THE EFFECTS OF REPEATED READINGS AND ATTENTIONAL CUES ON READING FLUENCY AND COMPREHENSION

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Journal of Reading Behavior

1985, Volume XVII, No. 2

THE EFFECTS OF REPEATED READINGS AND ATTENTIONAL

CUES ON READING FLUENCY AND COMPREHENSION

Lawrence J. O'Shea

University of Florida,

Department of Special Education,

Gainesville, FL 32611

Paul T. Sindelar and Dorothy J. O'Shea

The Pennsylvania State University,

Division of Special Education and Communication Disorders,

University Park, PA 16802

Abstract

The failure of some researchers to find improved reading comprehension with

increased fluency may result from the assumption that readers automatically

shift attention to comprehension when fluency is established. Research on

cuing readers to a purpose in reading suggests that a simple cue about com-

prehension may be sufficient to prompt this attentional shift. In this study, the

effects of repeated readings and attentional cues on measures of reading flu-

ency and comprehension were examined. Thirty third graders read separate

passages one, three, and seven times following cues to attend to either reading

rate or meaning. After the final reading of each passage, the students retold as

much of the story as they could. Fluency and proportion of story propositions

retold were analyzed in repeated measures analyses of variance. Significant

main effects for both repeated readings and attentional cues were obtained on

both dependent measures. Thus, both fluency and comprehension increased as

the number of repeated readings increased. In addition, readers cued to flu-

ency read faster but comprehended less than those cued to comprehension.

These results suggest that increasing fluency is a less efficient means of im-

proving comprehension than presenting cues about comprehension.

129

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015130 Journal of Reading Behavior

Research has shown that rapid word recognition is correlated with good

comprehension (Perfetti & Hogaboam, 1975). There has been debate,

however, over the efficacy of training students to recognize words in isolation

rapidly (Blanchard & McNinch, 1980; Fleisher, Jenkins, & Pany, 1979; Spring,

Blunden, & Gatheral, 1981). Two concerns are raised regarding the effect of

training students to recognize words in isolation on comprehension of con-

nected discourse. First, there is more to reading passages than simply recog-

nizing and understanding individual words. Readers need to chunk words into

larger, meaningful units in order to facilitate better comprehension (Cromer,

1970; Smith, 1978). Second, procedures to train students to recognize words in

isolation often have embedded cues that effectively focus students' attention to

read individual words quickly and accurately. This focus on fluency may in-

terfere with reading for comprehension (Fleisher et al., 1979; Spring et al.,

1981). Consequently, the effects of improved recognition of words in isolation

have not been shown conclusively to improve comprehension.

A more direct means of training students to increase their reading flu-

ency with concomitant effects on reading comprehension is through contextual

practice, such as repeated readings. Repeated practice has been shown to

facilitate faster reading speeds, greater accuracy, and increased compre-

hension (Carver & Hoffman, 1981; Chomsky, 1976; Dahl, 1979; Gonzales &

Elijah, 1975; Samuels, 1979). As with high speed isolated word recognition,

the rationale for the repeated reading procedure is that automatic decoding

(LaBerge & Samuels, 1974), facilitated through practice, frees attention to

focus on comprehension. Unlike words practiced in isolation, however,

repeated reading allows students to become familiar with syntactic and se-

mantic structures.

Another consideration underlying the effects of high speed word recog-

nition on reading comprehension is whether readers automatically shift their

attention to comprehension once decoding fluency has been established. Ac-

cording to the research which has investigated the effects of automatic

decoding, little support exists to substantiate the premise that readers

automatically attend to comprehension. Studies on training words in isolation

have shown definite increases in word recognition rates, but concomitant

effects on comprehension have not been reported (Fleisher et al., 1979; Spring

et al., 1981). This suggests that students may need to be cued to shift their

attention from word recognition to comprehension once fluent reading has

been achieved.

The ability to shift attention from fluent word recognition to compre-

hension seems to be a function of the difficulty level of passages relative to in-

dividual readers and the explicitness of cues to the purpose for reading. Studies

(Britton, Ziegler, & Westbrook, 1980; DiStefano, Noe, & Valencia, 1981;

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015A ttentional Cues \ 31

Pehrsson, 1974) have shown that reading rates and comprehension of skilled

readers vary with passage difficulty and cues to purpose (i.e., to overview

material, to get details, or to retrieve specific information). When passages are

easier to read, reading rates are faster and comprehension greater. In addition,

fluency and comprehension performances change when cues to purpose for

reading are used.

Regardless of whether cues are provided intentionally, or inadvertently,

readers appear to perceive the purpose for reading based on the external

demands of the reading situation and perform accordingly. This effect is ap-

parent in the studies reported by Fleisher et al. (1979) and Spring et al. (1981)

in which unintentional cues to read quickly and accurately may have altered

performance and from studies in which cues to change reading performance

were intentionally manipulated (DiStefano et al., 1981; Frase & Kreitzberg,

1975; Grant & Hall, 1967; Pehrsson, 1974). Thus, students do not appear to

shift their attention to comprehension automatically when reading fluently. In-

stead, they react to cues reflecting the purpose for reading. In addition, the ef-

fects of comprehension cues increase inversely with the relative difficulty of

passages. The easier the passage, the greater is the gain in comprehension that

results from the presentation of comprehension cues.

Therefore, in conjunction with repeated reading, cues could be used to

direct students' attention to different purposes for reading: reading for fluency

or comprehension. If students were provided repeated readings and cued to

comprehension, they should be able to increase fluency as well as compre-

hension. Students cued to read for fluency should show greater increases in

speed and accuracy, but improvement on comprehension measures should be

less. In addition, varying the number of repeated readings could provide the

opportunity to determine a point of diminishing returns, beyond which con-

tinued contextual practice results in no further gain. For instance, students

may dramatically increase their fluency between the first and second readings,

with increases diminishing between subsequent readings, until finally no in-

creases or decreases in reading rate occur. Such information is essential in

determining an optimal number of repeated readings.

To test the plausibility of these assumptions, the present experiment was

conducted. Two groups of students repeatedly read passages under different

cue conditions. One groups was cued to read for comprehension, the other to

read quickly and accurately. If, as LaBerge and Samuels (1974) contend,

shifting of attention between decoding and comprehension is a function of flu-

ency, and if, as DiStefano et al. (1981) have demonstrated, the effect of cues

varies with passage difficulty and type of cue, then, as the number of repeated

readings increases, the effects of each cue condition should increase.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015132 Journal of Reading Behavior

Method

Subjects

Thirty third-grade students from a rural community in central Penn-

sylvania who (a) functioned at or above grade level in total reading perfor-

mance as measured by the California Achievement Test (CAT) (Tiegs &

Clarke, 1970) and (b) read from 70-119 words per minute on two fourth-grade

screening passages participated as subjects. Grade equivalent scores from the

CAT were acquired from student records. Students were screened on the

reading rate measure during a 20-minute session the week before the experi-

ment began. A fluency criterion based upon Starlin and Starlin's (1973) range

of 70-119 words per minute for the instructional reading level was used to

qualify students for participation in the study. Of the 53 students who returned

signed release forms, 30 students met the qualifying criterion and were selected

to participate in the study.

Setting

The students attended regular third-grade classes in two elementary

schools, one traditional and one with an open design. The screening and ex-

perimental treatment procedures were conducted with individual students in

isolated rooms away from distractions.

Materials

Five equivalent reading passages were needed for the study, two for

screening and three for the experimental treatments. A three-tier process was

used to validate the equivalency of the passages. First, the Fry Readability

Graph (Fry, 1968) was used to estimate the grade level of passages selected

from the Specific Skills Reading Series, Getting the Facts, Books C and D

(Boning, 1963). Five 200-word passages at the fourth-grade level were selected

for further analysis. Next, the five passages were examined to determine that

they contained an approximately equivalent number of propositions (Kintsch,

1974); they ranged from 67 to 74. Finally, the passages were administered to 80

third graders from a neighboring school district and scored for reading rate

and comprehension. There were no significant differences among passages on

either reading rate, F{4, 150) = .74, p > .10, or comprehension, F(4, 70) =

1.70, p > .10.

Procedures

Assignment to experimental conditions. Students were randomly assigned

to one of two experimental conditions; a cue to read quickly and accurately or

a cue to read for comprehension. Under both conditions, students were

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015A ttentional Cues 133

exposed to all three levels of the repeated readings condition: one, three, and

seven readings.

A post hoc analysis of the composition of each of the two groups was con-

ducted using the screening scores and the CAT reading achievement scores. No

significant differences were found between groups on reading rate (t2% - .29,

p > .50), or on either the vocabulary (/2s = 1.00,/? > .10), the comprehension

(Í28 = 1.44, p > .10), or total reading score (/28 = 1.01, p > .10) of the CAT.

To control for order effects due to presentation of the three experimental

passages and the three levels of the repeated reading variable, a counter-

balancing procedure was implemented. All students were randomly assigned

one of three orders of presentation for the passages (A, B, C; B, C, A; and C,

A, B) and one of three orders (1, 3, 7; 3, 7, 1; and 7, 1,3) for the levels of the

repeated reading variable. Therefore, roughly equal numbers of students

under each of the cue conditions were assigned one of the nine ordering

combinations.

Independent Variables

The two experimental manipulations investigated in this study were atten-

tional focus and number of repeated readings.

A ttentional focus. The two levels of the attentional focus variable were

cue for fluency and cue for comprehension. The children in the cue for fluency

condition were told: "I want you to read this story out loud as quickly and cor-

rectly as you can. I am going to time you with this stopwatch. If you read

quickly and accurately you will get a sticker." Before each subsequent reading

a shortened version of this cue was presented to students: "Remember, read as

quickly and correctly as you can." A stopwatch was placed in the middle of the

table in full view of the student to enhance the strength of the verbal cue.

The verbal cue used for students assigned to the cue for comprehension

condition was: "I want you to read this story out loud. I want you to try to

remember as much about the story as you can. The important thing is to find

out as much about the story as you can. When you are done, I am going to ask

you to retell the story to me. If you remember a lot, you will get a sticker."

Before each subsequent reading, a shortened version of this cue was presented:

"Try to remember as much about the story as you can."

Repeated readings. Students under both attentional focus conditions

received all three levels of the repeated reading variable: one, three, and seven

readings. Passage content or topic was not previewed or reviewed with

students. Each level of the repeated reading variable was administered on a

different day. The time lapse between administrations ranged from one to

three school days, with a total time lapse of approximately two weeks required

to expose all students to the three levels.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015134 Journal of Reading Behavior

Dependent Variables

Reading rate and comprehension data were collected for each of the

passages read.

Reading rate. Reading rate was defined as the number of words read cor-

rectly divided by the total reading time. Reading rate measures were taken on

each reading of each passage within each level of the repeated reading variable.

Only the final measure at each level was used in the data analysis.

Comprehension. A story retell procedure was used to measure students'

comprehension of each passage. After each story was read the designated

number of times, students were asked to retell as much as they could about the

story. Kintsch's (1974) proposition analysis system was used to analyze and

score the story retellings.

Experimental Procedures

Fluency condition. Subjects were taken to one of the treatment rooms and

seated at a desk across from the experimenter who then presented the initial

fluency cue to the students and asked if they understood the task. At the same

time, a stopwatch was shown to the students to ensure that they knew they

were being timed. The investigators instructed students to look at their copy of

the passage and to begin reading orally. They used one hand to operate the

stopwatch and the other to depress a pause switch on the tape recorder to give

the appearance that the oral reading was being recorded.

When students finished reading a passage, they were told to read the

passage again (when necessary) and were given the shortened verbal cue.

Students were told neither how many times they were to read each passage nor

which was the final reading.

Immediately after students finished the last reading, they were praised for

reading quickly and accurately and given a sticker. Next, the investigators

depressed the record button on the tape recorder and said to the student "let

me turn this off." The investigators then asked students to tell what they could

remember about the passage. The deceptive use of the tape recorder minimized

its potential effect to cue students to the comprehension task. When students

were finished retelling the story, they were sent back to their classrooms.

Comprehension condition. The investigators presented the initial com-

prehension cue and confirmed students' understanding of the task. Under this

condition, no stopwatches were used to time the readings. Instead, the in-

vestigators used wristwatches shielded from the students' sight by clipboards.

When students finished reading a passage, they were told to read the

passage again (when necessary) and were provided the shortened verbal cue.

After the last reading of each passage, the investigators told students that the

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015A ttentional Cues 135

tape recorder in the middle of the table would be used to record them retelling

the story. Next, the investigators asked students to retell the story and then

depressed the record button on the tape recorder. W h e n students finished

retelling the story, the investigators shut off the recorder, praised students for

remembering a lot about the story, and presented them with a sticker.

Scoring. During each reading, the investigators timed the reading and

scored any oral reading errors (mispronunciations, substitutions, and omis-

sions) on their copy of the passage. Numbers were placed above each erred

word to indicate on which reading the error was committed. The number of

words read correctly and the number of errors on each reading were then

counted. These counts were converted to rates by dividing each by the number

of seconds of reading and multiplying by 60. N o corrective feedback was

provided on the oral reading errors at any time.

A s the students retold segments of the stories during the story retelling

process, the investigators would nondifferentially nod their heads and say

" O K . " When students hesitated, the investigators asked students if they could

remember anything else and told them to think hard. These procedures were

continued until students could n o longer respond.

The story retellings were recorded on audio cassette tapes for later

analysis. The taped dialogue of each student's story retelling of all passages

was transcribed by the investigators. Only the student's subject number and

passage number were used for identification. Thus, the investigators were

unaware of the corresponding levels of either the attentional focus or repeated

reading variables when scoring individual retellings.

After the story retellings had been transcribed, the retellings and passages

were transformed into propositions using Kintsch's (1974) propositional

analysis procedure. The propositions from the story retellings were scored as

correct if they matched the passage proposition exactly or if the story retelling

proposition contained at least part of the passage proposition while omitting

or substituting a semantically similar term for the remainder (e.g., responding

"a big clam" rather than "a large clam"). The proportion of matching propo-

sitions ( P O P ) retold by students was used as the numeric measure for

comprehension.

Interrater Agreement

T o ensure reliable evaluations of the story retelling measure, two pro-

cedures were conducted. First, the stories were transformed into propositions

by two independent judges familiar with the Kintsch procedures for proposi-

tional analysis. Their analyses were compared proposition by proposition, and

their percentage of agreement was computed using the following formula:

Agreements/Agreements + Disagreement x 100 = °?o Agreement

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015136 Journal of Reading Behavior

The two judges agreed upon 92% of the propositions; in the case of

disagreements, differences were resolved through discussion.

Second, the story retellings for all students on all passages were scored as

described by two independent judges. Their records were compared and their

percentages of agreement were computed using the same formula. Interjudge

agreement averaged 94% and was deemed acceptable for the purposes of this

study.

Because the experimental procedures were carefully scripted for both in-

vestigators, a procedural reliability coefficient was hot calculated. Each in-

vestigator had a copy of the step-by-step protocol, including verbal cuing

systems, placement and use of materials, and the delivery of noncontingent

rewards for student participation.

Design and Analysis

The experimental design used was a 2 (attentional focus condition) x 3

(number of repeated readings) mixed design with one between and one within

factor (Meyers, 1979). Subjects were nested within levels of the attentional

focus variable and received all levels of the repeated reading variable. A

multivariate analysis of variance and follow-up univariate analyses of variance

were computed to determine significant differences among the levels of the ex-

perimental treatments. A Bonferroni adjustment on the level of alpha (Bray &

Maxwell, 1982) controlled for experiment-wise error in the univariate analyses,

In addition, Tukey's Wholly Significant Difference (WSD) Test was computed

to evaluate the significant differences between marginal means.

Results

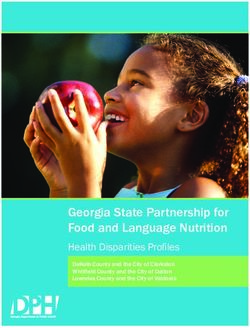

Table 1 contains the means and standard deviations of the data from the

two dependent measures by group and number of repeated readings. To test

the hypothesized effects of the independent variables on both of the dependent

measures simultaneously, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was

used. This analysis yielded a significant main effect for both attentional focus,

F\2, 27) = 16.56, p < .001, and repeated readings, F{4, 25) = 27.27, p <

,001, though no attentional focu,s by repeated reading interaction effect was

found. These results indicate that both independent variables had significant

differential effects within their respective levels. The MANOVA, however,

does not specify the nature of these effects with respect to each of the de-

pendent measures; that is, the MANOVA alone does not delineate how the

groups differed on the separate dependent measures.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015A tteniional Cues 137

Table 1

Means and Standard Deviations for Each Dependent Measure by Experimental

Condition

Number of readings

Attentional 1 3 7

focus cue D.V. M SD M SD M SD

Reading rate WPM* 117.00 (29.67) 141.70 (30.38) 155.30 (25.68)

POP** .15 (.09) .22 (.12) .26 (.12)

Comprehension WPM 101,00 (13.51) 123.60 (13.60) 133.90 (14.40)

POP .25 (•H) .32 (.11) .37 (.11)

*Words per miriute. ''Proportion of propositions recalled.

Therefore, univariate analyses of variance were conducted on both de-

pendent measures using the Bonferfoni approach (Bray & Maxwell, 1982; Har-

ris, 1975) arid dividing alpha by the number of analyses being performed to

control the experiment-wise Type I error.

A significant main effect for the attentional focus variable was found on

both reading rate, f\\, 28) = 6.62, p = .02, and comprehension, F{\, 28) =

12.67, p = .001. Students who were cued to read quickly and accurately ex-

hibited a higher mean number of words read correctly per minute, but a lower

mean proportion of propositions retold than students cued to read for com-

prehension. Students, therefore, responded to the cuing systems as predicted.

In addition, significant main effects for repeated readings were obtained

on reading rate, F{2, 56) = 69.05, p < .001, and on comprehension, F{2, 56)

= 11.93, p < .001. No interaction was found between repeated readings and

attentional focus on either measure. An analysis of the marginal means for

one, three, and seven readings using Tukey's WSD procedure indicated that all

reading rate means were significantly different from each other. On the com-

prehension measure, however, the mean score for one reading was signifi-

cantly less than the mean scores for both three and seven readings, which did

not differ significantly.

Thus, students under both attentional focus conditions read at pro-

gressively higher reading rates as the number of repeated readings increased

from one to three to seven. At the same time, students demonstrated increased

comprehension scores as the level of the repeated reading variable increased

from one to three readings. However, the improvement in the comprehension

scores between three and seven readings was not significant. These results

were shown regardless of whether students were cued to read quickly and

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015138 Journal of Reading Behavior

accurately or cued to read for comprehension. Based upon the main effect for

attentional focus, however, students cued to comprehension maintained

higher comprehension scores across all levels of the repeated reading variable

than those cued to read quickly and accurately. Conversely, students cued to

read quickly and accurately maintained higher reading rate scores from level

to level of the repeated reading variable than those cued to read for

comprehension.

Discussion

The results of the present study provide clarification of the effects of

repeated reading on both fluency and comprehension. Most importantly, the

effects on comprehension should not be considered as only a secondary pur-

pose for using this methodology. The data in this study indicate that repeated

reading facilitates significant comprehension gains. Regardless of the cue they

received, students retold a significantly greater proportion of the story

propositions between one and three or seven readings. Comprehension scores

increased on the average by 7% after three readings and 11 % after seven.

These effects of repeated reading on comprehension do not, however, dis-

count the significant increases achieved in fluency. Under both cue conditions,

readers increased their reading rates from level to level of repeated reading.

The average increase from a single reading to three readings was approxi-

mately 24 words per minute, while an increase of 12 words per minute was

achieved between three and seven readings. Additional reading rate measures

were taken on each intermediate reading to examine the progression of gains.

Four readings appear to be optimal since, after four readings, 83% of the

fluency increase between one and seven readings is achieved. This finding is

congruent with the results of Spring et al. (1981), who found that with three to

five practice readings students reach an optimal fluency level. If, as Samuels

(1979) and Carver and Hoffman (1981) reported, fluency increases generalize

to new reading material, the same number of readings might produce higher

rates when students are exposed to the same level of material.

Students in the present study initially read at rates that ranged from 70 to

119 words/minute. With repeated readings, their reading rates rapidly sur-

passed 120 words/minute. According to Starlin and Starlin (1973), im-

provement in fluency from below 120 words/minute to above 120

words/minute represents a qualitative change from instructional level (at

which further instruction is required) to independent level (at which no further

instruction is required). Students in the fluency cue condition reached inde-

pendent levels after two readings; students in the comprehension cue condition

did so after three. These findings are consistent with Gonzales and Elijah's

(1975) results.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015Attentional Cues 139

The change from instructional to independent level may be explained by

the apparent stabilization of error patterns through concentrated practice.

Studies on oral reading errors (Gonzales & Elijah, 1975; O'Shea, Munson, &

O'Shea, in press) have shown that students demonstrate erratic error patterns

when words are presented in context; words read correctly one day are read in.-

correctly on other days. Students repeatedly reading passages, however,

become more familiar with vocabulary, syntax, and content of passages and

appear to respond with more consistent accuracy and faster speeds. Con-

sequently, error rates decrease as reading rates increase.

The results of the tests on the attentional cue variable show that students

respond as directed to external cues. Students cued to fluency read more words

per minute, and students cued to comprehension retold a greater proportion of

propositions. This is in partial agreement with earlier research by Pehrsson

(1974), who found a general comprehension cue to be effective for increasing

story retellings. However, Pehrsson's fluency cue slowed students' reading

rates. This conflicting result can be attributed to the difference in cues;

Pehrsson cued students to accuracy, not speed and accuracy. Consequently,

his students slowed their reading rates in order to identify words correctly.

Differences also exist between the results reported by Frase and Kreitz-

berg (1975) and the present findings. These researchers found that cues to

comprehension must be direct and specific in order to be effective. In the

present study, however, the comprehension cue was general and effective. Two

points may explain the difference. First, the comparisons were different; Frase

and Kreitzberg compared general and specific cues to no cue at all, while we

compared a fluency cue to a general comprehension cue. Second, the reading

maturity of the students differed; they used college students, while third

graders were used in this study.

On the other hand, these results are congruent with Grant and Hall

(1967), who found that topical cues, similar to the general cue used by Frase

and Kreitzberg, were effective for increasing the comprehension of elementary

school students. This was true, however, only for average ability students.

Students in this study also read at or above grade level (as determined by scores

from the California Achievement Test). Thus, additional research is necessary

to determine whether comprehension cues produce similar effects for below

average and above average readers.

The strongest evidence for the effectiveness of the comprehension cue was

the average comprehension score of students in the comprehension cue con-

dition after a single reading. These students, on the average, retold the same

proportion of propositions as students in the fluency cue condition after seven

readings. When the comprehension cue was combined with repeated readings,

fluency and comprehension increased. It appears that cuing aids in maximizing

comprehension by focusing students' attention and repeated reading aids

fluency as well as comprehension by providing concentrated practice.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015140 Journal of Reading Behavior

The most important general implication that emerges from these results is

that both repeated reading and attentional focus are effective means for in-

creasing fluency and comprehension. Specifically, the optimal strategy seems

to be to have students practice reading passages at their instructional level

about four times while cuing them to read for comprehension. The cue em-

phasizes the primary goal of reading: communication of thoughts and ideas

about the world through written language. Repeated reading provides students

with the necessary practice to build fluency, acquire new information, and

maintain established information. In this regard, repeated reading appears to

be preferable to word recognition practice with words in isolation.

Also, the results of repeated reading have implications for the accuracy of

informal reading inventories (IRIs) used in the assessment and placement of

students. Assessments based upon single readings of freshly presented

passages may not provide an accurate evaluation of a student's decoding skills

(Gonzales & Elijah, 1975). Students face considerable uncertainty when they

are asked to read orally a new passage as required in many IRIs, As shown in

this study, reading accuracy and speed increase dramatically with a second

reading. After the first reading, students may have a general understanding of

the passage which can be used during subsequent readings to reduce uncer-

tainty and aid them in the use of context to identify words.

One major limitation of this study is the limited generalizability of the

results across populations and time. To control the between-subject vari-

ability, students were chosen from a somewhat narrow population. As a conse-

quence, generalizations about the effects of both attentional cues and repeated

readings must be limited to other students with similar characteristics and

reading material of comparable difficulty. In addition, generalizations about

the effects over time should be approached cautiously. The dependent

measures were taken on specific passages immediately following the readings;

no tests of latency effects were undertaken.

A second limitation is the single measure of reading comprehension used.

Correlations between the CAT comprehension subtest and total reading scores

and the proportion of propositions retold were both found to be .37. This

moderate relation between the CAT measures and the story retelling measure

implies questionable concurrent validity for the latter. However, Carver and

Hoffman (1981) reported increases on a MAZE task after repeated reading,

and DiStefano et al. (1981) found gains measured by questions when alter-

native cues were provided. Consequently, further investigation of the effects

of the attentional cues and repeated readings on a variety of comprehension

measures seems warranted.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015A ttentional Cues 141

References

BLANCHARD, J. S., & McNINCH, G. H. (1980). Testing the decoding sufficiency hypothesis:

A response to Fleisher, Jenkins, and Pany. Reading Research Quarterly, 15, 559-564.

BONING, R. (1963). Getting the facts: Specific skills series. Baldwin, NY: Barnell Loft.

BRAY, J, H., & MAXWELL, S. E. (1982). Analyzing and interpreting significant MANOVAs.

Review of Educational Research, 52, 340-367.

BRITTON, B. K., ZlEGLER, R., & WESTBROOK, R. (1980). Use of cognitive capacity in

reading easy and difficult text: Two tests of an allocation of attention hypothesis, Journal of

Reading behavior, 12, 23-30.

CARVER, R. P., & HOFFMAN, J. V. (1981). The effect of practice through repeated reading on

gain in reading ability using a computer-based instructional system. Reading Research

Quarterly, 16, 374-390.

CHOMSKY, C. (1976). After decoding: What? Language Arts, 53, 288-296.

CROMER, W. (1970). The difference model: A new explanation for some reading difficulties.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 61, 471-483.

DAHL, P. R. (1979). An experimental program for teaching high speech word recognition and

comprehension skills. In J. E. Button, T. C. Lovitt, & T. D. Rowland (Eds.), Communi-

cations research in learning disabilities and mental retardation (pp. 33-65). Baltimore:

University Park Press.

DiSTEFANO, P., NOE, M., & VALENCIA, S. (1981). Measurement of the effects of purpose

and passage difficulty on reading flexibility. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73,

602-606.

FLEISHER, L. S., JENKINS, J. R., & PANY, D. (1979). Effects of poor readers' comprehension

of training in rapid decoding. Reading Research Quarterly, 15, 30-48.

FRASE, L. T., & KREITZBERG, V. S. (1975). Effect of topical and indirect learning directions

on prose recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 67, 320-324.

FRY, E. B. (1968). A readability formula that saves time. Journal of Reading, 11, 513-516;

575-577.

GONZALES, P. C., & ELIJAH, D. V. (1975). Rereading: Effect on error patterns and perfor-

mance levels on the IRI. Reading Teacher, 28, 647-652.

GRANT, E. B., & HALL, M. (1967). The effect of purposeful reading on comprehension at dif-

fering levels of difficulty. Paper presented at the International Reading Association Conven-

tion, Seattle,

HARRIS, R. J. (1975). A primer of multivariate statistics. New York: Academic Press.

KINTSCH, W. (1974). The representation of meaning in memory. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

L A B E R G E , D., & SAMUELS, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information pro-

cessing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6, 293-323.

O'SHEA, L. J., MUNSON, S., & O'SHEA, D. J. (in press). Error correction in oral readings:

Evaluating the effectiveness of three procedures. Education and Treatment of Children.

PEHRSSON, R. S. V. (1974). The effects of teacher interference during the process of reading or

how much of a helper is Mr. Gelper? Journal of Reading, 17, 617-621.

PERFETTI, C. A., & HOGABOAM, T, (1975), Relationship between single word decoding and

comprehension skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 67, 461-469.

SAMUELS, S. J. (1979). The method of repeated readings. The Reading Teacher, 32, 403-408.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015142 Journal of Reading Behavior

SMITH, F. (1978). Understanding reading: A psycholinguistic analysis of reading and learning to

read. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

SPRING, C., BLUNDEN, D., & GATHERAL, M. (1981). Effect on reading comprehension of

training to automaticity in word-reading. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 53, 779-786.

STARLIN, C., & STARLIN, A. (1973). Guides for continuous decision making. Bemidji, MN:

Unique Curriculum Unlimited.

TIEGS, E. W., & CLARKE, W. W. (1970). California achievement test. Monterey, CA:

CTB/McGraw-Hill.

Downloaded from jlr.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015You can also read