Race and the Race for the White House On Social Research in the Age of Trump - OSF

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Race and the Race for the White House

On Social Research in the Age of Trump

Musa al-Gharbi1

______________________________________________________

Abstract: As it became clear that Donald Trump had a real base of political support, even as analysts

consistently underestimated his electoral prospects, they grew increasingly fascinated with the question of

who was supporting him (and why). However, researchers also tend to hold strong negative opinions about

Trump. Consequently, they have approached this research with uncharitable priors about the kind of person

who would support him and what they would be motivated by. Research design and data analysis often

seem to be oriented towards reinforcing those assumptions. This essay highlights the epistemological

consequences of these tendencies through a series of case studies featuring prominent and influential works

that purport to explain the role of race and racism in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. It demonstrates

that quality control systems, which should catch major errors, seem to be failing in systematic ways as a

result of shared priors and commitments between authors, reviewers and editors – which are also held in

common with the journalists and scholars citing and amplifying this work – leading to misinformation

cascades. Of course, motivated reasoning, confirmation bias, prejudicial study design, and failure to address

confounds are not limited to questions about Trump – however they seem to be particularly pronounced in

this case due to the relative homogeneity and intensity of scholars’ views about this topic as compared to

other social phenomena. “Trump studies,” therefore, provides fertile ground for exploring how social

research can go awry – and the consequences of these failures -- particularly with respect to work on

contentious and politically-charged topics.

Suggested citation: al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social

Research in the Age of Trump.” The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

1Paul F. Lazarsfeld Fellow in Sociology, Columbia University

Website: mussaalgharbi.com

Email: musaalgharbi@gmail.comSome degree of bias is inevitable in social research. We are all shaped by our limited experience, our

personal commitments and aspirations, etc. – and these inform social inquiry in obvious and subtle ways

(Polanyi 1974). However, in a context where people with diverse and competing commitments,

backgrounds and experiences are simultaneously exploring a particular issue, these errors should approach

random distribution -- they would largely cancel each-other out. “Zones of agreement” should emerge in

the process, forming a basis for reliable knowledge (Shi et al. 2019). However, in a world where everyone

shares the same basic commitments, errors are not randomly distributed. They are far less likely to be

recognized as errors and addressed at all – indeed, they are likely to cascade as an integral part of the

“consensus” position, even giving rise to entire “null fields” of research (Ioannidis 2005).

Among social researchers, one commitment which virtually everyone seems to share is a passionate

distaste for Donald Trump, his agenda, and what he seems to represent. As it became clear that Trump was

a real contender for the Republican nomination, even as analysts consistently underestimated his prospects

-- both in the primary and the general election – researchers became transfixed by questions of just who

was supporting him and why (Samuelsohn 2016). These questions are perfectly reasonable and legitimate.

The problem is that, as a result of their disgust with Donald Trump, many social researchers also seem to

have developed strong assumptions about the type of person who would support him, and what they would

be motivated by. These presuppositions have consistently undermined research about the President and his

base. The most typical problems include:

• Failure to deal with obvious confounds

• Prejudicial study design

• Strange interpretations of data (apparently to make them fit with researchers’ preferred theses)

• Uncharitable interpretations of the words and actions of Trump and (especially) his supporters1 –

or even outright misrepresentation through cherry-picking and editing (Alexander 2016).

Here, we will present a series of case studies exploring prominent examples of this phenomenon -

- particularly as it relates to the role of race (and racism) in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. On this

point, an overwhelming consensus seems to have emerged that Trump voters were motivated largely (or

even primarily) by anti-minority or white-supremacist sentiments. It will be demonstrated that the evidence

scholars marshal in the service of these propositions is often weak, and abundant countervailing evidence

to the consensus position has been chronically under-addressed, while alternative explanations for Trump’s

victory have been insufficiently explored – despite apparently resting on surer empirical footing.

The works discussed in the following pages will be by scholars I respect and even admire. Indeed,

many are central to their respective fields. This is part of the point: the problem is not a matter of a couple

bad apples or fringe scholars – it cuts to the heart of who we are and what we do as social researchers. The

fact that the sort of errors described in the following pages could be made by people who obviously know

better – with the resultant works endorsed by so many others who also know better -- strongly suggests

motivated reasoning and confirmation bias are undermining the quality of our scholarship and the rigor of

our critiques (Koehler 1993, Mahoney 1977). Indeed, research has shown that the more important an issue

is perceived to be, the greater the risk that even grievous errors can go unnoticed or unaddressed (Wilson

et al. 1993). However, the election of Donald Trump is not just an ‘important issue’ -- for many of us, and

for many reasons, it is an outright crisis. However, this makes it all the more important to be clear-eyed

and level-headed about how we got here.

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 1THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS

“The problem of knowledge is that there are many more books on birds written by ornithologists than books on birds

written by birds and books on ornithologists written by birds.” (Taleb 2010a, 108)

A key theme in the sociology of knowledge literature is that, contrary to idealized narratives of science as

a dispassionate enterprise in search of objective truths, science is in fact deeply political on several levels.

At the grand scale, ideological and cultural commitments inform who counts as trusted authorities and in

virtue of what, standards of appropriate evidence for a claim, the appropriate scope and most pressing

questions within a field of study, and even the structure of logical argumentation itself (al-Gharbi 2016a).

Expertise and scientific consensus are established within a field, and presented to outsiders, through

political processes internal to the discipline. At every stage in these processes there are power struggles

between rival coalitions (Latour 1988), as well as with experts in adjacent fields (e.g. economists, political

scientists, sociologists all aiming to shape policy on a particular issue, or competing for the same funding

opportunities, etc.). Throughout, there is a parallel negotiation between the expert class and the politicians

and publics they are supposed to advise and inform (Abbott 1988).

Yet another dimension of political contention is added for social scientific endeavors, because

unlike in the case of most material sciences, the objects of study in social research fields (i.e. people) have

agency. They have their own perspectives, interests, values, priorities and agendas which often diverge

sharply from those of researchers (Meadow 2013). Recent scholarship has held that not only should these

differences be recognized, ‘insider expertise’ should be privileged (Merton 1972). For instance, LGTBQ

people are understood as having some kind of special knowledge or authority on queer issues, women on

gender issues, racial and ethnic minorities (especially blacks) on race issues, Arabs and Muslims on the

Middle East and terrorism, etc. 2 This notion has undergirded much of the drive for diversity in social

research fields.

Curiously, despite the fact that there is far less political diversity in social research fields than there

is diversity in terms of gender, sexuality or even race (al-Gharbi 2018), the political positionality of scholars

seems to rarely be considered as important or problematic. While scholars are obliged to concede that there

is no superior race, class, gender, sexuality, or religion (except perhaps no religion),3 they are largely free

to take for granted that their own political and ethical commitments are correct, and that those who diverge

from them are both factually and morally ‘in the wrong.’ Indeed, while increased levels of education

correspond to reduced levels of racial and ethnic bigotry, they also correlate with significantly higher levels

of ideological prejudice (Henry & Napier 2017).4

This political blind spot could be problematic for any discipline. However, it has particularly strong

distortionary effects on the social sciences, because the subject of our fields is roughly identical to the

content of politics: sorting out how society is best arranged. The discipline of sociology was established in

the United States as a handmaid to the progressive reform movement (Abbott 2016, p. 49-50), and to this

day there remains a strong element of activism undergirding American sociology and most other social

research: scholars don’t want to merely understand social problems, but to help address them as well (Smith

2014).5 As a result of social researchers’ widespread certainty about the rightness of their political

convictions (Abbott 2018), and the desire to leverage our research and expertise to intervene in socio-

political disputes, it can be easy to temporarily lose sight of how complex, ambiguous and uncertain the

phenomena we study are.6 Consider:

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 2Even in “hard” disciplines such as physics, most experiments do not yield the expected result and

replications frequently fail (Lehrer 2009). As we approach fields like biomedical research, the replication

problem becomes far more severe – indeed, a majority of research efforts in these fields may be wasted by

avoidable errors and poor experimental design (Munafo et al. 2017). Yet, despite our best attempts to

emulate the material sciences (e.g. Levinovitz 2016), social research has not been able to demonstrate a

comparable level of reliability and power as these other fields (Horgan 2013). Indeed, there is far less

consensus on even foundational issues (Dunleavy, Bastow & Tinkler 2014). The effect-sizes of most

phenomena we study will be small almost by necessity (Gelman 2017), and it is likely that even many of

these effects will ultimately prove to be false-positives (Engber 2017). In other words, social researchers

should be cautious in making strong causal claims and skeptical when they encounter them from others.

Hence, there is a powerful a priori case for doubting deterministic narratives about the role of race

and racism in the 2016 general election. This served as the point of departure for the case studies that follow.

CASE STUDIES

Co-occurrence searches on Google Scholar7 can help highlight the scale of the phenomenon this essay seeks

to address. Restricting our analysis to 2016 and beyond, pairing “Donald Trump” with “racism” yields more

than 19.7k articles published in journals, books, or cited in academic work (Google Scholar). Searching

“Donald Trump” and “white supremacy” yields 5.9k results (Google Scholar) –“Donald Trump” and

“xenophobia” nets 6.6k (Google Scholar); “Donald Trump” and “ethnic nationalism” brings in 651 results

(Google Scholar). Even assuming some overlap between these, it is clear that an extensive literature has

emerged analyzing the relationship between Trump and racism, culled from a wide array of fields, and

produced in a relatively short amount of time (especially given how long it takes to publish academic

research, the lag time until works show up in Google Scholar after publication, and the restrictiveness of

the search criteria).

Having worked through the first ten pages of results for each of these (ten results per page), the

titles, descriptions and abstracts of these works suggest that many scholars take it more-or-less for granted

that Trump and his supporters are racist. A large number – even among those published in prominent

journals – seem to have an explicitly partisan and activist orientation. None of the hundreds of works

personally surveyed seemed to challenge prevailing narratives about Trump, his supporters, and their

alleged racism. This essay drills into a sample from this literature and addresses its major themes – focused

on works that have had demonstrably large impact both within the academy and beyond:

I. Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The First White President,” The Atlantic, October 2017.

It may seem strange to lead with Ta-Nehisi Coates in an article discussing problems with social research.

One anticipates a reply that runs basically, “so what if Ta-Nehisi’s research isn’t rigorous by the standards

of social science? That’s not his job. He’s a public intellectual, not an academic.” However, Coates’ work

greatly influences the academy, and informs a good deal of research in the humanities and social sciences.

Consider:

Studies suggest that a majority of journal articles are likely never read by anyone other than their

editors and authors (Eveleth 2014). 82% of articles in the humanities -- and roughly a third of all articles

published in the social sciences -- are never cited, even once (Remler 2014).

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 3These numbers, as bad as they seem, would actually look dramatically worse if self-citations were excluded

from consideration (Shema 2012). In contrast with this dismal state of affairs for most social research,

Coates’ work is widely cited in academic literature (Google Scholar). His memoir, Between the World and

Me, is among the most frequently-assigned common readings for incoming freshmen at universities

nationwide (Randall 2017), and his work is assigned as required reading for courses across a wide range of

disciplines (Google). He regularly participates on panels and delivers keynote addresses at universities, and

served as a visiting scholar at MIT from 2012 through 2014 (Smith 2017). He recently signed a three-year

contract to teach journalism courses at New York University – placing him in a pedagogical position at one

of the top-ranked journalism programs in the nation (Roy & Siu 2017), and at one of the most prestigious

universities in the world (Times Higher Education, 2017). In short, Ta-Nehisi Coates has already been far

more successful and influential in the academy than most ‘real’ academics could plausibly aspire to be over

the course of their careers.

Coates’ essay (2017b), “The First White President,” is far more likely to be read and cited by

academics – and to inform academic thinking on these issues – than most other instances of scholarship

that could be produced from the professional literature. It has already been cited at least 123 times (Google

Scholar) and was liked or shared more than 575.8k times on Facebook.8 Finally, Coates’ essay is highly-

representative of a swath of academic literature that’s out there – for instance, his central thesis is roughly

the same as that of Emory sociologist Carol Anderson’s (2017) book, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of

our Racial Divide.9

Coates argues that while many pundits have pinned the election outcome on the ‘white working

class’ (e.g. Cohn 2016),10 this is an overly-narrow reading of the race. In fact, he asserts, Trump decisively

won among virtually all whites – cutting across income, gender, education, and geographic lines.11 From

there, Coates essentially imputes causation from correlation: (i)Trump repeatedly made racially/ culturally

inflammatory remarks; (ii) Trump won the white vote; (iii) Therefore, Trump won the white vote because

of his appeals to white supremacy. In his telling, white Americans rose up in 2016 to dismantle the legacy

of America’s first black president, Barack Obama (Coates 2017a) — and to reclaim what is rightfully

‘theirs.’ Trump was elected primarily because of racial resentment, and he maintains his hold on power by

playing to Americans’ latent sympathies with white supremacy. Despite the popularity of this thesis, it

suffers from several serious problems:

First, many of the white voters who proved most decisive for Trump’s victory actually voted for

Obama in both 2008 and 2012 (Uhrmacher, Schaul & Keating 2016). Indeed, according to one Democratic

political firm, the Global Strategy Group, these defections explain more than 70% of why Clinton lost

(Roarty 2017).12 If the white voters who ostensibly decided the 2016 election were horrified at the very

prospect of a black president, it is unclear why they would have supported Barack Obama’s initial

campaign. Similarly, if they were committed to undermining and dismantling the legacy of the first black

president, it is not clear why they would have voted to give him four years to further entrench his agenda

rather than simply voting for Mitt Romney in 2012. Apparently, instead of resisting Barack Obama in 2008

or 2012, they chose to act on their racial grievances years later, in a race between two white people. Coates

et al. portray the 2016 election as being fundamentally ‘about’ Barack Obama and what he allegedly

represents, rather than the (un)desirability of Hillary Clinton and/or Donald Trump. Yet in the lead-up to

the election, Obama was far more popular than both Clinton and Trump – indeed, he grew more popular

over the course of the 2016 cycle, even as the appeal of his would-be successors plummeted (Tesler 2016).13

All of this seems inconsistent with the notion that the election was an uprising against Barack Obama – as

a symbol or a politician.14

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 4Second, Trump did not mobilize or energize whites towards the ballot box (Mellnik et al. 2017).

Their participation rate was roughly equivalent to 2012 – and lower than in 2008. In fact, whites actually

made up a smaller share of the electorate than they had in previous cycles, while Hispanics, Asians and

racial “others” comprised larger shares than they did in 2012 or 2008. This seems inconsistent with the

thesis that Trump spearheaded an ethnic nationalist uprising.

Even if we overlook Obama’s continued popularity and whites’ tepid participation, at the very least

the ‘white supremacy’ thesis would seem to entail Trump winning a larger share of those whites who did

turn out to vote. In fact, Trump won a smaller share of the white vote than Mitt Romney did in 2012 (al-

Gharbi 2017b).15 However, he outperformed his predecessor with Hispanics and Asians, and won the

largest share of the black vote of any Republican since 2004. Given Trump’s lower share among whites, it

was likely these gains (and Democrats’ attrition) among people of color that put Trump in the White House.

Coates et al. therefore seem committed to arguing that the millions of these blacks, Latinos and Asians who

voted for Trump were also primarily or exclusively motivated by ‘white rage’ or their commitment to white

supremacy – or else conceding that it is possible to vote for Trump for other reasons (and of course, if this

is true of minorities, it stands to reason what whites could be similarly motivated by other factors).

Now, there might be some way to make the ‘white supremacy’ / ‘white rage’ argument work while

accounting for these apparent confounds – but this is not something that most proponents are doing.

Although the hypothesis is intended to explain voting behavior (i.e. why Trump won), researchers largely

ignore most of the critical data about who actually voted, and for whom. They run regressions testing

correlations between various demographic characteristics and political attitudes in pre-election surveys, but

fail to check if and how the resultant picture lines up with the available information on how people actually

voted. In those too-rare instances where researchers acknowledge apparent confounds for claims about

Trump voters’ alleged racism, the most common tactic is to say something along these lines:

“The explanation that Trump’s victory wasn’t an expression of support for racism because he got

fewer votes than Romney, or because Clinton failed to generate sufficient Democratic enthusiasm,

ignores the fact that Trump was a viable—even victorious—candidate while running racist

primary- and general-election campaigns. Had his racism been disqualifying, his candidacy would

have died in the primaries (Serwer 2017).”

There are three big problems with this line of thought:

First, there is a demographic confound. Again, Trump not only garnered stagnant turnout and a

smaller vote-share among whites relative to Mitt Romney – he was nonetheless able to win because he also

received a larger share among Asians and Hispanics (who did turn out in higher numbers), not to mention

African Americans. Should we assume that Asians, Latinos and blacks were also motivated primarily by

racism simply because they did not find Trump’s rhetoric (about China, Mexicans and Muslims)

disqualifying? This is an implication of the argument.

Second, it is just a logical error to assert that because Trump’s ‘racist’ rhetoric was not

disqualifying, Trump voters therefore supported him primarily due to his racial appeals. As Van Jones

aptly points out (Martinez 2017), Trump supporters regularly and forcefully rejected or expressed disquiet

with many of his racialized statements or policy proposals, but voted for him nonetheless because there

were other parts of his platform they found it essential to support, or because he was just viewed as the

least-worst option relative to Hillary Clinton. We can underscore this point with the help of a simple

“turnabout test” (Tetlock 1994):

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 5Hillary Clinton has a long record of foreign policy hawkishness – even surpassing most of the

Republican primary candidates in the 2016 election cycle (al-Gharbi 2015a). Her Democratic National

Convention was noted for its emphasis on patriotism, supporting the troops, confronting America’s

enemies, etc. to a point where many pundits observed that it actually seemed like a Republican event (e.g.

Gaouette 2016). Many prominent neoconservatives outright endorsed Clinton as the best candidate in either

party to promote their agenda (Norton 2016). Clinton actively sought out the endorsement of controversial

figures like Henry Kissinger and repeatedly bragged about their support on the campaign trail and in debates

(Grandin 2016).16 During the primaries, she relied on the same foreign policy consulting firm as hawkish

Republican candidates Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz (Fang 2015). Her general-election national security

advisory team was drawn heavily from people who oversaw some of the greatest excesses of the George

W. Bush administrations (Jilani, Emmons & LaChance 2016). Should we assert that because Clinton’s

well-established record of hawkishness was not disqualifying, that her supporters must have voted for her

because they, themselves, are hawks? Or to be less charitable: did most Democratic voters support Clinton

because they actively endorse the killing, traumatization and immiseration of others abroad (mostly people

of color, often of low socio-economic status) in the name of ill-defined ‘U.S. values and interests’? No. For

most Clinton voters this was an aspect of her record they found troubling, perhaps abhorrent, but not

disqualifying.17

Was race a critical factor in the 2016 election? Undoubtedly. But of course, this can be said of

virtually every electoral cycle in American history – including the 2008 and 2012 races which resulted in

the election and re-election of Barack Obama. The specific ways race influences politics are far more

complex and unpredictable than the analyses of Coates and his fellow travelers seem to suggest18 – even

among those who voted for Trump. Indeed, Hillary Clinton herself has a troubled history on racial issues

which many black voters did find disqualifying (al-Gharbi 2016b), perhaps helping to explain the depressed

turnout among this constituency – or even Trump’s gains among blacks (relative to Romney).

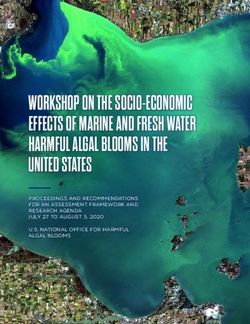

Finally, looking at whites’ stagnant turnout in 2016 and Republicans’ lowered vote share among

whites as compared to 2012 -- it could be that Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric was, on balance, a drag on

his candidacy among white voters, rather than being the key to his electoral success. In order to explore this

possibility, researchers would have to turn their attention away from the motivations of whites who did vote

for Trump, and towards the large majority (63%) of eligible non-Hispanic white voters who did not (Figure

1).

Figure 1

2016 U.S. Presidential Election

Voting Behavior Among Non-Hispanic Whites

Trump

36 37

Clinton

Other

Abstained

24

3

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 6For instance, even if it was assumed that 100% of those whites who voted for Trump were

motivated primarily by racial resentment – a claim which has no empirical basis to be clear – one would

still be unable to make sweeping generalizations about white people on the basis of these votes. Nearly as

many eligible non-Hispanic whites chose to abstain (36%) as those who voted for Trump (37%). This

should raise grave concerns about participation bias in interpreting what the election “means” on the basis

of Trump votes (Groves & Peycheva 2008, Paleologos et al. 2018) – especially given that an additional

27% of non-Hispanic whites explicitly rejected Trump by casting their votes for other candidates (Clinton,

Johnson, Stein, McMullin).

Another turnabout test can help underscore the problems with making sweeping claims on the basis

of such a dubiously representative sample: according to Bureau of Justice statistics, up to a third of all

African American males can expect to be incarcerated at some point in their lives (Bonczar 2003).

On a pie chart, the wedge for “black men expected to ‘do time’” would look very similar to the red area in

Figure 1. Should we assume on this basis that most black men are criminals? Of course not. Nor can we

declare an epidemic of racism among whites because 37% of eligible non-Hispanic white voters cast their

ballots for Trump (again, setting aside the grievous problems with imputing racist motives to those who did

support the Republican candidate simply on the basis of their vote).19

In short, the ‘white supremacy’ thesis not only lacks empirical support, it is confounded by the very

data it seeks to explain. Researchers often attempt to circumvent these realities by conflating (often

begrudging) tolerance for Trump’s racialized remarks and policies with active endorsement of his racial

appeals. Not only is this illogical, it is inconsistent with the way progressives seem to interpret support for

Hillary Clinton given her liabilities. Yet even working from within this model, it would actually be

consistent with the data to assert that most whites did find Trump’s rhetoric disqualifying. The ‘white

supremacy’ thesis therefore fails even if the conflation between tolerance and endorsement were allowed

to stand (although it should not be allowed to stand).

II. Thomas Wood, “Racism motivated Trump voters more than authoritarianism,”

Washington Post, 17 April 2017.

This article was written by an assistant professor of political science (Ohio State) and published in the

Washington Post “Monkey Cage” blog. All articles published on this site are curated and edited, not just

by academic political scientists, but by some of the most prominent scholars in the field (Sides 2013).

Therefore, although this essay was not a peer reviewed journal article, it was, in fact, reviewed by Wood’s

political science peers prior to publication at the Monkey Cage.20 The essay has had a demonstrable

academic impact – cited at least 31 times so far (Google Scholar), including in the American Sociological

Review and the British Journal of Sociology -- among the top journals in the field of sociology. The essay

has had a demonstrable public impact as well, with more than 71.2k shares on Facebook.

Wood seeks to challenge popular narratives about Trump voters being driven to the candidate due

to their support of authoritarianism (e.g. MacWilliams 2016). Utilizing data from the American National

Election Studies (ANES) Time Series Study, he found that Trump voters seem to be less supportive of

authoritarianism than those who voted for Romney or McCain (Figure 2).21

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 7Figure 2 (Wood 2017)

Wood then posits that, given Trump’s repeated use of racially inflammatory language throughout the

primary and general election, racism may better explain why a voter would support Trump over Clinton. In

order to test this hypothesis he developed a “symbolic racism” scale (SRS) and explored how white ANES

respondents’ scores on that scale corresponded to support for the Democratic and Republican presidential

candidates, from 1988 through 2016.

For the moment, we can set the well-known problems with attributing motives to political positions

on the basis of measures like “symbolic racism” scales (e.g. Sniderman & Tetlock 1986). 22

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 8And although both of these claims are contestable, we’ll just grant for the sake of argument that Dr. Wood’s

ANES-derived scales are sufficiently accurate measures of racist and authoritarian tendencies in the voters

sampled, and that his sample is sufficiently representative to allow for sound generalizations about Trump

and Clinton voters on the basis of his study. Figure 3 presents Wood’s visualization of his findings, as

presented in the Washington Post.

Figure 3 (Wood 2017)

One thing readers may immediately notice, which ends up being the centerpiece of his argument, is that the

gap between Democrats and Republicans on his symbolic racism measures was larger in 2016 than it had

been in previous years –

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 9suggesting that race likely played a much bigger role in the most recent election than it had in prior cycles.

This is an interesting finding which we’ll return to momentarily. In the meantime, however, it should be

noted that across all measures the longitudinal trend is roughly the same among supporters of the

Republican and Democratic candidates between 2004 and 2016: endorsement of ‘racist’ attitudes increased

substantially among all voters during the Obama years (2008, 2012) and then dropped among all voters in

this most recent cycle. That is, Wood’s data does not suggest that Trump voters were especially motivated

by racism. Instead, among supporters of both the Democratic and Republican candidates, whites were

actually less likely to endorse symbolically racist attitudes than they were in 2012. In other words, according

to Wood’s own data, whites who voted for Trump are perhaps less racist than those who voted for Romney.

The same holds among whites who voted for Clinton as compared to those who voted for Obama (in either

term).

This is truly a newsworthy and provocative finding about Trump voters: not only were they less

authoritarian than Romney voters, but less racist too! Had the findings been presented this way, Wood’s

report certainly would have served as a springboard for rich discussion and helped to push research on

Trump voters in new and interesting directions. Unfortunately, although his analysis of authoritarianism

focused on variation among Republicans over time, Wood curiously decided to adopt an alternative analysis

with respect to understanding the role of race23 – in particular, focusing on the gap between Democrats and

Republicans in 2016, in the service of a conclusion his data do not support.

Wood asserts, “Since 1988, we’ve never seen such a clear correspondence between vote choice and

racial perceptions.” He goes on to concede that, “The biggest movement was among those who voted for

the Democrat, who were far less likely to agree with attitudes coded as more racially biased.” This is an

understatement: across all measures, Republican voters’ SRS trend was actually towards convergence with

the other party. Change in Democrat-voters’ sentiment drives the entire divergence effect Wood refers

to…in an article that is supposed to explain Trump voters. Statistically speaking, the decline in

authoritarianism was greater than the decline in racism, while the decline in endorsing symbolic racism

among Democrats was larger than the decline among Republicans. So even through there were actually

declines across the board, in a multivariate analysis symbolic racism could be made to seem relatively more

significant for Republicans – if that was the image one was actively trying to convey. It seems bizarre and

incoherent to point to an apparent decline in endorsement of racism among Republicans in 2016 in order to

demonstrate that Trump voters are particularly racist – yet that is precisely what Wood did.

To elaborate: the gap between Democrats and Republicans was caused, not because Trump voters

were more likely to endorse symbolic racism than Republicans in previous cycles (again, the exact opposite

seems true), but instead because Democrats went out of their way to emphasize just how non-racist they

were in 2016 surveys — (ostensibly) rejecting symbolic racism more powerfully than they ever have in the

time 28 years of data presented. In fact, Wood’s data suggest that racist sentiment among Democrats

actually increased in 2008 with Barack Obama on the ballot, and more-or-less held at that higher level in

2012. This renders the unprecedented drop among Democrats in 2016 even more interesting. Indeed, if

Wood wanted to focus on the change in the partisan gap among SRS indicators, given that Democrats are

the ones driving that effect, the article should have been about them. Such a story would not suggest that

Trump voters are especially motivated by racism— again, Wood’s own data confound that claim. Instead,

perhaps Democratic voters were particularly motivated by anti-racism (McWhorter 2015).24 Wood could

have still said something like “moving from the 50th to the 25th percentile in the SRS scale rendered whites

20 percent more likely to vote for Clinton” – only now there wouldn’t be misleading insinuations about

Trump being made in the process.

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 10On the other hand, if Wood really wanted to make the article ‘about’ Trump voters, his results

should have been described in a completely different manner. For instance, the “unprecedented” partisan

divide among SRS indicators should not have been part of the story at all: given that it is entirely the product

of a severe longitudinal aberration among supporters of the Democratic candidate, it isn’t clear what (if

anything) can be inferred about Trump voters from the gap. With regards to the relative significance of

authoritarianism and racism, Wood could have more legitimately asserted that “Trump voters seem to be

more strongly influenced by racism than authoritarianism – although they were less motivated by either of

these factors than Republican voters have been in previous cycles.” This latter part, which Wood omitted,

is actually the significant story in his data on Trump voters (as compared to those who supported previous

Republican candidates).25 Wood should have also been more explicit about how much of the total variance

in voting behavior was explained by the factors he focused on (as reflected in the R2 of his regressions). It

seems likely that a majority of the variance would remain unexplained by his authoritarianism and/or racism

scales.

Following these standard best-practices would have had the added virtue of drawing readers’ minds

to the following question: “if both racism and authoritarianism seemed less appealing to Trump voters than

to previous Republican constituencies – and if these factors don’t explain most of the variance in voting

behavior anyway – is there some other (omitted) variable that may explain Trump voters even better?”26

This is important because, over and above the problems with Wood’s interpretation of his data, there is the

problem that the study design is prejudicial.

In this work, and others in the genre, it seems taken for granted that Trump voters must have been

motivated by some ‘bad’ factor (poverty, ignorance, irrationality, authoritarianism, racism, xenophobia,

sexism, etc.) and the task of social researchers is merely to identify which of these traits best explains the

data.27 Indeed, there is a long history in social research of pathologizing libertarians, conservatives and

populists – essentially describing views that diverge from researchers’ own political preferences as resulting

from ignorance, error or character defects (Duarte et al. 2014). Meanwhile, there is relatively little research

discussing the extent to which Clinton voters were motivated by negative impulses (the same ones or

others). It is implied that, by contrast, they must have been guided primarily by benign traits such as love

for others, patriotism, knowledge of the issues, rational self-interest, etc. (Stanovich 2017).

III. Arlie Hochschild, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the

American Right, September 2016.

Hochschild’s book was published two months prior to the 2016 election, and it is not technically

about that election. However, it is worth examining this work in closing for a few reasons. First, it had a

major impact of how people understood the outcome of the 2016 election. The perceived insight and

prescience of the work as it relates to the election of Donald Trump helped elevate it into being a New York

Times bestseller and National Book Award finalist. These same perceptions likely help explain why it is so

widely assigned as a required reading in course syllabi, in sociology departments and beyond (Google). It

has been cited more than 1.2k times (Google Scholar), often in works about the election. This is likely in

part because Hochschild herself has repeatedly asserted that Strangers in their Own Land robustly explains

Donald Trump’s appeal (Hochschild 2016b). In subsequent peer-reviewed articles she has implored other

social researchers to follow the methods she laid out in Strangers in their Own Land in order to gain further

insight into the “rise of the right” (Hochschild 2016c). Since the election, many social researchers and

journalists have attempted to do just this – flocking to regions Clinton lost, “on safari in Trump’s America”

(Ball 2017), in an attempt to figure out how Democrats can turn things around in 2018 and 2020.

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 11Given that we have so far explored the many ways statistical and historical facts have been distorted

to caricaturize Trump supporters as racist (not to mention ignorant, irrational, misogynistic, etc.),

ethnography may seem like a far more reliable method for understanding Trump voters and their

motivations. Researchers can directly observe the milieu of their subjects. Rather than the simple questions

pollsters rely on, ethnographers can have repeated in-depth conversations with their subjects – and follow

the discussion wherever it leads. Certainly, in many instances ethnographic research can promote key

theoretical insights or provide critical context to quantitative data (Wilson & Chadda 2009). However, there

is little reason to believe that ethnographic methods are, on balance, more reliable than quantitative or

historical approaches for understanding contentious political issues.

Contemporary research suggests that partisanship affects our cognition at a fundamental level –

potentially shaping our memories and evaluations of events, and at times, even coloring sensory perceptions

(Van Bavel & Pereira 2018). These are the very foundations upon which ethnography is built. Indeed, given

the highly subjective nature of the ethnographic encounter, the method may be even more vulnerable to

certain forms of bias, especially when researchers are seeking to understand perceived socio-political rivals,

with the aim of advancing a particular socio-political agenda (Avishai, Gerber & Randles 2013).28 Yet, even

as these commitments systematically distort or obscure critical details of their cases, ethnographers can

gain a strong erroneous conviction that they truly understand ‘the other side’ as a result of the intimate

nature of their research (Martin 2016). Seduced by the power of narrative, both the researcher and their

audience can significantly overestimate the reliability and generalizability of the resultant study (Taleb

2010b). This certainly seems to be the case with Strangers in Their Own Land.

Hochschild conducted forty “core interviews” (Hochschild 2016a, 247-50) -- all with white Tea

Party supporters, concentrated in one narrow region (Lake Charles) of a single state (Louisiana). This is an

extremely small and homogenous sample for explaining why some 63 million people, from all across the

country and all walks of life, cast their ballots for Donald Trump. Indeed, as we have previously explored,

the race was likely decided by people who voted for Obama in the previous election(s) but flipped for

Trump in 2016. Few of these voters would have been staunch Tea Party supporters (they may even have

very negative views about the Tea Party). And again, many of the most critical defections were not from

whites at all. Were it not for Republican gains (and Democratic losses) among blacks, Hispanics and Asians,

Trump likely would have lost -- given that he actually won a smaller share of the white vote than Mitt

Romney. Yet there does not seem to be one single county in the state Hochschild studied that flipped from

Obama to Trump (Figure 4).

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 12Figure 4 (Uhrmacher, Schaul & Keating 2016)

Indeed, by her own reckoning, only about 11% of white Louisiana voters supported Obama in 2012.

In 2011, up to 50% of Louisianans supported the Tea Party. The region is described by Hochschild herself

as the “geopolitical heart of the right” (p. 11-2). Simply put: these votes were not decisive in the 2016

election – there was no real contest for the Louisiana at all. And so, empirically speaking, it is not clear

how Hochschild’s project -- which basically attempts to understand why whites in a solidly-red state vote

Republican – would explain much about why so many former Obama supporters, many of them minorities,

voted for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in 2016. This is perhaps the most substantive question for

understanding why Trump won, and it is not addressed in her book – whatever its other merits. Yet, the

narrative Hochschild weaves is so seductive and compelling (especially for progressives) that questions of

representativeness and generalizability seem to be taken for granted – to include at times by Hochschild

herself – in discussions about the book and its relevance for understanding Trump’s appeal.

Moreover, while Hochschild’s subjects are often highly compelling and insightful when speaking

for and as themselves in the work, her analyses of these accounts frequently seem to suffer from political

bias. Hochschild’s treatment of her subjects is compassionate, but essentially condescending (Lozada

2016). Her main project is to understand the “emotional draw” of right-wing politics (Hochschild 2016a,

247), in part because she seems to take for granted that her subjects’ preferences could not be grounded in

a view of the world that is as logical or informed as that of progressives.29 Indeed, the book is fundamentally

structured around resolving the “great paradox” of why people who should support state programs,

interventions and regulations do not. That is, Hochschild is convinced from the outset that she understands

her subjects’ best-interests better than they, themselves, do. That assuredness never wanes – despite her

frequent criticisms of the ways other progressives demean and disrespect these constituents.

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 13With regards to the core contribution of the book, the ‘deep story’ of why her subjects support the

Tea Party (and Trump), Hochschild seems to put great weight on the fact that her respondents widely

endorsed the general picture she proposes – particularly the sense of frustration and marginalization that

comes through in the narrative. However, the fact that they support the broad picture does not necessarily

entail that they endorse every particular component of that narrative. Indeed, parts of the ‘deep stories’

Hochschild presents to her respondents seem to be intentionally leading. For instance (emphasis added):

“…You’re a compassionate person. But now you’ve been asked to extend your sympathy to all the

people who have cut in line ahead of you. And who’s supervising the line? It’s a black man whose

middle name is Hussein. He’s waving the line cutters on. He’s on their side.

He’s their president, not yours. What’s more, all the many things the federal government does to

help them don’t help you. Should the government really help anyone? Beyond that, from ahead in

line, you hear people calling you insulting names: ‘Crazy redneck!’ ‘White trash!’ ‘Ignorant

southern Bible-thumper!’ You don’t recognize yourself in how others see you.

You are a stranger in your own land. Who recognizes this?” (Hochschild 2016b, 686).

Every component of a “deep story” should be more-or-less essential. Yet evoking Obama’s race

and his middle name seems unnecessary here, an attempt to bait respondents into tacitly endorsing racially

inflammatory language. The implication seems to be that if they do claim to “recognize themselves” in the

general story, then they must have a problem with the specific fact that our president was “a black man,”

and one whose middle name happens to be “Hussein.” Does Hochschild really believe that her respondents

would find the bolded text integral to the story? Would the story have been less likely to resonate with them

if the relevant passage simply read: “…But now you’ve been asked to extend your sympathy to all the

people who have cut in line ahead of you. And the line supervisor seems to be just waving the cutters on.

He’s on their side...”? Would they spontaneously add, “and one more thing, the line supervisor is a negro

with a Muslim name!” This seems unlikely.

Indeed, if the “deep story” is supposed to explain why Louisianans support the right, then

presumably this tale would stretch beyond Barack Obama’s presidency in both temporal directions. The

geopolitical trends that left communities like Lake Charles behind began in the mid- 90’s. The oppositional

attitude towards the institutions, forces and actors perceived to be behind those trends also began to escalate

at this time (Foa 2016). Louisiana didn’t flip to the Republicans because of Obama – it has remained “red”

for every presidential election after 1996. Therefore, highlighting the fact that the “line supervisor” at the

time was a “black man whose middle name is Hussein” seems to substantially undermine the “depth” of

her narrative – reducing a story that has been ongoing for much of her subjects’ lives into something that is

fundamentally ‘about’ Barack Obama and what he allegedly represents. Similarly, Hochschild’s “deep

story” would presumably have remained just as true if Hillary Clinton had won in 2016 – which she almost

did -- therefore it seems strange to impute said “deep story” as explaining Trump’s victory.

At times, Hochschild’s project even seems exploitative: In a break with her groundbreaking

previous work, the goal of Strangers in their Own Land is not so much to understand these people on their

own terms, for their own sake – or to shine a light on the challenges they face, and their needs as they

understand them. Instead, Hochschild’s Tea Party supporting subjects and their stories are used as a means

to political ends -- ones which they would never, themselves, endorse (Ray 2017): Hochschild wants to

stall the “rise of the right”; she wants to help progressives understand how to advance their agenda and

candidates in red states; she wants to neutralize the appeal of Donald Trump.

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 14Hochschild seems to paternalistically believe that securing these political objectives would benefit her

subjects in the end – irrespective of their own preferences. However, this goal seems secondary at best in

reading the book. Although she typically refers to subjects as her “Tea Party friends” -- in the end they do

not seem to be on the same page, and they are not on the same team.

CONCLUSION

“…[T]he tendencies operating in 1948 electoral decisions not only were built up in the New Deal and Fair Deal era but

also dated back to parental and grandparental loyalties, to religious and ethnic cleavages of a past era, and to moribund

sectional and community conflicts. Thus in a very real sense any particular election is a composite of various elections and

various political and social events. People vote for a President on a given November day, but their choice is made not

simply on the basis of what happened in the preceding months or even four years; in 1948 some people were in effect

voting on the internationalism issue of 1940, others on the depression issues of 1932 and some, indeed, on the slavery

issues of 1860.” (Berelson, Lazarsfeld & McPhee 1986, 315-6).

The case studies presented here suggest serious, perhaps endemic, flaws on social research about the 2016

U.S. presidential election. Specifically, although the evidence presented here suggests that the role of race

has been widely overblown and misunderstood with respect to Trump’s victory, social researchers

nonetheless systematically represent Trump voters, and whites more broadly, as white supremacists in

virtue of their (presumed) support for the President. There is a Manichean subtext, with ‘evil’ racists

complicit in a depraved regime, v. the ‘good’ progressives who dutifully voted for Hillary Clinton (Hamid

2016). In the case of Hochschild, we see a variant on this narrative: Trump’s supporters aren’t bad people,

they’re just victims and hapless dupes of the Republican Party and their ‘fascist’ leader. It is easy to see

how these are edifying stories for progressives – which social researchers overwhelmingly are – but these

tendencies are also deeply pernicious in the following ways:

They threaten the viability of our discipline: Social science already faces a public perception

problem. Yet the troubled research discussed here targets the very people who are the most skeptical –

portraying them as racist (and often sexist, irrational and ignorant as well) on flimsy evidentiary grounds.

Yet the people being maligned in this research also happen to control the purse strings for federal research

funding, state funding for education, etc. (al-Gharbi 2017c). Their pundits already argue that social research

is shoddy leftist propaganda, scarcely worth serious engagement or attempted implementation. The works

discussed here provide ‘smoking guns’ to charges of bias. This is a dangerous state of affairs.

Cascade effects and feedback loops: When prominent and respected scholars publish flawed

research, it can pollute understanding of a subject matter in a way that becomes very difficult to correct.

Consider all the emerging scholars who have been assigned Hochschild or Coates’ recent works as a means

for understanding Trump’s election. Consider all of the subsequent research that will invariably reference

and attempt to build on these works, and the impact that this next generation of research will have in turn,

ad infinitum. In other words, the stakes of research about the last election extend well beyond the 2018 or

2020 races – myopic political scholarship can lead astray future activists and scholars in their own quests

to understand and address social problems.

Researchers can also help reify unfortunate social phenomena (Stampnitzky 2013, Watters 2011).

In this instance, unfairly labelling Trump voters as bigots -- simply because they voted for the Republican

in 2016 –

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 15this will likely stir up resentment against those who seem to be promulgating the charge (academics,

journalists and activists – especially minorities). Voters may double-down on their support for Trump, when

they might otherwise defect, simply in order to ‘stick it’ to those disparaging them (al-Gharbi 2015b). They

may even come to believe, on the basis of experts’ ubiquitous racialized narratives, that Trump is the best

candidate to promote white voters’ interests (Gray 2018) – despite whatever problems they may have with

what he has said or done so far. In other words, by demonizing Trump supporters as racist, social researchers

may be laying the groundwork for the very negative externalities they wish to avoid (i.e. Trump’s reelection,

increased resentment against the media, the academy, minorities, etc.).

In fact, one bitter irony of allowing research to be distorted by political aspirations is that the

unreliability of the resultant scholarship can undermine those very aspirations. In this instance, it is critical

for ‘the resistance’ to have an accurate understanding of who voted for Trump and why: inaccurate research

would likely generate ineffective electoral strategies. Indeed, motivated research and confirmation bias

likely explain why most analysts couldn’t see Trump’s strength in the last cycle (al-Gharbi 2017a). If

progressive scholars wish to avoid another humiliating and costly ‘black swan’ defeat for their party in

2020, then we’ll need to begin with a sober reckoning of how he won in the first place -- even if this means

being more charitable towards Trump voters than we feel naturally inclined to be, or being skeptical of

claims that would be very satisfying to accept.

Finally, it is normatively dangerous to countenance problematic research because it edifies our

identities. If scholars are sincerely worried about the way ‘Trumpism’ erodes and debases norms and

institutions we hold dear, we cannot effectively fight these trends by ourselves undermining the

methodological, evidentiary and disciplinary standards of our chosen professions. We should instead try to

defend and embody our values all the more, and to exemplify our best-practices – especially with research

relating to Trump and his supporters.

APPENDIX I:

John Sides, “Race Religion and Immigration in 2016,” Voter Study Group, June 2017.

In September 2017, prior to publication of the original version of this essay, I reached out to the editors of

the Monkey Cage (Washington Post) and expressed my concerns about the glaring problems in Wood’s

piece. They declined to issue a correction or retraction, nor to permit a rejoinder. Moreover, they

emphasized that even if Wood’s essay was flawed, his basic claim (Trump voters were motivated largely

by racism) was nonetheless correct—as evidenced by the wide literature of work in the field which comes

to similar conclusion without suffering the shortcomings I highlighted. To underscore this point they sent

along an essay by Vanderbilt political scientist John Sides (who also happens to be the publisher of the

Monkey Cage). Unfortunately, rather than ameliorating my concerns about the “Trump studies” literature,

the essay serves as yet another prime example of how the enterprise frequently goes awry.

Like Wood and Coates, Sides begins his research from the premise that because Trump repeatedly

used inflammatory language about minority and immigrant groups throughout the campaign, and

subsequently won the lion’s share of the white vote, these whites must have voted for Trump because of

his racialized rhetoric. His study purportedly demonstrates “cultural anxiety” to be the most explanatory

factor in explaining why white Americans voted for Trump over Clinton. 30 The proof offered for this claim

was that Voter Survey Group respondents’ attitudes toward immigration, blacks and Muslims better

predicted whether a participant voted Democrat or Republican in 2016 than they did in 2012. Figure 5

visualizes this data.

al-Gharbi, Musa (2018). “Race and the Race for the White House: On Social Research in the Age of Trump.”

The American Sociologist (49)4: 496-519.

p. 16You can also read