LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT: STANDARDSOFMEDICALCAREIN DIABETESD2019

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

S46 Diabetes Care Volume 42, Supplement 1, January 2019

5. Lifestyle Management: American Diabetes Association

Standards of Medical Care in

Diabetesd2019

Diabetes Care 2019;42(Suppl. 1):S46–S60 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S005

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes”

includes ADA’s current clinical practice recommendations and is intended to pro-

vide the components of diabetes care, general treatment goals and guidelines,

5. LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT

and tools to evaluate quality of care. Members of the ADA Professional Practice

Committee, a multidisciplinary expert committee, are responsible for updating

the Standards of Care annually, or more frequently as warranted. For a detailed

description of ADA standards, statements, and reports, as well as the evidence-

grading system for ADA’s clinical practice recommendations, please refer to the

Standards of Care Introduction. Readers who wish to comment on the Standards

of Care are invited to do so at professional.diabetes.org/SOC.

Lifestyle management is a fundamental aspect of diabetes care and includes diabetes

self-management education and support (DSMES), medical nutrition therapy (MNT),

physical activity, smoking cessation counseling, and psychosocial care. Patients and

care providers should focus together on how to optimize lifestyle from the time of

the initial comprehensive medical evaluation, throughout all subsequent evaluations

and follow-up, and during the assessment of complications and management of co-

morbid conditions in order to enhance diabetes care.

DIABETES SELF-MANAGEMENT EDUCATION AND SUPPORT

Recommendations

5.1 In accordance with the national standards for diabetes self-management

education and support, all people with diabetes should participate in diabetes

self-management education to facilitate the knowledge, skills, and ability

necessary for diabetes self-care. Diabetes self-management support is ad-

ditionally recommended to assist with implementing and sustaining skills

and behaviors needed for ongoing self-management. B

5.2 There are four critical times to evaluate the need for diabetes self-

management education and support: at diagnosis, annually, when compli-

cating factors arise, and when transitions in care occur. E

5.3 Clinical outcomes, health status, and quality of life are key goals of diabetes

self-management education and support that should be measured as part of Suggested citation: American Diabetes Associa-

tion. 5. Lifestyle management: Standards of

routine care. C

Medical Care in Diabetesd2019. Diabetes Care

5.4 Diabetes self-management education and support should be patient cen- 2019;42(Suppl. 1):S46–S60

tered, may be given in group or individual settings or using technology, and © 2018 by the American Diabetes Association.

should be communicated with the entire diabetes care team. A Readers may use this article as long as the work is

5.5 Because diabetes self-management education and support can improve properly cited, the use is educational and not

outcomes and reduce costs B, adequate reimbursement by third-party payers for profit, and the work is not altered. More infor-

is recommended. E mation is available at http://www.diabetesjournals

.org/content/license.care.diabetesjournals.org Lifestyle Management S47

DSMES services facilitate the knowledge, 3. When new complicating factors diabetes management (BC-ADM) certifi-

skills, and abilities necessary for optimal (health conditions, physical limita- cation demonstrates specialized training

diabetes self-care and incorporate the tions, emotional factors, or basic and mastery of a specific body of knowl-

needs, goals, and life experiences of the living needs) arise that influence edge (4). Additionally, there is growing

person with diabetes. The overall objec- self-management evidence for the role of community

tives of DSMES are to support informed 4. When transitions in care occur health workers (36,37), as well as peer

decision making, self-care behaviors, (36–40) and lay leaders (41), in providing

problem-solving, and active collabora- DSMES focuses on supporting patient ongoing support.

tion with the health care team to improve empowerment by providing people with DSMES is associated with an increased

clinical outcomes, health status, and diabetes the tools to make informed self- use of primary care and preventive ser-

quality of life in a cost-effective manner management decisions (6). Diabetes care vices (18,42,43) and less frequent use of

(1). Providers are encouraged to consider has shifted to an approach that places acute care and inpatient hospital services

the burden of treatment and the pa- the person with diabetes and his or her (12). Patients who participate in DSMES

tient’s level of confidence/self-efficacy family at the center of the care model, are more likely to follow best practice

for management behaviors as well as the working in collaboration with health care treatment recommendations, particu-

level of social and family support when professionals. Patient-centered care is re- larly among the Medicare population,

providing DSMES. Patient performance spectful of and responsive to individual and have lower Medicare and insurance

of self-management behaviors, including patient preferences, needs, and values. claim costs (19,42). Despite these bene-

its effect on clinical outcomes, health It ensures that patient values guide all fits, reports indicate that only 5–7% of

status, and quality of life, as well as the decision making (7). individuals eligible for DSMES through

psychosocial factors impacting the per- Medicare or a private insurance plan

son’s self-management should be mon- Evidence for the Benefits actually receive it (44,45). This low par-

itored as part of routine clinical care. Studies have found that DSMES is asso- ticipation may be due to lack of referral or

In addition, in response to the growing ciated with improved diabetes knowl- other identified barriers such as logistical

literature that associates potentially judg- edge and self-care behaviors (8), lower issues (timing, costs) and the lack of a

mental words with increased feelings of A1C (7,9–11), lower self-reported weight perceived benefit (46). Thus, in addition

shame and guilt, providers are encouraged (12,13), improved quality of life (10,14), to educating referring providers about

to consider the impact that language has reduced all-cause mortality risk (15), the benefits of DSMES and the critical

on building therapeutic relationships and healthy coping (16,17), and reduced times to refer (1), alternative and in-

to choose positive, strength-based words health care costs (18–20). Better out- novative models of DSMES delivery

and phrases that put people first (2,3). Pa- comes were reported for DSMES inter- need to be explored and evaluated.

tient performance of self-management ventions that were over 10 h in total

behaviors as well as psychosocial factors duration (11), included ongoing support Reimbursement

impacting the person’s self-management (5,21), were culturally (22,23) and age Medicare reimburses DSMES when that

should be monitored. Please see Section appropriate (24,25), were tailored to service meets the national standards

4, “Comprehensive Medical Evaluation individual needs and preferences, and ad- (1,4) and is recognized by the American

and Assessment of Comorbidities,” for dressed psychosocial issues and incorpo- Diabetes Association (ADA) or other ap-

more on use of language. rated behavioral strategies (6,16,26,27). proval bodies. DSMES is also covered by

DSMES and the current national stan- Individual and group approaches are most health insurance plans. Ongoing

dards guiding it (1,4) are based on evi- effective (13,28,29), with a slight benefit support has been shown to be instru-

dence of benefit. Specifically, DSMES realized by those who engage in both mental for improving outcomes when it

helps people with diabetes to identify (11). Emerging evidence demonstrates is implemented after the completion of

and implement effective self-manage- the benefit of Internet-based DSMES education services. DSMES is frequently

ment strategies and cope with diabetes services for diabetes prevention and reimbursed when performed in person.

at the four critical time points (described the management of type 2 diabetes However, although DSMES can also be

below) (1). Ongoing DSMES helps people (30–32). Technology-enabled diabe- provided via phone calls and telehealth,

with diabetes to maintain effective self- tes self-management solutions improve these remote versions may not always

management throughout a lifetime of A1C most effectively when there is be reimbursed. Changes in reimburse-

diabetes as they face new challenges two-way communication between the ment policies that increase DSMES ac-

and as advances in treatment become patient and the health care team, individ- cess and utilization will result in a positive

available (5). ualized feedback, use of patient-generated impact to beneficiaries’ clinical outcomes,

Four critical time points have been health data, and education (32). Current quality of life, health care utilization, and

defined when the need for DSMES is to research supports nurses, dietitians, and costs (47).

be evaluated by the medical care pro- pharmacists as providers of DSMES who

vider and/or multidisciplinary team, with may also develop curriculum (33–35). NUTRITION THERAPY

referrals made as needed (1): Members of the DSMES team should For many individuals with diabetes, the

have specialized clinical knowledge in most challenging part of the treat-

1. At diagnosis diabetes and behavior change principles. ment plan is determining what to eat and

2. Annually for assessment of education, Certification as a certified diabetes ed- following a meal plan. There is not a one-

nutrition, and emotional needs ucator (CDE) or board certified-advanced size-fits-all eating pattern for individualsS48 Lifestyle Management Diabetes Care Volume 42, Supplement 1, January 2019

with diabetes, and meal planning should carbohydrate, protein, and fat for all peo- support one eating plan over another

be individualized. Nutrition therapy has ple with diabetes. Therefore, macronu- at this time.

an integral role in overall diabetes man- trient distribution should be based on A simple and effective approach to

agement, and each person with diabetes an individualized assessment of current glycemia and weight management em-

should be actively engaged in education, eating patterns, preferences, and meta- phasizing portion control and healthy

self-management, and treatment plan- bolic goals. Consider personal preferen- food choices should be considered for

ning with his or her health care team, ces (e.g., tradition, culture, religion, those with type 2 diabetes who are not

including the collaborative development health beliefs and goals, economics) as taking insulin, who have limited health

of an individualized eating plan (35,48). well as metabolic goals when working literacy or numeracy, or who are older

All individuals with diabetes should be with individuals to determine the best and prone to hypoglycemia (50). The

offered a referral for individualized MNT eating pattern for them (35,51,52). It is diabetes plate method is commonly

provided by a registered dietitian (RD) important that each member of the used for providing basic meal planning

who is knowledgeable and skilled in health care team be knowledgeable guidance (67) as it provides a visual guide

providing diabetes-specific MNT (49). about nutrition therapy principles for showing how to control calories (by

MNT delivered by an RD is associated people with all types of diabetes and featuring a smaller plate) and carbohy-

with A1C decreases of 1.0–1.9% for peo- be supportive of their implementation. drates (by limiting them to what fits in

ple with type 1 diabetes (50) and 0.3–2% Emphasis should be on healthful eat- one-quarter of the plate) and puts an

for people with type 2 diabetes (50). See ing patterns containing nutrient-dense emphasis on low-carbohydrate (or non-

Table 5.1 for specific nutrition recom- foods, with less focus on specific nu- starchy) vegetables.

mendations. Because of the progres- trients (53). A variety of eating patterns

sive nature of type 2 diabetes, lifestyle are acceptable for the management of Weight Management

changes alone may not be adequate to diabetes (51,54), and a referral to an RD Management and reduction of weight is

maintain euglycemia over time. How- or registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) important for people with type 1 dia-

ever, after medication is initiated, nutri- is essential to assess the overall nutrition betes, type 2 diabetes, or prediabetes

tion therapy continues to be an important status of, and to work collaboratively who have overweight or obesity. Life-

component and should be integrated with, the patient to create a personalized style intervention programs should be

with the overall treatment plan (48). meal plan that considers the individual’s intensive and have frequent follow-up

health status, skills, resources, food pref- to achieve significant reductions in ex-

Goals of Nutrition Therapy for Adults erences, and health goals to coordinate cess body weight and improve clinical

With Diabetes and align with the overall treatment indicators. There is strong and consis-

1. To promote and support healthful plan including physical activity and med- tent evidence that modest persistent

eating patterns, emphasizing a variety ication. The Mediterranean (55,56), Di- weight loss can delay the progression

of nutrient-dense foods in appropri- etary Approaches to Stop Hypertension from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes

ate portion sizes, to improve overall (DASH) (57–59), and plant-based (60,61) (51,68,69) (see Section 3 “Prevention

health and: diets are all examples of healthful eat- or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes”) and is

○ Achieve and maintain body weight ing patterns that have shown positive beneficial to the management of type

goals results in research, but individualized 2 diabetes (see Section 8 “Obesity

○ Attain individualized glycemic, meal planning should focus on per- Management for the Treatment of

blood pressure, and lipid goals sonal preferences, needs, and goals. In Type 2 Diabetes”).

○ Delay or prevent the complica- addition, research indicates that low- Studies of reduced calorie interven-

tions of diabetes carbohydrate eating plans may result in tions show reductions in A1C of 0.3%

2. To address individual nutrition needs improved glycemia and have the poten- to 2.0% in adults with type 2 diabetes,

based on personal and cultural pref- tial to reduce antihyperglycemic medi- as well as improvements in medication

erences, health literacy and numeracy, cations for individuals with type 2 doses and quality of life (50,51). Sustain-

access to healthful foods, willing- diabetes (62–64). As research studies ing weight loss can be challenging (70,71)

ness and ability to make behavioral on some low-carbohydrate eating plans but has long-term benefits; maintaining

changes, and barriers to change generally indicate challenges with long- weight loss for 5 years is associated with

3. To maintain the pleasure of eating by term sustainability, it is important to sustained improvements in A1C and lipid

providing nonjudgmental messages reassess and individualize meal plan levels (72). Weight loss can be attained

about food choices guidance regularly for those interested with lifestyle programs that achieve a

4. To provide an individual with diabe- in this approach. This meal plan is not 500–750 kcal/day energy deficit or pro-

tes the practical tools for developing recommended at this time for women vide ;1,200–1,500 kcal/day for women

healthy eating patterns rather than who are pregnant or lactating, people and 1,500–1,800 kcal/day for men,

focusing on individual macronutrients, with or at risk for disordered eating, or adjusted for the individual’s baseline

micronutrients, or single foods people who have renal disease, and it body weight. For many obese individ-

should be used with caution in patients uals with type 2 diabetes, weight loss

Eating Patterns, Macronutrient taking sodium–glucose cotransporter of at least 5% is needed to produce

Distribution, and Meal Planning 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors due to the potential beneficial outcomes in glycemic con-

Evidence suggests that there is not risk of ketoacidosis (65,66). There is in- trol, lipids, and blood pressure (70).

an ideal percentage of calories from adequate research in type 1 diabetes to It should be noted, however, that thecare.diabetesjournals.org Lifestyle Management S49

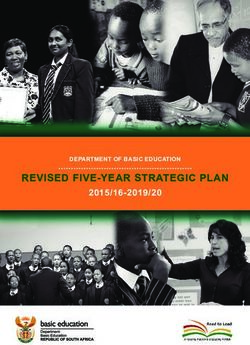

Table 5.1—Medical nutrition therapy recommendations

Topic Recommendations Evidence rating

Effectiveness of 5.6 An individualized medical nutrition therapy program as needed to achieve treatment goals, A

nutrition therapy preferably provided by a registered dietitian, is recommended for all people with type 1 or type 2

diabetes, prediabetes, and gestational diabetes mellitus.

5.7 A simple and effective approach to glycemia and weight management emphasizing portion control B

and healthy food choices may be considered for those with type 2 diabetes who are not taking insulin,

who have limited health literacy or numeracy, or who are older and prone to hypoglycemia.

5.8 Because diabetes nutrition therapy can result in cost savings B and improved outcomes (e.g., B, A, E

A1C reduction) A, medical nutrition therapy should be adequately reimbursed by insurance and

other payers. E

Energy balance 5.9 Weight loss (.5%) achievable by the combination of reduction of calorie intake and lifestyle A

modification benefits overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes and also those with

prediabetes. Intervention programs to facilitate weight loss are recommended.

Eating patterns and 5.10 There is no single ideal dietary distribution of calories among carbohydrates, fats, and proteins for E

macronutrient people with diabetes; therefore, meal plans should be individualized while keeping total calorie

distribution and metabolic goals in mind.

5.11 A variety of eating patterns are acceptable for the management of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes. B

Carbohydrates 5.12 Carbohydrate intake should emphasize nutrient-dense carbohydrate sources that are high in fiber, B

including vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, as well as dairy products.

5.13 For people with type 1 diabetes and those with type 2 diabetes who are prescribed a flexible insulin A, B

therapy program, education on how to use carbohydrate counting A and in some cases how to

consider fat and protein content B to determine mealtime insulin dosing is recommended to improve

glycemic control.

5.14 For individuals whose daily insulin dosing is fixed, a consistent pattern of carbohydrate intake with B

respect to time and amount may be recommended to improve glycemic control and reduce the risk

of hypoglycemia.

5.15 People with diabetes and those at risk are advised to avoid sugar-sweetened beverages (including B, A

fruit juices) in order to control glycemia and weight and reduce their risk for cardiovascular disease

and fatty liver B and should minimize the consumption of foods with added sugar that have the

capacity to displace healthier, more nutrient-dense food choices. A

Protein 5.16 In individuals with type 2 diabetes, ingested protein appears to increase insulin response without B

increasing plasma glucose concentrations. Therefore, carbohydrate sources high in protein should

be avoided when trying to treat or prevent hypoglycemia.

Dietary fat 5.17 Data on the ideal total dietary fat content for people with diabetes are inconclusive, so an eating B

plan emphasizing elements of a Mediterranean-style diet rich in monounsaturated and

polyunsaturated fats may be considered to improve glucose metabolism and lower cardiovascular

disease risk and can be an effective alternative to a diet low in total fat but relatively high in

carbohydrates.

5.18 Eating foods rich in long-chain n-3 fatty acids, such as fatty fish (EPA and DHA) and nuts and seeds B, A

(ALA), is recommended to prevent or treat cardiovascular disease B; however, evidence does not

support a beneficial role for the routine use of n-3 dietary supplements. A

Micronutrients and 5.19 There is no clear evidence that dietary supplementation with vitamins, minerals (such as C

herbal supplements chromium and vitamin D), herbs, or spices (such as cinnamon or aloe vera) can improve outcomes in

people with diabetes who do not have underlying deficiencies and they are not generally

recommended for glycemic control.

Alcohol 5.20 Adults with diabetes who drink alcohol should do so in moderation (no more than one drink C

per day for adult women and no more than two drinks per day for adult men).

5.21 Alcohol consumption may place people with diabetes at increased risk for hypoglycemia, especially B

if taking insulin or insulin secretagogues. Education and awareness regarding the recognition and

management of delayed hypoglycemia are warranted.

Sodium 5.22 As for the general population, people with diabetes should limit sodium consumption B

to ,2,300 mg/day.

Nonnutritive 5.23 The use of nonnutritive sweeteners may have the potential to reduce overall calorie and B

sweeteners carbohydrate intake if substituted for caloric (sugar) sweeteners and without compensation by intake

of additional calories from other food sources. For those who consume sugar-sweetened beverages

regularly, a low-calorie or nonnutritive-sweetened beverage may serve as a short-term replacement

strategy, but overall, people are encouraged to decrease both sweetened and nonnutritive-

sweetened beverages and use other alternatives, with an emphasis on water intake.

clinical benefits of weight loss are pro- on need, feasibility, and safety (73). structured weight loss plan, is strongly

gressive and more intensive weight MNT guidance from an RD/RDN with recommended.

loss goals (i.e., 15%) may be appropri- expertise in diabetes and weight man- Studies have demonstrated that a

ate to maximize benefit depending agement, throughout the course of a variety of eating plans, varying inS50 Lifestyle Management Diabetes Care Volume 42, Supplement 1, January 2019

macronutrient composition, can be used low-carbohydrate eating plans generally control (51,82,93–96). Individuals who

effectively and safely in the short term indicate challenges with long-term sus- consume meals containing more protein

(1–2 years) to achieve weight loss in tainability, it is important to reassess and fat than usual may also need to make

people with diabetes. This includes struc- and individualize meal plan guidance mealtime insulin dose adjustments to

tured low-calorie meal plans that include regularly for those interested in this compensate for delayed postprandial

meal replacements (72–74) and the approach. Providers should maintain glycemic excursions (97–99). For individ-

Mediterranean eating pattern (75) as consistent medical oversight and recog- uals on a fixed daily insulin schedule,

well as low-carbohydrate meal plans nize that certain groups are not ap- meal planning should emphasize a rela-

(62). However, no single approach has propriate for low-carbohydrate eating tively fixed carbohydrate consumption

been proven to be consistently superior plans, including women who are preg- pattern with respect to both time and

(76,77), and more data are needed to nant or lactating, children, and people amount (35).

identify and validate those meal plans who have renal disease or disordered

that are optimal with respect to long- eating behavior, and these plans should Protein

term outcomes as well as patient ac- be used with caution for those taking There is no evidence that adjusting

ceptability. The importance of providing SGLT2 inhibitors due to potential risk the daily level of protein intake (typically

guidance on an individualized meal plan of ketoacidosis (65,66). There is inade- 1–1.5 g/kg body weight/day or 15–20%

containing nutrient-dense foods, such as quate research about dietary patterns total calories) will improve health in

vegetables, fruits, legumes, dairy, lean for type 1 diabetes to support one eating individuals without diabetic kidney dis-

sources of protein (including plant-based plan over another at this time. ease, and research is inconclusive re-

sources as well as lean meats, fish, and Most individuals with diabetes report garding the ideal amount of dietary

poultry), nuts, seeds, and whole grains, a moderate intake of carbohydrate (44– protein to optimize either glycemic con-

cannot be overemphasized (77), as well 46% of total calories) (51). Efforts to trol or cardiovascular disease (CVD)

as guidance on achieving the desired en- modify habitual eating patterns are risk (84,100). Therefore, protein intake

ergy deficit (78–81). Any approach to often unsuccessful in the long term; goals should be individualized based

meal planning should be individualized people generally go back to their usual on current eating patterns. Some re-

considering the health status, personal macronutrient distribution (51). Thus, search has found successful manage-

preferences, and ability of the person the recommended approach is to in- ment of type 2 diabetes with meal

with diabetes to sustain the recommen- dividualize meal plans to meet caloric plans including slightly higher levels of

dations in the plan. goals with a macronutrient distribution protein (20–30%), which may contribute

that is more consistent with the individ- to increased satiety (58).

Carbohydrates ual’s usual intake to increase the likeli- Those with diabetic kidney disease

Studies examining the ideal amount of hood for long-term maintenance. (with albuminuria and/or reduced esti-

carbohydrate intake for people with As for all individuals in developed mated glomerular filtration rate) should

diabetes are inconclusive, although moni- countries, both children and adults aim to maintain dietary protein at the

toring carbohydrate intake and consid- with diabetes are encouraged to mini- recommended daily allowance of 0.8

ering the blood glucose response to mize intake of refined carbohydrates g/kg body weight/day. Reducing the

dietary carbohydrate are key for improv- and added sugars and instead focus amount of dietary protein below the

ing postprandial glucose control (82,83). on carbohydrates from vegetables, le- recommended daily allowance is not

The literature concerning glycemic index gumes, fruits, dairy (milk and yogurt), recommended because it does not alter

and glycemic load in individuals with di- and whole grains. The consumption of glycemic measures, cardiovascular risk

abetes is complex, often yielding mixed sugar-sweetened beverages (including measures, or the rate at which glomer-

results, though in some studies lowering fruit juices) and processed “low-fat” ular filtration rate declines (101,102).

the glycemic load of consumed carbohy- or “nonfat” food products with high In individuals with type 2 diabetes,

drates has demonstrated A1C reductions amounts of refined grains and added protein intake may enhance or increase

of 0.2% to 0.5% (84,85). Studies longer sugars is strongly discouraged (90–92). the insulin response to dietary carbohy-

than 12 weeks report no significant in- Individuals with type 1 or type 2 di- drates (103). Therefore, use of carbohy-

fluence of glycemic index or glycemic load abetes taking insulin at mealtime should drate sources high in protein (such as

independent of weight loss on A1C; how- be offered intensive and ongoing edu- milk and nuts) to treat or prevent hypo-

ever, mixed results have been reported cation on the need to couple insulin glycemia should be avoided due to the

for fasting glucose levels and endoge- administration with carbohydrate in- potential concurrent rise in endogenous

nous insulin levels. take. For people whose meal schedule or insulin.

For people with type 2 diabetes or carbohydrate consumption is variable,

prediabetes, low-carbohydrate eating regular counseling to help them under- Fats

plans show potential to improve glyce- stand the complex relationship between The ideal amount of dietary fat for in-

mia and lipid outcomes for up to 1 year carbohydrate intake and insulin needs dividuals with diabetes is controversial.

(62–64,86–89). Part of the challenge in is important. In addition, education on The National Academy of Medicine has

interpreting low-carbohydrate research using the insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios defined an acceptable macronutrient

has been due to the wide range of def- for meal planning can assist them with distribution for total fat for all adults

initions for a low-carbohydrate eating effectively modifying insulin dosing from to be 20–35% of total calorie intake (104).

plan (85,86). As research studies on meal to meal and improving glycemic The type of fats consumed is morecare.diabetesjournals.org Lifestyle Management S51

important than total amount of fat when or peripheral neuropathy (123). Routine beverage may serve as a short-term re-

looking at metabolic goals and CVD risk, supplementation with antioxidants, such placement strategy, but overall, people

and it is recommended that the per- as vitamins E and C and carotene, is not are encouraged to decrease both sweet-

centage of total calories from saturated advised due to lack of evidence of effi- ened and nonnutritive-sweetened bever-

fats should be limited (75,90,105–107). cacy and concern related to long-term ages and use other alternatives, with an

Multiple randomized controlled trials safety. In addition, there is insufficient emphasis on water intake (132).

including patients with type 2 diabetes evidence to support the routine use of

have reported that a Mediterranean- herbals and micronutrients, such as cin- PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

style eating pattern (75,108–113), rich namon (124), curcumin, vitamin D (125),

Recommendations

in polyunsaturated and monounsatu- or chromium, to improve glycemia in

5.24 Children and adolescents with

rated fats, can improve both glycemic people with diabetes (35,126). However,

type 1 or type 2 diabetes or

control and blood lipids. However, sup- for special populations, including preg-

prediabetes should engage

plements do not seem to have the nant or lactating women, older adults,

in 60 min/day or more of mod-

same effects as their whole-food coun- vegetarians, and people following very

erate- or vigorous-intensity

terparts. A systematic review concluded low-calorie or low-carbohydrate diets, a

aerobic activity, with vigor-

that dietary supplements with n-3 fatty multivitamin may be necessary.

ous muscle-strengthening and

acids did not improve glycemic con-

bone-strengthening activities at

trol in individuals with type 2 diabe- Alcohol

least 3 days/week. C

tes (84). Randomized controlled trials Moderate alcohol intake does not have

5.25 Most adults with type 1 C and

also do not support recommending n-3 major detrimental effects on long-term

type 2 B diabetes should engage

supplements for primary or secondary blood glucose control in people with

in 150 min or more of moderate-

prevention of CVD (114–118). People diabetes. Risks associated with alcohol

to-vigorous intensity aerobic ac-

with diabetes should be advised to follow consumption include hypoglycemia (par-

tivity per week, spread over at

the guidelines for the general population ticularly for those using insulin or insulin

least 3 days/week, with no more

for the recommended intakes of satu- secretagogue therapies), weight gain,

than 2 consecutive days without

rated fat, dietary cholesterol, and trans and hyperglycemia (for those consuming

activity. Shorter durations (min-

fat (90). In general, trans fats should excessive amounts) (35,126). People with

imum 75 min/week) of vigorous-

be avoided. In addition, as saturated diabetes can follow the same guidelines

intensity or interval training may

fats are progressively decreased in the as those without diabetes if they choose

be sufficient for younger and

diet, they should be replaced with un- to drink. For women, no more than one

more physically fit individuals.

saturated fats and not with refined car- drink per day, and for men, no more than

5.26 Adults with type 1 C and type 2 B

bohydrates (112). two drinks per day is recommended (one

diabetes should engage in 2–3

drink is equal to a 12-oz beer, a 5-oz glass

sessions/week of resistance ex-

Sodium of wine, or 1.5 oz of distilled spirits).

ercise on nonconsecutive days.

As for the general population, people

5.27 All adults, and particularly those

with diabetes are advised to limit their Nonnutritive Sweeteners

with type 2 diabetes, should

sodium consumption to ,2,300 mg/day For some people with diabetes who are

decrease the amount of time

(35). Restriction below 1,500 mg, even accustomed to sugar-sweetened prod-

spent in daily sedentary behav-

for those with hypertension, is gener- ucts, nonnutritive sweeteners (con-

ior. B Prolonged sitting should

ally not recommended (119–121). So- taining few or no calories) may be an

be interrupted every 30 min for

dium intake recommendations should acceptable substitute for nutritive sweet-

blood glucose benefits, partic-

take into account palatability, availabil- eners (those containing calories such as

ularly in adults with type 2 di-

ity, affordability, and the difficulty of sugar, honey, agave syrup) when con-

abetes. C

achieving low-sodium recommenda- sumed in moderation. While use of

5.28 Flexibility training and balance

tions in a nutritionally adequate diet nonnutritive sweeteners does not ap-

training are recommended 2–3

(122). pear to have a significant effect on

times/week for older adults with

glycemic control (127), they can reduce

diabetes. Yoga and tai chi may

Micronutrients and Supplements overall calorie and carbohydrate intake

be included based on individual

There continues to be no clear evidence (51). Most systematic reviews and meta-

preferences to increase flexibility,

of benefit from herbal or nonherbal analyses show benefits for nonnutritive

muscular strength, and balance. C

(i.e., vitamin or mineral) supplementation sweetener use in weight loss (128,129);

for people with diabetes without un- however, some research suggests an

derlying deficiencies (35). Metformin is association with weight gain (130). Reg- Physical activity is a general term that

associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, ulatory agencies set acceptable daily includes all movement that increases

with a recent report from the Diabetes intake levels for each nonnutritive energy use and is an important part of

Prevention Program Outcomes Study sweetener, defined as the amount that the diabetes management plan. Exercise

(DPPOS) suggesting that periodic test- can be safely consumed over a person’s is a more specific form of physical ac-

ing of vitamin B12 levels should be lifetime (35,131). For those who consume tivity that is structured and designed

considered in patients taking metfor- sugar-sweetened beverages regularly, to improve physical fitness. Both phys-

min, particularly in those with anemia a low-calorie or nonnutritive-sweetened ical activity and exercise are important.S52 Lifestyle Management Diabetes Care Volume 42, Supplement 1, January 2019

Exercise has been shown to improve 1 and type 2 diabetes and offers specific should be encouraged to reduce the

blood glucose control, reduce cardiovas- recommendation (142). amount of time spent being sedentary

cular risk factors, contribute to weight (e.g., working at a computer, watching

loss, and improve well-being (133). Phys- Exercise and Children TV) by breaking up bouts of sedentary

ical activity is as important for those with All children, including children with di- activity (.30 min) by briefly standing,

type 1 diabetes as it is for the general abetes or prediabetes, should be en- walking, or performing other light phys-

population, but its specific role in the couraged to engage in regular physical ical activities (150,151). Avoiding ex-

prevention of diabetes complications activity. Children should engage in at tended sedentary periods may help

and the management of blood glucose least 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous prevent type 2 diabetes for those at

is not as clear as it is for those with type aerobic activity every day with muscle- risk and may also aid in glycemic control

2 diabetes. A recent study suggested and bone-strengthening activities at for those with diabetes.

that the percentage of people with di- least 3 days per week (143). In general, A wide range of activities, includ-

abetes who achieved the recommended youth with type 1 diabetes benefit from ing yoga, tai chi, and other types, can

exercise level per week (150 min) var- being physically active, and an active have significant impacts on A1C, flexi-

ied by race. Objective measurement lifestyle should be recommended to all bility, muscle strength, and balance

by accelerometer showed that 44.2%, (144). Youth with type 1 diabetes who (133,152,153). Flexibility and balance

42.6%, and 65.1% of whites, African engage in more physical activity may exercises may be particularly important

Americans, and Hispanics, respectively, have better health-related quality of in older adults with diabetes to maintain

met the threshold (134). It is important life (145). range of motion, strength, and balance

for diabetes care management teams (142).

to understand the difficulty that many Frequency and Type of Physical

patients have reaching recommended Activity Physical Activity and Glycemic Control

treatment targets and to identify indi- People with diabetes should perform Clinical trials have provided strong evi-

vidualized approaches to improve goal aerobic and resistance exercise regularly dence for the A1C-lowering value of

achievement. (142). Aerobic activity bouts should ide- resistance training in older adults with

Moderate to high volumes of aerobic ally last at least 10 min, with the goal of type 2 diabetes (154) and for an additive

activity are associated with substantially ;30 min/day or more, most days of the benefit of combined aerobic and resis-

lower cardiovascular and overall mortal- week for adults with type 2 diabetes. tance exercise in adults with type 2

ity risks in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes Daily exercise, or at least not allowing diabetes (155). If not contraindicated,

(135). A recent prospective observa- more than 2 days to elapse between patients with type 2 diabetes should be

tional study of adults with type 1 diabetes exercise sessions, is recommended to encouraged to do at least two weekly

suggested that higher amounts of phys- decrease insulin resistance, regardless sessions of resistance exercise (exercise

ical activity led to reduced cardiovascular of diabetes type (146,147). Over time, with free weights or weight machines),

mortality after a mean follow-up time of activities should progress in intensity, with each session consisting of at least

11.4 years for patients with and without frequency, and/or duration to at least one set (group of consecutive repetitive

chronic kidney disease (136). Addition- 150 min/week of moderate-intensity ex- exercise motions) of five or more differ-

ally, structured exercise interventions ercise. Adults able to run at 6 miles/h ent resistance exercises involving the

of at least 8 weeks’ duration have been (9.7 km/h) for at least 25 min can benefit large muscle groups (154).

shown to lower A1C by an average of sufficiently from shorter-intensity activ- For type 1 diabetes, although exercise

0.66% in people with type 2 diabetes, even ity (75 min/week) (142). Many adults, in general is associated with improve-

without a significant change in BMI (137). including most with type 2 diabetes, ment in disease status, care needs to

There are also considerable data for the would be unable or unwilling to partic- be taken in titrating exercise with respect

health benefits (e.g., increased cardiovas- ipate in such intense exercise and should to glycemic management. Each individual

cular fitness, greater muscle strength, im- engage in moderate exercise for the with type 1 diabetes has a variable gly-

proved insulin sensitivity, etc.) of regular recommended duration. Adults with di- cemic response to exercise. This variabil-

exercise for those with type 1 diabetes abetes should engage in 2–3 sessions/ ity should be taken into consideration

(138). A recent study suggested that week of resistance exercise on noncon- when recommending the type and dura-

exercise training in type 1 diabetes secutive days (148). Although heavier tion of exercise for a given individual

may also improve several important resistance training with free weights (138).

markers such as triglyceride level, LDL, and weight machines may improve gly- Women with preexisting diabetes,

waist circumference, and body mass cemic control and strength (149), re- particularly type 2 diabetes, and those

(139). Higher levels of exercise intensity sistance training of any intensity is at risk for or presenting with gestational

are associated with greater improve- recommended to improve strength, bal- diabetes mellitus should be advised to

ments in A1C and in fitness (140). Other ance, and the ability to engage in activ- engage in regular moderate physical

benefits include slowing the decline in ities of daily living throughout the life activity prior to and during their preg-

mobility among overweight patients span. Providers and staff should help nancies as tolerated (142).

with diabetes (141). The ADA position patients set stepwise goals toward meet-

statement “Physical Activity/Exercise and ing the recommended exercise targets. Pre-exercise Evaluation

Diabetes” reviews the evidence for the Recent evidence supports that all in- As discussed more fully in Section

benefits of exercise in people with type dividuals, including those with diabetes, 10 “Cardiovascular Disease and Riskcare.diabetesjournals.org Lifestyle Management S53

Management,” the best protocol for Exercise in the Presence of Diabetic Kidney Disease

assessing asymptomatic patients with Microvascular Complications Physical activity can acutely increase uri-

diabetes for coronary artery disease re- See Section 11 “Microvascular Complica- nary albumin excretion. However, there is

mains unclear. The ADA consensus report tions and Foot Care” for more information no evidence that vigorous-intensity exer-

“Screening for Coronary Artery Disease on these long-term complications. cise increases the rate of progression of

in Patients With Diabetes” (156) con- Retinopathy diabetic kidney disease, and there appears

cluded that routine testing is not recom- If proliferative diabetic retinopathy or to be no need for specific exercise re-

mended. However, providers should severe nonproliferative diabetic retinop- strictions for people with diabetic kidney

perform a careful history, assess cardio- athy is present, then vigorous-intensity disease in general (158).

vascular risk factors, and be aware of aerobic or resistance exercise may be

the atypical presentation of coronary contraindicated because of the risk of

artery disease in patients with diabetes. SMOKING CESSATION: TOBACCO

triggering vitreous hemorrhage or ret- AND E-CIGARETTES

Certainly, high-risk patients should be inal detachment (158). Consultation

encouraged to start with short periods with an ophthalmologist prior to engag- Recommendations

of low-intensity exercise and slowly in- ing in an intense exercise regimen may 5.29 Advise all patients not to use

crease the intensity and duration as be appropriate. cigarettes and other tobacco

tolerated. Providers should assess pa- products A or e-cigarettes. B

Peripheral Neuropathy

tients for conditions that might contra- 5.30 Include smoking cessation coun-

indicate certain types of exercise or Decreased pain sensation and a higher

seling and other forms of treat-

predispose to injury, such as uncontrolled pain threshold in the extremities result

ment as a routine component

hypertension, untreated proliferative ret- in an increased risk of skin breakdown,

of diabetes care. A

inopathy, autonomic neuropathy, periph- infection, and Charcot joint destruction

eral neuropathy, and a history of foot with some forms of exercise. Therefore, a Results from epidemiological, case-control,

ulcers or Charcot foot. The patient’s age thorough assessment should be done to and cohort studies provide convincing

and previous physical activity level should ensure that neuropathy does not alter evidence to support the causal link be-

be considered. The provider should cus- kinesthetic or proprioceptive sensation tween cigarette smoking and health risks

tomize the exercise regimen to the indi- during physical activity, particularly in (163). Recent data show tobacco use is

vidual’s needs. Those with complications those with more severe neuropathy. Stud- higher among adults with chronic con-

may require a more thorough evaluation ies have shown that moderate-intensity ditions (164) as well as in adolescents

prior to beginning an exercise program walking may not lead to an increased risk and young adults with diabetes (165).

(138). of foot ulcers or reulceration in those with Smokers with diabetes (and people

peripheral neuropathy who use proper with diabetes exposed to second-hand

footwear (159). In addition, 150 min/week smoke) have a heightened risk of CVD,

Hypoglycemia

In individuals taking insulin and/or in- of moderate exercise was reported to premature death, microvascular com-

sulin secretagogues, physical activity may improve outcomes in patients with plications, and worse glycemic control

cause hypoglycemia if the medication prediabetic neuropathy (160). All indi- when compared with nonsmokers

dose or carbohydrate consumption is viduals with peripheral neuropathy (166,167). Smoking may have a role in

not altered. Individuals on these thera- should wear proper footwear and ex- the development of type 2 diabetes

pies may need to ingest some added amine their feet daily to detect lesions (168–171).

carbohydrate if pre-exercise glucose lev- early. Anyone with a foot injury or open The routine and thorough assessment

els are ,90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L), depend- sore should be restricted to non–weight- of tobacco use is essential to prevent

ing on whether they are able to lower bearing activities. smoking or encourage cessation. Nu-

insulin doses during the workout (such as Autonomic Neuropathy merous large randomized clinical trials

with an insulin pump or reduced pre- Autonomic neuropathy can increase the have demonstrated the efficacy and

exercise insulin dosage), the time of day risk of exercise-induced injury or adverse cost-effectiveness of brief counseling

exercise is done, and the intensity and events through decreased cardiac re- in smoking cessation, including the

duration of the activity (138,142). In sponsiveness to exercise, postural hy- use of telephone quit lines, in reducing

some patients, hypoglycemia after ex- potension, impaired thermoregulation, tobacco use. Pharmacologic therapy to

ercise may occur and last for several impaired night vision due to impaired assist with smoking cessation in people

hours due to increased insulin sensitiv- papillary reaction, and greater suscepti- with diabetes has been shown to be

ity. Hypoglycemia is less common in bility to hypoglycemia (161). Cardiovas- effective (172), and for the patient mo-

patients with diabetes who are not cular autonomic neuropathy is also an tivated to quit, the addition of pharma-

treated with insulin or insulin secreta- independent risk factor for cardiovascu- cologic therapy to counseling is more

gogues, and no routine preventive mea- lar death and silent myocardial ische- effective than either treatment alone

sures for hypoglycemia are usually mia (162). Therefore, individuals with (173). Special considerations should in-

advised in these cases. Intense activities diabetic autonomic neuropathy should clude assessment of level of nicotine

may actually raise blood glucose levels undergo cardiac investigation before dependence, which is associated with

instead of lowering them, especially if beginning physical activity more in- difficulty in quitting and relapse (174).

pre-exercise glucose levels are elevated tense than that to which they are Although some patients may gain weight

(157). accustomed. in the period shortly after smokingS54 Lifestyle Management Diabetes Care Volume 42, Supplement 1, January 2019

cessation (175), recent research has dem- psychological vulnerability at diagno-

disordered eating, and cogni-

onstrated that this weight gain does not sis, when their medical status changes

tive capacities using patient-

diminish the substantial CVD benefit re- (e.g., end of the honeymoon period),

appropriate standardized and

alized from smoking cessation (176). One when the need for intensified treat-

validated tools at the initial

study in smokers with newly diagnosed ment is evident, and when complica-

visit, at periodic intervals, and

type 2 diabetes found that smoking tions are discovered.

when there is a change in dis-

cessation was associated with amelio- Providers can start with informal

ease, treatment, or life circum-

ration of metabolic parameters and re- verbal inquires, for example, by asking

stance. Including caregivers and

duced blood pressure and albuminuria if there have been changes in mood

family members in this assess-

at 1 year (177). during the past 2 weeks or since the

ment is recommended. B

In recent years e-cigarettes have patient’s last visit. Providers should con-

5.34 Consider screening older adults

gained public awareness and popularity sider asking if there are new or different

(aged $65 years) with diabetes

because of perceptions that e-cigarette barriers to treatment and self-manage-

for cognitive impairment and

use is less harmful than regular cigarette ment, such as feeling overwhelmed or

depression. B

smoking (178,179). Nonsmokers should stressed by diabetes or other life stres-

be advised not to use e-cigarettes sors. Standardized and validated tools for

Please refer to the ADA position state-

(180,181). There are no rigorous studies psychosocial monitoring and assessment

ment “Psychosocial Care for People With

that have demonstrated that e-cigarettes can also be used by providers (187), with

Diabetes” for a list of assessment tools

are a healthier alternative to smoking

and additional details (187). positive findings leading to referral to a

or that e-cigarettes can facilitate smok- mental health provider specializing in

Complex environmental, social, be-

ing cessation (182). On the contrary, a diabetes for comprehensive evaluation,

havioral, and emotional factors, known

recently published pragmatic trial found diagnosis, and treatment.

as psychosocial factors, influence living

that use of e-cigarettes for smoking

with diabetes, both type 1 and type 2,

cessation was not more effective than

and achieving satisfactory medical out-

“usual care,” which included access to Diabetes Distress

comes and psychological well-being. Thus,

educational information on the health

individuals with diabetes and their fam- Recommendation

benefits of smoking cessation, strategies

ilies are challenged with complex, multi- 5.35 Routinely monitor people with

to promote cessation, and access to a

faceted issues when integrating diabetes diabetes for diabetes distress,

free text-messaging service that pro-

care into daily life. particularly when treatment tar-

vided encouragement, advice, and tips

Emotional well-being is an important gets are not met and/or at the

to facilitate smoking cessation (183). Sev-

part of diabetes care and self-management. onset of diabetes complications. B

eral organizations have called for more

Psychological and social problems can

research on the short- and long-term

impair the individual’s (188–190) or fam- Diabetes distress (DD) is very common

safety and health effects of e-cigarettes

ily’s (191) ability to carry out diabetes care and is distinct from other psychological

(184–186).

tasks and therefore potentially compro- disorders (193–195). DD refers to signif-

mise health status. There are opportu- icant negative psychological reactions

nities for the clinician to routinely assess related to emotional burdens and wor-

PSYCHOSOCIAL ISSUES

psychosocial status in a timely and effi- ries specific to an individual’s experience

Recommendations cient manner for referral to appropri- in having to manage a severe, compli-

5.31 Psychosocial care should be in- ate services. A systematic review and cated, and demanding chronic disease

tegrated with a collaborative, meta-analysis showed that psychosocial such as diabetes (194–196). The constant

patient-centered approach and interventions modestly but significantly behavioral demands (medication dos-

provided to all people with di- improved A1C (standardized mean dif- ing, frequency, and titration; monitoring

abetes, with the goals of op- ference –0.29%) and mental health blood glucose, food intake, eating pat-

timizing health outcomes and outcomes (192). However, there was a terns, and physical activity) of diabetes

health-related quality of life. A limited association between the effects

self-management and the potential or

5.32 Psychosocial screening and on A1C and mental health, and no in-

actuality of disease progression are di-

follow-up may include, but are tervention characteristics predicted

rectly associated with reports of DD

not limited to, attitudes about benefit on both outcomes.

(194). The prevalence of DD is reported

diabetes, expectations for

to be 18–45% with an incidence of

medical management and out-

Screening 38–48% over 18 months (196). In the

comes, affect or mood, general

Key opportunities for psychosocial screen- second Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and

and diabetes-related quality of

ing occur at diabetes diagnosis, during Needs (DAWN2) study, significant DD

life, available resources (finan-

regularly scheduled management vis- was reported by 45% of the participants,

cial, social, and emotional), and

its, during hospitalizations, with new but only 24% reported that their health

psychiatric history. E

onset of complications, or when prob- care teams asked them how diabetes

5.33 Providers should consider assess-

lems with glucose control, quality of affected their lives (193). High levels

ment for symptoms of diabe-

life, or self-management are identi- of DD significantly impact medication-

tes distress, depression, anxiety,

fied (1). Patients are likely to exhibit taking behaviors and are linked to highercare.diabetesjournals.org Lifestyle Management S55

Table 5.2—Situations that warrant referral of a person with diabetes to a mental health provider for evaluation and treatment

c If self-care remains impaired in a person with diabetes distress after tailored diabetes education

c If a person has a positive screen on a validated screening tool for depressive symptoms

c In the presence of symptoms or suspicions of disordered eating behavior, an eating disorder, or disrupted patterns of eating

c If intentional omission of insulin or oral medication to cause weight loss is identified

c If a person has a positive screen for anxiety or fear of hypoglycemia

c If a serious mental illness is suspected

c In youth and families with behavioral self-care difficulties, repeated hospitalizations for diabetic ketoacidosis, or significant distress

c If a person screens positive for cognitive impairment

c Declining or impaired ability to perform diabetes self-care behaviors

c Before undergoing bariatric or metabolic surgery and after surgery if assessment reveals an ongoing need for adjustment support

A1C, lower self-efficacy, and poorer di- psychological status to occur (26,193). with diabetes: a consensus report. Diabetes

etary and exercise behaviors (17,194, Providers should identify behavioral and Care 2013;36:463–470

7. Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau

196). DSMES has been shown to reduce mental health providers, ideally those

MM. Self-management education for adults

DD (17). It may be helpful to provide who are knowledgeable about diabetes with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the

counseling regarding expected diabetes- treatment and the psychosocial aspects of effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2002;

related versus generalized psychological diabetes, to whom they can refer patients. 25:1159–1171

distress at diagnosis and when disease The ADA provides a list of mental health 8. Haas L, Maryniuk M, Beck J, et al.; 2012

Standards Revision Task Force. National stan-

state or treatment changes (197). providers who have received additional

dards for diabetes self-management education

DD should be routinely monitored education in diabetes at the ADA Mental and support. Diabetes Care 2014;37(Suppl. 1):

(198) using patient-appropriate vali- Health Provider Directory (professional. S144–S153

dated measures (187). If DD is identified, diabetes.org/ada-mental-health-provider- 9. Frosch DL, Uy V, Ochoa S, Mangione CM.

the person should be referred for specific directory). Ideally, psychosocial care Evaluation of a behavior support intervention

diabetes education to address areas of providers should be embedded in di- for patients with poorly controlled diabetes.

Arch Intern Med 2011;171:2011–2017

diabetes self-care that are most relevant abetes care settings. Although the cli- 10. Cooke D, Bond R, Lawton J, et al.; U.K. NIHR

to the patient and impact clinical man- nician may not feel qualified to treat DAFNE Study Group. Structured type 1 diabetes

agement. People whose self-care re- psychological problems (200), optimizing education delivered within routine care: im-

mains impaired after tailored diabetes the patient-provider relationship as a pact on glycemic control and diabetes-specific

education should be referred by their foundation may increase the likelihood quality of life. Diabetes Care 2013;36:270–

272

care team to a behavioral health pro- of the patient accepting referral for other 11. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes

vider for evaluation and treatment. services. Collaborative care interventions self-management education for adults with

Other psychosocial issues known to and a team approach have demonstrated type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review

affect self-management and health out- efficacy in diabetes self-management, of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ

comes include attitudes about the illness, outcomes of depression, and psychoso- Couns 2016;99:926–943

12. Steinsbekk A, Rygg LØ, Lisulo M, Rise

expectations for medical management cial functioning (17,201).

MB, Fretheim A. Group based diabetes self-

and outcomes, available resources (fi- management education compared to routine

References

nancial, social, and emotional) (199), and treatment for people with type 2 diabetes mel-

1. Powers MA, Bardsley J, Cypress M, et al.

psychiatric history. For additional infor- Diabetes self-management education and sup-

litus. A systematic review with meta-analysis.

mation on psychiatric comorbidities BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:213

port in type 2 diabetes: a joint position statement

13. Deakin T, McShane CE, Cade JE, Williams RD.

(depression, anxiety, disordered eat- of the American Diabetes Association, the Amer-

Group based training for self-management

ing, and serious mental illness), please ican Association of Diabetes Educators, and the

strategies in people with type 2 diabetes mel-

refer to Section 4 “Comprehensive Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Diabetes

litus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;2:

Care 2015;38:1372–1382

Medical Evaluation and Assessment of CD003417

2. Dickinson JK, Guzman SJ, Maryniuk MD, et al. 14. Cochran J, Conn VS. Meta-analysis of qual-

Comorbidities.” The use of language in diabetes care and edu- ity of life outcomes following diabetes self-

cation. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1790–1799 management training. Diabetes Educ 2008;34:

Referral to a Mental Health Specialist 3. Dickinson JK, Maryniuk MD. Building thera- 815–823

Indications for referral to a mental health peutic relationships: choosing words that put 15. He X, Li J, Wang B, et al. Diabetes self-

specialist familiar with diabetes man- people first. Clin Diabetes 2017;35:51–54 management education reduces risk of all-cause

4. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al.; 2017 mortality in type 2 diabetes patients: a system-

agement may include positive screening Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 national atic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 2017;

for overall stress related to work-life standards for diabetes self-management edu- 55:712–731

balance, DD, diabetes management dif- cation and support. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1409– 16. Thorpe CT, Fahey LE, Johnson H, Deshpande

ficulties, depression, anxiety, disordered 1419 M, Thorpe JM, Fisher EB. Facilitating healthy

eating, and cognitive dysfunction (see 5. Tang TS, Funnell MM, Brown MB, Kurlander coping in patients with diabetes: a systematic

Table 5.2 for a complete list). It is pref- JE. Self-management support in “real-world” review. Diabetes Educ 2013;39:33–52

settings: an empowerment-based intervention. 17. Fisher L, Hessler D, Glasgow RE, et al.

erable to incorporate psychosocial assess-

Patient Educ Couns 2010;79:178–184 REDEEM: a pragmatic trial to reduce diabetes

ment and treatment into routine care 6. Marrero DG, Ard J, Delamater AM, et al. distress. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2551–2558

rather than waiting for a specific prob- Twenty-first century behavioral medicine: a con- 18. Robbins JM, Thatcher GE, Webb DA,

lem or deterioration in metabolic or text for empowering clinicians and patients Valdmanis VG. Nutritionist visits, diabetes classes,You can also read