The impact of Covid-19 and associated mobility restrictions on Arab South Partner Countries: the case of the Middle East-Gulf States corridor ...

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Funded by the European Union

EMM4 Policy Paper

The impact of Covid-19 and associated mobility

restrictions on Arab South Partner Countries:

the case of the Middle East-Gulf States corridorContents

Middle East countries’ dependency on Gulf migration 5

International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD)

Gonzagagasse 1

1010 Vienna, Austria Sanitary and other measures against the pandemic: foreign residents as prime targets 6

ICMPD Regional Coordination Office for the Mediterranean

Development House 4A, St Ann Street

FRN9010 Floriana

Migrants’ mobility and the Covid-19 pandemic 6

Malta

www.icmpd.org

Policies of migrants’ origin countries 9

Written by: Françoise de Bel-Air

ICMPD Team: Alexis McLean

Suggested Citation: ICMPD (2020), The Impact of Covid-19 and Associated Mobility Restrictions on The economic crisis generated by the Covid-19 pandemic and the drop in oil prices in Gulf States: what’s next? 10

Arab South Partner Countries: The case of the Middle East - Gulf States Corridor

This publication was produced in the framework of the EUROMED Migration IV (EMM4) programme. Conclusion 14

EMM4 is an EU-funded initiative implemented by the International Centre for Migration Policy

Development (ICMPD).

www.icmpd.org/emm4

© European Union, 2020

The information and views set out in this study are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and

bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be

made of the information contained therein.

Design: Pietro Bruni - bruni@toshi.ltd

2 3Introduction

The outbreak of the first Covid-19 cases in the Gulf States in early February 2020, and subsequent economic

downturn shed a new light on the MENA region’s dependency on, and vulnerability to migration to the six

Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Foreign workers locked up in infected labour camps, jobless, stranded

foreign citizens unable to leave the Gulf back to their home states, and massive forced exits of laid-off

labourers all underline the lack of freedom of movement for foreign residents enshrined in Gulf countries’

legal systems. Conversely, the reluctance of some governments to organise the repatriation of their nation-

als, for fear of importing Covid-19 cases to their territories, poses the question of migrants’ relations to their

home states. Meanwhile, the economic crisis pushed hundreds of thousands of guest labourers, suddenly

made redundant, back to their countries. The issue of migrants’ return and, more generally, that of the fu-

ture of labour migration to the Gulf States emerged. Using the crisis as an opportunity, GCC governments

currently hasten migrants’ replacement by nationals to curb citizens’ unemployment and address the “de-

mographic imbalance” between nationals and expatriates.

Using sending and receiving states’ official statistics and press statements, the paper outlines and analyses

the main consequences of mobility and travel control for migrants and migrant-sending countries of the

region. Focusing on Middle Eastern SPCs (Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon) mobility corridor with the GCC as

an example, the paper will discuss prominent mobility issues revealed by and arising from the crisis, from

the migrants’ and origin countries’ perspectives. The paper then articulates a set of recommendations for

national policymakers and the international community.

Middle East countries’ dependency on Gulf migration

A hub for international investment, trade and tourism, the GCC region channelled its hydrocarbon-induced

growth towards megaprojects, world-class events, and landmark cultural and other projects to attract a

larger share of international visitors and capital. Subsequent hikes in labour needs since the 2000s aggre-

gated about 30 million foreign citizens in the Gulf States by 2019, or 11% of the world’s total migrant stock.

1

That same year, on the eve of the Covid-19 crisis, foreign migrants made up more than a half (52%) of the

region’s resident population, while foreign workers made up between 57% and 95% of the Gulf countries’

workforces, respectively in Saudi Arabia and in Qatar.2

However, dependency on labour mobility goes both ways: the six countries polarise migration from Middle

Eastern Arab states: 43% of the 885,000 Lebanese expatriates worldwide, 60% of the 4.4 million Egyptian

expatriates and three-quarters of the 962,000 Jordanian expatriates were residing in the GCC region in the

mid-2010s,3 mostly in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait. Due to their large numbers, Egyptians in Gulf States

are found at all levels of occupation, including low-skilled. In Saudi Arabia in 2013, for instance, Egyptian ex-

1 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division (2019). International Migrant Stock 2019 (Unit-

ed Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2019)

2 https://gulfmigration.org/glmm-database/demographic-and-economic-module/.

3 Françoise De Bel-Air, Mapping ENI SPCs migrants in the Euro-Mediterranean region: An inventory of statistical sources, ICMPD,

Vienna, 2020.

4 5patriates’ five most common occupations were: general accountant, marketing specialist and livestock and Among these, however, foreign migrants have been initially overrepresented. In Saudi Arabia, for instance,

agricultural jobs. Lebanese and Jordanian expatriates are generally tertiary-educated and occupy skilled

4

expatriates make up 37% of the total resident population, but 73% of all confirmed Covid-19 cases, and 83%

and highly skilled positions.5 Migrants’ remittances made up, respectively 9%, 10.2 and 12.7% of Egypt’s, Jor- of the cases newly reported as of 20 April 2020.16 Migrants’ overrepresentation among the infected popula-

dan and Lebanon’s GDP in 2019, according to the World Bank.6 tion17 thus reveals the multifaceted precarity of most migrants in Gulf host states, who are often “frontline

workers” such as cashiers, delivery persons, up to highly-skilled medical personnel,18 for instance in Saudi

Sanitary and other measures against the pandemic: foreign residents as prime targets Arabia where Egyptians are many in such professions,19 or in Kuwait.20

The first cases of Covid-19 in the MENA region were reported in late January 2020 in the United Arab Emir- The sponsorship issue and mobility

ates. Gulf governments reacted swiftly to limit the spread of the virus, by supplying protective equipment

to the population and actively promoting physical distancing and barrier gestures, by preventing large The locking up of low-wage labourers in overcrowded compounds, where physical distancing, hygiene

gatherings -including religious prayers in mosques and the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina in February-, and isolation from infected individuals cannot be secured, also contributes to explaining the spread of the

by closing schools, public venues and “non-essential” workplaces, and by enforcing partial or total curfews pandemic among non-nationals.21 More generally, however, the impact of the Covid-19 on migrants was

as well as lockdowns by March. Prison sentences could be applied to contraveners. Free-of-charge testing compounded by the Gulf states’ legal, institutional setups and immigration policies. These ensure Gulf

and Covid-19 treatment were made available to all, irrespective of their legal status in the country, but it is

7

states governments’ and citizens’ control over and monitoring of foreign “guests”’ mobility, be it to enter or

difficult to know if these measures were effectively applied.8 exit national borders, within the host states, or on the labour market. Immigration policies strongly affected

foreign labourers’ free mobility, hence protection from the pandemic and the economic downturn.

Borders were closed and the issuing of residencies and visas to foreign labourers was halted. Domestic

transportation, together with inbound and most of the outbound international passenger air traffic were The sponsorship, or kafala system, places all foreign workers and residents under the responsibility of a

also suspended, in Gulf States and in migrants’ origin countries.9 sponsor (kafil), most often a national who is normally the employer. The sponsor bears the responsibility,

and all the costs, of completing the administrative and legal procedures pertaining to the migrant’s entry,

Close monitoring of cases and extensive testing were rolled out, especially in the UAE. Densely populat- residency, and employment. In return, the employee is tied to his/her kafil. Several categories of workers,

ed areas inhabited by foreign labourers and low-wage workers’ labour compounds, apartments and villas especially the low-skilled ones and domestics housed by the employer, have their passports confiscated

housing single Asian, as well as some Egyptian labourers,10 were particularly watched, with full lockdowns by their sponsor,22 although the practice is officially outlawed in every Gulf country today.23 Consequently,

reported in Dubai emirate, Qatar, Oman and Kuwait.1112 State-run and controlled isolation, or quarantine the kafala permits employers to hole up these foreign employees in the country, which is problematic in a

camps, as well as transit camps were also set up, to round up foreign residents in irregular administrative context of pandemic. Despite the partial lifting of the exit permit, now mandatory for all only in Saudi Ara-

situation prior to their deportation/ repatriation. Sanitary measures taken to contain the spread of the virus

13

bia but still applying to certain categories of labourers elsewhere,24 sponsors/employers continue exerting

were thus particularly targeting the foreign residents, and especially the many low-skilled labourers, among control over foreign employee’s movements, be it exit from the host state or return from abroad.

whom some of the Egyptian expatriates. Policies particularly aimed at monitoring foreigners’ mobility, as

we shall discuss now. The sponsorship system is also the cornerstone of Gulf States’ policy of discouraging foreigners’ long-term

residency and settlement. Received as workers, on a limited duration contract, migrants are expected to

Migrants’ mobility and the Covid-19 pandemic leave upon the expiration of their contract. At the very beginning of the Covid crisis, UAE private sector

employers resorted to “early leave” schemes to encourage workers’ exits back to their home countries; yet

The Covid-19 pandemic had a comparatively moderate impact on the Gulf states, with around 859,208 cu- many were imposed unpaid leaves,25 and none were guaranteed of returning to their job. Workers made

mulated cases and 7,585 deaths as of the end of September 2020, for a population of around 57 million.

14 15

redundant because of the economic crisis, or imposed salary cuts applied to foreign employees only,26 thus

had no choice but to quit the host state, sometimes after years of stay,27 while others were forcibly deport-

4 https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/news/africa/14187-egyptians-represent-40-per-cent-of-saudi-arabias-total-expatriate-

workforce.

16 Saudi Ministry of Health records: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2020-04-20-002.aspx.

5 Jordan Strategic Forum. Jordanian Expatriates in the Gulf: Who Remits, How Much, and Why? Amman: JSF, July 2018 http://jsf.

17 Figures of deaths disaggregated by nationality are not available.

org/sites/default/files/EN%20Jordanian%20Expatriates%20in%20the%20Gulf.pdf.

18 https://thenewkhalij.news/article/ 1/3 ةلامعلا-ةرجاھملا-يف-بلق-ةمزأ-ةحصلا-ةماعلا-يف-جیلخلا/ 1893.

6 https://www.knomad.org/data/remittances?tid%5B113%5D=113&tid%5B152%5D=152&tid%5B163%5D=163.

19 Yusra Alshanqityi. “Highly-Skilled Migrants in the Health Care Sector in Saudi Arabia: A Critique and Proposal”, communication

7 Alandijanya,T., Arwa A. Faizoa, and Esam I. Azhar. “Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) in the Gulf Cooperation Council

to workshop n°6 The Future of Population and Migration in the Gulf, Gulf Research Meeting 2018, Cambridge, UK, 1-3 August

(GCC) countries: Current status and management practices”, Journal of Infection and Public Health, Volume 13, Issue 6, June

2018.

2020, pp. 839-842. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187603412030486X?via%3Dihub.

20 https://apnews.com/5fc04d3552639b298e9fad342cc354eb.

8 https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2020/04/covid19-makes-gulf-countries-abuse-of-migrant-workers-impossible-

to-ignore/. 21 https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2020/04/23/migrant-workers-in-cramped-gulf-dorms-fear-infection.

9 https://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/travel/coronavirus-what-are-the-travel-restrictions-in-the-middle-east-which-borders-are- 22 https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2018/12/migration-to-from-in-middle-east-north-africa/; : Philippe Fargues,

closed-1.993741 Nasra M. Shah, Imco Brouwer, “Working and Living Conditions of Low-Income Migrant Workers in the Hospitality and Construc-

tion Sectors in the United Arab Emirates,”Research Report No. 02/2019, GLMM, https://gulfmigration.org; p. 12.

10 Gardner, A. “Labor Camps in the Gulf States”, Middle East Institute, February 2, 2010 https://www.mei.edu/publications/labor-

camps-gulf-states. 23 ILO. Employer-migrant worker relationships in the Middle East: exploring scope for internal labour market mobility and fair mi-

gration, White paper, Beirut: International Labour Organization, Regional Office for Arab States, Feb. 2017. https://www.ilo.org/

11 https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/03/qatar-migrant-workers-in-labour-camps-at-grave-risk-amid-covid19-crisis/

wcmsp5/groups/public/---arabstates/---ro-beirut/documents/publication/wcms_552697.pdf.

12 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-gulf-workers/gulfs-migrant-workers-left-stranded-and-struggling-by-coro-

24 https://www.fusion-me.com/update-on-exit-permits-in-the-gcc-qatar-oman-the-uae/.

navirus-outbreak-idUSKCN21W1O8

25 https://www.internationalinvestment.net/news/4013604/uae-launches-leave-policy-expat-workers

13 Zouache, A. COVID-19: Ruptures et continuités dans la péninsule arabique, https://cefas.cnrs.fr/spip.php?article771#nh12.

26 On Qatar: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-10/qatar-cuts-pay-for-foreign-employees-working-for-govern-

14 World Health Organisation (WHO) records, published in United Nations’ Development Programme (UNDP)-Regional Bureau for

ment.

Arab States (RBAS)’s dedicated webpage: https://www.arabstates.undp.org/content/rbas/en/home/coronavirus.html.

27 https://gulfnews.com/world/gulf/covid-19-gulf-expats-forced-to-leave-for-home-as-pandemic-impacts-jobs-1.72112920

15 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019). World Population Prospects 2019, On-

line Edition. Rev. 1 (mid-2019 data).

6 7ed.28 It is thus likely that such -directly or indirectly- forced exits contributed to spread the virus in migrants’

origin countries.29 Conversely, others, among whom Arab, skilled workers,30 found themselves stranded with middle-class families.39 Initially covered by the government,40 the cost of mandatory quarantine venues

no resources in host states, as unemployed foreigners are entitled to no governmental assistance scheme. in hotels and medical supervision proposed by Jordan’s Army-run Covid-19 Crisis Management Cell, for in-

stance, was transferred to returnees,41 which added to the financial burden of many middle-class families,

High risk of falling into irregular administrative situation in Gulf States prevented from returning to Jordan. Their residency permits having expired, these stranded nationals are

now irregular migrants in Gulf host states.42 Like the other countries, Lebanon had to prioritise between

The multiplication of expatriates’ levies, of dependents’ and other fees, like in Saudi Arabia since 2017, the various categories of stranded citizens (tourists, visitors, students, ..), with expatriates left behind until June.43

diversity and number of reforms of immigration legislations, added to the dependency on the sponsors, all Delay in repatriation flights from Kuwait to Egypt also spurred migrants’ violent discontent.44 Egyptian

increase expatriates’ risks of falling into irregularity. No less than six different categories of irregular migra- authorities promised to cover the costs of quarantines for returnees in collective accommodations (youth

tion and administrative situations may be identified in the region: (i) entering unlawfully into a country; (ii) hostels, university dorms), but isolation in hotels was left to returnees’ own expenses.45

overstaying a valid residency permit; (iii) being employed by someone who is not the sponsor; (iv) running

away from an employer, or absconding; (v) being born in the Gulf to parents with an irregular status and Origin countries’ authorities justified such delays in repatriating expats, invoking logistical difficulties and

(vi) becoming irregular due to a change in the legislation or in practices. A foreign resident may even be need to organize for quarantines. However, de facto denial of returns for citizens also pose an issue linked

unaware of his/her irregular status, if the sponsor failed to complete the necessary administrative proce- to citizenship rights: Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and article 12 of the Interna-

dures, or to renew the migrant’s permits, for instance. Ignoring specific procedures, such as the necessity for tional Covenant on Civil and Political Rights indeed recognize “the right of everyone to leave any country,

an expatriate willing to leave the UAE to have the sponsor cancel his/her residency visa, would categorise including his own, and to return to his own country”.46 More generally, Middle East migrant-sending coun-

negligent expats as absconders. Migrant workers and residents in the Gulf are thus particularly vulner- tries’ policy of encouraging citizens’ expatriation to alleviate unemployment, channel remittances to local

able to falling into irregular administrative situation, a criminal offense leading to one’s detention. This households and stimulate domestic consumption goes hand in hand with a general lack of knowledge

has aggravated migrants and their home states’ exposure to the pandemic: detained persons, such as the of expatriated citizens, especially their numbers and characteristics.47 The Covid crisis thus underlined, in

6,300 Egyptian nationals locked up prior to their deportation from Kuwait,31 were at risk of being infected; migrants’ eyes, host states’ lack of appreciation for their years-long support to their homeland.48 Yet, the

deportations by Qatar, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States were decided without concertation with origin crisis could serve as an opportunity to reconceive Mashreq countries’ emigration policies and dependency

countries and may have exported infection cases to these countries. Amnesties and the waiving of fines

32

on receiving states.

for residency violators in some countries,33 meanwhile, served the host states’ purpose of accelerating and

facilitating the deportation of unwanted, potentially infected foreign citizens. The economic crisis generated by the Covid-19 pandemic and the drop in oil prices in

Gulf States: what’s next?

The Covid-19 pandemic thus strongly impacted Gulf migrants’ mobility in many ways, from imprisonment

to forced departure, or forced stay for lack of resources to leave. However, Gulf States’ migration policies, Exact figures of Egyptian, Jordanian, and Lebanese expatriate returnees from Gulf States are not known to

all geared towards limiting expatriates’ mobility to, from and within Gulf host states and labour markets, date (November 2020). Jordan’s repatriation schemes returned about 20,000 citizens from all destinations,

aggravated the vulnerability of migrants and their host states to the pandemic. The pandemic thus exposed, of whom tourists and visitors, as well as students,49 while entry and exit figures suggest that around 50,000

more aptly than ever, migrants’ lack of agency and control of their mobility patterns in the Gulf. Jordanian citizens returned to Jordan between February and August 2020 (see figure 1). Based on previous

crises, scenarios initially forecasted the possible return of up to 1 million Egyptian workers from abroad,

Policies of migrants’ origin countries mostly from the Gulf region and Jordan, making up 3% of Egypt’s active population.50 Returns’ previsions

later increased to 1.5 to 2 million, while above 500,000 expatriates had reportedly come back to Egypt by

The crisis also unveiled migrants’ situation vis-à-vis their governments, as expatriates’ excess mortality was late August 2020, mostly from the Gulf states.51

indeed compounded by origin countries’ initial reluctance to repatriate possibly infected citizens.34 Jordan,

Egypt and Lebanon suspended passengers’ flights and closed their land, sea and air borders by mid-March.

Yet, repatriation schemes and registration platforms only started in May;35 Some Jordanian citizens denied 39 https://alghad.com/%D8%A3%D8%B1%D8%AF%D9%86%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AA%D9%82%D8%B7%D8%B9%D8%AA-

%D8%A8%D9%87%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%A8%D9%84-%D9%8A%D8%AA%D8%B-

entry in the country after the border closure remained stranded in the border area between Jordan and 9%D9%84%D9%82%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A8%D9%80-%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%84/.

Saudi Arabia for weeks.36 Repatriation schemes posed restrictions to returns to the three countries.37 Among 40 https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/five-star-coronavirus-quarantine-jordan-s-dead-sea-isolated-describe-lock-

down-1.993814.

these, plane tickets were not free, and return expenditures could amount to unaffordable sums for large

38

41 https://s.alwakeelnews.com/441698.

42 https://alghad.com/%D8%A3%D8%B1%D8%AF%D9%86%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AA%D9%82%D8%B7%D8%B9%D8%AA-

28 https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/23/middle-east-autocrats-south-asian-workers-nepal-qatar-coronavirus/. %D8%A8%D9%87%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%A8%D9%84-%D9%8A%D8%AA%D8%B-

29 https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/1217342/des-centaines-de-pakistanais-rapatries-du-moyen-orient-testes-positifs.html. 9%D9%84%D9%82%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A8%D9%80-%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%84

30 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/coronavirus-jordanians-sacked-saudi-firms-launch-campaign-return-home. 43 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/lebanese-stranded-abroad-due-coronavirus-expected-pay-exorbitant-fees-flights-home;

31 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kuwait-egypt-security/kuwait-breaks-up-egyptian-worker-riot-over-repatriation-idUSKBN- https://www.arabnews.com/node/1689581/middle-east.

22G0HU. 44 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kuwait-egypt-security/kuwait-breaks-up-egyptian-worker-riot-over-repatriation-idUSKBN-

32 https://qz.com/africa/1837457/ethiopians-expelled-from-saudi-arabia-uae-for-covid-19/; https://foreignpolicy. 22G0HU.

com/2020/04/23/middle-east-autocrats-south-asian-workers-nepal-qatar-coronavirus/. 45 http://www.emigration.gov.eg/DefaultAr/Pages/newsdetails.aspx?ArtID=764.

33 https://www.arabianbusiness.com/politics-economics/447924-uae-residency-violators-can-to-leave-uae-without-paying-penal- 46 UN Commission on Human Rights, The right of everyone to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country., 6

ty-ica; https://gulfbusiness.com/amnesty-ends-in-kuwait-30000-undocumented-expats-avail-scheme-report/. March 1989, E/CN.4/RES/1989/39, https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f0c414.html

34 https://northafricapost.com/39754-gulf-crisis-egypt-objects-return-of-citizens-stranded-in-qatar.html. 47 Françoise De Bel-Air, Mapping ENI SPCs migrants in the Euro-Mediterranean region: An inventory of statistical sources, ICMPD,

35 On Jordan: https://www.laprensalatina.com/jordan-repatriates-thousands-of-nationals-stranded-abroad/. Vienna, 2020.

36 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/coronavirus-jordanians-sacked-saudi-firms-launch-campaign-return-home. 48 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/coronavirus-jordanians-sacked-saudi-firms-launch-campaign-return-home.

37 On Jordan: https://www.arabnews.com/node/1679681/middle-east. On Lebanon : https://www.arabnews.com/node/1650796/ 49 https://www.albawaba.com/news/jordan-will-resume-repatriation-its-stranded-nationals-july-10-1366705.

middle-east. 50 https://www.independentarabia.com/node/123201.

38 https://rj.com/en/repatriation-flights-info. 51 https://www.independentarabia.com/node/143531.

8 9Challenges created by migrants’ returns 40 600

08/19

09/19

10/19

11/19

12/19

01/20

02/20

03/20

04/20

05/20

06/20

07/20

08/20

Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon are negatively affected by migrants’ returns, which decreased remittances in- 20

500

flows, and increased domestic unemployment. These are compounded by the decline in oil prices, likely to

0

NET FLOWS ( inflows-outflows) ( in 1000s)

decrease financing and investments by Gulf States, the largest investor in the Arab region.

inflows and outflows ( in 1000s)

-20 400

The three countries’ economies were already fragile before the crisis. Egypt’s unemployment rates are

expected to swell from around 8-10% before the crisis to 11%, or even 16%, depending on the economic

-40

crisis scenario faced by the country, according to governmental estimates. Around 1.2 to 2.9 million Egyptian

300

citizens could lose their jobs, 824,000 of whom being already unemployed as of June 2020.52 -60

Returned expatriates would thus add to the figures of unemployed, especially among rural, low-skilled -80 200

citizens. However, authorities promote the reintegration of Egyptians returning from abroad into Egypt’s

development process.53 The Egyptian Ministry for Immigration and Egyptians Abroad launched several ini- -100

tiatives, among which the project “Enlighten your country” in June 2020. The ministry circulated a form to be 100

filled by all returnees to set up a database of their profiles, locations, and competences, available on the -120

Ministry’s website.54 In cooperation with several other ministries and public bodies, the Ministry aims to iden-

tify job opportunities compatible with returnees’ capabilities, which would contribute to the sustainability -140 0

of development in the region of residence. Other initiatives aim to place returnees in existing projects,

55 56 Net flows Source: ministry of Tourism and Antiques

to help them starting small projects and to invest their savings, with the technical assistance of the Enter- Arrivals

prises Development Agency (MSMDEA). The Ministry also supports returnees’ attempts at returning abroad, Departures

especially Saudi Arabia.57

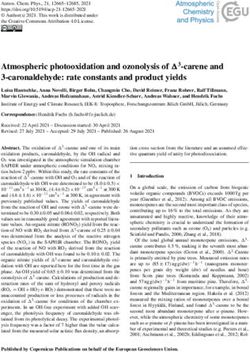

Figure 1. Monthly arrivals, departures and net flows of Jordanians to Jordan (August 2019-August 2020)

Remittances sent by Egyptians abroad to their families in Egypt stood at an estimated $27 billion for 2019,

or 8.9% of the country’s GDP, according to the World Bank.58 Based on 2020 first quarter’s figures, expatriates’ The deficit is likely to deepen if flows of return migration reach the anticipated 100,000 returns (20% of an

remittances were expected to contract by 10 to 15% for 2020. However, remittances increased by the end

59

estimated 500,000 Jordanians workers abroad).64 So far, movements recorded at the country’s borders65 from

of 2020. Total transfers amounted to about $7.9 billion in the third quarter of the fiscal year 2019/20, com- February to July 2020 indicated a net return migration of 50,000 citizens (Figure). Figures for August (last

pared to $6.2 billion, year-on-year, with an increase of about $1.7 billion. Reasons for such a move may be

60

available data as of November 2020) were slightly negative, possibly suggesting the start of new departures.

“temporary factors” such as migrant workers transferring their savings in preparation to return home, the Meanwhile, Jordanian authorities plan to integrate expatriates’ expertise in the local economy. In May 2020,

impact of lockdown restrictions on transferring funds and a shift to formal remittance channels, which are the Jordanian Chamber of Commerce launched on online platform to link employers to job seekers.66 The

picked up in the official data.61 Investment Promotion Authority oversees opening investment opportunities to returnees. However, accord-

ing to returnees’ accounts published in the press, Jordan’s finances may not benefit from much of returnees‘

In Jordan, unemployment rates are very high, at 19% of the Jordanian labour force according to official savings. Salary cuts, unpaid leaves, and lay-offs, as well as travel and quarantine costs, were said to have

statistics. Since the onset of the crisis, 150,000 Jordanian private sector employees had lost their job in

62

dried out many expats’ assets. Many mentioned difficulties to even retrieve their end-of-service benefits.67

the Kingdom as of early July,63 and Jordan’s economy is expected to contract by 3.5% in the coming year, as

compared to the 2% growth of 2019. Remittances’ inflows to the country reached $4,510 million in 2019, or As for Lebanon, the country’s financial crisis that erupted since October 2019’s popular demonstrations, add-

10.2% of the country’s GDP according to the World Bank. Remittances from expatriates make up the larg- ed to the economic downturn due to the pandemic, can only be exacerbated by the return of expatriates

est financial inflow to the country’s economy, surpassing at times FDIs and development aid inflows. Yet, and the drop in remittances. These made up 12.7% of the country’s GDP and amounted to 7,467 million for

Central Bank’s figures for the first quarter of 2020 indicated a 6% decrease in remittances’ inflows, when 2019 (World Bank figures). From 43% in 2017, the share of remittances coming from the Gulf to Lebanon had

compared to the same period in 2019. been decreasing.68 This global remittances figure is likely to be underestimated, as expatriates increasingly

used money transfer services like Western Union, or even physical transfer, due to their lack of trust in

52 https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/06/egypt-working-gulf-return-economy-coronavirus.html. Lebanese banks. These inputs to families were interrupted for months, during the lockdown and the halt of

53 https://egyptianstreets.com/2020/05/09/we-seek-to-integrate-egyptians-returning-from-abroad-into-egypts-economy-minister/. international flights. Unemployment figures are not available for the country, but it is unlikely that the cur-

54 http://www.emigration.gov.eg/DefaultAr/Pages/newsdetails.aspx?ArtID=789. See also the publication of the Ministry Masr

Ma’ak, n°18, p. 1. rent economic climate will conduce returnees to stay in Lebanon and invest their savings. The deterioration

55 http://www.emigration.gov.eg/DefaultAr/Pages/newsdetails.aspx?ArtID=787. of the socio-political climate and deepening recession indeed compelled increasing numbers of despaired

56 http://www.emigration.gov.eg/DefaultAr/Pages/newsdetails.aspx?ArtID=848; http://www.emigration.gov.eg/DefaultAr/Pages/

newsdetails.aspx?ArtID=833.

citizens to emigrate from Lebanon,69 a trend reinforced by the August 2020 blast in Beirut.

57 http://www.emigration.gov.eg/DefaultAr/Pages/newsdetails.aspx?ArtID=828.

58 https://www.knomad.org/

59 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/coronavirus-egypt-lebanon-jordan-remittance-economy. 64 https://www.zawya.com/mena/en/economy/story/JCC_online_jobs_platform_to_help_returning_Jordanians-SNG_174786261/.

60 https://see.news/remittances-from-egyptians-abroad-record-7-9-billion/. 65 Records of arrivals and departures. These figures may be underestimated.

61 This was witnessed in some Asian countries (https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/apac-remittances-to-de- 66 https://www.zawya.com/mena/en/economy/story/JCC_online_jobs_platform_to_help_returning_Jordanians-SNG_174786261/.

cline-amid-coronavirus-shock-08-09-2020). 67 https://alghad.com/%D8%A3%D8%B1%D8%AF%D9%86%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AA%D9%82%D8%B7%D8%B9%D8%AA-

62 http://dosweb.dos.gov.jo/. %D8%A8%D9%87%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%A8%D9%84-%D9%8A%D8%AA%D8%B-

63 https://www.aljazeera.net/ebusiness/2020/7/11/%D8%AA%D8%AE%D9%88%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%85%D9%86- 9%D9%84%D9%82%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A8%D9%80-%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%84/.

%D9%87%D8%AC%D8%B1%D8%A9-%D8%B9%D9%83%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%B9%- 68 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/coronavirus-egypt-lebanon-jordan-remittance-economy.

D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B1%D8%AF%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A9 69 https://english.alaraby.co.uk/english/indepth/2020/7/21/a-new-wave-of-emigration-looms-over-lebanon.

10 11Prospects for future migration to the GCC all exit permit requirements and allows workers to change jobs before the end of their contract without

No Objection Certificate from their employer. Saudi Arabia’s Labour Market Initiative, set to enter into force

The current crisis, likely to deepen in the coming years, also puts a question mark on future employment in March 2021, claims to have cancelled the sponsorship system in the Kingdom. The measure introduces a

opportunities in the oil monarchies for Arab labourers. contractual relationship between the employer and the employee. Workers can apply directly for posts in

Saudi Arabia via an e-government portal. Workers’ residency will cease being tied to a specific employer or

Economic downturn in Gulf states employment status, while the work contract must be certified by the government. Exit, re-entry and final

exit should also be free and not conditional on employer’s consent. These measures intending to improve

Across the six Gulf Cooperation Council member states, some experts forecast that employment “could fall job mobility, flexibility, and competition, allegedly aim to boost the productivity of the private sector, in line

by around 13%, with peak-to-trough job losses of some 900,000 in the UAE and 1.7m in Saudi Arabia”.70 In with international labour regulations.81

Dubai alone, 70% of business owners expect their companies to close before the end of 2020.71

Despite such moves, essential elements of the kafala system remain everywhere in the Gulf, such as the

As Gulf states condition foreigners’ residence to employment, the return from Gulf countries of expatriates mandatory sponsorship of the employer to eventually obtain a visa. The terms of the labour contracts may

made redundant could exceed 3.5 million people. The numbers of residents could decline by between 4% include abusive clauses, such as the obligation to inform the employer in advance to leave the Saudi Arabia.

(in Saudi Arabia and Oman) and around 10% (in the UAE and Qatar). By mid-July 2020, Kuwait claimed that

72

In Qatar, workers are actually still required to give the employer a 72 hours’ advance notice before depart-

over 158,000 expat workers had already left the country since March, among whom a majority of Indians ing from the country. Moreover, the Saudi labour reform excludes those employed in the domestic sector

and Egyptians, and a total of 1.5 million expats are expected to leave by the end of year. Meanwhile, 73

(drivers, guards, domestic workers, shepherds and gardeners), who are particularly subject to exploitation.82

250,000 foreign labourers had lost their jobs already by April. In Saudi Arabia, Jadwa Investment estimated

74

These factors put a question mark on Gulf labour markets’ attractivity in the future.

that around 323,000 workers had left the Kingdom during the first semester of the year, with 178,000 suc-

cessful applications for Awdah, the government scheme to facilitate the departure of expat workers to their On a shorter term, new health guarantees now requested from foreign immigrants pose additional con-

countries of origin during the covid-19 pandemic, processed between April 22 and June 3. . A total of around

75

straints to returning to the Gulf. New migrants and valid visa holders are required to produce recent certif-

1.2 million expats is expected to leave the Saudi labour market, mostly from the accommodation and food icates of non-contamination for COVID-19 using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test. Other guarantees

services, administrative and support activities (which includes rental and leasing activities, travel agencies, are also requested, such as mandatory self-isolation for 7 to 14 days upon arrival, or a proof of health insur-

security and building services).76 However, the suspension or delay in mega-projects or world-class events ance (in Oman). These measures could make migrants’ health status a new criteria for migrants’ selection

such as Dubai Expo 2020 is also likely to affect other sectors, such as construction and logistics, which may and entry.

hit the many engineers, architects and other skilled and highly-skilled technicians from the three countries.

The aviation industry, another major employer of expatriates, is expected to lay off as many as 800,000 However, long-term changes in Gulf States’ hiring policies may have a decisive impact on future migration

employees from the six Gulf States’ national companies.77 trends from the Arab region. Using the crisis as an opportunity, GCC governments indeed currently hasten

pre-crisis policies of migrants’ replacement by nationals, to curb citizens’ unemployment and address the

Migration policies, new and old “demographic imbalance” between nationals and expatriates. For example, the Nitaqat programme ongoing

in Saudi Arabia since 2011, bars an increasing number of employment sectors to foreign employees, to the

Some migration specialists showed confidence that migration will resume with the receding of the crisis benefit of nationals. A steep hike in expatriates’ levies and dependents’ and other fees since 2017 made for-

and oil prices’ correction. Massive return migration back to home states is feared but did not happen yet; eigners more expensive to employ; as a result, Jadwa Investment estimated that about 2 million expatriates

figures of job losses are also larger than figures of departures, so far. Some, especially low-skilled expats left Saudi Arabia since 2017.83 Job nationalisation, especially in the public sector,84 has accelerated every-

could also stay in the Gulf irregularly. 78

where. In Qatar and the UAE, the two wealthiest and less populated Gulf States, nationals enjoyed qua-

si-full employment, while foreigners made up the bulk of the labourers, including in the governmental

Gulf states also seek to become more attractive for skilled foreign labourers. Reforms of the kafala sys-

79

sector (45% in Qatar in 2018, for instance).85 Yet, since the advent of the Covid crisis, even the two countries

tem were decided to that effect. Bahrain had led the way for reforming the sponsorship system in 2009, by now advocate for cuts in foreign staff in government entities.86 Hiring agencies in sending states such as

transferring the monitoring of migrants’ flows from sponsors to a new public body, the Labour Market Regu- Egypt experienced the dwindling of opportunities for their nationals in the Gulf since 2017,87 especially for

lation Authority. Reforms of the system were conducted in almost every country in the region over the past low-skilled labourers. Ongoing ambitious reforms and masterplans aiming to make Gulf states “knowledge

decade, such as the lifting of sponsor’s mandatory No Objection Certificate (NOC) on entrance into and exit, societies“, less dependent on oil revenues, indeed prioritise the hiring of highly skilled expatriates.88 At the

and change of job, passed in Bahrain and the UAE.80 Recently, Qatar issued Law No. 19 of 2020, that removes same time, specific opportunities and posts are carved in for Gulf nationals, even at the expense of some

skilled foreign employees, among whom Arabs.89 Figure 2 confirms that labour permits issued to Egyptian

70 https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/my-oxford/publications/561739. labourers to work in the Gulf states have been steadily decreasing since 2015, especially for Egyptians’ main

71 https://english.alarabiya.net/en/coronavirus/2020/05/22/Around-70-of-Dubai-companies-expect-closure-within-6-months-

amid-coronavirus-Survey

72 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-22/oxford-economics-sees-exodus-of-expat-workers-from-across-gcc. 81 https://www.arabnews.com/node/1758456/saudi-arabia.

73 https://www.arabnews.com/node/1703066/middle-east 82 https://www.dw.com/ar/a-55524124

74 https://www.kuwaitup2date.com/over-250000-expats-lost-their-jobs-in-kuwait/ 83 https://www.internationalinvestment.net/news/4005152/-million-expats-quit-saudi-arabia-citing-fees-sluggish-growth.

75 https://www.internationalinvestment.net/news/4016744/million-expats-forecast-leave-saudi-arabia 84 https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/05/oman-contracts-spending-coronavirus-economy-oil-royal-court.html;

https://www.arabnews.com/node/1666981/middle-east.

76 Jadwa Investment. Saudi Labour Market, June 2020 https://www.sustg.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Saudi-labor-mar-

ket-June-2020.pdf. 85 https://gulfmigration.org/qatar-economically-active-population-aged-15-and-above-by-nationality-qatari-non-qatari-sex-and-ac-

tivity-sector-2018/

77 https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2020-04-23-01/.

86 https://www.arabnews.com/node/1688281/middle-east.

78 CMRS Webinar: Covid-19 and International Labor Migration in the Middle East, 24 June 2020 https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=BD7Uh5S8C1w. 87 https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/03/job-nationalization-gulf-countries-affect-work-egyptians.html.

79 https://www.wsj.com/articles/pandemic-prompts-gulf-countries-to-adopt-more-western-norms-11605103200. 88 https://vision2030.gov.sa/en; https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/qnv1/Documents/QNV2030_English_v2.pdf.

80 Zahra, M. “The Legal Framework of the Sponsorship Systems of the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: A Comparative Exam- 89 https://www.gulf-insider.com/kuwait-nearly-2000-expat-teachers-to-be-sacked/.

ination,” Explanatory Note No. 4/2019, Gulf Labour Market and Migration (GLMM) programme of the Migration Policy Center

(MPC) and the Gulf Research Center (GRC), http:// gulfmigration.org.

12 13destination, Saudi Arabia. As stated by the Egyptian Chamber of Commerce, 55,000 work permits were

Conclusion

issued per month to Egyptians for the 6 GCC countries on the eve of the Covid-19 crisis.90 These figures

mark a drop of 33% in the number of permits issued, as compared to 2017.

1,400 1,400

The Covid-19 thus had, and may still have in the future, a major impact on Egyptian, Jordanian and Leba-

Number of work permits issued for

1,200 1,200 nese expatriates’ mobility from and back to Gulf countries. However, the paper showed that the effect of

the pandemic on expatriates’ mobility was also compounded by Gulf host states’ legal systems and immi-

1,000 1,000

gration policies, among which the sponsorship system. Moreover, the pandemic served as an opportunity

abroad (1000s)

800 800 to accelerate pre-Covid crisis reforms of Gulf migration policies. Gulf host states started streamlining job

nationalisation policies and limiting the hiring of low-skilled labourers before 2020. This may particularly

600 600

affect the large pools of Egyptian labourers, some of whom not skilled and trained according to Gulf States’

400 400 changing hiring needs and political priorities, as well as specific professions occupied by Jordanians and

Lebanese. Changes in the trends and patterns of migration to the Gulf states, especially when it concerns

200 200 the millions of Egyptian migrants to the region, may have consequences on other immigration hubs, among

which the EU.

0 0

2010 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Egyptian authorities’ reaction to the possible return of large numbers of nationals from abroad may be in

tune with such changes, and signal attempts at streamlining Egypt’s emigration policies. The government

Saudi Arabia Kuwait Jordan Source: CAMPAS, Annual bulletin for

Work Permits for Egyptians Working claims it will diversify emigration destinations for nationals, turning for instance to the African Union’s mem-

Abroad

UAE Qatar Oman ber states.96 Economist Abdel Fattah indeed argued in an online seminar that “there are also opportunities

Libya Others Total

for Egypt to look to alternative and emerging new demands for labour, such as agriculture or care work, in

European countries where the need has increased during the pandemic”. Experts also considered positively

Manpower and Immigration Ministry’s initiative to record Egyptian returnees’ skills and competences, to

Figure 2. Work permits issued to Egyptians working abroad (main emigration countries, 2011-2018) either integrate them back into the Egyptian economy, or to prepare them for the reopening of Gulf labour

markets. Abdel Fattah called for designing skills-matching initiatives and addressing the largely young and

The demographic dominance of expatriates in resident population also spurred violent anti-expatriates’ educated unemployed population by prioritizing migration policy which seeks to fill labour demand gaps

statements. In Kuwait, these particularly targeted Egyptians, the second largest foreign community in

91 92

in international markets.97

the country. Some Kuwaiti lawmakers proposed a draft bill suggesting a quota system as one way to re-

dress the demographic imbalance in the country. According to the proposed quota system, non-nationals Based on these results, the paper proposes three sets of recommendations.

should make up a maximum of 30% of the total population. The numbers of Indian workers should not

exceed 15% of the overall Kuwaiti population while those of Egyptian expatriates should stand at a max- 1. Migrant-sending countries should question the sustainability of mass migration to author-

imum 10%.93 If implemented, the quota system would mean that Egyptians would only number 140,000 itarian countries. Therefore, alleviating dependency on single destination states or regions

in Kuwait, down from at least 670,000 before the Covid-19 crisis. Eventually, Kuwait’s National Assembly 94

through diversifying host states may be a good start, like is currently advocated for in Egypt.

approved only parts of the law, and voted measures to decrease the share of expatriates from 70% to Tunisia is another example: the country works to expand placement opportunities outside

30% of the resident population. 95

the traditional European destinations, especially France, and started looking to countries

such as Canada.

2. Better negotiating bilateral migration agreements to guarantee migrants’ protection, as well

as empower representatives of home states in destination countries (embassies and con-

sulates, for instance), is therefore essential. Learning from the experience of other, non-Arab

states (for example, the Philippines), which achieved a better degree of institutionalisation

of migration policies and monitoring of migration flows would be useful.

3. Consequently, it is of utmost importance for sending states to set up tools for better know-

ing the numbers, location, movements and characteristics of expatriates, in order to devise

sustainable migration policies and anticipate future crises.

90 https://www.youm7.com/story/2020/11/6/5053564.

91 https://www.courrierinternational.com/revue-de-presse/pandemie-koweit-les-immigres-na-qua-les-jeter-dans-le-desert.

92 https://www.albawaba.com/node/egyptians-out-kuwaiti-trending-hashtag-maybe-6-years-old-1358185.

93 https://arabic.cnn.com/business/article/2020/05/28/kuwait-a-draft-law-change-demographics-weight-nationalities.

94 https://gulfmigration.org/kuwait-non-kuwaiti-population-by-region-and-selected-countries-of-origin-2018/. 96 https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/03/job-nationalization-gulf-countries-affect-work-egyptians.html.

95 https://www.timeskuwait.com/news/national-assembly-approves-demographic-law-to-cut-expat-numbers/. 97 Dina Abdel Fattah, in CMRS Webinar: Covid-19 and International Labor Migration in the Middle East, 24 June 2020, ‘’30 mn.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BD7Uh5S8C1w.

14 15Contact:

EMM4_team@icmpd.org

Address:

ICMPD Regional Coordination Office for the Mediterranean :

Development house, 4A / St Anne Street / Floriana, FRN 9010 / Malta tel:+356 277 92 610

www.icmpd.org/emm4 emm4_team@icmpd.org

@EMM4_migrationYou can also read