Gender, Climate Change and Health

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

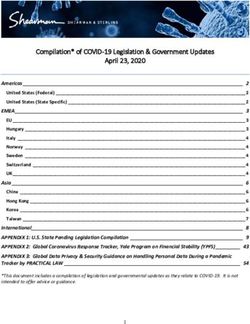

Contents

Acknowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Abbreviations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Executive summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1. Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.1 Health and climate change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

1.2 Health, gender and climate change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

2. Impacts: health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .9

2.1 Meteorological conditions and human exposure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

3. Impacts: social and human consequences of climate change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

3.1 Migration and displacement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

3.2 Shifts in farming and land use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

3.3 Increased livelihood, household and caring burdens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

3.4 Urban health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

4. Responses to climate change . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

4.1 Mitigation actions and health co-benefits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

4.2 Adaptation actions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

5. Conclusions, gaps in understanding and issues for urgent action . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32Acknowledgements

This discussion paper is the result of collaboration between the Department of Gender, Women

and Health (GWH) and the Department of Public Health and Environment (PHE) of the World

Health Organization (WHO) to systematically address gender equality in work relating to

climate change and health. WHO acknowledges the insight and valuable contribution to this

paper provided by Surekha Garimella who prepared the initial draft, working under the guidance

of Peju Olukoya from GWH and Elena Villalobos Prats and Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum from

PHE. Tia Cole contributed to the conceptualization of the paper, and Lena Obermayer and Erika

Guadarrama provided additional inputs to strengthen specific aspects of the paper.

Helpful comments were contributed by the following colleagues in WHO: Shelly Abdool,

Jonathan Abrahams, Avni Amin, Roberto Bertollini, Sophie Bonjour, Nigel Bruce, Carlos Dora,

Marina Maiero, Eva Franziska Matthies, Maria Neira, Tonya Nyagiro, Chen Reis and Marijke

Velzeboer Salcedo.

We also thank the following for expert reviews and feedback: Sylvia Chant, Professor of

Development Geography, London School of Economics; Sari Kovats, Senior Lecturer in

Environmental Epidemiology, Department of Social and Environmental Health Research,

Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; Carlos

Felipe Pardo, Colombia Country Director, Institute for Transportation and Development; Deysi

Rodriguez Aponte, Environmental Management, TRANSMILENIO S.A.; and Lucy Wanjiru

Njagi, Programme Specialist, Gender, Environment and Climate Change, United Nations

Development Programme.

We gratefully acknowledge the input of the students of the Master Study Programme on Health

& Society, International Gender Studies, Berlin School of Public Health and der Charité, during

the seminar on Gender, Climate Change and Health, facilitated by WHO in January 2010.

Acknowledgements 1Abbreviations

CSW Commission on the Status of Women

DSM-IV Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

WHA World Health Assembly

WHO World Health Organization

2 Gender, Climate Change and HealthExecutive summary

There is now strong evidence that the earth’s climate is changing rapidly, mainly due to human

activities. Increasing temperatures, sea-level rises, changing patterns of precipitation, and more

frequent and severe extreme events are expected to have largely adverse effects on key determi-

nants of human health, including clean air and water, sufficient food and adequate shelter.

The effects of climate on human society, and our ability to mitigate and adapt to them, are

mediated by social factors, including gender. This report provides a first review of the interactions

between climate change, gender and health. It documents evidence for gender differences in

health risks that are likely to be exacerbated by climate change, and in adaptation and mitigation

measures that can help to protect and promote health. The aim is to provide a framework to

strengthen World Health Organization (WHO) support to Member States in developing health

risk assessments and climate policy interventions that are beneficial to both women and men.

Many of the health risks that are likely to be affected by ongoing climate change show gender

differentials. Globally, natural disasters such as droughts, floods and storms kill more women

than men, and tend to kill women at a younger age. These effects also interact with the nature of

the event and social status. The gender-gap effects on life expectancy tend to be greater in more

severe disasters, and in places where the socioeconomic status of women is particularly low.

Other climate-sensitive health impacts, such as undernutrition and malaria, also show important

gender differences.

Gender differences occur in health risks that are directly associated with meteorological hazards.

These differences reflect a combined effect of physiological, behavioural and socially constructed

influences. For example, the majority of European studies have shown that women are more at

risk, in both relative and absolute terms, of dying in heatwaves. However, other studies have also

shown that unmarried men tend to be at greater risk than unmarried women, and that social

isolation, particularly of elderly men, may be a risk factor.

Differences are also found in vulnerability to the indirect and longer-term effects of climate-

related hazards. For example, droughts in developing countries bring health hazards through

reduced availability of water for drinking, cooking and hygiene, and through food insecurity.

Women and girls (and their offspring) disproportionately suffer health consequences of

nutritional deficiencies and the burdens associated with travelling further to collect water.

In contrast, in both developed and developing countries, there is evidence that drought can

disproportionately increase suicide rates among male farmers.

Women and men differ in their roles, behaviours and attitudes regarding actions that could help

to mitigate climate change. Surveys show that in many countries men consume more energy

than women, particularly for private transport, while women are often responsible for most of

the household consumer decisions, including in relation to food, water and household energy.

There is also evidence of gender differences in relation to the health and safety risks of new

technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Such information could support more targeted,

more effective efforts to bring about more healthy and environmentally friendly policies.

These differences are also reflected in the health implications of potential greenhouse gas mitigation

policies. For example, inefficient burning of biomass in unventilated homes releases high levels of

Executive summary 3black carbon, causing approximately 2 million deaths a year, mainly of women and children in

the poorest communities in the world. The black carbon from such burning is also a significant

contributor to local and regional warming. At the household level, women are sometimes critical

decision-makers in terms of consumption patterns and therefore the main beneficiaries of access

to cleaner energy sources.

Resources, attitudes and strategies to respond to weather-related hazards often differ between

women and men. For example, studies in India have shown that women tend to have much lower

access to critical information on weather alerts and cropping patterns, affecting their capacity

to respond effectively to climate variability. The same study showed that when confronted with

long-term weather shifts, men show a greater preference to migrate, while women show a greater

preference for wage labour.

Evidence from case studies suggests that incorporation of a gender analysis can increase the

effectiveness of measures to protect people from climate variability and change. In particular,

women make an important contribution to disaster reduction, usually informally through

participating in disaster management and acting as agents of social change. Many disaster-

response programmes and some early warning initiatives now place particular emphasis on

engaging women as key actors.

There are important opportunities to adapt to climate change and to enhance health equity.

Approaches to adaptation have evolved from initial infrastructure-based interventions to a more

development-oriented approach that aims to build broader resilience to climate hazards. This

includes addressing the underlying causes of vulnerability, such as poverty, lack of empowerment,

and weaknesses in health care, education, social safety nets and gender equity. These are also

some of the most important social determinants of health and health equity.

Gender-sensitive assessments and gender-responsive interventions have the potential to enhance

health and health equity and to provide more effective climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Gender-sensitive research, including collection, analysis and reporting of sex-disaggregated data,

is needed to better understand the health implications of climate change and climate policies.

However, there is already sufficient information to support gender mainstreaming in climate

policies, alongside empowerment of individuals to build their own resilience, a clear focus on

adaptation and mitigation, a strong commitment (including of resources), and sustainable and

equitable development.

“Climate change affects every aspect of society, from the health of the global economy to the

health of our children. It is about the water in our wells and in our taps. It is about the food on

the table and at the core of nearly all the major challenges we face today.”I

I UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. Opening remarks to the World Business Summit on Climate Change,

Copenhagen, Denmark, 24 May 2009 (http://www.un.org/apps/news/infocus/sgspeeches/search_full.

asp?statID=500).

4 Gender, Climate Change and Health1. Background

Gender impacts of climate change have been identified as an issue requiring greater attention by

the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW).II Gender norms, roles and relations (Box 1)

are important factors in determining vulnerability and adaptive capacity to the health impacts of

climate change (Box 2). Women’s and men’s vulnerability to the impact of extreme climate events

is determined not only by biology but also by differences in their social roles and responsibilities

(Easterling, 2000; Wisner et al., 2004). Although they vary, these roles and responsibilities exist

in all societies. The expectation that women fulfil their roles and responsibilities as carers of

their families often places extra burdens on them during extreme climate events. The expected

role of men as economic providers for their families often places extra burdens on them in the

aftermath of such events.

Box 1: Definition of sex and gender

In this document “sex” refers to the biological and physiological characteristics of women

and men, and “gender” refers to the socially constructed norms, roles and relations that

a given society considers appropriate for men and women. Gender determines what is

expected, permitted and valued in a woman or a man in a determined context.

Source: WHO (2011a).

Box 2: Definition of climate change

Climate has always varied due to natural influences; however, there is now strong evidence

that human actions, principally the burning of fossil fuels, are the main drivers of the

recent increase in global temperatures and also affect precipitation patterns and extreme

weather events.

This document follows the definition adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change (IPCC), in which “climate change” refers to any change in climate over time,

whether due to natural variability or as a result of human activity. This usage differs from

that in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which

defines “climate change” as “a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly

to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in

addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods”.

Source: IPCC (2001a).

II Fifty-second session of the Commission on the Status of Women, 25 February to 7 March 2008 (http://www.

un.org/womenwatch/daw/csw/52sess.htm).

Background 5At the 2007 World Health Assembly (WHA), Member States of the World Health Organization

(WHO) adopted Resolution WHA 60.25 on the integration of gender analysis and actions into

the work of WHO at all levels (WHO, 2007). A year later, at the 2008 WHA, 193 WHO Member

States committed through Resolution 61.19 to a series of actions to confront the health risks

associated with climate change (WHO, 2008a).

The overall aim of this work is to provide a framework for gendered health risk assessment

and adaptation/mitigation actions in relation to climate change. This aims to strengthen WHO

support to Member States in developing standardized country-level health risk assessments and

climate policy interventions that are beneficial to both women and men.

This report therefore adopts a risk-assessment approach in considering the existing evidence

for gender differences in vulnerability. Climate change is a long-term process, acting against

a background of shorter-term climate variability and many other influences on health. Under

these circumstances, direct statistical attribution of even very large gender differences in health

effects would generally require high-quality meteorological, health and other data collected over

many years, and will therefore only be possible for a minority of effects, in specific locations.

In contrast, there is strong evidence of gender differences in the health impacts of short-term

climate variability and climate-sensitive conditions, such as malnutrition and incidence of

infectious diseases. We use this information to assess likely gender differences in health risks

and responses over the longer time periods associated with climate change.

1.1 Health and climate change

Effects of climate change on health will impact on most populations in the coming decades and

put the lives and well-being of billions of people at increased risk (Costello et al, 2009). IPCC

states that “climate change is projected to increase threats to human health”.

Climate change can affect human health through a range of mechanisms. These include

relatively direct effects of hazards such as heatwaves, floods and storms, and more complex

pathways of altered infectious disease patterns, disruptions of agricultural and other supportive

ecosystems, and potentially population displacement and conflict over depleted resources,

such as water, fertile land and fisheries (Pachauri & Reisinger, 2007).

There is no clear dividing line between these divisions, and each pathway is also modulated by

non-climatic determinants and human actions.

1.2 Health, gender and climate change

Limited case examples and research have analysed and highlighted the links between gender

norms, roles, relations and health impacts of climate change (Box 3). The framework in Figure

1, adapted from the synthesis report of the International Scientific Congress on Climate Change

(McMichael & Bertollini, 2009), is used in this paper to structure the available information on

the gendered health implications of climate change, according to (i) the direct and indirect health

impacts of meteorological conditions; (ii) the health implications of potential societal effects

of climate change, for example on livelihoods, agriculture and migration; and (iii) capacities,

resources, behaviours and attitudes related to health adaptation measures and mitigation policies

that have health implications.

6 Gender, Climate Change and HealthBox 3: Why gender and health?

The distinct roles and relations of men and women in a given culture, dictated by that

culture’s gender norms and values, give rise to gender differences.

Gender norms, roles and relations also give rise to gender inequalities – that is, differences

between men and women that systematically value one group often to the detriment of the

other. The fact that, throughout the world, women on average have lower cash incomes

than men is an example of gender inequality.

Both gender differences and gender inequalities can give rise to inequities between men

and women in health status and access to health care. For example:

• a woman cannot receive needed health care because norms in her community prevent her

from travelling alone to a clinic;

• an adolescent boy dies in an accident because of trying to live up to his peers’ expectations

that young men should be “bold” risk-takers, including on the road.

In each of these cases, gender norms and values, and resulting behaviours, are negatively

affecting health. But gender norms and values are not fixed and can evolve over time, can

vary substantially from place to place, and are subject to change. Thus, the adverse health

consequences resulting from gender differences and gender inequalities are not static.

They can be changed.

Source: WHO (2011b).

Background 7Figure 1: Effects of climate change on human health and current responses:

a gendered perspective

Impact pathways Current responses

Meteorological Human/social Mitigation actions Adaptation actions

conditions consequences of

exposure climate change

Examples: Examples: Examples: Examples:

• Warming • Displacement • Alternative energy • Addressing water

• Humidity • Shift in farming and • Accessible clean shortage

• Rainfall/drying land use water • Crop substitution

• Winds • Community

education on early

• Extreme events warning systems and

hazard management

Examples of impact outcomes and responses that are gendered in their effects

• Injury/death from • Migration • Hydropower – leading • Unexpected nutrient

hunger to more snail hosts for deficiencies

• Exacerbation of schistosomiasis

• Epidemics malnutrition • Impacts of water

• Mental health issues • Cleaner air – less quality

• Increased violence cardiorespiratory

• Water-related against women and • Fewer deaths in

diseases (gendered

infections girls extreme events

profiles)

Source: Adapted from McMichael & Bertollini (2009).

8 Gender, Climate Change and Health2. Impacts: health

2.1 Meteorological conditions and human exposure

There is good evidence showing that women and men suffer different negative health

consequences following extreme events such as floods, windstorms, droughts and heatwaves. A

review of census information on the effects of natural disasters across 141 countries showed that

although disasters create hardships for everyone, on average they kill more women than men,

or kill women at a younger age than men. These differences persist in proportion to the severity

of disasters and depend on the relative socioeconomic status of women in the affected country.

This effect is strongest in countries where women have very low social, economic and political

status. In countries where women have comparable status to men, natural disasters affect men

and women almost equally (Neumayer & Plümper, 2007The same study highlighted that physical

differences between men and women are unlikely to explain these differences, and social norms

may provide some additional explanation. The study also looked at the specific vulnerability of

girls and women with respect to mortality from natural disasters and their aftermath; the study

found that natural disasters lower the life expectancy in women more than in men. Since life

expectancy of women is generally higher than that of men, natural disasters actually narrow

the gender gap in life expectancy in most countries. The research also confirmed that the effect

on the gender gap in life expectancy is proportional to the severity of disasters – that is, major

calamities lead to more severe impacts on women’s life expectancy compared with that of men.

The study verified that the effect of the gender gap on the gender gap in life expectancy varied

inversely in relation to women’s socioeconomic status. This highlights the socially constructed

and gender-specific vulnerability of women to natural disasters, which is integral to everyday

socioeconomic patterns and leads to relatively higher disaster-related mortality rates in women

compared with men (Neumayer & Plümper, 2007).

2.1.1 Heatwaves and increased hot weather

Warming and increased humidity have already contributed to observed increases in some health

risks, and these can be anticipated to continue in the future.

Direct consequences

Several studies, mainly in cities in developed countries, have shown that death rates increase as

temperatures depart, in either direction, from the optimum temperature for that population.

There is therefore concern that although warmer temperatures may lead to fewer deaths in

winter, they are likely to increase summer mortality. For example, it is estimated that a 2 °C

rise would increase the annual death rate from heatwaves in many cities by approximately two-

fold (McMichael & Bertollini, 2009). There is evidence that vulnerability varies by sex: more

women than men died during the 2003 European heatwave, and the majority of European studies

have shown that women are more at risk, in both relative and absolute terms, of dying in such

events (Kovats & Hajat, 2008). There may be some physiological reasons for an increased risk

among elderly women (Burse, 1979; Havenith et al., 1998). Social factors can also be important

in determining the risk of negative impacts of heatwaves. For example, in the United States

of America, elderly men seem to be more at risk than women in heatwaves, and this was

Impacts: health 9particularly apparent in the Chicago events of July 1995 (Semenza, 1996; Whitman et al., 1997).

This vulnerability may be due to the level of social isolation among elderly men (Klinenberg,

2002). In Paris, France the heatwave-related risk increased for unmarried men but not for

unmarried women (Canoui-Poitrine et al., 2006). Men may also be more at risk of heatstroke

mortality because they are more likely than women to be active in hot weather (CDC, 2006).

Indirect consequences

Rising temperatures may increase the transmission of malaria in some locations, which already

causes 300 million acute illnesses and kills almost 1 million people every year (WHO, 2008b).

Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to malaria as they are twice as “appealing” as

non-pregnant women to malaria-carrying mosquitoes. A study that compared the relative

“attractiveness” to mosquitoes of pregnant and non-pregnant women in rural Gambia found that

the mechanisms underlying this vulnerability during pregnancy is likely to be related to at least

two physiological factors. First, women in the advanced stages of pregnancy (mean gestational

age 28 weeks or above) produce more exhaled breath (on average, 21% more volume) than their

non-pregnant counterparts. There are several hundred different components in human breath,

some of which help mosquitoes detect a host. At close range, body warmth, moist convection

currents, host odours and visual stimuli allow the insect to locate its target. During pregnancy,

blood flow to the skin increases, which helps heat dissipation, particularly in the hands and

feet. The study also found that the abdomen of pregnant women was on average 0.7 °C hotter

than that of non-pregnant women and that there may be an increase in the release of volatile

substances from the skin surface and a larger host signature that allows mosquitoes to detect

them more readily at close range. Changes in behaviour in pregnant women can also increase

exposure to night-biting mosquitoes: pregnant women leave the protection of their bednet at

night to urinate twice as frequently as non-pregnant women. Although the important role of

immunity and nutrition is recognized, it is suggested that physiological and behavioural changes

that occur during pregnancy could partly explain this increased risk of infection (Lindsay, 2000).

Maternal malaria increases the risk of spontaneous abortion, premature delivery, stillbirth and

low birth weight.

Evidence for connections between weather and pre-eclampsia varies between studies. Some

studies have looked at links between meteorological conditions and the incidence of eclampsia

in pregnancy; the studies found increased incidence during climatic conditions characterized

by low temperature, high humidity or high precipitation, with an increased incidence especially

during the first few months of the rainy season (Agobe et al., 1981; Crowther, 1985; Faye et al.,

1991; Bergstroem et al., 1992; Neela & Raman, 1993; Obed et al., 1994; Subramaniam, 2007). A

study from Kuwait found that incidence of pre-eclampsia was high in November, when the

temperature was low and the humidity high (Makhseed et al., 1993). On the other hand, the

incidence of pregnancy-induced hypertension was highest in June, when the temperature

was very high and the humidity at its lowest. Another study, from the southern province of

Zimbabwe, evaluated hypertensive complications during pregnancy and observed a distinctive

change in the incidence of pre-eclampsia during the year. These changes corresponded with

the seasonal variation in precipitation, with incidence increasing at the end of the dry season

and in the first months of the rainy season. This observed relationship between season

and the occurrence of pre-eclampsia raises new questions regarding the pathophysiology

of pre-eclampsia. Possible explanations could be the impact of humidity and temperature

on production of vasoactive substances. Dry and rainy seasons, through their influence

10 Gender, Climate Change and Healthon agricultural yields, may also impact on the nutritional status and play a role in the

pathophysiology of the women (Wacker et al., 1998).

2.1.2 Windstorms and tropical cyclones

Direct consequences

In the 1991 cyclone disasters that killed 140 000 people in Bangladesh, 90% of victims were

women (Aguilar, 2004). The death rate among people aged 20–44 years was 71 per 1000 women,

compared with 15 per 1000 men (WEDO, 2008). Explanations for this include the fact that more

women than men are homebound, looking after children and valuables. Even if a warning is

issued, many women die while waiting for their relatives to return home to accompany them to a

safe place. Other reasons include the sari restricts the movement of women and puts them more

at risk at the time of a tidal surge, and that women are less well nourished and hence physically

less able than men to deal with these situations (Chowdhury et al., 1993; WEDO, 2008).

In May 2008, Cyclone Nargis came ashore in the Ayeyarwady Division of Myanmar. Among the

130 000 people dead or missing in the aftermath, 61% were female (Care Canada, 2010).

Indirect consequences

Women, young people, and people with low socioeconomic status are thought to be at

comparatively high risk of anxiety and mood disorders after disasters (Norris et al., 2002). One

study of anxiety and mood disorder (as defined by the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; DSM-IV) after Hurricane Katrina found the incidence

was consistently associated with the following factors: age under 60 years; being a woman;

education level lower than college completion; low family income; pre-hurricane employment

status (largely unemployed and disabled); and being unmarried. In addition, Hispanic people

and people of other racial/ethnic minorities (not including non-Hispanic black people) had

a significantly lower estimated incidence of any disorder compared with non-Hispanic white

people in the New Orleans area, as well as a significantly lower estimated prevalence of post-

traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the remainder of the sample. These same associations have

been found in community epidemiological surveys in the absence of disasters, suggesting that

these associations might be related to pre-existing conditions (Galea et al., 2007). A follow-up

study that looked at patterns and correlates of recovery from hurricane-related PTSD, broader

anxiety and mood disorders and suicidal behaviour found a high prevalence of hurricane-

related mental illness widely distributed in the population nearly 2 years after the hurricane

(Kessler et al., 2008).

2.1.3 Sea-level rises, heavy rain and flooding

Increasing temperatures are contributing to sea-level rises, and precipitation is becoming heavier

and more variable in many regions, potentially increasing flood risks and multiple associated

health hazards. There has, however, been only limited systematic research and gender analysis on

the health outcomes of flooding (Few et al., 2004). It is important to recognize that vulnerability

to flooding is differentiated by social dimensions. In both developing and industrialized nations,

health and other impacts may fall disproportionately on women, children, people with disabilities

and elderly people (Few et al., 2004).

Impacts: health 11Direct consequences

A report on the health effects of climate change in the United Kingdom showed that age- and

gender-related information on flood deaths is incomplete. Published reviews have shown,

however, that men are much more at risk of drowning than women, probably due to taking more

risky or “heroic” behaviour (Kovats & Allen, 2008) (Box 4).

Saline contamination is expected to be aggravated by climate change and sea-level rises

(Nicholls et al., 2007). A paper on saline contamination of drinking water in Bangladesh

indicated that large numbers of pregnant women in coastal areas are being diagnosed with pre-

eclampsia, eclampsia and hypertension. Although local doctors and community representatives

have blamed the problem on increased salinity, no formal epidemiological study has been done

(Khan et al., 2008).

Box 4: How gender norms, roles and relations explain the

differences in fatality between women and men in floods in Nepal

In 1993 a severe flash flood devastated the district of Sarlahi in the southern plains of

Nepal. After an unprecedented 24-hour rainfall, a protective barrage on the Bagmati River

was washed away during the night, sending a wall of water more than 7 metres high crash-

ing through communities and killing more than 1600 people. Two months later, a follow-up

survey assessed the impact of the flood. This survey was unusual in that an existing pro-

spective research database was available to verify residency before the flood. As part of a

large community-based nutrition programme, longitudinal data existed on children aged

2–9 years and their parents from 20 000 households, about 60% of the households in the

study area. The survey established age- and sex-specific flood-related deaths among more

than 40 000 registered participants (including deaths due to injury or illness in the weeks

after the flood). Flood-related fatalities were 13.3 per 1000 girls aged 2–9 years, 9.4 per

1000 boys aged 2–9 years, 6.1 per 1000 adult women and 4.1 per 1000 adult men. The

difference between boys’ and girls’ fatalities existed mostly among children under 5 years

of age. This possibly reflects the gender-discriminatory practices that are known to exist in

this poor area: when hard choices must be made in the allocation of resources, boys are

more often the beneficiaries. This could be reflected in rescue attempts as much as in the

distribution of food and medical attention.

Source: Adapted from Bartlett (2008).

Indirect consequences

In Bangladesh and the eastern region of India, where the arsenic contamination of groundwater

is high, flooding intensifies the rate of exposure among rural people and other socioeconomically

disadvantaged groups (Khan et al., 2003). Studies have also found a negative correlation between

symptoms of arsenic poisoning and specific socioeconomic factors, in particular educational

and nutritional status (Mitra et al., 2004; Rehman et al., 2006; Maharajan et al., 2007). Health

problems resulting from arsenic poisoning include skin lesions, hardening of the skin, dark spots

on the hands and feet, swollen limbs and loss of sensation in the hands and legs (UNICEF, 2008).

12 Gender, Climate Change and HealthIn the south-west region of Bangladesh, waterlogging (local increases in groundwater levels) has

emerged as a pressing concern with health consequences. Women are often the primary caregivers

of the family, shouldering the burden of managing and cooking food, collecting drinking water,

and taking care of family members and livestock. Because of these responsibilities, women often

spend time in waterlogged premises and other settings. Research reveals that waterlogging

severely affects the health of women in affected communities. Women are forced to stay close to

the community and drink unhygienic water, as tube wells frequently become polluted. Pregnant

women have difficulty with mobility in marooned and slippery conditions and thus are often

forced to stay indoors. Local health-care workers have reported that there are increasing trends

of gynaecological problems due to unhygienic water use. Since men are often out of the area

in search of work, they are frequently not as severely affected as their female counterparts.

Waterlogging, therefore, has given rise to differential health effects in women and men in coastal

Bangladesh (Neelormi et al., 2009).

Socially constructed roles also influence the individual disaster responses of men. Within Latino

cultures, for instance, expectations of male “heroism” require men to act courageously, thus

forcing them into risky behaviour patterns in the face of danger and making them more likely to

die in an extreme event. In contrast, women’s relative lack of decision-making power may pose

a serious danger itself, especially when it keeps them from leaving their homes in spite of rising

water levels, waiting for a male authority to grant them permission or to assist them in leaving

(Bradshaw, 2010).

Girls and women may experience decreased access to important life skills due to gender norms

or expectations around behaviours deemed “appropriate”. For example, in some Latin American

and Asian countries, women and girls are often not taught to swim, for reasons of modesty

(Aguilar, 2004). In the South Asian context, social norms that regulate appropriate dress codes in

accordance with notions of modesty may hinder women and girls from learning to swim, which

can severely reduce their chances of survival in flooding disasters (Oxfam, 2005).

Possible health consequences of hazards associated with flooding and typhoons include stress-

related illness and risk of malnutrition related to loss of income and subsistence, which are

known to have a strong gender dimension (FAO, 2001, 2002; Cannon, 2002). Studies from Viet

Nam found that stress factors were apparent at the household level. People interviewed in cities

in the Mekong Delta referred to increased anxiety, fears or intra-household tension as a result

of the dangers and damage associated with flooding and its livelihood impacts. Interviewees in

the central provinces referred to food shortages and hunger potentially resulting from crop and

income losses following destructive floods and typhoons (Few & Tran, 2010).

In flooded areas of Bangladesh, women are often the last people to receive assistance, as some

men push them out of the way in the rush for supplies. Women who have lost clothing in the flood

are unable to enter public areas to access aid because they can not cover themselves sufficiently

(Skutsch, 2004). A further example of this is the loss of culturally appropriate clothing, which

inhibits women from leaving temporary shelters to seek medical care or obtain essential resources

(Neumayer & Plümper, 2007).

Impacts: health 132.1.4 Drought

Direct consequences

Globally, fresh water resources are distributed unevenly, and areas of most severe physical

water scarcity are those with the highest population densities. The health impacts of drought

and their gender dimensions may be exacerbated further by climate change. Shifting rainfall

patterns, increased rates of evaporation and melting of glaciers, and population and economic

growth are expected to increase the number of people living in water-stressed water basins

from about 1.5 billion in 1990 to 3–6 billion by 2050 (Arnell, 2004). Almost 90% of the burden

of diarrhoeal disease is attributable to lack of access to safe water and sanitation (Prüss-Üstün

et al., 2008; WHO, 2009a); reduction in the availability and reliability of fresh water supplies

is expected to amplify this hazard.

In arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid areas, drought already presents a serious threat to the

well-being and health of the local populations. Extended periods of drought are linked not only

to water shortages and food insecurity but also to increased risk of fires, decreased availability

of fuel, conflicts, migration, limited access to health care and increased poverty. Few studies are

available on the consequences of droughts for human health, but all of them point to differing

impacts on men and women.

In times of water scarcity women have little choice but to carry water home from unsafe sources,

including streams and ponds that are likely to be contaminated. This can lead to water-related

diseases such as diarrhoeal disease, which in developing countries is a leading cause of death

among children under 5 years of age (WHO & UNICEF, 2005). Moreover, when water is scarce,

hygienic practices are commonly sacrificed to more pressing needs for water, such as drinking

and cooking. The lack of hygiene can be followed by diseases such as trachoma and scabies, also

referred to as “water-washed diseases” (WaterAid, 2007). Almost half of all urban residents in

Africa, Asia and Latin America are already victims of diseases associated with poor water and

sanitation facilities (WHO & UNICEF, 2006).

Indirect consequences

Droughts and drying can lead to social instability, food insecurity and long-term health problems

and can damage or destroy related livelihoods (Pachauri & Reisinger, 2007).

In most developing countries, women are intrinsically tied to water. They are responsible for

collecting, storing, protecting and distributing water. For women, long journeys walking to the

nearest wells and carrying heavy pots of water not only causes exhaustion and damage to bones

but also is accompanied by opportunity costs, such as time that could be spent productively going

to school or working.

A study on drought management in Ninh Thuan, Viet Nam showed that 64% of respondents

agreed that recurring disasters have differential impacts on women and men, and 74% of

respondents believed that women were more severely affected than men by drought, due to

differing needs for water. Women collect water from sources that are increasingly further away

as each drought takes its toll. With fewer water sources nearby, women often walk long distances

to fetch drinking water. Women also cook, clean, rear children and collect firewood, so they cope

with enormous physical burdens on a daily basis (Oxfam, 2006).

14 Gender, Climate Change and HealthWomen and girls fetch water in pots, buckets and more modern narrow-necked containers,

which are carried on the head or the hip. A family of five people needs approximately 100 litres

of water, weighing 100 kg, each day to meet its minimum needs. Women and children may need

to walk to the water source two or three times each day. The first of these trips often takes place

before dawn, which involves sacrificing sleeping hours, which can pose a serious strain on health.

During the dry season in rural India and Africa, 30% or more of a woman’s daily energy intake is

spent fetching water. Carrying heavy loads over long periods of time causes cumulative damage

to the spine, the neck muscles and the lower back, thus leading to early ageing of the vertebral

column (Mehretu & Mutambirwa, 1992; Dasgupta, 1993; Page, 1996; Seaforth, 2001; Research

Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology, 2005; Ray, 2007). More research is needed

to uncover the negative health implications of the burden of daily carrying of water, as it seems

to fall outside of the conventional categories of waterborne, water-washed and water-related

ailmentsDrought increases the family’s physiological need for water and also results in greater

distances travelled to the water source. According to available data, the quantity of collected

water per capita is reduced drastically if the walk to a water source takes 30 minutes or longer

(WHO & UNICEF, 2005). As a result, the quantity of collected water often does not even cover

the basic human physiological requirements. This puts women in a very difficult position, as

in many societies women are socially responsible for the family’s water supply. According to a

study on water needs and women’s health in Ghana, women who maintain traditional norms

are particularly vulnerable during water scarcity, as they often give priority to their husbands,

ensuring that the man’s water needs are met before their own (Buor, 2003).

The stresses of lost incomes and associated indebtedness can spill over into mental health

problems, despair and suicide among men. There is some empirical evidence linking drought

and suicide among men in Australia (Nicholls et al., 2006). This negative health outcome among

Australian rural farmers has been linked to stoicism and poor health-seeking behaviour, which

is an intrinsic element of rural masculinity (Alston & Kent, 2008; Alston, 2010). In India, there

has been consistent reporting of increased suicide among poor male farmers following periods

of droughts in contiguous semi-arid regions (Behere & Behere, 2008; Nagaraj, 2008).

Impacts: health 153. Impacts: social and human

consequences of climate change

3.1 Migration and displacement

Climate change can affect migration (Box 5) in three distinct ways. First, the effects of warming

and drying in some regions will reduce agricultural potential and undermine “ecosystem services”

such as clean water and fertile soil. Second, the increase in extreme weather events – in particular,

heavy precipitation and resulting flash or river floods in tropical regions – will affect ever more

people and may generate mass displacement. Finally, sea-level rises are expected to destroy

extensive and highly productive low-lying coastal areas that are home to millions of people, who

will have to relocate permanently. In this context, health challenges can involve, among other

things, the spread of communicable diseases and an increase in the prevalence of psychosocial

problems due to stress associated with migration. The human and social consequences of climate

change in this context are studied very poorly, if at all.

Box 5: Definition of environmental migrants used in the

context of this document

“Environmental migrants are persons or groups of persons who, for compelling reasons of

sudden or progressive changes in the environment that adversely affect their lives or living

conditions, are obliged to leave their habitual homes, or choose to do so, either temporarily

or permanently, and who move either within their country or abroad”.

Source: International Organization for Migration (2007).

There are few studies on the linkages between extreme events and domestic and sexual violence.

However, a report that looked into the issue of recovery after the Indian Ocean tsunami in

2004 indicated that women and children were very vulnerable in these situations. Although the

occurrence of tsunamis is not attributable to weather or climate change, one can assume that

in the aftermath of extreme events and the ensuing displacement of groups of people that may

occur, scenarios similar to the post-tsunami conditions are plausible.

The World Disaster Report recognizes the widespread consensus that “women and girls are at

higher risk of sexual violence, sexual exploitation and abuse, trafficking, and domestic violence in

disasters” (IFRC, 2007). Women who were subjected to violence before a disaster are more likely

to experience increased violence after the disaster, or they may become separated from family,

friends and other potential support and protective systems. After a natural disaster, women are

more likely to become victims of domestic and sexual violence and may avoid using shelters as a

result of fear (Davis et al., 2005; IFRC, 2007).

Psychological stress is likely to be heightened after disasters, particularly where families

are displaced and have to live in emergency or transitional housing. Overcrowding, lack of

privacy and the collapse of regular routines and livelihood patterns can contribute to anger,

frustration and violence, with children and women most vulnerable (Bartlett, 2008).

16 Gender, Climate Change and HealthAdolescent girls report especially high levels of sexual harassment and abuse in the aftermath of

disasters and complain of the lack of privacy in emergency shelters (Bartlett, 2008).

3.2 Shifts in farming and land use

For farmers, insecurity due to erratic rainfall and unseasonal temperatures can be compounded

by a comparative lack of assets and arable land, and in some cases lack of rights to own the

land they till. This means that credit available for suitable agriculture technology (e.g. watering

implements, climate appropriate seed varieties, non-petroleum fertilizers, energy-efficient

building design) is limited, as is their capacity to rebuild post-natural hazards in this context.

Loss of biodiversity can compound insecurity because many rural women in different parts of

world depend on non-timber forest products for income, traditional medicinal use, nutritional

supplements in times of food shortages, and a seed bank for plant varieties needed to source

alternative crops under changing growing conditions. Thus, loss of biodiversity challenges

the nutrition, health and livelihood of women and their communities (Boffa, 1999; Pisupati &

Warner, 2003, Roe et al., 2006; Arnold, 2008).

Nutritional status partly determines the ability to cope with the effect of natural disasters

(Cannon, 2002). Women are more prone to nutritional deficiencies because of their unique

nutritional needs, especially when they are pregnant or breastfeeding, and some cultures have

household food hierarchies. For example, in South Asia and South-East Asia, 45–60% of women

of reproductive age are underweight and 80% of pregnant women have iron deficiencies. In sub-

Saharan Africa, women carry greater loads than men but have a lower intake of calories because

the cultural norm is for men to receive more food (FAO, 2001). For girls and women, poor

nutritional status is associated with an increased prevalence of anaemia, pregnancy and delivery

problems, and increased rates of intrauterine growth retardation, low birth weight and perinatal

mortality. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in places where iron

deficiency is prevalent, the risk of women dying during childbirth can be increased by as much

as 20% (FAO, 2002).

Pregnant and lactating women face additional challenges, as they have an increased need for

food and water, and their mobility is limited. Globally, at any given time, an average of 18–20%

of the reproductive age population is either pregnant or lactating (Röhr, 2007). These biological

factors create a highly vulnerable population within a group that is already at risk (Shrade &

Delaney, 2000).

3.3 Increased livelihood, household and caring burdens

Apart from the nutritional impacts of livelihood, household and caring burdens, decline in food

security and livelihood opportunities can also cause considerable stress for men and boys, given

the socially ascribed expectation that they should provide economically for the household. This

can lead to mental illness in some cases. It has been recognized that men and boys are less likely

than women and girls to seek help for stress and mental health issues (Masika, 2002).

Women and girls are generally expected to care for the sick, including in times of disaster and

environmental stress (Brody et al., 2008). This limits the time they have available for income

generation and education, which, when coupled with the rising medical costs associated with

Impacts: social and human consequences of climate change 17family illness, heightens levels of poverty, which is in turn a powerful determinant of health. It

also means they have less time to contribute to community-level decision-making processes,

including on climate change and disaster risk reduction. In addition, being faced with the burden

of caring for dependents while being obliged to travel further for water and firewood makes

women and girls prone to stress-related illnesses and exhaustion (CIDA, 2002; VSO, 2006).

Women and girls may also face barriers to accessing health-care services due to poor control over

economic and other assets to avail themselves of health care, and cultural restrictions on their

mobility that may prohibit them from travelling to seek health care.

Increased time spent collecting water means a decrease in available time for education and places

women and girls at risk of violence when travelling long distances. A lower education status

implies more constraints for women to access health information or early warning systems as they

are developed. This also means that girls and women have decreased access and opportunities

in the labour market, increased health risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth, and less

control over their personal lives.

Elderly women may have heavy family and caring responsibilities that cause stress and fatigue,

while also preventing wider social and economic participation. Their incomes may be low

because they can no longer take on paid work or other forms of income generation. They may

have inadequate understanding of their rights to access community and private-sector services.

Even when they are aware of these services, nominal financial resources for clinic visits and drugs

may be out of their reach. Access is further restricted for older women and older men living in

rural areas, who are often unable to travel the long distances to the nearest health facility.

Older men are particularly disadvantaged by their tendency to be less connected than women to

social networks and therefore unable to seek assistance from within the community when they

need it (Consedine & Skamai, 2009).

3.4 Urban health

An individual’s place of residence and their status within that place are important determinants

of health. Urbanization is a dominant trend, with more people living in marginal conditions in

cities in developing countries. Urban populations have distinct vulnerabilities to climate related

health hazards (Campbell-Lendrum & Corvalan, 2007).

Limited access to land in rural areas, conflict, divorce and unemployment forces increasing

numbers of women into living in marginalized urban and peri-urban areas and slums. These

dwellings are often situated on ground with particular environmental risks, such as hillsides and

low-lying plots.

The rising rate of female-headed households in urban/peri-urban areas results in a shift of urban

sex ratios and feminization of urban poverty. Poverty, exposure of dwelling, and managing on

their own the disproportionate daily burden of infrastructural needs such as waste management,

fuel, water and sanitation make urban female heads of households particularly vulnerable to

natural disasters (Chant, 2007).

18 Gender, Climate Change and Health4. Responses to climate change

“Climate change will affect, in profoundly adverse ways, some of the most fundamental

determinants of health: food, air, water.”III

“Climate change could vastly increase the current huge imbalance in health outcomes. Climate

change can worsen an already unacceptable situation that the Millennium Development Goals

were explicitly and intricately designed to address.”IV

The international response to climate change is governed by the UNFCCC. The stated aim of the

UNFCCC is to avoid the “adverse effects” of climate change, which it defines not only as impacts

on “natural and managed ecosystems or on the operation of socio-economic systems” but also

on “human health and welfare” (UN, 1992). Although climate change is widely considered to be

one of the most significant threats to future human development, it is often analysed through an

exclusively environmental or economic perspective, without adequately considering the extent

to which it affects all aspects of human societies.

According to Article 4.f. of the UNFCCC, before parties propose new adaptation or mitigation

initiatives, they shall assess its health benefits or negative impacts together with environmental

and economic considerations. This article recognizes the importance of considering health

and other social implications, including gender equality, when developing impact assessments

and not basing decisions only on potential economic and environmental impacts. The correct

implementation of this UNFCCC provision will bring opportunities to advance the sustainable

development agenda.

In contrast, poorly designed policies could easily undermine gender equality, climate and

health equity goals and reduce public support for their implementation. An essential aspect for

achieving health equity and climate goals is therefore a commitment to intersectoral action to

achieve “health equity and climate change in all policies” (Walpole et al., 2009).

Specific policies need to be carefully designed and assessed. Integrated assessment methods

that consider the gendered range of effects on health and health equity can maximize synergies

and optimize trade-offs between competing priorities. At the design stage, implementing

safeguards and flanking measures, such as recycling revenue from carbon pricing measures,

towards health outcomes for disadvantaged groups can help avoid or reduce inequitable effects

(Walpole et al., 2009).

4.1 Mitigation actions and health co-benefits

The UNFCCC states that mitigation measures bringing about societal benefits should be

prioritized. Health is one of the clearest of the societal benefits. Measures undertaken to reduce

greenhouse gas emissions in the household energy, transport, food and agriculture, and electricity

generation sectors, in both low- and high-income settings, can have ancillary health benefits (or

“health co-benefits”), which are often substantial.

III Chan (2007).

IV Ibid.

Responses to climate change 19There is growing interest in the links between gender and mitigation efforts. To develop effective

mitigation policies and programmes that will also impact on key health outcomes, it is crucial

that equity and gender perspectives are integrated into relevant policy and programme design.

There is accumulating evidence of important differences in the circumstances, attitudes and

behaviours of women and men in relation to decisions on mitigation policies and their relation to

health. For example, a study that looked at gender differences in energy consumption patterns and

greenhouse gas emissions among single households in Greece, Sweden, Norway and Germany

found that the average single man consumed more energy than the average single woman in all

four countries studied. The largest difference in absolute energy use between single men and

single women was in the category of transport (primarily due to cars). In the study the average

single man spent more money on vehicles and fuel than did the average single woman. Men

also spent more money on buying cars and other vehicles than did women, resulting in higher

indirect energy use by men. Women on the other hand consistently used more energy than

men in consumption categories such as food, hygiene, household effects and health, although

the differences were small (Räty & Carlsson-Kanyama, 2010). Studies for the Organisation for

Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have shown that women make over 80% of

consumer decisions and are more likely to be sustainable consumers, with a higher propensity

to recycle and placing a higher value on efficient energy compared with men (OECD, 2008).

Such differences are likely to be particularly important in relation to choices such as food,

because decisions such as moderating meat and dairy consumption can help to reduce the large

contribution of agriculture to greenhouse gas emissions and at the same time bring very large

health benefits.

Gender differences extend beyond individual consumer choices and also apply to attitudes to

wider policy decisions. For example, a large survey in Australia examined attitudes towards

carbon capture and storage from power plants and other stationary sources (IPCC & TEAP,

2005), which has been advocated as a potential measure to reduce greenhouse gases but which

also raises environmental, health and safety concerns related to possible leakage of carbon

dioxide. The survey showed women were less accepting of carbon capture and storage and more

concerned than men about safety, risk and effectiveness (Miller et al., 2007).

When devising and applying policy instruments for energy efficiency or emission reductions, it

is important to know the target groups. If women and men differ regarding their use of energy

and emission profiles, then the mitigation policy instruments should reflect these differences

to achieve the maximum benefits from the policies (Miller et al., 2007). The integration of a

gender analysis component will help in understanding how gender norms, roles and relations

determine the different patterns of obtaining and using fuel, energy and water by both women

and men. The following sections examine these interactions for two of the sectors that make

the largest contribution to greenhouse gas emissions and health outcomes, and that have the

strongest evidence of gender-specific differences.

4.1.1 Access to energy

One of the main responsibilities of women in developing countries is ensuring energy supply and

security at the household level. It is therefore crucial to involve women in the design, negotiation

and implementation of clean energy choices that have the potential to improve health and well-

being, both through reduced risks to health, and through savings in time and financial resources

20 Gender, Climate Change and HealthYou can also read