Initial learning from the government's response to the COVID-19 pandemic - Cross-government

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

A picture of the National Audit Office logo

Initial learning from the

government’s response to

the COVID-19 pandemic

Cross-government

REPORT

by the Comptroller

and Auditor General

SESSION 2021-22

19 MAY 2021

HC 66We are the UK’s We support Parliament

independent in holding government

public spending to account and we

watchdog. help improve public

services through our

high-quality audits.

The National Audit Office (NAO) scrutinises public spending

for Parliament and is independent of government and the civil

service. We help Parliament hold government to account and

we use our insights to help people who manage and govern

public bodies improve public services.

The Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG), Gareth Davies,

is an Officer of the House of Commons and leads the NAO.

We audit the financial accounts of departments and other

public bodies. We also examine and report on the value for

money of how public money has been spent.

In 2019, the NAO’s work led to a positive financial impact

through reduced costs, improved service delivery, or other

benefits to citizens, of £1.1 billion.Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Cross-government Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 17 May 2021 This report has been prepared under Section 6 of the National Audit Act 1983 for presentation to the House of Commons in accordance with Section 9 of the Act Gareth Davies Comptroller and Auditor General National Audit Office 13 May 2021 HC 66 | £10.00

Lessons learned reports

Our lessons learned reports bring together what

we know on important recurring issues to make

it easier for others to understand and apply the

lessons from our work.

The material featured in this document is subject to National Audit

Office (NAO) copyright. The material may be copied or reproduced

for non-commercial purposes only, namely reproduction for research,

private study or for limited internal circulation within an organisation

for the purpose of review.

Copying for non-commercial purposes is subject to the material

being accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement, reproduced

accurately, and not being used in a misleading context. To reproduce

NAO copyright material for any other use, you must contact

copyright@nao.org.uk. Please tell us who you are, the organisation

you represent (if any) and how and why you wish to use our material.

Please include your full contact details: name, address, telephone

number and email.

© National Audit Office 2021

Please note that the material featured in this document may not

be reproduced for commercial gain without the NAO’s express and

direct permission and that the NAO reserves its right to pursue

copyright infringement proceedings against individuals or companies

who reproduce material for commercial gain without our permission.

Links to external websites were valid at the time of publication of

this report. The National Audit Office is not responsible for the future

validity of the links.

010746 05/21 NAOContents This report can be found on the

National Audit Office website at

www.nao.org.uk

If you need a version of this

report in an alternative format

for accessibility reasons, or

any of the figures in a different

Foreword by the Comptroller format, contact the NAO at

and Auditor General 4 enquiries@nao.org.uk

Summary of learning 6

Introduction 8

Risk management 12

The National Audit Office study

team consisted of:

Transparency and public trust 16

Leon Bardot, Heather James,

Data and evidence 19 John Fellows, Pauline Ngan

and Alberto Vanzo under the

Coordination and delivery models 23 direction of Sian Jones.

Supporting and protecting people 27

Financial and workforce pressures 30

Appendix One 34

Appendix Two 37

For further information about the

National Audit Office please contact:

National Audit Office

Press Office

157–197 Buckingham Palace Road

Victoria

London

SW1W 9SP

020 7798 7400

www.nao.org.uk

If you are reading this document with a screen reader you may wish to use the bookmarks option to navigate through the parts. If @NAOorguk

you require any of the graphics in another format, we can provide this on request. Please email us at www.nao.org.uk/contact-us4 Foreword Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Foreword by the Comptroller

and Auditor General

The scale and nature of the COVID-19 pandemic The COVID-19 pandemic has stress-tested the

and the government’s response are without government’s ability to deal with unforeseen events

precedent in recent history. The pandemic continues and potential shocks. Government has often acted

to be a major challenge for government, public at unprecedented speed to respond to a virus which

sector bodies, as well as people across the UK and has caused dramatic disruption to people’s lives,

worldwide. Many people have died, and many lives public service provision and society as a whole.

have been adversely affected. The overall long-term Government had to continue to deliver essential

impact and cost of the pandemic remains uncertain public services, while reprioritising resources to

but will be substantial. deliver its response to the COVID-19 pandemic and

supporting staff to work from home. In its response,

To date, the National Audit Office (NAO) has

government has had to streamline decision-making,

published 17 reports focusing on key parts of the

work across departments and public bodies and

response where there is scope for government to

use a range of delivery structures. Departments will

learn lessons from this experience about how it does

need to reflect on the lessons learned to ensure that

and should operate. This report brings together our

they capitalise on the benefits and opportunities

initial thoughts on this learning across six themes:

these new ways of working have brought.

• risk management;

While the response to the pandemic has provided

• transparency and public trust; new learning from both what has worked well and

what has not worked well, it has also laid bare

• data and evidence; existing fault lines within society, such as the risk

of widening inequalities, and within public service

• coordination and delivery models;

delivery and government itself. The relationship

• supporting and protecting people; and between adult social care and the NHS, workforce

shortages, the challenges posed by legacy data and

• financial and workforce pressures. IT systems, and the financial pressure felt by parts

of the system all require long-term solutions.Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Foreword 5

The challenges posed by the pandemic have This report provides our initial thoughts on the

highlighted the importance for government of learning government can draw from its response to

adopting a systematic approach to preparing for date, based on fieldwork which was mostly carried

high‑impact events, evaluating its performance out in 2020. We aim to refine this thinking as we

frequently, and acting quickly on learning continue our work. Government will recognise

points while adhering to required standards of and has already acted on some of these learning

transparency and accountability even in emergencies. points, but given their importance, we reiterate

This goes beyond meeting legal (or audit) them in this report. These issues, as well as more

requirements. It involves adhering to the standards recent developments in the government’s pandemic

that government has set for itself to maintain and response, will be further explored in our future work.

strengthen public trust. Also, if government can And we will continue to draw out lessons from the

build resilience into systems and delivery chains, government’s response to the pandemic to support

and develop consistently robust horizon scanning, its own evaluation of its performance and provide

risk management and operational management Parliament and the public with timely reporting for

capabilities across government, this will help it to cope accountability and learning.

better with future emergency responses while also

improving business-as-usual activities.

Gareth Davies6 Summary of learning Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Summary of learning

We have identified learning for government from its

initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic across

six themes. Our main messages across these six

themes are set out below.

Risk management

Identifying the wide-ranging consequences of major emergencies and developing playbooks for

the most significant impacts.

Being clear about risk appetite and risk tolerance as the basis for choosing which trade-offs

should be made in emergencies.

Transparency

and public trust Being clear and transparent about what government is trying to achieve, so that it can assess

whether it is making a difference.

Meeting transparency requirements and providing clear documentation to support

decision-making, with transparency being used as a control when other measures, such as

competition, are not in place.

Producing clear and timely communications.

Data and evidence

Improving the accuracy, completeness and interoperability of key datasets and sharing them

promptly across delivery chains.

Monitoring how programmes are operating, forecasting changes in demand as far as possible,

and tackling issues arising from rapid implementation or changes in demand.

Gathering information from end-users and front-line staff more systematically to test the

effectiveness of programmes and undertake corrective action when required.Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Summary of learning 7

Coordination and

delivery models Ensuring that there is effective coordination and communication between government

departments, central and local government, and private and public sector bodies.

Clarifying responsibilities for decision-making, implementation and governance, especially where

delivery chains are complex and involve multiple actors.

Integrating health and social care and placing social care on an equal footing with the NHS.

Balancing the relative merits of central, universal offers of support against targeted local support.

Supporting and

protecting people Understanding to what extent the pandemic and government’s response have widened

inequalities, and taking action where they have.

Providing appropriate support to front-line and other key workers to cope with the physical,

mental and emotional demands of responding to the pandemic.

Financial and

workforce Placing the NHS and local government on a sustainable footing, to improve their ability to

pressures respond to future emergencies.

Ensuring that existing systems can respond effectively and flexibly to emergencies, including

provision for spare or additional capacity and redeploying staff where needed.

Considering which COVID-19-related spending commitments are likely to be retained

for the long term, and what these additional spending commitments mean for long-term

financial sustainability.8 Introduction Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Introduction

1 In May 2020, the National Audit Office (NAO) 2 The NAO’s reports on the government’s

published its first report on the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic cover many

response to the pandemic, an Overview of the of the key programmes, such as the employment

UK government’s response to the COVID-19 support schemes (the Coronavirus Job Retention

pandemic. We noted that this report would help Scheme and the Self-Employment Income Support

identify a risk‑based series of descriptive and Scheme), the Bounce Back Loan Scheme, NHS Test

evaluative reports where government faced and Trace, and the supply of personal protective

particular challenges and there was most to learn. equipment, as well as more cross-cutting themes

Since then we have published a further 16 reports such as procurement during the pandemic and

on the government’s response to the COVID-19 local government finance. A full list of our reports

pandemic, as well as regularly updating the is provided in Appendix One and a list of the

estimated costs of the government’s response recommendations from these reports is provided

on our website.1 in Appendix Two. By the end of April 2021, the

Committee of Public Accounts had held sessions on

16 out of the 17 reports we published. Appendix One

also provides a list of the Committee’s COVID-19

reports that had been published by 1 May 2021.

1 All of the reports are available on the dedicated COVID-19 section

of our website at: www.nao.org.uk/about-us/covid-19/ and the cost

tracker is available at: www.nao.org.uk/covid-19/cost-tracker/Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Introduction 9

3 By the end of March 2021, the estimated 4 This report draws out learning from the reports

lifetime cost of measures announced as part that we have published to date, as well as other

of the government’s response was £372 billion work we have published that covered the COVID-19

(Figure 1 on page 10). The largest programmes, pandemic, such as our good practice guides on

by estimated lifetime cost, are the Coronavirus Job fraud and error and operational delivery,2 our report

Retention Scheme (£62 billion), NHS Test and Trace on The adult social care market in England,3 and our

(£38 billion) and self-employment income support Departmental Overview 2019-20: Department for

(£27 billion). Figure 2 on page 11 highlights the Work & Pensions.4 It sets out this learning across

estimated lifetime costs by lead department, with the six themes:

highest-spending departments being HM Revenue

& Customs (£111 billion), the Department of Health • risk management;

& Social Care (£92 billion) and the Department for • transparency and public trust;

Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (£59 billion).

• data and evidence;

• coordination and delivery models;

• supporting and protecting people; and

• financial and workforce pressures.

We will continue to draw out learning from the

government’s response to the pandemic from

our future work.

2 National Audit Office, Good practice guidance: Fraud and error,

March 2021, available at: www.nao.org.uk/report/good-practice-

guidance-fraud-and-error/ and National Audit Office, Improving

operational delivery in government: A good practice guide for senior

leaders, March 2021, available at: www.nao.org.uk/report/managing-

operations-senior-leaders-guide/

3 Comptroller and Auditor General, The adult social care market in

England, Session 2019–2021, HC 1244, March 2021, available at:

www.nao.org.uk/report/adult-social-care-markets/

4 National Audit Office, Departmental Overview 2019-20:

Department for Work & Pensions, October 2020, available at:

www.nao.org.uk/report/departmental-overview-2019-20-department-

for-work-pensions/10 Introduction Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

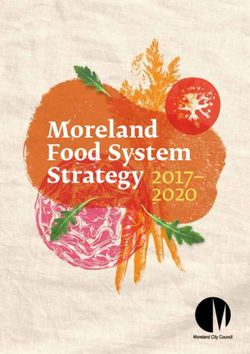

Figure 1

Breakdown of the estimated lifetime costs of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

by programme, March 2021

The programmes highlighted in this diagram accounted for 79% of the estimated cost of the government’s response announced up to

31 March 2021

Coronavirus

Job Retention

Scheme

VAT measures4 NHS Test

£62bn and Trace

£10bn

£38bn

Vaccines

£10bn Self-employment

income support

£27bn

Universal Credit

£10bn

Total estimated

lifetime cost Devolved administrations

Further health £372bn £26bn

services spend

£14bn

Bounce Back Loan Scheme

Business grant funding 3 £23bn

£18bn

Business rates measures

Rail and bus measures £21bn

£18bn

Personal protective equipment

£18bn

Support for businesses

Support for health and social care

Support for individuals

Support for other public services and emergency responses

Notes

1 Figures are rounded to the nearest billion.

2 The area of each bubble is proportional to the estimated cost of the programme.

3 Business grant funding includes the Closed Business Lockdown Payment, the Innovate UK Business Support Package, the Retail, Hospitality

and Leisure Grant Fund and the Small Business Grant Fund.

4 VAT measures include reduced VAT rates and VAT deferrals, except for the temporary VAT zero rate on personal protective equipment, which

has been included in the personal protective equipment measures.

5 The programmes shown in this diagram account for £294 billion of the estimated lifetime costs of the government’s response. The remaining

cost (£78 billion) relates to support for individuals, businesses, health and social care, and other public services and emergency responses.

Source: National Audit Office COVID-19 cost trackerInitial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Introduction 11

Figure 2

Breakdown of the estimated lifetime costs of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

by lead department, March 2021

HM Revenue & Customs, the Department of Health & Social Care and the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy

accounted for 70% of the estimated costs of the government’s response announced up to 31 March 2021

HM Revenue

& Customs

£111bn

Other lead departments

£12bn Department of

Health & Social Care

£92bn

Ministry of Housing,

Communities &

Local Government Total estimated

£11bn lifetime cost

£372bn

Department for Business,

Energy & Industrial Strategy

£59bn

Department for Transport

£18bn

HM Treasury

Department for

£46bn

Work & Pensions

£21bn

Notes

1 Figures are rounded to the nearest billion.

2 The area of each bubble is proportional to the estimated cost response by each lead department.

3 Spend on responses may not appear in a lead department’s accounts. For example, HM Treasury is the lead department for support

to the devolved administrations (£26 billion). However, these items appear in the accounts of other government departments.

Source: National Audit Office COVID-19 cost tracker12 Risk management Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Risk management

5 The government’s response to the COVID-19

Learning pandemic aims to protect people from exposure

to the virus, ensure that those infected are cared

for and mitigate damage to the economy. As well

Identifying the wide‑ranging as ongoing risks, such as those related to exiting

consequences of major the EU, government has had to manage the risks

emergencies and generated by the pandemic and the risks associated

developing playbooks for the with its own response measures. The pandemic and

most significant impacts. government’s response so far have highlighted the

importance of carrying out robust risk planning and

being clear about risk appetite and risk tolerance as

Being clear about

the basis for choosing which trade-offs should be

risk appetite and risk made in emergencies.

tolerance as the basis for

choosing which trade-offs should be

Risk planning

made in emergencies.

Identifying the wide-ranging

consequences of major emergencies

and developing playbooks for the

most significant impacts.

6 Government lacked a playbook for many

aspects of its response. For example, pre-existing

pandemic contingency planning did not include

detailed plans for:

• identifying and supporting a large population

advised to shield. The testing of plans and

policies for the identification and shielding of

clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV) people

were not objectives of Exercise Cygnus, an

exercise carried out in 2016 to assess the UK’s

preparedness for an influenza pandemic;Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Risk management 13

• managing mass disruption to schooling on the

Key facts from our published work scale caused by COVID-19. The Department

for Education’s emergency response function

19 was designed to manage disruptions due to

localised events such as floods.

Ministerial directions

published in 2020 No playbook can cover all the specific circumstances

of every potential crisis. Nevertheless, more detailed

planning for the key impacts of a pandemic and

35% to 60% of other high-impact low-likelihood events can

improve government’s ability to respond to future

Estimated percentage of loans emergencies. It may also bring other benefits,

such as creating new relationships and improving

from the Bounce Back Loans

understanding between organisations.

Scheme that may not be repaid

Risk appetite and trade-offs from

5% to 10% acting quickly

Being clear about risk appetite

HM Revenue & Customs’

and risk tolerance as the basis for

planning assumption for the

choosing which trade-offs should

percentage of payments from

be made in emergencies.

the Coronavirus Job Retention

Scheme that were due to

fraud and error 7 Once the scale of the COVID-19 outbreak in

the UK became apparent, the government made

several rapid, large-scale spending decisions and

• employment support schemes. Instead, implemented some measures at pace. For example,

HM Treasury and HM Revenue & Customs the food box deliveries for CEV people were up and

(HMRC) told us they drew on economic running within days of being announced. In a matter

contingency planning designed for financial of weeks, personal protective equipment (PPE) and

rescues, developed following the credit crisis; ventilator procurement were set up, employment

draft policy work on wage subsidy schemes; support and business loan schemes were up and

and lessons learned from other countries, such running, and the campaigns to house rough sleepers

as Germany; and deliver school meal vouchers were designed

and implemented. Government was also quick

• financial support to local authorities, such as to announce unringfenced funding (£3.2 billion

mechanisms for compensating authorities between March 2020 and April 2020) to help local

for a fall in income. The Ministry of Housing, authorities address the financial pressures caused

Communities & Local Government (MHCLG) by the pandemic.

told us it had stress-tested its response to an

economic shock as part of its contingency

planning. However, the economic impact of

the pandemic exceeded the economic shock

assumed for this stress-testing; and14 Risk management Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

8 To enable speed of action, government relaxed • The Department for Business, Energy &

controls and streamlined spending approvals, Industrial Strategy (BEIS), in conjunction with

recognising that this would lead to an increased risk the British Business Bank (the Bank), has

of fraud and error: estimated that between 35% and 60% of

loans from the Bounce Back Loans Scheme

• In designing employment support schemes,

may not be repaid, and this represents both

HMRC acknowledged that it would need to

credit and fraud risks. In March 2021, the

make certain trade-offs between its normal

estimated value of these loans was between

approach of preventing as much fraud and

£16 billion and £27 billion based on loans

error as possible and ensuring grants reached

to date. BEIS and the Bank are working on

claimants quickly. HMRC drew up longlists

estimating what proportion is due to fraud.

of potential controls for both schemes. In

total it identified 42 potential controls for the • By January 2021, the Department of Health &

Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS), Social Care (DHSC) had spent £10.2 billion on

of which 24 were implemented by the go-live PPE, with an estimated lifetime cost of around

date and 57 for the Self-Employment Income £15.2 billion. The Government Counter Fraud

Support Scheme (SEISS), of which 38 were Function has assessed a high risk of fraud

delivered by the end of April 2020. HMRC’s in the procurement of PPE. DHSC has yet to

planning assumptions were that between estimate the size of this potential fraud.

5% and 10% of payments from the CJRS

While some controls were relaxed, the overall

and between 1% and 2% of payments from

framework set out in Managing Public Money has

the SEISS were due to fraud and error. In

remained in place throughout the pandemic as the

September 2020, this amounted to between

basis on which accounting officers should make

£2 billion and £3.9 billion for the CJRS and

decisions to ensure that public funds are used in

between £130 million and £270 million for

the public interest.

the SEISS.

9 Government accepted other trade-offs from

• The number of Universal Credit claimants

acting quickly, such as paying higher prices for

roughly doubled in 2020 and the Department

goods than it would have paid before the pandemic.

for Work & Pensions (DWP) suspended some

For example, DHSC experienced increasing global

controls such as face-to-face appointments

competition to buy ventilators and made purchases

to support vulnerable people during lockdown

primarily on the offer’s credibility, not price. It also

and manage demand. Of Universal Credit

paid high prices for PPE because of the global surge

payments, £1.7 billion (9.4%) were overpaid in

in demand for these goods and export restrictions in

2019-20 before COVID-19. DWP accepts that

some countries.

the increased caseload and easements made

to the process of applying for benefits will lead

to a further increase in fraud and error levels.

Post publication this page was found to contain an error which has been corrected (Please find Published Correction Slip)Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Risk management 15

10 Government focused on getting some

Figure 3

programmes up and running quickly, recognising

Ministerial directions published in 2020

that they may need to be amended as they went.

For instance, due to limitations in the datasets

available, initially some 870,000 CEV people were 10 COVID-19-related,

at least partly on

value-for-money

identified centrally as eligible for support to help

grounds

them shield. A further 420,000 were identified

as eligible by 12 April 2020 and another 900,000

people by 7 May 2020. When the Bounce Back

Loan Scheme was launched on 4 May 2020

4 COVID-19-related

on other grounds

(for example, breach

(seven days after it was announced), the Bank of spending limits)

had a reporting portal for lenders, but this

5

required manual data entry for each application. Not related

An automatic reporting functionality was introduced to COVID-19

in mid-June 2020. Governance arrangements of

some programmes were also redesigned during Notes

the response (for example, see paragraph 30). 1 Six ministerial directions were published in 2019 (four on

value-for-money grounds).

2 The total does not include the Prime Minister’s Personal Minute

11 Some departments made good use of issued to the Cabinet Office Permanent Secretary on 28 June 2020

ministerial directions to proceed with programmes to authorise an exit payment.

where they lacked assurance over value for money. 3 The ministerial directions have been categorised by the National Audit

Office. The categorisation has not been agreed with HM Treasury.

Due to the speed at which programmes were being

implemented, accounting officers could not gain Source: National Audit Office analysis of GOV.UK data

assurance over the value for money of several

COVID-19 response measures. These included the

Bounce Back Loan Scheme, the Local Authority

Discretionary Grants Fund and the Retail, Hospitality

and Leisure Business Grants Fund. As prescribed by

Managing Public Money, some accounting officers

obtained directions from ministers to proceed with

these programmes. In 2020, 19 ministerial directions

were published, compared with an average of five

per year between 2017 and 2019 (Figure 3).5

5 Ministerial directions are formal instructions from ministers telling

their department to proceed with a spending proposal, despite an

objection from their permanent secretary. Permanent secretaries, who

are directly accountable to Parliament for how the department spends

its money, have a duty to seek a ministerial direction if they think a

spending proposal breaches any of the following criteria: regularity

(if the proposal is beyond the department’s legal powers, or agreed

spending budgets); propriety (if it does not meet “high standards of

public conduct”, such as appropriate governance or parliamentary

expectations); value for money (if something else, or doing nothing,

would be cheaper and better); and feasibility (if there is doubt about

the proposal being “implemented accurately, sustainably or to the

intended timetable”).16 Transparency and public trust Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Transparency and public trust

12 In responding to a new virus and global

Learning pandemic, government faced exceptionally

challenging circumstances. The public sector

has needed to respond in unprecedented ways

Being clear and transparent while seeking to maintain and build public trust.

about what government is Central to this is setting clear objectives, being

trying to achieve, so that transparent about what actions were taken and

it can assess whether it is making why, the trade‑offs being made, and providing clear,

a difference. consistent and timely communications.

Objectives

Meeting transparency

requirements and providing Being clear and transparent about

clear documentation to what government is trying to achieve,

support decision-making, so that it can assess whether it is

with transparency being used as a making a difference.

control when other measures, such

as competition, are not in place.

13 Detailed objectives help to ensure that

the success of programmes can be measured.

Producing clear and For example, HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC)

timely communications. agreed clear principles for its employment support

schemes, including that the claim process should

be simple and the grant calculation straightforward.

Although the Bounce Back Loans Scheme achieved

its initial objective of quickly supporting small

businesses, a lack of more detailed scheme‑specific

objectives will make it difficult to measure its

ultimate success.Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Transparency and public trust 17

Key facts from our published work Evidence to support decision-making

148 Meeting transparency requirements

and providing clear documentation

to support decision-making, with

New guidance documents and

transparency being used as a control

updates to existing material

when other measures, such as

published by the Department competition, are not in place.

for Education between

16 March and 1 May 2020

14 Transparency, including a clear audit trail to

support key decisions, is a vital control to ensure

25% accountability, especially when government is having

to act at pace and other controls (for example,

Percentage of contracts competitive tendering) are not in place. On the

with a value over £25,000 ventilator programmes, we found sufficient record

awarded in response to the of the programmes’ rationale, the key spending

decisions taken, and the information departments

pandemic up to 31 July 2020

had to base those on. However, in the procurement of

where the contract awards

personal protective equipment (PPE) and other goods

were published within the

and services using emergency direct awards during

90-day target the pandemic, we and the Government Internal

Audit Agency found that there was not always a

0.07% clear audit trail to support key decisions, such as

why some suppliers which had low due diligence

ratings were awarded contracts. HMRC initially

Spend on communication as

ruled out publishing the details of every company

a percentage of government’s

claiming furlough payments, which might have

expected total investment in

alerted some employees that their employer was

purchasing and manufacturing acting fraudulently.

COVID-19 vaccines for

the UK, deploying them in 15 We found that many of the contracts awarded

England and supporting global during the pandemic had not been published

efforts to find vaccines as at on time. Of the 1,644 contracts awarded across

government up to the end of July 2020 with a

8 December 2020 (£8 million

contract value above £25,000, 75% were not

out of £11,702 million)

published on Contracts Finder within the 90-day

target and 55% had not had their details published

by 10 November 2020. The Cabinet Office and

DHSC acknowledged the backlog of contract details

awaiting publication and noted that resources

were now being devoted to this, having earlier

been prioritised on ensuring procurements were

processed so that goods and services could be

made available for the pandemic response.18 Transparency and public trust Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

17 Communications from government were not

Communications and public engagement always clear and timely. For example:

Producing clear and • guidance on PPE (issued jointly by DHSC,

timely communications. Public Health England and NHS England &

NHS Improvement) changed 30 times up to

31 July 2020, including material and relatively

minor changes. While frequent updates were

16 Effective communication and public

needed to reflect an increased understanding

engagement are crucial to ensuring that COVID-19

of a new virus and a rapidly changing policy

response programmes succeed. Effective

position, social care representatives raised

communication helps achieve policy objectives

concerns about the guidance, including that the

and strengthens public trust by helping the public

frequency of changes made it confusing; and

understand what the government is doing, why,

and what it means for them and their communities. • the Department for Education calculated

that, between 16 March and 1 May 2020, it

• In our work, we found examples of effective,

published 148 new guidance documents and

clear and consistent communications.

updates to existing material. Stakeholders told

For instance, HMRC developed a range of

us that guidance was often published at the

communication and engagement plans for

end of the week or late in the evening, putting

its employment support schemes. It notified

schools under pressure, especially when

self-assessment taxpayers that they may have

guidance was for immediate implementation.

been eligible for the Self-Employment Income

When the guidance was updated, schools were

Support Scheme, reached out to some of the

not always clear what changes had been made.

largest employers to check if they intended

to apply for the Coronavirus Job Retention

Scheme, and worked with ethnic minority

and faith‑based organisations to publicise

the schemes.

• Despite government advertising and

communications relating to NHS Test and

Trace, reported levels of non‑compliance with

self-isolation requirements were high.

• DHSC has acknowledged variation in the

public’s perception of COVID-19 vaccines,

with some groups more hesitant than others.

Designing effective targeted communications

will be important if the optimum level of

vaccine take-up is to be achieved.Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Data and evidence 19

Data and evidence

18 The insight generated through reliable data

Learning is crucial to the way government delivers services

for citizens, improves its systems and processes,

and makes decisions. Our work has repeatedly

Improving the accuracy, emphasised the importance of evidence-based

completeness and decision-making at all levels of government

interoperability of key activity and the problems that arise when data are

datasets and sharing them promptly inadequate. The pandemic has again highlighted

across delivery chains. the role of high-quality data in enabling effective

service delivery, monitoring and improvement.

It has generated new datasets and data collection

Monitoring how programmes processes that can be used to inform future

are operating, forecasting service delivery.

changes in demand as far as

possible, and tackling issues arising Accuracy, completeness and sharing

from rapid implementation or changes of data

in demand.

Improving the accuracy,

completeness and interoperability

Gathering information from

of key datasets and sharing them

end-users and front-line

promptly across delivery chains.

staff more systematically

to test the effectiveness of

programmes and undertake corrective 19 Timely sharing of data has been vital for

action when required. providing front-line services and managing the

response at the national level. For instance, while

the Department of Health & Social Care (DHSC) and

the Cabinet Office ran their programmes to increase

the number of ventilators separately, they worked

toward the same overall targets and exchanged

progress data daily. The Ministry of Housing,

Communities & Local Government (MHCLG)

introduced a monthly survey of cost pressures and

income losses experienced by local authorities

due to the pandemic. Despite some data quality

issues, it provided an important dataset that several

departments have used to shape their responses.20 Data and evidence Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

20 However, timely sharing of data has not always

Key facts from our published work occurred, and legacy IT issues remain challenging:

95% • NHS Test and Trace (NHST&T) publishes a

large volume of data every week which helps

understand the progress of COVID-19 and

Proportion of Self-Employment tracing performance (Figure 4). However, local

Income Support Scheme authorities did not initially have access to all

claimants who were satisfied the NHST&T data they needed to deliver their

or very satisfied with their local pandemic response.

experience up to August 2020

• By 22 March, when shielding was

announced, 870,000 people had been

815,000 identified centrally as clinically extremely

vulnerable (CEV). It took three weeks to identify

Number of clinically extremely and communicate with a further 420,000 CEV

vulnerable people whose people. This was largely down to the challenge

details were passed to local of extracting usable data from different NHS

authorities to check if these and GP IT systems.

people needed help

Figure 4

375,000

Estimated number of people in England

infected with COVID-19, receiving positive tests,

transferred to the tracing service and reached

Number of clinically

by NHS Test and Trace

extremely vulnerable

people who were sent People with COVID-19

1,943,000

letters advising them to (estimated)

shield but did not receive a

follow-up call due to missing Tested positive by

44%

NHS Test and Trace

or inaccurate telephone

numbers provided in Transferred

39%

NHS patient records to tracing

Successfully

32%

traced

Note

1 Data relate to the period from 28 May 2020 to 4 November 2020.

Source: Comptroller and Auditor General, The government’s approach

to test and trace in England – interim reportInitial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Data and evidence 21

21 In responding to the pandemic, government

has expanded the range of data that it can use for Monitoring performance, flexing

decision-making. For example, MHCLG now has government’s response and

data on the potential scale of the population in forecasting demand

England which either sleeps rough or is at risk of

doing so. At the start of the outbreak, there was no Monitoring how programmes are

systematic national process to collect a wide range operating, forecasting changes

of information from care providers, other than on in demand as far as possible, and

vacant beds (for instance, on levels of personal tackling issues arising from rapid

protective equipment and workforce absences). implementation or changes in demand.

For care homes, a tool commissioned by NHS

England & NHS Improvement (NHSE&I) in 2019 23 Government has been able to take remedial

was adapted and expanded, and data have been action to address some issues arising from rapid

collated since early April 2020. Government has implementation, and improve performance.

also taken steps to improve the quality of its data. For example, the Department for Education and its

For example, NHST&T received advice from the contractor acted quickly to solve initial problems

Office for National Statistics and a rapid review by experienced by schools and families on its free

the UK Statistics Authority. school meal voucher scheme. This resulted in

improved performance. In terms of vaccines,

22 Limitations in the accuracy and completeness

NHSE&I has had to continually review and adapt its

of the data used and collected by government

deployment plans to ensure it could respond to the

have affected some pandemic response measures.

latest information about which vaccines had been

For example, NHSE&I sent letters to all those advised

approved, which groups in society needed to be

to shield. However, missing or inaccurate telephone

vaccinated, how many doses of vaccines would be

numbers within NHS patient records meant that the

available, and when and how those vaccines needed

shielding programme could not follow up these letters

to be deployed. The Department for Digital, Culture,

with calls to some 375,000 CEV people. While it was

Media & Sport adjusted elements of its response to

known to all parties that a proportion of telephone

take account of the pandemic’s progression and the

numbers in NHS records were missing or inaccurate,

impact it has had on the arts and culture sector.

the shielding programme agreed to use telephone

numbers from NHS records as a starting point to

follow up hard-copy letters. The Government Digital

Service shared with local authorities the contact

details of people that could not be reached, so local

authorities could check if these people needed help.

Local authorities also struggled with inaccurate

contact information.22 Data and evidence Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

24 Data limitations affected the government’s • The staff utilisation rate for contact tracers

ability to assess the effectiveness and value for fell to under 1% in August 2020. NHST&T

money of some measures, which made it harder was initially unable to reduce staffing levels

to adapt its response and manage the risks of to meet its target utilisation rate of 50% due

rapid implementation: to lack of flexibility in contracts. The utilisation

rate then rose, ranging between 10% and

• MHCLG attempted to collect data from local

56% in October 2020.

authorities on basic care provision for CEV

people but was unable to identify a workable • NHST&T did not predict the scale of

solution acceptable to local authorities by increased demand for COVID-19 testing

the end of July 2020, when the programme in September 2020, when schools and

ended. Local authorities reported that bringing universities reopened, and could not satisfy the

together data on basic support provided by a demand for tests until mid-September 2020.

mix of local authority and voluntary groups was

too burdensome. In the absence of these data, Validating interventions by gathering

MHCLG accepted that it had some assurance end‑user feedback

that local authorities were meeting basic needs

given that local authorities had provided similar Gathering information from

support for a number of years. Its engagement end-users and front-line staff

with local authorities also gave it some more systematically to test the

assurance that they were meeting basic needs. effectiveness of programmes

and undertake corrective action

• While HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) monitored

when required.

the take-up rate of the Self‑Employment Income

Support Scheme among different age and

gender profiles, it does not have data to 26 Gathering feedback from end-users and

monitor take-up rates among different ethnic front-line staff is essential for monitoring the

groups, as these data are not necessary for effectiveness of interventions and improving

the administration of taxes. existing processes. For example, HMRC carried out

surveys of employers, employees and self-employed

25 Government’s ability to forecast changes

people who accessed the employment support

in demand, and to update programmes based on

schemes. The high satisfaction scores recorded

updated demand, has been variable:

gave HMRC confidence that it was delivering a good

• During March 2020, in response to changes customer experience to claimants. On the other

in planning assumptions approved by the hand, while NHS provider organisations told us they

Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, were always able to get the PPE needed in time, this

NHSE&I revised down its estimate of the was not the experience reported by some front-

peak number of ventilator beds that could be line workers, particularly Black, Asian and minority

needed. In April, based on the lower demand, ethnic staff. Public Health England’s stakeholder

ministers adopted new targets for the ventilator engagement to better understand the impact of

programme to provide additional resilience COVID-19 on Black, Asian and minority ethnic

in the system and prepare for a potential groups reported deep concerns about the support

second wave. that these workers in health and care settings

received, stating that “it was recognised that a lot

has been done since the start of the pandemic

to improve access to PPE and mitigate risk, but

concerns were expressed that these safeguards

were not applied equally across ethnic groups”.Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Coordination and delivery models 23

Coordination and delivery models

27 The pandemic response has involved

Learning extensive coordination between departments,

arm’s-length bodies, local and national government,

and public‑private collaboration. Delivery chains

Ensuring that there is have often been complex and involved multiple

effective coordination and actors. Against this backdrop, setting out effective

communication between governance arrangements, with clear responsibilities

government departments, central and accountabilities, is vital to delivering outcomes.

and local government, and private

and public sector bodies. Cross-government coordination and

public-private collaboration

Clarifying responsibilities

Ensuring that there is effective

for decision-making, coordination and communication

implementation and between government departments,

governance, especially where central and local government, and

delivery chains are complex private and public sector bodies.

and involve multiple actors.

28 The pandemic response involved examples

Integrating health and social of effective cross-government and public-private

care and placing social care sector collaboration:

on an equal footing with

the NHS.

• Policy and operational staff at HM Revenue

& Customs (HMRC) and HM Treasury (HMT)

worked closely to develop the employment

Balancing the relative merits support schemes, with HMT leading on policy

design and HMRC leading on administrative

of central, universal offers

design, implementation and administration.

of support against targeted

local support. • The Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local

Government’s (MHCLG’s) initial engagement

with local authorities on supporting clinically

extremely vulnerable people to shield was

directive rather than consultative. It recognised

that it needed to improve engagement with

local authorities and moved to a collaborative

approach. The small number of local authorities

we spoke to criticised government’s engagement

with them in the first few weeks of the initiative,

with some noting that engagement improved

over summer.24 Coordination and delivery models Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Key facts from our published work Figure 5

Organisations involved in purchasing,

17 manufacturing and deploying vaccines in England

Access to vaccines and manufacturing capability

Lead departments involved

in the COVID-19 response Prime Minister • Overall direction and strategy

which had an estimated Vaccine • Identifying vaccines, securing access

Taskforce

lifetime response cost of • Developing manufacturing capacity

more than £1 million, as of • Enhacing ability to deliver rapid

clinical trials

end of March 2021

Pharmaceutical • Developing and manufacturing vaccines

companies

More than 7 Deploying vaccines

Joint Committee • Advising on priority groups for vaccination

Organisations involved in on Vaccination

an Immunisation

purchasing, manufacturing

and deploying vaccines Medicines and • Approving vaccines for use

Healthcare

in England products

Regulatory

Agency

4.7m NHS England

& Improvement

•

•

Operational delivery of the deployment

Administering vaccines

Number of food boxes delivered Public Health • Storing and distributing vaccines

to clinically extremely vulnerable England

• Supplying other goods

people between 27 March and (for example, syringes)

1 August 2020 through private

Source: Comptroller and Auditor General, Investigation into preparations

sector contracts for potential COVID-19 vaccines

• The Cabinet Office worked with industry to

develop new, or modify existing, ventilator or Responsibilities for decision-making,

anaesthesia machine designs to meet standards implementation and governance

that the Medicines and Healthcare products

Clarifying responsibilities for

Regulatory Agency developed for rapidly

decision-making, implementation

manufactured ventilators, and to increase

and governance, especially where

manufacturing capacity to build each design at

delivery chains are complex

a much greater scale than usual. This involved

and involve multiple actors.

securing new factory capacity for each design,

managing global supply chains and ensuring

regulatory approvals were in place.

• The purchase, manufacturing and deployment of

vaccines involves extensive cross-government

and public-private collaboration (Figure 5).Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic Coordination and delivery models 25

29 Effective governance and clear responsibilities

and accountabilities are important for an effective The relation between health and

rapid response in an emergency. For example, the social care

Department for Work & Pension’s (DWP’s) clear

Integrating health and social care and

prioritisation of paying benefits and suspension

placing social care on an equal footing

of other activities enabled it to process an

with the NHS.

unprecedented number of claims during the first

lockdown. This was supported by clear governance

within DWP. On the other hand, we found that several 31 Issues predating the pandemic made

organisations had responsibility for approving, responding to the crisis more difficult in some areas.

maintaining and distributing personal protective The relationship between adult social care and the

equipment (PPE) from the pandemic influenza NHS has been challenging for decades. We have

stockpile. There were issues with warehousing, reported on successive efforts to integrate the

logistics and quality of stock. two sectors: there have been 12 government white

papers, green papers and consultations, and five

30 Government has modified the independent reviews on integration over the past

governance arrangements of key pandemic 20 years. Certain aspects of the initial pandemic

response programmes: response reflected a greater emphasis on health

than on social care. For example, national bodies

• NHS Test and Trace (NHST&T) initially had an

initially provided more PPE support to hospitals

unusual organisational relationship with the

than to social care. NHS trusts received 80% of

Department of Health & Social Care (DHSC).

their estimated PPE requirement through national

Although NHST&T was subject to DHSC’s

schemes between 20 March 2020 and 31 July

financial, information and staffing controls, its

2020, whereas social care providers received

head, the executive chair, did not report to the

10% of their estimated requirement (based on

DHSC’s ministers or permanent secretary, but

the information available at the time).6 DHSC told

rather to the Prime Minister and the Cabinet

us that it took different approaches to providing

Secretary. Since NHST&T is embedded within

PPE to social care and trusts during the pandemic.

DHSC, these dual reporting lines brought risks

Social care providers, which are mostly private- or

of unclear accountability. We did not undertake

voluntary‑sector organisations, either obtained PPE

a systematic review to determine if these risks

from wholesalers (as they did prior to the pandemic)

had materialised and had seen no evidence

or from local resilience forums and DHSC’s helpline,

that they had.

which it set up to respond to emergency requests,

• In September 2020, a faster process whereas trusts received PPE directly from the

for approving vaccines expenditure was cross‑government PPE team set up by DHSC.

introduced by government and the governance

for vaccines activities was revised. DHSC

appointed a single senior responsible officer

to oversee deployment to create a unified

programme to reduce duplication, streamline

responsibilities, facilitate cross-departmental

working, and increase transparency

and accountability.

6 Distributions to trusts include a very small volume of PPE delivered to

other healthcare settings.26 Coordination and delivery models Initial learning from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic

32 In responding to the pandemic, DHSC • in May 2020, the government launched NHST&T,

has increased its focus on social care. DHSC bringing together a national programme

outlined how, under the current Care Act 2014, for testing and tracing. By July 2020, local

its oversight of the social care market had been authorities had started to set up their own

limited. Stakeholders reported DHSC’s limited locally run contact tracing schemes to cover

engagement with, and understanding of, the sector the minority of cases that the national service

going into the pandemic. Prior to COVID-19 there could not reach, working in conjunction with

was no process in place to collect a wide range NHST&T. In August, NHST&T reduced the

of data from providers regularly. In response to number of national-level contact tracers and

COVID-19, DHSC has increased the data it obtains designated a proportion of its specialist tracing

on care providers and it intends to legislate for staff to work exclusively to facilitate those local

new powers to collect further data. As part of its authorities that had their own scheme. By the

adult social care winter plan, DHSC carried out a end of October, 40% (60) of local authorities

review of risks to local care markets and service had a scheme in place, with a further 46% (69)

continuity issues, offering targeted support. It also planning to set one up; and

re-established a director‑general post with sole

responsibility for social care, increased its policy • while the Culture Recovery Fund accepted

applications from across England, one of its

team threefold and set up specific teams to provide

goals was to help ‘level up’ cultural resources

support and challenge to local government on the

for deprived communities. This was reflected

COVID-19 response.

in the funding criteria. An analysis by the

Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport

Central and local delivery models found that the 10% of local authorities most

in need of levelling up were more successful in

Balancing the relative merits of central,

their grant applications than those least in need.

universal offers of support against

targeted local support. 34 Universal offers of support can be developed

at speed but may not always be as cost-effective

as targeted offers. A government review of the

33 Pandemic response measures have employed

shielding programme concluded that, due to

a combination of universal offers and targeted

the speed and context in which the programme

delivery models. For instance:

was developed, it was largely offered universally,

• the Everyone In campaign was rolled out across resulting in poor targeting and inefficient use of

England to provide accommodation for all rough funds. The review noted that, should shielding

sleepers. For the winter of 2020, the campaign be needed again, adopting a local support model

was supplemented with a targeted programme could improve flexibility and, potentially, be more

focused on the areas with large numbers of cost-effective.

rough sleepers;You can also read