Endoscopic Treatment of Zenker's Diverticulum: Comparable Treatment Outcomes in Treatment-Naïve and Pretreated Patients

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Hindawi

Gastroenterology Research and Practice

Volume 2021, Article ID 9237617, 6 pages

https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9237617

Research Article

Endoscopic Treatment of Zenker’s Diverticulum: Comparable

Treatment Outcomes in Treatment-Naïve and Pretreated Patients

Johannes Manzeneder , Christoph Römmele, Carolin Manzeneder, Alanna Ebigbo,

Helmut Messmann, and Stefan Karl Goelder

Department of Internal Medicine III at the University Hospital Augsburg, Germany

Correspondence should be addressed to Johannes Manzeneder; sjmanze@gmail.com

Received 28 June 2020; Revised 14 February 2021; Accepted 22 February 2021; Published 16 March 2021

Academic Editor: Agata Mulak

Copyright © 2021 Johannes Manzeneder et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution

License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly cited.

Background and Aims. Flexible endoscopic treatment plays an important role in the treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum (ZD). This

study analyzes long-term symptom control and the rate of adverse events in treatment-naïve patients and patients with recurrence,

using the stag beetle knife junior (sb knife jr). Methods. From August 2013 to May 2019, 100 patients with symptomatic ZD were

treated with flexible endoscopy using the sb knife jr. Before treatment, as well as 1 and 6 months afterwards, symptoms were

obtained by a nine-point questionnaire, with symptoms weighted from 0 to 4. Results. Overall, 126 interventions were

performed. The median follow-up period was 41 months (range 7-74). For the three most frequent symptoms, regurgitation,

dysphagia, and dry cough, a significant reduction of the mean score could be achieved, from 2.85/3.45/2.85 before the initial

treatment to 0.56/1.09/0.98 6 months later. 17 patients were retreated because of recurrence. Out of these, 12 patients underwent

a 2nd, 4 patients a 3rd, and 1 patient a 4th session, respectively. The mean dysphagia score for successfully treated patients could

be reduced from initially 2.34 to 0.49/0.33/0.67 after the 1st/2nd/3rd session, the frequency of dysphagia from 3.45 to

0.92/1.00/1.33, and the score for regurgitations from 2.85 to 0.35/1.00/0.67. In first-line treatment, as well as in retreatment, no

severe adverse event occurred. Conclusion. Patients with ZD can be treated safely and effectively with the sb knife jr.

Retreatment leads to equal symptom relief as compared to a successful first-line treatment and is not associated with a higher

rate of adverse events.

1. Introduction been introduced [6]. Currently, flexible endoscopy plays an

important role in the treatment of ZD. Basically, endoscopic

Zenker’s diverticulum (ZD) is a rare disease of the laryngo- approaches have in common the incision of the diverticular

pharynx that appears mainly in elderly people. It emerges bridge with varying success and recurrence rates. However,

in a weak part of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle the recurrence rate remains an issue of controversy, especially

called the triangle of Killian which is located superior to the when comparing endoscopic and surgical techniques [1, 6, 7].

upper esophageal sphincter [1, 2]. Patients with ZD primarily The aim of this study is to investigate symptom control

suffer from dysphagia and regurgitations. But there are a and the rate of adverse events in flexible endoscopic treat-

number of other symptoms such as halitosis, aspiration, dry ment of ZD with the stag beetle knife junior (sb knife jr) in

cough, and vomiting in varying frequency and intensity asso- first-line therapy as well as in the therapy of symptomatic

ciated with ZD [1, 3]. recurrence.

For a long time, the treatment had been either surgical or

peroral with a rigid endoscope mostly done by Ear-Nose- 2. Methods

Throat (ENT) physicians. In the midnineties, an approach

with flexible endoscopy was presented for the first time [4, 2.1. Patients. Data from patients with symptomatic ZD who

5]. Since then, a huge variety of techniques and devices have were treated at the Department of Internal Medicine III at2 Gastroenterology Research and Practice

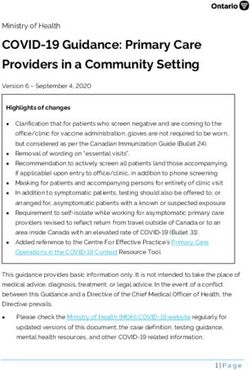

(a) (b) (c) (d) (e)

(f) (g) (h) (i) (j)

Figure 1: (a) Symptomatic ZD of a 73-year-old male patient. (b) Fixation of the diverticulum with an overtube. (c) Incision of the mucosa and

the upper muscular fibers of the diverticular bridge. (d) Cutting down the diverticular bridge with the sb knife jr. (e) Final result after the first

session. (f–j) Second session because of recurrence 16 months later.

the University Hospital Augsburg, Germany, from August Each patient received a single dose of antibiotics (2 g ceftri-

2013 to May 2019 were evaluated. All patients were treated axone) during the intervention. Clipping of the bottom of the

with flexible endoscopy and the sb knife jr as the cutting incision line was not done routinely. Prophylactic clipping to

device. Patients who had had a previous treatment, either prevent delayed bleeding or perforation was performed in

surgical or endoscopic, were excluded. some cases, based on the judgment of the endoscopist.

Recurrence was defined as a relapse of symptoms with

2.2. Endoscopic Procedure and Devices. All interventions were substantial limitations in a patient’s quality of life. Adverse

done by two experienced endoscopists (H.M., S.K.G.). A sin- events were classified according to the American Society for

gle treatment protocol was implemented. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) [9].

On the day prior to the intervention, a gastroscopy was

performed to clean the diverticulum of food remnants, to 2.3. Postprocedural Management and Follow-Up. On the day

measure the size, and to inspect the diverticulum in order after the intervention, a contrast swallow was performed. If

to exclude patients with a candida infection. Diverticulotomy there was no evidence of perforation, the transition to a soft

was performed in deep sedation with midazolam, pethidine, diet for five days was commenced.

and propofol. First, a soft diverticuloscope (ZD overtube, The symptoms of the patients were recorded before treat-

ZDO-22/33 Cook Medical, Limerick, Ireland) was placed to ment as well as one and six months after the intervention by a

stretch the diverticular bridge between the esophagus and questionnaire developed in our clinic [3, 10]. The question-

the diverticular lumen. The endoscope (GIF-HQ190, Olym- naire contains nine points: Dakkak and Bennett’s dysphagia

pus Europa, Hamburg, Germany) was inserted, and the score [11]; the frequency of dysphagia, odynophagia, regurgi-

mucomyotomy was done with the sb knife jr (Sumitomo tation, vomiting, dry cough, halitosis, and nocturnal awaken-

Bakelite, Tokyo, Japan). This is a scissors-shaped device with ing due to Zenker-related symptoms; and the general

an opening width of 3.5 mm that can be rotated by 360 condition of the patient including body weight, duration of

degrees. Additional to electrical cutting, the device is able to symptoms, and weight loss. The symptoms were registered

simultaneously compress the tissue. Due to the mechanical on an ordinal scale with values from zero to four (Table 1).

effect, the directly adjacent tissue is more strongly bonded All patients were informed about the possibility of readmis-

together (Figure 1). The electrosurgical current was gener- sion in case of recurring symptoms. Additionally, patients

ated by the VIO 300 unit (Endocut Q Effect 1, soft coagula- who stated a high point value (>12) in the questionnaire six

tion 40 W, Erbe, Tübingen, Germany). months after the initial intervention were called to evaluate

The technique was modified in the course of the study; whether further treatment was necessary.

initially, only one incision was done in the middle of the 2.4. Statistics. The evaluation was performed using Microsoft

diverticular bridge. Later, two incisions were made and the Excel. Data were stated as mean, median, and standard devi-

part in-between was resected with a snare (double incision ation. For statistical analysis, different t-tests and chi-squared

and snare resection (DISR)) in order to get a broader incision tests were used. Statistical significance was assumed at a p

of the diverticular bridge. The incision was then continued in value ofGastroenterology Research and Practice 3

Table 1: Content of the questionnaire.

0 1 2 3 4

Recorded symptoms

Frequency of dysphagia Never4 Gastroenterology Research and Practice

Initial treatment Successful treatment eight (8%) later than six months. Five patients needed a third

⁎

n = 100 n = 83 session and one a fourth.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

who developed a recurrence did not differ from patients

Recurrence Successful treatment without recurrence (Table 4). Furthermore, the size of the

n = 17 n = 12 diverticulum did not correlate with the risk of recurrence

(p = 0:26). The median diverticular size in patients with

recurrence was 15 mm (range 5-35 mm). Considering the

2nd recurrence Successful treatment

n=5 n=4

recurrence rate, there was no significant difference between

DISR and single incision technique (DISR 17.1%, single inci-

sion 16.9%, and p = 0:99). Also, the use of clips during the

3rd recurrence Successful treatment first intervention had no influence on the recurrence rate

n=1 n=1 (clips used 10.5%, no clips 18.5%, and p = 0:40).

After retreatment, symptom scores of patients with

Figure 2: Flow chart of patients with recurrence. Recurrence: recurrence could be reduced to a level comparable to patients

recurring symptoms after a temporary improvement. ∗ 103 who were recurrence-free after one intervention. Dakkak and

sessions in 100 patients due to three two-stage treatments. Bennett’s dysphagia score was reduced from 2.34 to 0.49

(p < 0:001) in patients without recurrence. Those patients

(median score for regurgitations 0.56, p < 0:001; for dyspha- who developed a recurrence after the initial treatment had

gia 1.09, p < 0:001; and for dry cough 0.98, p < 0:001). an average score of 1.31 six months after the first interven-

tion. Six months after the second treatment, the score was

0.33 (p = 0:01) for patients with no further recurrence and

3.2. Adverse Events. Intraprocedural bleeding occurred in 16

1.50 for patients with a second recurrence. Besides one

interventions (12.7%). Most cases (15) were stopped by coag-

patient, all remaining patients could be treated successfully

ulation with the sb knife jr or by a hemostatic grasper (Coa-

in the third session. Their dysphagia score was 0.67 six

grasper Hemostatic Forceps FD-411 QR, Olympus Europa,

months after the third intervention which is comparable to

Hamburg, Germany). In four cases, clips (range 1-2, Olym-

the values of those patients who did not develop a further

pus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan) were used. In

recurrence after the first or second treatment. Due to the

three cases, a combination of a hemostatic grasper and

small number of patients in this group (available data from

hemoclips was applied. Termination of the procedure due

three out of four patients), a reasonable statistical calculation

to intraprocedural bleeding was not necessary since all bleed-

is not possible in that case (Figure 3).

ing cases could be treated successfully. There was no case of

The same effect was seen for the frequency of dysphagia

delayed bleeding. Procedures performed using the DISR

and regurgitation. Regarding the frequency of dysphagia,

technique showed a slightly lower bleeding rate, but this

the value declined from 3.45 to 0.92 (p < 0:001)/1.00 (p =

was not significant (DISR 12.2%, single incision 18.6%, and

0:02)/1.33 in successfully treated patients (six months after

p = 0:39).

the 1st/2nd/3rd session) and for regurgitation from 2.85 to

In four cases, a perforation was suspected during the

0.35 (p < 0:001)/1.00 (p < 0:01)/0.67. Patients with recur-

intervention. Of these, one intervention had to be stopped

rence needed in total a mean of 2.35 sessions (range 2-4) to

prematurely. In five other cases, contrast swallow after the

achieve symptom control.

treatment showed a small perforation. In case a perforation

No bleeding occurred in the treatment of recurrences

was suspected, nil diet and clinical observation were extended

which means that the rate of bleeding was significantly lower

and antibiotics were given for several days. But in all these

in the retreatment group compared to the initial intervention

cases, the further clinical course was uneventful. Emphysema

group (p = 0:04). Also, there was no other severe adverse

was not observed in any of the patients.

event in the treatment of recurrences.

Three patients suffered severe or prolonged postproce-

dural pain. One patient was monitored overnight in the inten-

sive care unit to rule out serious adverse events as a reason for

his pain. All these patients were managed conservatively.

4. Discussion

Another patient developed a hemodynamically relevant

The strength of this study is the large cohort of patients and

tachycardia (focal atrial tachycardia) after the intervention,

the follow-up over a median of 41 months (range 7-74).

most probably because she had not taken her antiarrhythmic

Besides the study of Huberty et al. [13], this is one of the larg-

medication prior to the intervention. She spent one night in

est prospectively documented cohort of patients with symp-

the intensive care unit and was treated with amiodarone.

tomatic ZD treated by a flexible endoscopic approach. Due

In all 126 interventions, no severe adverse event was

to the long-term follow-up period, late recurrences were also

observed. There was no case of mediastinitis or abscess.

included. Of course, there might be patients that are lost to

follow-up so that recurrences are not detected. But this prob-

3.3. Recurrence. After initial treatment, 17 patients (17%) lem is similar to other interventional studies concerning ZD.

developed a recurrence (Figure 2). Nine (9%) recurrences The recurrence rate of 17% is comparable to the results of

occurred within the first six months after treatment, and other studies with flexible endoscopy [6].Gastroenterology Research and Practice 5

Table 4: Descriptive characteristics before treatment stratified by no recurrence/recurrence.

Nonrecurrence Recurrence p value

Total number of patients 83 17

Median follow-up (months) 44 (7-74) 39 (7-69)

Median age 71 (42-92) 73 (49-85) 0.90

Sex (female/male) 32/51 4/13 0.24

Median diverticular size (mm) 20 (10-45) 27.5 (20-40) 0.26

Median body mass index (kg/m2) 25.8 (17.3-38.0) 27.1 (17.5-34.5) 0.70

Mean weight loss (kg) 2.1 (0-20) 2.3 (0-20) 0.83

Values express absolute numbers with (range).

⁎ events such as mediastinitis or permanent palsy of the re-

current laryngeal nerve. Moreover, surgical meta-analysis

⁎⁎⁎

shows a small number of therapy-related deaths [1, 14].

4

n=5

Also, in approaches with rigid endoscopes, some major

adverse events, such as abscesses requiring external drain-

n = 17

3 age, occurred [16].

Although the rate of recurrence in our cohort is slightly

higher, this study has shown that treatment can be easily

n = 83

n=4

2

n = 100

repeated with a high success rate. Repetition of a surgical

n = 11

n=1

treatment might be more difficult and challenging due to

1 scarring tissue. In our cohort, retreatment was technically

feasible, and in one patient, retreatment was performed four

0 times. Retreatment of those patients was not associated with

Prior to After After After

treatment 1st session 2nd session 3rd session a higher rate of adverse events, and the rate of bleeding was

even significantly lower. Dissection of the scar and remaining

No recurrence muscle tissue with flexible endoscopy is technically not more

Recurrence challenging than the initial treatment. Patients with recur-

rence could achieve the same control of their symptoms as

Figure 3: Dysphagia score of patients with and without recurrence patients without recurrence. Eventually, even patients who

after each session. Mean dysphagia score prior to initial treatment

needed several sessions (mean 2.35 sessions) could be treated

and six months after each session. Dysphagia score: 0: no

dysphagia, 1: solid food, 2: soft food, 3: fluids, and 4: aphagia. ∗∗∗ t

successfully.

-test significance p < 0:001, ∗ t-test significance p < 0:05. Tunneling myotomy has been reported recently; how-

ever, further studies are needed to clarify its long-term effec-

tiveness [17, 18]. It is also unclear if a tunneled myotomy

In surgical transcervical series, the reported recurrence could be repeated in case of recurrence.

rate varies widely, depending on the surgical technique, from A limitation of this study is that there is no direct com-

1.9% for open suspension [14] to 21% for invagination of the parison to other therapeutic methods, especially a transcervi-

diverticulum [1]. cal surgical approach. A randomized study with different

In our study, patients who developed recurrence could treatment paths would be able to compare the rate of recur-

be divided into two major groups. In group one (9%), after rence and adverse events.

an initial distinct improvement of symptoms, recurrence

occurred early within a few months after treatment. In

the second group (8%), the patients were already in remis- 5. Conclusion

sion before they developed recurrent symptoms (median 16

Symptomatic ZD can be controlled with endoscopic treat-

months, range 8-26). A reason for the early recurrences

ment using the sb knife jr in a safe and effective way. Patients

might be an incomplete initial dissection of the cricophar-

with recurrence can be retreated without an increased risk of

yngeal muscle in the first session. Probably, the myotomy

adverse events and with a high success rate. Patients with

for those patients was not wide or long enough. An incom-

recurrence can ultimately achieve the same long-term symp-

plete myotomy of the upper esophageal sphincter has

tom control as treatment-naïve patients.

already been discussed in the literature as a possible cause

of recurrence [7, 15]. Why other patients, after an initially

successful treatment with good symptom control, suffer a Data Availability

recurrence after a longer period of time cannot be conclu-

sively explained at present. The data on which this study is based have been deposited in

There were no severe adverse events. In contrast, surgical the study secretariat of the Department of Internal Medicine

approaches have a low but relevant number of severe adverse III at the University Hospital Augsburg.6 Gastroenterology Research and Practice

Conflicts of Interest of Zenker’s diverticulum,” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, vol. 83,

no. 4, pp. 765–773, 2016.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. [16] R. Wilken, C. Whited, and R. L. Scher, “Endoscopic staple

diverticulostomy for Zenker’s diverticulum: review of experi-

Authors’ Contributions ence in 337 cases,” The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Lar-

yngology, vol. 124, no. 1, pp. 21–29, 2015.

Johannes Manzeneder and Christoph Römmele contributed [17] J. Yang, X. Zeng, X. Yuan et al., “An international study on the

equally to this work. use of peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) in the manage-

ment of esophageal diverticula: the first multicenter D-

POEM experience,” Endoscopy, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 346–349,

References 2019.

[1] M. Colombo-Benkmann, V. Unruh, T. Kocher, C. Krieglstein, [18] Q. L. Li, W. F. Chen, X. C. Zhang et al., “Submucosal tunneling

and N. Senninger, “Modern treatment options for Zenker’s endoscopic septum division: a novel technique for treating

diverticulum: indications and results,” Zentralblatt für Chirur- Zenker’s diverticulum,” Gastroenterology, vol. 151, no. 6,

gie, vol. 128, no. 3, pp. 171–186, 2003. pp. 1071–1074, 2016.

[2] J. J. van Overbeek, “Pathogenesis and methods of treatment of

Zenker’s diverticulum,” The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and

Laryngology, vol. 112, no. 7, pp. 583–593, 2003.

[3] J. Brueckner, A. Schneider, H. Messmann, and S. K. Gölder,

“Long-term symptomatic control of Zenker diverticulum by

flexible endoscopic mucomyotomy with the hook knife and

predisposing factors for clinical recurrence,” Scandinavian

Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 51, no. 6, pp. 666–671, 2016.

[4] S. Ishioka, P. Sakai, F. Maluf Filho, and J. M. Melo, “Endo-

scopic incision of Zenker’s diverticula,” Endoscopy, vol. 27,

no. 6, pp. 433–437, 1995.

[5] C. J. Mulder, G. den Hartog, R. J. Robijn, and J. E. Thies, “Flex-

ible endoscopic treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum: a new

approach,” Endoscopy, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 438–442, 1995.

[6] S. Ishaq, C. Hassan, A. Antonello et al., “Flexible endoscopic

treatment for Zenker’s diverticulum: a systematic review and

meta-analysis,” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, vol. 83, no. 6,

pp. 1076–1089.e5, 2016.

[7] H. Feussner, “Zenker’s diverticulum: pro operation,” Chirurg,

vol. 82, no. 6, pp. 484–489, 2011.

[8] S. K. Gölder, J. Brueckner, A. Ebigbo, and H. Messmann,

“Double incision and snare resection in symptomatic Zenker’s

diverticulum: a modification of the stag beetle knife tech-

nique,” Endoscopy, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 137–141, 2018.

[9] P. B. Cotton, G. M. Eisen, L. Aabakken et al., “A lexicon for

endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop,”

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 446–454, 2010.

[10] S. K. Goelder, J. Brueckner, and H. Messmann, “Endoscopic

treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum with the stag beetle knife

(sb knife) - feasibility and follow-up,” Scandinavian Journal

of Gastroenterology, vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 1155–1158, 2016.

[11] M. Dakkak and J. R. Bennett, “A new dysphagia score with

objective validation,” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology,

vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 99-100, 1992.

[12] M. M. Brombart, Radiologie des Verdauungstraktes: Funktio-

nelle Untersuchung und Diagnostik, Georg Thieme Verlag:

Stuttgart, New York, 1980.

[13] V. Huberty, S. el Bacha, D. Blero, O. le Moine, S. Hassid, and

J. Devière, “Endoscopic treatment for Zenker’s diverticulum:

long-term results (with video),” Gastrointestinal Endoscopy,

vol. 77, no. 5, pp. 701–707, 2013.

[14] J. Verdonck and R. P. Morton, “Systematic review on treat-

ment of Zenker’s diverticulum,” European Archives of Oto-

Rhino-Laryngology, vol. 272, no. 11, pp. 3095–3107, 2015.

[15] G. Costamagna, F. Iacopini, A. Bizzotto et al., “Prognostic var-

iables for the clinical success of flexible endoscopic septotomyYou can also read