Campaign Promises, Democratic Governance, and Environmental Policy in the U.S. Congress1

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

bs_bs_banner

The Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2013

Campaign Promises, Democratic Governance, and

Environmental Policy in the U.S. Congress1

Evan J. Ringquist, Milena I. Neshkova, and Joseph Aamidor

One important criterion for assessing the quality of democratic governance is the extent to which the

policy process effectively translates citizen preferences into collective choices. Several scholars have

observed a discrepancy between citizen preferences for strong environmental protection and weak

policies adopted in the United States, indicating that the United States may fall short on this criterion.

We examine one possible mechanism contributing to this discrepancy—legislator defection from cam-

paign promises. Our data indicate that legislators in the U.S. Congress routinely defect from their

campaign promises in environmental protection, undermining the link between citizen preferences and

policy choice. We also find that legislators are much more likely to defect from pro-environmental

campaign promises, which moves government policy toward less stringent environmental programs.

Finally, the propensity of legislators to defect from their campaign promises is systematic, with

defection affected by partisanship, constituency influence, the influence of the majority party, and the

likely consequences of defection for policy choice. These findings contribute empirical evidence relevant

to the “mandate theory” perspective on how citizen preferences are translated into collective choices

through the policy process. These findings may also complement research in comparative politics

concluding that legislatures selected through single member districts adopt less stringent environmen-

tal policies than do legislatures chosen via proportional representation in that the mechanism for this

effect may go through legislator defection from campaign promises.

KEY WORDS: democratic representation, campaign promises, roll-call votes, environmental policy,

Project Vote Smart, NPAT

Introduction

At the beginning of the modern environmental era, the United States was broadly

looked to as a leader for the strength and scope of its environmental protection

policies. More recently, observers have pointed out that environmental policies in the

United States lag behind those in other advanced industrial democracies (Switzer,

2001; Vig & Faure, 2004). If citizen support for environmental protection is system-

atically lower in the United States, then less aggressive policies would be an indicator

of effective democratic governance. But by most measures, citizen support for envi-

ronmental protection is no different in the United States than in these other nations.

For example, an average of 61.8 percent of citizens in 10 Western European nations

365

0190-292X © 2013 Policy Studies Organization

Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA, and 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ.366 Policy Studies Journal, 41:2

and Japan responded that they would be willing to pay higher prices in return for

stronger environmental protection regulations. In the United States during the same

period, this figure is 65 percent. Similarly, an average of 64.7 percent of citizens in 10

Western European nations and Japan responded that they would support greater

efforts at environmental protection even at the expense of economic growth. In the

United States during the same time period, this figure is 58 percent (Dunlap, Gallup,

& Gallup, 1999). An average of 96.8 percent of citizens in 17 Western European

nations and Japan supported government efforts to protect the environment. In the

United States during this same period, the figure is 96 percent (Mertig & Dunlap,

2001). Finally, an average of 8.4 percent of citizens in 17 Western European nations

and Japan belonged to an environmental interest group. In the United States during

this same period, the figure was 15.9 percent (Dalton, 2005). These observations

suggest two research questions:

1. Why does the policy process in the United States produce weaker environmental

policies than citizens might prefer?

2. Why does the policy process in the United States produce weaker environmental

policies than in other industrial democracies?

In this manuscript we address the first question by examining one possible

source of slippage between citizen preferences and public policy—the extent to

which elected officials defect from their campaign promises. We investigate this

mechanism by examining the correspondence between the environmental campaign

promises and the policy choices made by members of the U.S. House of Represen-

tatives and U.S. Senate between 1992 and 2004. Specifically, we measure the extent of

defection from campaign promises, and we predict the propensity of legislators to defect

from their campaign promises. Our results indicate that legislators in the United

States routinely defect from their campaign promises, undermining the link between

citizen preferences and government policy choices, and posing difficulties for

mandate theory as an explanation for how these preferences are translated into

policy choices within democratic systems. In addition, we find that legislators are

significantly more likely to defect from pro-environmental campaign promises,

which has the effect of moving environmental policy toward less stringent programs.

Our findings may also have implications for the second question, as more frequent

defection from campaign promises in single-member district (SMD) legislative

systems like the United States may help account for the observation that the United

States and other SMD systems adopt weaker environmental policies than do nations

with legislatures chosen via proportional representation (PR).

The remainder of the manuscript proceeds as follows. First, we examine the role

of campaign promises in effective democratic governance. Second, we discuss our

methods of measuring campaign promises and for linking campaign promises to

legislator policy choice. Third, we look at the frequency with which members of the

U.S. Congress defect from their campaign promises in environmental policy. Fourth,

we describe the models used to predict the propensity of legislators to defect from

campaign promises in environmental protection. Finally, we explore the implicationsRingquist/Neshkova/Aamidor: Promises, Governance, and Policy in U.S. Congress 367

of our results for the observation that legislatures selected through SMDs adopt less

stringent environmental policies than do legislatures chosen via PR.

Campaign Promises, Representation, and Environmental Policy

Campaign Promises and Effective Democratic Representation

The most common theory of democratic representation, often labeled mandate

theory, sees popular preferences being translated into public policy through a major-

ity of voters choosing representatives whose policies they prefer.2 Sullivan and

O’Connor (1972) offer four conditions that must be met if elections are to facilitate

public influence over policymaking via mandate theory:

1. Opposing candidates for office must offer voters differing issue positions.

2. Voters must perceive the issue positions of candidates.

3. Voters must cast their ballots on the basis of these perceived issue positions.

4. Winning candidates must vote in accordance with their preelection issue

positions.

The requirements of mandate theory as employed by Sullivan and O’Connor

(1972), McDonald, Mendes, and Budge (2004), and others are virtually identical to

Mansbridge’s notion of “promisory representation” where candidates seek to attract

voters by making promises regarding future policy choices, and voters evaluate

candidates based upon these promises (Mansbridge, 2003). In promisory represen-

tation, “voters’ power works forward to hold representatives to the promises they

made at election time” (Disch, 2011, p. 101). For both mandate theory and promisory

representation, then, legislator fidelity to campaign promises is a necessary condition

for effective democratic governance.

While there is widespread popular and scholarly skepticism regarding each of

the four elements of mandate theory, the empirical evidence suggests that conditions

1–3 may be commonly met in practice, at least in the United States. First, the Demo-

cratic and Republican parties offer meaningfully different issue positions to voters

both generally (Ansolabehere, Snyder, & Stewart, 2001a; Erikson & Wright, 2001;

Kahn & Kenney, 2001) and regarding environmental policy in particular (Shipan &

Lowry, 2001). Second, despite the perception that voters in Congressional elections

are poorly informed, several studies indicate that many voters, much of the time,

correctly perceive the issue positions of candidates (Aldrich, Sullivan, & Borgida,

1989; Ansolabehere & Jones, 2010; Buttice & Stone, 2012; Kahn & Kenney, 2001;

Lodge, Steenbergen, & Brau, 1995; Wright & Berkman, 1986). Third, much of this

research also concludes that voters’ choices in elections are influenced by and/or

reflect these perceived differences in candidate issue positions (Ansolabehere &

Jones, 2010; Lodge et al., 1995; Toms & Van Houweling, 2008; Wright & Berkman,

1986). To quote Phillip Edward Jones, “the buck that stops with members of368 Policy Studies Journal, 41:2

Congress is for the positions that they take, not for the policy outcomes that they

preside over” (Jones, 2011, p. 764).

This evidence regarding the applicability of conditions 1–3 does not mean that

the debate over these conditions is settled. This evidence does suggest, however, that

citizens are more competent than previously believed, and therefore more capable of

expressing coherent preferences and holding their representatives accountable for

actions that are incompatible with these preferences (Disch, 2011). By contrast, we

know very little about condition 4. One piece of early research demonstrated that

members of the House of Representatives in the 90th Congress voted congruently

with preferences expressed prior to their election (Sullivan & O’Connor, 1972). More

recently, Ansolabehere, Snyder, and Stewart (2001b) found a high level of congru-

ence between candidate policy positions and roll call votes in the 103rd through

105th Congress across several issue areas. By examining this question in the aggre-

gate, however, neither of these studies evaluated the extent to which representatives

defected from specific campaign promises. Ringquist and Dasse (2004) provide what

may be the only systematic investigation of whether candidates for Congress keep

specific campaign promises after they are elected. While these authors found that

legislators voted consistent with their campaign promises in a majority of instances,

this study is quite limited in that it examined a single chamber (the U.S. House of

Representatives) for a single Congress (the 105th). More evidence is needed as to

whether condition 4 of mandate theory holds in practice.

Campaign Promises, Environmental Politics, and Environmental Policy

The link between fidelity to campaign promises and effective democratic repre-

sentation applies to all policy areas. We argue here that the characteristics of envi-

ronmental politics make defection from campaign promises especially likely in

environmental policy, and that these defections should move legislative choice

toward less stringent environmental policies.

In the United States, environmental protection is a salient public issue but a

much less salient electoral issue for the majority of citizens. That is, large majorities

support greater governmental efforts to protect and improve environmental quality,

but few voters cast their votes on the basis of environmental issues (see Dunlap, 1995;

Rosenbaum, 2010). Moreover, opponents of environmental regulation generally have

more resources, and carry more clout in Congress, than do supporters of environ-

mental protection (Kamieniecki, 2006; Kraft, 2006). In this situation, candidates face

strong incentives to make pro-environmental campaign promises consistent with

public opinion. After the election, however, lobbyists and other powerbrokers

employ their resources to encourage members of Congress to vote the anti-

environmental position on legislation. Because few voters cast their ballots on the

basis of the environmental policy choices of legislators, there are few electoral

repercussions for this behavior. Such a situation is ripe for defection.

The argument in the preceding paragraph has two observable implications: first,

that defection from campaign promises should be more common in environmentalRingquist/Neshkova/Aamidor: Promises, Governance, and Policy in U.S. Congress 369

protection than in other policy areas; and second, that legislators should be more

likely to defect from pro-environmental campaign promises than from anti-

environmental campaign promises. This second implication might even be consid-

ered rational, as pro-environmental promises are consistent with general citizen

preferences while defection from these promises is consistent with the preferences of

the most powerful stakeholders in the legislative environment. A predominance of

defection from pro-environmental campaign promises will produce more anti-

environmental votes on legislation, thereby moving policy choices toward less strin-

gent environmental policies. Because we only examine environmental policy, we

cannot test the first implication. We can test the second.

Connecting Campaign Promises to Policy Choices

In order to measure the frequency of defection from campaign promises, we

need a measure of candidate campaign promises and a method for connecting these

promises to specific policy decisions made by legislators.

Measuring Campaign Promises

No source of information regarding campaign promises is without problems.

Relying upon campaign literature, advertising, or stories in newspapers presents

serious logistical difficulties if one wants to obtain data for all major party candidates

(though see Hill, 2001, and Sulkin, 2005). These sources pose two additional prob-

lems for systematic assessments of the extent to which candidates keep their cam-

paign promises: (i) candidates may not express issue positions in the same policy

areas, and (ii) the information these sources provide regarding candidate policy

positions is often vague and typically avoids controversial issues (Klotz, 1997; West,

1993). Faced with these problems, previous scholars have gathered information on

the preelection policy preferences of candidates through surveys (Barrett & Cook,

1991; Sullivan & O’Connor, 1972; Wright & Berkman, 1986). While these surveys

overcome the problems noted previously, they cannot properly be considered cam-

paign promises because the policy positions expressed in the surveys were never

made public, and therefore were unavailable to voters.

We obtain data on candidate campaign promises from the National Political

Awareness Test (NPAT). In each election since 1992, Project Vote Smart, a nonprofit,

nonpartisan organization, has surveyed American legislative candidates about their

positions on specific issues. The NPAT provides candidates with lists of policy

alternatives, and asks the candidates to identify which of these options they support.

We take our data for campaign promises from the sections of the 1992–2002 NPATs

dealing with environmental protection.3 We coded each candidate’s response to each

of the 57 environmental policy questions asked during this period, attaching a score

of 0 to “anti-environmental” responses (e.g., opposition to strengthening the Clean

Water Act) and a score of 1 to “pro-environmental” responses (e.g., supportive of

strengthening the Clean Water Act).4370 Policy Studies Journal, 41:2

We contend that this measure of the expression of candidates’ intentions is

superior to those used in the past. Critically, Project Vote Smart intends for NPAT

responses to be interpreted as campaign promises, and advertises them as such (G.

C. Wright, personal communication, January 15, 2006). Compared with the survey

results used in previous research, NPAT responses are eminently public. News

programs on all major networks, each of the major weekly newsmagazines, and

dozens of the most prominent daily newspapers in the United States have featured

articles on the candidate information contained in the NPAT. The NPAT website

receives more than 16 million hits each day, and Project Vote Smart staff responds to

hundreds of thousands of additional inquiries each year via telephone (Project Vote

Smart, 2007). In some ways, information regarding candidate policy intentions from

the NPAT may be of higher quality than similar information from the candidates’

campaigns, as the NPAT forces all candidates to take clear positions on specific policy

issues. A final indicator of the value of the NPAT is the frequency with which

scholars are relying upon this survey to measure candidate issue positions

(Ansolabehere et al., 2001a, 2001b; Erikson & Wright, 2001; Ringquist & Dasse, 2004;

Shor, Berry, & McCarty, 2010; Shor & McCarty, 2011).5

Matching Campaign Promises to Legislator Policy Choices

We measure legislators’ policy choices using roll call votes on environmental

legislation. Roll calls do not represent all actions Senators and Representatives can

take to affect public policy (Hall, 1996; Sulkin, 2005). Moreover, as legislation often

contains elements relating to widely different policy areas, it is sometimes difficult

to use individual roll call votes to gauge the specific policy consequences of actions

taken by members of Congress. Most important legislative policy decisions,

however, are recorded using roll call votes, and roll calls are the most commonly

used measure of Congressional behavior in academic research. We take steps to

assure that our roll calls represent specific policy decisions by excluding appropria-

tions bills and omnibus bills. In addition, a large percentage of our roll calls are not

on bills per se, but on specific amendments to these bills.

We employed three tactics for identifying roll call votes related to specific NPAT

questions. First, we examined the brief reported summaries of all roll call votes taken

in the House and Senate in the 103rd–108th Congresses. When these summaries

indicated that a bill or amendment might be related to one of the NPAT questions, we

obtained a detailed bill summary to confirm this possibility. Second, recognizing that

the first approach might miss some relevant legislation, we crafted three keyword

phrases for each of the 57 NPAT questions, used these keywords in searches of all

bills and amendments introduced in the House and Senate in the 103rd–108th

Congresses, and examined closely the summaries and legislative histories of all bills

and amendments identified this way. Third, we compared all of the key roll call votes

identified by the League of Conservation Voters (LCV) in the 103rd–108th Con-

gresses with the 57 NPAT questions. Any relevant key votes that were not identified

using the first two search protocols were added to the data set. Using these tactics, we

identified 87 roll call votes in the House and 62 roll call votes in the Senate directlyRingquist/Neshkova/Aamidor: Promises, Governance, and Policy in U.S. Congress 371

related to questions from the environmental policy sections of the NPAT. We coded

legislators’ votes on each roll call, assigning a value of 0 to anti-environmental votes

and a value of 1 to pro-environmental votes.

In many cases, matching roll call votes to NPAT responses was quite easy. For

example, the 2002 NPAT asked candidates whether they supported the increased use

of alternative fuel technology. One matched roll call vote is 108.2.321 on House

amendment 624 to increase spending on renewable energy programs by $30 million.

In other cases, matches were more difficult. For example, the 1996 NPAT asked

candidates for Congress whether they supported requiring the federal government

to reimburse citizens when environmental regulations limit the use of private prop-

erty. One matched roll call vote is 105.2.197 on Senate bill 2271, which simplified

access to the federal courts for injured parties whose rights and privileges have been

deprived by final actions of federal agencies. While the title and brief description of

the bill are not obviously related to the NPAT question, a detailed examination of the

bill’s contents shows that the sole rationale for the bill was to make it easier for

citizens to sue federal agencies for reimbursement when environmental regulations

reduced the value or otherwise limited the use of their property. Clearly, then, a vote

in favor of Senate bill 2271 is consistent with an NPAT response favoring govern-

mental compensation for regulatory takings in environmental protection.

How Often Do Legislators Defect from Campaign Promises?

We use the NPAT responses and matched roll call votes described previously to

construct a dichotomous variable coded 1 whenever a member of Congress defects

from their campaign promise (i.e., when their roll call vote is inconsistent with their

NPAT response) and 0 otherwise. Aggregating this variable across all legislators and

bills, we find that from 1993 through 2004, members of the House of Representatives

defected from their campaign promises 31 percent of the time, while Senators

defected 41 percent of the time (see Table 1).6

These single figures for each chamber mask significant heterogeneity in defec-

tion. First, defection is much more likely from pro-environmental campaign prom-

ises than from anti-environmental campaign promises. In the House of

Representatives, anti-environmental campaign promises were kept nearly 78 percent

of the time (defection rates were 22.1 percent), while pro-environmental campaign

promises were kept only 60.4 percent of the time (defection rates were 39.6 percent).

Stated differently, while our data set is split almost evenly between pro-

environmental (52.7 percent) and anti-environmental (47.3 percent) campaign prom-

ises, 66.6 percent of the defections in our data set were from pro-environmental

campaign promises. These figures are roughly similar in the U.S. Senate, though

overall defection rates were higher. By a 2:1 margin, then, defections moved legis-

lator policy choice in a more anti-environmental direction.

Second, the propensity to defect varies across issue areas. We calculate defection

rates for seven issue areas in environmental policy, and Table 1 shows that the

probability of defection varies substantially across these issue areas. While patterns

of defection across issues differ for the House and Senate, defection rates are gener-372 Policy Studies Journal, 41:2

Table 1. Proportion of the Time Members of Congress Defect from Campaign Promises on

Environmental Policy Roll Call Votes, 103rd–108th Congress

House Defection Rate Senate Defection Rate

Overall defection rate 0.31 0.41

By valence of campaign promise

Pro-environmental promise 0.40 0.44

Anti-environmental promise 0.22 0.34

By Congress

103rd 0.34 0.33

104th 0.28 0.27

105th 0.34 0.34

106th 0.34 0.52

107th 0.47 0.45

108th 0.21 0.41

By issue type

Pollution control 0.25 0.37

Natural resources 0.27 0.34

Property rights 0.28 0.23

Regulatory reform 0.34 0.17

Climate change 0.30 0.42

Energy 0.42 0.45

Endangered species 0.48 0.49

By party

Democrat 0.34 0.30

Republican 0.29 0.47

ally higher for legislation addressing energy policy and endangered species protec-

tion, while defection rates are generally lower for legislation seeking to establish or

redefine property rights or reform environmental regulation.

Third, the propensity to defect varies over time. We see that in the House the

defection rate was significantly higher during the 107th Congress, while in the Senate

defection peaked during the 106th Congress. In neither chamber do we see any trend

in defection rates over time, and we note that the higher overall defection rate in the

Senate is not a consistent phenomenon, but an artifact of the 106th and 108th Con-

gresses. We consider two possible explanations for these differences across Con-

gresses; though given the small sample size (6 Congresses), our results should be

seen as speculative rather than definitive. First, research on parliamentary systems

has found lower congruence between citizen preferences and policy choices in

coalition governments than in majority governments (Blais & Bodet, 2006; Golder &

Stramski, 2010). A similar phenomenon may operate in the United States, with

higher defection rates during periods of divided party control over the legislature.

During our time frame, legislative control was divided only during the 107th Con-

gress, but this Congress saw the highest levels of defection in the House and the

second highest in the Senate. Second, defection rates may vary as a function of the

different mix of issues addressed by each Congress. To assess this explanation, for

each Congress we calculated the proportion of roll call votes cast in issue areas

identified in Table 1 where defection rates exceeded .40, and correlated this with the

defection rate. This correlation is a robust .46, indicating that the defection rates are

highest in Congresses with large proportions of bills addressing energy policy,Ringquist/Neshkova/Aamidor: Promises, Governance, and Policy in U.S. Congress 373

climate change, and endangered species. This suggests that defection rates differ

across Congresses not because individual propensities to defect differ over time, but

because the relative frequency of roll call votes in high defection issue areas does.

Predicting Defection from Campaign Promises

The Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in the prediction models is a dichotomous indicator of

whether a particular legislator defected from her campaign promise (coded 1). This

is the same variable used to construct Table 1. Not all members of Congress

responded to the NPAT, however, and for these members we are missing informa-

tion regarding defection (i.e., the dependent variable is partially unobserved). We

might expect that the decision to respond to the NPAT is correlated with the decision

to defect from the NPAT response—e.g., legislators intending to break a campaign

promise may be unwilling to advertise the campaign promise in the first place. In

this situation, NPAT responses and defection are jointly determined, and the partial

observability of NPAT responses is compounded by their endogeneity. The tradi-

tional approach for dealing with partially observed, binary endogenous variables was

developed by Heckman (1979; see also Puhani, 2000). Our original models of defec-

tion employed one equation predicting the propensity of a winning candidate to

respond to the NPAT and a second equation predicting the propensity to defect (i.e.,

we employed bivariate probit models with selection). Diagnostics from these models

showed that NPAT responses and defection are independent after controlling for the

other variables in the defection model (see the Wald tests in Table 2). Therefore, we

report the results from simple probit models in Table 2.

A Baseline Model for Defection from Campaign Promises

As we have seen, there is little research investigating whether elected officials

make policy choices consistent with their preelection pronouncements. Conse-

quently, there is no established body of scholarship identifying the most important

factors explaining legislator defection from campaign promises. One place to begin

this investigation is by considering factors that lead to representation distortion and

bias more generally. For example, McDonald et al. (2004) find that distortion and bias

are larger in legislatures selected through SMDs than through PR. This important

discovery gives us little leverage, however, as all members of the U.S. Congress are

chosen through SMDs. More useful is the research by Kim, Powell, and Fording

(2010, p. 1) demonstrating that “party system polarization seems to be the predomi-

nate factor shaping distortion of governments’ relationship with the median voter.”

While Kim et al. were discussing the gap between citizen preferences and legislative

policy positions, we might also expect that partisan polarization creates distortion

between citizen preferences and legislative policy choices. Specifically, partisanship374 Policy Studies Journal, 41:2

Table 2. Probit Coefficients for Defection from Environmental Campaign Promises,

103rd–108th Congress

Independent Variables House House Senate Senate

Model 1 Model 2 Model 1 Model 2

Base model

Pro-environmental promise -0.673*** -0.392*** -1.063*** -0.938***

(0.039) (0.110) (0.159) (0.205)

Republican party -1.184*** -0.743*** -0.941*** -0.929***

(0.040) (0.159) (0.159) (0.171)

Pro-environmental promise × 2.044*** 1.523*** 1.924*** 1.821***

Republican party (0.051) (0.142) (0.183) (0.268)

Factors enhancing representation

Distance from constituents 0.449*** 0.239*

(0.058) (0.129)

Contributions anti-promise -0.598** 0.277

(0.238) (0.175)

Time since campaign promise — 0.026

— (0.023)

Factors compromising representation

Contributions pro-promise 0.094 0.111

(0.174) (0.105)

Terms in office -0.0002 -0.007

(0.0004) (0.020)

Control variables

Closeness of vote -0.002*** -0.005*

(0.0002) (0.002)

Majority party member -0.064 -0.122

(0.131) (0.108)

Majority party member × 0.001*** -0.001

Closeness of vote (0.0003) (0.003)

Party deviation 0.066 -0.045

(0.192) (0.449)

LCV key vote -0.011 -0.026

(0.030) (0.079)

Environmental extremism -0.006*** 0.005

(0.001) (0.004)

Constant 0.105** -0.213* 0.331** -0.008

(0.034) (0.109) (0.142) (0.256)

Psuedo-R2 0.12 0.15 0.10 0.12

Wald test for independence 2.15 0.85 0.77 0.81

N 14,143 14,131 1,321 1,321

Note: Numbers in parentheses are clustered standard errors.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, one-tailed tests.

LCV, League of Conservation Voters.

may affect the propensity to defect from campaign promises, thereby contributing

to distortion between the policy preferences of voters and the policy choices of

legislatures.

Party polarization has increased in the United States during the past generation.

This polarization is especially noteworthy in the previously bipartisan area of envi-

ronmental policy, with Democrats and Republicans staking out increasingly pro- and

anti-environmental policy positions, respectively (Nelson, 2002; Shipan & Lowry,

2001). The story linking defection and party polarization is not simple and straight-Ringquist/Neshkova/Aamidor: Promises, Governance, and Policy in U.S. Congress 375

forward. We do not expect that members of one party will be more likely to defect

from their campaign promises. Rather, increased partisanship means that members of

each party will be more likely to defect from a particular type of campaign promise. Specifi-

cally, Republicans will be more likely to defect from pro-environmental campaign

promises, while Democrats will be more likely to defect from anti-environmental

campaign promises. Defection then serves to exacerbate preexisting partisan tenden-

cies in environmental policy, pushing policy choices toward extreme positions. This

contributes to short-term distortions between citizen preferences and policy choices

of the sort that Kim et al. (2010) find with respect to legislative policy positions.

While we do not have an expectation regarding the independent effect of

political party on the probability of defection, this is not true for the content of

the campaign promises. Previously we offered an argument as to why U.S. legis-

lators should be more likely to defect from pro-environmental campaign promises,

and Table 1 presents evidence consistent with this argument. In our prediction

model, we expect greater levels of defection from pro-environmental campaign

promises.

Our baseline model predicts defection from campaign promises using partisan-

ship and the content of the campaign promise. To test the baseline model, we use a

dichotomous variable identifying Republican Representatives and Senators (coded

1), a dichotomous variable identifying pro-environmental campaign promises

(coded 1), and an interaction term that is the product of these two variables. The

results are presented in columns 1 and 3 of Table 2, and these results strongly

support the intuition behind the baseline model. The positive coefficients on the

interaction terms indicate that Republicans are more likely to defect from pro-

environmental campaign promises, while the negative coefficients on the Republican

Party variable indicate that these same decision makers are significantly less likely to

defect from anti-environmental campaign promises. By contrast, Democrats are sig-

nificantly less likely to defect from pro-environmental campaign promises (an effect

captured by the pro-environmental promise coefficients) and significantly more

likely to defect from anti-environmental campaign promises (an effect captured by

the constant term).

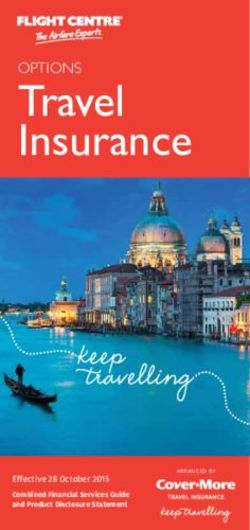

The conditional effect of partisanship on the probability of defection is repre-

sented graphically in Figure 1a (for the House) and 1b (for the Senate). Figure 1a

shows that for Republican members of the House of Representatives, the probabil-

ity of defection rises from 14 percent for anti-environmental promises to 62 percent

for pro-environmental campaign promises. For Democratic representatives, the

comparable figures are 54 percent and 28 percent. Taken together, all members of

the House of Representatives are more likely to defect from pro-environmental

campaign promises (40 percent) than they are from anti-environmental campaign

promises (22 percent). We observe a similar pattern in Figure 1b for the Senate,

where Republicans are more likely to defect from pro-environmental campaign

promises (60 percent to 27 percent) and Democrats are less likely to defect from

pro-environmental campaign promises (23 percent to 63 percent). Overall, Senators

are more likely to defect from pro-environmental campaign promises (44 percent to

34 percent).376 Policy Studies Journal, 41:2

a

0.7

0.6

Probability of DefecƟon

0.5

0.4 Democrats

Republicans

0.3

Overall DefecƟon

0.2

0.1

0

AnƟ-Environmental Promise Pro-Environmental Promise

b

0.7

0.6

Probability of DefecƟon

0.5

0.4 Democrats

Republicans

0.3

Overall DefecƟon

0.2

0.1

0

AnƟ-Environmental Promise Pro-Environmental Promise

Figure 1. (a) U.S. House and (b) Senate Defections from Campaign Promises by Political Party and

Valence of Promise.

A More Complete Model for Defection from Campaign Promises

Partisanship and content are not the only factors contributing to the propensity

to defect from campaign promises. In an effort to specify this process more com-

pletely, we add to the base model factors that might enhance representation, factors

that might compromise representation, and a set of control variables.

Factors Potentially Enhancing Effective Representation. Legislator defection from cam-

paign promises need not always threaten popular sovereignty. We include three

variables that may improve representation by influencing the propensity of defection

from campaign promises. First, the policy choices of legislators are often responsiveRingquist/Neshkova/Aamidor: Promises, Governance, and Policy in U.S. Congress 377

to the wishes of constituencies (Erikson & Wright, 2001; Fenno, 1978; Miller & Stokes,

1963). Therefore, we expect that legislators will be more likely to defect if their policy

preferences are at odds with those of their constituents. Accurately measuring this

concept, which we term electoral distance, is somewhat complicated. We measure

constituency preferences using the most recent Republican candidate share of the

two-party vote for president in each legislative district (designated PRep), and

measure electoral distance using the difference between constituency preferences

(i.e., PRep) and the Republican legislative candidate’s share of the two-party vote in

the most recent election (designated CRep). The effect of a legislator’s distance from

her constituency, however, is conditional upon the direction of the distance and the

type of campaign promise that is made. Consider two examples: Legislator A is a

Republican who gives a pro-environmental NPAT response and wins 51 percent of

the vote in a district where the Republican presidential candidate received only 41

percent of the vote; legislator B is a Democrat who gives a pro-environmental NPAT

response and wins 53 percent of the vote in a district where the Republican presi-

dential candidate received 51 percent of the vote. Looking only at election returns,

legislator A is both more vulnerable (i.e., has a smaller winning margin) and is

further away from her constituency (i.e., a larger distance between her vote share and

the vote share of her party’s Presidential candidate) than is legislator B. We hypoth-

esize, however, that legislator A will receive less pressure to defect because her

pro-environmental campaign promise is more consistent with her constituency’s

preferences (where a majority voted for the Democratic presidential candidate) than

is legislator B’s pro-environmental response (where a majority voted for the Repub-

lican presidential candidate). To accurately capture this dynamic, our measure of

electoral distance is PRep–CRep for candidates that give pro-environmental NPAT

responses, and CRep–PRep for candidates that give anti-environmental NPAT

responses. In either case, higher values are associated with increased pressure to

defect.

Second, in U.S. elections, campaign contributions are a vital mechanism for

stakeholders to communicate their preferences to candidates. If campaign contri-

butions encourage legislators to remain faithful to their campaign promises, these

contributions serve to enhance democratic representation. We only have data for

campaign contributions from opponents of environmental regulation, so this

representation-enhancing function of contributions can only be observed for anti-

environmental campaign promises. Therefore, this independent variable takes on a

value of 0 for anti-environmental campaign contributions going to candidates

making pro-environmental campaign promises, and takes on the value of cam-

paign contributions received for candidates making anti-environmental campaign

promises. A negative coefficient estimate for this variable indicates that campaign

promises encourage members of Congress to remain faithful to anti-environmental

campaign promises.

Third, legislative candidates are asked to respond to the NPAT during each

election. For members of the House, this means that there is no more than a two-year

lag between their articulation of policy preferences and their policy choices, and this

lag is identical for all Representatives. Given the rotating election cycle in the Senate,378 Policy Studies Journal, 41:2

however, Senators may have made their relevant campaign promises anywhere from

one to six years prior to the roll call vote. Objective conditions may have changed

between the time the campaign promise was made and the time the roll call vote was

taken, or significant policy learning may have occurred during this period. Either of

these circumstances may render the original campaign promise less wise. Therefore,

we expect that in the Senate the probability of defection will increase with the time

elapsed since the campaign promise was made. We operationalize this expectation

with a variable measuring the number of years between the NPAT response and the

roll call vote.

Factors Potentially Compromising Effective Representation. We include two variables

that may degrade effective representation by influencing the propensity to defect

from campaign promises. First, while campaign contributions may improve the

quality of representation by encouraging legislator fidelity to campaign promises,

they may also compromise effective representation if they encourage legislators to

defect from campaign promises. Indeed, this latter effect is more commonly stated.

To test for this effect, we include a variable that takes on a value of 0 for legislators

making anti-environmental campaign promises, and takes on the value of campaign

contributions received from anti-environmental interests by candidates making pro-

environmental campaign promises. This variable is the complement to the campaign

contribution variable described earlier. The key difference is that by construction, we

expect that this variable will have a positive relationship with the propensity to

defect from pro-environmental campaign promises.

Second, one of the most forcefully articulated arguments for term limits is that

long-time legislators “go their own way” and lose touch with their constituency.

Parker (1992) formalizes this argument by claiming that over time, legislators seek to

maximize their policymaking discretion. This argument indicates that long-term

legislators may be more likely to defect from their campaign promises. We operation-

alize this expectation using the number of years each legislator has served in office.

Control Variables. We include six control variables in our full model predicting defec-

tion from campaign promises in environmental policy. First, we expect that legisla-

tors will be less likely to defect from their campaign promises when these defections

might significantly affect legislative outcomes. That is, that the closeness of the roll

call vote will have a negative effect on defection, all other things equal. We measure

the closeness of the roll call vote by subtracting the number of votes on the winning

side from the number of votes on the losing side of all roll calls, giving us a variable

where larger values represent closer votes.

Second, in virtually all legislatures majority parties have more resources at

their disposal to entice reluctant legislators to abandon their personal position on

an issue in favor of the official party position (e.g., Cox & McCubbins, 1993). There-

fore, our second control variable takes on a value of 1 for members of the majority

party.

Third, the resources of the majority party are not without limit, and thus it would

be irrational for the majority leadership to encourage defection on all roll call votes.Ringquist/Neshkova/Aamidor: Promises, Governance, and Policy in U.S. Congress 379

Rather, we expect that the leadership will target their resources to pressure for

defections on roll call votes where defections will have the greatest policy conse-

quences: exceptionally close votes. Consequently, our third control variable interacts

majority party membership with the continuous variable measuring the closeness of

the roll call vote. We expect that this interaction term will generate a positive

coefficient, indicating that members of the majority party are more likely to defect

from their campaign promises on close votes.

Fourth, we expect that if legislators defect from their campaign promises, they

will defect toward the position of their political party, and these defections will be

more likely among party deviants (i.e., legislators making campaign promises at

odds with the modal position of party members). We measure the position devia-

tion of legislators in the following way. First, we calculate the proportion of legis-

lators from each party who offer the modal (i.e., majority) response on each NPAT

question, and subtract this proportion from 1. The remainder, dubbed the party

position index, ranges from 0 to .5, with values closer to zero indicating greater

party unity on this issue. Next, we identify legislators whose NPAT responses

differ from the modal party response. We subtract the party position index from

the individual candidate’s position, with the absolute remainder representing indi-

vidual position deviations (this score will range from 0 to 1, with larger numbers

indicating greater deviation). An example helps illustrate this strategy. Assume that

90 percent of Republican legislators support limiting the designation of critical

habitat under the Endangered Species Act. The party position index here would

equal .10. Republican legislators who do not support this restriction are coded as

1 (the pro-environmental position), and the resulting individual position deviation

would be .90. All legislators with positions identical to the majority position of

their party receive deviation scores of 0.

Fifth, each year the LCV identifies a small number of key roll call votes on issues

of critical importance to the environmental policy community. We expect that legis-

lators will be less likely to defect from their campaign promises on issues of greatest

salience to members of the environmental policy subsystem (i.e., on LCV key votes).

We operationalize this expectation using a dichotomous variable coded 1 for LCV

key votes.

Finally, our model of defection would be incomplete without considering the

intensity with which legislators hold their policy preferences. We measure the

intensity of preference regarding environmental policy using a folded index of

LCV scores. Legislators with LCV scores at the chamber mean receive values of

zero on this measure of “environmental extremism,” while legislators with very

high or very low LCV scores receive values near the maximum. Presumably, can-

didates holding extreme positions will be less likely to defect from campaign

promises in this area.

Results and Discussion

Columns 2 and 4 in Table 2 show the results from the full models of defection in

the House and Senate, respectively. We note first that the effects of partisanship and380 Policy Studies Journal, 41:2

the content of the campaign promise from columns 1 and 3 remain strong and

statistically significant, if somewhat attenuated, in the fully specified models of

defection. Second, each of the statistically significant coefficients in columns 2 and 4

is consistent with a priori expectations.

Specifically, the probability of defection increases with the distance between a

candidate’s preelection policy position and the preferences of her constituency.

When defecting from campaign promises, both Representatives and Senators defect

toward general constituent policy references. In addition, as campaign contributions

from sources hostile to environmental regulation increase, the probability that a

legislator will defect from an anti-environmental campaign promise goes down.

More precisely, a $100,000 increase in campaign contributions from these groups is

associated with a 2 percent reduction in the probability of defecting from an anti-

environmental campaign promise. The mean contribution from these groups is only

$27,814, which suggests that for the typical legislator, campaign contributions have

a negligible effect on the probability of defection. The maximum value of this vari-

able is over three million dollars, however, with several legislators receiving more

than one million dollars in contributions from these groups. For these legislators, our

model suggests that campaign contributions are associated with a meaningful reduc-

tion in the probability of defecting from anti-environmental campaign promises.

Each of the coefficients discussed in this paragraph serve to enhance the quality of

representation by moving legislative policy decisions closer to constituent prefer-

ences and/or reducing the probability of defection.

Three of the control variables also display statistically significant coefficients in

the expected direction. First, both Representatives and Senators are less likely to

defect from campaign promises on close votes. Defection is less common when it

is more consequential. The effect of the closeness of the vote is attenuated for

members of the majority party in the House of Representatives, as illustrated by

the negative parameter estimate on the interaction term. This result is consistent

with a story that the majority party marshals its limited resources to encourage

defection among members only when it is likely to change the outcome of a roll

call vote. Still, the influence of majority party status is not enough to reverse the

effect of vote closeness on defection, as the parameter on the interaction term is

only one half the size of the vote closeness parameter. Members of the majority

party are still less likely to defect as roll call votes get close; they are just more

likely to defect under these circumstances than are members of the minority party,

although the effect is not large. On tie votes, the probability of defection is .23 for

members of the majority party and .21 for members of the minority. Finally, rep-

resentatives holding intense preferences are less likely to defect from their cam-

paign promises. Holding all other variables at their mean values, a member of the

House of Representatives with a mean LCV score has a .29 probability of defection,

while an identical representative with the most extreme LCV score (0 or 100) has

a probability of defection equal to .24.

Some of the parameters showing no effect on the probability of defection are also

of interest. For example, campaign contributions from opponents of environmental

regulation do not increase the probability of defection from pro-environmental cam-Ringquist/Neshkova/Aamidor: Promises, Governance, and Policy in U.S. Congress 381

paign promises, and long-term members of Congress are no more likely to defect

from campaign promises. Observers of American politics may find these results

comforting. On the other hand, fidelity to campaign promises is no more likely on

especially important pieces of environmental legislation.

Campaign Promises, SMDs, and Environmental Policy

Social scientists have long recognized that the policy choices of democracies

differ from those of autocracies in areas as varied as trade (Mansfield, Milner, &

Rosendorf, 2000), currency exchange rates (Freeman, Hays, & Stix, 2000), and the use

of force (Maoz & Russett, 1993). Congleton (1992) brought this perspective to the

study of environmental policy, concluding that democracies adopt more stringent

domestic environmental policies than do autocracies (see also Bättig & Bernauer,

2009; Neumayer, 2002; Roberts, Parks, & Vasquez, 2004). The effect of democracy on

public policy is not constant, however, and the design of democratic institutions has

a meaningful effect on the policy choices of governments (e.g., Congleton &

Swedenborg, 2006; Lijphart, 1999). Of particular relevance for us is the observation

that legislatures selected through SMDs adopt less stringent environmental policies

than do legislatures selected through PR. For example, when examining the electoral

rules governing national legislatures in 86 democracies, Fredriksson and Millimet

(2004) conclude that SMD legislatures adopt lower fuel taxes, participate in fewer

international environmental agreements, and invest less in environmental governing

capacity. Lijphart (1999) and Poloni-Staudinger (2008) also note that majoritarian

systems characterized in part by SMD legislatures adopt weaker environmental

policies, and Fredriksson and Wollscheid (2007) go so far as to conclude that the

positive relationship between democracy and the stringency of domestic environ-

mental policy is driven almost exclusively by Parliamentary democracies with PR

legislatures.

The observation that SMD systems like the United States adopt weaker envi-

ronmental policies begs the question of why this might be so. Persson and

Tabellini (1999) offer one explanation. Political parties in SMD systems can succeed

by appealing to the preferences of a subset of their constituency. At the extreme,

one party can fully populate the legislature by representing the interests of barely

50 percent of voters. By contrast, party success in PR systems is maximized by

appealing to as broad a constituency as possible (see also Milesi-Ferretti, Perotti, &

Rostagno, 2002).7 One implication from this work is that legislators in SMD

systems will emphasize policies providing local public goods and appealing to

particularistic interests, while PR systems provide greater incentives for legislators

to pay attention to aggregate social welfare and global public goods (see also Cox

& McCubbins, 2001). As environmental policy typically generates concentrated

local costs and diffuse national benefits, legislators in SMD systems have a weaker

incentive to advocate for and adopt stringent environmental policies (Fredriksson

& Wollscheid, 2007).

We believe that legislator defection from campaign promises may offer a

second, complementary explanation for why SMD systems adopt weaker environ-382 Policy Studies Journal, 41:2

mental policies. Two conditions must be satisfied if defection from campaign

promises is to play this complementary role. First, defection from campaign prom-

ises must move policy decisions toward weaker environmental policies. The analy-

sis here provides a rationale for why defection should be more common for

pro-environmental campaign promises, and provides evidence that defection is

more common for pro-environmental campaign promises. For the United States, at

least, this first condition appears to be satisfied.

Second, defection must be more common in SMD systems than in PR systems.

Offering a plausible rationale for why defection is more common in SMD systems is

not difficult. In PR systems, the notion of campaign promises made by individual

candidates is something of a non sequitur, as legislators in PR systems tend to be

selected from party lists. Moreover, the strong party discipline traditionally exercised

in PR systems means that defection from party policy positions is unusual. Coupled

with strong party discipline, the corporatist character of many PR systems means that

legislators face less pressure from interest groups seeking to influence their policy

choices. By contrast, SMD systems typically have candidate-centered campaigns,

weaker party discipline, and pluralist interest representation. Each of these charac-

teristics increases the probability that legislators in SMD systems will make and defect

from campaign promises, compared with their counterparts in PR systems. While

there is little empirical evidence regarding the extent to which legislators defect from

their campaign promises, the evidence we do have suggests that defection is indeed

more likely in SMD systems. For example, studying the U.S. House of Representatives

in the 105th Congress, Ringquist and Dasse (2004) find that legislators defected from

their campaign promises 27 percent of the time.8 Moreover, Table 2 shows that

defection from environmental campaign promises in the United States ranges from 31

percent in the House to 41 percent in the Senate. By contrast, a comparable analysis of

the Swiss legislature—where a large majority of representatives are chosen via

PR—found defection rates of only 15 percent (Schwarz, Schädel, & Ladner, 2010).

More convincingly, a recent summary of the small empirical literature on this question

concludes that compared with presidential systems like that in the United States,

“parliamentary regimes like the Westminster systems of Britain and Canada posi-

tively influence the likelihood that political parties keep their promises once elected”

(Pétry & Collette, 2009, p. 78). Therefore, the second condition may be satisfied as well.

We do not want to overstate the case—the results in Table 2 do not provide

evidence that defection from campaign promises accounts for why SMD systems

adopt weaker environmental policies. We are simply pointing out that if the

high levels of defection from pro-environmental campaign promises in the United

States also characterize other SMD systems, this might help account for this

phenomenon.

Concluding Remarks

We began this manuscript with two goals: measuring the extent to which can-

didates for the U.S. Congress defect from their campaign promises in environmen-

tal policy, and investigating whether these defections are systematic. Regarding theRingquist/Neshkova/Aamidor: Promises, Governance, and Policy in U.S. Congress 383

first goal, when given the opportunity to fulfill their campaign promises in envi-

ronmental protection, members of the House of Representatives defect from these

promises 31 percent of the time. The figure for Senators is 41 percent. While leg-

islators in both chambers exhibit fidelity to preelection policy preferences in a clear

majority of cases, defection is a common characteristic of legislative behavior in the

United States. Regarding the second goal, defection from campaign promises is

a systematic phenomenon. The propensity for defection is dominated by parti-

sanship and the content of the campaign promise. Overall, defection from

pro-environmental campaign promises is twice as common as defection from

anti-environmental campaign promises, and Republicans are more likely to defect

from pro-environmental campaign promises while Democrats are more likely to

defect from anti-environmental pronouncements. In addition, legislators defect

toward the general ideological position of their constituents, and are marginally

less likely to defect when they hold extreme policy positions or when the conse-

quences of defection for policy choice are greatest.

Our results have implications for the quality of democratic governance in envi-

ronmental policy. First and most directly, defection from campaign promises clearly

undercuts effective democratic representation and poses a challenge to the applica-

bility of mandate theory as a mechanism for linking citizen preferences to environ-

mental policy choices in the United States. Defection from campaign promises also

shapes the direction of environmental policy. Because legislators in the United States

are significantly more likely to defect from pro-environmental campaign promises,

defection has the effect of moving government policy toward weaker environmental

programs. Thus, defection from campaign promises may help account for the obser-

vation that the United States adopts weaker environmental protection policies than

its citizens might prefer. Second, defection from campaign promises may be one

mechanism behind the observation that SMD systems adopt less stringent and less

comprehensive environmental policies. The ultimate contribution of defection to

observed differences in environmental policy between SMD and PR democracies

hinges on the extent to which defection rates in the United States are representative

of legislative defection in other SMD systems.9 We leave the answer to this question

to future research.

Notes

1. This research was funded by NSF grant SES-0453561.

2. This perspective closely parallels what Mansbridge (2003) calls “promissory” representation in which

candidates seek to attract voters by making promises regarding future policy choices, and voters

evaluate candidates based upon those promises.

3. The 1992 NPAT asked candidates to take positions on three environmental policy proposals. All other

NPATs asked far more environmental policy questions (9 questions in 1994, 12 questions in 1996, 12

questions in 1998, 11 questions in 2000, and 10 questions in 2002).

4. In 2008 the NPAT was renamed the “Political Courage Test.”

5. Despite this evidence, some readers may still prefer to interpret NPAT responses as “public statements

of policy preferences coupled with a promise of action,” rather than as campaign promises per se. This

interpretation has no effect on the analysis or conclusions in the article.You can also read