EFFECTIVENESS OF PUBLIC HEALTH MEASURES IN REDUCING THE INCIDENCE OF COVID-19, SARS-COV-2 TRANSMISSION, AND COVID-19 MORTALITY: SYSTEMATIC REVIEW ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

RESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Effectiveness of public health measures in reducing the incidence

of covid-19, SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and covid-19 mortality:

systematic review and meta-analysis

Stella Talic,1,2 Shivangi Shah,1 Holly Wild,1,3 Danijela Gasevic,1,4 Ashika Maharaj,1

Zanfina Ademi,1,2 Xue Li,4,6 Wei Xu,4 Ines Mesa-Eguiagaray,4 Jasmin Rostron,4

Evropi Theodoratou,4,5 Xiaomeng Zhang,4 Ashmika Motee,4 Danny Liew,1,2 Dragan Ilic1

1

School of Public Health and ABSTRACT 37 assessed multiple public health measures as a

Preventive Medicine, Monash OBJECTIVE “package of interventions.” Eight of 35 studies were

University, Melbourne, 3004 VIC, To review the evidence on the effectiveness of included in the meta-analysis, which indicated a

Australia

2 public health measures in reducing the incidence of reduction in incidence of covid-19 associated with

Monash Outcomes Research

and health Economics (MORE) covid-19, SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and covid-19 handwashing (relative risk 0.47, 95% confidence

Unit, Monash University, VIC, mortality. interval 0.19 to 1.12, I2=12%), mask wearing (0.47,

Australia 0.29 to 0.75, I2=84%), and physical distancing (0.75,

3

DESIGN

Torrens University, VIC, Australia 0.59 to 0.95, I2=87%). Owing to heterogeneity of

4

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Centre for Global Health, The the studies, meta-analysis was not possible for the

Usher Institute, University of DATA SOURCES

Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK outcomes of quarantine and isolation, universal

Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Biosis, Joanna Briggs,

5

Cancer Research UK Edinburgh lockdowns, and closures of borders, schools, and

Global Health, and World Health Organization

Centre, MRC Institute of Genetics workplaces. The effects of these interventions were

COVID-19 database (preprints).

and Molecular Medicine, synthesised descriptively.

University of Edinburgh, ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR STUDY SELECTION

Edinburgh, UK CONCLUSIONS

Observational and interventional studies that

6

School of Public Health and This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests

assessed the effectiveness of public health measures

The Second Affiliated Hospital, that several personal protective and social measures,

Zhejiang University School of in reducing the incidence of covid-19, SARS-CoV-2

including handwashing, mask wearing, and physical

Medicine, Hangzhou, China transmission, and covid-19 mortality.

distancing are associated with reductions in the

Correspondence to: S Talic MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

stella.talic@monash.edu incidence covid-19. Public health efforts to implement

(ORCID 0000-0001-7739-3381) The main outcome measure was incidence of public health measures should consider community

Additional material is published covid-19. Secondary outcomes included SARS-CoV-2 health and sociocultural needs, and future research

online only. To view please visit transmission and covid-19 mortality. is needed to better understand the effectiveness of

the journal online.

DATA SYNTHESIS public health measures in the context of covid-19

Cite this as: BMJ 2021;375:e068302

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ DerSimonian Laird random effects meta-analysis was vaccination.

bmj-2021-068302 performed to investigate the effect of mask wearing, SYSTEMATIC REVIEW REGISTRATION

Accepted: 21 October 2021 handwashing, and physical distancing measures PROSPERO CRD42020178692.

on incidence of covid-19. Pooled effect estimates

with corresponding 95% confidence intervals were

computed, and heterogeneity among studies was Introduction

assessed using Cochran’s Q test and the I2 metrics, The impact of SARS-CoV-2 on global public health and

with two tailed P values. economies has been profound.1 As of 14 October 2021,

there were 239 007 759 million cases of confirmed

RESULTS

covid-19 and 4 871 841 million deaths with covid-19

72 studies met the inclusion criteria, of which 35

worldwide.2

evaluated individual public health measures and

A variety of containment and mitigation strategies

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC have been adopted to adequately respond to covid-19,

with the intention of deferring major surges of patients

Public health measures have been identified as a preventive strategy for

in hospitals and protecting the most vulnerable

influenza pandemics

people from infection, including elderly people and

The effectiveness of such interventions in reducing the transmission of SARS- those with comorbidities.3 Strategies to achieve these

CoV-2 is unknown goals are diverse, commonly based on national risk

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS assessments that include estimation of numbers of

patients requiring hospital admission and availability

The findings of this review suggest that personal and social measures, including

of hospital beds and ventilation support.

handwashing, mask wearing, and physical distancing are effective at reducing

Globally, vaccination programmes have proved

the incidence of covid-19

to be safe and effective and save lives.4 5 Yet most

More stringent measures, such as lockdowns and closures of borders, schools, vaccines do not confer 100% protection, and it is not

and workplaces need to be carefully assessed by weighing the potential negative known how vaccines will prevent future transmission

effects of these measures on general populations of SARS-CoV-2,6 given emerging variants.7-9 The

Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of public health measures proportion of the population that must be vaccinated

after adequate vaccination coverage against covid-19 to reach herd immunity depends

the bmj | BMJ 2021;375:e068302 | doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 1RESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

greatly on current and future variants.10 This public health measures, particularly in policy decision

vaccination threshold varies according to the country making.19

and population’s response, types of vaccines, groups Previous systematic reviews on the effectiveness of

prioritised for vaccination, and viral mutations, public health measures to treat covid-19 lacked the

among other factors.6 Until herd immunity to covid-19 inclusion of analytical studies,20 a comprehensive

is reached, regardless of the already proven high approach to data synthesis (focusing only on one

vaccination rates,11 public health preventive strategies measure),21 a rigorous assessment of effectiveness

are likely to remain as first choice measures in disease of public health measures,22 an assessment of the

prevention,12 particularly in places with a low uptake certainty of the evidence,23 and robust methods for

of covid-19 vaccination. Measures such as lockdown comparative analysis.24 To tackle these gaps, we

(local and national variant), physical distancing, performed a systematic review of the evidence on the

mandatory use of face masks, and hand hygiene have effectiveness of both individual and multiple public

been implemented as primary preventive strategies to health measures in reducing the incidence of covid-19,

curb the covid-19 pandemic.13 SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and covid-19 mortality.

Public health (or non-pharmaceutical) interventions When feasible we also did a critical appraisal of the

have been shown to be beneficial in fighting respiratory evidence and meta-analysis.

infections transmitted through contact, droplets,

and aerosols.14 15 Given that SARS-CoV-2 is highly Methods

transmissible, it is a challenge to determine which This systematic review and meta-analysis

measures might be more effective and sustainable for were conducted in accordance with PRISMA25

further prevention. (supplementary material 1, table 1) and with

Substantial benefits in reducing mortality were PROSPERO (supplementary material 1, table 2).

observed in countries with universal lockdowns in

place, such as Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Eligibility criteria

and China. Universal lockdowns are not, however, Articles that met the population, intervention,

sustainable, and more tailored interventions need comparison, outcome, and study design criteria

to be considered; the ones that maintain social lives were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review

and keep economies functional while protecting (supplementary material 1, table 3). Specifically,

high risk individuals.16 17 Substantial variation exists preventive public health measures that were tested

in how different countries and governments have independently were included in the main analysis.

applied public health measures,18 and it has proved a Multiple measures, which generally contain a “package

challenge for assessing the effectiveness of individual of interventions”, were included as supplementary

material owing to the inability to report on the

individual effectiveness of measures and comparisons

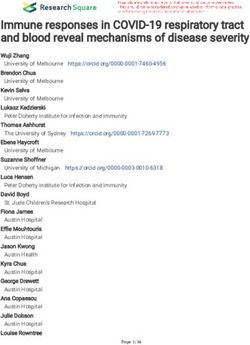

Visual Abstract Hands, face, space v covid-19 on which package led to enhanced outcomes. The

Effectiveness of public health measures

public health measures were identified from published

Summary Several public health measures, including handwashing, mask World Health Organization sources that reported

wearing, and physical distancing, were associated with a reduction on the effectiveness of such measures on a range of

in incidence of covid-

communicable diseases, mostly respiratory infections,

Study design such as influenza.

72 Met inclusion criteria 37 Excluded from analysis Given that the scientific community is concerned

Systematic review

and meta-analysis

Assessed multiple measures about the ability of the numerous mathematical

as a “package of interventions”

Evaluated individual models, which are based on assumptions, to predict

35

Risk of bias measures the course of virus transmission or effectiveness of

0 Low 27 Excluded from analysis interventions,26 this review focused only on empirical

6 Medium Owing to heterogeneity of studies studies. We excluded case reports and case studies,

2 Serious 8 Included in meta-analysis (effects synthesised descriptively)

modelling and simulation studies, studies that

provided a graphical summary of measures without

3 6 5 clear statistical assessments or outputs, ecological

studies that provided a descriptive summary of the

measures without assessing linearity or having

Assessed handwashing Assessed mask wearing Assessed physical distancing

comparators, non-empirical studies (eg, commentaries,

editorials, government reports), other reviews, articles

involving only individuals exposed to other pathogens

Outcomes Relative risk % CI

that can cause respiratory infections, such as severe

Random effects model results . .

acute respiratory syndrome or Middle East respiratory

Handwashing

syndrome, and articles in a language other than English.

Mask wearing

Physical distancing Information sources

http://bit.ly/BMJc19phm © 2021 BMJ Publishing group Ltd. We carried out electronic searches of Medline,

Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and

2 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 | BMJ 2021;375:e068302 | the bmjRESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Allied Health Literature, Ebsco), Global Health, Biosis, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals were

Joanna Briggs, and the WHO COVID-19 database (for reported for the associations between the public

preprints). A clinical epidemiologist (ST) developed health measures and incidence of covid-19. When

the initial search strategy, which was validated by two necessary, we transformed effect metrics derived from

senior medical librarians (LR and MD) (supplementary different studies to allow pooled analysis. We used the

material 1, table 4). The updated search strategy was Dersimonian Laird random effects model to estimate

last performed on 7 June 2021. All citations identified pooled effect estimates along with corresponding 95%

from the database searches were uploaded to confidence intervals for each measure. Heterogeneity

Covidence, an online software designed for managing among individual studies was assessed using

systematic reviews,27 for study selection. the Cochran Q test and the I2 test.31 All statistical

analyses were conducted in R (version 4.0.3) and all

Study selection P values were two tailed, with P=0.05 considered to

Authors ST, DG, SS, AM, ET, JR, XL, WX, IME, and XZ be significant. For the remaining studies, when meta-

independently screened the titles and abstracts and analysis was not feasible, we reported the results in a

excluded studies that did not match the inclusion narrative synthesis.

criteria. Discrepancies were resolved in discussion

with the main author (ST). The same authors retrieved Public and patient involvement

full text articles and determined whether to include No patients or members of the public were directly

or exclude studies on the basis of predetermined involved in this study as no primary data were

selection criteria. Using a pilot tested data extraction collected. A member of the public was, however, asked

form, authors ST, SS, AM, JR, XL, WX, AM, IME, and to read the manuscript after submission.

XZ independently extracted data on study design,

intervention, effect measures, outcomes, results, and Results

limitations. ST, SS, AM, and HW verified the extracted A total of 36 729 studies were initially screened,

data. Table 5 in supplementary material 1 provides of which 36 079 were considered irrelevent. After

the specific criteria used to assess study designs. exclusions, 650 studies were eligible for full text

Given the heterogeneity and diversity in how studies review and 72 met the inclusion criteria. Of these

defined public health measures, we took a common studies, 35 assessed individual interventions and were

approach to summarise evidence of these interventions included in the final synthesis of results (fig 1) and 37

(supplementary material 1, table 6). assessed multiple interventions as a package and are

included in supplementary material 3, tables 2 and

Risk of bias within individual studies 3. The included studies comprised 34 observational

SS, JR, XL, WX, IME, and XZ independently assessed studies and one interventional study, eight of which

risk of bias for each study, which was cross checked were included in the meta-analysis.

by ST and HW. For non-interventional observational

studies, a ROBINS-I (risk of bias in non-randomised Risk of bias

studies of interventions) risk of bias tool was used.28 According to the ROBINS-I tool,28 the risk of bias was

For interventional studies, a revised tool for assessing rated as low in three studies,32-34 moderate in 24

risk of bias in randomised trials (RoB 2) tool was studies,35-58 and high to serious in seven studies.59-65

used.29 Reviewers rated each domain for overall risk of One important source of serious or critical risk of bias

bias as low, moderate, high, or serious/critical. in most of the included studies was major confounding,

which was difficult to control for because of the novel

Data synthesis nature of the pandemic (ie, natural settings in which

The DerSimonian and Laird method was used for multiple interventions might have been enforced at

random effects meta-analysis, in which the standard once, different levels of enforcement across regions,

error of the study specific estimates was adjusted to and uncaptured individual level interventions

incorporate a measure of the extent of variation, or such as increased personal hygiene). Variations in

heterogeneity, among the effects observed for public testing capacity and coverage, changes to diagnostic

health measures across different studies. It was criteria, and access to accurate and reliable outcome

assumed that the differences between studies are a data on covid-19 incidence and covid-19 mortality,

result of different, yet related, intervention effects being was a source of measurement bias for numerous

estimated. If fewer than five studies were included in studies (fig 2). These limitations were particularly

meta-analysis, we applied a recommended modified prominent early in the pandemic, and in low income

Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method.30 environments.47 52 62 63 65 The randomised controlled

trial66 was rated as moderate risk of bias according

Statistical analysis to the ROB-2 tool. Missing data, losses to follow-up,

Because of the differences in the effect metrics lack of blinding, and low adherence to intervention

reported by the included studies, we could only all contributed to the reported moderate risk. Tables 1

perform quantitative data synthesis for three and 2 in supplementary material 2 summarise the risk

interventions: handwashing, face mask wearing, of bias assessment for each study assessing individual

and physical distancing. Odds ratios or relative risks measures.

the bmj | BMJ 2021;375:e068302 | doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 3RESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

51 878

States (n=9), Europe (n=7), the Middle East (n=3), Africa

Records identified (n=3), South America (n=1), and Australia (n=1). Thirty

18 532 Embase 6901 CINAHL 3173 Preprints WHO four of the studies were observational and one was a

15 399 Medline 7873 Joanna Briggs, Biosis, COVID-19 randomised controlled trial. The study designs of the

and Global Health database observational studies comprised natural experiments

(n=11), quasi-experiments (n=3), a prospective cohort

15 149 (n=1), retrospective cohorts (n=8), case-control (n=2),

Duplicates and cross sectional (n=9). Twenty six studies assessed

social measures,32 34 35 37-42 44 46-48 52 53 55-61 63-65 67

36 729 12 studies assessed personal protective

Records screened measures,36 43 45 49 50 57 58 60 63 66 68 three studies assessed

travel related measures,54 58 62 and one study assessed

36 079 environmental measures57 (some interventions

Records excluded overlapped across studies). The most commonly

measured outcome was incidence of covid-19 (n=18),

650 followed by SARS-CoV-2 transmission, measured as

Full text articles assessed reproductive number, growth number, or epidemic

doubling time (n=13), and covid-19 mortality (n=8).

578 Table 1 in supplementary material 3 provides detailed

Full text articles excluded

information on each study.

148 Inadequate study design

120 Editorials or commentaries

136 Simulation studies Effects of interventions

89 No reported or ineligible outcomes Personal protective measures

33 Ineligible setting or population Handwashing and covid-19 incidence—Three studies

15 Ineligible intervention

15 Reports with a total of 292 people infected with SARS-CoV-2 and

22 Duplicates 10 345 participants were included in the analysis of the

effect of handwashing on incidence of covid-19.36 60 63

72 Overall pooled analysis suggested an estimated 53%

Total non-statistically significant reduction in covid-19

35 Studies assessing individual interventions incidence (relative risk 0.47, 95% confidence interval

8 Included in quantitative synthesis 0.19 to 1.12, I2=12%) (fig 3). A sensitivity analysis

27 Included in qualitative synthesis

37 Studies assessing multiple interventions (see supplementary material) without adjustment showed a significant reduction in

covid-19 incidence (0.49, 0.33 to 0.72, I2=12%) (fig

Fig 1 | Flow of articles through the review. WHO=World Health Organization 4). Risk of bias across the three studies ranged from

moderate36 60 to serious or critical63 (fig 2).

Study characteristics Mask wearing and covid-19 incidence—Six studies

Studies assessing individual measures with a total of 2627 people with covid-19 and 389 228

Thirty five studies provided estimates on the participants were included in the analysis examining the

effectiveness of an individual public health measures. effect of mask wearing on incidence of covid-19 (table

The studies were conducted in Asia (n=11), the United 1).36 43 57 60 63 66 Overall pooled analysis showed a 53%

reduction in covid-19 incidence (0.47, 0.29 to 0.75),

Risk of bias although heterogeneity between studies was substantial

Serious or critical High Moderate Low (I2=84%) (fig 5). Risk of bias across the six studies ranged

40 from moderate36 57 60 66 to serious or critical43 63 (fig 2).

No of studies

Mask wearing and transmission of SARS-CoV-2,

30 covid-19 incidence, and covid-19 mortality—The results

of additional studies that assessed mask wearing (not

included in the meta-analysis because of substantial

20

differences in the assessed outcomes) indicate

a reduction in covid-19 incidence, SARS-CoV-2

10 transmission, and covid-19 mortality. Specifically,

a natural experiment across 200 countries showed

0 45.7% fewer covid-19 related mortality in countries

where mask wearing was mandatory (table 1).49

M sult of

om nt

ta

tio om

t n

Co udy f

g

st n o

in

en tio

da

tc e

Another natural experiment study in the US reported a

s

iss e

ns

an Se ion

re n

nd

en fr

ou rem

d tio

to io

rv ca

g

rv n

in ct

ou

in

fi

rte lec

te io

29% reduction in SARS-CoV-2 transmission (measured

of su

i

ts le

in ss

nf

in viat

po Se

ea

of Cla

M

e

ed e

t

as the time varying reproductive number Rt) (risk ratio

nd D

re

0.71, 95% confidence interval 0.58 to 0.75) in states

cip

rti

te

where mask wearing was mandatory.58

pa

in

Fig 2 | Summary of risk of bias across studies assessing individual measures using risk A comparative study in the Hong Kong Special

of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions (ROBINS-I) tool Administrative Region reported a statistically

4 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 | BMJ 2021;375:e068302 | the bmjRESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Study Intervention Relative risk Weight Relative risk

(95% CI) (%) (95% CI)

Doung-Ngern 2020

Handwashing 19.1 0.34 (0.13 to 0.88)

Lio 2021 Handwashing 17.8 0.30 (0.11 to 0.81)

Xu 2020 Handwashing 63.1 0.58 (0.40 to 0.84)

Random effects model (adjusted) Handwashing 100.0 0.47 (0.19 to 1.12)

Test for heterogeneity: τ2=0.053; P=0.32; I2=12%

0.1 0.5 1 2 5

Fig 3 | Meta-analysis of evidence on association between handwashing and incidence of covid-19 using modified

Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman adjusted random effect model

significant lower cumulative incidence of covid-19 on the incidence of covid-19.37 53 57 60 63 Overall pooled

associated with mask wearing than in selected countries analysis indicated a 25% reduction in incidence of

where mask wearing was not mandatory (table 1).68 covid-19 (relative risk 0.75, 95% confidence interval

Similarly, another natural experiment involving 15 0.59 to 0.95, I2=87%) (fig 6). Heterogeneity among

US states reported a 2% statistically significant daily studies was substantial, and risk of bias ranged from

decrease in covid-19 transmission (measured as case moderate37 53 57 60 to serious or critical63 (fig 2).

growth rate) at ≥21 days after mask wearing became

mandatory,50 whereas a cross sectional study reported Physical distancing and transmission of SARS-CoV-2

that a 10% increase in self-reported mask wearing and covid-19 mortality

was associated with greater odds for control of SARS- Studies that assessed physical distancing but were not

CoV-2 transmission (adjusted odds ratio 3.53, 95% included in the meta-analysis because of substantial

confidence interval 2.03 to 6.43).45 The five studies differences in outcomes assessed, generally reported

were rated at moderate risk of bias (fig 2). a positive effect of physical distancing (table 2). A

natural experiment from the US reported a 12%

Environmental measures decrease in SARS-CoV-2 transmission (relative risk

Disinfection in household and covid-19 incidence 0.88, 95% confidence interval 0.86 to 0.89),40 and

Only one study, from China, reported the association a quasi-experimental study from Iran reported a

between disinfection of surfaces and risk of secondary reduction in covid-19 related mortality (β −0.07,

transmission of SARS-CoV-2 within households (table 95% confidence interval −0.05 to −0.10; PRESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Table 1 | Study characteristics and main results from studies that assessed individual personal protective and environmental measures

Public health Outcome Study Risk of

Reference, country Study design measure Sample size measure duration Effect estimates: conclusions bias

Doung-Ngern et al,63 Case-control Handwashing 211 cases, 839 Incidence 1-31 MarRegular handwashing: adjusted odds Serious or

Thailand controls 2020 ratio 0.34 (95% confidence interval 0.13 critical

to 0.87): associated with lower risk of

SARS-CoV-2*

Lio et al,36 China Case-control Handwashing 24 cases, 1113 Incidence 17 Mar-15 Adjusted odds ratio 0.30 (95% Moderate

controls Apr 2020 confidence interval 0.11 to 0.80):

reduction in odds of becoming

infectious*

Xu et al,60 China Cross sectional Handwashing n=8158 Incidence 22 Feb-5 Mar Relative risk 3.53 (95% confidence Moderate

comparative 2020 interval 1.53 to 8.15): significantly

increased risk of infection with no

handwashing*

Bundgaard et al,66 Randomised Mask wearing 2392 cases, 2470 Incidence Apr and May Odds ratio 0.82 (95% confidence Moderate

Denmark controlled controls 2020 interval 0.54 to 1.23): 46% reduction to

23% increase in infection*

Doung-Ngern et al,63 Case-control Mask wearing 211 cases, 839 Incidence 1-31 Mar Adjusted odds ratio 0.23 (95% Serious or

Thailand controls 2020 confidence interval 0.09 to 1.60): critical

associated with lower risk of SARS-CoV-2

infection*

Lio et al,36 China Case-control Mask wearing 24 cases, 1113 Incidence 17 Mar-15 Odds ratio 0.30 (95% confidence Moderate

controls Apr 2020 interval 0.10 to 0.86): 70% risk

reduction*

Xu et al,60 China Cross sectional Mask wearing 8158 people Incidence 22 Feb-5 Mar Relative risk 12.38 (95% confidence Moderate

comparative 2020 interval 5.81 to 26.36): significantly

increased risk of infection*

Krishnamachari et al,43 Natural Mask wearing 50 states Incidence Apr 2020 3-6 months, adjusted odds ratio 1.61 Serious or

US experiment (cumulative rate) (95% confidence interval 1.23 to 2.10): critical

>6 months, 2.16 (1.64 to 2.88): higher

incidence rate with later mask mandate

than with mask mandate in first month*

Wang et al,57 China Retrospective Mask wearing 335 people Incidence 28 Feb-27 Odds ratio 0.21 (95% confidence Moderate

cohort (assessed as Mar 2020 interval 0.06 to 0.79): 79% reduction in

attack rate†) transmission of SARS-CoV-2*

Cheng et al,68 China Longitudinal Mask wearing 961 cases (HKSAR), Incidence 31 Dec 2019- Incidence rate 49.6% (South Korea) v Moderate

comparative (South Korea v average control not 8 Apr 2020 11.8% (HKSAR) PRESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Study Intervention Relative risk Weight Relative risk

(95% CI) (%) (95% CI)

Bundagaard 2021 Mask wearing 22.2 0.82 (0.54 to 1.24)

Doung-Ngern 2020 Mask wearing 7.6 0.23 (0.05 to 0.97)

Krishnamachari 2021 Mask wearing 26.6 0.77 (0.71 to 0.84)

Lio 2021 Mask wearing 11.1 0.30 (0.10 to 0.88)

Xu 2020 Mask wearing 23.6 0.34 (0.24 to 0.48)

Wang 2020 Mask wearing 8.9 0.21 (0.06 to 0.76)

Random effects model Mask wearing 100.0 0.47 (0.29 to 0.75)

Test for heterogeneity: τ2=0.214; PRESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Table 2 | Study characteristics and main results from studies assessing individual social measures

Public health Study dura- Risk of

Reference, country Study design measure Sample size Outcome tion Effect estimates: conclusions bias

Jarvis et al,65 UK Cross sectional Stay at home 1356 cases R0 Feb-24 Mar R0: pre-intervention 3.6, post-intervention 0.60 Serious or

or isolation 2020 (95% confidence interval 0.37 to 0.89): 3.0 R0 critical

decrease

Khosravi et al,55 Iran Cross sectional Stay at home 993 cases R0 20 Feb-01 Apr R0: pre-intervention 2.70 (95% confidence Moderate

or isolation 2020 interval 2.10 to 3.40), post-intervention 1.13

(1.03 to 1.25): 1.5 R0 decrease

Dreher et al,41 US Retrospective Stay at home 49 states and R0 NS Odds ratio 0.07 (95% confidence interval 0.01 Low

cohort or isolation territories to 0.37): decrease in odds of having a positive

R0 result*

Liu et al,58 US Natural Stay at home 50 states Rt 21 Jan-31 May Risk ratio 0.49 (95% confidence interval 0.43 to Moderate

experiment or isolation 2020 0.54): contributed about 51% to reduction in Rt*

Alfano et al,52 Italy Natural Lockdown 202 countries, Incidence 22 Jan-10 May β coefficient −235.8 (standard error −11.04), Serious or

experiment 22 018 people 2020 PRESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Table 2 | Continued

Public health Study dura- Risk of

Reference, country Study design measure Sample size Outcome tion Effect estimates: conclusions bias

Guo et al,40 US Natural Business 50 states and one Rt 29 Jan-31 July Relative risk 0.88 (95% confidence interval 0.86 Moderate

experiment closure territory (Virgin 2020 to 0.89): associated with 12% decrease in risk

Islands) of Rt*

Voko et al,53 Europe Natural Physical 28 countries Incidence 1 Feb-18 Apr Incidence rate ratio 1.23 (95% confidence Moderate

experiment distancing 2020 interval 1.19 to 1.28), 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99): 26%

decrease in incidence*

Van den Berg et Retrospective Physical 99 390 staff Incidence 24 Sep 2020- ≥3 v ≥6 feet adjusted incidence rate ratio 1.01 Moderate

al,37 US cohort distancing (adjusted) 27 Jan 2021 (95% confidence interval 0.75 to 1.36), larger

physical distancing not associated with lower

rates of SARS-CoV-2*‡

Xu et al,60 China Cross sectional Physical 8158 people Incidence 22 Feb-5 Mar Relative risk 2.63 (95% confidence interval 1.48 Moderate

comparative distancing 2020 to 4.67): significantly increased risk of infection*

Doung-Ngern et al,63 Case-control Physical 211 cases, 839 Incidence 1-31 Mar >1m physical distance adjusted odds ratio Serious or

Thailand distancing controls 2020 0.15; 95% confidence interval 0.04 to 0.63)): critical

associated with lower risk of SARS-CoV-2

infection*

Wang et al,57 China Retrospective Physical 335 people Incidence 28 Feb-27 Mar Odds ratio 18.26 (95% confidence interval 3.93 Moderate

cohort distancing (proportions 2020 to 84.79): risk of household transmission was

assessed as 18 times higher with frequent daily close contact

attack rate†) with the primary case*

Alimohamadi et al,47 Quasi- Physical NS Incidence, 20 Feb-13 Incidence β coefficient −1.70 (95% confidence Serious or

Iran experimental distancing mortality May 2020 interval −2.3 to 1.1), mortality β coefficient critical

−0.07 (−0.05 to −0.10): reduced incidence and

mortality*

Quaife et al,61 Africa Cross-sectional Physical 237 cases R0 1 -31 May R0: pre-intervention 2.64, post-intervention 0.60 Moderate

comparative distancing 2020 (interquartile range 0.50-0.68): 2.04 decrease

in R0

Guo et al,40 US Natural Physical 50 states and one Rt 29 Jan-31 Jul Relative risk 0.88 (95% confidence interval 0.86 Moderate

experiment distancing territory (Virgin 2020 to 0.89): associated with a 12% decrease in risk

Islands) of Rt*

R0=reproductive number; Rt=time varying reproductive number.

*Interpretation of findings as reported in the original manuscript.

†Percentage of individuals who tested positive over a specified period.

‡Not an effective intervention.

retrospective cohort study observed a 14.1% reduction reported that lockdown was associated with an 11%

in risk after implementation of universal lockdown reduction in transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (relative risk

(table 2).46 These studies were rated at high risk of 0.89, 95% confidence interval 0.88 to 0.91).40 All the

bias52 and moderate risk of bias46 56 (fig 2). studies were rated at low risk of bias33 39 to moderate

risk40 64 (fig 2).

Lockdown and covid-19 mortality

The three studies that assessed universal lockdown Travel related measures

and covid-19 mortality generally reported a decrease Restricted travel and border closures

in mortality (table 2).35 38 42 A natural experiment study Border closure was assessed in one natural experiment

involving 45 US states reported a decrease in covid-19 study involving nine African countries (table 3).62

related mortality of 2.0% (95% confidence interval Overall, the countries recorded an increase in the

−3.0% to 0.9%) daily after lockdown had been made incidence of covid-19 after border closure. These

mandatory.35 A Brazilian quasi-experimental study studies concluded that the implementation of border

reported a 27.4% average difference in covid-19 related closures within African countries had minimal effect

mortality rates in the first 25 days of lockdown.42 In on the incidence of covid-19. The study had important

addition, a natural experiment study reported about limitations and was rated at serious or critical risk of

30% and 60% reductions in covid-19 related mortality bias. In the US, a natural experiment study reported that

post-lockdown in Italy and Spain over four weeks post- restrictions on travel between states contributed about

intervention, respectively.38 All three studies were 11% to a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 transmission (table

rated at moderate risk of bias (fig 2). 3).36 The study was rated at moderate risk of bias (fig 2).

Lockdown and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Entry and exit screening (virus or symptom screening)

Four studies assessed universal lockdown and One retrospective cohort study assessed screening of

transmission of SARS-CoV-2 during the first few symptoms, which involved testing 65 000 people for

months of the pandemic (table 2). The decrease in fever (table 3).54 The study found that screening for

reproductive number (R0) ranged from 1.27 in Italy fever lacked sensitivity (ranging from 18% to 24%)

(pre-intervention 2.03, post-intervention 0.76)39 to in detecting people with SARS-CoV-2 infection. This

2.09 in India (pre-intervention 3.36, post-intervention translated to 86% of the population with SARS-CoV-2

1.27),64 and 3.97 in China (pre-intervention 4.95, post- remaining undetected when screening for fever. The

intervention 0.98).33 A natural experiment from the US study was rated at moderate risk of bias (fig 2).

the bmj | BMJ 2021;375:e068302 | doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 9RESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Table 3 | Study characteristics and main results from studies that assessed individual travel measures

Reference, Public health Outcome

country Study design measure Sample size measure Study duration Effect estimates: conclusions Risk of bias

Emeto et al,62 Natural Border closure 9 countries Rt 14 Feb-19 Jul See supplementary table for data on all countries: Serious or

Africa experiment 2020 minimal effect on reducing transmission (Rt)*† critical

Liu et al,58 Natural Interstate travel 50 states Rt 21 Jan-31 May Risk ratio 0.89 (95% confidence interval 0.84 to Moderate

USA experiment restrictions 2020 0.95): contributed about 11% to reduction in Rt*

Mitra et al,54 Retrospective Screening for fever 65 000 people Daily growth 9 Mar-13 May Sensitivity 24%: 86% of cases not detected—poor Moderate

Australia cohort rate 2020 sensitivity of identifying people with SARS-CoV-2*

R0=reproductive number; Rt=time varying reproductive number.

*Interpretation of findings as reported in the original manuscript.

†Not an effective intervention

Multiple public health measures small number of individual studies (RESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Comparison with other studies Empirical evidence from restricted travel and

Previous literature reviews have identified mask wearing full border closures is also limited, as it is almost

as an effective measure for the containment of SARS- impossible to study these strategies as single

CoV-2103; the caveat being that more high level evidence measures. Current evidence from a recent narrative

is required to provide unequivocal support for the literature review suggested that control of movement,

effectiveness of the universal use of face masks.104 105 along with mandated quarantine, travel restrictions,

Additional empirical evidence from a recent randomised and restricting nationals from entering areas of

controlled trial (originally published as a preprint) high infection, are effective measures, but only with

indicates that mask wearing achieved a 9.3% reduction good compliance.122 A narrative literature review

in seroprevalence of symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection of travel bans, partial lockdowns, and quarantine

and an 11.9% reduction in the prevalence of covid-19- also suggested effectiveness of these measures,123

like symptoms.106 Another systematic review showed and another rapid review further supported travel

stronger effectiveness with the use of N95, or similar, restrictions and cross border restrictions to stop the

respirators than disposable surgical masks,107 and a spread of SARS-CoV-2.124 It was impossible to make

study evaluating the protection offered by 18 different such observations in the current review because of

types of fabric masks found substantial heterogeneity limited evidence. A German review, however, suggested

in protection, with the most effective mask being that entry, exit, and symptom screening measures to

multilayered and tight fitting.108 However, transmission prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 are not effective

of SARS-CoV-2 largely arises in hospital settings in which at detecting a meaningful proportion of cases,125 and

full personal protective measures are in place, which another review using real world data from multiple

suggests that when viral load is at its highest, even the countries found that border closures had minimal

best performing face masks might not provide adequate impact on the control of covid-19.126

protection.51 Additionally, most studies that assessed Although universal lockdowns have shown a

mask wearing were prone to important confounding protective effect in lowering the incidence of covid-19,

bias, which might have altered the conclusions drawn SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and covid-19 mortality,

from this review (ie, effect estimates might have been these measures are also disruptive to the psychosocial

underestimated or overestimated or can be related to and mental health of children and adolescents,127 global

other measures that were in place at the time the studies economies,128 and societies.129 Partial lockdowns

were conducted). Thus, the extent of such limitations on could be an alternative, as the associated effectiveness

the conclusions drawn remain unknown. can be high,125 especially when implemented early

A 2020 rapid review concluded that quarantine is in an outbreak,85 and such measures would be less

largely effective in reducing the incidence of covid-19 disruptive to the general population.

and covid-19 mortality. However, uncertainty over It is important to also consider numerous sociopolitical

the magnitude of such an effect still remains,109 and socioeconomic factors that have been shown to

with enhanced management of quality quarantine increase SARS-CoV-2 infection130 131 and covid-19

facilities for improved effective control of the mortality.132 Immigration status,82 economic status,81

101

epidemics urgently needed.110 In addition, findings and poverty and rurality98 can influence individual

on the application of school and workplace closures and community compliance with public health

are still inconclusive. Policy makers should be measures. Poverty can impact the ability of communities

aware of the ambiguous evidence when considering to physically distance,133 especially in crowded living

school closures, as other potentially less disruptive environments,134 135 as well as reduce access to personal

physical distancing interventions might be more protective measures.134 135 A recent study highlights

appropriate.21 Numerous findings from studies on that “a one size fits all” approach to public health

the efficacy of school closures showed that the risk measures might not be effective at reducing the spread

of transmission within the educational environment of SARS-CoV-2 in vulnerable communities136 and could

often strongly depends on the incidence of covid-19 exacerbate social and economic inequalities.135 137

in the community, and that school closures are most As such, a more nuanced and community specific

successfully associated with control of SARS-CoV-2 approach might be required. Even though screening is

transmission when other mitigation strategies are in highly recommended by WHO138 because a proportion

place in the community.111-117 School closures have of patients with covid-19 can be asymptomatic,138

been reported to be disruptive to students globally and screening for symptoms might miss a larger proportion

are likely to impair children’s social, psychological, of the population with covid-19. Hence, temperature

and educational development118 119 and to result in screening technologies might need to be reconsidered

loss of income and productivity in adults who cannot and evaluated for cost effectiveness, given such measures

work because of childcare responsibilities.120 are largely depended on symptomatic fever cases.

Speculation remains as how best to implement

physical distancing measures.121 Studies that assess Strengths and limitations of this review

physical distancing measures might interchangeably The main strength of this systematic review was the

study physical distancing with lockdown35 52 56 64 use of a comprehensive search strategy to identify and

and other measures and thus direct associations are select studies for review and thereby minimise selection

difficult to assess. bias. A clinical epidemiologist developed the search

the bmj | BMJ 2021;375:e068302 | doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 11RESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

strategy, which was validated by two senior medical covid-19. The narrative results of this review indicate

librarians. This review followed a comprehensive an effectiveness of both individual or packages of

appraisal process that is recommended by the public health measures on the transmission of SARS-

Cochrane Collaboration31 to assess the effectiveness CoV-2 and incidence of covid-19. Some of the public

of public health measures, with specifically validated health measures seem to be more stringent than

tools used to independently and individually assess others and have a greater impact on economies and

the risk of bias in each study by study design. the health of populations. When implementing public

This review has some limitations. Firstly, high quality health measures, it is important to consider specific

evidence on SARS CoV-2 and the effectiveness of public health and sociocultural needs of the communities

health measures is still limited, with most studies and to weigh the potential negative effects of the

having different underlying target variables. Secondly, public health measures against the positive effects

information provided in this review is based on current for general populations. Further research is needed to

evidence, so will be modified as additional data assess the effectiveness of public health measures after

become available, especially from more prospective adequate vaccination coverage has been achieved. It

and randomised studies. Also, we excluded studies is likely that further control of the covid-19 pandemic

that did not provide certainty over the effect measure, depends not only on high vaccination coverage and

which might have introduced selection bias and limited its effectiveness but also on ongoing adherence to

the interpretation of effectiveness. Thirdly, numerous effective and sustainable public health measures.

studies measured interventions only once and others We thank medical subject librarians Lorena Romero (LR) and Marshall

multiple times over short time frames (days v month, or Dozier (MD) for their expert advice and assistance with the study

no timeframe). Additionally, the meta-analytical portion search strategy.

of this study was limited by significant heterogeneity Contributors: ST, DG, DI, DL, and ZA conceived and designed the

study. ST, DG, SS, AM, HW, WX, JR, ET, AM, XL, XZ, and IME collected

observed across studies, which could neither be

and screened the data. ST, DG, and DI acquired, analysed, or

explored nor explained by subgroup analyses or meta- interpreted the data. ST, HW, and SS drafted the manuscript. All

regression. Finally, we quantitatively assessed only authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual

content.. XL and ST did the statistical analysis. NA obtained funding.

publications that reported individual measures; studies

LR and MD provided administrative, technical, or material support. ST

that assessed multiple measures simultaneously were and DI supervised the study. ST and DI had full access to all the data in

narratively analysed with a broader level of effectiveness the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the

accuracy of the data analysis. ST is the guarantor. The corresponding

(see supplementary material 3, table 3). Also, we

author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that

excluded studies in languages other than English. no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: No funding was available for this research. ET is supported

Methodological limitations of studies included in by a Cancer Research UK Career Development Fellowship (grant No

the review C31250/A22804). XZ is supported by The Darwin Trust of Edinburgh.

Several studies failed to define and assess for Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform

disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/and declare: ET

potential confounders, which made it difficult is supported by a Cancer Research UK Career Development Fellowship

for our review to draw a one directional or causal and XZ is supported by The Darwin Trust of Edinburgh; no financial

conclusion. This problem was mainly because we relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the

submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships

were unable to study only one intervention, given that or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

many countries implemented several public health Ethical approval: Not required.

measures simultaneously; thus it is a challenge to Data sharing: No additional data available.

disentangle the impact of individual interventions (ie, The lead author (ST) affirms that the manuscript is an honest,

physical distancing when other interventions could accurate, and transparent account of the study reported; no important

be contributing to the effect). Additionally, studies aspects of the study have been omitted. Dissemination to participants

and related patient and public communities: It is anticipated to

measured different primary outcomes and in varied disseminate the results of this research to wider community via press

ways, which limited the ability to statistically analyse release and social media platforms.

other measures and compare effectiveness. Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer

Further pragmatic randomised controlled trials and reviewed.

natural experiment studies are needed to better inform This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the

Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license,

the evidence and guide the future implementation of which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work

public health measures. Given that most measures non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different

depend on a population’s adherence and compliance, terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-

commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

it is important to understand and consider how

these might be affected by factors. A lack of data in 1 McKee M, Stuckler D. If the world fails to protect the economy,

the assessed studies meant it was not possible to COVID-19 will damage health not just now but also in the future. Nat

Med 2020;26:640-2. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0863-y.

understand or determine the level of compliance and 2 World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.

adherence to any of the measures. 2021. https://covid19.who.int/

3 Parodi SM, Liu VX. From Containment to Mitigation of COVID-19 in

the US. JAMA 2020;323:1441-2. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3882.

Conclusions and policy implications 4 Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Early effectiveness of

Current evidence from quantitative analyses indicates COVID-19 vaccination with BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine and

ChAdOx1 adenovirus vector vaccine on symptomatic disease,

a benefit associated with handwashing, mask wearing, hospitalisations and mortality in older adults in England. medRxiv

and physical distancing in reducing the incidence of 2021:2021.03.01.21252652.

12 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 | BMJ 2021;375:e068302 | the bmjRESEARCH

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 on 17 November 2021. Downloaded from http://www.bmj.com/ on 27 December 2021 by guest. Protected by copyright.

5 Chodick G, Tene L, Patalon T, et al. Assessment of Effectiveness of 29 Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for

1 Dose of BNT162b2 Vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 Infection 13 to 24 assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898.

Days After Immunization. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2115985. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4898.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15985. 30 Röver C, Knapp G, Friede T. Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman approach and

6 Anderson RM, Vegvari C, Truscott J, Collyer BS. Challenges in creating its modification for random-effects meta-analysis with few studies. BMC

herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection by mass vaccination. Lancet Med Res Methodol 2015;15:99. doi:10.1186/s12874-015-0091-1.

2020;396:1614-6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32318-7. 31 Higgins JPTTJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ. Welch VA, ed.

7 Khateeb J, Li Y, Zhang H. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.: Chichester,

and potential intervention approaches. Crit Care 2021;25:244. UK: Wiley; 2019. 2nd edn. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook.

doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03662-x. 32 Vlachos J, Hertegård E, B Svaleryd H. The effects of school closures on

8 Singh J, Pandit P, McArthur AG, Banerjee A, Mossman K. Evolutionary SARS-CoV-2 among parents and teachers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A

trajectory of SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants. Virol J 2021;18:166. 2021;118:e2020834118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2020834118.

doi:10.1186/s12985-021-01633-w. 33 Wang J, Liao Y, Wang X, et al. Incidence of novel coronavirus (2019-

9 Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, et al. The emerging SARS-CoV-2 nCoV) infection among people under home quarantine in Shenzhen,

variants of concern. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2021;8:20499361211024372. China. Travel Med Infect Dis 2020;37:101660. doi:10.1016/j.

doi:10.1177/20499361211024372. tmaid.2020.101660.

10 World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Herd 34 Al-Tawfiq JA, Sattar A, Al-Khadra H, et al. Incidence of COVID-19

immunity, lockdowns and COVID-19. 2020. www.who.int/news- among returning travelers in quarantine facilities: A longitudinal

room/q-a-detail/herd-immunity-lockdowns-and-covid-19 study and lessons learned. Travel Med Infect Dis 2020;38:101901-

11 Henry DA, Jones MA, Stehlik P, Glasziou PP. Effectiveness of 01. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101901.

COVID-19 vaccines: findings from real world studies. Med J Aust 35 Siedner MJ, Harling G, Reynolds Z, et al. Correction: Social distancing

2021;215:149-151.e1. doi:10.5694/mja2.51182. to slow the US COVID-19 epidemic: Longitudinal pretest-posttest

12 World Health Organization. COVID-19 strategy update. 2020. www. comparison group study. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003376.

who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid-strategy-update- doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003376.

14april2020.pdf?sfvrsn=29da3ba0_19 36 Lio CF, Cheong HH, Lei CI, et al. Effectiveness of personal

13 Hollingsworth TD, Klinkenberg D, Heesterbeek H, Anderson RM. protective health behaviour against COVID-19. BMC Public Health

Mitigation strategies for pandemic influenza A: balancing conflicting 2021;21:827. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10680-5.

policy objectives. PLoS Comput Biol 2011;7:e1001076-76. 37 Van den Berg P, Schechter-Perkins EM, Jack RS, et al. Effectiveness

doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001076. of 3 Versus 6 ft of Physical Distancing for Controlling Spread of

14 Aledort JE, Lurie N, Wasserman J, Bozzette SA. Non-pharmaceutical Coronavirus Disease 2019 Among Primary and Secondary Students

public health interventions for pandemic influenza: an evaluation and Staff: A Retrospective, Statewide Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis

of the evidence base. BMC Public Health 2007;7:208-08. 2021. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab230.

doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-208. 38 Tobías A. Evaluation of the lockdowns for the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic

15 World Health Organization. Non-pharmaceutical public health in Italy and Spain after one month follow up. Sci Total Environ

measures for mitigating the risk and impact of epidemic and 2020;725:138539. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138539.

pandemic influenza 2019. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/ 39 Guzzetta G, Riccardo F, Marziano V, et al; COVID-19 Working Group,2.

handle/10665/329438/9789241516839-eng.pdf?ua=1. Impact of a Nationwide Lockdown on SARS-CoV-2 Transmissibility,

16 Yang Chan EY, Shahzada TS, Sham TST, et al. Narrative review of Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 2021;27:267. doi:10.3201/eid2701.202114.

non-pharmaceutical behavioural measures for the prevention of 40 Guo C, Chan SHT, Lin C, et al. Physical distancing implementation,

COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) based on the Health-EDRM framework. Br ambient temperature and Covid-19 containment: An observational

Med Bull 2020;136:46-87. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldaa030. study in the United States. Sci Total Environ 2021;789:147876.

17 Han E, Tan MMJ, Turk E, et al. Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147876.

restrictions: an analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific 41 Dreher N, Spiera Z, McAuley FM, et al. Policy Interventions, Social

and Europe. Lancet 2020;396:1525-34. doi:10.1016/S0140- Distancing, and SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in the United States: A

6736(20)32007-9. Retrospective State-level Analysis. Am J Med Sci 2021;361:575-84.

18 Wong MC, Huang J, Teoh J, Wong SH. Evaluation on different non- doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2021.01.007.

pharmaceutical interventions during COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of 42 Silva L, Figueiredo Filho D, Fernandes A. The effect of lockdown

139 countries. J Infect 2020;81:e70-1. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.044. on the COVID-19 epidemic in Brazil: evidence from an interrupted

19 Hellewell J, Abbott S, Gimma A, et al; Centre for the Mathematical time series design. Cad Saude Publica 2020;36:e00213920.

Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group. Feasibility of doi:10.1590/0102-311x00213920.

controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet 43 Krishnamachari B, Morris A, Zastrow D, Dsida A, Harper B, Santella AJ.

Glob Health 2020;8:e488-96. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7 The role of mask mandates, stay at home orders and school closure

20 Mendez-Brito A, El Bcheraoui C, Pozo-Martin F. Systematic review of in curbing the COVID-19 pandemic prior to vaccination. Am J Infect

empirical studies comparing the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical Control 2021;49:1036-42. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2021.02.002.

interventions against COVID-19. J Infect 2021;83:281-93. 44 Iwata K, Doi A, Miyakoshi C. Was school closure effective in mitigating

doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.06.018. coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Time series analysis using

21 Viner RM, Russell SJ, Croker H, et al. School closure and management Bayesian inference. Int J Infect Dis 2020;99:57-61. doi:10.1016/j.

practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid ijid.2020.07.052.

systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:397-404. 45 Rader B, White LF, Burns MR, et al. Mask-wearing and control of SARS-

doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X. CoV-2 transmission in the USA: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Digit

22 Regmi K, Lwin CM. Factors Associated with the Implementation of Health 2021;3:e148-57. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30293-4.

Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions for Reducing Coronavirus Disease 46 Pillai J, Motloba P, Motaung KSC, et al. The effect of lockdown

2019 (COVID-19): A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public regulations on SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in Gauteng Province, South

Health 2021;18:4274. doi:10.3390/ijerph18084274. Africa. S Afr Med J 2020;110:1119-23. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2020.

23 Rizvi RF, Craig KJT, Hekmat R, et al. Effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical v110i11.15222.

interventions related to social distancing on respiratory viral 47 Alimohamadi Y, Holakouie-Naieni K, Sepandi M, Taghdir M. Effect of

infectious disease outcomes: A rapid evidence-based review and Social Distancing on COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality in Iran Since

meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med 2021;9:20503121211022973. February 20 to May 13, 2020: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis.

doi:10.1177/20503121211022973. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2020;13:1695-700. doi:10.2147/RMHP.

24 Ayouni I, Maatoug J, Dhouib W, et al. Effective public health measures S265079.

to mitigate the spread of COVID-19: a systematic review. BMC Public 48 Auger KA, Shah SS, Richardson T, et al. Association Between

Health 2021;21:1015. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11111-1. Statewide School Closure and COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality in

25 Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred the US. JAMA 2020;324:859-70. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.14348.

reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: 49 Leffler CT, Ing E, Lykins JD, Hogan MC, McKeown CA, Grzybowski

the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006-12. A. Association of Country-wide Coronavirus Mortality with

doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. Demographics, Testing, Lockdowns, and Public Wearing of Masks. Am

26 Holmdahl I, Buckee C. Wrong but Useful - What Covid-19 J Trop Med Hyg 2020;103:2400-11. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-1015.

Epidemiologic Models Can and Cannot Tell Us. N Engl J Med 50 Lyu W, Wehby GL. Community Use Of Face Masks And COVID-19:

2020;383:303-5. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2016822. Evidence From A Natural Experiment Of State Mandates In The

27 Covidence Systematic Review Software. Veritas Health Innovation, US. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39:1419-25. doi:10.1377/

Melbourne Australia. www.covidence.org hlthaff.2020.00818.

28 Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing 51 Cheng Y, Ma N, Witt C, et al. Face masks effectively limit the

risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ probability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Science 2021;372:1439-

2016;355:i4919. doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919. 43. doi:10.1126/science.abg6296.

the bmj | BMJ 2021;375:e068302 | doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068302 13You can also read