Automation and in Sub-Saharan Africa the Future of Work - GPPi

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Automation and

the Future of Work

in Sub-Saharan Africa

By Alexander Gaus and Wade Hoxtell

www.kas.deImpressum Acknowledgments This discussion paper was made possible through the generous financial support of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. In particular, we would like to thank Winfried Weck and Martina Kaiser, both from the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung in Berlin, for their support during the writ- ing of this paper. The authors would also like to acknowledge the expertise, knowledge, and support from the following people during the research, writing, and review processes of this discussion paper: Fisayo Alo, Nishani Chankar, Mirko Hohmann, Nico Landman, Dr Jamal Msami, Benjamin Rosman, Sofia Schappert, Martin Sprott, Anna Wasserfall, Dr Clara Weinhardt, and Sebastian Weise. Shazia Amin edited the paper. Any errors are solely the responsibility of the authors. Contact the authors: Dr Alexander Gaus, agaus@gppi.net Global Public Policy Institute Wade Hoxtell, whoxtell@gppi.net Reinhardtstr. 7, 10117 Berlin, Germany Contact the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung: Martina Kaiser, martina.kaiser@kas.de Published by: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V. 2019, Sankt Augustin and Berlin, Germany Cover page image: © louis-reed, nesa-by-makers/unsplash Images: S. 4 © anandaBGD/istock by getty images; S. 8 © JohnnyGreig/istock by getty images; S. 22 © chuttersnap/unsplash; S. 34 © skynesher/istock by getty images; S. 48 © subman/istock by getty images; 56 © Ivan Bandur/unsplash Design and typesetting: yellow too Pasiek Horntrich GbR The print edition of this publication was climate-neutrally printed by Kern GmbH, Bex- bach, on FSC certified paper. Printed in Germany. Printed with financial support from the German Federal Government. This publication is published under a Creative Commons license: “Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 international” (CC BY-SA 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode ISBN 978-3-95721-530-7

Table of contents

1. Introduction 5

2. What is Automation and How Widespread Is It? 9

Automation in different sectors 11

Status of the debate: The optimists vs. the skeptics 15

3. Analytical Framework: Factors Driving or Inhibiting Automation 23

Social structure 25

The regulatory landscape 26

Availability of infrastructure and capital 28

Economic viability of automation 29

4. Automation in Sub-Saharan Africa 35

Social structure: Population growth and

education levels at odds for automation uptake 35

Regulatory landscape: Competing effects from

labor market regulation and industrial policies 38

Infrastructure and capital:

Widely lacking and heavily constraining automation uptake 40

Economic viability: Automation only viable for some 43

5. Outlook 49

Limited impact (for now) on those working in agriculture 50

Limited impact on unskilled workers and informal employment 51

Strong impact on high-wage manufacturing and services 52

6. Conclusion 57

Author Profiles 60

31. Introduction

Many industrialized economies are being The purpose of this discussion paper is

transformed by the increasing automa- not to argue that either of these two per-

tion of work. Self-driving cars upend- spectives is the correct one, nor is it to

ing the taxi and trucking industries will downplay the potential significant ben

be one of the most visible signs of these efits of the fourth industrial revolution,

changes in the near future, but these but rather to direct attention toward those

transformations will go beyond the trans- particular factors that influence the uptake

portation sector. With ongoing and con- of automation technologies. In doing so,

tinuous technological advancements, a this paper calls into question the common

number of countries are entering “the assumption that what may be possible

second machine age” or, as the World technically will materialize inevitably in

Economic Forum (WEF) has labeled it, the practice. There is a tendency in the current

“fourth industrial revolution.”1 Regardless discourse on automation and the future

of monikers, an era characterized by a of work to presuppose that impressive

rise of autonomous robots and self-learn- advances in hardware and software mean

ing software is upon us. The direct or indi- that widespread automation – and its con-

rect impact of these transformations on sequences – are inevitable.

industrial societies, emerging economies,

and developing countries is already quite Further, research findings on automa-

profound and will only expand over time. tion rise to prominence when calculations

on what percentage of labor in particular

Yet, predictions vary on what automa- sectors could be replaced through auto-

tion will eventually mean for the future mation are turned into striking headlines

of work. On the one hand, experts claim in the popular media about jobs that will

that automation will lead to greater effi- be replaced. The research on, and media

ciency and productivity, while also freeing exposure of, the potential for job dis-

humans from unsafe or unpopular tasks. placements due to automation are impor-

They point to the evidence of history tant for drawing attention to the issues

where technological innovation has led and presenting potential scenarios of the

to the creation of entirely new economic future. However, these estimates are not

sectors and ultimately to new jobs. On the particularly helpful for understanding the

other hand, some experts argue that the phenomenon of automation or, more

application of rapidly advancing automa- importantly, as guidance on how to react.

tion technology across numerous sec- As such, a more critical look at the drivers

tors simultaneously will lead to unfavora- and inhibitors underlying the automation

ble consequences, including widespread revolution is needed. Just as technology in

unemployment, greater wealth inequality, general is not deterministic of the future,

and social unrest. advancements in robots and algorithms

are not the sole drivers of automation.

5Automation and the Future of Work in Sub-Saharan Africa

History shows that a range of factors what extent these factors are driving or

determine the uptake of new technolo- inhibiting automation and the future of

gies and innovations across countries and work in Sub-Saharan Africa (Chapter 4).

sectors, such as public sentiments toward Using this approach, the paper concludes

such innovations, availability of labor with that wide-scale automation in most areas

needed skills, the regulations and policies of the region’s economies will be limited

at play, the availability of necessary infra- (Chapter 5). This is largely true because of

structure and capital, as well as the eco- the area’s large-scale informal economy,

nomic viability of developing and imple- and its lack of necessary digital infrastruc-

menting these technologies. ture, available capital, and forward-looking

industrial policies. In addition, the low pay

This discussion paper aims to contrib- and total cost for hiring the majority of

ute to a growing body of research on the Sub-Saharan African workers will remain

potential impact of automation on Sub- cheaper than the total cost of implement-

Saharan African economies, as well as to ing automation technology. Further, given

help frame future debates on the topic. In the high percentage of workers currently

this respect, the primary audience for this making a living in the informal economy

paper is the Sub-Saharan African policy and particularly in small-scale farming –

community, (international) development sectors that are especially immune to

practitioners, and researchers, rather automation in pre-industrialized societies –

than the experts in automation technolo- the impact will be even more limited.

gies. It is also important to note that the

approach taken in this paper does have Yet, Sub-Saharan Africa does have areas

limitations: the paper takes a birds-eye of economic activity where digital infra-

view of developments in automation structure is highly developed, where capi-

technologies and of the factors that may, tal is available, and where the economic

or may not, lead to their implementa- calculus favors automation. In Sub-Saha-

tion in different contexts. In addition, it is ran Africa’s high-wage and internation-

beyond the scope of this paper to dive too alized manufacturing sector and in its

deeply into the economic, social, regula- high-wage service economy, for example,

tory, or infrastructural particularities of increasing usage of automation tech-

each country in the region. The analytical nology is likely. In such a scenario, the

framework is broadly defined and, conse- expansion of automation technology will

quently, the paper can only draw broad strongly affect Sub-Saharan Africa’s grow-

conclusions using specific country or sec- ing middle class who are employed in the

toral examples. Ultimately, the goal of this formal economy. For them, hard times

paper is to spark discussion and to inspire are likely coming sooner rather than later.

more rigorous research into these areas.

Beyond an initial review of the basic tenets 1 Brynjolfsson, Erik; McAfee, Andrew (2015):

of automation (Chapter 2) and the factors The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and

Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies.

influencing technological uptake (Chap- (New York: W. W. Norton & Company).

ter 3), this discussion paper analyzes to

62. What is Automation

and How Widespread Is It?

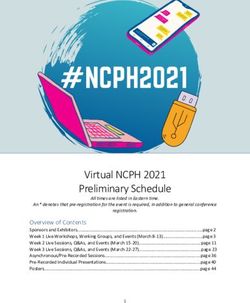

Artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, Rapid developments in automation have

predictive analytics, robots, cobots, and come about through the convergence of

robotic process automation are all terms technological advancements in the areas

that are often (mistakenly) used inter- of computing power, cloud computing,

changeably when discussing automation. and artificial intelligence on the software

Given the plethora of technical terms for side, coupled with energy storage, sensor

automation – not to mention the spectrum technology, actuators, and flexible object

of terms and concepts related to the fourth handling on the hardware side (Figure 1).

industrial revolution – it is worth breaking Each of these areas has seen significant

down what exactly is meant by automation developments over the past years, and

combinations therein have sparked true

Automation is technology that assists innovation in the automation industry.

humans, with limited guidance, in the

production, maintenance, or delivery of Figure 1: Technological components

products or services, or autonomously of the automation revolution

produces, maintains, or delivers those

products or services.1 This definition

encompasses a large number of applica- Computing

tions, from physical robots programmed power/cloud

computing

to do manual tasks – for example, mov-

ing an object from point A to point B,

to software applications – for example,

cloud-based computer software capa- Artificial Sensor

int./machine technology

ble of complex cognitive tasks, such as

learning

processing files, recognizing and analyz-

ing images, or translating a sentence into

multiple languages. There are many more

applications in between these with vary-

Robotics

ing degrees of complexity, requiring more

or less dexterity and/or computer power.

The critical aspect of this definition is that

automation technology works without

continuous human guidance because it First, advancements in computing hard-

is preprogrammed or because it is a self- ware, in particular the growth of process-

learning system capable of making deci- ing power, enable computers to conduct

sions without human interference. increasingly complex computational tasks.

9Automation and the Future of Work in Sub-Saharan Africa

In what has proved to be remarkable fore- basic tenet of machine learning, a key

sight, Gordon Moore predicted in 1965 factor for achieving higher degrees of

that computer processing power would artificial intelligence, is to use algorithms

double every 18 months – a trend that to enable programs to learn from data

has roughly held true to the present day. analysis, as opposed to direct instructions

The result of this growing computational from a programmer. As such, machine

power has been an astounding integra- learning enables programs to react to

tion of computers, in particular smart- non-standardized situations based on

phones, into many aspects of our daily previous experiences and to conduct self-

lives. While Moore’s Law may be breaking optimizing assessments of its own activi-

down as space to store more transistors ties.4 In this respect, a key future potential

on a microchip runs out, technologies will of machine learning is to give computers

nevertheless advance – even if they do the capability of performing tasks tradi-

so more gradually. For example, we will tionally perceived to require human intel-

increasingly be able to leverage process- ligence. Some of the better-known recent

ing power more efficiently, and potentially breakthroughs in AlphaGo or poker AIs,

groundbreaking ideas such as “chiplets” as well as advanced image or pattern rec-

(the three-dimensionalization of chip engi- ognition, point to the rapid developments

neering) will open up even more possibili- in machine learning.5

ties for the replacement of human think-

ing with machine processing.2 Third, advancements in sensor technol-

ogy are giving robots much more accu-

At the same time, the development of rate “eyes,” “ears,” and “touch” capabili-

more advanced fiber optics and mobile ties. Autonomous systems, and robots in

data transmission, such as 4G and now particular, require sensing technology to

5G technology, together with vast improve evaluate their environment and to han-

ments in internet access and bandwidth, dle objects precisely. Sensor technology

have allowed greater connectivity as well assessing light, distance, sound, contact,

as the storage and sharing of information pressure, proximity, and weight, as well

across the globe through cloud comput- as sensors to determine the position of

ing. This has already had a considerable a robot, are critical components. While

impact, from how multinational compa- such sensor technology exists already, we

nies organize their human resources and are seeing a new wave of developments,

customer relations to how small non- such as soft robotics sensing, increasing

profits communicate and share financial miniaturization, higher accuracy, better

transactions with their tax advisers.3 energy efficiency, and substantially lower

costs.6 These continuous improvements

Second, advances in artificial intelligence open up numerous new opportunities for

increasingly allow computers to conduct autonomously operating systems to con-

non-routine manual (through robots) and duct a wider array of manual and cogni-

cognitive (through software) tasks. The tive tasks.7

102. What is Automation and How Widespread Is It?

Finally, advances in robotics such as soft agriculture. A variety of automated solu-

materials, improved actuators, flexible tions already exists in these sectors. First,

object handling, and greater dexterity in mining and oil and gas exploration are

non-routine environments are enabling activities where humans have long sought

robots to effectively, and with increasing the help of machines, but robotic tech-

efficiency, sort objects, package goods, nologies will increasingly replace tradi-

or prepare materials for further work. tional machine operators. In fact, this is

For example, a humanoid robot from the already happening. The multinational

robotics company Boston Dynamics was mining company Rio Tinto claims it has

recently shown jumping and running in hauled ore and waste materials weigh-

fluid movements, while a small industrial ing over one billion tons (as of January

robot designed by researchers from the 2018) using autonomous trucks operat-

University of California at Berkeley is able ing in Australian mines – a number only

to autonomously detect, safely pick up, set to increase as more trucks are put into

and handle random objects at around operation.9 The South African company

half the speed of humans.8 The Berkeley Randgold Resources has also begun using

researchers expect that their robots will robotic loaders and automated material

soon exceed humans in these tasks. handling systems in its Kibali gold mine in

the Democratic Republic of the Congo.10

Other existing applications include auto-

Automation in different sectors mated drill rigs that blast holes on a pre-

determined path without human control,

A closer look at current automation tech- as well as mining equipment that uses

nology in different economic sectors predictive maintenance systems to reduce

shows a stunning variety of applications costs and interruptions to operations.

in a number of areas, including mining,

agriculture, manufacturing and warehous- Market projections for automation in

ing, textiles, financial services, and health the mining sector claim that automated

care, among many others. While auto- systems such as those highlighted above

mation technologies will bring productiv- will become increasingly common. One

ity gains, better services, and improved market research report suggests that the

user experience, they are also likely to prospect of increased productivity and

bring disruption to the labor market and safety, in combination with lower costs,

change the demand for human workers in may cause the mining automation market

these sectors. to grow by almost 50 percent in the next

six years, reaching $3.29 billion by 2023.11

Automation in the primary sector Estimates of cost savings and efficiency

The primary sector of the economy cen gains are equally staggering. In April 2017,

ters on the extraction of raw materials, McKinsey Global Institute suggested that

for example through mining, fishing, and by 2035, data analytics and robotics could

11Automation and the Future of Work in Sub-Saharan Africa

produce between $290 and $390 billion in ognition that can detect soil specifics and

annual productivity savings for oil, natural irrigation needs, weeds, ripeness of fruits

gas, thermal coal, iron ore, and copper and vegetables, or animal health. These

producers across the globe.12 systems can autonomously analyze a situa-

tion and react to their own unique circum-

Extractive industries in particular will be stances, minimizing human supervision.

at the forefront of automation, given the The incentives for automating agriculture

ability of extractives companies to shoul- are compelling, particularly efficiency gains

der large up-front investments. More from higher crop yields and from reduced

over, the industry’s relatively high wages material and labor costs. Farming, particu-

and overall employee costs (particularly larly on a large, commercial scale, is poised

for operations located in industrialized to go beyond using a single machine, (e. g.,

countries) and stringent safety regula- an autonomous tractor) and connect dif-

tions, as well as potential disruptions in ferent farming technologies to achieve

production from labor disputes, all pro- largely autonomous farming operations

vide incentives for automating tasks and ranging from crop planting to harvesting.

relying less on human labor.13 Impor- The organization “Hands Free Hectare”

tantly, the extractive industries are also recently demonstrated in a trial that a fully

not necessarily dependent on improve- autonomous farming operation is possible,

ments in national infrastructure (e. g., and a market research study from June

high-speed internet connectivity), which 2018 estimates that the global agricul-

are necessary for connecting autono- tural tractor robots market alone will grow

mous machines and running Internet of from $185 million in 2017 to $3.2 billion by

Things (IoT) applications. This is because 2024.14

leading telecommunication equipment

manufacturers already offer proprietary Automation in the secondary

solutions for building local communica- sector

tion systems, such as those needed for The secondary sector – so-called blue-

greater mining automation. collar work – is where raw materials are

processed into more refined goods. It

Second, numerous technological advance- includes manufacturing and construction.

ments in the agricultural sector have In industrialized countries this sector’s

increased productivity while decreasing share of labor as a total of overall employ-

the need for human labor, including driv- ment is moderate, given the transition to

erless and autonomous tractors, fruit and service economies. Nevertheless, manu-

vegetable picking systems, and drones facturing is the backbone of many indus-

for monitoring crops. However, most dis- trialized or industrializing countries and

ruptive for the agricultural sector is the employs millions of workers.

combination of self-learning autonomous

robots doing manual work, (e. g., harvest-

ing crops) with sensors and pattern rec-

122. What is Automation and How Widespread Is It?

Manufacturing has many variations, from claims that one “SEWBOT operator pro-

simple manipulation or assembly of raw duces the same number of T-shirts as

materials to highly complex engineer- 17 manual sewers.”17 The disruptive

ing. While literally meaning “the crea- potential of such technology is evident,

tion of something by hand,” the era of particularly as sewing is the most com-

purely handmade products is long gone. plex step in clothing manufacturing, and

For many decades, machines have sup- accounts “for more than half the total

ported humans in the manufacturing pro- labor time per garment.”18 The speed of

cess, and machines of varying complex- disruption is also staggering: A World

ity enabled the three previous industrial Bank report from 2016 on the future of

revolutions.15 Yet, these machines were the garment industry in South Asia makes

largely limited to specific routine manual no mention of automation, while a 2018

tasks, such as repeatedly bolting pieces report from McKinsey estimates signifi-

together as they went by on an assembly cant levels of automation in that sector

line. Now, the fourth industrial revolution by 2025.19

is set to bring intelligent machines to the

manufacturing process that can increas- Another key development of automation

ingly handle both routine and non-routine in the secondary sector is smaller robots

tasks autonomously. The International that can safely interact with humans.

Federation for Robotics points out that These so-called cobots – short for col-

the demand for industrial robots has laborative robots – are designed to work

accelerated considerably due to the ongo- directly with humans. They are increas-

ing trend toward automation and contin- ingly being integrated into work domains

ued innovative technical improvements in formerly exclusive to humans, for exam-

industrial robots.16 ple, in the non-routine handling of mate-

rials. The key innovations in this respect

While the automotive and electronics are smaller size and simplified “training”

industries have embraced automated of the cobots coupled with advancements

solutions for many years, other sectors in sensor technology, machine learning,

are steadily increasing the use of auto- and greater capabilities in movement and

mated machinery and robots as well. dexterity that make it possible to more

The labor-intensive garment and tex- closely integrate cobots in the production

tiles industry – a critical sector for both process alongside humans.

employment and exports among many

(particularly South Asian) developing The automation revolution in manufac-

countries and emerging economies – is turing also hinges on sensors and pre-

showing first signs of greater automation dictive maintenance. By fitting machines

with semi- or full automation of the sew- with sensors to collect real-time informa-

ing process. For example, the US-based tion on their status and to then compare

company SoftWear Automation now this with data collected from the same

offers a fully automated SEWBOT and machine operating in other locations, the

13Automation and the Future of Work in Sub-Saharan Africa

robots can detect and address potential retailers, such as Walmart in the United

malfunctions in advance, thus decreasing States or Tesco in the United Kingdom,

robot downtime and increasing produc- are experimenting with self-checkout

tivity, further making the case for auto- services or even fully automated pay-

mated technologies.20 ment and cashier system – an unsurpris-

ing development, given that the largest

Automation in the tertiary sector operating costs in the retail industry are

The tertiary sector, or services, includes employees.22

a wide number of industries, includ-

ing logistics, financial services, health Moreover, some companies are begin-

care, education, retail, and research and ning to establish fully cashier-less stores

development. In most industrialized, in the retail sector. For example, the

high-income countries, the tertiary sector Beijing-based retail company JD.com

employs the majority of workers – collec- opened China’s first fully automated

tively about 74 percent of total employ- store in December 2017 and has since

ment. In comparison, the share is signifi- increased coverage within and beyond

cantly lower at 31 percent in Sub-Saharan China.23 Amazon is moving in a similar

Africa.21 In these areas of the economy, direction with its Amazon Go stores in the

the automation revolution is not only United States and, in addition, is utiliz-

about physical robots, but also about soft- ing a mobile application together with

ware that enables, for instance, robotic facial recognition technology to manage

process automation or customer service purchases. While such automated retail

through chatbots. trials show the potential of such technolo-

gies, many retailers still face high costs for

There are abundant examples of how automated systems. In Western countries,

automation is transforming various areas the pace of such changes is moderated

of the tertiary sector, and a few cases by legitimate privacy concerns, customer

where impact is already quite large. The uneasiness about using new technologies,

retail and consumer packaged goods or (expectations of) higher levels of theft

industry is, for instance, undergoing rapid when humans are absent.24 Yet, the cost

changes due to automation. This is an advantages are clear, and it is likely that

industry close to consumers, where many the retail sector will increasingly auto-

manufactured products hit the shelves mate. A market analysis projects that the

and await purchase, either in brick-and- global retail automation market will grow

mortar stores or through online shop- from $10.31 billion in 2017 to $18.76 bil-

ping. In this area, firms are increasingly lion by 2023 – an annual growth rate of

introducing automated systems for ware- around 10 percent.25

housing and stockpiling goods, inventory

checking, self-checkout, and automated The logistics and transportation sector

cashier systems. With regard to auto- is another area where experts expect

mating the payment process, many large substantial levels of automation. The key

142. What is Automation and How Widespread Is It?

developments in this regard are the push The optimists have history on their side.

for autonomous vehicles operating in After all, mechanization and automation

both structured (closed) and unstructured in their historical iterations are nothing

(open) environments, as well as auto- new. Century after century has brought

mated surveillance and the optimization inventions such as windmills, looms, cars,

of logistics processes. DHL, a global logis- and automated teller machines (ATMs)

tics company, pointed out that autono- that led to the demise of jobs and entire

mous vehicles are particularly attractive industries, but also created new profes-

for the logistics sector due to the limited sions, products, industries, and services.

liability of transporting only goods and The invention of the automobile, essen-

not humans.26 Such advantages have tially a machine replacing human or

spurred increasing automation in some animal-powered transportation, led to the

warehousing and port operations.27 Fur- creation of the automotive industry, esti-

ther, car manufacturers such as BMW, mated to employ around nine million peo-

Daimler, Tesla, or Volkswagen, as well as ple across the world directly and around

technology companies such as Alibaba, 50 million people indirectly.31 Moreover,

Alphabet, Apple, Baidu, Uber, or Yandex the continuous mechanization and indus-

are engaging in fierce competition over trialization of agriculture has cut down

their future positions in the autonomous farm labor dramatically. Yet the sector

vehicle market.28 continuously increases its productivity

while different, sometimes entirely new

economic activities have absorbed those

Status of the debate: The affected. Further, although the invention

optimists vs. the skeptics of personal computers ended the careers

of typists, it helped create millions of jobs

The debate about the consequences of in the service industries and opened up

automation for society and the future vast new opportunities for work.

of work is largely polarized.29 One side

comprises the “techno-optimists” who The optimists’ key argument is that while

embrace automation and point to the individuals losing jobs because of new

advances it brings and will continue to technologies may not necessarily find

bring.30 In their view, automation and employment again, the overall effect

artificial intelligence will not only bring on the labor market is net positive. For

new services, but also put an end to instance, evidence from the United States

many unpleasant jobs – particularly those and Germany shows that the much-

deemed dirty, dangerous, and dull – while feared long-term technological unemploy-

new professions and types of work will ment never happened on a broad level.32

emerge. As David Autor argues, “automation has

not wiped out a majority of jobs over the

decades and centuries. Automation does

indeed substitute for labor – as typically

15Automation and the Future of Work in Sub-Saharan Africa

intended. However, automation also circumstances – it remains challenging to

complements labor, raises output in ways develop even a “narrow AI” for a very lim-

that lead to higher demand for labor, ited use case, and it is costly to reprogram

and interacts with adjustments in labor (industrial) robots for different tasks.38 As

supply.”33 Despite (or because of) a mas- a leading robotics researcher explains, “It

sive growth in automation in recent years, is no secret today that the robot itself and

unemployment in industrialized socie- the associated hardware are not the cost

ties is quite low. For example, Japan, the drivers …, but [rather] the programming

United States, and Germany, three of the effort,” and that the “Hollywood-influ-

most automated countries in the world, enced expectations of intelligent, autono-

currently have unemployment rates of mous robots cannot be fulfilled in the

roughly 2.3 percent, 3.7 percent, and short- and medium-term in any way.”39

4.9 percent, respectively.34 The optimists As such, the optimists argue that neither

point to such examples when arguing hardware nor software developments

that automation in the coming years will allow for a rapid shift away from a

and decades will bring more benefits human-centered workforce to a fully

than harm. The World Economic Forum automated one. Rather, the introduction

acknowledges job losses, but also pre- of automation technology will be more an

dicts greater job creation in the period up incremental development than a sudden

to 2022.35 According to another group of event, providing societies and decision-

researchers, the employment scenario for makers time to adjust to changes.

2030 will be one in which “many occupa-

tions have bright or open-ended employ- On the other hand, the “techno-skeptics”

ment prospects.”36 view the automation revolution as an

unprecedented transformation that will

Other experts are less worried about lead to massive unemployment, greater

imminent and large-scale job losses wealth inequality, and social disruption.40

because they see technology not as For them, robots and software will bring

advanced as the hype suggests. The “technological unemployment” that will

usability of non-stationary robots, for eventually make almost all human work

instance, still hinges on energy supply, unnecessary and, unless there is some

and existing battery technology is not form of social protection, society will fail.41

miniaturized and advanced enough to While it may not happen overnight, the

provide enough energy for extensive view is that ongoing advances in hard-

usage.37 Further, developing custom- ware and software will chip away at the

ized software necessary to run autono- breadth of human labor with increasing

mous robots is far from easy. While many speed.

researchers and companies aim for a

“strong AI” – namely an artificial intelli- In this context, the skeptics present four

gence capable of thinking like a human main arguments: First, they point out

and learning by itself irrespective of the that existing technology is already at a

162. What is Automation and How Widespread Is It?

level capable of displacing a high percent- mating a sizable portion of occupations

age of jobs. Technological developments across a number of professions.44 As tech-

have progressed far enough that jobs nology advances, this share will grow.

and occupations previously thought to be

insulated from automation, namely non- Second, the skeptics argue that this time

routine cognitive and manual tasks, are the advancement in automation tech-

increasingly susceptible to automation as nologies is not limited to a specific sector

well. Combining, for instance, light non- or occupation. Instead of an invention

stationary robots with movable grippers upending a single profession, as often

capable of a wide range of motion and seen in the past, the newest technological

accuracy, together with sensor technol- advancements in automation cut across

ogy and cloud-enabled pattern recog- the entire economy and many areas of

nition and communication, allows for work. Location sensors, for instance, can

more autonomous functioning of tech- have many different applications, while

nology and, thus, completely different entire robots, such as Boston Dynamics

uses than those of comparatively crude “SpotMini” or software suites, are devel-

industrial robots introduced in previous oped as platform technologies that allow

decades. While results are highly depend- adaptation to different usages. The soft-

ent on methodology, researchers have ware behind a self-driving car can, for

begun calculating the automation poten- instance, be transferred to other types of

tial of jobs across countries and sectors. vehicles and uses, such as autonomously

In a landmark study, Carl Benedikt Frey operating trucking and warehouse vehi-

and Michael Osborne argue that around cles. These technologies are also matur-

47 percent of total US employment is at ing rapidly and seeing greater adoption

high risk of being automated over the across sectors and countries.

next decade or two.42 A recent study by

the McKinsey Global Institute finds that Third, the skeptics argue that advances

60 percent of occupations have at least in technology are accelerating at a rate

30 percent of constituent work activi- beyond the human ability to adapt to

ties that could be automated, and that, the loss of occupations. The changes we

on a global level, between 75 million and see are rapid and broad, not gradual and

375 million workers may need to switch limited. The basis for this claim is found

occupational categories by 2030.43 While in the many stories of recent technologi-

others calculate much lower figures of cal progress around artificial intelligence

job displacement for the countries repre- such as DeepStack, a poker software

sented by the Organisation for Economic on par with professional poker players,

Co-operation and Development (OECD), or AlphaGo, a software that has beaten

the conclusion of all studies that assess one of the world’s leading players of

tasks and occupations and their suscep- Go, a game so complex that brute-force

tibility to automation is similar: current algorithms do not work. These advances

technology is already capable of auto- demonstrate that forms of complex cog-

17Automation and the Future of Work in Sub-Saharan Africa

nition – a distinctively human feature – will continue at an ever-increasing rate

are no longer exclusively the domain of and that the boundaries of what can be

humans. While computers and robots automated will constantly be pushed fur-

have long been capable of simple cogni- ther out. Even if we were to adopt perfect

tive and manual routine tasks, software policies now for hedging against the com-

applications that are increasingly capable ing risks of automation in a specific sector

of handling complex cognitive and non- or field, we would need to immediately

routine tasks are ubiquitous, together begin to readapt to new changes – and we

with simultaneous advances in robotics.45 would need to do so at an ever-increasing

The consequences for human labor may speed.46 The basis for this claim lies in

be profound. the acceleration of technological develop-

ments and the expectation that certain

Finally, and perhaps most critically, skep- technologies, such as quantum comput-

tics point out that the significant advances ing or a strong AI, will represent tipping

in automation across all sectors is not a points in the field of automation that

one-time revolution with a predetermined open up entirely new applications.

end date. Rather, they posit that change

182. What is Automation and How Widespread Is It?

1 This definition is based partly on the German 11 Market and Markets, Mining Automation

standard for automation: DIN V 19233. Market by Technique, Type (Equipment, Software,

Communications System), Equipment (Autonomous

2 Simonite, Tom (2018): To Keep Pace with Moore’s

Hauling/Mining Trucks, Autonomous Drilling

Law, Chipmakers Turn to ‘Chiplets’,” WIRED,

Rigs, Underground LHD Loaders, Tunneling

November 16, 2018, accessed November 12,

Equipment) and Region – Global Forecast to 2023

2018, https://www.wired.com/story/keep-pace-

(2018), accessed October 4, 2018, https://www.

moores-law-chipmakers-turn-chiplets/.

marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/

3 Should plans for the provision of global broad mining-automation-market-257609431.html.

band access from satellites in low-earth orbit,

12 McKinsey Global Institute (2017): “Beyond the

as envisioned by SpaceX and others, come to

Supercycle: How Technology Is Reshaping

fruition, opportunities for digitalization and

Resources. Executive Summary”, accessed August

automation of services are set to increase even

12, 2018, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/

more.

McKinsey/Business%20Functions/Sustainability%20

4 Theobald, Oliver (2017): Machine Learning for and%20Resource%20Productivity/Our%20Insights/

Absolute Beginners (Stanford, CA: Scatterplot Press). How%20technology%20is%20reshaping%20

supply%20and%20demand%20for%20natural%20

5 Gerrish, Sean (2018): How Smart Machines Think resources/MGI-Beyond-the-Supercycle-Executive-

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press). summary.ashx.

6 Wang, Hongbo; Totaro Massimo; Beccai, 13 PricewaterhouseCoopers (2018): Mine 2018:

“Toward Perceptive Soft Robots: Progress and Tempting Times, accessed November 14, 2018,

Challenges,” Advanced Science 5, no. 9. https://www.pwc.com/id/mine-2018.

7 Routine cognitive or manual tasks denote those 14 See http://www.digitaljournal.com/pr/3809023,

tasks whereby computers follow explicit rules; accessed October 15, 2018.

that is, they are preprogrammed to accomplish a

limited and well-defined set of cognitive activities 15 Stearns, Peter N. (2013): The Industrial Revolution

or manual labor. Non-routine cognitive or manual in World History (Boulder, CO: Westview Press).

tasks, on the other hand, denote activities

16 International Federation for Robotics (2018),

undertaken by a computer to accomplish more

“Executive Summary World Robotics 2018

abstract tasks such as solving problems or using

Industrial Robots”, accessed November 14, 2018,

physical flexibility and sensor technologies to

https://ifr.org/downloads/press2018/Executive_

accomplish manual tasks by adapting behavior

Summary_WR_2018_Industrial_Robots.pdf.

to different environments or situations. See, for

example: Autor, David (2013): The task approach 17 DevicePlus (2018), “SewBot Is Revolutionizing

to Labor Markets: An Overview,” Journal for Labor the Clothing Manufacturing Industry”,

Market Research 46, no. 3. accessed September 22, 2018, https://www.

deviceplus.com/connect/sewbot-in-the-clothing-

8 Knight, Will (2018): Exclusive: This Is the Most

manufacturing-industry/.

Dexterous Robot Ever Created,” MIT Technology

Review, March 26, 2018, accessed October 18 McKinsey & Company (2018), “Is Apparel

4, 2018, https://www.technologyreview. Manufacturing Coming Home? Nearshoring,

com/s/610587/robots-get-closer-to-human-like- Automation, and Sustainability – Establishing a

dexterity/. Demand-Focused Apparel Value Chain”, accessed

October 15, 2018, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/

9 See https://www.riotinto.com/documents/180130_

media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20

Rio_Tintos_autonomous_haul_trucks_achieve_

insights/is%20apparel%20manufacturing%20

one_billion_tonne_milestone.pdf, accessed January

coming%20home/is-apparel-manufacturing-

21, 2019.

coming-home_vf.ashx.

10 See http://www.miningweekly.com/article/

19 World Bank (2016): “Stitches to Riches. Apparel

commissioning-of-automated-underground-

Employment, Trade and Economic Development

mine-drives-growth-at-randgolds-kibali-

in South Asia” (Washington, DC: World Bank and

mine-2018-04-24/rep_id:3650, accessed

McKinsey).

January 21, 2019.

19Automation and the Future of Work in Sub-Saharan Africa

20 For example, at the 2017 Hannover Messe, a 28 Engineers distinguish between five levels of

representative from the company Bosch Rexroth autonomous driving: level zero means no

claimed that their new predictive maintenance automation at all, and the driver is fully in

tool OdiN (“Online Diagnostic Network”) could charge; whereas level five is the opposite: the car

identify problems with a 99 percent success rate, drives without any human action or interference.

compared to the 43 percent of a human expert At this point, level three cars are commercially

conducting regular checks. See: Deutsche Messe available, and firms are racing to reach level four

AG Hannover, „MDA zeigt Predictive Maintenance within the next two to four years.

Anwendungen Digitalisierung, Vernetzung und

29 For an overview of the historical roots of the

Kommunikation der Instandhaltung” (2017),

debate, see: Spencer, David A. (2018): “Fear and

accessed September 22, 2018, https://www.

Hope in an Age of Mass Automation: Debating

presseportal.de/pm/13314/3528467.

the Future of Work.” New Technology, Work and

21 World Bank (2018), “Employment in Industry (% Employment 33, no. 1.

of total employment) (modeled ILO estimate)”,

30 It is not really clear who coined the term techno-

accessed November 14, 2018, https://data.

optimists. We give credit to Duncan Green

worldbank.org/indicator/SL.IND.EMPL.

because this is where we read the term first.

ZS?end=2017&name_desc=false&start=1991&vie

See: Green, Duncan (2017): “20th Century

w=chart.

Policies May Not Be Enough for 21st Century

22 NCR (2012), “NCR to Install 10,000 Self-Checkout Digital Disruption: From Poverty to Power”,

Devices at More Than 1,200 Walmart Locations”, accessed November 22, 2018, https://

accessed November 14, 2018, https://www.ncr. oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/20th-century-policies-

com/news/newsroom/news-releases/retail/ncr- may-not-be-enough-for-21st-century-digital-

to-install-10-000-self-checkout-devices-at-more- disruption/.

than-1-200-walmart-locations; Jamie Rigg (2015),

31 International Organization of Motor Vehicle

“Tesco’s Self-Service Checkouts Are Getting A Lot

Manufacturers (OICA) (No date), “Employment”,

Less Irritating,” Engadget, July 30, 2015.

accessed November 14, 2018, http://www.oica.

23 JD (2018), “JD’s Unmanned Store Goes Global”, net/category/economic-contributions/auto-jobs/.

accessed January 11, 2018, https://jdcorporateblog.

32 Muro, Mark; Maxim, Robert; and Whiton, Jacob

com/jds-unmanned-store-goes-international/.

(2019): “Automation and Artificial Intelligence.

24 Rene Chun (2018), “The Banana Trick and Other How Machines Are Affecting People and Places”

Acts of Self-Checkout Thievery,” The Atlantic, (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution); Jens

March 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/ Südekum (2018), “Robotik und ihr Beitrag zu

magazine/archive/2018/03/stealing-from-self- Wachstum und Wohlstand” (Berlin: Konrad-

checkout/550940/. Adenauer-Stiftung).

25 Oristep Consulting (2018), Global Retail Auto 33 Autor, David (2015): “Why Are There Still So Many

mation Market – by Type, Component, Operator Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Auto

Type, Implementation, End User, Region – Market mation,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 29, no. 3.

Size, Demand Forecasts, Company Profiles, Industry

34 See https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/roudou/

Trends and Updates (2017–2023).

results/month/index.html (Japan); https://

26 DHL Trend Research (2014), “Self-Driving Vehicles data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000 (USA);

in Logistics. A DHL Perspective on Implications https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/Navigation/

and Use Cases for the Logistics Industry”, Statistik/Statistik-nach-Themen/Arbeitslose-und-

accessed November 22, 2018, https://delivering- gemeldetes-Stellenangebot/Arbeislose-und-

tomorrow.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/ gemeldetes-Stellenangebot-Nav.html (Germany) –

dhl_self_driving_vehicles.pdf. all accessed November 13, 2018.

27 McKinsey & Company (2018), “The Future of 35 Based on a survey among companies

Automated Ports”, accessed January 22, 2019, representing 15 million workers. See World

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel- Economic Forum (2018), The Future of Jobs Report

transport-and-logistics/our-insights/the-future- 2018 (Geneva: WEF).

of-automated-ports.

202. What is Automation and How Widespread Is It?

36 Bakhshi, Hassan et al. (2017): The Future of Skills: and%20demand%20for%20natural%20

Employment in 2030 (London: Pearson and resources/MGI-Beyond-the-Supercycle-

Nesta). Yet, one also needs to factor-in the aging Executive-summary.ashx.

societies that characterize Japan and Germany.

44 See, for instance: Arntz, Melanie et al. (2016):

37 Crowe, Steve (2018): “10 Biggest Challenges in “The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD

Robotics. The Robot Report”, accessed November Countries: A Comparative Analysis” (Organisation

17, 2018, https://www.therobotreport.com/10- for Economic Co-operation and Development

biggest-challenges-in-robotics/. Also, an interview [OECD] Social, Employment and Migration

conducted by the authors. Working Papers, no. 189, Paris).

38 Turck, Matt (2018), “Frontier AI: How Far Are 45 Frey and Osborne (2013).

We from Artificial ‘General’ Intelligence, Really?”

46 Skipper, Clay (2018), “The Most Important

Medium, April 18, 2018, accessed November 17,

Survival Skill for the Next 50 Years Isn’t What

2018, https://hackernoon.com/frontier-ai-how-

You Think,” GQ, September 30, 2018, accessed

far-are-we-from-artificial-general-intelligence-

November 17, 2018, https://www.gq.com/story/

really-5b13b1ebcd4e.

yuval-noah-harari-tech-future-survival.

39 Automatica (no date): „Der Hype um Künstliche

Intelligenz ist übertrieben”, accessed November

17, 2018, https://automatica-munich.com/ueber-

die-messe/newsletter/meinung/kuenstliche-

intelligenz/index.html.

40 See, for instance: Kaplan, Jerry (2015): Humans

Need Not Apply: A Guide to Wealth and Work in

the Age of Artificial Intelligence (New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press); Ford, Martin (2015): Rise

of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a

Jobless Future (New York: Basic Books; Blit, Joel;

Amand, Samantha, and Wajda, Joanna (2018):,

“Automation and the Future of Work: Scenarios

and Policy Options,” (Waterloo, Ontario: Centre

for International Governance Innovation).

41 John Maynard Keynes had already introduced

the term technological unemployment in 1930

in his famous essay “Economic Possibilities for

Our Grandchildren.” Keynes, however, saw such

unemployment as a transitory phenomenon and

not as a final state for entire societies. The essay

is available at http://www.econ.yale.edu/smith/

econ116a/keynes1.pdf, accessed August 12, 2018.

42 Frey, Carl Benedikt; Osborne, Michael (2013): The

Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs

to Computerisation? (Oxford, UK: Oxford Martin

School, University of Oxford).

43 McKinsey Global Institute (2017), “Beyond the

Supercycle: How Technology Is Reshaping

Resources, Executive Summary”, accessed

August 12, 2018, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/

media/McKinsey/Business%20Functions/

Sustainability%20and%20Resource%20

Productivity/Our%20Insights/How%20

technology%20is%20reshaping%20supply%20

213. Analytical Framework:

Factors Driving or

Inhibiting Automation

While it is clear that advances in tech- The first factor is social structure, which

nology have enabled various types of refers here to demographic trends and

automation across different sectors, it is educational quality, and societal atti-

nevertheless erroneous to assume that tudes toward automation shaped primar-

technological advances alone are driving ily through public discourse. The second

the automation revolution. The adoption is the regulatory landscape, for exam-

of automation technology is not simply a ple, minimum wage policies and worker

consequence of its availability, rather, a protection rights, but also industrial

number of underlying factors either ena- policies or laws that allow for the testing

ble or stall the use of automation techno and usage of certain technologies. The

logies. Based on existing research around third factor is the availability and qual-

industrial innovation, this paper presents ity of infrastructure and the availability of

four key factors driving or inhibiting auto- finance for new technologies. Finally, the

mation that serve as a basis for assessing fourth factor driving or inhibiting automa-

the implications of automation in Sub- tion is the actual economic viability of uti-

Saharan Africa. lizing automation technologies (Figure 2).1

23Automation and the Future of Work in Sub-Saharan Africa

Figure 2: The drivers and inhibitors of automation

Social Regulatory Infrastructure Economic

structure landscape and capital viability

Quality of

Demographic Minimum Total cost

digital infra-

trends wage assessments

structure

Educational Worker Capital for

Competition

quality protection R&D

Industrial Global

Societal

(innovation) economic

attitudes

policies trends

Taxation

Source: Authors.

While these factors provide a useful basis textualized factor that strongly affects a

for analyzing likely pathways for the use firm’s decision to automate. Nevertheless,

of automation technologies, two caveats this list of factors provides an adequate

exist. First, these factors vary by country, framework to draw broad conclusions

sector, and even subsector, making it diffi- on the likelihood, or the improbability,

cult to make conclusive statements about of automation occurring across Sub-Saha-

the extent to which automation technolo- ran Africa. In this respect, one of the key

gies are, or may be, used. Second, the aims of this discussion paper is to spark

factors also do not have equal weight in a wider discussion on this issue and to

determining potential paths, and their inspire further research. It is not to make

respective influence can again vary by definitive statements or calculate the like-

country, sector, and subsector. In par- lihood of automation for a country or a

ticular, economic viability is a highly con- sector.

243. Analytical Framework: Factors Driving or Inhibiting Automation

Social structure Another critical social factor is education

policy. The OECD calls for educational poli-

The rate at which a particular society cies that promote not only basic informa-

embraces automation is in part depend- tion technology skills and programming,

ent upon its social structure, particularly but also specialization in engineering and

its demography, educational policies, machine-learning, while also leveraging

and societal attitudes toward technology. the latest research to evolve educational

First, demography is quite important for systems to keep up with the advancement

the labor market. An aging society, for of new technologies.4 While the intention

instance, can lead to labor shortages that of such policies is to better position youth

make it difficult for firms to fill vacan- to find careers in the economy of the

cies. On the other hand, a comparatively future, they also help shape public atti-

young society with many job seekers may tudes toward automation, namely to make

find it difficult to create enough entry- more socially acceptable the increasing

level positions for those with limited replacement of human workers with hard-

work experience and work-related skills. ware and software. In short, educational

In both cases, automation technology systems that are teaching specialized skills

offers a potential alternative. In Ger- to stay ahead of an increasingly auto-

many and Japan – both aging societies mated workforce are quite likely helping

with low population growth – researchers to create the self-fulfilling prophecy of an

regularly express the notion of automa- automation revolution.5

tion as a sensible way to fill the posi-

tions of soon-to-be-retired workers. One Finally, societal attitudes are another

study estimates that, in the next decade, important factor influencing uptake of,

automation and other efficiency meas- or resistance to, automation technolo-

ures can fill an expected gap of roughly gies. In Japan, a country with one of the

10 million workers in Germany without highest ratios of robots per inhabitant,

increasing overall unemployment.2 The there is a strong openness toward robots

International Monetary Fund (IMF) makes and automation. Portrayed at times as

a similar argument in the case of Japan, the “Land of Rising Robots,” such accept-

arguing that “with labor literally disap- ance of robots “is founded on Japanese

pearing [in Japan] and dim prospects for Animism, the idea of Rinri, and its rapid

relief through higher immigration, auto- modernization.”6 In stark contrast, West-

mation and robotics can fill the labor gap ern societies influenced by monotheistic

and result in higher output and greater religions tend to advance the notion that

income rather than replacement of the robots are objects detached from their

human workforce.”3 Such demographic human creators and capable of turning

circumstances influence automation against them. Popular Western references

uptake considerably. in this vein are HAL 9000 from the film

2001: A Space Odyssey and the epony-

mous character from The Terminator. Such

25Automation and the Future of Work in Sub-Saharan Africa

societal attitudes likely influence specific able employment held by low-skilled

views on automation as well. For example, workers and increases the likelihood that

in a survey conducted in the United States low-skilled workers in automatable jobs

by the Pew Research Center in 2017, become non-employed or employed

72 percent of respondents expressed in worse jobs.”10 In other words, higher

worry about “a future in which robots and minimum wages lead to more automa-

computers are capable of doing many tion. Results of a study on minimum wage

jobs that are currently done by humans.”7 effects in the United Kingdom corroborate

In Europe, the numbers are roughly the this finding by concluding higher minimum

same, with 74 percent expecting that the wages and expansion of those eligible for

use of robots and artificial intelligence will minimum wages are linked to replace-

lead to a net loss in jobs.8 ments by automation technology.11

Second, the extent of worker protection

The regulatory landscape programs in a country also plays a role

in determining the likelihood that exist-

Regulatory decisions by governments ing jobs may be automated, at least in the

greatly influence the uptake of automa- short to medium terms.12 It is difficult for

tion technologies in a country as a whole companies to significantly cut jobs while

or within specific sectors. The most criti- pursuing automation in countries with

cal fields of regulatory decisions with an stronger worker protection policies, such

impact on automation are minimum as the Nordic states, Germany, or South

wage policies, worker protection pro- Africa. In the United States, the National

grams, and industrial (innovation) and Labor Relations Board, responsible for

taxation policies.9 enforcing labor law, has already set pre

cedents with regard to the impact of labor

First, labor market policies strongly influ- unions on automation and vice versa,

ence the rate of adoption of automation by ruling that automation is a matter for

in a country or sector, particularly poli- mandatory bargaining. This clearly makes

cies governing minimum wage and worker the case for automation more difficult.13

protection programs. Minimum wage The implication of such policies is that,

effectively aims to shield employees from while high levels of worker protection

poverty by mandating a wage floor. While in an industry or a country can prevent

minimum wage prevents price competi- job losses for those already employed,

tion in a labor market with a high supply they also act as a barrier for the creation

of workers, it also increases unit produc- of new jobs for human workers. Conse-

tion costs and shifts cost-benefit calcula- quently, worker protection regulations act

tions of automating human labor. A recent as an incentive to use automated labor

study on the US labor market found that and forgo future hiring to avoid the need

“increasing the minimum wage signifi- for compliance with worker protection

cantly decreases the share of automat- regulations.14

26You can also read