Perceptions of Organizational Change: A Stress and Coping Perspective

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Journal of Applied Psychology Copyright 2006 by the American Psychological Association

2006, Vol. 91, No. 5, 1154 –1162 0021-9010/06/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1154

Perceptions of Organizational Change: A Stress and Coping Perspective

Alannah E. Rafferty Mark A. Griffin

Queensland University of Technology The University of South Wales and The University of Sydney

Few organizational change studies identify the aspects of change that are salient to individuals and that

influence well-being. The authors identified three distinct change characteristics: the frequency, impact

and planning of change. R. S. Lazarus and S. Folkman’s (1984) cognitive phenomenological model of

stress and coping was used to propose ways that these change characteristics influence individuals’

appraisal of the uncertainty associated with change, and, ultimately, job satisfaction and turnover

intentions. Results of a repeated cross-sectional study that collected individuals’ perceptions of change

one month prior to employee attitudes in consecutive years indicated that while the three change

perceptions were moderately to strongly intercorrelated, the change perceptions displayed differential

relationships with outcomes. Discussion focuses on the importance of systematically considering indi-

viduals’ subjective experience of change.

Keywords: organizational change, individual perceptions, appraisal, survey research

Although there are many studies of organizational change, few have investigated specific changes such as job loss resulting from

identify the aspects of change that are salient to individuals and downsizing (Gowan, Riordan, & Gatewood, 1999), mergers

that inluence employee attitudes. We address two key questions (Armstrong-Stassen, Cameron, Mantler, & Horsburgh, 2001; Fu-

about organizational change in this article. First, what are the gate, Kinicki, & Scheck, 2002; Terry, Callan, & Sartori, 1996), and

salient dimensions of organizational change that individuals per- acquisitions (e.g., Scheck & Kinicki, 2000). These studies are

ceive in their workplace? Second, how do perceptions of change important, but do not identify the properties of change events that

characteristics influence individual outcomes? We use Lazarus and lead to negative employee outcomes. This is a critical limitation of

Folkman’s (1984) cognitive phenomenological or transactional existing work because without knowing what features of change

model of stress and coping to identify three distict change char- situations are perceived negatively and that are associated with

acteristics: the frequency impact, and planning of change. We poor outcomes, it is difficult to manage the implementation of

describe why these characteristics are salient to individuals and change. The lack of research attention on the characteristics of

how they can influence employees attitudes and well being. Spe- change is not an omission of the transactional model itself. Lazarus

cifically, we use the model to propose ways that individuals’ and Folkman described a number of formal properties of situations

subjective understandings of these characteristics influence ap- that make them potentially damaging or negative for individuals.

praisals of change, and, ultimately, job satisfactions and turnover We draw on this work, and derive three specific characteristics of

intentions. This study has important practical applications as it is change events that are salient to individuals and that are likely to

currently difficult for managers and practitioners to implement influence employees’ responses to change.

change effectively in the absence of information about what char-

acteristics of change eventsd influence employees’ reactions to

change. The Frequency of Change

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) identified a number of temporal

Change Characteristics properties of situations that can have a negative impact on indi-

Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transactional model has been viduals including the imminence, duration, and temporal uncer-

used to investigate the impact of organizational change on coping tainty surrounding events. Other authors have argued that individ-

and well-being from a number of perspectives. Most often, studies uals are concerned with the timing of change in the workplace, and

make judgments about whether change occurs very frequently or

infrequently (Glick, Huber, Miller, Harold, & Sutcliffe, 1995;

Monge, 1995). We identify the frequency of change, which cap-

Alannah E. Rafferty, School of Management, Queensland University of tures individuals’ perceptions regarding how often change has

Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; Mark A. Griffin, Australian occurred in their work environment, as an important characteristic

Graduate School of Management, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, of change that is salient to individuals. Glick et al. argued that the

New South Wales, Australia, and The University of Sydney, Australia.

more infrequently change occurs the more likely it is to be per-

This study was supported by an Australian Research Council Large

Grant A79601474.

ceived as a discrete event, and employees will be able to identify

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Alannah a clear beginning and end point of change. In contrast, when

E. Rafferty, School of Management, Queensland University of Technol- changes are frequent, organizational members are less likely to

ogy, 2 George Street, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia 4001. E-mail: perceive change as a discrete event and are likely to feel that

a.rafferty@qut.edu.au change is highly unpredictable. When change occurs very fre-

1154PERCEPTIONS OF ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE 1155

quently, individuals are likely to feel fatigued by change and et al. (1999) examined how individuals cope with job loss after

experience an increase in anxiety due to the unpredictability of downsizing, and operationalized cognitive appraisal in terms of

change in that setting. reversibility, or an individual’s perception that he or she can gain

reemployment. In contrast, Terry et al. (1996) stated that the extent

The Impact of Change to which an event is considered stressful is central to a person’s

appraisal of a situation. However, many researchers have found

There is considerable agreement in the organizational change that an important outcome of change is employee uncertainty (e.g.,

literature that people are concerned with what the impact of change Davy, Kinicki, Kilroy, & Scheck, 1988; Marks & Mirvis, 1985;

will be on themselves, their job, and on their work colleagues (e.g., Miller & Monge, 1985; Nelson, Cooper, & Jackson, 1995). Laza-

Herscovitch & Meyer, 2002; Lau & Woodman, 1995; Weber & rus and Folkman also identified uncertainty as a property of

Manning, 2001). When discussing the impact of change in the situations that makes them harmful or negative for individuals. We

workplace, authors have drawn a fundamental distinction between propose that uncertainty is a critical cognitive appraisal resulting

incremental, or first-order change and transformational, or second- from change. Uncertainty refers to the psychological state of doubt

order change (e.g., Bartunek & Moch, 1987; Levy, 1986). We about what an event signifies or portends (DiFonzo & Bordia,

argue that the impact of change is salient to individuals, and use 1998). The following hypotheses have been proposed:

the term transformational change, which refers to an individual’s

perception regarding the extent to which change has involved Hypothesis 1A: The perception that change has been imple-

modifications to the core systems of an organization including mented after deliberation and planning will display a sig-

traditional ways of working, values, structure, and strategy. Levy nificant, unique negative relationship with psychological

stated that transformational change, by its very nature, involves a uncertainty.

dramatic shift in basic aspects of an organization. Lazarus and

Folkman (1984) identified the novelty of an event as a property of Hypothesis 1B: The perception that change is very frequent

situations that makes them harmful or threatening for individuals. will display a significant, unique positive relationship with

A novel situation is one in which a person has not had previous psychological uncertainty.

experience. Periods of transformational change are likely to be

Hypothesis 1C: The perception that change has resulted in

experienced as highly novel events as people are required to act in

significant modifications to core aspects of an organization

completely new ways and to adopt new values.

will display a significant, unique positive relationship with

psychological uncertainty.

Planning Involved in Change

Empirical research suggests that the planning that accompanies Change Perceptions and Outcomes

change efforts is of major concern to employees (Armenakis, Two measures of well-being—job satisfaction and turnover

Harris, & Field, 1999; Eby, Adams, Russell, & Gaby, 2000; intentions—are examined in the present study. Job satisfaction

French & Bell, 1999; Korsgaard, Sapienza, & Schweiger, 2002; refers to an individual’s global feeling about his or her job (Spec-

Levy, 1986; Orlikowski & Hofman, 1997; Porras & Robertson, tor, 1997), and is the most commonly studied short-term outcome

1992; Weingart, 1992). Authors have reported that when planning of research on occupational health (Kinicki, McKee, & Wade,

precedes organizational change efforts, individuals’ well-being is 1996). Turnover intentions refer to an individual’s desire or will-

enhanced (e.g., Korsgaard et al., 2002). Lazarus and Folkman ingness to leave an organization. In many models, turnover inten-

(1984) argued that a property of situations that makes them po- tions are the immediate precursor to turnover (e.g., Hom,

tentially damaging or negative for individuals is how unpredictable Caranikas-Walker, Prussia, & Griffeth, 1992; Mobley, 1977), and

they are, or the extent to which there is some type of warning that the relationship between turnover intentions and turnover has been

something painful or harmful is about to happen. We identify the well documented (e.g., Hom, Griffeth, & Sellaro, 1984).

extent of planning that accompanies the introduction of change as Empirical evidence indicates that psychological uncertainty is

salient to individuals. Planned change is defined as individuals’ associated with a range of outcomes including job satisfaction and

perception that deliberation and preparation have occurred prior to turnover intentions (Ashford, Lee, & Bobko, 1989; Moyle &

the implementation of change. When efforts are made to plan Parkes, 1999). Importantly, a number of studies indicate that

change in advance, change becomes more predictable as people are psychological uncertainty is a critical factor that mediates relation-

provided with information about the imminence of change and the ships between organizational change and well-being (Moyle &

likely duration of change. In addition, when planning occurs prior Parkes, 1999; Pollard, 2001; Schweiger & DeNisi, 1991). Thus,

to change implementation, the novelty of a change event is likely the following hypotheses have been proposed:

to be reduced.

Hypothesis 2A: Psychological uncertainty will be positively

Appraisal related to turnover intentions and negatively related to job

satisfaction.

Cognitive appraisal, or the meaning that individuals give to a

particular event, plays a central role in the transactional model Hypothesis 2B: The perception that change has occurred after

(Dewe, 1991; Fugate et al., 2002; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). deliberation and planning will be indirectly positively related

Authors have examined a range of different cognitive appraisals to job satisfaction and indirectly negatively related to turn-

when testing Lazarus and Folkman’s model. For example, Gowan over intentions mediated through psychological uncertainty.1156 RAFFERTY AND GRIFFIN

Hypothesis 2C: The perception that change has occurred very high level of leader support can be regarded as a coping resource

frequently will be indirectly negatively related to job satis- as a supportive leader provides information and advice that an

faction and indirectly positively related to turnover intentions individual can draw on when confronted with change (Russell,

mediated through psychological uncertainty. Altmaier, & Van Velzen, 1987; Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-

Glaser, 1996). Conscientiousness reflects dependability or being

In addition, it is proposed that transformational change and the thorough, responsible, and organized (Costa & McCrae, 1989).

frequency of change are likely to display direct relationships with Conscientiousness is likely to be a coping resource as people high

job satisfaction and turnover. We do not make any hypotheses on this personality dimension are likely to persevere when faced

concerning direct relationships between planned change and out- with change (Barrick & Mount, 1991).

comes as we argue that this change perception primarily acts

through positively influencing psychological uncertainty. In con- Method

trast, we argue that an individual’s perception regarding the extent

of transformational change that has occurred in his or her work Procedure and Participants

environment is likely to impact how an individual performs his or This study was conducted in a large Australian public sector organiza-

her job and the very nature of the job. As such, it is likely that the tion, whose primary task involves the strategic development of road infra-

perception that a great deal of transformational change has oc- structure and the management of an extensive road network. A repeated

curred will reduce job satisfaction. In addition, the unfolding cross-sectional design was adopted. That is, an organizational change

model of turnover (Lee & Mitchell, 1994; Lee, Mitchell, Wise, & survey was administered one month prior to an employee attitude survey in

Fireman, 1996) posits that one factor that contributes to turnover is consecutive years. The data collected in the first year of the study are

referred to as Sample 1, while the data collected in the second year of the

“shocks to the system,” which are distinguishable events that jar

study are referred to as Sample 2. For the two change surveys, three

employees toward deliberate decisions about their jobs and, per- employees and at least one manager from each work group in the organi-

haps, to voluntarily quit their jobs. We propose that transforma- zation were randomly selected to receive the survey. In Sample 1, the

tional change is likely to cause individuals to deliberate about their change survey was distributed to 745 employees and 599 were returned

job and will increase intentions to turnover. Thus, the following (response rate ⫽ 80.4%). In Sample 2, the change survey was administered

hypotheses have been proposed: to 945 employees and 700 were returned (response rate ⫽ 74.1%).

One month after the change survey was administered, an employee

Hypothesis 3A: The perception that change has resulted in attitude survey assessing the coping resources, two control measures, and

significant modifications to core aspects of an organization the two outcomes was distributed to all staff. Three thousand two hundred

will display a unique negative relationship with job satis- forty-five surveys were returned in Sample 1 (response rate ⫽ 77%). Two

faction and a unique positive relationship with turnover thousand eight hundred and sixty-four surveys were returned in Sample 21

intentions. (response rate ⫽ 63%). Not all survey respondents provided the informa-

tion required to match the change and employee attitude surveys. As a

We further propose that when change occurs very frequently, result, the organizational change survey and employee attitude survey were

only able to be matched for 207 respondents in Sample 1 (34% of the

individuals are likely to feel mentally fatigued by needing to

change surveys could be matched at Time 1) and 168 respondents in

constantly adapt to change, which will reduce job satisfaction and Sample 2 (24% of change surveys could be matched at Time 2). Respon-

increase intentions to leave the organization. dents could not be matched between Sample 1 and Sample 2.

Hypothesis 3B: The perception that change is very frequent

Context of the Study

will display a unique negative relationship with job satisfac-

tion and a unique positive relationship with turnover When the data from Sample 1 were collected, the Director–General of

intentions. the organization had just moved to another public sector agency after a

five-year period with the company. The Director–General was replaced by

an internal candidate who faced a difficult task as the previous leader was

Coping Resources an extremely popular individual who was often spoken of as a charismatic

The transactional model proposes that coping resources, or the leader. At the time that the Sample 2 data were collected, there had been

a number of additional dramatic and wide-reaching changes in the public

resources that people draw upon in order to deal with a given

sector in the state. In particular, the government had called for voluntary

situation, directly influence an individual’s cognitive appraisal redundancies that resulted in more than 500 individuals leaving the public

about a situation. Authors have examined a variety of coping service. In addition, at this time, the government also began to amalgamate

resources including social support (Scheck & Kinicki, 2000) and all of the human resource functions in the separate public sector agencies

dispositional optimism (Chang, 1998). A number of coping re- into a single entity. This amalgamation resulted in wholesale changes in the

sources are examined in our study including neuroticism, consci- human resource function in the public service.

entiousness, and leader social support. We did not develop specific

hypotheses for the different coping resources. Rather, we included Development of Organizational Change Measures and

coping variables as controls to provide a more complete test of our Psychological Uncertainty

hypotheses about the relationships among change perceptions,

Items to assess individuals’ perceptions of change were developed after

uncertainty, and outcomes. conducting semistructured interviews with employees. Next, the change

A low level of neuroticism can be regarded as a coping resource

in stressful situations as individuals high in neuroticism tend to

focus on the associated level of distress rather than engaging in 1

The Sample 2 employee attitude data reported in this article (n ⫽ 168)

goal-directed behavior (Parkes, 1986; Terry, 1994). Similarly, a is a subset of the data reported in Rafferty & Griffin (in press).PERCEPTIONS OF ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE 1157

items were administered to more than 200 employees in two pilot studies. Properties of the change scales. To test whether the measures of

A process of iterative item development was adopted such that items that change and uncertainty were distinct, we conducted a series of confirma-

did not load onto their hypothesized factor in the first pilot study were tory factor analyses (CFAs; Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Three nested

removed or modified (Hinkin, 1995, 1998). The modified set of items was CFA models were estimated in Sample 1 (n ⫽ 207) and Sample 2 (n ⫽

then administered to employees participating in the second pilot study. The 168). All model tests were based on the covariance matrix and used

result of this process was three three-item change measures and a four-item maximum likelihood estimation as implemented in LISREL 8.3 (Jöreskog

measure of psychological uncertainty. & Sörbom, 1996). We tested a one-factor model in which all items loaded

onto one factor, a two-factor model in which the uncertainty items loaded

Change Surveys onto one factor and change items loaded onto a single factor, and a

four-factor model with three change measures plus uncertainty. Table 2

A 7-point Likert scale was used for all of the change scales (see Table reports the fit indices for these different models in both samples. The

1) and the uncertainty scale. For the transformational change and planned results show that the four-factor model was the best fit to the data, with

change scales, responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 7 (a great deal). For adequate fit indices in both samples. All of the items loaded onto their

the frequency of change and the psychological uncertainty scale, responses hypothesized factors ( p ⬍ .001; see Table 1), and the latent factors

ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Employees were explained a substantial amount of variance in the items (R2s ranged from

asked to respond to the change items, keeping in mind the changes that .28 to .77 for Sample 1 and .32 to .96 for Sample 2).

occurred in their work environment in the past three months.

Transformational change. An example of an item on this scale is as Employee Attitude Surveys

follows: “To what extent have you experienced changes to the values of

your unit.” This scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .89 in Sample 1 and an Job satisfaction, neuroticism, and conscientiousness were assessed using

alpha of .87 in Sample 2. a 7-point Likert scale with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to

Planned change. An example of an item on this scale is the following: 7 (strongly agree). Turnover intentions was assessed using a 5-point scale

“Change has involved prior preparation and planning by my manager and with responses ranging from 1 (definitely not) to 5 (definitely yes). Leader

work group.” This scale had an alpha of .76 in Sample 1 and an alpha of support was assessed on a 5-point scale with responses ranging from 1

.90 in Sample 2. (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Frequent change. An example of an item on this scale is as follows: Job satisfaction. Three items assessed this construct (Hart, Griffin,

“It feels like change is always happening.” This scale had a Cronbach alpha Wearing, & Cooper, 1996). An example item is the following: “Overall, I

of .76 in Sample 1 and in Sample 2. am satisfied with my job.” This scale had an alpha of .89 in Sample 1 and

Psychological uncertainty. The psychological uncertainty items were in Sample 2.

developed on the basis of work by Milliken (1987). An example item is the Turnover intentions. This construct assesses an individual’s intentions

following: “I am often uncertain about how to respond to change.” This to leave his or her job, and was assessed by three items (Hart et al., 1996).

scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .88 in Sample 1 and .91 in Sample 2. An example of an item is as follows: “I seriously intend to seek a transfer

Table 1

Factor Loadings for the Four-Factor CFA in Sample 1 and Sample 2

Frequent Planned Transformational

Items change change change Uncertainty

1. Change frequently occurs in my unit .82

.80

2. It is difficult to identify when changes start and end .53

.57

3. It feels like change is always happening .84

.80

4. Change has involved prior preparation and planning by my manager or unit .56

.82

5. Change has been the result of a deliberate decision to change by my manager/unit .81

.98

6. Change has occurred due to goals developed by my manager or unit .76

.80

7. Large scale changes significantly changing your unit’s goals .85

.85

8. Changes that affect my work unit’s structure .86

.83

9. Changes to the values of my work unit .87

.84

10. My work environment is changing in an unpredictable manner .76

.74

11. I am often uncertain about how to respond to change .80

.85

12. I am often unsure about the effect on change on my work unit .88

.91

13. I am often unsure how severely a change will affect my work unit .81

.93

Note. Sample 1 results are presented above Sample 2 results. All items are significant at p ⬍ .001. CFA ⫽ confirmatory factor analysis.1158 RAFFERTY AND GRIFFIN

Table 2

Model Fit Indices for the Measurement Models in Sample 1 and Sample 2 (Including All Items)

Model comparison 2 df GF1 RMSEA CFI NNFI

One-factor model 985.68 65 .57 .26 .51 .42

1,085.61 65 .55 .28 .51 .41

Two-factor model 437.44 64 .75 .17 .74 .68

546.13 64 .66 .21 .67 .59

Four-factor model 146.37 59 .90 .09 .93 .91

140.53 59 .90 .08 .95 .93

Note. Sample 1 results are presented above Sample 2 results. n ⫽ 207 in Sample 1. n ⫽ 168 in Sample 2. GFI ⫽ Goodness of Fit Index; RMSEA ⫽ Root

Mean Square Error of Approximation; CFI ⫽ Comparative Fit Index; NNFI ⫽ Nonnormed Fit Index.

to another job in the future.” This scale had an alpha of .76 in Sample 1 and of Fit Index (GFI) ⫽ .90, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ⫽ .93,

in Sample 2. Nonnormed Fit Index (NNFI) ⫽ .90, root mean square error of

Neuroticism. Five items assessed neuroticism, and three of these items approximation (RMSEA) ⫽ .06 and Sample 2, 2(124, N ⫽

were reverse scored (Costa & McCrae, 1989). An example item in this

168) ⫽ 246.42, p ⬍ .001; GFI ⫽ .89, CFI ⫽ .93, NNFI ⫽ .89,

scale is as follows: “I often feel tense and jittery.” A higher score on this

RMSEA ⫽ .07. The fit of the hypothesized model was also not

scale indicates higher neuroticism. This scale had a Cronbach alpha of .67

in Sample 1 and Sample 2. significantly different to the fit of the measurement model in

Conscientiousness. Five items assessed conscientiousness (Costa & Sample 1, ⌬2(2, N ⫽ 207) ⫽ 0.21, ns, or in Sample 2, ⌬2(2, N ⫽

McCrae, 1989). An example item is the following: “I try to perform all the 168) ⫽ 1.09, ns. Therefore, we accepted the hypothetical model as

tasks assigned to me conscientiously.” This scale had an alpha of .75 in an adequate representation of the variances and covariances among

Sample 1 and an alpha of .71 in Sample 2. the measures.

Leader support. Three items assessed supportive leadership (Rafferty We next tested whether the key structural paths in the hypoth-

& Griffin, 2004). An example of an item used in the current study is the esized model and key correlations between measures, including the

following: “My work unit leader sees that the interests of employees are

relationships among the change factors and uncertainty and the

given due consideration.” This scale had an alpha of .92 in Sample 1 and

.93 in Sample 2. two outcomes measures, were different across the two samples.

Control measures. Two control measures were assessed including We used a multigroup comparison in which the structural paths of

seniority in the organization and age. Seniority is a measure of an individ- interest and the correlations among latent variables were con-

ual’s position in the organizational hierarchy as assessed by his or her job strained to be equal in both samples. The constrained model was

classification. A higher score on this measure indicates that an individual not significantly different to the unconstrained model, ⌬2(46,

is in a more senior position in the organization. Age was assessed in years. N ⫽ 207 in Sample 1 and N ⫽ 168 in Sample 2) ⫽ 59.54, ns. This

result suggests that differences in values of the structural paths and

Results correlations of the two samples can be attributed to sampling error.

Therefore, we tested the final model using the paths from the

First, we estimated an 11-factor CFA model that included latent

variables for the three change measures and uncertainty, and that constrained model. The hypothesized paths between the change

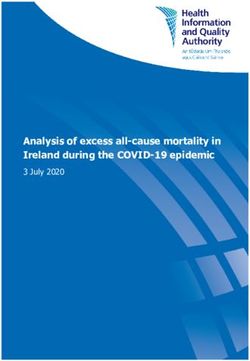

included all other measures as single indicators. This model be- perceptions, psychological uncertainty, and outcomes are depicted

came the basis for subsequent model tests. Table 3 displays the in Figure 1. The structural paths between the coping resources and

means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study control measures and the substantive measures are reported in

variables in Sample 1 and Sample 2 for the 11-factor measurement Table 4.

model. Hypothesis 1A was supported as the planning of change was

Next, we examined the structural paths between the study mea- significantly negatively associated with psychological uncertainty

sures in Sample 1 and Sample 2. In this model, regression paths ( ⫽ ⫺.17, p ⬍ .01). Hypothesis 1B was also supported as the

from the three change perceptions to psychological uncertainty frequency of change was positively associated with uncertainty

were estimated, and, in turn, uncertainty was related to job satis- ( ⫽ .55, p ⬍ .001). In contrast, Hypothesis 1C was not supported

faction and turnover intentions. In addition, direct relationships as transformational change was not significantly associated with

were estimated between transformational change and satisfaction uncertainty ( ⫽ .10, p ⬎ .05).

and turnover intentions and between the frequency of change and Hypothesis 2A was supported as uncertainty was negatively

turnover intentions. The three change characteristics were allowed related to satisfaction ( ⫽ ⫺.15, p ⬍ .01), and positively related

to intercorrelate as were the outcome measures. The coping re- to turnover intentions ( ⫽ .17, p ⬍ .01). Hypothesis 2B was

sources (neuroticism, conscientiousness, and leader support) and supported by results from the Sobel Test (Sobel, 1982), which

control variables (age and seniority) were all intercorrelated. Di- showed the indirect path from planning to satisfaction was signif-

rect relationships were estimated from these five measures to icant (Sobel ⫽ 1.20, p ⬍ .05; indirect effect ⫽ .03, p ⬍ .05), as

uncertainty, the three change perceptions, and the two outcome was the indirect path from planning to turnover intentions (So-

measures. bel ⫽ ⫺2.04, p ⬍ .05; indirect effect ⫽ ⫺.03, p ⬍ .05). Hypoth-

The hypothesized structural model was a good fit to the data in esis 2C received partial supported as the frequency of change was

both Sample 1, 2(124, N ⫽ 207) ⫽ 221.88, p ⬍ .001; Goodness indirectly related to both satisfaction (Sobel ⫽ ⫺2.25, p ⬍ .05;PERCEPTIONS OF ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE 1159

indirect effect ⫽ ⫺.05, p ⬍ .05) and turnover intentions (Sobel ⫽

.33***

.27***

⫺.17**

⫺.18**

.19**

.21**

⫺.18**

2.30, p ⬍ .05; indirect effect ⫽ .08, p ⬍ .05). However, transfor-

11

—

⫺.02

⫺.06

.03

mational change was not significantly related to either outcome via

uncertainty.

.24***

.24***

.58***

.45***

⫺.33***

Hypothesis 3A was partially supported. There was a significant

⫺.23**

10

—

.06

⫺.03

.15

⫺.10

direct path from transformational change to turnover intentions

( ⫽ .21, p ⬍ .01), but not to satisfaction ( ⫽ .02, ns). Hypothesis

3B was not supported as the frequency of change was not directly

⫺.33***

.41***

.56***

.27***

⫺.18** negatively related to satisfaction ( ⫽ .07, ns) or turnover inten-

—

⫺.03

⫺.05

.03

⫺.06

⫺.13

9

Note. Sample 1 correlations are reported above the diagonal and Sample 2 correlations are reported below the diagonal. n ⫽ 207 in Sample 1. n ⫽ 167 in Sample 2.

tions ( ⫽ ⫺.07, ns).

Table 4 indicates that the control measures and the coping

resources accounted for 7% of the variance in perceptions of the

.60***

.66***

.28**

.17*

frequency of change, 3% of the variance in perceptions of the

—

⫺.07

.10

⫺.03

⫺.13

.13

⫺.10

8

planning in change, and 4% of the variance in the transformational

change perceptions. Figure 1 shows that the control measures,

.18*

coping resources, and the change perceptions accounted for 48%

.07

⫺.09

.10

.32

.16

⫺.10

.12

.02

—

7

of the variance in uncertainty. Finally, the control measures, cop-

Means, Standard Deviations, and Factor Intercorrelations for Sample 1 and Sample 2 for the 11-Factor Measurement Model

ing resources, and the change perceptions accounted for 37% of

Correlation

.67***

.43***

.26***

the variance in job satisfaction and 23% of the variance in turnover

—

.08

.13

⫺.12

⫺.02

⫺.02

.15

.03

6

intentions.

Discussion

.29***

⫺.21***

⫺.29***

.44***

⫺.28***

.20**

⫺.18*

—

.01

.13

⫺.09

5

A key contribution of this study is the identification of three

characteristics of change events that influence individuals’ re-

sponse to change and, ultimately, their job satisfaction and turn-

.24***

.42***

.18**

over intentions. Our study shows that individuals perceive and

—

.14*

.17*

4

.14

.13

.06

.03

.03

differentiate the frequency of change, the planning involved in

change, and the impact of change, and provides a new way of

⫺.28***

.34***

.28***

conceptualizing and measuring salient features of change that

.22**

⫺.15*

.16*

⫺.18*

—

3

.00

.03

⫺.06

individuals encounter in organizations. Because these constructs

describe general features of change in an environment, we expect

them to be relevant in most organizations experiencing change.

.38***

⫺.34***

.19**

.22**

.15*

.17*

⫺.16*

Individuals’ perceptions of these three aspects of change were

—

.08

.06

⫺.06

2

related, in expected and meaningful ways, to job satisfaction and

turnover intentions. Specifically, the planning of change was in-

.27***

directly positively related to job satisfaction and indirectly nega-

1.03 ⫺.18**

—

1

.02

.14

.01

.14

.14

.07

.06

.08

tively related to turnover intentions, mediated through psycholog-

ical uncertainty. The frequency of change was indirectly

10.95

2.23

1.13

0.83

1.08

1.64

1.48

1.44

1.54

1.25

negatively associated with satisfaction and positively associated

SD

Sample 2

with turnover intentions via uncertainty. In contrast, transforma-

tional change was not significantly associated with uncertainty.

39.14

4.63

3.47

5.48

3.36

3.36

3.48

4.03

3.84

4.90

2.27

Rather, transformational change displayed a direct positive rela-

M

tionship with intentions to turnover. This result provides support

for the unfolding model of turnover (Lee et al., 1996), which

10.67

2.35

1.01

0.95

0.95

1.70

1.24

1.41

1.42

1.20

.99

SD

suggests that “shocks to the system” jar employees toward delib-

Sample 1

erate decisions about their jobs and, perhaps, to voluntarily quit

* p ⬍ .05. ** p ⬍ .01. *** p ⬍ .001.

their jobs. Transformational changes represent modifications to

36.42

4.51

3.34

5.37

3.51

3.44

4.12

3.94

3.84

5.01

2.11

M ⫽ mean; SD ⫽ standard deviation.

M

core aspects of a firm, and such changes appear to encourage

people to carefully consider their position in an organization.

Psychological uncertainty

Results also suggest that supportive leadership had a strong

impact on all three change perceptions. This finding suggests that

Frequency of change

Turnover intentions

Transform. change

it is important to ensure that leaders understand the need to provide

Planned change

Job satisfaction

Variable

Leader support

support and consider individuals’ needs in a changing environ-

Neuroticism

ment. Specifically, employees with supportive leaders reported

Seniority

less transformational change and less frequent change, and also

Consc.

reported that more planned change had occurred. Individuals with

Table 3

Age

supportive work unit leaders also reported experiencing less psy-

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

chological uncertainty than individuals who did not report that1160 RAFFERTY AND GRIFFIN

Figure 1. Standardized structural paths in the constrained multigroup model. * p ⬍ .05. **p ⬍ .01. ***p ⬍

.001.

their leader was supportive. In addition, individuals in more senior coping strategies, and emotional responses. In addition, while job

positions within the organization reported more planned change satisfaction and turnover intentions are important outcomes, a

and that change was more frequent than did individuals lower in range of other indicators of adjustment should be assessed includ-

the hierarchy. The findings regarding seniority are not surprising ing psychological well-being (Terry et al., 1996) and distress

as individuals at a higher level in the organization are more likely (Gowan et al., 1999), in addition to the coping strategies selected

to be involved in planning and deliberating about organizational in response to change (Terry, 1994; Terry et al., 1996).

changes. In addition, more senior employees are also more likely

to receive more information about key strategic events occurring in Strengths and Limitations

the company, including organizational change.

Another contribution of this study was the development of An important strength of this article was the separate measure-

multi-item measures of change perceptions, which were found to ment of change perceptions and employee attitudes so as to reduce

be reliable and can be used in future studies when assessing the effects of common method variance. Ostroff, Kinicki, and

characteristics of change that influence employees’ attitudes. It is Clark (2002) reported that the temporal separation of administra-

important that researchers use a standard set of measures to assess tion of measures is a valid approach to reducing response bias

individuals’ perceptions of the change context so as to enable associated with common method variance. In addition, this study

comparison of findings across studies. utilizes a repeated cross-sectional design that allows us to deter-

One area for future research concerns examining additional mine the extent to which results are replicable and enhances our

elements of the transactional model including secondary appraisal, confidence in the findings.

Table 4

Standardized Paths for the Relations Between the Control Measures and Coping Resources and the Change Perceptions and

Outcomes in the Constrained Multigroup Model

Transformational Planned Frequency Job Turnover

Variable/Resource change change of change Uncertainty satisfaction intentions

Control variable

Age .07 .04 ⫺.06 .05 .07 ⫺.20***

Seniority .10 .12* .16* ⫺.05 .08 ⫺.06

Coping resource

Neuroticism .01 ⫺.02 .09 .08 .01 .25***

Conscientiousness .05 .03 ⫺.05 ⫺.03 .41*** .10*

Leader support ⫺.15** .10* ⫺.18** ⫺.14** .31*** ⫺.07

Variance explained .04 .03 .07 .03 .28 .12

* p ⬍ .05. ** p ⬍ .01. *** p ⬍ .001.PERCEPTIONS OF ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE 1161

A number of limitations of our study should also be noted. In uncertainty during organizational change. Human Resource Manage-

particular, we focused on processes at the individual level of ment, 37, 295–303.

analysis, Further research should investigate processes at other Eby, L. T., Adams, D., M., Russell, J. E. A., & Gaby, S. H. (2000).

levels. For example, it will be important to obtain measures of Perceptions of organizational readiness for change: Factors related to

employees’ reactions to the implementation of team-based selling. Hu-

change events at the group and organization level that are inde-

man Relations, 53, 419 – 442.

pendent of respondent perceptions. A limitation of the study was

French, W. L., & Bell, C. H. (1999). Organization development: Behav-

that uncertainty was measured in the same survey as the change ioral science interventions for organizational improvement (6th ed.).

characteristics. As a result, we have not eliminated the common Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

method variance issue in regard to the relationships between the Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Scheck, C. L. (2002). Coping with an

change characteristics and the cognitive appraisal of uncertainty. organizational merger over four states. Personnel Psychology, 55, 905–

Another limitation is the issue of reverse causality. We have 928.

argued that perceptions of change influence uncertainty and satis- Glick, W. G., Huber, G. P., Miller, C. C., Harold, D., & Sutcliffe, K. M.

faction as well as turnover intentions. However, it is possible that (1995). Studying changes in organizational design and effectiveness:

the reverse relationship is in operation. For example, it may be that Retrospective event histories and periodic assessments. In G. P. Huber &

high levels of job dissatisfaction and uncertainty are responsible A. H. Van de Ven (Eds.), Longitudinal field research methods: Studying

processes of organizational change (pp. 126 –154). Thousand Oaks, CA:

for people reporting that change is very frequent, that a great deal

Sage.

of transformational change has occurred, and that change has

Gowan, M. A., Riordan, C. M., & Gatewood, R. D. (1999). Test of a model

involved little preparation and planning prior to implementation. of coping with involuntary job loss following a company closing.

To distinguish whether change perceptions influence uncertainty Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 75– 86.

and outcomes or whether job dissatisfaction and uncertainty influ- Hart, P. M., Griffin, M. A., Wearing, A. J., & Cooper, C. L. (1996).

ence change perceptions, there is a need to conduct a longitudinal QPASS: Manual for the Queensland Public Agency Staff Survey. Bris-

examination of these relationships. Finally, a further limitation of bane, Queensland, Australia: Public Sector Management Commission.

this study was that both samples of respondents were obtained Herscovitch, L., & Meyer, J. P. (2002). Commitment to organizational

from the same public sector organization. As such, any findings change: Extension of a three-component model. Journal of Applied

obtained may reflect unique characteristics of the organization Psychology, 87, 474 – 487.

under study. Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of scale development practices in the study

of organizations. Journal of Management, 21, 967–988.

Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for

References use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1,

104 –121.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in Hom, P. W., Caranikas-Walker, F., Prussia, G. E., & Griffeth, R. E. (1992).

practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological A meta-analytical structural equations analysis of a model of employee

Bulletin, 103, 411– 423. turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 890 –909.

Armenakis, A. A., Harris, S. G., & Field, H. S. (1999). Making change Hom, P. W., Griffeth, R. W., & Sellaro, C. L. (1984). The validity of

permanent: A model for institutionalizing change interventions. In W. Mobley’s (1977). model of employee turnover. Organizational Behavior

Pasmore & R. Woodman (Eds.), Research in organizational change and and Human Performance, 34, 141–175.

development (Vol. 12, pp. 97–128). Stamford, CT: JAI Press. Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1996). LISREL 8 user’s reference guide.

Armstrong-Stassen, M., Cameron, S. J., Mantler, J., & Horsburgh, M. E. Chicago: Scientific Software International.

(2001). The impact of hospital amalgamation on the job attitudes of Kinicki, A. J., McKee, F. M., & Wade, K. J. (1996). Annual review

nurses. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 18, 149 –162. 1991–1995: Occupational health. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 49,

Ashford, S. J., Lee, C., & Bobko, P. (1989). Content, causes, and conse- 190 –220.

quences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Korsgaard, M. A., Sapienza, H. J., & Schweiger, D. M. (2002). Beaten

Academy of Management Journal, 32, 803– 829. before begun: The role of procedural justice in planning change. Journal

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimen- of Management, 28, 497–516.

sions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, Lau, C., & Woodman, R. W. (1995). Understanding organizational change:

1–26. A schematic perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 537–

Bartunek, J. M., & Moch, M. K. (1987). First-order, second-order, and 554.

third-order change and organization development interventions: A cog- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New

nitive approach. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 23, 483–500. York: Springer.

Chang, E. C. (1998). Dispositional optimism and primary and secondary Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. (1994). An alternative approach: The

appraisal of a stressor: Controlling for confounding influences and unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. Academy of Manage-

relations to coping and psychological and physical adjustment. Journal ment Review, 19, 51– 89.

of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1109 –1120. Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Wise, L., & Fireman, S. (1996). An unfolding

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1989). NEO-PI/FFI: Manual supplement. model of voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 39,

Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. 5–36.

Davy, J. A., Kinicki, A. J., Kilroy, J., & Scheck, C. L. (1988). After the Levy, A. (1986). Second-order planned change: Definition and conceptu-

merger: Dealing with people’s uncertainty. Training and Development alization. Organizational Dynamics, 15, 5–20.

Journal, November, 57– 61. Marks, M. L., & Mirvis, P. H. (1985). Merger syndrome: Stress and

Dewe, P. J. (1991). Primary appraisal, secondary appraisal and coping: uncertainty. Mergers and Acquisitions, 20, 70 –76.

Their role in stressful work encounters. Journal of Occupational Psy- Miller, K. I., & Monge, P. R. (1985). Social information and employee

chology, 64, 331–351. anxiety about organizational change. Human Communication Research,

DiFonzo, N., & Bordia, P. (1998). A tale of two corporations: Managing 11, 365–386.1162 RAFFERTY AND GRIFFIN Milliken, F. J. (1987). Three types of perceived uncertainty about the consideration: Distinguishing developmental leadership and supportive environment: State, effect, and response uncertainty. Academy of Man- leadership. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. agement Review, 12, 133–143. Russell, D. W., Altmaier, E., & Van Velzen, D. (1987). Job-related stress, Mobley, W. H. (1977). Intermediate linkages in the relationship between social support, and burnout among classroom teachers. Journal of Ap- job satisfaction and job turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, plied Psychology, 72, 269 –274. 237–240. Scheck, C. L., & Kinicki, A. J. (2000). Identifying the antecedents of Monge, P. R. (1995). Theoretical and analytical issues in studying orga- coping with an organizational acquisition: A structural assessment. Jour- nizational processes. In G. P. Huber & A. H. Van de Ven (Eds.), nal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 627– 648. Longitudinal field research methods: Studying processes of organiza- Schweiger, D., & DeNisi, A. (1991). Communication with employees tional change (pp. 267–298). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. following a merger: A longitudinal field experiment. Academy of Man- Moyle, P., & Parkes, K. (1999). The effects of transition stress: A reloca- agement Journal, 34, 110 –135. tion study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 625– 646. Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural Nelson, A., Cooper, C. L., & Jackson, P. R. (1995). Uncertainty amidst equation models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1982 change: The impact of privatization on employee job satisfaction and (pp. 290 –312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, 68, 57–71. and consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Orlikowski, W. J., & Hofman, J. D. (1997). An improvisational model for Terry, D. J. (1994). Determinants of coping: The role of stable and change management: The case of groupware technologies. Sloan Man- situational factors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, agement Review, Winter, 11–21. 895–910. Ostroff, C., Kinicki, A. J., & Clark, M. A. (2002). Substantive and Terry, D. J., Callan, V. C., & Sartori, G. (1996). Employee adjustment to operational issues of response bias across levels of analysis: An example an organizational merger: Stress, coping and intergroup differences. of climate–satisfaction relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, Stress Medicine, 12, 105–122. 355–368. Uchino, B. N., Cacioppo, J. T., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (1996). The Parkes, K. R. (1986). Coping in stressful episodes: The role of individual relationship between social support and physiological processes: A differences, environmental factors, and situational characteristics. Jour- review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1277–1292. health. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 488 –531. Pollard, T. M. (2001). Changes in mental well-being, blood pressure and Weber, P. S., & Manning, M. R. (2001). Cause maps, sensemaking, and total cholesterol levels during workplace reorganization: The impact of planned organizational change. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Sci- uncertainty. Work and Stress, 15, 14 –28. ence, 37, 227–251. Porras, J. I., & Robertson, P. J. (1992). Organizational development: Weingart, L. R. (1992). Impact of group goals, task component complexity, Theory, practice and research. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), effort, and planning on group performance. Journal of Applied Psychol- Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 719 – 822). ogy, 77, 682– 693. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Rafferty, A. E., & Griffin, M. A. (2004). Dimensions of transformational leadership: Conceptual and empirical extensions. The Leadership Quar- Received June 18, 2004 terly, 15, 329 –354. Revision received May 17, 2005 Rafferty, A. E., & Griffin, M. A. (in press). Refining individualized Accepted June 6, 2005 䡲

You can also read