Growth with Depth 2014 African Transformation Report - OVERVIEW - Ferdi

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

The African Center for Economic Transformation is an economic policy institute supporting Africa’s long-term growth through transformation. Our vision is that by 2025 all African countries will drive their own growth and trans- formation agendas, led by the private sector and supported by capable states with good policies and strong insti- tutions. We work toward that vision through our analysis, advice, and advocacy. Please visit www.acetforafrica.org. African Center for Economic Transformation Ghana United States Office Location Mailing Address 1776 K Street, NW 50 Liberation Road Cantonments Suite 200 Ridge Residential Area PMB CT 4 Washington, DC Accra, Ghana Accra, Ghana 20006 Phone: +233 (0)302 210 240 Phone: +1 202 833 1919 For general inquiries, including press, contact info@acetforafrica.org Copyright © 2014 The African Center for Economic Transformation ISBN: 978-0-9833517-4-0 Photo credits: cover, Eric Nathan/Getty Images; pages vi–1, Gallo Images - Flamingo Photography.

iii

Foreword

African Transformation Report 2014 | Foreword

Last year the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level growth and development and identifies best practic-

Panel on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, which I es from Africa and beyond. It will be of great value to

co-chair, released its report setting a clear roadmap for African policymakers as they draw up action plans to

eradicating extreme poverty. We recommended that transform their economies and ensure that growth is

the post-2015 goals be driven by five big transforma- sustained to improve the lives of an increasing number

tive shifts. One of these shifts is a profound economic of Africans, consistent with the AU’s transformation

transformation to improve livelihoods by harnessing vision. And by setting a transformation agenda, it will

innovation, technology, and the potential of business- contribute to international discussions on the strategies

es. We concluded that more diversified economies, with and priorities for achieving many of Africa’s post-2015

equal opportunities for all, would drive social inclusion, development goals.

especially for young people, and foster sustainable con-

sumption and production. Five years ago, I welcomed ACET’s establishment in the

expectation that it would give new meaning to African

Nowhere is the need for such a transformative shift ownership of Africa’s destiny. With this report, ACET has

greater than in Africa. Recognizing this imperative, earned that recognition.

the African heads of state and government recently

endorsed the African Union’s transformation vision

for 2063. The key dimensions of that vision are to

address the structural transformation of Africa’s output

and trade, strengthen Africa’s infrastructure and

human resources, and modernize Africa’s science and

technology. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

President

I commend the African Center for Economic Trans- Republic of Liberia

formation (ACET) for preparing this welcome report. Co-chair

It looks at transformation as a broad framework for UN High Level Panel on the Post-2015 Development Agendaiv

Preface

African Transformation Report 2014 | Preface

By 2050 Sub-Saharan Africa will have a larger and part greatly enriched the discourse and resoundingly

younger workforce than China or India. With the con- endorsed our work, including our plans to produce this

tinent’s abundant land and natural resources, that report.

workforce can be a global competitive advantage and a

great asset in driving economic transformation. Economic transformation is now the consensus par-

adigm for Africa’s development. The UN’s High Level

Such a transformation will come through diversifying Panel on the global development agenda after 2015

African economies, boosting their competitiveness in sets out the priorities for transforming African’s econo-

world markets, increasing their shares of manufactur- mies for jobs and inclusive growth. The African Union’s

ing in GDP, and using more sophisticated technology Vision 2063 calls for integrating the continent’s econo-

in production. Economies will then become much more mies so that they partake more in the global economy

prosperous, less dependent on foreign assistance, and and in regional opportunities. The African Develop-

much more resilient to shocks—mirroring the success- ment Bank’s long-term strategy, At the Center of Africa’s

es of Asian and Latin American countries over the past Transformation, has the goal of establishing Africa as the

several decades. next global emerging market. And the Economic Com-

mission for Africa’s 2013 economic report, Making the

The impressive economic growth of many African coun- most of Africa’s commodities: Industrializing for growth,

tries since the mid-1990s—as well as the progress in gov- jobs, and economic transformation, details what’s

ernance and the turnaround in investor c onfidence— needed to promote competitiveness, reduce depen-

provides a solid foundation for transforming African dence on primary commodity exports, and emerge as

economies for better jobs and shared prosperity. a new global growth pole.

This first African Transformation Report draws on our Our report’s main premise is that African economies

three-year research program of country, sector, and need more than growth—if they are to transform,

thematic studies to offer analyses and lessons that can they need growth with DEPTH. That is, they need to

be tailored to each country’s endowments, constraints, Diversify their production, make their Exports com-

and opportunities. In 2010, working with local think petitive, increase the Productivity of farms, firms, and

tanks, we began to assess the transformation records, government offices, and upgrade the Technology they

platforms, and prospects of 15 Sub-Saharan countries. use throughout the economy—all to improve Human

Brief summaries of those studies appear in the country well-being.

transformation profiles in an annex to the report.

Working with African and international economists, A key feature of the report is ACET’s new African Trans-

our staff also produced cross-cutting studies of themes formation Index, which assesses the performance

important to Africa’s transformation. And working with of countries on the five depth attributes of transfor-

African consultants, we produced studies of sectors mation and aggregates them in an overall index. It

holding promise for adding value to Africa’s agricultural shows policymakers, business people, the media, and

and manufactured products. the public how their economies are transforming and

where they stand in relation to their peers. It can thus

In 2011 we invited 30 leading thinkers on African devel- be a starting point for national dialogues on key areas

opment to come to Rockefeller’s conference center in for launching transformation drives. We plan to refine

Bellagio and to provide their perspectives on the chal- the index in coming years and to expand its coverage

lenges of economic transformation. Attending were beyond the 21 countries assessed here.

African ministers and business leaders, academics from

prominent think tanks, senior officials from multilateral The report recognizes that transformation doesn’t

development banks, and development specialists from happen overnight but is a long-term process. It requires

Asia and Latin America. The workshop drew lessons constructive relationships between the state and the

from outside Africa to help us make our approach more private sector. True, private firms will lead in producing

responsive to the needs of African policymakers. It also and distributing goods and services, in upgrading tech-

explored possible networks for collaboration in pur- nologies and production processes, and in expanding

suing Africa’s transformation agenda. All those taking employment. But firms need a state that has strongv

capabilities in setting an overall economic vision and Economist Yaw Ansu, as well as the substantive contri-

African Transformation Report 2014 | Preface

strategy, efficiently providing supportive infrastructure butions by think tanks and experts in Africa and across

and services, maintaining a regulatory environment the globe, the constructive reviews of transformation

conducive to entrepreneurial activity, and making it studies and draft chapters by specialists well versed

easier to acquire new technology and enter new eco- in the field, and the generous support of internation-

nomic activities and markets. al foundations and development organizations that

believed in our resolve to help drive the discourse on

That will require committed leadership to reach a con- Africa’s economic transformation through growth with

sensus on each country’s long-term vision and strategy depth.

and to coordinate the activities of all actors in pursuing

economic transformation. Our hope is that the analysis

and recommendations in this report will support them

in moving forward with their transformation plans, pol-

icies, and programs.

K.Y. Amoako

Producing this report was possible only through President

the dedicated efforts of ACET staff, led by our Chief African Center for Economic TransformationOVERVIEW 1

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

Transforming African

economies through

growth with depth

Since the mid-1990s many Sub-Saharan countries have

seen solid economic growth buoyed by reforms in

macroeconomic management, improvements in the

business environment, and high commodity prices.

Rising incomes are supporting the emergence of an

African middle class, and young Africans are now much

more likely to return home to pursue a career after an

education abroad.

The premise of this first African Transformation Report is that the recent

economic growth, while welcome, will not by itself sustain development

on the continent. To ensure that growth is sustainable and continues to

improve the lives of the many, countries now need to vigorously promote

economic transformation. Growth so far has come from macroeconomic

reforms, better business environments, and higher commodity prices. But

economic transformation requires much more. Countries have to diversify

their production and exports. They have to become more competitive on

international markets. They have to increase the productivity of all resource

inputs, especially labor. And they have to upgrade technologies they use in

production. Only by doing so can they ensure that growth improves human

well-being by providing more productive jobs and higher incomes and

thus has everyone share in the new prosperity. So, what African countries

need is more Diversification, more Export competitiveness, more Produc-

tivity increases, more Technological upgrading, and more improvements in

Human well-being. In short, they need growth with depth.

The state, private firms, workers, the media, and civil society all have

mutually reinforcing roles in promoting economic transformation. Private

firms—foreign and local, formal and informal—lead in producing and dis-

tributing goods and services, in upgrading technologies and production

processes, and in expanding the opportunities for productive employment.

But they can be helped by a state that has strong capabilities in setting an

overall economic vision and strategy, efficiently providing supportive infra-

structure and services, maintaining a regulatory environment conducive to

entrepreneurial activity, and facilitating the acquisition of new technologies

and the capabilities to produce new goods and services and to access new

foreign markets.

Similarly, the state can gain much from having firms and entrepreneurs

weigh in on setting a national economic vision and strategy—and on

designing policies, investments, and incentives to support that strategy.2

And strong third-party mechanisms industrializing for jobs, growth, and generally find it a challenge to

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

of accountability can draw in par- economic transformation. 3 It notes compete, except in primary agricul-

liaments, independent media, aca- that major firms are outsourcing tural commodities and extractives.

demics, think tanks, and other parts tasks beyond their core competen- And the levels of vulnerable and

of civil society to ensure that close cies and thus shifting the structure informal employment are high—

collaboration between officials and of global value chains. That could around 80% in many countries—

An essential firms does indeed support econom- change the relationships between which translate to high poverty

part of economic ic transformation. the exploitation of oil, gas, and min- levels—with around 50% of the

erals and the location of industries population living on less than $1.25

transformation

that process them. a day. Pursuing economic transfor-

is acquiring the Economic transformation is mation, or the growth with DEPTH

capability to now the agenda Those are just a few of the organiza- agenda, is therefore imperative for

tions propounding structural shifts African countries.

produce a widening

The UN High Level Panel on the from agriculture and mining to

array of goods development agenda after 2015 manufacturing and to services that To make the case for transforma-

and services and identifies four priorities to trans- are at the heart of economic trans- tion as growth with depth, we

form economies for jobs and formation. But as this first African compare Africa’s performance with

then choosing

inclusive growth.1 First is creat- Transformation Report argues, there that of eight earlier transformers:

which ones to ing opportunities for productive is more to transforming economies Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, Malaysia,

specialize in based jobs and secure livelihoods that than shifting their structures. Singapore, South Korea, Thailand,

on international make growth inclusive and reduce and Vietnam. Forty years ago

poverty and inequality. Second is their economies had features that

relative prices raising productivity to accelerate Growth with depth to today characterize many African

and sustain growth everywhere transform African economies c ountries—widespread poverty,

by intensifying agriculture, devel- low productivity, low technolo-

oping industry, and expanding Many African economies are gy, and limited exports. But they

services—in whatever mix matches growing faster than they have in 40 ignited and sustained long periods

a country’s endowment. Third is years. Six of the world’s 10 fastest of high GDP and export growth,

setting an environment for business growing countries in the 2000s economic diversification, technol-

to flourish and connect through were in Sub-Saharan Africa: Angola ogy upgrading, and productivity

value chains to major markets at at 11.1% a year, Nigeria 8.9%, Ethio- increases and greatly improved the

home and abroad. And fourth is pia 8.4%, Chad 7.9%, Mozambique lives of their people. Today several

supporting new ways of producing 7.9%, and Rwanda 7.6%. 4 And of them are upper middle- or even

and consuming that sustain the several others were above or near high-income countries (figure 1).

environment. the 7% growth needed to double

their economies in 10 years. Diversified production

The African Union’s 2063 Agenda

calls for the region’s economies Behind the growth are the imple- An essential part of economic trans-

to integrate and to join the global mentation of better economic formation is acquiring the capa-

economy. 2 This will require devel- policies, the end of the decades- bility to produce a widening array

oping human capital through edu- long debt crisis, high commodity of goods and services and then

cation and training, especially in prices and rising discovery and choosing which ones to specialize

science, technology, and innova- exports of oil, gas, and minerals, in based on international relative

tion. It will also require accelerating and the beneficial impacts of new prices. This has been the experience

infrastructure development to link information and communication of today’s developed countries:

African economies and people by technologies. But the structure of increasing the diversity of produc-

meeting the targets set for energy, most Sub-Saharan economies has tion before specializing to better

transport, and information and not changed much over the past take advantage of market opportu-

communication technologies. And 40 years. Production and exports nities. Today, Sub-Saharan countries

it will require fostering meaningful are still based on a narrow range are confined to a narrow range of

partnerships with the private sector. of commodities; the share of man- commodity production and exports

ufacturing in production and not because they choose to spe-

The UN Economic Commission for exports remains relatively low, as cialize, but because they lack the

Africa’s 2013 Economic Report on do the levels of technology and technical and other capabilities

Africa calls for making the most of productivity across economies. On to expand into other higher tech-

the continent’s commodities by global markets African countries nology products and services. The3

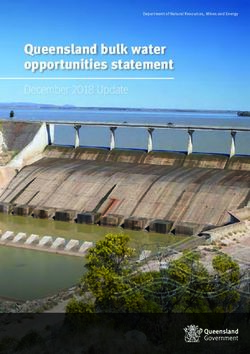

region’s average share of manu- Figure 1 Growth with DEPTH for transformation

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

facturing value added in GDP, an

Sub-Saharan Africa Earlier transformers

indicator of diversity in production,

was less than 10% in 2010, much the GDP per capita growth Diversity in production

same as in the 1970s. In contrast, 10 30

% of manufacturing value added in GDP

the share is nearly 25% in the earlier 24.2

% (three-year moving average)

transformers.

5 4.29 20

Export competitiveness

2.09

0 10

Exporting provides the opportu- 8.7

nity to expand production, boost

employment, reduce unit costs, –5

1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

0

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2011

and increase incomes. It also

enables a country to better exploit Diversity in exports Export competitiveness

its comparative advantage to gen- 100 20

% of top five exports in total exports

world average (without extractives)

erate higher incomes, which help

% of exports in GDP relative to

pay for the investments in skills, 75 15

capital, and technology needed to

64.3

upgrade a country’s comparative 50 10

advantage over time. And knowl- 44.2

edge and exposure to competi- 25 5 3.62

tion gained from exporting help 0.83

in diversifying to new economic 0 0

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2011

activities and raising productivi-

ty. Export competitiveness can be

Productivity in manufacturing Productivity in agriculture

measured by a country’s global

60 5,000

export share divided by its global 4,568

Cereal yields (kilograms per hectare)

Manufacturing value added

GDP share. If this share is high, the 50

per worker ($ thousands)

4,000

country exports a higher share of 40 36,083

its GDP than the world average. For 3,000

30

both exports and GDP we exclude 2,000

20 1,509

extractives, since rising extractive

11,708

production and exports in Africa 10 1,000

normally does not indicate progress 0

1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 0

on economic transformation. Trends 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2011

in this measure of export competi-

tiveness show a large gap between Technological upgrading Human well-being

50 6

the African countries and the earlier 5.3

GDP per capita (index, 1970 = 1)

transformers. The share of non- 39 5

high-technology exports

40

extractive exports in nonextractive

% of medium- and

4

GDP rose between 1980 and 1985. 30

3

It has since been on a downward 20

trend, revealing that the region’s 12 2

1.7

recent GDP growth has not been 10

1

matched by corresponding growth

0 0

in exports outside extractives. 1976 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2012 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2012

Productivity gains on farms and Note: The eight earlier transformers used as benchmarks for Sub-Saharan Africa’s future transformation efforts are Brazil, Chile,

in manufacturing Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Source: ACET calculations based on data from various international organizations.

Around 60–70% of the population

in Africa lives in rural areas, mostly

dependent on agriculture. So increas- Indeed, in most industrialization release labor to industry, produce

ing agricultural productivity would experiences, the rise in agricultural more food to moderate any hikes in

be a powerful way to raise incomes. productivity allowed agriculture to urban industrial wages, supply raw4

materials for processing in industries, or at least controlled. GDP per depth, this report introduces the

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

increase exports to pay for trans- capita in Sub-S aharan Africa has African Transformation Index (ATI).

formation inputs, and enhance the not yet doubled its level in 1970, The ATI is a composite of the five ele-

domestic market for industrial prod- but for the comparators it has more ments of DEPTH—Diversification,

ucts. With cereal yields now running than q uintupled—a performance Export competitiveness, Produc-

at about 1,500 kilograms per hectare, that African countries should now tivity, Technology upgrading, and

A transforming or a third of the yields of the compar- aspire to. Human economic well-being. Here,

economy would ators, raising agriculture’s productivi- we show country rankings on the

ty has to be a key part of the econom- A transforming economy would ATI and on the five components for

have an increasing

ic transformation agenda. In addition, have an increasing share of the labor two three-year periods centered on

share of the labor to industrialize successfully, produc- force in formal employment as the 2000 and 2010 (averages of 1999–

force in formal tivity in manufacturing in Africa has shares of modern agriculture, man- 2001 and of 2009–11). We take aver-

to rise; manufacturing value added ufacturing, and high-value services ages because given the volatility of

employment as the

per worker is around $11,700 (in 2005 in GDP expand and as entrants to the commodity-dependent econ-

shares of modern US$), or roughly a third of the $36,000 the labor force become more edu- omies of Africa, the values of the

agriculture, for the comparators. cated. The share of formal employ- relevant variables for any particular

ment in the labor force is therefore year could give misleading results.

manufacturing,

Technological upgrading a good indicator for tracking the We show results for the 21 Sub-

and high-value throughout the economy human impact of economic trans- Saharan countries that have the

services in GDP formation (in addition to GDP per required data. Note that the results

expand and as Productivity gains can come capita). For much of Sub-Saharan reflect economic outcomes rather

from more efficient use of exist- Africa, the data are sparse, but the than policy inputs and institutional

entrants to the ing resources and technology to share of formal employment in the environments.

labor force become produce the same goods and ser- labor force is seldom above 25%.

more educated vices, but rising productivity can Contrast that with more than 50% Putting together all of the elements

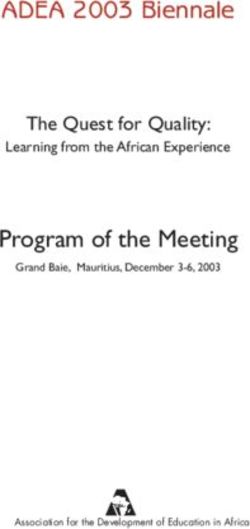

be sustained only through new for the comparators. of DEPTH, the ATI shows Mauritius,

and improved technologies and South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal,

increasing ability to master more Uganda, Kenya, and Gabon as the

sophisticated economic activities. Tracking economic top seven countries on economic

Furthermore, as technology rises transformation—the African transformation in 2010 (figure 2).

in manufacturing, a transforming Transformation Index The middle seven are Cameroon,

economy can produce goods that Madagascar, Botswana, Mozam-

command higher prices on the inter- To track how countries are trans- bique, Tanzania, Zambia, and

national markets. In both production forming through growth with Malawi. The least transformed are

and exports, the shares of medium-

and high-technology manufactures Figure 2 How countries rank on transformation

in Sub-Saharan Africa are generally

MAURITIUS 0

low—at around 12%, less than a SOUTH AFRICA 0

third of the 39% for the comparators. CÔTE D’IVOIRE +1

SENEGAL 1

UGANDA +5

Human well-being KENYA +2

GABON 0

CAMEROON 2

MADAGASCAR +2

Improving human well-being BOTSWANA 5

MOZAMBIQUE +4

involves many factors, including TANZANIA +1

incomes, employment, poverty, ZAMBIA 1

MALAWI +2

inequality, health, and education, BENIN 1

GHANA 7

as well as peace, justice, security, ETHIOPIA +1

and the environment. The two most RWANDA +3

NIGERIA 0

directly related to economic trans- BURUNDI 0

BURKINA FASO 4

formation are GDP per capita and

0 25 50 75

employment. If GDP per capita is

ATI score

rising, and remunerative employ-

ment opportunities are expand-

ing, economic transformation will Note: The 2010 score is the average for 2009–11. The numbers after each country name show the

result in shared prosperity, and change in rank between 2000 and 2010.

income inequality will be reduced Source: ACET research. See annex 1 for the construction of the African Transformation Index.5

Benin, Ghana, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Propelling economic • Identifying and supporting

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

Nigeria, Burundi, and Burkina Faso. transformation in Africa particular sectors, products,

and economic activities in each

The main surprises are Botswana, Again, growth with depth is needed country’s potential comparative

Ghana, and Nigeria. Botswana had to propel and sustain Africa’s eco- advantage.

a stellar record on GDP growth over nomic transformation. It can diver-

1970–2010, raising its per capita sify and technologically upgrade The exact combination and Growth with

GDP to the second highest in Sub- the economy. It can also expand sequencing for the 10 drivers may depth is not

Saharan Africa (after Gabon). But formal jobs and self-employment differ from country to country, and

mechanical. To

its economy is based primarily on and connect with the vast infor- even in the same country it may

the production and exports of raw mal economy to reach small firms change over time. But awareness of pursue it, countries

diamonds—extractives—which we and boost their productivity and how successful countries have used have to develop

do not include in the measures of incomes so that a growing share of the drivers to help them transform

and implement

diversification and export compet- the population can share in the con- can help African countries as they

itiveness. The country has made tinent’s prosperity. And it can link develop their own strategies. This strategies

efforts in recent years to diversi- African producers to global value inaugural African Transformation appropriate to

fy away from raw diamonds by chains and greatly broaden their Report examines the policy options

their circumstances

moving into cutting and polishing, markets. for several of the drivers. Others

but the results have yet to register in will be explored in detail in future

the data. Meanwhile, the economy But growth with depth is not reports. In addition to the 10 drivers

remains very weak in some of the mechanical. To pursue it, countries here, each within the exclusive

key indicators of transformation. have to develop and implement control of national policymakers

For example, the share of manufac- strategies appropriate to their cir- and citizens, progress on regional

turing in GDP is around 4% (11% in cumstances. In doing this they can economic integration will in several

Burkina Faso, at the bottom of the learn from the other countries that tangible ways also provide a tre-

transformation rankings), and cereal have already transformed. Although mendous boost to the economic

yields are about 375 kilograms per there is no formula for econom- transformation efforts of Sub-

hectare (900 kilograms per hectare ic transformation, there is some Saharan countries.

in Burkina Faso). 5 Ghana’s poor agreement on policies and institu-

showing in 2010 results mainly from tions that have been important in

a steady decline in manufacturing driving the transformation of suc- The state and the private

production, export diversification, cessful countries. Beyond peace and sector—partners in

and export competitiveness over security, these include: transformation

the decade. It also relies consid- • Increasing state capacity for

erably on unprocessed mineral macroeconomic management, Pursuing economic transformation

exports (gold and bauxite). Nige- public expenditure manage- well requires the state to be effec-

ria’s poor showing also reflects its ment, and guiding economic tive in providing an environment

extreme dependence on producing transformation. that is conducive to businesses in

and exporting oil. • Creating a business-friendly general, as well as in collaborating

environment that also fosters with the private sector and facili-

Uganda, Mozambique, and Rwanda effective state-business consul- tating its upgrading of technolo-

made the most progress on trans- tation and collaboration on eco- gies and capability to competitively

formation, each improving its rank nomic transformation. produce promising new goods and

by three places or more. Kenya, • Developing people’s skills for a services, and to enter new export

Madagascar, Malawi, Côte d’Ivoire, modern economy. markets. Though the list of the roles

Tanzania, and Ethiopia improved • Boosting domestic private is long, capacity limitations require

their rankings by one or two places. savings and investments. African countries to focus on the

The worst deteriorations were in • Attracting private foreign ones essential for transformation.

Ghana and Botswana. Ghana fell investment.

seven places, and Botswana five • Building and maintaining physi- Managing the economy to enable

places, between 2000 and 2010. cal infrastructure. businesses to flourish

Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Senegal, • Promoting exports.

and Zambia also dropped in rank- • Facilitating technology acquisi- Economic transformation can take

ings. (The special feature at the end tion and diffusion. place only in an environment of

of this overview shows rankings on • Fostering smooth labor- prudent macroeconomic poli-

the individual DEPTH subindexes.) management relations. cies, which is also conducive to6

economic activities and entrepre- goods in and out of a country also shows that state involvement

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

neurship, particularly by private in a timely and efficient manner in the economy can block private

business. This requires policy action is critical to transformation in a initiative, introduce inefficiencies,

on many fronts: globalized world, particularly for and retard economic progress. Eco-

smaller countries that need exter- nomic transformation thus requires

• Macroeconomic and exchange nal trade, as in Africa. The state getting the balance right between

Central to a rate management. Fiscal and therefore has to increase the effi- the state and private enterprise and

country’s economic monetary policies should be ciency of airports, seaports, and having effective mechanisms for

pursued in ways that ensure that border crossings. And simplifying the two to collaborate and support

transformation their impacts on inflation, wages, customs procedures can speed each other.

is learning about interest rates, and exchange rates clearing times, essential for par-

and introducing are positive for promoting rapid ticipation in global value chains, Although countries differ, Sub-

growth in GDP, jobs, and exports. and control corruption. Saharan Africa generally is well

new technologies,

This requires constant monitor- endowed with cheap labor and

processes, ing of policy impacts and a will- • Streamlining regulation. To abundant natural resources. And

products, and ingness to make timely policy encourage entrepreneurship its relative advantage in these areas

corrections where necessary. and innovation, the state should is likely to increase over time. So it

services—and

regulate only what it should would make sense for Sub-Saharan

breaking into • Planning and managing public and can regulate. That can save countries to build their transforma-

foreign markets spending. The state has to money for both the firms and tion strategies around leveraging

balance its spending on short- the government: the only losers their relative advantages in labor

run consumption and long-run will be corrupt officials. and natural resources. They should

investment, with expenditures in seek over time to move to higher

line with the overall transforma- • Beefing up statistics. The state value products by upgrading skills,

tion program. It has to appraise has to produce timely and high- learning about and introducing new

and select public projects pro- quality social and economic sta- technologies, processes, products,

fessionally—and carry them out tistics to enable it to formulate and services—and breaking into

efficiently to ensure value for better plans, monitor implemen- new foreign markets. They should

money, with timely monitoring tation, and change course where also aim at making the transforma-

and reporting. necessary. Such statistics also tion process in the modern sectors

help the private sector in plan- more labor intensive to expand

• Making public procurement deliver ning and deciding investments— the opportunities for productive

value for money by reducing cor- and the citizenry in holding gov- employment.

ruption. The gap between avail- ernments to account.

able resources and those needed The spark that ignites economic

for transformation in Africa is Guiding transformation by setting transformation is likely to come

huge. African countries there- a national vision and strategy from the formal or modern sectors.

fore cannot afford to waste their But the informal or traditional

public resources through corrupt In addition to the tasks above sectors should not be forgotten.

and inefficient procurement related to good economic manage- Conscious efforts should be made

processes that enrich a few pol- ment, policymakers can take more to promote links between them

iticians and officials and retard proactive steps to spark transforma- and the modern sectors spear-

progress on transformation that tion. Central to a country’s econom- heading the economic transforma-

would benefit all. The state thus ic transformation is learning about tion. These would include assisting

has to put in place transpar- and introducing new technologies, small enterprises and those in the

ent and efficient procurement processes, products, and services— informal sector to upgrade their

systems. Indeed, if governments and breaking into foreign markets. capability to become competitive

spent as much time cleaning Domestic firms in African countries suppliers to the expanding modern

up procurement and executing (as in all late-developing countries sector firms—and implementing

projects efficiently as they did throughout history) face difficult programs that encourage modern

chasing finance from donors challenges in doing this. A favorable firms to source inputs from them. A

and other external sources, the business environment can help but similar approach would encourage

impacts could be transformative. is seldom sufficient. History shows a new class of commercial farmers

that, among successful transform- and agroprocessors to source inputs

• Administering ports and customs ers, the state has helped business from traditional smallholder farmers

and controlling corruption. Moving meet its many challenges. But it as through outgrower schemes.7

The foregoing considerations to produce and implement plans Social Development Board of Thai-

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

should all inform the formulation of that are both coherent and realistic. land, under the office of the prime

a clear national vision and strategy. Many plans are produced by plan- minister, and India’s Planning Com-

The state guides the formulation of ning agencies using experts from mission, chaired by the prime min-

the vision and strategy or plan but outside government, with little input ister and run by a vice chair with a

consults closely with private firms, and commitment of senior staff cabinet rank.

which in the end will be the main from other government ministries A national vision

implementers. This requires a state and agencies. A planning ministry, if Building centers of excellence and strategy

that has the drive and capacity to separate from the finance ministry,

play the traditional state roles in seldom has much influence in ensur- The functions critical to the state’s can clarify the

economic management and to col- ing that expenditures in the plan support to economic transforma- interrelationships

laborate with business in pursuing are actually reflected in the budget, tion have to be performed well, so among government

specific transformation initiatives. making planning a paper exercise. the institutions in charge of these

branches and

Having planning and finance under functions and the people that

A national vision and strategy can one ministry could solve this, but it work in them have to be first class. between relevant

inspire citizens and mobilize their could also create the problem that The institutions include the central government and

support for sacrifices in the early the short-term exigencies of finance bank, the ministry of finance, the

private activities—

stages of economic transforma- swamp the long-term studies and national planning agency (where

tion. The strategy can also clarify reflection needed for planning. different from the ministry of thus improving

the interrelationships among gov- finance), the ministry of trade and information,

ernment branches and between In addition, many government ini- industry, the ministry of land and understanding,

relevant government and private tiatives to support economic trans- agriculture, the ministry of edu-

a ctivities—thus improving infor- formation will necessarily have to cation and skills development, and coordination

mation, understanding, and coor- involve several government min- the national statistical service, the among key actors

dination among key actors in the istries and agencies. This requires investment and export promotion in the economy

economy. And the targets in the effective coordination within gov- agencies, the national development

strategy can make it possible for ernment. Only an office whose bank, the export finance facility (if

citizens and businesses to hold gov- authority is accepted by ministers different from the national devel-

ernment accountable for results. and staff in other ministries and opment bank), the administration

agencies can ensure this takes of customs, and the management of

Sub-S aharan countries have in place. In some cases that would seaports and international airports.

recent years begun to take the lead be a minister of planning, finance,

in producing medium- and long- or trade and industry whom col- For a leader serious about promot-

term plans more focused on the leagues see as senior to them. In ing economic transformation, the

growth and transformation of their others it would be an office directly appointments to head the core

economies. In Ethiopia, Ghana, and under the president, vice president, functions should be based on com-

Rwanda the new plans result from or prime minister. Seen as having a petence and the ability to deliver

the country taking more ownership higher rank, the office can convene results; they should not be used

of the poverty reduction strategy various arms of government, assign for patronage or to repay politi-

process. In Kenya and Nigeria they tasks, monitor implementation, and cal debts. The same applies to the

emerge from a separate process. discharge rewards and sanctions as directors and deputy directors

Too often, however, the expendi- occasions warrant. The office also in these ministries and agencies.

tures in annual budgets bear little needs top-class professional staff Sounds obvious, but look at the

relation to the priorities in the to earn and maintain the respect of lineups in some African countries.

medium- or long-term plans—and other units in the government. Early

even less when separate govern- archetypes would be South Korea’s Many African countries now have

ment ministries or agencies carry Economic Planning Board, Taiwan’s a talent pool—in government, in

out the two functions. (China) Council for Economic Plan- business, in think tanks, and in the

ning and Development, and Sin- diaspora—that leaders could tap

Coordinating plan gapore’s Economic Development if they really want to pursue trans-

implementation Board, initially under the Ministry formation. The senior staff should

of Finance and later the Ministry be empowered and supported to

One of the biggest challenges that of Trade and Industry. Later ones run these core ministries and agen-

many Sub-Saharan countries face in include Malaysia’s Economic Plan- cies. Such implementation bodies

promoting economic transformation ning Unit, in the prime minister’s as customs, ports management,

is coordination within government office, the National Economic and and the investment and export8

promotion agencies could be made policies and programs affect them; chaired by the president or prime

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

into semi-autonomous statutory and third, design and monitor spe- minister, operates in ways that

bodies with terms and conditions of cific transformation initiatives. move in this direction. Mauritius

service that are different from those has a well developed consultation

in the civil service, set to attract Several Sub-Saharan countries have mechanism between the govern-

the best. Appointments should be made some progress on the first ment and business through the

Reformed core based on contracts, and continued objective, spurred partly by the Joint Economic Council, an umbrel-

ministries and employment should be based on poverty reduction strategy process, la business organization.

performance, as specified in the but business participation could

agencies could contracts, not on changes in gov- be deepened beyond consultation. The third objective—deliberating

serve as centers ernments or on the whims of polit- A good example in this direction on selected transformation initia-

of excellence and ical leaders. was the process used by Kenya tives, the instruments to promote

to prepare its Vision 2030 Plan. them, and the monitoring and com-

beacons for others

It will take time to change the The National Economic and Social pliance mechanisms—is not well

to emulate in the culture in the whole public service Council that spearheaded its prepa- developed. This stems in part from

public service and to find the resources to provide ration comprised business people the low capacity and organizational

adequate remuneration. However, and public officials. weakness in government to trans-

the reformed core ministries and late general objectives in economic

agencies could serve as centers of On the second objective, several plans to specific initiatives to discuss

excellence and beacons for others Sub-Saharan countries have public- with business. In addition, some

to emulate in the public service. private forums that meet periodi- governments, despite the rhetoric,

And if these centers help promote cally (say, once or twice a year) to still have not embraced business

faster economic growth and trans- discuss issues affecting the private as a very important partner with

formation, resources would be gen- sector. A good beginning, but these knowledge and expertise that the

erated to pay for reform in the rest large meetings are too infrequent, state can and must tap.

of the public service. and they tend to be long on cer-

emony and short on fact-based How to ensure that strong collabo-

Fostering state-business discussions of issues. And in some ration among the government, busi-

collaboration countries, various business associ- ness, and organized labor does not

ations submit presentations to the degenerate into “cronyism” among

While the state would contribute government during budget prepa- politicians, senior bureaucrats, big

to economic transformation, it is ration time, advancing their par- business people, and labor bosses?

entrepreneurial firms, both large and ticular interests. These exchanges Academics and staff from indepen-

small, that will spearhead the cre- between the government and busi- dent economic think tanks should

ation of employment and the pro- ness are welcome, but they could be members of the deliberative

duction and distribution of goods be improved. bodies. And the decisions by these

and services that drive economic bodies should be made available,

transformation. That is why govern- The discussions should be substan- together with their rationale, to the

ment should create mechanisms tive reviews of the impacts of gov- public (through the secretariat’s

that bring it into regular contact with ernment policies and actions on website and the media).

business to seek its inputs. Orga- the general environment for busi-

nized labor is another key part of the ness operations and how it could The incentive packages to promote

collaboration, particularly in democ- be improved—not focus on special the initiatives and the associated

racies where it can exercise the favors for particular business sub- eligibility and performance crite-

right to strike. Also in democracies, groups. The meetings should be ria should also be published. And

popular support for the economic chaired by the head of government beneficiaries and performance

transformation vision is necessary or the central coordinating agency. should be made public periodically.

to gain acceptance for the difficult A secretariat should prepare anal- In countries with strong and inde-

reforms that may be required. yses and reports to be discussed pendent parliaments, the legisla-

at the meeting and follow up on ture can insist on the information

State -business engagements decisions taken and monitor their being made available—and use

should pursue three objectives: implementation by the relevant it for accountability. Civil groups,

first, get business inputs on agencies. including the media, could also

medium- and long-term nation- demand the information and use

al plans; second, seek feedback Kenya’s National Economic and it for accountability. And foreign

from business on how government Social Council, with meetings donors supporting economic9

transformation could support com- what’s possible. Exporting also consciously develop other sources

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

petent civil groups and think tanks exposes domestic entrepreneurs to of international competitive advan-

to enhance their ability to ensure global tastes, standards, technolo- tage, particularly skills, even as they

transparency and accountability. gies, and best practices—providing ride their current low-wage advan-

opportunities for learning about tage unto the initial steps of the

Embarking on governance reforms new products, services, processes, manufactured exports ladder.

and technologies that they could The prospects

None of the foregoing will happen introduce at home. The prospects of Sub-Saharan coun- of Sub-Saharan

without solid progress on gover- tries are rather bright for manufac-

nance reforms—indeed, several The pathways to export expansion turing exports based on processing countries are

countries are only beginning to are determined by the relative com- agricultural and extractive resourc- rather bright for

embark on reforms. parative advantages and disadvan- es (oil, gas, and minerals), which manufacturing

tages of countries (box 1). Broadly they have in relative abundance.

exports based

True, there have been great strides speaking, Africa’s relative advan- Many development successes have

in democratic transitions, the media tages are abundant low-wage labor begun by working and transform- on processing

are doing more as watchdogs and abundant land and natural ing local natural resources. But agricultural

exposing corruption and checking resources. By mid-century almost processing tends to be intensive

and extractive

abuses of power, and civil society a fifth of the global population of in capital and skills, so it would

groups are promoting transparen- working age will be in Africa. Half demand more of the factors Sub- resources (oil, gas,

cy and accountability. But politi- the world’s acreage of cultivable Saharan countries lack, and less of and minerals),

cal and economic governance will land not yet cultivated is in Africa. the untrained labor they have in which they have in

determine how well countries meet And Africa’s known reserves of abundance. These constraints can

their transformation challenges and oil, gas, and minerals, with further be overcome through skill develop- relative abundance

realize their full potential in moving exploration over the next decades, ment and with deliberate programs

forward. They will have to consoli- are set to grow dramatically. Sub- to develop capabilities in more

date their recent progress in gover- Saharan countries are, however, at labor-intensive industries upstream

nance. And they will have to seal the a relative disadvantage in capital and downstream. In agricultur-

cracks in their young democratic (including physical infrastructure), al processing, developing links to

systems, dealing with entrenched technology, and skills. So it makes smallholders and improving their

corruption, costly electoral pro- sense for them to leverage their productivity and access to markets

cesses, and weak accountability current comparative advantage will also reduce rural poverty, as

mechanisms. Especially daunting while upgrading their capabilities in with oil palm in Malaysia.

will be formulating and implement- the disadvantaged areas.

ing a long-term transformation Some Sub-Saharan countries also

vision and strategy across elector- To leverage their abundant labor have good export prospects in ser-

al cycles in polarized multiparty resources into a competitive advan- vices, particularly tourism based

democracies. tage in labor-intensive manufactur- on the attractions of their varied

ing exports, Sub-Saharan countries cultures, wildlife, landscapes, and

need to address their relative cost sunny beaches. Also promising

Promoting exports disadvantages, particularly with are teleservices, such as business

China and other Asian countries. process outsourcing based on fairly

Exports provide the foreign Staying competitive in the export of low wages and medium skills—for

exchange to import the machinery labor-intensive manufactures based the U.K and U.S. markets for Anglo-

and technology necessary for tech- on a low-wage advantage will, phone Africa and the French market

nological upgrading. Over time, however, become more difficult. for Francophone Africa. Again,

higher earnings from exports make Re-shoring and near-shoring, multi- skills development, in addition to

it easier to finance investments national companies from developed investments and policy actions, will

to change a country’s underlying countries are relocating manufac- be needed to turn potential into

factor endowments (such as skills turing back to, or near, their home a competitive advantage on the

and technological capacity) and bases. And such technological global market.

thereby its comparative advantage. developments as three-dimension-

Exposed to competition on interna- al printing and three-dimensional Prospective world demand sug-

tional markets, exporters have to packaging of integrated circuits are gests that while the traditional

increase their efficiency in produc- likely to reduce the demand for low- markets of Europe, Japan, and the

tion and marketing, in the process skilled assembly workers. African United States will continue to be

showing other domestic producers countries will therefore need to important, Sub-Saharan countries10

African Transformation Report 2014 | Overview

Box 1 Four pathways to transformation

Chapters 5–8 of the African of factories owned by others. first rungs of the global manufac-

Transformation Report elaborate Under this triangle manufacturing turing ladder.

on four pathways to transform- the retailers and marketers at the

ing African economies: labor- top of the garment global value Attracting foreign direct invest-

intensive manufacturing; agro- chains have no direct relationship ment (FDI) for component

processing; oil, gas, and minerals; with producers. These buyers assembly in Africa, particularly

and tourism. now look for full-package suppli- home appliances, will be abetted

ers who can deliver orders based by large and buoyant markets,

Labor-intensive manufacturing— on their designs or specifications. supported by the growing middle

still the first rung? Brand manufacturers (such as Levi class, and perhaps more import-

Strauss) still have direct relation- ant by integrating the national

Sub-Saharan countries can lever- ships with factories in low-wage markets. Only Nigeria and South

age their abundant labor and low countries, either through factories Africa have a large enough

wages to enter the competitive they own or through production- domestic market to attract a

production and export of man- sharing arrangements with facto- market-seeking FDI (as many

ufactured goods. Garment man- ries owned by others. heavy home appliance manufac-

ufacturing has been one of the turers tend to be). But progress on

first rungs that countries climb on Most Sub-Saharan garment man- regional integration would enable

their way up the manufacturing ufacturers cannot now provide other countries to join them.

ladder. It is labor intensive. The the full-package services that The Southern African Develop-

capital requirements are generally retailers at the top of the garment ment Community comprises 15

modest. The technology and skills global value chains look for. Capa- member states with a market of

requirements are fairly simple. bilities in most African countries almost 250 million consumers, a

And there is also local demand for are generally in the cut, make, and combined GDP of $649 billion,

the products. trim stage—and in niche African and per capita income of $2,617.

designs. So entering the garment The 15 import $213 billion worth

Most global exports of garments global value chains for large-scale of goods, and their exports are

are now controlled by global exports would have to be through valued at around $207 billion. Sim-

value chains. At the head of the production sharing with a brand ilarly, the Economic Community of

chains are the buyers—large manufacturer or through working West African States comprises 15

retailers, marketers, and branded with a larger supplier in triangle member states, with a market of

manufacturers. Mostly in Europe manufacturing. about 320 million people, a com-

and the United States, they focus bined GDP of $396 billion, and per

on design and marketing. Retail- In addition to garments, com- capita income of around $1,245.

ers and marketers such as Wal- ponent assembly was one of the With an open market in each bloc,

Mart, the Gap, and Liz Claiborne main ways for poor countries to FDI manufacturers would become

contract out their designs and leverage their low-wage labor to more interested in the blocs as

requirements to suppliers in low- industrialize in the second half possible sites for manufacturing

wage countries, mostly in Asia. of the twentieth century. Korea, plants. And member countries—

Some of these suppliers (such as Hong Kong SAR (China), Singa- even the small ones—would

those in Hong Kong SAR [China]) pore, and Taiwan (China), then with good policies, adequate

have factories in several low- Malaysia, and now China have infrastructure, and logistics stand

wage countries and coordinate been able to ride on the assembly a better chance of becoming loca-

the sourcing of inputs, the pro- of simpler consumer electronics tions for FDI manufacturing.

duction of the garments, and the (radios, televisions, cellphones,

exports to buyers. Others (such as computers, computer peripher- Agroprocessing—natural potential

Li & Fung Ltd.) no longer produce, als) and home appliances (fans,

focusing instead on sourcing from refrigerators, air conditioners, Agriculture has the potential to

and coordinating a wide network microwave ovens) to enter the contribute greatly to economic

(continued)You can also read