Treatment of acute myocardial infarction in Peru and its relationship with in-hospital adverse events: Results from the Second Peruvian Registry ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Archivos Peruanos de Cardiología y Cirugía Cardiovascular

Arch Peru Cardiol Cir Cardiovasc. 2021;2(2):113-122.

Original Article

Treatment of acute myocardial infarction in Peru and its relationship

with in-hospital adverse events: Results from the Second Peruvian

Registry of ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (PERSTEMI-II)

Manuel Chacón-Diaz 1,a*; René Rodríguez Olivares 1,a; David Miranda Noé 1,a; Piero Custodio-Sánchez 1,b;

Alexander Montesinos Cárdenas 1,c; Germán Yábar Galindo 1,d; Aida Rotta Rotta 1,e; Roger Isla Bazán1,f; Paol Rojas de la Cuba 1,d;

Nassip Llerena Navarro 1,g; Marcos López Rojas1,f; Mauricio García Cárdenas 1,h; Akram Hernández Vásquez 2,i

Received: April 17, 2021

Accepted: may 19, 2021 ABSTRACT

Authors’ affiliation Background. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), is an important cause of morbidity and mortality

1

Cardiologist

2

Research physician worldwide, and myocardial reperfusion, when adequate, reduces the complications of this entity. The aim of the study

a

National Cardiovascular Institute

was to describe the clinical and treatment characteristics of STEMI in Peru and the relationship of successful reperfusion

INCOR, EsSalud, Lima, Peru.

b

Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo Na- with in-hospital adverse events. Materials and methods. Multicenter, prospective cohort of STEMI patients attended

tional Hospital, EsSalud, Chiclayo,

Peru. during 2020 in public hospitals in Peru. We evaluated the clinical and therapeutic characteristics, in-hospital adverse

c

Adolfo Guevara Velasco National events, and the relationship between successful reperfusion and adverse events. Results. A total of 374 patients were

Hospital, EsSalud, Cusco, Peru.

d

Guillermo Almenara National included, 69.5% in Lima and Callao. Fibrinolysis was used in 37% of cases (pharmacoinvasive 26% and fibrinolysis

Hospital, EsSalud, Lima, Peru.

alone 11%), primary angioplasty with < 12 hours of evolution in 20%, late angioplasty in 9% and 34% did not access

e

Cayetano Heredia National

Hospital, MINSA, Lima, Peru. adequate reperfusion therapies, mainly due to late presentation. Ischemia time was longer in patients with primary

f

Alberto Sabogal National Hospi-

tal, EsSalud, Callao, Peru. angioplasty compared to fibrinolysis (median 7.7 hours (IQR 5-10) and 4 hours (IQR 2.3-5.5) respectively). Mortality was

g

Carlos Alberto Seguín Escobedo 8.5%, the incidence of post-infarction heart failure was 27.8% and of cardiogenic shock 11.5%. Successful reperfusion

National Hospital, EsSalud,

Arequipa, Peru was associated with lower cardiovascular mortality (RR:0.28; 95%CI: 0.12-0.66, p=0.003) and lower incidence of heart

h

Hipólito Unanue Hospital, MINSA, failure during hospitalization (RR: 0.61; 95%CI: 0.43-0.85, p=0.004). Conclusions. Fibrinolysis continues to be the most

Lima, Peru.

i

San Ignacio de Loyola University, frequent reperfusion therapy in public hospitals in Peru. Shorter time from ischemia to reperfusion was associated

Lima, Peru.

with reperfusion success and, in turn, with fewer in-hospital adverse events.

*Correspondence

Coronel Zegarra street 417, Jesús

María, Lima, Peru.

Keywords: Myocardial Infarction; Fibrinolysis; Angioplasty; Mortality; Heart Failure; Peru.

Mail

manuelchacon03@yahoo.es

Conflicts of interest

None.

RESUMEN

Financing

Self-financing.

DOI: 10.47487/apcyccv.v2i2.132 Tratamiento del Infarto Agudo de Miocardio en el Perú y su Relación Con

Eventos Adversos Intrahospitalarios: Resultados del Segundo Registro

Peruano de Infarto de Miocardio con Elevación del segmento ST (PERSTEMI-II)

Antecedentes. El infarto de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (IMCEST), es una de las principales

causas de morbimortalidad a nivel global, la reperfusión adecuada del miocardio consigue disminuir las

complicaciones de esta entidad. El objetivo del estudio fue describir las características clínicas y terapéuticas

del IMCEST en el Perú y la relación de la reperfusión exitosa con los eventos adversos intrahospitalarios.

Materiales y métodos. Cohorte prospectiva, multicéntrica de pacientes con IMCEST atendidos durante el

año 2020 en hospitales públicos del Perú. Se evaluaron las características clínicas, terapéuticas y eventos

adversos intrahospitalarios, además de la relación entre la reperfusión exitosa del infarto y los eventos

adversos. Resultados. Se incluyeron 374 pacientes, 69,5% en Lima y Callao. La fibrinólisis fue usada en

37% de casos (farmacoinvasiva 26% y sola 11%), angioplastia primaria con < 12 h de evolución en 20%,

angioplastia tardía en 9% y 34% no accedieron a terapias de reperfusión adecuadas, principalmente por

presentación tardía. El tiempo de isquemia fue mayor en pacientes con angioplastia primaria en comparación

a fibrinólisis (mediana 7,7 h [RIQ 5-10] y 4 h [RIQ 2,3-5,5] respectivamente). La mortalidad fue de 8,5%, la

incidencia de insuficiencia cardiaca posinfarto fue de 27,8% y de choque cardiogénico de 11,5%. El éxito de

la reperfusión se asoció con menor mortalidad cardiovascular (RR: 0,28; IC95%: 0,12-0,66, p=0,003) y menor

incidencia de insuficiencia cardiaca (RR: 0,61; IC95%: 0,43-0,85, p=0,004). Conclusiones. La fibrinólisis sigue

siendo la terapia de reperfusión más frecuente en hospitales públicos del Perú. El menor tiempo de isquemia

a reperfusión se asoció con el éxito de esta y, a su vez, a menores eventos adversos intrahospitalarios.

Palabras clave: Infarto de Miocardio; Fibrinólisis; Angioplastia; Mortalidad; Insuficiencia Cardiaca; Perú.

EsSalud | 113Treatment of acute myocardial infarction in Peru

W

orld Health Organization (WHO) establishes that the during 2020, in whom the clinical, diagnostic and treatment

leading cause of death worldwide is atheroesclerotic characteristics of infarction, as well as complications and in-

disease, and that around 30% of reported deaths are hospital mortality were evaluated. Patients with non-ST elevation

caused by ischemic cardiomyopathy , the impact is greater than

(1)

myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), non-persistent STEMI and

those produced by infections and cancer, with mortality predicted patients with Takotsubo syndrome were excluded.

to increase by 36% by 2030 (1,2). Within this etiology, one of its most

Data collection (prior informed consent) was made

frequent presentations is the ST-segment elevation myocardial

directly from the medical record to an electronic database

infarction (STEMI). In the United States, STEMI represents 25-40%

of all myocardial infarction cases (3), with an in-hospital mortality of designed for this purpose (http://40.77.71.10/www/Perstemi2/).

5-6% and 7-18% one year after the event. Approximately 30% are The study variables included: general variables (age, sex, home

women, 23% have diabetes mellitus and up to 7% do not receive city); epidemiological (pathological history, cardiovascular risk

reperfusion therapy (4). factors); clinical (symptoms, electrocardiogram characteristics,

Killip Kimball classification); access to reperfusion, type of

Myocardial reperfusion in the acute phase modified natural reperfusion, times to first medical contact and time from

history of STEMI due to reduction of mortality and the prevention or

ischemia to reperfusion, in-hospital treatment and on discharge,

reduction of the occurrence of heart failure secondary to myocardial

in-hospital complications and mortality (in-hospital and 30 days’

necrosis. The accepted time window for reperfusion of STEMI is up

mortality).

to 12 hours from the onset of symptoms; in special clinical situations

like hemodynamic instability or very extensive myocardial areas at We considered reperfusion therapy as the administration

risk it extends beyond 12 h . There are two basic reasons why many

(5) of some therapy of this type in the first 12 h of symptons, late

patients do not receive reperfusion: first the delay in treatment reperfusion if primary percutaneous coronary intervention

and loss of the adequate time window to obtain reperfusion, and (pPCI) was performed between 12 to 48 h, and patient without

second the lack of an adequate diagnosis (6). access to reperfusion if a case did not receive any reperfusion

treatment (6). Reperfusion success with fibrinolysis was defined

In Latin America, according to the ARGEN-IAM-ST registry

as the ST segment fall > 50% after ninety minutes of starting the

(Argentina), 83.5% of patients with STEMI received reperfusion

drug, and in case of pPCI as the post-intervention TIMI 3 flow

therapy (78.3% with primary angioplasty and 16% with fibrinolytics)

of the infarct related artery (IRA). Both cases were considered

with an in-hospital mortality of 8.8% (7). On the other hand, the

as “reperfused” cases for statistical analysis, patients without

RENASICA-II study (Mexico), identified that reperfusion therapy

was 32% with coronary angioplasty and 37% with fibrinolytics, access to reperfusion was considered “non-reperfused”.

with a hospital mortality of 10% (8). In Peru, in 2016, the PERSTEMI Categorical variables were expressed in frequency and

registry found that fibrinolysis was used in 38% of cases (12.9% percentages, numerical variables in means and medians and their

pharmacoinvasive strategy), primary angioplasty in 29% and 33% respective measures of dispersion according to their distribution.

did not receive reperfusion during the first 12 h of STEMI evolution The evaluation of association between two categorical variables

and in-hospital mortality was 10.1% (9).

was carried out using chi-square test, and between numerical

Given these data, the second national registry of variables using student’s t test (normal distribution) or Man-

myocardial infarction PERSTEMI-II, sought to evaluate the evolution Whitney U test (non-parametric distribution). Generalized

of the epidemiological profile of STEMI in Peru four years after the linear models of the binomial family with log link function were

first registry, to know the most prevalent reperfusion strategies performed to estimate the crude and adjusted relative risk (RR)

in our country, the main complications of STEMI and the adverse and their respective CI 95% of the factors associated to successful

events at one-year follow-up. This article describes the presentation reperfusion and its impact on the frequency of in-hospital

characteristics and treatment of STEMI, and the relationship of adverse events. Statistical evaluation was performed using Stata

successful reperfusion with in-hospital adverse events. 14.0 program (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Materials and methods Results

PERSTEMI-II is a multicenter and prospective cohort Twenty-five hospitals from the public health system

of patients with STEMI treated in Peruvian public hospitals in Peru, were invited to participate in the registry, 17 of them

(Ministerio de Salud and EsSalud). The study protocol included all actively participated in the data collection. From January 1 to

patients older than 18 years with diagnosis of STEMI according December 31, 2020; 405 cases were registered in the system, of

to the fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction, treated which, incomplete cases or those with erroneous diagnosis were

114 | EsSaludArch Peru Cardiol Cir Cardiovasc. 2021;2(2):113-122.

excluded, leaving 374 patients as study population. Most (69.5%)

were registered in Lima and Callao cities, 88.5% were attended Table 1. Antecedents and risk factors of study population

in hospitals of EsSalud social security and 11.5% in hospitals of

Antecedents n %

the Ministerio de Salud (MINSA). A 67.4% of cases were referred

Arterial hypertension 198 52,9

to hospitals with higher resolution level to complete their

Dyslipidemia 198 52,9

reperfusion therapy.

Type 2 Diabetes mellitus 111 29,7

The number of cases decreased during the year due to Smoking 81 21,6

the influence of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (Figure 1). The 85% of Myocardial infarction 28 7,5

cases were men and the median age was 66 years (IQR: 58-74 Chronic kidney disease 28 7,5

years); the age of presentation in women was higher than that Chronic coronary syndrome 24 6,4

of men (71 and 65 years, respectively, p=0.01). The most frequent Cerebrovascular event 18 4,8

risk factors were arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia (Table 1). Hyperuricemia 12 3,2

Myocardial revascularization 12 3,2

Clinical presentation Heart failure 9 2,4

Typical angina was found in 93.8%, dyspnea in 29%,

atypical chest pain in 5.3%, syncope in 4% and cardiac arrest in

3.2%. Women had a higher proportion of atypical symptoms

than men (dyspnea 36.4% vs 27.9%; syncope 5.5% vs 3.8% and KK II in 27.3%; KK III 2.9% and KK IV in 4.3%. In the following hours,

atypical chest pain 9.1% vs 4.7%, respectively), although without 59.4% of patients remained in KK I; 27% KK II; 4% worsened to KK

statistical significance. III and 9.6% to KK IV. In general, time to first medical contact was

2.5 h (RIQ: 1-6) and time from ischemia to reperfusion was 5.3 h

The first electrocardiogram found 92.5% of cases in sinus

(RIQ: 3-9).

rhythm, 4.5% with high degree auricular-ventricular block and

2.9% with auricular fibrillation. The most frequent localization of

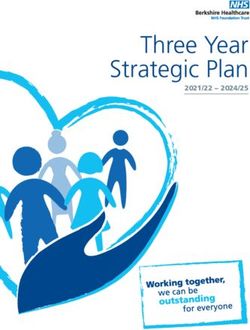

Reperfusion strategies (Main figure)

infarction was the anterior wall (antero-septal, anterolateral and

anterior) in 38.2%, followed by inferior wall (26.5%), extensive Two hundred five patients (55% of the study population)

anterior wall (18.7%), inferolateral (14.2%) and lateral (2.4%). The received some type of reperfusion in the first 12 hours: 131 (64%)

clinical condition at admission was Killip Kimball (KK) I in 65.5%; fibrinolysis and 74 (36%) pPCI.

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Figure 1. Number of STEMI cases reported by month during 2020.

EsSalud | 115Treatment of acute myocardial infarction in Peru

Thirty-two patients (8.2%) received late reperfusion 12 to with alteplase), and was the most frequent reperfusion therapy

24 hours after the infarction (3 fibrinolysis and 28 pPCI), mainly (56%). The success rate was 66% (90 patients).

due to: heart failure (15 cases), large myocardial infarctions

As part of a pharmacoinvasive strategy after a successful

(extensive anterior or inferolateral) without heart failure (8 cases)

fibrinolysis, 77% (69 patients) underwent coronary angiography

and unknown reason (8 cases). In 6 patients (1.6%), the pPCI

and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) between 3 to 24

was performed after 24 h to 48 h of evolution (in 5 patients with

h (routine early PCI strategy), which means 50% of all patients

post-infarction heart failure). In four cases, ischemia time was not

who underwent fibrinolysis and 18% of the cohort. The success

registered (3 fibrinolysis and 1 pPCI). One hundred twenty-eight

patients (34%) did not receive any reperfusion therapy, mainly due of PCI in this group was 99%. In the 47 cases where fibrinolysis

to late presentation (Figure 2). was unsuccessful, rescue PCI was performed in 60% (7.5% of

total cohort).

Fibrinolysis

From above, it can be deduced that 29% of patients who

One hundred thirty-seven patients (37% of the underwent fibrinolysis (40 cases) did not received a subsequent

population) received fibrinolysis as first reperfusion strategy (all invasive therapy (the majority from the interior of the country

STUDY POPULATION IN-HOSPITAL ADVERSE EVENTS

Lima and Callao

Metropolitan Area

69.5 % Rest of the

country

30.5% Death Cardiogenic Heart Failure

8.5% Shock 27,5%

11.5%

REPERFUSION STRATEGY

No reperfusion No reperfusion 34

Fibrinolysis + PCI 25.9

Primaria PCI 19.8

Fibrinolysis alone 11.0

PCI 12 - 48 hours 9.3

Reperfusion 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

%

TIME DELAY TO TREATMENT

Total time until fibrinolysis (Expressed as median)

4h

Symptoms First Medical

Onset Contact

1.5 h Fibrinolysis PCI capable center

arrival

2.5 h

Primary

3.5 h 1.2 h PCI

7.2 h

Total time until Primary PCI

Main figure. Reperfusion, delays in care attention and in-hospital events in STEMI - PERSTEMI II Registry. Peru 2020.

116 | EsSaludArch Peru Cardiol Cir Cardiovasc. 2021;2(2):113-122.

35

30.9

30

25

20.3

20

15 13.8

12.2 12.2

10 8.1

6.5

5 3.2

1.6

0

Presentation Lack of Presentation Presentation Lack of Error Contraindication Refusal of Others

24 - 72 h angiographer > 12 h > 72 h fibrinolytic diagnosis to fibrinolysis patient

Figure 2. Reasons for not applying reperfusion therapies in STEMI (values expressed as percentages).

and in hospitals of MINSA) that represented 11% of the study 5 due to cardiogenic shock, 4 due to high risk anatomy for PCI

population. and 2 for mechanical complication.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention A 26% of patients did not have success in reperfusion

therapy, when added to the patients without access to any

pPCI during the first 12 h of evolution was performed reperfusion, we found 192 patients (51.3% of the population)

in 74 patients (19.8% of the population) and its success rate who did not achieve optimal myocardial reperfusion. Analyzing

by coronary arteriography was 73%. In 34 patients (9% of the the factors associated with successful reperfusion in the adjusted

population), it was performed late pPCI and its success rate was model, we found that two factors were associated with it: treatment

54% (p=0.078). Time to first medical contact, time from ischemia in a hospital from EsSalud (RR: 2.12, p=0.006, CI95%: 1.23-3.65) and

to pPCI and Door-To-Balloon Time are detailed in Table 2. total time from ischemia to reperfusion 12 h) (Table 3).

anterior descending artery in 62%, right coronary artery in

31%, circumflex artery in 6%, and no IRA was found in 1%

(myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries Table 2. Delays in reperfusion treatment according to the

(MINOCA)). The percentages of pre-PCI TIMI flow 0,1,2 and strategy used in the first 12 h of evolution.

3 was 33%, 18%, 21% and 28%, respectively; post-PCI was Fibrinolysis Primary PCI

4%, 7%, 13% and 76%, respectively. Stents were placed in Median Median

IQR IQR

92% of cases that underwent coronary arteriography, mainly (hours) (hours)

drug-eluting stents (96%). A 51% of patients (104 cases) had TFMC 1.5 0,7-3 2 1-4

multivessel coronary disease, of them, 65% had intervention TTI 4 2.3-5.5 7.7 5-10

performed in non-IRA vessels: 26% in the same procedure and DNT/DBT 1.5 0.7 – 2.6 1.2 1-1.5

73% deferred before medical discharge (97% routine and only PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. TFMC: Time to first medical con-

tact time. TTI: total from ischemia to reperfusion. DNT: Door-to-needle-

3% based on ischemia/viability assessment). Only 17 cases time. DBT: Door-to-balloon time. IQR: Interquartile range.

(4.5%) underwent cardiac surgery, 6 due to unsuccessful PCI,

EsSalud | 117Treatment of acute myocardial infarction in Peru

Medication and in-hospital adverse events cardiogenic shock during hospitalization after the admission, a

value higher than that reported by Farré et al. during the Code

The mean length of hospital stay was 7 days (IQR:5-11).

IAM registry (20)

. Due to the high mortality associated with this

Double antiplatelet therapy was used in 95%, beta-blockers in

81%, ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blocker in 69%, statins condition, especially in our country as reported by a recent

in 94%, diuretics in 21% and antialdosteronic agents in 25%. national single-center registry, it is important to identify, prevent

and follow-up this patients (21,22).

In-hospital mortality was 8.6% (32 cases), 6.7% due to

cardiac cause and 1.8% non-cardiac cause. Incidence of post- In relation to PERSTEMI I, there was a reduction in the

infarction heart failure was 27.8%, cardiogenic shock 11.5%, post- number of patients undergoing some type of reperfusion

infarction angina 7.8%, mechanical complication 2.9%, cardiac therapy during the first 12 h (55% vs 67%), and late presentation

arrest 8.5%, cerebrovascular event 0.8% and major bleeding was the main recurrent cause. This reperfusion rate was

2.9%. The mortality at 30-day follow-up was 9.1% (34 cases). It is lower than reported by the FAST AMI registry with 77% or

important to mention that 16 patients (4.2%) were attended with ARGEN-IAM-ST (88%), but higher than reported by other Latin

active SARS-COV2 infection. American registries such as RESISST (40.7%) and RENASICA

Reperfusion success was the variable that notably III (52.6%) . These differences express the different

(15,16,18,23)

influenced the presence of in-hospital adverse events, both in the organizational realities of health system and logistical aspects

crude analysis and in analysis adjusted for age, sex and underlying to offer reperfusion therapy. In Peru, there is only one public

diseases (Table 4). hemodynamic room with permanent care for management of

patients with STEMI, in the National Cardiovascular Institute

(INCOR), reality that has not been changed since 4 years ago.

Discussion

In PERSTEMI I, the time to first medical contact was 2 h (IQR:

The information obtained from the clinical records and 1- 4.5) while in PERSTEMI II was 2.5 h (IQR: 1 - 6), a result that could

their temporal comparison have become fundamental tools with be interpreted as an expression of the absence of educational

the aim of improving the quality of care of patients with STEMI (10). programs at national level about the early recognition of infarction

The percept that you cannot improve what you cannot measure, symptoms and search for medical attention, as well as due to the

describes the central role of registries in reducing mortality in

COVID-19 pandemic that motivated the late presentation to the

patients with STEMI worldwide (11). The PERSTEMI II registry lets

hospital due to fear of contagion (24,25). The delay in the application

us know and compare the epidemiological characteristics and

of fibrinolysis (1.5h) and pPCI (4.7h) after the first medical contact

clinical outcomes of patients with STEMI with respect to that

(delay in the system), showed the ineffectiveness of the public

reported by PERSTEMI (2016-2017) (9).

health system in the management of STEMI.

We found a reduction in the number of patients attended

Similar to that reported by PERSTEMI I, fibrinolysis in the

during the study year, which occurred during the COVID-19

first 12 h remained the most used reperfusion strategy (37% vs

pandemic that has led to a reduction of cases of STEMI worldwide,

38%). However, we found a decrease in the percentage of pPCI

especially at the beginning of the pandemic (decreasing of 59%

(19.8% vs 29%), which can be explained by the influence of the

in the number of admissions at the beginning of the emergency

COVID-19 pandemic on the decision of type of reperfusion,

state in Peru) and probably related to patients’ fear of being

since the fibrinolysis needs lower logistical demand and has

admitted to the hospital (12-14). The majority of cases were reported

in the cities of Lima and Callao and in centers of the EsSalud social been recommended by some scientific institutions (26). Similar to

security, similar to what was observed in PERSTEMI I. what was reported by De Luca et al. (27) who found a reduction of

19% in pPCI during the COVID-19 pandemic in 40 high-volume

Typical angina and dyspnea remained the most frequent European centers.

presentations and atypical symptoms were prevalent in women.

Regarding the location of the infarction, anterior wall remained In addition to the reduction of pPCI as reperfusion

the most frequent, similar to what was reported by the RENASICA therapy, the percentage of patients with TIMI 3 flow in coronary

III and PHASE-MX registries, but different to what was evidenced arteriography decreased markedly in relation to PERSTEMI I (67%

by the ARGEN-IAM-ST and RESISST registries (Argentine and vs 82%), which can be explained by the intervention of more

Brazilian respectively), where the compromise of the inferior wall patients with late presentation (> 12h after the first symptoms)

was the most frequent (15,16,18,19). in this registry.

We highlight the progression of hemodynamic Fibrinolysis success rate remained close to 70%, which

deterioration in almost 10% of patients who developed reaffirms the usefulness of this strategy in the current context.

118 | EsSaludArch Peru Cardiol Cir Cardiovasc. 2021;2(2):113-122.

Table 3. Factors associated with the success of reperfusion therapy in STEMI

Crude model Adjusted model*

Characteristic

RR (CI 95%) p value RRa (CI 95%) p value

Sex

Female Reference

Male 0.76 (0.53-1.08) 0.122 0.95 (0.74-1.24) 0.718

Age (years-old) 1.00 (0.99-1.00) 0.405 Not included

Smoking

No Reference

Yes 1.33 (1.07-1.65) 0.009 1.07 (0.92-1.23) 0.381

Diabetes mellitus

No Reference

Yes 0.82 (0.64-1.06) 0.127 1.02 (0.87-1.21) 0.728

Arterial Hypertension

No Reference Reference

Yes 0.83 (0.68-1.02) 0.084 0.97 (0.83-1.12) 0.640

Chronic Kidney Disease

No Reference Not included

Yes 0.87 (0.56-1.36) 0.544

Chronic Heart Failure

No Reference Not included

Yes 0.68 (0.27-1.72) 0.416

Place of health establishment

MINSA Reference Reference

EsSalud 2.50 (1.38-4.51) 0.002 2.12 (1.23-3.65) 0.006

Place of care

Outside Lima city Reference Reference

Lima city 1.26 (0.98-1.62) 0.069 1.04 (0.86-1.27) 0.676

Transfer/reference

No Reference Reference

Yes 1.35 (1.05-1.73) 0.018 0.93 (0.76-1.14) 0.505

Ischemia time

< 6 hours 1.46 (1.11-1.92) 0.007 1.60 (1.12-2.28) 0.010

6-12 1.29 (0.96-1.75) 0.096 1.34 (0.95-1.89) 0.099

>12 hours Reference Reference

Time to first contact 0.91 (0.88-0.94)Treatment of acute myocardial infarction in Peru

Table 4. Association between successful reperfusion in STEMI and in-hospital outcomes

Non Adjusted

Reperfused Crude model

reperfused model*

Characteristic

n=182 (48,7) n=192 (51,3) RR (CI 95%) p value RRa (CI 95%) p value

General mortality 6 (3.3) 26 (13.5) 0.24 (0.10-0.58) 0.001 0.28 (0.12-0.66) 0.003

Cardiovascular mortality 5 (2.8) 20 (10.4) 0.26 (0.10-0.69) 0.007 0.31 (0.13-0.74) 0.009

Non cardiac mortality 1 (0.6) 6 (3.1) 0.18 (0.02-1.45) 0.106 0.17 (0.02-1.55) 0.116

Symptomatic heart failure 36 (19.8) 68 (35.4) 0.56 (0.39-0.79) 0.001 0.61 (0.43-0.85) 0.004

Cardiogenic shock 10 (5.5) 33 (17.2) 0.32 (0.16-0.63) 0.001 0.35 (0.18-0.68) 0.002

Post-infarction angina 7 (3.9) 22 (11,5) 0.34 (0.15-0.77) 0.010 0.33 (0,14-0.80) 0.014

Mechanical complications 2 (1.1) 9 (4.7) 0.23 (0.05-1.07) 0.062 0.36 (0.08-1.65) 0.188

Cardiac arrest 9 (5.0) 23 (12.0) 0.41 (0.20-0.87) 0.020 0.47 (0.23-0.96) 0.038

Major bleeding** 4 (2.2) 7 (3.7) 0.60 (0.18-2.03) 0.414 0.85 (0.25-2.91) 0.802

* Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and chronic kidney disease.

**Major bleeding: TIMI definition: intracranial hemorrhage. Decrease of hemoglobin > 5 g/dL., decrease of hematocrit > 15%.

RR: relative risk.

The percentage of patients with this strategy was higher in this constant training at the first level of care, to have a single integrated

study compared to 12.9% in PERSTEMI I, which finally makes health system for management of STEMI with referral centers

the systematic early percutaneous coronary intervention and more complex centers for intervention, all connected by an

consolidated as an effective strategy for the reality of our country. adequate transportation system; this is the only way to achieve

higher successful reperfusion rates and fewer adverse events.

As reported by multiple international registries, we

confirmed that reduction in total ischemia time and time to first As limitations of the study we can say that, although

medical contact were statistically significantly associated with the PERSTEMI II registry was proposed to be applied at national

successful coronary reperfusion . Late presentation and the

(28)

level, the data was mainly obtained from public hospital centers

absence of integrated networks for the management of STEMI are in the city of Lima and Callao, so its conclusions not necessarily

problems associated with prolonged times in our country, and in reflect the situation of patients treated by STEMI at national level.

developing countries in general, which prevent improving clinical

Likewise, it is important to consider the influence of the COVID-19

outcomes (29).

pandemic in the care attention and clinical outcomes of patients

In-hospital mortality was lower than reported by with STEMI in this registry.

PERSTEMI I (8.6% vs 10.1%), which is comparable to that

observed by other registries such as ARGEN-IAM-ST (8.7%), Rio

Grande Brazil (8.9%) and RENASICA III (8.7%), but higher than that Conclusions

reported by PHASE-MX with 6.2% for CPI and 4.8% for systematic

STEMI in Peru is presented with more frequency in

early percutaneous coronary intervention (15,17,18,19). Mortality from

men in the seventh decade of life and the most prevalent risk

cardiac cause remained the most frequent.

factors were arterial hypertension and dyslipidemia. The most

More than half of study population did not receive frequent reperfusion therapy was fibrinolysis. The reason

reperfusion or it was not successful, which in the regression analysis for lack of reperfusion therapy administration remained the

was interpreted as more adverse events including death in the late admission of patients in health services with capacity to

evolution. Therefore, it is necessary to reduce the times of attention perform reperfusion. Success of reperfusion was associated

of STEMI, which includes education for general population, with lower cardiovascular mortality, heart failure, post-infarction

120 | EsSaludArch Peru Cardiol Cir Cardiovasc. 2021;2(2):113-122.

angina and cardiac arrest. It is necessary to create an integrated Guillermo Almenara -Lima), Aida Rotta (Hospital Cayetano

program for management of STEMI at national level to get better Heredia - Lima), Javier Chumbe (Hospital Arzobispo Loayza

clinical outcomes. - Lima), Rubén Azañero (Hospital 2 de mayo, Lima), Mauricio

García (Hospital Hipólito Unanue, Lima), Carlos Barrientos

Authors‘ contribution: MCHD: conception of the article, data

(Hospital MINSA-Huancayo), Jorge Martos (Hospital MINSA

collection, analysis, writing. RRO, DMN, PCS: data collection,

Cajamarca), Alexander Montesinos, Fernando Gamio

analysis, writing. AMC,GYG,ARR,RIB,PRC,NLN,MLR,MG: data

(Hospital Adolfo Guevara-Cusco), Nassip Llerena (Hospital

collection, writing. AHV: analysis, writing.

Carlos Seguín-Arequipa), Piero Custodio (Hospital Almanzor

Acknowledgement: Dr. Carlos Pereda for the central image. Aguinaga-Chiclayo), Julio Uribe (Hospital Essalud- Iquitos),

Walter Saavedra (Hospital Essalud- Tumbes), Fernando Allende

(Hospital Essalud- Puno), Pamela Mejía (Hospital Essalud-

PERSTEMI II investigators: Roger Isla, Luis López (Hospital Tacna), René Rodriguez, David Miranda y Manuel Chacón

Alberto Sabogal - Callao), Paol Rojas, Germán Yabar (Hospital (Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular, INCOR).

References

1. World Health Statistics 2011. WHO’s annual compilation of data from 11. Brindis RG, Bates ER, Henry TD. Value of Registries in ST-Segment-

its 193 Member States, including a summary of progress towards Elevation Myocardial Infarction Care in Both the Pre-Coronavirus

the health-related Millennium Development Goals and Targets. Disease 2019 and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Eras. J Am Heart

Disponible en: http://www.who.com Assoc. 2021;10:e019958. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.019958.

2. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and 12. Custodio-Sánchez P, Miranda D, Murillo L. Impacto de la Pandemia

stroke statistics—2009 update: a report from the American por COVID-19 sobre la Atención del Infarto de Miocardio ST Elevado

Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics en el Perú. Arch Peru Cardiol Cir Cardiovasc. 2020;1:87-94. DOI:

Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119: e21-181. DOI: 10.1161/

10.47487/apcyccv.v1i2.22.

CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191261

13. Rodriguez-Leor O, Cid-Álvarez B, Ojeda S, et al. Impacto de la

3. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline

for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report pandemia de COVID-19 sobre la actividad asistencial en cardiología

of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart intervencionista en España. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:82-89. DOI:

Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 10.24875/RECIC.M20000120.

2013;61: e78 –140. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019

14. Garcia S, Albaghdadi M, Meraj P, et al. Reduction in ST-Seg-ment

4. Gharacholou SM, Alexander KP, Chen AY, et al. Implications and Elevation Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory Activations in the

reasons for the lack of use of reperfusion therapy in patients with United States during COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol.

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the 2020;75(22):2871-72. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011.

CRUSADE initiative. Am Heart J. 2010; 159:757– 63. DOI: 10.1016/j.

ahj.2010.02.009 15. D´Imperio H, Gagliardi J, Charask A, et al. Infarto agudo de miocardio

con elevación del segmento ST en la Argentina. Datos del registro

5. Fuster V, Badimon L, Badimon JJ, Chesebro JH. The pathogenesis continuo ARGEN-IAM-ST. Rev Argen Cardiol. 2020;88:297-307. DOI:

of coronary artery disease and the acute coronary syndromes 10.7775/rac.es.v88.i4.18501.

(part I). N Engl J Med.1992;326:242-50, 310-8. DOI: 10.1056/

NEJM199201233260406 16. Filgueiras NM, Feitosa GS, Fontoura DJ, et al. Implementation of a

Regional Network for ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

6. Ibañez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. Management of acute myocardial

infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST segment (STEMI) Care and 30-Day Mortality in a Low-to Middle-Income City in

elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST segment Brazil: Findings From Salvador´s STEMI Registry (RESISST). J Am Heart

elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Assoc. 2018;7:e008624. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008624.

Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2017; 29:2909-45.

17. Alves L, Polanczyk CA. Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction:

7. Gagliardi J, CAHARASK A, Perna E, et al. Encuesta nacional de infarto A Population-Based Registry. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2020;115:916-924.

agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST en la República DOI: 10.36660/abc.20190573.

Argentina (ARGEN-IAM-ST) Rev Argent Cardiol 2016; 84:548-57 DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7775/rac.es.v84.i6.9508 18. Martinez-Sanchez C, Borrayo G, Carrillo J, et al. Clinical management and

hospital outcomes of acute coronary syndrome patients in Mexico: The

8. García A, Jerjes-Sánchez C, Martínez BP, et al. Renasica II. Un registro Third National Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (RENASICA III).

mexicano de los síndromes coronarios agudos. Arch Cardiol Mex. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2016;86:221-232. DOI: 10.1016/j.acmx.2016.04.007.

2005;75(supl 2) S6-S19.

19. Araiza-Garaygordobil D, Gopar-Nieto R, Cabello-López A.

9. Chacón M, Vega A, Aráoz O, et al. Características epidemiológicas

Pharmacoinvasive Strategy vs Primary Percutaneous Coronary

del infarto de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST en Perú:

Intervention in Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction:

resultados del PEruvian Registry of ST-segment Elevation Myocardial

Infarction (PERSTEMI). Arch Cardiol Mex. 2018; 88(5):403-12. DOI: Results From a Study in Mexico City. CJC Open. 2021;3:409-418.

10.1016/j.acmx.2017.11.009 20. Farré N, Fort A, Tizón-Marcos H, et al. Epidemiology of heart failure in

myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty: Analysis of

10. Higa CC, D´Imperio H, Blanco P, et al. Comparación de dos registros EsSalud | 121

argentinos de infarto de miocardio: SCAR 2011 y ARGEN-IAM ST 2015. the Codi IAM registry. REC Cardio Clin. 2019;54:41-49. DOI: 10.1016/j.

Rev Argent Cardiol. 2019;87:19-25. DOI: 10.7775/rac.es.v87.i1.14515. rccl.2019.01.014.Treatment of acute myocardial infarction in Peru

21. Guzmán-Rodríguez R, Polo-Lecca G, Aráoz-Tarco O, et al. Características 25. Tam C, Cheung K, Lam S, et al. Impact of Coronavirus Disease

Actuales y Factores de Riesgo de Mortalidad en Choque Cardiogénico 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak on ST-Segment-Elevation Myocar-dial

por Infarto de Miocardio en un Hospital Latinoamericano. Arch Peru Infarction Care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes.

Cardiol Cir Cardiovasc. 2021;2:35-43. DOI: 10.47487/apcyccv.v2i1.89. 2020;13(4):1-3. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631.

22. Zeymer W, Bueno H, Granger CB, et al. Acute Cardiovascular Care 26. Jing ZC, Zhu HD, Yan XW, et al. Recommendations from the Peking

Association position statement for the diagnosis and treatment of Union Medical College Hospital for the management of acute

patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur Heart J.

shock: A document of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association of 2020;41:1791-1794. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa258.

the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc 27. De Luca G, Verdoia M, Cercek M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic

Care. 2020;9:183-197. DOI: 10.1177/2048872619894254. on Mechanical Reperfusion for Patients With STEMI. Am Coll Cardiol.

23. Belle L, Cayla G, Cottin Y, et al. French Registry on Acute ST-elevation 2020;76:2321-30. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.546.

and non−ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction 2015 (FAST-MI 2015). 28. Ibañez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. Guía ESC 2017 sobre el tratamiento

Design and baseline data. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;110:366-378. del infarto agudo de miocardio en pacientes con elevación del

DOI: 10.1016/j.acvd.2017.05.001. segmento ST. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2017;70:1039-1045. DOI: 10.1016/j.

24. American College of Emergency Physicians. Public Poll: Emergency recesp.2017.10.048.

Care Concerns amidst COVID-19. US: ACEP. 2020. Disponible en: 29. Mehta S, Granger C, Lee Grines C, et al. Confronting system barriers for

https://www.emergencyphysicians.org/article/covid19/public- ST- elevation MI in low- and middle-income countries with a focus on

poll-emergency-care-concerns-amidst-covid 19. India. Indian Heart J. 2018;70:185-190. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2017.06.020.

122 | EsSaludYou can also read