Decoding mental states from brain activity in humans

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

REVIEWS

N E U R O I M AG I N G

Decoding mental states from brain

activity in humans

John-Dylan Haynes*‡§ and Geraint Rees‡§

Abstract | Recent advances in human neuroimaging have shown that it is possible to

accurately decode a person’s conscious experience based only on non-invasive measurements

of their brain activity. Such ‘brain reading’ has mostly been studied in the domain of visual

perception, where it helps reveal the way in which individual experiences are encoded in the

human brain. The same approach can also be extended to other types of mental state, such as

covert attitudes and lie detection. Such applications raise important ethical issues concerning

the privacy of personal thought.

Multivariate analysis Is it possible to tell what someone is currently think- by measuring activity from many thousands of locations

An analytical technique that ing based only on measurements of their brain activity? in the brain repeatedly, but then analysing each location

considers (or solves) multiple At first sight, the answer to this question might seem separately. This yields a measure of any differences in

decision variables. In the

easy. Many human neuroimaging studies have provided activity, comparing two or more mental states at each

present context, multivariate

analysis takes into account

strong evidence for a close link between the mind and individual sampled location. In theory, if the responses

patterns of information that the brain, so it should, at least in principle, be possible to at any brain location differ between two mental states,

might be present across decode what an individual is thinking from their brain then it should be possible to use measurements of activ-

multiple voxels measured by activity. However, this does not reveal whether such ity at that brain location to determine which one of those

neuroimaging techniques.

decoding of mental states, or ‘brain reading’1,2, can be two mental states currently reflects the thinking of the

Univariate analysis practically achieved with current neuroimaging meth- individual. In practice it is often difficult (although not

Univariate statistical analysis ods. Conventional studies leave the answers to many always impossible3) to find individual locations where

considers only single-decision important questions unclear. For example, how accu- the differences between conditions are sufficiently large

variables at any one time.

rately and efficiently can a mental state be inferred? Is to allow for efficient decoding.

Conventional brain imaging

data analyses are mass

the person’s compliance required? Is it possible to decode In contrast to the strictly location-based conventional

univariate in that they consider concealed thoughts or even unconscious mental states? analyses, recent work shows that the sensitivity of human

how responses vary at very What is the maximum temporal resolution? Is it possible neuroimaging can be dramatically increased by taking

many single voxels, but to provide a quasi-online estimate of an individual’s cur- into account the full spatial pattern of brain activity,

consider each individual voxel

separately.

rent cognitive or perceptual state? measured simultaneously at many locations2,4–17. Such

Here, we will review new and emerging approaches pattern-based or multivariate analyses have several advan-

that directly assess how well a mental state can be recon- tages over conventional univariate approaches that analyse

structed from non-invasive measurements of brain activ- only one location at a time. First, the weak information

*Max Planck Institute for ity in humans. First we will outline important differences available at each location9 can be accumulated in an effi-

Cognitive and Brain Sciences, between conventional and decoding-based approaches to cient way across many spatial locations. Second, even if

Stephanstrasse 1a, 04103

Leipzig, Germany. ‡Wellcome

human neuroimaging. Then we will review a number of two single brain regions do not individually carry infor-

Department of Imaging recent studies that have successfully used statistical pat- mation about a cognitive state, they might nonetheless

Neuroscience, Institute of tern recognition to decode a person’s current thoughts do so when jointly analysed17. Third, most conventional

Neurology, University College from their brain activity alone. In the final section we will studies employ processing steps (such as spatial smooth-

London, 12 Queen Square,

discuss the technical, conceptual and ethical challenges ing) that remove fine-grained spatial information that

London WC1N 3BG, UK.

§

Institute of Cognitive encountered in this emerging field of research. might carry information about perceptual or cognitive

Neuroscience, University states of an individual. This information is discarded in

College London, Alexandra Multivariate neuroimaging approaches conventional analyses, but can be revealed using methods

House, 17 Queen Square, Conventional neuroimaging approaches typically seek that simultaneously analyse the pattern of brain activity

London WC1N 3AR, UK.

Correspondence to J.D.H.

to determine how a particular perceptual or cognitive across multiple locations. Fourth, conventional studies

e-mail:haynes@cbs.mpg.de state is encoded in brain activity, by determining which usually probe whether the average activity across all task

doi:10.1038/nrn1931 regions of the brain are involved in a task. This is achieved trials during one condition is significantly different from

NATURE REVIEWS | NEUROSCIENCE VOLUME 7 | JULY 2006 | 523REVIEWS

are encoded in spatially distinct locations of the brain. As

Box 1 | Brain–computer interfaces and invasive recordings

long as these locations can be spatially resolved with the

Important foundations for ‘brain reading’ in humans have come from research into brain– limited resolution of fMRI, this should permit independ-

computer interfaces79–84 and invasive recordings from human patients85–87. For example, ent measurement of activity associated with these different

humans can be trained to use their brain activity to control artificial devices79,82–84. cognitive or perceptual states. Such an approach has

Typically, such brain–computer interfaces are not designed to directly decode cognitive been examined most commonly in the context of the

or perceptual states. Instead, individuals are extensively trained to intentionally control

human visual system and in the perception of objects

certain aspects of recorded brain activity. For example, participants learn by trial and

error to voluntarily control scalp-recorded electroencephalograms (EEGs), such as

and visual images.

specific EEG frequency bands79,84 or slow wave deflections of the cortical potential88.

This can be effective even for single trials of rapidly paced movements82. Such voluntarily Separable cortical modules. Some regions of the

controlled brain signals can subsequently be used to control artificial devices to allow human brain represent particular types of visually pre-

subjects to spell words79,88 or move cursors on computer displays in two dimensions84. sented information in an anatomically segregated way.

Interestingly, subjects can even learn to regulate signals recorded using functional MRI in For example, the fusiform face area (FFA) is a region

real-time89. It might be possible to achieve even better decoding when electrodes are in the human ventral visual stream that responds more

directly implanted into the brain, which is possible in monkeys (for a review, see REF. 81) strongly to faces than to any other object category19,20.

and occasionally also in human patients87. Not only motor commands but also perception Similarly, the parahippocampal place area (PPA) is

can, in principle, be decoded from the spiking activity of single neurons in humans85,86 and

an area in the parahippocampal gyrus that responds

animals39,90. However, such invasive techniques necessarily involve surgical implantation

of electrodes that is not feasible at present for use in healthy human participants.

most to images containing views of houses and visual

scenes21. As these cortical representations are separated

by several centimetres, it is possible to track whether a

the average activity across all time points during a second person is currently thinking of faces or visual scenes by

condition. Typically these studies acquire a large number measuring levels of activity in these two brain areas3.

of samples of brain activity to maximize statistical sensi- Activity in FFA measured using fMRI is higher on tri-

tivity. However, by computing the average activity, infor- als when participants imagine faces (versus buildings),

mation about the functional state of the brain at any given and higher in PPA when they imagine buildings (ver-

time point is lost. By contrast, the increased sensitivity sus faces). Human observers, given only the activity

of decoding-based approaches potentially allows even levels in FFA and PPA from each participant, were able

quasi-online estimates of a person’s perceptual or cogni- to correctly identify the category of stimulus imag-

tive state10,16. ined by the participant in 85% of the individual trials

Taken together, pattern-based techniques allow con- (FIG. 1a). So, individual introspective mental events can

siderable increases in the amount of information that can be tracked from brain activity at individual locations

be decoded about the current mental state from measure- when the underlying neural representations are well

ments of brain activity. Therefore, the shift of focus away separated. Similar spatially distinct neural representa-

from conventional location-based analysis strategies tions can also exist as part of macroscopic topographic

towards the decoding of mental states can shed light on maps in the brain, such as visual field maps in the

the most suitable methods by which information can be early visual cortex22,23 or the motor or somatosensory

extracted from brain activity. Several related fields have homunculi. Activity in separate regions of these macro-

laid important foundations for brain reading in studies scopic spatial maps can be used to infer behaviour. For

of animals and patients (BOX 1). Here, we will instead example, when participants move either their right or

focus on approaches to infer conscious and unconscious left thumb, then the difference in activity between left

perceptual and cognitive mental states from non-invasive and right primary motor cortex measured with fMRI

measurements of brain activity in humans. These tech- can be used to accurately predict the movement that

niques measure neural responses indirectly, through scalp they made24.

electrical potentials or blood-oxygenation-level-dependent

(BOLD) functional MRI (fMRI) signals. It is therefore Distributed representation patterns. Anatomically dis-

important to bear in mind that the relationship between tinct ‘modular’ processing regions in the ventral visual

the signal used for brain reading and the underlying pathway that might permit such powerful decoding

neural activity can be complex or indirect18; although, from single brain locations have been proposed for

for most practical purposes the key question is how well many different object categories, such as faces19,20,25,

brain reading can predict cognitive or perceptual states. scenes21, body parts26 and, perhaps, letters27. However,

Importantly, we will also discuss emerging technical and the number of specialized modules is necessarily lim-

Blood-oxygen-level- methodological challenges as well as the ethical implica- ited28, and the degree to which these areas are indeed

dependent (BOLD) signal tions of such research. specialized for the processing of one class of object alone

Functional MRI measures local

has been questioned4,5,29. Overlapping but distributed

changes in the proportion of

oxygenated blood in the brain; Decoding the contents of consciousness representation patterns pose a potential problem for

the BOLD signal. This A key factor determining whether the conscious and decoding perception from activity in these regions. If a

proportion changes in unconscious perceptual or cognitive states of an indi- single area responds in many different cognitive states

response to neural activity. vidual can be decoded is how well the brain activity cor- or percepts, then at the relatively low spatial resolution

Therefore, the BOLD signal, or

haemodynamic response,

responding to one particular state can be distinguished of non-invasive neuroimaging it might be difficult or

indicates the location and or separated from alternate possibilities. An ideal case of impossible to use activity in that area to individuate a

magnitude of neural activity. such separation is given when different cognitive states particular percept or thought. However, the existence

524 | JULY 2006 | VOLUME 7 www.nature.com/reviews/neuroREVIEWS

a from different categories evokes spatially extended

response patterns in the ventral occipitotemporal cortex

that partially overlap4. Each pattern consists of the spa-

tial distribution of fMRI signals from many locations

across the object-selective cortex (FIG. 1b). Perceptual

decoding can be achieved by first measuring the rep-

PPA

resentative template (or training) patterns for each

of a number of different object categories, and then

classifying subsequently acquired test measurements

fMRI signal to the category that evoked the most similar response

pattern during the training phase. The simplest way to

define the similarity between such distributed response

patterns is to compute the correlation between a test

FFA pattern and each previously acquired template pattern4.

The test pattern is assigned to the template pattern with

which it correlates best. Alternatively, more sophisti-

Time cated methods for pattern recognition, such as linear

discriminant analyses5 or support vector machines2

can be used (BOX 2). Using these powerful classification

b

methods, it has proven possible to correctly identify

which object a subject is currently viewing, even when

Even runs several alternative categories are presented2,4 (for exam-

ple, diverse objects such as faces, specific animals and

man-made objects).

r = –0.12

r= 0.45 r = 0.55

r = –0.10

Fine-grained patterns of representation. Many detailed

object features are represented at a much finer spatial

scale in the cortex than the resolution of fMRI. For

Odd runs example, neurons coding for high-level visual features

in the inferior temporal cortex are organized in colum-

nar representations that have a finer spatial scale than

Response Response the resolution of conventional human neuroimaging

to chairs to shoes

techniques32,33. Similarly, low-level visual features, such

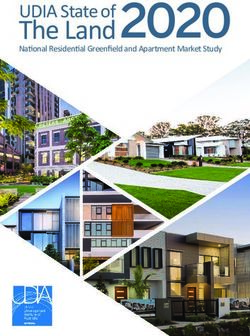

Figure 1 | Decoding visual object perception from fMRI responses. a | Decoding the as the orientation of a particular edge, are encoded

contents of visual imagery from spatially distinct signals in the fusiform face area (FFA, in the early visual cortex at a spatial scale of a few

red) and parahippocampal place area (PPA, blue). During periods of face imagery (red hundred micrometres 34. Nevertheless, recent work

arrows), signals are elevated in the FFA whereas during the imagery of buildings (blue

demonstrates that pattern-based decoding of BOLD

arrows), signals are elevated in PPA. A human observer, who was only given signals from

the FFA and PPA of each participant, was able to estimate with 85% accuracy which of contrast fMRI signals acquired at relatively low spatial

the two categories the participants were imagining. b | Decoding of object perception resolution can successfully predict the perception of

from response patterns in object-selective regions of the temporal lobe. Viewing of such low-level perceptual features (FIG. 2). For exam-

either chairs or shoes evokes a spatially extended response pattern that is slightly ple, the orientation8,9, direction of motion11 and even

different but also partially overlapping for the two categories. To assess how well the perceived colour10 of a visual stimulus presented to

perceived object can be decoded from these response patterns, the data are divided into an individual can be predicted by decoding spatially

two independent data sets (here odd and even runs). One data set is then used to extract distributed patterns of signals from local regions of

a template response to both chairs and shoes. The response patterns in the remaining the early visual cortex. These spatially distributed

data set can then be classified by assigning them to the category with the most ‘similar’ response patterns might reflect biased low-resolution

response template. Here, the similarity is measured using a Pearson correlation

sampling by fMRI of slight irregularities in such high

coefficient (r), which is higher when comparing same versus different object categories

in the two independent data sets. High correlations indicate high similarity between resolution feature maps8,9 (FIG. 2a). Strikingly, despite

corresponding spatial patterns. Panel a modified, with permission, from REF. 3 © (2000) the relatively low spatial resolution of conventional

MIT Press. Panel b reproduced, with permission, from REF. 4 © (2001) American fMRI, the decoding of image orientation is possible

Association for the Advancement of Science. with high accuracy 8 ( FIG. 2b , right) and even from

brief measurements of primary visual cortex (V1)

activity 9. Prediction accuracy can reach 80%, even

of fully independent processing modules for each per- when only a single brain volume (collected in under

cept is not necessary for accurate decoding. Instead of 2 seconds) is classified. By contrast, conventional

separately measuring activity in modular processing univariate imaging analyses cannot detect such differ-

Primary visual cortex regions that are then used to track perception of the ences in activation produced by differently oriented

Considered to be the first corresponding object categories, perceptual decoding stimuli, despite accumulating data over many hun-

visual cortical area in primates,

and receives the majority of its

can be achieved using an alternative approach that dreds of volumes9. Evidently, conventional approaches

input from the retina via the analyses spatially distributed patterns of brain activ- substantially underestimate the amount of information

lateral geniculate nucleus. ity2,4,5,15,30,31. For example, visual presentation of objects collected in a single fMRI measurement.

NATURE REVIEWS | NEUROSCIENCE VOLUME 7 | JULY 2006 | 525REVIEWS

Decoding dynamic mental states situations are not typical of patterns of thought and per-

The work discussed so far has several important limi- ception in everyday life, which are characterized by a con-

tations. For example, in all cases the mental state of an tinually changing ‘stream of consciousness’35. To decode

individual was decoded during predefined and extended cognitive states under more natural conditions it would

blocks of trials, during which the participants were either therefore be desirable to know whether the spontaneously

instructed to continuously imagine a cued stimulus, or changing dynamic stream of thought can be reconstructed

during which a stimulus or class of stimuli were continu- from brain activity alone. One promising approach to such

ously presented under tight experimental control. These a complex question has been to study a simplified model

Box 2 | Statistical pattern recognition

Spatial patterns can be analysed by a Image 1 Image 2

using the multivariate pattern

Voxel recognition approach. In panel a,

A voxel is the three- functional MRI measures brain N=9

dimensional (3D) equivalent of activity repeatedly every few 2 4

a pixel; a finite volume within seconds in a large number of small 8 3

3D space. This corresponds to volumes, or voxels, each a few 4 8

the smallest element measured 2 4

millimetres in size (left). The signal

in a 3D anatomical or 5 3

measured in each voxel reflects

functional brain image volume. 4 2

local changes in oxygenated and

8 4

Pattern vector deoxygenated haemoglobin that 4 9

A vector is a set of one or more are a consequence of neural 8 8

numerical elements. Here, a activity18. The joint activity in a

pattern vector is the set of subset (N) of these voxels (shown

values that together represent here as a 3x3 grid) constitutes a

the value of each individual

spatial pattern that can be b c

voxel in a particular spatial

expressed as a pattern vector (right).

pattern.

Different pattern vectors reflect

Orientation tuning different mental states; for example,

Many neurons in the those associated with different

mammalian early visual cortex images viewed by the subject. Each

Voxel 2

Voxel 2

evoke spikes at a greater rate pattern vector can be interpreted as

when the animal is presented a point in an N-dimensional space

with visual stimuli of a (shown here in panels b–e for only

particular orientation. The

the first two dimensions, red and

stimulus orientation that

evokes the greatest firing rate

blue indicate the two conditions).

for a particular cell is known as Each measurement of brain activity

its preferred orientation, and corresponds to a single point. A

Voxel 1 Voxel 1

the orientation tuning curve of successful classifier will learn to

a cell describes how that firing distinguish between pattern vectors d e Correct

rate changes as the orientation measured under different mental

of the stimulus is varied away states. In panel b, the classifier can

from the preferred orientation.

operate on single voxels because

the response distributions (red and

Spatial anisotropy

Voxel 2

blue Gaussians) are separable within

Voxel 2

An anisotropic property is one

individual voxels. In panel c, the two Error

where a measurement made in

one direction differs from the categories cannot be separated in

measurement made in another individual voxels because the

direction. For example, the distributions are largely

orientation tuning preferences overlapping. However, the response

of neurons in V1 change in a

distributions can be separated by

systematic but anisotropic way

taking into account the Voxel 1 Voxel 1

across the surface of the cortex.

combination of responses in both

Electroencephalogram voxels. A linear decision boundary can be used to separate these two-dimensional response distributions. Panel d is an

(EEG). The continuously example of a case where a linear decision boundary is not sufficient and a curved decision boundary is required

changing electrical signal (corresponding to a nonlinear classifier). In panel e, to test the predictive power of a classifier, data are separated into

recorded from the scalp in training and test data sets. Training data (red and blue symbols) are used to train a classifier, which is then applied to a

humans that reflects the new and independent test data set. The proportion of these independent data that are classified either correctly (open

summated postsynaptic circle, ‘correct’) or incorrectly (filled circle, ‘error’) gives a measure of classification performance. Because classification

potentials of cortical neurons

performance deteriorates dramatically if the number of voxels exceeds the number of data points, the dimensionality

in response to changing

cognitive or perceptual states.

can be reduced by using, for example, principal component analyses14, downsampling44 or voxel selection, according to

The EEG can be measured with various criteria7. An interesting strategy to avoid the bias that comes with voxel selection is to systematically search

extremely high temporal through the brain for regions where local clusters of voxels carry information12. Panels b–d modified, with permission,

resolution. from REF. 2 © (2003) Academic Press.

526 | JULY 2006 | VOLUME 7 www.nature.com/reviews/neuroREVIEWS

a presented to the two eyes, they compete for perceptual

dominance so that each image is visible in turn for a few

seconds while the other is suppressed. Because perceptual

transitions between each monocular view occur spon-

taneously without any change in physical stimulation,

neural responses associated with conscious perception

can be distinguished from those due to sensory process-

ing. This provides an opportunity to study brain reading

of conscious percepts rather than of stimuli. Signals from

the visual cortex can distinguish different dominant per-

3 mm

cepts during rivalry (for a review, see REF. 37). However,

these studies relied on averaging brain activity across

many individual measurements to improve signal qual-

b ity, and therefore cannot address the question of whether

perception can be decoded on a second-by-second basis.

Signals from the scalp electroencephalogram (EEG) can

dynamically reflect the fluctuating perceptual dominance

of each eye during binocular rivalry38, and therefore can

be used to track the time course of conscious perception.

However, the limited spatial precision of EEG leaves the

precise cortical sources of these signals unclear.

We recently demonstrated that perceptual fluctuations

during binocular rivalry can be dynamically decoded from

fMRI signals in highly specific regions of the early visual

V2v V1v

cortex10. This was achieved by training a pattern classifier

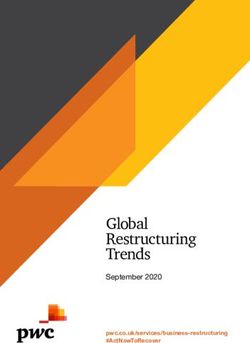

Figure 2 | Decoding perceived orientation from sampling patterns in the early

visual cortex. a | In the primary visual cortex (V1) of primates, neurons with different to distinguish between the distributed fMRI response pat-

orientation preferences are systematically mapped across the cortical surface, with terns associated with the dominance of each monocular

regions containing neurons with similar orientation tuning separated by approximately 500 percept. The classifier was then applied to an independ-

µm33 (schematically shown in the left panel, where the different colours correspond to ent test dataset to attempt dynamic prediction of any per-

different orientations106). The cortical representation of different orientation preferences ceptual fluctuations. Dynamic prediction of the currently

should therefore be too closely spaced to be resolved by functional MRI at conventional dominant percept during rivalry was achieved with high

resolutions of 1.5–3 mm (indicated by the measurement grid in the left panel). temporal precision (FIG. 3a). This also revealed important

Nonetheless, simulations9 reveal that slight irregularities in these maps cause each voxel differences between brain regions in the type of informa-

to sample a slightly different proportion of cells with different tuning properties (right tion on which successful decoding depends. Decoding

panel), leading to potential biases in the orientation preference of each voxel. b | When

from V1 is based on signals that reflect which eye was

subjects view images consisting of bars with different orientations, each orientation

causes a subtly different response pattern in the early visual cortex8,9. The map shows the dominant at the time. By contrast, decoding from the

spatial pattern of preferences for different orientations in V1 and V2 plotted on the extrastriate visual cortex is based on signals that reflect

flattened cortical surface8 (v, ventral). Although the preference of each small the dominant percept10. Similar time-resolved decoding

measurement area is small, the perceived orientation can be reliably decoded with high approaches can also reveal dissociations between the

accuracy when the full information in the entire spatial response pattern is taken into relative timing of the neural representation of informa-

account. The right panel shows the accuracy with which two different orthogonal tion and its subsequent availability for report by the

orientation stimuli can be decoded when a linear support vector classifier is trained to participant. For example, patterns of cortical activity

classify the responses to different orientations8. It is important to note that, in principle, associated with different types of picture reappear in the

such sampling bias patterns should be observable for any fine-grained cortical visual cortex several seconds before the participant ver-

microarchitecture such as object feature columns32,33 and ocular dominance columns10,37.

bally reports recall of the particular picture16. Therefore,

Although such sampling biases provide a potentially exciting bridge between

macroscopic techniques such as fMRI and single unit recording, it is important to note decoding can provide important insights into the way in

that it will not be possible to directly infer the orientation tuning width of individual which information is encoded in different brain areas and

neurons in the visual cortex from the tuning functions of these voxel ensembles. The into the dynamics of its access39.

tuning width of the voxel ensemble will depend on many parameters107 other than the Natural scenes pose an even harder challenge to the

tuning of single neurons, such as the spatial anisotropy in the distribution of cells with decoding of perception. They are both dynamic and have

different orientation preferences, the voxel size, the signal-to-noise level of the fMRI added complexities compared to the simplified and highly

measurements, and also the pattern and spatial scale of neurovascular coupling giving rise controlled stimuli used in most experiments40,41. For

to the blood-oxygen-level-development signal108,109. However, such sampling bias patterns example, natural visual scenes typically contain not just

are important because they provide a means of non-invasively revealing the presence of one but many objects that can appear, move and disappear

feature-specific information in human subjects.

independently. Under natural viewing conditions, indi-

viduals typically do not fixate a central fixation spot but

system where dynamic changes in conscious awareness freely move their eyes to scan specific paths42. This creates

are limited to a small number of possibilities. a particular problem for decoding spatially organized pat-

Binocular rivalry is a popular experimental para- terns from activity in retinotopic maps, as eye movements

digm for studying spontaneous and dynamic changes will create dynamic spatial shifts in such activity43. Natural

in conscious perception36. When dissimilar images are scenes therefore provide a much greater challenge to the

NATURE REVIEWS | NEUROSCIENCE VOLUME 7 | JULY 2006 | 527REVIEWS

a V3d V2d V1d decoding of perception. One initial approach is to study

the pattern of correlated activity between the brains of

V1v different individuals as they freely view movies, therefore

approximating viewing of a natural scene40,41. Under these

V2v dynamic conditions, signals in functionally specialized

F V3v areas of the brain seem to reflect perception of fundamen-

R tal object categories such as faces and buildings (FIG. 3b),

and even action observation.

L

Decoding unconscious or covert mental states

Decoding approaches can be successfully applied to

Behaviourally reported Conscious perception predict purely covert and subjective changes in percep-

conscious perception decoded from fMRI signals tion when sensory input is unchanged. For example, it

is possible to identify which one of two superimposed

oriented stimuli a person is currently attending to with-

L

out necessarily requiring them to explicitly report where

R

their attention is directed8. This opens up the possibil-

ity of decoding covert information in the brain that is

deliberately concealed by the individual. Indeed, in the

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 domain of lie detection, limited progress has been made

Time (s) in decoding such covert states44–46 (BOX 3). Although

hypothetical at present, the possibility of decoding con-

b cealed states that are potentially or deliberately concealed

3 1 2 3

Z-normalization

7 6 8 12 5 4 by the individual raises important ethical and privacy

2 15 9 13 10 11 16 14

1 concerns that will be discussed later.

0

–1 Unconscious mental states constitute a special case

FFA –2

n=5 of covert information that is even concealed from the

–3 individuals themselves. Various unconscious states have

6

6

6

96

6

6

6

66

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

6

36

6

18

21

27

12

15

24

30

33

36

39

42

45

48

51

54

57

60

been experimentally demonstrated, such as the percep-

Time (s)

tual representation of invisible stimuli47,48, or even uncon-

1 2 3 scious motor preparation49. Decoding-based approaches

seem to be particularly promising, both for predicting

such unconscious mental states and for characterizing

their temporal dynamics. Spatially distributed patterns of

fMRI signals in human V1 can be used to decode the ori-

entation of an oriented stimulus, even when it is rendered

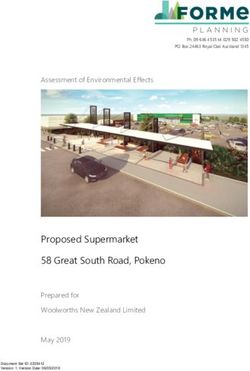

Figure 3 | Tracking dynamic mental processes. a | Decoding spontaneously fluctuating

changes in conscious visual perception10. When conflicting stimuli are presented to each

invisible to the observer by masking9 (FIG. 4a). This has

eye separately, they cannot be perceptually fused. Instead perception alternates important implications for theoretical models of human

spontaneously between each monocular image. Here, a rotating red grating was consciousness, as it shows that some types of informa-

presented to the left eye and an orthogonal rotating blue grating was presented to the tional representation in the brain have limited availability

right eye. By pressing one of two buttons, subjects indicated which of the two grating for conscious access. The ability to decode the orienta-

images they were currently seeing. Distributed fMRI response patterns recorded tion of an invisible stimulus from activity in V1 indicates

concurrently showed some regions with higher signals during perception of the red that under conditions of masking, subjects are unable

grating and other regions with higher signals during perception of the blue grating to consciously access information that is present in this

(v, ventral; d, dorsal; F, fovea). A pattern classifier was trained to identify phases of red brain area. Furthermore, such findings have important

versus blue dominance based only on these distributed brain response patterns. By

implications for characterizing the neural correlates of

applying this classifier blindly to an independent test data set (lower panel) it was

possible to decode with high accuracy which grating the subject was currently

consciousness50, by showing that feature-specific activity

consciously aware of (red and blue lines, conscious perception; black line, conscious in human V1 is insufficient for awareness. So, not only

perception decoded from pattern signals from the early visual cortex, corrected for the can decoding-based approaches address specific biologi-

haemodynamic latency). Note that this classifier decodes purely subjective changes in cal questions, but they also provide a general approach to

conscious perception despite there having been no corresponding changes in the visual study how informational representation might differ in

input, which remains constant. b | Tracking perception under quasi-natural and dynamic conscious and unconscious states.

viewing conditions using movies40. Subjects viewed a movie while their brain activity was Similar approaches could, in principle, also be

simultaneously recorded. Activity in face-selective regions of the temporal lobes (the applied to higher cortical areas or to more complex

face fusiform area, FFA) was elevated when faces were the dominant content of the visual cognitive states. For example, neural representations of

scene. The timecourse shows the average activity in FFA across several subjects. The

unconscious racial biases can be identified in groups of

peaks of this timecourse are indicated with numbers in descending order. The red

sections of the plot indicate when the signal is significantly different from baseline. The

human participants51. A decoding approach might be

bottom shows a snapshot of the visual scene for the first three peaks of FFA activity, able to predict specific biases on an individual basis.

revealing that when FFA activity was high the scenes were dominated by views of human Similarly, brain processes might contain information

faces40. Panel a modified, with permission, from REF. 10 © (2005) Elsevier Science, and that reflects an unconscious motor intention immedi-

from REF. 57 © (2004) American Association for the Advancement of Science. ately preceding a voluntary action52,53 (FIG. 4b). Although

528 | JULY 2006 | VOLUME 7 www.nature.com/reviews/neuroREVIEWS

Box 3 | Lie detection

Some progress has been made in decoding a specific type of covert mental state; the detection of deception. The

identification of lies is of immense importance, not only for everyday social interactions, but also for criminal investigations

and national security. However, even trained experts are very poor at detecting deception91. Therefore, it was proposed

almost a century ago that physiological measures of emotional reactions during deception might, in principle, be more

useful in distinguishing innocent and guilty suspects92,93. Several physiological indicators of emotional reactions have been

used for lie detection such as blood pressure92, respiration94, electrodermal activity95 and even voice stress analysis96 or

thermal images of the body97. These approaches have variable success rates and the use of ‘polygraphic’ tests, where

several physiological responses are simultaneously acquired, has been heavily debated. Criticism has been raised about the

lack of research on their reliability in real-world situations98, the adequacy of interrogation strategies99 and whether test

results can be deliberately influenced by covertly manipulating level of arousal100.

Many of these problems might be due to the reliance of polygraphy on measuring deception indirectly, by the

emotional arousal caused in the PNS. These indicators are only indirectly linked to the cognitive and emotional

processing in the brain during deception. To overcome this limitation, direct measures of brain activity (such as evoked

electroencephalogram responses101 and functional MRI44–46,102–105) have been explored as a basis for lie detection, with the

aim of directly measuring the neural mechanisms involved in deception. This could potentially allow the identification of

intentional distortions of test results, therefore increasing the sensitivity of lie detection. Several recent studies have now

investigated the feasibility of using fMRI responses to detect individual lies in individual subjects. Information in several

individual brain areas (particularly the parietal and prefrontal cortex) can be used to detect deception45,46, and this can be

improved by combining information across different regions45, especially when directly analysing patterns of distributed

spatial brain response44. These brain measures of deception might be influenced less by strategic countermeasures100, as

would be expected when directly measuring the cognitive and emotional processes involved in lying. An important

challenge for future research in this field is now to assess whether these techniques can be usefully and reliably applied to

lie detection in real-world settings.

these studies have not addressed the question of how Generalization and invariance. In almost all human

precisely and accurately an emerging intention can be decoding studies, the decoding algorithm was trained

decoded on a trial-by-trial basis, they reveal the presence for each participant individually, for a fixed set of mental

of neural information about intentions prior to their states and based on data measured in a single recording

entering awareness. This raises the intriguing question session. This is a highly simplified situation compared

of whether decoding-based approaches will in future with what would be required for practical applications. An

be able to reveal unconscious determinants of human important and unresolved question is the extent to which

behaviour. classification-based decoding strategies might generalize

over time, across subjects and to new situations. When

Technical and methodological challenges training and test sets are recorded on different days, clas-

The work reviewed above suggests that it is possible to sification does not completely break down2,8,10. If adequate

use non-invasive neuroimaging signals to decode some spatial resampling algorithms are used, then even fine-

aspects of the mental states of an individual with high grained sampling bias patterns can be partly reproduced

accuracy and reasonable temporal resolution. However, between different recording sessions. This accords with

these encouraging first steps should not obscure the predictions from computational simulations10.

fact that a ‘general brain reading device’ is still science More challenging than generalization across time

fiction54. Technical limitations of current neuroimag- is generalization across different instances of the same

ing technology restrict spatial and temporal resolution. mental state. Typically, any mental state can occur in

Caution is required when interpreting the results of many different situations, but with sometimes subtle

fMRI decoding because the neural basis of the BOLD contextual variations. Successful decoding therefore

signal is not yet fully understood. Therefore, any infor- requires accurate detection of the invariant properties of

mation that can be decoded from fMRI signals might a particular mental state, to avoid the impossible task of

not reflect the information present in the spiking activity training on the full set of possible exemplars. This, in

of neural populations18. Also, the high cost and limited turn, requires a certain flexibility in any classifica-

transportability of fMRI and magnetoencephalography tion algorithm so that it ignores irrelevant differences

scanners impose severe restrictions on potential real- between different instances of the same mental state.

world applications. Of current technologies, only the Pattern classifiers trained on a subset of exemplars from

recording of electrical or optical signals with EEG or a category can generalize to other features8, new stimula-

near infrared spectroscopy55 over the scalp might be tion conditions10 and even new exemplars2. This suggests

considered portable and reasonably affordable. But that classification can indeed be based on the invariant

Magnetoencephalography even if highly sensitive and portable recording technol- properties of an object category rather than solely on

A non-invasive technique that ogy with similar resolution to microelectrode recordings low-level features. However, the ability to identify a

allows the detection of the were available for normal human subjects, there are a unique brain pattern corresponding to an invariant

changing magnetic fields that

are associated with brain

number of crucial methodological obstacles that stand property of several exemplars will strongly depend on

activity on the timescale of in the way of a general and possibly even practical brain the grouping of different mental states as belonging

milliseconds. reading device. to one ‘type’. If a category is chosen to include a very

NATURE REVIEWS | NEUROSCIENCE VOLUME 7 | JULY 2006 | 529REVIEWS

a Target

b

–2

Visible K

Invisible W

Discrimination accuracy

0.8

Lateralized readiness

0

–2000 –1000

potential [nV]

0.7

Mask

0.6 2

0.5

4

V1 V2 V3

Time (ms)

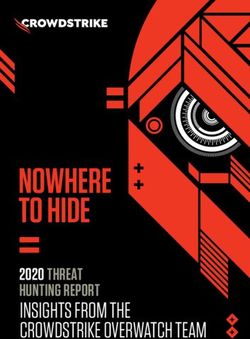

Figure 4 | Decoding unconscious processing. a | Decoding the orientation of invisible images9. Left panel, when

oriented target stimuli are alternated rapidly with a mask, subjects subjectively report that the target appears invisible

and are unable to objectively discern its orientation. Right panel, although such orientation information is inaccessible

to the subject, it is possible to decode the orientation of the invisible target from activity in their primary visual cortex.

However, target orientation cannot be decoded from V2 or V3, even though the orientation of fully visible stimuli can

be decoded with high accuracy from these areas9. This indicates the presence of feature-selective information in V1

that is not consciously accessible to the human observer. b | Predicting the onset of a ‘voluntary’ intention prior to its

subjective awareness. This study is a variant of the classical task by Benjamin Libet52. Here, subjects were asked to freely

choose a timepoint and a response hand and then to press a response key (K). They were also asked to memorize, using

a rotating clock, the time when their free decision occurred. Almost half a second prior to the subjective occurrence of

the intention (W), a deflection was visible in the electroencephalogram (known as the lateralized readiness potential;

solid line) that selectively indicated which hand was about to be freely chosen. Therefore, a brain signal can be

recorded that predicts which of several options a subject is going to freely choose even before the subjects themselves

become aware of their choice. The study does not resolve the degree to which it is possible to predict the outcome of a

subjective decision on single trials. However, the application of decoding methods to such tasks might in future render

it possible to reliably predict a subject’s choice earlier than they themselves are able to do so. Panel b modified, with

permission, from REF. 53 © (1999) Springer.

heterogeneous collection of mental states then it might are many situations where spatial matching is unlikely

not be possible to map them to a single neural pattern. to be successful. For example, the pattern of orientation

Therefore, a careful categorization of mental states is columns in V1 is strongly dependent on the early visual

required. It is also important to note that generalization experience of an individual. Such intersubject variability

is often achieved at the cost of decreased discrimination will necessarily obscure any between-subject generaliza-

of individual exemplars. Any decoding algorithm must tion of orientation-specific patterns8,9. Therefore, the

not only detect invariant properties of a mental state but extent to which cross-subject generalization is possible

also permit sufficient discrimination between individual for specific mental states remains an open and intriguing

exemplars. As a result, a successful classifier must care- question.

fully balance invariance with discriminability.

Finally, any decoding approach should ideally gener- Measuring concurrent cognitive or perceptual states. To

alize not only across different recording sessions and dif- date, it is not clear whether it is possible to independently

ferent mental states but also across different individuals. detect several simultaneously occurring mental states.

For example, the ideal brain reading device for real-world For example, the current behavioural goal of an indi-

applications such as lie detection would be one that is vidual commonly coexists with simultaneous changes in

trained once on a fixed set of representative subjects, and their current focus of attention. Decoding two or more

subsequently requires little or even no calibration for new such mental states simultaneously requires some method

individuals. Although cases of such generalization have to address superposition. A problem arises with such a

been reported7,44,56, common application of decoding decoding task because the spatial patterns indicating dif-

approaches will be strongly dependent on whether it is ferent mental states might spatially overlap. A method

possible to identify functionally matching brain regions in must be found that permits their separation if inde-

different subjects associated with the mental state in ques- pendent decoding is to be achieved. Previous research

tion. Algorithms for spatially aligning and warping indi- on ‘virtual sensors’ for mental states has demonstrated

vidual structural brain images to stereotactic templates that a degree of separation and therefore independent

are well established57. However, at the macroscopic spatial measurement of mental states can be achieved using the

scale there is not always precise spatial correspondence simplified assumption that the patterns linearly super-

between homologous functional locations in different impose7. However, it is currently unclear how to deal

individual brains, even when sophisticated alignment pro- with cases where different mental states are encoded

cedures are used58. Especially at a finer spatial scale, there in the same neuronal population. Success in measuring

530 | JULY 2006 | VOLUME 7 www.nature.com/reviews/neuroREVIEWS

concurrent perceptual or cognitive states will be closely there are any limitations on which types of mental state

linked to the further improvement of statistical pattern could be decoded. Decoding depends intimately on the

recognition algorithms. way in which different perceptual or cognitive states are

encoded in the brain. In some areas of cognition, such

Extrapolation to novel perceptual or cognitive states. as visual processing, a relatively large amount is known

Perhaps the greatest challenge to brain reading is that about the local organization of individual cortical areas.

the number of possible perceptual or cognitive states is We and others have proposed that success in decoding

infinite, whereas the number of training categories is nec- the orientation of a visual stimulus from visual cortex

essarily limited. As long as this problem remains unsolved, activity depends on the topographic cortical organiza-

brain reading will be restricted to simple cases with a fixed tion of neurons with different selectivity for that feature.

number of alternatives, for all of which training data are Topographic organization of neuronal selectivities is

available. For example, it would be useful if a decoder clearly a systematic feature of sensory and motor process-

could be trained on the brain activity evoked by a small ing, but the extent to which it might also be associated

number of sentences, but could then generalize to new with higher cognitive processes and different cortical

sentences not in the training set. To generalize from a areas remains unknown. The clustering of neurons with

sparsely sampled set of measured categories to completely similar functional roles into cortical columns might be a

new categories, some form of extrapolation is required. ubiquitous feature of brain organization60, even if it is cur-

This is possible if the underlying representational space rently unclear to what degree it is a principally necessary

can be determined, in which different mental states (or feature61. However, this ultimately remains an empirical

categories of mental state) are encoded. If the brain acti- issue, and it will be of crucial importance in future studies

vation patterns associated with particular cognitive or to identify any organizational principles for cortical areas

perceptual states are indeed arranged in some systematic associated with high-level cognitive processes such as

parametric space, this would allow brain responses to goal-directed behaviour. Such enquiries will be helped by

novel cognitive or perceptual states to be extrapolated. For decoding-based research strategies that attempt to extract

some types of mental content, this appears to be possible. the information relevant to some mental state from local

Multidimensional scaling indicates that the perceived feature maps.

similarity of relationships between objects is reflected Finally, as with any other non-invasive method it

in the corresponding similarity between distributed pat- is important to appreciate that decoding is essentially

terns of cortical responses to those objects in the ventral based on inverse inference. Even if a specific neural

occipitotemporal cortex15,30. It may therefore be possible response pattern co-occurs with a mental state under a

to classify response patterns to new object categories specific laboratory context, the mental state and pattern

according to their relative location in an abstract shape might not be necessarily or causally connected; if such a

space that is spanned by responses to measured training response pattern is found under a different context (such

categories. Extrapolation is especially required to decode as a real-world situation), this might not be indicative of

not just mental processes but also specific contents of the mental state. Such inverse inference has been criti-

cognitive or perceptual states, or even sentence-like cized in a number of domains of neuroimaging62, and

semantic propositions where there are an infinite number such cautions equally apply here.

of alternatives. For example, decoding of sentences has

so far required training on each individual example sen- Ethical considerations

tence56. Generalizing such an approach to new sentences Both structural and functional neural correlates have

will ultimately depend on the ability to measure the neural been identified for a number of mental states and traits

structure of the underlying semantic representations. that could potentially be used to reveal sensitive personal

Examining how a decoder (BOX 2) generalizes to new information without a person’s knowledge, or even against

stimuli also provides knowledge about the invariance of their will. This includes neural correlates of conscious and

the neural code in a given brain region (or at least how unconscious racial attitudes51,63,64, emotional states and

that neural activity is encoded in the fMRI signal). In this attempts at their self-regulation65,66, personality traits67,

respect such techniques complement existing indirect psychiatric diseases68,69, criminal tendencies70, drug

methods, such as repetition priming or fMRI adaptation abuse71, product preferences72 and even decisions73. The

paradigms59. The latter technique relies on a repetition- existence of these neural correlates does not in itself reveal

associated change in neural activity (usually expressed as a whether they can be used to decode the mental states or

decrease in the BOLD signal) across consecutive presenta- traits of a specific individual. This is an empirical question

tions of the same (or similar) stimuli. Such a change in sig- that has not yet been specifically addressed for real-world

nal is assumed to reflect neural adaptation or some other applications. In most cases it is unclear whether current

change in the stimulus representation, but the underlying decoding methods would be sensitive enough to reliably

mechanisms remain unclear. Importantly, the decoding reveal such personal information for individual subjects.

approach reviewed here does not make any such assump- However, it is important to realize that the recent method-

tions, and so it might provide an important complement ological advances reviewed here are likely to also enter

to the fMRI adaptation method in the future. these new areas, and lead to new applications.

Many potential applications are highly controversial,

Scope. Despite the qualified successes of the decoding and as in many fields of biomedical research the benefits

approach reviewed here, it remains unclear whether have to be weighed against potential abuse. Benefits

NATURE REVIEWS | NEUROSCIENCE VOLUME 7 | JULY 2006 | 531REVIEWS

include the large number of important potential clinical considered sufficient to justify the founding of several

applications, such as the ability to reveal cognitive commercial enterprises offering services such as neuro-

activity in fully paralysed ‘locked-in’ patients74,75, the marketing77 and the detection of covert knowledge78.

development of brain–computer interfaces for control Because little information on the reliability of these

of artificial limbs or computers (BOX 1), or even the reli- commercial services is available in peer-reviewed jour-

able detection of deception (BOX 3). But there are also nals it is difficult to assess how reliable such commercial

potentially controversial applications. It might prove services are. However, it has been noted that there is a

possible to decode covert mental states without an tendency in the media and general public to overestimate

individual’s consent or potentially even against their the conclusions that can be drawn from neuroimaging

will. While this would be entirely prohibited by current findings76. Careful and considered public engagement

ethical frameworks associated with experimental neuro- by the neuroimaging community is therefore a prereq-

science, such established frameworks do not vitiate the uisite for informed dialogue and discussion about these

need to consider such potential abuses of technology. important issues.

Whereas the usual forms of communication, such as

speech and body language, are to some extent under Conclusions and future perspectives

the voluntary control of an individual (for example, see Decoding-based approaches show great promise

BOX 3), brain reading potentially allows these channels in providing new empirical methods for predicting

to be bypassed. For example, brain reading techniques cognitive or perceptual states from brain activity.

could, in theory, be used to detect concealed or undesir- Specifically, by explicitly taking into account the

able attitudes during job interviews or to decode mental spatial pattern of responses across the cortical sur-

states in individuals suspected of criminal activity. face, such approaches seem to be capable of reveal-

Such an ability to reveal covert mental states using ing new details about the way in which cognitive

neuroimaging techniques could potentially lead to seri- and perceptual states are encoded in patterns of

ous violations of ‘mental privacy’76. Further development brain activity. Conventional univariate approaches

of this area highlights even further the importance of do not take such spatially distributed information

ethical guidelines regarding the acquisition and storage into account, and so these new methods provide a

of brain scanning results outside medical and scientific complementary approach to determining the rela-

settings. In such settings, ethical and data protection tionship between brain activity and mental states.

guidelines generally consider it essential to treat the We believe that decoding-based approaches will find

results of brain scanning experiments with similar cau- increasing application in the analysis of non-invasive

tion and privacy as with the results of any other medical neuroimaging data, in the service of understanding

test. Maintaining the privacy of brain scanning results how perceptual and cognitive states are encoded in the

is especially important, because it might be possible to human brain. However, the success of this approach

extract collateral information besides the medical, sci- will also depend on addressing important technical

entific or commercial use originally consented to by the and methodological questions, especially regarding

subject. For example, information might be contained invariance, superposition and extrapolation. The cur-

within structural or functional brain images acquired rently emerging applications that allow the practical

from an individual for a particular use that is also prediction of behaviour from neuroimaging data also

informative about completely different and unrelated raise ethical concerns. They can potentially lead to

behavioural traits. serious violations of mental privacy, and therefore

Although the ability to decode mental states as highlight even further the importance of ethical

reviewed here is still severely limited in practice, the guidelines for the acquisition and storage of human

effectiveness of brain reading has nevertheless been neuroimaging data.

1. Farah, M. J. Emerging ethical issues in neuroscience. 6. Mitchell, T. M. et al. Classifying instantaneous This work reveals the potential power of

Nature Neurosci. 5, 1123–1129 (2002). cognitive states from FMRI data. AMIA Annu. Symp. multivariate decoding to track perception quasi-

2. Cox, D. D. & Savoy, R. L. Functional magnetic resonance Proc. 465–469 (2003). online on a second-to-second basis.

imaging (fMRI) ‘brain reading’: detecting and 7. Mitchell, T. M., Hutchinson, R., Niculescu, R. S., 11. Kamitani, Y. & Tong, F. Decoding motion direction from

classifying distributed patterns of fMRI activity in Pereira, F. & Wang, X. Learning to decode cognitive activity in human visual cortex. J. Vision 5, 152a

human visual cortex. Neuroimage 19, 261–270 states from brain images. Machine Learning 57, (2005).

(2003). 145–175 (2004). 12. Kriegeskorte, N., Goebel, R. & Bandettini, P.

This study compares various classification 8. Kamitani, Y. & Tong, F. Decoding the visual and Information-based functional brain mapping.

techniques and outlines important principles of subjective contents of the human brain. Nature Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 3863–3868

decoding-based fMRI research. Neurosci. 8, 679–685 (2005). (2006).

3. O’Craven, K. M. & Kanwisher, N. Mental imagery of The first application of multivariate classification This study introduces the ‘searchlight’ approach

faces and places activates corresponding stimulus- to reveal processing of features in the primary that searches across the entire brain for specific

specific brain regions. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 12, visual cortex represented below the resolution of local patterns that encode information about a

1013–1023 (2000). fMRI. cognitive or perceptual state.

4. Haxby, J. V. et al. Distributed and overlapping 9. Haynes, J. D. & Rees, G. Predicting the orientation of 13. LaConte, S., Strother, S., Cherkassky, V., Anderson, J.

representations of faces and objects in ventral invisible stimuli from activity in primary visual cortex. & Hu, X. Support vector machines for temporal

temporal cortex. Science 293, 2425–2430 (2001). Nature Neurosci. 8, 686–691 (2005). classification of block design fMRI data. Neuroimage

One of the first studies using pattern-based This study directly compares perceptual 26, 317–329 (2005).

analysis to investigate the nature of object performance with the performance of a decoder 14. Mourao-Miranda, J., Bokde, A. L., Born, C., Hampel,

representations in the human ventral visual cortex. trained on fMRI-signals from the early visual cortex. H. & Stetter, M. Classifying brain states and

5. Carlson, T. A., Schrater, P. & He, S. Patterns of activity 10. Haynes, J. D. & Rees, G. Predicting the stream of determining the discriminating activation patterns:

in the categorical representation of objects. J. Cogn. consciousness from activity in human visual cortex. support vector machine on functional MRI data.

Neurosci. 15, 704–717 (2003). Curr. Biol. 15, 1301–1307 (2005). Neuroimage 28, 980–995 (2005).

532 | JULY 2006 | VOLUME 7 www.nature.com/reviews/neuroYou can also read