Controlled Flight Into Terrain - AVOIDING - Federal Aviation ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

November/December 2020

AVOIDING

Controlled Flight Into Terrain

Federal Aviation 7 From the Ground Up 16 Trust, But 19 Extra Eyes in

Administration How the FAA is Verify the Sky

Keeping Controlled Take AIM to Advanced Tools

November/December 2020 1

Flight Out of Terrain Avoid Terrain For CFIT AvoidanceABOUT THIS ISSUE ...

U.S. Department

of Transportation

Federal Aviation

Administration

ISSN: 1057-9648

FAA Safety Briefing

November/December 2020

Volume 59/Number 6

The November/December 2020 issue of FAA Safety

Briefing focuses on mitigating one of the leading causes

Elaine L. Chao Secretary of Transportation of general aviation accidents – controlled flight into

Steve Dickson Administrator terrain, or CFIT. Feature articles and departments explore

Ali Bahrami Associate Administrator for Aviation Safety the many CFIT-related resources and technological tools

Rick Domingo Executive Director, Flight Standards Service available to pilots, as well as numerous strategies, tips,

Susan K. Parson Editor and best practices that can help keep CFIT at bay.

Tom Hoffmann Managing Editor

James Williams Associate Editor / Photo Editor

Jennifer Caron Copy Editor / Quality Assurance Lead

Paul Cianciolo Associate Editor / Social Media

John Mitrione Art Director

Published six times a year, FAA Safety Briefing, formerly

FAA Aviation News, promotes aviation safety by discussing current

technical, regulatory, and procedural aspects affecting the safe Contact Information

operation and maintenance of aircraft. Although based on current The magazine is available on the internet at:

FAA policy and rule interpretations, all material is advisory or www.faa.gov/news/safety_briefing

informational in nature and should not be construed to have

regulatory effect. Certain details of accidents described herein may Comments or questions should be directed to the staff by:

have been altered to protect the privacy of those involved. • Emailing: SafetyBriefing@faa.gov

The FAA does not officially endorse any goods, services, materials, or • Writing: Editor, FAA Safety Briefing, Federal Aviation

products of manufacturers that may be referred to in an article. All Administration, AFS-850, 800 Independence Avenue, SW,

brands, product names, company names, trademarks, and service marks Washington, DC 20591

are the properties of their respective owners. All rights reserved. • Calling: (202) 267-1100

• Tweeting: @FAASafetyBrief

The Office of Management and Budget has approved the use

of public funds for printing FAA Safety Briefing.

Subscription Information

The Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government

Publishing Office sells FAA Safety Briefing on subscription

and mails up to four renewal notices.

For New Orders:

Subscribe via the internet at

https://bookstore.gpo.gov/products/faa-safety-briefing,

telephone (202) 512-1800 or toll-free 1-866-512-1800,

or use the self-mailer form in the center of this magazine

and send to Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government

Publishing Office, Washington, DC 20402-9371.

Subscription Problems/Change of Address:

Send your mailing label with your comments/request to

Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing

Office, Contact Center, Washington, DC 20408-9375. You can

also call (202) 512-1800 or 1-866-512-1800 and ask for

Customer Service, or fax your information to (202) 512-2104.

2 FAA Safety BriefingD E PA R T M E N T S

2 Jumpseat: an executive policy

perspective

The FAA Safety Policy Voice of Non-commercial General Aviation

3 ATIS: GA news and current events

6 Condition Inspection: a look at

specific medical conditions

26 Checklist: FAA resources and

safety reminders

27 Drone Debrief: drone safety

13

roundup

28 Nuts, Bolts, and Electrons: GA

maintenance issues

29 Angle of Attack: GA safety

strategies

30 Vertically Speaking: safety issues

for rotorcraft pilots

So Things Don’t Go Bump in the Night A voiding Terrain While Flying Night VFR

31 Flight Forum: letters from the

Safety Briefing mailbag

32 Postflight: an editor’s perspective

Inside back cover

FAA Faces: FAA employee profile

10 23

Look Up, Look Out Are We There Yet?

See and Avoid CFIT Strategies Exploring External Pressures

for VFR Pilots

From the Ground Up H ow the FAA is Keeping

7 Controlled Flight Out of Terrain

Trust, But Verify T ake AIM to Avoid Terrain

16

19 Extra Eyes in the Sky A dvanced Tools for CFIT Avoidance 19

November/December 2020 1JUMPSEAT RICK DOMINGO, FLIGHT STANDARDS SERVICE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

A “C” TO AVOID

the course being flown. Situational

awareness vanishes for a variety of

reasons. It could be navigation equip-

ment malfunctions; either known

problems that distract the pilot or

subtle issues that mislead the pilot

into misguiding the aircraft. It could

arise from limitations in human

performance (e.g., illness, fatigue,

stress) or in mechanical performance

(e.g., high density altitude, tailwinds

on approach).

Today’s aviators have the benefit of

many tools to maintain appropriate

clearance from the ground. There are

electronic warning systems, including

GPS databases and terrain aware-

ness warning systems. Technological

advances in situational awareness have

You don’t have to be in aviation at all think that CFIT accidents occur certainly reduced the number of GA

to know that “CFIT” is the acronym mostly at night, or in instrument CFIT accidents. However, the GAJSC

for “controlled flight into terrain.” The meteorological conditions (IMC). Or found that overreliance on automa-

fact that it’s a commonplace rather you might suppose that most arise tion can be a precursor to many CFIT

than just another esoteric element from the painful pattern of what acci- events. Awareness of automation lim-

in the aviation lexicon unfortunately dent reports describe as “continued itations and pilot proficiency in flying

says a lot about the prevalence of this VFR flight into IMC.” That is certainly with and without automation are key

perennial cause of aviation accidents. one cause. However, the General to safe flight.

It’s not just in GA, either; commercial Aviation Joint Steering Committee The bottom line is clear: Nothing

aviation has had its share of CFIT (GAJSC) observed that a clear major- can fully compensate for a pilot’s

accidents. The term’s notoriety also ity of the CFIT accidents in a typical failure to plan carefully in advance,

bespeaks its terrible toll: at least half of year occur in daylight, and with visual and to stay aware and alert through-

all CFIT accidents result in fatalities. conditions. out the flight. To help with that

CFIT is defined as an unintentional So again, how does CFIT happen? effort and contribute to the CFIT

collision with terrain (the ground, a How could anyone continue con- avoidance goal, the magazine team

mountain, a body of water, or an obsta- trolled flight into terrain that you can is devoting this issue of FAA Safety

cle) while an aircraft is under positive easily see and avoid? Briefing to exploring common causes

control. Most often, the pilot or crew is and various conditions in which

unaware of the looming disaster until Situational Awareness CFIT accidents occur. We’ll look at

it is too late. CFIT most commonly It seems that the most common type ways to avoid the complacency and

occurs in the approach or landing of pilot error in CFIT accidents is misplaced confidence that can con-

phase of flight. In a typical year, there the pilot’s loss of situational aware- tribute to CFIT. Finally, we’ll point

are about 40 CFIT accidents. ness — failing to know at all times to some tips and best practices to

what the aircraft’s position is, how help you stay safely in the sky until

Seeing and Not Avoiding that position relates to the altitude you make a controlled landing at

So how does such a thing happen? of the surface immediately below your intended destination.

Given this information, you might and ahead, and how both relate to

2 FAA Safety BriefingGA NEWS AND CURRENT EVENTS ATIS

AVIATION NEWS ROUNDUP

FAA Launches New Podcast Series part of the FAA’s Next Generation gram will provide grants to academia

During the summer, the FAA Air Transportation System modern- and the aviation community to help

launched an exciting new podcast ization project. prepare a more inclusive talent pool

series titled “The Air Up There.” The single award contract, valued at of aviation maintenance technicians,

Billed as a podcast for people who approximately $292 million, includes and to inspire the next generation of

are curious about the wide world of a four-year base period and 11 one- aviation maintenance professionals.

aviation, the series covers the future year options. It calls on Leidos to In fiscal year 2020, Congress appro-

of flight, drones, and ways to make perform the critical activities required priated $5 million to create and deliver

the National Airspace System safer, to deliver E-IDS, including: program a training curriculum to address the

smarter, and more efficient. Some management, systems engineering, projected shortages of aircraft pilots

recent episodes covered the new design and development, system test and aviation maintenance technical

norms for general aviation amid the and evaluation, training, production, workers in the aviation industry.

COVID-19 public health emergency, and site implementation. Eligible groups may apply for grants

as well as an inside look at how the The system is to run on a combi- from $25,000 to $500,000. Potential

FAA’s air traffic control team is keep- nation of physical resources at more applicants are encouraged to visit the

ing our skies safe. For more informa- than 400 FAA NAS facilities and on program website at bit.ly/AvGrants.

tion, including how to subscribe, go to FAA virtualized platforms using FAA

faa.gov/podcasts. cloud services. The E-IDS provides AvGas Testing and Evaluation

FAA access to efficient configuration The FAA, fuel suppliers, and aerospace

and data management tools to meet manufacturers continue to develop

the current and evolving needs of high octane, unleaded fuel formula-

NAS stakeholders. tions. The goal of these efforts is to

identify fuel formulations that provide

FAA Announces Grants for operationally safe alternatives to 100LL

Aviation Careers (low lead). The Piston Aviation Fuels

In an effort to invest in the future Initiative (PAFI) program continues to

aviation workforce, the FAA has support the efforts of fuel producers as

announced the establishment of two they bring forth alternative, unleaded

grant programs designed for avia- fuels for testing and evaluation.

tion workforce development; one for The FAA requires the fuel pro-

pilots, and one for aviation mainte- ducers to complete the following

nance personnel. “pre-screening” tests prior to a can-

The FAA’s Aircraft Pilots Workforce didate fuel formulation entering into

Development Grant Program aims to more extensive testing through the

Leidos to Develop New Display expand the pilot workforce by helping PAFI program:

System high school students receive training 1. Successful completion of a 150

Leidos, the company that provides the to become pilots, aerospace engineers, hr. engine endurance test on a

FAA’s Flight Services, will design and or unmanned aircraft systems oper- turbocharged engine using PAFI

develop a system to provide real-time ators. The program will also prepare test protocols or other procedures

access to essential weather, aeronau- teachers to train students for jobs in coordinated with the FAA;

tical, and National Airspace System the aviation industry.

The FAA’s Aviation Maintenance 2. Successful completion of an engine

(NAS) information through a com-

Technical Workforce Development detonation screening test using

mon Enterprise-Information Display

Grant Program aims to increase inter- the PAFI test protocols or other

System (E-IDS).

est and recruit students for careers procedures coordinated with the

The scalable, cloud-ready solution

in aviation maintenance. The pro- FAA; and,

will replace five legacy systems as

November/December 2020 3ATIS

3. Successful completion of a subset of

the material compatibility tests using

the PAFI test protocol or other pro-

cedures coordinated with the FAA.

Development and pre-screening

testing is taking place at both private

and public testing facilities across

the country. The FAA’s William J.

Hughes Technical Center is provid-

ing engine-testing services through

Cooperative Research and Develop-

ment Agreements (CRADA) with

the individual fuel companies. While

COVID-19 has delayed the comple- New FAA video highlights the risks of wrong direction intersection takeoffs.

tion of the pre-screening tests, the

tentative schedule is to re-start formal incidents involve general aviation the United States with limited English

PAFI testing in 2021. aircraft and pilots. A new FAA video proficiency and will focus on Spanish,

The FAA will provide additional (youtu.be/FET0oUgClOI) focusing the second most spoken language in

details to the public regarding the fuel on wrong direction intersection the U.S. The FAA seeks to remove

authorization process via the federal takeoffs describes the risks associated barriers for this segment of the U.S.

register as required per Public Law with them, and demonstrates various population interested in drones. The

115-254 (FAA Reauthorization Act strategies and tips that will help pilots FAA website will have basic drone

of 2018 HR 302, Section 565). The avoid these situations. Also check safety information for recreational

FAA also continues to support other out the FAA’s From the Flight Deck flyers with a selection of existing web

fuel applicants who have decided to video series on YouTube where you pages translated into Spanish.

pursue engine and airframe approvals can watch actual approach and taxi There are regulatory and legal

that would allow the use of their fuel footage from airports across the U.S. requirements for certificated pilots,

formulations via traditional certifica- Visit faa.gov/go/FromTheFlightDeck including remote pilot certificate

tion processes. For more information, for a map of all 30 locations. holders operating in accordance with

go to faa.gov/about/initiatives/avgas. the requirements of 14 CFR parts

Drone Safety for the Spanish- 61 or 107, to read, write, speak, and

New Video Helps Pilots Avoid Speaking Community understand English. There are no

Wrong Direction Takeoffs The FAA has launched a pilot program similar requirements for recreational

Wrong surface operations are a seri- to translate into Spanish select web drone flyers. The FAA will analyze the

ous and continuing issue at airports content for recreational unmanned results of this outreach effort and may

throughout the National Airspace aircraft systems (aka drone) operators. consider additional project phases in

System (NAS). The majority of these The program is expected to reach other languages in the future.

the nearly 25.6 million people living in

NOVEMBER

CFIT

Tips for avoiding controlled flight

into terrain accidents.

Fact Sheets DECEMBER

Aircraft Performance Monitoring

Learn how to improve your aircraft

performance predictions and better

Visit bit.ly/GAFactSheets for more information on these and other topics. adhere to operating limitations.

4 FAA Safety BriefingAEROMEDICAL ADVISORY

FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION

PRODUCTION

NOW PLAYING November/December 2020 5CONDITION INSPECTION LEO M. HATTRUP, M.D., FAA MEDICAL OFFICER

WHEN SEEING ISN’T BELIEVING

Mitigating the Hazard of Visual Illusions

A review of aircraft mishaps quickly

reveals that visual illusions and/or AS WITH SPATIAL DISORI-

poor visibility have been factors in the

majority of aircraft accidents. ENTATION, WE ARE ALL

Unless you are actively instructing SUSCEPTIBLE TO VISUAL

or preparing for a new certificate/

rating, chances are that it has been ILLUSIONS.

a while since you last thought about

the different types of visual illusions

and the impact they have on flight approach slope indicator (VASI) or

safety. With few exceptions, these precision approach path indicator

illusions make it appear that you are (PAPI). These are typically set at a

too high/too low and too close/too 3-degree descent angle, but can be

far from the runway. When pilots preparation, as well as the use of air- greater. Even without these aids, GPS

sense they are too high or too close, craft instruments and navigation tools. can help pilots maintain a safe altitude

they tend to land short and/or hard. If you are instrument qualified, until close to the airport and provide

When illusions indicate a pilot is too maintain proficiency. If not, work with guidance on an appropriate approach

low or too far, they tend to land long an instructor to gain proficiency so you angle for a straight-in approach. A

and risk overruns. can correctly use flight instruments good rule-of-thumb for descent is 300

The illusion of being either too high and instrument approach procedures feet of altitude for each nautical mile

or too low can result from a black hole to increase situational awareness from the runway.

effect, water refraction from rain on throughout a visual approach. Title 14 In summary, visual illusions may

the windscreen, haze, narrow run- Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) be unavoidable, but you can mitigate

ways, upsloping terrain or runways, section 91.103 requires pilots to review the risk. No one plans to land short, to

and bright approach lights. all available information prior to land hard, or to overrun the runway,

Conversely, conditions that make flight, but consider more than just fuel, yet we still do. Know what to expect

pilots think that they are too low runways, and weather. Evaluate the before departure, maintain proficiency,

and risk landing long are caused by potential for visual illusions based on and use the tools available to you.

wide runways, down-sloping terrain runway configuration, runway lighting,

or runways, very clear air (such as at forecast weather, and terrain (black LEARN MORE

high altitude airports), and low inten- hole potential, slopes, off-airport lights,

sity lighting systems. etc.). Forewarned is forearmed. Pre-

Several FAA handbooks, including the

Many of us have experienced false serve your night vision and consider Pilots Handbook of Aeronautical Knowl-

horizons from sloping cloud decks the use of supplemental oxygen. edge, the Helicopter Flying Handbook,

or from ground lights on slopes. It’s Another good practice that can and the Instrument Flying Handbook

important to recognize that entry into help combat visual illusions is to use describe visual illusions in detail along

fog, even when the ground is visible, a flight training device or simulator with accompanying illustrations.

can induce a sensation of pitching up. to fly to your destination under a bit.ly/FAAhandbooks

The tendency to pitch down can be number of different scenarios (e.g.,

The Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) has

catastrophic if close to the ground, a changing time of day, weather, and an excellent discussion of visual illu-

tower, or building. runways). Then use the tools avail- sions in Approach and Landing Accident

As with spatial disorientation, we able at your destination. As noted, an Reduction Task Force Briefing Note 5.3

are all susceptible to visual illusions. instrument procedure can provide (skybrary.aero/bookshelf/books/812.

Illusions are the result of how we have valuable guidance, but only if you pdf) and in an article here:

learned to perceive the world around are trained and proficient in using flightsafety.org/hf/hf_nov-dec99.pdf

us. We can compensate with pre-flight it. Many airports have either a visual

6 FAA Safety BriefingFROM THE

GROUND UP

By Tom Hoffmann

How the FAA is Keeping Controlled Flight Out of Terrain

O

n a near moonless night in November 2007, The Facts

two Civil Air Patrol pilots boarded their Cessna Let’s start by understanding what CFIT is and what it isn’t.

T182T Turbo Skylane and departed North Las According to FAA Advisory Circular (AC) 61-134, General

Vegas Airport headed southwest to Rosamond, Aviation CFIT Awareness, CFIT occurs when an airworthy

Calif. About 13 minutes into the otherwise routine flight, aircraft under the control of a qualified pilot is flown into

the aircraft impacted a near vertical rock face on the terrain (water or obstacles) due to the pilot’s inadequate

southeast side of Mount Potosi, about 1,000 feet below awareness of the impending collision. Note the qualifiers

its summit. Despite the pilots’ vast experience (over — airworthy aircraft, qualified pilot, with pilot’s lack of

53,000 hours of flight time between them), a nearly new awareness. A mechanical failure in flight or pilot’s loss of

turbocharged aircraft, and a Garmin G1000 capable of control would not be categorized as a CFIT.

displaying terrain proximity information, the crew didn’t According to 2003 AC 61-134, CFIT accidents accounted

maintain adequate terrain clearance during climb out. for about 17-percent of all GA accident fatalities at that time.

The NTSB cited rising terrain, darkness, the pilot’s loss of That rate has decreased in recent years, but not by enough.

situational awareness, and ATC failure to issue a ter- The FAA and the General Aviation Joint Steering Com-

rain-related safety alert as contributing factors. mittee (GAJSC), a joint government/industry safety effort,

This chilling account of controlled flight into terrain, have consistently ranked CFIT as a top three GA accident

or CFIT (see-fit), is all too familiar. While technological causal factor for the last two decades. A recent GAJSC

advances over the years have curtailed the rate of CFIT analysis (2011-2019) shows a total of 171 CFIT accidents (as

to some extent, it remains a persistent problem, espe- recorded at that time), placing CFIT number three on the

cially within the general aviation (GA) community. As list of accident causal factors (loss of control and powerplant

the example illustrates, there’s usually a lot to unpack with system component failures rank ahead of CFIT).

CFIT accident scenarios. Many have multiple contribut-

ing factors, but CFIT accidents typically share one com- A Team Approach

mon thread: lack of situational awareness. In this article So what causes a capable pilot in a structurally sound

you’ll learn more about what CFIT is and why it happens, airplane to have an unexpected and unwanted cumu-

along with some new strategies aimed at mitigating this lo-granitus encounter? That’s the question the GAJSC set

long-standing and often fatal problem. out to answer by chartering the CFIT Working Group

November/December 2020 7Government and industry members of the GAJSC’s CFIT working group conducted one of their offsite meetings at Honeywell’s Aerospace Global

Headquarters in Phoenix, Ariz., where they were able to tour the company’s Boeing 757 Flying Testbed aircraft.

(WG) in 2017. This team consisted of about two dozen no different than these people did.” That personal con-

government and industry aviation experts, including rep- nection further fueled her resolve to find answers.

resentatives from the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Associ-

ation (AOPA), Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA), Onsite Insight

FAA, Honeywell, Jeppesen, National Business Aircraft The WG also benefited from on-site meetings with diverse

Association (NBAA), Piper Aircraft, Society of Aviation organizations that added key insight to the team’s find-

and Flight Educators (SAFE), and Textron Aviation. ings. They visited AOPA headquarters to gather member

Over the course of two and a half years, with meetings feedback and engaged with employees at both Honey-

every six to eight weeks, the team meticulously pored over well and Jeppesen. The WG also met at the campuses of

details from 67 CFIT accidents (from 2008-2018) using Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida and

a well-tested data analysis process. Their goal: to better the University of Alaska, seeking opportunities to discuss

understand CFIT causes and to develop suitable strategies CFIT firsthand with aeronautical students. Another meet-

to prevent them. ing at NetJets’ corporate headquarters in Columbus, Ohio,

provided critical insight into the complex and demanding

The humbling part of CFIT is that world of part 135 operations.

This up-close and personal approach was especially

it can happen to anyone, anytime, helpful with one of the biggest challenges — getting inside

and in any kind of terrain. the accident pilot’s head. Identifying the kinds of stress or

distractions a pilot experienced in the lead-up to a CFIT

“It was an exceptional experience, one that was very flight is extremely difficult and sometimes impossible.

personal and incredibly humbling,” says Kieran O’Farrell, “There’s always a part of the picture that’s hard to see,” says

acting manager of the FAA’s Specialty Aircraft Examiner Kieran. “No pilot wakes up and says today’s the day I’m

Branch and government co-chair of the CFIT WG. With going to die in an airplane. There’s always something else,

24 years of Alaska floatplane flying under her belt, Kieran whether they dialed in the wrong approach, or just thought

knows a thing or two about CFIT. “I lost 17 friends in they were somewhere else. Wishful thinking never levitates

aircraft accidents,” she says, “and 15 were due to CFIT.” an airplane over that mountain.”

After WG meetings, Kieran often found herself pondering The team worked hard at piecing all available informa-

the sobering accounts of accident scenarios. “I saw myself tion on each accident together to better understand the

in a number of these accidents,” she says, “doing things range of reasons behind each tragic outcome. In one fatal

8 FAA Safety Briefingscenario, a pilot rushing to attend a funeral was likely deal-

ing with a level of grief and “get-there-itis” that contributed

Our ultimate goal is to provide

to a lack of sound decision-making. pilots with the right tools,

education, and technology to be

Team Takeaways

situationally aware of where they

After scores of meetings and detailed discussions, the CFIT

WG sorted and ranked a series of intervention strategies are both physically and mentally

based on feasibility and effectiveness. From that list the in the airplane.

team compiled a final set of recommended Safety Enhance-

ment (SE) topics that could have the greatest impact on tionally dependent.” For Kieran and the team, this kind of

addressing and mitigating root causes of CFIT accidents. scenario reinforces the need to better develop a pilot’s crit-

The SEs addressed CFIT mitigation strategies from dif- ical thinking skills and situational awareness. That’s easier

ferent perspectives, including training and education, said than done, but they are optimistic about the initiative

policy, and technology. There is also a large human factors to overhaul the WINGS Pilot Proficiency Program to help

component that addresses external pressure to continue a with the culture shift.

flight. These more insidious factors can have a huge impact The CFIT WG also stressed the need for technology

on your decisions (or indecisions) during flight. (If you’re advances to bolster real-time situational awareness of

interested in reviewing the SEs, along with a description weather and terrain. Products like electronic flight bags

of the WG’s methodology and conclusions, you can read a (EFBs) or a digital co-pilot could warn pilots of rising

report expected to appear this fall on GAJSC.org.) terrain in three miles, or of an approach not aligned with

the runway. Augmented reality goggles could reveal terrain

“SE” for Yourself cloaked in clouds or darkness. Some of these and other

This issue of FAA Safety Briefing is largely focused on the promising and potentially game-changing technologies are

subjects of those SEs, so please read on to learn what’s already being developed for GA.

being done to combat CFIT. You’ll find information on The FAA and its GAJSC partners are committed to

some powerful and precise technological solutions making finding ways to support and develop a range of CFIT miti-

their way into the GA fleet, best practices for CFIT avoid- gation strategies. “The humbling part of CFIT is that it can

ance at night and in IMC, and remedies for treating the happen to anyone, anytime, and in any kind of terrain,”

deadly affliction of “get-there-itis.” says Kieran. The accident described at the beginning of

“Our ultimate goal is to provide pilots with the right this article reinforces the point, despite there being no

tools, education, and technology to be situationally aware shortage of pilot experience or helpful technology. Kieran

of where they are both physically and mentally in the adds that “the way to avoid it is to properly make use of

airplane,” says Kieran. “That might mean reaching out to all available tools and keep your ‘SA’ at all times.” The hard

pilots and tasking industry in different ways than we have part is conveying this advice in a way that registers. The

in the past.” The SEs are a mechanism to do just that by CFIT WG Safety Enhancements are an important step

stressing key educational points and driving innovation towards not only better understanding, but also helping

towards safer and more affordable solutions. to advance a data-driven game plan that tackles CFIT

prevention in new and more meaningful ways. The future

Thinking Outside the Box of CFIT-less skies is bright.

On a broader scale, Kieran also hopes WG efforts pro-

mote a culture shift to improving a pilot’s critical thinking Tom Hoffmann is the managing editor of FAA Safety Briefing. He is a commercial

skills. One example she often touted during WG meetings pilot and holds an A&P certificate.

was the unintentional IMC escape plan. She notes that the

180-degree turn is too narrowly focused and relies more on LEARN MORE

muscle memory than a brain-based calculation. To prove the

point, Kieran phoned a flight instructor she knew during one

FAA Advisory Circular 61-134, GA CFIT Awareness

meeting who connected her with a pilot in training to ask

bit.ly/AC61-134

about IMC escape plans. Despite his effort to explain how he

would avoid such a situation in the first place, the 180-degree CFIT Video — What More Can We Do?

turn response confirmed Kieran’s suspicion. Youtu.be/JBxg6hgbAr8

“It’s not necessarily the wrong answer, but is it the same CFIT Brochure

answer if you’re in Florida or Alaska, or if you’re in icing?” bit.ly/CFITbrochure

she asks. “Maybe it’s better to climb up out of it. It’s situa-

November/December 2020 9Look Up, Look Out

See and Avoid CFIT Strategies for VFR Pilots

By Jennifer Caron

S

o why does a VFR pilot, with positive control of a Good situational awareness begins with a good preflight

fully functioning aircraft, accidentally fly it into the risk assessment. Preflight checklists are your friends — use

ground? Or into the side of a mountain, or a body of them. The PAVE, 5P, and IMSAFE checklists will help you

water, or any obstacle? make a well-reasoned go/no-go decision and determine

Despite the fact that many pilots have enhanced cockpit your personal level of risk for any flight. Take advantage

technologies on their side, these unintentional collisions, of the various flight risk assessment tools (FRATs). FRATs

defined as controlled flight into terrain (CFIT), consistently easily integrate with charting programs, cockpit displays,

ranked as a top three general aviation (GA) accident causal and weather imagery.

factor over the last two decades. Be sure to obtain and understand a preflight weather

You would think that CFIT accidents involve inexperi- briefing, and don’t forget that webcams in some locations

enced pilots flying in dark night or instrument meteorolog- can provide a real-time look at the weather along your

ical conditions (IMC). In fact, in a typical year more than route. Check again for the return flight. While en route,

75-percent of CFIT accidents occur in daylight, and more stay tuned to the outside world — heads up, eyes out — for

than half take place in visual conditions, with either VFR or unexpected weather. Keep track of conditions behind you,

instrument-rated pilots at the helm. so you know if you can simply reverse course in a pinch.

When it comes to VFR flying, a CFIT accident does not In summary, prepare for the unexpected — have a plan for

have to happen. With proper preflight preparation and what you’ll do if you encounter less than stellar conditions.

smart decision making, you can see and avoid CFIT.

Know Your Route

Plan, Prepare, Prevail Get familiar with your route before takeoff. Review Notices

The key to combating CFIT accidents starts on the ground, to Airmen (NOTAMs) and airport layouts. With a pre-

and sound preflight planning is step one. Be proactive. Know planned mental map in mind, you’ll spend less time heads-

what you’re getting into; know where you’re going; know down and more time looking out the window to see and

your capabilities; and know your resources prior to takeoff. avoid other aircraft, terrain, and obstacles.

10 FAA Safety BriefingPilot enVironment

Aircraft External

Pressures

The four elements of the PAVE

risk assessment checklist.

Identify a pre-planned diversion or suitable landing Expect the Unexpected

areas near or along your route. For example, check the Always keep in mind that no flight is routine. Learn to

charts for an alternate airport for every 25 to 30 nautical expect the unexpected. You can’t prepare for every even-

mile segment of your route. tuality, but you can take some positive steps to know in

Review VFR charts for minimum safe altitudes, obstacles, advance what you’re capable of dealing with should you

and terrain elevations to determine safe altitudes before find yourself in an adverse situation.

your flight. Give yourself some breathing room. That means Develop a set of personal minimums and tailor them to

at least a mile from airspace and 2,000 feet vertically from your current level of training, experience, currency, and

terrain that you’re trying to avoid. Use maximum elevation proficiency. VFR weather minimums are a must, but it’s

figures (MEF) to minimize chances of an inflight collision. also a good idea to have personal minimums for wind, tur-

bulence, and operating conditions that involve things like

Photo by Abigail Keenan.

high density altitude, challenging terrain, or short runways.

Never adjust personal minimums to a lower value for

a specific flight. If you’re comfortable flying in a 10 knot

crosswind, don’t push your limit to 15 knots just to satisfy

disappointed passengers who may pressure you to complete

the flight. Remember, PIC means pilot-in-command. It

does NOT mean passenger-in-command.

Managing pressure is one of the most important steps

in flight planning and CFIT avoidance because it’s the one

thing that can cause a pilot to ignore all the other risks.

The key to managing pressure is to be ready for and accept

delays. Have a backup plan B and maybe even a C to avoid

the “I must get there” mentality — that determination to

get to your destination at all costs, regardless of the risks

that lie ahead. “Get-there-itis” has caused pilots to over-

fly en route fueling options, running short of fuel before

reaching the destination. It clouds your judgement, and

tempts you to continue a VFR flight into IMC.

If you’re flying into a remote area or unfamiliar environ- Don’t Mix VFR and IMC

ment, use Google Earth for a sneak peek at where you’re Continued VFR into IMC is an ongoing threat to GA safety

going and what type of terrain and obstacles you might and is the deadliest CFIT accident precursor, proving fatal

encounter along the route. Use a flight simulation program in most cases. Never continue a VFR flight into deterio-

or device to practice flying into the area. Many feature real- rating visibility, especially if you are not instrument rated,

istic graphics that offer a good picture of your destination. current, and proficient.

November/December 2020 11Never continue a VFR flight into

Photo by Ivo Lukacovic.

deteriorating visibility, especially

if you are not instrument rated,

current, or proficient.

Be Realistic About Aircraft Performance

You need to understand how aircraft performance is

affected by density altitude, particularly in mountainous

terrain. High density altitude, combined with a shorter or

obstructed runway and aircraft at/near gross weight, has

resulted in collisions with obstacles on takeoff. Carburetor

or induction system ice can reduce climb performance with

the same result. Tailwinds on approach or takeoff can also

See and avoid dangerous assumptions. Good visual

contribute to CFIT accidents.

meteorological conditions (VMC) on departure doesn’t

mean you’ll see the same clear air at your destination. If Give Yourself Some Extra Altitude

you’re already flying in marginal VFR weather conditions

Keep a close eye out for power lines and supporting struc-

(MVFR), consider the likelihood of encountering IMC.

tures during approach and landing. Not every tower is

Mother Nature is fickle. Weather is dynamic. Visibil-

published on aeronautical charts, and many power lines are

ity can fall from unlimited to zero very quickly. Pan-

not marked or lighted. Wire strikes are common in agricul-

el-mounted or handheld NEXRAD displays can be 15 to

tural operations, but more than half are not associated with

20 minutes behind — or more. Give a wide berth to any

aerial application flying. Most occur below 200 feet above

weather you’re trying to avoid.

ground level (AGL).

Another tip for avoiding CFIT is to always remember

Give yourself some room and a little extra altitude. Even

the priorities: Aviate, Navigate, Communicate. Your first

500 feet will keep you above 90-percent of the wires. A

task is to fly the airplane, followed by navigating to avoid

lesson from the helicopter community is to fly overhead at

impacting terrain. Talk only when you’ve got the first two

a safe altitude and check the area for towers and hazards

tasks under control.

before descending to a lower altitude.

Don’t Put All Your Eggs in the Automation Basket

It Doesn’t Have to Happen

Pilots have access to more information in the cockpit than

A CFIT accident should never happen to any pilot, espe-

ever before, which probably contributes to the reduction in

cially one who is maintaining visual contact with the ter-

CFIT accidents over the last 20 years. Technology such as

rain. Plan, prepare, and make smart decisions based solely

terrain awareness/warning systems, autopilots, ADS-B, and

on the safety of your flight.

moving map displays all help to mitigate CFIT accidents.

Problems can arise if you don’t understand the technology,

Jennifer Caron is FAA Safety Briefing’s copy editor and quality assurance lead.

or if you try to use it beyond what it’s designed to do. Get She is a certified technical writer-editor in the FAA’s Flight Standards Service.

training on how they work, keep databases current, know

how to interpret the information they provide, and under-

stand how to detect equipment malfunctions. LEARN MORE

If you fly with an autopilot, bear in mind that automa-

tion dependence can lead to complacency and degraded CFIT Brochure

hand-flying competence and confidence. Strive to balance bit.ly/CFITbrochure

use of automation with hands-on flying to keep your flight

FAA Safety Enhancement Topic: CFIT/Automation Overreliance

control skills smart and effective.

bit.ly/CFITAutomation

Keep your skills sharp between flights too. Try making

simulated flights over routes you intend to fly and consider FAA Safety Enhancement Topic: Mountain Flying

a few what-if scenarios. One caution: simulator flying is not bit.ly/2pu6UP8

adequate preparation for flights to challenging locations such FAA Safety Team Video: CFIT

as mountains, obstructed short runways, and high density Youtu.be/yERx9Wx-itM

altitude environments. For those, consult a flight instructor

who knows the area well.

12 FAA Safety BriefingSo Things Don’t Go

Bump in the Night

Avoiding Terrain While Flying Night VFR

By Paul Cianciolo

“T

hey had been flying for a half-hour when John The flight instructor in this story did not survive; the

Hicks noticed that the Cessna’s airspeed had learner did. He was also my soon-to-be flight instructor,

dipped, so he mentioned it to the flight instruc- who was a friend and fellow auxiliary airman. Don’t think

tor. His teacher, sitting next to him in the cramped cockpit, this can’t happen to you. With nearly 6,000 flight hours;

pushed in the throttle, accelerating the aircraft with such an airline transport pilot certificate for airplane single-en-

gine land, multiengine land, and helicopter ratings; a

power that Hicks’ head was rocked back. It was then that

commercial pilot certificate for airplane single-engine

he lifted his eyes, peered out the windshield and saw what

sea, airplane multiengine sea, and glider ratings; a flight

was directly before them in the darkness enveloping the instructor certificate for airplane single-engine, mul-

George Washington National Forest: a mountain. tiengine, and instrument, and glider; and a first-class

At more than 120 mph, the 2,500-pound plane sliced medical certificate, the instructor still missed something

through a cluster of Appalachian hardwoods in a remote as large as a mountain while flying under visual flight

corner of northwestern Virginia. The tip of the left wing rules (VFR) on a clear night.

snapped off and the right wing struck a tree so hard that it The NTSB determined that the probable cause of this

streaked the trunk with red paint. Hicks heard metal rip, accident was “the flight instructor’s decision to conduct

glass shatter, tree limbs break, the engine scream. And yet a night training flight in mountainous terrain without

the Cessna 172, he realized, hadn’t stopped moving.” conducting or allowing the student to conduct appropriate

preflight planning and his lack of situational awareness of

This excerpt is from a 2016 narrative by John Woodrow the surrounding terrain altitude, which resulted in con-

Cox, an enterprise reporter at The Washington Post. It’s an trolled flight into terrain.”

all-too-common example of controlled flight into terrain

Off by 300 Feet

— or CFIT as we call it, which is third on the list of causal

factors of general aviation fatal accidents. Most pilots involved in CFIT accidents are not instru-

ment-rated, so we’ll start by going back to basics. Avoiding

terrain at night is easier if you use the altitudes shown on

NTSB Photo.

VFR charts as part of your preflight planning.

Review the maximum elevation figures (MEF) shown

in quadrangles bounded by ticked lines of latitude and

longitude and represented in thousands and hundreds of

feet above mean sea level (MSL). MEFs are determined by

rounding the highest known elevation in the quadrangle,

including terrain and obstructions (trees, towers, antennas,

etc.) up to the next 100 foot level. These altitudes are then

adjusted upward between 100 to 300 feet. Pilots should be

aware that while the MEF is based on the best information

available, the figures are not verified by actual field surveys.

November/December 2020 13If you need a refresher on chart symbology or the

depiction of information and/or symbols on visual chart-

CFIT is a situation that occurs when

ing products, download the FAA Aeronautical Chart Users’ a properly functioning aircraft

Guide at bit.ly/FAAChartGuide. is flown under the control of a

In the case described earlier, the flight instructor, who qualified pilot into terrain (water

was instrument rated, was conducting a demonstration of

the autopilot with an altitude hold set for 3,000 feet. The or obstacles) with inadequate

airplane impacted the side of the mountain at 3,100 feet awareness on the part of the pilot

MSL, which was approximately 300 feet below the top of of the impending collision.

the ridgeline. A review of the intended flight path on the

sectional chart would have provided a better baseline alti-

tude for the autopilot hold. and accuracy. However, you must be keenly aware of an

automation system’s capabilities and limitations. That means

Automation Bias understanding when your system is operating normally, and

Another key precursor for CFIT is a pilot’s overreliance when a failure requires you to step in and fly manually.

on automation. This can lead to pilot complacency and Many GA autopilots also lack the ability to integrate

degraded hand-flying competence and confidence. That’s aircraft position and terrain information, which was part

why this is a safety enhancement topic identified by the of the issue that led to the accident in the example. The

General Aviation Joint Steering Committee (GAJSC). aircraft that was originally scheduled for use in this training

Automation is by no means a bad thing; today’s autopilots flight was equipped with a Garmin G1000 glass cockpit

with associated navigation equipment can greatly reduce with terrain awareness capability. However, a last minute

cockpit workload and help pilots fly with greater precision change in aircraft to an old-school cockpit eliminated the

technology the instructor may have counted on using.

Transition training, also a safety enhancement topic

identified by the GAJSC, is important whenever you’re

operating an unfamiliar aircraft or avionics system. This

includes stepping from a glass cockpit with all the bells and

whistles to traditional analog dials and gauges.

Perils of Perception

Another nighttime peril is vulnerability to any of the many

kinds of illusions. Especially at night, the flight environ-

ment creates sensory conflicts that make it difficult to

determine spatial orientation. Statistics show that approx-

imately 10-percent of all GA accidents can be attributed to

spatial disorientation.

Another illusion is the black hole effect, which occurs

when you land from over water or non-lighted terrain

and runway lights are the only source of light. Without

peripheral visual cues to help, it is challenging to maintain

orientation. Any downsloping or upsloping terrain will

make the runway seem out of position. Bright runway and

approach lighting systems with few lights illuminating the

surrounding terrain may create the illusion of less distance

to the runway. If you believe this illusion, you may lower

the slope of your approach and impact terrain before

reaching the runway.

You can prevent illusions of motion and position by

maintaining a reliable visual reference to fixed points on the

ground or, when the ground is not visible, to flight instru-

In this chart quadrant example, the maximum elevation figure (MEF) circled in red

represents 4,600 feet above mean sea level (MSL). The obstacle circled in green ments. At night, your outside visual references on the ground

represents a man-made obstruction 1,844 feet MSL and 308 feet above ground may cause illusions when you see those references from

level (AGL). In extremely congested areas, the FAA typically omits the AGL values to different altitudes.

avoid confusion.

14 FAA Safety BriefingTips for Avoiding CFIT

Image courtesy of Garmin.

An NTSB safety alert about CFIT in visual conditions

explains that nighttime visual flight operations are resulting

in avoidable accidents. They give the following tips to avoid

becoming involved in a similar accident:

• CFIT accidents are best avoided through proper pre-

flight planning.

• Terrain familiarization is critical to safe visual operations

at night. Use sectional charts or other topographic refer-

ences to ensure that your altitude will safely clear terrain

and obstructions all along your route.

• In remote areas, especially in overcast or moonless condi-

tions, be aware that darkness may render visual avoidance

of high terrain nearly impossible and that the absence of

ground lights may result in loss of horizon reference.

This synthetic vision view shows the terrain in 3D with red shading where the

• When planning a nighttime VFR flight, follow IFR prac- terrain is above the current altitude of the airplane and risk of impact is imminent.

tices such as climbing on a known safe course until well The yellow shading indicates a risk of collision. The use of enhanced vision systems

is another safety enhancement topic identified by the GAJSC.

above surrounding terrain. Choose a cruising altitude

that provides terrain separation similar to IFR flights

(2,000 feet AGL in mountainous areas and 1,000 feet enhancement topic identified by the GAJSC. Every pilot

AGL in other areas). needs to prepare for the unexpected.

Accidents can happen quickly so being prepared is key.

• When receiving radar services, do not depend on

Three factors will impact your ability to survive: knowl-

air traffic controllers to warn you of terrain hazards.

edge, discipline, and planning. Don’t panic. Calm, thought-

Although controllers will try to warn pilots if they

ful action is what will help you survive the time until you’re

notice a hazardous situation, they may not always be

rescued. Most importantly, have the will to survive!

able to recognize that a particular VFR aircraft is dan-

The survivor of this accident could not access a cell

gerously close to terrain.

phone nor did he have a working handheld radio. Though

• When issued a heading along with an instruction to the emergency locator beacon (ELT) was pinging, it was

“maintain VFR,” be aware that the heading may not an older 121.5 MHz ELT. Aircraft reported hearing an

provide adequate terrain clearance. If you have any doubt automated distress tone just after sunset on a cold Saturday

about your ability to visually avoid terrain and obstacles, night, but nobody started looking until family members

advise air traffic control (ATC) immediately and take reported an overdue aircraft the next morning.

action to reach a safe altitude if necessary. It is not required by regulation, but you still might con-

• ATC radar software can provide limited prediction and sider upgrading to a 406 ELT for added safety and a quicker

warning of terrain hazards, but the warning system is response time.

configured to protect IFR flights and is normally sup-

pressed for VFR aircraft. Controllers can activate the Paul Cianciolo is an associate editor and the social media lead for FAA Safety Briefing.

warning system for VFR flights upon pilot request, but it He is a U.S. Air Force veteran, and an auxiliary airman with Civil Air Patrol.

may produce numerous false alarms for aircraft operat-

ing below the minimum instrument altitude — especially LEARN MORE

in en route center airspace.

• For improved night vision, the FAA recommends the use NTSB Safety Alert – CFIT in Visual Conditions

of supplemental oxygen for flights above 5,000 feet. ntsb.gov/safety/safety-alerts/Documents/SA_013.pdf

• If you fly at night, especially in remote or unlit areas, FAA Advisory Circular 61-134, GA CFIT Awareness

consider whether a GPS-based terrain awareness unit bit.ly/AC61-134

would improve your safety of flight.

For more about flying at night, check out our Nov/Dec 2015

N.I.G.H.T. issue of FAA Safety Briefing

Hindsight is 20/20

bit.ly/FAASB-Arc

One more fact about the accident described here is that

there was a survivor. Survival itself is another safety

November/December 2020 15By Susan K. Parson

Trust, but Verify

Take AIM to Avoid Terrain

Y

ou are an instrument-rated Limit, Route, Altitude, Frequency, Transpon-

pilot, preparing to fly an instru- der Code) format and you copy it down.

ment-equipped airplane on a day You note a couple of instructions that differ

when instrument meteorological from the IFR clearance you would get at a tow-

conditions (IMC) require the use of both. You ered airport. You know the “hold for release”

are flying from a non-towered airport, and drill, because of course you can’t launch into

weather conditions won’t allow departing IMC until air traffic control (ATC) ensures that

under VFR. No problem. You find the right you will have the required separation from

frequency or phone number and call clear- other IFR traffic. The other phrase, issued just

ance delivery. The controller rattles off a before the controller reads your route clear-

clearance in the familiar C-R-A-F-T (Clearance ance, is “upon reaching controlled airspace ....”

16 FAA Safety BriefingOh, Say Can You See?

ODPs provide obstruction

Before you do anything else, you need to verify that you

can depart the non-towered field and climb to the altitude clearance via the least onerous

where controlled airspace begins without hitting anything route from the terminal area to the

in your path. Hopefully you took that into account during appropriate en route structure.

preflight planning but avoiding a departure controlled

flight into terrain (CFIT) accident requires one last review

of your surroundings and your game plan. When I lived If Not, Use the ODP!

on the East Coast, I sometimes flew to a non-towered Here’s where having a solid command of the Aeronauti-

airport in the North Carolina foothills. The typical first fix cal Information Manual’s (AIM) section on Instrument

in an IFR clearance was to a VOR that sat atop a nearby Departure Procedures (see AIM 5-2-9) is not just handy,

mountain. It was on me, as pilot in command, to avoid but essential. Please read this entire section of the AIM

any terrain or other obstacles located along the immediate carefully, but here are a few high points.

departure path. Depending on the runway in use and climb Departure Procedures (DPs) exist to provide obstacle

gradient, a simple straight-out departure to that mountain- clearance protection information to pilots. They come in

top fix might not work out so well. So, what to do? two basic flavors. The one you might best remember is the

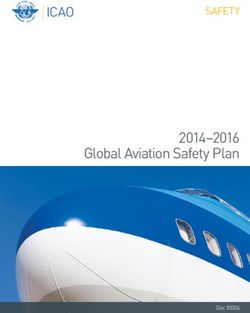

Standard Instrument Departures (SIDs) Obstacle Departure Procedures (ODPs)

Recommended [emphasis added] for

obstruction clearance; does not have to be

requested or assigned and may be flown

ATC clearance must be received prior to without ATC clearance.

ATC Clearance

flying a SID. You might wish to include plans to use the

ODP in flight plan remarks and/or advise ATC

of your intent to use the ODP when obtaining

clearance and/or IFR release.

SIDs are ATC procedures to provide obstruction

clearance and a transition from the terminal

area to the appropriate en route structure. ODPs provide obstruction clearance via the

Basic Purpose least onerous route from the terminal area to

SIDs are primarily designed for system the appropriate en route structure.

enhancement and to reduce pilot/controller

workload.

ODPs can be textural or graphic. The

procedure title for graphic ODPs includes

Depiction SIDs are always printed graphically. (OBSTACLE). An ODP developed solely for

obstacle avoidance has a “T” on IAP charts

and DP charts for that airport.

Performance All DPs assume normal aircraft performance.

Unless specified otherwise, required obstacle clearance for DPs assumes:

— Crossing the runway departure end at least 35 feet above the departure end of runway

Required elevation.

Obstacle — Climbing to 400 feet above the departure end of runway elevation before making the initial

Clearance turn.

— Maintaining a minimum climb gradient of 200 feet per nautical mile (FPNM) until reaching

minimum IFR altitude (MIA), unless a crossing restriction requires the pilot to level off.

If ATC vectors an aircraft off a previously assigned DP, ATC assumes responsibility for terrain

Vectors

and obstruction clearance (minimum 200 FPNM climb gradient is assumed).

Table 1: Key differences between Standard Instrument Departures (SIDs) and Obstacle Departure Procedures (ODPs).

November/December 2020 17DPs of a Different Sort

The AIM section on DPs also includes information on

DVAs — Diverse Vector Areas — and VCOAs (Visual

Climb Over Airport). In brief, a DVA is an area in which

ATC may provide random radar vectors during an unin-

terrupted climb from the departure runway until above the

Minimum Vectoring Altitude or Minimum IFR Altitude

(MIA). The DVA provides obstacle and terrain avoidance

in lieu of using an ODP or SID.

A VCOA procedure is a departure option for an IFR

aircraft to visually conduct climbing turns over the

airport to the published “climb-to” altitude from which

to proceed with the instrument portion of the departure.

Pilots must advise ATC of the intent to fly the VCOA

option prior to departure.

Careful planning is the key to

avoiding CFIT during IFR flight,

especially during IMC operations.

Standard Instrument Departure (SID), used at busier tow- Don’t Miss on the Missed Approach

ered airports to increase efficiency and reduce communi- The missed approach procedure (MAP) poses another

cations needs and departure delays. While SIDs might have CFIT hazard. It is one of the most challenging maneuvers

an obstacle clearance function, it is entirely possible for a a pilot can face, especially when operating alone (single

SID to exist only for ATC purposes. Either way, ATC will pilot) in IMC. Safely executing the MAP requires a precise

explicitly include a SID as part of your clearance. and disciplined transition that involves not only aeronau-

That’s not the case for Obstacle Departure Procedures tical knowledge and skill — the natural areas of focus in

(ODPs), which are published for the purpose the very name most training programs — but also a crucial psychological

expresses. There are several important things to know about shift. There is little room for error on instrument missed

ODPs, and it’s no exaggeration to say that your safety and approach procedures, and a pilot who hesitates due to defi-

your life could depend on having that knowledge. Table 1 cits in procedural knowledge, aircraft control, or mindset

(derived from the text of AIM 5-2-9) is intended to help you can quickly become a CFIT statistic. Carefully study the

see some of the key differences more clearly. MAP as part of your approach briefing, and don’t deviate

from the published altitudes and headings.

See the Big Picture

Careful planning is the key to avoiding CFIT during IFR

flight, especially during IMC operations. Before you even

get to the airplane, you need to: (1) identify terrain and

obstacles on or in the vicinity of the departure airport;

(2) determine whether an ODP is available; (3) determine

whether obstacle avoidance can be maintained visually

or if the ODP should be flown; (4) consider the effect of

degraded climb performance and the actions to take in the

event of an engine loss during the departure; and (5) check

the Terminal Procedures Publication for Takeoff Obstacle

Notes. You’ll be glad you did.

Susan K. Parson (susan.parson@faa.gov) is editor of FAA Safety Briefing and a

Special Assistant in the FAA’s Flight Standards Service. She is a general aviation

pilot and flight instructor.

18 FAA Safety BriefingYou can also read