Resting frontal electroencephalographic asymmetry in depression: Inconsistencies suggest the need to identify mediating factors

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Psychophysiology, 35 ~1998!, 389 – 404. Cambridge University Press. Printed in the USA.

Copyright © 1998 Society for Psychophysiological Research

Resting frontal electroencephalographic asymmetry

in depression: Inconsistencies suggest the

need to identify mediating factors

STEPHANIE A. REID, LISA M. DUKE, and JOHN J.B. ALLEN

Department of Psychology, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA

Abstract

Two studies of the relationship between depression and resting frontal electroencephalographic ~EEG! activity are

reported. Although considerable research supports the theory of left and right hemispheric specialization for approach

and withdrawal behaviors, only four studies involving clinically depressed individuals have been published to date.

Despite methodological similarities with published research, no significant differences in frontal activation emerged

between depressed and nondepressed participants with either college students having high Beck Depression Inventory

scores ~Study 1! or with individuals diagnosed with DSM-III-R depression ~Study 2!. Post hoc analyses in Study 2

revealed one effect confined to lateral frontal leads during the first 2 min of EEG data; this finding was significant in

only one of three reference montages. Results are discussed in light of methodological considerations and mediating

variables such as temperament and coping styles.

Descriptors: Emotion, Electroencephalography, Individual differences, Lateral dominance, Methodology,

Psychophysiology

A substantial literature has accumulated regarding the putative scores of self-reported depression, compared with the left posterior

roles of the right and left cerebral hemispheres in the expression and right anterior lesions. These findings were replicated in other

and experience of emotion. Clinical observations and studies of studies: depression varied as a function of distance of left anterior

stroke patients were among the first reports concerning differential lesions from the frontal pole—as measured by computerized axial

hemispheric specialization in the expression of emotion. Early tomography scan ~Robinson, 1985!. Moreover, location of lesions

observations of individuals with cerebral infarctions revealed that in the left frontal region was found to be the most important pre-

patients with unilateral left-hemisphere brain damage showed a dictor of post-stroke depression ~Robinson, Lipsey, & Price, 1985!.

higher incidence of “catastrophic” reactions, characterized by neg- Independent investigations into the relationship between lesion

ative affect and crying; joking, indifference, and minimization were and location and depression have yielded conflicting results. Some

more frequently observed in individuals with right-sided lesions studies found evidence supporting the association between left

~Gainotti, 1972!. This early report was confirmed by later studies anterior lesions and depression ~e.g., Astrom, Adolfsson, & Apslund,

in which right hemisphere lesions were correlated with positive 1993; Eastwood, Rifat, Nobbs, & Ruderman, 1989; Finkelstein

emotions such as undue cheerfulness ~e.g., Starkstein et al., 1989! et al., 1982!, whereas others reported a failure to replicate this

and mania ~e.g., Starkstein et al., 1990!. Studies by Robinson and finding ~e.g., Dam, Pedersen, & Ahlgren, 1989; Ebrahim, Barer, &

colleagues further implicated the left cerebral hemisphere, specif- Nouri, 1987; Herrman, Bartels, Schumacher, & Wallesch, 1995;

ically the anterior region, in the experience of depression. In one House, Dennis, Warlow, Hawton, & Molyneux, 1990; Sharpe

report ~Robinson, Kubos, Starr, Rao & Price, 1984!, for example, et al., 1990; Sinyor et al., 1986!. Of note, a 3-year prospective

left anterior lesions were associated with significantly higher mean study by Astrom and colleagues ~Astrom et al., 1993! found that

left anterior lesion location was associated with depression only in

the acute phase of the stroke, not during follow-up evaluations

Portions of the present data sets were presented at the 1994 and 1995 conducted up to 3 years post-stroke. Rather, depression during

annual meetings of the Society for Psychophysiological Research. follow-up evaluations was associated with lack of social contacts,

This work was supported in part by grant 1 R21 RR09492-01 from the

National Institutes of Health, a grant from the McDonnell-Pew Program in implicating both lesion location and state-related factors in the

Cognitive Neuroscience, and by a fellowship from the Robert S. Flinn experience of depression among stroke victims. Thus it appears

foundation. that the relationship between lesion location and depression may

We thank Sabrina Hitt, Robin Gislason, Tracy Kuo, and Ori Parnaby for not be as straightforward as once hypothesized. In addition to

their assistance and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Address reprint requests to: John J.B. Allen, Ph.D., Department of

situational influences, several factors have been identified that

Psychology, University of Arizona, P.O. Box 210068, Tucson, AZ 85721- confound the interpretation of current studies, including subject

0068, USA. E-mail: jallen@u.arizona.edu. selection, measurement of depression, and definition of lesion lo-

389390 S.A. Reid, L.M. Duke, and J.J.B. Allen

cation ~see House, Dennis, Warlow, Hawton, & Molyneux, 1990, cortex may become hyperactive during brief states of sadness,

for a brief discussion!. possibly entailing depressive rumination, but that the same region

may become hypoactive during prolonged or severe cases of clin-

Neuroimaging Studies ical depression. A similar argument was presented by George,

Consistent with early findings in stroke patients, studies using Ketter, and Post ~1993! in a review of studies.

neuroimaging techniques have also revealed an apparent hemi- Still other functional imaging studies have produced null find-

spheric specialization for the experience of emotion. For example, ings or findings of bilateral decreases in CBF, both of which pose

several functional imaging studies documented findings of left challenges to current conceptualizations of the role of the frontal

frontal hypometabolism in depression. A study utilizing fluoro- lobes in emotion. George and colleagues reviewed three PET stud-

deoxyglucose ~FDG! positron emission tomography ~PET! imag- ies ~Austin, Dougall, Ross, & Murray, 1992, in George et al., 1993;

ing, a measure of cerebral metabolism, found relatively reduced Mayberg et al., 1991; Sackheim et al., 1990!, which all reported an

glucose metabolism in the left prefrontal cortex in depressed in- association with depression and relative decreases in frontal and

dividuals compared with that among controls ~Baxter et al., 1989!. temporal lobe CBF bilaterally. Utilizing PET with injection of

Although severity of depression was correlated with the left frontal @ 18 F# FDG, another study of unipolar depressed and unmedicated

hypometabolism prior to treatment, left hypometabolism was no individuals showed lesser metabolism in dorsolateral frontal areas

longer observed following remission of symptoms. Utilizing an- bilaterally, along with relatively greater metabolism in orbitofron-

other form of PET imaging ~ 15 O!, Bench et al. ~1992! discovered tal regions ~Biver et al., 1994!. In contrast, no differences in levels

reduced cerebral blood flow ~CBF! in the left anterior cingulate of CBF were reported in two studies comparing depressed patients

and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of depressed patients, com- and normal control subjects, one utilizing SPECT with the marker

pared with age-matched controls. In a subsequent review of the Tc-99m-HMPAO ~Maes et al., 1993!, and one using the xenon-133

same population ~Bench, Friston, Brown, Frackowiak, & Dolan, inhalation technique ~Silfverskiold & Risberg, 1989!.

1993!, factor analysis of patients’ symptom ratings revealed two In sum, each of the studies evaluated glucose metabolism, ei-

relevant factors: ~a! a factor with high loadings for depressed mood ther by PET or SPECT imaging, and conducted statistical com-

and psychomotor retardation that was negatively correlated with parisons of activity in each hemisphere for depressed compared

CBF in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and left angular gy- with nondepressed persons. Review of the resulting data provides

rus, and ~b! a factor associated with anxiety that was positively some support for the involvement of the frontal lobes in emotion

correlated with CBF in the posterior cingulate region bilaterally suggested by early studies with neurological patients. However, as

and in the inferior parietal lobes. with data from stroke patients, contradictory and null results con-

Single photon emission computed tomography ~SPECT! stud- tinue to complicate theoretical inferences concerning the relation-

ies have also supported the finding of asymmetrical hemispheric ship of brain activation to emotional processes.

activity in depression. Ebert, Feistel, and Barocka ~1991! studied

melancholic patients using Tc-99m-hexamethylpropylenamineoxime Theories of Hemispheric Specialization and Temperament

~HMPAO! SPECT before and after sleep deprivation. Results sug- Based on the findings of an association between emotion states and

gested that left anterolateral prefrontal brain regions of the de- cerebral activation, an approach-withdrawal theory of hemispheric

pressed patients were hypoperfused relative to controls in both specialization has been proposed. Kinsbourne ~1978! hypothesized

conditions. In an investigation of the activity of serotonergic re- that the left hemisphere may be specialized for approach behav-

ceptors in depressed and control patients using 2- 123 I-ketanserin iors, potentially involving positive mood, whereas the right hemi-

SPECT technology ~D’haenen et al., 1992!, right inferofrontal brain sphere may mediate withdrawal behaviors and more negative mood.

regions were found to utilize relatively more of the tracer com- In an elaboration upon Kinsbourne’s hypothesis, Depue and Iacono

pared with the homologous region in the left hemisphere only ~1989! proposed the notion of a behavioral facilitation system

among depressed individuals. ~BFS!, which is hypothesized to underlie goal-oriented behavior

Despite these promising data, seemingly contradictory findings and the movement toward rewarding stimuli. Similarly, Gray ~1994!

were also produced. Drevets et al. ~1992! measured differences in has described behavioral activation and inhibition systems be-

PET CBF, using H2 15 O injections, in currently depressed and re- lieved to be related to the experience of approach- and avoidance-

mitted participants with familial pure depressive disease ~FPDD!. related behaviors, and Fowles ~1988! has made explicit the link

Comparison of currently depressed and remitted depressive indi- between deficits in approach-related behaviors and particular symp-

viduals revealed that only the currently depressed group demon- toms in depression.

strated relatively greater left prefrontal metabolism, leading the This notion of hemispheric specialization for a system mediat-

investigators to conclude that “this abnormality represents a state ing approach–withdrawal behaviors has been supported by research

marker of FPDD” ~Drevets et al., 1992, p. 3628!. Although the focused on differences in hemispheric electroencephalographic

prefrontal difference compared with controls was significant only ~EEG! activity among individuals with symptoms of depression

in the currently depressed group, both current and remitted depres- ~cf., Davidson, 1992, 1993!, and more directly by examining the

sive subjects showed greater metabolism in the left amygdala, relationship between self-reported behavioral activation ~as mea-

leading to speculation that relatively increased left amygdaloid sured by the scale of Carver & White, 1994! and resting frontal

metabolism may be a trait marker of FPDD ~Drevets et al., 1992!. EEG asymmetry ~Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1997; Sutton & David-

Despite its findings of greater left than right prefrontal metabolism, son, 1997!. A primary hypothesis has been that, in depressed ver-

the study by Drevets and colleagues ~1992! did replicate the as- sus nondepressed individuals, decreased relative activation ~i.e.,

sociation between severity of depression and left frontal hypo- increased alpha band @approximately 8–13 Hz# activity! should be

metabolism, for Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores were observed in the left frontal region compared with the right frontal

negatively correlated with left prefrontal activity ~r 5 2.619, df 5 region during baseline resting conditions. In contrast with func-

11, p , .05!. Formulating an hypothesis to reconcile the seemingly tional imaging studies cited above, which assessed group differ-

contradictory data, these authors postulated that the left frontal ences using between-group t test comparisons of activity ~indexedFrontal EEG asymmetry and depression 391

by glucose metabolism! in a given region, current convention in Studies of individuals diagnosed with past major depression

EEG methodology is to conduct comparisons based on group dif- provide additional support for the argument that the asymmetry

ferences in activity at homologous left and right hemisphere sites associated with depression is stable regardless of current clinical

in each individual. This procedure reflects the theoretical emphasis state. One study measured hemispheric activation in previously

on the complementary functioning of the left and right hemi- depressed compared with never-depressed persons ~Henriques &

spheres in approach and withdrawal behaviors. A paucity of ap- Davidson, 1990! and found that previously depressed individuals,

proach, or an excess of withdrawal, behaviors is believed to be currently asymptomatic, had diminished left anterior activation

associated with a relative decrease in left compared with right compared with the never-depressed group. These findings were

hemisphere EEG activity in a given individual, rather than with an replicated in a treatment study of individuals with seasonal affec-

absolute level of decreased EEG activity across individuals. tive disorder ~SAD; Allen, Iacono, Depue, & Arbisi, 1993!; results

Several EEG studies have provided support for the hypoth- indicated that despite the relief of behavioral symptoms following

esized relationship between cerebral activation and emotion. For phototherapy treatment, anterior activation in individuals with SAD

example, the predicted association between decreased relative left differed from controls both when symptomatic and when in remis-

frontal activation and elevated scores on a self-report measure of sion. In a recent study assessing group differences in baseline

depression was observed in an early study with college students frontal EEG activation ~Gotlib, Ranganath, & Rosenfeld, in press!,

~Schaffer, Davidson, & Saron, 1983!. Studies with clinically de- individuals clinically diagnosed with either current depression or

pressed participants ~e.g., Henriques & Davidson, 1991! further with a history of a past major depressive episode had relatively less

bolstered these findings of a relationship between relatively de- left frontal activation than controls. In fact, these findings reflected

creased left frontal activation and depression. Resting anterior asym- relative hemispheric symmetry among the previously and currently

metry has also been used as an indicator of scores on self-report depressed groups, compared with relative left hyperactivation ev-

scales of emotion in research by Tomarken and colleagues ~e.g., idenced by the never-depressed group.

Tomarken, Davidson, Wheeler, & Doss, 1992!. In this study, base- In addition to some promising reports, there are apparent in-

line EEG measures were used to predict individual differences in consistencies regarding cerebral activation and depression in re-

basic dimensions of emotion at two different testing sessions, as search utilizing EEG methodology. For example, in one review of

measured by the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule ~PANAS; eight studies comparing EEG differences among depressed and

Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988!. The findings that relative left nondepressed participants ~Pollock & Schneider, 1990!, three stud-

anterior activation predicted higher general positive affect scores ies reported no between-group differences, whereas one described

and decreased general negative affect scores on the PANAS pro- decreased alpha power ~i.e., increased activation! in depressed

vided evidence of a relationship between current depressive affect individuals relative to controls. In addition to inconsistencies re-

and measures of anterior asymmetry. garding baseline EEG in depressed individuals, there have been

In addition to studies of baseline EEG activity, the importance reports of a failure to find hemisphere-specific activation in response

of frontal activation in response to emotion-eliciting conditions has to an affect-induction paradigm. For instance, one group of re-

been assessed. In response to internally generated images, a rela- searchers ~Hagemann, Naumann, Becker, Maier & Bartussek, this

tive increase in left hemisphere activation has been correlated with issue! collected baseline EEG data and then presented emotionally

positive affect, whereas negative affect has been associated with significant slides to participants; they reported that baseline hemi-

comparatively greater right hemisphere activation ~e.g., Ahern & spheric asymmetries ~at mid-frontal, anterior temporal, and central

Schwartz, 1985!. Several studies have also been conducted using sites! failed to predict affective responsivity. As with data from

externally imposed affective stimuli with both adults and children. stroke patients and from neuroimaging studies, these findings from

For example, adults’ facial expressions of disgust and happiness in EEG research emphasize the need for closer examination of the

response to film clips have been correlated with greater frontal complex relationship between hemispheric activation and emotion.

activation in the right and left hemispheres respectively ~Davidson, Despite some inconsistencies, the findings of both trait- and

Ekman, Saron, Senulis, & Friesen, 1990!. Furthermore, individual state-dependent differences in EEG asymmetry have been inte-

differences in left frontal activation have been reported to predict grated into a diathesis-stress hypothesis that anterior asymmetry

affective responses to film clips in the absence of baseline differ- reflects a diathesis for depression ~Davidson, 1993!. In the case of

ences in reported emotion ~e.g., Tomarken et al., 1988; Tomarken, EEG asymmetry and negative affect, this model proposes that

Davidson, & Henriques, 1990; Wheeler, Davidson, Tomarken, & relatively less left than right frontal activation ~indicated by dif-

Kinney, 1993!. These findings provided support for the notion that ferences in alpha activity! would be correlated with a biological

resting anterior asymmetry—depending on its direction—might predisposition to patterns of emotional reactivity characterized by

index a trait-related predisposition to respond with either negative negative affect. This model would explain why under stressful

or positive affect irrespective of current mood. conditions certain individuals ~those who have a biological pre-

Davidson and Fox ~1982! demonstrated consistent findings with disposition! develop symptoms of depression, while others may

infants, who viewed film clips of an actress with either a sad or not. This model would also elucidate why the presence of anterior

happy facial expression; the authors concluded that hemispheric asymmetry in individuals without behavioral expressions of de-

asymmetries for emotion seem to be established by 10 months of pression predicts responses to stimuli intended to elicit positive or

age. Baseline anterior asymmetry has also been demonstrated to negative responses. Presumably those individuals with relatively

predict infants’ responses to other emotion-eliciting conditions, less left frontal activation are at risk for depression; this risk may

such as sucrose administration ~Fox & Davidson, 1986! and sep- be reflected in their heightened responses to negative elicitors,

aration from their mothers ~Davidson & Fox, 1989!. These corre- compared with individuals ostensibly not at risk. Also consistent

lations existed despite a lack of differences in behavioral measures with the notion that resting frontal asymmetry taps a disposition to

of the infants’ emotional state at baseline, again suggesting that respond to emotional events in a particular way is the finding that

anterior asymmetry may be a state-independent marker of a pro- resting frontal asymmetry is relatively stable. Asymmetry values

pensity to respond with either positive or negative affect. were found to be stable in unselected college students across an392 S.A. Reid, L.M. Duke, and J.J.B. Allen

interval of up to 3 weeks ~Tomarken, Davidson, Wheeler, & Kin- The first part was comprised of completing the BDI, the Chap-

ney, 1992! and in depressed patients undergoing treatment and man Handedness scale, and a self-report questionnaire regarding

evidencing behavioral indications of treatment response over a 4 medical history. Persons with any of the following conditions were

month period ~Hitt, Allen, & Duke, 1995!. excluded from the study: pregnancy; alcohol or substance abuse in

the past 3 months; previous head injury; learning disability; sei-

zures, stroke, or other CNS disease; or any endocrinopathy not

The Present Studies

stabilized by medication. Those whose scores on the BDI and

Given the hypothesized role of diminished left frontal activity as a

Handedness questionnaires from the original screening and the

psychophysiological marker of increased liability for depression

follow-up screening consistently met criteria for inclusion were

~e.g., Davidson, 1992; Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1997; Henriques &

invited to continue with the psychophysiology portion of the study.

Davidson, 1990!, the present two studies were undertaken in an

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

attempt to replicate and extend the findings of decreased relative

left frontal activation in depressed mood. In Study 1, we attempted

to replicate the findings reported by Schaffer et al. ~1983! of a Study 2. For the second of the two studies, 14 nondepressed

relationship between depression and frontal asymmetry among a female control participants were recruited and were carefully

sample of college students with subclinical levels of depression. To matched to 13 depressed female participants on the basis of age

enhance the methodological strength of the study in comparison ~62 years! and phase of menstrual cycle during testing ~premens-

with the Schaffer et al. study, we used a greater sample size ~n 5 trual, menstrual, or postmenstrual!. Individuals were recruited from

17 depressed, 19 nondepressed! and analyzed the data using three several ongoing investigations. First, they were drawn from a pool

reference schemes ~Cz reference, average reference, and off-line of depressed individuals participating in one of several psycho-

computer-linked mastoids reference!. Study 2 was similarly de- pharmacology trials in the Department of Psychiatry at the Uni-

signed to address the hypothesized relationship between relatively versity of Arizona. The remaining women participated in one of

lower left frontal activation and depression with data from three two studies conducted in the Psychophysiology Laboratory in the

reference schemes, but utilized a sample of individuals from the Department of Psychology: ~a! an acupuncture treatment study for

general population who were determined via structured clinical depression ~Allen, Schnyer, & Hitt, in press! or ~b! a separate

interviews to be clinically depressed. We hypothesized that re- psychophysiological study of depression and cognition ~Duke, 1996!.

duced relative left frontal activation would be found among indi- Informed consent was obtained from each individual for both

viduals evidencing a range of depressed affect. the interview screening and the psychophysiological portion of the

study. To qualify for participation in the psychophysiological por-

tion of the study, individuals were first interviewed with the struc-

Methods tured clinical interview for the DSM-III-R ~SCID-III-R; Spitzer,

Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1990! by a trained clinical research

Participants nurse or by a trained clinical psychology graduate student, to en-

Study 1. For the first study, data were acquired from 36 right- sure they met the DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria for current major

handed female participants. Individuals were preselected from the depression ~American Psychiatric Association, 1987!. In ongoing

Introductory Psychology subject pool at the University of Arizona research across several studies, these raters obtained SCID-III-R

based on scores on the Beck Depression Inventory ~BDI; Beck, inter-rater and intra-rater reliabilities of ricc 5 .90 and ricc 5 .88,

Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961! and on a self-report respectively. As with Study 1, potential participants whose self-

Handedness questionnaire ~Chapman & Chapman, 1987!. Women report revealed any of the following conditions were excluded

who were extremely right-handed ~Handedness scale range 5 36– from the study: pregnancy; alcohol or substance abuse in the past

39! and whose BDI score was either in the nondepressed range 3 months; previous head injury; learning disability; seizures, stroke,

~BDI , 6; n 5 19! or in the depressed range ~BDI . 15; n 5 17! or other CNS disease; or any endocrinopathy not stabilized by

were invited via telephone to participate in a two-part study in medication. In addition, depressed persons were required to have

partial fulfillment of requirements for their Introductory Psychol- been free of psychotropic medication for at least 2 weeks. Descrip-

ogy course. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. tive statistics for participants in Study 2 are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Subject Characteristics

Age Handedness

n ~years! ~SD! BDI ~SD! a score b ~SD!

Study 1

D 17 17.94 ~.24! 23.41 ~6.42! 38.29 ~1.05!

ND 19 19.11 ~1.15! 1.0 ~1.67! 38.68 ~0.58!

Study 2

D 13 27.46 ~8.13! 23.77 ~4.90! 38.00 ~1.41!

ND 14 27.62 ~7.45! 1.54 ~4.48! 38.29 ~1.44!

Note: D 5 depressed; ND 5 nondepressed.

a

Beck Depression Inventory ~BDI! questionnaires for Study 2 were completed within 1 week of EEG data

collection and were available for 13 of the 14 nondepressed individuals. b Handedness scores range from 13

~completely left-handed! to 39 ~completely right-handed!.Frontal EEG asymmetry and depression 393

Data Collection further analyses. There were no significant group differences in the

All EEG evaluations were completed in the Psychophysiology number of artifact-free epochs in either Study 1, depressed 5

Laboratory in the University of Arizona Department of Psychol- 487.9 6 216.4, nondepressed 5 505.9 6 176.5, F~1,36! 5 0.08, ns,

ogy, using identical participant preparation and recording meth- or Study 2, depressed 5 494.9 6 174.6, nondepressed 5 391.8 6

odology. The total time commitment for each participant was 162.1, F~1,25! 5 2.53, p . .12.

approximately 3 hr. First, self-report data were collected. For both Each participant’s data were then re-referenced off-line. In the

Study 1 and Study 2, self-report data consisted of the following: asymmetry literature, three reference schemes have been examined

a medical history and medication information questionnaire, Hand- to some degree and each has produced at least some positive

edness ~Chapman & Chapman, 1987! and Footedness ~based on results ~e.g., Davidson et al., 1990!, despite their conceptual dif-

Chapman, Chapman, & Allen, 1987! Questionnaires, Positive and ferences. A common procedure involves referencing the data to the

Negative Affect Scale—General and Short forms ~PANAS; Wat- vertex ~Cz!. The second entails re-referencing to an average of the

son et al., 1988!, Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology ~IDS; recordings at the two mastoid sites ~hereafter referred to as computer-

Rush, 1987!, and BDI ~Beck et al., 1961!. For Study 2 only, a linked mastoids, or CLM!, and the final reference scheme is based

Modified Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression ~Hamilton, 1967; on a comparison of data at each site with an average of the activity

Williams, 1988! interview was conducted with each participant at all sites across the scalp ~average reference!.

following completion of the self-report data. The interview was Each reference scheme may have strengths and weaknesses

audiotaped, and a subset of the interviews was scored by another depending on the hypothesis of interest. Bipolar placements, of

trained member of a Hamilton Depression Interview scoring group which the Cz-referenced data are an example, produce power val-

for the purposes of obtaining data on interrater reliability. Inter- ues for a given site ~e.g., F3! that represent the difference between

rater reliability for the Hamilton total score for a random sample of activity at that site and activity at the active reference ~i.e., Cz!.

22 interviews conducted in the Psychophysiology Laboratory was When bipolar placements involve closely spaced leads, they can be

.96. Median reliability for individual interviews, analyzed symptom- very sensitive to localized changes, as the differential amplifiers

by-symptom, was .85. reject activity in common between the sites. Because the rejected

Next, in both studies, each person was fitted with a stretch- common activity will likely be generated from distal locations, the

lycra EEG cap ~Electrocap! containing tin electrodes placed ac- observed difference in EEG activity between the sites is likely to

cording to the International 10-20 System. Participants were fitted reflect underlying activity localized to the region near the electrode

with three free tin electrodes to monitor eye movements, placed on placement. For the sites of interest in studies of frontal EEG asym-

the nasion and directly below the pupil of each eye at a position metry, however, the Cz-reference scheme involves two active leads

equal to 20% of the nasion–inion distance. Impedances at all sites that are a considerable distance from one another. Thus, although

were required to be less than 5 kV. Signals were recorded from 27 theoretically this reference scheme will be sensitive to localized

sites ~Fz, Cz, Pz, Oz, FP1, FP2, F3, F4, F7, F8, C3, C4, P3, P4, T3, activity, observed EEG activity may reflect other sources of activ-

T4, T5, T6, O1, O2, A2, FTC1, FTC2, TCP1, TCP2, PO1, PO2! ity as well. Moreover, as activity in the reference site Cz changes,

distributed across the head, in addition to the three sites monitoring observed activity at individual sites can change greatly, which could

eye movements ~nasion, left inferior orbit, right inferior orbit!. All also result in unpredictable effects on observed asymmetry scores.

EEG sites were referenced to A1 online and were recorded with The CLM reference theoretically reflects activity at a given site

AC differential amplifiers ~bandpass 0.1–100 Hz!. Frontalis elec- ~e.g., F3! compared with a composite of relatively electrically

tromyographic ~EMG! activity was recorded via a bipolar arrange- inactive sites ~i.e., A1 and A2!. This reference scheme is therefore

ment, with free tin electrodes placed on the right and left frontalis thought to provide an index of the absolute level of activity at a

muscles referenced to the frontal-pole EEG sites ~FP1 and FP2!. given active lead. Finally, the Average reference scheme reflects

Data were digitized continuously at 512 Hz. the electrical activity unique to each site relative to an average of

After being fitted with the EEG cap, individuals completed a the overall level of activity across all sites. If the activity across

PANAS—short form ~Watson et al., 1988!, and then were seated all the sites is relatively unrelated, and the number of sites is

in a sound-dampened chamber. This room contained a reclining relatively large, then the Average reference will approximate an

chair, video computer monitor, and speakers to provide an audio inactive reference. If, by contrast, there is substantial synchronicity

link to the experimenters. Participants were then instructed to re- between the active leads, then the Average reference will show

cline comfortably in the chair, while the overhead lights were considerable activity. Published research to date has failed to iden-

dimmed ~leaving one 25-W bulb for illumination!. Resting EEG tify clear superiority of any of these three reference schemes for

was then recorded, consisting of eight 60-s blocks of eyes-open assessing the relationship between depression and frontal EEG

~O! and eyes-closed ~C! conditions, in one of two counterbalanced activity. Therefore, analyses for the present studies were conducted

orders ~OCCOCOOC or COOCOCCO!. Following the baseline using data derived from all three Cz, CLM, and Average montages,

EEG recording condition, always the initial procedure in the pro- and analyzed separately for each reference scheme

tocol, several other tasks were administered in each study. Data Upon completion of these preparatory steps, each 1-min EEG

from these tasks will not be discussed in the present report. epoch was divided into 119 2-s epochs that overlapped by 1.5 s.

The fast Fourier transform ~FF T! method was used to calculate the

Analysis of Data power spectra; data were tapered at the distal 10% of each 2-s

Data were collected with the on-line reference of A1 and were epoch using a Hamming window. The power spectra from these

re-referenced off-line. Following the collection of data, each file 2-s epochs were then averaged for each minute of recording, and

was visually screened for epochs with movement and muscle arti- weighted averages ~weighted by the number of epochs! for “eyes

facts, which were removed from further analyses. Subsequently, a open” and “eyes closed” portions of the baseline condition were

computer-based blink rejection technique was used, whereby any created. Total power within five frequency bands was obtained:

epoch with activity evidencing an amplitude greater than 650 mV delta ~1– 4 Hz!, theta ~4–8 Hz!, alpha ~8–13 Hz!, beta ~13–20 Hz!,

~the prototypic minimum amplitude of blinks! was removed from and gamma ~38– 44 Hz!.394 S.A. Reid, L.M. Duke, and J.J.B. Allen

For each of the analyses computed in the two studies, power Table 2. Study 1 Reliability Estimates

values in each band were natural log transformed for all sites, and

asymmetry values were computed for homologous sites. Consis- Mid-frontal Lateral-frontal Parietal

tent with recommendations by Davidson et al. ~1990!, a log trans-

Delta

formation technique was used to normalize the distributions of the CLM .76 .84 .92

power values, which tend to be positively skewed. Both log10 and Cz .72 .90 .92

loge ~i.e., natural log! result in normalized distributions; log trans- Average .79 .82 .94

formations for the present studies were calculated using natural log Theta

CLM .91 .92 .90

~ln!. In research assessing hemispheric differences, two techniques Cz .79 .91 .90

have been used to compare activity at homologous sites. Some Average .87 .79 .90

studies report comparisons of EEG activity using individual left Alpha

and right sites ~e.g., Henriques & Davidson, 1990!, whereas others CLM .92 .93 .82

have described analyses based on an asymmetry score computed Cz .80 .87 .74

Average .80 .87 .74

for homologous right and left sites ~e.g., Tomarken et al., 1990!. Beta

Henriques and Davidson ~1991! reported significant group differ- CLM .83 .92 .92

ences both when testing single sites with hemisphere as a factor, Cz .92 .82 .88

and when using asymmetry metrics from homologous sites. These Average .86 .86 .90

Gamma

findings would be expected, as inclusion of hemisphere as a factor CLM .84 .87 .94

in between-group analyses is comparable to the a priori calculation Cz .93 .84 .98

of asymmetry differences based on homologous sites. Whereas a Average .89 .87 .96

between-group analysis also tests for overall ~i.e., between group!

power differences, both techniques can examine right–left group

differences after removing variations in overall activation levels.

For the present study, measures of EEG hemispheric asymmetry

~right hemisphere compared with left hemisphere! using the for-

mula @ln~right! 2 ln~left!# were calculated. Sites of interest for ln@left#! for each 1-min segment as a separate item on an eight-

initial hypothesis testing included F30F4, F70F8, and P30P4. Log- item scale. Using this method, 8 min of resting EEG activity pro-

transformed asymmetry values were also calculated for the ante- duced internal consistency reliability estimates that ranged from

rior temporal sites ~i.e., T3, T4! to conduct post hoc analyses based .74 to .93 in the alpha band, depending on the reference scheme

on one anonymous reviewer’s recommendations. and the particular scalp region ~see Table 2!.

Comparison of Asymmetry Between Depressed

Results and Nondepressed Participants

Previous studies involving measures of frontal asymmetry have Results from the alpha band will be presented first, with results

found effects at mid-frontal ~F30F4! and lateral-frontal ~F70F8! from other bands following. As mentioned earlier, resting data was

sites, when compared with parietal sites ~P30P4!. Data derived collected in a series of eight 1-min contiguous segments, during

from parietal sites have demonstrated either no effects ~e.g., Hen- which participants were asked to remain in a relaxed state with

riques & Davidson, 1991; Schaffer et al., 1983!, or effects reflect- eyes either open or closed. Before testing the hypothesis that rest-

ing decreased right compared to left parietal activation in depressed ing asymmetry—collapsed across all 8 min—differed between de-

compared to non-depressed individuals ~e.g., Henriques & David- pressed and nondepressed individuals, comparisons of asymmetry

son, 1990!. Following the presentation of reliability estimates of scores from 4 min each of eyes open and eyes closed data were

asymmetry scores for each reference scheme, between-group com- computed to determine whether this factor ~eyes! significantly in-

parisons of asymmetry scores ~ln@right# 2 ln@left#! in these three teracted with the factors of interest. For those bands in which there

regions will be reported. In a 2 ~Group! 3 3 ~Site! ANOVA using were no significant interactions with the eyes condition, a weighted

asymmetry scores as a repeated measures dependent variable, the average of all 8 min was computed and subsequently used in

predicted Group 3 Site interaction would indicate a different pat- analyses of the hypothesis that the groups differed in their patterns

tern of resting asymmetry in depressed and nondepressed individ- of resting asymmetry.

uals. A significant main effect for group would indicate a difference

in asymmetry across the entire head, an effect that was not pre- Alpha band. A 2 ~group! 3 2 ~eyes! 3 3 ~site: mid-frontal,

dicted. When significant interactions were obtained involving re- lateral-frontal, parietal! repeated measures analysis of variance ~AN-

peated measures factors with more than two levels, p values were OVA! revealed that the eyes factor did not interact significantly

corrected using the Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon correction proce- with group or, more importantly, with the Group 3 Site interaction

dure; in these cases, the original degrees of freedom are presented, in any of the three reference schemes, all Fs~1,34! , 0.50 for the

along with the corrected p value and the epsilon value. Significant Group 3 Eyes interaction; all Fs~2,68! , .26 for the Group 3

effects were further analyzed via post hoc comparisons using the Eyes 3 Site interaction. Therefore, data were collapsed across the

Student Newman–Keuls procedure. eyes open and eyes closed conditions and a 2 ~group! 3 3 ~site:

mid-frontal, lateral-frontal, parietal! repeated measures ANOVA

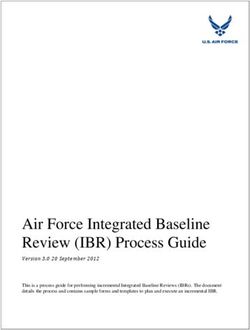

was computed. Figure 1 presents asymmetry scores for each group,

Study 1

for each of the three scalp regions, as determined using each of the

Reliability Estimates three reference schemes.

Internal consistency reliability estimates ~Chronbach’s Alpha! were For the CLM-referenced data, no significant Group 3 Site

obtained for Study 1 by treating the asymmetry score ~ln@right# 2 interaction emerged, F~2,68! 5 .97, ns. Similarly, there was noFrontal EEG asymmetry and depression 395

for the beta, delta, or theta band in any of the three reference

schemes, all Fs~1,34! , 3.19 for the Group 3 Eyes interaction;

all Fs~2,68! , 1.58 for the Group 3 Eyes 3 Site interaction.

Therefore, data were collapsed across the eyes-open and eyes-

closed conditions and a 2 ~group! 3 3 ~site: mid-frontal, lateral-

frontal, parietal! repeated measures ANOVA was computed. Again,

there were no significant Group 3 Site interactions in the CLM-

referenced data, all Fs~2,68! , .45, ns, the Cz-referenced data,

all Fs~2,72! , 1.58, ns, or the average-referenced data, all

Fs~2,72! , .55, ns.

A Group 3 Eyes interaction approaching significance was un-

covered in the gamma band when ANOVAs were computed with

Cz-referenced, F~1,34! 5 4.09, p 5 .05, and average-referenced

data, F~1,34! 5 3.17, p 5 .08, but not with the CLM-reference,

F~1,34! 5 1.02, ns. However, there were no significant Group 3

Eyes 3 Site interactions in any of the reference schemes in the

gamma band, all Fs~2,68! , 1.02, ns. Collapsing across eyes open

and closed conditions, the weighted average data produced signif-

icant group main effects under both the CLM and average-reference

schemes, both Fs~1,34! $ 4.63, ps , .05, but not the Cz-reference

scheme. This group main effect indicated that across the three

scalp regions, nondepressed individuals had greater relative right

gamma band activity ~M 6 SD 5 .12 6 .20 for CLM-referenced;

Figure 1. Mean ~6SE!a asymmetry scores ~ln@right# 2 ln@left#! in Study

1 for mid-frontal ~F3_F4!, lateral-frontal ~F7_F8!, and parietal regions .15 6 .22 for Average-referenced!, whereas depressed individuals

~P3_P4!, under three reference schemes. Open bars indicate depressed had relatively greater left Gamma band activity ~2.05 6 .23 for

subjects, hatched bars indicate nondepressed subjects. Depressed and non- CLM-referenced; 2.04 6 .30 for average-referenced!. The Group 3

depressed subjects did not differ significantly in any region, under any Site interactions, however, were not significant under any refer-

reference scheme. ence scheme, all Fs~2,68! # .85, ns.

Post hoc analyses. Based on a few reports of significant find-

ings using data from anterior temporal sites ~e.g., Tomarken, Da-

significant Group 3 Site interaction for either the Cz-referenced vidson, Wheeler, & Doss, 1992!, post hoc analyses were conducted

data, F~2,68! 5 1.97, ns, or the average-referenced data, F~2,68! 5 using data from each of the three reference schemes comparing

2.08, ns. The correlation between asymmetry scores obtained un- activity in the anterior temporal region ~i.e., T3, T4! with activity

der different reference schemes varied from 20.33 to 0.87. Table 3 at parietal sites. Because a priori hypotheses focused on alpha band

presents these correlations. activity, only data from this band were utilized in these post hoc

analyses.

Other bands. Although our a priori hypotheses did not predict A 2 ~group! 3 2 ~Eyes! 3 3 ~site: parietal, anterior-temporal!

any significant between-group differences in the delta, theta, beta, repeated measures ANOVA revealed that the eyes condition did not

or gamma bands of activity, we conducted the primary analyses interact significantly with group or, more importantly, with the

with data from these bands as well. The data were first examined Group 3 Site interaction for any of the three reference schemes,

to determine whether the Eyes factor interacted the other factors of all Fs~1,34! , .28, ns for the Group 3 Eyes interaction; all

interest; when it did not, the weighted average of all 8 min of Fs~2,68! , .67, ns for the Group 3 Eyes 3 Site interaction. There-

resting data was analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA model. fore, data were collapsed across the eyes-open and eyes-closed

As was the case with the alpha band, a 2 ~group! 3 2 ~eyes! 3 3 conditions, and a 2 ~group! 3 3 ~site! repeated measures ANOVA

~site: mid-frontal, lateral-frontal, parietal! repeated measures AN- was computed. Again, there were no significant Group 3 Site

OVA revealed that the eyes condition did not interact significantly interactions in the CLM-referenced data, F~2,68! 5 1.49, ns, the

with group or, more importantly, with the Group 3 Site interaction Cz-referenced data, F~2,72! 5 .32, ns, or in the average-referenced

Table 3. Study 1 Correlations Between Reference Schemes

Alpha band Beta band Theta band Delta band Gamma band

Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz

F3F4 2.30 .84* .07 .54* .83* .88* 2.10 .94* .14 2.01 .84* .35* .81* .91* .96*

F7F8 2.33* .61* .30 .61* .93* .83* 2.52* .49* .38* 2.22 .49* .69* .97* .99* .98*

P3P4 .48* .86* .82* .30 .78* .79* .57* .89* .82* .79* .96* .89* .56* .86* .75*

Note: n 5 36.

*p , .05. Values represent the correlation between the asymmetry score for a given pair of electrodes under two different reference schemes.396 S.A. Reid, L.M. Duke, and J.J.B. Allen

data, F~2,72! , .92, ns. Reliability coefficients for data at the Comparison of Asymmetry Between Depressed

temporal sites ranged from .77 to .83. and Nondepressed Participants

To summarize the results from Study 1, contrary to a priori Results from the alpha band are presented first, with results from

hypotheses based on research outlined earlier in the present mono- other bands following. Before testing the hypothesis that resting

graph, the anticipated Group 3 Site interaction was not found in asymmetry—collapsed across all 8 min—differed between de-

the alpha band. Analyses of other bands ~beta, delta, theta, gamma! pressed and nondepressed individuals, asymmetry scores from data

also resulted in nonsignificant Group 3 Site interactions. Hence, gathered with eyes open and eyes closed were analyzed to deter-

these data did not provide support for the hypothesis of an asso- mine whether this factor ~eyes! significantly interacted with the

ciation between depressed affect and the expected pattern of rel- factors of interest. When it did not, the weighted average of all

atively less left than right resting frontal cerebral activation. 8 min was analyzed as the test of the hypothesis that the groups

Similarly, in Study 1 there was no evidence of differences in pa- differed in their pattern of resting asymmetry, which would be

rietal activation between depressed and nondepressed subjects. indicated by a significant Group 3 Site interaction.

Alpha band. A 2 ~group! 3 2 ~eyes! 3 3 ~site: mid-frontal,

Study 2

lateral-frontal, parietal! repeated measures ANOVA revealed that

Given the fact that symptoms experienced by the individuals with the eyes factor did not interact significantly with group or, more

high BDI scores utilized in Study 1 may have been indicative of importantly, with the Group 3 Site interaction in any of the three

subclinical levels of depression in some members of the group, we reference schemes, all Fs~1,25! , 0.73 for the Group 3 Eyes

hypothesized that the subtle effect of group differences in frontal interaction; all Fs~2,50! , 1.15 for the Group 3 Eyes 3 Site

asymmetry might more likely be uncovered in comparisons using interaction. Figure 2 presents asymmetry scores from each group,

clinically depressed participants. Study 2 was undertaken to ad- for the three scalp regions, under each of the three reference schemes.

dress this hypothesis; results are presented as in Study 1, with Collapsing across eyes open and closed conditions, for the

reliability estimates preceding the test of the hypotheses that fron- CLM-referenced data, the predicted Group 3 Site interaction,

tal asymmetry differs between depressed and nondepressed par- F~2,50! 5 4.12, p 5 .05, E 5 0.68, was due entirely to a difference

ticipants. in parietal asymmetry between the groups ~ p , .02!. Data from

depressed individuals revealed approximate symmetry, whereas

Reliability Estimates data from controls revealed relatively greater right hemispheric

Table 4 presents the reliability estimates of asymmetry scores activation ~decreased alpha power!. The groups did not differ at

~ln@right# 2 ln@left#! computed from spectral data analyzed using mid-frontal or lateral-frontal sites. Using the average-referenced

the three different reference schemes: CLM, Cz, and Average ref- data, a significant Group 3 Site interaction, F~2,50! 5 3.60, p ,

erence. As can be seen in Table 4, internal consistency reliability

estimates from 8 min of resting EEG activity ranged from .73 to

.88 in the alpha band, depending on the reference scheme and the

particular scalp region. Asymmetry scores for the beta and gamma

bands appeared the most reliable, with internal consistency relia-

bilities ranging from .89 to .98. Overall, these analyses indicated

that the asymmetry scores were measured reliably across all bands

and scalp regions.

Table 4. Study 2 Reliability Estimates

Mid-frontal Lateral-frontal Parietal

Delta

CLM .80 .79 .95

Cz .85 .80 .91

Average .86 .84 .67

Theta

CLM .88 .81 .93

Cz .75 .73 .91

Average .85 .75 .90

Alpha

CLM .87 .85 .78

Cz .83 .73 .88

Average .88 .83 .83

Beta

CLM .95 .90 .94

Cz .93 .91 .94

Average .96 .91 .90 Figure 2. Mean ~6SE !a asymmetry scores ~ln@right# 2 ln@left#! in Study

Gamma 2 for mid-frontal ~F3_F4!, lateral-frontal ~F7_F8!, and parietal regions

CLM .96 .93 .89

~P3_P4!, under three reference schemes. Open bars indicate depressed

Cz .94 .93 .98

Average .96 .93 .92 subjects, hatched bars indicate nondepressed subjects. *Depressed and non-

depressed subjects differed significantly ~ p , .05! by Student Newman–

Keuls procedure.Frontal EEG asymmetry and depression 397

.05, E 5 0.63, emerged in the absence of significant differences at interaction was present in the average-referenced data, F~2,46! 5

any scalp region between depressed and nondepressed participants 2.83, p , .07. The Group 3 Site interaction was not significant in

in the post hoc tests. However, the pattern of activation was similar the CZ-referenced data, F~2,44! 5 0.1, ns. Reliability of alpha

to that observed with the CLM data. No significant Group 3 Site band activity for the first 2 min of CLM-referenced data was

interaction, F~2,48! , 1, ns, emerged for the Cz-referenced data. estimated at .49 ~at F30F4!, .66 ~at F70F8!, and .61 ~at P30P4!.

The correlation between asymmetry scores obtained under differ- To explore the discrepancy between the analyses involving

ent reference schemes varied from near 0 to .86 for the alpha band. 8 min of resting data versus this analysis involving only the first

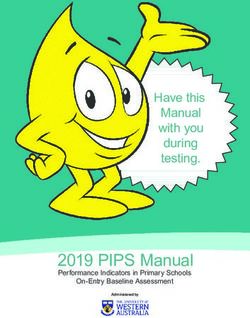

Table 5 presents these correlations for all bands. 2 min of data, we examined group patterns of asymmetry over time

at the lateral frontal sites for the CLM-reference only, where the

Other bands. As described above, resting asymmetry data were effect was strongest. A 2 ~group! 3 2 ~eyes! 3 4 ~time! ANOVA

first examined to determine whether the eyes factor interacted with revealed a Group 3 Time interaction, F~3,66! 5 2.78, p , .05, E 5

the other factors of interest; when it did not, the weighted average 0.89. Post hoc tests of the interaction indicated that the predicted

of all 8 min of resting data was analyzed using a repeated measures difference in resting asymmetry scores between the two groups,

ANOVA model. For the bands beta, gamma, and theta, the eyes with the depressed group showing increased left frontal alpha, was

factor did not interact significantly with either group or with the apparent only in the first 2-min segment of data. This pattern of

Group 3 Site interaction in any of the three reference schemes, for results during the first 2 min reached significance only at lateral-

the Group 3 Eyes interaction, all Fs~1,25! , 1.82, ns; for the frontal sites ~F70F8!, although a similar pattern was observed at

Group 3 Eyes 3 Site, all Fs~2,50! , 0.69, ns. In addition, exam- F30F4, F~3,66! 5 2.45, p , .08!. Figure 3 shows the resting alpha

ination of the weighted average resting data collapsed across the asymmetry scores at these lateral-frontal sites, divided into 2-min

eyes factor revealed that the Group 3 Site interactions for these segments, for the CLM-referenced data.

bands ~beta, gamma, theta! in all three reference schemes were not

significant, all Fs~2,50! , 0.91, ns. Further post hoc analyses. Further exploratory analyses in the

For the delta band, the eyes factor interacted significantly with alpha band only were conducted, comparing activity in the anterior

group in the average-referenced scheme, F~1,25! 5 5.08, p , .04, temporal sites ~i.e., T3, T4! with the activity in parietal locations,

but not in the Cz or CLM schemes, Fs~1,25! , 3.46, ns. However, for each of the three reference schemes. A 2 ~group! 3 2 ~eyes! 3

the Group 3 Eyes 3 Site interactions did not reach significance 2 ~site: parietal, anterior-temporal! repeated measures ANOVA in-

using any of the reference schemes, Fs~2,50! , 1.64, ns. Exam- dicated that, under each of the three reference schemes, the eyes

ination of the weighted average data in the delta band similarly condition did not interact significantly with group or with the

revealed no significant Group 3 Site interactions, Fs~2,50! , Group 3 Site interaction; all Fs~1,25! , .41 for the Group 3 Eyes

1.13, ns. interactions; all Fs~1,25! , .2.91 for the Group 3 Eyes 3 Site

interactions. Therefore, collapsing across the eyes-open and eyes-

Examination of the first minutes of resting data. Because the closed conditions, a 2 ~group! 3 2 ~site! repeated measures AN-

three previous studies using clinical samples ~Allen et al., 1993; OVA was performed. A significant Group 3 Site interaction emerged

Henriques & Davidson, 1990, 1991! used short recording periods in the CLM-referenced data, F~1,25! 5 6.78, p , .02, and there

~30 s or 1 min!, we examined data from the first 2 min ~1 min of was a similar trend in the average-referenced data, F~1,25! 5 4.22,

eyes closed data, 1 min of eyes open! of the 8-min recording pe- p , .06!. Examination of the means revealed that these inter-

riod to determine whether any differences in asymmetry were pres- actions were in the predicted direction, with the controls’ temporal

ent at the beginning of the recording period, but not consistently alpha activity being near symmetry ~CLM-reference: M 6 SD 5

throughout the 8 min. For these analyses, only the alpha band was .014 6 .249; average-reference: M 6 SD 5 .054 6 .304! and with

examined. the depressed individuals evidencing increased left temporal alpha

In our analyses of only the first 2 min of data, the predicted activity ~CLM-reference: M 6 SD 5 2.150 6 .283; average-

Group 3 Site interaction emerged in the CLM-referenced data, reference: M 6 SD 5 2.127 6 .316!. However, post hoc mean

F~2,46! 5 4.93, p , .04, E 5 0.68. Post hoc testing indicated that comparisons using the Student Newman–Keuls procedure revealed

the interaction was due to group differences in asymmetry in the that these differences between groups failed to reach significance

predicted direction at the lateral frontal sites. Group differences at for either reference scheme. For the Cz-referenced data, no signif-

the mid-frontal and parietal sites were also in the predicted direc- icant Group 3 Site interaction, F~1,24! 5 .82, ns, was found.

tion, but were not significant in this post hoc analysis. In addition, Reliability coefficients for data at the temporal sites ranged from

although it did not reach significance, a similar Group 3 Site .83 to .89.

Table 5. Study 2 Correlations Between Reference Schemes

Alpha band Beta band Theta band Delta band Gamma band

Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz Cz-LM AR-LM AR-Cz

F3F4 .25 .86* .45* .80* .95* .91* .11 .95* .31 .48* .90* .76* .95* .96* .99*

F7F8 .01 .69* .57* .87* .93* .95* .34 .75* .81* .61* .85* .92* .98* .99* .98*

P3P4 .19 .68* .77* 2.11 .56* .70* 2.39* .74* .24 2.66* .58* .15 .46* .78* .85*

Note: n 5 26.

*p , .05 . Values represent the correlation between the asymmetry score for a given pair of electrodes under two different reference schemes.398 S.A. Reid, L.M. Duke, and J.J.B. Allen

results reported in previous studies ~e.g., Henriques & Davidson,

1990; Schaffer et al., 1983!. Although interpretation of these find-

ings in the absence of the expected relationship between depres-

sion and frontal activation should be made with caution, the data

are consistent with theories regarding the role of parietal regions in

emotion. In her review of published data, Heller ~1993! noted that

several studies reported an association between decreased right

parietal activation and lower levels of arousal, a behavioral symp-

tom of depression. It could be suggested, therefore, that depressed

participants in Study 2 may have been experiencing relatively

decreased levels of general arousal. Although consistent with pub-

lished literature to date, further confirmatory evidence regarding

the potential role of the right parietal region in the experience of

emotion is required.

Third, post hoc analyses with data from Study 2 uncovered two

additional significant findings. Examination of only the first 2 min

of baseline data resulted in significant group differences in the

predicted direction in the lateral frontal sites. Specifically, de-

pressed individuals evidenced a pattern of relatively greater left

than right alpha activity compared with nondepressed participants.

Finally, post hoc analyses of group differences in anterior tem-

poral activation revealed a similar pattern of increased left hemi-

spheric alpha activity in the depressed participants, whereas right

and left temporal activation neared symmetry among the nonde-

Figure 3. Mean ~6SE ! asymmetry scores ~ln@right# 2 ln@left#! in Study 2, pressed individuals. However, Student Newman–Keuls post hoc

separated into 2-min recording periods, for the lateral-frontal ~F7_F8!

comparisons of group means failed to indicate significant group

region under the computer-linked reference scheme. Squares indicate de-

differences.

pressed subjects, triangles indicate nondepressed subjects. *Depressed and

nondepressed subjects differed significantly ~ p , .05! by Student Newman– In the following sections, we discuss variables that may, in part,

Keuls procedure. Note: because one period for some subjects contained too account for the different pattern of findings in the present studies

few epochs, these data represent 12 depressed and 12 nondepressed subjects. compared with others in the published literature.

Severity of Depression

One potential reason for the nonsignificant findings in Study 1

Discussion could be that participants may not have been experiencing a major

depressive episode. Although participants were classified as either

Data from two different samples of depressed individuals failed to “depressed” or “nondepressed,” this distinction was based on scores

replicate findings from previous studies of relative increased left on the BDI, which was not designed to serve as a diagnostic tool.

frontal alpha activity in depression ~e.g., Allen et al., 1993; Hen- Participants in the depressed group endorsed symptoms suggesting

riques & Davidson, 1990, 1991; Schaffer et al., 1983!. The absence a wide range of distress levels ~low score 5 16; high score 5 39!;

of group differences in alpha band activity for the 8-min baseline it is unclear if they would have met DSM-III-R criteria for depres-

condition was consistent across three different reference montages, sion had a structured interview been conducted. To test the hy-

at both mid-frontal and lateral-frontal sites. These results are sur- pothesis that the anterior asymmetry would only have been apparent

prising, given the growing body of literature suggesting a relation- in individuals reporting greater levels of distress, correlations be-

ship between frontal EEG asymmetries and emotion. To ensure tween depressed individuals’ BDI scores and mid-frontal asymme-

that inadequate power was not the cause of these findings, power try power values from each reference scheme were computed. The

analyses were conducted using Cohen’s f as the estimate of effect nonsignificant correlations ~all rs , _.24_, ns! indicated that frontal

size. Based on effect sizes seen in previous studies, power to detect asymmetry was not related to the severity of depression in this

a significant Group 3 Site interaction was greater than .90 for both sample.

of the present studies, suggesting that lack of power was likely not Although asymmetry was not related to severity of depressive

a factor in the observed absence of significant findings. symptomatology, it is possible that severity of depression must

Despite the lack of replication of frontal alpha asymmetry in reach a certain threshold before a relationship with anterior asym-

depression, four significant findings emerged from the present metry would be apparent. This possibility was evaluated in

studies. First, analyses from Study 1 revealed significant between- Study 2. The depressed participants in this study were assessed

group hemispheric differences in gamma band activity; unfortu- using the SCID and necessarily received a diagnosis of current

nately, the absence of significant effects in data from other bands, major depression before they were included in the study. None-

and the lack of a priori theory regarding data in this band limit theless, the predicted effect of increased relative left frontal alpha

possible interpretations of this finding. power across the 8 min of baseline data in the individuals with

Second, data from Study 2 only revealed significant group depression did not emerge in Study 2.

differences in alpha activity in parietal regions in the absence of

differences in frontal activation. Although not originally included Methodological Issues

as an a priori hypothesis due to inconsistencies in published data EEG reliability. Although the issue of clinical severity was ad-

related to this region, the findings at the parietal sites did replicate dressed via Study 2, several other study-related factors, includingYou can also read