 2 01 8

Hypotheses experiencing psychosis, who were suicidal

As the treatment group received specialised or other emergencies) were contained

counselling for the first three months and referred for psychiatric assistance at a

and the comparison group received less local hospital, or for medication from the

specialised communication (as part of the consultant psychiatrist at the CSVR.

waiting list protocol) for their first three Baseline measures were carried out

months, it was hypothesised that there using the same instrument at the start of the

would be greater improvement in the CSVR treatment condition of the treatment

psychological and functioning measurements group, and at the start of the waiting time

from T1 to T2 for the treatment group than condition of the comparison group (T1). A40

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

second set of measures was carried out three i.e. six months after commencement of the

months after commencement of the CSVR CSVR condition of the treatment group, and

condition of the treatment group, and three three months after commencement of the

months after the start of the waiting time CSVR condition of the comparison group

condition of the comparison group (T2). A (T3) - see Figure 1.

third set of measures was carried out three Every two weeks, clinicians participated

months after the second set of measures, in supervision sessions which focused

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

Figure 1: Study procedure41

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

both on fidelity to the framework as well (waiting list) baseline (T1), were included in

as guidance with therapeutic concerns. the waiting list group, and had also

Supervisors ensured that clinicians followed completed a treatment baseline (T2). At T3,

the framework and concurrently documented 16 participants from this group remained,

which aspects of the framework were utilised having completed the waiting list baseline,

using a fidelity checklist. Any difficulties with treatment baseline and 3-month follow-up

the implementation of the framework were assessment, and these 16 were included in

discussed with the researchers and indicated the follow-up study (Figure 1).

in the fidelity checklist. Assessment measures: The assessment

tools used for all clients at T1, T2 and T3

Participants included the Harvard Trauma

All participants were selected according Questionnaire (HTQ) measuring

to the 1985 UNCAT definition of torture posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),

(United Nations General Assembly, 1985) clients’ self-perception of functioning and

and were over 18 years old. No substantial overall trauma (Harvard Program in

historical events were noted for the 6-month Refugee Trauma, 1992), the Hospital

period that separated the groups. Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

Participants in the treatment group: The measuring anxiety and depression

participants in the treatment group were (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983), the De Jong

selected from clients who approached the Gierveld Loneliness Scale measuring

CSVR between 1 July 2014 and 30 December clients’ emotional loneliness and social

2015. Over this period, 197 clients were loneliness (de Jong Gierveld & Van Tilburg,

screened, and 24 clients excluded based on the 2006), the number of areas of pain in the

UN torture definition, and a further 129 body,2 and management of aspects of

clients excluded due to incomplete T1 or T2 functioning.3 Reliability measures are

outcome measures. Thus 44 clients had presented in Table A - 2.4

completed both their baseline assessment and a All assessments were administered by

three-month follow-up and were included in trained psychologists or social workers.

the treatment group. Of this group, 20 Translation through interpretation was

completed their six-month follow-up and were

included in the follow-up study (Figure 1).

Participants in the comparison group: The 2

The total number of areas of pain was based on

participants in the comparison group were the areas of pain in the body pointed out or indi-

selected from clients who approached the cated verbally.

T O RTU R E Vol u m e 2 8 , N um be r 1, 2 01 8

3

For management of aspects of functioning, four

CSVR from January to June 2014. Over this

Likert-type scaled questions were adapted from

period, 87 clients were screened, 66 of whom the International Classification of Pain and

met the inclusion criteria for the waiting list Disability (ICF) (WHO, 2001): Family-related

group, with 21 excluded as they had not stressors, External stressors (excluding family-

related stressors), Managing situations that made

experienced torture according to the UN

the client angry, and Psychological or emotional

torture definition. A further 28 clients were functioning. Scale responses ranged from manag-

then excluded as they had not completed a ing very poorly, to managing very well.

follow-up assessment, leaving 38 clients as

4

As Cronbach’s coefficient α is correlated with the

number of items in the scale, average inter-item

participants in the comparison group. These

correlations are also presented as their values are

38 clients had completed a comparison independent of scale length (Table A - 2).42

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

provided to clients in the main languages of Finally, post hoc analyses were used

clients who come to the clinic. These include to examine the effects of the higher than

French, Swahili, Amharic, Somali and expected attrition rate of respondents of the

Lingala. All interpreters were trained on the two groups who dropped out of the study

assessment tools. after T2, i.e. during the 3-month counselling

Analysis methods: Initially the baseline period between T2 and T3. This comparison

(T1) psychological and functioning was deemed necessary to examine whether

measurement means of the treatment and a systematic bias may have been added to

comparison groups were compared using the data at T3, should the participants who

t tests and Cohen’s d effect sizes, and left the comparison group after T2 differ

categorical variables compared via the Chi from the participants who left the treatment

square test. Thereafter the mean changes group after T2. Such a situation would bias

of the two groups were compared for the the samples and the results of the T1-T3

first three months (T1 to T2) and then comparison relevant to the second hypothesis.

for the six month period (T1 to T3) via This analysis was a simple examination of

mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA).5 In the demographics, as well as of the direction

both cases, the ANOVA interaction effects of the mean differences for each scale from

were examined for evidence of a significant T1 to T2 for the participants in each group

differential pattern in the mean scores across who dropped out after T2. No other post hoc

the time periods depending on the group, analyses on the results are presented.

and partial eta-squared effect sizes were used

as measures of the strength of differences. Results

Where necessary, the Scheffé post hoc test Table 1 shows details of the participant

was used to locate significant differences characteristics for both groups.

between means. In view of the multiple Approximately half of the participants were

violations of the assumptions of the mixed male, fewer than 10% were South Africans,

ANOVA analyses, the conservative non- and the dominant groups were from Congo

parametric Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was (DRC), Ethiopia and Somalia. Over half

used on the separate groups. In addition, the were living with a partner, spouse, family

odds ratio was used to indicate effect sizes member or friend, approximately 80% were

for the individual groups, and for assessing either asylum seekers or refugees, and fewer

the odds of improvement in the treatment than half of the participants of each group

group relative to the comparison group.6 had experienced torture within the past year

in each group (a third of the comparison

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

versus 39% of the treatment group). Before

5

Ideally, mixed multivariate Analyses of Variance the torture, 5% or fewer were unemployed

(MANOVA) would be computed on the compo- whereas approximately three-quarters or

nents of the scales to detect multivariate response more were unemployed at the start of the

patterns, while controlling the family-wise Type 1

study. The ages of the participants ranged

error rate with greater power to detect differences.

However, the sample sizes were small, and in all from 18 to 72 years, with mean age in the

instances, assumption violations of the multivari- mid-thirties (M=36.20 years, SD=10.35

ate analyses mitigated against the MANOVA tests. years for the treatment group, and M=34.82

6

This exploratory approach was undertaken whilst

years, SD=8.68 years for the comparison

recognising that the family-wise Type 1 error in-

creases with multiple statistical tests. group). The treatment group had a higher43

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Table 1: Demographics of treatment and comparison groups

Treatment Comparison

Demographics

group (n=44) group (n=38)

n % n % p^

Gender Female 22 50% 16 42% 0.47

Male 22 50% 22 58%

Nationality Burundi 2 5% 1 3% 0.98

Congolese (DRC) 15 34% 13 34%

Eritrean 0 0% 4 11%

Ethiopian 8 18% 13 34%

Somali 12 27% 3 8%

South African 1 2% 3 8%

Zimbabwean 2 5% 0 0%

Other * 4 9% 1 3%

Marital status Currently married 24 55% 8 21% 0.01

Divorced/separated 3 7% 4 11%

Never married 13 30% 18 47%

Widowed 4 9% 7 18%

Missing 0 0% 1 3%

Currently living Living alone/strangers/shelter 14 32% 7 19% 0.14

Living with family/ children 16 36% 5 13%

Living with friends 7 16% 10 26%

Living with spouse/ partner 4 9% 4 11%

Other 0 0% 4 11%

Missing 3 7% 8 21%

Legal SA status Asylum seeker/ refugee 37 84% 30 79% 0.78

Citizen 2 5% 3 8%

Undocumented 4 9% 1 3%

Missing 1 2% 4 11%

Pre-torture employment Minor/ student 5 11% 5 13% 0.83

Unskilled labour/ semi-skilled 22 50% 21 56%

T O RTU R E Vol u m e 2 8 , N um be r 1, 2 01 8

Skilled/ professional 14 32% 10 26%

Unemployed 2 5% 1 3%

Missing 1 2% 1 3%

Current employment Minor/ student 0 0% 2 5% 0.39

Unskilled labour/ semi-skilled 8 18% 3 8%

Skilled/ professional 3 7% 2 6%

Unemployed 32 73% 31 82%

Missing 1 2% 0 0%44

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Treatment Comparison

Demographics

group (n=44) group (n=38)

n % n % p^

Education No schooling 4 9% 1 3%45

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Table 2: Trauma types experienced by respondents of the comparison and treatment groups

Treatment group Comparison group Odds ratio: Treatment/

(n=44) (n=38) Comparison

OR Fisher exact

n % n % test

(p)

Torture/ CIDT 44 100% 38 100% - -

Witness to trauma 31 70% 30 79% 0.64 0.27

Assault 25 57% 28 74% 0.47 0.09

Bereavement/ traumatic bereavement 16 36% 21 55% 0.46 0.07

Armed robbery 18 41% 18 47% 0.77 0.36

Xenophobia 12 27% 17 45% 0.46 0.08

Mugging 5 11% 13 34% 0.25 0.02

War 15 34% 13 34% 0.99 0.59

Hostage/ kidnapping/ abduction 9 20% 8 21% 0.96 0.58

Rape/ attempted rape/ sodomy 14 32% 6 16% 2.49 0.08

Motor vehicle accident 2 5% 5 13% 0.31 0.16

Hijacking 5 11% 5 13% 0.85 0.53

Relationship/ domestic violence 2 5% 5 13% 0.31 0.16

that three of the four initial coping or Comparison of the changes in the psychological

managing scores of the treatment group and functioning measures across the first three

are significantly better than those of the months (T1 to T2) for each group: Based on

comparison group, and the PTSD, trauma, the direction of the differences between each

anxiety and depression scores are lower of the T1-T2 pairwise means for the

(α=.05). The effect sizes of these differences treatment and the comparison groups

are moderately large (Cohen’s d with considered separately, all 13 of the pairwise

magnitude at least .5), with the exception differences of the treatment group are in the

of the strong difference in depression scores ideal direction of improved psychological

of the two groups (t(79)=3.36, p46

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

assumption violations for the T1 or T2 scores 2.61 for anxiety means that the clients in

of 7 of the 13 ANOVA comparisons, the the treatment group reduced their anxiety

T1-T2 comparisons of the separate groups 2.61 times more than the clients in the

were re-examined using the conservative comparison group did.

non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-ranks test There thus appears to be partial support

with Z score conversion for large sample for the expectation of greater improvement

sizes and asymptotic significance, and the in psychological health and functioning

odds ratio (OR) used to indicate effect size from T1 to T2 for the treatment group

(Table 3). relative to the comparison group. We

The Wilcoxon results of the treatment therefore conclude, conservatively, that

group show seven significance changes there is insufficient statistical evidence

(emotional and total loneliness, external for overall support of the first hypothesis

stressors, functioning, trauma, anxiety and of the research and we instead discuss

areas of pain), all with odds ratios greater the significant T1-T2 differences on the

than 1 (Table 3). By contrast, there are two individual indicators, specifically differences

significant T1-T2 differences (depression on the indicators of functioning and anxiety.

and areas of pain) in the comparison Comparison of the changes in the

group. For the treatment group, the odds of psychological and functioning measures across

improvement relative to non-improvement the three time periods (T1-T3) for each group:

are greater (odds > 1) for 9 of the indicators The comparisons from T1 to T3 are based

of psychological health and functioning, on substantially reduced sample sizes owing

compared to 5 indicators for the comparison to attrition of participants in the two groups

group. Furthermore, ratios of the odds after the second set of measures. Under half

for the treatment group relative to the the respondents remained after T2 (45% or

comparison group computed per indicator 20 of the 44 participants in the treatment

variable show OR values greater than 1 group, and 42% or 16 of the 38 participants

for most indicators (emotional and total in the comparison group).

loneliness, the coping indicators of external Based on the mixed ANOVA tests, there

stressors and psychological difficulties, the is no evidence of significant interaction

HTQ scales of PTSD, functioning and effects that would show a difference in the

trauma, the HADS anxiety scale, and areas changes of scores over time depending on

of pain - Table 3). Thus, for these indicators, the group, and the magnitude of all effect

members in the treatment group improved sizes, as measured by partial eta squared

their psychological health and functioning values, are negligible to weak. However,

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

from T1-T2 more than members in the significant main effects across time, in the

comparison group did. However, based on direction of increased psychological health

the Fisher Exact Probability test (1-tailed, and functioning, were found for coping

α=.05), the odds ratios are only significant with anger, the HTQ, the HADS, as well as

for the HTQ functioning scale and for the for number of areas of pain. In particular,

HADS anxiety scale. The OR value of 2.49 based on post hoc Scheffé comparisons,

for functioning means that the clients in the measures of self-perception of functioning,

treatment group improved their functioning depression and number of areas of pain

2.49 times more than the clients in the improved significantly from one time to the

comparison group did; the OR value of next. As for the T1-T2 comparisons, the47

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Table 3: Wilcoxon signed-rank test and odds ratio effect sizes for T1-T2 repeated measures for

treatment and comparison groups

Odds ratio:

Treatment group Comparison group

Treatment/

(n=44) (n=38)

Comparison

Indicators

Fisher

Odds Odds exact

Z p^ Z p^ OR

^^ ^^ test

(p)

Connection to Emotional 2.06 0.04 * 1.32 0.10 0.92 1.06 1.25 0.40

others loneliness

Social loneliness 0.98 0.33 1.16 0.13 0.89 1.24 0.94 0.53

Total loneliness 2.11 0.03 * 1.29 0.03 0.98 1.09 1.18 0.44

Coping or Angry situation 1.43 0.15 0.83 0.49 0.63 0.84 0.98 0.58

managing

Family related 0.59 0.56 0.67 1.59 0.11 0.87 0.77 0.38

stressors

External stressors 2.06 0.04 * 1.06 0.07 0.94 0.69 1.54 0.23

Psychological 1.34 0.18 0.97 0.58 0.56 0.79 1.23 0.42

difficulties

Harvard PTSD 1.70 0.09 1.21 0.27 0.79 1.10 1.10 0.52

trauma

questionnaire Functioning 2.57 0.01 * 1.71 0.39 0.69 0.68 2.49 0.04 *

Trauma 2.28 0.02 * 1.56 0.02 0.99 0.79 1.97 0.10

Hospital Anxiety 2.83 0.01 ** 1.56 0.48 0.63 0.60 2.61 0.04 *

anxiety and

depression Depression 0.99 0.32 0.87 3.17 0.01 ** 1.79 0.49 0.10

scale

Pain Number of areas 2.44 0.01 * 1.23 2.26 0.02 * 0.94 1.31 0.36

of pain

T O RTU R E Vol u m e 2 8 , N um be r 1, 2 01 8

* p < .05; ** p < .01

^ denotes the asymptotic significance value (2-tailed) for Wilcoxon Z for large samples

^^ tied changes were randomly distributed in equal proportions to positive and negative changes, rendering the

odds ratio more conservative than the Z score

T1-T3 comparisons were re-examined using psychological health and functioning,

the conservative non-parametric Wilcoxon exceptions being social loneliness and

signed-ranks test on the separate groups, coping with external stressors. However,

owing to violations of ANOVA assumptions. counter-intuitively, the results of the

For both groups, most of the outcome Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests on the T1-T3

means changed in the direction of improved comparisons computed on the separate48

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

groups revealed more significant T1-T3 In Table 4, the means for each scale

improvements for the comparison group are presented for those members of the

than for the treatment group. For the treatment group and the comparison group

comparison group, 7 of the 13 outcome who left the programme after the second set

measures improved significantly from T1 of measures.9 The outcome measures with

to T3 (α=.05), (coping with anger, the T1-T2 changes in the direction of improved

HTQ measures of PTSD, functioning and psychological health and functioning are

trauma, the HADS measures of anxiety and indicated with a tick ().10

depression, and areas of pain), compared to The members of the treatment group

only 1 of the 13 outcome measures (areas of who left the programme after T2 had

pain) for the treatment group. Nevertheless, improved their mean scores on all 13

none of the odds ratios computed via measures at T2. By contrast, the members

the ratio of odds for the treatment and of the comparison group who left the

comparison groups per indicator variable programme after T2 had improved their

are significant based on the Fisher mean scores on fewer than half (6 out of 13)

Exact Probability test (α=.05). Thus, of the measures (social and total loneliness,

although there are more significant T1-T3 family related stressors, psychological

improvements in the comparison group difficulties, depression and areas of pain),

than in the treatment group, the magnitude a significant difference in percentages

of these improvements is not sufficient to (p=.002). Thus, participants in the treatment

render the odds of the improvements in group who left the programme at T2 had

the comparison group significantly greater improved their overall psychological health

than the odds of the improvements in the and functioning, whereas the participants

treatment group. in the comparison group who left the

However, the counter-intuitive Wilcoxon programme at T2 had not shown this

test results on the T1-T3 comparisons, overall level of improvement. After T2,

whatever their magnitude, need to be the treatment group appears to have been

addressed. A possible explanation is weakened by the loss of members who

presented in a post hoc set of comparisons had improved health after three months,

using a basic analysis of attrition after T2. while the comparison group had not lost

Comparison of participants in each group overall improvers. This differential pattern

who dropped out after T2: Based on the of attrition between the groups may explain

Chi square test for between-group the counter-intuitive findings of greater

comparisons, there is no evidence of improvement from T1-T3 of the remaining

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

significant differences in the demographic members of the comparison group

characteristics of participants who compared to the remaining members of the

dropped out of the treatment group after treatment group.

T2 versus those who dropped out of the

comparison group after T2. However,

comparison of the T1-T2 changes in the 9

As tests of significance are reserved for a future

psychological health and functioning in-depth article on attrition, this analysis does

measures of these two groups suggests not indicate significance or effect size.

10

In each comparison, the direction of the means is

that there may be a differential pattern of

based on the difference in the pairwise means of

attrition between the groups. individuals.49

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Table 4: Mean scores from T1-T2 of participants who left the comparison and treatment groups

after T2

Participants who left after T2:

those who left from those who left from

the treatment group the comparison

(n=24) group (n=22)

Indicators Mean T1-T2 Mean T1-T2

T1 2.83 ü 2.48

Emotional loneliness T2 2.52 2.50

Connection to T1 2.87 ü 2.52 ü

Social loneliness T2 2.75 2.32

others

T1 5.70 ü 5.00 ü

Total loneliness T2 5.17 4.82

T1 2.61 ü 2.14

Angry situation T2 2.67 2.00

T1 2.23 ü 1.60 ü

Family related stressors T2 2.43 2.21

Coping or

managing T1 1.87 ü 1.90

External stressors T2 2.33 1.86

T1 2.35 ü 2.10 ü

Psychological difficulties T2 2.74 2.24

T1 2.54 ü 2.76

PTSD T2 2.33 2.91

Harvard T1 2.48 ü 2.60

trauma Functioning T2 2.25 2.82

questionnaire

T1 2.50 ü 2.67

T O RTU R E Vol u m e 2 8 , N um be r 1, 2 01 8

Trauma T2 2.28 2.83

T1 1.71 ü 1.86

Hospital Anxiety T2 1.31 1.89

anxiety and

depression T1 1.57 ü 1.89 ü

scale Depression T2 1.28 1.63

T1 1.96 ü 3.23 ü

Pain Areas of pain T2 1.83 2.3250

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Discussion assumptions required for parametric

The research was designed to test the statistical analyses. Attrition created a

efficacy of the CSVR psychosocial further problematic effect in our study as

intervention framework using a sample of the treatment group clients who dropped

torture survivors, almost all of whom were out of the study after T2 showed greater

asylum seekers, refugees and undocumented overall improvement in their psychological

persons in a South African environment health and coping from T1 to T2 than the

filled with daily stressors and continuing comparison group clients who dropped

traumas. These individuals were found to out of the study after T2. This differential

have clinical baseline scores on PTSD, attrition effect may have biased the longer-

depression, anxiety and low levels of term comparison of the mean scores

functioning, which may be explained, at from T1 to T3 (the second hypothesis of

least in part, by their history of torture the study), creating paradoxical results.

which severely impacts psychological and Thus, our main finding pertaining to the

psychiatric wellbeing (Bandeira et al., 2010; hypotheses on the efficacy of the CSVR

Higson-Smith, 2013; McColl et al., 2010; framework is that we have not found

Patel et al., 2014; Quiroga & Jaranson, sufficient evidence to warrant the efficacy

2005). The CSVR framework is designed of the framework, owing mainly to several

to address the complexity of the past severe challenges inherent in research of this

traumas exacerbated by contextual realities nature. It may be fairer to conclude that

of a hostile South African environment the research results on the efficacy of the

(Bandeira, 2013; Bandeira et al., 2013). framework are inconclusive.

However, there are several interesting

Efficacy of the CSVR framework results in the research. Firstly, improvement

The assessment of the efficacy of the CSVR in the psychological wellbeing and

framework was based on the expectation functioning of the clients of both groups

of a long-term differential effect when an from T1 to T3 occurred despite the context

initial three-month waiting list condition of the lack of safety and continuing daily

was included, compared to when clients traumas of the torture survivor clients.

entered straight into treatment. The findings This result is consistent with the CSVR

of the research did not provide clear support framework’s prioritisation of empowerment,

for the hypotheses of greater improvement problem solving and trauma-related therapy.

in the psychological health and coping Secondly, after three months of treatment

indicators of the CSVR treatment group under the CSVR framework, there are

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

than the waiting list comparison group. indications of clients’ improved connection

However, the results are complex and less to others. This result is encouraging within

than clear. the inherent mistrust, isolation and fear

The data gathered reflect the challenges as consequences of torture (Quiroga

of attempting rigorous quasi-experimental & Jaranson, 2005). Building trusting

quantitative research in the context of relationships after a torture experience

torture, using established measurement should be viewed as a long-term therapeutic

scales that were found to have lower than goal (as per the approach of the CSVR),

desirable reliability for our sample, and as torture often results in the annihilation

data that do not meet all the stringent of interpersonal trust (Bandeira, 2013;51

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Bandeira et al., 2013). Further research is CSVR treatment framework for the two

warranted on the prioritisation of a family groups, we found that the psychological

and group model or framework in the South health and functioning of members of the

African context to mitigate the isolation felt treatment group was somewhat better than

by the torture survivor, and the best way to that of the comparison group at baseline

reintegrate the torture survivor into trusting testing. The groups also differed on marital

familial, group and community relationships. status and education levels.

Thirdly, after three months in therapy, In addition to these baseline differences

clients appear to deal better with their past between the groups, the nature of the

traumas and torture experiences in the comparison group condition, i.e. the

context of unsafe situations, specifically in waiting list protocol, was not a true placebo

terms of increased functioning and reduced comparison as it offered a level of support

anxiety levels. to clients in the comparison group. The

We move now to discuss the main comparison group clients received support in

challenges of scientific research on trauma, telephone calls every second week, referrals

based on the lessons of this study. offered for legal, medical or humanitarian aid,

and assistance offered if they were psychotic,

Challenges of research on trauma rehabilitation suicidal or required other emergency

It is essential to conduct thorough research assistance. After three months of receiving

on the outcomes of torture rehabilitation this level of support, these waiting list clients

programmes that could improve the quality may well have felt somewhat better on a

of the services and care to torture survivors, psychological and functioning level than they

contribute to professional development in had at baseline. Indeed, the results of the

the field, and empower torture survivors comparison group clients showed significant

(Jaranson & Quiroga, 2011). Although improvement in their depression scores.

quantitative studies involving the principles However, despite the possible confounding

of randomised experimental design, sound effect of the waiting list condition, it is

sampling techniques, objective measures and an ethical necessity in the context of the

rigid statistical analysis are scientific ideals, vulnerability of torture survivors.

such criteria are, in reality, unattainable High levels of overall attrition are

in the complex and challenging world of expected in this population due to the

torture rehabilitation with its thorny ethical transient nature of tortured refugees in

considerations and limitations. Ethical South Africa who often need to move

compliance precludes randomised control to find employment or accommodation,

T O RTU R E Vol u m e 2 8 , N um be r 1, 2 01 8

group designs; instead, researchers of torture or due to safety concerns. Furthermore,

attempting scientific studies are restricted to many refugees and asylum seekers use the

quasi-experimental or outcome designs with CSVR for introduction to legal, medical

compromised internal validity. or humanitarian aid, and then terminate

We present the consequences of these contact with the centre. Although previous

research design restrictions in our research. CSVR reports indicate an attrition rate of

Although there was no apparent reason 21-44% of clients annually (Dix-Peek, 2012a,

for the groups to differ at baseline, and no 2012b), the current research indicates a

outstanding historical events occurring in much higher rate (75% or 129 of 173 clients

the time interval between the start of the in the treatment group, and 42% or 28 of52

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

66 clients in the comparison group).11 The who improved their health may be evidence

high rate of attrition from screening to T1, of the preliminary success of the CSVR

referred to here as overall attrition, for both framework, although the sustainability of the

groups, but particularly for the treatment improvement is unknown.

group, is a clear limitation of the current The topic of attrition is planned as part

research. Contextual challenges of staffing of a future journal article.

changes within CSVR may have contributed

to clients not completing their baseline T1 or Conclusion

follow-up T2 assessments and the consequent The CSVR psychosocial framework for the

stark overall attrition for the treatment rehabilitation of torture survivors provides a

group. CSVR has attempted to mitigate the set of therapeutic guidelines in the context

high overall attrition through ensuring that of daily stressors, continuing traumas,

clients receive transport money to and from past torture and trauma events. It is also a

the office, conducting drop-out reports for framework designed for developing country

a better understanding of why clients stop settings where survivors live with lack of

coming for counselling, providing ongoing safety and extreme socio-economic concerns.

training with CSVR clinicians and monitoring Thus evidence-based research on the

and evaluation staff, and ensuring adherence efficacy of this framework is essential as a

to the monitoring and evaluation system. first step towards investigating its legitimacy

The high rate of attrition of clients after as “best practice” for torture survivors in

the initial three months of the programme developing countries. However, conducting

is also of great concern for the CSVR such research is often not prioritised due

rehabilitation endeavours as over half of to scarce financial and human resources,

the clients left the study after T2 (55% of practitioners who may not recognise the

the treatment group members and 58% need to prioritise outcome research over the

of the comparison group members). A “core” therapeutic and psychosocial work

rudimentary post hoc attrition analysis of the (Bandeira, 2013; Montgomery & Patel,

means of the outcome measures suggests 2011), attrition and small samples sizes,

that different patterns of attrition in the limited academic and research expertise,

comparison and treatment groups may and ethical concerns (Jaranson & Quiroga,

explain the counter-intuitive results from 2011). Our study has aimed to contribute to

T1-T3. The comparison group clients who a detailed understanding of the intricacies

left the programme at T2 showed limited and challenges of undertaking psychosocial

improvement in their psychological health research in the torture field. It highlights

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

and functioning, while the treatment group the serious problem of attrition and offers

clients who left the programme at T2 several lessons for future studies.

showed improvement on all indicators. While

attrition of participants was not planned, References

losing participants from the treatment group Amnesty International. (2014). Torture in 2014: 30

years of broken promises.

Baird, E., Williams, A. C. de C., Hearn, L., &

Amris, K. (2016). Interventions for treating

persistent pain in survivors of torture. Cochrane

11

These numbers exclude clients who were ex- Database of Systematic Reviews, (1). http://doi.

cluded as they were not tortured according to the org/10.1002/14651858.CD012051

UNCAT definition of torture.53

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Bandeira, M. (2013). Developing an African Torture evaluation of combined narrative exposure

Rehabilitation Model: A contextually-informed, therapy and physiotherapy for comorbid PTSD

evidence-based psychosocial model for the and chronic pain in torture survivors. Torture,

rehabilitation of victims of torture. Part 1. Setting 27(1), 13–27.

the foundations of an African Torture Rehabilitation Dix-Peek, D. (2012a). Profiling torture II: Addressing

Model through research. Johannesburg: Centre for torture and its consequences in South Africa: Towards

the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. accessible, effective and holistic rehabilitation

Bandeira, M., Garcia, M., Kekana, B., Naicker, services for victims of torture in Southern Africa.

P., Uwizeye, G., Smith, E., & Laveta, V. Monitoring and Evaluation progress report January

(2013). Developing an African Torture Model: A to December 2012. Johannes: Unpublished report

contextually-informed, evidence based psychosocial by the Centre for the Study of Violence and

model for the rehabilitation of victims of torture. Reconciliation.

Part 2: Detailing an African Torture Rehabilitation Dix-Peek, D. (2012b). Profiling torture II: Addressing

Model through engagement with the clinical team. torture and its consequences in South Africa.

Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence Monitoring and Evaluation Report: 2009-2011.

and Reconciliation. Johannesburg: Unpublished report by the Centre

Bandeira, M., Higson-Smith, C., Bantjes, M., & for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation.

Polatin, P. (2010). The land of milk and honey: Drozdek, B. (2015). Challenges in treatment of

a picture of refugee torture survivors presenting posttraumatic stress disorder in refugees: towards

for treatment in a South African trauma centre. integration of evidence-based treatments with

Torture, 20(2), 92–103. contextual and culture-sensitive perspectives.

Bantjes, M., Langa, M., & Jensen, S. (2012). Finding European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(24750).

our way: Developing a community model for http://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v6.24759

addressing torture. Johannesburg: Unpublished Halvorsen, J., & Stenmark, H. (2010). Narrative

report by the Centre for the Study of Violence Exposure Therapy for posttraumatic stress

and Reconciliation. disorder in tortured refugees: A preliminary

Başoğlu, M. (2009). A multivariate contextual uncontrolled trial. Scandinavian Journal of

analysis of torture and cruel, inhuman, and Psychology, 495–502.

degrading treatments: Implications for an Hansen, A. K. V., Hansen-Nord, N. S., Smier, I.,

evidence-based definition of torture. American Engelkes-Heby, L., & Modvig, J. (2017). Impact of

Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(2), 135–145. http:// Narrative Exposure Therapy on torture survivors in

doi.org/10.1037/a0015681 the MENA region. Torture, 27(3), 49–63.

Berkson, S. Y., Tor, S., Mollica, R., Lavelle, J., & Harlacher, U., Nordin, L., & Polatin, P. (2016).

Cosenza, C. (2014). An innovative model of Torture survivors’ symptom load compared to

culturally tailored health promotion groups for chronic pain and psychiatric in-patients. Torture,

Cambodian survivors of torture. Torture Journal, 26(2), 74–84.

24(1), 1–16. http://doi.org/2012-14 [pii] Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma. (1992).

Bogic, M., Njoku, A., & Priebe, S. (2015). Long- Measuring trauma, measuring torture: Healing the

term mental health of war-refugees: a systematic wounds of mass violence. Harvard.

literature review. BMC International Health Higson-Smith, C. (2013). Counseling torture

and Human Rights, 15(29), 2–41. http://doi. survivors in contexts of ongoing threat:

org/10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9 Narratives from sub-Saharan Africa. Peace and

Buhmann, C., Mortensen, E. L., Nordentoft, M., Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 164–

T O RTU R E Vol u m e 2 8 , N um be r 1, 2 01 8

Ryberg, J., & Ekstrøm, M. (2015). Follow-up 179. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0032531

study of the treatment outcomes at a psychiatric Higson-Smith, C., & Bro, F. (2010). Tortured

trauma clinic for refugees. Torture, 25(1), 1–16. exiles on the streets: a research agenda

Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ and methodological challenge. Intervention,

pubmed/26021344 8(1), 14–28. http://doi.org/10.1097/

de Jong Gierveld, J., & Van Tilburg, T. (2006). A WTF.0b013e3283387948

6-Item Scale for Overall, Emotional, and Social Higson-Smith, C., Mulder, B., & Masitha, S. (2007).

Loneliness: Confirmatory Tests on Survey Data. Human dignity has no nationality: A situational

Research on Aging, 28(5), 582–598. http://doi. analysis of the health needs of exiled torture

org/10.1177/0164027506289723 survivors living in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Dibaj, I., Overaas Halvorsen, J., Edward Ottesen Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence

Kennair, L., & Inge Stenmark, H. (2017). An and Reconciliation.54

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Jaranson, J. M., & Quiroga, J. (2011). Evaluating Syst Rev, (11). http://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.

the services of torture rehabilitation CD009317.pub2.Copyright

programmes: History and recommendations. Patel, N., Kellezi, B., & Williams, A. C. de C.

Torture, 21(2), 98–140. (2014). Psychological, social and welfare

Jørgensen, S. F., Auning-Hansen, M. A., & Elklit, A. interventions for psychological health and

(2017). Can disability predict treatment outcome well-being of torture survivors. The Cochrane

among traumatized refugees? Torture, 27, 12–26. Database of Systematic Reviews, 11(11). http://doi.

Kaminer, D., & Eagle, G. (2010). Traumatic stress org/10.1002/14651858.CD009317.pub2

in South Africa (1st ed.). Johannesburg: Wits Pérez-sales, P., Witcombe, N., & Otero Oyague, D.

University Press. (2017). Rehabilitation of torture survivors and

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practices of structural prevention of torture: Priorities for research

equation modeling (3rd Ed). New York: The through a modified Delphi Study. Torture,

Guilford Press. 27(3), 3–48.

Langa, M. (2013). Exploring experiences of torture Phaneth, S., Panha, P., Sopheap, T., Harlacher, U.,

and CIDT that occurred in South Africa & Polatin, P. (2014). Education as treatment for

amongst Non- Nationals living in Johannesburg. chronic pain in survivors of torture and other

Johannesburg: Centre for the Study of Violence violent events in Cambodia: Experiences with

and Reconciliation. implementation of a group-based “pain school”

McColl, H., Higson-Smith, C., Gjerding, S., Omar, and evaluation of its effect in a pilot study.

M. H., Rahman, B. A., Hamed, M., El Dawla, Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 19(1),

AS., Fredericks, M., Paulsen, N., Shabalala, 53–69. http://doi.org/10.1111/jabr.12015

G., Low-Shang, C., Valadez Perez, F., Colin, Quiroga, J. (2017). Comment 1: Torture as a chronic

LS., Hernandez, AD., Lavaire, E., Zuñiga, disease. Torture, 27(3), 38–40.

APA., Calidonio, L., Martinez, CL., & Jamei, Quiroga, J., & Jaranson, J. (2005). Politically-

YJ. Awad, Z. (2010). Rehabilitation of torture motivated torture and its survivors. Torture,

survivors in five countries: common themes and 16(2–3), 1–112.

challenges. International Journal of Mental Health Republic of South Africa. (1996). The Consitution of

Systems, 4, 16. http://doi.org/10.1186/1752- the Republic of South Africa. Pretoria.

4458-4-16 Republic of South Africa. (1998). South African

Miller, K. E., & Rasmussen, A. (2010). War refugee Act. Cape Town.

exposure, daily stressors, and mental health Stammel, N., Knaevelsrud, C., Schock, K., Walther, L.

in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging C. S., Wenk-Ansohn, M., & Böttche, M. (2017).

the divide between trauma-focused and Multidisciplinary treatment for traumatized

psychosocial frameworks. Social Science and refugees in a naturalistic setting: symptom

Medicine, 70(1), 7–16. http://doi.org/10.1016/j. courses and predictors. European Journal of

socscimed.2009.09.029 Psychotraumatology, 8(sup2). http://doi.org/http://

Mohamed, S., Dix-Peek, D., & Kater, A. (2016). dx.doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1377552

The psychological survival of a refugee in South UNHCR. (2015). Mid-year trends 2015. New York:

Africa — the impact of war and the on-going United Nations.

challenge to survive as a refugee in South Africa United Nations General Assembly. (1985). United

on mental health and resilience. International Nations Convention against Torture and other

Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 18(4), 1–11. Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment.

Montgomery, E., & Patel, N. (2011). Torture March 16, 2016.

T O RTU R E Vo lu m e 2 8 , Nu m be r 1 , 2 0 1 8

rehabilitation: Reflections on treatment outcome Weiss, WM., Murray, LK., Zangana, GA.,

studies. Torture, 21(2), 141–145. Mahmooth, Z., Kaysen, D., Dorsey, S., Lindgren,

Neuner, F., Kurrek, S., Ruf, M., Odenwald, M., K., Gross, A., McIvor Murray, S., Bass, JK.,

Elbert, T., & Schauer, M. (2010). Can asylum- & Bolton, P. (2015). Community-based mental

seekers with post-traumatic stress disorder be health treatments for survivors of torture and

successfully treated? A randomised controlled pilot militant attacks in Southern Iraq: a randomised

study. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 39(3), 81–91. control trial. BMC Psychiatry, 249–265.

Patel, N., Kellezi, B., & Williams, A. (2014). WHO. (2001). International Classification of

Psychological, social and welfare interventions functioning, disability and health. Geneva.

for psychological health and well-being of torture Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, P. (1983). Hospital

survivors SO-: Cochrane Database of Systematic Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica

Reviews YR-: 2014 NO-: 11. Cochrane Database Scandinavica, 67, 361–370.You can also read