ERepository @ Seton Hall - Seton Hall University

←

→

Page content transcription

If your browser does not render page correctly, please read the page content below

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 2021 The Dormant Seizure Doctrine and Its Effect on Race Disparities Joseph Alter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Law Commons

The Dormant Seizure Doctrine and Its Effect on Race Disparities

By: Joseph Alter

INTRODUCTION

In most circumstances, the seizure of a person is easy to spot. When one thinks of police

“seizing” a suspect, perhaps images of a police officer handcuffing or tackling a suspect to the

ground come to mind. That would be accurate, as these types of physical restraints

understandably fall within the United States Supreme Court’s definition of “seizure.” 1 But what

about the less obvious methods of police controlling or attempting to control the body of a

suspect? If police are simply asking questions of someone, is that a seizure? What if they ask

questions for hours without telling the person they can leave? What if they shoot or attempt to

shoot a suspect, but he or she manages to escape? What if a suspect gives police permission to

search them, but the permission is given under duress or coercive circumstances? These

questions represent the more difficult side of seizure doctrine, and the Court has at one point or

another attempted to answer them all, with confusing and often unreasonable results.

The Supreme Court’s seizure doctrine becomes more complex when examined in the

light of the current national dialogue the United States is having about law enforcement’s

disparate treatment of minority communities—the Black community in particular. Ample

research shows higher arrest, conviction, and imprisonment rates for people of color. I n today’s

world, in which there is a seemingly endless series of cases in which Black individuals are killed

1California v. Hodari, D., 499 U.S. 621, 626 (1991). (A Fourth Amendment seizure requires “either physical force

or, where that is absent, submission to assertion of authority”).

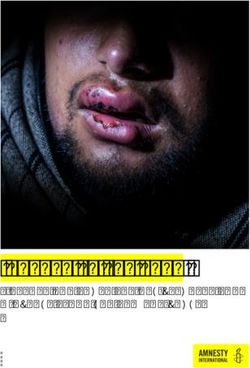

2or injured due to the excessive or unnecessary force used on them by police2 , many are calling on

the Court to do something to alleviate this unjust and heartbreaking reality. One of the primary

ways it can do so is to include race as a factor when determining certain types of seizures in

order to reflect the reality that minorities are treated differently by police, and as a result, they

understand and experience interactions with the police differently.

The Supreme Court’s attempts at defining what is and is not a seizure have engendered

and fostered a system in which law enforcement can not-so-covertly discriminate based on race,

but the Court has taken any chances of discussing race in the seizure context completely off the

table.3 All of the Court’s rulings on this point have operated to treat all Americans the same in

their interactions with law enforcement. Despite statistics and current events undercutting that

notion, the Court has not changed its tune, and shows very little signs of doing so in the future.

An in-depth analysis of where American seizure law came from, how it developed, how it has

disadvantaged minority communities, and what to do about it is imperative.

I. ROOTS OF SEIZURE DOCTRINE

In order to examine or analyze modern day seizure law, it is necessary to look into the history

of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This is because the United States

Supreme Court decides current seizure cases based largely on what the Founding Fathers thought

about the issue4 . The rationale behind the Fourth Amendment’s enactment continues to color

how and when a seizure is deemed unconstitutional. Examining the history of the Fourth

Amendment reveals that some of the modern seizure practices deemed constitutional may not

2Some recent examples include George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, Jacob Blake, Elijah McClain,

Philando Castile, Daniel Prude, Duante Wright, Samuel DuBose, Alonzo Smith, Atatiana Jefferson, and many more.

3 Torres v. Madrid, 141 S. Ct. 989 (2021).

4 Virginia v. Moore, 553 U.S. 164, 175 (2008).

3fully match up with the expectations the Framers had in mind when they argued for and wrote

the amendment.

A. The History of the Fourth Amendment

Despite consisting of just over fifty words, the Fourth Amendment has and continues to be a

highly debated and controversial area of law, and our understanding and interpretation of it has

changed depending on the decade and the makeup of the Supreme Court. The Amendment, in its

entirety, states:

The right of the people to be secured in their persons, houses, papers, and

effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated,

and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or

affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the

persons or things to be seized.5

The key word in the amendment is “unreasonable”, and its placement suggests

that the Framers did not intend to prohibit all searches and seizures, but rather only ones

they considered to be unreasonable. This is where the debate begins and never truly

ends, as a court’s determination of what exactly it considered to be unreasonable in

1789 can mean the difference between a defendant’s freedom, incarceration, or ability

to obtain a civil remedy in 2021. But this determination is no easy task, and to

accomplish it requires an analysis of why the Framers felt the need to enact the Fourth

Amendment in the first place.

The idea that people should be secure in their own houses, which birthed the

Fourth Amendment, did not start with the Founding Fathers. Like much of American

common law, Fourth Amendment jurisprudence can be traced back to England. One of

the first English cases to deal with the issue of safeguarding the home from government

5 U.S. Const., amend. IV.

4interference was Semayne’s Case in 1604, in which Sir Edward Coke declared, “the

house of every one is to him as his castle and fortress, as well as for his defence against

injury and violence as for his repose.”6 Despite this recognition, Semayne’s Case

allowed for the breaking and entering of a home in many circumstances, as long as the

owner or tenant of the home was notified in advance of the sheriff’s arrival, and a

request was made by the sheriff to enter once he did arrive. 7 One of these circumstances

was “execution of the King’s process”, as one of the holdings of the case was that “the

liberty of the house does not hold against the King.” 8 This meant that sheriffs could still

enter a home for essentially any reason, as long as it was on behalf of the King and they

announced their presence before entering. This paved the way for writs of assistance, or

general warrants, created by Parliament in the 17 th Century.9 These warrants authorized

government officials to enter private homes and businesses to search and seize

contraband, with essentially zero limitations on the time or scope of the search and

seizure.10

As one might expect, the notion that a sheriff or soldier may enter a home at any

time and search and seize anything on behalf of the King was not met with much

enthusiasm. In the 1760s, targets of these general warrant searches increasingly started

to sue the officers who conducted them. The most notable of these targets was John

Wilkes, a British radical and member of Parliament who penned publications critical of

King George III.11 One of these publications was “The North Briton,” a newspaper that

6 5 Co. Rep. 91a, 77 Eng. Rep. 194 (K.B. 1603).

7 Id. This is the origin of the modern-day “knock and announce” rule.

8 Id.

9 George Elliott Howard, Preliminaries of the Revolution, 1763-1777, 73 (1906).

10 13 & 14 Car. 2, c. §5(2) (1662).

11 Jack Lynch, Wilkes, Liberty, and Number 45. Colonial Williamsburg Journal. (2003).

https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/summer03/wilkes.cfm .

5Wilkes wrote anonymously.12 After reading a particularly critical issue of the

newspaper, the King ordered the issuance of general warrants which authorized the

arrest of the printers, publishers, and authors of “The North Briton”, without identifying

any of them by name.13 Wilkes sued the King’s messengers for trespassing on his

property and arresting him under a general warrant and encouraged other printers and

publishers who were similarly targeted under the general warrants to do the same.14

One of those publishers was John Entick, an associate of Wilkes whose house

was forcibly broken into by the King’s chief messenger, Nathan Carrington.15

Carrington broke into locked desks and boxes and seized many pamphlets and charts,

causing a great deal of damage.16 Like Wilkes, Entick sued Carrington for trespass and

the resulting litigation, Entick v. Carrington, became a landmark civil liberty case in

Great Britain and a primary motivation for the Founding Fathers to enact the Fourth

Amendment. In Entick, the Court held the general warrants in question to be subversive

“of all comforts of society.”17 Specifically, the court took issue with the absence of

probable cause. The court stated, “The great end, for which men entered into society,

was to secure their property.”18 The U.S. Supreme Court has characterized Entick as “a

great judgment,” “one of the landmarks of English liberty,” and characterized it as a

guide to understanding of what the Framers meant in writing the Fourth Amendment. 19

12 Id.

13 Id.

14 Id.

15 Entick v. Carrington, 2 Wils. K.B 275, 95 Eng. Rep. 807 (1765).

16 Id.

17 Id.

18 Id.

19 Boyd v. United States, 116 U.S. 616, 626 (1886).

6In the American colonies, similar opposition to general warrants were taking

place. Perhaps the most famous of such opposition came from Massachusetts lawyer

James Otis in the 1761 Writ of Assistance Case, in which he advocated on behalf of

Boston merchants petitioning the Massachusetts Superior Court to challenge the legality

of writs of assistance.20 In his scathing attack on the writ, Otis described them as a

“power that places the liberty of every man in the hand of every petty officer. 21 ” He also

brought up what was first mentioned over a century earlier in Semayne’s Case, likening

the right to treat one’s house as their castle:

“A man’s house is his castle, and whilst he is quiet, he is as well guarded as a

prince in his castle. This writ, if it should be declared legal, would totally

annihilate this privilege. Custom house officers may enter our houses when they

please; we are commanded to permit their entry. Their menial servants may enter,

may break locks, bars, and everything in their way; and whether they break

through malice or revenge, no man, no court, can inquire. Bare suspicion without

oath is sufficient. This wanton exercise of this power is not a chimerical suggestion

of a heated brain…What a scene does this open! Every man, prompted by revenge,

ill humor, or wantonness to inspect the inside of his neighbor’s house, may get a

writ of assistance. Others will ask it from self-defense; one arbitrary exertion will

provoke another, until society be involved in tumult and blood.”22

Despite losing the case, Otis was successful insofar as galvanizing the colonies into the

revolutionary spirit. John Adams, who was present in the courtroom for Otis’s speech,

later remarked, “then and there, the child Independence was born.” 23

The idea that general warrants were illegal and an affront to personal liberty

continued, so that when the colonies established independent governments in 1776, many

of them prohibited general warrants. For example, Article I, Section X of the Virginia

20 Richard Morris, “Then and there the child independence was born,” American Heritage Vol. 13, Issue 2, (Feb.

1962). https://www.americanheritage.com/then-and-there-child-independence-was-born.

21 John Adam’s Reconstruction of Otis’s Speech in the Writs of Assistance Case, in The Collected Political Writings

of James Otis, Ed. Richard A. Samuelson (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2015), 11-4.

Http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2703.

22 Id.

23 Richard Morris, Supra Note 18.

7Declaration of Rights, states: “That general warrants, whereby an officer or messenger

may be commanded to search suspected places without evidence of a fact committed, or

to seize any person or persons not named, or whose offense is not particularly described

and supported by evidence, are grievous and oppressive, and ought not to be granted.”24

Massachusetts enacted a similar provision in their declaration of Rights, written by John

Adams, which stressed the “right to be secure from all unreasonable searches, and

seizures of his person, his houses, his papers, and all his possessions.”25 These

prohibitions served as the basis for the language of the Fourth Amendment. Placing that

amendment in the context of the time it was written and all that preceded it, it becomes

clear that the Founding Fathers found searches and seizures to be unreasonable when they

were done arbitrarily or at the whim of a tyrannical government, without any regard to

the personal liberties or freedoms of the subject of the search or seizure. Further, their

adamant opposition to general warrants would seem to indicate a low level of tolerance

for warrantless searches and seizures. Their addition of “probable cause” as necessary in

order to obtain a warrant for searches and seizures seems to drive this point home and

stress how necessary it was to provide limitations on when searches and seizures would

be permissible. However, as Fourth Amendment jurisprudence developed into what we

see in the modern age, an important question must be asked: Has the Court permitted the

very practices the Fourth Amendment was designed to prevent?

II. DEVELOPMENT OF SEIZURE DOCTRINE

While search doctrine has bred an enormous amount of case law, controversy, and

exceptions, seizure doctrine has gotten very little attention in comparison. This is

24 VA. Const. art. 1, § 10.

25 MA. Const. § 1, art. 14.

8especially curious considering the interests involved. Search doctrine is about the privacy

of what we do and keep in our homes, businesses, papers, and effects. Seizure doctrine is

about depriving one of their personal liberty, often accompanied by handcuffs and trips to

the police station. If faced with the choice between liberty and privacy, what would you

chose? Of course, there are instances in which privacy is a higher value than liberty, but

on balance, the idea of being restrained and whisked away should count at least as

equally, if not more than privacy. But given the sizeable disparity in how the Supreme

Court has treated the two doctrines, that does not appear to be the case.

A. Terry v. Ohio: Seizures Absent Probable Cause and Arrest

Until 1968, “probable cause” was an all-or-nothing concept. Either you had it, and

the search/seizure was reasonable, or you didn’t, and the search/seizure was

unreasonable.26 Probable cause was loosely defined by the Supreme Court as “where the

facts and circumstances within the officers’ knowledge, and of which they have

reasonably trustworthy information, are sufficient in themselves to warrant a belief by a

man of reasonable caution that a crime is being committed.”27 This would seem to

comport with the Founders’ thinking in that it would bar arbitrary searches and seizures.

Only where there was a specific basis and sufficient and trustworthy information to

support the search/seizure, would a warrant be issued, making it reasonable.

All of this came to a screeching halt in Terry v. Ohio28 . In that case, Officer

McFadden, a Cleveland Police Officer, witnessed two African American men repeatedly

26 There were some exceptions in which discerning probable cause was tricker. See Draper v. United States, 358

U.S. 307 (1959), in which the issue before the Court was whether an informant’s descriptive tip to police was

sufficient to establish Probable Cause.

27 Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160, 175 (1949).

28 329 U.S. 1 (1968).

9peering into a store window and then walking away to converse with a different man.29

Finding this to be inherently suspicious, the officer approached the men and asked for

their names.30 Richard Terry mumbled something in response, which prompted the

officer to grab him (a seizure), spin him around, and pat the outside of his clothing (a

search).31 The officer testified that this search and seizure was performed to see if Terry

was armed.32 However, based on the judicially defined probable cause standard and the

facts of the case, probable cause did not exist. 33 Thus, the issue in the case was whether it

is always unreasonable for an officer, without probable cause or a warrant, to seize a

person and perform a limited search for weapons. 34 In an 8-1 decision authored by Chief

Justice Warren, the court answered no, and its holding had a tremendous impact on the

Fourth Amendment and future interactions between police officers and civilians. 35

The impact Terry had on the Fourth Amendment cannot be overstated. For the

first time, the Supreme Court held specific searches and seizures to be constitutionally

permissible without a warrant or probable cause, the two ingredients the Founders

deemed necessary in the text of the Fourth Amendment. 36 It went about this by

recognizing that searches and seizures can vary in their level of intrusiveness. In making

that recognition, the Court reasoned that the appropriate test for search and seizure is not

whether there was a warrant or probable cause, but instead by focusing on the nature of

29 Id. at 6.

30 Id.

31 Id. at 7.

32 Id.

33 Had Officer McFadden applied for a warrant and described only what he had seen —two men repeatedly looking

into a store window and walking away to talk to a third man —it likely would not have been issued.

34 Id. at 15.

35 Id. at 29.

36 Id.

10the intrusion as it relates to privacy interests37 . This was because the Court believed some

searches and seizures fall so low on the spectrum as to require a lesser standard than

probable cause.38 Thus, what was later deemed the “reasonable suspicion” standard was

born.39 By creating this standard, and thus a way for police to search and seize people

without probable cause, the Court tampered with the Fourth Amendmen by effectively

driving a wedge between the first clause, which prohibits unreasonable searches and

seizures, and the second, which seemingly allows them only when probable cause exists.

The reasonable suspicion standard is highly deferential to law enforcement. It

allows police to temporarily seize a person and conduct “careful exploration[s] of the

outer surfaces of a person’s clothing all over his or her body in an attempt to find

weapons,”40 as long as the officer can point to some “specific and articulable facts” that

justify their actions41 . Any facts or observations that lead an officer to believe his safety

was in question would likely justify the search and seizure. 42 The Terry Court did not do

much further elaboration on the definition of the reasonable suspicion standard, or how to

know if an officer went too far. In terms of a definition, it said in a later case that the

standard cannot be “readily, or even usefully reduced to a neat set of legal rules.”43 In

terms of evaluating whether an officer did or did not have reasonable suspicion when

conducting a Terry-type search or seizure, the court said it would make this determination

based on “the totality of the circumstances.”44 It also described the reasonable suspicion

37 Id. at 24.

38 Id. at 25.

39 Despite being famous for creating the “reasonable suspicion” standard, the Terry opinion never mentions those

words.

40 Id. at 16.

41 Id. at 21.

42 Id. at 30.

43 United States v. Sokolow, 490 U.S. 1, 7 (1989).

44 Id.

11standard as “obviously less demanding than that for probable cause,” and requiring

“considerably less” proof of wrongdoing.45 In another case, the court said all that is

necessary for reasonable suspicion is “some minimal level of objective justification.” 46

The Court has also conceded that “In allowing such detention, Terry accepts the risk that

officers may stop innocent people.”47 By making it easy for police officers to satisfy

reasonable suspicion, the Court gave them a tremendous amount of power to stop and

seize people on the street. Yale Kamisar, a constitutional law professor and author,

explains that “Terry established a spongy test, one that allowed the police so much room

to maneuver and furnished the courts so little basis for meaningful review, that the

opinion must have been the cause for celebration in a good number of police stations.” 48

Terry impacted more than just probable cause. The case also had significant

effects on how the Fourth Amendment should apply to seizures. This is because for the

first time, The Supreme Court recognized that a person can be seized short of being

arrested.49 Chief Justice Warren believed a Fourth Amendment seizure to occur

“whenever a police officer accosts an individual and restrains his freedom to walk

away.”50 The Chief Justice specified a bit further in dicta, stating that “only when the

officer, by means of physical force or show of authority, has in some way restrained the

liberty of a citizen may we conclude that a ‘seizure’ has occurred.” Despite the first

judicial recognition of a seizure as something short of an arrest, the Terry Court raised

more questions than answers. The Court concluded, “We thus decide nothing today

45 Id.

46 Ins v. Delgado, 466 U.S. 210, 217 (1984).

47 Illinois v. Wardlow, 528 U.S. 119, 126 (2000).

48 Yale Kamisar, The Warren Court and Criminal Justice: A Quarter-Century Retrospective, 31 Tulsa L.J. 1, 5

(1995).

49 Terry, 329 U.S. 1 at 16.

50 Id. at 19, n. 16.

12concerning the constitutional propriety of an investigative “seizure” upon less than

probable cause for purposes of “detention” and/or interrogation.”51 The Court attempted

to answer that question in the future with some confusing results, as the threshold

questions of whether, when, and how someone is seized within the meaning of the Fourth

Amendment are issues still being litigated today.

B. Seizure Doctrine After Terry: Mendenhall and the Reasonable Person

Test

After Terry recognized that one can be seized by police without being arrested,

the question of what constitutes a Fourth Amendment seizure remained largely

unanswered. The Supreme Court started to give seizure doctrine some rigid contours in

the early 1980’s, spurred by the questionable constitutionality of police efforts to combat

the war on drugs. In the 1980 case of Mendenhall v. United States52 , the Court solidified

its definition of seizure and introduced a new objective standard by which to measure

whether one had occurred: the “reasonable person test.” 53

Mendenhall established two main pathways for a Fourth Amendment seizure to

occur: the application of physical force by an officer on the subject, or the subject’s

submission to an officer’s show of authority.54 Seizures are easier to recognize in the

former pathway, as physical force on a subject is usually self-evident. But seizures by

submission can be more difficult because submitting to an officer’s show of authority can

occur in multiple contexts, and merely accepting an officer’s request to have a

conversation is not always a seizure. This difficulty is represented in Mendenhall, and the

51 Id.

52 446 U.S. 544 (1980).

53 Id. at 554.

54 Id. at 552.

13Court attempted to resolve it by creating the “reasonable person test,” which asks whether

“in view of all the circumstances surrounding the incident, a reasonable person would

have believed that he was not free to leave.”55 If the Court answers that question in the

negative, then the subject cannot be deemed to have submitted to the officer’s show of

authority, and therefore a Fourth Amendment seizure has not occurred.

The dispute in Mendenhall arose when Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

agents at airport used a “drug courier” profile to approach Sylvia Mendenhall, a twenty-

two-year-old African American woman.56 Believing her conduct was indicative of

someone illegally trafficking narcotics, the officers confronted Mendenhall as she was

walking through the airport concourse and asked to examine her ticket and

identification.57 They noticed that the name on her identification was different than the

one on her ticket and asked her to accompany them to their office, which she did. 58 Once

at the office, Mendenhall consented to a search of her person, which turned up nothing. 59

Undeterred, the officers asked for a more invasive search, which would require

Mendenhall to take off her clothes.60 Despite initially protesting and claiming she had “a

plane to catch”, Mendenhall eventually complied with the search, in which she produced

a bag of heroin from her undergarments.61 She argued that this incident was an

unreasonable seizure.62

55 Id. at 554.

56 Id. at 548.

57 Id.

58 Id.

59 Id.

60 Id. at 549

61 Id.

62 Id. at 565 (Powell, J., Concurring).

14The Supreme Court’s analysis of the case was split, with only Justices Stewart

and Rehnquist considering the issue of whether a seizure occurred when the DEA agents

first stopped Mendenhall in the airport concourse. Justices Blackmun, Powell, and Chief

Justice Burger believed that the officers had the requisite reasonable suspicion to stop

Mendenhall from the outset, primarily because of their use of a drug courier profile and

the high public interest in stopping narcotics trafficking. 63 On the other hand, Justice

Stewart’s plurality opinion (which only Justice Rehnquist joined) did not believe the

initial stop of Mendenhall constituted a seizure. 64 Applying the dicta from Terry v. Ohio,

in which the Court defined a seizure as “only when the officer, by means of physical

force or show of authority, has in some way restrained the liberty of a citizen,” Justice

Stewart pointed to the absence of a physical restraint or show of authority to reach the

conclusion that Mendenhall was not seized when she was originally approached and

questioned by the DEA agents.65 In reaching this conclusion, Justice Stewart explained

that in his view, Mendenhall had no reason to believe that she was not free to just walk

away from the officers.66 This meant that no seizure had occurred because, according to

the plurality, “a person has been ‘seized’ within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment

only if, in view of all the circumstances surrounding the incident, a reasonable person

would have believed that he was not free to leave.” 67 Thus, the “reasonable person test”

was born out of a two-justice plurality opinion.

63 Id. at 565 (Powell, J., Concurring).

64 Id. at 557.

65 Id. at 554

66 Id.

67 Id.

15In addition, Justice Stewart introduced some factors that courts should use in

determining whether the reasonable person test is satisfied. These include the number of

officers involved in the encounter (the more officers, the more threatening of a presence

and the less likely the subject feels free to leave), the display of weapon by an officer,

physical touching, and the language or tone of voice indicating that compliance might be

compelled.68 What is specifically excluded from the test, however, is the agent’s

subjective intent when approaching the defendant. 69 Similarly, the subjective impression

of the suspect is also irrelevant in the analysis, except to the extent that a reasonable

person in that suspect’s situation would have the same concerns. 70 This is because the

plurality intended for the reasonable person test to be objectively applied to the facts of

each case.

The reasonable person test is not without its critics. For example, Justice White, in

his Mendenhall dissent, questioned how a reasonable person in Mendenhall’s position

could have felt free to leave the DEA agents and board a plane after having her ticket and

driver’s license taken from her.71 He also did not think Mendenhall’s conduct was

sufficient to establish the reasonable suspicion necessary to seize her. 72 Many critics also

posit that a reasonable person always feels restricted when they are confronted by police,

and thus no one truly feels free to simply terminate a police encounter.73 Finally, by

ignoring the subjective impressions of both the police officer and the person seized, the

reasonable person standard fails to take into account how racism may play a role in who

68 Id.

69 Id. at n. 6.

70 Id.

71 Id. at 570, n. 6 (White, J., dissenting)

72 Id. at 572 (White, J., dissenting).

73 See David K. Kessler, Free to Leave—An Empirical Look at the Fourth Amendment’s Seizure Standard , 99 J.

Crim. L. & Criminology 51 (2008-2009).

16police approach for questioning, and how the race of the person being questioned may

affect how subjectively threatened they may feel. 74 Despite these criticisms and the fact

that the reasonable person test stems seemingly out of nowhere from a two-justice

plurality, the test continued to gain judicial approval and is still a crucial part of the

Supreme Court’s seizure jurisprudence today.

Since 1980, the reasonable person test has been used to decide a variety of cases

in favor of law enforcement, with the Supreme Court deeming some questionable police

tactics as not threatening for the purposes of answering the seizure question. One of the

most notorious examples of this is the 1991 case of Florida v. Bostick75 . There, narcotics

officers boarded an interstate bus as part of a drug interdiction effort and began asking

seated passengers for identification, tickets, and permission to search their luggage.76

These searches were completely warrantless and suspicionless and depended on the

consent of the subjects.77 One of these subjects was the defendant, who consented to a

search that revealed drugs.78 He argued that a reasonable person in similar conditions

would not feel free to terminate the encounter with the officer.79 The Florida Supreme

Court agreed, so much so that it adopted a per se rule prohibiting this type of police

practice in the future.80 But the U.S Supreme Court reversed, and despite calling this

practice “distasteful,” it found that it was the fact that the defendant was on a bus, not the

coercive actions of the police, that made the defendant feel like he could not leave.81

74 See Tracey Maclin, Black and Blue Encounters—Some Preliminary Thoughts About Fourth Amendment Seizures:

Should Race Matter? 26 Val. U.L. Rev. 243 (1991).

75 501 U.S. 429 (1991).

76 Id. at 431.

77 Id. at 432.

78 Id. at 433.

79 Id. at 435.

80 Id.

81 Id. at 439

17Through this holding, the Court allowed warrantless, suspicionless searches of buses for

the purposes of drug interdiction.

III. REVISITING SEIZURE DOCTRINE IN THE CONTEXT OF RACE

Throughout its analysis and application of the reasonable person test, the Supreme

Court has consistently sanctioned the use of coercive police practices that are used

disproportionately against people of color. The Court rarely mentions race or the

overwhelming evidence of racism it has at its disposal. Instead, by making the objective

analysis of the reasonable person test the focal point, the Court has been able to escape

bringing up the obvious question of whether the race of the person being seized plays a

role on whether that person feels as though they could simply terminate the encounter

with a police officer and leave. It’s time for that to change.

A. Racist Roots of Seizure Law: Slave Patrols

At the same time the Founding Fathers were complaining and revolting against

oppressive British search and seizure measures, the colonies were searching and seizing Black

people through far worse measures. Most of this was done by “slave patrols.”82 In 1693, court

officials in Philadelphia responded to complaints about the congregating and traveling of Blacks

without their masters by authorizing the constables and citizens of the city to “take up” any

Black person seen “gadding abroad” without a pass from his or her master. 83 In 1696, South

Carolina, initiated a series of measures authorizing state slave patrols to search the homes of

slaves for weapons on a weekly basis.84 In 1712, these “slave patrols” increased to being

performed on a bi-weekly basis, and the scope of the searches increased from weapons to “any

82 Tracey Ma clin, Race and the Fourth Amendment, 51 Vanderbilt Law Review 331 (1998). Available at:

https://sochalrship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol51/iss2/2.

83 Id. at 334.

84 Id.

18contraband.”85 Ten years later, these patrols were allowed to forcibly enter the home of any

house they suspected Black people may be found, and to detain any “suspicious Blacks” they

came across.86 In 1737, slave patrols could search any tavern they thought might be serving

Black people.87 By 1740, justices of the peace could seize any slave suspected of any crime

“whatsoever.”88

Slave patrols in Virginia were similarly authorized to arrest slaves on “bare suspicion.” 89

If a Black person’s presence “excited suspicion,” slave patrols could arrest them.90 In Virginia

slave patrols, “no neutral and detached magistrate intervened between a patrolman’s suspicions

and his power to arrest or search.”91 The same can be said of patrols in Virginia’s neighboring

southern colonies. A Black resident of Savannah in 1767 wrote that slave patrols would “enter

the house of any Black person who kept his lights on after 9 P.M. and fine, flog and extort food

from him.”92 Interestingly, around the same time, James Otis was speaking out about British

oppression through the use of general warrants and comparing a man’s house to his castle.

Obviously, this was only the case for white men.

Slave patrols seizing Black people that “excite suspicion” should sound familiar. Despite

taking place in the 17th and 18th centuries, these slave patrols are reminiscent of what the

Supreme Court authorized in Terry v. Ohio. By allowing law enforcement to confront and seize

people who “arouse suspicion,” and by analyzing these confrontations without considering race,

the Supreme Court was ushering in the modern equivalent of slave patrols. Under this regime,

85 Id. at 335.

86 Id.

87 Id.

88 Id.

89 Id.

90 Id.

91 Id.

92 Id.

19just like slave patrols, Black people are systematically targeted because their skin color arouses

“suspicion.” They are seized and searched through means only recently deemed constitutional by

the Supreme Court. Finally, if the suspicions of “law enforcement” happen to be correct, they are

subject to cruel punishment—namely, extremely harsh and unwarranted prison sentences. In

2017, the United States Sentencing Commission reported that “Black male offenders received

sentences on average 19.1 percent longer than similarly situated white male offenders.” 93

B. Effects of Supreme Court Seizure Doctrine on Racial Minorities.

The Supreme Court’s seizure jurisprudence has had a disparate impact on racial

minorities, especially African Americans. To illustrate this point, an examination of the above-

mentioned seizure doctrine cases in the context of how they have affected minority communities

is necessary. The best place to start is Terry v. Ohio, which, as previously mentioned, introduced

and validated the concept of a “stop-and-frisk” based on “reasonable suspicion.”

One major issue the Terry case discusses, but does little to combat, is race. By deferring

to a police officer’s experience and training in determining whether or not they fear for their

safety94 , the Court made it easy for police officers with more racist intentions to justify seizing

minorities in order to check for weapons. Chief Justice Earl Warren seemed to acknowledge this

point in Terry when he said that the case “thrusts to the fore, difficult and troublesome issues

regarding a sensitive area of police activity.”95 According to a New York County District

Attorney amicus brief filed in Terry, 1600 police reports of stops-and-frisks by the NYPD

93 Demographic Differences in Sentencing: An Update to the 2012 Booker Rep ort, United States Sentencing

Commission (November 14, 2016). Available at: ussc.gov/research/research -reports/demographic-differences-

sentencing.

94 Terry, 393 U.S. 1 at 30.

95 Id. at 9.

20“showed a disproportionate racial impact of those actions.” 96 For an example of a racially

motivated stop-and-frisk, look no further than facts of Terry.

Believing the stop in Terry may have been racially motivated, Louis Stokes,

Terry’s defense attorney, asked Officer McFadden what exactly it was about the

defendants and their actions that aroused his suspicion. 97 McFadden replied, “Well, to tell

you the truth, I just didn’t like ‘em.”98 After going on to say that he thought they were

“casing the joint for the purpose of robbing it,” he was asked if he had ever in his thirty-

nine years as a police officer observed anybody casing a store for a robbery. 99 He replied

that he had not.100 He was then asked again what attracted him to the defendants, and

again indicated that he just did not like them. This is not surprising to many people of

color, as Tracey Maclin explains, “In America, police targeting of Black people for

excessive and disproportionate search and seizure is a practice older than the Republic

itself.”101

The general efficacy of stop-and-frisk on crime reduction is highly debated, but there can

be no question that even in the 21st century, it continues to be used overwhelmingly on racial

minorities. For example, in 1999, African Americans made up 50 percent of New York’s

population, but accounted for 84 percent of the city’s stops. 102 Between 2004 and 2012, the

NYPD made 4.4 million stops under their stop-and-frisk policy.103 More than 80 percent of those

4.4 million people were Black and Latino.104 Interestingly, despite the entire justification for a

96 Michael R. Juviler, A Prosecutor’s Perspective, 72 St. John’s L. Rev. 741, 743 (1998).

97 Louis Stokes, Representing John W. Terry, St. John’s L. Rev. 727, 729 (1998).

98 Id.

99 Id.

100 Id.

101 Race and the Fourth Amendment, supra note 80.

102 Stop and Frisk Data, Am. Civ. Liberties Union, https://www/nyclu.org/en/stop-and-frisk-data.

103 Id.

104 Id.

21stop being officer safety (to search for weapons), the likelihood of a Black New Yorker found to

be yielding a weapon was half that of white New Yorkers. 105 The likelihood of finding

contraband on a Black New Yorker was one third of that for a white New Yorker. 106 In 2017, 90

percent of those stopped in New York City were Black or Latino and almost 70 percent of those

stopped were innocent.107 According to the NYPD annual reports, 13,459 stops were recorded in

2019, with 7,981 of them being Black, 1,215 being white, and 8,867 being innocent. 108 The

NYPD data breaking down Terry stops by race goes back as far as 2003. Every single year since

then, Black people have made up over half of all those searched. 109 If these numbers prove

anything, it’s that stop-and-frisk policies disproportionately target racial minorities, and that the

overwhelming majority of those stopped are innocent. Thanks to Terry, even if the primary

motivation behind the stops is racial bias, it’s irrelevant because the subjective motivations of the

officer are not considered by the Court.

The Supreme Court continued the trend of discounting an officer’s subjective motivations

behind a seizure—this time, in the context of traffic stops—in Whren v. United States110 , where it

unanimously held that pretextual traffic stops do not raise Fourth Amendment concerns. 111 In

that case, police officers saw two African American men driving in a car and believed, without

probable cause or even reasonable suspicion, that they were committing drug crimes. 112 In order

to investigate further, they followed the car and eventually observed the d river make a turn

without signaling first.113 Using the minor infraction as a pretext to search the car, the officers

105 Id.

106 Id.

107 Id.

108 Id.

109 Id.

110 517 U.S. 806 (1996).

111 Id. at 813.

112 Id. at 808.

113 Id.

22stopped the car, found drugs, and arrested the men. 114 The defendants contended that this was an

unconstitutional seizure because the officers did not intend to issue a citation when they stopped

the car and relied on racial profiling instead of reasonable suspicion. 115 Justice Scalia authored

the opinion that it did not matter if police officers have ulterior or nefarious motives when

stopping automobiles for minor traffic infractions because Fourth Amendment analysis does not

inquire into the subjective mental state of police officers. 116

But perhaps if the court in Whren did allow an analysis on the subjective mental state of

police officers, the staggering evidence of pretextual stops might be too damning to ignore. Some

of the most recent evidence comes from the Stanford University’s Open Policing Project, which,

using information obtained through public record requests, examined almost 100 million traffic

stops conducted from 2011 to 2017 across 21 state patrol agencies and 29 municipal police

departments. The results show that race is a factor when people are pulled over, and that this

problem is occurring on national scale. Black and Latino drivers are stopped and searched based

on less evidence than white drivers, but white drivers are more likely to be found with illegal

items.117 Across states, contraband was found in 36 percent of searches of white drivers,

compared to 32 percent for Black drivers, and 26 percent of Latinos. 118 These statistics are not

surprising to people of color, who refer to this phenomenon as the crime of “driving while

Black.”119

114 Id. at 808-809.

115 Id. at 809.

116 Id. at 813.

117 Findings, Stanford Open Police Project. Available at: https://openpolicing.stanford.edu/findings.

118 Id.

119 See generally David A. Harris, “Driving While Black” and All Other Traffic Offenses: The Supreme Court and

Pretextual Traffic Stops, 87 J. Crim L. & Criminology 544; see also Tracey Maclin, Can a Traffic Offense Be D.W.B

(Driving While Black)? L.A. Times, Mar. 9, 1997.

23Minority communities are not just subject to arbitrary and racially motivated stops on the

streets and in their cars. Public transportation has become a place for law enforcement to target

them as well, thanks to cases like Bostick, which held that suspicionless bus sweeps in which

police question passengers and ask permission to search their bodies and luggage would not

communicate to a reasonable passenger that they were not free to leave and thus, it is not a

seizure. Putting aside the questionable truthfulness of that assertion, the main criticism of Bostick

has centered around its impact on minority groups. The Bostick majority had evidence of the

large role that race played in bus sweeps but remained largely silent on the issue. In his dissent,

Thurgood Marshall, then the first and only Black person on the Supreme Court, wrote, “the basis

of the decision to single out particular passengers during a suspicionless sweep is less likely to be

inarticulable than unspeakable.”120 In addition to this dissent, the Court received an amicus brief

filed by the ACLU which claimed, “insofar as the facts of reported bus interdiction cases

indicate, the defendants all appear to be Black or Hispanic.”121 Even Americans for Effective

Law enforcement, an organization which prior to Bostick had filed 86 amicus briefs in the

Supreme Court supporting the interests of law enforcement, argued that drug interdiction raids

on buses violated the Fourth Amendment and alluded to the discriminatory impact that these

confrontations had on minority citizens.122 They explained that the Court has not extended the

rationale of prior cases authorizing suspicionless seizures to the setting of passengers sitting on a

bus and “moreover, any such extension would be constitutionally invalid …setting aside equal

protection issues, it is difficult to imagine a scenario of police activities, as in the present case,

upon a planeload of business class air passengers arriving at a busy air terminal after an interstate

120 Bostick, 501 U.S. at 441 n. 1 (Marshall, J. dissenting).

121 Brief for the American Civil Liberties Union et al. as Amicus Curiae at 8 n. 19, Florida v. Bostick, 501 U.S. 429

(1991) (No. 89-1717).

122 Brief for the Americans for Effective Law Enforcement, Inc. as Amicus Curiae at 8, Bostick (No. 89-1717).

24flight.”123 Despite alarming evidence that bus sweeps were being used to specifically target

minority groups and the implications that constitutionalizing them would have on these groups,

the Court simply ran the scenario through the reasonable person test and concluded that it did not

violate the Fourth Amendment.

Over a decade after Bostick, the Court held the same way on similar facts in United States

v. Drayton124 . In that case, the Court held that during bus sweeps, police do not even have to

inform the subjects of the sweep that they have the right to say no to questioning.125 The Court

again made this determination by using the reasonable person test, concluding that even if a

reasonable person is not made aware by an officer requesting to search them that they can

decline, they still feel as though that in an option.126 But research reveals otherwise. An

examination of the existing empirical evidence of the psychology of coercion suggests that in

many situations where citizens find themselves in an encounter with the police, the encount er is

not consensual because a reasonable person would not feel free to terminate it. 127 Such evidence

suggests that the subsequent search is not voluntary, because a reasonable person would not be,

under the totality of the circumstances, in a position to make a voluntary decision about consent.

This is especially true in the context of bus sweeps. Michelle Alexander put it best when she said

“consent searches are valuable tools for the police only because hardly anyone says no.” 128

If a “reasonable person” would have a hard time saying no to consent searches, this is

especially true for a reasonable person of color. From all the data we now have available, it is

obvious that Black and brown people are targeted and harassed by police at a higher rate than

123 Id.

124 536 U.S. 194 (2002).

125 Id. at 204

126 Id.

127 David K. Kessler, supra note 71.

128 Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New

Press, 2012.

25whites. According to a 2020 Kaiser Family Foundation poll, 71 percent of Black Americans said

they have experienced some form of racial discrimination or mistreatment during their

lifetimes.129 48 percent said that at a point, they felt their life was in danger because of their

race.130 41 percent of Black Americans said they have been stopped or detained by police

because of their race.131 In comparison, only 3 percent of white people report these types of

negative police interactions in their lifetimes.132 This disparity gives credence to claims that there

are really “two Americas”, one for white people, who get to go about their business largely

unaffected and unbothered by police, and one for Black Americans, who feel as though they are

walking through life with a permanent target on their backs. When the Supreme Court applies an

objective “reasonable person” test, it is, whether knowingly or not, applying a “reasonable white

person” test. By keeping things as objective as possible, the law can continue to find the

subjective experiences of minorities with police to be irrelevant when it comes to the Fourth

Amendment.

C. Current Events Suggest the Time is Ripe for the Supreme Court to

Reconsider and Redevelop Seizure Doctrine in the Same Way it has

Treated Search Doctrine

Despite the obvious fact that racism has existed in America since before its

founding, the events of the summer of 2020 and death of George Floyd at the hands of

police triggered a pivotal national dialogue concerning racial inequality and civil rights in

America. This dialogue cast a burning spotlight on the issue of police mistreatment of the

Black community and resulted in the Black Lives Matter movement garnering national

129 Kaiser Family Foundation, (2020). Poll: 7 in 10 Black Americans Say They Have Experienced Incidents of

Discrimination or Police Mistreatment in Their Lifetime, Including Nearly Half Who Felt Their Lives Were in

Danger.

130 Id.

131 Id.

132 Id.

26attention133 , which amplified their calls for justice on a global scale. This long-overdue

discussion prompted outraged citizens of all races to protest and stand behind the Black

Lives Matter movement as they demanded change and accountability in policing. Now,

the reality that minorities are treated differently by police is seemingly impossible to

ignore. But the Supreme Court continues to ignore it.

1. The Summer of 2020 Brought New Awareness to the Issue of Law

Enforcement’s Mistreatment of the Black Community

In 2020, the public constantly watched in horror at the seemingly endless high-

profile cases in which police killed unarmed Black men and women in situations where

deadly force was unnecessary. With each case, protestors took to the streets to demand

justice in record numbers. One estimate found that from June 8 to June 14, roughly 26

million people in the U.S. said they participated in a Black Lives Matter protest. 134

The now notorious murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis was the major catalyst

for the protests and demands for justice by the Black Lives Matter movement. Floyd, a

Black man, had allegedly used a counterfeit $20 bill at a grocery store, and the police

were called.135 After being placed in handcuffs, Mr. Floyd laid on the ground while

Police Officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for an astounding 9 minutes and 29

133 Dhrumil Mehta, National Media Coverage of Black Lives Matter Had Fallen During the Trump Era —Until Now,

FIVETHIRTYEIGHT, (Jun. 11, 2020), https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/national-media-coverage-of-black-lives-

matter-had-fallen-during-the-trump-era-until-now/.

134 Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui and Jugal K. Patel, Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S.

History, THE NEW YORK TIMES, (July 3, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-

floyd-protest-crowd-size.html.

135 Evan Hill, et. al., How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody, THE NEW YORK TIMES, (May 31, 2020),

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/us/george-floyd-investigation.html.

27seconds.136 Unfortunately, this resulted in the death of George Floyd. 137 Amid global

calls for justice and accountability for this public execution, Chauvin was charged with

unintentional second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree

manslaughter.138 In April 2021, Chauvin was found guilty on all counts. 139

Even in situations where Black men don’t engage in any illegal conduct

whatsoever, routine interactions with police can still result in their deaths. The 2019

death of Elijah McClain is illustrative. McClain, a twenty-three-year-old Black man, was

walking home from a convenience store in Aurora, Colorado when police officers

approached him.140 McClain was wearing an open-faced ski mask due to his anemia,

which often made him feel cold, but evidently this made someone call the police to report

a “suspicious person.”141 When police ordered McClain to stop, he responded by saying

““I have a right to walk to where I’m going.”142 This should have ended the interaction,

because McClain’s swearing of a ski mask likely did not give rise to any reasonable

suspicion. Wearing a ski mask is not illegal, and the 911 caller did not allege there was

any sort of illegal conduct going on.143 McClain was unarmed and simply walking

136 Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs, Prosecutors say Derek Chauvin Knelt on George Floyd for 9 Minutes 29 Se conds,

Longer Than Initially Reported, THE NEW YORK TIMES, (March 20, 2021),

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/30/us/derek-chauvin-george-floyd-kneel-9-minutes-29-seconds.html.

137 Id.

138 Shalia Dewan, What are the Charges Against Derek Chauvin, THE NEW YORK TIMES, (April 19, 2021),

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/20/us/derek-chauvin-charges.html.

139 Laurel Wamsley, Derek Chauvin Found Guilty of George Floyd’s Murder, NPR, (April 20, 2021),

https://www.npr.org/sections/trial-over-killing-of-george-floyd/2021/04/20/987777911/court-says-jury-has-reached-

verdict-in-derek-chauvins-murder-trial.

140 Claire Lampen, What We Know About the Killing of Elijah McClain, THE CUT, (Updated Feb, 22, 2021),

https://www.thecut.com/2021/02/the-killing-of-elijah-mcclain-everything-we-know.html.

141 Id.

142 Jonathan Smith, Dr. Melissa Costello, and Roberto Villaseñor, Investigation Report and Recommendations, (Feb.

22, 2021), p. 22,

https://auroragov.org/UserFiles/Servers/Server_1881137/File/News%20Items/Investigation%20Report%20and%2 0

Recommendations%20(FINAL).pdf.

143 Id. at p. 23, the caller said he “didn’t feel threatened or anything” and just thought “it was weird.”

28home.144 Despite McClain’s attempt to terminate the interaction with officers, they

tackled him to the ground within ten seconds of first asking him to stop, and put him in a

“carotid hold”, which entails an officer applying pressure to the side of a suspect’s neck

in order to temporarily cut off blood flow to the brain. 145 The officers then called

paramedics, who injected McClain with 500 milligrams of Ketamine to sedate him while

officers held him down.146 McClain suffered a heart attack on the way to the hospital and

died two days later, after he was declared braindead. 147 Despite this incident occurring in

2019 and all officers being cleared of any wrongdoing, the death of George Floyd and the

massive protests it sparked in the summer of 2020 led the Governor of Colorado to issue

an executive order designating the State Attorney General to “investigate and, if the facts

support prosecution, criminally prosecute any individuals whose actions caused the death

of Elijah McClain.”148

The 157-page incident report was released in February 2021, and it alleged large-

scale misconduct by the police.149 First, the report contends that the Aurora Police

Department “stretched the record to exonerate the officers rather than present a neutral

version of the facts.”150 Second, it found that the police escalated “what may have been a

consensual encounter with Mr. McClain into an investigatory stop” 151 (or Terry stop),

which was not warranted because “walking away from a police officer when told to stop,

standing alone, is not sufficient” to trigger reasonable suspicion.152 Finally, the report

144 Lampen, What We Know About the Killing of Elijah McClain.

145 Id.

146 Id.

147 Id.

148 Id.

149 Jonathan Smith, Dr. Melissa Costello, and Roberto Villaseñor, Investigation Report and Recommendations.

150 Id. at 130-131.

151 Id. at 2-3.

152 Id. at 76.

29noted that the 500 milligrams of ketamine the paramedics injected into McClain to sedate

him was inappropriate in light of the fact that McClain “did not appear to be offering

meaningful resistance in the presence of EMS personnel.” 153 In fact, the report found

McClain instead to be “crying out in pain, apologizing, explaining himself, and pleading

with the officers.”154 The report also said that the 500 milligram dosage to be “based on a

grossly inaccurate and inflated estimate of McClain’s size.” 155

Despite the shocking amount of misconduct alleged in the report, none of the

officers faced any criminal charges for their actions, and only one of them was fired.156

The only other disciplinary action was for three officers who were not involved with the

incident, who were fired because while standing in front of a memorial for Elijah

McClain, they took a picture of themselves smiling happily while one of the officers

reenacted the type of chokehold used on McClain on the other officer. 157 They then sent

the photo to one of the officers involved in McClain’s death. 158 Many accurately saw this

as police mocking the death of McClain, which only strengthened calls for police

accountability and disciplinary action. McClain’s family summed up the entire incident

and aftermath appropriately as “a textbook example of law enforcement’s disparate and

racist treatment of Black men.”159 These “textbook examples” are becoming far too

frequent and serve as a reminder that minority communities have legitimate reasons to

fear any contact with law enforcement because they do not want to be the next Elijah

McClain. This reality should be reflected in the Supreme Court’s seizure jurisprudence.

153 Id. at 7.

154 Id. at 5.

155 Id. at 7.

156 Lampen, What We Know About the Killing of Elijah McClain.

157 Id.

158 Id.

159 Id.

30You can also read