Parent Depression Symptoms and Child Temperament Outcomes: A Family Study Approach

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

bs_bs_banner

Parent Depression Symptoms and Child

Temperament Outcomes: A Family Study Approach

Jeffrey R. Gagne1, Catherine A. Spann, and Jerry C. Prater

Department of Psychology

University of Texas at Arlington

Parent personality and depression, family conflict, and child temperament were examined

in a family study design including two children 2.5–5.5 years of age. Sibling resemblance for

temperament was also investigated. Parent personality and family conflict had minimal

significance for child temperament outcomes. However, parent depression was associated

with higher child activity level and anger, and lower inhibitory control. These findings were

supported by more rigorous regression analyses that included parent depression, child

gender, and age as predictors. Sibling resemblance for child activity, anger and inhibitory

control was also present, supporting a genetic etiology for child temperament. These

findings indicate that children of depressed parents may be at increased risk for experienc-

ing behavioral maladjustment related to anger, hyperactivity, and impulse control.

Introduction

The family study research design presents researchers with the unique oppor-

tunity to compare family members on relevant behavioral phenotypes across

multiple dyadic relationships, most commonly between siblings or parent to

child. This study focuses on parent personality, depression symptoms, and rela-

tionship conflict, and how these parent- and family-level variables relate to child

temperament development. Child temperament is defined as early emerging,

relatively stable, biologically based behavioral, and emotional characteristics that

make up the basis of adult personality (Goldsmith et al., 1987; Shiner et al.,

2012). Research on child temperament spans most of the subdisciplines of behav-

ioral science, including developmental, personality and clinical psychology, and

neuroscience (Gagne, Vendlinski, & Goldsmith, 2009). Developmental scientists

1

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jeffrey R. Gagne, Department of

Psychology, University of Texas at Arlington, Box 19528, Arlington, TX 76019, USA. E-mail:

jgagne@uta.edu

175

Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 2013, 18, 4, pp. 175–197

© 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.176 GAGNE ET AL.

typically study early temperament traits because of predictive relations to impor-

tant developmental outcomes including child behavior problems and psychopa-

thology (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005; Goldsmith, Lemery, & Essex, 2004).

Therefore, investigating parent- and family-level behavioral phenotypes in the

context of child temperament has important public health relevance. If children

whose parents have increased levels of depression, negative personality traits and

high levels of family conflict are at risk for more adverse temperaments, these

family contexts can contribute to the development of subsequent child malad-

justment and psychiatric diagnoses. Comprehensive family studies of tempera-

ment that include parent and child measures can help clarify these issues, leading

to improved child and family assessment, earlier identification of risk factors, and

more effective clinical interventions.

Temperament is not a unitary construct, as specific domains or dimensions of

temperament represent different aspects of early developing behavior and

emotion. Thomas and Chess, who are credited with being the first modern

temperament theorists, defined nine temperament dimensions of activity, regu-

larity, initial reaction, adaptability, intensity, mood, distractibility, persistence/

attention span, and sensitivity in their theory (Chess & Thomas, 1984; Thomas,

Chess, & Birch, 1968). Some of these dimensions have been empirically supported

and persist in contemporary theory and research and others have fallen out of

scientific favor. Currently, the most commonly studied temperament dimensions

are activity level, anger/frustration, behavioral inhibition/fear, effortful or inhibi-

tory control, and positive affect (Gagne et al., 2009). Activity level refers to vigor

of movement; anger/frustration an approach-related negative affect; behavioral

inhibition/fear is distress or wariness toward novel or threatening stimuli;

effortful or inhibitory control is the ability to regulate impulses and activate

appropriate behavioral responses; and positive affect is defined as the experience

and expression of enjoyment. Most current research employs questionnaires

whereby the parent’s perception of child behavior is used as the primary tech-

nique for temperament measurement. Parent rating questionnaires of tempera-

ment are typically based on a dimensional structure, and questionnaire items are

organized into subscales that reflect these dimensions (Gagne, Saudino, &

Asherson, 2011). In general, parent ratings of child temperament are reliable and

valid, and are inexpensive and simple to use in a variety of studies (Gagne, Van

Hulle, Aksan, Essex, & Goldsmith, 2011).

In this investigation, we use a dimensionally comprehensive parent rating

with very specific questionnaire items to assess child temperament. One impor-

tant reason for this assessment strategy is that parent ratings of temperament in

family studies with siblings may be susceptible to contrast effects. These rater

biases occur when a parent rater overestimates differences between siblings as

demonstrated by very low or negative sibling correlations (Gagne, Van Hulle

et al., 2011). Parents, in effect propose that their children are of opposingPARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT 177

temperaments when we know that child temperament is genetically influenced

and therefore, there should be at least some level of sibling similarity across

temperament dimensions (as evinced by positive sibling correlations). Several

researchers have indicated that parent ratings of temperament that focus on very

specific behaviors (vs. global items) are less likely to show these contrast effects

(e.g., Goldsmith & Hewitt, 2003; Hwang & Rothbart, 2003; Saudino, 2003a;

Saudino, 2003b; Seifer, 2003).

As previously noted, researchers study early temperament because it is con-

sidered developmentally significant, and there exists an extensive literature on

cognitive development, education, and social development outcomes related to

temperament (Gagne et al., 2009). With regard to public health impact, early

child temperament is considered an important factor in the development of

childhood psychopathology and behavior problems (Goldsmith et al., 2004). In

general, low or high levels of temperament are shown to be risk factors for

problem behavior that may lead to psychopathology. For example, high behav-

ioral inhibition and fear dimensions have been consistently linked to internalizing

behavior problems, and high anger/frustration, activity level, and low effortful/

inhibitory control are related to externalizing behavior problems (Eisenberg

et al., 2001; Fagot & O’Brien, 1994; Gjone & Stevenson, 1997; Rothbart & Bates,

1998). Although as described, some temperament research focuses on subclinical

behavior problems in childhood, there are several investigations that assess spe-

cific psychiatric diagnoses in the context of temperament. These studies indicate

that negative affect (i.e., anger and fear) and behavioral inhibition are related to

anxiety, low positive affect and high negative affect are associated with depres-

sion, and high activity level and low effortful and inhibitory control are associ-

ated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Biederman et al., 2001; Brown,

2007; Campbell & Ewing, 1990; Clark, Watson, & Mineka, 1994; Durbin, 2010;

Gagne, Saudino et al., 2011; Hall, Halperin, Schwartz, & Newcorn, 1997; Kagan,

2001; Schachar, Tannock, Marriott, & Logan, 1995). Although we do not

examine the relationship between child temperament and child psychopathology

in the present study, these findings provide developmental and public health

relevance, as well as a strong rationale for examining links between parent mental

health (e.g., depression) and child temperament.

The study of individual differences in child temperament usually emphasizes

the child’s behavior and emotion, focusing on the assessment of temperament

dimensions in childhood samples. However, most researchers view the family

context as an important factor in the etiology and development of temperament.

When considering family effects on temperament, variables such as parent per-

sonality, parent affect, parent mental health, parenting style/sensitivity, family

interactions, and family socioeconomic (SES) status have all been explored in the

developmental literature. In this paper, parent personality, depression, and

family conflict experienced by the children in the study will be examined as178 GAGNE ET AL.

predictors of child temperament. Generally, positive parent personality traits,

low family conflict, and low parent depression predict more optimal levels of

child temperament.

Studies of parent personality traits and child temperament dimensions have

been somewhat limited, and many examine indirect effects or moderating vari-

ables. For example, maternal personality measures of negative control have been

found to interact with child inhibitory control to affect externalizing behavior

problems, such that children with low levels of inhibitory control who have

mothers with higher negative control have increased externalizing problems (van

Aken, Junger, Verhoeven, van Aken, & Deković, 2007). In a related study,

paternal personality and parenting style interacted differentially depending on

the level of effortful control in 36-month-old children (Karreman, van Tuijl, van

Aken, & Deković, 2008). Also, higher maternal extraversion (in the positive

direction) and lower parenting-related stress predict early childhood effortful

control (Gartstein, Bridgett, Young, Panksepp, & Power, 2013; Komsi et al.,

2008). Some research has suggested that parent views of their child’s tempera-

ment can affect their own personality development. Findings from one study

indicated that parent personality changes occur prenatally to postnatally as a

consequence of perceptions of their child’s temperament, with perceptions of

positive temperament predicting positive personality change in mothers and

fathers (Sirignano & Lachman, 1985). A more recent investigation examined a

similar model, finding that infant positive affect resulted in increases in parent

extraversion over a 5-year period, and infant activity level predicted decreases in

parent neuroticism (Komsi et al., 2008).

Belsky has proposed an interactive “process model” of parenting wherein

parent–child relationships are influenced by parent personality, child tempera-

ment, quality of marital relationship, social support, and career satisfaction

(Belsky, Rosenberger, & Crnic, 1995). Based on this theory and other similar

models, researchers have examined parent personality and child temperament as

predictors of relationship and parenting outcomes. Parent personality and child

temperament predict warmth in the parent–child relationship in adolescence

(Denissen, van Aken, & Dubas, 2009) and shared parent–child positive affect and

parental responsiveness in early childhood (Kochanska, Friesenborg, Lange, &

Martel, 2004). Anger-prone children who have optimistic mothers and fathers

high in openness receive more positive parenting (Koenig, Barry, & Kochanska,

2010), and fathers’ negative emotionality is associated with lower co-parenting

quality if their child has a difficult temperament (Laxman et al., 2013). In addi-

tion, positive parent personality traits and child effortful control are both asso-

ciated with positive dyadic child–parent interactions in 3- to 6-year-old children

(Wilson & Durbin, 2012), and positive parenting style interacts with high

effortful control to predict lower externalizing behavior problems in early ado-

lescence (Eisenberg et al., 2005).PARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT 179

With regard to direct and indirect family conflict predictors of child tempera-

ment, there have been a small number of investigations. High marital conflict has

been found to be directly associated with negative child temperaments, and low

conflict is related to positive temperament (Gharehbaghy & Vafaie, 2009).

Similar research showed that poor marital and family functioning was related to

high active-emotional temperament traits in female children (Stoneman, Brody,

& Burke, 1989). One of the few studies on this subject that used laboratory

measures of child temperament indicated that interparental conflict was indepen-

dently associated with subsequent lab-based assessments of behavioral inhibition

(Pauli-Pott & Beckmann, 2007). Children with more difficult temperaments also

have increased levels of problem behavior if they experience higher levels of

family conflict (Ramos, Guerin, Gottfried, Bathurst, & Oliver, 2005). Relatedly,

high interparental conflict and lower marital quality in the families of preschool

children with lower effortful control predicted increased problematic peer rela-

tions (David, 2009; David & Murphy, 2007). Toddler studies show that marital

hostility predicts increased levels of anger in children who experience more harsh

parenting styles (Rhoades et al., 2011), and measures of child negative reactivity,

activity level, and impulsivity are related to increased mother–toddler conflict

(Laible, Panfile, & Makariev, 2008). The general pattern of findings in these

studies illustrates that high family/interparental conflict is associated with

increased negative emotionality, activity, and lower control in children.

In addition to parent personality and family conflict, parent depression has

also been examined in the context of child temperament. Perhaps not surpris-

ingly, depressed mothers (and their partners) are more likely to perceive their

children as having a difficult temperament than nondepressed mothers and their

partners (Edhborg, Seimyr, Lundh, & Widström, 2000; Ventura & Stevenson,

1986). At least one laboratory study showed that behavioral assessments of low

positive affect in preschool were associated with a maternal history of depression

(Hayden, Klein, & Durbin, 2005). Several studies of the interactive and

moderating/mediating effects of parent depression, child temperament and

related outcomes have also been conducted. One successfully fit a model of

parent depression predicting anxiety and depression symptoms in 4-year-old

children, as mediated by parenting style and effortful control (Hopkins, Lavigne,

Gouze, LeBailly, & Bryant, 2013). Similarly, Gartstein and Fagot (2003) found

that higher levels of parental depression and more coercive/controlling parenting

style, as well as lower child effortful control, were related to externalizing behav-

iors in preschoolers. Measures of parental depressive vulnerability independent

of actual symptoms also have direct and interactive effects (across parent) on low

child effortful control (Pesonen, Räikkönen, Heinonen, Järvenpää, &

Strandberg, 2006). Finally, longitudinal models of temperamental regulation and

negative affect in infancy and parent depression status significantly predicted

depression symptoms in toddlerhood (Gartstein & Bateman, 2008).180 GAGNE ET AL.

The Current Study

A series of research questions were addressed in this paper. The overarching

goal was to examine parent- and family-level variables of depression, personality

and relationship conflict in the context of child temperament. We examined mean

gender differences for child temperament, and where appropriate, conducted

analyses that take gender into account. We predicted that significant gender

differences would be found for dimensions of child temperament that have previ-

ously shown these findings (see Gagne, Miller, & Goldsmith, 2013). For our main

analyses, we investigated how parent personality, depression and family conflict

are associated with one another, as well as with the child temperament outcomes.

In general, negative parent personality, parent depression, and family conflict were

hypothesized to be associated with negative temperament traits in children (e.g.,

anger, activity, low control). We also expected that our parent ratings of tempera-

ment would show sibling resemblance, indicating few parental contrast effects and

supporting the theory that temperament runs in families. Based on the results of

these findings and any gender differences in temperament, we then conducted

regression analyses on parent/family predictors of child temperament.

Method

Participants

Participants included 188 children assessed between 2.5 and 5.5 years of age

and their parents. The sample was derived from the Texas Family Study, an

investigation focused on the multi-method assessment of temperament, executive

functioning, and related behaviors in early childhood. All children were members

of sibling pairs, and both monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs were

included in the sample (there was also one set of triplets, which were not included

in most of the analyses). Fourteen participants were MZ twins (7 pairs), 54 were

DZ twins (27 pairs), and 116 were full siblings (58 pairs). One child that exceeded

our upper age range by at least 6 months was dropped from analyses. There were

equal numbers of male and female (94: 94) participants and their mean age was

3.72 years (SD = 1.03). Mean age for the younger siblings was 3.14 (SD = .81) and

for older siblings was 4.32 (SD = .87). The racial distribution of the children in

the sample was 81.38% White, 7.45% Black, 0.53% Asian, 9.57% more than one

race, and 1.06% other race (86.17% were non-Hispanic or Latino and 13.83%

were Hispanic or Latino). Parent respondents were 98.9% mothers (although we

had demographic data for both parents). The mean age of the mothers in our

sample was 34.01 (SD = 5.34), and the mean age of the fathers was 36.90

(SD = 6.50). Mothers were 91.5% non-Hispanic or Latino and were categorized

by race as 83% White, 7.4% Black, 2.1% Asian, 6.4% more than one race andPARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT 181

1.1% other race. Fathers were 88.3% Non-Hispanic or Latino and were identified

as 81.9% White, 9.6% Black, 1.1% Asian, 5.3% more than one race and 2.1%

other. The average family income fell in the $60,001–70,000 category, and ranged

from $20,001 to “over $200,000” (the highest response possible). The mean

number of years of schooling was 15.62 (SD = 2.33) and 15.10 (SD = 2.68) for

mothers and fathers, respectively.

Procedure

Families were enrolled by a staff of experimenters from the Department of

Psychology at the University of Texas at Arlington beginning in late 2012.

Participants were recruited through notices posted on campus, at pediatrician’s

offices, daycare centers, etc.; internet posts; and telephone contact that had been

previously solicited. Initially, participants submitted a screening online before

data collection began. Once families were approved for the study and provided

consent, one of the parents completed all questionnaires online via our secure

website using SurveyMonkey. Online questionnaire data collection has shown to

be a reliable substitute for paper-based administration (Carlbring et al., 2007;

Vallejo, Jordan, Diaz, Comeche, & Ortega, 2007), and most of our participants

subsequently participated in a laboratory visit on campus. Therefore, we were

able to verify most all family data in-person and/or through verifying email and

home addresses. There were three sets of surveys (parent and family assessment,

sibling 1 assessment, sibling 2 assessment), and upon completion the family was

compensated ($25 gift card). Only families who completed all three online surveys

were included in analyses. Data from two parent assessments of child tempera-

ment, one parent personality inventory, one parent depression inventory, and a

family conflict scale were used in the present study.

Parent Ratings of Temperament

Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ). The TBAQ

(Goldsmith, 1996) is a 120-item temperament questionnaire that contains 11

dimensional subscales of activity level, appropriate attentional allocation, inter-

est, perceptual sensitivity, sadness, anger, inhibitory control, object fear, social

fear, pleasure, and soothability. Unlike parent rating scales that use more global

items, the TBAQ employs items that describe concrete behaviors observed in

particular situations and asks the parent to rate these behaviors based on the

frequency of occurrence over the previous month. All items are formatted in a

7-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (never) to 7 (always) and includes an

“N/A” option for the rater to select if the child was not in the described situation

recently. Internal consistency reliability for the TBAQ subscales was moderate to182 GAGNE ET AL.

high, ranging from .62 to .92. with only activity level and sadness having esti-

mates under .77. Typically, TBAQ alphas meet or exceed .80; therefore, our

reliability is fairly consistent with published estimates (Goldsmith, 1996).

Parent Ratings of Parent- and Family-Level Data

Big Five Inventory (BFI). Parent ratings of their own personality were con-

ducted using the Big Five Inventory (BFI; John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991; John,

Naumann, & Soto, 2008), a self-report instrument that assesses five personality

traits of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and open-

ness. Using a 5-point scale (1 = disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly), individuals

indicate whether they agree or disagree with 44 statements about personal char-

acteristics (e.g., “likes to cooperate with others”). Published reliabilities of the

BFI scales range from .75 to .90 (John et al., 2008). In our sample, internal

consistency reliability for the BFI ranged from .76 to .86.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The CES-D

(Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses symptoms of depres-

sion experienced by the parent over the last week. CES-D items include cognitive,

emotional, behavioral, and positive affect attributes rated on a 4-point scale from

0 (rarely or none of the time/less than 1 day) to 3 (most or all of the time/5–7 days).

CES-D reliability in our sample was .83, with published internal consistencies

ranging from .84 to .90 (Radloff, 1977).

Family Conflict Scale (FCS). The Overt Hostility/O’Leary-Porter Scale

(Porter & O’Leary, 1980) was used by the parent to rate family conflict specific to

each child in the study. This is a 10-item instrument with a 5-point Likert scale

ranging from “never” to “very often.” It is designed to assess parent perception of

positive and negative family interactions displayed by partners in the presence of

the identified child. Internal consistency for this scale in our study was .74 (a

previous estimate with a sample of 65 individuals was .86).

Statistical Approach

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations. Prior to formal analyses, the

data were screened for normality as well as univariate and multivariate outliers.

CES-D depression was slightly positively skewed with two univariate outliers.

Therefore, the depression variable was transformed using the square root func-

tion and this transformed variable was used in subsequent analyses. Screening for

multivariate outliers revealed one participant who was consequently removedPARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT 183

from further analyses. Descriptive statistics, mean gender differences, and bivari-

ate correlational analyses were calculated for all variables. Mean sex differences

and correlations were corrected for the nested nature of twin/sibling data. Gen-

eralized estimating equation models were used to test for mean differences (Liang

& Zeger, 1986; Zeger & Liang, 1986), and dyad-level correlations were calculated

following procedures outlined by Griffin & Gonzalez (Griffin & Gonzalez, 1995;

O’Connor, 2004). Effect sizes of mean gender differences were also estimated as

Cohen’s d, which expresses group differences in standard deviation units.

Sibling Intraclass Correlations. Sibling intraclass correlations were calculated

for the TBAQ and the FCS using a double-entry procedure. These analyses allow

for the estimation of sibling resemblance on the various subscales of the TBAQ

and the FCS. Positive intraclass correlations reflect resemblance, zero correla-

tions reflect no resemblance, and negative correlations reflect opposing

characteristics.

Results

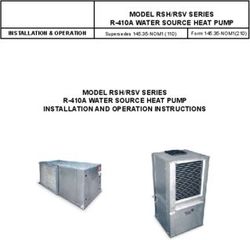

Descriptive Statistics and Mean Gender Differences

The means and standard deviations of all parent-rated TBAQ temperament

dimensions and overall FCS scores are presented in Table 1 by child gender. In

addition, the effect sizes of mean differences between male and female children

for each variable are also displayed estimated as Cohen’s d. Overall, the effect

sizes indicate that differences between males and female temperament ratings and

family conflict were low. There were no significant gender differences for the

FCS. On the TBAQ, activity, interest, anger, and inhibitory control showed the

largest differences (ranging from 26% to 40% of a standard deviation), reflecting

what is typically seen in the literature. Males had higher levels of activity and

anger, and females had higher interest and inhibitory control.

Bivariate Correlations

Correlations were calculated for both child temperament and parent person-

ality, depression and family conflict variables and are displayed in Tables 2 and

3. Correlations between the parent/family variables of family conflict, parent

personality and depression are shown in Table 2. Table 3 displays relations

between the three parent/family-level variables and child TBAQ temperament.

With regard to the parent and family variables, several interesting associations

emerged (Table 2). Parents with higher levels of neuroticism and depression

reported significantly higher levels of family conflict. More positive aspects of184 GAGNE ET AL.

Table 1

Sample Sizes, Means (and Standard Deviations), and Effect Sizes of Gender

Differences for TBAQ Temperament Dimensions, and Family Conflict

Mean males Mean females Effect size

(SD) n = 94 (SD) n = 94 of gender

TBAQ activity 4.04 (.67) 3.76 (.74) .40*

TBAQ attention 4.56 (.74) 4.66 (.80) −.13

TBAQ interest 4.39 (.79) 4.63 (.82) −.30*

TBAQ perceptual sensitivity 2.62 (.80) 2.70 (.85) −.10

TBAQ sadness 3.58 (.86) 3.67 (.76) −.11

TBAQ anger 3.60 (.99) 3.35 (.90) .26*

TBAQ inhibitory control 4.13 (.95) 4.40 (.91) −.29*

TBAQ object fear 2.49 (.80) 2.74 (.81) −.31

TBAQ pleasure 5.70 (.76) 5.70 (.71) 0

TBAQ social fear 3.03 (1.15) 3.25 (1.14) −.19

TBAQ soothability 5.20 (.83) 5.11 (.85) .11

Family conflict 1.72 (.43) 1.81 (.43) −.21

Note. Effect size estimated as Cohen’s d express group differences in standard deviation

units.

*p < .05.

Table 2

Bivariate Correlations: Parent Ratings of Personality, Family Conflict, and

Depression Symptoms

Family conflict CES-D depression

BFI extraversion −.12 −.15

BFI agreeableness −.23* −.29**

BFI conscientiousness −.21* −.18

BFI neuroticism .31** .39**

BFI openness −.04 −.11

Family conflict .26*

Note. *p < .05. **p < .01.Table 3

Bivariate Correlations: TBAQ Parent Ratings of Temperament Dimensions With Parent Ratings of Personality, Family

Conflict and Depression Symptoms

BFI BFI BFI BFI BFI Family CES-D

Extra Agree Consc Neuro Open conflict depression

TBAQ activity −.01 −.10 −.13 .17 −.07 −.00 .30**

TBAQ attention .14 .00 .20* −.15 .07 −.03 −.18*

TBAQ interest .15 .07 .13 −.13 .06 −.08 −.13

TBAQ perceptual sensitivity −.14 −.00 −.23* .19* .02 .08 .24*

TBAQ sadness −.18* −.03 −.08 .09 −.06 .02 .15

TBAQ anger −.07 .05 −.06 .07 −.15 −.09 .18*

TBAQ inhibitory control .13 −.02 .19* −.08 .13 −.03 −.20*

TBAQ object fear −.09 −.03 −.05 .09 −.03 −.03 .13

TBAQ pleasure .06 .13 .04 −.01 −.01 .03 .09

TBAQ social fear −.05 .01 .07 .04 .01 −.06 −.04

TBAQ soothability .05 .07 .10 .03 .06 −.01 −.16

Note. Extra = extraversion; Agree = agreeableness; Consc = conscientiousness; Neuro = neuroticism; Open = openness.

PARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT

*p < .05. **p < .01.

185186 GAGNE ET AL.

personality were associated with minimal or low family conflict and fewer depres-

sion symptoms. Finally, the strongest association emerged for parent depression

and neuroticism (r = .39). Generally, parents with more negative personality

traits were more depressed and experienced more conflict in front of their chil-

dren. Considering all of the parent/family variables in the context of child tem-

perament (Table 3), family conflict and parent personality showed little

consistent relationship with temperament dimensions. However, parent depres-

sion symptoms were significantly associated with TBAQ Activity, Attention,

Perceptual Sensitivity, Anger, and Inhibitory Control. The children of depressed

parents had higher levels of activity, perceptual sensitivity and anger, and lower

attention and inhibitory control.

Sibling Intraclass Correlations

Sibling intraclass correlations (Table 4) for the FCS ranged from .93 to .99,

suggesting substantial resemblance across the sibling categories of MZ and DZ

twins and full siblings for family conflict. Although the parent rated each child

separately, family conflict was almost identical across siblings in our sample. For

the TBAQ temperament dimensions, both MZ and DZ correlations were mod-

erate for all dimensions of temperament. For full siblings, intraclass correlations

for the dimensions of activity, attention, interest, pleasure, social fear, and

soothability were somewhat low, but none were negative. Therefore, both

family conflict and temperament shows some resemblance across twins and

full siblings.

Regression Analyses

We conducted a series of multiple regression analyses to explore post hoc

hypotheses of whether parent depression significantly predicted child tempera-

ment based on the results of our correlational analyses. Given that research has

shown that child temperament levels are influenced by the child’s age and gender,

these two predictors were also included in the regression analyses. Therefore,

three multiple regressions were used to examine whether parent depression, child

age, and child gender significantly predict TBAQ activity level, anger and inhibi-

tory control as outcome variables. We selected these TBAQ subscales as out-

comes because of the fact that there is consistent evidence of links between these

dimensions of temperament and important child maladjustment outcomes. A

summary of individual predictors in all regression analyses is presented in

Table 5. First, parent depression, child age, and child gender significantly pre-

dicted child anger, F(3, 184) = 10.10, p < .001, accounting for 14.14% of the

variance in anger levels. Greater parent depression significantly predictedPARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT 187

Table 4

Sibling Intraclass Correlations: TBAQ Parent Ratings of Temperament Dimen-

sions, and Family Conflict

Full

Monozygotic Dizygotic sibling

(MZ) (DZ) (FS)

twin twin intraclass

intraclass intraclass correlations

correlations correlations (n = 116,

(n = 14, (n = 54, 58 full

7 pairs) 27 pairs) pairs)

TBAQ activity .88** .64** .15

TBAQ attention .79** .36** .08

TBAQ interest .89** .26 .00

TBAQ perceptual sensitivity .86** .64** .52**

TBAQ sadness .81** .58** .22*

TBAQ anger .79** .60** .29**

TBAQ inhibitory control .93** .46** .23*

TBAQ object fear .56* .70** .22*

TBAQ pleasure .74** .66** .16

TBAQ social fear .60* .45** .06

TBAQ soothability .90** .28* .16

Family conflict .99** .93** .93**

Note. *p < .05. **p < .01.

increased child anger, while older age was significantly associated with decreased

anger. However, the child’s gender did not uniquely predict anger levels. Second,

parent depression, child age, and child gender significantly predicted child activ-

ity level, F(3, 184) = 16.95, p < .001, accounting for 21.65% of the variance in

activity levels. Greater parent depression was significantly associated with

increased activity level, while older age was significantly associated with

decreased activity level. Gender was also a significant predictor of activity level,

with boys having higher activity levels than girls. Lastly, parent depression, child

age, and child gender significantly predicted child inhibitory control, F(3,

184) = 15.44, p < .001, accounting for 20.11% of the variance in inhibition levels.

Greater parent depression was significantly associated with decreased inhibitory188 GAGNE ET AL.

Table 5

Summary Statistics for Individual Predictors in Multiple Regression Analyses

Variable B (SE) t p value sr2

TBAQ activity level

CES-D depression .20 (.04) 5.14PARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT 189

supported with subsequent regression analyses, as parent depression significantly

predicted child activity level, anger, and inhibitory control in these models. In

addition, sibling intraclass correlations showed familial resemblance for child

temperament. These findings are somewhat novel, in that parent depression

emerges as the most significant parent/family factor in predicting aspects of

temperament that are relevant to child mental health in our study (parent per-

sonality and family conflict were less significant). Sibling resemblance supports

the theory that genetic factors play an important role in the etiology of child

temperament.

Several previous investigations found significant gender differences for child

temperament dimensions (Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006;

Gagne et al., 2013), and child gender should be considered when examining

relations with other variables. In our study, gender differences for temperament

dimensions were fairly low (gender differences for family conflict experienced by

the child were not present). The temperament dimensions of activity level, anger,

interest, and inhibitory control were the only traits that showed significant sex

differences in our sample, a finding that is consistent with previous research. Boys

were rated as more active and angry, and girls were higher in interest and

inhibitory control. The effect sizes for these gender differences were similar, but

slightly lower than a twin study that focused on child temperament at age 3

(Gagne et al., 2013). Any sex differences that were present in our study informed

subsequent analyses, and our regression models included gender and age as

predictors.

The pattern of findings regarding relations across parent personality, depres-

sion, and conflict variables was consistent and as expected, parents with negative

personality attributes had increased levels of depression and family conflict, and

those with positive personality attributes showed the opposite effect. Specifically,

parents who rated themselves as more neurotic also rated themselves as signifi-

cantly more depressed (r = .39) and as displaying increased levels of conflict in the

presence of their children (r = .31). Those that judged themselves to be higher on

extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness were less depressed

and conflicted. Parents who displayed increased family conflict behaviors in front

of their children also showed significantly higher levels of depression.

When these domains of parent/family behavior were analyzed in the context

of child temperament, differential associations were found. Although several

studies have shown significant associations between the parent personality traits

of extraversion, neuroticism, and openness with child temperament outcomes

(Gartstein et al., 2013; Koenig et al., 2010; Komsi et al., 2008), we found few

consistent, significant relations between parent personality and child tempera-

ment. Similarly, at least one previous study found a direct effect of high marital

conflict on negative child temperament (Gharehbaghy & Vafaie, 2009), and

several showed family conflict to be a significant moderator between child190 GAGNE ET AL.

temperament and outcome variables like behavior problems. Family conflict was

not significantly related to any of the child temperament variables in our study.

These results may be partly due to lack of variation, or to the fact that we

examined direct effects of parent personality and family conflict on child tem-

perament, rather than more complex mediation and interaction models that seem

to be the predominant approach in other studies.

Parent ratings of their own depression symptoms did emerge as showing

significant associations with the child temperament dimensions of activity, atten-

tion, perceptual sensitivity, anger, and inhibitory control. These correlations were

fairly moderate, ranging from −.18 to .30. Parents with higher levels of depression

rated their children as having higher activity level, anger, and perceptual sensi-

tivity, and lower levels of attention and inhibitory control, indicating that parent

mental health is associated with child temperament. Based on these findings and

consistent evidence of activity level, anger and inhibitory control as important

child temperament predictors of behavior problems and psychopathology (e.g.,

Brown, 2007; Campbell & Ewing, 1990; Clark et al., 1994; Eisenberg et al., 2001;

Fagot & O’Brien, 1994; Gagne, Saudino et al., 2011; Gjone & Stevenson, 1997;

Hall et al., 1997; Schachar et al., 1995), we pursued additional regression analyses

using parent depression as a predictor and child activity level, anger, and inhibi-

tory control as outcomes. The results of our gender differences analyses and

concerns about developmental differences in temperament across age also

informed these analyses. Age and gender were included as predictors in the

regression models.

The results of our post hoc regression analyses confirm that in our sample,

parent depression is the most relevant parent/family predictor for important

areas of child temperament. Parent depression consistently and uniquely pre-

dicted child anger, activity level, and inhibitory control in these analyses. These

findings occurred in the same direction as the correlational analyses (i.e., higher

parent depression predicted higher anger). Gender effects were present for activ-

ity level only, with males showing higher activity level than females. Lastly,

developmental effects were also present in that child age was a significant pre-

dictor of all three child temperament traits. Older children had lower activity level

and anger, and higher inhibitory control. The gender and age findings are con-

sistent with the view that gender differences in temperament are common in

activity level, and older children tend to have less negative temperaments overall.

In addition to comparing parents and their children, our family study

included biologically related siblings from the same family. This allowed for the

analysis of sibling resemblance through the calculation of sibling intraclass cor-

relations. The idea that temperament is genetically influenced or biologically

based is a common thread in most contemporary theories and has been supported

by adoption, twin, and family studies (Goldsmith et al., 1987; Shiner et al., 2012).

If a trait is genetically influenced, family members who share genetic materialPARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT 191

should resemble one another. However, several studies have shown patterns of

full sibling or DZ twin correlations that are either very close to zero or negative,

suggesting that these children have opposing temperaments. This phenomenon is

a rater bias referred to as a contrast effect whereby parents overestimate differ-

ences between their children. Sibling intraclass correlations for temperament

dimensions in our family study were moderate to high for both MZ and DZ

twins. However, there were several low correlations for full siblings, suggesting

possible contrast effects. This finding is consistent with a similar sibling study of

temperament in children of the same age (Saudino, Wertz, Gagne, & Chawla,

2004). For the temperament dimensions that were associated with parent depres-

sion, full sibling correlations were positive and in most cases significant. There-

fore, parents in our study were not employing this rater bias for the child traits

that were most relevant to our research questions and analyses. Another impor-

tant issue that was addressed by these analyses is that family resemblance for

anger, activity level, and inhibitory control across siblings was present, implicat-

ing the possible role of genetic influences on these dimensions.

Our findings indicate that parent depression is meaningfully related to child

temperament. However, the use of parent ratings of temperament as the sole

strategy for assessment is somewhat limiting. A multi-method approach that

includes laboratory observations could be advantageous and has been pro-

moted by several temperament researchers (Goldsmith & Gagne, 2012). The

fact that contrast effects are not evident in the temperament domains that we

focused on is a positive sign, but our conclusions would be strengthened by

similar results employing objective behavioral data. Another limitation of our

study is that mothers were the primary respondents. Therefore, we cannot rea-

sonably interpret our findings as relating to father depression. This is typical of

most developmental research, and often researchers suggest that if mothers are

the primary caregivers and the primary respondents, the association between

maternal depression and child outcomes is most relevant. While we do not

disagree with this notion, it would be preferable to have complete depression

data for both mothers and father in our study. Lastly, our family study design

does not allow us to draw specific conclusions about the genetic and environ-

mental variance of temperament. Without sufficient numbers of MZ and DZ

twins in our sample, more sophisticated quantitative genetic analyses are simply

not possible. We do not view this as a large weakness, as many previous twin

and adoption studies have found consistent significant genetic influences on

temperament.

We view the results of this study as providing measured support for parent

depression status as being relevant to several child temperament dimensions that

are associated with mental health outcomes. The children of parents who are

depressed may be at risk for behavioral issues related to experiencing higher levels

of anger, hyperactivity, and poorer inhibitory ability. This study is not intended192 GAGNE ET AL.

to be definitive, but rather an initial contribution to research on specific contex-

tual family factors in the etiology and development of temperament. Many

temperament investigations have focused on either genetic or family environmen-

tal factors that contribute to etiology and development. Future goals for our

study include the completion of laboratory assessments of temperament and

executive functioning, DNA collection and candidate gene analysis, and

expanded child and parent mental health assessments. This data will allow for

more comprehensive multi-method and integrated gene by environment interac-

tion analyses, ultimately leading to stronger conclusions about child tempera-

ment and important health sequelae.

References

Belsky, J., Rosenberger, K., & Crnic, K. (1995). Maternal personality, marital

quality, social support and infant temperament: Their significance for infant-

mother attachment in human families. In C. R. Pryce, R. D. Martin & D.

Skuse (Eds.), Motherhood in human and nonhuman primates: Biosocial deter-

minants (pp. 115–124). (Eds.), Basel, Switzerland: Karger.

Biederman, J., Hirshfeld-Becker, D. R., Rosenbaum, J. F., Herot, C., Friedman,

D., Snidman, N., et al. (2001). Further evidence of association between

behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of

Psychiatry, 158, 1673–1679.

Brown, T. (2007). Temporal course and structural relationships among dimen-

sions of temperament and DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorder constructs.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 313–328.

Campbell, S. B., & Ewing, L. J. (1990). Follow-up of hard-to-manage preschool-

ers: Adjustments at age 9 and predictors of continuing symptoms. Child

Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 31, 871–889.

Carlbring, P., Brunt, B. S., Bohman, B. S., Austin, C. D., Richards, C. J., et al.

(2007). Internet vs. paper and pencil administration of questionnaires com-

monly used in panic/agoraphobia research. Computers in Human Behavior,

23, 1421–1434.

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development:

Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1984). Origins and evolution of behavior disorders: From

infancy to early adult life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clark, L. A., Watson, D., & Mineka, S. (1994). Temperament, personality, and

the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 103–

116.

David, K. M. (2009). Maternal reports of marital quality and preschoolers’

positive peer relations: The moderating roles of effortful control, positivePARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT 193 emotionality, and gender. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 168– 181. David, K. M., & Murphy, B. C. (2007). Interparental conflict and preschoolers’ peer relations: The moderating roles of temperament and gender. Social Development, 16, 1–23. Denissen, J. J. A., van Aken, M. A. G., & Dubas, J. S. (2009). It takes two to tango: How parents’ and adolescents’ personalities link to the quality of their mutual relationship. Developmental Psychology, 45, 928–941. Durbin, C. E. (2010). Modeling temperamental risk for depression using devel- opmentally sensitive laboratory paradigms. Child Development Perspectives, 4, 168–173. Edhborg, M., Seimyr, L., Lundh, W., & Widström, A. M. (2000). Fussy child— difficult parenthood? Comparisons between families with a “depressed” mother and nondepressed mother 2 months postpartum. Journal of Repro- ductive and Infant Psychology, 18, 225–238. Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Reiser, M., et al. (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Develop- ment, 72, 1112–1134. Eisenberg, N., Zhou, Q., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Fabes, R. A., & Liew, J. (2005). Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development, 76, 1055–1071. Else-Quest, N. M., Hyde, J. S., Goldsmith, H. H., & Van Hulle, C. A. (2006). Gender differences in temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 33–72. Fagot, B. I., & O’Brien, M. (1994). Activity level in young children: Cross-age stability, situational influences, correlates with temperament, and the percep- tion of behavior problems. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 40, 378–398. Gagne, J. R., Miller, M. M., & Goldsmith, H. H. (2013). Early—but modest— gender differences in focal aspects of childhood temperament. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 95–100. Gagne, J. R., Saudino, K. J., & Asherson, P. (2011). The genetic etiology of inhibitory control and behavior problems at 24 months of age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 1155–1163. Gagne, J. R., Van Hulle, C. A., Aksan, N., Essex, M. J., & Goldsmith, H. (2011). Deriving childhood temperament measures from emotion-eliciting behavioral episodes: Scale construction and initial validation. Psychological Assessment, 23, 337–353. Gagne, J. R., Vendlinski, M. K., & Goldsmith, H. (2009). The genetics of child- hood temperament. In Y. Kim (Ed.), Handbook of behavior genetics (pp. 251–267). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

194 GAGNE ET AL. Gartstein, M. A., & Bateman, A. E. (2008). Early manifestations of childhood depression: Influences of infant temperament and parental depressive symp- toms. Infant and Child Development, 17, 223–248. Gartstein, M. A., Bridgett, D. J., Young, B. N., Panksepp, J., & Power, T. (2013). Origins of effortful control: Infant and parent contributions. Infancy, 18, 149–183. Gartstein, M. A., & Fagot, B. I. (2003). Parental depression, parenting and family adjustment, and child effortful control: Explaining externalizing behaviors for preschool children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychol- ogy, 24, 143–177. Gharehbaghy, F., & Vafaie, M. A. (2009). Marital conflict and the role of child temperament. Journal of Iranian Psychologists, 5, 137–148. Gjone, H., & Stevenson, J. (1997). The association between internalizing and externalizing behavior in childhood and early adolescence: Genetic or envi- ronmental common influences. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25, 277–286. Goldsmith, H., Buss, A. H., Plomin, R., Rothbart, M., Thomas, A., Chess, S., et al. (1987). Roundtable: What is temperament? Four approaches. Child Development, 58, 505–529. Goldsmith, H., Lemery, K. S., & Essex, M. J. (2004). Temperament as a liability factor for childhood behavioral disorders: The concept of liability. In L. F. DiLalla (Ed.), Behavior genetics principles: Perspectives in development, per- sonality, and psychopathology (pp. 19–39). Washington, DC: American Psy- chological Association. Goldsmith, H. H. (1996). Studying temperament via construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Development, 67, 218– 235. Goldsmith, H. H., & Gagne, J. R. (2012). Behavioral assessment of temperament. In M. Zentner & R. Shiner (Eds.), Handbook of temperament (pp. 209–228). New York: Guilford Press. Goldsmith, H. H., & Hewitt, E. C. (2003). Validity of parental report of tem- perament: Distinctions and needed research. Infant Behavior & Development, 26, 108–111. Griffin, D., & Gonzalez, R. (1995). Correlational analysis of dyad-level data in the exchangeable case. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 430–439. Hall, S. J., Halperin, J. M., Schwartz, S. T., & Newcorn, J. H. (1997). Behavioral and executive functions in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disor- der and reading disability. Journal of Attention Disorders, 1, 235–247. Hayden, E. P., Klein, D. N., & Durbin, C. E. (2005). Parent reports and labo- ratory assessments of child temperament: A comparison of their associations with risk for depression and externalizing disorders. Journal of Psychopathol- ogy and Behavioral Assessment, 27, 89–100.

PARENT DEPRESSION AND CHILD TEMPERAMENT 195 Hopkins, J., Lavigne, J. V., Gouze, K. R., LeBailly, S. A., & Bryant, F. B. (2013). Multi-domain models of risk factors for depression and anxiety symptoms in preschoolers: Evidence for common and specific factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 705–722. Hwang, J., & Rothbart, M. K. (2003). Behavior genetics studies of infant tem- perament: Findings vary across parent-report instruments. Infant Behavior & Development, 26, 112–114. John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The big five inventory— Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research. John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the inte- grative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 114–158). New York, NY: Guilford Press. Kagan, J. (2001). Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral pro- files in childhood. In S. G. Hofmann & P. M. DiBartolo (Eds.), From social anxiety to social phobia: Multiple perspectives (pp. 216–234). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Karreman, A., van Tuijl, C., van Aken, M. A. G., & Deković, M. (2008). The relation between parental personality and observed parenting: The moderat- ing role of preschoolers’ effortful control. Personality and Individual Differ- ences, 44, 723–734. Kochanska, G., Friesenborg, A. E., Lange, L. A., & Martel, M. M. (2004). Parents’ personality and infants’ temperament as contributors to their emerg- ing relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 744– 759. Koenig, J. L., Barry, R. A., & Kochanska, G. (2010). Rearing difficult children: Parents’ personality and children’s proneness to anger as predictors of future parenting. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10, 258–273. Komsi, N., Räikkönen, K., Heinonen, K., Pesonen, A. K., Keskivaara, P., Järvenpää, A. L., et al. (2008). Transactional development of parent person- ality and child temperament. European Journal of Personality, 22, 553–573. Laible, D., Panfile, T., & Makariev, D. (2008). The quality and frequency of mother-toddler conflict: Links with attachment and temperament. Child Development, 79, 426–443. Laxman, D. J., Jessee, A., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Rossmiller-Giesing, W., Brown, G. L., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2013). Stability and antecedents of coparenting quality: The role of parent personality in child temperament. Infant Behavior & Development, 36, 210–222. Liang, K. Y., & Zeger, S. L. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73, 13–22.

196 GAGNE ET AL.

O’Connor, B. P. (2004). SPSS and SAS programs for addressing interdependence

and basic levels-of-analysis issues in psychological data. Behavior Research

Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 17–28.

Pauli-Pott, U., & Beckmann, D. (2007). On the association of interparental

conflict with developing behavioral inhibition and behavior problems in early

childhood. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 529–532.

Pesonen, A. K., Räikkönen, K., Heinonen, K., Järvenpää, A. L., & Strandberg,

T. E. (2006). Depressive vulnerability in parents and their 5-year-old child’s

temperament: A family system perspective. Journal of Family Psychology, 20,

648–655.

Porter, B., & O’Leary, K. D. (1980). Marital discord and childhood behavior

problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 8, 287–295.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for

research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1,

385–401.

Ramos, M. C., Guerin, D. W., Gottfried, A. W., Bathurst, K., & Oliver,

P. H. (2005). Family conflict and children’s behavior problems: The moder-

ating role of child temperament. Structural Equation Modeling, 12, 278–

298.

Rhoades, K. A., Leve, L. D., Harold, G. T., Neiderhiser, J. M., Shaw, D. S., &

Reiss, D. (2011). Longitudinal pathways from marital hostility to child anger

during toddlerhood: Genetic susceptibility and indirect effects via harsh par-

enting. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 282–291.

Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (1998). Temperament. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.),

Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, & personality development

(pp. 105–176). New York, NY: Wiley.

Saudino, K. J. (2003a). Parent ratings of infant temperament: Lessons from twin

studies. Infant Behavior & Development, 26, 100–107.

Saudino, K. J. (2003b). The need to consider contrast effects in parent-rated

temperament. Infant Behavior & Development, 26, 118–120.

Saudino, K. J., Wertz, A. E., Gagne, J. R., & Chawla, S. (2004). Night and day:

Are siblings as different in temperament as parents say they are. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 698–706.

Schachar, R., Tannock, R., Marriott, M., & Logan, G. (1995). Deficient inhibi-

tory control in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal

Child Psychology, 23, 411–437.

Seifer, R. (2003). Twin studies, biases of parents, and biases of researchers. Infant

Behavior & Development, 26, 115–117.

Shiner, R. L., Buss, K. A., McClowry, S. G., Putnam, S. P., Saudino, K. J., &

Zentner, M. (2012). What is temperament now? Assessing progress in tem-

perament research on the twenty-fifth anniversary of Goldsmith et al. Child

Development Perspectives, 6, 436–444.You can also read