Italy at the crossroads - CBS

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Italy at the crossroads

By

Svend E. Hougaard Jensen and Andrea Tafuro ∗

Concerns about the Italian economy appear to have evaporated under Draghi’s

leadership. However, despite enjoying a reasonably solid leadership at the moment,

Italy still remains the most fragile economy among developed countries, with a huge

public debt and low growth prospects. The recent Spring Forecast from the European

Commission helps us define the perimeter of this fragility - namely, public debt.

Currently at the order €2,500 billion, its share of GDP is set to increase to 159.8% this

year, falling only slightly in 2022 to 156.6%.

Three elements can help secure the medium-term sustainability of such a large debt.

First, a quick recovery after the pandemic, which the Commission estimates to be 4.2%

and 4.4% in 2021-2022; second, the maintenance of the low cost of public debt and

third, sustained growth in the medium-to-long term that will be able to support the

economy when the ECB and other EU governments lift the current stimuli. If Italy is

successful in reforming its economy, public debt will start falling and it will then not

constitute a problem for the rest of Europe.

Currently, however, the stability of the Italian economy – and the sustainability of its

debt – still poses a serious threat to EU and Eurozone stability. This is because it relies

on two things: the international credibility of Prime Minister, Mario Draghi – “mister

whatever it takes,” who saved the euro - and on the purchasing programmes of the

ECB - the QE–programmes (Quantitative Easing) that Draghi helped launch.

However, neither of these will last forever.

A “Greek scenario” is therefore still possible for Italy. Or even worse: a complete

default. What would happen if a large country like Italy defaulted? An Italian default

could be transmitted to the European - and global - economy through three channels:

trade, the financial market, and the Eurosystem.

∗Svend E. Hougaard Jensen, PhD, is Professor of Economics at CBS, Director of the Pension Research Centre

(PeRCent) at CBS, Member of the Systemic Risk Council and Non-Resident Fellow at Bruegel, Brussels. Andrea

Tafuro, PhD, is postdoc in the Department of Economics at CBS.

1The first is related to the depressive effects of a default that would reduce Italian

demand for goods and services from abroad, with possible global repercussions.

The second relates to the impact of an Italian default on the assets of financial

institutions: banks and other financial institutions hold sovereign bonds as assets,

because they are considered a safe investment and can be used as collateral for

operations on the market or with the central bank. If a European country, like Italy,

defaults, a share of these assets will suddenly have a value close to zero and this would

impair the solvency of many financial institutions.

Even financial institutions that do not hold Italian bonds could feel an impact because

they might hold debt or equity of banks that became insolvent. This might lead to a

generalised credit crunch, similar to the one observed in 2008, with devastating effects.

For a sense of scale, consider the collapse of Lehman Brothers, which involved assets

of just $600 billion. An Italian default would involve assets of app. €2,500 billion.

Thanks to the QE and the overall reforms introduced by the EU after the Greek crisis,

the possibility of transmission through the banking system and the financial markets

has decreased. In the case of Italy, the share of sovereign debt held by non-residents

declined from 50% before the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) to 35% in 2019.

However, this reduces only the direct effect that an Italian default will exert on

European financial institutions: the second-wave effect – the one due to the

interconnectedness of financial institutions – will still be present and can become

harmful if there is financial turmoil.

In fact, a large share of the Italian debt now appears on the ECB balance sheet, as ECB

assets, because of QE. Already before the pandemic, the Eurosystem owned about

16.5% of the total government debt of the Euro Area, with mild fluctuations across

countries, except for Greece. This implies that at the end of 2019, the Eurosystem held

about 20% of Italian debt – something like €400 billion. According to the Bank of Italy,

this amount increased in 2020 by about €150 billion, almost covering in full the extra-

deficit determined by the pandemic (about €160 billion). The Eurosystem is therefore

set to hold about 25% of Italian public debt.

2As a consequence, an Italian default would cause a large loss in the ECB balance

sheets. The possible consequences of this are controversial. Well, a central bank does

not aim at producing profits, and it can always print money “to pay its bills”. The

profits from future seigniorage may be so high that central banks are allowed to

pursue their goals even with negative capital (as has been the case with Chile and the

Czech Republic in the past). Therefore, the only effect an Italian default would have is

that Member States will receive lower dividends from the Central Banks.

However, the capital loss generated by Italy’s default might also raise concerns about

its ability to function effectively, and about its independence. This is particularly the

case if there are reasons to believe that loss will lead to present or future money

injection. Moreover, this would happen at a moment of high tension in the financial

markets and high cost of debt: we would observe something unprecedented

happening in unexplored territory. What would happen if markets convinced

themselves that the ECB cannot pursue its mandate appropriately anymore? The

consequences of such a situation can be potentially devastating.

Despite this possibility, this scenario is still unlikely. In his efforts to steer Italy into

calmer waters, Draghi is supported not only by a large parliamentary majority but by

the EU Commission, thanks to the NextGenerationEU (NGEU). This is a large package

– about €750 billion – approved by EU countries to boost EU recovery and create a

greener, more digital, and more inclusive economy. Member States need to present a

Recovery Plan to get access to these funds, in which they must specify the investments

they want to pursue and the accompanying reforms necessary to guarantee long-term

economic growth.

Italy will receive the largest share of the European funds, about €205 billion in the

period 2021-2026, of which €122.6 in the form of loans and €82.5 as grants. The country

just presented its plan, laying out how resources will be distributed. It is an ambitious

plan of reforms, with an additional fund from Italy’s own resources of about €30

billion. The plan shows three horizontal strategic priorities: Italy’s digital transition,

green transition, and social inclusion. Nearly 40% of total resources are earmarked for

3the green transition, 27% for digitalisation, and 40% for the development of the south

of the country.

The final plan is comprised of 6 missions and 16 components in the form of individual

interventions including 48 reforms and 131 investment projects. Most of these projects

are based on investments already in place or which have been already, at least

partially, financed. This is because projects financed with NGEU funds need to be

completed by a specific date, which rules out financing investments that are still on

paper. The reforms are ambitious and concern the judicial system, public

administration, legislation complexity and increased competition. The plan should

guarantee a cumulated effect on GDP, over the 6 years of about 3.6%.

All these reforms and investments go in the right direction, and they will free up the

country’s potential. However, it is difficult to say if this will be enough to get Italy

back on course. At the current stage, the plan is still a bit generic – in particular

regarding how and when the reforms will be implemented. In addition, the plan does

not present either a reform of taxation or reform of pension, which are crucial for a

country with large tax evasion, and which spends about 17% of GDP on pensions.

The feeling is that the Draghi government is well aware of the limits of its mandate.

The coalition that sustains him, despite its size, is very heterogeneous: the inclusion

of elements that might be perceived as divisive could diminish the support of some

parties. A vast coalition was necessary though, to ensure that reforms and investments

will be implemented in a country where governments do not last very long.

The recovery plan has a long phase-in of almost 6 years, and Draghi’s government

will probably not be at the helm for the entire period. It is therefore necessary that all

the major elements across the political spectrum are involved, so that they will not

backpedal on the reforms that they contributed to approving.

However, this is also Draghi’s government’s main weakness: The need to retain their

broad consensus makes it difficult to implement high impact reforms – which are

generally politically costly in the short-term. If this turns out to be the case, the NGEU

will become another lost opportunity for the Italian economy, and the probability of a

“Greek scenario” will increase.

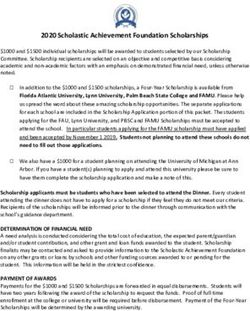

4Table 1. Forecast on Italy, 2020-2022

2020 2021 2022

Government balance -9.5% -11.7% -5.8%

Government debt 155.8% 159.8% 156.6%

Economic growth -8.9% 4.2% 4.4%

Note: The table presents the Spring Forecast for the Italian economy made by the EU commission.

Source: European Commission, April 2021

References

Archer, D. and Moser-Boehm, P., 2013. “Central bank finances”, BIS Working Paper No

71

Bruegel, 2021, “Bruegel database of sovereign bond holdings developed in Merler and Pisani-

Ferry (2012)”, Database extracted on May 2021

Buiter, W., 2008, “Can central banks go broke?”, No 6827, CEPR Discussion Papers,

C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers

Cohen-Setton, J., 2015, “Blogs review: QE and central bank solvency”, Bruegel

De Grauwe, P., and Ji Y., 2015, “Quantitative easing in the Eurozone: It's possible without

fiscal transfers”, VoxEU.org, 15 January.

European Commission, 2021, “European Economic Forecast – Spring 2021”, April

Government of Italy, 2021, “National Recovery and Resilience Plan (Piano nazionale di

Ripresa e Resilienza)”, Governo Italiano Aprile 2021

Stella, P., 1997, “Do central banks need capital?” International Monetary Fund Working

Paper No. 83, pp. 1-39.

Winkler, A., 2014, “The ECB as lender of last resort. Banks versus governments”, LSE

Financial Markets Group, Special Paper Series, February.

5You can also read