The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

w k w5 b W ‰5 v N b u | I N U I T TA P I R I I T K A N ATA M I

The Digital Divide:

Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat

Our Vision:

Canadian Inuit are

prospering through unity

and self-determination

Our Mission:

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

is the national voice for

protecting and advancing

the rights and interests

of Inuit in Canada

ITK Quarterly Research Briefing

Summer 2021, Issue No. 3About Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) is the national representative organization for the 65,000 Inuit in Canada, the majority of whom live in Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit home land encompassing 51 communities across the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (Northwest Territories), Nunavut, Nunavik (Northern Québec), and Nunatsiavut (Northern Labrador). Inuit Nunangat makes up nearly one third of Canada’s landmass and more than 50 percent of its coastline. ITK represents the rights and interests of Inuit at the national level through a democratic governance structure that represents all Inuit regions. ITK advocates for policies, programs, and services to address the social, cultural, political, and environmental issues facing our people. ITK’s Board of Directors are as follows: • Chair and CEO, Inuvialuit Regional Corporation • President, Makivik Corporation • President, Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated • President, Nunatsiavut Government In addition to voting members, the following non-voting Permanent Participant Representatives also sit on the Board: • President, Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada • President, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada • President, National Inuit Youth Council Vision Canadian Inuit are prospering through unity and self-determination. Mission Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami is the national voice for protecting and advancing the rights and interests of Inuit in Canada. ITK Quarterly Research Briefings ITK Quarterly Research Briefings provide analysis of timely policy matters that are of direct relevance to Inuit. Briefings are prepared by Inuit Qaujisarvingat, ITK’s research department, consistent with the department's mandate to produce research and analysis that can be used to support the advancement of Inuit priorities. ITK Quarterly Research Briefings are a deliverable of ITK’s 2020-2023 Strategy and Action Plan. © Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, August 2021 Cover image: © Inuvialuit Regional Corporation. Satellite artwork by Sheree McLeod.

Introduction The availability of high-speed broadband internet in Inuit Nunangat lags behind the rest of Canada as well as behind many other Arctic jurisdictions. Affordable, high-speed broadband is imperative for Inuit to be able to participate equitably in society and the economy. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the digital divide between Inuit Nunangat and the rest of Canada into sharper focus. The experiences of people in Inuit Nunangat whose education and livelihoods became more reliant on the internet during the pandemic further underscore how the lack of high-speed broadband in the region puts our people at a disadvantage. Broadband connectivity supports educational attainment, spurs economic development, and can improve access to services such as health care, in a region where service delivery is challenging. The limited availability of high-speed broadband in Inuit Nunangat places the region at a competitive disadvantage and limits or precludes the use of technologies that rely on high-speed broadband. Canadian federal policy and investments that are intended to improve broadband connectivity in Inuit Nunangat have tended to prioritize satellite dependence, contributing to the widening digital divide between Inuit Nunangat and the rest of the country. The service provided by Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in Inuit Nunangat consequently tends to be slow, unreliable, and prohibitively expensive. In recent years, the federal government has pledged to improve access to high-speed broadband for all Canadians and invested in broadband connectivity. In 2019, the Canadian federal government released its national broadband connectivity strategy and announced major new investments for improving broadband connectivity throughout the country, including through the Universal Broadband Fund. However, it is unclear what impacts these initiatives will have on Inuit Nunangat. This quarterly research brief provides an overview of the reality of internet access in Inuit Nunangat and also evaluates future infrastructure required to bridge the digital divide between Inuit Nunangat and the rest of Canada. Promising international practices are highlighted and compared with Canada’s current connectivity strategy. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat 1

Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat

Canada is ranked relatively high among the Organization for Economic Co-operation

and Development (OECD) nations in terms of the proportion of the population

connected to broadband internet, as well as the broadband speeds available to

them. Approximately 41% of the Canadian population is connected to broadband

through either Digital Subscriber Line (DSL), cable, fibre, or fixed wireless.1 Canada

ranks eighth among OECD nations for fixed broadband subscriptions per capita,

with 37inhabitants out of every 100 having access to download speeds greater than

25 megabits per second (Mbps).2

Broadband in Inuit Nunangat is, by contrast, inaccessible for many Inuit due in large

part to high costs. The cost to private households of accessing the fastest service

levels available range from $95 per month in Nunatsiavut3 to $150 per month in

Nunavik and Nunavut.4 None of the fastest service levels available in these regions

come close to the 50 Mbps download and 10 Mbps upload, commonly written as

50/10 Mpbs, universal target speed called for by the federal government.

According to the 2017 Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 68% of Inuit households in Inuit

Nunangat have access to internet at home compared to 91% of Inuit households

outside of Inuit Nunangat.5 Of the Inuit households in Inuit Nunangat that do not

have internet at home, 54.5% identify cost, 10.2% identify lack of equipment, and

2.9% identify unavailability of service as contributing factors for their lack of access.6

As a comparison, in 2018, 94% of all Canadians had home internet access, and

among those who did not, 28% identified cost, 19% identified equipment, and

8% identified unavailability of internet service as the main factors prohibiting

internet access in their homes.7

Broadband connectivity throughout Inuit Nunangat tends to be slow and

unreliable, and is frequently jeopardized by weather and technical difficulties. The

community of Ulukhaktok in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR), Northwest

Territories lost internet connection for eight days straight following a power outage

in late February 2021. This outage affected banking and credit transactions,

jeopardizing residents’ ability to pay for groceries and gas.8 Across Inuit Nunangat

only Inuvik in the ISR is connected to Canada’s fibre optic network via the Mackenzie

Valley Fibre Link built in 2017. Access to fibre enabled New North Networks, a

local service provider that serves Inuvik, to provide unlimited internet plans in

2020 for the first time in that community. Service providers serving the other

50 communities in Inuit Nunangat rely almost exclusively on bandwidth rented

from third-party satellite providers.

2 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit NunangatTelecommunications services are regulated by the federal government as public

utilities in Canada. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications

Commission (CRTC) is the federal agency responsible for regulating telecommuni-

cations services under the Telecommunications Act. In 2016, CRTC established

the universal service objective of ensuring that fixed broadband internet service

subscribers should be able to access speeds of at least 50 Mbps download and 10

Mbps upload, and to subscribe to a service offering with an unlimited data al-

lowance.9 However, at this time, Inuvik is the only community in Inuit Nunangat

that has access to these service levels.

Excluding Inuvik and those communities for which data are unavailable,

18 communities in Inuit Nunangat have maximum download/upload speeds of

5/1 Mbps or less and 27 have maximum download speeds of 15 Mbps.10 Download

and upload speeds vary between communities and between regions. Excluding

Inuvik (ISR), the maximum download/upload speed available in the ISR and

Nunatsiavut is 5/1 Mbps. Maximum download/upload speeds in Nunavik are less

than 5/1 Mbps.11 It is notable that the CRTC’s now decade-old universal service

objective from 2011 of 5/1 Mbps is only just being met in Nunavik and in some ISR

and Nunavut communities, let alone the current 50/10 Mbps objective. A summary

of maximum download/upload speeds by region is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Maximum download/upload speeds and type of connection by Inuit

Nunangat region.12 Note that the below speeds are not necessarily available in

every community within a given region, but rather reflect the maximum speed

commonly available across each region.

Region Maximum Type of

Download/Upload Speed Connection

Available in Region (Mbps)

Inuvialuit Settlement Region 15/1* DSL

†

Nunavut 25/1 Direct-to-home

Satellite

Nunatsiavut 5/1† Anik Satellite

Nunavik 15/2 Fixed Wireless

* Note that this maximum excludes the outlier of Inuvik, which is the only community in Inuit

Nunangat to reach 50/1 Mbps download/upload speeds

† Note that this speed is the maximum theoretical speed available from current direct-to-home

satellite and Anik satellite connections, but these connections are often throttled due to high

demand resulting in much slower average speeds

Slow download/upload speeds limit the technological capacity of Inuit households.

To successfully download large files or stream video on more than one device

a download speed of over 25 Mbps is recommended.13 This speed is not reliably

available in any community in Inuit Nunangat, excluding Inuvik.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat 3Broadband Access and Society

As with other Canadians, Inuit families transitioned to spending more time online

during the COVID-19 pandemic, and some schools in Inuit Nunangat prescribed

online learning in place of in-school lessons for varying durations. In some regions,

such as Nunavik, the pandemic has led to the region’s service provider utilizing all

of the bandwidth available to the satellite-dependent region, and struggling to

meet demand.14

According to ITK's own analysis for the Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee, primary

and secondary schools in all four regions of Inuit Nunangat reported general

dissatisfaction with broadband connectivity before the pandemic, tending to limit

in-class internet use of the basic search functions due to slow download speeds.

Bandwidth limitations often curtail the full use of video conferencing capabilities

and distance education courses in schools throughout the region. Although the

impacts of school closures in Inuit communities on learning remain unclear, limited

access to broadband coupled with other factors, such as household crowding, may

further impede learning in some communities across Inuit Nunangat.

The costs, speed, and reliability of broadband in Inuit communities also hinders

the ability of Inuit to pursue post-secondary distance learning opportunities.

Distance learning can be a viable means for Inuit to earn advanced degrees without

having to leave our communities and regions. However, broadband costs can be

prohibitive, particularly when high data use videoconferencing software is used

that can contribute to costly overages. For example, some students pursuing

post-secondary degrees through distance learning pay $250 a month for capped

broadband plans that charge high fees for overages.15

The potential benefits to Inuit Nunangat of high-speed broadband connectivity are

far reaching, and could be leveraged to further improve access to education,

research, essential services, and economic development. The National Inuit Strategy

on Research (NISR) calls for investment in broadband access and regional capacity

to engage in Inuit Nunangat research.16 Inuit have also linked advancements in

technology to potential improvements in service delivery, including the potential

for telehealth videoconferencing to improve access to psychiatric and psychological

care.17 However, the viability of such technologies are usually contingent on the

availability of reliable, high-speed broadband. The Kativik Regional Government

(KRG) estimated in 2016 that the deployment of undersea fibre in the region could

reduce annual expenditures for health travel, justice travel, and KRG travel by up to

$5 million annually, and curtail annual expenditures on satellite broadband by

nearly $6.5 million. KRG estimated the cost savings of fibre deployment at that time

of up to half a billion dollars over a 25-year period.18

4 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit NunangatVideoconferencing can be utilized to improve access to justice and reduce the cost of administering justice services throughout Inuit Nunangat, where people are often held in remand for extended periods because they are required to travel to in-person bail hearings.19 Bail hearings by videoconference have been available in Kuujjuaq and Puvirnituq, Nunavik, Quebec, since October 2019 with the objective of reducing time in remand as well as costly and lengthy travel to bail hearings in Amos, Quebec.20 However, the opportunity to utilize videoconferencing for remote hearings more widely in Inuit Nunangat could be limited by the lack of access to reliable, high-speed broadband.21 Other nations are focusing on broadband connectivity as a means of improving service delivery. The United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) recently invested $6.5 million in the Alaska-based National Telehealth Technology Assessment Resource Center (TTAC) in order to assess the broadband capacity available to rural health care providers and patient communities to improve access to telehealth services.22 TTAC is based out of the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, whose Telehealth Department already provides a variety of telehealth services.23 The implementation of similar services in communities across Inuit Nunangat could help close gaps in mental health service delivery that contribute to poor mental health outcomes, addictions, and risk for suicide. Comparing Fibre and Satellite Broadband infrastructure in Inuit Nunangat relies almost entirely on satellite connectivity, which is currently connected exclusively through the use of high-earth orbit geostationary (GEO) satellites.24 GEO satellites are stationed 36,000 kilometers above Earth, resulting in high latency times for data to be sent and returned. Low- Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites, in contrast, operate between 500 and 2,000 kilometres above Earth’s surface, resulting in low latency times and the possibility of high- speed connections (see Figure 1).25 LEO satellites are a relatively new technology that some believe will help close the digital divide between remote and urban communities. Internet service providers typically buy bandwidth from satellite providers through reoccurring rental fees. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat 5

Figure 1. Geostationary vs Low Earth Orbit satellite orbits26

36,000km

High Earth Orbit

Geostationary

(GEO) satellites

500-2,000km

Low Earth Orbit

(LEO) satellites

Successive federal governments have prioritized unambitious, cost-ineffective

investments in Inuit Nunangat that contribute to dependence on GEO satellites.

Between 1994 and 2021, total direct federal expenditures on broadband for under-

and unserved communities in Canada will total $2.5 billion, possibly closer to

$3 billion if other indirect programs are included.27 However, the bulk of that

investment has gone into satellite bandwidth rather than extending fibre connectivity

to underserved communities. In 2017, the department of Innovation, Science and

Economic Development Canada estimated that $2 billion could have instead brought

fibre to every community in the North, presumably including Inuit communities.28

Canada is betting on LEO satellites providing rural and remote communities with

service levels that are comparable to fibre through recent investments totalling at

least $1 billion. Budget 2018 allocated $100 million over five years for the Strategic

Innovation Fund, with a particular focus on supporting projects that relate to LEO

satellites and next generation rural broadband.29 The 2019 federal budget pledged

a further $600 million to secure capacity on LEO satellites through Telesat,

which plans to launch its constellation of LEO satellites in late 2022. The province

of Quebec signed a preliminary agreement in February 2021 that could result in

the province investing $400 million in Telesat’s network.30 The planned launch of

thousands of LEO satellites by major corporations (e.g., SpaceX and Telesat) has the

potential to shift current dependence on GEO satellite connectivity in rural and

northern regions, including Inuit Nunangat, to LEO satellites.31 These satellite

constellations may be capable of providing 50/10 Mbps high-speed connectivity,

meeting CRTC’s current universal service objective.32 However, investments in fibre

would likely be a more cost-effective use of these funds.

6 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit NunangatFibre infrastructure can have relatively high upfront capital costs, particularly with large-scale projects connecting rural communities to fibre.33 However, fibre technology has the potential of delivering much higher speeds than satellite systems, with current fibre services in southern Canada enabling download speeds of up to 1500 Mbps, far faster than speeds promised by LEO satellite.34 The future of fibre connectivity holds promise of even greater speeds, with researchers sending more than 1.4 terabits of information per second through commercial-grade fibre optic lines,35 and even faster speeds available through multi-core fibres.36 The costs of major fibre projects in the Arctic, such as Greenland Connect and Greenland Connect North, suggest that investing in fibre would likely be more cost effective than investments currently being made in LEO satellites when considering download and upload speeds, dependability, and infrastructure lifespan. For example, TELE Greenland spent approximately $50,500 per kilometer on the Greenland Connect and Greenland Connect North fibre projects. This estimate is based on costs of past projects, and is contingent upon factors such as currency rate and technical costs and requirements. Using these rates, a $1 billion investment could be used to lay nearly 20,000 kilometers of subsea fibre optic cable under the same or similar environmental and geographic conditions.37 To put this distance into perspective, the Arctic Connect fibre project being undertaken in Russia will span the country’s entire Arctic coastline from the northwestern port of Murmansk to the Pacific port of Vladivostok, a distance of approximately 10,000 kilometers.38 The unique environment of Inuit Nunangat poses challenges for both fibre and satellite connectivity. Satellite connectivity is plagued with poor connection due to fog, rain, and snow. In August 2019, rain and fog along the north coast of Labrador cut off phone and internet service to Nain, Nunatsiavut for over a week.39 Fibre lines are fragile and costly to lay and maintain in permafrost and difficult terrain.40 These logistical and maintenance challenges must also be considered when determining best practices for broadband connectivity in Inuit Nunangat. Investing in satellite connectivity may be perceived by governments as politically advantageous due to what tend to be relatively faster returns on investments com- pared to investments in major fibre projects. However, investment in fibre is likely more cost effective given the superior quality of service that it enables as well as the relatively long lifespans of fibre cables. LEO satellites can have short lifespans of as little as five years and these satellites are expensive to replace, compared to the decades-long lifespans of fibre optic cables. Satellite bandwidth is limited and, bottlenecked by high demand, broadband speeds can vary greatly.41 There is also no guarantee that the service levels provided by satellite broadband can keep pace with the rapid expansion possible with fibre networks. More research is needed to determine whether or not investments in LEO satellites are truly cost-effective alternatives to fibre in Inuit Nunangat. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat 7

Canada’s National Broadband Connectivity Strategy

The federal department of Rural Economic Development released High-speed

Access for All: Canada’s Connectivity Strategy in 2019. The Strategy pledges that the

federal government will work with partners to achieve universal 50 Mbps download

and 10 Mbps upload speeds (50/10 Mbps) for all Canadians, connecting “the

hardest-to-reach Canadians” by 2030.42 However, it is unclear whether or not this

specific download/upload speed target will be sufficient relative to the rest of the

country in a decade from now.

The federal government has invested in several recent programs and initiatives that

are intended to improve broadband connectivity in Canada and to support

the achievement of the objectives identified in Canada's Connectivity Strategy. For

example, the 2019 federal budget allocated up to $1.75 billion into the Universal

Broadband Fund, a program that has since launched and is designed to fund

broadband infrastructure projects that achieve the CRTC's current universal service

objective.43 However, there is no Inuit Nunangat-specific allocation within the Fund.

Broadband Initiatives in Inuit Nunangat

Promising initiatives to improve broadband connectivity in Inuit Nunangat are

being planned or are underway. The KRG is currently overseeing a significant

initiative in Nunavik to improve access to high speed broadband by transitioning

the region from satellite dependence to fibre by 2025. KRG secured $125 million in

federal and provincial support in 2018 for its initiative to use fibre optic cables,

microwave towers, and surplus satellite capacity to improve connectivity in the

region.44 The seabed along the Hudson's Bay coast was mapped between Chisasibi

and Puvirnituq the same year and the KRG intends to lay a fibre optic cable along

the coast between the two communities in the summer of 2021, with spurs

connecting to Kuujjuarapik, Umiujaq, and Inukjuak.45 KRG expects the cable to

be installed and in operation by December 2021. The CRTC recently announced

$53.4 million to extend a new undersea fibre network north from Puvirnituq to

Akulivik, Ivujivik, Salluit and Kangiqsujuaq, and to build a terrestrial fibre network

from the Naskapi nation of Kawawachickamach to Kuujjuaq.46

The Government of Nunavut’s (GN) ambitions for fibre connectivity are now

contingent on the development of the Nunavik fibre network by KRG. The GN

announced in 2021 that it intends to lay a fibre optic cable connecting Iqaluit to

the cable laid between Chisasibi and Puvirnituq by KRG, or near Salluit pending

the extension of the cable from Puvirnituq to that community. The territorial

government secured $151 million in federal funding to finance the $209 million

plan, and hopes to put out a public procurement in late 2021 seeking a firm to

complete the project.47

8 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit NunangatThe Kivalliq region of Nunavut may also become connected to Canada’s fibre network. The Kivalliq Inuit Association (KIA) is currently carrying out a two-year technical and feasibility study for a project that would establish hydroelectric and fibre optic links between the Kivalliq region of Nunavut and Manitoba. KIA secured $1.6 million in 2019 from the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor) in order to determine the feasibility of linking Gillam, Manitoba to Arviat, Whale Cove, Rankin Inlet, Chesterfield Inlet and Baker Lake, Nunavut.48 Broadband Initiatives in Other Arctic Jurisdictions Several Inuit communities in Canada’s neighboring jurisdictions, Alaska and Greenland, are connected to fibre optic networks. In 2017, Alaska-based telecommunications operator Quintillion activated a land- and sea-based fibre optic cable linking Nome, Kotzebue, Point Hope, Wainwright, Utqiaġvik, and Prudhoe Bay to the state’s fibre optic network via Fairbanks.49 In 2008, the Greenland Connect project led by TELE Greenland laid submarine fibre optic cables between Nuuk and Qaqortoq, Greenland that link to cables laid between Greenland and Newfoundland and between Greenland and Iceland. The cables were activated in March 2009 and were extended north in 2017 from Nuuk to the communities of Maniitsoq, Sisimiut, and Aasiaat. Microwave relay stations that are connected to Greenland’s fibre network provide internet service to smaller communities along the coast. Only communities in East Greenland and four communities in North Greenland are served by GEO satellite. TELE, Greenland’s service provider, administers the country’s telecommunications infrastructure. Its objective is to enable residents from Nanortalik in South Greenland to Upernavik in North Greenland to enjoy the same high-speed internet as the residents of the capital Nuuk, and the large townships, where 92% of Greenland’s population lives.50 TELE’s investments in developing Greenland’s fibre optic network enable 93% of the population to access high speed broadband over DSL or fixed wireless, and whose flat rate priced maximum download and upload speeds for private users are 30/5 Mbps.51 Other countries with Arctic territory have also prioritized the installation of high-speed broadband in rural and remote communities. Many households in Arctic municipalities in Norway, Sweden, and Finland have access to high capacity fixed broadband speeds of at least 30 Mbps.52 In 2010, Finland became the first country to enshrine in law the right of every citizen to access a 1 Mbps broadband connection, and is seeking to secure access to 100 Mbps connections for all house- holds by 2025. At the end of 2018, nearly 60% of Finnish households had access to a fixed broadband network with the speed of at least 100 Mbps.53 In Lapland, Finland’s northernmost province, 55% of households have access to download speeds of 100 Mbps or greater.54 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat 9

Finland’s national broadband implementation strategy supports the construction

of fibre networks to areas that lack business incentives to build high speed

networks. The strategy was launched by government resolution in 2008 and is

overseen by the Finnish Transport and Communications Agency (Traficom). By the

end of 2019, state aid granted since 2011 to support the strategy had helped build

25,000 kilometers of fibre networks and has led to precipitous year over year

increases in the number of broadband subscriptions sold in the country.55

The Arctic Connect project, which aims to improve connectivity in the Arctic and

between Europe and Asia, would link Europe and Asia through a submarine fibre

optic cable laid on the seabed along the Northern Sea Route. The project involves

laying a fibre optic cable from China to Japan, and onward along Russia’s Arctic

coastline to the Norwegian city Kirkenes. The cable would also include a branch

with a landing station in Alaska, as well as in several Russian Arctic cities.56

Arctic Connect was initiated in 2016 by the Finnish Ministry of Transport and

Communications and is being built through a joint venture by the Finnish state-

owned infrastructure operator Cinia Ltd. in partnership with MegaFon, a Russian

telecommunications operator. The cable will be owned by an international

consortium that includes Japan, Norway, and Finland, and is expected to cost

0.8 to 1.2 billion USD.57 However, Russia has also initiated the development of a

separate subsea cable project from Murmansk to Vladivostok at an estimated cost

of 0.86 billion USD, creating ambiguity about whether there is space for two Arctic

cables competing for the same market.58

Jurisdictions with Arctic territory have either already undertaken or are in the

process of undertaking major fibre installation projects. These initiatives are

indicative of the shared political commitment some jurisdictions have to bringing

high-speed broadband to Arctic communities. In many respects, Canada stands

alone among Arctic nation states in continuing to use the relative remoteness

of Inuit communities as an excuse to continue overlooking Inuit Nunangat infra-

structure needs, including high-speed broadband.

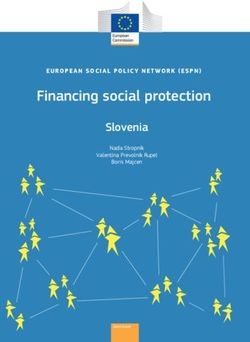

10 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit NunangatFigure 2. International Arctic broadband connectivity

initiatives and achievements

Broadband connectivity in Arctic Canada

lags behind other Arctic States

CANADA

One of 51 Inuit communities has access to fixed highspeed

broadband and is connected to the country’s fibre optic

grid

GREENLAND

The country’s fibre optic network enables 93% of the

population to access download speeds up to 30Mbps

through DSL or fixed wireless

FINLAND

55% of households in the northernmost province of Lapland

have access to download speeds of 100Mbps or greater3

U.S.A.

Land and sea-based fibre optic cables in Alaska make

landings in five Inuit communities4

RUSSIA

Through the Arctic Connect fibre project, a 10,000km fibre

optic cable is being installed that will span the country’s

Arctic coastline from Murmansk to Vladivostok5

Sources:

1. Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “National Broadband Internet Service

Availability Map”, Government of Canada. January 14, 2021, accessed February 21, 2021.

2. Frank Gabriel (TELE Greenland, Senior Key Account Manager), personal communication, May 30, 2021.

3. Finnish Transport and Communications Agency. “100Mb broadband available in nearly 60% of

households,” April 17, 2019, accessed May 28, 2021.

4. Tim Ellis, “New fiber-optic cable system to turbocharge North Slope broadband access.” Alaska Public

Media. December 5, 2017, accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.alaskapublic.org/2017/12/05/new-

fiber-optic-cable-system-to-turbocharge-north-slope-broadband-access/.

5. Alexandra Middleton and Bjorn Ronning, “Arctic subsea cables knowns and unknowns,” High North News,

December 1, 2020, accessed February 10, 2021. https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/arctic-subsea-

cables-knowns-and-unknowns

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat 11Conclusion

The growing digital divide between Inuit Nunangat and the rest of Canada

compounds existing social and economic inequities in the region, places it at a

competitive disadvantage, and precludes wider usage of technologies to improve

service delivery. The relatively high costs of broadband contribute to a much smaller

proportion of Inuit households having access to the internet compared to other

Canadians. The federal government has contributed to this divide by prioritizing

investments that create satellite dependence, with the result that service levels in

some communities reflect targets identified by the CRTC more than a decade ago.

Inuit communities would be better served if governments invested in major fibre

projects connecting Inuit Nunangat communities to the country’s fibre network

rather than potentially widening the digital divide through investments in

LEO satellite technology. Investments in LEO satellite technology will continue to

create a significant disincentive for fibre builds, setting Canada apart from most

other jurisdictions with Arctic territory who have prioritized investments in fibre

infrastructure.

With the exception of Inuvik, Inuit communities do not have access to the

broadband service levels targeted by the CRTC which are the focus of Canada’s

broadband connectivity strategy. In contrast to Canada, all other jurisdictions

with Arctic territory have prioritized investments in fibre networks as a long-term

solution to bringing high-speed broadband to Arctic residents and supporting the

development and sustainability of Arctic communities. Promising initiatives do exist

in Inuit Nunangat that are being led by Inuit and governments. These include the

KRG’s efforts to completely transition the region from satellite dependence to fibre,

the GN’s efforts to connect Iqaluit, Nunavut to that fibre network, as well as the

initial phases of the KIA’s exploration of a hydro-fibre link between Manitoba and

Kivalliq region communities.

These projects seek to bridge the ever widening gap between broadband

connectivity in Inuit Nunangat and the rest of Canada. However, without dedicated

resources and forward-thinking investment in technology, Inuit will remain at a

disadvantage.

12 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit NunangatReferences

1 OECD, “OECD Fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants, by technology, June 2020,” accessed

March 31, 2021, http://www.oecd.org/sti/broadband/broadband-statistics/.

2 OECD, “Fixed broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants, per speed tiers, June 2020,” accessed

March 31, 2021, http://www.oecd.org/sti/broadband/broadband-statistics/.

3 Bell Aliant, phone conversation with author, February 4, 2021.

4 “Internet Plans”, Ssi Qiniq, accessed February 3, 2021, https://www.qiniq.com/internet#plans.

5 Statistics Canada, Labour Market Experiences of Inuit: Key findings from the 2017 Aboriginal Peoples Survey

(November 26, 2018), accessed February 18, 2021,

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-653-x/89-653-x2018004-eng.htm.

6 Aboriginal Peoples Survey 2017, “Reason for no household access to home internet by Inuit identity,

Inuit region, 2017,” email message to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, June 15, 2020.

7 Statistics Canada, “Canadian Internet use survey,” The Daily, October 29, 2019, accessed February 18, 2021,

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/191029/dq191029a-eng.htm.

8 Mackenzie Scott, “Internet restored in Ulukhaktok as blizzard touches down”, CBC News, March 5, 2021,

accessed March 10, 2021,

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/internet-restored-ulukhaktok-blizzard-1.5939407.

9 Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. Telecom Regulatory Policy CRTC 2016-496.

Ottawa, 21 December 2016. Accessed February 4, 2021, https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/archive/2016/2016-496.pdf.

10 Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “National Broadband Internet Service

Availability Map”, Government of Canada, January 14, 2021, accessed February 21, 2021.

11 Ibid.

12 Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications, “Response to ITK on Internet Access Data”,

email correspondence, March 7, 2021.

13 Devon Delfino, “’What is a good internet speed?’: The internet speeds you should aim for, based on how

you use the internet”, Business Insider, April 20, 2020, accessed March 11, 2021,

https://www.businessinsider.com/what-is-a-good-internet-speed.

14 Sarah Rogers, ""Tamaani tackling Nunavik bandwidth woes, but needs government support,"

Nunatsiaq News, October 29, 2020, accessed February 27, 2021, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/

tamaani-tackling-nunavik-bandwidth-woes-but-needs-government-support/.

15 Emma Tranter, “Deeply disturbing:’ Nunavut internet still slower, more costly than rest of country,”

CTV News, January 24, 2021, accessed February 14, 2021, https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/

deeply-disturbing-nunavut-internet-still-slower-more-costly-than-rest-of-country-1.5280029.

16 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, National Inuit Strategy on Research Implementation Guide, Ottawa: Inuit Tapiriit

Kanatami, 2018, accessed March 11, 2021, https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/

ITK_NISR_Implementation-Plan_Electronic-Version.pdf.

17 Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., Annual Report on the State of Inuit Culture and Society 13-14 (Iqaluit, 2014), 2.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat 1318 Kativik Regional Government, “The unconventional business case: Undersea fibre optics for Nunavik,”

SCNATEA Conference, June 2016.

19 Sarah Rogers, “Nunavik police say video conferencing could speed up bail hearings,” Nunatsiaq News,

December 4, 2018, accessed February 15, 2021, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/

nunavik-police-say-video-conferencing-could-speed-up-bail-hearings/.

20 Elaine Anselmi, “Nunavik now offers bail hearings by video,” Nunatsiaq News, December 3, 2019, accessed

February 15, 2021, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/nunavik-now-offers-bail-hearings-by-video/.

21 Emma Tranter, “Nunavut courts will face backlog when they reopen, says deputy minister,” Nunatsiaq News,

May 11, 2020, accessed February 15, 2021, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/90376/.

22 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “HHS Invests $8 million to address gaps in rural telehealth

through the Telehealth Broadband Pilot Program,” January 11, 2021, accessed February 14, 2021,

https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/01/11/hhs-invests-8-million-to-address-gaps-in-rural-telehealth-

through-telehealth-broadband-pilot.html#:~:text=media%40hhs.gov-,HHS%20Invests%20%248%

20Million%20to%20Address%20Gaps%20in%20Rural,the%20Telehealth%20Broadband%20Pilot%

20Program&text=The%20TBP%20program%20assesses%20the,their%20access%20to%20telehealth%

20services.

23 Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, “Telehealth – ANMC Telemedicine,” accessed February 14, 2021,

https://anthc.org/telehealth/#:~:text=ANTHC's%20telehealth%20services%20allow%20health,

Native%20people%20across%20the%20state.&text=Support%20and%20training%20for%

20clinics,expand%20existing%20clinical%20service%20lines.

24 Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, “National broadband internet service

availability map”, 14 January 2021, accessed February 2, 2021,

https://www.ic.gc.ca/app/sitt/bbmap/hm.html?lang=eng.

25 Greg Ritchie and Thomas Seal, “Why low-earth orbit satellites are the new space race”, The Washington Post,

July 10, 2020, accessed February 19, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/why-low-earth-

orbit-satellites-are-the-new-space-race/2020/07/10/51ef1ff8-c2bb-11ea-8908-68a2b9eae9e0_story.html.

26 Adapted from Ritchie and Seal (2020)

27 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Recommendations for the Review of the Canadian Communications

Legislative Framework, January 11, 2019, accessed March 9, 2021, https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/

uploads/2019/02/20190111-ITK-submission-to-telecom-policy-review-FINAL.pdf.

28 Susan Hart (Director General, Connecting Canadians Branch, Department of Industry), Evidence before the

Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology on November 27, 2017, accessed February 16, 2021,

http://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/INDU/meeting-85/evidence.

29 Government of Canada, Equality Growth: A Strong Middle Class (February 27, 2018), 120.

30 Steve Scherer and Allison Lampert, “Quebec signs preliminary deal to invest C$400 ln in Telesat satellite

network,” February 18, 2021, accessed March 10, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/telesat-cnda-

quebec-idUSL8N2KO7O7.

31 Ibid.

32 Telesat, Real-Time Latency: Rethinking Remote Networks, accessed February 17, 2021,

https://www.telesat.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Real-Time-Latency_HW.pdf.

14 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat33 Alexandra Posadski, “Internet everywhere, but at a cost: The race for the low-Earth satellite market”,

The Globe and Mail, September 21, 2020, accessed February 3, 2021, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/

business/article-internet-everywhere-but-at-a-cost-the-race-for-the-low-earth/

34 “Packages”, Bell.ca, accessed February 22, 2021, https://aliant.bell.ca/Bell_Internet/Internet_access.

35 James Vincent, “’Fastest ever’ commercial internet speeds in London: Download 44 films in a second”,

The Independent, January 22, 2014, accessed February 22, 2021, https://www.independent.co.uk/

life-style/gadgets-and-tech/fastest-ever-commercial-internet-speeds-london-download-44-films-

second-9077061.html.

36 Sumitomo Electric Industries, Ltd. “Realization of world record fiber-capacity of 2.15Pb/s transmission”,

October 13, 2015, accessed February 22, 2021, https://global-sei.com/company/press/2015/10/prs082.html.

37 Frank Gabriel (TELE Greenland, Senior Key Account Manager), personal communication, March 1, 2021.

38 “Russia starts building $850M high-speed Arctic Internet,” Moscow Times, November 19, 2020, accessed

March 10, 2021, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/11/19/russia-starts-building-850m-high-

speed-arctic-internet-a72089#:~:text=Russia's%20Grand%20Arctic%20Plan%20Will%20Face%20Tough%

20Hurdles&text=The%20high%2Dspeed%20Arctic%20internet,52%2D104%20terabits%20per%20second.

39 “Fog wreaking havoc in Nain for 7 days straight, frustrating travellers”, CBC News, August 7, 2019, accessed

February 2, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/

fog-nain-telecommunications-disruption-1.5238588.

40 “Fibre optic cable advantages and disadvantages”, NM Cabling Solutions, October 26, 2020, accessed

February 20, 2021, https://www.nmcabling.co.uk/2020/10/fibre-optic-cable-advantages-and-

disadvantages/.

41 Xplornet, phone conversation with author, February 5, 2021.

42 Canada, High-speed Access for All: Canada’s Connectivity Strategy (Innovation, Science and Economic

Development Canada, 2019), 8.

43 Government of Canada, "Universal Broadband Fund," accessed February 23, 2021,

https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/139.nsf/eng/h_00006.html.

44 Sarah Rogers, "Nunavik gets funding to launch work on its high-speed internet network," Nunatsiaq News,

August 24, 2018, accessed February 24, 2021, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/65674nunavik_gets_

funding_to_launch_work_on_its_high-speed_internet_network/.

45 Sarah Rogers, “More internet bandwidth on its way to Nunavik,” Nunatsiaq News, February 25, 2021,

accessed February 25, 2021, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/more-internet-bandwidth-on-its-way-

to-nunavik/.

46 Sarah Rogers, “Nunavik gets %53M to expand its fibre optic network”, Nunatsiaq News, March 22, 2021,

accessed March 23, 2021, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/nunavik-gets-53m-to-expand-its-fibre-

optic-network/.

47 Jim Bell, "Nunavut government backs away from Iqaluit-Nuuk fibre-optic cable," Nunatsiaq News,

January 20, 2021, accessed February 24, 2021, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/

nunavut-government-backs-away-from-iqaluit-nuuk-fibre-optic-cable/.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit Nunangat 1548 Sarah Rogers, "Ottawa gives $1.6 million to Kivalliq hydro-fibre link study," Nunatsiaq News,

February 27, 2019, accessed February 25, 2021, https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/

ottawa-gives-1-6-million-to-kivalliq-hydro-fibre-link-study/.

49 Tim Ellis, “New fiber-optic cable system to turbocharge North Slope broadband access,” Alaska Public

Media, December 5, 2017, accessed February 5, 2021, https://www.alaskapublic.org/2017/12/05/

new-fiber-optic-cable-system-to-turbocharge-north-slope-broadband-access/.

50 Government of Iceland, Greenland and Iceland in the New Arctic (December 2020), 78, accessed

February 15, 2021, https://www.government.is/library/01-Ministries/Ministry-for-Foreign-Affairs/

PDF-skjol/Greenland-Iceland-rafraen20-01-21.pdf.

51 Frank Gabriel (TELE Greenland, Senior Key Account Manager), personal communication, May 30, 2021.

52 Nordregio, “Household access to high capacity fixed broadband 2016,” accessed February 9, 2021,

https://nordregio.org/maps/household-access-to-high-capacity-fixed-broadband-2016/.

53 European Commission, “Country information – Finland,” September 1, 2020, accessed February 9, 2021,

https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/country-information-finland.

54 Finnish Transport and Communications Agency, “100Mb broadband available in nearly 60% of

households,”April 17, 2019, accessed May 28, 2021, https://www.traficom.fi/sites/default/files/media/file/

Kiintean-verkon-laajakaistasaatavuus-Tillgang-till-fasta-natet.ods.

55 Finnish Transport and Communications Agency, “Availability of fixed networks,” December 31, 2020,

accessed May 28, 2021, https://www.traficom.fi/en/news/100mb-broadband-available-nearly-60-

households.

56 Finnish Transport and Communications Agency, “Fast Broadband project helps build 25,000 kilometres

of fibre networks,” April 3, 2020, accessed February 10, 2021, https://www.traficom.fi/en/news/

fast-broadband-project-helps-build-25000-kilometres-fibre-networks.

57 Heiner Kubny, “First steps for the Arctic Connect project,” Polar Journal, November 20, 2020, accessed

February 10, 2021, https://polarjournal.ch/en/2020/11/20/first-steps-for-the-arctic-connect-project/.

58 Submarine Cable Networks, “Arctic Connect”, accessed February 10, 2021,

https://www.submarinenetworks.com/en/systems/asia-europe-africa/arctic-connect.

59 Alexandra Middleton and Bjorn Ronning, “Arctic subsea cables: knowns and unknowns,” High North News,

December 1, 2020, accessed February 10, 2021, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/arctic-subsea-

cables-knowns-and-unknowns.

16 Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami The Digital Divide: Broadband Connectivity in Inuit NunangatI M ATA N A K T I I R I P AT T I U N I | u b N v 5‰ W b 5w k w

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

75 Albert Street

Suite 1101

Ottawa, Ontario

Canada K1P 5E7

( 613.238.8181

613.234.1991

www.itk.caYou can also read