What's next for social protection in light of COVID-19: country responses - IPC-IG

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

A publication of

The International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth

Volume 19, Issue No. 1 • March 2021

What's next for

social protection in light of

COVID-19: country responsesPolicy in Focus is a regular publication of the International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG).

Published by the International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG) The IPC-IG disseminates the findings of its work in progress to encourage

the exchange of ideas about development issues. The papers are signed by

Policy in Focus, Volume No. 19, Issue No. 1, March 2021 the authors and should be cited accordingly. The findings, interpretations,

What's next for social protection in light of COVID-19: and conclusions that they express are those of the authors and not

country responses necessarily those of the United Nations Development Programme or the

Government of Brazil. This publication is available online at www.ipcig.org.

Copyright© 2021 International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth

For further information on IPC-IG publications, please feel free to contact

The IPC-IG is a partnership between the United Nations and the publications@ipcig.org.

Government of Brazil to promote learning on social policies. The Centre

specialises in research-based policy recommendations to foster the Cover photo: Renato Alves/Agência Brasília .

reduction of poverty and inequality as well as promote inclusive growth. Some of the photographs used in this publication are licensed under

The IPC-IG is linked to the United Nations Development Programme The Creative Commons license; full attribution and links to the individual

(UNDP) in Brazil, the Ministry of Economy (ME) and the Institute for Applied licenses are provided for each.

Economic Research (Ipea) of the Government of Brazil. Rights and permissions—all rights reserved. The text and data in

this publication may be reproduced as long as the source is cited.

Director: Katyna Argueta

Reproductions for commercial purposes are forbidden.

IPC-IG Research Coordinators: Alexandre Cunha, Fábio Veras Soares,

Mariana Balboni and Rafael Guerreiro Osorio Acknowledgements: The Editors would like to express their

sincere appreciation to João Pedro Dytz, Luis Vargas Faulbaum,

Specialist Guest Editors: Charlotte Bilo, Roberta Brito, Maya Hammad, Anna Carolina Machado, Yannick Markhof, Nurth Palomo,

Aline Peres and Mariana Balboni (IPC-IG) Camila Pereira, Lucas Sato, Fábio Veras Soares and Anaïs Vibranovski for

reviewing and translating some of the articles in this issue. We would also

In-house Editor: Manoel Salles like to thank the whole socialprotection.org team and all partners who

made the e-conference ‘Turning the Covid-19 crisis into an opportunity:

Publications Manager: Roberto Astorino What’s next for social protection’ (5-8 October 2020) possible.

This issue is a direct result of the conference.

Copy Editor: Jon Stacey, The Write Effect Ltd.

Art and Desktop Publishing: Flávia Amaral and Priscilla Minari ISSN: 2318-8995Summary

7 How countries in the global South have used social protection to attenuate

the impact of the COVID-19 crisis?

Charlotte Bilo, Maya Hammad, Anna Carolina Machado, Lucas Sato, Fábio Veras Soares and Marina Andrade

11 How might the lessons from the response to COVID-19 influence future

social protection policy and delivery?

Rodolfo Beazley, Valentina Barca and Martina Bergthaller

14 The COVID-19 crisis: A turning point or a tragic setback?

Shahra Razavi

17 The main lesson of COVID-19: Making social protection universal, adaptive and sustainable

Michal Rutkowski

20 Emergency Aid: The Brazilian response to an unprecedented challenge

Nilza Yamasaki and Fabiana Rodopoulos

22 Tools to protect families in Chile: A State at the service of its people

Alejandra Candia

24 Colombia’s experience in addressing the COVID-19 crisis

Laura Pabón

26 Lessons learned from Jordan’s national social protection response to COVID-19

Manuel Rodriguez Pumarol, Ahmad Abu Haider, Nayef Ibrahim Alkhawaldeh, Muhammad Hamza Abbas and Satinderjit Singh Toor

29 Morocco’s social protection response to COVID-19 and beyond—

towards a sustainable social protection floor

Karima Kessaba and Mahdi Halmi

32 The role of Namibia’s civil registration and identity system in the country’s

COVID-19 social response

Anette Bayer Forsingdal, Tulimeke Munyika and Zoran Đokovic

35 The Republic of Congo’s social protection response before and during COVID-19:

Perspectives from the Lisungi programme

Martin Yaba Mambou, Lisile Ganga and Cinthia Acka-Douabele

37 Tackling poverty amidst COVID-19:

How Pakistan’s emergency cash programme averted an economic catastrophe

Sania Nishtar

40 Cambodia’s social protection response to COVID-19

Theng Pagnathun, Sabine Cerceau and Emily de Riel

43 How to overcome the impact of COVID-19 on poverty in Indonesia?

Fisca Aulia and MalikiEditorial

The wide-ranging consequences of the COVID-19 As a collaborative platform, socialprotection.org aimed at

crisis have had a huge impact on the world of social providing an extensive range of methodologies during

protection. The importance of providing comprehensive the conference, with a focus on giving each attendee the

and adequate social protection benefits to all has opportunity to make their own personal learning journey,

become more evident than ever. The pandemic has develop practical take-aways and action points from the

alerted national governments and the international conference and share results during the event and beyond.

community to the urgency of accelerating progress in Besides sending questions and engaging in discussions

building and expanding social protection systems and before, during and after the event, participants were invited

programmes to leave no one behind. Governments to participate in a self-reflection activity on their country’s

across the globe have mobilised a huge number of responses to the COVID-19 crisis by adding notes to a virtual

resources and effort to protect those who have been wall created especially for the event. To demonstrate their

most affected by the crisis. So far, countries with more commitment to social protection, participants were also

solid social protection foundations have been able to asked to list practical actions that they could pursue.

respond more rapidly and efficiently.

Adapting face-to-face engagement to online formats,

In this context, from 5 to 8 October 2020, the with participants from different country and institutional

socialprotection.org team organised a global backgrounds, was a learning experience itself and

e-conference titled ‘Turning the COVID-19 crisis into demanded meticulous planning and creativity from

an opportunity: What’s next for social protection?’. our team members and partners, who worked around

The conference functioned as a virtual live space for the the clock to make this conference as participatory and

global social protection community to share innovative inclusive as possible.

ideas and practical insights, and brainstorm about the

Given the success of the e-conference and to further

future of social protection in a post-pandemic world.

disseminate its key discussions, the socialprotection.org

The e-conference also marked socialprotection.org’s fifth

platform and the International Policy Centre for Inclusive

anniversary, consolidating the platform’s position as the

Growth (IPC-IG) have developed two special issues of Policy

leading tool for knowledge-sharing and capacity-building

in Focus. This first issue focuses on experiences from countries

on social protection.

in Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan

To ensure the active participation of a broad and diverse Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as the

audience, a total of 72 sessions across three different overall lessons for the future, including shock-responsive

time zones were organised, with inputs from partners and universal social protection. The second issue provides

and collaborators across 55 different organisations. a thematic focus, delving in more depth into the main

Sessions were held in English, French and Spanish, with topics discussed during the round tables, such as financing,

simultaneous translation. This effort guaranteed the universal basic income, linkages to food security and

involvement of more than 2,100 participants among employment, as well as gender-, child- and disability-sensitive

social protection practitioners, policymakers, academics programmes, among others. All articles were written at the

and enthusiasts from all over the world. end of 2020 by panellists and/or organisers of the conference.

For the recordings of all sessions and more information about

On the first day of activities, a regional lens was used

the conference, see: .

to assess the various social protection responses across

different regions. Day 2 applied a thematic approach to We hope that the following set of articles contributes

address specific questions related to COVID-19 and beyond to the debate by communicating the urgency and

through round tables, expert clinics and virtual booth talks. importance of providing comprehensive and adequate

The third day was reserved for side events organised by social protection to all—especially in times of crisis.

some of our partners. Finally, on the fourth and last day

of the event, special guests reflected on the discussions,

lessons learned and conclusions of the previous days. Aline Peres, Mariana Balboni, Charlotte Bilo and Roberta Brito

6How countries in the global South have

used social protection to attenuate

the impact of the COVID-19 crisis?1

Charlotte Bilo,2 Maya Hammad,2 objective to provide inputs for the Emergency cash and in-kind transfers

Anna Carolina Machado,2 Lucas Sato,2 assessment of the shock-responsiveness were the most prevalent social assistance

Fábio Veras Soares3 and Marina Andrade 2 of countries’ social protection systems.4 instrument used in the global South.

Preliminary findings of the analysis were Except for Latin America and the

Unprecedented social protection presented during the regional panels of Caribbean (LAC), subsidies on food,

measures have been adopted worldwide the global e-conference organised by utilities, housing and bills were also

in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, socialprotection.org on 5 October 2020.5 common, especially in SSA. Furthermore,

with a view to: (i) supporting the infected while very few measures adapting school

population so that they can afford the Policy overview feeding programmes were identified

direct and indirect costs of treatment; The majority (61 per cent) of the measures in South Asia (SA), East Asia and Pacific

(ii) compensating workers for the mapped were classified as social assistance, (EAP), SSA and the Middle East and

immediate loss of income and jobs due followed by 26 per cent for labour market, North Africa (MENA), a sizeable number

to restrictions on business operations and 13 per cent for social insurance. were found in LAC.7 An important policy

as part of containment measures, and In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) social assistance change that was observed during the

incentivising compliance with them; measures represented 77 per cent of all crisis was the shift from targeting only

and (iii) responding to the negative measures adopted. The region also had the the poorest populations to also including

impacts of the pandemic on smallest share of social insurance measures the ‘missing middle’, mainly informal

employment, incomes and livelihoods (4 per cent). These numbers can be workers who were often not receiving

beyond the immediate effects of partial explained by the large size of the informal any social protection benefits before

or total lockdowns. The pursuit of these sector and the consequent low level of (see the articles on Morocco, Brazil,

objectives by countries, particularly social insurance coverage. Colombia and Chile in this issue). In total,

in the global South, has revealed the 76 out of 384 programmes for which

crucial importance of building inclusive, The literature on shock-responsive information was available explicitly

comprehensive and efficient social social protection broadly classifies social included informal workers.

protection systems that can be rapidly protection responses into horizontal

scaled up in times of crisis. and vertical expansions. Horizontal As for social insurance, unemployment

expansions refer to: (i) the inclusion of new insurance and contributory pensions were

Since the outbreak of the pandemic in beneficiaries in existing programmes,6 the most prevalent instruments used

March 2020, the IPC-IG research team even if only temporarily; and/or globally. Out of 31 responses through

and partners have mapped at least 786 (ii) the creation of new (emergency) unemployment insurance instruments,

(as of January 2021) social protection programmes, which can also be linked 14 countries created new temporary

responses in the global South (in 129 to existing programmes or at least unemployment benefits to protect

countries and territories), namely social build or piggyback on their systems workers who lost their jobs due to the

assistance, social insurance and labour (e.g. payment mechanisms, registries). COVID-19 crisis. The other 17 responses

market measures. While this number is Vertical expansions refer to: (i) increases adapted existing schemes mainly by

impressive, it does not say much about in benefit values; and/or (ii) adding a new waiving certain requirements such as

how many people they cover and how component (e.g. additional services) to the minimum contribution period or

adequately their benefits meet people’s existing programmes. extending the duration of benefits and/or

needs. This article aims to: increasing values. Moreover, contributory

(i) provide an overview of the main Looking at all the social protection measures pensions permitted anticipated

social protection measures adopted mapped, 70.5 per cent were horizontal withdrawals (of provident funds) or

in the global South to respond to the expansions, either through existing payments of benefits. Other measures

COVID-19 crisis; (ii) highlight innovations programmes (13.5 per cent) or emergency included the expansion of or changes to

in the process to identify, register and schemes (57 per cent). On the other hand, the coverage of health insurance services

deliver social protection measures to 23.3 per cent of the measures were vertical (more prevalent in EAP and LAC) or

beneficiaries in the context of the crisis; expansions through increases in benefit adjustments to sick leave rules (especially

and (iii) analyse their coverage and values (11.5 per cent), the introduction of in MENA). It should be noted that most

adequacy. The findings presented here new components for beneficiaries (11.3 per horizontally expanded measures (69.8

are based on information collected cent) or a combination of both approaches per cent) exclusively targeted workers in

through a tracking matrix with the (0.5 per cent). formal employment.

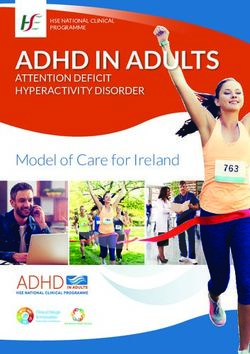

The International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth | Policy in Focus 7FIGURE 1: Coverage and benefit level of selected cash transfer programmes

Guatemala – Bono Familia [3] 7%

77%

27%

Peru – Bono Familiar Universal [2] 60%

18%

LAC

Argen

na – Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia 59%

29%

Brazil – Auxílio Emergencial [9] 61%

11%

Bolivia – Bono Universal [1] 35%

Malaysia – Bantuan Sara Hidup [1] 1%

76%

30%

Phillipines – Social Ameliora

on Programme [2]

Asia-Pacific

69%

Pakistan – Ehsas Emergency Cash [1] 7%

49%

13%

Thailand – Cash Handouts [8] 45%

Malaysia – Bantuan Priha n Nasional [2] 35%

33%

18%

Morocco – Support for informal workers and families [3] 55%

11%

Iraq – Emergency Grant [2] 29%

MENA

Jordan – SPP for daily wage workers [3] 14%

12%

Tunisia – CT for families affected by the quaran

ne [1] 12%

10%

6%

Egypt – Salary for informal workers [3] 7%

NA

Zambia – COVID-19 Emergency CT [3] 14%

NA

Mozambique – Programa Subsídio Social Básico 12%

NA

SSA

Rwanda – Vision 2020 Umurenge Programme 5%

NA

Zimbabwe – CT [3] 2%

0%

Guinea – Nafa Emergency CT [3] 1%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90%

Coverage (% total pop.)

Adequacy (benefit in % of household expenditure, montlhy) Adequacy (benefit in % of household income, montlhy)

Notes: In some cases, the benefit amount depends on the number of household members; therefore, maximum values were considered here. In the case of benefits paid per

person without a cap per household, the average household size was considered. The number in square brackets indicates the number of payments, when this information

was available. In some cases, numbers are based only on announcements. For expenditure and income, the latest data available were used and adjusted for inflation.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the social protection response mapping, as of February 2021.

Labour market measures were introduced implemented to protect self-employed Open registration (online portals) was the

to support firms to retain workers on the workers, but when adopted they usually main mechanism used to identify potential

payroll and struggling self-employed included lowering or deferring social beneficiaries, followed by social security or

workers or owners of micro and small security contributions (as implemented in tax databases and existing social registries/

firms. Wage subsidies were adopted as a MENA and LAC) and subsidised credit (as beneficiary databases (see the articles on

mechanism to compensate for reduced implemented in SA and SSA). Indonesia and Cambodia in this issue).

working hours and the suspension or

termination of contracts. The case of Jordan Innovative mechanisms for beneficiary Togo’s emergency Novissi programme

is worth highlighting, as even businesses identification, registration and payment was notable for its rapid delivery.

that were not registered in the social Providing a rapid expansion of social The programme relied on open

security system could register for wage protection to respond to COVID-19 registration through a USSD-mobile-

compensation, hence contributing to their (including the identification and based platform that enabled the country

formalisation. All regions (though only two registration of beneficiaries and the to identify potential beneficiaries, cross-

measures in SSA) lowered or deferred social logistics of benefit distribution) while check applicants’ eligibility through

security contributions for wage workers respecting health and safety requirements the voter identification database and

and their employers. Fewer measures were was a great challenge for most countries. deliver assistance through mobile

8wallets approximately five days after the the duration of the emergency measures,

programme’s announcement.8 Chile’s Bono which seemed to be the assumption

de Emergencia relied on the social registry regarding the duration of the pandemic,

to identify new beneficiaries and delivered or at least the number of months for which

assistance within two weeks (see the article some containment measures would be

in this issue). Finally, Morocco’s Emergency necessary to reduce the number of cases

Support for Informal Workers programme and avoid the collapse of the health care

combined the use of the existing medical system. When it became evident that

assistance beneficiary (RAMED) database the pandemic would last longer, some

and SMS for verification, with a web portal countries started extending the duration

to enable open registration for those not in of transfers, even if reducing the number

the database (see the article in this issue). of beneficiaries and/or the size of benefits

This procedure allowed a first batch of (e.g. Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Thailand).

payments to be made to those registered

in the RAMED database within three days In terms of coverage, LAC and EAP reached

of the start of the programme. a higher proportion of their population

with cash transfers. On the other hand,

Coverage and adequacy of responses the adequacy of measures is generally

Figure 1 shows a number of selected cash low, with most programmes providing less

transfers (most of them new interventions) than 20 per cent of households’ national

in terms of their adequacy (the benefit average income or expenditure.

provided as a percentage of household

income or expenditure) and coverage Conclusion

(the number of beneficiaries as a The COVID-19 pandemic and its

percentage of the population). We chose consequences for people’s health and

the five largest programmes for each well-being are likely to continue during

region for which data were available. the coming years. As of January 2021,

vaccination campaigns have started in

Special attention should be paid to the more than 40 countries, bringing renewed

frequency of payments (see the square hope to all. Yet mid- and long-term

number in brackets for the number of policies to tackle rising poverty levels

payments), as some schemes, despites and increased vulnerability will be key to

their high coverage or benefit value, were guaranteeing that we can build back better

designed to offer one-off payments (such after the crisis.

as the Ehsaas Emergency Cash in Pakistan,

for example, which paid one sum covering Social protection has gained significant

four months; see also the article on importance over the course of 2020, with

Pakistan in this issue). Most programmes most countries in the global South making

adopted a three-month benchmark for significant advances in the area, not only

“

The COVID-19

pandemic and its

consequences for

people’s health and

well-being are likely to

continue during

the coming years.

Photo: World Bank/Henitsoa Rafalia. COVID-19 testing, Madagascar, 2020 .

The International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth | Policy in Focus 9“ The protracted

economic crisis is

putting pressure on

national budgets,

and the continuation

of new or expanded

programmes will

require more than

just emergency

budget allocations.

Photo: IMF Photo/Saiyna Bashir. Porters waiting for passengers to hire them for work, Karachi, Pakistan, 2021

.

by providing—often for the first time— Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle

(emergency) cash transfers for the so-called East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and

East Asia and the Pacific. In addition to the type

missing middle, but also by introducing of policy responses, the mapping also includes

technological innovations (such as e-wallets information on coverage, benefit level, target

and digital registration) and mobilising groups, implementation and registration details

resources quickly. This can lay the ground as well as financial and legal framework etc. The

indicators were developed by the IPC-IG jointly

for improving the coverage and shock-

with Valentina Barca and Rodolfo Beazley (see

responsiveness of social protection systems. also the second webinar on COVID-19 social

Yet, for this to happen, it is key that the protection responses on the socialprotection.

lessons learned and the gains made during org platform: ).

The mapping is based on publicly available

the COVID-19 responses are incorporated

information in several languages and other

into the national social protection systems, mappings, including: “Social Protection and Jobs

such as by levering databases used for Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of

emergency responses, for example. Country Measures: ; the

International Labour Organization’s Country

policy responses: and

It has also become clear that the protracted Social Protection Monitor databases: ; as well as the International Social

national budgets, and the continuation Security Association’s Coronavirus country

of new or expanded programmes will measures database: .

require more than just emergency 5. See: .

budget allocations. A national debate 6. Some existing measures were not expanded

but had certain design tweaks applied, such

on progressive tax reforms and, in some

as changes in delivery methods and waiving

contexts, debt relief, with support from the of conditionalities, for example. For this article,

international community, will be needed. measures that had only implementation

To end on a more positive note, this crisis changes were excluded.

has certainly put international and national 7. After the disruption of school activities, at

least 21 countries in the region converted

discussions about the importance of social

them into take-home rations, distributed cash

protection systems that provide protection or adopted mixed approaches to tackle food

to all when they need it on another level. insecurity among students and their families. For

more information, see also Rubio, M., G. Escaroz,

A. Machado, N. Palomo, and L. Sato. 2020. “Social

1. The authors would like to thank all IPC-IG Protection and Response to Covid-19 in Latin

researchers and partners who contributed to America and the Caribbean. 2nd Edition: Social

the mapping that this article draws on. Assitance” City of Knowledge: United Nations

2. International Policy Centre for Inclusive Children’s Fund. .

Growth (IPC-IG). 8. The programme was announced on 8 April,

3. Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea) and information indicates that beneficiaries had

and IPC-IG. already received payments by 14 April. See Togo

4. The mapping was conducted by the IPC-IG First. 2020. “Social safety is key in the fight against

and partners and financed by the UNDP Brazil Coronavirus, Faure Gnassingbé affirms.” Togo First

Country Office and GIZ, covering countries in website, 14 April. .

10How might the lessons from the

response to COVID-19 influence future

social protection policy and delivery?

Rodolfo Beazley,1 Valentina Barca1 social protection systems are very diverse Overcoming the rural ‘bias’

and Martina Bergthaller 2 across countries and regions, the crisis has In many low- and middle-income countries,

both exposed limitations and revealed cash transfer programmes have low coverage

Introduction potential policy options to address them. in urban settings and have been typically

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered designed to address the needs of the rural

an unprecedented global use of social Including the ‘missing middle’ and population. The pandemic has shown the

protection schemes and systems to vulnerable populations need to improve coverage in urban areas

provide support to those affected by the The impact of COVID-19 and the (though not at the expense of rural coverage),

crisis, especially in high- and middle- containment measures implemented while adjusting programme design (e.g.

income countries (Gentilini, Almenfi, and in many countries have been especially eligibility criteria) and service delivery

Orton 2020). It poses a huge challenge devastating for informal workers, who make mechanisms to contexts with different

to the sector for a range of reasons: its up more than 60 per cent of the total global characteristics: higher mobility, higher

global reach, speed, widespread effects workforce. At the same time, the crisis has opportunity costs, informal settings where

on many different segments of a country’s shed further light on the extent to which service delivery is challenging (i.e. high crime

population, and its uniqueness—meaning informal workers are not covered by social rates, limited access to government services),

most countries did not have previous protection schemes. On the one hand, they less reliance on community structures,

experience to rely on. Although the are not poor enough to benefit from social greater penetration of mobile phones and

effects of the crisis expanded quickly, the assistance; on the other, they are excluded the Internet, among others.

full understanding of these effects, their from social insurance schemes usually

duration and depth evolved slowly. dedicated to workers in the formal sector. Building a ‘systems’ approach

The crisis has also highlighted that some

What is certain is that the ongoing role This situation represents an immense fundamental issues remain unresolved in the

of the social protection sector in the challenge to governments: to deliver timely sector. Many social protection systems are

pandemic response is a unique experience and effective social protection measures fragmented and patchy in practice, and fail to

which should inform future policies and to informal workers and their families in provide a social protection floor.6 Moreover,

programming. Although it is not possible the wake of this crisis. Many countries even though many of national social

to foresee how the COVID-19 crisis have met the challenge, via a combination protection programmes and systems are

will change the sector in the medium of strong political will and innovative legally constituted as being rights-based, in

to long term, we present some policy delivery approaches. At the same time, practice they exclude large segments of the

issues that are likely to shape future the role of informal workers in ‘essential’ population and do not address all the basic

global and national debates, as well as activities, such as food production and needs mandated. In other cases, the funding

some operational innovations in service distribution, informal care work or waste source (contributory or non-contributory)

delivery that are likely to have long-term picking, has increasingly been recognised. and the type of labour market participation

effects. These ideas are largely based on This provides a window of opportunity to (formal or informal) lead to very different

the presentations and discussions from link informal workers with social protection entitlements and unequal treatment.

the global e-conference3 organised by systems in the medium term—including by Various experts see the post-pandemic

SocialProtection.org in early October 2020, establishing a long-term bridge between period as an opportunity to invest in more

on the many knowledge products and social assistance and social insurance, as comprehensive, coherent and universal

events available during 2020 and on the well as other livelihood support measures.5 systems. This would include moving away

evidence and material generated by the from individual ‘programmes’ to ‘systems’

Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19 Similar is the case of other vulnerable that combine a range of social assistance

team (SPACE).4 populations, such as refugees and programmes (not just narrowly targeted

migrants, who have been severely affected ones) and social insurance components,

The main lessons learned from the by the crisis and are often excluded moving away from ‘benefits’ towards

COVID-19 crisis at policy level from social protection schemes. The rights-based ‘entitlements’. Interestingly, the

The COVID-19 crisis has put social COVID-19 crisis has shown the urgency of concept of Universal Basic Income—defined

protection at centre stage as a shock developing strategies (and legal backing) as a transfer that is provided universally,

response tool, and it is likely that the to integrate these populations into unconditionally, and in cash—is also gaining

demand of societies for stronger and more national systems, or alternative strategies traction in global debates (e.g. with a

inclusive systems will increase. Although for ensuring their coverage. Temporary Basic Income being proposed

The International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth | Policy in Focus 11by the United Nations Development protection programmes, as well as specific in issues related to the interoperability

Programme),7 although no country has a measures designed to respond to the crisis. and integration of information systems,

‘true’ Universal Basic Income scheme in place This is not only because of the scale and as well as the development of effective

yet (Gentilini et al. 2020). speed of the shock. ‘Containment’ measures mechanisms for the continuous updating

such as lockdowns, school closures and social of data. It will be critical to reap this

Accelerated coordination across distancing norms have also posed significant opportunity while ensuring it focuses on

sectors, actors and government layers barriers to the timely and effective delivery of and serves the right objectives—ensuring

In some countries, the response to the social protection measures. the inclusion of those in need while

pandemic has relied on some degree of strengthening policy coherence within

collaboration or coordination between Many countries have pushed the boundaries the sector and across sectors—while not

national social protection and other key of service delivery. Recent innovations and exacerbating risks (Chirchir and Barca 2019).

actors such as humanitarian agencies, but new approaches are likely to have long-term

also local actors, including civil society effects on the implementation of social Innovative mechanisms for

organisations, the private sector and protection programmes, with some countries mass registration and enrolment

communities.8,9 The pandemic seems to advancing more rapidly compared to Many countries have set up innovative

have accelerated a pre-existing process of what would have been a ‘normal’ evolution mechanisms for registering new

greater collaboration of the social protection (‘leapfrogging’). Below we present some of beneficiaries quickly, while also safeguarding

community with other sectors, which may the main innovations. social distancing, using online platforms,

lead to stronger partnerships in the future, helplines and unstructured supplementary

focused on common outcomes (SPACE 2020). Leveraging existing data service data technology, alongside reliance

and information systems on local government offices. The data

Increased and predicable financing The need to reach large segments of collected through the registration processes

Coverage gaps in social protection revealed the population swiftly has led to an were often complemented with pre-existing

during this crisis are closely linked to unprecedented use of pre-existing data (see above) to assess eligibility (Barca

significant financing gaps. Part of the crisis databases to provide additional support and Beazley 2020).

response has entailed the mobilisation of to existing beneficiaries and to identify/

considerable amounts of financial resources complement information on new The innovation in this regard has been

to finance temporary social protection beneficiaries (people likely to be affected tremendous, allowing programmes to

measures. Strategies observed in different by the crisis and in need of support). register millions of potential beneficiaries in

contexts include budget reallocations, Prior to the pandemic, there were very few a few days—further enabled by simplified

national debt and deficit measures, tapping experiences of this globally, for good reasons eligibility criteria and a ‘pay now, verify

state reserves and contingency funds, (Barca and Beazley 2019). In the COVID-19 later’ approach. This contrasts with ‘regular’

as well as external sources of financing, response, many countries have leveraged mass registrations, which are usually very

such as loans or grants from international beneficiary registries, social registries and cumbersome, costly and time-consuming,

financial institutions, which have played other information sources such as civil particularly for poverty targeted programmes.

an important role in supporting countries’ registration and vital statistics, informal

financial stability (Almenfi et al. 2020). worker organisation data, farmer registries, Although the new mechanisms have faced

tax and social insurance data, mobile money many challenges and the extent to which

Experiences with these different financing provider data, among many others—often they managed to reach the intended

modalities can inform the design of measures with identification systems acting as a populations (especially those most

to strengthen the financial resilience and backbone (Barca and Beazley 2020; Gelb and vulnerable) still needs to be assessed, it is

responsiveness of social protection systems Mukherjee 2020; World Bank 2020).10 This very likely that these innovations will have

to future shocks. The potential role of linking was done both to ‘target in’ and ‘target out’. effects on future registration and enrolment

social protection to disaster risk financing processes in many countries, with some

mechanisms to ensure that additional funds The crisis has promoted the exchange of evidence of change already happening (e.g.

are available and can be quickly disbursed data within and beyond the social protection South Africa and Peru). The challenge will

when needed has been particularly sector and highlighted the potential of pre- be to set up the capacity required to sustain

highlighted by this crisis (Poole et al. 2020). positioned data for rapid responses to large- these efforts and shift towards more on-

scale shocks. It has also re-emphasised the demand approaches to registration (Barca

The timely and efficient delivery of benefits importance of having data-sharing protocols and Hebbar 2020).

to affected populations is, however, not and mechanisms in place—alongside

exclusively reliant on available financial adequate data protection legislation—as well Nimble and flexible payment mechanisms

resources, but also requires effective as data that are inclusive, current and relevant The delivery of benefits during the

implementation mechanisms. for the response to covariate shocks, among COVID-19 pandemic has been seriously

other dimensions (Barca and Beazley 2019). constrained by mobility restrictions and

The main lessons learned at social distancing. This has helped to

operational level This experience will certainly shape future break new ground, particularly in relation

COVID-19 has posed a serious challenge investments in social protection information to electronic transfers.11 Although the

to the implementation of routine social systems. There is already increasing interest shift to electronic delivery is not new,

12the pandemic has fostered innovations of these innovations are going to have Barca, V., and R. Beazley. 2020. “Building

including (but not limited to) relaxing the long-term effects on the sector. on existing data, information systems

and registration capacity to scale up

processes and requirements for opening social protection for COVID-19 response.”

remote bank/mobile money accounts and The increased interest in and demand for SocialProtection.org blog, 1 June. . Accessed 22 January 2021.

spending in this sector, is only one side of Barca, V., and M. Hebbar. 2020. On-demand and

The innovations in payment delivery are the coin; countries are also likely to face up-to-date? Dynamic inclusion and data updating

for social assistance. Bonn: Deutsche Gesellschaft

likely to have long-term effects. This is important fiscal constraints (and pressures für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. . Accessed 22 January 2021.

in several countries, many more people put social protection spending at risk.

Chirchir, R., and V. Barca. 2020. “Building

have bank/mobile money accounts and Moreover, evidence is already showing an integrated and digital social protection

experience of government-to-person that the pandemic is exacerbating pre- information system.” Technical Paper. London:

payments. In addition, the experiences of existing needs and inequalities, and that UK Department for International Development,

and Bonn: Deutsche Gesellschaft für

new modalities, collaboration between social protection is going to be even more Internationale Zusammenarbeit, on behalf

private- and public-sector providers, necessary than before. Consequently, the of the German Federal Ministry for Economic

and registries containing account sector is likely to face a scenario of resource Cooperation and Development. . Accessed 22 January 2021.

details, are likely to promote a profound constrains and increased needs, which is

transformation in social protection going to require courageous policy choices. Gelb, A., and A. Mukherjee. 2020. “Digital

Technology in Social Assistance Transfers for

payment delivery in many countries.12 COVID-19 Relief: Lessons from Selected Cases.”

Finally, despite the sudden interest in social CGD Policy Paper, No. 181. Washington, DC:

Conclusion protection as a (large-scale, covariate) Center for Global Development. . Accessed 22 January 2021.

Responses to the pandemic have shown shock response tool, it is important to

the importance of social protection in crisis recognise that its core role is to provide Gentilini, U., M. Almenfi, and I. Orton.

adequate support to those in need, 2020. Social Protection and Jobs Responses

contexts, while also stressing the significant

to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country

provision gaps in many countries and regardless of whether the need is caused Measures. Living paper version 10, 22

shedding light on many fundamental issues by an individual shock, a large shock, May. Washington, DC: World Bank. . Accessed 2 March 2021.

that are still unresolved: the sector’s role in

promoting economic inclusion, resilience, Gentilini, U., M. Grosh, J. Rigolini, and R.

social justice and many other outcomes is still Yemtsov. 2020. Exploring Universal Basic Income:

Almenfi, M., M. Breton, P. Dale, U. Gentilini, A. Pick, A Guide to Navigating Concepts, Evidence, and

limited. However, the momentum created by and D. Richardson. 2020. “Where is the money Practices. Washington, DC: World Bank. . Accessed 22 January 2021.

social protection responses to COVID-19.” Social

progress on these issues in the near future. Protection & Jobs, Policy & Technical Note, No. Poole, L., D. Clarke, and S. Swithern. 2020.

23. Washington, DC: World Bank. . Accessed 2 March 2021. London: Centre for Disaster Protection. . Accessed 2 March 2021.

pandemic, social protection has also Barca, V., and R. Beazley. 2019. Building on

broken new ground, especially in a few Government Systems for Shock Preparedness and World Bank. 2020. Scaling up social assistance

countries where routine systems were Response: the role of social assistance data and payments as part of the COVID-19 pandemic response.

information systems. Canberra: Department of Washington, DC: World Bank Group. . Accessed 22 January 2021.

service delivery. It is likely that many Accessed 22 January 2021.

1. Social Protection Approaches to COVID-19:

Expert Advice (SPACE).

2. Independent consultant.

3. See: .

4. See: .

5. For a SPACE background note with options

for providing social protection to informal workers,

see . For Socialprotection.

org Clinic 7, see .

6. See the International Labour Organization’s

2012 Social Protection Floors Recommendation

(No. 202) at .

7. See: .

8. For a SPACE guidance note for embedding

localisation in the response to COVID-19, see

.

9. For a SPACE note with options for linking

humanitarian assistance and social protection in the

response to COVID-19, see .

10. For a SPACE guidance note on the rapid

Photo: ILO. Worker receives her emergency employment payment, Day Cotabato, Philippines, 2020 expansion of social protection caseloads,

. see .

The International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth | Policy in Focus 13The COVID-19 crisis:

A turning point or a tragic setback?

Shahra Razavi 1 International human rights and social emerging new forms of employment, such

security standards are very clear that all as work on digital platforms. In addition

The COVID-19 pandemic, which started as persons— regardless of the existence, to tax-financed life-cycle benefits, social

a major public health challenge, quickly type and duration of their employment insurance can be an effective mechanism

morphed into a protracted socio-economic relationship—should enjoy the right in this respect, as it can cover people in

crisis with which countries are still to social security.2 However, for a long different situations throughout their life

grappling. The crisis, as many have argued, time, those promoting labour market cycle and support labour mobility, and

has been a great revealer, laying bare the deregulation have portrayed informality life and work transitions (ILO 2019a).

structural inequalities of class, gender, as an inevitable process (Packard et This requires concerted policy action

race and migration status that fracture our al. 2019), rather than proposing active and clear recognition of the considerable

societies, while exposing yawning gaps in transition strategies towards formalisation diversity of workers.

social protection systems. and decent work. The corollary to a

deregulated labour market has been an Extending contributory social protection

While those with secure employment, unfounded ideological assault on the coverage to self-employed workers with

adequate health care coverage and relevance and effectiveness of the social no recognised employer is particularly

ample savings have been able to weather insurance model, while sanctioning means- difficult given the double contribution

the storm, 61.2 per cent of the global tested ‘safety nets’ to catch those unable challenge, meaning that in the absence

workforce—2 billion workers, 1.6 billion to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. of an employer the worker has to make

of whom have been affected by the COVID-19 has shown (once again) the the entire contribution, which in the

COVID-19 crisis and/or work in the hardest- limitations of such residualist approaches case of employees is usually shared with

hit sectors—remain uncovered by social that only respond when people fall into employers (ILO 2019b). Yet there are a

protection systems, making them and their abject poverty (and not even effectively so, number of countries that have extended

families particularly vulnerable to poverty given the well-known errors of exclusion). both legal and effective coverage to self-

(ILO 2020d; 2020c). Invariably, they have In doing so, the current crisis has hopefully employed workers by making concrete

not been able to count on the protection created some consensus on the need to adaptations to their social security systems.

provided by contributory social security extend social protection to the millions of Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, for example,

schemes, nor have they been well served workers in the informal economy, the so- have simplified their contribution and

by narrowly targeted cash transfers. called ‘missing middle’ (ILO 2020a; 2020e). tax payment mechanisms (through a

‘monotax’) to allow self-employed workers

‘Safety nets’ for poor people have proven Extending social protection to and micro-enterprises to pay a single flat

to be neither safe nor appropriate in workers in the informal economy payment instead of various social security

contexts where poverty is extensive and Countries that have invested in social and tax contributions. Other countries

for the kind of systemic shocks that have insurance and tax-financed life-cycle have adapted their contribution modalities

become more frequent in our globalised schemes are clearly faring much better by making them seasonal rather than

world (Kidd and Athias 2019; Mkandawire than those that built their systems on monthly, lowering the contributions, or

2005). During this pandemic, it is not just narrowly targeted programmes alone (ILO not requiring any contributions from some

those living in extreme poverty who are 2020a). This underlines the importance of groups with limited contributory capacity

being adversely affected by its socio- building contributory schemes that cover all (with governments stepping in to subsidise

economic disruptions, but also those who types of workers (and decent jobs) against their contributions from general revenue

seemed to be getting by relatively well. measures that undermine acquired rights, to enhance solidarity) (ILO 2019a).

In response, many governments have put such as waiving contributions, and creating

in place measures to reach workers in the jobs with due regard to their quality. The In the process of making such adaptations,

informal economy: Viet Nam, for example, importance of supporting the transition several useful lessons have been learned.

provided cash transfers to workers who from the informal to the formal economy Voluntary coverage does not usually lead

had lost their jobs but were ineligible must be at the centre of these efforts. to a significant extension of effective

for unemployment insurance, while coverage, nor to the creation of sufficiently

Costa Rica introduced a new emergency Workers in the informal economy are a large risk pools to provide adequate

benefit, for three months, to employees very diverse group—from wage workers in provision; it may also lead to adverse

and independent workers (both formal agriculture and domestic service, to the self- selection3 and undermine the sustainability

and informal) who had lost their jobs and employed, including urban own-account of the scheme. It is also becoming

livelihoods, and a smaller transfer to those workers and contributing family workers in increasingly clear that specific schemes

who were working reduced hours. smallholder agriculture, as well as those in for workers in the informal economy that

14“ The extension of social

protection to workers in

the informal economy

must bring a clear value

to people that they can

see, thereby building

trust in the system.

Photo: IMF Photo/Saiyna Bashir. Informal worker sells cellphones accessories at a stall in Saddar, Pakistan, 2021

.

are separate from those for formal workers gap’ (ILO 2020b). Many of these countries crisis subsides, to ensure that people are

can create disincentives for workers already face severe fiscal constraints, protected against the adverse economic

to formalise, or even create perverse including over USD1 trillion of scheduled and social consequences that are likely

incentives for their informalisation. Most external debt repayments in 2020 and 2021. to persist for longer, and to counter the

importantly perhaps, the extension of danger of growing poverty, joblessness and

social protection to workers in the informal According to the latest ILO estimates (Durán inequality. Rather than calling for another

economy must bring a clear value to Valverde et al. 2020), the additional resources round of austerity—already in full force in

people that they can see, thereby building needed to close the global financing many countries—it is urgent to streamline

trust in the system. This requires a social gap in social protection has increased by the policy frameworks of all relevant

protection system that effectively delivers approximately 30 per cent since the onset actors, including the international financial

the benefits and services that meet of the COVID-19 crisis. Developing countries institutions, with the principles set out in

workers’ and employers’ needs, as well as would need to invest an additional sum international human rights instruments and

meaningful participation of workers’ and equal to about 3.8 per cent of their average social security standards. This is particularly

employers’ organisations, including the GDP to meet the annual financing required relevant for fiscal policies, so that they can

representatives of workers in the to close coverage gaps in 2020, while for low- accommodate, rather than undermine,

informal economy. income countries (a subset of developing much-needed investments in universal

countries) the additional resources required social protection systems.

Financing much-needed are close to 16 per cent of their GDP.

investments in social protection Today we are at a turning point.

Building universal and comprehensive social This underlines the urgency of mobilising We can turn the COVID-19 crisis

protection systems that can make the right resources from diverse sources. However, into an opportunity to build robust,

to social security a reality for everyone— in doing so, particular attention needs to comprehensive and universal social

as called for in Convention 102 and be paid to the equity of tax collection— protection systems and resist the

Recommendation 202 on social protection for example, by taxing the wealthy and self-defeating push for austerity that is

floors—requires fiscal capacity. While the politically connected, and challenging on the horizon if not already here. Or we

COVID-19 crisis has exposed severe gaps in corporate accounts for potential transfer can stumble zombie-like through this

coverage and adequacy and underscored mispricing (Moore and Prichard 2020). crisis and leave ourselves exposed to

the urgency of investing in social protection and unprepared for future shocks.

systems, it has also clearly shown the global While domestic resource mobilisation

inequities in fiscal capacity. must remain the cornerstone of national

social protection systems, for low-income Durán Valverde, Fabio, José Pacheco-Jiménez,

Taneem Muzaffar, and Hazel Elizondo-Barboza.

Nearly 90 per cent of the global fiscal countries international support is also 2020. “Financing Gaps in Social Protection: Global

response to the COVID-19 crisis has taken critical, especially in the current context of Estimates and Strategies for Developing Countries

place in advanced countries (averaging falling commodity prices, disruptions in in Light of COVID-19 and Beyond.” Working Paper.

Geneva: International Labour Office. . Accessed 2 March 2021.

domestic product—GDP). Shockingly, less

than 3 per cent of the total global stimulus It is equally important that countries ILO. 2019a. “Extending Social Security Coverage

to Workers in the Informal Economy: Policy

has occurred in lower-middle-income and are able to sustain their levels of social Resource Package.” International Labour

low-income countries, creating a ‘stimulus spending when the immediate health Organization Social Protection website.

The International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth | Policy in Focus 15Accessed 19 January 2021. . Can Governments of Low-Income Countries

Create More Tax Revenue?” In The Politics

ILO. 2019b. “Extending Social Security to Self- of Domestic Resource Mobilization for Social

Employed Workers: Lessons from International Development, edited by Katja Hujo, 109–138.

Experience.” Issue Brief, No. 4/2019. . Accessed 19 January 2021.

Kidd, Stephen, and Diloá Athias. 2019. “Hit and

ILO. 2020a. “Extending Social Protection to Miss: An Assessment of Targeting Effectiveness

Informal Workers in the COVID-19 Crisis: Country in Social Protection.” Working Paper. Sidcup, UK:

Responses and Policy Considerations.” Social Development Pathways, and Uppsala, Sweden:

Protection Spotlight, 14 September. Geneva: Church of Sweden. .

International Labour Organization. . Accessed 19 January 2021.

Packard, Truman, Ugo Gentilini, Margaret Grosh,

ILO. 2020b. “Financing Gaps in Social Protection: Philip O’Keefe, Robert Palacios, David A. Robalino,

Global Estimates and Strategies for Developing and Indhira Santos. 2019. “Protecting All: Risk-

Countries in Light of COVID-19 and Beyond.” Sharing for a Diverse and Diversifying World

Social Protection Spotlight, 17 September. Geneva: of Work.” White Paper. Washington, DC: World

International Labour Organization. Accessed 19 Bank. . Accessed 19 January 2021.

World of Work. Sixth Edition. Updated Estimates

and Analysis. Geneva: International Labour

Organization. .

International Labour Organization (ILO).

Accessed 19 January 2021.

2. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

ILO. 2020d. “COVID-19 Crisis and the Informal of 1948 (Arts 22 and 25) and the International

Economy: Immediate Responses and Policy Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural

Challenges.” ILO Brief, May. Geneva: International Rights of 1966 (Arts 9 and 11) recognise social

Labour Organization. . Accessed 19 January 2021. and employers of the ILO’s 187 Member States,

highlight the need to extend social protection

ILO. 2020e. “Social Protection Responses to the coverage—notably, the Social Protection Floors

COVID-19 Pandemic in Developing Countries: Recommendation of 2012 (No. 202) and the

Strengthening Resilience by Building Universal Transition from the Informal to the Formal

Social Protection.” Social Protection Spotlight, Economy Recommendation of 2015 (No. 204).

May. . Accessed 19 security as a human right and the general

January 2021. responsibility of the State to guarantee the

due provision of adequate benefits and the

Mkandawire, Thandika. 2005. “Targeting and sustainability of social protection systems.

Universalism in Poverty Reduction.” SPD Working 3. People who are in poor health and older are

Paper, No.23. Geneva: United Nations Research more likely to become affiliated, while those

Institute for Social Development. . Accessed 2 March 2021. not see a reason for doing so.

“ We can turn the

COVID-19 crisis into an

opportunity to build

robust, comprehensive

and universal social

protection systems and

resist the self-defeating

push for austerity that is

on the horizon if not

already here.

Photo: Acácio Pinheiro/Agência Brasília. Mother and her child during the COVID-19 pandemic, Brasília, Brazil, 2020

.

16You can also read