How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

CREATE Research Archive Published Articles & Papers 2012 How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making Robin Dillon-Merrill Georgetown University, rld9@georgetown.edu Catherine H. Tinsley Georgetown University, tinsleyc@georgetown.edu Matthew A. Cronin George Mason University, mcronin@gmu.edu Follow this and additional works at: http://research.create.usc.edu/published_papers Recommended Citation Dillon-Merrill, Robin; Tinsley, Catherine H.; and Cronin, Matthew A., "How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making" (2012). Published Articles & Papers. Paper 93. http://research.create.usc.edu/published_papers/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CREATE Research Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Published Articles & Papers by an authorized administrator of CREATE Research Archive. For more information, please contact gribben@usc.edu.

Published online ahead of print April 18, 2012

MANAGEMENT SCIENCE

Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18

ISSN 0025-1909 (print) ISSN 1526-5501 (online) http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1517

© 2012 INFORMS

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

How Near-Miss Events Amplify or

Attenuate Risky Decision Making

Catherine H. Tinsley, Robin L. Dillon

McDonough School of Business, Georgetown University, Washington, DC 20057

{tinsleyc@georgetown.edu, rld9@georgetown.edu}

Matthew A. Cronin

School of Management, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia 22030, mcronin@gmu.edu

I n the aftermath of many natural and man-made disasters, people often wonder why those affected were

underprepared, especially when the disaster was the result of known or regularly occurring hazards (e.g.,

hurricanes). We study one contributing factor: prior near-miss experiences. Near misses are events that have

some nontrivial expectation of ending in disaster but, by chance, do not. We demonstrate that when near misses

are interpreted as disasters that did not occur, people illegitimately underestimate the danger of subsequent

hazardous situations and make riskier decisions (e.g., choosing not to engage in mitigation activities for the

potential hazard). On the other hand, if near misses can be recognized and interpreted as disasters that almost

happened, this will counter the basic “near-miss” effect and encourage more mitigation. We illustrate the robust-

ness of this pattern across populations with varying levels of real expertise with hazards and different hazard

contexts (household evacuation for a hurricane, Caribbean cruises during hurricane season, and deep-water oil

drilling). We conclude with ideas to help people manage and communicate about risk.

Key words: near miss; risk; decision making; natural disasters; organizational hazards; hurricanes; oil spills

History: Received June 29, 2010; accepted November 27, 2011, by Teck Ho, decision analysis. Published online

in Articles in Advance.

Introduction When people escape an impending disaster by

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the public and chance, they have experienced a “near miss.” More

media alike questioned why so many people failed precisely, a near miss is an event that has some non-

to evacuate the Gulf Coast and why the government trivial expectation of ending in disaster but because of

and first-responder organizations were so appallingly luck did not (Reason 1997, Dillon and Tinsley 2008).1

underprepared (Glasser and Grunwald 2005). The rea- Our natural environment produces many examples

sons for these failures are often rooted in experiences of near misses: a random tree pattern saves a house

with previous hurricanes. In the lead-up to the storm, from a mud slide or a hurricane weakens right before

Governor Haley Barbour of Mississippi warned of it hits a city. Organizations experience near misses

“hurricane fatigue”—the possibility that his constit- as well. For example, in the deep-sea oil drilling

uents would not evacuate because they had success- industry, dozens of Gulf of Mexico wells in the past

fully weathered earlier storms; similarly, one former

two decades suffered minor blowouts during cement-

Federal Emergency Management Agency official said

ing; however, in each case chance factors (e.g., favor-

people in the agency unfortunately approached the

able wind direction, no one welding near the leak at

Katrina response as it had other responses, though the

aftermath of Katrina was clearly “unusual” (Glasser the time, etc.) helped prevent an explosion (Tinsley

and Grunwald 2005). Such complacency is not exclu- et al. 2011).

sive to hurricanes. Citizens who survive natural disas- We study how prior near misses influence peoples’

ters in one season often fail to take actions that would interpretation of similar hazards and thus influence

mitigate their risk in future seasons (e.g., moving off future mitigation decisions. We do this in multiple

a Midwestern flood plain or clearing brush to prevent contexts: a single household threatened by hurricane,

wildfires in the West; see Lindell and Perry 2000). Our

research demonstrates that people may be complacent 1

Other events have been labeled “near misses” such as last minute

because prior experience with a hazard can subcon-

heroic efforts to avert crisis or interventions of chance that cause

sciously bias their mental representation of the hazard bad rather than good outcomes (e.g., narrowly missing an air-

in a way that often (but not always) promotes unre- plane departure). Thus we specify our focus here on near misses

alistic reassurance. as chance-dependent good outcomes.

1Tinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

2 Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS

a planned Caribbean cruise threatened by a hurri- causing major flooding and wind damage. This infor-

cane, and oil-rig operations threatened by a danger- mation provides input to assessing probabilities and

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

ous storm. We explain why and when a near miss outcomes, but it also cues the retrieval of other

produces complacency versus action and offer pre- information that will be used to refine these esti-

scriptions for risk communication strategies based on mates and their relationship to each other. Krizan and

how different types of near misses operate. Windschitl (2007) provide a useful conceptualization

of this knowledge retrieval process: given a situation

How Near Misses Influence involving risk, people must assess what this infor-

mation means in light of what they already know.

Cognitive Processes “What they already know” is the domain knowl-

When facing an imminent hazard, people should

edge Gonzalez and Wu (1999) spoke of as modify-

assess the risk, which is technically a function of the

ing assessments of probabilities and outcomes and

probability of the event occurring and the harm that

their combination. To select which domain of knowl-

results from the event if it occurs (Kaplan and Garrick

edge to use, people can use the cognitive category to

1981, von Neumann and Morgenstern 1944). This is

the classic subjective expected utility (SEU) model. which a hazard event belongs (Kahneman and Miller

For example, to decide whether or not to evacuate 1986). “Hurricane” represents a category of events

for an impending hurricane, people should combine that guides the retrieval of relevant knowledge from

assessments of the likelihood of their location being memory. So although an avalanche is also a hazard,

hit by the hurricane and how bad the damage could knowledge about avalanches would not be retrieved

be. Such assessments make use of the information based on the hurricane category (although knowledge

at hand, but people also bring past personal experi- of flooding, which is related to hurricanes, might).

ences into their evaluation of the risk (Fishbein and Near misses come into play in that they can modify

Azjen 2010, Tierney et al. 2001). We show that a par- the hazard category, because prior experiences with

ticular type of personal experience, near misses, have an event can alter the cognitive category for that event

an undue influence on how people evaluate risk and (Kahneman and Miller 1986). Thus, after a near miss,

can lead to questionable choices when people face an the knowledge people will use in assessing SEU com-

impending hazard with which they have had prior ponents for a future hazard will change. This explains

near-miss experience. We show that this near-miss why prior outcomes can strongly influence future

effect is robust because it seems to implicitly influ- decisions and realized outcomes tend to be seen as

ence the thoughts people use as inputs to their deci- deterministic (Hastie and Dawes 2001).

sion making. This near-miss effect can be countered, The chain of events we posit is as follows:

but doing so needs to use the same kind of implicit (1) upon encountering a hazard, people retrieve rel-

mechanism. evant knowledge from memory about that hazard,

Although an SEU model provides a strong basis for a process that is largely implicit (Anderson 1983, 1993;

characterizing how people decide to respond to haz- Kahneman and Miller 1986) but results in assessments

ards, past research (Gonzalez and Wu 1999, Tversky of probabilities, outcomes, and how they will be com-

and Fox 1995) has shown that the model compo- bined; (2) an explicit evaluation of the risk of the haz-

nents (including the likelihood estimates for probabil- ard is made largely using an SEU framework; and

ity, (un)attractiveness estimates for outcomes, and the (3) once the risk is evaluated, people must explicitly

ways in which these can be combined into an eval- choose what behavior to engage. In the next section,

uation of risk) can vary based on characteristics of we hypothesize how near misses influence this chain

the situation such as whether the likelihood estimates of events.

are very large, moderate, or very small (Tversky and

Fox 1995). More importantly for the present work, Hypotheses

Gonzalez and Wu (1999) demonstrated that SEU can Dillon and Tinsley (2008) found that near misses

vary both between and within individuals (i.e., the in completing a space project encouraged people to

same person may be risk averse in one situation and choose a riskier strategy when faced with a future

risk seeking in another) because the components are hazard threat to the mission. Although highly contex-

all sensitive to the domain knowledge people use tualized and specific, their research showed that near

when evaluating the risky event. misses are events that alter evaluations of risk, and

We argue that near misses change the domain thus a near-miss bias should generalize to many kinds

knowledge (or cognitive category) that people use in of hazards and be relevant to a large array of natu-

their assessment of the SEU components, and thus ral and man-made hazard environments. Near-miss

can bias the judgments people make about risky sit- events in the hazard context often highlight resiliency

uations. For example, people may learn that a hur- because people escape harm. For example, imagine

ricane has a 50% chance of striking their town and that a hurricane is being tracked in the Caribbean andTinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS 3

is a concern to two neighborhoods, A and B. Peo- to our scenario, imagine there is another neighbor-

ple in both neighborhoods rely on existing domain hood C next to neighborhood B who also experienced

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

knowledge to direct their thinking about the risk the hurricane. Because neighborhood C was closer to

of this situation and whether or not to take protec- the center of the storm, neighborhood C was hit with

tive action. Assume that as the storm grows nearer, a stronger force, and their sandbag levees collapsed,

it becomes clear that the hurricane will miss neigh- resulting in significant flooding. For the people of

borhood A, but neighborhood B is still in danger, neighborhood B, seeing damage to neighborhood C

and they create a sandbag levee around the main further modifies the basic near-miss information (“we

city buildings. Fortunately, when the hurricane makes were ok, but look what happened to them”) to alter

landfall, the storm surge subsides before overtopping the hurricane category away from resilience. With the

B’s makeshift levee, and the town suffers no damage. stimulus of damage to a neighboring town, they may

In this illustration, neighborhood A did not experi- encode that the disaster almost caused harm, and that

ence a near miss because there was no expectation they were vulnerable to possible damage.

of harm. Neighborhood B experiences a near miss If the near-miss effect operates through mostly

because there was a nontrivial expectation that the implicit processes, then we expect that counteracting

flooding could occur, but for good fortune (i.e., chance the near-miss effect will require further modification

storm characteristics) it did not. We argue that the of the hazard category (Kahneman and Miller 1986).

near-miss event experienced by people of neighbor- When the near-miss experience also highlights the

hood B will change the hurricane category knowledge harm the event could have caused, it adds informa-

in a way that when facing a new hazard warning, tion to counteract the basic resilient near-miss effect;

the domain knowledge retrieved will make the haz- that is, the near miss (no harm done) can alter the cat-

ard seems less threatening, leading to complacency. egory to make the hazard seem less threatening, but

Thus, near misses that emphasize resiliency will lead new harm information counteracts this with associa-

to riskier behavior. tions of vulnerability. In our illustration, the people

Hypothesis 1 (H1). People with near-miss information from neighborhood B would now encode informa-

that highlights how a disaster did not happen will be less tion about both resilience (from the absence of dam-

likely to take mitigating action for an impending hazard age) and potential harm (a neighboring town was

than people without this information. severely flooded). When facing a warning about a

future impending hurricane, people from neighbor-

The process we have described for how near misses hood B should now be less swayed by the fact that

work (change to the category knowledge) does not they escaped harm.

restrict the direction in which the category may be

modified. Near-miss experiences do have some plas- Hypothesis 2 (H2). People with vulnerable near-miss

ticity in their interpretation. For example, in their dis- information (that highlights how an event almost caused

cussion of aviation near misses, March et al. (1991, harm) will be more likely to take mitigating action for

p. 10) essentially argue that near collisions can pro- an impending hazard than people with resilient near-miss

duce two different types of salient associations. They information.

describe: How the new hazard is evaluated will depend on

Every time a pilot avoids a collision, the event provides the category knowledge retrieved, which in turn is

evidence both for the threat [of a collision] and for its dependent on how the prior near miss modified the

irrelevance. It is not clear whether the 0 0 0 organization hazard category. Moreover, this modification could

came [close] to a disaster 0 0 0 or that the disaster was produce different assessments of probabilities (P ),

avoided. outcomes (O), or risk (R) because the information

If people experience the near miss as a disas- about the particular hazard that is embedded in the

ter that almost happened rather than a disaster that warning will be integrated with domain knowledge

was avoided, then their hazard category should be about the hazard category, thereby influencing some

associated with vulnerability. We distinguish these part of the SEU model (P , O, and/or R).

“vulnerable” near misses (wherein a disaster almost We predict that near misses change the negativ-

happened and results in the perceived vulnerability ity associated with a bad event rather than chang-

of the system) from “resilient” near misses (wherein ing probability assessments. This is consistent with

a disaster could have but did not happen and results Windschitl and Chambers’ (2004) finding that people

in the perceived resilience of the system).2 Returning are more likely to change their feelings about a choice

than their explicit beliefs about the probabilities. Fur-

2

See also Kahneman and Varey (1990) for arguments on the critical thermore, in the domain of near misses, Dillon and

distinction between an event that did not occur and an event that Tinsley (2008) showed that people changed their per-

did not but almost occurred. ceptions of risk without changing their probabilities.Tinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

4 Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS

Depending on the type of near miss (resilient or to justify their choice (i.e., reverse causality). Study 6

vulnerable), the valence of the information retrieved corroborated the findings of Studies 2–5 with actual

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

should change, influencing risk estimates. As the risk behavior by having participants’ decisions regarding

estimates change, so should the resulting judgments a risky situation have financial consequences for their

about what to do for an impending hazard. compensation.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Resilient near misses will decrease

Study 1

one’s feelings of risk more than vulnerable near misses

This study provides evidence of the near-miss effect

without changing perceived probabilities, and these feelings

in actual hazard situations. It is well established that

of risk will mediate the corresponding behavioral response.

people’s mitigation decisions, evacuation in the case

of hurricanes, are influenced by what relevant oth-

Overview of Studies ers do (Tierney et al. 2001). We tested whether or not

Our hypotheses were tested across multiple stud- prior near-miss experiences reduce evacuation behav-

ies, where we sought different types of respondents ior beyond what is due to social cues and a house-

and used different threats and contexts to demon- hold’s specific geographic location (proximity to coast

strate that our effects are robust across various pop- and waterways). This speaks to the importance of the

ulations and decisions. Study 1 looked for evidence effect (i.e., it is not overwhelmed by people’s incli-

of the near-miss effect using a field survey of house- nation to do what their neighbors do), and why it

holds in coastal counties of Louisiana and Texas warrants further study.

who experienced Hurricane Lili.3 We examined how Participants and Procedure. In the spring of 2003,

previous storm experience as well as prior near- six months after Hurricane Lili hit the Louisiana

miss experiences (in the form of unnecessary evac- coastline, 1,000 households from five affected areas

uations) influenced whether or not the individuals (200 each area: Vermilion and Cameron Parishes in

surveyed evacuated for Hurricane Lili. Studies 2–6 Louisiana and Orange, Jefferson, and Chambers coun-

used the laboratory to discover how the near-miss ties in Texas) were randomly selected and mailed a

phenomenon operates. Study 2 examined how encod- survey by the Hazard Reduction and Recovery Cen-

ing near misses as resilient or vulnerable led to dif- ter at Texas A&M asking whether they had evacu-

ferent evacuation rates for a hypothetical hurricane ated. For the storm, the National Hurricane Center

and demonstrated that the addition of vulnerability had issued a hurricane warning, and local officials

information to the near-miss stimulus can counteract had issued an early evacuation advisory in these five

the complacency effect. Study 3 examined the compo- areas. A total of 507 usable surveys were returned for

nents of people’s SEU assessments. It probed people’s a response rate of 50.7%, which exceeds similar hur-

assessments of probabilities (P ), outcome attractive- ricane studies (Prater et al. 2000, Lindell et al. 2001).4

ness (O), and their ultimate judgments of risk versus To obtain this response rate, nonresponsive house-

safety (R) to test our hypothesized mediation. Study holds were sent a follow-up survey every three weeks

4 generalizes our basic finding by changing the con- (until a total of three surveys had been sent).

text from a house to a cruise ship; in doing so we Variables. Respondents were asked (on a 1–5 scale,

address a concern that participants may be updating where 1 equaled “not at all” and 5 equaled “very

their calculations of the risk after a resilient near miss. great extent”) whether or not they had “previous

Additionally, in Study 4, we examine the role coun- experience with an unnecessary evacuation.” This

terfactuals have in the risky decision. Study 5 offered was our proxy for a resilient near miss (i.e., where

evidence that near misses do in fact change the hazard a disaster did not happen), which was treated as

category, and hence the knowledge associated with

the independent variable. For the dependent variable,

a hazard, by examining what participants’ thought

respondents were asked whether or not they evacu-

about a hazardous situation. This study removed the

ated. For control variables, respondents were asked

need to make a decision, thereby (a) providing evi-

(on a 1–5 scale, where 1 equaled “not at all” and 5

dence for the first (implicit) step in our sequence of

equaled “very great extent”) about individual geo-

how near misses affect cognitive processes and (b)

graphic proximity including how close they lived to

discounting a concern that people first chose what to

the coast and how close they lived to inland water

do and then, when forced to answer questions, gen-

such as bays, bayous, or rivers. Also on the same

erate assessments of probabilities, outcomes, and risk

1–5 scale, respondents were asked about social cues

including whether they saw businesses closing; saw

3

The survey was conducted six months after Hurricane Lili by the

Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center at Texas A&M. Hurricane

4

Lili was the deadliest and costliest hurricane of the 2002 Atlantic See Lindell et al. (2005) for more details of the original survey

hurricane season. collection.Tinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS 5

friends, relatives, neighbors, or coworkers evacuat- this study was to provide empirical evidence beyond

ing; heard announcement of a hurricane warning; the post hoc evaluations of highly visible disasters

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

and heard local authorities issue a recommendation like Katrina that the near-miss effect happens and

to evacuate. They were also asked whether or not merits further study. To understand the mechanics

they saw storm conditions such as high wind, rain, or of the near-miss phenomena in detail, we examine it

flooding, and whether they had personal experience using a series of laboratory studies.

with hurricane storm conditions.

Analysis and Results. Factor analysis revealed that Study 2

some control variables could be averaged into scales. We argue that near-miss information encourages

We created the “individual geographic proximity” riskier behavior (H1), but that this effect can be coun-

(alpha = 0074) scale by averaging the first two control teracted when the near miss includes information

variables and the “social cue” (alpha = 0081) scale by that highlights vulnerability (H2). We tested for the

averaging the next four control variables. difference between a resilient near miss and a vul-

Binary logistic regression was used to test H1, with nerable near miss by giving participants informa-

evacuation (yes/no) as the dependent variable. Four tion about an impending hurricane and asking them

control variables were entered in the first step (geo- whether or not they would evacuate. We have also

graphic proximity, social cues, see storm conditions, and said that this process operates automatically, and that

prior hurricane experience); our independent variable such automaticity makes the effect robust even in the

(prior unnecessary evacuation) was entered in the sec- face of experience. In this study, we verify our basic

ond step. Regression results, displayed in Table 1, hypotheses and test the robustness of the effect across

show that geographic proximity, social cues, and see- populations with varying levels of experience and

ing storm conditions all have a positive influence on expertise.

evacuation behavior, whereas prior unnecessary evac- Participants. For Study 2, we collected data from

uations has a negative influence. Thus, controlling for four different samples. Participants were (1) 352

geographic proximity, social cues, and seeing storm undergraduate and 47 graduate business students

conditions, prior near-miss experiences in the sense from a large, private university in the eastern United

of having evacuated when later deemed unnecessary States who completed a number of exercises, includ-

lead to less protective action in the form of evacuation ing ours, in return for class participation points;

in the face of an impending hurricane, supporting H1. (2) 82 upperclass undergraduate students at Tulane

Discussion. This study shows that prior near-miss University in New Orleans (two-thirds of whom evac-

experiences influence the behavior of people facing uated for Hurricane Katrina) who completed the short

similar subsequent threats, even amid all the con- exercise at the end of a regularly scheduled lec-

current forces that affect such behavior. Those with ture session; (3) 187 undergraduate business students

resilient near-miss experiences were significantly less from the same university as sample 1 who com-

likely to evacuate than those without this experi- pleted a number of exercises online, of which ours

ence, supporting H1. We recognize that an unneces- was one, in return for class participation points; and

sary evacuation is an imperfect proxy for a resilient (4) 102 emergency managers who averaged 13.6 years

near-miss experience, although we think there is cor- of experience with natural disasters, whose participa-

respondence because unnecessary evacuations imply tion was solicited though email lists and newsletters

that a disaster did not happen. However, the point of associated with the Natural Hazard Center in Col-

orado, and who participated in exchange for entrance

in a lottery to win sweatshirts.

Table 1 Study 1—Logistic Regression Results for Procedure. Participants read that they lived in

Evacuation from Hurricane Lili by Near Miss

an area subject to hurricanes and that the National

Model 1 Weather Service was tracking a hurricane that had a

Odds ratio 30% chance of hitting their community with moder-

Control variables

ate force within 36 hours. They were also told that

geographic proximity 1038∗∗ they lived alone, had no pets, and that evacuation

social cues 2022∗∗∗ would incur a sure loss of $2,000. However, if they

see storm conditions 0080∗ stayed and the hurricane hit, the collateral damage

prior hurricane experience 1000 (above and beyond damage to house, such as damage

Independent variable to one’s car, self, portable personal belongings, etc.)

prior unnecessary 0085∗

would add up to $10,000 (see Appendix A for the

evacuation (near miss)

full text). After reading the vignette, they answered

Nagelkerke R2 0023∗∗

whether or not they would evacuate. For the New

∗

p < 0005; ∗∗ p < 0001; ∗∗∗ p < 00001. Orleans sample, participants were also asked whetherTinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

6 Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS

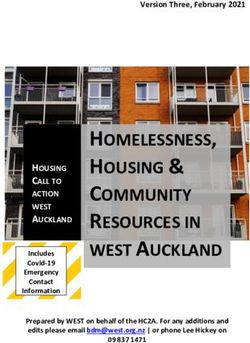

or not they had evacuated for Hurricane Katrina, and Figure 1 Study 2—Evacuation Rate by Condition for Different Sample

two-thirds reported that they had.5 Collections (See Table 2 for 2 Test Results)

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

Variables. We had three conditions: whether 100

90 Control

participants had resilient or vulnerable near-miss Resilient NM

80

information or no near-miss information (control).

% Evacuation

70 Vulnerable NM

Participants in the no near-miss information (control) 60

condition read, “You have no specific data regarding 50

40

past hurricane impacts to your property.” Participants 30

in the resilient near-miss condition read, “You have 20

lived in this house through three prior storms similar 10

0

to that forecasted, and you and your neighbors have General New Orleans General Expert

never had any property damage.” Participants in the students students students emergency

(Collection 1) (Collection 2) managers

vulnerable near-miss condition for Collections 1 and 2

Collection

read the resilient near-miss condition plus “In the last

storm, however, a tree fell on your neighbor’s house, Note. NM, near miss.

completely destroying the second story. If anyone had

been inside, they would have been seriously hurt.” study and the previous field study show the near-

Participants in the vulnerable near-miss condition miss effect, neither provides evidence of the mecha-

for Collections 3 and 4 read the resilient near-miss nism by which near-misses operate. The next study

condition plus “In the last storm, however, a tree fell examines whether people’s evaluations of the nature

on your neighbor’s car and completely destroyed it.” 6 of the hazard mediate their decision to evacuate.

The dependent variable was whether or not partic-

ipants would evacuate. Study 3

Analysis and Results. Figure 1 shows the per- This study looked into the hypothesized mechanisms

centage of participants in each condition for each through which near-miss information works. If differ-

collection who chose to evacuate. For all four sam- ent types of near misses cause changes to the hazard

ples, participants with resilient near-miss information category, then we would expect the different types

chose to evacuate significantly less than those with of near misses to change the assessments of risk (R)

but not the assessments of probability (P ). Moreover,

no near-miss information, supporting H1, and partic-

assessments of R should mediate observed mitigation

ipants with vulnerable near-miss information chose

choices (H3).

to evacuate more than those with resilient near-miss

Participants and Procedure. Participants in Study 3

information, supporting H2 (see Table 2 for 2 tests).

were 236 undergraduate and graduate business stu-

Discussion. Study 2 found that people with

dents who completed a number of exercises online, of

resilient near-miss information that highlights how a

which ours was one, in return for class participation

disaster did not happen were less likely to evacu-

points. Participants read the same story as in Study 2,

ate for an impending hurricane than people without

about living in a hurricane area, yet this time they

near-miss information (supporting H1). On the other answered questions about the thoughts and feelings

hand, people with vulnerable near-miss information associated with the impending hazard.

that highlights how a disaster almost happened were

more likely to evacuate than people with resilient

near-miss information (supporting H2). And these Table 2 2 Results for Study 2

results were robust across participants representative 2 (1): Control vs. 2 (1): Resilient vs.

of the general population (Collections 1 and 3), those resilient near miss vulnerable near miss

who live in a culture highly sensitive to hurricanes Data collection (Hypothesis 1) (Hypothesis 2)

(i.e., New Orleans), many of whom had prior evacu- 1 = General 2 415 = 20063, p < 00001 2 415 = 11098, p < 00001

ation experience (Collection 2), and emergency man- population

agement practitioners (Collection 4). Although this students

2 = Tulane 2 415 = 8002, p < 0001 2 415 = 6096, p < 0001

students

5

Note that given the timing of the data collection, these students (experienced)

would still have been in high school during Hurricane Katrina and 3 = General 2 415 = 3031, p < 0005 2 415 = 10086, p < 0001

not matriculated students at Tulane. population

6 students

We altered the wording for Studies 3 and 4 to test whether the

4 = Emergency ( 2 415 = 2085, p < 0005 2 415 = 6068, p < 0001

effect was robust to different types of harm information—bodily

managers

injury versus harm to property—which it was. We thank Howard

(experts)

Kunreuther for this suggestion.Tinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS 7

Variables. We used the same three conditions Figure 2 Study 3—Risk Judgments by Condition

from Study 2 for the independent variables: control,

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

8

resilient near miss, and vulnerable near miss (with Perceived risk Likelihood hit Outcome unattractiveness

Scale from factor analysis

the wording from Collections 3 and 4). For dependent 7

variables, participants answered on a 10 point scale

6

(1 equaled “not at all” and 10 equaled “extremely”),

about the extent to which they felt worried, anxious, 5

vulnerable, distressed, dread, safe, and protected, and

whether the situation before evacuating was risky. 4

They also answered on a 10 point scale (1 equaled

3

“not at all” and 10 equaled “very much”) how much

they agreed with the following statements: the dam- 2

age will be bad, I could experience much harm, the Control Resilient NM Vulnerable NM

condition

damage will not be a big deal, my chances of being

hit are good, and I will likely suffer damage. Finally,

they were asked whether or not they would evacuate. Following James and Brett (1984), we assessed

Analysis and Results. We used a factor analysis (1) whether the mediators are a probabilistic func-

with varimax rotation to examine the associations tion of the independent variables, (2) whether the

people had with the hurricane warning and found dependent variable is a probabilistic function of the

three factors: (1) estimations of probability (of being independent variable, (3) whether the dependent vari-

hit, chances of being hit are good and I will likely able is a probabilistic function of the mediators, and

suffer damage; alpha = 0081); (2) estimations of out- (4) how the addition of the independent variable to

come (un)attractiveness (damage will be bad, harm step 3 changes the variance explained in the depen-

will be incurred, and damage will be no big deal dent variables. Full mediation occurs when the addi-

(reverse coded); alpha = 0086); and (3) perceptions of tion of the independent variables does not explain

any additional variance in the dependent variables

risk versus safety (worried, anxious, vulnerable, dis-

beyond what the mediators explained (i.e., the change

tressed, dread, risky, safe (reverse coded), and pro-

in R2 from step 3 to step 4 is not significant). If the

tected (reverse coded); alpha = 0093). Three scales

change in R2 from step 3 to 4 is significant, then par-

(probability of hit, outcome unattractiveness, and per-

tial mediation is a possibility.

ceived risk) were created for each factor averaging the

Step 1 was accomplished with the MANOVA

above described items, and were subject to a multi-

detailed above (again see Figure 2). For step 2, binary

variate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with condi-

logistic regression showed that evacuation decisions

tion (control, resilient near miss, and vulnerable near were significantly influenced by resilient near-miss

miss) as the independent variable. experiences (Table 3, model 1). For step 3, binary

The multivariate F was significant (Wilks Lambda logistic regression showed that evacuation decisions

F461 4625 = 2023, p < 0005), as were the univariate F val- were significantly influenced by perceived risk and

ues for perceived risk (F411 2335 = 3056, p = 0003) and outcome unattractiveness (Table 3, model 2). For

outcome unattractiveness (F411 2335 = 3004, p = 0005). The

means for the three scales by condition are plotted

Table 3 Study 3—Binary Logistic Regressions on Evacuation Behavior

in Figure 2. Planned contrasts (using Tukey’s hon-

est significant difference) showed that for perceived Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

risk, the significant difference across conditions was Odds ratio Odds ratio Odds ratio

driven by the resilient near-miss condition being sig- Independent variablea

nificantly lower than the vulnerable near-miss condi- Dummy resilient near miss 0056∗ 0065

tion (p < 0005), and marginally lower than the control Dummy vulnerable near miss 0067 0055

(p = 001). For outcome unattractiveness, the signifi- Mediators

cant difference across conditions was again driven by perceived risk (R) 1028∗∗ 1027∗∗

outcome unattractiveness (O) 1013+ 1014+

the resilient near-miss condition being significantly probability of hit (P ) 1001 1003

lower than the vulnerable near-miss condition (p <

Nagelkerke R2 0002∗ 0012∗∗ 0013∗∗

0005). Probability of hit was not significantly differ- Change in R2 0001

ent across conditions. To test for mediation we used (from models 2 to 3)

binary logistic regression on whether or not people a

For the condition variable, the control was chosen as the reference cat-

chose to evacuate. Dummy variables were created for egory; thus the regression weights for the first row, for example, show the

the resilient near-miss and vulnerable near-miss con- effect for having resilient near-miss information.

+

ditions, using control as the referent category. p < 0007; ∗ p < 0005; ∗∗ p < 0001.Tinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

8 Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS

step 4, when the condition variables were added to might produce more downward counterfactuals than

model 2 as additional explanatory variables, these resilient near misses, which might impel the protec-

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

condition variables did not contribute any unique tive action we see participants take in this condition.

additional explanatory power (Table 3, model 3). The This might be particularly true if the severity of the

nonsignificant betas in model 3 for the condition vari- negative consequences in the near-miss information is

ables and lack of any measurable change in R2 sug- high (that someone could have been severely injured

gest full mediation. Near-miss information influences or even killed) rather than low (that someone could

perceptions about risk and consequences, which influ- have been inconvenienced). Thus, we test for counter-

ence whether or not participants evacuated in the face factual thinking in this study, and we vary the sever-

of a hurricane warning. ity of the negative consequences (high versus low).

Discussion. Study 3 found that near-miss informa- Another limitation of Studies 2 and 3 is that people

tion influenced the associations people had with the may be legitimately updating their beliefs about the

hazard, which mediated people’s subsequent mitiga- resilience of their house using Bayesian logic; that is,

tion behavior. The resilient near miss tends to be asso- perhaps people are processing the near-miss experi-

ciated with lower risk, which explains the consistent ence as data to recalculate the likelihood of hurricane

lack of protective action by these participants com- damage to their particular house, thereby reducing

pared to those in the other conditions. The vulnerable it from the stated 30%. Moreover, given that their

near misses (highlighting danger albeit to someone house is stationary, each hurricane threat is not truly

else) tend to counteract these reassurances. Study 3 an independent event, and participants could reason-

supports our theoretical model, that near misses are ably infer that their particular house is at less risk

stimuli that influence the general hazard category than what was previously calculated.

(Kahneman and Miller 1986) so that assessments of In Study 4, we asked the person to decide whether

risk are either raised or lowered (depending on type or not to go on a Caribbean cruise that is threat-

of near miss) to influence behavior. However, there ened to be interrupted by a hurricane. The survival

are still several alternative explanations for our find- of a prior cruise ship during a Caribbean hurricane is

ings that need to be examined, such as near misses completely independent from the chances of survival

encouraging counterfactual thought or prompting of their current Caribbean cruise ship given the con-

legitimate Bayesian updating. Our next studies test stantly changing ship location. We nonetheless tested

these alternatives, and in doing so demonstrate that for likelihood updating by asking participants what

our behavioral results generalize more broadly. they believe to be the percentage chance of being hit

by a storm. We also vary the severity descriptions

Study 4 of the possible consequences from high (warning of

An alternative to our proposed mechanism (that near severe injury or even death) to low (inconvenience)

misses implicitly influences the knowledge associated and explore the role of counterfactuals in their deci-

with the hazard category) is that near misses prompt sion process.

counterfactual thoughts. A counterfactual is an alter- Participants and Procedure. For Study 4, we col-

native to reality. Thus a counterfactual thought is lected data from 299 undergraduate business students

thinking explicitly about what could, should, or might who completed a number of exercises online, of which

have been (Kahneman and Tversky 1982). Upward ours was one, in return for class participation points.

counterfactuals are thoughts about how an alternative Participants read that they had nonrefundable tickets

could be better than the realized outcome; downward for a Caribbean cruise that is leaving the next day, but

counterfactuals are thoughts about how an alternative the National Weather Service is currently tracking a

could be worse than the realized outcome (Roese and hurricane in the Caribbean that they estimate has a

Olson 1995). Counterfactual thought is more likely to 30% chance of impacting the cruise. They were also

occur when people encounter a surprise outcome than provided costs associated with not going on the trip

when they encounter a routine outcome (Kahneman and with going on the trip if a hurricane diverts the

and Miller 1986, Miller et al. 1989), or when activated ship. The participant then decided whether or not to

by a problem that needs to be addressed (such as a go on the trip. For the full text of the exercise, see

bad outcome that someone wishes to avoid) (Epstude Appendix B.

and Roese 2008). Thus, if near misses either surprise Variables. Five conditions made up the indepen-

participants (as in the resilient near miss, that dan- dent variables: control and resilient near miss ver-

ger was avoided) or are represented as a problem sus vulnerable near miss crossed by strong versus

(as in the vulnerable near miss, that danger almost weak prime (see Appendix B for specific wording).

happened), one could argue that they evoke coun- To briefly summarize, in the control condition, partic-

terfactual thinking, and that this guides the mitiga- ipants were told that cruises can be diverted because

tion behavior. For example, vulnerable near misses of hurricanes but receive no information about priorTinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS 9

cruises being impacted by hurricanes. In the resilient conditions and compared these to the resilient near-

conditions, participants read that cruises can be miss conditions. Significantly more people with vul-

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

diverted by hurricanes but that they have been on nerable near-miss information were willing to forgo

three prior cruises and never experienced any prob- the cruise than people with resilient near-miss infor-

lems. In the vulnerable conditions, participants read mation ( 2 415 = 8014, p < 0001), supporting H2.

that cruises can be diverted by hurricanes but that To test whether severity of consequences had any

they have been on three prior cruises and never expe- influence on people’s travel decisions, we compared

rienced any problems; however, they know someone the weak versus strong severity within each type

else who has. In the weak conditions, participants of near miss. Although participants whose near-miss

were reminded that hurricane diversions can cause experiences included severe (strong) consequences

delay and cost money, and in the strong conditions were slightly less likely to go on the cruise than par-

participants were reminded that in addition to delays ticipants whose near-miss experiences included weak

and costs, people can be injured or even killed. consequences (50.8% versus 58.5% in the resilient

For the dependent variables, participants answered near-miss condition; 32.8% versus 39.0% in the vul-

whether or not they would go on the trip. Then, par- nerable near-miss condition), neither of these differ-

ticipants were asked: “Please answer the following ences were statistically significant (resilient, 2 415 =

statements as thoroughly as possible. ‘In making this 0067, p > 001; vulnerable, 2 415 = 00501 p > 001). Thus,

decision, I thought about if 0 0 0 1’ ‘I also thought about for the following analyses, we collapse data across the

if 0 0 0 1’ and ‘I also thought about if. 0 0 0’ ” Participants severity conditions.

then rated their belief that a hurricane would impact To test whether people with near misses are updat-

their ship (from 0%–100%). ing their calculation of the likelihood of harm, we

ran an ANOVA on participants’ belief that a hurri-

The open-ended responses were coded by two

cane would impact their ship (from 0%–100%). Across

research assistants blind to conditions and hypothe-

all conditions, participants slightly inflated their belief

ses. They coded whether the statement contained an

that a hurricane would impact their ship from the

upward counterfactual (e.g., “If I go, I will have the

given 30% (control mean, 35%; s.d., 18; resilient mean,

time of my life”), a downward counterfactual (e.g.,

33%; s.d., 17; vulnerable mean, 35%; s.d., 17), but there

“If I were to get diverted on the cruise, I would miss

were no significant differences across the conditions

work”), a neutral counterfactual (e.g., “If I could sell

(F421 2895 = 0032, p > 001).

the cruise tickets to another party”), or no counterfac-

To test whether near misses prompt counterfactual

tual (e.g., “$2,000 is a sunk cost and I should not make

thoughts, we looked at whether different near-miss

my decision based on it”) (Nasco and Marsh 1999). experiences produce different types of counterfactual

Analysis and Results. Results for participants’ thoughts. Figure 4 shows the percentage of partic-

decisions (to forgo the trip or not) are shown in ipants’ counterfactual thoughts by condition. Most

Figure 3. To test H1, we collapsed the two resilient of participants’ responses contained a downward

near-miss conditions and compared them to the no counterfactual thought, followed by no counterfac-

near-miss experience (control). Significantly fewer tual thought. Importantly, however, there were no

people with resilient near-miss information were will- systematic differences in types of thought across con-

ing to forgo the cruise than people without near-miss ditions ( 2 465 = 60451 p > 001). Thus, the explana-

information ( 2 415 = 5099, p < 0005) supporting H1. tion that near misses evoke a particular counterfactual

To test H2, we collapsed the two vulnerable near-miss thought to explain the observed differences in mitiga-

tion behavior fails the first test requirement to demon-

strate mediation (James and Brett 1984).

Figure 3 Study 4—Percentage of Participants Forgoing the Cruise,

by Condition

Figure 4 Study 4—Percentage of Participants’ Counterfactual (CF)

Percentage forgoing cruise

0.8

Thoughts, by Condition

0.7

Percentage of responses

0.6 0.6

0.5 Control

0.5

0.4 Resilient near miss

0.4

0.3 Vulnerable near miss

0.3

0.2

0.1 0.2

0 0.1

Resilient Resilient Vulnerable Vulnerable Control

0

NM weak NM strong NM weak NM strong

No Downward CF Neutral CF Upward CF

Note. NM, near miss. counterfactualTinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

10 Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS

Figure 5 Study 4—Percentage of Counterfactual (CF) Thoughts, responses (the mediators) occurred in the same exper-

by Cruise Decision imental period. Thus, there is the possibility that there

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

0.6 is some reverse causality operating between how the

Percentage of responses

Forgo cruise hazard is described and the person’s decision; that is,

0.5 Go on cruise

one could decide to engage in a behavior and then use

0.4

that decision to shape how they characterize the situ-

0.3 ation, or these could coevolve. To discount this alter-

0.2 native, we examined the thoughts people had about a

0.1 hazardous situation (encoded under our different con-

ditions of near-miss information) absent any decision

0

No Downward CF Neutral CF Upward CF about what to do. By removing the need to make a

counterfactual choice, we removed any potential that the assessment

of the situation was based on the desire to justify a

particular decision. This task has the additional bene-

To discount the possibility that we miscoded

fit of providing evidence that the biasing effect of near

the various types of counterfactual thoughts, we

misses precedes the construction of an SEU evaluation

tested whether the different counterfactual thoughts

(something assumed via our theory but not tested in

as coded were associated with different mitigation

our context). We have argued that near-miss informa-

behaviors in reasonable ways and found that they

tion changes the valence of the knowledge associated

were. Figure 5 graphs the percentages of partici-

with a type of hazard; if that is so, then we should

pants’ counterfactual thoughts by cruise decision and

expect to see different kinds of thoughts retrieved

shows that counterfactual thoughts do influence the

depending on type of near miss presented.

decision. As would be expected, decisions to go

In Study 5, we gave participants a fictitious news-

on the cruise were associated with more upward

paper article to read about cruises during hurricane

counterfactual thoughts (upward counterfactuals ver- season and then asked them to describe thoughts and

sus other counterfactuals, 2 415 = 2700, p < 00001), feelings associated with the general category “cruises

whereas decisions to forgo the cruise were associated during hurricane season.” The task resembles Study 4,

with downward counterfactual thoughts (downward except that we removed the decision. We expected

counterfactuals versus other counterfactuals, 2 415 = resilient near misses to be associated with more

809, p < 0001). In sum, counterfactual thoughts, once positively valenced thoughts, and vulnerable near

evoked, can produce systematic differences in mitiga- misses to be associated with more negatively valenced

tion behavior, yet near misses do not systematically thoughts. We did not make predictions about spe-

activate any particular type of counterfactual thought. cific feelings (like harm, because the person reading a

Therefore, counterfactual thoughts do not provide a newspaper article has no reason to feel any danger) or

compelling explanation for why near misses influence beliefs (e.g., hurricanes will cause damage), but rather

mitigation decisions. tested changes in the overall evaluations of the sit-

Discussion. We showed that even when the situa- uation (which should be guided by the information

tion does not support updating one’s beliefs (because associated with the hurricane category).

the interaction of hurricanes and Caribbean cruises Participants and Procedure. For Study 5, we col-

are independent events), the near-miss effect still lected data from 229 undergraduate business students

operates. People who experience resilient near misses who completed a number of exercises online, of which

are more likely to ignore a hurricane warning and go ours was one, in return for class participation points.

on the cruise, whereas people who experience vulner- Participants read a news story about how Caribbean

able near misses are more likely to choose the miti- cruises are deeply discounted in October and Novem-

gation behavior, forgoing the cruise. We also showed ber because of hurricane season. The story closes by

that people with near-miss information are not revis- stating that the national weather service is tracking a

ing their calculations of the likelihood of the hazard in hurricane that could impact the ship that a fictitious

ways that might explain either their decision to go on Bill Thompson is currently boarding. For the full text

or to forgo the cruise. Finally, we showed that while of the exercise, see Appendix C.

counterfactuals are related to the ultimate choice peo- Variables. For the independent variable, we used

ple make, counterfactual thinking is not predicted by same five conditions for this study as for Study 4:

a near-miss experience. control, resilient near miss (strong), resilient near miss

(weak), vulnerable near miss (strong), and vulnera-

Study 5 ble near miss (weak). See Appendix C for the specific

A potential concern with the meditational analysis of wording. After reading the news article, participants

Study 3 is that peoples’ decisions and their survey wrote their general thoughts about whether or notTinsley, Dillon, and Cronin: How Near-Miss Events Amplify or Attenuate Risky Decision Making

Management Science, Articles in Advance, pp. 1–18, © 2012 INFORMS 11

they thought fall cruises were a good idea. Partici- Table 4 Counts of Each Thought Type Based on Topic, Valence, and

pants also gave two ratings on a 1–5 scale: (1) their Near-Miss Condition

posted on any other website, including the author’s site. Please send any questions regarding this policy to permissions@informs.org.

Copyright: INFORMS holds copyright to this Articles in Advance version, which is made available to subscribers. The file may not be

general impression of cruises and (2) whether or not Near-miss type

they thought that Bill Thompson (who loves cruising

during hurricane season) has the correct attitude. Thought No

type near miss Resilient Vulnerable

Written responses were unitized into thoughts

(subject–verb–object). Thus, a thought could be a sen- Fun Valence

tence (e.g., “Hurricanes are a big scare” has one unit). Negative

Count 11 17 30

There could also be multiple units in a sentence (e.g.,

% within near miss 4400 3708 6308

“You save money and have fun” has the two objects

Positive

and verbs with the same subject). These thoughts Count 14 28 17

were content coded by a research assistant blind to the % within near miss 5600 6202 3602

hypotheses based on issues people seemed to think Safety Valence

about when deciding about the cruise in the prior Negative

counterfactual study. The five basic issues are fun Count 7 13 23

(thoughts about how enjoyable or not the experience % within near miss 7708 7605 7607

Positive

would be; e.g., “it is not as crowded”), harm (thoughts

Count 2 4 7

about safety and getting hurt personally; e.g., “there % within near miss 2202 2305 2303

is little risk of injury”), monetary value (thoughts about Value Valence

the cost/benefit ratio of the cruise; e.g., “it’s a good Negative

value”), the likelihood of problems (thoughts about prob- Count 6 10 15

ability with respect to adverse events; e.g., “some- % within near miss 3000 2202 3805

thing could always go wrong”), and risk acceptance Positive

Count 14 35 24

(thoughts about whether, in general, the risk/reward % within near miss 7000 7708 6105

trade-off makes sense; e.g., “why put yourself at

Probability Valence

risk?”). Thoughts were also coded for whether it was Negative

attitudinally positive or negative; thus, in the same Count 4 3 2

category of thought about the likelihood of problems, % within near miss 10000 2000 1403

a statement could be for (e.g., “I don’t mind the risk”) Positive

Count 0 12 12

or against (e.g., “I would not want to take the risk”)

% within near miss 000 8000 8507

a cruise in hurricane season.

Risk Valence

Analysis and Results. We first looked to see how Negative

our 10 codes (five topics by two valences) differed Count 15 24 20

across conditions. As in Study 4, severity of conse- % within near miss 6802 7006 8303

quences had little effect. Only one of the 10 codes Positive

(specifically, monetary value negatively valenced) Count 7 10 4

% within near miss 3108 2904 1607

reached significance, in that participants who read

Total

about a strong consequence (people could have died)

Count 80 156 154

were more likely to generate negative monetary value % within near miss 10000 10000 10000

thoughts (e.g., this cruise would not be a good value)

than participants who read about a weak consequence

(people could be inconvenienced or injured; p < 0001). marginally significantly more negative-value-related

Given the general similarities in people’s thought pat- thoughts in the vulnerable near-miss condition than

terns across strong versus weak consequences, we in the resilient near-miss condition ( 2 415 = 2065,

collapsed across these conditions and looked at the p < 001, one tailed). Finally, they generated more

influence of near-miss type (resilient versus vulnera- negative- risk-related thoughts in the vulnerable near-

ble versus control). miss condition than in the resilient near-miss condi-

Table 4 shows the raw counts of each thought tion, although these differences were not significant.

type based on topic, valence, and near-miss condition. We further tested whether near-miss information

The overall 2 (2) for the table was significant at 7.69 and severity affected the thoughts people had by run-

(p = 0002), and this significance was primarily driven ning a logistic regression using contrast coding for

by different valence of thought across the near-miss conditions (Judd and McClelland 1989). As Table 5

conditions. Participants generated significantly more shows, the type of near miss affects the valence of the

negative-fun-related thoughts in the vulnerable near- thoughts associated with cruises; resilient near misses

miss condition than in the resilient near-miss con- decrease the number of negative thoughts about

dition ( 2 415 = 6024, p < 0005). They also generated cruises, as well as increasing the ratio of positiveYou can also read