A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in Indonesia - THE CASE FOR IMPROVED ECONOMICS AND SUSTAINABILITY

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in Indonesia THE CASE FOR IMPROVED ECONOMICS AND SUSTAINABILITY

Boston Consulting Group partners with leaders in business and society to tackle their most important challenges and capture their greatest opportunities. BCG was the pioneer in business strategy when it was founded in 1963. Today, we help clients with total transformation—inspiring complex change, enabling organizations to grow, building competitive advantage, and driving bottom-line impact. To succeed, organizations must blend digital and human capabilities. Our diverse, global teams bring deep industry and functional expertise and a range of perspectives to spark change. BCG delivers solutions through leading-edge management consulting along with technology and design, corporate and digital ventures—and business purpose. We work in a uniquely collaborative model across the firm and throughout all levels of the client organization, generating results that allow our clients to thrive.

A STRATEGIC APPROACH

TO SUSTAINABLE SHRIMP

PRODUCTION IN INDONESIA

THE CASE FOR IMPROVED ECONOMICS AND SUSTAINABILITY

HOLGER RUBEL

WENDY WOODS

DAVID PÉREZ

SHALINI UNNIKRISHNAN

ALEXANDER MEYER ZUM FELDE

SOPHIE ZIELCKE

CHARLOTTE LIDY

CAROLIN LANFER

November 2019 | Boston Consulting GroupCONTENTS

4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

7 MARKET FORCES ARE RESHAPING THE GLOBAL SHRIMP

INDUSTRY

9 INDONESIA’S SHRIMP INDUSTRY IS VULNERABLE

TO GROWING THREATS

Demand for Indonesian Shrimp Is Rising at Home and Abroad

Extreme Weather and Diseases Threaten Indonesia’s Shrimp

Industry

Indonesia’s Geography Presents Barriers to Profitability

Indonesia’s Value Chain Is Complex

14 INDONESIA: THE CASE FOR CHANGE

Low-Price Competitors

Market Demand and Traceability Regulations

High Risk of Disease and Environmental Threats

21 INDONESIA’S PRODUCERS CAN CREATE IMMEDIATE

ECONOMIC VALUE

Feed Mills: Increase Profit Margins and Diversify the Portfolio with

Functional Feed

Hatcheries: Ensure the Quality of Post-Larvae Shrimp Through

Selective Breeding

Farmers: Immediate Change Can Increase Profits, but Broader

Changes Will Be Required

Middlemen: Increase the Pace of Change Through Education,

Finance, and Traceability

Processors: Important Drivers for Change as the Industry Moves

Toward Sustainability

Immediate Change Is Limited—Disruptive Transformation Is

Needed

31 INTEGRATED PLAYERS MUST SUPPORT THE SHIFT

TO TRACEABILITY

32 WITH TRACEABILITY, PRODUCERS CAN MEET EXPORT

STANDARDS

The Far-Reaching Business Benefits of Traceability

Traceability Can Be Managed with Different Levels of Effectiveness

and Maturity

Technology-Enabled Traceability Offers a Promising Path Forward

2 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in Indonesia36 INDOOR FARMS WILL TRANSFORM INDONESIA’S SHRIMP

INDUSTRY

39 THE SHRIMP INDUSTRY MUST TRANSFORM

WHILE TIMES ARE STILL GOOD

40 APPENDIX

Functional Feed, Water Improvement Systems, and Solar Energy

• Details on Functional Feed

• Details on Water Improvement Systems—Biofloc and RAS

• Details on Solar Energy

Market Dynamics and the Environmental Impact of Immediate

Change

• Feed Mills

• Hatcheries

• Farmers

• Middlemen

• Processors and Exporters

60 NOTE TO THE READER

Boston Consulting Group | 3EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

I ndonesia has established itself as one of the world’s top

shrimp producers, but low-price competitors, tightening regulations,

and environmental risks are threatening its strong position. As

outbreaks of disease were slowing production in Thailand and

Vietnam over the past two decades, Indonesia strengthened its

position to become the third-largest shrimp producer globally. The

country’s farmed-shrimp industry is expected to grow 8% per year

through 2022, surpassing global growth rates of 5.6%.

Indonesia has a strong competitive position, with high national

and international demand and an optimistic overall market fore-

cast, but three developments are threatening the industry’s prof-

itability.

•• Global Competition. India has flooded the market with low-price

shrimp, ramping up the competition, stealing market share, and

squeezing profit margins.

•• Strict Traceability Standards. In 2018, the US Congress extended

coverage of the Seafood Import Monitoring Program to cover

shrimp, requiring stricter reporting and record keeping for shrimp

imports. Given that the US is a major importer of Indonesian

shrimp, there’s pressure for Indonesia to provide traceability

across its supply chain.

•• Natural Disasters. Tsunamis, floods, and diseases continue to

affect shrimp production and disrupt the shrimp supply chain. In

2018, for example, a tsunami that hit Banten province lowered

national shrimp production by approximately 10% over a three- to

four-month period. Decades of mangrove deforestation make

Indonesia increasingly vulnerable to these natural disasters.

Indonesian shrimp producers can benefit from immediate im-

provements, but there is a much bigger opportunity at hand.

4 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in Indonesia•• To increase profitability and resource efficiency, the Indonesian

shrimp industry can make immediate changes in three areas: feed,

water treatment, and renewable energy.

•• However, immediate changes should be viewed as only the first

step toward a much more transformative approach to shrimp

farming.

To maintain its position as a leading exporter of shrimp to the

US, Indonesia needs to offer fully traceable products.

•• Regulators and retailers, pushed by consumer demands and

reputational concerns, are becoming increasingly concerned about

food safety and sustainability.

•• With its high dependence on middlemen, Indonesian shrimp

producers are not well positioned to fulfill major importers’ ever

stricter traceability requirements.

•• By offering a fully traceable product, Indonesia can respond to

changing consumer demands, stay ahead of tightening US import

standards, and establish a leading position in both the mass

market and the sustainable shrimp market.

•• While Indonesia has strong domestic demand for shrimp and is,

therefore, less dependent on import regulations, traceability

will eventually become the new norm in global shrimp supply

chains.

•• While a few large players in Indonesia are beginning to focus on

certification, sustainability, and traceability, there’s still much work

to be done.

To protect farms against outbreaks of disease and environmental

risks, a shift to closed-loop—and, ultimately, indoor—systems can

be a game changer.

•• Closed-loop systems, such as recirculating aquaculture systems,

represent a significant opportunity to increase efficiency and

output on L. vannamei farms while reducing the risk of disease

and pressure on the environment.

•• Indonesia has already begun to establish closed-loop farm-

ing methods through its “supra intensif Indonesia” farming

system. While closed-loop farming systems will likely become

more common, the ponds are mostly outdoors and, therefore,

still vulnerable to disease, contamination, and environmental

hazards.

•• To protect shrimp ponds from environmental hazards, stabilize wa-

ter quality, and reduce disease risk, companies can shift to fully

closed indoor systems. This production method allows farm

operators to increase stocking densities and offer a fully traceable

product with low environmental impact.

Boston Consulting Group | 5•• As major importers continue to institute stricter regulations on

seafood imports, the demand for sustainable shrimp will only

grow. By shifting to closed-loop—or even indoor—farming,

Indonesian shrimp producers can meet this demand and position

themselves at the forefront of this movement.

Fast-moving competitors are threatening to overtake Indonesia

in the mass market, and major importers are demanding trace-

ability. To maintain a strong position and strengthen ties with the

US market, Indonesian shrimp producers must make a rapid

transition to traceability and sustainability.

6 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in IndonesiaMARKET FORCES ARE

RESHAPING THE GLOBAL

SHRIMP INDUSTRY

F armed shrimp is among the fastest-

growing food products in the world. In

less than two decades, global production has

become the second-largest shrimp producer

worldwide after China—accounting for 14%

of global shrimp production with 600,000

more than tripled from about 1.2 million tons tons produced annually. Indonesia was also

in 2000 to some 4.2 million tons in 2017. As able to strengthen its already competitive po-

the global population and consumer afflu- sition in the global shrimp market, overtaking

ence grow, farm-raised shrimp is becoming an Thailand and Vietnam, to claim third place.

increasingly important source of protein

around the world. In the US alone, the In 2018, the global shrimp market experi-

average annual consumption of shrimp has enced a price drop that was the result of high

risen to four pounds per capita. inventory levels in import nations such as the

US, further squeezing profit margins and giv-

In 2017, the global market for shrimp, includ- ing low-cost players an advantage.

ing farm-raised and wild-caught shrimp, was

valued at around $40 billion. The dominant Indonesian producers must find new ways to

species of farmed shrimp, Litopenaeus stay ahead of fast-moving, low-price competi-

vannamei (L. vannamei), or whiteleg shrimp, tors while coping with demand dynamics.

accounts for about $14 billion. Shrimp pro-

duction worldwide is expected to grow by The global trend toward environmentally sus-

more than 5.6% annually, with the greatest tainable and socially responsible food pro-

demand coming from China and the US. duction has raised questions about food safe-

ty and sustainability within the shrimp

The overall industry is growing at a record industry. Retailers, regulators, and consumers

pace, but not all shrimp producers are thriving. have become much more attuned to the neg-

ative environmental and social impact of as-

In the early years of this century, China, Thai- pects of unregulated shrimp production, in-

land, and Vietnam were leaders in the shrimp cluding the use of banned chemicals,

farming sector—with Indonesia in fourth environmental degradation, and human and

place. But the competitive landscape has labor rights violations.

shifted. Outbreaks of disease and rising labor

costs have threatened this once-thriving in- In a world with 24-hour access to social me-

dustry, and India, which has dramatically in- dia, ongoing consumer awareness campaigns,

creased its share in the global shrimp market new regulations in importing countries, and

by producing large volumes at low prices, has accelerated dissemination of information

Boston Consulting Group | 7worldwide, retailers face intense pressure to too, are increasing their monitoring of shrimp

protect their brands from the damage that re- imports for drug and chemical residuals and

sults from product recalls, scandals, and sup- are threatening to ban imports. Any company

ply chains that are disrupted by new import charged with regulatory violations would risk

controls. suffering serious economic losses and reputa-

tional damage.

As more attention is focused on these issues,

retailers, regulators, and, in some cases, con- As the demand for sustainability grows, there

sumers are demanding sustainably produced, is increasing urgency for a paradigm shift to-

traceable products in nearly all food catego- ward truly responsible production and sourc-

ries. From 2012 through 2017, the sustainable ing. Retailers’ pledges of sustainability and

seafood segment in major European markets niche consumers’ increasing willingness to

grew by about 12% while market demand for purchase sustainable products represent for-

other seafood segments declined. Similar ward movement. However, the definition of

trends have been observed in the US, though “sustainability” is not consistently precise.

on a smaller scale, and the growth of sustain- There are many different ways to define sus-

able products in China has been driven main- tainability, and retailers and consumers may

ly by food safety scandals and government unknowingly purchase products that fall

targets. Overall, there is growing demand for short in fundamental areas, such as environ-

responsibly produced shrimp, and a niche mental stewardship and social responsibility.

consumer segment is willing to pay a premi-

um for it. To foster real change, it is important to estab-

lish a clear definition of what it means for

A 2015 survey of approximately 3,000 con- food to be labeled sustainable. To put it sim-

sumers worldwide found that 68% wanted to ply, sustainable products should be produced

know where their food was coming from and today in ways that do not compromise the

how it was being produced. While statistics ability to produce those same products to-

show that this consumer-driven pressure is morrow. Products should minimize environ-

currently less urgent in the US and China, mental degradation and the use of natural re-

these countries have introduced stricter im- sources and should be traceable across the

port regulations and government targets. supply chain to provide greater transparency

and accountability. For sustainability to have

Nearly all major retail chains, supermarkets, maximum impact, it is important for all

and convenience stores around the world stakeholders to understand and adhere to

have pledged to increase their share of sus- these fundamental principles.

tainably produced food, including shrimp and

other seafood categories, and, as a form of le- To defend its current strong competitive posi-

gal risk insurance, an increasing number of tion, Indonesia needs to embrace sustainability.

major retailers are requiring suppliers to sign As changes are implemented across the supply

contracts and carry out in-depth due dili- chain, it will be imperative to align on the defi-

gence to ensure traceability and adherence to nition of sustainability and establish mecha-

ecofriendly production methods. Regulators, nisms that will hold all actors accountable.

8 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in IndonesiaINDONESIA’S SHRIMP

INDUSTRY IS VULNERABLE

TO GROWING THREATS

I ndonesia, which was able to strengthen

its global competitive position owing to

outbreaks of diseases and production issues

Fisheries contribute about 2% to Indonesia’s

GDP, and farmed shrimp has a production

value of about $4 billion, which represents

in Thailand and Vietnam in the early years of about 15% of the fisheries sector. Aquaculture

this decade, is currently the third-largest in Indonesia, including processing and ex-

shrimp producer in the world, with a global ports, employs around 8.7 million people,

market share of 12%. The country produces which is about 7% of the total workforce. Of

between 450,000 to 500,000 tons of shrimp.1 this 8.7 million, approximately 1 million in-

(See Exhibit 1.) dividuals are directly affected by shrimp

farming.2

Demand for Indonesian Shrimp Is It’s difficult to estimate the total number of

Rising at Home and Abroad shrimp farms in Indonesia since many do not

Indonesia exports 220,000 to 260,000 tons of operate on a commercial scale. Still, it is as-

shrimp: about 60% to the US, 19% to Japan, and sumed that some 80,000 to 95,000 farms pro-

5% to the EU. Indonesia is the second-largest duce shrimp. Approximately 80% of farms

shrimp exporter to the US, just behind India. produce shrimp extensively, focusing P.

L. vannamei shrimp accounts for 70% to 8o% of monodon production. However, these exten-

export share, while Penaeus monodon, or P. sive farms contribute to only about 10% of

monodon (black tiger shrimp), which is pri- the production output volume. (See the side-

marily exported to Japan, accounts for 20% to bar “Once the Main Species, P. Monodon Is

30%. (See Exhibit 2.) Relative to other Asian Losing Importance.”)

countries, domestic demand in Indonesia is

high—around 40% of total production.

Extreme Weather and Diseases

This high domestic demand gives Indonesia a Threaten Indonesia’s Shrimp

competitive advantage as the domestic market Industry

is less affected by external factors, such as Indonesia’s unique environment and location

stricter import regulations or retailers’ de- can impede shrimp farming. During the dry

mands for traceability and sustainability. season, increased salt content in the water

Still, a strong domestic focus that makes lengthens breeding periods for shrimp, and

them less dependent on global export markets the rainy season can contribute to increased

may mean that companies will be less likely to acidity in ponds, lower water temperatures,

shift toward traceability and sustainability. and flooding.

Boston Consulting Group | 9Exhibit 1 | With a 12% Market Share, Indonesia Is the World’s Third-Largest Shrimp Producer

Global aquaculture production of shrimp, 2017

Market share (%)

29 China 1,200

14 India 600

12 Indonesia 490

11 Ecuador 480

11 Vietnam 450

8 Thailand 327

3 Mexico 128

2 Bangladesh 80

2 Philippines 62

1 Myanmar 54

1 Brazil 52

1 Malaysia 43

5 Other 209

Total 4,175

0 1,000 2,000 3,000 4,000

Production volume (kilotons)

Official figures, reviewed and adjusted in response to overestimations by official authorities

Sources: Cámara Nacional de Acuacultura; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), FishStat Plus (2016); Thailand

Department of Fisheries; Imarc Research; BCG analysis.

Note: The figure for India is for fiscal year 2017–2018.

Extreme weather conditions can also affect In 2012, Indonesia suffered less from the ear-

hatcheries and farms. In 2018, for example, a ly mortality syndrome (EMS) disease out-

tsunami that hit Banten province damaged break than other Asian countries. This was

28 hatcheries and many shrimp farms in Lam- partly because of the physical distance be-

pung, and national production was reduced tween islands, which makes it more difficult

by up to 10% over a three- to four-month peri- for viruses to spread, and partly because the

od. The tsunami also disrupted operations government had taken action to prevent the

across the value chain, and the feed industry spread of disease. During the EMS outbreak,

suffered drops in demand of as much as 6,000 for example, the country banned the import

tons per month over the same period. of foreign post-larvae shrimp (PL).

During the late 1980s and 1990s, Indonesia was Nevertheless, the country is still threatened

heavily affected by various disease outbreaks, by outbreaks of diseases. In 2016, disease out-

such as white spot disease, yellowhead disease, breaks reduced shrimp production by as much

and monodon-type baculovirus. These out- as 100,000 tons—about 20% of current overall

breaks of diseases reduced shrimp production production. However, this decline in produc-

by about 50,000 tons—about one-third of the tion could partly be offset with intensification

production volume during that time. efforts and growth in other regions.

10 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in IndonesiaExhibit 2 | Indonesia’s Shrimp Exports Go Mainly to the US and Japan

EU

2% Japan

US 4% 10%

80% 32%

47%

Other

countries

8%

17%

L. vannamei = 70%–80% of total exports, or 170 kilotons to 190 kilotons

P. monodon = 20%–30% of total exports, or 50 kilotons to 70 kilotons

Sources: BKIPM; Ipsos; Statistics Indonesia; BCG analysis.

Note: L. vannamei = Litopenaeus vannamei; P. monodon = Penaeus monodon. Export volume in 2017 in the nonfishery category was about 240

kilotons. The data on export distribution is from 2018.

Indonesia’s Geography Presents er Asian countries—double, for example, the

Barriers to Profitability energy costs of Vietnamese farmers.

Indonesia’s farms, spread widely over its is-

lands, face two challenges that make it diffi-

cult to be highly profitable: dependence on Indonesia’s Value Chain Is Complex

middlemen and energy generation that is un- Indonesia’s farmed-shrimp supply chain com-

reliable due to unstable grid connections. prises several interrelated steps: feed mills,

hatcheries, farmers, middlemen, processors, ex-

Middlemen connect farmers with feed mills, porters, and retailers. (See Exhibit 3.)

hatcheries, and processors. Each middleman

takes 1.4% to 5% of farmers’ profits. In some This report focuses on the first five steps:

regions, middlemen have extraordinary control

over farmers either because the farmers are in •• Feed Mills. Six players dominate the

debt or because of strong family ties, such as Indonesian feed market with 78% of the

the relationships in East Kalimantan with Bugi- market. The two most dominant players

nese middlemen, the so-called Punggawa. are Central Proteina Prima (CP Prima)

and CJ Aquaculture & Fishery (CJ).

The lack of a stable energy supply poses diffi-

culties for Indonesian shrimp farmers located •• Hatcheries. CP Prima controls 40% to

on remote islands. In these regions, shrimp 50% of the market in hatcheries, while the

farmers rely on diesel generators at specific rest of the market is highly fragmented.

times to secure power for crucial equipment,

such as aerators. Energy accounts for 15%— •• Farmers. The overall market is fragment-

that is 9% for diesel energy and 6% for grid ed, with many family businesses. CP

energy—of Indonesian farmers’ costs. After Prima and Japfa have high market

feed, energy is the second-most expensive share—about 20% to 25% and 10% to 15%,

cost driver for Indonesia’s farmers. Their en- respectively—in this segment, but they

ergy costs are significantly higher than in oth- also rely on middlemen.

Boston Consulting Group | 11ONCE THE MAIN SPECIES, P. MONODON IS LOSING

IMPORTANCE

Two main shrimp species are produced in margins at the farm level, compared with

Indonesia: L. vannamei (whiteleg shrimp) 16% for L. vannamei.

and P. monodon (black tiger shrimp). P.

monodon is native to Indonesia. L. vanna- Because P. monodon can be produced only

mei was introduced in 2001 after outbreaks extensively, annual profits at the farm level

of diseases, such as white spot disease, in are substantially lower than those of L.

the 1990s severely hit production of P. vannamei. (See the exhibit below.) P.

monodon. Furthermore, L. vannamei is monodon yields around $1,700 in profits

better suited to intensive farming and can, per hectare, compared with as much as

therefore, be produced with higher yields $17,400 per hectare for L. vannamei.3 In

per hectare. addition, the extensive production method

requires large amounts of land, exacerbat-

With the introduction of L. vannamei in ing land use challenges and, in some cases,

Indonesia, market share of P. monodon mangrove deforestation.

declined quickly, and that share is now

down to some 30%.1 Production of P. Notes

monodon is expected to remain largely 1. Based on overall production volume in Indonesia.

stable, growing by 2% per year. In con- 2. Based on overall production volume in Indonesia.

trast, L. vannamei farming, which makes 3. Based on a productivity of 400 kilograms per

hectare per cycle and 2.5 cycles per year versus

up some 70% of Indonesia’s total pro- 10,000 kilograms per hectare per cycle and 3 cycles

duction, is expected to grow by 10% per year, respectively.

annually.2

Larger companies, such as the Japanese

processor and exporter Alter Trade Indone-

sia, specialize in producing extensive P.

monodon in Indonesia for exports. P.

monodon are larger in size and therefore

sell at prices that yield up to 33% EBIT

P. Monodon Cannot Be Intensified Beyond 60 PL per Square Meter

Stocking density Superintensive

Extensive Semi-intensive Intensive

per square meter or supraintensive

P. monodon 2 PL 5 to 20 PL 20 to 60 PL NA

L. vannamei 4 to 10 PL 10 to 30 PL 60 to 300 PL 300 to 750 PL

Disclaimer

Stocking densities depend on country specifics as well as farm characteristics; therefore,

wide ranges are provided

Sources: FAO; BCG analysis.

Note: PL = post-larvae shrimp; L. vannamei = Litopenaeus vannamei; P. monodon = Penaeus monodon. NA = not

applicable.

12 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in IndonesiaExhibit 3 | Indonesia’s Farmed-Shrimp Supply Chain

Feed mills Hatcheries Farmers Middlemen Processors Local markets International

Exporters retailers

Source: BCG analysis.

Note: This report focuses on feed mills, hatcheries, farmers, middlemen, and processors.

•• Middlemen. These intermediaries play a hatcheries, farms, processors, and export fa-

role between farmers and all other cilities. In addition to these fully integrated

segments of the value chain. Various small players, various midsize downstream play-

to large players exist. ers—such as Sekar Bumi and Bumi Menara

Internusa—own farms, processing and export

•• Processors. Generally, both the processing facilities, and, in some cases, hatcheries. Some

and the exporting are managed by one have a strong regional and species focus for

company. The market is highly fragmented exports. Alter Trade Indonesia (ATINA), for

with some large companies, such as CP example, supplies P. monodon to the Japa-

Prima, Sekar Bumi, and Japfa, but there nese market. Both fully integrated and down-

are also various midsize players, such as stream players often rely on middlemen to

KML Foods and Panca Mitra Multiperdana. secure a stable supply of shrimp.

Across the value chain, two fully integrated

players, CP Prima and Japfa, own feed mills,

Boston Consulting Group | 13INDONESIA

THE CASE FOR CHANGE

T he Indonesian shrimp industry is

currently in a strong competitive position

in the global market, but three market forces

this price difference to the farm gate, Indone-

sian farmers would barely make a profit.

are threatening its position: low-price com-

petitors, market demand and traceability Market Demand and Traceability

regulations, and an intensifying need to cope Regulations

with the high risk of disease and environmen- In 2018, the US expanded its Seafood Import

tal threats. (See Exhibit 4.) Monitoring Program (SIMP), which establish-

es reporting and record-keeping requirements

for seafood imports, to cover shrimp.

Low-Price Competitors

The global competition in the shrimp indus- Because the US is the most important export

try has increased sharply for L. vannamei in market for Indonesia, SIMP has had a major

recent years. India, in particular, has flooded impact on the Indonesian shrimp industry, es-

the market with low-price shrimp, and other pecially when the standards have been strictly

countries such as Vietnam and Ecuador, are enforced. SIMP will likely have a similarly neg-

expected to ramp up production as well. With ative impact for the Indian export market giv-

such a large supply of low-price shrimp avail- en India’s relatively low traceability standards.

able, prices will continue to decrease. Be-

cause of their relatively high production costs, In the wake of food safety scandals, China

Indonesian companies cannot compete with has also imposed stricter import regulations

countries such as India to sell shrimp at lower by passing new legislation and urging life-

prices. A change is needed. time bans for offending importers. Although

China is not a main export market for Indo-

Indonesia’s number-one market for shrimp is nesia, these moves exemplify the current

the US: 80% of L. vannamei exports are to the global trend toward increased traceability

US, as well as 47% of P. monodon exports. In- and health standards.

dia is currently the leading exporter of shrimp

to the US, claiming about 32% of the market The demand for traceability is fueled also by

and selling at significantly lower prices. a fast-growing niche market for sustainable

and traceable seafood—and some companies

If the prices of Indonesia’s US exports are beginning to capitalize on this trend. A

dropped to match India’s current prices and group of companies in Ecuador, for example,

Indonesia’s processors translated just 50% of established the Sustainable Shrimp Partner-

14 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in Indonesiaship to produce fully traceable shrimp while ies (MMAF) launched Aquacard, a traceabili-

improving social and environmental perfor- ty system, that aimed to help buyers trace

mance. As first movers act on this trend to- shrimp back to the farm where it was pro-

ward traceability, Indonesia finds itself in a duced. It is, however, unclear how much this

precarious position regarding its exports. It system is being enforced. A small number of

risks losing share in the global shrimp mar- companies are also getting their shrimp certi-

ket. Given its strong domestic market for fied through international certification bod-

farmed shrimp, the shift toward traceability ies, such as Best Aquaculture Practices, Aqua-

and sustainability affects Indonesia less than culture Stewardship Council, GlobalGAP, and

other Asian countries, but over time, it could British Retail Consortium, but only a small

have a devastating impact on Indonesia’s ex- percentage of shrimp in Indonesia is as-

port business. sumed to be truly certified, and some farms

have been accused of not fully complying

Some companies in Indonesia have started to with certification standards. (See the sidebar

make progress on traceability. In 2014, Indo- “Certifications: There Are No Shortcuts to

nesia’s Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisher- Full Traceability.”)

Exhibit 4 | The Case for Change Is Driven by Three Factors in Indonesia

Low-price competitors Market demand and High risk of disease and

traceability regulations environmental threats

Source: BCG analysis.

CERTIFICATIONS: THERE ARE NO SHORTCUTS TO FULL

TRACEABILITY

Retailers and producers, in collaboration Because no reliable alternative to these

with certification bodies, offer many certifications currently exists, many

certifications for seafood and shrimp consumers accept them as proof of

products. Many of these certifications sustainability and increasingly demand

can have positive impact on certain pro- labeled seafood. In 2016, about 14% of

duction and supply chain elements, but farmed and caught seafood was certified,

not all address environmental and social and this number is expected to climb by

issues within the farmed-shrimp value about 5% annually through 2025. A small

chain. proportion of customers will pay premiums

as high as 40% in specialty stores for

Furthermore, because the supply chain is shrimp certified as sustainably produced

so complex, it is nearly impossible to and fully traceable.

guarantee with 100% certainty that shrimp

producers adhere to certification standards. Certification standards and practices can

Ultimately, the lack of traceability of be problematic for the following reasons:

certified supply chains renders some

labeling untrustworthy and provides •• Certification standards vary, and each

“perceived” rather than actual sustainabili- certifying organization establishes its

ty and responsibly produced shrimp. own minimum and maximum limits for

Boston Consulting Group | 15CERTIFICATIONS: THERE ARE NO SHORTCUTS TO FULL

TRACEABILITY (continued)

such concerns as antibiotics and chemi- •• It is nearly impossible to compare one

cals, land use, and water pollution. And protein product—shrimp, fish, or

many fail to differentiate between meat—with another protein product,

essential and innocuous requirements. because certifications differ so much,

depending on species.

•• Shrimp farm certifications are not nec-

essarily product certifications. They are, •• Shrimp from certified farms and

instead, focused on farming processes. noncertified farms are, in many cases,

collected from a single middleman and

•• Controls and audits on farms and at mixed in a single batch, making it

processing factories occur infrequent- impossible to separate the sustainably

ly—at most twice a year. Furthermore, produced shrimp from nonsustainably

only a subset of farms are checked and produced shrimp.

audited in farm collectives, and there is

no mechanism for confirming that all Certifications aim to provide transparency

farms within a collective adhere to the on sustainability and production standards,

stated standards. Even for those that but implementation is close to impossible

are controlled, only one day’s evidence in Indonesia’s fragmented shrimp supply

is collected, and neither farming chain. To achieve reliable traceability, all

practices nor impacts are monitored players must participate and provide

over an extended period. continuous transparency into their produc-

tion methods and inputs. This can be

•• Many certifications have been awarded achieved only with collaboration, constant

before traceability has been demon- monitoring, and a platform that captures

strated. tamper-free, truthful records. There are no

shortcuts to traceability, and as previously

•• In many cases, the cost of adhering to stated, what has worked for Indonesia’s

certification standards and altering shrimp industry in the past—providing

production processes is not shared along certified products without proof of trace-

the supply chain, burdening only farms or ability—will not work for much longer.

processors. From a social-equality More holistic approaches to supply chain

perspective, this represents a major pitfall. integrity are necessary.

For a number of reasons, including the •• In 2019, the US announced the end of its

three given below, it’s important for Indone- preferential trade agreement with India.

sia to shift toward traceability and sustain- This means that Indian shrimp could be

ability now: subject to new duties.

•• Indonesia has earned a reputation as a •• By increasing sustainability standards

reliable shrimp source. From March 2014 within the supply chain, the Indonesian

through March 2019, only 71 entry lines shrimp industry can tap into a new

were rejected at the US border. By contrast, market, build an even stronger competi-

during the same period, 396 entry lines tive position, and become a leader in this

from India were rejected. segment in the US.

Countries that fail to meet regulatory Other markets in which Indonesia has not

requirements face serious and lasting yet established a strong position might be

repercussions.Adherence, therefore, is more difficult to penetrate, but the US

critical. provides an immediate opportunity.

16 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in IndonesiaHigh Risk of Disease and have already begun to develop suprainten-

Environmental Threats sive ponds lined with cement that are more

Extreme weather events and outbreaks of dis- resistant to environmental threats. They are

eases can dramatically disrupt shrimp pro- also using a central drain to dump shrimp

duction. These risks are expected to increase waste, excess food, and other waste that accu-

in frequency and severity, particularly in re- mulates at the bottom of the pond. This ap-

gions such as Jawa Timur and Kalimantan proach allows for higher stocking densities

Timur, due to climate change and ongoing and less wastewater discharge, and it reduces

mangrove deforestation. Environmentally risk from environmental hazards. However, as

harmful shrimp-farming practices also con- the ponds are still constructed outdoors, dis-

tribute to the problem. Lack of water treat- ease can spread, and complete control over

ment, for example, leads to eutrophication, water conditions is not possible.

diffusion of antibiotics, spread of disease, and

ultimately the destruction of coastal areas, Indonesia could increase its competitive posi-

biodiversity loss, groundwater depletion, land tion in the global shrimp supply chain by

degradation, and erosion. shifting to more sustainable and environmen-

tally sound production. New production meth-

There is a strong financial incentive for farm- ods will lead to higher margins and also open

ers to become more resilient. For an intensive up a sustainable niche market for producers.

L. vannamei farm, a natural disaster could However, immediate changes on the farm and

lead to crop losses totaling $31,700 per crop processing levels will not be sufficient. The in-

per hectare.3 dustry must improve sustainability and trace-

ability across the whole supply chain to truly

To mitigate risk and build resilience, farmers tackle the challenges the industry is currently

need to protect their farms from changing facing. (See the sidebar, “Unlocking the Eco-

weather conditions and reduce their environ- nomic Potential of Mangroves.”)

mental footprint. Some Indonesian farmers

UNLOCKING THE ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF MANGROVES

P. monodon has traditionally been farmed •• Poor Water Quality. Although shrimp

in mangrove areas, shrimp’s natural farming requires low acidity, soils in man-

habitat, but this practice is threatening grove areas are highly organic with a high

Indonesia’s mangrove forests, which are acid sulfate potential and low pH levels.

crucial carbon storage ecosystems. As

shrimp farming has intensified, it •• High Stress Levels That Result in

has become evident that mangrove High Risk of Disease. Low pH levels

areas are not ideal for the following stress shrimp and can reduce pond

reasons: water nutrients, leading to serious

health threats.

•• Unfavorable Pond Construction. Low

sea levels prevent construction of •• Higher Overall Costs. Construction

deep ponds and complete drainage of and production costs are generally

used water during and after farming higher, as farmers must take measures

cycles. to improve water quality and mitigate

soil degradation.

•• Poor Soil Quality. Soil used for

constructing embankments as natural For these reasons, it is not unusual for

barriers between the pond and the shrimp farms in mangrove areas to suffer

surrounding environment tends to low yields and productivity, and, therefore,

degrade over time, so the embank- shrimp farming in mangrove areas is not

ments can eventually breach. recommended.

Boston Consulting Group | 17UNLOCKING THE ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF MANGROVES

(continued)

Nevertheless, local communities and forests protect coasts, impede erosion,

shrimp farmers continue to destroy prevent seawater intrusion, and are the

mangrove forests to build ponds for natural habitats of many plants and animals.

aquaculture. Historically, aquaculture has They also reduce the occurrence and severity

been responsible for around 50% of of natural disasters. In addition, they are

mangrove deforestation in Indonesia, and considered to be the largest carbon storage

in some regions, this destruction continues, ecosystems in the world, storing three times

mainly as a result of extensive P. monodon more carbon—about 940 tons of carbon per

shrimp production. From 2014 through hectare—than boreal, temperate, and tropical

2018, around 28,000 hectares of mangrove forests, which store about 300 tons of carbon

area were converted to pond aquaculture. per hectare. Owing to their many benefits,

mangroves generate a societal and environ-

The latest research suggests that mangrove mental value of $4,000 to $8,000 per hectare

deforestation in Indonesia has halted or even per year, and the value of carbon sequestra-

reversed over the past few years. Indonesia’s tion can be directly monetized through

mangrove area increased 6% overall from carbon offsets. (See the exhibit “Mangrove

2014 through 2018. But mangrove deforesta- Areas Provide Substantial Value.”)

tion continues to be a problem in certain

regions. In Kalimantan Timur, mangrove cover Mangrove Reforestation: A Business

dropped 5% between 2014 and 2018. Opportunity

The growing trend to engage in carbon

Indonesia is home to approximately 17% of offsets could generate new economic

the world’s mangrove forests—approximately opportunities. Farmers can generate

3 million hectares as of 2018, which is roughly income by earning certifications, such as

the size of the US state of Vermont. Mangrove Verified Carbon Standard and Gold Stan-

Mangrove Areas Provide Substantial Value

Net use value per hectare per year ($)

Direct value Indirect value

4,147 to

694 to 8,020

3,767 277

2,292

800 to

1,600

36 48

Fisheries Forestry Carbon Provision of Coastline Seawater intrusion Total value

sequestration nursery grounds protection prevention

Sources: Forests, 2015; Biodiversity International Journal, 2018; BCG analysis.

18 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in IndonesiaUNLOCKING THE ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF MANGROVES

(continued)

dard, and receive funding per ton of carbon In addition, regulators may include REDD+

dioxide storage. projects in their offset programs, such as

the EU Emissions Trading System and the

With carbon certification, the direct net California cap-and-trade program.2 Approxi-

present value (NPV) of intact mangrove mately 240 REDD+ projects—including

forests can be up to 20% higher than the Afforestation, Reforestation, and Revegeta-

NPV for extensive shrimp farming in tion and Improved Forest Management—

mangrove areas. (See the exhibit “The Value were certified in Asia, South America, Africa,

of Intact Mangroves Is 20% Higher Than and Oceania, and this number is expected

Extensive P. Monodon Farming.”) to grow. Over their lifetime, these 240 proj-

ects are expected to reduce emissions by

In addition, the payback period for reforesta- some 2.2 billion metric tons of carbon

tion projects is 2.7 to 3.4 years, which means dioxide, which, based on 2016 emissions, is

that intact mangroves and mangrove around four times as much as Indonesia

reforestation are better economic alterna- emits annually. Other certification bodies,

tives for shrimp farmers, even in the short such as myclimate and Natural Capital

term. Still, the certification process remains Partners, support smaller-scale projects for

complicated and costly. individuals’ or companies’ voluntary offsets.

The Carbon Offset Trend The current carbon offset trend gives

There are various reasons for funding carbon shrimp farmers an economically viable

offsets. Many of the international certificates alternative to deforestation and funds refor-

comply with the Reducing Emissions from estation projects. Carbon offsets should be

Deforestation and Forest Degradation promoted by large processing companies,

(REDD+) standard, and countries can use NGOs, and local communities to raise

the certifications to comply with their awareness and unlock the full economic

Nationally Determined Contributions under potential of mangrove forests.

the Paris Agreement of 2015.1

The Value of Intact Mangroves Is 20% Higher Than Extensive P. Monodon Farming

NPV per hectare ($)

25,500 to

50,500

Direct 5,500 to

value 10,500

~20% • Assumptions based on Through the use

shrimp farming in South of carbon credits,

Sulawesi, Indonesia the value of the

20,000 to

Indirect 40,000

6,000 to

• Assumes an interest rate of

preservation of

7,600 mangroves is

value 10% over ten years

superior to that

• Value declines in shrimp of short-term

farming after five years focused

NPV NPV extensive owing to increased disease aquaculture

shrimp farming risk and lower yields

Sources: Forests, 2015; Biodiversity International Journal, 2018; BCG analysis.

Note: NPV = net present value; NPV is for a ten-year period. NPV extensive shrimp farming refers to extensive

aquaculture in Indonesia

Sources: Forests, and assumes

2015; Biodiversity losses ofJournal,

International 0% to 50%

2018;per

BCGyear since year five.

analysis.

Boston Consulting Group | 19UNLOCKING THE ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF MANGROVES

(continued)

Notes 2. Emissions-trading schemes set a maximum

1. The Paris Agreement brought together all nations allowance for total greenhouse gasses and issue

to combat climate change and adapt to its effects. It specific shares—auctioned or allocated for free—to

requires countries to commit to emissions reduction all participants. If emissions exceed allowances,

targets—the so-called Nationally Determined participants must purchase additional allowances.

Contributions—in the coming years. So far, 185

parties out of 197 have ratified the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change.

20 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in IndonesiaINDONESIA’S PRODUCERS

CAN CREATE IMMEDIATE

ECONOMIC VALUE

T hree imperatives inform the future Feed Mills: Increase Profit

of Indonesia’s farmed shrimp: pursue Margins and Diversify the

immediate change to alter current practices Portfolio with Functional Feed

on an individual level, increasing efficiency The feed market in Indonesia is expected to

and productivity while improving profit grow at 8% per year through 2022, in line

margins; collaborate to achieve product with Indonesia’s overall shrimp market. The

traceability; and make bold shifts toward shrimp probiotics market, which helps farm-

indoor shrimp farming by investing in ers increase shrimp growth and survival rates,

closed-containment indoor facilities de- is expected to grow at 9% per year through

signed to reduce contamination, increase 2020. This growth illustrates the demand

output, minimize the environmental foot- from farmers for food additives or new food

print, and improve accountability. (See formulas. Feed mills have an opportunity to

Exhibit 5.) respond to the growing demand by expand-

ing their portfolios to include functional

The shift to traceability, transparency, and feed—basic feed that has been enhanced

indoor farming offers the highest potential with additives, such as proteins, vitamins, or

for successfully defending the currently probiotics (but never antibiotics), to achieve a

strong competitive position of Indonesia’s specific outcome. It is not uncommon for feed

shrimp industry, but this will require consid- mills to improve basic feed with additives,

erable capital investment, extensive exper- but functional feed is slightly different from

tise, and time. improved basic feed: it is used in specific cir-

cumstances to achieve a specific outcome,

In the meantime, there are several immediate usually includes more additives, and is there-

changes that actors along the value chain, fore defined as its own feed category.

particularly feed mills and farmers, can im-

plement to significantly improve financial Two types of functional feed have high po-

performance and resource efficiency and cre- tential.

ate environmental benefits.

Growth Enhancement Functional Feed. This

In this section, we briefly review the several is used to increase shrimp growth rates and

ways that each player in Indonesia’s farmed- allow farmers to sell larger shrimp at a

shrimp value chain can benefit from these potentially higher price or to accelerate

short-term improvements. (See Exhibits 6 growth cycles and, therefore, farm through-

and 7.) put. It offers a positive business case for feed

Boston Consulting Group | 21Exhibit 5 | Several Levers Can Maximize Business Success While Creating Positive

Environmental and Social Impact

Lowest

Immediate short-term changes Levers for short-term changes

Act on single levers and implement

step-by-step changes 1 Improved feed use

Innovative feeds to boost productivity and

reduce environmental impact

Integrated player

Implement multiple short-term changes 2 Improved water treatment

at once Reduced freshwater use and pollution while

Impact

improving efficiencies

Supply chain collaboration through 3 Improved clean energy use

Reduction of carbon footprint and access to

traceability reliable, cheaper energy sources than diesel

Fully traceable and transparent supply generators

chains

Improved health

Highest

No chemical or drug use to increase shrimp

Sustainable intensification health and to prevent entry line refusals

Significant industry shift to superintensive

indoor shrimp farming Improved social issues

Social equality and adherence to international

labor standards

Source: BCG analysis.

Note: Our focus in on levers 1, 2, and 3.

mills, potentially increasing EBIT margins by feed from the market: farmers will likely pur-

a factor of up to about 2.6 per kilogram of chase the expensive feed only when there’s a

shrimp feed sold. This increase in profitability direct economic benefit, such as when global

is achieved by charging a premium of as shrimp prices rise significantly. It does offer a

much as 20%, offsetting the additional good opportunity for feed mills to diversify

production costs. their portfolios, boost revenues, and improve

profit margins, but a complete shift is not rec-

However, when farmers invest in growth en- ommended. To attain these benefits, it is im-

hancement functional feed, their feed conver- portant that feed mills market functional

sion ratio (FCR) is drastically reduced.4 The feed and educate farmers on its benefits. (See

immediate demand for feed may drop, reduc- the Appendix for a discussion of growth en-

ing revenues by up to 8% per kilogram of hancement and health enhancement func-

shrimp produced, but this decline can be off- tional feed.)

set by other factors, including the ability to

charge higher prices for functional feed and Feed mills that extend their product portfolio

an overall uptick in demand for feed (as by selling functional feed can increase profits,

shrimp grow faster and demand increases). help farmers increase production volumes,

and support growth within the shrimp indus-

Health Enhancement Functional Feed. This try as a whole. They have both a clear incen-

type of feed can enhance shrimp health and tive and a responsibility to act. Switching to

disease resistance, and it also offers several functional feed also benefits the environment

benefits for feed mills, not the least of which by decreasing land use—as a result of re-

is that feed mills can charge premiums of up duced FCR—by up to 15% per kilogram of

to 50%, leading to profit margins that could shrimp produced, improving water quality by

be more than four times higher than average reducing feed waste, decreasing the use of an-

in an optimal case. Production and feed tibiotics, and requiring less fish meal and fish

ingredient costs will likely increase by 10% to oil. However, these benefits materialize only

20%, but these costs are typically offset by the if functional feed is widely used, and the pos-

revenue boost. itive environmental impact depends on what

substitutes are used for fish meal.

It is fair to assume that the demand for func-

tional feed will increase in the years to come, Feed mills are responsible also for careful

but it will not completely displace regular consideration of the production of the feed’s

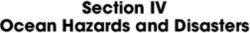

22 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in IndonesiaExhibit 6 | Current Average Economics per Value Chain Step

Feed mills Hatcheries Farmers Middlemen Processors Local National

market retailers

Exporters International

retailers

$0.84 $2,680 $3.17 $8.49

Costs per kilogram per million PL per kilogram per kilogram of shrimp

of feed of shrimp

L. vannamei

$0.90 $3,190 $3.75 $8.89

Price per kilogram per million PL per kilogram per kilogram of shrimp

of feed of shrimp

EBIT

~7 ~16 ~16 ~2 to 7 ~5

margins %

$0.84 $1,400 $3.50 $11.88

Costs per kilogram per million PL per kilogram per kilogram of shrimp

of feed of shrimp

P. monodon

$0.90 $1,700 $5.20 $13.00

Price per kilogram per million PL per kilogram per kilogram of shrimp

of feed of shrimp

EBIT

~7 ~18 ~33 ~5 to 12 ~9

margins %

Source: BCG analysis.

Note: L. vannamei = Litopenaeus vannamei; P. monodon = Penaeus monodon; PL = post-larvae shrimp. Calculations for L. vannamei are based

on large-scale players and shrimp averaging around 60 pieces per kilogram; calculations for P. monodon are based on small-scale players (except

feed) with prices based on shrimp averaging around 40 pieces per kilogram; margins include considerations such as survival rate. Rounding errors

are possible.

ingredients. Worldwide, the demand for fish could have far-reaching impact beyond the

meal in shrimp feed has led to the depletion shrimp supply chain.

of some wild-capture fisheries and, in some

cases, serious human and labor rights abuses The industry is also working to develop feed

on fishing vessels. Similarly, the cultivation of production methods, such as extrusion (cook-

plant ingredients such as soy and corn for ing under high temperature and processing

shrimp feed creates a high burden on land under high pressure) and the manufacture of

use. The natural resources used in feed—so- pelleted feeds (no cooking and processing un-

called embodied resources—represent a hid- der much less pressure). Both of these ap-

den, but vitally important, depletion of re- proaches have the potential to improve the

sources and thus need to be considered digestibility of feed ingredients.

carefully.

Some feed mills and raw-material suppliers Hatcheries: Ensure the Quality of

are experimenting with fish meal and soy- Post-Larvae Shrimp Through

bean meal replacements, using, for example, Selective Breeding

alternative and less resource-intensive ingre- PL produced by hatcheries are critically im-

dients such as marine microbes. At the same portant for farmers. High-quality PL produc-

time, some companies are experimenting tion can improve grow-out farm survival rates

with black soldier fly larvae, an efficient bio- as well as the quality and health of shrimp,

convertor and a valuable feeding resource. ultimately benefiting the entire industry.

Once applied at large scale, these innovations Hence, hatcheries represent a crucial enabler.

Boston Consulting Group | 23Exhibit 7 | The Economics of Short-Term Improvements

Status quo Feed Water Combination

Growth enhancement Growth enhancement

EBIT margin: Increase: with biofloc

EBIT margin: None EBIT margin: Increase:

Up to 18% 157%

~7% Up to 18% 157%

Feed In the sale of functional

feed, overall feed mill

mill level Health enhancement

EBIT margins depend Potential revenue loss

EBIT margin: Increase: on the feed portfolio of through improved farm

individual farms efficiency, with a similar

Up to 28% 300% increase in farming output

Growth enhancement Biofloc Growth enhancement with

biofloc and energy

EBIT margin: EBIT margin: Increase: EBIT margin: Increase:

Positive, but further

~16% Up to 23% 46% Up to 21% 34% studies are required

Farm

level Health Growth enhancement with

enhancement RAS RAS and energy

EBIT margin of up to 17% even EBIT margin: Increase: EBIT margin: Increase:

during disease outbreaks

versus 2% with basic feed Up to 25% 64% Up to 33% 106%

Source: BCG analysis.

Note: EBIT margin is based on feed per kilogram sold. RAS = recirculating aquaculture systems. Rounding errors are possible.

Many hatcheries still rely on imported brood- duce production costs and increase output at

stock, although domestic broodstock and se- the farm level.

lective breeding techniques ensure better

shrimp survival, reduce the risk of disease, Although our analysis did not reveal many

and position hatcheries to focus on breeding opportunities for hatcheries to implement

PL that grow faster and larger. Nonetheless, short-term changes in feeding techniques or

because it is considered to be of better quali- water treatment systems, hatcheries that of-

ty than Indonesian broodstock, many hatch- fer high-quality PL with benefits such as SPF

eries purchase imported broodstock. Through can charge premiums for their products. Pri-

further R&D, a shift to domestic broodstock ma Aquatics and Global Gen are examples of

can help the Indonesian shrimp industry be- Indonesian hatcheries that initiated SPF

come more independent and significantly re- breeding programs.

duce the potential spread of diseases from

foreign countries. Individual hatcheries should focus on improv-

ing quality by domesticating broodstock and

For example, after outbreaks of diseases in implementing selective breeding practices to

the late 1980s and early 1990s, hatcheries help minimize the risk of disease and allow

successfully produced a specific pathogen- them to compete more effectively against

free (SPF) broodstock to make shrimp more the significant market power of integrated

disease resistant. Moreover, recent studies players.

have shown that SPF lines of selected stocks

maintained under the proper conditions can Because developing better PL involves genet-

help reestablish farm populations even in the ic testing and investments in R&D, implemen-

event of stock losses caused by the outbreak tation might be rather difficult for small

of disease. In providing high-quality and hatcheries. Institutions and players with the

healthy PL, hatcheries significantly help re- necessary means should, therefore, support

24 | A Strategic Approach to Sustainable Shrimp Production in IndonesiaYou can also read