Building Consistent Transactions with Inconsistent Replication - Irene Zhang

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Building Consistent Transactions with Inconsistent Replication

Irene Zhang Naveen Kr. Sharma Adriana Szekeres

Arvind Krishnamurthy Dan R. K. Ports

University of Washington

{iyzhang, naveenks, aaasz, arvind, drkp}@cs.washington.edu

Abstract trend, notably Google’s Spanner system [13], which guaran-

Application programmers increasingly prefer distributed stor- tees linearizable transaction ordering.1

age systems with strong consistency and distributed transac- For application programmers, distributed transactional

tions (e.g., Google’s Spanner) for their strong guarantees and storage with strong consistency comes at a price. These sys-

ease of use. Unfortunately, existing transactional storage sys- tems commonly use replication for fault-tolerance, and repli-

tems are expensive to use – in part because they require costly cation protocols with strong consistency, like Paxos, impose

replication protocols, like Paxos, for fault tolerance. In this a high performance cost, while more efficient, weak consis-

paper, we present a new approach that makes transactional tency protocols fail to provide strong system guarantees.

storage systems more affordable: we eliminate consistency Significant prior work has addressed improving the perfor-

from the replication protocol while still providing distributed mance of transactional storage systems – including systems

transactions with strong consistency to applications. that optimize for read-only transactions [4, 13], more restric-

We present TAPIR – the Transactional Application Proto- tive transaction models [2, 14, 22], or weaker consistency

col for Inconsistent Replication – the first transaction protocol guarantees [3, 33, 42]. However, none of these systems have

to use a novel replication protocol, called inconsistent repli- addressed both latency and throughput for general-purpose,

cation, that provides fault tolerance without consistency. By replicated, read-write transactions with strong consistency.

enforcing strong consistency only in the transaction protocol, In this paper, we use a new approach to reduce the cost

TAPIR can commit transactions in a single round-trip and or- of replicated, read-write transactions and make transactional

der distributed transactions without centralized coordination. storage more affordable for programmers. Our key insight

We demonstrate the use of TAPIR in a transactional key-value is that existing transactional storage systems waste work

store, TAPIR - KV. Compared to conventional systems, TAPIR - and performance by incorporating a distributed transaction

KV provides better latency and throughput.

protocol and a replication protocol that both enforce strong

consistency. Instead, we show that it is possible to provide

distributed transactions with better performance and the same

transaction and consistency model using replication with no

1. Introduction consistency.

Distributed storage systems provide fault tolerance and avail- To demonstrate our approach, we designed TAPIR – the

ability for large-scale web applications. Increasingly, appli- Transactional Application Protocol for Inconsistent Replica-

cation programmers prefer systems that support distributed tion. TAPIR uses a new replication technique, called incon-

transactions with strong consistency to help them manage sistent replication (IR), that provides fault tolerance without

application complexity and concurrency in a distributed en- consistency. Rather than an ordered operation log, IR presents

vironment. Several recent systems [4, 11, 17, 22] reflect this an unordered operation set to applications. Successful opera-

tions execute at a majority of the replicas and survive failures,

but replicas can execute them in any order. Thus, IR needs no

cross-replica coordination or designated leader for operation

processing. However, unlike eventual consistency, IR allows

applications to enforce higher-level invariants when needed.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

Thus, despite IR’s weak consistency guarantees, TAPIR

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation provides linearizable read-write transactions and supports

on the first page. Copyrights for third-party components of this work must be honored.

For all other uses, contact the owner/author(s).

globally-consistent reads across the database at a timestamp –

SOSP’15, October 4–7, 2015, Monterey, CA.

Copyright is held by the owner/author(s).

ACM 978-1-4503-3834-9/15/10. 1 Spanner’s linearizable transaction ordering is also referred to as strict

http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2815400.2815404 serializable isolation or external consistency.Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3

2PC Client

Distributed Shard

A

Shard Shard

B C

Shard Shard

A B

Shard

C

Shard

A

Shard

B

Shard

C

Transaction (leader) (leader) (leader)

CC CC CC Protocol BEGIN

BEGIN

execution

READ(a)

Replication

R R R R R R R R R WRITE(b)

Protocol

READ(c)

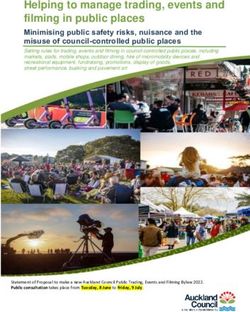

Figure 1: A common architecture for distributed transactional

storage systems today. The distributed transaction protocol consists PREPARE(A)

of an atomic commitment protocol, commonly Two-Phase Commit

prepare

PREPARE(B)

(2PC), and a concurrency control (CC) mechanism. This runs atop a

replication (R) protocol, like Paxos. PREPARE(C)

the same guarantees as Spanner. TAPIR efficiently leverages

COMMIT(A)

IR to distribute read-write transactions in a single round-trip

commit

and order transactions globally across partitions and replicas COMMIT(B)

with no centralized coordination. COMMIT(C)

We implemented TAPIR in a new distributed transactional

key-value store called TAPIR - KV, which supports linearizable

transactions over a partitioned set of keys. Our experiments Figure 2: Example read-write transaction using two-phase commit,

found that TAPIR - KV had: (1) 50% lower commit latency viewstamped replication and strict two-phase locking. Availability

and (2) more than 3× better throughput compared to sys- zones represent either a cluster, datacenter or geographic region.

tems using conventional transaction protocols, including an Each shard holds a partition of the data stored in the system and

implementation of Spanner’s transaction protocol, and (3) has replicas in each zone for fault tolerance. The red, dashed lines

comparable performance to MongoDB [35] and Redis [39], represent redundant coordination in the replication layer.

widely-used eventual consistency systems.

This paper makes the following contributions to the design

is easily and efficiently implemented with a spinning disk but

of distributed, replicated transaction systems:

• We define inconsistent replication, a new replication tech- becomes more complicated and expensive with replication.

To enforce the serial ordering of log operations, transactional

nique that provides fault tolerance without consistency.

• We design TAPIR, a new distributed transaction protocol storage systems must integrate a costly replication proto-

col with strong consistency (e.g., Paxos [27], Viewstamped

that provides strict serializable transactions using incon-

Replication [37] or virtual synchrony [7]) rather than a more

sistent replication for fault tolerance.

• We build and evaluate TAPIR - KV, a key-value store that efficient, weak consistency protocol [24, 40].

The traditional log abstraction imposes a serious perfor-

combines inconsistent replication and TAPIR to achieve

mance penalty on replicated transactional storage systems,

high-performance transactional storage.

because it enforces strict serial ordering using expensive dis-

tributed coordination in two places: the replication protocol

2. Over-Coordination in Transaction Systems enforces a serial ordering of operations across replicas in each

Replication protocols have become an important compo- shard, while the distributed transaction protocol enforces a

nent in distributed storage systems. Modern storage sys- serial ordering of transactions across shards. This redundancy

tems commonly partition data into shards for scalability and impairs latency and throughput for systems that integrate both

then replicate each shard for fault-tolerance and availabil- protocols. The replication protocol must coordinate across

ity [4, 9, 13, 34]. To support transactions with strong con- replicas on every operation to enforce strong consistency; as a

sistency, they must implement both a distributed transaction result, it takes at least two round-trips to order any read-write

protocol – to ensure atomicity and consistency for transac- transaction. Further, to efficiently order operations, these pro-

tions across shards – and a replication protocol – to ensure tocols typically rely on a replica leader, which can introduce

transactions are not lost (provided that no more than half of a throughput bottleneck to the system.

the replicas in each shard fail at once). As shown in Figure 1, As an example, Figure 2 shows the redundant coordination

these systems typically place the transaction protocol, which required for a single read-write transaction in a system like

combines an atomic commitment protocol and a concurrency Spanner. Within the transaction, Read operations go to the

control mechanism, on top of the replication protocol (al- shard leaders (which may be in other datacenters), because

though alternative architectures have also occasionally been the operations must be ordered across replicas, even though

proposed [34]). they are not replicated. To Prepare a transaction for commit,

Distributed transaction protocols assume the availability the transaction protocol must coordinate transaction ordering

of an ordered, fault-tolerant log. This ordered log abstraction across shards, and then the replication protocol coordinatesthe Prepare operation ordering across replicas. As a result, it Client Interface

takes at least two round-trips to commit the transaction. InvokeInconsistent(op)

In the TAPIR and IR design, we eliminate the redundancy InvokeConsensus(op, decide(results)) → result

of strict serial ordering over the two layers and its associated Replica Upcalls

ExecInconsistent(op) ExecConsensus(op) → result

performance costs. IR is the first replication protocol to Sync(R) Merge(d, u) → record

provide pure fault tolerance without consistency. Instead

Client State

of an ordered operation log, IR presents the abstraction of • client id - unique identifier for the client

an unordered operation set. Existing transaction protocols • operation counter - # of sent operations

cannot efficiently use IR, so TAPIR is the first transaction Replica State

protocol designed to provide linearizable transactions on IR. • state - current replica state; either NORMAL or VIEW- CHANGING

• record - unordered set of operations and consensus results

3. Inconsistent Replication Figure 3: Summary of IR interfaces and client/replica state.

Inconsistent replication (IR) is an efficient replication proto-

col designed to be used with a higher-level protocol, like a

distributed transaction protocol. IR provides fault-tolerance

without enforcing any consistency guarantees of its own. In- Application Application

stead, it allows the higher-level protocol, which we refer to Protocol Client Protocol Server

as the application protocol, to decide the outcome of con-

flicting operations and recover those decisions through IR’s InvokeInconsistent ExecInconsistent

Merge

fault-tolerant, unordered operation set. InvokeConsensus decide ExecConsensus

Sync

3.1 IR Overview

IR Client IR Replica

Application protocols invoke operations through IR in one of

two modes:

• inconsistent – operations can execute in any order. Suc- Client Node Server Node

cessful operations persist across failures. Figure 4: IR Call Flow.

• consensus – operations execute in any order, but return a

single consensus result. Successful operations and their

consensus results persist across failures.

inconsistent operations are similar to operations in weak con-

returned results (the candidate results) and returns a single re-

sistency replication protocols: they can execute in different or- sult, which IR ensures will persist as the consensus result. The

ders at each replica, and the application protocol must resolve application protocol can later recover the consensus result to

conflicts afterwards. In contrast, consensus operations allow find out its decision to conflicting operations.

the application protocol to decide the outcome of conflicts Some replicas may miss operations or need to reconcile

(by executing a decide function specified by the application their state if the consensus result chosen by the application

protocol) and recover that decision afterwards by ensuring protocol does not match their result. To ensure that IR replicas

that the chosen result persists across failures as the consensus eventually converge, they periodically synchronize. Similar

result. In this way, consensus operations can serve as the basic to eventual consistency, IR relies on the application protocol

building block for the higher-level guarantees of application to reconcile inconsistent replicas. On synchronization, a

protocols. For example, a distributed transaction protocol can single IR node first upcalls into the application protocol with

Merge, which takes records from inconsistent replicas and

decide which of two conflicting transactions will commit, and

IR will ensure that decision persists across failures. merges them into a master record of successful operations

and consensus results. Then, IR upcalls into the application

3.1.1 IR Application Protocol Interface protocol with Sync at each replica. Sync takes the master

record and reconciles application protocol state to make the

Figure 3 summarizes the IR interfaces at clients and replicas.

replica consistent with the chosen consensus results.

Application protocols invoke operations through a client-side

IR library using InvokeInconsistent and InvokeConsensus,

and then IR runs operations using the ExecInconsistent and 3.1.2 IR Guarantees

ExecConsensus upcalls at the replicas. We define a successful operation to be one that returns to

If replicas return conflicting/non-matching results for a the application protocol. The operation set of any IR group

consensus operation, IR allows the application protocol to de- includes all successful operations. We define an operation X

cide the operation’s outcome by invoking the decide function as being visible to an operation Y if one of the replicas exe-

– passed in by the application protocol to InvokeConsensus – cuting Y has previously executed X. IR ensures the following

in the client-side library. The decide function takes the list of properties for the operation set:P1. [Fault tolerance] At any time, every operation in the client application receives OK from a Lock, the result will not

operation set is in the record of at least one replica in any change. The lock server’s Merge function will not change it,

quorum of f + 1 non-failed replicas. as we will show later, and IR ensures that the OK will persist

P2. [Visibility] For any two operations in the operation set, in the record of at least one replica out of any quorum.

at least one is visible to the other.

3.2 IR Protocol

P3. [Consensus results] At any time, the result returned by

a successful consensus operation is in the record of at Figure 3 shows the IR state at the clients and replicas. Each

least one replica in any quorum. The only exception is IR client keeps an operation counter, which, combined with

if the consensus result has been explicitly modified by the client id, uniquely identifies operations. Each replica

the application protocol through Merge, after which the keeps an unordered record of executed operations and results

outcome of Merge will be recorded instead. for consensus operations. Replicas add inconsistent opera-

IR ensures guarantees are met for up to f simultaneous fail- tions to their record as TENTATIVE and then mark them as

ures out of 2 f + 1 replicas2 and any number of client failures. FINALIZED once they execute. consensus operations are first

Replicas must fail by crashing, without Byzantine behavior. marked TENTATIVE with the result of locally executing the

We assume an asynchronous network where messages can be operation, then FINALIZED once the record has the consensus

lost or delivered out of order. IR does not require synchronous result.

disk writes, ensuring guarantees are maintained even if clients IR uses four sub-protocols – operation processing, replica

or replicas lose state on failure. IR makes progress (operations recovery/synchronization, client recovery, and group member-

will eventually become successful) provided that messages ship change. Due to space constraints, we describe only the

that are repeatedly resent are eventually delivered before the first two here; the third is described in [46] and the the last is

recipients time out. identical to that of Viewstamped Replication [32].

3.1.3 Application Protocol Example: Fault-Tolerant 3.2.1 Operation Processing

Lock Server We begin by describing IR’s normal-case inconsistent opera-

As an example, we show how to build a simple lock server tion processing protocol without failures:

using IR. The lock server’s guarantee is mutual exclusion: 1. The client sends hPROPOSE, id, opi to all replicas, where

a lock cannot be held by two clients at once. We replicate id is the operation id and op is the operation.

Lock as a consensus operation and Unlock as an inconsistent 2. Each replica writes id and op to its record as TENTATIVE,

operation. A client application acquires the lock only if Lock then responds to the client with hREPLY, idi.

successfully returns OK as a consensus result. 3. Once the client receives f + 1 responses from replicas

Since operations can run in any order at the replicas, clients (retrying if necessary), it returns to the application protocol

use unique ids (e.g., a tuple of client id and a sequence num- and asynchronously sends hFINALIZE, idi to all replicas.

ber) to identify corresponding Lock and Unlock operations (FINALIZE can also be piggy-backed on the client’s next

and only call Unlock if Lock first succeeds. Replicas will message.)

therefore be able to later match up Lock and Unlock opera- 4. On FINALIZE, replicas upcall into the application protocol

tions, regardless of order, and determine the lock’s status. with ExecInconsistent(op) and mark op as FINALIZED.

Note that inconsistent operations are not commutative Due to the lack of consistency, IR can successfully complete

because they can have side-effects that affect the outcome an inconsistent operation with a single round-trip to f + 1

of consensus operations. If an Unlock and Lock execute in replicas and no coordination across replicas.

different orders at different replicas, some replicas might Next, we describe the normal-case consensus operation

have the lock free, while others might not. If replicas return processing protocol, which has both a fast path and a slow

different results to Lock, IR invokes the lock server’s decide path. IR uses the fast path when it can achieve a fast quorum

function, which returns OK if f + 1 replicas returned OK and of d 32 f e + 1 replicas that return matching results to the

NO otherwise. IR only invokes Merge and Sync on recovery,

operation. Similar to Fast Paxos and Speculative Paxos [38],

so we defer their discussion until Section 3.2.2. IR requires a fast quorum to ensure that a majority of the

IR’s guarantees ensure correctness for our lock server. replicas in any quorum agrees to the consensus result. This

P1 ensures that held locks are persistent: a Lock operation quorum size is necessary to execute operations in a single

persists at one or more replicas in any quorum. P2 ensures round trip when using a replica group of size 2 f + 1 [29];

mutual exclusion: for any two conflicting Lock operations, an alternative would be to use quorums of size 2 f + 1 in a

one is visible to the other in any quorum; therefore, IR system with 3 f + 1 replicas.

will never receive f + 1 matching OK results, precluding the When IR cannot achieve a fast quorum, either because

decide function from returning OK. P3 ensures that once the replicas did not return enough matching results (e.g., if there

are conflicting concurrent operations) or because not enough

2 Using more than 2 f + 1 replicas for f failures is possible but illogical replicas responded (e.g., if more than 2f are down), then it

because it requires a larger quorum size with no additional benefit. must take the slow path. We describe both below:1. The client sends hPROPOSE, id, opi to all replicas. 1. IR replicas send their current view number in every re-

2. Each replica calls into the application protocol with sponse to clients. For an operation to be considered suc-

ExecConsensus(op) and writes id, op, and result to its cessful, the IR client must receive responses with matching

record as TENTATIVE. The replica responds to the client view numbers. For consensus operations, the view num-

with hREPLY, id, resulti. bers in REPLY and CONFIRM must match as well. If a

3. If the client receives at least d 32 f e + 1 matching results client receives responses with different view numbers, it

(within a timeout), then it takes the fast path: the client re- notifies the replicas in the older view.

turns result to the application protocol and asynchronously 2. On receiving a message with a view number that is

sends hFINALIZE, id, resulti to all replicas. higher than its current view, a replica moves to the VIEW-

4. Otherwise, the client takes the slow path: once it re- CHANGING state and requests the master record from any

ceives f +1 responses (retrying if necessary), then it sends replica in the higher view. It replaces its own record with

hFINALIZE, id, resulti to all replicas, where result is ob- the master record and upcalls into the application protocol

tained from executing the decide function. with Sync before returning to NORMAL state.

5. On receiving FINALIZE, each replica marks the operation 3. On PROPOSE, each replica first checks whether the opera-

as FINALIZED, updating its record if the received result is tion was already FINALIZED by a view change. If so, the

different, and sends hCONFIRM, idi to the client. replica responds with hREPLY, id, FINALIZED, v, [result]i,

6. On the slow path, the client returns result to the application where v is the replica’s current view number and result is

protocol once it has received f + 1 CONFIRM responses. the consensus result for consensus operations.

The fast path for consensus operations takes a single round 4. If the client receives REPLY with a FINALIZED status

trip to d 32 f e + 1 replicas, while the slow path requires two for consensus operations, it sends hFINALIZE, id, resulti

round-trips to at least f + 1 replicas. Note that IR replicas with the received result and waits until it receives f + 1

can execute operations in different orders and still return CONFIRM responses in the same view before returning

matching responses, so IR can use the fast path without a result to the application protocol.

strict serial ordering of operations across replicas. IR can also

run the fast path and slow path in parallel as an optimization. We sketch the view change protocol here; the full descrip-

tion is available in our TR [46]. The protocol is identical to

VR, except that the leader must merge records from the latest

3.2.2 Replica Recovery and Synchronization view, rather than simply taking the longest log from the latest

IR uses a single protocol for recovering failed replicas and view, to preserve all the guarantees stated in 3.1.2. During

running periodic synchronizations. On recovery, we must synchronization, IR finalizes all TENTATIVE operations, re-

ensure that the failed replica applies all operations it may lying on the application protocol to decide any consensus

have lost or missed in the operation set, so we use the same results.

protocol to periodically bring all replicas up-to-date. Once the leader has received f + 1 records, it merges the

To handle recovery and synchronization, we introduce records from replicas in the latest view into a master record, R,

view changes into the IR protocol, similar to Viewstamped using IR - MERGE - RECORDS(records) (see Figure 5), where

Replication (VR) [37]. These maintain IR’s correctness records is the set of received records from replicas in the high-

guarantees across failures. Each IR view change is run by a est view. IR - MERGE - RECORDS starts by adding all inconsis-

leader; leaders coordinate only view changes, not operation tent operations and consensus operations marked FINALIZED

processing. During a view change, the leader has just one to R and calling Sync into the application protocol. These op-

task: to make at least f + 1 replicas up-to-date (i.e., they have erations must persist in the next view, so we first apply them to

applied all operations in the operation set) and consistent the leader, ensuring that they are visible to any operations for

with each other (i.e., they have applied the same consensus which the leader will decide consensus results next in Merge.

results). IR view changes require a leader because polling As an example, Sync for the lock server matches up all cor-

inconsistent replicas can lead to conflicting sets of operations responding Lock and Unlock by id; if there are unmatched

and consensus results. Thus, the leader must decide on a Locks, it sets locked = TRUE; otherwise, locked = FALSE.

master record that replicas can then use to synchronize with IR asks the application protocol to decide the consensus

each other. result for the remaining TENTATIVE consensus operations,

To support view changes, each IR replica maintains a which either: (1) have a matching result, which we define as

current view, which consists of the identity of the leader, a list the majority result, in at least d 2f e + 1 records or (2) do not.

of the replicas in the group, and a (monotonically increasing) IR places these operations in d and u, respectively, and calls

view number uniquely identifying the view. Each IR replica Merge(d, u) into the application protocol, which must return

can be in one of the three states: NORMAL, VIEW- CHANGING a consensus result for every operation in d and u.

or RECOVERING. Replicas process operations only in the IR must rely on the application protocol to decide consen-

NORMAL state. We make four additions to IR’s operation sus results for several reasons. For operations in d, IR cannot

processing protocol: tell whether the operation succeeded with the majority resultIR - MERGE - RECORDS (records) the protocol by starting a new view change with a larger view

1 R, d, u = 0/ number.

2 for ∀op ∈ records

3 if op. type = = inconsistent

4 R = R ∪ op 3.3 Correctness

5 elseif op. type = = consensus and op. status = = FINALIZED

6 R = R ∪ op We give a brief sketch of correctness for IR, showing why it

7 elseif op. type = = consensus and op. status = = TENTATIVE satisfies the three properties above. For a more complete proof

8 if op. result in more than 2f + 1 records and a TLA+ specification [26], see our technical report [46].

9 d = d ∪ op We first show that all three properties hold in the absence

10 else

11 u = u ∪ op of failures and synchronization. Define the set of persistent

12 Sync(R) operations to be those operations in the record of at least one

13 return R ∪ Merge(d, u) replica in any quorum of f + 1 non-failed replicas. P1 states

that every operation that succeeded is persistent; this is true

Figure 5: Merge function for the master record. We merge all records

by quorum intersection because an operation only succeeds

from replicas in the latest view, which is always a strict super set of

the records from replicas in lower views.

once responses are received from f + 1 of 2 f + 1 replicas.

For P2, consider any two successful consensus operations

X and Y . Each received candidate results from a quorum

on the fast path, or whether it took the slow path and the appli- of f + 1 replicas that executed the request. By quorum

cation protocol decide’d a different result that was later lost. intersection, there must be one replica that executed both

In some cases, it is not safe for IR to keep the majority result X and Y ; assume without loss of generality that it executed X

because it would violate application protocol invariants. For first. Then its candidate result for Y reflects the effects of X,

example, in the lock server, OK could be the majority result if and X is visible to Y .

only d 2f e + 1 replicas replied OK, but the other replicas might Finally, for P3, a successful consensus operation result was

have accepted a conflicting lock request. However, it is also obtained either on the fast path, in which case a fast quorum

possible that the other replicas did respond OK, in which case of replicas has the same result marked as TENTATIVE in their

OK would have been a successful response on the fast-path. records, or on the slow path, where f + 1 replicas have the

The need to resolve this ambiguity is the reason for the result marked as FINALIZED in their record. In both cases, at

caveat in IR’s consensus property (P3) that consensus results least one replica in every quorum will have that result.

can be changed in Merge. Fortunately, the application protocol Since replicas can lose records on failures and must per-

can ensure that successful consensus results do not change form periodic synchronizations, we must also prove that the

in Merge, simply by maintaining the majority results in d on synchronization/recovery protocol maintains these properties.

Merge unless they violate invariants. The merge function for On synchronization or recovery, the protocol ensures that all

the lock server, therefore, does not change a majority response persistent operations from the previous view are persistent in

of OK, unless another client holds the lock. In that case, the the new view. The leader of the new view merges the record

operation in d could not have returned a successful consensus of replicas in the highest view from f + 1 responses. Any

result to the client (either through the fast or the slow path), persistent operation appears in one of these records, and the

so it is safe to change its result. merge procedure ensures it is retained in the master record. It

For operations in u, IR needs to invoke decide but cannot is sufficient to only merge records from replicas in the highest

without at least f + 1 results, so uses Merge instead. The because, similar to VR, IR’s view change protocol ensures

application protocol can decide consensus results in Merge that no replicas that participated in the view change will move

without f + 1 replica results and still preserve IR’s visibility to a lower view, thus no operations will become persistent in

property because IR has already applied all of the operations lower views.

in R and d, which are the only operations definitely in the The view change completes by synchronizing at least f +1

operation set, at this point. replicas with the master record, ensuring P1 continues to

The leader adds all operations returned from Merge and hold. This also maintains property P3: a consensus operation

their consensus results to R, then sends R to the other replicas, that took the slow path will appear as FINALIZED in at least

which call Sync(R) into the application protocol and replace one record, and one that took the fast path will appear as

f

their own records with R. The view change is complete TENTATIVE in at least d 2 e + 1 records. IR’s merge procedure

after at least f + 1 replicas have exchanged and merged ensures that the results of these operations are maintained,

records and SYNC’d with the master record. A replica can unless the application protocol chooses to change them in

only process requests in the new view (in the NORMAL state) its Merge function. Once the operation is FINALIZED at f + 1

after it completes the view change protocol. At this point, any replicas (by a successful view-change or by a client), the pro-

recovering replicas can also be considered recovered. If the tocol ensures that the consensus result won’t be changed and

leader of the view change does not finish the view change by will persist: the operation will always appear as FINALIZED

some timeout, the group will elect a new leader to complete when constructing any subsequent master records and thusthe merging procedure will always Sync it. Finally, P2 is committed transaction, so consensus operations suffice to en-

maintained during the view change because the leader first sure that at least one replica sees any conflicting transaction

calls Sync with all previously successful operations before and aborts the transaction being checked.

calling Merge, thus the previously successful operations will

4.2 IR Application Protocol Requirement: Application

be visible to any operations that the leader finalizes during the

view change. The view change then ensures that any finalized protocols must be able to change consensus operation

operation will continue to be finalized in the record of at least results.

f + 1 replicas, and thus be visible to subsequent successful Inconsistent replicas could execute consensus operations with

operations. one result and later find the group agreed to a different

consensus result. For example, if the group in our lock server

4. Building Atop IR agrees to reject a Lock operation that one replica accepted,

the replica must later free the lock, and vice versa. As noted

IR obtains performance benefits because it offers weak con- above, the group as a whole continues to enforce mutual

sistency guarantees and relies on application protocols to exclusion, so these temporary inconsistencies are tolerable

resolve inconsistencies, similar to eventual consistency proto- and are always resolved by the end of synchronization.

cols such as Dynamo [15] and Bayou [43]. However, unlike In TAPIR, we take the same approach with distributed

eventual consistency systems, which expect applications to transaction protocols. 2PC-based protocols are always pre-

resolve conflicts after they happen, IR allows application pro- pared to abort transactions, so they can easily accommodate

tocols to prevent conflicts before they happen. Using consen- a Prepare result changing from PREPARE - OK to ABORT. If

sus operations, application protocols can enforce higher-level ABORT changes to PREPARE - OK , it might temporarily cause a

guarantees (e.g., TAPIR’s linearizable transaction ordering) conflict at the replica, which can be correctly resolved because

across replicas despite IR’s weak consistency. the group as a whole could not have agreed to PREPARE - OK

However, building strong guarantees on IR requires care- for two conflicting transactions.

ful application protocol design. IR cannot support certain Changing Prepare results does sometimes cause unneces-

application protocol invariants. Moreover, if misapplied, IR sary aborts. To reduce these, TAPIR introduces two Prepare

can even provide applications with worse performance than a results in addition to PREPARE - OK and ABORT: ABSTAIN

strongly consistent replication protocol. In this section, we and RETRY. ABSTAIN helps TAPIR distinguish between con-

discuss the properties that application protocols need to have flicts with committed transactions, which will not abort, and

to correctly and efficiently enforce higher-level guarantees conflicts with prepared transactions, which may later abort.

with IR and TAPIR’s techniques for efficiently providing Replicas return RETRY if the transaction has a chance of

linearizable transactions. committing later. The client can retry the Prepare without

re-executing the transaction.

4.1 IR Application Protocol Requirement: Invariant

checks must be performed pairwise. 4.3 IR Performance Principle: Application protocols

Application protocols can enforce certain types of invariants should not expect operations to execute in the same

with IR, but not others. IR guarantees that in any pair of con- order.

sensus operations, at least one will be visible to the other To efficiently achieve agreement on consensus results, appli-

(P2). Thus, IR readily supports invariants that can be safely cation protocols should not rely on operation ordering for

checked by examining pairs of operations for conflicts. For application ordering. For example, many transaction proto-

example, our lock server example can enforce mutual exclu- cols [4, 19, 22] use Paxos operation ordering to determine

sion. However, application protocols cannot check invariants transaction ordering. They would perform worse with IR

that require the entire history, because each IR replica may because replicas are unlikely to agree on which transaction

have an incomplete history of operations. For example, track- should be next in the transaction ordering.

ing bank account balances and allowing withdrawals only In TAPIR, we use optimistic timestamp ordering to ensure

if the balance remains positive is problematic because the that replicas agree on a single transaction ordering despite

invariant check must consider the entire history of deposits executing operations in different orders. Like Spanner [13],

and withdrawals. every committed transaction has a timestamp, and committed

Despite this seemingly restrictive limitation, application transaction timestamps reflect a linearizable ordering. How-

protocols can still use IR to enforce useful invariants, includ- ever, TAPIR clients, not servers, propose a timestamp for

ing lock-based concurrency control, like Strict Two-Phase their transaction; thus, if TAPIR replicas agree to commit

Locking (S2PL). As a result, distributed transaction protocols a transaction, they have all agreed to the same transaction

like Spanner [13] or Replicated Commit [34] would work ordering.

with IR. IR can also support optimistic concurrency control TAPIR replicas use these timestamps to order their trans-

(OCC) [23] because OCC checks are pairwise as well: each action logs and multi-versioned stores. Therefore, replicas

committing transaction is checked against every previously can execute Commit in different orders but still converge tothe same application state. TAPIR leverages loosely synchro- Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3

Client Shard Shard Shard Shard Shard Shard Shard Shard Shard

nized clocks at the clients for picking transaction timestamps, A B C A B C A B C

which improves performance but is not necessary for correct- BEGIN

BEGIN

ness.

execution

READ(a)

WRITE(b)

4.4 IR Performance Principle: Application protocols

READ(c)

should use cheaper inconsistent operations whenever

possible rather than consensus operations. PREPARE(A)

By concentrating invariant checks in a few operations, applica-

prepare

PREPARE(B)

tion protocols can reduce consensus operations and improve

PREPARE(C)

their performance. For example, in a transaction protocol,

any operation that decides transaction ordering must be a

consensus operation to ensure that replicas agree to the same

transaction ordering. For locking-based transaction protocols, COMMIT(A)

commit

this is any operation that acquires a lock. Thus, every Read COMMIT(B)

and Write must be replicated as a consensus operation.

COMMIT(C)

TAPIR improves on this by using optimistic transaction

ordering and OCC, which reduces consensus operations by

concentrating all ordering decisions into a single set of vali-

dation checks at the proposed transaction timestamp. These Figure 6: Example read-write transaction in TAPIR. TAPIR executes

checks execute in Prepare, which is TAPIR’s only consen- the same transaction pictured in Figure 2 with less redundant

coordination. Reads go to the closest replica and Prepare takes a

sus operation. Commit and Abort are inconsistent operations,

single round-trip to all replicas in all shards.

while Read and Write are not replicated.

5. TAPIR

the application protocol for IR; applications using TAPIR do

This section details TAPIR – the Transactional Application

not interact with IR directly.

Protocol for Inconsistent Replication. As noted, TAPIR is

A TAPIR application Begins a transaction, then executes

designed to efficiently leverage IR’s weak guarantees to

Reads and Writes during the transaction’s execution period.

provide high-performance linearizable transactions. Using

During this period, the application can Abort the transaction.

IR, TAPIR can order a transaction in a single round-trip to

Once it finishes execution, the application Commits the trans-

all replicas in all participant shards without any centralized

action. Once the application calls Commit, it can no longer

coordination.

abort the transaction. The 2PC protocol will run to comple-

TAPIR is designed to be layered atop IR in a replicated,

tion, committing or aborting the transaction based entirely

transactional storage system. Together, TAPIR and IR elim-

on the decision of the participants. As a result, TAPIR’s 2PC

inate the redundancy in the replicated transactional system,

coordinators cannot make commit or abort decisions and do

as shown in Figure 2. As a comparison, Figure 6 shows the

not have to be fault-tolerant. This property allows TAPIR to

coordination required for the same read-write transaction in

use clients as 2PC coordinators, as in MDCC [22], to reduce

TAPIR with the following benefits: (1) TAPIR does not have

the number of round-trips to storage servers.

any leaders or centralized coordination, (2) TAPIR Reads al-

TAPIR provides the traditional ACID guarantees with the

ways go to the closest replica, and (3) TAPIR Commit takes a

strictest level of isolation: strict serializability (or linearizabil-

single round-trip to the participants in the common case.

ity) of committed transactions.

5.1 Overview

TAPIR is designed to provide distributed transactions for 5.2 Protocol

a scalable storage architecture. This architecture partitions TAPIR provides transaction guarantees using a transaction

data into shards and replicates each shard across a set of processing protocol, IR functions, and a coordinator recovery

storage servers for availability and fault tolerance. Clients protocol.

are front-end application servers, located in the same or Figure 7 shows TAPIR’s interfaces and state at clients and

another datacenter as the storage servers, not end-hosts or replicas. Replicas keep committed and aborted transactions

user machines. They have access to a directory of storage in a transaction log in timestamp order; they also maintain a

servers using a service like Chubby [8] or ZooKeeper [20] and multi-versioned data store, where each version of an object is

directly map data to servers using a technique like consistent identified by the timestamp of the transaction that wrote the

hashing [21]. version. TAPIR replicas serve reads from the versioned data

TAPIR provides a general storage and transaction interface store and maintain the transaction log for synchronization and

for applications via a client-side library. Note that TAPIR is checkpointing. Like other 2PC-based protocols, each TAPIRClient Interface TAPIR - OCC - CHECK (txn,timestamp)

Begin() Read(key)→object Abort()

1 for ∀key, version ∈ txn. read-set

Commit()→TRUE / FALSE Write(key,object)

2 if version < store[key]. latest-version

Client State 3 return ABORT

• client id - unique client identifier 4 elseif version < MIN(prepared-writes[key])

• transaction - ongoing transaction id, read set, write set 5 return ABSTAIN

6 for ∀key ∈ txn. write-set

Replica Interface 7 if timestamp < MAX(PREPARED - READS(key))

Read(key)→object,version Commit(txn,timestamp) 8 return RETRY, MAX(PREPARED - READS(key))

Abort(txn,timestamp) 9 elseif timestamp < store[key]. latestVersion

Prepare(txn,timestamp)→PREPARE - OK/ABSTAIN/ABORT/(RETRY, t) 10 return RETRY, store[key]. latestVersion

Replica State 11 prepared-list[txn. id] = timestamp

• prepared list - list of transactions replica is prepared to commit 12 return PREPARE - OK

• transaction log - log of committed and aborted transactions

• store - versioned data store Figure 8: Validation function for checking for OCC conflicts on

Prepare. PREPARED - READS and PREPARED - WRITES get the pro-

Figure 7: Summary of TAPIR interfaces and client and replica state. posed timestamps for all transactions that the replica has prepared

and read or write to key, respectively.

replica also maintains a prepared list of transactions that it

has agreed to commit. 3. Each TAPIR replica that receives Prepare (invoked by IR

Each TAPIR client supports one ongoing transaction at a through ExecConcensus) first checks its transaction log for

time. In addition to its client id, the client stores the state for txn.id. If found, it returns PREPARE - OK if the transaction

the ongoing transaction, including the transaction id and read committed or ABORT if the transaction aborted.

and write sets. The transaction id must be unique, so the client 4. Otherwise, the replica checks if txn.id is already in its

uses a tuple of its client id and transaction counter, similar prepared list. If found, it returns PREPARE - OK.

to IR. TAPIR does not require synchronous disk writes at the 5. Otherwise, the replica runs TAPIR’s OCC validation

client or the replicas, as clients do not have to be fault-tolerant checks, which check for conflicts with the transaction’s

and replicas use IR. read and write sets at timestamp, shown in Figure 8.

6. Once the TAPIR client receives results from all shards, the

5.2.1 Transaction Processing client sends Commit(txn, timestamp) if all shards replied

We begin with TAPIR’s protocol for executing transactions. PREPARE - OK or Abort(txn, timestamp) if any shards

1. For Write(key, object), the client buffers key and object in replied ABORT or ABSTAIN. If any shards replied RETRY,

the write set until commit and returns immediately. then the client retries with a new proposed timestamp (up

2. For Read(key), if key is in the transaction’s write set, the to a set limit of retries).

client returns object from the write set. If the transaction 7. On receiving a Commit, the TAPIR replica: (1) commits the

has already read key, it returns a cached copy. Otherwise, transaction to its transaction log, (2) updates its versioned

the client sends Read(key) to the replica. store with w, (3) removes the transaction from its prepared

3. On receiving Read, the replica returns object and version, list (if it is there), and (4) responds to the client.

where object is the latest version of key and version is the 8. On receiving a Abort, the TAPIR replica: (1) logs the

timestamp of the transaction that wrote that version. abort, (2) removes the transaction from its prepared list (if

4. On response, the client puts (key, version) into the transac- it is there), and (3) responds to the client.

tion’s read set and returns object to the application. Like other 2PC-based protocols, TAPIR can return the out-

Once the application calls Commit or Abort, the execution come of the transaction to the application as soon as Prepare

phase finishes. To commit, the TAPIR client coordinates returns from all shards (in Step 6) and send the Commit op-

across all participants – the shards that are responsible for erations asynchronously. As a result, using IR, TAPIR can

the keys in the read or write set – to find a single timestamp, commit a transaction with a single round-trip to all replicas

consistent with the strict serial order of transactions, to assign in all shards.

the transaction’s reads and writes, as follows:

1. The TAPIR client selects a proposed timestamp. Proposed 5.2.2 IR Support

timestamps must be unique, so clients use a tuple of their Because TAPIR’s Prepare is an IR consensus operation,

local time and their client id. TAPIR must implement a client-side decide function, shown

2. The TAPIR client invokes Prepare(txn, timestamp) as an in Figure 9, which merges inconsistent Prepare results from

IR consensus operation, where timestamp is the proposed replicas in a shard into a single result. TAPIR - DECIDE is

timestamp and txn includes the transaction id (txn.id) simple: if a majority of the replicas replied PREPARE - OK,

and the transaction read (txn.read set) and write sets then it commits the transaction. This is safe because no

(txn.write set). The client invokes Prepare on all partici- conflicting transaction could also get a majority of the replicas

pants through IR as a consensus operations. to return PREPARE - OK.TAPIR - DECIDE(results) now consistent with f + 1 replicas, so it can make decisions

1 if ABORT ∈ results on consensus result for the majority.

2 return ABORT TAPIR’s sync function (full description in [46]) runs at

3 if count(PREPARE - OK, results) ≥ f + 1 the other replicas to reconcile TAPIR state with the master

4 return PREPARE - OK

5 if count(ABSTAIN, results) ≥ f + 1

records, correcting missed operations or consensus results

6 return ABORT where the replica did not agree with the group. It simply

7 if RETRY ∈ results applies operations and consensus results to the replica’s

8 return RETRY, max(results.retry-timestamp) state: it logs aborts and commits, and prepares uncommitted

9 return ABORT

transactions where the group responded PREPARE - OK.

Figure 9: TAPIR’s decide function. IR runs this if replicas return

different results on Prepare. 5.2.3 Coordinator Recovery

If a client fails while in the process of committing a transac-

tion, TAPIR ensures that the transaction runs to completion

TAPIR - MERGE (d, u) (either commits or aborts). Further, the client may have re-

1 for ∀op ∈ d ∪ u turned the commit or abort to the application, so we must

2 txn = op. args. txn ensure that the client’s commit decision is preserved. For

3 if txn. id ∈ prepared-list

4 DELETE(prepared-list,txn. id)

this purpose, TAPIR uses the cooperative termination pro-

5 for op ∈ d tocol defined by Bernstein [6] for coordinator recovery and

6 txn = op. args. txn used by MDCC [22]. TAPIR designates one of the participant

7 timestamp = op. args. timestamp shards as a backup shard, the replicas in which can serve as a

8 if txn. id 6∈ txn-log and op. result = = PREPARE - OK

9 R[op]. result = TAPIR - OCC - CHECK(txn,timestamp) backup coordinator if the client fails. As observed by MDCC,

10 else because coordinators cannot unilaterally abort transactions

11 R[op]. result = op. result (i.e., if a client receives f + 1 PREPARE - OK responses from

12 for op ∈ u

each participant, it must commit the transaction), a backup

13 txn = op. args. txn

14 timestamp = op. args. timestamp coordinator can safely complete the protocol without block-

15 R[op]. result = TAPIR - OCC - CHECK(txn,timestamp) ing. However, we must ensure that no two coordinators for a

16 return R transaction are active at the same time.

To do so, when a replica in the backup shard notices a

Figure 10: TAPIR’s merge function. IR runs this function at the

leader on synchronization and recovery.

coordinator failure, it initiates a Paxos round to elect itself

as the new backup coordinator. This replica acts as the pro-

poser; the acceptors are the replicas in the backup shard, and

the learners are the participants in the transaction. Once this

TAPIR also supports Merge, shown in Figure 10, and

Paxos round finishes, the participants will only respond to

Sync at replicas. TAPIR - MERGE first removes any prepared

Prepare, Commit, or Abort from the new coordinator, ignoring

transactions from the leader where the Prepare operation is

messages from any other. Thus, the new backup coordinator

TENTATIVE . This step removes any inconsistencies that the

prevents the original coordinator and any previous backup co-

leader may have because it executed a Prepare differently –

ordinators from subsequently making a commit decision. The

out-of-order or missed – by the rest of the group.

complete protocol is described in our technical report [46].

The next step checks d for any PREPARE - OK results that

might have succeeded on the IR fast path and need to be

preserved. If the transaction has not committed or aborted 5.3 Correctness

already, we re-run TAPIR - OCC - CHECK to check for conflicts To prove correctness, we show that TAPIR maintains the

with other previously prepared or committed transactions. If following properties3 given up to f failures in each replica

the transaction conflicts, then we know that its PREPARE - OK group and any number of client failures:

did not succeed at a fast quorum, so we can change it to • Isolation. There exists a global linearizable ordering of

ABORT ; otherwise, for correctness, we must preserve the committed transactions.

PREPARE - OK because TAPIR may have moved on to the • Atomicity. If a transaction commits at any participating

commit phase of 2PC. Further, we know that it is safe to pre- shard, it commits at them all.

serve these PREPARE - OK results because, if they conflicted • Durability. Committed transactions stay committed,

with another transaction, the conflicting transaction must have maintaining the original linearizable order.

gotten its consensus result on the IR slow path, so if TAPIR - We give a brief sketch of how these properties are maintained

OCC - CHECK did not find a conflict, then the conflicting trans- despite failures. Our technical report [46] contains a more

action’s Prepare must not have succeeded.

Finally, for the operations in u, we simply decide a result 3 We do not prove database consistency, as it depends on application invari-

for each operation and preserve it. We know that the leader is ants; however, strict serializability is sufficient to enforce consistency.complete proof, as well as a machine-checked TLA+ [26] and optimizations to support environments with high clock

specification for TAPIR. skew, to reduce the quorum size when durable storage is

available, and to accept more transactions out of order by

5.3.1 Isolation relaxing TAPIR’s guarantees to non-strict serializability.

We execute Prepare through IR as a consensus opera-

tion. IR’s visibility property guarantees that, given any two 6. Evaluation

Prepare operations for conflicting transactions, at least one

In this section, our experiments demonstrate the following:

must execute before the second at a common replica. The sec-

• TAPIR provides better latency and throughput than con-

ond Prepare would not return PREPARE - OK from its TAPIR -

ventional transaction protocols in both the datacenter and

OCC - CHECK : IR will not achieve a fast quorum of matching

wide-area environments.

PREPARE - OK responses, and TAPIR - DECIDE will not receive

• TAPIR’s abort rate scales similarly to other OCC-based

enough PREPARE - OK responses to return PREPARE - OK be-

transaction protocols as contention increases.

cause it requires at least f + 1 matching PREPARE - OK. Thus,

• Clock synchronization sufficient for TAPIR’s needs is

one of the two transactions will abort. IR ensures that the

widely available in both datacenter and wide-area environ-

non-PREPARE - OK result will persist as long as TAPIR does

ments.

not change the result in Merge (P3). TAPIR - MERGE never

• TAPIR provides performance comparable to systems with

changes a result that is not PREPARE - OK to PREPARE - OK,

weak consistency guarantees and no transactions.

ensuring the unsuccessful transaction will never be able to

succeed. 6.1 Experimental Setup

5.3.2 Atomicity We ran our experiments on Google Compute Engine [18]

If a transaction commits at any participating shard, the TAPIR (GCE) with VMs spread across 3 geographical regions – US,

client must have received a successful PREPARE - OK from Europe and Asia – and placed in different availability zones

every participating shard on Prepare. Barring failures, it will within each geographical region. Each server has a virtualized,

ensure that Commit eventually executes successfully at every single core 2.6 GHz Intel Xeon, 8 GB of RAM and 1 Gb NIC.

participant. TAPIR replicas always execute Commit, even if

6.1.1 Testbed Measurements

they did not prepare the transaction, so Commit will eventually

commit the transaction at every participant if it executes at As TAPIR’s performance depends on clock synchronization

one participant. and round-trip times, we first present latency and clock skew

If the coordinator fails and the transaction has already com- measurements of our test environment. As clock skew in-

mitted at a shard, the backup coordinator will see the commit creases, TAPIR’s latency increases and throughput decreases

during the polling phase of the cooperative termination proto- because clients may have to retry more Prepare operations. It

col and ensure that Commit eventually executes successfully is important to note that TAPIR’s performance depends on the

at the other shards. If no shard has executed Commit yet, the actual clock skew, not a worst-case bound like Spanner [13].

Paxos round will ensure that all participants stop responding We measured the clock skew by sending a ping message

to the original coordinator and take their commit decision with timestamps taken on either end. We calculate skew

from the new backup coordinator. By induction, if the new by comparing the timestamp taken at the destination to

backup coordinator sends Commit to any shard, it, or another the one taken at the source plus half the round-trip time

backup coordinator, will see it and ensure that Commit even- (assuming that network latency is symmetric). The average

tually executes at all participants. RTT between US-Europe was 110 ms; US-Asia was 165 ms;

Europe-Asia was 260 ms. We found the clock skew to be

5.3.3 Durability low, averaging between 0.1 ms and 3.4 ms, demonstrating the

For all committed transactions, either the client or a backup feasibility of synchronizing clocks in the wide area. However,

coordinator will eventually execute Commit successfully as an there was a long tail to the clock skew, with the worst case

IR inconsistent operation. IR guarantees that the Commit will clock skew being around 27 ms – making it significant that

never be lost (P1) and every replica will eventually execute or TAPIR’s performance depends on actual rather than worst-

synchronize it. On Commit, TAPIR replicas use the transaction case clock skew. As our measurements show, the skew in this

timestamp included in Commit to order the transaction in their environment is low enough to achieve good performance.

log, regardless of when they execute it, thus maintaining the

original linearizable ordering. 6.1.2 Implementation

We implemented TAPIR in a transactional key-value storage

5.4 TAPIR Extensions system, called TAPIR - KV. Our prototype consists of 9094

The extended version of this paper [46] describes a number of lines of C++ code, not including the testing framework.

extensions to the TAPIR protocol. These include a protocol We also built two comparison systems. The first, OCC -

for globally-consistent read-only transactions at a timestamp, STORE , is a “standard” implementation of 2PC and OCC,You can also read