Blood pressure change with weight loss is affected by diet type in men1-3

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Blood pressure change with weight loss is affected by diet

type in men1–3

Caryl A Nowson, Anthony Worsley, Claire Margerison, Michelle K Jorna, Sandra J Godfrey, and Alison Booth

ABSTRACT hypertension in whites (6). Dietary sodium increases blood pres-

Background: Weight loss reduces blood pressure, and the Dietary sure (BP), whereas dietary potassium lowers the risk of hyper-

Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet has also been shown tension and stroke. In a controlled intervention study, a multi-

to lower blood pressure. faceted dietary approach (DASH: Dietary Approaches to Stop

Objective: Our goal was to assess the effect on blood pressure of 2 Hypertension) that included a diet high in fruit, vegetables, and

weight-reduction diets: a low-fat diet (LF diet) and a moderate-sodium, low-fat dairy products was shown to result in large decreases in

high-potassium, high-calcium, low-fat DASH diet (WELL diet). BP (11 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic pressure in

Design: After baseline measurements, 63 men were randomly as- hypertensive persons and 5 mm Hg systolic and 3 mm Hg dia-

signed to either the WELL or the LF diet for 12 wk, and both diet stolic in normotensive persons) (7). Therefore, the aim of the

groups undertook 0.5 h of moderate physical activity on most days present study was to determine the effect on BP of a DASH-type

of the week. weight-loss diet (WELL diet) and to compare this with usual

Results: Fifty-four men completed the study. Their mean (앐SD) age low-fat dietary advice (LF diet) in free-living individuals who

was 47.9 앐 9.3 y (WELL diet, n ҃ 27; LF diet, n ҃ 27), and their selected and prepared their own food.

mean baseline home systolic and diastolic blood pressures were

129.4 앐 11.3 and 80.6 앐 8.6 mm Hg, respectively. Body weight

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

decreased by 4.9 앐 0.6 kg (앐SEM) in the WELL group and by 4.6 앐

0.6 kg in the LF group (P 쏝 0.001 for both). There was a greater Subjects

decrease in blood pressure in the WELL group than in the LF group

Subjects were recruited through newspaper articles advertis-

[between-group difference (week 12 – baseline) in both SBP (5.5 앐

ing the study and at BP measurement sessions provided in work-

1.9 mm Hg; P ҃ 0.006) and DBP (4.4 앐 1.2 mm Hg; P ҃ 0.001)].

places and at the study center. Subjects were eligible if they were

Conclusions: For a comparable 5-kg weight loss, a diet high in

male, aged 쏜 25 y, and had a seated office BP of 욷120 mm Hg

low-fat dairy products, vegetables, and fruit (the WELL diet) re-

systolic blood pressure (SBP) or 욷80 mm Hg diastolic blood

sulted in a greater decrease in blood pressure than did the LF diet.

pressure (DBP) at their first visit (mean of the last 3 of 4 mea-

This dietary approach to achieving weight reduction may confer an

surements taken at 1-min intervals). Subjects who were taking

additional benefit in reducing blood pressure in those who are

antihypertensive medication were included, provided they were

overweight. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:983–9.

willing to maintain their current medication level. Subjects were

excluded if they had experienced a cardiovascular event in the

KEY WORDS Weight loss, blood pressure, diet, potassium,

past 6 mo, had insulin-dependent diabetes, were taking medica-

calcium

tions such as warfarin or phenytoin, ate their main meal outside

the home more than twice per week, drank 쏜30 standard (10 g

alcohol) alcoholic drinks per week, were planning to change

INTRODUCTION smoking habits, or were unwilling to cease taking dietary sup-

Hypertension is an important public health issue and contrib- plements (including vitamins). Subjects were included if they

utes to the incidence of stroke and coronary heart disease (1). The had a body mass index (BMI; in kg/m2) between 25 and 35. All

prevalence of hypertension in Australia was recently shown to be subjects provided written informed consent before starting the

앒29% (2). Furthermore, hypertension accounts for 6.1% of the study, which was approved by the Deakin University Human

total problems managed in general practice (3). Education per- Research Ethics Committee.

taining to nutrition and weight accounted for 10% of all non-

1

pharmacologic treatments provided by general practitioners and From the Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition, School of Exercise

was one of the 3 most common forms of advice (3). Around the and Nutrition Sciences, Deakin University, Burwood Highway, Burwood,

world, the incidence of overweight and obesity has increased (4). Australia.

2

Supported by the Dairy Research and Development Corporation.

The prevalence of obesity in Australia has more than doubled in 3

Address reprint requests to CA Nowson, School of Exercise and Nutri-

the past 20 y, and almost 60% of adults have been estimated to be

tion Sciences, Deakin University, 221 Burwood Highway, Burwood, VIC

overweight or obese (5). There is a direct positive relation be- 3125 Australia. E-mail: nowson@deakin.edu.au.

tween overweight and hypertension, such that it has been esti- Received June 29, 2004.

mated that the control of obesity may eliminate 48% of the Accepted for publication December 14, 2004.

Am J Clin Nutr 2005;81:983–9. Printed in USA. © 2005 American Society for Clinical Nutrition 983984 NOWSON ET AL

Two hundred twenty persons responded to advertisements, Dietary instruction

and 165 of these were sent a screening questionnaire and invited Dietary counseling was overseen by the coordinating dietitian

to attend further screening. Ninety-four men attended one screen- (CM) and was provided by trained research staff. The WELL diet

ing appointment, and 63 who met the entry criteria and wished to was based on our previous OZDASH diet (9), which had been

participate undertook baseline home BP measurements for 2 wk and modified from the US DASH diet (7). This diet included advice

were then randomly assigned to either the LF or the WELL diet. to consume 욷4 servings of fruit or fruit juice [1 serving ҃ 1

medium piece of fruit (100 g) or fruit juice (200 mL)], 욷4 serv-

Study design

ings of vegetables [1 serving ҃ 0.5 cup cooked vegetables (50 g),

Subjects were seen twice at baseline, and commenced a 12-wk 1 cup salad vegetables, or 1 medium potato] and 욷3 servings

intervention study and were seen at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12. Phone of nonfat dairy products [1 serving ҃ milk (200 mL), yogurt

contact was made with the subjects at weeks 6 and 10. Clinical (200 g), or cottage or ricotta cheese (0.5 cup)] per day. Fish (1

BP, height, and weight were measured at baseline. Subjects mon- serving ҃ 120 g cooked) was to be consumed 욷3 times per week,

itored their home BP daily for 2 wk before being randomly legumes (1 serving ҃ 1 cup cooked) at least once per week, and

assigned (stratified by antihypertensive medication use) to 1 of unsalted nuts and seeds (1 serving ҃ 30 g) 4 times per week. Red

the 2 diets. Randomization was performed by the chief investi- meat was restricted to no more than 2 servings (1 serving ҃

gator (CAN) with the use of a random number generator in blocks 90 –100 g cooked) per week and fat to a maximum of 4 servings

of 8 (EXCEL 2000; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). (4 teaspoons) per day. Subjects were advised to avoid butter,

added salt (table or cooking), and obviously salty foods and to use

Anthropometry and blood pressure measurement lower-salt (쏝380 mg Na per 100 g) mono- or polyunsaturated

Height was measured with a wall-mounted stadiometer. Body margarine. Those in the WELL group received a detailed dietary

weight was measured at each visit on a digital scale while the information booklet, recipes, and simple advice (tips).

subjects wore light clothing and no shoes. Waist circumference The LF group was advised to limit their intake of high-energy

was measured with a fiberglass tape measure anteriorly halfway foods and drinks, reduce their saturated fat intake, choose mainly

between the lowest lateral portion of the ribcage and the iliac plant-based foods, consume nonfat or reduced-fat milk and yo-

crest. Home BP was measured on the left arm with the use of an gurt, limit their cheese and ice cream intake to twice per week,

automated BP monitor (AND UA-767-PC; A&D Co Ltd, Tokyo, select lean meat, and avoid frying foods in fat. No specific targets

Japan). Subjects were trained to correctly apply the cuff and were were set. The “Healthy Weight Guide” booklet by the National

instructed to take their BP measurements alone, at the same time Heart Foundation of Australia (2002) was provided, together

of day, after 5 min of rest in a quiet room and to take 3 measure- with the same recipes and tips as received by the WELL group.

ments with 1 min in between (the mean of the last 2 measure- A maximum of 4 caffeine-containing drinks per day (eg, cola

ments taken each day was used in the analysis). BP measurement drinks, coffee, and tea) and 4 standard (10-g alcohol) alcoholic

data were downloaded directly to a computer by the study staff at drinks per week were permitted for both diet groups.

the end of each fortnight. Several incentives were included. Both groups received mea-

suring cups and spoons and individual feedback on their daily

Biochemical indexes intake of fruit and vegetables. Those in the WELL group also

Fasting (10 h overnight) blood samples were collected at base- received individual feedback compared with the specified diet

line and at the end of the study. Serum total cholesterol, HDL targets (fruit, vegetables, and dairy). A dairy product of their

cholesterol, and triacylglycerol were measured on the Hitachi choice [eg, 200-mL tub of nonfat yogurt or a packet of reduced-

704 analyzer by using enzymatic reagents (Boehringer, Mann- fat (쏝15% fat) cheese slices] was offered once during the study

heim, Germany). LDL cholesterol was calculated by use of the to all subjects. Subjects could also participate in a drawing to win

Friedewald equation (8). a double movie pass, and feedback on the group’s progression

regarding targets and weight loss was provided graphically

Dietary assessment throughout the study.

The main difference between the LF diet and the WELL diet

Subjects completed a 24-h dietary record each fortnight on the

was that the WELL diet had specified targets for fruit, vegetable,

day before their visit with study staff. Trained research personnel

and dairy intake, whereas the LF diet provided general guidelines

checked this record. Dietary information was entered into a di-

focusing on increasing fruit and vegetable intake and reducing fat

etary analysis program (FOODWORKS, Professional Edition,

intake, particularly saturated fat.

version 3.02; Xyris Software, New York, NY) to calculate daily

nutrient intakes. The mean of two 24-h records at baseline and the

mean of four 24-h records at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 of the inter- Physical activity

vention were used in the analysis. A food-frequency question- All subjects were required to participate in moderate-intensity

naire was completed at baseline and at week 12 to assess usual exercise for 욷30 min on all or most days of the week. The “Be

intake of fruit, vegetables, and dairy products. Active Every Day” booklet by the National Heart Foundation

(1999) was given to each participant, and individual exercise

Lifestyle intervention goals were set at each visit. Information was provided on calcu-

Subjects were assisted with setting goals for exercise and diet. lating maximum heart rate [220 –age (y)], and subjects were

At each visit, a trained dietitian set dietary and exercise goals (욷3 advised to increase their heart rate to 60 –79% of their maximum

goals per visit, including 욷1 for exercise and 욷1 for diet). Rec- heart rate to reach a moderate level of exercise intensity and to

ipes, educational materials (diet and exercise), and tips to en- maintain this for 욷30 min for each session. The amount of

courage compliance were provided to all subjects. walking was monitored by using the CHAMPS questionnaireDIET, WEIGHT LOSS, AND BLOOD PRESSURE 985

(10) at baseline (for 4 wk) and the average hours per week TABLE 1

calculated for the intervention period. Baseline characteristics of the study groups1

WELL diet group LF diet group

Statistical analysis (n ҃ 27) (n ҃ 27)

Data were analyzed by using SPSS for WINDOWS (version Age (y) 47.1 앐 10.32 48.8 앐 8.3

11.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) to calculate the descriptive statistics Age range (y) 30–66 28–64

and perform the regression analysis. Mean home BP readings Height (cm) 172.5 앐 5.2 177.4 앐 5.33

were calculated for each 2-wk period. Unpaired Student’s t tests BMI (kg/m2) 29.6 앐 2.3 31.2 앐 2.44

were used to evaluate the difference between the LF and WELL Waist circumference (cm) 102.8 앐 7.7 110.3 앐 6.75

diets in the changes between baseline and the last visit. P values Office SBP (mm Hg) 136.4 앐 16.2 133.6 앐 9.7

of 0.05 were considered to be significant. Additionally, the effect Office DBP (mm Hg) 88.0 앐 9.7 88.7 앐 6.0

Office pulse (beats/min) 69.3 앐 12.3 73.2 앐 9.9

of the diet intervention was assessed by using two-factor

repeated-measures analysis of variance (diet ҂ time) with co- 1

WELL, DASH-type weight-loss diet (moderate sodium, high potas-

variates of baseline weight and BP included in specific analysis sium, high calcium, low fat, with less red meat and more fish); LF, low-fat

where indicated. Baseline values were used as covariates in GLM diet; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

univariate analysis of variance to calculate the adjusted mean

2

x 앐 SD (all such values).

3–5

Significantly different from the WELL diet group (unpaired t test):

changes to test for the difference between groups for the dietary 3

P 쏝 0.01, 4P 쏝 0.05, 5P 쏝 0.001.

data only.

For the WELL group only, intakes of dairy products and vege-

RESULTS

tables were significantly higher during the diet than at baseline

Nine subjects dropped out before completing the study (4 in (dairy P ҃ 0.001, vegetables P ҃ 0.001; Table 3).

the LF group and 5 in the WELL group); the subjects who After adjustment for baseline dietary intake, the 24-h dietary

dropped out did not differ significantly from the rest of the group records indicated that the reductions in dietary fat (g/d), saturated

with respect to age or BMI. Eight found it too difficult to comply fat (g/d), percent of energy from fat, percent of energy from

with the study demands, and one moved interstate. saturated fat, and sodium (mg/d) were greater in the WELL group

Of the 54 men who completed the study, 18 were taking an- than in the LF group, and the increases in the percent of energy

tihypertensive medications (9 WELL, 9 LF). Subjects in the from protein, percent of energy from carbohydrate, potassium

WELL group who were receiving antihypertensive therapy in- (mg/d), calcium (mg/d), magnesium (mg/d), and phosphorus

cluded 4 receiving single therapy [1 taking an angiotensin- (mg/d) were greater in the WELL group than in the LF group

converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, 1 taking a calcium-channel (Table 3).

blocker, and 2 taking angiotensin II receptor antagonists (AT1)]

and 5 receiving combination therapy (AT1 ѿ -blocker, n ҃ 1; Weight and blood pressure changes

AT1 ѿ diuretic, n ҃ 2; AT1 ѿ calcium-channel blocker, n ҃ 1; Weight decreased significantly in both groups by 앒5.0 kg

ACE inhibitor ѿ diuretic, n ҃ 1). Subjects in the LF group who (P 쏝 0.001 for both), with subjects in the WELL group losing 6%

were receiving antihypertensive therapy included 5 receiving single of body weight (P 쏝 0.001) and those in the LF group losing 5%

therapy (2 taking an ACE inhibitor, 1 taking an AT1, and 2 taking (P 쏝 0.001; Table 2). The rate of weight loss was not signifi-

calcium-channel blockers) and 4 receiving combination therapy cantly different between the diet groups throughout the study. In

(ACE inhibitor ѿ diuretic, n ҃ 1; AT1 ѿ diuretic, n ҃ 1; ACE the first 2 wk, weight loss was 1.2 앐 0.2 kg in the WELL group

inhibitor ѿ diuretic, n ҃ 1; AT1 ѿ diuretic ѿ -blocker, n ҃ 1). and 1.5 앐 0.2 kg in the LF group, and the effect did not differ

At baseline, there were no significant differences in dietary significantly between diet groups (two-factor ANOVA: time ҂

intakes of fruit, vegetables, or calcium-containing dairy products diet effect, NS).

between groups; however, those randomly assigned to the LF The greatest decrease in BP in both groups was seen after 4 wk

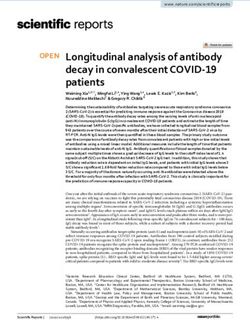

group were heavier, were taller, and had a greater waist mea- of intervention (Figure 1). There was a greater decrease in the

surement and had a BMI of 31 compared with 30 for the WELL WELL group than in the LF group [between-group difference

group (Table 1 and Table 2). (week 12 – baseline) in both SBP (5.5 앐 1.9 mm Hg; P ҃ 0.006)

and DBP (4.4 앐 1.2 mm Hg; P ҃ 0.001)]. Pulse rate also fell by

Effects of the intervention 3.8 앐 1.6 beats/min more in the WELL group (P ҃ 0.023; Table 2).

The amount of time spent walking increased in both groups The percentage decrease in SBP was 5.5 앐 1.0% in the WELL

over the intervention period, with no significant difference be- group compared with 1.4 앐 0.9% in the LF group. The percent-

tween the groups: WELL group increased to 4.4 앐 0.7 (x 앐 SEM) age decrease in DBP was 6.4 앐 1.1% in the WELL group com-

h/wk and LF group to 4.6 앐 0.5 h/wk (both P 쏝 0.01 for the pared with 1.0 앐 1.0% in the LF group. The significance of the

change from baseline). difference in the percentage change between groups was P ҃

There were no significant differences between the groups at 0.005 (SBP) and P ҃ 0.001 (DBP).

baseline in fruit, vegetable, and dairy intakes as recorded on the After adjustment for baseline BP and body weight, the differ-

food-frequency questionnaire. At week 12, the WELL group ence in the decrease in SBP and DBP between groups remained

reported a higher intake of dairy products, but there was no [SBP: 5.2 앐 1.8 mm Hg (P ҃ 0.006); DBP: 4.8 앐 1.3 mm Hg

significant difference between the groups in fruit and vegetable (P ҃ 0.001)]. Overall, there was a significant effect of diet on BP

intakes. Fruit intake increased significantly during the diet com- (SBP, P ҃ 0.006; DBP, P ҃ 0.001; n ҃ 54; repeated measures,

pared with baseline for both groups (both P ҃ 0.001; Table 3). two-factor ANOVA: time ҂ diet effect). Adding baseline body986 NOWSON ET AL

TABLE 2 study; however, there was no significant change in triacylglyc-

Intervention outcomes at baseline and 12 wk by randomized group erol in the LF group and a tendency for a decrease in the WELL

assignment1 group of 0.3 앐 0.1 mmol/L (P ҃ 0.051; Table 2).

WELL diet group LF diet group Regression analysis indicated that initial weight was not re-

(n ҃ 27) (n ҃ 27) P2 lated to changes in SBP and DBP. However, the percentage

weight loss was related to the percentage change in SBP and DBP

Weight (kg)

[SBP: R2 ҃ 0.16,  (앐SE) ҃ 0.65 앐 0.20, P ҃ 0.003; DBP: R2 ҃

Baseline 88.2 앐 1.8 98.2 앐 1.9 0.001

12 wk 83.3 앐 1.8 93.6 앐 1.8 0.16,  ҃ 0.73 앐 0.23, P ҃ 0.003]; a 10% change in weight was

Change Ҁ4.9 앐 0.63 Ҁ4.6 앐 0.63 0.75 associated with a 7% decrease in both SBP and DBP. Univariate

Walking (h/wk) linear regression analysis indicated that the increase in total dairy

Baseline 3.1 앐 0.5 2.3 앐 0.4 0.249 product intake was associated with the decrease in DBP (R2 ҃

12 wk 4.4 앐 0.7 4.6 앐 0.5 0.118,  ҃ 0.959 앐 0.364, P ҃ 0.011) and the increase in

Change ѿ1.4 앐 0.44 ѿ2.2 앐 0.53 0.200 vegetable intake was associated with the decrease in DBP (R2 ҃

Home SBP (mm Hg) 0.071,  ҃ 0.968 앐 0.487, P ҃ 0.052).

Baseline 130.9 앐 2.9 128.4 앐 2.0 0.494

12 wk 123.3 앐 2.2 126.3 앐 1.7

Change Ҁ7.6 앐 1.53 Ҁ2.1 앐 1.2 0.006 DISCUSSION

Home DBP (mm Hg)

Baseline 82.3 앐 1.6 84.0 앐 1.6 0.466 The present study investigated the effects on home BP of 2

12 wk 76.9 앐 1.6 83.0 앐 1.4 dietary interventions— one based on the DASH dietary pattern

Change Ҁ5.4 앐 0.93 Ҁ1.0 앐 0.8 0.001 and the other a usual low-fat diet— combined with increased

Home pulse (beats/min) physical activity to achieve weight loss. We found that the sub-

Baseline 67.6 앐 2.1 69.4 앐 2.1 0.536 jects in both diet groups achieved a weight loss of 앒5– 6% of

12 wk 61.4 앐 1.7 67.1 앐 2.0 body weight over 3 mo. Those in the WELL group, however, had

Change Ҁ6.2 앐 1.33 Ҁ2.4 앐 1.05 0.023 greater decreases in SBP and DBP of 앒5 and 4 mm Hg, respec-

Cholesterol (mmol/L) tively. The groups were well matched at baseline for BP and for

Baseline 5.3 앐 0.2 5.3 앐 0.2 0.756

the number of subjects taking antihypertensive medication (33%

12 wk 4.7 앐 0.2 4.8 앐 0.2

Change Ҁ0.7 앐 0.13 Ҁ0.4 앐 0.13 0.099

in each group), although BMI was initially one unit higher in the

HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) LF group than in the WELL group. This difference, however, is

Baseline 1.16 앐 0.04 1.14 앐 0.04 0.697 unlikely to have contributed to the increased effectiveness of the

12 wk 1.05 앐 0.03 1.09 앐 0.05 WELL diet with respect to BP, because there was no significant

Change Ҁ0.11 앐 0.033 Ҁ0.05 앐 0.025 0.085 difference in percentage weight loss between the groups.

LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) The reason for the greater decrease in BP with the WELL diet

Baseline 3.4 앐 0.1 3.2 앐 0.2 0.571 is not clear. We found no significant difference between the 2

12 wk 2.9 앐 0.1 2.9 앐 0.2 groups in the change in blood lipids, although those in the WELL

Change Ҁ0.4 앐 0.13 Ҁ0.3 앐 0.14 0.419 diet group did appear to have a greater reduction in total fat and

Triacylglycerol (mmol/L)

particularly saturated fat intake. Our power to detect a difference

Baseline 1.9 앐 0.1 2.0 앐 0.2 0.501

12 wk 1.6 앐 0.1 2.0 앐 0.2

in blood lipids, however, was low because of the limited number

Change Ҁ0.3 앐 0.1 Ҁ0.1 앐 0.2 0.346 of subjects.

Some of the dietary differences between the WELL and the LF

1

All values are x 앐 SEM. WELL, DASH-type weight-loss diet (mod- diet may explain some of the improved BP-lowering effect of the

erate sodium, high potassium, high calcium, low fat, with less red meat and

WELL diet, specifically, the increase in dietary potassium,

more fish); LF, low-fat diet; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic

blood pressure.

which has been shown to lower BP by 앒3 mm Hg systolic and 2

2

Difference between the WELL and LF diet groups (unpaired t test). mm Hg diastolic (11). Dietary calcium and magnesium have also

Note that values are not adjusted. Adding baseline blood pressure or weight been weakly associated with lower BP in population studies (12,

as a covariate did not significantly affect the mean changes. 13), although evidence for a BP-lowering effect in controlled

3–5

Significance of change (12 wk Ҁ baseline; paired t test): 3P 쏝 0.001, intervention studies is not consistent (14). It appears, however,

4

P 쏝 0.01, 5P 쏝 0.05. that a diet combining these nutrient changes— eg, lower sodium

and saturated fat and higher potassium, calcium, magnesium, and

phosphorus—within a diet and physical activity pattern that in-

duces negative energy balance achieves a greater reduction in BP

weight as a covariate to the model did not significantly affect the than does a low-fat diet.

results (SBP, P ҃ 0.001; DBP, P ҃ 0.001; n ҃ 54; repeated- The food-frequency questionnaire indicated a difference be-

measures, two-factor ANOVA: time ҂ diet effect). Additionally, tween groups at the end of the study in dairy intake only and not

a model that included baseline BP and body weight as covariates in fruit and vegetable intakes. This likely reflects the insensitivity

did not significantly affect the results (SBP, P ҃ 0.003; DBP, P ҃ of a food-frequency questionnaire in picking up relatively small

0.001; n ҃ 54; repeated-measures, two-factor ANOVA: time ҂ changes in food intake. It may also indicate that the increase in

diet effect). The pulse rate was lower in the WELL group than in dairy products, when combined with more vegetables, is a sig-

the LF group (P ҃ 0.031; n ҃ 54; repeated-measures, two-factor nificant factor with respect to BP reduction, particularly because

ANOVA: time ҂ diet effect). the linear regression analysis indicated that the change in total

Serum total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and LDL choles- dairy intake together with the change in vegetable intake was

terol decreased significantly in both groups by the end of the univariately associated with the reduction in DBP.DIET, WEIGHT LOSS, AND BLOOD PRESSURE 987

TABLE 3

Intervention nutrient outcomes at baseline and 12 wk by randomized group assignment1

WELL diet group (n ҃ 27) LF diet group (n ҃ 27) P2

Fruit (servings/d)3

Baseline 2.2 앐 0.24 2.7 앐 0.3 0.147

Intervention 3.8 앐 0.2 3.6 앐 0.3

Change 1.5 (1.0, 1.9)5 1.1 (0.6, 1.5) 0.210

Vegetables (servings/d)3

Baseline 2.2 앐 0.2 2.6 앐 0.2 0.262

Intervention 3.4 앐 0.2 3.0 앐 0.3

Change 1.1 (0.6, 1.6) 0.5 (0.0, 0.9) 0.075

Dairy products (servings/d)3,6

Baseline 2.3 앐 0.2 2.9 앐 0.3 0.147

Intervention 4.0 앐 0.2 2.6 앐 0.3

Change 1.5 (1.0, 2.0) Ҁ0.0 (Ҁ0.5, 0.5) 0.001

Energy (MJ/d)7

Baseline 10.4 앐 0.6 11.3 앐 0.5 0.262

Intervention 8.4 앐 0.3 8.7 앐 0.4

Change Ҁ2.4 (Ҁ3.0, Ҁ1.7) Ҁ2.3 (Ҁ2.9, Ҁ1.6) 0.810

Protein (g/d)7

Baseline 108.2 앐 6.2 115.7 앐 5.7 0.373

Intervention 104.1 앐 3.6 103.7 앐 3.

Change Ҁ7.5 (Ҁ14.8, Ҁ0.2) Ҁ8.6 (Ҁ15.9, Ҁ1.3) 0.834

Fat (g/d)7

Baseline 85.8 앐 6.9 101.2 앐 8.3 0.160

Intervention 44.0 앐 3.3 57.4 앐 4.4

Change Ҁ48.4 (Ҁ56.0, Ҁ40.8) Ҁ37.2 (Ҁ44.8, Ҁ29.6) 0.042

Saturated fat (g/d)7

Baseline 31.5 앐 3.2 38.7 앐 3.2 0.122

Intervention 11.5 앐 1.0 19.2 앐 1.4

Change Ҁ23.3 (Ҁ25.8, Ҁ20.7) Ҁ16.1 (Ҁ18.7, Ҁ13.6) 0.001

Carbohydrate (g/d)7

Baseline 302.4 앐 19.8 307.6 앐 13.1 0.827

Intervention 289.8 앐 11.4 270.1 앐 13.0

Change Ҁ14.6 (Ҁ38.2, 9.0) Ҁ35.5 (Ҁ59.1, Ҁ12.0) 0.214

Cholesterol (mg/d)7

Baseline 323.7 앐 31.1 331.7 앐 24.6 0.840

Intervention 184.3 앐 16.0 237.1 앐 21.0

Change Ҁ143.5 (Ҁ181.4, Ҁ105.6) Ҁ90.5 (Ҁ128.4, Ҁ52.7) 0.052

Protein (% of energy)7

Baseline 16.8 앐 0.6 6.6 앐 0.7 0.814

Intervention 19.8 앐 0.5 19.5 앐 0.7

Change 3.0 (1.9, 4.1) 2.8 (1.7, 3.9) 0.047

Fat (% of energy)7

Baseline 29.9 앐 1.4 31.8 앐 1.6 0.380

Intervention 18.5 앐 1.1 23.8 앐 1.3

Change Ҁ12.0 (Ҁ14.3, Ҁ9.8) Ҁ7.3 (Ҁ9.6, Ҁ5.1) 0.004

Saturated fat (% of energy)7

Baseline 10.8 앐 0.7 12.1 앐 0.7 0.184

Intervention 4.9 앐 0.4 8.0 앐 0.5

Change Ҁ6.5 (Ҁ7.3, Ҁ5.7) Ҁ3.6 (Ҁ4.5, Ҁ2.8) 0.001

Carbohydrate (% of energy)7

Baseline 49.4 앐 1.7 47.3 앐 1.8 0.396

Intervention 59.1 앐 1.4 53.5 앐 1.6

Change 10.4 (7.6, 13.3) 5.5 (2.6, 8.3) 0.017

Alcohol (g/d)7

Baseline 12.0 앐 3.3 17.6 앐 4.5 0.325

Intervention 6.4 앐 2.5 10.1 앐 3.7

Change Ҁ6.8 (Ҁ11.5, Ҁ2.2) Ҁ6.2 (Ҁ10.9, Ҁ1.6) 0.862

Alcohol (% of energy)7

Baseline 3.5 앐 1.0 4.1 앐 1.0 0.631

Intervention 3.1 앐 1.0 4.2 앐 1.1

Change Ҁ0.5 (Ҁ2.1, 1.2) 0.2 (Ҁ1.4, 1.9) 0.570

Fiber (g/d)7

Baseline 29.6 앐 1.4 28.9 앐 1.6 0.735

Intervention 37.5 앐 1.6 34.3 앐 1.9

Change 8.1 (4.7, 11.5) 5.2 (1.8, 8.6) 0.225

Sodium (mmol/d)7

Baseline 2982.1 앐 206.5 3457.7 앐 291.5 0.190

Intervention 2023.9 앐 108.9 2669.2 앐 172.9

Change Ҁ1144.1 (Ҁ1417.0, Ҁ871.2) Ҁ602.7 (Ҁ875.6, Ҁ329.8) 0.007

(Continued)988 NOWSON ET AL

TABLE 3 (Continued)

WELL diet group (n ҃ 27) LF diet group (n ҃ 27) P2

Potassium (mmol/d)7

Baseline 3972.9 앐 185.3 4056.5 앐 185.1 0.751

Intervention 5270.1 앐 197.1 4344.4 앐 180.1

Change 1265.7 (894.3, 1637.2) 319.4 (Ҁ52.1, 690.9) 0.001

Calcium (mg/d)7

Baseline 981.9 앐 68.7 889.6 앐 62.0 0.324

Intervention 1415.8 앐 67.6 986.6 앐 53.0

Change 462.8 (349.9, 573.8) 69.2 (Ҁ42.7, 181.1) 0.001

Magnesium (mg/d)7

Baseline 420.9 앐 20.6 411.4 앐 21.6 0.751

Intervention 474.3 앐 1.49 413.4 앐 17.0

Change 56.8 (21.7, 91.9) Ҁ1.4 (Ҁ36.5, 33.7) 0.022

Phosphorus (mg/d)7

Baseline 1831.2 앐 97.3 1845.7 앐 82.6 0.910

Intervention 2025.1 앐 75.9 1756.0 앐 65.1

Change 188.3 (51.1, 325.6) Ҁ84.1 (Ҁ221.3, 53.2) 0.007

1

WELL, DASH-type weight-loss diet (moderate sodium, high potassium, high calcium, low fat, with less red meat and more fish); LF, low-fat diet.

2

Difference between the WELL and LF diet groups (unpaired t test).

3

Based on food-frequency questionnaire.

4

x 앐 SEM (all such values).

5

x ; 95% CI in parentheses (all such values). Mean changes were adjusted for baseline values.

6

Calcium-containing, reduced-fat dairy foods (eg, milk, cheese, and yogurt).

7

Based on 24-h recall.

Although dietary records are not a good measure of actual added salt and obviously salty foods, and we found in a previous

sodium intake, after adjustment for baseline sodium intake, there study (9) that this type of dietary advice can result in a decrease

was a significant reduction in dietary sodium in the WELL group in 24-h urinary sodium of 앒30 mmol in a weight-stable situation.

only. It is therefore likely that those following the WELL diet did In the present study, in which there was a reduction in energy

have a lower intake of sodium. Subjects were advised to avoid intake, the reduction in sodium is likely to have been greater, but

without having data on 24-h urine collections we cannot confirm

this finding.

The decreases in BP in the present study were somewhat

greater than in other studies, particularly the 5–mm Hg decrease

in DBP. A meta analysis of weight loss and BP indicated an

average decrease in SBP and BDP of 4 mm Hg in studies with

energy restriction with or without exercise (15), whereas we

found decreases of 8 and 5 mm Hg in SBP and DBP, respectively.

Our results contrast with those of the recent large, multicenter

Premier study (16). In that study, untreated subjects with mild

hypertension who were randomly assigned to the DASH inter-

vention achieved decreases of 11 mm Hg in SBP and 7 mm Hg

in DBP with a 5-kg weight loss over 6 mo, and these decreases

were not significantly different from those seen in the established

care group, who had a similar weight loss.

Ours is the first study to assess the effect of a weight-loss

intervention on home BP measurements rather than on

investigator-measured BP. Some of the difference in BP re-

sponse could be attributed to the different method of BP assess-

ment. Home BP, measured at the same time of day, under the

same conditions, shows reduced variability. Home BP measure-

ment is now emerging as a preferred method of measuring BP

(17), because it has been shown to share some of the advantages

of ambulatory BP, that is, to have no “white coat” effect (18), to

FIGURE 1. Mean (앐SEM) systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood be more reproducible (19, 20), and to be more predictive of the

pressure over 12 wk of intervention in the LF (䉬) and WELL (■) diet groups. presence and progression of organ damage than are office or

WELL, DASH-type weight-loss diet (moderate sodium, high potassium,

clinic values (21). Because all our subjects used BP monitors for

high calcium, low fat, with less red meat and more fish); LF, low-fat diet.

Two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA: time ҂ diet effect, P ҃ 0.006 for which their data were downloaded directly to a computer by the

SBP, P ҃ 0.001 for DBP; n ҃ 54 (unadjusted). study staff, there was no possibility for errors in subject recording.DIET, WEIGHT LOSS, AND BLOOD PRESSURE 989

The results of the present study clearly show that targeted dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research

dietary advice (ie, to include 욷4 servings each of fruit and veg- Group. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1117–24.

8. Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concen-

etables per day, 3 servings of nonfat dairy products per day, and tration of low density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma without use of

3 servings of fish and 1 serving of legumes per week and to avoid preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972;18:499 –502.

butter and added salt) combined with advice to walk 욷0.5 h on 9. Nowson CA, Worsley A, Margerison C, et al. Blood pressure response

most days of the week resulted in a 5% weight loss, an 8 –mm Hg to dietary modifications in free-living individuals. J Nutr 2004;134:

decrease in SBP, and a 5–mm Hg decrease in DBP over 3 mo. In 2322–9.

10. Harada ND, Chiu V, King AC, Stewart AL. An evaluation of three

addition, the study showed that a lifestyle intervention that can be self-reported physical activity instruments for older adults. Med Sci

successfully implemented by obese or overweight free-living Sports Exerc 2001;33:962–70.

individuals results in a greater decrease in BP than does the usual, 11. Whelton PK, He J, Cutler JA, et al. Effects of oral potassium on blood

general dietary advice to reduce fat intake. The reason for the pressure Meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. JAMA

1997;277:1624 –32.

increased efficacy of this diet over the low-fat diet with respect 12. Cappuccio FP, Elliott P, Allender PS, Pryer J, Follman DA, Cutler JA.

to BP is not clear, but may be related to the increases in potassium Epidemiologic association between dietary calcium intake and blood

and calcium intakes. pressure: a meta-analysis of published data. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:

935– 45.

CAN and AW were responsible for the conception and overall supervision 13. Jee SH, Miller ER 3rd, Guallar E, Singh VK, Appel LJ, Klag MJ. The

of the study. CAN was responsible for the drafting of the manuscript, critical effect of magnesium supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis

revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, and final approval of the of randomized clinical trials. Am J Hypertens 2002;15:691– 6.

manuscript. CM, MKJ, SJG, and AB interviewed all participants, adminis- 14. Allender PS, Cutler JA, Follmann D, Cappuccio FP, Pryer J, Elliott P.

tered dietary counseling, and with AW contributed to drafting of the manu- Dietary calcium and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized

script. SJG was responsible for biochemical processing and analysis. None of clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:825–31.

15. Neter JE, Stam BE, Kok FJ, Grobbee DE, Geleijnse JM. Influence of

the authors had any conflicts of interest.

weight reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. Hypertension 2003;42:878 – 84.

16. Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. Effects of comprehensive

lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the

REFERENCES PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA 2003;289:2083–93.

1. MacMahon S, Cutler JA, Stamler J. Antihypertensive drug treatment. 17. Guidelines Committee. European Society of Hypertension-European

Potential, expected, and observed effects on stroke and on coronary heart Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hyper-

disease. Hypertension 1989;13:I45–50. tension. J Hypertens 2003;21:1011–53.

2. Briganti EM, Shaw JE, Chadban SJ, et al. Untreated hypertension among 18. Mancia G, Zanchetti A, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. Ambulatory blood pres-

Australian adults: the 1999 –2000 Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Life- sure is superior to clinic blood pressure in predicting treatment-induced

style Study (AusDiab). Med J Aust 2003;179:135–9. regression of left ventricular hypertrophy. SAMPLE Study Group. Study

3. Britt H, Miller GC, Knox S, et al. General practice activity in Australia on Ambulatory Monitoring of Blood Pressure and Lisinopril Evaluation

2002-03. AIHW cat. no. GEP 14. Canberra, Australia: Australian Insti- Circulation. 1997;95:1464 –70.

tute of Health and Welfare, 2003 (General Practice Series no. 14). 19. Sakuma M, Imai Y, Nagai K, et al. Reproducibility of home blood

4. Silventoinen K, Sans S, Tolonen H, et al. Trends in obesity and energy pressure measurements over a one-year period. Am J Hypertens 1997;

supply in the WHO MONICA Project. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 10:798 – 803.

2004;28:710 – 8. 20. Stergiou GS, Baibas NM, Gantzarou AP, et al. Reproducibility of home,

5. Cameron AJ, Welborn TA, Zimmet PZ, et al. Overweight and obesity in ambulatory, and clinic blood pressure: implications for the design of

Australia: the 1999 –2000 Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle trials for the assessment of antihypertensive drug efficacy. Am J Hyper-

Study (AusDiab). Med J Aust 2003;178:427–32. tens 2002;15:101– 4.

6. El-Atat F, Aneja A, McFarlane S, Sowers J. Obesity and hypertension. 21. Mule G, Caimi G, Cottone S, et al. Value of home blood pressures as

Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2003;32:823–54. predictor of target organ damage in mild arterial hypertension. J Car-

7. Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of diovasc Risk 2002;9:123–9.You can also read