Circuit breakers as market stability levers: A survey of research, praxis, and challenges - Imtiaz Sifat

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Received: 17 April 2018 Revised: 16 August 2018 Accepted: 10 September 2018

DOI: 10.1002/ijfe.1709

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Circuit breakers as market stability levers: A survey of

research, praxis, and challenges

Imtiaz Mohammad Sifat | Azhar Mohamad

Department of Finance, Kulliyyah of

Abstract

Economics and Management Sciences,

International Islamic University Malaysia, Circuit breaker, an automated regulatory instrument employed to deter panic,

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia temper volatility, and prevent crashes, is controversial in financial markets.

Correspondence

Proponents claim it provides a propitious time out when price levels are

Imtiaz Mohammad Sifat, Department of stressed and persuades traders to make rational trading decisions. Opponents

Finance, Kulliyyah of Economics and demur its potency, dubbing it a barrier to laissez‐faire price discovery process.

Management Sciences, International

Islamic University Malaysia, Kuala Since conceptualization in 1970s and practice from 1980s, researchers focused

Lumpur 53100, Malaysia. mostly on its ability to allay panic, interference in trading, volatility transmis-

Email: imtiaz@sifat.asia

sion, prospect of self‐fulfilling prophecy through gravitational pull towards

Funding information itself, and delayed dissemination of information. Though financial economists

Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia; are forked on circuit breakers' usefulness, they are a clear favourite among reg-

Research Management Centre of Interna-

tional Islamic University Malaysia, Grant/

ulators, who downplay the reliability of anti‐circuit breaker findings citing,

Award Number: FRGS 15‐232‐0473 inter alia, suspect methodology, and lack of statistical power. In the backdrop

of 2007–2008 Crisis and 2010 Flash Crash, the drumbeats for more regulatory

JEL Classification: D43; D47; D53

intervention in markets grew louder. Hence, it is unlikely that intervening

[Correction added on 14 November 2018, mechanism such as circuit breakers will ebb. But are circuit breakers worth

after first online publication: The

it? This paper synthesizes three decades of theoretical and empirical works,

reference Clapham, B., Gomber, P.,

Haferkorn, M., & Panz, S. (2017). underlines the limitations, issues, and methodological shortcomings

Managing Excess Volatility: Design and undermining findings, attempts to explain regulatory rationale, and provides

Effectiveness of Circuit Breakers. SSRN.

direction for future research in an increasingly complex market climate.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2910977

have been added to this version].

KEYWORDS

circuit breakers, financial markets, price limits, trading halts

1 | INTRODUCTION they arise out of market agent"s' own volition, the imposi-

tion of circuit breakers is a regulatory compulsion.

An efficient market, where participants have access to all Inspired by electrical engineers who use an automated

information, should not incur heavy overreaction or switch to protect a circuit from current overload, imposi-

underreaction leading to unreasonable volatility. Such a tion of collars on security prices as a market stability lever

market would facilitate price signals commensurate with gained popularity in the 1980s. Regulators claim its pur-

change in fundamentals. Real‐world markets, however, port is to deter overreaction, enforce control, prevent

exhibit imperfections, where irrational ex ante and ex post crashes, minimize volatility, and protect liquidity pro-

effects of news are observed. Supply and demand are mis- viders. The aftermath of Black Monday crash of October

matched, leading to order imbalance, and potentially 1987 helped propel circuit breaker praxis to limelight as

abnormal volatility. Price discovery is impeded. Although an independent regulatory tool. Attention resurfaced after

these imperfections are organic in nature, in the sense that the 2007–2008 financial crisis and again in May 2010

Int J Fin Econ. 2018;1–40. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/ijfe © 2018 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 12 SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

following a high‐frequency trading linked flash crash. 2.1 | Circuit breaker

More recently, flash crashes in cryptocurrency exchanges

A circuit breaker is an umbrella term in financial eco-

thrusted cries for circuit breakers. Case in point: the flash

nomics for a host of regulatory levers employed by secu-

crash in GDAX exchange that saw Ethereum price nose-

rity market custodians to temper volatility, prevent

dive from $317.81 to $0.10 in a matter of 45 ms. In view

crash scenarios emanating from inordinate investor over-

of these developments, concern is growing afresh among

reaction or malfunctioning algorithm, and to preserve

regulators, investors, and academics about usefulness of

market integrity. In financial markets, following a sub-

circuit breakers, magnified by potential for exacerbated

stantial price movement, circuit breakers pause or end

volatility due to growing fragmentation of financial mar-

trade earlier to allow market participants a time out to

kets. Accordingly, stakeholders in advanced financial mar-

contemplate the fundamentals, gather information, assess

kets are seeking new mechanisms to handle high

positions, and make rational decisions. Moreover, partic-

uncertainty periods to avert crashes. Meanwhile, in

ipants not yet in the market receive an opportunity to

emerging markets, circuit breakers are, in terms of param-

provide or add liquidity. Regulators hope this would for-

eters, relatively vanilla. Yet the rate of adoption since mid‐

fend panic, ease price discovery during market duress,

1990s has been staggering. In fact, the first exhaustive

and protect liquidity providers. Most common forms of

review of circuit breakers' efficacy contained few prece-

circuit breakers are price limits and trading halts.

dents—mostly North American (Harris, 1997). The next

formal survey by Kim and Yang (2004), detailing what

makes them so attractive to regulators, included 20 2.2 | Price limit

venues. Most recently, Abad and Pascual's (2013) book

chapter, focusing on an overarching theme of holding A price limit refers to the maximum stipulated magnitude

back volatility in markets via circuit breakers, reports sim- by which price may deviate from a reference price. Thus,

ilar number of venues. This paper's methodology and price limits effectively establish a band of tolerable prices

approach in organizing empirical literature benefits from for a certain period. Depending on the reference price,

Abad and Pascual's (2013) template and lists over 100 which can be last session or day's settlement price, or last

active circuit breakers. Our paper advances the discourse executed price within the same session, price limits estab-

further by underscoring the challenges in circuit breaker lish a channel of acceptable percentage (or ticks) by

research stemming from theoretical difficulties in which price may vary. Some index futures are subjected

distinguishing between multifold explanations and to a price limit designating a deviation band before cash

stresses the need for experimental studies. Also, we sug- market opens. The peak and trough of the channel are

gest avenues for extending the conventional approach called “limit up” and “limit down.” Limits can be daily

and underscore the need for incorporating alternative (interday, static) or intraday (dynamic). Some markets

and preventive mechanisms from a regulatory standpoint. are known to concurrently employ daily and intraday

Lastly, the paper's novelty includes the roles of high fre- limits. The earliest documented use of price limit was in

quency algorithmic trading nexus within circuit breaker Dojima exchange in Japan in 18th century (West, 2000).

discourse, while prognosticating potential sources of dis-

ruption from nascent technologies such as Blockchain.

2.3 | Trading halt

This paper is organized the following way. First, we pro-

vide definitions of the key, germane terms used in this field. Trading halt refers to a temporary suspension of continu-

Next, we discuss the appeal of circuit breakers to regulators, ous trading for a single security, a group of securities, an

followed by a discussion of its merits and demerits. Then, exchange, or a group of exchanges usually (but not

we detail the theoretical work done in this field, followed always;e.g., the EU) under the ambit of the same regula-

by analysis of empirical studies on key hypotheses. Then tor. It is used to redress—or in anticipation of—market

we discuss the methodological constraints plaguing disorder; for example, impending corporate announce-

research in this area that makes the findings suspect to reg- ment or news, or to remedy order imbalance. During a

ulators. Finally, we offer direction for future research. halt, open orders can be cancelled, and options exercised.

Halts may be discretionary or rule‐based (automatic). For

the former, market operator exercises its discretion to halt

2 | TERMINOLOGY trading of a security to allow investors equal opportunity

to appraise news and make informed decisions on its

Some of the basic, technical jargons used in this paper are basis—typically ahead of important or relevant news. It

defined here for convenience of non‐specialist economists can also arise out of suspicion over irregular activity

and the uninitiated. regarding the asset's price. Rule‐based halts, contrarily,SIFAT AND MOHAMAD 3

are activated upon matching predetermined parameters. Moreover, price discovery during a VI‐triggered auction

For example, a stock's trading may be automatically occurs via publishing auction prices and volumes. Lastly,

halted once a price limit is reached. These halts are tem- unlike halts which last for considerable amount of time

porary in nature and easier to anticipate compared to dis- and sometimes for the whole trading day, VIs typically

cretionary halts, which allows participants to alter their last only a few minutes. In this way, VI can be argued

trading behaviour and strategy keeping in mind prospects to be more conducive to derivatives pricing and index

of trade stoppage since. Though rule‐based halts are more calculations.

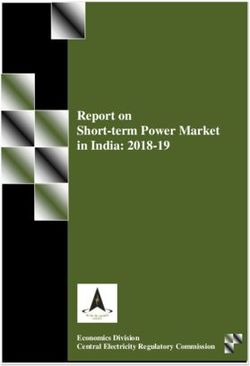

common compared with discretionary halts, and shorter Figure 1 summarizes various forms of circuit breakers

in duration, exchanges can extend them at their employed around the world.

discretion.

3 | R E GU LA T OR Y P R A X I S

2.4 | Volatility interruption

Exchanges have experimented with circuit breaker mech-

Unlike the circuit breakers popularized in North Amer- anisms since the 1970s. However, the practice was dimin-

ica, European exchanges began experimenting in the utive in scope and received little attention. Following the

1990s with a mechanism which suspends continuous Black Monday crash of 1987, the recommendation of

trading and switches to a call auction (or an extension Brady Commission's 1988 Report catapulted the practice

of call auction if interruption occurs during the auction) to prominence, leading to greater adoption by exchanges

if the next potential price falls beyond a predefined range of asset‐specific and market‐wide variants. Most

based on a reference price. This mechanism, volatility exchanges set their own thresholds for halts and/or

interruption (VI), differs from traditional circuit breakers limits. Halts can be sudden‐death (once triggered, trade

in several ways. Firstly, VIs are not enforceable market‐ stops for the day/session;e.g., Kuala Lumpur Stock

wide. Rather, they are enacted on individual securities. Exchange in the 1990s) or progressive (multi‐tiered). An

This means triggering a VI only impacts that instrument example of a progressive halt mechanism is the NYSE:

and not the whole market. Nonetheless, if the affected If S&P falls by 7%, a Level 1 circuit breaker is triggered,

security is a bellwether or industry leader, it can poten- and the entire market's trade is halted for 15 min. Upon

tially spillover, making unintended consequences. resumption, a drop of 13% triggers second halt—also for

% Based Trigger

Static

Price Based Trigger

Equity

% Based Trigger

Dynamic

Price Limits Price Based Trigger

Contract-Specific

Derivatives

Exchange-Specific

Regulatory News

Circuit Breakers

Single

Security

Exchange Triggered Order Imbalance

Trading Halts Discretion

Suddent-death

Market-wide

Progressive Tiered

Volatility Static and Dynamic Limit

Interruptions Triggers

Course: Continuous Auction

Hybrid Limits / Halts / VIs

Course: Discrete Auction

FIGURE 1 Types of circuit breakers in practice in exchanges around the world. The above image summarizes the various types of circuit

breakers currently in use by exchanges around the world. Although the choice of which mechanism to use remained quite simplistic at the

outset of regulatory experimentation, nowadays it is common to see a varieties of circuit breakers to be employed concurrently. This means

price limits and trading halts apply to the same securities, or a group of securities, or the market as a whole. The grey boxes indicate sources

and/or rationales for triggering the corresponding circuit breaker mechanism4 SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

15 min. If the market falls by 20% later, the whole market Table 1 provides a continent‐wise overview of circuit

shuts down for remainder of the day. As for security‐ breaker practices in exchanges around the world.

specific collars, London Stock exchange imposes a 5‐min

Automatic Execution Suspension Period if the acceptable

price band (5% to 10% above or below last automated book 4 | P R O S A N D CO N S O F CI R C U I T

trade—depending on the stock's market capitalization) for BREAKERS

a security is breached. These limits can be set for all stocks

indiscriminately, or be different based on size of the The integrity of a financial market relies heavily on the

company, price size, industry, or a host of discretionary integrity of pricing. Prices determine worth, dictate where

reasons. The UK's LSE practice is also known as a VI savings will be mobilized and channelized, resources will

mechanism, which is very popular in Europe. Some should be allocated, and liquidity will be sought or pro-

exchanges also outright reject orders beyond the stipulated vided. Thus, when a market fails to facilitate price discov-

price range; for example, Amman Stock Exchange, Bursa ery and signalling to the extent that supply and demand

Malaysia, Colombo Stock Exchange, and Tadawul (Saudi no longer are the key determinants, a problem emerges.

Arabia). Therefore, regulatory intervention to iron out such kinks

The practice of circuit breaks across exchanges vary in has merit. Nonetheless, whether the employed mecha-

other ways as well. For instance, exchanges such as USA's nisms have untoward consequences or fail to achieve pro-

NYSE, Canada's TSX, and Brazil's BOVESPA exempt fessed objectives—or worse, impair market quality—

markets from circuit breakers in the final hour of the warrants examination. The debate of whether circuit

day's trading. Some exchanges halt trade for the day upon breakers are merited depends on a variety of factors:

first trigger of the limit, whereas others allow multiple

trigger hits. Some exchanges allow pricing of a halted • Type of circuit breaker

security via discrete trading mechanism (call auction) • Is it a price limit or a trading halt?

upon triggering a daily (static) or intraday (dynamic) • Is it a call auction?

limit. • Is it discretionary or rule based?

Particularly interesting among the circuit breaker

mechanisms is the American experimentation with a pilot • Triggering mechanism

scheme that later crystallized into a Limit‐up‐Limit‐down • Is it induced by order?

(LULD) Breaker. The flash crash in May 2010 is • Is it induced by volume?

considered the main precursor to the LULD mechanism. • Is it induced by price?

This pilot scheme enacted a 5‐min halt in instruments

exhibiting excessive fluctuations within a 5‐min trading

window to accommodate better absorption of fundamen- As of 2018—the time of writing this paper—data col-

tals and news, with the tolerable limit set at ±10%. Though lected for Table 1 in this paper indicate 48 trading halts,

initially this applied to S&P 500 stocks, a year later the 98 price limits, and 31 VI mechanisms active among the

spectrum of subject stocks was expanded to all domestic studied 152 exchanges, with some venues opting for mul-

listings. Keeping in mind that the flash crash may have tiple, overlapping, and/or discretionary schemes. In 16

been triggered by a fat finger error, curiously, the pilot cases, continuous trading is paused, leading to an auc-

scheme detected that the LULD breaker was being tion. Meanwhile, with regard to trigger parameter, 11

prompted too often due to trading errors. Nonetheless, venues activate the circuit breaker on discretionary basis;

the pilot scheme was formalized as an official firewall meaning preset values are not publicly disclosed.

against volatility a year later in May 31, 2012, whereas Historically, the Brady Commission Report, sanc-

regulators simultaneously modified 1989's circuit breaker tioned by Reagan administration in 1988 to uncover

rules for the whole market. The LULD breaker introduced why the 1987 crash happened, was the first formal paper

a concept of “limit state,” which comes alive when to advocate market‐wide and individual circuit breakers.

qualifying stocks enter a quotation period of 15 s if the Latter proponents invoked the cooling‐off hypothesis

National Best Offer equals the lower price band (but does propounded by Ma, Rao, and Sears (1989), which argued

not exceed National Best Bid), or the National Best Bid circuit breakers could enforce price stability by curbing

equals upper price band (without crossing National Best large price swings caused by speculative overreaction,

Offer.) When a stock is in a limit state, new reference avert panic, and dissuade price manipulation. Advocates

prices or bands are calculated. The affected instrument also argue that traders' ability to modify or withdraw

emerges from limit state when the entire size of all limit standing limit orders during the halt enables informed

state quotations is executed or withdrawn. traders to manage their risk without incurring losses,TABLE 1 Overview of circuit breaker practices around the world

Exchange Symbol City Country Static Limit Dynamic Limit Remarks

Panel A: Asia

Shanghai Stock Exchange SSE Shanghai China (Mainland) ±10% (PL) None Applies to A‐Shares and mutual funds

±5% (PL) None Applies to special treatment (ST) and B‐Shares

SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

None None For new listings, closed‐end funds, shares whose

listing is resumed after suspension, and

relisted shares.

Shenzen Stock Exchange SZSE Shenzen China (Mainland) ±10% (PL) None Applies to A‐Shares and mutual funds

±5% (PL) None Applies to special treatment (ST) and B‐Shares

MWTH became effective on 01/01/16 subject to

fluctuation of the CSI 300 (SHSZ300 Index).

Suspended on 08/01/16.

Hong Kong Stock Exchange HKEX Hong Kong Hong Kong ±24 nominal spreads 9σ and ± 5% Applies to price deviations in opening session and

closing sessions respectively.

(PL) No longer applies to derivatives as of January 2017.

Tokyo Stock Exchange TSE Tokyo Japan ±¥30–¥7000000 None Absolute Yen values depending on price day's closing

price or special quote

(PL) (TH) TSE allows two 15‐min market‐wide circuit breakers

for extreme price moves at its discretion

Osaka Securities Exchange/ OSE Osaka Japan 8–21% None Normal: 8%/13% for stock exchange futures/options

JASDAQ (12%/17% and 16%/21% for successive expansions).

(PL) (TH) OSE/JASDAQ has a 2000‐point absolute limit.

Chi‐X Japan CHIJ Tokyo Japan ±10% (PL) None Single‐stock circuit breaker.

Mongolian Stock Exchange MSE Ulan Bator Mongolia Discretionary (TH) Discretionary

Korea Exchange KRX Busan Korea ±15% (Equities) (PL) None

10–20–30% (PL) None Single Stock Futures

Taiwan Stock Exchange TSE Taipei Taiwan (ROC) ±10% (PL) None Applies to domestic and foreign stocks, REITs, ETFs,

Futures. Reference price is based on day's opening auction

±5% (PL) None Corporate bonds without warrants. Those with warrants

are subject to a limit price of opening price * (1 ± 5%)

+ (limit‐up price

of underlying security for that day–auction reference price

at opening for underlying security) * Exercise ratio

Cambodia Securities Exchange CSX Phnom Cambodia ±5% (PL) None

Penh

Indonesia Stock Exchange IDX Jakarta Indonesia ±10%, ±15%. ±20% (TH) None Market‐wise trading halt. Level 1 incurs 30‐min halt.

(Continues)

56

TABLE 1 (Continued)

Exchange Symbol City Country Static Limit Dynamic Limit Remarks

Panel A: Asia

Level 3 causes blanket suspension until approval is

receives from regulator.

±20%, ±25%, ±35% (PL) None Asset‐specific price limits in place via automated

order rejection.

Lao Securities Exchange LSX Vientiane Laos ±10% (PL) None

Bursa Malaysia MYX Kuala Malaysia ±30% (PL, TH) ±8% FBMKLCI is subject to 1 hour of trading halt if down

Lumpur by 10%. 20% fall thereafter is a day‐long halt.

±30% applies to stocks priced above MYR 1.00. For

stocks priced MYR 0.99 or less, limit is MYR 0.30

(in nominal terms).

Malaysia Derivatives Exchange BMDB Kuala Malaysia ±10% (PL) None Not applicable to spot month trades of futures.

Lumpur

Myanmar Securities Exchange MSEC Yangon Myanmar Hierarchical (PL) None Based on absolute MMK value.

Centre

Philippine Stock Exchange PSE Manila Philippines 50% up, 40% down ±10%

Singapore Stock Exchange SGX Singapore Singapore (PL) ±10% Circuit breaker on single security at and above

$0.50: ±10% from the reference price.

5‐min cooling‐off period follows during which trading

can only take place within the ±10% price band.

Stock Exchange of Thailand SET Bangkok Thailand ±10–20% (TH) None 30 and 60‐min market‐wide trading halts upon first

and second trigger.

±30% SSPL (PL) ±1 Price Main board stocks. ±60% fluctuation is tolerated for

foreign stocks.

Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange HOSE Ho Chi Vietnam ±7% (PL) None ±20% on first‐day of IPO listing.

Minh

Hanoi Stock Exchange HNX Hanoi Vietnam ±10% (PL) None ±30% on first day of IPO listing.

Afghanistan Stock Exchange AFX Kabul Afghanistan None None

Chittagong Stock Exchange CSE Chittagong Bangladesh ±3.75–10% (PL) None Limits vary according to price size and can

be applied on nominal values.

Dhaka Stock Exchange DSE Dhaka Bangladesh ±3.75–10% (PL) None Limits vary according to price size and can

be applied on nominal values.

Royal Securities Exchange RSEBL Thimphu Bhutan ±15% (PL) None

of Bhutan

(Continues)

SIFAT AND MOHAMADTABLE 1 (Continued)

Exchange Symbol City Country Static Limit Dynamic Limit Remarks

Panel A: Asia

Bombay Stock Exchange BSE Mumbai India ±10%, ±15%, ±20% (PL) None Dummy price limits are available for derivatives

SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

National Stock Exchange of NSE Mumbai India ±2%, ±5%, ±10% None Market‐wide circuit breaker of 10%, 15%, and 20%.

India Stock‐wide circuit breakers apply only to scrips

with no derivative products.

(PL, TH) ±20% limits apply to debentures and preference shares.

Maldives Stock Exchange MSE Male Maldives None (TH) None Discretionary halt provisions exist

Nepal Stock Exchange NEPSE Kathmandu Nepal 3%, 4%, 5% (TH) None Market‐wide circuit breaker. Applied for the first time

on March 28. Still room for changes.

Pakistan PSX Karachi Pakistan ±5%, 7.5%, 10% (PL) None

Colombo Stock Exchange XCOL Colombo Sri Lanka ±10% (PL, TH) None ±5% market‐wide circuit breaker.

Armenian Stock Exchange NASDAQ. Yerevan Armenia None None

AM

Baku Stock Exchange BFB Baku Azerbajan None None

Bahrain Stock Exchange BFEX Manama Bahrain ±10% (PL) None No circuit breaker for mutual funds or bonds.

Cyprus Stock Exchange CSE Nicosia Cyprus ±10% (PL) ±3%

Georgian Stock Exchange SSB Tblisi Georgia None None

Tehran Stock Exchange TSE Tehran Iran ±5% (PL) None

Iran Fara Bourse IFB Tehran Iran ±5% (PL) None

Iraq Stock Exchange ISX Baghdad Iraq ±20% (PL) None

Tel Aviv Stock Exchange TASE Tel Aviv Israel ±8%, ±12% None If TA‐25 moves by ±8% in relation to bsic index,

market‐wide halt for 45 min occurs.

(PL, TH) If TA‐25 moves by ±12% in relation to bsic index,

suspension lasts till next business day.

±35% (PL) For equities and in convertible bonds during opening phase.

Amman Stock Exchange ASE Amman Jordan ±5%, ±7%, ±10% (PL, None ±5% for 2nd/3rd markets; ±7.5% for 1st market,

TH) and ± 10% for OTC market.

Boursa Kuwait BK Safat Kuwait ±20% (PL) None Exchange is in the process of employing dynamic limits

in nominal terms (KWD or fils).

Beirut Stock Exchange BSE Beirut Lebanon ±10% (PL) None ±15% for Solidere shares

Muscat Securities Market MSM Muscat Oman ±10% (PL) None

Palestine Securities Exchange PSE Nablus Palestine ±5% (PL) None

7

(Continues)8

TABLE 1 (Continued)

Exchange Symbol City Country Static Limit Dynamic Limit Remarks

Panel A: Asia

Doha Securities Market DSM Doha Qatar ±10% (PL, TH) None Applies both to stocks and index.

Tadawul XSAU Riyadh Saudi Arabia ±10% (PL) None Settlement is expected to be T + 2 from late‐2017.

Damascus Securities Exchange DSE Damascus Syria ±5% (PL) None Previously ±2%

Borsa Istanbul ISE Istanbul Turkey ±20% (PL) None Applies to equities and ETFs. ±50% for preemptive rights.

No limit for warrants.

±10% (TH) None Market‐wide.

For derivatives market (VIOP), daily price limit is defined

in contract specifications

Abu Dhabi Securities Market XADS Abu Dhabi UAE 15% up, 10% down (PL) None When a stock falls 5%, the stock goes to auction for 5 mins,

and if it falls 9% it goes to auction for 10 min.

Dubai Financial Market DFM Dubai UAE 15% up, 10% down (PL) None ±5% for inactive stocks

NASDAQ Dubai DIFX Dubai UAE Variable (PL) None ±50% for AED 0 to 0.1; ±20% for AED ±0.1 to 0.25; ±15%

for AED 0.25 to 0.5; ±10% for > AED 0.5.

Kazakhstan Stock Exchange KASE Almaty Kazakhstan ±15% (PL) None Limits for futures vary between ±30% to ±50%.

Kyrgyz Stock Exchange KSE Bishkek Kyrgyzstan None None

Tashkent Stock Exchange TSE Tashkent Uzbekistan None None

Panel B: Australia (Continent)

Australian Securities Exchange ASX Sydney Australia None None Provisions for halt on discretionary basis or at the request

of a company or anticipating announcement.

Chi‐X Australia CHIA Sydney Australia None None

South Pacific Stock Exchange SPSE Suva Fiji None None

New Zealand Stock Exchange NZSX Wellington New Zealand Variable (PL, TH) None Asymmetric asset‐specific limits.

Port Moresby Stock Exchange Port Moresby Papua New Guinea None None

Panel C: Africa

Algiers Stock Exchange SGBV Algiers Algeria None None

Botswana Stock Exchange BSE Gaborone Botswana None None

Bourse Regionale des Valeurs Mobilieres BVRM Abidjan Cote D'Ivoire ±15% (PL) None Overnight

The Egyptian Stock Exchange EGX Egyptian Exchange Egypt ±10% (VI, TH) ±5% 30‐min suspension for dynamic limit triggers

(Continues)

SIFAT AND MOHAMADTABLE 1 (Continued)

Panel C: Africa

±5%, ±10% (TH) None Temporary market‐wide trading halt if EGX100

moves by ±5%. Day‐long suspension if ±10%.

Ghana Stock Exchange GSE Accra Ghana ±7.5% (PL) None

SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

Nairobi Securities Exchange NSE Nairobi Kenya ±10% (PL) None Overnight

Libyan Stock Market LSM Tripoli Libya None None

Malawi Stock Exchange MSE Blantyre Malawi None None

Stock Exchange of Mauritius SEM Port Louis Mauritius ±8% (PL) None

Casablanca Stock Exchange Casa SE Casablanca Morocco ±10% (VI, TH) ±6% Dynamic hit triggers 5‐min suspension. Upon

resumption another 4% move in same direction

trade is halted.

Bolsa de Valores de Mozambique BVM Maputo Mozambique ±15% (PL) None

Namibian Stock Exchange NSX Windhoek Namibia None None

Nigerian Stock Exchange NSE Lagos Nigeria ±10% (PL) None Compounded

Abuja Securities and Commodities Exchange ASCE Abuja Nigeria None None

Rwanda Stock Exchange RSE Kigali Rwanda None None

Seychelles Securities Exchange (Trop‐X) SSE Victoria Seychelles None None

Johannesburg Stock Exchange JSE Johannesburg South Africa None None

Khartoum Stock Exchange KSE Khartoum Sudan None None

Swaziland SSX Mbabane Swaziland None None

Dar‐es‐Salam Stock Exchange DSE Dar es Salaam Tanzania None None

Bourse des Caleurs Mobilieres de Tunis BVMT Tunis Tunisia ±6% (PL) None

Uganda Stock Exchange USE Kampala Uganda None None

Lusaka Stock Exchange LuSE Lusaka Zambia ±10% (PL) None Overnight

West African Stock Exchange BRVM Abidjan Cote D'Ivoire ±7.5% (PL) None

Zimbabwe Stock Exchange ZSE Harare Zimbabwe Undisclosed None Implemented from Summer 2016 as part of

migration to automated trading.

Panel C: North America

Bahamas Securities Exchange BISX Nassau Bahamas ±10% (PL) None

(Continues)

910

TABLE 1 (Continued)

Panel C: North America

Barbados Stock Exchange BSE Bridgetown Barbados ±15% (TH) None Market‐wide temporary suspension; currently

under review

±30% (PL) ±10% Stock‐specific. Order rejection in place for variations

beyond 10%.

Bermuda Stock Exchange BSX Hamilton Bermuda None (PL) None

Toronto Stock Exchange TSX Toronto Canada 7%, 13%, 20% ±10% Market‐wide trading halts occur if S&P 500 or TSX drops

by 7% (Level 1), 13% (Level 2), and 20% (Level 3)

(VI, TH) Breach of dynamic limit within 5‐min leads to

a 5‐min halt.

Montreal Exchange MX Montreal Canada Discretionary None Set on a monthly basis after collaborating with

(TH) clearing corporation

Bolsa de Valores de El Salvador BVES San Salvador El Salvador None None

Bolsa Nacional de Valores BNV Guatemala City Guatemala None None

Haitian Stock Exchange HSE Port‐au‐Prince Haiti None None

Bolsa Centroamericana de Valores BCV Tegucialpa Honduras None None

Jamaica Stock Exchange JSE Kingston Jamaica ±15% (TH) None Market‐wide temporary suspension

±30% (PL) None Stock‐specific

Bolsa Mexicana de Valores BMV Mexico City Mexico ±15% (TH) None Halting is discretionary.

Trinidad and Tobago Stock Exchange TTSE Port of Spain Trinidad and Tobago ±15% (TH) None Market‐wide temporary suspension

±30% (PL) ±10% Stock‐specific. Order rejection in place

for variations beyond 10%.

NASDAQ NASDAQ New York City USA 7%, 13%, 20% None Market‐wide trading halts occur if S&P 500 drops

by 7% (Level 1), 13% (Level 2),

and 20% (Level 3)

(TH) Level 1 and Level 2 are temporary halts, whereas

Level 3 results in suspension for the day's

remaining hours.

Level 1 and Level 2 halts are for 15 min if they

occur before 3.25 PM.

LULD Breaker Price Band = (Reference Price) +/− ((Reference Price) x

(Percentage Parameter))

Up/Down Bands come from multiplying Reference Price

by % Parameter and then adding or subtracting that

value from RP.

The resulting values are then rounded to the nearest penny.

SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

(Continues)TABLE 1 (Continued)

Panel C: North America

New York Stock Exchange NYSE New York City USA 7%, 13%, 20% None Market‐wide trading halts occur if S&P 500 drops by

7% (Level 1), 13% (Level 2), and 20% (Level 3)

(TH) Level 1 and Level 2 are temporary halts, whereas Level 3

SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

results in suspension for the day's remaining hours.

Level 1 and Level 2 halts are for 15 min if they occur

before 3.25 PM.

LULD Breaker Price Band = (Reference Price) +/− ((Reference Price) x

(Percentage Parameter))

Up/Down Bands come from multiplying Reference Price by %

Parameter and then adding or subtracting that value from RP.

The resulting values are then rounded to the nearest penny.

Level 1 and Level 2 halts are for 15 min if they occur before 3.25 PM.

Panel D: South America

Buenos Aires Stock Exchange BCBA Buenos Aires Argentina ±10%, ±15% (TH) None Market‐wide trading halts.

Bolsa Boliviana de Valores BVB La Paz Bolivia Undisclosed (TH) None

BM&F Bovespa BOVESPA Sao Paulo Brazil Undisclosed (VI, TH) Undisclosed Market‐wide trading halt occurs at 3 levels:

10%, 15%, and 20%. Level 1 and 2 result in

30 and 60‐min halts.

Level 3 shuts down the market for the rest of the

day. Dynamic volatility interruptions last 2 min.

Rio de Janeiro Stock Exchange BVRJ Rio de Janeiro Brazil Undisclosed (VI, TH) Undisclosed Market‐wide trading halt occurs at 3 levels: 10%, 15%,

and 20%. Level 1 and 2 result in 30 and 60‐min halts.

Level 3 shuts down the market for the rest of the day.

Dynamic volatility interruptions last 2 min.

Bolsa Comercio de Santiago SSE Santiago Chile Discretionary (TH) None

Bolsa de Valores de Colombia BVC Bogota Colombia ±10%; ±15% (TH) None Market‐wide trading halt at ±10% for 30 min. Second

level leads to day‐long suspension

±6.5%, ±7.5%, ±10% (TH) None 2.5‐min stock‐specific trading halts.

Bolsa de Valores de Lima XLIM Lima Peru ±7%, ±10% (TH) None Market‐wide trading halts based on BVL index.

±15% (PL, VI) None Single Stock circuit breaker for equities. ELEX trading

platform rejects orders if price volatility is severe.

(Continues)

1112

TABLE 1 (Continued)

Panel D: South America

Bolsa de Valores de Montevideo BVL Montevideo Uruguay None None

Bolsa de Valores de Caracas BVC Caracas Venezuela None None

Panel E: Europe

Tirana Stock Exchange XTIR Tirana Albania

Wiener Borse XWBO Vienna Austria Undisclosed (VI) Undisclosed Volatility interruption is triggered upon breaching an

undisclosed price band (assumed 2–4%).

Call auction ensues, lasting 2–5 min.

Belarusian Currency and Stock BCSE Minsk Belarus

Exchange

Euronext Brussels XBRU Brussels Belgium ±10% (VI, TH) ±5% ±6% static and ± 3% dynamic limit for BEL20 stocks.

Sarajevo Stock Exchange XSSE Sarajevo Bosnia & ±20%; ±50% (PL) ±3% ST1 segment, comprising 30 most liquid shares, is

Herzegovina subject to ±20% static limit

ST2 segment, comprising all shares sans ST1, is subject

to ±50% static limit

Both ST1 and ST2 are subject to ±3% dynamic limit,

which triggers a 15‐min volatility interruption

Bulgarian Stock Exchange XBUL Sofia Bulgaria ±10% (PL) ±5% Premium equities as designated by BSE, non‐leveraged

ETFs, and special purpose vehicles.

±20% (PL) ±10% Standard equities as designated by BSE, compensatory

instruments, and leveraged ETFs.

±5% (PL) ±2.5% Bonds

±30% (PL) ±15% BaSE market and shares traded at scheduled auctions.

Dynamic limit does not apply to the latter.

Zagreb Stock Exchange XZAG Zagreb Croatia ±10% (PL) None Applies to shares which trade on 75% trading days with

average daily turnover > HRK 100,000.

±15% (PL) None Applies to shares which trade on 50% trading days with

average daily turnover > HRK 50,000.

±25% (PL) None Remaining shares.

Prague Stock Exchange XPRA Prague Czech Republic Variable (VI) Variable If the midpoint of the allowable spread deviates by more

than 20% from the midpoint at the start of the open

phase and does not

Return to within spreadTABLE 1 (Continued)

Panel E: Europe

The permissible spread is extended by 10% post‐resumption,

with provision for upto ±50%.

SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

Copenhagen Stock Exchange XCSE Coepnhagen Denmark ±15% (PL, VI) ±5% For OMXC20 stocks, static and dynamic limits are

±10% and ± 3%

Static and dynamic limits lead to 3 and 1‐min suspensions,

followed by discrete call auctions.

Tallinn Stock Exchange XTAL Tallinn Estonia ±15% (PL) None

Helsinki Stock Exchange XHEL Helsinki Finland ±15% (PL, VI) ±5% For OMXC20 stocks, static and dynamic limits are

±10% and ± 3%

Static and dynamic limits lead to 3 and 1‐min suspensions,

followed by discrete call auctions.

Euronext Paris XPAR Paris France ±10% (TH, VI) ±2% 5‐min cooling period for dynamic limit hit.

Georgian Stock Exchange

Deutsche Borse Group XETR Frankfurt Germany Undisclosed (VI) Undisclosed Volatility interruption auction lasts 2 min.

Eurex Exchange XEUR Frankfurt Germany Undisclosed (VI) Undisclosed Opening auction, volatility interruption auction,

and closing auctions are subject to freezes.

Athens Stock Exchange ATHEX Athens Greece ±10%; ±18% (PL) None Does not apply to first 3 days of IPO stocks.

For all equities on FTSE/ASE 20 Index: 10% up/down

for 15 min and no limit thereafter.

Budapest Stock Exchange BUX Budapest Hungary ±10%, ±15% (TH, ±5% Trading pauses last between 2 to 15 min. BSE halts an

VI) instrument once only in a day.

Nordic Exchange of Iceland XICE Reyjkjavik Iceland Variable (TH, VI) Variable OMXC20, OMXH25, and OMXS30 are subject to ±10% static

and ± 2% dynamic limits

Dynamic ±3% for OMXI15, and ± 5% limit for investment

funds, ETFs, First North and International OMXS shares.

±15% static limit for First North and International OMXS shares.

±10% dynamic and ± 20% static limit for penny stocks

and illiquid shares.

Irish Stock Exchange XDUB Dublin Ireland Variable (VI) ±2% Volatility interruptions can be prolonged in stressful

market circumstances.

Borsa Italiana XMIL Milan Italy ±10% (PL) Variable Price band depends on market segment and industry

Riga Stock Exchange XRIS Riga Latvia ±15% (PL) None

Nasdaq OMX Vilnius Stock Exchange VILSE Vilnius Lithuania ±15% (PL) None

(Continues)

1314

TABLE 1 (Continued)

Panel E: Europe

Luxembourg Stock Exchange LUXXX Luxembourg Luxembourg ±10% (VI, PL) ±5% ±6% static and ± 3% dynamic limit for BEL20 stocks.

Macedonian Stock Exchange XMAE Skopje Macedonia ±10% (PL) None

Borza Malta XMAL Valletta Malta Undisclosed (PL) Undisclosed In effect since regulatory changes in 2014.

Moldova Stock Exchange MSE Chisinau Moldova ±25% (PL) None

Montenegro Stock Exchange MSE Podgorica Montenegro ±10% (PL) None

New Securities Stock Exchange NEX Podgorica Montenegro ±10% (PL) None

Euronext Amsterdam XAMS Amsterdam Netherlands ±10% (VI, TH) ±5% Reference price is re‐adjusted only after an incoming

order has been matched against orders in the

Central Order Book.

Oslo Stock Exchange XOSL Oslo Norway ±15% (VI, TH) ±5% OBX shares only. Other shares are subject to ±25% static

and ± 15% dynamic limit. Implements matching halts

and special observations.

Warsaw Stock Exchange XWAR Warsaw Poland Undisclosed (PL) Undisclosed

Euronext Lisbon XLIS Lisbon Portugal ±10% (VI, TH) ±5% Reference price is re‐adjusted only after an incoming order

has been matched against orders in the Central Order Book.

Bucharest Stock Exchange XBSE Bucharest Romania ±15% (PL) None

Moscow Exchange MISX Moscow Russia ±20% (TH, VI) None Stock‐specific. Call auctions can be hold intraday if

limit is breached.

Belgrade Stock Exchange XBEL Belgrade Serbia Undisclosed (PL) Undisclosed Implemented from December 2016.

Bratislava Stock Exchange SKSM Bratislava Slovakia ±10% (PL) None

Ljubljana Stock Exchange Ljubljana Slovenia ±10% (PL) None Prime market (blue chip) fluctuations are tolerated till ±30%.

Bolsa Valores de Barcelona BMEX Barcelona Spain Variable (VI, PL) Variable Volatility interruption in place if either limit is breached. Call

auction lasts 5 min with 30‐s random end.

Standardized categories for possible static ranges are ±4%, ±5%,

±6%, ±7%, and ± 8%.

Standardized categories for possible dynamic ranges are 1%,

1.5%, 2%, 2.5%, 3%, 3.5%, 4% and 8%.

Bolsa de Madrid BMEX Madrid Spain Variable (VI, PL) Variable Volatility interruption in place if either limit is breached. Call

auction lasts 5 min with 30‐s random end.

Standardized categories for possible static ranges are ±4%, ±5%,

±6%, ±7%, and ± 8%.

Standardized categories for possible dynamic ranges are 1%, 1.5%,

2%, 2.5%, 3%, 3.5%, 4% and 8%.

(Continues)

SIFAT AND MOHAMADTABLE 1 (Continued)

Panel E: Europe

Stockholm Stock Exchange XSTO Stockholm Sweden ±15% (VI, PL) ±5% OMXS30 stocks are subject to ±10% static and ± 3% dynamic

limits.

Static and dynamic limits lead to 3 and 1‐min

SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

suspensions, followed by discrete call auctions.

SIX Swiss Exchange XSWS Zurich Switzerland None (VI, TH) ±1.5%, No MWCB. Large and mid‐small cap stocks face 5

±2.5% and 15‐min trading halts for breaching

dynamic limit.

Ukrainian Exchange XUAX Kiev Ukraine None None

London Stock Exchange XLON London UK Variable (VI, TH) Variable Ranges from ±5% to ±25% depending on market

segment, liquidity, and size of the asset.

Breaching either limit triggers an Automatic Execution

Suspension Period (AESP).

Aquis Exchange AQXE London Pan‐Europe Variable (VI, TH, Variable Collars are set based on market segments.

PL)

Currencies supported include GBP, EUR, DKK, NOK,

SEK, and CHF.

BATS Chi‐X Europe BXE London Pan‐Europe ±10% (VI, TH, PL) ±5% Currencies of 15 participating markets are supported.

Note. This table chronicles the various circuit breakers employed by stock exchanges around the world. The information is procured from a variety of sources including public domain information, voluntary disclosure

by exchanges, fact books, and correspondence with exchange personnel. Participants of the LULD breaker system include BATS Exchange, BATS Y‐Exchange, Chicago Board Options Exchange Incorporated (CBOE),

Chicago Stock Exchange, EDGA Exchange, EDGX Exchange, NASDAQ OMX BX, NASDAQ, National Stock Exchange, NYSE, NYSE Amex, and NYSE ARCA. For the LULD breaker scheme, please refer to Section 3 in

main body of this paper. The acronyms PL, TH, and VI correspond to price limits, trading halts, and volatility interruptions.

1516 SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

which in turn will increase liquidity and participation orders aggravate an already stressed order‐book flooded

around equilibrium price upon resumption (Copeland & with uninformed orders. In this way, trading halts can

Galai, 1983). Moreover, circuit breakers are hoped to edu- decrease transitory volatility. Moreover, an order‐driven

cate the market when channels of information transmis- market may boast higher liquidity with a trading halt

sion (i.e., quotes) are absent (Greenwald & Stein, 1988) mechanism. In these markets, traders offering standing

and in so doing promote price discovery and decrease limit order suffuse liquidity. In normal circumstances, if

information asymmetry. price drops fast, a trader with standing limit orders will

Both price limits and trading halts brake the price incur loss as the price continues to drop. However, a halt

change mechanism. Whether this slowing down is benefi- changes the mechanism from continuous to single‐price

cial depends on the source of volatility. If the source is auction upon resumption, when all orders are executed

newly available fundamental information, the halt is only at the same settlement price. If a large selling order

delaying the inevitable. Trade stoppage conveys no infor- imbalance exists, all limit order buyers will receive it at

mation on price expectations and could fuel further panic the low clearing price. This protects the limit order buyers

speculation resulting in greater transitory volatility when and encourages them to provide more liquidity in calmer

trade resumes. However, halt of trade before noise traders market circumstances.

execute panic‐driven orders would reduce transitory vola- Contrarily, price limits and halts can increase transi-

tility and hence be desirable.1 Similarly, if excessive noise tory volatility if traders are afraid that trading will stop

trades cause an order imbalance, halts could benefit the before they can submit order, leading to a hastening of

market by protecting noise traders from losses stemming order placement to increase the likelihood of execution.

from operating in a market with suboptimal depth. More- This triggers greater volatility, and rational traders recoil

over, this allows market makers a chance to enter the from trading amid fast‐changing quotes. This phenome-

market and provide liquidity (Kodres & O'Brien, 1994). non is known as the magnet effect, coined by

In this scenario, Greenwald and Stein's (1991) theoretical Subrahmanyam (1994), who expanded on Lehmann's

model shows informed traders' transactional risk drops (1989) predictions and later theoretically demonstrated

when prices move fast due to uninformed trades as this effect. He later postulated that rule‐based halts are

value‐seeking traders cautiously retreat since they are more susceptible to magnet effect due to higher

unsure at what price their trades will execute. Conse- predictability compared with discretion‐based halts

quently, market participants have a greater incentive to (Subrahmanyam, 1997).

be more informed before opening or closing a position. There is a possibility that informed traders may devote

Trading halts can also give brokers more time to col- less time to monitoring the market if they know that they

lect margins. Brennan (1986) argued circuit breakers will be notified if trade is halted. Therefore, market liquid-

can act as a partial substitute for margin requirements if ity may worsen in between trade halts, exacerbating

market participants are unsure about the eventual equi- transitory volatility, and leading—eventually—to more

librium prices during the time out period. For example, trade halts. For countries with multiple exchanges, a cir-

a commodity trader posting 8% margin will lose all if cuit breaker trigger in one market may cause perils in

price goes down by 20%. Should an 8% fall happen imme- other exchanges. If only one market's trade stops, order

diately, though the trader should lose his whole position, flow diverts to the remaining open market(s). Thus,

in practice, he only loses the 8% margin, and the broker solitary circuit breaker regimes may be counterproductive.

stands to collect additional 12% later. However, with a Hence, many early researchers suggested coordination of

circuit breaker of 10% in place, and neither the trader regulation among exchanges to facilitate meeting higher

nor the broker knowing the eventual price trajectory to demand for liquidity in multiple markets instead of one

be 20% lower, the trader has an opportunity to attend to (Lauterbach & Ben‐Zion, 1993).

the first margin call voluntarily. This allows the broker Through a sequential microstructure trade model,

multiple opportunities to collect margin when circuit Glosten and Milgrom (1985) demonstrate that unin-

breakers are in place. Failure to meet the margin call formed traders acquire information by observing the

gives brokers more time to trade to stop the loss. More- trade process. Thus, trade contains an informational

over, when a security or the market is in duress, stop‐loss content, which is learnable only when trade is active.

This leads to opponents arguing that absence of trade

delays price discovery by postponing informed and unin-

1

The term “noise” comes from Black's (1986) definition: “Noise in the

formed agents' reactions to new information (Fama,

sense of a large number of small events is often a cause factor much

more powerful than a small number of large events can be.” Financial

1989). Moreover, if large price moves are induced by

economics literature regards noise a result of sudden liquidity based heavy one‐sided order flow (i.e., order imbalance) and

and frequently inelastic demand on the part of a market participant. trigger a halt, informed traders are forced to temporizeSIFAT AND MOHAMAD 17

partial or full trading strategies, and whatever volatility groundwork for later economists to build a theoretical

was due to take place is splattered over subsequent trad- framework for circuit breakers.

ing sessions, typically with reduced liquidity (Chordia,

Roll, & Subrahmanyam, 2002; Seasholes & Wu, 2007).

5.1 | Pioneer models

Regarding this, Roll (1989) remarks: “… most investors

would see little difference between a market that went First, Greenwald and Stein's (1991) model operates under

down 20 percent in one day and a market that hit a 5 per- the assumption that circuit breakers strive to re‐establish

cent down limit four days in a row. Indeed, the former the information flow when information transmission is

might very well be preferable.” interrupted somehow. In this model, traders are disin-

To sum up, opponents' view on circuit breakers can be clined to participate when heightened uncertainty sur-

condensed into four points: volatility spillover across sub- rounds true value of a security. Moreover, a random

sequent trading session, trading interference, delayed and exogenous value was assigned to value‐seeking inves-

information transmission, and gravitational pull or mag- tors who respond to a volume shock from noise traders.

net effect hypothesis. After the flash crash of 2010, fresh This is partially attributable to the uncertainty surround-

questions surfaced as to whether the trading halt devices ing the number of traders engaged in market surveillance

designed in rather simpler trading environments three at that point and magnifies the transactional risk which

decades ago are still relevant in today's high frequency makes traders withdraw from the market whenever unin-

zeitgeist and, if not, to what extent should they be tai- formed traders cause quick price movements. The effect

lored, or should the regulators go back to the drawing of circuit breaker on distribution of number of first

board and start anew. The computerization of trading value‐seeking responders is missing from this model.

and liquidity provision, coupled with trade decentraliza- Nonetheless, the authors' conclusion that the value‐seek-

tion, has led to a distinct rise in volume and volatility in ing informed traders benefit from a superior understand-

the new climate (Brogaard, 2011). Regulators and mar- ing of what is transpiring in the market with active

kets in the United States coordinated on a large‐scale trading halts provided fodder for future theoretical

pilot project after the crash to investigate the efficacy of models.

the classical circuit breaker regime versus recalibrated Kodres and O'Brien's (1994) model promotes Pareto‐

narrow band of single stock price limits. Concurrently, optimal risk sharing by decreasing unanticipated large

European regulators took steps to move away from the price swings and suggests that limits may be effective in

endemic discrete circuit breaker regimes towards a uni- preventing liquidity providers who don't continuously

fied framework to allow circuit breakers to operate across survey the market incur large losses. Slezak's (1994) theo-

venues. To what extent this will succeed remains to be retical framework supposes trade cessation to delay dis-

seen because exchanges have a vested interest in setting semination of private information. Thus, the model

individual rules in a competitive environment to attract shows that trading halts increase risk premia and volatil-

order flow. Nonetheless, Biais and Woolley (2011) posit ity by restricting public flow of information. Chowdhry

that without tailor‐made cross‐platform streamlining and Nanda's (1998) model proposes circuit breakers as a

across markets, circuit breakers cannot be effective any- market stabilizing instrument by eliminating potentially

more since in modern age of high‐frequency trading arbi- troublemaking prices. Their model argues that price

trage occurs across markets and suspending trade in the limits coupled with flexible margin requirement can con-

underlying spot while allowing the derivative trade can siderably stabilize the market.

be dangerous. Chou, Lin, and Yu's (2003) model shows that price

limits can alleviate default risk and lower the effective

margin requirement. This model, an extension of

5 | THEORETICAL B ACKGROUND Brennan's (1986), supports the Brady Commission's

suggestion that coordination of circuit breakers across

Barring Brennan's (1986) conjecture on using price limits markets will facilitate spot and futures price limits to be

as a substitute to margin requirements in the futures mar- partial substitutes for each other and aid contract fulfil-

kets to confirm contract compliance, prior to the Brady ment. For speculative markets, Westerhoff's (2003) model

Commission Report, theoretical discourse on circuit brea- finds price limits to promote social welfare and placate

kers was absent from academia. The earliest discussants, volatility. It should be pointed out here that among the

Kyle (1988), Greenwald and Stein (1988), Lehmann earliest discussants, Fama (1989), Kyle (1988), Lehmann

(1989), Fama (1989), and Moser (1990), provide theoreti- (1989), Telser (1989), and Moser (1990) do not formulate

cal discussions on why circuit breakers can be reasoned a model to support their arguments. Their primary

to be a good or bad idea. These discussions laid the concerns with circuit breakers are—as mentioned18 SIFAT AND MOHAMAD

earlier—regarding volatility spillover, price discovery trade interruption parries resolution of information

delay, restricted access to liquidity, and trading uncertainty and levies undue risk on both informed and

interference. uninformed investors. In experimental simulation

settings, Ackert, Church, and Jayaraman (2001) find that

traders accelerate their orders when faced with imminent

5.2 | Discrete trading

trade barrier—implying magnet effect.

Although the theoretical discussions so far rely on simple,

continuous trading‐based circuit breakers, Madhavan

(1992) proposes a switch to call auctions in times of 5.4 | Agent‐modelling approach

market duress. His model shows that continuous markets Using a market model with heterogeneously informed

may not be viable or desirable when information asym- agents, Anshuman and Subrahmanyam (1999) show that

metry is high. Hence, adopting a pure trading halt can circuit breakers reduce the bid‐ask spreads as informed

worsen the original problem because once trading is traders need to procure less information, though this

halted, resuming continuous trade with re‐established comes at a cost of diminished price efficiency. Therefore,

information flow may be difficult or even impossible. the authors conclude the optimal price limit to be the

The model contends periodic trading mechanisms to be result of a trade‐off between liquidity and informational

more robust in redressing information asymmetry and efficiency. Spiegel and Subrahmanyam (2000) propose

hence suggests a temporary switch to a call auction to an adverse selection‐based model and contend that a

avert market failure. He further argues that a batch mar- trade halt trigger for any stock poses large information

ket is better than a trade halt because the discrete trading asymmetry risk for connected stocks, for example, same

system can stay active when dealers refuse to play market industry or correlated stocks. Kim and Sweeney's (2002)

makers and thereby provide information signals that model shows that informed traders may be reluctant to

allow resumption of continuous trading. The model also “show their hands” when price nears the limit but

proposes a bid‐spread higher than a preset critical level remains distant from equilibrium as the opportunity cost

—set stochastically based on recent volume and spreads would be too high. Thus, circuit breakers may protract an

—to trigger the switch. Madhavan remarks that this existing information asymmetry.

triggering mechanism should outperform the popular

one (at the time) because big price moves may be due

to change in firm fundamentals. Later, using a Bayesian 5.5 | Price abuse and manipulation

model, Harel and Harpaz (2006) predict that tightened Working on a manipulation angle, Edelen and Gervais

limit regulations would impede the price discovery (2003) extend assumptions of agency theory to circuit

process and diminish social welfare. breakers and reason that trading halts can aid principals

(exchanges, regulators) monitor and prevent abusive pric-

5.3 | Magnet effect ing by agents (market specialists, operators). Kim and

Park's (2010) model makes similar claims. Their triperiod

Focusing on trading strategies of informed traders and model of private and public information arrivals shows

liquidity providers, Subrahmanyam (1994) proposes a that when unanticipated private information arrives,

model suggesting the possibility of a magnet effect, first circuit breakers minimize profit potentials of large,

discussed by Lehmann (1989). In this model, rule‐based informed investors who would otherwise gain by price

halts incentivize uninformed traders to accelerate their manipulation, often through disseminating false informa-

trades in a concentrated way, leading to higher ex ante tion beforehand. This restraint on price manipulation,

volatility as the price moves closer to the limit, though however, sacrifices pricing efficiency.

not necessarily due to depressed liquidity. In a follow‐up

paper, Subrahmanyam (1995) shows that discretion‐

based halts outperform rule‐based halts in easing the 6 | EMPIRICAL WORKS

magnet effect. In a later paper, Subrahmanyam (1997)

shows that when facing a realistic likelihood of a trig- Many studies have examined circuit breakers from a wide

ger‐hit, informed traders postpone their orders to prevent array of angles. In this section, we categorize the studies

a halt. Because this dampens liquidity, the model suggests according to the four major points of contention between

introduction of discretionary randomness in the trigger- proponents and opponents. The discussions in Subsec-

ing mechanism to encourage higher liquidity. In a round- tions 6.1 to 6.4 are complemented by Table 2, which

about way, this phenomenon was shown by Slezak (1994) depict summarized findings of the major empirical works

through a multiperiod market closure model, whereby in this field. Interestingly, from the tables, someYou can also read