Evaluation of hydrated lime as a cubicle bedding material on the microbial count on teat skin and new intramammary infection

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research 52: 159–171, 2013

Evaluation of hydrated lime as a cubicle bedding

material on the microbial count on teat skin

and new intramammary infection

D. Gleeson†

Teagasc, Animal & Grassland Research and Innovation Centre, Moorepark, Fermoy, Co. Cork, Ireland

In two experiments, the effect of applying hydrated lime as a cubicle bedding material

on the microbial count on teat skin and new intramammary infection were evaluated.

In experiment 1, dry dairy cows (n=60) were assigned to one of three cubicle bedding

treatments for a 5 week period. The treatments applied were: Hydrated lime (HL), HL

(50%) + Ground limestone (50%) (HL/GL) and GL. In experiment 2, two teat disin-

fectants products chlorhexidine (CH) and iodine (I) were applied to teats at milking in

conjunction with two cubicle bedding materials with lactating cows (n=60) for a six-

week period. The treatments applied were: HLCH; HLI; and GLI. The HL treatment

had significantly more teats (P160 IRISH JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD RESEARCH, VOL. 52, NO. 2, 2013

Introduction or shaving bedding to control bacte-

Mastitis represents a major economic cost rial populations (Fairchild et al. 1982).

to dairy farmers with losses of up €60 per Increasing the pH of cubicle bedding can

cow for the average milk supplier (O’Brien suppress bacterial growth (Kupprion et al.

2008). As bulk tank milk somatic cell 2002). Hydrated lime is an alkaline com-

count (BMSCC) increased, from ≤100,000 pound that can create pH levels as high

to >400,000 cells/mL, the net farm profit as 12.4. At levels greater than 12, the cell

generated decreased by €19,504 for the membranes of pathogens are considered

average Irish dairy farmer (Geary et al. destroyed (Chettri 2006). A one hundred-

2012). Milk loss due to subclinical mastitis fold decrease in bacterial numbers has

can also contribute to these overall farm been reported when HL was added to

losses (Hogeveen, Huijps and Lam 2011). recycled manure as a cubicle bedding

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the major (Hogan et al. 1999). However, anecdotal

and more virulent pathogens that can evidence suggests that the use of an iodine

cause mastitis infection and lactating cows based post-milking teat disinfectant in

are one of the main reservoirs of this spe- conjunction with the use of hydrated lime

cies. Moreover, S. aureus colonisation of can have a negative effect on teat condi-

teat skin increased the risk of intramam- tion. Long-term changes in teat condition

mary infection (IMI) (Myllys et al. 1993; generally occur over a period of 2 to 8

Roberson et al. 1994). It was suggested that weeks (Neijenhuis et al. 2000). The condi-

by minimising the exposure of teat ends to tion observed is generally referred to as

microorganisms, the rate of environmen- teat hyperkeratosis (Shearn and Hillerton

tal infection levels were reduced (Smith, 1996) and this condition can be exacerbat-

Todhunter and Schoenberger 1985). ed by disinfectants (Rasmussen 2004) or

During a cow housing period, bedding cold harsh weather (Timms, Ackermann

materials such as sawdust, lime and sand and Kerlhi 1997). Medium-term changes

are applied to cubicles to help to maintain to the teat barrel generally become vis-

a clean dry cubicle bed. By minimising ible within a few days or weeks of a man-

pathogen growth within the bedding mate- agement issue or environmental factors

rial, lower numbers of pathogens were occurring (Ohnstad et al. 2007). These teat

transmitted onto the cow’s teats, thereby changes include petechial haemorrhages

reducing the possibility of IMI (Kudi, Bray or larger hemorrhaging of the teat skin

and Niba 2009). However, materials of a (Hillerton, Middleton and Shearn 2001).

fine particle size such as sawdust may sup- Other changes include cracking or chap-

port rapid growth of bacteria and can lead ping of the teat skin (Hillerton et al. 2001).

to high populations of bacteria on teats. There is little knowledge on the effect

Zdanowicz et al. (2004) demonstrated a of using HL as the sole cubicle bedding

correlation between environmental bac- material on bacterial numbers on teats, on

terial counts on teat ends with bacterial teat condition and on IMI. The objectives

counts in sawdust bedding, which can cre- of this study were 1) to establish if dry

ate an environment for IMI (Hogan et al. dairy cows housed in cubicles which were

1999). However, some bedding materials bedded using HL would have a reduced

like sand can minimise pathogen growth teat microbial count, lower new intramam

(Kudi et al. 2009). Hydrated lime (HL; mary infections, have a better California

calcium hydroxide) has been added to Milk Test (CMT) result post-calving and

other bedding materials such as sawdust have lower somatic cell counts (SCC)Gleeson: Hydrated lime as a cubicle bedding material 161

for a three week period post-calving, period before calving and for a three week

compared to cows bedded with the com- period post-calving. Milk samples for both

monly used ground limestone (GL) and Experiments 1 and 2 were examined using

2) to establish if lactating dairy cows International Dairy Federation guidelines

housed in cubicles which were bedded for microbiological analysis (IDF 1981).

using HL combined with two contrasting

teat disinfectant products would have less Bacterial counts on teats

intramammary infections, lower SCC and On the start date and once weekly there

more teat skin irritation as measured by after, all teats from each cow in each group

teat-end hyperkeratosis and ‘medium term were swabbed using one sterile swab per

teat changes’, compared to cows bedded cow (Cultiplast, Milan, Italy), before teat

with the commonly used GL. preparation for milking. The sterile swab

was rubbed across the teat orifice and

down the side of each teat avoiding con-

Materials and Methods tact with the udder hair or cows flank.

Experiment 1 Swabs were then placed in individual ster-

Three cubicle bedding materials contain- ile bottles containing 5 mL of Tryptic Soy

ing (i) Hydrated lime (HL), (ii) HL (50%) Broth (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, USA).

+ Ground limestone (50%) (HL/GL) and The broth was prepared in 500 mL vol-

(iii) GL were applied to three separate umes and autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 min,

cubicle houses for a five week period. Sixty and then distributed into 5 mL aliquots

dry Holstein Friesian dairy cows were in a Laminar Flow Cabinet. The sterile

randomly assigned to one of three houses bottles containing the swabs were frozen

based on their expected calving date and (-20 °C) until analysed for the presence of

lactation number. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus bacteria.

Cubicle houses contained a central slat- The swabs were streaked across two sepa-

ted passage with a single cubicle space rate selective agars: Baird Parker (+ egg

allocation per cow and similar feed space yolk emulsion 50 mL/l) (Staphylococcus)

per group. Cubicles were bedded once and Edwards (+ 6% sterile bovine or

daily with sufficient material to leave a sheep blood) (Streptococcus). Following

dry surface with no cubicle matt visible. incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, microbi-

Cows remained on the cubicle bedding al counts for each pathogen type were

material until calving (mean of 5 weeks manually estimated and assigned to one

dry period per cow) and then were man- of four categories depending on bacte-

aged outdoors on grass. Individual quarter rial numbers present. (0=no pathogen

milk samples were taken post-calving and present, 1162 IRISH JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD RESEARCH, VOL. 52, NO. 2, 2013 of the three cubicle bedding treatments limestone rock which is used to soak up based on individual cow milk SCC (aver- moisture on cubicle mats or concrete. The age of three previous weeks), lactation pH of this product is approximately 8–8.5. number, days in milk (120) and teat hyper- keratosis score. Cows assigned to one HL Milk sample analysis cubicle house and the GL house were pre Individual quarter milk samples were and post sprayed at milking with an Iodine taken at the start date and at day 42 based (0.5%) teat disinfectant, HLI and and bacterial pathogens were iden- GLI, respectively. Cows assigned to the tified as 0=no pathogens present, 1= second HL cubicle house were pre and Staphylococcus aureus, 2=Non-haemolytic post sprayed at milking with a chlorhexi- Staphylococcus, 3=Streptococcus dysga- dine-based (Deosan Teatfoam, Diversey lactiae, 4=Streptococcus uberis. Quarters Hygiene Sales Limited, Jamestown Rd, with an SCC>500×106 cells/mL at the Finglas, Dublin 11) teat disinfectant start date were considered sub-clinically (HLCH). Pre-milking teat preparation infected and were excluded from this par- included washing teats with running water, ticular data set. followed by the application of the relevant Individual cow milk samples were col- teat disinfectant and then drying with an lected weekly using electronic milk meters individual paper towel for each cow. The (Dairymaster, Tralee, Co Kerry, Ireland) average daily milk yield per cow over the and analysed for SCC. Bulk milk samples test period was 23 kg per cow per day. with an SCC >500×106 cells/mL at the Treatment groups (n=20) were allocated start date were considered sub-clinically separate cubicle rows which contained a infected and were excluded from this slatted passageway with a single cubicle data set. The number of cows excluded space allocation per cow, similar feed for analysis was 2, 3 and 3 for HLI, space per group and remained indoors HLCH and GLI, respectively. Individual for the duration of the experiment. All quarter and bulk milk samples were ana- cubicles were fitted with rubber mats. lysed using a Somacount 300 (Bentley Cubicles were bedded with the manufac- Instrument Company Limited, Dublin 12, turer specification rate for HL (170 g per Ireland). cubicle) twice daily and this was applied to the back one-third of the cubicle. Higher Teat condition application rates than that specified are All four teats of each cow were visu- considered unnecessary due to the drying ally scored on three occasions (day 1, properties of HL and the possibility of day 21 and day 42) by the same operator deterioration in teat condition. This HL using a simplified classification system for product (White Rhino) is marketed as the evaluation of hyperkeratosis (HK) having a pH of 12.4 that can inhibit bacte- in bovines (Neijenhuis et al. 2001). The rial growth. classification scores were: Score1=normal Cubicles bedded with GL received a teat-end orifice; Score2=slight smooth or more liberal application (approx 300 g broken ring of keratin; Score3=moderate per cubicle) twice daily, which is typical raised smooth or broken ring of keratin; of rates normally applied for this prod- Score4=large raised smooth or broken uct on farm. Ground limestone (Agrical, ring of keratin. Teats were scored directly Nutribio Ltd, Tivoli Industrial Estate, after milking, with the help of artificial and Cork, Ireland) is milled and crushed light to illuminate teat ends and the score

Gleeson: Hydrated lime as a cubicle bedding material 163

totaled and averaged for each cow for the treatments for SCC and teat hyperkera-

purposes of analysis. tosis score at each measurement day and

Teat barrels were also inspected by the when data were pooled over the total mea-

same operator at the start date and on five surement period. Interactions for time and

occasions thereafter for medium-term teat treatment x time were also tested. A t-test

changes. Teats were scored for these con- was used to measure changes in quarter

ditions by visual assessment using a simple somatic cell count from day 1 to day 42 for

classification system as recommended by each individual treatment. Differences in

Mein et al. (2001) for assessing these bacterial numbers observed on cow’s teats

conditions; Score1=Normal teat (smooth, were measured using Fisher’s exact test.

soft, healthy skin), Score2=Dry skin (red- Where there was an effect of treatment a

dened or blue skin, flaky or rough skin pair-wise comparison was conducted.

with minimum cracking) and Score3=

Open lesions (chapped, cracked).

On the start date and once weekly

thereafter, all teats from cows in groups Results

GLI and HLI were swabbed to measure Experiment 1

bacterial numbers using the same tech- There were no differences observed in the

nique and method of analysis as applied in number of quarters classified for a CMT

experiment 1. score of 1 or >1 or for pathogens pres-

ent in milk samples at calving between

bedding treatments (Table 1). There were

Statistical Analysis no significant differences observed for

Statistical analysis of data was performed BMSCC between treatments at weeks 2, 3

using SAS software (SAS 2011). Cows and 4 post calving. The average BMSCCs

were blocked in pairs according to lacta- over the trial period were 92,000, 60,000

tion number and expected calving date and 74,000 cells/mL for HL, HL/GL and

for experiment 1 and on the average GL, respectively. There was one clinical

BM SCC (previous three weeks), days in case for each of HL and GL treatments

milk and teat-end hyperkeratosis score for over the four week lactating period.

experiment 2. The statistical model was a There were no significant differences

mixed model with cows/blocks as the ran- in teat bacterial numbers between treat-

dom effect and bedding treatment as the ments for experiment 1 and 2 on day

fixed effect and with repeated measures 1. Numbers of both Staphylococci and

over time. Comparison was made between Streptococci observed on teats reduced

Table 1. Number (%) of quarters with low (1) and high (≥2) California Mastitis Test scores at calving -

Experiment 1

California California No. quarters

Mastitis Test1 (%) Mastitis Test (%) with pathogens

Bedding material No. of quarters 1 ≥2

Hydrated lime 55 48 (87) 7 (13) 1

Hydrated/Ground limestone 76 69 (91) 7 (9) 1

Ground limestone 67 66 (98) 1 (2) 3

1California Mastitis Test Score: 1=200,000 cells/mL and ≥2=150,000 to 5,000,000 cells/mL.164 IRISH JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD RESEARCH, VOL. 52, NO. 2, 2013 during the measurement period regardless differences between bedding treatments or of the cubicle bedding material applied. within treatments at day 1 (start day) or at When swab counts for each measure- day 42 (finish day) (P>0.05). The average ment day were pooled, the HL treat- quarter SCC on day 1 was 29,000, 34,000 ment had more teats with no Staphlococci and 21,000 and on day 42 was 35,000, 41,000 present compared to GL and had less and 39,000 cells/mL for HLI, HLCH and teats with ‘numerous’ bacteria (11

Gleeson: Hydrated lime as a cubicle bedding material 165 respectively. The percentage of quarters tissue observed in all cases were considered with an SCC greater than 200,000 cells/mL mild (score 2) and in the majority of cases increased (5%) with the GL bedding treat- were transient in nature. Changes observed ment compared to day 1. However, the per- included partial redness of the teat barrel centage of quarters with an SCC>200,000 and minor cracking of the teat skin. In two

166 IRISH JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD RESEARCH, VOL. 52, NO. 2, 2013

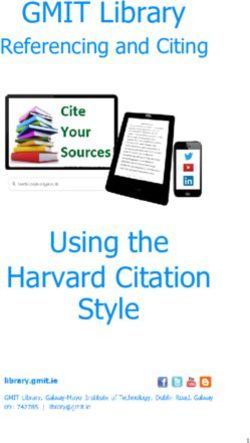

2.4

HLI HLCH GLI

2.3

2.3 2.25 2.25

2.2 2.2

2.2

Teat score (1–4)

2.1

2.1

2

2.0

1.93 1.93

1.9

1.8

1.7

1 2 3

Observation times

Figure 1. Average teat hyperkeratosis score on day 1, 21 and 42 – Experiment 2.

HLI=Hydrated lime + Iodine, HLCH=Hydrated lime + Chlorhexidine, GLI=Ground

limestone + Iodine.

first observation day compared to the sub- The percentage of teats within four

sequent two observation days (PGleeson: Hydrated lime as a cubicle bedding material 167 teats prior to teat preparation for milking periods probably indicates an effect of at each observation day (Figure 2). The improved management for all cubicles percentage of teats with no Staphylococci during the test period. As cubicle bedding present was higher (P

168 IRISH JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD RESEARCH, VOL. 52, NO. 2, 2013 further of new intramammary infection. While all treatments had low SCC lev- Satisfactory teat preparation (Gleeson et els, the HLCH treatment had the lowest al. 2009) prior to milking in experiment level at most tests days during the study. 2 also nullified differences in teat bacte- The HLCH treatment was also observed rial numbers between treatments, as teat to have the lowest percentage of cows swabbing was conducted prior to teat (9%) with a SCC>100k compared to the preparation and this may also account HLI (14%) and GLI (19%) during the for no differences in new intramammary study. This may indicate a positive benefit infection between treatments. Very low of disinfectant type rather than bedding bacterial levels on teats could be expected material. Furthermore, the average quar- after teat disinfection as compared to ter SCC was low at the trial start date and levels taken before disinfection (Kristula good management practices such as regu- et al. 2008). In Experiment one, the SCC lar maintenance of the cubicle beds and levels recorded and the number of clini- teat preparation prior to milking, were cal cases observed during the period post important factors in maintaining low SCC calving were low for all bedding treat- levels and new infection rates for all treat- ments. In this experiment, cows were ments throughout the study. The milking grazed outdoors from calving and this process through improper milking time, management strategy may account for the hygiene and machine function can contrib- low SCC and new infection levels record- ute to new infection rates when bacteria ed. Environmental factors can influence are present (National Mastitis Council the microbial populations on teats ends 1996; Galton, Petersson and Merrill 1988). (Rendos, Eberhart and Kesler 1975). While the HL treatment had lower bacte- Higher SCC levels have been reported rial numbers on teats when presented for during the months where cows are nor- milking, all teats were prepared (washed, mally housed indoors (Nov to March) disinfected and dried with individual paper with SCC reducing during the summer towels) prior to cluster application and period corresponding to when cows are this may have partially nullified the benefit grazed outdoors (Berry et al. 2006). The of the bedding material as teat prepara- benefits of any carry over effect of the tion has been shown to reduce teat bac- bedding material from the housed period terial numbers (Gleeson et al. 2009) and pre-calving were not evident. in particular environmental Streptococcal In Experiment two, an increase in the infections (Pankey et al. 1989). Should teat number of quarters with sub-clinical infec- preparation be omitted/less rigorous, as in tions was observed for the non-hydrated the case on many dairy farms in Ireland, lime bedding treatment compared to the differences in new infection rates may start date and this may be partially due to have been observed. the cows remaining indoors for the dura- There were no differences in ‘medium tion of this study. The percentage of GLI term’ teat changes between the two hydrat- quarters with a sub-clinical infection was ed lime treatments; however the GLI bed- 1.9% higher than HLCH and 3.4% higher ding treatment had a lower number of teat than HLI. However, this increase in sub- tissue changes during the study. Previous clinical infections during the trial period studies by Kristula et al. (2008) indicated could be related to the high percentage that the application of HL at a rate of of cows with bacteria present in quarters 0.5 kg per cubicle every 48 h caused an on day 1. irritation to skin, udder and legs of cows,

Gleeson: Hydrated lime as a cubicle bedding material 169

with some lesions evident approximately the hydrated lime treatments. A larger

3 days after exposure to HL. There were no number of study animals and a longer test

lesions to udder and legs in this study and period may be necessary to show a signifi-

only minor ‘medium term teat changes’, cant effect of HL in terms of reduced new

even though the application rate for HL infection rates. Hydrated lime could be

was higher (340 g/day) compared to that successfully used as cubicle bedding mate-

applied by Kristula et al. (2008). The appli- rial for dairy cows if used at the recom-

cation of HL on four occasions instead of mended rates with either CH or I based

one in 48 h may also have influenced this teat disinfectants.

outcome. Furthermore, it was suggested

by Kristula et al. (2008) that stall designs

that allow more manure to be deposited Acknowledgements

on the back end of the cubicle mattress The author wishes to thank John Paul Murphy

and Jimmy Flynn for their technical assistance

may also exacerbate the irritation prob-

and the staff of the dairy unit at Teagasc, Animal

lem. Cubicles in this present study were & Grassland Research and Innovation Centre,

cleaned down twice daily when the lime Moorepark, Fermoy, Co. Cork for their help in car-

was applied. ing for the cows.

The percentage of teat changes for all

treatments were much lower than +5% References

which is an accepted level as an indicator Berry, D.P., O’Brien B., O’Callaghan, E.J., O’Sullivan,

of good milking machine function and K., and Meaney, W.J. 2006. Temporal trends in

operation (Hamann 1997). The average bulk tank somatic cell count and total bacterial

teat end hyperkeratosis score did not dif- count in Irish dairy herds during the past decade.

Journal of Dairy Science 89: 4083–4093.

fer between treatments. The percentage Chettri, R.S. 2006. Evaluation of hydrated lime treat-

of teats within score category 4 was simi- ment of free-stall bedding and efficacy of teat

lar (9%) for both the HLI and the GLI sealant on incidence of dairy cow mastitis. Thesis,

treatments and less than that suggested submitted to Auburn University, Alabama, USA,

by Reinemann (2007) (20%), as an indica- May 11th, 2006, Pages 135. Available online: http://

etd.auburn.edu/etd/bitstream/handle/10415/525/

tor of poor teat condition in a herd. The CHETTRI_REKHA_39.pdf. [accessed 7

higher teat score observed over time in November 2013].

this study could be expected as hyperkera- Galton, D.M., Petersson, L.G. and Merrill, W.G.

tosis score increases with stage of lactation 1988. Evaluation of udder preparations on

intramammary infections. Journal of Dairy Science

(Neijenhuis et al. 2000). From a health and

71: 1417–1421.

safety perspective when applying HL to Geary, U., Lopez-Villalobos, N., Begley, N., McCoy,

cubicle beds it would be considered good F., O’Brien, B., O’Grady, L. and Shalloo, L. 2012.

practice to use a face mask as it tends to be Estimating the effect of mastitis on the profitabil-

dustier than GL. ity of Irish dairy farms. Journal of Dairy Science

95: 3662–3673.

Gleeson, D., O’Brien, B., Flynn, J., O’Callaghan,

E. and Galli, F. 2009. Effect of pre-milking teat

Conclusions preparation procedures on the microbial count on

The hydrated lime bedding treatment teats prior to cluster application. Irish Veterinary

resulted in significantly less Staphylococci Journal 62: 461–467.

and Streptococci on teat skin compared to Godkin, A. 1999. Does lime stop mastitis. Ontario

Ministry of Agriculture and Food, Information

the ground limestone bedding treatment. sheet. Available online: http://www.omafra.gov.

Numerically lower levels of BMSCC and on.ca/english/livestock/dairy/facts/info_limeag.

subclinical infections were observed with htm [accessed 1 November 2013].170 IRISH JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD RESEARCH, VOL. 52, NO. 2, 2013 Hamann, J. 1997. Machine induced teat tissue chang- J.S., Farnsworth, R., Cook, N. and Hemling, T.C. es and new infection risk. Proceedings of the 2001. Evaluation of bovine teat condition in com- International Conference on Machine Milking mercial dairy herds: 1. Non-infectious factors. and Mastitis, Silver Springs Hotel, Cork, Ireland, Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium pages 75–84. on Mastitis and Milk Quality, Vancouver, Canada, Hogeveen, H., Huijps, K. and Lam, T.J.G.M. 2011. pages 347–351. Economic aspects of mastitis: new developments. Kupprion, E.K., Toth, J.D., Dou, Z., Aceto, H.W. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 59: 16–23. and Ferguson, J.D. 2002. Bedding amendments Hillerton, J.E., Middleton, N. and Shearn, M.F.H. for environmental mastitis in dairy cattle. Joint 2001. Evaluation of bovine teat condition in com- meeting abstracts. Available online: http://www. mercial dairy herds: A portfolio of teat conditions. jtmtg.org/2002/abstracts/jnabs36.pdf [accessed 14 Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on November 2013]. Mastitis and Milk Quality, Vancouver, Canada, Myllys, V., Honkanen-Buzalski, T., Virtanen, H., pages 472–473. Pyorala, S. and Muller, H.P. 1993. Effect of abra- Hillerton, J.E., Morgan, W.F., Farnsworth, F., sion of teat orifice epithelium on development of Neijenhuis, F., Baines, J.R., Mein, G.A., Ohnstad, bovine staphylococcal mastitis. Journal of Dairy I., Reinemann, D.J. and Timms, L. 2001. Science 77: 446–452. Evaluation of bovine teat condition in commer- National Mastitis Council. 1996. “Current Concepts cial dairy herds: Infectious factors. Proceedings of of Bovine Mastitis”, 4th edition, Madison, the 2nd International Symposium on Mastitis and Wisconsin, USA, pages 40–41. Milk Quality, Vancouver, Canada, pages 352–356. Neijenhuis, F., Barkema, H.W., Hogeveen, H. and Hogan, J.S. and Smith, K.L. 2003. Coliform Mastitis. Noordhuizen, J.P. 2000. Classification and longi- Veterinary Research 34: 507–519. tudinal examination of callused teat ends in dairy Hogan, J.S., Smith, K.L., Hoblet, K.H., Schoenberger, cows. Journal of Dairy Science 83: 2795–2804. P.S., Todhunter, D.A., Hueston, W.D., Pritchard, Neijenhuis, F., Mein, G.A., Morgan, W.F., D.E., Bowman, G.L., Heider, L.E., Brockett, B.L. Reinemann, D.J., Hillerton, J.E., Baines, J.R., and Conrad, H.R. 1989a. Field survey of clinical Ohnstad, I., Rasmussen, M.D., Timms, L., Britt, mastitis in low somatic cell count herds. Journal of J.S., Farnsworth, R., Cook, N. and Hemling, Dairy Science 72: 1547–1556. T.C. 2001. Evaluation of bovine teat condition Hogan, J.S., Smith, K.L., Todhunter, D.A., in commercial dairy herds: relationship between Schoenberger, P.S., Hueston, W.D., Pritchard, teat-end callosity or hyperkeratosis and mastitis. D.E., Bowman, G.L., Heider, L.E and Brokett, Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium B.L. 1989b. Bacterial counts in bedding materials on Mastitis and Milk Quality. Vancouver, Canada, used on nine commercial dairies. Journal of Dairy pages 362–366. Science 72: 250–258. Ohnstad, I., Mein, G.A., Baines, J.R., Rasmussen, Hogan, J.S., Bogacz, V.L., Thompson, L.M. Romig, M.D., Farnsworth, R., Pocknee, B., Hemling, T.C. S., Schenberger, P.S., Weiss, W.P. and Smith, K.L. and Hillerton, J.E. 2007. Addressing teat condi- 1999. Bacterial counts associated with sawdust tion problems. Proceedings of the National Mastitis and recycled manure bedding treated with com- Council 46th Annual Meeting, San Antonio, Texas, mercial conditioners. Journal of Dairy Science 82: USA, pages 188–189. 1690–1695. Pankey, J.W. 1989. Hygiene at milking time in the International Dairy Federation (IDF). 1981. prevention of bovine mastitis. British Veterinary Laboratory Methods for use in Mastitis Work, IDF Journal 145: 401–409. Brussels, Belgium, Bulletin No. 132, pages 17–18. Rasmussen, M.D. 2004. Overmilking and teat con- Kristula, M.A., Dou, Z., Toth, J.D., Smith, B.I., dition. Proceedings of the 43rd National Mastitis Harvey, N. and Sabo, M. 2008. Evaluation of Council Meeting, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA, free-stall mattress bedding treatments to reduce pages 169–175. mastitis bacterial growth. Journal of Dairy Science Reinemann, D.J. 2007. Latest thoughts on methods 91: 1885–1892. for assessing teat condition. 46th Annual meeting Kudi, A.C, Bray, M.P. and Niba, A.T. 2009. Mastitis of the National Mastitis Council, San Antonio, causing pathogens within the dairy environment. Texas, USA, 21–24th January, 2007, pages 8. International Journal of Biology 1: 3–7. Rendos, J.J, Eberhart, R.J. and Kesler, E.M. 1975. Mein, G.A., Neijenhuis, F., Morgan, W.F., Microbial populations on teat ends of dairy cows Reinemann, D.J., Hillerton, J.E., Baines, J.R., and bedding materials. Journal of Dairy Science Ohnstad, I., Rasmussen, M.D., Timms, L., Britt, 58: 1492:1500.

Gleeson: Hydrated lime as a cubicle bedding material 171 Roberson, J.R., Fox, L.K., Hancock, D.D. and Gay, Timms, L.L., Ackermann, M. and Kehrli, M. 1997. J.M. 1994. Ecology of Staphylococcus aureus iso- Characterization of teat end lesions observed lated from various sites on dairy farms. Journal of on dairy cows during winter. Proceedings of the Dairy Science 77: 3354–3364. Annual Meeting of the National Mastitis Council, SAS. 2011. Version 9.3. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 36: 204–209. USA. Zdanowicz, M., Shelford, C.B., Tucker, D.M., Shearn, M.F.H. and Hillerton, J.E. 1996. Weary, D.M. and Von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. 2004. Hyperkeratosis of the teat duct orifice in dairy Bacterial populations on teat ends of dairy cows cows. Journal of Dairy Research 63: 525–532. housed in free stalls and bedded with either Smith, K.L., Todhunter, D.A. and Schoenberger, sand or sawdust. Journal of Dairy Science 87: P.S. 1985. Environmental mastitis: causes, pre- 1694–1701. valence, prevention. Journal of Dairy Science 68: 1531–1553. Received 9 September 2013

You can also read